Catalogo - Mostra internazionale del nuovo cinema

Catalogo - Mostra internazionale del nuovo cinema

Catalogo - Mostra internazionale del nuovo cinema

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

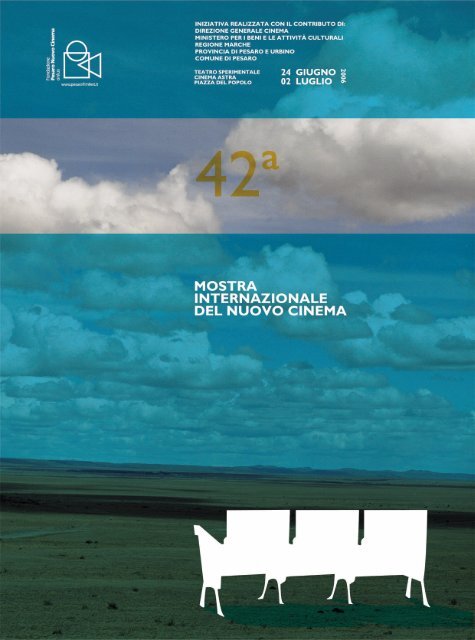

CATALOGO DELLA 42 a MOSTRA INTERNAZIONALE DEL NUOVO CINEMA<br />

a cura di Mazzino Montinari<br />

con la collaborazione di Alice Arecco e Iris Martín-Peralta<br />

Traduzioni in inglese di Natasha Senjanovic<br />

AVVERTENZA<br />

Le abbreviazioni usate significano: doc (documentario); cm (cortometraggio); mm (mediometraggio);<br />

b/n (bianco&nero).<br />

© 2006 Fondazione Pesaro Nuovo Cinema Onlus<br />

Via Villafranca, 20<br />

00185 Roma<br />

Finito di stampare<br />

nel mese di giugno 2006<br />

presso la tipografia Lineagrafica - Roma

LA MOSTRA INTERNAZIONALE DEL NUOVO CINEMA<br />

È STATA REALIZZATA CON IL CONTRIBUTO DI

Fondazione Pesaro Nuovo Cinema Onlus<br />

42a MOSTRA INTERNAZIONALE<br />

DEL NUOVO CINEMA<br />

Pesaro, 24 giugno – 2 luglio 2006

FONDAZIONE<br />

PESARO NUOVO CINEMA Onlus<br />

Soci fondatori<br />

Comune di Pesaro<br />

Luca Ceriscioli, Sindaco<br />

Provincia di Pesaro e Urbino<br />

Palmiro Ucchielli, Presidente<br />

Regione Marche<br />

Gian Mario Spacca, Presidente<br />

Fiorangelo Pucci, Delegato<br />

Consiglio di Amministrazione<br />

Luca Ceriscioli, Presidente<br />

Luca Bartolucci, Gianaldo Collina, Alessandro Fattori,<br />

Simonetta Marfoglia, Franco Marini, Ornella Pucci,<br />

Paolo Sorcinelli, Aldo Tenedini<br />

Segretario generale<br />

Ennio Braccioni<br />

Amministrazione<br />

Lorella Megani<br />

Coordinamento<br />

Viviana Zampa<br />

42a MOSTRA INTERNAZIONALE DEL NUOVO<br />

CINEMA<br />

Comitato Scientifico<br />

Bruno Torri, Presidente<br />

Adriano Aprà, Pedro Armocida, Pierpaolo Loffreda,<br />

Giovanni Spagnoletti, Vito Zagarrio<br />

Direzione artistica<br />

Giovanni Spagnoletti<br />

Direzione organizzativa<br />

Pedro Armocida<br />

Assistente alla programmazione e ricerca film<br />

Alice Arecco<br />

con la collaborazione di Gabriella Guido<br />

Segreteria<br />

Maria Grazia Chimenz<br />

Ufficio Documentazione e <strong>Catalogo</strong><br />

coordinamento presentazione libri<br />

Mazzino Montinari<br />

con la collaborazione di Iris Martín-Peralta<br />

Movimento copie<br />

Anthony Ettorre<br />

con la collaborazione di Claudia Barucca<br />

Accrediti e ospitalità<br />

Michela Paoletti<br />

con la collaborazione di Erika Silvya Jemmett<br />

Ufficio stampa<br />

Studio Morabito<br />

Mimmo Morabito (responsabile)<br />

Rosa Ardia (assistente)<br />

con la collaborazione di<br />

Roberto Donati, Azzurra Proietti<br />

Stampa regionale<br />

Beatrice Terenzi<br />

Nuove proposte video e Documentando, focus Andrea Caccia e<br />

Antonello Matarazzo<br />

Andrea Di Mario<br />

Corrispondente in Francia<br />

Silvia Angrisani<br />

Corrispondente in Germania<br />

Olaf Möller<br />

Corrispondente per la Corea<br />

Davide Cazzaro<br />

Sito internet<br />

Claudio Gnessi<br />

Database generale su www.pesarofilmfest.it<br />

Luca Franco<br />

Realizzazione immagini su internet<br />

Barbara Faonio<br />

Traduzioni<br />

dall’inglese Paola Fragalà, Alessandra Grieco<br />

dallo spagnolo Iris Martín-Peralta, Simonetta Santoro<br />

Collaborazione alla sezione “Leonardo Favio e <strong>cinema</strong> argentino<br />

contemporaneo”<br />

Pedro Armocida, Daniele Dottorini<br />

Collaborazione alla retrospettiva “Pere Portabella”<br />

Pedro Armocida, Lorenza Pignatti<br />

Collaborazione alla sezione “Doc Usa”<br />

Gabriella Guido<br />

Collaborazione alla sezione “Nuovo <strong>cinema</strong> Filippino”<br />

Khavn, Olaf Möller<br />

Coordinamento conferenze stampa e concorso video<br />

Pierpaolo Loffreda<br />

Giuria Concorso Video: “L’Attimo Fuggente”<br />

Paolo Angeletti, Claudio Salvi, Gualtiero De Santi,<br />

Alberto Pancrazi, Fiorangelo Pucci<br />

Traduzioni simultanee<br />

Anna Ribotta, Simonetta Santoro, Marina Spagnuolo<br />

Progetto di comunicazione<br />

33 Multimedia Studio - Pesaro<br />

Coordinamento proiezioni<br />

Gilberto Moretti<br />

Consulenza assicurativa<br />

I.I.M. di Fabrizio Volpe, Roma<br />

Trasporti<br />

Stelci & Tavani, Roma<br />

Ospitalità<br />

A.P.A., Pesaro<br />

Sottotitoli elettronici<br />

Napis, Roma - napis@napis.it<br />

Allestimento “Cinema in piazza” e impianti tecnici<br />

L’image s.r.l., Padova<br />

Pubblicità<br />

Dario Mezzolani<br />

Viaggi<br />

Playtime <strong>del</strong>la EDO Viaggi Srl, Roma<br />

MOSTRA INTERNAZIONALE<br />

DEL NUOVO CINEMA<br />

Via Villafranca, 20 - 00185 Roma<br />

tel. (+39) 06 491156 / (+39) 06 4456643<br />

fax (+39) 06 491163<br />

www.pesarofilmfest.it<br />

e-mail: pesarofilmfest@mclink.it<br />

info@pesarofilmfest.it

Si ringraziano<br />

01 Distribution<br />

3-H Productions (Chang Chuti)<br />

Suzanne Ackerman<br />

Ambasciata Argentina<br />

AMIP (Xavier Carniaux, Aurélie Pauvert)<br />

Silvia Angrisani<br />

BD Cine (Patricia Pesch)<br />

Cis Bierinckx<br />

Birchtree Entertainement (Art Birzneck)<br />

Cattleya (Riccardo Tozzi, Marco Chimenz, Sonia Dichter)<br />

Davide Cazzaro<br />

Classic (Irene Renzato)<br />

Compass Films<br />

Documé (Giuliano Girelli)<br />

Dworkin Stefanie<br />

ENI<br />

Sergio Fant<br />

Festival Internacional de Cine de Mar <strong>del</strong> Plata (Miguel<br />

Pereira)<br />

Filmex Film (Doina Dragnea)<br />

Films Distribution (Paméla Leu)<br />

Forum des Images – Paris (Sarah Ziegler)<br />

Helena Gomá<br />

Illuminations Films (Keith Griffiths)<br />

INCAA (Sandra Lamponi, Xavier Capra)<br />

Nel complesso <strong>del</strong> sistema audiovisivo italiano, i festival rappresentano<br />

un soggetto fondamentale per la promozione, la conoscenza e la diffusione<br />

<strong>del</strong>la cultura <strong>cinema</strong>tografica e audiovisiva, con un’attenzione<br />

particolare alle opere normalmente poco rappresentate nei circuiti commerciali<br />

come ad esempio il documentario, il film di ricerca, il cortometraggio.<br />

E devono diventare un sistema coordinato e riconosciuto dalle<br />

istituzioni pubbliche, dagli spettatori e dagli sponsor.<br />

Per questo motivo e per un concreto spirito di servizio è nata nel novembre<br />

2004 l’Associazione Festival Italiani di Cinema (Afic). Gli associati<br />

fanno riferimento ai principi di mutualità e solidarietà che già hanno<br />

ispirato in Europa l’attività <strong>del</strong>la Coordination Européenne des Festivals.<br />

Inoltre, accettando il regolamento, si impegnano a seguire una<br />

serie di indicazioni deontologiche tese a salvaguardare e rafforzare il<br />

loro ruolo.<br />

L’Afic nell’intento di promuovere il sistema festival nel suo insieme,<br />

rappresenta già oggi più di trenta manifestazioni <strong>cinema</strong>tografiche e<br />

audiovisive italiane ed è concepita come strumento di coordinamento e<br />

reciproca informazione.<br />

Aderiscono all’Afic le manifestazioni culturali nel campo <strong>del</strong>l’audiovisivo<br />

caratterizzate dalle finalità di ricerca, originalità, promozione dei<br />

talenti e <strong>del</strong>le opere <strong>cinema</strong>tografiche nazionali ed internazionali.<br />

