to download - International Classical Artists

to download - International Classical Artists

to download - International Classical Artists

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

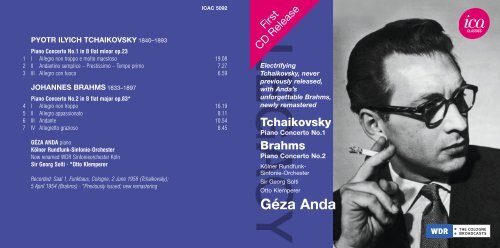

ICAC 5092<br />

PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY 1840–1893<br />

Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.1 in B flat minor op.23<br />

1 I Allegro non troppo e mol<strong>to</strong> maes<strong>to</strong>so 19.08<br />

2 II Andantino semplice – Prestissimo – Tempo primo 7.27<br />

3 III Allegro con fuoco 6.59<br />

JOHANNES BRAHMS 1833–1897<br />

Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.2 in B flat major op.83*<br />

4 I Allegro non troppo 16.19<br />

5 II Allegro appassiona<strong>to</strong> 8.11<br />

6 III Andante 10.54<br />

7 IV Allegret<strong>to</strong> grazioso 8.45<br />

GÉZA ANDA piano<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester<br />

Now renamed WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln<br />

Sir Georg Solti · *Ot<strong>to</strong> Klemperer<br />

Recorded: Saal 1, Funkhaus, Cologne, 2 June 1958 (Tchaikovsky);<br />

5 April 1954 (Brahms) · *Previously issued; new remastering<br />

First<br />

CD Release<br />

Electrifying<br />

Tchaikovsky, never<br />

previously released,<br />

with Anda’s<br />

unforgettable Brahms,<br />

newly remastered<br />

Tchaikovsky<br />

Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.1<br />

Brahms<br />

Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.2<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-<br />

Sinfonie-Orchester<br />

Sir Georg Solti<br />

Ot<strong>to</strong> Klemperer<br />

Géza Anda

GÉZA ANDA PLAYS TCHAIKOVSKY<br />

AND BRAHMS<br />

Today, perhaps more than ever, we look for musicians<br />

whose individuality sets them apart. This is not the<br />

same thing as a determinedly ‘different’ or idiosyncratic<br />

approach that places the artist above the composer, but<br />

is rather a subtle balance between crea<strong>to</strong>r and recrea<strong>to</strong>r.<br />

And in this sense Géza Anda (1921–1976), whose early<br />

death robbed the world of a rare voice and presence, was<br />

invariably true <strong>to</strong> both the letter and spirit of the score<br />

and yet always added a personal <strong>to</strong>uch.<br />

Among Anda’s first significant triumphs was his<br />

1953 recording of the Brahms Paganini Variations. His<br />

performance – arguably the most striking and original of<br />

all – alerted the public <strong>to</strong> his immaculate dexterity, magical<br />

<strong>to</strong>nal sheen and allure, and musical wit and subtlety. In<br />

1957 Anda played the three Bartók Piano Concer<strong>to</strong>s in a<br />

single concert (a musical, not <strong>to</strong> mention athletic, feat) and<br />

<strong>to</strong>wards the end of his all <strong>to</strong>o brief life he <strong>to</strong>ok up the very<br />

different challenge of the complete Mozart Piano Concer<strong>to</strong>s<br />

both in the concert hall and on record. At the same time he<br />

reflected a little ruefully that he no longer possessed the<br />

necessary empathy for virtuoso confections such as the<br />

Delibes/Dohnányi Valse lente (Coppélia, Act 1).<br />

Described by Furtwängler as ‘a troubadour of the<br />

piano’, Anda placed the greatest importance on the vocal<br />

inspiration behind so much keyboard music (he went on<br />

<strong>to</strong> record with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf). Unduly percussive<br />

students got short shrift in his masterclasses, and it is<br />

hardly surprising that pianists such as Alfred Cor<strong>to</strong>t and<br />

Edwin Fischer were among his most admired artists.<br />

Yet as Anda shows in these performances of<br />

Tchaikovsky’s Concer<strong>to</strong> No.1 (previously unpublished)<br />

and Brahms’s Concer<strong>to</strong> No.2, he could be dazzlingly<br />

2<br />

intemperate or volatile with sudden turns of speed and a<br />

brilliance that made one critic find him ‘as explosive as<br />

Mr Vichinsky – a Russian politician – at a conference’.<br />

In the first movement of the Tchaikovsky, as Anda strides<br />

purposely but never inflexibly forward, you don’t have <strong>to</strong><br />

go far <strong>to</strong> encounter those sudden crescendi; a <strong>to</strong>uch of<br />

