FILARIOSE A Filariose é uma doença causada por um nematoda ...

FILARIOSE A Filariose é uma doença causada por um nematoda ...

FILARIOSE A Filariose é uma doença causada por um nematoda ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>FILARIOSE</strong><br />

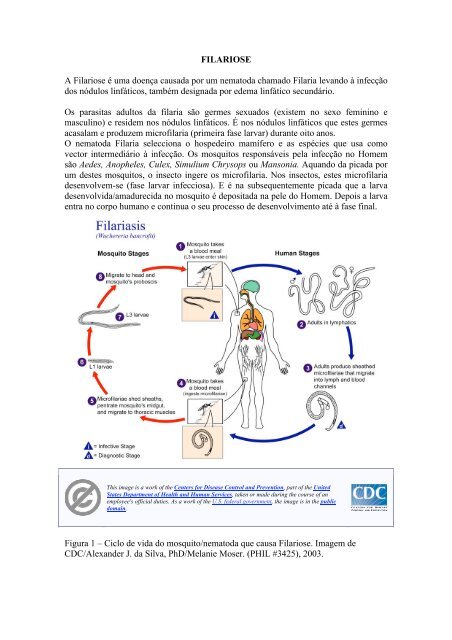

A <strong>Filariose</strong> <strong>é</strong> <strong><strong>um</strong>a</strong> <strong>doença</strong> <strong>causada</strong> <strong>por</strong> <strong>um</strong> <strong>nematoda</strong> chamado Filaria levando à infecção<br />

dos nódulos linfáticos, tamb<strong>é</strong>m designada <strong>por</strong> edema linfático secundário.<br />

Os parasitas adultos da filaria são germes sexuados (existem no sexo feminino e<br />

masculino) e residem nos nódulos linfáticos. É nos nódulos linfáticos que estes germes<br />

acasalam e produzem microfilaria (primeira fase larvar) durante oito anos.<br />

O <strong>nematoda</strong> Filaria selecciona o hospedeiro mamífero e as esp<strong>é</strong>cies que usa como<br />

vector intermediário à infecção. Os mosquitos responsáveis pela infecção no Homem<br />

são Aedes, Anopheles, Culex, Simuli<strong>um</strong> Chrysops ou Mansonia. Aquando da picada <strong>por</strong><br />

<strong>um</strong> destes mosquitos, o insecto ingere os microfilaria. Nos insectos, estes microfilaria<br />

desenvolvem-se (fase larvar infecciosa). E <strong>é</strong> na subsequentemente picada que a larva<br />

desenvolvida/amadurecida no mosquito <strong>é</strong> depositada na pele do Homem. Depois a larva<br />

entra no corpo h<strong><strong>um</strong>a</strong>no e continua o seu processo de desenvolvimento at<strong>é</strong> à fase final.<br />

This image is a work of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, part of the United<br />

States Department of Health and H<strong><strong>um</strong>a</strong>n Services, taken or made during the course of an<br />

employee's official duties. As a work of the U.S. federal government, the image is in the public<br />

domain.<br />

Figura 1 – Ciclo de vida do mosquito/<strong>nematoda</strong> que causa <strong>Filariose</strong>. Imagem de<br />

CDC/Alexander J. da Silva, PhD/Melanie Moser. (PHIL #3425), 2003.

EPIDEMIOLOGIA<br />

Estimam-se que 120 milhões de pessoas estão infectadas com <strong>um</strong> dos <strong>nematoda</strong> Filaria,<br />

como <strong>por</strong> exemplo Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi e Brugia timori. Sendo estes os<br />

agentes causadores de <strong>Filariose</strong> Linfática. No total, 1.3 biliões de pessoas estão em<br />

constante risco de infecção.<br />

A <strong>doença</strong> está presente em 83 países e <strong>é</strong> predominante em África, Índia, no Sul da<br />

China, em determinadas zonas da Am<strong>é</strong>rica do Sul (Caraíbas) e nas ilhas do Sul do<br />

Pacífico. Como descrito, a <strong>doença</strong> <strong>é</strong> bastante com<strong>um</strong> em países tropicais. No entanto,<br />

