Edible-nest Swiftlet Collocalia fuciphaga: extinction by ... - Indian Birds

Edible-nest Swiftlet Collocalia fuciphaga: extinction by ... - Indian Birds

Edible-nest Swiftlet Collocalia fuciphaga: extinction by ... - Indian Birds

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

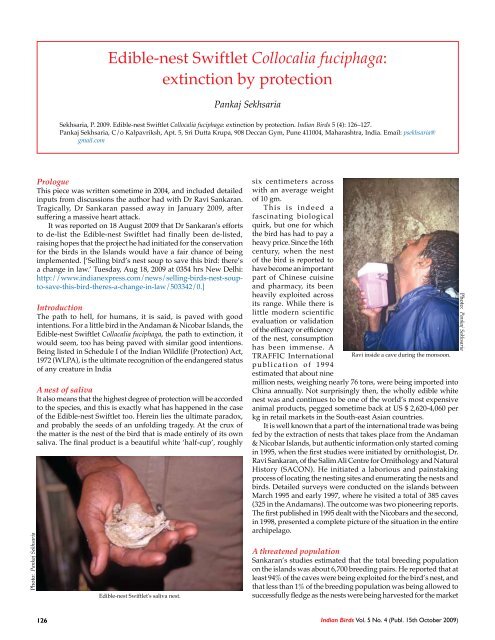

Sekhsaria: Extinction <strong>by</strong> protectionbefore the <strong>nest</strong>ing could be completed. Sankaran estimated thatthe <strong>Edible</strong>-<strong>nest</strong> <strong>Swiftlet</strong> had experienced a whopping 80% declinein its population, placing it in the critically threatened category(IUCN criteria A1c). This was primarily due to indiscriminateand unrestricted <strong>nest</strong> collection from the wild, leading him to thefurther conclusion that if this was not dealt with urgently the birdwould soon be extinct in the Andaman & Nicobar Islands.He initially advocated strict protection, but changed his standwhen he realised that protection, in the conventional sense, wouldnot work. He also learnt of the ingenious house ranching methodsdeveloped <strong>by</strong> the Indonesians for managing swiftlets.House ranchingIt was estimated that nearly 65,000 kg of <strong>nest</strong>s were being producedin Indonesia annually, from colonies of the <strong>Edible</strong>-<strong>nest</strong> <strong>Swiftlet</strong> thatreside within human habitation: a total of 5.5 million birds andtheir <strong>nest</strong>s, in houses and rooms of human habitations, optimallymanaged <strong>by</strong> humans. “Thus, while swiftlet populations in caveswill continue to decline, or become extinct, due to collectionpressures,” Sankaran concluded, “the species will survive becausethere are hundreds of thousands of birds that reside within humanhabitation, all optimally managed”.Nest collectors, he started to advocate, would have to beempowered to harvest <strong>nest</strong>s within the rigid framework ofstrictly scientifically harvesting regimes. This would have to becomplimented in the ‘Indonesian way’, with a realistic long-termstrategy that would include both in-situ and ex-situ conservationprogrammes, i.e., house ranching, both based on the economicimportance of the species and using this importance to organiselocal communities to conserve the species.In 1999, his recommendation took the form of an innovativeinitiative that was launched jointly <strong>by</strong> the Wildlife Circle of theDepartment of Environment and Forests, Andaman and NicobarIslands, and SACON. The final aim of the initiative was to ensureprotection of the <strong>nest</strong>s in the wild so that eggs would be availablefor the house ranching ex situ component. The project took offwell. Protection accorded to a complex of 28 caves on ChallisEk in North Andaman Island, and one cave on Interview IslandWildlife Sanctuary, saw over 3,000 chicks being fledged, a growthof over 25% in the population of the swiftlets at these sites. A teamof local people, who were earlier <strong>nest</strong> collectors, were now beingmotivated towards protection, and subsequently, sustainableharvesting.The law becomes the hurdleJust as phase one was taking off, the law came into the picture, andin October 2003 the <strong>Edible</strong>-<strong>nest</strong> <strong>Swiftlet</strong> was put onto ScheduleI of the Wildlife Act. This meant that there could be no activitythat involved use of, or trade in the <strong>nest</strong> of the bird—the primarypremise on which Sankaran’s initiative had been based. The entireproject was dealt a set back and in spite of continued efforts,over the years, to have the swiftlet removed from Schedule I, itcontinues to be listed there.Admittedly there are genuine concerns about the de-listing ofa species and the implications of an act of this kind. The biggestfear is of setting a precedent that could be misused <strong>by</strong> vestedinterests. In this case however, the recommendations are basedon solid, detailed, and pioneering scientific studies of nearly adecade, and were in turn backed with a wealth of internationalinformation and experience. “Its more like apiculture,” wouldbe Sankaran’s argument, “where bees are reared for their honey.House ranching of swiftlets cannot be likened to the farming ofanimals for skin or meat”. The implication of not delisting the birdis that the conservation initiative is bound to fail, while harvestingfrom the wild would continue unabated. The consequences ofthis would be the local <strong>extinction</strong> of the bird in the Andaman& Nicobar Islands—a predicament that was summed up withstunning simplicity <strong>by</strong> J. C. Daniel of the Bombay NaturalHistory Society. Speaking during the concluding session of theInternational Seminar to commemorate the centenary Journal ofthe Bombay Natural History Society in Mumbai in November2003, he spoke of the fate of the <strong>Edible</strong>-<strong>nest</strong> Swiflet if correctiveaction was not taken at the earliest: <strong>extinction</strong> <strong>by</strong> protection—theultimate oxymoron.Ravi with his field staff andwife Deepa at the <strong>Edible</strong><strong>nest</strong><strong>Swiftlet</strong> Camp, ChallisEk, North Andaman Island.(Challis Ek translates as'41'—which is the number ofcaves in this cave complexwhere the swiftlets arefound). At extreme left isAlex, Ravi's man Friday.They worked together for avey long time and, like wasRavi's way of working, theyalso became close familyfriends.Photo: Pankaj Sekhsaria<strong>Indian</strong> <strong>Birds</strong> Vol. 5 No. 4 (Publ. 15th October 2009)127