Hungarian paprika, if you like. The reflexes are rapid, nervy<br />

and unpredictable, a far cry from received Russian wisdom,<br />

and if Anda is sensitive <strong>to</strong> the second subject’s assuaging<br />

lyricism he always tempers such relaxation with spinetingling<br />

bravura elsewhere. As the novelist D.H. Lawrence<br />

once put it, ‘the sesame seed gives the nougat its bite,<br />

otherwise it would be sickly sweet’. The Andantino is<br />

another case in point: Anda’s poetic delicacy in the outer<br />

sections is balanced by a will-o-the-wisp chase through<br />

the central Prestissimo that is sufficiently fleet <strong>to</strong> make<br />

you look ahead <strong>to</strong> the not unrelated sense of fantasy in the<br />

flickering Pres<strong>to</strong> at the heart of the Adagio from Bartók’s<br />

Second Piano Concer<strong>to</strong>. From Anda, such pages became<br />

a true ‘scherzo of fireflies’.<br />

Again, this time away from the ‘greatest of all battles<br />

for piano and orchestra’ and in the more closely integrated<br />

writing of Brahms’s Second Piano Concer<strong>to</strong>, Anda’s artistry<br />

is paramount. For many listeners the greatest of all piano<br />

concer<strong>to</strong>s, Brahms’s Second makes <strong>to</strong>wering claims on<br />

the pianist’s stamina. Brahms reputedly composed the<br />

work after a lady pianist had given a less than satisfying<br />

performance of his First Concer<strong>to</strong>; he stated that he would<br />

write a concer<strong>to</strong> that no woman could play (a throwing<br />

down of the gauntlet in more feminist times, and an<br />

incentive taken up by great pianists such as Myra Hess,<br />

Clara Haskil, Alicia de Larrocha (reluctantly) and Annie<br />

Fischer, <strong>to</strong> name but four). This concer<strong>to</strong> was central<br />

<strong>to</strong> Anda’s reper<strong>to</strong>ire, and he more than meets its every<br />

daunting demand. With playing that is both deft and<br />

magisterial, he positively relishes the challenge and<br />

never more so than in that moment in the opening Allegro<br />

where, as Sir Donald Tovey says, ‘the air seems full of<br />

whisperings and the beating of mighty wings’. His way<br />

<strong>to</strong>o, with that ‘great and child-like finale’ (Tovey again)<br />

is brilliantly alive, a ‘glory of tumbling gaiety’ ending in<br />

a dazzling ‘un poco più mosso’ finish.<br />

Here then, partnered by Solti in the Tchaikovsky and<br />

Klemperer in the Brahms, is further evidence of Anda’s<br />

genius. And if this rekindles a legend for some, it will also<br />

introduce others <strong>to</strong> a musician of a verve and style that<br />

place him high in the pianistic pantheon.<br />

Bryce Morrison<br />

3<br />

GÉZA ANDA JOUE TCHAÏKOVSKY<br />

ET BRAHMS<br />

Nous sommes aujourd’hui peut-être plus que jamais<br />

en quête de musiciens qui se distinguent par leur<br />

individualité. Ce terme n’est pas synonyme d’une approche<br />

résolument “différente” ou idiosyncratique qui placerait<br />

l’artiste au-dessus du compositeur; il s’agit plutôt d’un<br />

équilibre subtil entre création et recréation. En ce sens,<br />

Géza Anda (1921–1976), dont la mort prématurée priva<br />

le monde d’une voix et d’une présence hors du commun,<br />

fut <strong>to</strong>ujours fidèle aux partitions, tant dans l’esprit que<br />

dans la lettre, mais en ajoutant systématiquement à ses<br />

interprétations une <strong>to</strong>uche personnelle.<br />

Parmi les premiers grands succès d’Anda au disque<br />

figure son enregistrement des Variations sur un thème de<br />

Paganini de Brahms, réalisé en 1953. Son interprétation –<br />

probablement la plus frappante et originale de <strong>to</strong>utes – fit<br />

découvrir au public son agilité impeccable, son charme et<br />

l’éclat magique de sa sonorité ainsi que son raffinement<br />

et son intelligence musicale. En 1957, Anda joua les trois<br />

concer<strong>to</strong>s pour piano de Brahms lors d’un même concert<br />

(une véritable performance non seulement musicale<br />

mais aussi sportive), et vers la fin de sa vie trop brève, il<br />

releva le défi <strong>to</strong>talement différent d’interpréter l’intégrale<br />