L’Afic si impegna a tutelare e promuovere, presso tutte le sedi istituzionali,<br />

l’obiettivo primario dei festival associati.<br />

Associazione Festival Italiani di Cinema (Afic)<br />

www.aficfestival.it<br />

Via Villafranca, 20<br />

00185 Roma<br />

Italia<br />

Institut Ramon Llull<br />

Instituto Cervantes<br />

Inter<strong>cinema</strong> XXI Century (Nadia Gus)<br />

Istituto Italiano di Cultura di Buenos Aires<br />

Giulio Latini<br />

Locomotion Films<br />

Lucky Red (Georgette Ranucci)<br />

MACBA<br />

Minimun Fax Media (Rosita Bonanno, Ken Sparrow,<br />

Margherita Bianchini)<br />

Ma<strong>del</strong>eine Molyneaux<br />

Giovanni Ottone<br />

Peter Rommel Productions (Peter Rommel, Jana Cisar)<br />

Antonio Pezzuto<br />

Primer Plano<br />

Armando Pronzato<br />

Rai Cinema<br />

Donald Ranvaud<br />

García Ximena Rodriguez<br />

Romanian Film Centre (Alina Salcudeanu)<br />

Diana Rulli<br />

Sixpackfilm (Brigitta Burger-Utzer, Ute Katschthaler)<br />

The Match Factory (Philipp Hoffmann)<br />

UNIST (Marco Fortunato)<br />

Nuria Vidal<br />

Warner Bros<br />

Within the framework of the Italian audiovisual system, film festivals are<br />

fundamental in the promotion, awareness and diffusion of <strong>cinema</strong> and<br />

audiovisual culture, as they pay particular attention to work that is<br />

usually not represented by commercial circuits, such as, for example,<br />

documentaries, experimental films and short films. And they must become<br />

a system that is coordinated and recognized by public institutions, spectators<br />

and sponsors alike.<br />

For this reason, and in the explicit spirit of service, the Association of Italian<br />

Film Festivals (Afic) was founded in November, 2004. The members<br />

follow the ideals of mutual assistance and solidarity that are the guiding<br />

principles of the Coordination Européenne des Festivals and, upon accepting<br />

the Association's regulations, furthermore strive to adhere to a series<br />

of ethical indications aimed at safeguarding and reinforcing their role.<br />

In its objective to promote the entire festival system, the Afic already<br />

represents over thirty Italian film and audiovisual events and was conceived<br />

as an instrument of coordination and the reciprocal exchange of<br />

information.<br />

The festivals that are part of the Afic are characterized by their search for<br />

the new, originality, and the promotion of talent and national and international<br />

films.<br />

The Afic is committed to protecting and promoting, through all of its<br />

institutional branches, the primary objective of the member festivals.<br />

Associazione Festival Italiani di Cinema (Afic)<br />

www.aficfestival.it<br />

Via Villafranca, 20<br />

00185 Roma<br />

Italia

IL PROGRAMMA MEDIA DELLA COMMISSIONE EUROPEA<br />

A SOSTEGNO DEI FESTIVAL CINEMATOGRAFICI<br />

THE MEDIA PROGRAMME OF THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION SUPPORTED AUDIOVISUAL FESTIVALS<br />

Anche se fugaci momenti di festa e di incontro, i festival di <strong>cinema</strong> e di<br />

televisione svolgono un ruolo estremamente importante nella promozione<br />

dei film europei. Tali eventi presentano un numero considerevole di produzioni<br />

audiovisive, costituendo un punto di passaggio quasi obbligato<br />

nella commercializzazione <strong>del</strong>le opere: senza i festival migliaia di film e<br />

video resterebbero invenduti, in mancanza di acquirenti. Attualmente, il<br />

numero di spettatori che vi partecipano – due milioni – garantisce il loro<br />

reale impatto economico, senza parlare <strong>del</strong> ruolo da essi svolto sul piano<br />

culturale, sociale ed educativo che sta producendo crescenti livelli di<br />

impiego diretto e indiretto in tutta Europa.<br />

È ovvio che il Programma MEDIA <strong>del</strong>la Commissione Europea sostenga<br />

queste manifestazioni, cercando di migliorare le condizioni per la distribuzione<br />

e la promozione <strong>del</strong>le opere <strong>cinema</strong>tografiche europee in tutto il<br />

continente. A tale scopo, esso aiuta più di cento festival che beneficiano di<br />

un supporto finanziario di oltre 2 milioni di Euro. Ogni anno, grazie all’azione<br />

di questi festival e al contributo <strong>del</strong>la Commissione, vengono proiettate<br />

circa 10.000 opere audiovisive che illustrano la ricchezza e la diversità<br />

<strong>del</strong>le <strong>cinema</strong>tografie europee. L’ingresso nel Programma, a partire dal<br />

2004, di dodici nuovi paesi – Lettonia, Estonia, Polonia, Bulgaria, Repubblica<br />

Ceca, Ungheria, Slovacchia, Slovenia, Lituania, Malta, Cipro e Svizzera<br />

- contribuisce ad aumentare i risultati di questo lavoro.<br />

Inoltre, la Commissione sostiene ampiamente la messa in rete dei suddetti<br />

festival. In tale settore, le attività <strong>del</strong> Coordinamento Europeo dei Festival<br />

di Cinema favoriscono la cooperazione tra manifestazioni, rafforzando il<br />

loro impatto attraverso lo sviluppo di operazioni comuni.<br />

Domenico RANERI<br />

Responsabile Programma MEDIA<br />

Programma MEDIA, partner <strong>del</strong>la <strong>Mostra</strong> Internazionale <strong>del</strong> Nuovo<br />

Cinema, 42ª edizione, 2006<br />

Commissione Europea<br />

Programma MEDIA II - festival audiovisivi<br />

EAC – T120 1/74<br />

B-1049 Brussels<br />

Tel. +32 2 295 95 30 o Fax + 32 2 299 92 14<br />

Il Coordinamento europeo dei Festival <strong>del</strong> Cinema riunisce più di 170<br />

manifestazioni dedicate a differenti tematiche e formati, tutte impegnate<br />

nella difesa <strong>del</strong> <strong>cinema</strong> europeo. Questi festival rappresentano, con alcune<br />

eccezioni, l’insieme dei paesi <strong>del</strong>la Comunità Europea.<br />

Il Coordinamento sviluppa una serie di azioni comuni e di cooperazioni a<br />

beneficio dei membri, nella prospettiva di valorizzare le <strong>cinema</strong>tografie<br />

europee e di migliorare la loro diffusione e la conoscenza presso il pubblico.<br />

Al di là di queste azioni comuni, il Coordinamento incoraggia inoltre le<br />

cooperazioni bilaterali e multilaterali tra i suoi membri.<br />

Il Coordinamento ha elaborato un codice deontologico, adottato dall’insieme<br />

dei suoi membri, che mira a armonizzare il lavoro dei festival.<br />

Il Coordinamento è anche un centro di documentazione e incontro tra i<br />

festival.<br />

Coordination Européenne<br />

des Festival de Cinéma GEIE<br />

64, rue Philippe Le Bon<br />

B-1000 Bruxelles<br />

Belgique<br />

Fleeting times of celebration and encounters, film and television festivals nevertheless<br />

play an extremely important role in the promotion of European films. These<br />

events screen a considerable number of audiovisual productions, acting as a near<br />

obligatory means of securing commercial success: without festivals thousands of<br />

films and videos would remain, buyer-less, on the shelves. The number of spectators<br />

now drawn to festivals – two million – ensures their real economic impact not<br />

to mention their cultural, social and educational role, creating increasing levels of<br />

direct and indirect employment across Europe.<br />

It is evident that the MEDIA Programme of the European Commission supports<br />

these events, endeavouring to improve the conditions for the distribution and promotion<br />

of European <strong>cinema</strong>tographic work across Europe. To this end, it aids more<br />

than 100 festivals, benefiting from over 2 million Euros in financial aid. Each<br />

year, thanks to their actions and the Commission’s support, around 10 000 audiovisual<br />

works, illustrating the richness and the diversity of European <strong>cinema</strong>tographies,<br />

are screened. The entrance since 2004 into the Programme of twelve new<br />

countries – Latvia, Estonia, Poland, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia,<br />

Slovenia, Lithuania, Malta, Cyprus and Switzerland - contributes to<br />

increasing the fruits of this labour.<br />

In addition, the Commission supports the networking of these festivals. In this<br />

area, the activities of the European Coordination of Film Festivals encourage cooperation<br />

between events, strengthening their impact in developing joint activities.<br />

Domenico RANERI<br />

Acting Head of Unit, MEDIA Programme<br />

The MEDIA Programme, partner<br />

of the 42nd <strong>Mostra</strong> Internazionale <strong>del</strong> Nuovo Cinema, 2006<br />

European Commission<br />

MEDIA II Programme – audiovisual festivals<br />

EAC – T120 1/74<br />

B-1049 Brussels<br />

Tel. +32 2 295 95 30 o Fax + 32 2 299 92 14<br />

The European Coordination of Film Festival is composed of 170 festivals of different<br />

themes and sizes, all dedicated to promoting European Cinema. All member<br />

countries of the European Union are represented, as well as some other European<br />

countries.<br />

The Coordination develops common activities for its members through cooperation,<br />

aimed at promoting European Cinema, improving circulation and raising<br />

public awareness.<br />

Besides these common activities, the Coordination also encourages bilateral and<br />

multilateral projects among its members.<br />

The Coordination has created a code of ethics, which has been adopted by all its<br />

members, to encourage common professional practise.<br />

The Coordination is also an information centre and a place for festivals to meet.<br />