70% dos casos diagnosticados com <strong>Filariose</strong> Linfática são na Índia, Nig<strong>é</strong>ria, Indon<strong>é</strong>sia e<br />

Bangladesh. No total, dois terços das populações infectadas residem na Ásia.<br />

Entre todos os adultos residentes nas áreas acima mencionadas, 12.5% tem sinais<br />

clínicos de edema linfático e 21% possuem hidrocele. No entanto, a maioria da<br />

população está inoculada com o estado larvar infeccioso durante toda a sua vida.<br />

A <strong>Filariose</strong> afecta as zonas tropicais e sub-tropicais. Este <strong>é</strong> o habitat propício ao<br />

desenvolvimento do vector da <strong>Filariose</strong> Linfática, devido ao ambiente húmido. A<br />

h<strong>um</strong>idade <strong>é</strong> <strong>um</strong> factor necessário a sobrevivência do estado larvar infeccioso e à<br />

microfilaria. A maioria dos casos clínicos está presente nas zonas rurais e em regiões<br />

com reduzidas condições sanitárias e fraca qualidade de vida.<br />

Figura 2 – Mapa dos países afectados pela <strong>Filariose</strong> Linfática. A azul países que têm <strong>um</strong><br />

programa activo de eliminação da <strong>Filariose</strong> Linfática. E a amarelo países que ainda não<br />

tem <strong>um</strong> programa activo de eliminação da <strong>Filariose</strong> Linfática. Como <strong>é</strong> o caso de<br />

Angola.

CASOS CLÍNICOS<br />

Os pacientes afectados pela microfilaria podem apresentar infecções assintomáticas<br />

(sem sintomas) ou sinais de infecção aguda ou crónica.<br />

No geral, todos os pacientes têm elevados riscos de desenvolverem sintomas crónicos.<br />

Como <strong>por</strong> exemplo, linfomas, Elefantiase ou cegueira. Qualquer destes sintomas reduz<br />

a produtividade do paciente e eleva o risco a infecções.<br />

Os sinais de infecção aguda incluem adeno-linfatites (DLA) e filaria linfatites (FLA)<br />

agudas.<br />

DLA <strong>é</strong> a manifestação mais com<strong>um</strong> da <strong>doença</strong> e <strong>é</strong> caracterizada <strong>por</strong> ataques de febre.<br />

Estes ataques de febre podem ocorrer no início e no “terminus” da <strong>doença</strong>. A zona<br />

cor<strong>por</strong>al com a infecção mostra-se dorida, frágil, quente, vermelha e inchada. Os<br />

nódulos linfáticos das virilhas e das axilas ficam frequentemente inchados. Os<br />

incidentes agudos ocorrem várias vezes ao ano em pacientes com <strong>Filariose</strong>. Os mesmos<br />

a<strong>um</strong>entam de frequência com o a<strong>um</strong>ento do grau de edema linfático.<br />

Infecções secundárias, <strong>causada</strong>s pela bact<strong>é</strong>ria Streptococci, podem tamb<strong>é</strong>m causar estes<br />

mesmos incidentes agudos.<br />

As zonas do corpo h<strong><strong>um</strong>a</strong>no mais afectado são os membros (braços e pernas) e pequenas<br />

lesões, que facilitam a entrada das larvas. As pequenas lesões podem ser eczemas,<br />

posteriores mordidas de insectos ou infecções.<br />

Os ataques de DLA são responsáveis pela persistência e progressão do inchaço levando<br />

a casos de Elefantiase. Elefantiase pode se estender desde das pernas aos órgãos genitais<br />

e desde dos braços aos seios.<br />

FLA <strong>é</strong> causado pela mordida de germes adultos, o que <strong>é</strong> raro. Esta infecção <strong>é</strong> detectada<br />

quando são observados germes adultos destruídos nos nódulos linfáticos. Pequenos e<br />

frágeis nódulos são formados onde os germes adultos morrem. Isto <strong>é</strong>, no escroto ou ao<br />

longo dos vasos linfáticos. Os nódulos linfáticos tamb<strong>é</strong>m se podem tornar frágeis.<br />