des concer<strong>to</strong>s pour piano de Mozart en concert et pour<br />

le disque. À la même époque, il avouait, avec une pointe<br />

de regret, qu’il ne possédait plus l’empathie nécessaire<br />

pour rendre certains petits délices de virtuosité tels que<br />

la Valse lente de Delibes/Dohnányi (Coppélia, Acte un).<br />

Décrit par Furtwängler comme “un troubadour<br />

du piano”, Anda accordait une extrême importance à<br />

l’inspiration vocale qui se dissimule derrière maintes pièces<br />

pour le clavier (par la suite, il réalisa des enregistrements<br />

avec Elisabeth Schwarzkopf). Lors de ses masterclasses,

les étudiants percussifs à l’excès étaient vite rabroués, et<br />

on ne sera guère surpris d’apprendre que des pianistes<br />

tels qu’Alfred Cor<strong>to</strong>t et Edwin Fischer figuraient parmi les<br />

artistes qu’il admirait le plus.<br />

Cependant, comme il le montre dans ces<br />

interprétations du Concer<strong>to</strong> n o 1 de Tchaïkovsky (non<br />

publiées auparavant) et du Concer<strong>to</strong> n o 2 de Brahms, Anda<br />

pouvait être magnifiquement immodéré ou versatile, avec<br />

de soudains accès de vitesse et un brio qui lui valurent<br />

d’être considéré par un critique comme “aussi explosif que<br />

M. Vichinsky – un homme politique russe – lors d’une<br />

conférence”. Dans le premier mouvement du Tchaïkovsky,<br />

alors qu’Anda progresse délibérément mais sans la<br />

moindre rigidité, il ne faut pas attendre longtemps pour<br />

rencontrer ces crescendos subits; une pincée de paprika<br />

hongrois, si l’on peut dire. Les réflexes sont rapides,<br />

nerveux et imprévisibles, tel un cri bien éloigné de la<br />

tradition russe, et si Anda est sensible au lyrisme apaisant<br />

du second thème, il compense <strong>to</strong>ujours les passages<br />

détendus par une bravoure qui à d’autres endroits fait<br />

frissonner. Le romancier D.H. Lawrence n’avait-il pas<br />

écrit : “sans le piquant que le grain de sésame apporte<br />

au nougat, celui-ci serait écœurant”. L’ Andantino est<br />

un autre cas d’espèce : la délicatesse poétique d’Anda<br />

dans les sections extrêmes est contrebalancée par une<br />

véritable valse de feux follets <strong>to</strong>ut au long du Prestissimo<br />

central, tellement léger qu’il évoque chez l’auditeur le<br />

caractère fantasque du Pres<strong>to</strong> scintillant qui est au milieu<br />

de l’Adagio du Deuxième Concer<strong>to</strong> pour piano de Bartók.<br />

À partir d’Anda, ces pages sont devenues un véritable<br />

“scherzo des lucioles”.<br />

Dans l’écriture plus dense du Deuxième Concer<strong>to</strong> pour<br />

piano de Brahms, loin de “la plus grande des batailles<br />

pour piano et orchestre”, le talent artistique d’Anda est<br />

encore une fois suprême. Pour de nombreux mélomanes,<br />

le Deuxième Concer<strong>to</strong> pour piano de Brahms est le plus<br />

beau de <strong>to</strong>us les concer<strong>to</strong>s pour piano. Il est extrêmement<br />

exigeant pour le pianiste. Il est no<strong>to</strong>ire que Brahms avait<br />

composé cette œuvre après qu’une pianiste eut donné<br />

une interprétation très faible de son Premier Concer<strong>to</strong>; il<br />