European Coordination<br />

of Film Festivals GEIE<br />

64, rue Philippe Le Bon<br />

B-1000 Brussels<br />

Belgium

INDICE<br />

9 INTRODUZIONE<br />

di Giovanni Spagnoletti<br />

13 SELEZIONE UFFICIALE<br />

Concorso Pesaro Nuovo Cinema - Premio Lino Miccichè & Cinema in Piazza<br />

20° Evento Speciale: La Meglio Gioventù – Nuovo Cinema Italiano 2000-2006<br />

31 RETROSPETTIVE<br />

31 Il <strong>cinema</strong> argentino contemporaneo<br />

65 Leonardo Favio<br />

81 Pere Portabella<br />

109 Focus on Independent US Docs<br />

123 Filipino Digital<br />

145 EVENTI SPECIALI<br />

161 NUOVE PROPOSTE VIDEO & DOCUMENTANDO<br />

163 Andrea Caccia<br />

178 Antonello Matarazzo<br />

200 CONCORSO VIDEO “L’ATTIMO FUGGENTE”<br />

201 VIDEO DAL LEMS<br />

202 VIDEO DALL’ACCADEMIA DI BELLE ARTI DI URBINO<br />

205 INDICE DEI REGISTI E DEI FILM

Pesaro 2006:<br />

Un’introduzione al programma<br />

di Giovanni Spagnoletti<br />

Dopo Giappone, Spagna, Francia, Messico e Corea, quest’anno<br />

è l’Argentina il paese al centro <strong>del</strong> programma <strong>del</strong>la<br />

<strong>Mostra</strong> <strong>del</strong> Nuovo Cinema di Pesaro che si augura dal <strong>nuovo</strong><br />

governo, è un auspicio generalizzato, un rinnovato interesse<br />

per la cultura in generale e il <strong>cinema</strong> in particolare.<br />

Storici e antichi legami con la nazione latino-americana<br />

nonché con il nostro Festival (ricordiamo soltanto la presentazione<br />

<strong>del</strong>la seminale opera di Fernando Solanas e<br />

Octavio Getino L’ora dei forni nel 1968) imponevano una<br />

scelta <strong>del</strong> genere. Da un decennio a questa parte, infatti, e<br />

a partire da una nuova legge sul <strong>cinema</strong> varata nel 1995, si<br />

è assistito alla nascita di una “nuova onda argentina”, la<br />

quale si è espressa, ormai da tempo, nell’opera variegata di<br />

diversi autori (ne ricordiamo qui solo alcuni: Lisandro<br />

Alonso, Daniel Burman, Israel Adrián Caetano, Lucrecia<br />

Martel, Martín Rejtman, Bruno Stagnaro e Pablo Trapero)<br />

diventati ospiti fissi di tutti i Concorsi e festival internazionali.<br />

Tuttavia c’è molto ma molto di più da scoprire e lo<br />

vorremmo dimostrare con la presente panoramica che –<br />

evitando titoli già molto conosciuti o passati ai Festival di<br />

Torino e Venezia (oppure addirittura distribuiti nel nostro<br />

paese com’è l’opera di Lucrecia Martel) – propone registi o<br />

debutti meno noti accanto ai nomi precedentemente citati.<br />

Perché scrive in questo stesso catalogo Daniele Dottorini:<br />

“è una <strong>cinema</strong>tografia problematica, quella argentina; problematica<br />

anzitutto da un punto di vista critico: a più di<br />

dieci anni dall’esplosione <strong>del</strong>la nuova generazione di registi,<br />

quella che sembrava essere una corrente <strong>cinema</strong>tografica<br />

dai tratti definiti e comuni si è invece rivelata come<br />

una ondata dinamica e multiforme”.<br />

Una nuova onda, dunque, che si è andata inserendo in un<br />

tessuto socio-politico sconvolto dalla devastante crisi economica<br />

<strong>del</strong> 2001 e che sta compiendo una lenta ma inevitabile<br />

”elaborazione <strong>del</strong> lutto” di altri precedenti drammatici<br />

episodi: dall’insorgere <strong>del</strong>la dittatura militare (di cui<br />

quest’anno ricorre il trentennale <strong>del</strong>l’inizio nel 1976) alla<br />

guerra <strong>del</strong>la Malvinas (1982) che ha indirettamente provocato<br />

nel 1983 la fine di quella tragica esperienza. Con più<br />

di una ventina di titoli tra fiction e non fiction che spaziano<br />

per gli ultimi quattro-cinque anni salvo una eccezione –<br />

il primo programma storico di cortometraggi Historias breves<br />

(1995) – vogliamo mostrare un panorama che non limiti<br />

il <strong>cinema</strong> argentino contemporaneo all’interno di pochi<br />

schemi estetico-produttivi come l’iperrealismo, il minimalismo,<br />

la quotidianità <strong>del</strong>le storie, l’uso <strong>del</strong> digitale o il low<br />

budget. Anche questo ma molto di più, quale conseguenza,<br />

forse, <strong>del</strong> rifiuto di cercare (a ragione o a torno, non<br />

importa) un punto di collegamento con importanti esperienze<br />

passate <strong>del</strong> proprio paese. Con l’effetto – per citare<br />

sempre Dottorini – di spingere “i giovanissimi registi degli<br />

anni 2000 ad inventare un percorso che è aperto a 360 gradi,<br />

che è attento alla contemporaneità <strong>del</strong> continente latinoamericano<br />

e al contempo assorbe luoghi, ritmi e immagini<br />

dalle <strong>cinema</strong>tografie più disparate, occidentali e non<br />

(così come dalle forme e dai tempi televisivi)”.<br />

Pesaro 2006:<br />

An introduction to the program<br />

by Giovanni Spagnoletti<br />

After Japan, Spain, France, Mexico and Korea, this year<br />

Argentina is at the heart of the Pesaro Film Festival, which<br />

hopes the country’s new government will show a renewed<br />

interest in culture in general and <strong>cinema</strong> in particular.<br />

Historical and ancient bonds between the South American<br />

country and our festival (we cite only the presentation of the<br />

seminal work by Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino, The<br />

Hour of the Furnaces, in 1968) compelled this choice. For the<br />

past decade, in fact, and starting with a new <strong>cinema</strong> law implemented<br />

in 1995, we have been witnessing the birth of an<br />

"Argentinean new wave," which has been expressed through<br />

the diverse films of various filmmakers (to name but a few:<br />

Lisandro Alonso, Daniel Burman, Israel Adrián Caetano,<br />

Lucrecia Martel, Martín Rejtman, Bruno Stagnaro and Pablo<br />

Trapero) who have become regular guests at all festivals and<br />

competitions worldwide. Nevertheless, there is much more to<br />

discover and we would like to offer a panorama that – avoiding<br />

titles already screened at the Turin and Venice Film Festivals<br />

(or even distributed in our country, such Martel’s film) – presents<br />

lesser-known directors or debuts alongside the aforementioned<br />

filmmakers. As Daniele Dottorini writes in this catalogue:<br />

"Argentinean <strong>cinema</strong> is problematic, above all from a<br />

critical point of view. More than ten years after the explosion<br />

of a new generation of directors, what seemed to be a <strong>cinema</strong>tic<br />

trend of definite and shared traits was instead revealed to be<br />

a dynamic and variegated wave."<br />

There is a new wave then, which was inserted into the sociopolitical<br />

fabric thrown into turmoil by the devastating economic<br />

crisis of 2001 and that is going through a slow but<br />

inevitable "elaboration of mourning" of other, earlier dramatic<br />

episodes: from the rise of the military dictatorship (this year<br />

marks the 30th anniversary of its beginnings in 1976) to the<br />

war in the Malvinas (1982), which in 1983 indirectly brought<br />

about the end of this tragic experience. With over 20 fiction and<br />

non-fiction titles of the last 4-5 years, barring one exception –<br />

the first historical program of short films Historias breves<br />

(1995) – we want to offer a selection that does not limit contemporary<br />

Argentinean <strong>cinema</strong> to a few aesthetic-production<br />

mo<strong>del</strong>s such as hyper-realism, minimalism, the everyday<br />

nature of the stories, the use of digital or low budgets. This and<br />

much, much more is a consequence of the refusal to seek (rightfully<br />

or not, it makes no difference) connections to the important<br />

experiences of the country’s past and in turn produced the<br />

effect, to cite Dottorini once again, of driving "the young directors<br />

of the current decade to invent an entirely open path attentive<br />

to the contemporaneity of Latin America while simultaneously<br />

absorbing places, rhythms and images from the most disparate<br />

types of <strong>cinema</strong>, western and otherwise, as well as from<br />

the forms and rhythms of television."<br />

Topping off this wide selection, which includes feature and documentary<br />

films by, among others, Ana Katz, Luis Ortega (two<br />

films), Ana Poliak, Albertina Carri, Darío Doria, Raúl Perrone,<br />

Alejandro Chomski, Alejandro Malowicki, the festival<br />

presents, along with the latest film by Fernando Birri (in the<br />

42 a <strong>Mostra</strong> Internazionale <strong>del</strong> Nuovo Cinema 9

A coronamento di questo ampio cartellone, dove si propongono<br />

opere o documentari, tra gli altri, di Ana Katz,<br />

Luis Ortega (due film), Ana Poliak, Albertina Carri, Darío<br />

Doria, Raúl Perrone, Alejandro Chomski, Alejandro Malowicki,<br />

la <strong>Mostra</strong> presenta, insieme all’ultimo film di Fernando<br />

Birri (negli “Eventi Speciali”) – uno dei “padri” <strong>del</strong><br />

<strong>cinema</strong> latino-americano – anche la retrospettiva <strong>del</strong>l’opera<br />