Eventos de edema transientes podem ocorrer. Tais eventos não estão associados à febre,<br />

toxemia ou infecções bacterianas secundárias.<br />

As manifestações crónicas de FLA são edemas linfáticos, Elefantiase e lesões no tracto<br />

genito-urinário. Na maioria dos casos de infecção crónica de <strong>Filariose</strong> Linfática<br />

desenvolve-se em Elefantiase.<br />

As zonas cor<strong>por</strong>ais afectadas ficam inchadas, doridas e normalmente têm mau odor. A<br />

pele incha e enrijece criando fissuras. Úlceras e inchaços poderão crescer ao ponto de<br />

interferir com a articulação dos membros e debilitar drasticamente a vítima.<br />

Nas mulheres <strong>é</strong> raro o órgão genital (incluindo os seios) desenvolverem Elefantiase.<br />

No entanto, nos homens, hidrocele <strong>é</strong> <strong><strong>um</strong>a</strong> manifestação crónica de FLA bastante<br />

com<strong>um</strong>.<br />

Tamb<strong>é</strong>m existem casos clínicos de <strong>Filariose</strong> Sub-cutânea. Nestes casos desenvolvem-se<br />

papos, nódulos e arranhões. Depois a pele fica seca, enrijece e mostra sinais de hipo<br />

e/ou hiper-pigmentação. Pruritus (comichão) <strong>é</strong> com<strong>um</strong> e pode se tornar severo.

Figura 3 – Fotografias de pacientes com Elefantiase no p<strong>é</strong> e no braço, respectivamente.<br />

Imagens cedidas <strong>por</strong> Dr. Jim Ertle.

DIAGNÓSTICO<br />

Os actuais diagnósticos são:<br />

1. M<strong>é</strong>todo da filtração membranar para detecção da microfilaria: colheita de<br />

sangue nocturno. Filtrar sangue n<strong><strong>um</strong>a</strong> membrana mili<strong>por</strong>o. Permite detectar e<br />

quantificar o nível de infecção.<br />

A administração de diethylcarbamazine ajuda à detecção da microfilaria durante<br />

o dia, se necessário.<br />

2. Amostra de pele: microfilaria de O. Volvulus e M. Streptocerca são facilmente<br />

detectados pela biopsia da <strong>Filariose</strong> Sub-cutânea. A análise de amostras de pele<br />

<strong>é</strong> específica e pode ser obtida atrav<strong>é</strong>s de <strong>um</strong> furo ou o uso de <strong><strong>um</strong>a</strong> agulha. As<br />

biopsias são retiradas de zonas com elevado nível de infecção, como a crosta<br />

íliaca.<br />

3. Radiografia: na detecção da calcificação de germes mortos no tecido infectado.<br />

Este m<strong>é</strong>todo <strong>é</strong> limitado e só serve para detectar germes adultos mortos.<br />

4. Ultrasonografia: permite a localização e visualização do germe adulto W.<br />

bancrofti no escroto linfático de pacientes masculinos assintomáticos de<br />

microfilaria. O movimento do germe <strong>é</strong> designado <strong>por</strong> “a dança filarial”. Esta<br />

t<strong>é</strong>cnica não <strong>é</strong> eficiente em pacientes com edema linfático <strong>por</strong>que não há germes<br />

adultos no corpo h<strong><strong>um</strong>a</strong>no nesta fase da <strong>doença</strong>. A ultrasonografia do escroto<br />

ainda não foi provada ser eficiente em pacientes infectados com B. Malayi<br />

<strong>por</strong>que este não envolve a zona genital.<br />

5. Cintigrafia linfática: Injecção de alb<strong>um</strong>ina ou dextran marcada radioactivamente<br />

nos p<strong>é</strong>s. Esta t<strong>é</strong>cnica permite o diagnóstico de anomalias nos nódulos linfáticos.<br />

Isto <strong>é</strong>, o diagnóstico possível para detecção à infecção <strong>por</strong> microfilaria.<br />

6. Teste de imunocromatografia: teste de elevada sensibilidade e especificidade na<br />

detecção do antigen da filaria para o diagnóstico da infecção pelo W. bancrofti.<br />

