Alice in Wonderland - Bruno Osimo, traduzioni, semiotica della ...

Alice in Wonderland - Bruno Osimo, traduzioni, semiotica della ... Alice in Wonderland - Bruno Osimo, traduzioni, semiotica della ...

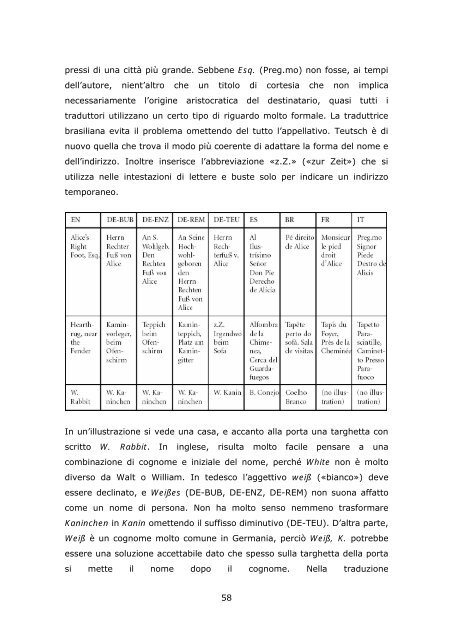

pressi di una città più grande. Sebbene Esq. (Preg.mo) non fosse, ai tempi dell’autore, nient’altro che un titolo di cortesia che non implica necessariamente l’origine aristocratica del destinatario, quasi tutti i traduttori utilizzano un certo tipo di riguardo molto formale. La traduttrice brasiliana evita il problema omettendo del tutto l’appellativo. Teutsch è di nuovo quella che trova il modo più coerente di adattare la forma del nome e dell’indirizzo. Inoltre inserisce l’abbreviazione «z.Z.» («zur Zeit») che si utilizza nelle intestazioni di lettere e buste solo per indicare un indirizzo temporaneo. In un’illustrazione si vede una casa, e accanto alla porta una targhetta con scritto W. Rabbit. In inglese, risulta molto facile pensare a una combinazione di cognome e iniziale del nome, perché White non è molto diverso da Walt o William. In tedesco l’aggettivo weiß («bianco») deve essere declinato, e Weißes (DE-BUB, DE-ENZ, DE-REM) non suona affatto come un nome di persona. Non ha molto senso nemmeno trasformare Kaninchen in Kanin omettendo il suffisso diminutivo (DE-TEU). D’altra parte, Weiß è un cognome molto comune in Germania, perciò Weiß, K. potrebbe essere una soluzione accettabile dato che spesso sulla targhetta della porta si mette il nome dopo il cognome. Nella traduzione 58

translation, B. Conejo is not coherent with Conejo Blanco. Spaniards use two surnames, the father’s name and the mother’s name, so the whole expression Conejo Blanco would be a perfect surname, perhaps together with any initial for a first name, e.g., F. Conejo Blanco. This is the solution the Brazilian translator has chosen, and she is lucky because Coelho Branco is, indeed, a usual surname. 4.3. Names referring to fictitious characters It is a specific characteristic of Alice in Wonderland that, with very few exceptions (like Alice, Pat, Bill), the fictitious characters have no names in the conventional sense of the word. Characters, mostly animals or fantasy creatures, are usually introduced by a description which is afterwards used as a proper name just by writing it with a capital letter. For example, at the end of chapter IV we read: “She stretched herself up on tiptoe, and peeped over the edge of the mushroom, and her eyes immediately met those of a large blue caterpillar, that was sitting on the top with its arms folded, quietly smoking a long hookah, and taking not the smallest notice of her or of anything else.” The next chapter begins as follows: “The Caterpillar and Alice looked at each other for some time in silence…” (emphasis C.N.). White Rabbit is one of the numerous generic nouns turned into a proper name: The White Rabbit, the Mouse, the Duchess, the Gryphon. Translating into Romance languages it is easy just to follow the author’s model capitalizing the generic nouns. In German, however, all nouns are written with a capital first letter, therefore, capitalization cannot be used as a means to mark them as proper names. The only way out of the dilemma would have been to use the nouns without the definite article, but this procedure cannot be found in the German translations of our corpus. Apart from this group of names we find personifications of playing cards: Five, Two or Three, together with the King, the Queen and the Knaves. There are no translation problems here, and the illustrations support the text, especially for readers in cultures where other kinds of playing cards are used. 59