di Leonardo Favio. Tra i più significativi registi (e cantanti)<br />

<strong>del</strong>la generazione espressasi negli anni anni ’60, nonché<br />

figura di culto per molti giovani filmmaker di oggi, Favio è<br />

stato attore in diversi film di Leopoldo Torre Nilsson, ha<br />

partecipato in maniera informale al movimento dei “cortisti”<br />

con El amigo (1960, perduto); poi dopo il debutto nel<br />

lungometraggio Crónica de un niño solo (presentato alla prima<br />

mostra di Pesaro nel 1965), ha diretto sei film di fiction<br />

nonché un lungo documentario (1994-2000) sulla fondamentale<br />

figura di Juan Domingo Perón, attualmente indisponibile<br />

per problemi politico-produttivi. Infine, last but<br />

non least, la mostra fotografica di Valerio Bispuri dal titolo<br />

“Argentina si parte...” che in 30 istantanee attraversa e racconta<br />

il paese latino-americano dalla crisi <strong>del</strong> 2001.<br />

Passando da un punto all’altro <strong>del</strong> continente americano e<br />

proseguendo un interesse che la <strong>Mostra</strong> da qualche anno<br />

sta coltivando nei confronti <strong>del</strong>la non-fiction, ecco il<br />

“Focus on Independent US Docs” che documenta le nuove<br />

tendenze “Indi” statunitensi in un settore sempre più in<br />

espansione. In linea con l’approccio politico-sperimentale<br />

<strong>del</strong> nostro Festival, la selezione vuole privilegiare uno<br />

sguardo “altro” e nascosto, non solo rivolto ai grandi temi<br />

<strong>del</strong>la Nazione e più frequentato dalle produzioni mainstream.<br />

Al viaggio all’inferno di Laura Poitras (My<br />

Country, My Country) che analizza l’Iraq <strong>del</strong>le prime elezioni<br />

post Saddam tramite gli occhi di un medico sunnita,<br />

si somma l’altra faccia di una medaglia violenta, esibita nel<br />

“kubrickiano” Ears Open, Eyeballs Click di Canaan Brumley<br />

(vera provocazione <strong>del</strong> Festival!) che ci catapulta in modo<br />

scioccante e brutale in un campo d’addestramento dei<br />

marines. Ma c’è <strong>del</strong>l’altro dentro l’America, ad esempio le<br />

sottoculture rappresentate dal mondo dei graffiti di Bill<br />

Daniel (Who’s Bozo Texino?) e quello dei “drug racing” di<br />

Kevin Jerome Everson (Cinnamon). E non manca il passato<br />

prossimo sia con la rievocazione <strong>del</strong>l’esperienza <strong>del</strong>la Factory<br />

wahroliana in Jack Smith & The Destruction of Atlantis<br />

di Mary Jordan, autentica chicca <strong>del</strong>la nostra selezione, sia<br />

con l’incursione di Sam Green (Lot 63, Grave C) che, con un<br />

found footage, ritorna sul celebre omicidio degli Hell’s<br />

Angels avvenuto durante il concerto dei Rolling Stones ad<br />

Altamont nel 1969.<br />

Proseguendo nell’opera di approfondimento <strong>del</strong> <strong>cinema</strong><br />

iberico iniziata da alcuni anni, una seconda personale è<br />

dedicata alla figura <strong>del</strong> catalano Pere Portabella, già in passato<br />

ospite <strong>del</strong> nostro Festival. Nato come produttore (Los<br />

golfos di Carlos Saura, El cochecito di Marco Ferreri, Viridiana<br />

di Luis Buñuel, e il più recente Tren de sombras di José<br />

Luís Guerin), Portabella è diventato nel proseguo <strong>del</strong>la sua<br />

lunga carriera un autore polisemico fuori dal sistema classico<br />

<strong>del</strong> lungometraggio a soggetto. Il suo è un opus che,<br />

rivisitando il concetto di realismo alla luce di un <strong>cinema</strong><br />

polifonico, attinge e si contamina con le varie arti: in primis<br />

la pittura (i suoi quattro lavori su Miró), la musica (Play-<br />

10<br />

Special Events section) – one of the "fathers" of Latin American<br />

<strong>cinema</strong> – a retrospective on Leonardo Favio. One of the<br />

most significant directors (and singers) of the generation that<br />

emerged in the 1960s, as well as a cult figure for many of<br />

today’s young filmmakers, Favio acted in numerous films by<br />

Leopoldo Torre Nilsson and was also informally involved in the<br />

"shorts" movement with El amigo (1960, which was lost).<br />

After his feature debut Crónica de un niño solo (screened at<br />

the first Pesaro Film Festival in 1965), he later directed six<br />

more features as well as one lengthy documentary (1994-2000)<br />

on Juan Domingo Perón, currently unavailable due to political-production<br />

problems. We are also proud to present a photography<br />

exhibit of the work of Valerio Bispuri, entitled<br />

"Argentina si parte...", which in 30 photographs offers a crosssection<br />

and portrayal of the South American country during<br />

the 2001 crisis.<br />

Passing from one side of the American continent to the other,<br />

and in keeping with the interest that the festival has been nurturing<br />

for non-fiction for several years, the Focus on Independent<br />

US Docs looks at the new "indie" trends in an ever-growing<br />

field. In line with our festival’s political-experimental<br />

approach, this selection favors a "different" and hidden perspective<br />

that turns its gaze on themes other than the main topics<br />

most often presented by mainstream films. The flip side of<br />

the violent coin of Laura Poitras’s journey into hell (My<br />

Country, My Country), which analyzes Iraq during the first<br />

post-Saddam elections through the eyes of a Sunni doctor, is<br />

the "Kubrick-esque" Ears Open, Eyeballs Click by Canaan<br />

Brumley (a true provocation on the part of the festival!) that<br />

catapults us into the shocking and brutal world of a Marines<br />

training camp. But there is something else within America: for<br />

example, the subcultures represented by the graffiti of Bill<br />

Daniel (Who’s Bozo Texino?) and that of drag racing by<br />

Kevin Jerome Everson (Cinnamon). And the recent past is<br />

also represented through the evocation of the Warhol Factory<br />

experience in Jack Smith & the Destruction of Atlantis by<br />

Mary Jordan, a true treat, as well as Sam Green’s found footage<br />

foray (Lot 63, Grave C) into the famous murder committed by<br />

the Hell’s Angels during a 1969 Rolling Stones concert in<br />

Altamont, California.<br />

Delving even more deeply into Spanish <strong>cinema</strong>, an "investigation"<br />

begun several years ago at Pesaro, we are dedicating a<br />

second retrospective to Catalan director Pere Portabella, who<br />

has already been our guest in the past. From his beginnings as<br />

a producer (Los golfos by Carlos Saura, El cochecito by Marco<br />

Ferreri, Viridiana by Luis Buñuel, and the more recent<br />

Tren de sombras by José Luís Guerin), Portabella later in his<br />

long career became a polysemous director outside the classical<br />

system of narrative feature films. His is an oeuvre that, revisiting<br />

the concept of realism in light of a polyphonic <strong>cinema</strong>,<br />

draws upon and is "contaminated" by various arts: above all,<br />

painting (his four works on Miró), music (Playback, Acció<br />

Santos) and literature (Vampir Cuadecuc), without forgetting<br />

politics (Informe general..., Umbracle) and anti-bourgeois<br />

criticism (Pont de Vorsòvia, his latest film).<br />

As we did last year with Korea, this year we are once again presenting<br />

a diverse program of digital works, this time from<br />

young and not-so-young Filipino filmmakers. In a selection<br />

that includes 15 filmmakers, we would like to point out sever-<br />

42 a <strong>Mostra</strong> Internazionale <strong>del</strong> Nuovo Cinema

ack, Acció Santos), la letteratura (Vampir Cuadecuc), senza<br />

dimenticare la politica (Informe general..., Umbracle) e la critica<br />

antiborghese (Pont de Vorsòvia, il suo film più recente).<br />

Come l’anno scorso con la Corea, anche quest’anno proponiamo<br />

un variegato programma di opere in digitale, proveniente<br />

da giovani e meno giovani leve <strong>del</strong>le Filippine. In<br />

una selezione che comprende circa 15 filmmaker, ci permettiamo<br />

di suggerire alcuni momenti clou: le ultime due<br />

opere de l’enfant terrible Khavn; il torrenziale mockumentary<br />

Ang Anak Ni Brocka di Sigfreid Barros-Sanchez che<br />

affronta in modo originale e “scorretto” la mitica figura di<br />

Lino Brocka mostrandone vizi e virtù; Diliman, inconsueta<br />

riflessione sul rapporto tra arte e politica <strong>del</strong> famoso scrittore,<br />

saggista e regista indipendente Ramon “Mes” de<br />

Guzman; Pepot artista di Clodualdo <strong>del</strong> Mundo Jr che con<br />

tocco disincantato e leggero affronta sogni e miserie <strong>del</strong>la<br />

gioventù filippina; e infine un’ampia selezione dei film<br />

musicali di Roque Federizon Lee, detto Roxlee, oggi riconosciuto<br />

come un’icona <strong>del</strong>l’underground nel suo paese.<br />

Negli “Eventi Speciali” ritornano le ultime prove di alcuni<br />

cineasti che hanno fatto la storia <strong>del</strong> Festival di Pesaro<br />

(Chantal Akerman, Lucian Pintilie, Chris Petit) oltre all’opera<br />

collettiva prodotta dalla viennese Sixpack, Mozart-<br />

Minute, con cui l’avanguardia austriaca e non, rende<br />

omaggio al 250° anniversario <strong>del</strong>la nascita di Mozart. Sempre<br />

in tema di rievocazioni, a un secolo dalla nascita, il<br />

Festival dedica alla figura di Enrico Mattei, un grande<br />

figlio <strong>del</strong>le terre pesaresi, un ricordo con due lavori <strong>del</strong>lo<br />

svizzero Gilbert Bovay prodotti dall’Eni, e una tavola<br />

rotonda sull’attività pionieristica che Mattei stesso ha svolto<br />

nel campo <strong>del</strong> documentario industriale e sociale.<br />

Accanto alle “Nuove Proposte Video”, ci preme sottolineare,<br />

per lo meno, i due omaggi ad Andrea Caccia e Antonello<br />

Matarazzo che rappresentano la continuazione di<br />

un’indagine sui videomaker italiani più giovani ormai in<br />

atto a Pesaro da diversi anni. Il percorso <strong>del</strong>la loro produzione,<br />

ancora in fieri, così come la loro diversità di approccio,<br />

propone considerazioni e problematiche dei linguaggi<br />

<strong>cinema</strong>tografici più tradizionali a confronto con le risorse<br />