Atenção que este teste <strong>é</strong> positivo nos estados iniciais da <strong>doença</strong> quando os<br />

germes adultos ainda estão vivos. E <strong>é</strong> negativo quando os germes adultos<br />

morrem.<br />

7. Enzyme Linked Immuno Sorber Assay (ELISA): usado no diagnóstico de<br />

infecção pelo germe W. Bancrofti. É <strong>um</strong> processo moroso e inconveniente.<br />

8. Detecção do DNA parasita <strong>por</strong> PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction): protocolo<br />

que permite a detecção do DNA do parasita na fase adulta e na primeira fase<br />

larvar no Homem

PREVENÇÃO E TRATAMENTO<br />

O Programa Global para a Eliminação da <strong>Filariose</strong> Linfáctica (GPELF) planeia eliminar<br />

a <strong>Filariose</strong> Linfáctica como <strong><strong>um</strong>a</strong> <strong>doença</strong> pública at<strong>é</strong> 2020. A forma de actuação <strong>é</strong> feita<br />

pela prevenção da transmissão de microfilaria a pessoas da comunidade que ainda não<br />

estão infectadas.<br />

O programa <strong>é</strong> conduzido nos países afectados pela <strong>doença</strong> com a ajuda da WHO e<br />

muitas outras organizações não governamentais (NOG). Estas organizações promovem<br />

a administração anual da droga antimicrofilaria (MDA) a pessoas infectadas e<br />

seleccionadas da comunidade.<br />

Em regiões onde o <strong>nematoda</strong> da filaria Onchocerca volvulus <strong>é</strong> end<strong>é</strong>mico, <strong><strong>um</strong>a</strong><br />

combinação de drogas (“ivermectin” e “albendazole”) <strong>é</strong> administrada. Noutras onde o<br />

<strong>nematoda</strong>s W. bancrofti ou Brugia spp. estão presentes a droga administrada <strong>é</strong><br />

“diethylcarbamazine” e “albendazole”.<br />

Ambas combinações de drogas são efectivas a matar microfilaria, mas são limitadas e<br />

têm efeitos secundários nos germes adultos.<br />

Programas computacionais, como LYM-FASIM, prevêem que <strong>é</strong> necessário o controlo<br />

da Filaria Linfática pela administração de drogas <strong>por</strong> pelo menos oito anos, ass<strong>um</strong>indo a<br />

cobertura de mais do que 65% da população infectada.<br />

Detalhes sobre as drogas:<br />

“Diethylcarbamazine” – a droga <strong>é</strong> efectiva contra microfilaria e contra germes adultos.<br />

Esta droga só consegue ser efectiva em 50% dos pacientes infectados com germes<br />

adultos. A dose inicial recomendada <strong>é</strong> 6 mg/Kg. Mesmo em administrações anuais, esta<br />

<strong>é</strong> <strong><strong>um</strong>a</strong> boa droga para prevenir a transmissão de <strong>Filariose</strong>.<br />

“Ivermectin” – droga que actua directamente na microfilaria. Adminitrações únicas de<br />

200-400 µg/kg mantêm os níveis de microfilaria baixos at<strong>é</strong> doze meses após a<br />

administração. Não tem qualquer efeito sobre o parasita adulto. Esta droga <strong>é</strong> a<br />

seleccionada para o tratamento contra Onchocerca volvulus e para a prevenção da<br />

<strong>doença</strong> em países de África onde Onchocerca volvulus <strong>é</strong> <strong>um</strong> <strong>nematoda</strong> end<strong>é</strong>mico.<br />

“Albendazole” – droga que destrói o germe adulto da filaria quando administrada 400<br />

mg, duas vezes <strong>por</strong> dia, durante duas semanas. Não tem acção directa contra<br />

microfilaria e não consegue diminuir os niveis de microfilaria. Esta droga quando em<br />

combinação com “diethylcarbamazine” ou “ivermectin” <strong>é</strong> recomendada n<strong>um</strong> programa<br />

global de eliminação da <strong>Filariose</strong>.

