art01 - omena júnior.indd - Sociedade Brasileira de Ornitologia

art01 - omena júnior.indd - Sociedade Brasileira de Ornitologia

art01 - omena júnior.indd - Sociedade Brasileira de Ornitologia

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

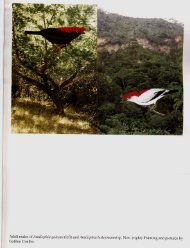

114 Frugivory by birds in Myrsine coriacea (Myrsinaceae) inhabiting fragments of mixedAraucaria Forest in the Aparados da Serra National Park, RS, BrazilAparecida Brusamarello Basler; Eliara Solange Müller and; Maria Virginia PetryPizo (2004) recor<strong>de</strong>d the consumption of fruit from Myrsineumbellata by several bird species.Avian ecology studies have recor<strong>de</strong>d four cotingaspecies (Cotingidae) consuming the fruit of Myrsine coriaceaand Myrsine lancifolia (Pizo et al. 2002); Bailoniusbailloni (Ramphastidae) consuming Rapanea ferrugineafruit (Galetti et al. 2000); and Pipile jacutinga (Cracidae)consuming Rapanea umbellata and R. ferrugineafruit (Galetti et al. 1997, Galetti et al. 2000). Fransciscoand Galetti (2001) studied frugivory and seed dispersalin Myrsine lancifolia and found 11 bird species as potentialdispersers. Pineschi (1990) studied seed-dispersingbirds for seven species of Rapanea and recor<strong>de</strong>d 104 speciesconsuming fruits, of which 60 species were potentialdispersers.Myrsine sp. fruit is consumed by birds of all sizesand according to Carvalho (1994) and Backes and Irgang(2002), Myrsine seeds exhibit dormancy caused by the endocarp,but can easily germinate in any kind of soil afterpassing through the digestive trait of an animal. Therefore,fauna feeding on the fruit is also important to thelife cycle of Myrsinaceae species.The aim of the present study was to i<strong>de</strong>ntify birdsassociated to Myrsine coriacea and investigate their behaviourin or<strong>de</strong>r to answer the following questions: (i) Dobirds use M. coriacea preferentially for fruit consumption?(ii) Does the size of a fragment of forest influencethe number of bird species using M. coriacea and the frequencyof use categories? (iii) Does bird behaviour on thetrees influence the number of bird species using M. coriacea?(iv) Does bird behaviour on the trees influence thenumber of visit events? The potentiality of birds as seeddispersers was also evaluated.MethodsData collection was performed in the Aparados daSerra National Park (ASNP). Three fragments of MixedAraucaria Forest approximately 20 ha in size, classifiedas small fragments (P1, P2 and P3), and three fragmentsapproximately 200 ha in size, classified as largefragments (G1, G2 and G3), were selected. A total ofsix individuals of M. coriacea were selected, correspondingto one individual per fragment. The individualswere located at bor<strong>de</strong>rs or clearings.Three individualswere approximately 13 m high and the other threewere approximately 4 m high, distributed randomly byfragments.The i<strong>de</strong>ntification of the species from the genusMyrsine was performed by collecting samples and performingexsiccates for comparisons to material from theAnchietan Herbarium of the Vale do Rio dos Sinos University.Authors were also consulted as Barroso 1999 andBackes and Irgang 2002, for example.In the month of July 2004 were the first search fieldto individuals of M. coriacea, but they did not have fruityet. Some individuals exhibited initial indications of fructificationin August, but only in November 2004 when allsix individuals were with fruit, began the remarks, whichexten<strong>de</strong>d to the month of February 2005.Varying quantities of fruit were found in both immatureand ripe stages within the same tree. Two randomobservations per month were ma<strong>de</strong> for each individual,totalling 96 hours of observation. The sampling effortwas the same per day periods (6 am to 7 pm). Each observationspen<strong>de</strong>d two hours a day, comprising four hoursper month for each individual of M. coriacea.Observations were performed with the use of10 x 40 mm binoculars. For bird i<strong>de</strong>ntification in locus,field gui<strong>de</strong>s by Narosky and Yzurieta (1987) and De LaPeña and Rumboll (1998) were employed. The followingdata were sampled: species of each bird observed on theplant species; bird behaviour (fruit consumption, insectconsumption and perching); number of visiting birds;time and visiting duration (measured by chronometer);visiting pattern (the manner in which the bird reachedthe tree: individually, by pairs, in mono-specific or mixedflocks), agonistic encounters (intraspecific and interspecific);and whether visits were complete (when the birdwas seen flying in coming, if not of food or fruit and / orinsects and when he left) or incomplete (when just partof the visit could be followed) according to Krügel et al.(2006), when we were unable to view all the activity ofthe bird (due to factors such as the limitation of binocularsfocus or sunlight, for example).Visiting birds were classified into different feedingguilds, as <strong>de</strong>scribed in Sick (1997) and Azpiroz (2001), asfrugivorous (FR, diet predominantly of fruit, vegetablesand occasionally invertebrates), granivorous (GR, dietbased on grains), nectarivorous (NC, diet based on nectarand occasionally small invertebrates), insectivorous(IN, diet exclusively based on invertebrates) and onivorous(ON, diet including fruit, invertebrates and smallvertebrates).The observation of frugivorous species inclu<strong>de</strong>dthe recording of fruit consumed, collection behaviourand fruit ingestion treatment. Collection behaviour wasclassified according to <strong>de</strong>scriptions by Moermond andDenslow (1985): Stalling (S): the bird flies toward thefruit and plucks it without stopping; Hovering (Hv): thebird stops in the air in front of the fruit; Picking (P): thebird collects the fruit next to its perch without stretchingor assume a special position; Reaching (R): the birdstretches out its body to pluck the fruit; Hanging (Hg):entire body and legs are un<strong>de</strong>r the perch, with the ventralsi<strong>de</strong> facing upward. Fruit ingestion treatments wereclassified into Swallowing (when the fruit is swallowedwhole); Mashing (when the bird macerates or grinds thefruit with its jaws before ingesting); Pecking (when theRevista <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong>, 17(2), 2009