- Page 7 and 8: 1. Prefazione: i giochi di parole i

- Page 9 and 10: istante ad accorgersi, grazie al co

- Page 11 and 12: dice che essi ne sono ornati. Poi,

- Page 13 and 14: come per gli omonimi e gli omografi

- Page 15 and 16: che lo scambio di suoni porti a pro

- Page 17 and 18: see, as she couldn’t answer eithe

- Page 19 and 20: le trasformazioni che ha subìto da

- Page 21 and 22: parti di testo, costringendo il tra

- Page 23 and 24: Riferimenti bibliografici CAMMARATA

- Page 25 and 26: Proper Names in Translations for Ch

- Page 27 and 28: Elisabeth II., es. la reina Isabel

- Page 29 and 30: In the real world, proper names may

- Page 31 and 32: understand the name as a descriptio

- Page 33 and 34: 3. Some Translation Problems Connec

- Page 35 and 36: whereas Hugo may be identified as a

- Page 37 and 38: 4. The translation of proper names

- Page 39 and 40: William the Conqueror). These names

- Page 41 and 42: surprising that the name of the pro

- Page 43 and 44: eaders cannot be expected anyway to

- Page 45 and 46: The reference to Shakespeare is ada

- Page 47 and 48: use a political term probably incom

- Page 49 and 50: Charlotte (“L.C.”!), Tillie for

- Page 51 and 52: cause any inconveniences either. In

- Page 53 and 54: kind of cheese (DE-BUB, DE-ENZ, FR)

- Page 55 and 56: Bill is a lizard. His name is used

- Page 57: name of a little village in the nei

- Page 61 and 62: The last proper name I would like t

- Page 63 and 64: children, they have been published

- Page 65 and 66: Neutralizations (neutr) are cases w

- Page 67 and 68: The last aspect I would like to men

- Page 69 and 70: References Carroll, L. (1946): Alic

- Page 71 and 72: Note [1] I will be using the ISO ab

pressi di una città più grande. Sebbene Esq. (Preg.mo) non fosse, ai tempi<br />

dell’autore, nient’altro che un titolo di cortesia che non implica<br />

necessariamente l’orig<strong>in</strong>e aristocratica del dest<strong>in</strong>atario, quasi tutti i<br />

traduttori utilizzano un certo tipo di riguardo molto formale. La traduttrice<br />

brasiliana evita il problema omettendo del tutto l’appellativo. Teutsch è di<br />

nuovo quella che trova il modo più coerente di adattare la forma del nome e<br />

dell’<strong>in</strong>dirizzo. Inoltre <strong>in</strong>serisce l’abbreviazione «z.Z.» («zur Zeit») che si<br />

utilizza nelle <strong>in</strong>testazioni di lettere e buste solo per <strong>in</strong>dicare un <strong>in</strong>dirizzo<br />

temporaneo.<br />

In un’illustrazione si vede una casa, e accanto alla porta una targhetta con<br />

scritto W. Rabbit. In <strong>in</strong>glese, risulta molto facile pensare a una<br />

comb<strong>in</strong>azione di cognome e <strong>in</strong>iziale del nome, perché White non è molto<br />

diverso da Walt o William. In tedesco l’aggettivo weiß («bianco») deve<br />

essere decl<strong>in</strong>ato, e Weißes (DE-BUB, DE-ENZ, DE-REM) non suona affatto<br />

come un nome di persona. Non ha molto senso nemmeno trasformare<br />

Kan<strong>in</strong>chen <strong>in</strong> Kan<strong>in</strong> omettendo il suffisso dim<strong>in</strong>utivo (DE-TEU). D’altra parte,<br />

Weiß è un cognome molto comune <strong>in</strong> Germania, perciò Weiß, K. potrebbe<br />

essere una soluzione accettabile dato che spesso sulla targhetta <strong>della</strong> porta<br />

si mette il nome dopo il cognome. Nella traduzione<br />

58