REFERÊNCIAS<br />

De Souza D. (2010). Environmental Factors Associated with the Distribution of<br />

Anopheles gambiae s.s in Ghana; an Im<strong>por</strong>tant Vector of Lymphatic Filariasis and<br />

Malaria. PLoS ONE Vol<strong>um</strong>e 5, Issue 3, e9927, 1-9.<br />

Mendoza N. et al. (2009). Filariasis: diagnosis and treatment. Dermathologic Theraphy<br />

vol. 22, 475-490.<br />

Pfarr K.M. et al. (2009). Filariasis and lymphoedema. Parasite Immunology 31, 664-<br />

672.<br />

Pal<strong>um</strong>bo E. (2008). Filariasis: diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Acta Biomed 79,<br />

106-109.<br />

WHO. Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis. Wkly Epidemiol Rec<br />

2006; 81: 221-232.<br />

WHO. Re<strong>por</strong>t on the mid-term assessment of microfilaraemia reduction in sentinel sites<br />

of 13 countries of the Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis. Wkly<br />

Epidem Rec 2004; 79: 358-365.<br />

http://www.searo.who.int/EN/Section10/Section2096_10601.htm

FILARIASIS<br />

Filariasis is a disease caused by filarial nematodes, which are the causative agents of<br />

lymphatic filariasis (LF), a secondary lymphoedema.<br />

Adult filarial parasites are worms sexually dimorphic and reside in the lymphatic<br />

vessels, where they mate and produce thousands of first-stage larvae (microfilaria) for<br />

up to 8 years.<br />

Filariae are very specific for their mammalian hosts and obligate intermediate vector<br />

species. Mosquito vectors from the genera Aedes, Anopheles, Culex, Simuli<strong>um</strong>,<br />

Chrysops or Mansonia are required for development of the larvae into the h<strong><strong>um</strong>a</strong>n<br />

infective stage, and for transmission to the h<strong><strong>um</strong>a</strong>n hosts.<br />

The vector ingest microfilaria during blood meals. In the insect, the larvae develop into<br />

infective larvae (L3), which are deposited on the skin of the h<strong><strong>um</strong>a</strong>ns during subsequent<br />

blood meals.<br />

The larvae enter in the body through the wound made by the insect and undergo two<br />

more moults to develop into adult worms, completing the cycle.<br />

Image credit: CDC/Alexander J. da Silva, PhD/Melanie Moser. (PHIL #3425), 2003.

EPIDEMIOLOGY<br />

This image is a work of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, part of the United<br />

States Department of Health and H<strong><strong>um</strong>a</strong>n Services, taken or made during the course of an<br />

employee's official duties. As a work of the U.S. federal government, the image is in the public<br />

domain.<br />

An estimated 120 million people are infected with the filarial nematodes Wuchereria<br />

bancrofti, Brugia malayi and Brugia timori, wich are the causative agents of lymphatic<br />

filariasis, and 1,3 billion people are estimated to be at risk of lymphatic filariasis.<br />

The disease affects approximately 83 countries mainly in sub-Saharan Africa, India,<br />

Southeast Asia, parts of South America, the Caribbean and the South Pacific.<br />

The infection is common in many areas of the tropics and approximately 70% of<br />

lymphatic filariasis is found in India, Nigeria, Indonesia and Bangladesh. Two-thirds of<br />

the affected people are in Asia.<br />

Among adults residents of endemic areas, 12.5% have clinical manifestations of<br />

lymphoedema and 21% of men have hydrocele, despite the fact that most individuals<br />

are pres<strong><strong>um</strong>a</strong>bly inoculated with L3 larvae throughout life.<br />

Filariasis tends to affect tropical and subtropical areas, common habitats for the<br />

vectorsof lymphatic filariasis, because surroundings of ambient h<strong>um</strong>idity are often<br />

necessary for the survival of the infective larval stage and the microfilariae. The<br />

majotiry of the case also occurs in rural areas and regions associated with poor<br />

sanitation and housing quality.