<strong>del</strong>le nuove tecnologie digitali. Caccia ci offre un percorso<br />

personale all’interno <strong>del</strong> documentario difforme dall’omologazione<br />

comunicativa imperante negli ultimi anni in<br />

questo genere; mentre Matarazzo procede nel segno <strong>del</strong>la<br />

cifra pittorica, lavorando sull’interazione con la musica e il<br />

morphing <strong>del</strong>le immagini come <strong>del</strong> senso.<br />

A cura di Vito Zagarrio, il 20° Evento Speciale, in collaborazione<br />

con la Fondazione Centro Sperimentale di<br />

Cinematografia-Cineteca Nazionale, è consacrato a una<br />

mappatura degli esordienti <strong>del</strong> <strong>cinema</strong> italiano <strong>del</strong> terzo<br />

millennio. Una <strong>cinema</strong>tografia questa, spesso bistrattata,<br />

ma che grazie a uno sguardo organico d’insieme dimostra<br />

una forza e una vitalità sottovalutate. Insieme ad<br />

autori già consolidati come Paolo Sorrentino, Vincenzo<br />

Marra, Daniele Gaglianone, Genovese e Miniero, Daniele<br />

Vicari, Eros Puglielli, Saverio Costanzo, Alex Infascelli,<br />

la retrospettiva vuole segnalare i lavori di altri cineasti<br />

che, invece, ancora non hanno trovato una loro giusta<br />

dimensione critica.<br />

al key offerings: the last two works by enfant terrible Khavn;<br />

the torrential mockumentary Ang Anak Ni Brocka by<br />

Sigfreid Barros-Sanchez that deals, in an original and "incorrect"<br />

way, with the mythical figure of Lino Brocka, depicting<br />

his vices and virtues; Diliman, an unusual reflection on the<br />

relationship between art and politics of the famous writeressayist-independent<br />

director Ramon "Mes" de Guzman;<br />

Pepot artista by Clodualdo <strong>del</strong> Mundo Jr., which, with a disillusioned<br />

and light touch deals with the dreams and miseries<br />

of Filipino youth; and, lastly, a wide selection of musical films<br />

by Roque Federizon Lee ("Roxlee"), recognized today as an<br />

icon of the Philippine underground.<br />

The Special Events section features the latest works by some of<br />

the filmmakers who have helped shape the history of the Pesaro<br />

Film Festival (Chantal Akerman, Lucian Pintilie, Chris Petit),<br />

as well as a collective work produced by the Vienna-based Sixpack,<br />

Mozart-Minute, which pays homage to the 250th<br />

anniversary of the composer’s birth. We are also commemorating<br />

the 100th year of the birth of Enrico Mattei, the great son<br />

of the Pesaro region, with two films by Swiss director Gilbert<br />

Bovay, produced by ENI, and a round table discussion on Mattei’s<br />

pioneering activities in the field of industrial and social<br />

documentaries.<br />

Along with the Nuove Proposte Video, we are also paying<br />

homage to Andrea Caccia and Antonello Matarazzo, who represent<br />

the continuation of an exploration of young Italian<br />

videomakers that Pesaro has been conducting for several years.<br />

The trajectory of their work, which is still in progress, like the<br />

diversity of their approaches, offers considerations on and problems<br />

with of the most traditional languages in light of the<br />

resources of new digital technologies. Caccia offers us a personal<br />

view of the documentary, different from the reigning<br />

communicative homologation in the genre of recent years,<br />

while Matarazzo works more pictorially, on the interaction<br />

with music and the morphing of images and sense.<br />

Organized by Vito Zagarrio, the 20th Special Event, in collaboration<br />

with the Fondazione Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia-Cineteca<br />

Nazionale, is dedicated to a "map" of the<br />

debut Italian filmmakers of the third millennium. Though often<br />

mistreated, these films as a whole, thanks to an overall organic<br />

vision, demonstrate an underestimated strength and vitality.<br />

Along with already established filmmakers such as Paolo Sorrentino,<br />

Vincenzo Marra, Daniele Gaglianone, Genovese and<br />

Miniero, Daniele Vicari, Eros Puglielli, Saverio Costanzo and<br />

Alex Infascelli, the program will also highlight films by other<br />

directors who have not yet received their due critical acclaim.<br />

Last, but certainly not least, is our competition section, Pesaro<br />

Nuovo Cinema – Premio Lino Miccichè, whose name was<br />

changed last year in honor of the festival’s co-founder, which<br />

features a €5,000 prize for a first or second film that represents<br />

new international tendencies in fiction and non-fiction, to be<br />

chosen this year from among eight different European and<br />

extra-European titles by jury members Paolo Virzì, Jasmine<br />

Trinca and Roberto Silvestri. Furthermore, an Audience<br />

Award will go to the best film presented in the open air screenings<br />

held in Pesaro’s main square – a section that this year is<br />

particularly tied to Italian and Argentinean <strong>cinema</strong>.<br />

42 a <strong>Mostra</strong> Internazionale <strong>del</strong> Nuovo Cinema 11

E per concludere un cenno alla nostra sezione a concorso, il<br />

“Pesaro Nuovo Cinema – Premio Lino Miccichè” istituito<br />

l’anno scorso e dotato di 5.000 Euro, dove si intende dare<br />

conto con opere prime e seconde, provenienti da otto diversi<br />

paesi europei ed extraeuropei, <strong>del</strong>le nuove tendenze internazionali<br />

nel campo <strong>del</strong>la fiction e non. Una giuria composta<br />

da Paolo Virzì, Jasmine Trinca e Roberto Silvestri sceglierà il<br />

vincitore mentre il “Premio <strong>del</strong> pubblico” verrà assegnato al<br />

migliore dei film presentati “open air” nella piazza principale<br />

di Pesaro – un sezione che nella presente edizione si<br />

lega in modo peculiare al <strong>cinema</strong> italiano e argentino.<br />

Che altro ancora aggiungere, se non augurare a tutti i nostri<br />

ospiti e spettatori il rituale augurio di “Buon Festival”.<br />

12<br />

What else can we say except to wish all of our guests and spectators<br />

a wonderful festival?<br />

42 a <strong>Mostra</strong> Internazionale <strong>del</strong> Nuovo Cinema

SELEZIONE UFFICIALE<br />

Concorso Pesaro Nuovo Cinema – Premio Lino Miccichè<br />

Cinema in Piazza<br />

20° Evento Speciale:<br />

La meglio gioventù<br />

Nuovo <strong>cinema</strong> italiano 2000 – 2006<br />

LA GIURIA<br />

Roberto Silvestri è nato a Lecce nel 1950. Ha studiato filosofia a Roma e agli inizi degli anni ’70<br />

ha fondato il cineclub romano “Il Politecnico”. Dal 1978 scrive per “Il manifesto” e dal 1998 è il<br />

direttore responsabile <strong>del</strong> supplemento culturale Alias. Conduce alla radio il progamma<br />

“Hollywood Party”. Ha fatto parte <strong>del</strong>la commissione selezionatrice di Venezia sotto la direzione<br />

di Rondi e Laudadio. Ha lavorato in altri festival <strong>cinema</strong>tografici, tra i quali quelli di Bellaria,<br />

Rimini, Aversa e Lecce. Attualmente dirige il festival di Sulmona.<br />

Roberto Silvestri (Lecce, 1950) studied philosophy in Rome and in the 1970s founded the "Il Politecnico"<br />

film club, also in Rome. Since 1978, he has written for the daily newspaper Il manifesto and, as of<br />

1998, is editor of the paper’s cultural supplement "Alias." He also hosts the radio show "Hollywood Party"<br />

and was on the selection committee of the Venice Film Festival under the artistic direction of Gian<br />

Luigi Rondi and Felice Laudadio. He has worked for other festivals – including Bellaria, Rimini, Aversa<br />

and Lecce – and currently directs the Sulmona Film Festival.<br />

Jasmine Trinca (1981) ha esordito come attrice con Nanni Moretti che la sceglie per interpretare<br />

il ruolo di Irene ne La stanza <strong>del</strong> figlio. Nel 2003 ha fatto parte <strong>del</strong> cast de La meglio<br />

gioventù di Marco Tullio Giordana. Nel 2005 ha lavorato in uno degli episodi di Manuale<br />

d’amore di Giovanni Veronesi, ed è stata diretta da Michele Placido nel film Romanzo Criminale.<br />

Infine, il ritorno con Nanni Moretti ne Il Caimano. Dichiara “di essere iscritta da<br />

tempo immemore all’università, facoltà di Lettere”. Tra i premi che ricorda, ha citato<br />

“attricetta rivelazione Chopard” a Cannes, consegnato da Elton John. Ma questo pare che<br />

Jasmine lo voglia raccontare solo ai nipoti!<br />

Jasmine Trinca (1981) made her acting debut as Irene in Nanni Moretti’s The Son’s Room and in 2003<br />

was part of the ensemble cast of The Best of Youth by Marco Tullio Giordana. In 2005, she appeared in<br />

Giovanni Veronesi’s Manual of Love as well as in Crime Novel by Michele Placido. More recently, she<br />

worked with Moretti again in The Caiman. She claims she has been enrolled in Literature at university<br />

since "forever." Her awards include "Chopard emerging starlet award," given to her by Elton John. This,<br />

however, is something she only seems to want to tell her grandchildren!<br />

Paolo Virzì è nato a Livorno nel 1964 e ha frequentato il Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia<br />

di Roma, dove si è diplomato in sceneggiatura nel 1987. Sceneggiatore e autore di soggetti<br />

tra gli altri per Gabriele Salvatores e Giuliano Montaldo, ha esordito come regista nel 1994 con<br />

La bella vita, selezionato alla <strong>Mostra</strong> <strong>del</strong> <strong>cinema</strong> di Venezia. L’anno seguente realizza Ferie d’agosto<br />

che vince il David di Donatello come miglior film. Nel 1997 è la volta di Ovosodo che ottiene<br />

il Gran Premio Speciale <strong>del</strong>la Giuria a Venezia. Nel 2002 realizza My name is Tanino, e nel 2003<br />

Caterina va in città. Il suo <strong>nuovo</strong> lavoro non ancora uscito in sala è N – Ucciderò il tiranno.<br />

Paolo Virzì (Livorno, 1964) attended the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia in Rome, graduating<br />

in Screenwriting in 1987. Screenwriter for a number of directors, including Gabriele Salvatores<br />

and Giuliano Montaldo, he debuted as a director in 1994 with La bella vita, which was screened at<br />

the Venice Film Festival. The following year, he made Ferie d’agosto, which won the David di<br />

Donatello for Best Film. In 1997, his film Ovosodo won the Grand Jury Prize at Venice. In 2002, he<br />

made My Name is Tanino and in 2003, Caterina in the Big City. His latest film, not yet released<br />

theatrically, is N - Napoléon.<br />

42 a <strong>Mostra</strong> Internazionale <strong>del</strong> Nuovo Cinema 13

La Musicfeel (www.musicfeel.com) fondata dai compositori<br />

Stefano Cretarola & Marco Fe<strong>del</strong>e, offre al vincitore <strong>del</strong><br />

Concorso “Pesaro Nuovo Cinema – Premio Lino Miccichè<br />

2006”, la realizzazione <strong>del</strong>le musiche originali per la sua<br />

prossima opera <strong>cinema</strong>tografica.<br />

MusicFeel è un progetto permanente per la produzione di<br />

musica originale per cortometraggi e lungometraggi. Fondata<br />

dai compositori Stefano Cretarola e Marco Fe<strong>del</strong>e nel<br />

settembre 2003, MusicFeel riunisce esperienza, professionalità<br />

e passione offrendo, oltre alla realizzazione di musiche<br />

originali, anche una preziosa collaborazione artistica<br />

ad autori, registi, produttori, sceneggiatori. Il progetto si<br />

rivolge anche a registi/produttori emergenti (offrendo<br />

loro <strong>del</strong>le condizioni molto favorevoli) che necessitano di<br />

una colonna sonora originale per poter distribuire la loro<br />

opera nei canali televisivi terrestri, satellitari, Internet e<br />

qualsiasi altra forma di diffusione.<br />

Musicfeel lavora normalmente con registi di tutta Europa,<br />

grazie al proprio sito www.musicfeel.com che permette di<br />

ospitare le stesure provvisorie <strong>del</strong>le colonne sonore in corso.<br />

Tramite la rete il regista/produttore può facilmente visionare<br />

le bozze <strong>del</strong> proprio film con le musiche in lavorazione e<br />

comunicare ai compositori, di volta in volta, le proprie<br />

osservazioni e indicazioni. Nel 2005 Musicfeel, con l’obiettivo<br />

di promuovere vigorosamente l’utilizzo di musiche originali,<br />

ha ideato il Premio Musicfeel che sta riscuotendo un<br />

notevole successo in tutta Italia. Il Premio, che viene assegnato<br />

nei migliori festival italiani ai registi vincitori, consiste<br />

nella composizione e realizzazione <strong>del</strong>le musiche originali<br />

per la loro prossima opera <strong>cinema</strong>tografica.<br />

Stefano Cretarola (1970) ha studiato pianoforte e tastiere<br />

perfezionandosi alla Saint Louis College of Music e fino al<br />

1990 ha alternato attività musicali tra cui composizione,<br />

sperimentazione, arrangiamento e l’orchestrazione di brani<br />

di ogni genere musicale. Dopo aver partecipato a numerose<br />

esperienze live e in studio si è dedicato alla composizione<br />

di musica per immagini ed eventi artistici. Ha anche<br />

realizzato numerosi dischi.<br />

Marco Fe<strong>del</strong>e (1965) ha studiato chitarra classica e nel<br />

tempo ha sviluppato una tecnica particolare di arpeggio su<br />

chitarra acustica molto personale e originale. In qualità di<br />

pittore ha unito fin da subito l’arte figurativa con quella<br />

musicale, realizzando opere multimediali sulle sue tele.<br />

Nel 1990 inizia il suo percorso come compositore. Dal<br />

1998, insieme a Stefano Cretarola si dedica pienamente alla<br />

composizione di musica per immagini, realizzando numerose<br />

colonne sonore di spettacoli di danza, teatro e di esposizioni<br />

multimediali.<br />

14<br />

PREMIO MUSICFEEL<br />

Founded by composers Stefano Cretarola and Marco Fe<strong>del</strong>e,<br />

MusicFeel offers the winner of the "Pesaro Nuovo Cinema – Premio<br />

Lino Miccichè 2006" the free composition of an original<br />

soundtrack for his or her next short film.<br />

MusicFeel is an ongoing project for the production of original<br />

soundtracks for short and feature films. Founded by composers<br />

Stefano Cretarola and Marco Fe<strong>del</strong>e in September 2003,<br />

MusicFeel unites experience, professionalism and enthusiasm by<br />

offering composers, directors, producers and screenwriters valuable<br />

artistic collaboration as well the creation of original music.<br />

MusicFeel also offers emerging directors/producers highly favorable<br />

terms for creating an original soundtrack that facilitates the<br />

distribution of their film(s) through free, cable and satellite television,<br />

the Internet and all other media.<br />

Musicfeel regularly works with directors from all over Europe,<br />

thanks to its website (www.musicfeel.com), on which they are<br />

able to post "drafts" of their soundtracks in progress. Through<br />

the site, a director can easily view his/her short film with the<br />

music and communicate their comments and instructions directly<br />

to the composers.<br />

With the aim of promoting the use of original music, in 2005, Cretarola<br />

and Fe<strong>del</strong>e created the Musicfeel Prize, which is meeting<br />

with success throughout Italy. The prize is awarded to the winning<br />

filmmakers of Italy’s top <strong>cinema</strong> festivals and consists of the<br />

composition of an original soundtrack for the director’s next film.<br />

Stefano Cretarola (1970) studied the piano and synthesizers,<br />

taking a master class at Saint Louis College of Music in Rome<br />

and, until 1990, divided his time between composing, experimentation,<br />

musical arrangement and orchestration of music of<br />

all genres. After having performed in numerous live and in studio<br />

sessions, he began dedicated himself entirely to the composition<br />

of music for images and artistic events. He has also put out<br />

a number of discs.<br />

Marco Fe<strong>del</strong>e (1965) studied classical guitar and over time<br />

developed a unique, highly personal and original arpeggio style.<br />

Being a painter, from the very beginning he combined the figurative<br />

and musical arts to creating multimedia works on canvas<br />

as well. He began composing in 1990 and since 1998, together<br />

with Stefano Cretarola, has dedicated himself fully to the composition<br />

of music for images, creating numerous soundtracks for<br />

dance and theatre performances as well as multimedia exhibits.<br />

42 a <strong>Mostra</strong> Internazionale <strong>del</strong> Nuovo Cinema

PIAZZA<br />

Alexey Balabanov<br />

ZHMURKI<br />

Dead Man’s Bluff<br />

(t.l.: Roulette russa)<br />

Due giovani criminali mettono le mani su una valigia piena<br />

di eroina appartenente a un affermato e rispettato gangster<br />

locale. I giovani neofiti provano a imbrogliarlo non<br />

afferrando <strong>del</strong> tutto quanto l’uomo sia realmente violento.<br />

“Un gruppo di attori popolari ha realizzato un ritratto collettivo<br />

<strong>del</strong>la mafia russa degli anni ’90 con comportamenti<br />

da macho, giacche color lampone, capelli rasati e al collo<br />

catene d’oro grosse come un dito e inclinazione a spararsi<br />

l’un l’altro con sprezzante noncuranza”.<br />

Alexey Balabanov<br />

Biografia<br />

Regista, sceneggiatore e produttore, Alexey Balabanov è<br />

nato a Sverdlovsk nel 1959. Ha studiato lingue straniere a<br />

Gorky e <strong>cinema</strong> a Mosca. Si è trasferito a San Pietroburgo<br />

dove ha diretto il suo primo lungometraggio di finzione.<br />

sceneggiatura/screenplay: Stas Mokhnachev, Alexey Balabanov<br />

fotografia/<strong>cinema</strong>tography: Evgeny Privin<br />

montaggio/editing: Tatyana Kuzmicheva<br />

suono/sound: Mikhail Nikolaev<br />

musica/music: Vyacheslav Butusov<br />

interpreti/cast: Alexey Panin, Dmitry Dyuzhev, Nikita Mikhalkov,<br />

Sergey Makovetsky, Viktor Sukhorukov, Dmitry Pevtsov<br />

Two young mobsters get hold of a case full of heroin belonging to<br />

a local well-established and respected gangster. The young neophytes<br />

try to cheat him, not quite understanding how tough a<br />

man he really is.<br />

“A first-rate ensemble of popular Russian actors creates a collective<br />

portrait of the Russian Mafia of the 1990s, with their macho<br />

attitudes, raspberry jackets, short haircuts, finger-thick gold<br />

chains and penchant for shooting one another with reckless<br />

abandon.”<br />

Alexey Balabanov<br />

Biography<br />

Director/scriptwriter/producer Alexey Balabanov (Sverdlovsk,<br />

1959) graduated in Foreign Languages from the University<br />

Gorky and in Directing in Moscow. He later moved to St.<br />

Petersburg, where he directed his first feature film.<br />

formato/format: colore<br />

produttore/producer: Sergey Selyanov<br />

produzione/production: Ctb Film Company<br />

distribuzione/distribution: Inter<strong>cinema</strong> XXI Century<br />

contatto/contacts: post@intercin.ru, festival@intercin.ru<br />

durata/running time: 107’<br />

origine/country: Russia 2005<br />

Filmografia/Filmography<br />

Happy Days (1991), The Castle (1994), Trofim (1995, cm), Brother (1997), Of Freaks and Men (1998), Brother 2 (2000), The War<br />