CLINICAL FINDINGS<br />

CLINICAL FINDINGS<br />

The infected patients have a high risk of developing chronic symptoms such<br />

lymphedema, elephantiasis, or blindness that can decrease the patient’s productivity and<br />

lead to life-threatening infections.<br />

Patients affected by microfilariaemia may present an asymptomatic infection or acute<br />

and chronic manifestations.<br />

In the endemic areas the majority of affected subjects show clinically asymptomatic<br />

infection and harbour microfilaria in their peripheral blood.<br />

Acute manifestations include acute adeno-lymphangitis (ADL) and acute filarial<br />

lymphangitis (AFL).<br />

ADL is the most common acute manifestation and is characterized by attacks of fever.

These episodes may occur both in early and late stage of the disease. The affected area<br />

is painful, tender, warm, red and swollen. The lymph nodes in the groin and axilla are<br />

frequently inflamed. These acute ADL attacks recur many times a year in patients with<br />

filarial swelling and their incidence increases with the degree of lymphoedema.<br />

Secondary infections due to bacteria such as streptococci are responsible for these acute<br />

episodes. In the affected limbs, lesions which favour entry of these infecting agents may<br />

be demonstrated, either in the form of minor injuries, eczema, insect bites or infections.<br />

These ADL attacks are responsible for the persistence and progression of the swelling<br />

leading to elephantiasis not only of the limbs but also of the external genitalia and<br />

breasts.<br />

AFL are caused by adult worms and are usually rare. They are observed when the adults<br />

worms are destroyed in the lymphatics.<br />

Small tender nodules form at the location of adult worm death either in the scrot<strong>um</strong> or<br />

along the lymphatics.Lymph node may became tender.<br />

Though transient oedema may sometimes occur, these episodes are not associated with<br />

fever, toxemia or evidence of secondary bacterial infection.<br />

The chronic manifestations represent lymphoedema and elephantiasis and genitourinary<br />

lesions.<br />

The most common chronic manifestation of lymphatic filariasis is lymphoedema, which<br />

may progress to elephantiasis.<br />

The affected areas are swollen, painful, and often have a bad smell, with the skin<br />

turning warty and thickened with folds and cracks. Ulcers and swelling can grow large<br />

enough to interfere with movement and drastically debilitate victims.<br />

In female, rarely the breasts and external genitalia may also became elephantoid.<br />

Hydrocoele is a common chronic manifestation of bancroftian filariasis in males.<br />

The subcutaneous filariasis present with papules, nodules and scratch marks.<br />

Subsequently, the skin becomes dry and thickened and may be associated with iper<br />

and/or hypo pigmentation. Pruritus is common and can be very severe.<br />

DIAGNOSIS<br />

The recent developments in the diagnosis are:<br />

• Membrane filtration method for microfilaria detection: venus blood drawn at<br />

night and filtered through mille<strong>por</strong>e membrane filters, enables an easy detection<br />

of microfilaria and quantifies the load of infection. A dose of<br />

diethylcarbamazine (DEC) can also provoke the microfilariae to appear during<br />

the daytime if necessary.<br />

• Skin snips: microfilariae from O. volvulus and M.streptocerca are best detected<br />

in a skin biopsy for subcutaneous filariases. Skin snips are highly specific and<br />

can be obtained using sclerocorneal punches or a needle and scalpel. Biopsies<br />

are taken from areas known to be highly infected, such as the iliac crest or the<br />

calves.<br />

• Radiographs can be used to identify the calcified remains of the dead worms in<br />

the tissue. The application is limited though, as it only detects dead adult worms.<br />

• Ultrasonography: recently has helped to locate and visualize the movement of<br />

living adult filarial worms of W. bancrofti in the scrotal lymphatics of<br />

asymptomatic male with microfilariaemia. This constant thrashing movement is<br />

known as the “filarial dance sign”. Ultrasonography is not useful in patients with<br />

filarial lymphoedema because living adult worms are generally not present at

this stage of the disease. Ultrasonography of the scrot<strong>um</strong> has not proved useful<br />

in patients with B. malayi infection because they do not involve the genitalia.<br />