(2002), River (2002), Dead Man’s Bluff (2005)<br />

42 a <strong>Mostra</strong> Internazionale <strong>del</strong> Nuovo Cinema 15

PIAZZA - IL CINEMA ARGENTINO CONTEMPORANEO<br />

Daniel Burman<br />

DERECHO DE FAMILIA<br />

Family Law<br />

(t.l.: Diritto di famiglia)<br />

Ariel Perelman come suo padre è diventato avvocato<br />

anche se non troppo convinto né <strong>del</strong>la professione intrapresa,<br />

né <strong>del</strong> fatto di lavorare con il genitore. Il padre di<br />

Ariel da quando è rimasto vedovo si è dedicato totalmente<br />

al lavoro e si è adattato a ogni situazione difendendo<br />

chiunque. Ariel, per parte sua, è costretto a vivere con i<br />

suoi fantasmi, lavora per il dipartimento di giustizia come<br />

avvocato d’ufficio, e ha una vita grigia. Si emanciperà o<br />

vivrà all’ombra <strong>del</strong> vecchio padre?<br />

“La paternità per me è un tema affascinante che ho usato<br />

come struttura portante <strong>del</strong> film. Quando i nostri figli<br />

nascono, la prima cosa che fanno è cercare la madre per<br />

ricevere il nutrimento, sanno istintivamente dove andare e<br />

cosa fare. Noi padri ci sediamo e aspettiamo che qualcosa<br />

accada, attendiamo che la paternità emerga, in quel<br />

momento siamo presenti per un bambino allo stesso modo<br />

di una nurse o di un tassista. Così ho scoperto che la relazione<br />

deve essere costruita e, in un certo senso, dobbiamo<br />

convincere i figli che noi siamo i padri, è come creare una<br />

fiction, inventare un linguaggio”.<br />

Daniel Burman<br />

Biografia<br />

Daniel Burman (1973) è regista, sceneggiatore e produttore.<br />

Inizia studiando giurisprudenza, ma poi cambia idea e<br />

decide di dedicarsi al <strong>cinema</strong>. Tra il 1992 e il 1995 realizza<br />

alcuni cortometraggi. Nel 1996 dirige la sua opera prima,<br />

Un crisantemo estalla en cinco esquinas. Esperando al Mesías<br />

(2000) il primo film di una trilogia autobiografica – che<br />

comprende anche El abrazo partido e Derecho de familia –<br />

incentrata sulle problematiche di un giovane ebreo a Buenos<br />

Aires (Ariel, interpretato in tutti e tre i film dall’attore<br />

Daniel Hendler). Insieme a Diego Dubcovsky, nel 1995 ha<br />

fondato la casa di produzione BD Cine.<br />

sceneggiatura/screenplay: Daniel Burman<br />

fotografia/<strong>cinema</strong>tography: Ramiro Civita<br />

montaggio/editing: Alejandro Parysow<br />

suono/sound: Federico Billordo<br />

scenografia/art direction: María Eugenia Suerio<br />

costumi/costumes: Roberta Pesci<br />

interpreti/cast: Daniel Hendler, Arturo Goetz, Eloy Burman,<br />

Julieta Díaz<br />

16<br />

Ariel Perelman is a lawyer, like his widower father, although not<br />

as convinced about his career. While his father represents a variety<br />

of colorful petty criminals and cuts a lively figure, Ariel deals, literally,<br />

with ghosts. He works for the justice department representing<br />

clients in absentia. His life is bearable but rather grey.Will<br />

he become his own man, or remain a shadow of the old man?<br />

“To me, fatherhood is a fascinating theme, which I used as the<br />

foundation of the film. When our children are born, the first<br />

thing they do is seek out their mother for nourishment. They<br />

instinctively know where to go and what to do. We fathers sit<br />

and wait for something to happen, we wait for fatherhood to<br />

emerge. In that moment, we are there for a child in much the<br />

same way as a nurse or taxi driver. This is how I discovered that<br />

the relationship has to be constructed and, in a sense, we have to<br />

convince our children that we are the fathers. It’s like creating a<br />

piece of fiction, or inventing a language.”<br />

Daniel Burman<br />

Biography<br />

Daniel Burman (1973) is a director, screenwriter and producer.<br />

He began studying law, then changed his mind and decided to<br />

study <strong>cinema</strong>. From 1992-5, he made a number of short films. In<br />

1996, he made his debut feature, Un crisantemo estalla en cinco<br />

esquinas. In 2000, he made Esperando al Mesías, the first<br />

film of an autobiographical trilogy, which includes El abrazo<br />

partido and Derecho de familia, on the problems of a young<br />

Jewish man (Ariel, played in all three films by actor Daniel<br />

Hendler) living in Buenos Aires. In 1995, together with Diego<br />

Dubcovsky, he founded the BD Cine production company.<br />

formato/format: colore<br />

produttore/producer: Diego Dubcovsky<br />

produzione/production: BDCINE, Classic, Paradis Films, Wanda<br />

Vision<br />

distribuzione/distribution: Celluloid Dreams<br />

contatto/contacts: info@celluloid-dreams.com<br />

durata/running time: 102’<br />

origine/country: Argentina, Spagna 2006<br />

Filmografia/Filmography<br />

En qué estación estamos? (1992, cm), Post data de ambas cartas (1993, cm), Help o el pedido de auxilio de una mujer viva (1994,<br />

cm), Niños envueltos (1995, cm), Un crisantemo estalla en cinco esquinas (1996), Esperando al Mesías (2000), Todas las azafatas<br />

van al cielo (2001), Un cuento de navidad (2003), El abrazo partido (2003), 18-J (2004, cm), Derecho de familia (2005)<br />

42 a <strong>Mostra</strong> Internazionale <strong>del</strong> Nuovo Cinema

PNC<br />

Fujiwara Toshi<br />

BOKURA WA MO KAERENAI<br />

We Can’t Go Home Again<br />

(t.l.: Non possiamo più<br />

tornare a casa)<br />

All’inizio <strong>del</strong> <strong>nuovo</strong> secolo a Tokyo, cinque giovani vagano<br />

per la città tra università, case editrici, parchi e club<br />

sadomaso, inseguendo il senso <strong>del</strong>la propria esistenza o<br />

forse inseguiti dalla loro stessa vita: l’insicura Mao, il cinefilo<br />

Yushin, la “regina” sadomaso Kurumi, il taciturno<br />

Masato e infine Atsushi il cui unico impegno è quello di<br />

scattare foto <strong>del</strong> proprio volto in ogni luogo visitato.<br />

“L’idea di un’improvvisazione collettiva proviene dal<br />

<strong>cinema</strong> americano indipendente anni ‘60 e ‘70, in particolare<br />

per quanto mi riguarda da Robert Kramer e dai<br />

Newsreel. (...) Io non avevo il controllo diretto su quello<br />

che le persone avrebbero detto o fatto, questo spettava<br />

agli attori. Il mio primo compito come regista è di avere<br />

la mente aperta per osservare attentamente e per trovare<br />

ciò che è realmente interessante, e di pensare al modo<br />

migliore per trasformare tutto in immagini”.<br />

Fujiwara Toshi<br />

Biografia<br />

Toshi Fujiwara è nato a Yokohama nel 1970. È cresciuto tra<br />

Tokyo e Parigi, ha studiato <strong>cinema</strong> presso la Waseda University<br />

School of Literature di Tokyo e la University of<br />

Southern California School of Cinema-TV. Dopo aver lavorato<br />

come critico è passato alla regia. Ha lavorato come<br />

assistente per il regista Yoshida Kiju e ha collaborato a un<br />

progetto incompiuto di Robert Kramer. We Can’t Go Home<br />

Again è il suo lungometraggio d’esordio.<br />

sceneggiatura/screenplay: improvisazione su un’idea di<br />

(improvised from ideas by) Yamada Tetsuya, Torii Mao,<br />

Yamauchi Kazuhiro, Shimoda Atsushi, Takasawa Kurumi,<br />

Kato Aya, Kuroda Yufuko<br />

fotografia/<strong>cinema</strong>tography: Fujiwara Toshi<br />

montaggio/editing: Fujiwara Toshi<br />

suono/sound: Kubota Yukio<br />

scenografia/art direction: Ito Katsunori, Oshima Kanji<br />

interpreti/cast: Torii Mao, Shimoda Atsushi, Takasawa Kurumi,<br />

Katori Yushin, Yamada Tetsuya, Ito Katsunori, Fujiwara<br />

At the dawn of the new century, five young people wander<br />

through Tokyo, among university, publishing companies, parks<br />

and S&M clubs, chasing after a sense of their own existence or<br />

perhaps chased by it: the insecure Mao, film buff Yushin, S&M<br />

“queen” Kurumi, the taciturn Masato and Atsushi, who takes<br />

pictures of his face in every place he visits.<br />

“The idea of collective improvisation comes from the American<br />

independents of the 60s and 70s, in my case especially from<br />

Robert Kramer and Newsreel. (...) I had no direct control over<br />

what each person would say or do; it was up to the actors. My<br />

first job as the director-<strong>cinema</strong>tographer is to be open-minded, to<br />

observe carefully and find what is really interesting, and figure<br />

out how I can best record that as an image.”<br />

Fujiwara Toshi<br />

Biography<br />

Toshi Fujiwara was born on 1970 in Yokohama. He grew up in<br />

Tokyo and Paris and studied <strong>cinema</strong> at the Waseda University<br />

School of Literature in Tokyo and at the University of Southern<br />

California School of Cinema-TV. After working as a film critic,<br />

he moved into filmmaking. He worked as assistant to Yoshida<br />

Kiju and collaborated on an unfinished Robert Kramer project.<br />

We Can’t Go Home Again is his feature debut film.<br />

Tamaki, Yamauchi Kazuhiro, Dougase Masato, Komuro<br />

Kayo, Anna, Nakamura Akemi, Fujiwara Toshi<br />

formato/format: dv, colore<br />

produttore/producer: Fujiwara Toshi, Kan Hirofumi, Hirato<br />

Jun-ya, Alexander Wadouh<br />

produzione/production: Compass Films<br />

distribuzione/distribution: Compass Films<br />

contatto/contacts: conductor71@mac.com<br />

durata/running time: 111’<br />

origine/country: Giappone 2006<br />

Filmografia/Filmography<br />

Independence: Around the film Kedma, a film by Amos Gitai (2002, doc), Shalom – A Weekend in Tel Aviv (cm, 2002), Lights of<br />

Sainte Philomène (cm, 2002), Tsuchimoto Noriaki: A Voyage to New York (doc, mm, 2003), Walk (cm, 2003), Speech or how 9/11<br />

changedmy nation and helped me to turn US against the world (cm, 2003), Fragments: On Amos Gitai & Alila (doc, mm, 2004.),<br />

Hara Kazuo: A Life Marching On (doc, mm, 2004), We Can’t Go Home Again (2006), Tsuchimoto Noriaki: Cinema is the Work of<br />

the Living (doc, 2006)<br />

42 a <strong>Mostra</strong> Internazionale <strong>del</strong> Nuovo Cinema 17

PNC<br />

Valeska Grisebach<br />

SEHNSUCHT<br />

Longing<br />

Desiderio<br />

Un uomo e una donna vivono in un paese vicino Berlino.<br />

Si amano da quando erano piccoli. Markus è un metalmeccanico<br />

e fa parte <strong>del</strong>la squadra dei vigili <strong>del</strong> fuoco locale,<br />

Ella lavora come domestica un paio di ore alla settimana<br />

e canta nel coro <strong>del</strong> paese. Le persone li guardano con<br />

un misto di stupore e sospetto: sembrano così felici, così<br />

innocenti. Dopo una notte di bevute, divertimenti e balli,<br />

Markus si sveglia la mattina seguente nell’appartamento<br />

di una cameriera, Rose. Markus non è in grado di ricordare<br />

cos’è accaduto. Quando cerca di scoprire, è l’inizio di un<br />

amore differente, al quale non è abituato.<br />

“Sono sempre stata interessata alla quantità di vite che esistono<br />

solo nella nostra immaginazione: se fossi stata in un<br />

altro posto, o avessi incontrato un’altra persona, preso una<br />

decisione diversa, o fossi stata più audace... Per me ‘l’anelito’<br />

è un sentimento personale: una forza violenta che può<br />

dire molto di una persona, ma che può contenere anche la<br />

punta agrodolce <strong>del</strong>l’addio, di qualcosa che abbiamo<br />

lasciato alle nostre spalle. Qualche volta un’unica vita non<br />

è abbastanza”.<br />

Valeska Grisebach<br />

Biografia<br />

Valeska Grisebach è nata a Brema nel 1968. Ha studiato<br />

filosofia e letteratura tedesca a Berlino, Monaco e Vienna.<br />

Dal 1993 al 2001 ha frequentato l’Accademia <strong>del</strong> Cinema di<br />

Vienna e ha avuto come insegnanti Peter Patzak, Wolfgang<br />

Glück e Michael Haneke. Ha lavorato per la televisione,<br />

realizzato documentari e nel 2001 con Mein Stern ha esordito<br />

alla regia di una fiction.<br />

sceneggiatura/screenplay: Valeska Grisebach<br />

fotografia/<strong>cinema</strong>tography: Bernhard Keller<br />

montaggio/editing: Bettina Böhler, Valeska Grisebach, Natali<br />

Barrey<br />

suono/sound: Raimund von Scheibner, Oliver Göbel<br />

musica/music: Martin Hossbach<br />

scenografia/art direction: Beatrice Schultz<br />

costumi/costumes: Birte Meesmann<br />

interpreti/cast: Andreas Müller, Ilka Welz, Anett Dornbusch,<br />

Erika Lemke, Markus Werner, Doritha Richter, Detlef Baumann,<br />

Ilse Lausch, Harald Kuchenbecker, Mario Bartel,<br />

Gerald Bliss, Anika Dielitssch, Alexander Dornbusch, Daniel<br />

18<br />

A man and a woman live in a village near Berlin. They’ve loved<br />

each other since they were children. Markus is a metalworker<br />

and a member of the local fire brigade. Ella works a couple of<br />

hours a week cleaning houses and sings in the local choir. People<br />

view them with a mixture of astonishment and suspicion: they<br />

seem so happy, so innocent. After a night of drinking, laughing<br />

and dancing, Markus wakes up in the apartment of a waitress,<br />

Rose, and cannot recall much of what happened. When he tries<br />

to find out, it is the beginning of a different kind of love, to which<br />

he is unaccustomed.<br />

“I've always been moved by the number of other lives that exist<br />

only in one's imagination. If one were somewhere else, or had<br />

met another person, made a different decision, or were daring<br />

enough... For me ‘longing’ is a very personal feeling: a wild power<br />

that can say a lot about a person, but that can also contain a<br />

bittersweet hint of farewell, of something forsaken. Sometimes<br />

this one life is not enough.”<br />

Valeska Grisebach<br />

Biography<br />

Valeska Grisebach was born in Brema in 1968. She studied philosophy<br />

and German literature in Berlin, Munich and Vienna.<br />

From 1993-2001, she studied at the Vienna Film Academy with,<br />

among other teachers, Peter Patzak, Wolfgang Glück and Michael<br />

Haneke. She has worked in television, made documentaries and in<br />

2001 debuted as a feature filmmaker with Mein Stern.<br />

Erdmann, Yves Gall, Jan Günzel, Viola Hoffmann, Nancy<br />

Kraul, Paul Kunze, Petra Lemke, Bernd Liske, Petra Müller,<br />

Hartmut Schliephacke, Sarah Schmidt, Frank Schwarz, Mary<br />

Ann Vohs, Bernd Wachsmuth, Christa Wachsmuth, Karin<br />

Wachsmuth, Patrick Weiss, Isabell Winsel<br />

formato/format: colore<br />

produttore/producer: Peter Rommel<br />

produzione/production: Peter Rommel Productions<br />

distribuzione/distribution: Lucky Red<br />

contatto/contacts: p.rommel@t-online.de, luckyred@mclink.it<br />

durata/running time: 88’<br />

origine/country: Germania 2006<br />

Filmografia/Filmography<br />

Spechen und Nichtsprechen (1995, doc), In der Wüste Gobi (1997, doc), Berlino (1999, doc), Mein Stern (2001), Sehnsucht (2006)<br />

42 a <strong>Mostra</strong> Internazionale <strong>del</strong> Nuovo Cinema

PIAZZA<br />

Michael Hofmann<br />

EDEN<br />

Gregor, uno chef decisamente sovrappeso, manda avanti un<br />

piccolo ristorante nella periferia di una città. Nel tempo libero<br />

si reca in un bar dove viene servito da Eden, una donna<br />

sposata che ha una sorella con la sindrome di Down. Un<br />

giorno Gregor, molto affezionato alla sorella di Eden, decide<br />

di preparare un dolce al cioccolato. Eden impazzisce letteralmente<br />

per quella cioccolata. A quel punto le cose tra i<br />

due cambieranno. Film sull’amore e l’arte <strong>del</strong> cucinare.<br />

“Il progetto è nato dal desiderio di scrivere una storia su<br />

un cuoco grosso e grasso. Un giorno, mi sono state servite<br />

dieci portate cucinate da un cuoco favoloso e completamente<br />

pazzo, Frank Oehler. È arrivato alla mia tavola e ha<br />

detto sorridendo: è meglio <strong>del</strong> sesso, no? Io e il mio amico<br />

abbiamo annuito senza voce e in quel momento mi sono<br />

reso conto che un buon pranzo può cambiare la vita (come<br />

ogni opera d’arte)”.<br />

Intervista con Bénédicte Prot su www.cineuropa.org<br />

Biografia<br />

Michael Hofmann, regista-sceneggiatore tedesco è nato nel<br />

1961, ha scritto molto e soggiornato a lungo in Italia, Gran<br />

Bretagna, Senegal e in Francia (come studente <strong>del</strong>la Femis)<br />

e ha diretto molti cortometraggi prima di realizzare il suo<br />

lungometraggio d’esordio, Trouville Beach (1998). Con il<br />

suo secondo film, Sophiiiie! (2002), in concorso a Locarno,<br />

ha ricevuto un premio promozionale al festival di Monaco.<br />

Eden è il suo terzo film.<br />

sceneggiatura/screenplay: Michael Hofmann<br />

fotografia/<strong>cinema</strong>tography: Jutta Pohlmann<br />

montaggio/editing: Bernhard Wießner, Isabel Meier<br />

suono/sound: Rudi Guyer<br />