• Lymphoscintigraphy: injection of radiolabelled alb<strong>um</strong>in or destran in the web<br />

space of the toes. This technique has shown that even in the early, clinically<br />

asymptomatic stage of the disease, lymphatic abnormalities in the affected limbs<br />

of people harboring microfilaria may occur.<br />

• Immunochromatographic test: highly sensitive and specific filarial antigen<br />

detection assays are available for the diagnosis of W. bancrofti infection.<br />

This test is positive in the early stage of the disease when the adult worms are<br />

alive and becomes negative once they are dead.<br />

• A highly sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-based format<br />

is available for the diagnosis of W.bancrofti infection; it takes longer to<br />

complete and is not convenient.<br />

• DNA probes using Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): this test is able to detect<br />

parasite DNA in the h<strong><strong>um</strong>a</strong>ns as well as vectors in both bancroftian and brugian<br />

filariasis.<br />

PREVENTION AND THERAPHY<br />

The Global Programme for the Elimination of Lymphatic Filariasis (GPELF) strives to<br />

eliminate LF as a public health concern by 2020 by breaking transmission of the<br />

microfilaria to uninfected persons in the community (http://www.filariasis.org).<br />

The programme is conducted by endemic countries with the help of WHO and<br />

n<strong>um</strong>erous nongovernment organizations (NGOs) and undertakes annual administration<br />

of antimicrofilarial drugs to eligible members of the affected community, i.e. mass drug<br />

administration (MDA).<br />

In the area where the filarial nematode Onchocerca volvulus is also endemic, the drug<br />

combination of ivermectin (IVM) and albendazole is administered.<br />

In areas where only W. bancrofti or Brugia spp. is present, diethylcarbamazine (DEC)<br />

and albendazole are administered.<br />

Both drugs IVM and DEC are effective at killing the microfilaria, but have limited,<br />

long-term effects on the adult worms.<br />

For these reasons , LYM-FASIM programme, which models transmission and control of<br />

LF, predicts that administration of the drugs for at least 8 years, ass<strong>um</strong>ing a coverage of<br />

> 65% of the affected population, is required.<br />

DEC: this drug is effective against both microfilaria and adult worms. Even though Dec<br />

kills the adults worms, this effect is only observed in 50% of patients. The earlier<br />

recommended single dose is 6 mg/kg; even in annual single dose it is a good tool to<br />

prevent the transmission.<br />

IVM: this drug acts directly on the microfilaria and in single doses of 200 to 400 µg/kg<br />

keeps the blood microfilaria counts at very low levels even after one year. It has no<br />

proven action against the adult parasite. It is the drug of choice for the treatment of<br />

onchocerciasis and for prevention in African countries endemic for Onchocerca.<br />

ALBENDAZOLE: destroy the adult filarial worms when given in dose of 400 mg<br />

twice a day for two weeks. It has not direct action against the microfilaria and does not<br />

immediately lower the microfilaria counts. It combined with DEC or IVM is<br />

recommended in the global filariasis elimination programme.

REFERENCES<br />

De Souza D. (2010). Environmental Factors Associated with the Distribution of<br />

Anopheles gambiae s.s in Ghana; an Im<strong>por</strong>tant Vector of Lymphatic Filariasis and<br />

Malaria. PLoS ONE Vol<strong>um</strong>e 5, Issue 3, e9927, 1-9.<br />

Mendoza N. et al. (2009). Filariasis: diagnosis and treatment. Dermathologic Theraphy<br />

vol. 22, 475-490.<br />

Pfarr K.M. et al. (2009). Filariasis and lymphoedema. Parasite Immunology 31, 664-<br />

672.<br />

Pal<strong>um</strong>bo E. (2008). Filariasis: diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Acta Biomed 79,<br />

106-109.<br />

WHO. Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis. Wkly Epidemiol Rec<br />

2006; 81: 221-232.<br />

WHO. Re<strong>por</strong>t on the mid-term assessment of microfilaraemia reduction in sentinel sites<br />

of 13 countries of the Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis. Wkly<br />

Epidem Rec 2004; 79: 358-365.<br />

http://www.searo.who.int/EN/Section10/Section2096_10601.htm<br />

Autoria: Elisa Crisci e Tradução: Andreia Serra