déclara alors vouloir écrire un concer<strong>to</strong> qu’aucune femme<br />

ne pût jouer (par la suite, à une époque plus féministe,<br />

l’interprétation de l’œuvre fut considérée comme un<br />

véritable défi, qui fut relevé par plusieurs grandes pianistes<br />

telles que Myra Hess, Clara Haskil, Alicia de Larrocha –<br />

à contrecœur – et Annie Fischer, pour ne citer que ces<br />

quatre artistes). Ce concer<strong>to</strong> occupait une place centrale<br />

dans le réper<strong>to</strong>ire d’Anda, qui répond largement à ses<br />

exigences redoutables. Déployant un jeu à la fois agile<br />

et magistral, il savoure réellement le défi, sur<strong>to</strong>ut dans<br />

l’Allegro introductif où, comme nous dit Sir Donald Tovey,<br />

“l’air semble empli de murmures et du battement d’ailes<br />

puissantes”. Et dans le “finale, grandiose et enfantin”<br />

(Tovey), il est brillamment alerte, apportant la “splendeur<br />

de gaies cabrioles” à l’éblouissante conclusion “un poco<br />

più mosso”.<br />

Nous retrouvons dans cette collaboration avec Solti<br />

pour Tchaïkovsky et avec Klemperer pour Brahms une<br />

confirmation supplémentaire du génie d’Anda. Et si ces<br />

enregistrements raviveront une légende pour certains, ils<br />

feront découvrir à d’autres un musicien dont la verve et<br />

le style lui valent sans conteste une place de choix au<br />

panthéon des pianistes.<br />

Bryce Morrison<br />

Traduction : Sophie Liwszyc<br />

GÉZA ANDA SPIELT TSCHAIKOVSKIJ<br />

UND BRAHMS<br />

Heute suchen wir vielleicht mehr denn je nach Musikern,<br />

die sich durch ihre Individualität auszeichnen. Das ist<br />

nicht das Gleiche wie ein bewusst “unterschiedlicher”<br />

oder idiosynkratischer Ansatz, der den Künstler über<br />

den Komponisten stellt, sondern eher ein feinfühliger<br />

Balanceakt zwischen Schöpfer und Nachschöpfer. Und<br />

in diesem Sinne war Géza Anda (1921–1976), dessen<br />

früher Tod die Welt einer raren Stimme und Präsenz<br />

beraubte, immer dem Buchstaben als auch dem Geist<br />

der Partitur getreu, und konnte ihr trotzdem jeweils eine<br />

persönliche Note zufügen.<br />

Zu Andas ersten bedeutenden Triumphen gehört seine<br />

Aufnahme von Brahms’ Paganini Variationen von 1953.<br />

Seine Interpretation – zweifellos die eindrucksvollste und<br />

originellste aller Aufführungen – machte das Publikum<br />

auf seine makellose Fingerfertigkeit, den Glanz und Reiz<br />

seines zauberhaften Tons und seinen musikalischen Witz<br />

und Finesse aufmerksam. 1957 spielte Anda die drei<br />

Klavierkonzerte Bartóks in einem einzigen Konzert (eine<br />

musikalische Meisterleistung, von den athletischen<br />

Ansprüchen ganz zu schweigen) und gegen Ende seines<br />

allzu kurzen Lebens stellte er sich die Herausforderung,<br />

sämtliche Mozart-Klavierkonzerte sowohl im Konzertsaal<br />

als auch auf Schallplatte zu spielen. Zur gleichen Zeit<br />

bemerkte er mit leichtem Bedauern, dass er nicht mehr<br />

die nötige Einfühlung für virtuose Konfektionen wie den<br />

Delibes/Dohnányi Valse lente (Coppélia, 1. Akt) besaß.<br />

Furtwängler beschrieb ihn als “Troubadour des<br />

Klaviers”, da Anda größten Wert auf die gesangliche<br />

Inspiration legte, die hinter soviel Klaviermusik steckte<br />

(und er sollte auch Aufnahmen mit Elisabeth Schwarzkopf<br />

machen). Übermäßig perkussive Schüler wurden in seinen<br />

4 5<br />

Meisterkursen kurz abgehandelt, und es überrascht kaum,<br />

dass Pianisten wie Alfred Cor<strong>to</strong>t und Edwin Fischer zu den<br />

Künstlern gehörten, die er am meisten bewunderte.<br />

Anda zeigt in den vorliegenden Interpretationen von<br />

Tschaikovskijs Konzert Nr. 1 (bislang unveröffentlicht)<br />

und Brahms’ Konzert Nr. 2, dass er überwältigend<br />

leidenschaftlich und volatil sein konnte, voll plötzlicher<br />

Tempowendungen und mit einer Brillanz, die einen Kritiker<br />

zu folgender Beschreibung veranlasste: “so explosiv wie<br />

Herr Vyschinskij – ein russischer Politiker – auf einer<br />

Konferenz”. Im ersten Satz des Tschaikovskij, wo Anda<br />

bestimmt, aber nie unflexibel voranschreitet, braucht man<br />

nicht weit zu gehen, um solch plötzlichen Crescendi zu<br />

begegnen; eine Prise ungarischer Paprika, sozusagen.<br />

Seine schnellen, nervösen und unvorhersehbaren<br />

Reflexe sind weit von allgemein akzeptierter russischer<br />

Ansicht entfernt, und obwohl Anda feinfühlig auf die<br />

beschwichtigende Lyrik des zweiten Themas eingeht,<br />

balanciert er solche Entspannung andernorts immer<br />

mit prickelnder Bravour aus. Wie der Schriftsteller<br />

D.H. Lawrence es einmal ausdrückte: “Das Sesamkorn<br />

gibt dem Nougat seinen Schärfe, sonst wäre er ekelhaft<br />

süß”. Das Andantino ist ein weiteres Paradebeispiel:<br />

Andas poetische Feinfühligkeit in den Eckteilen wird<br />

durch eine Irrlichterjagd durch den Prestissimo-Mittelteil<br />

ausgewogen, deren Flüchtigkeit uns auf sein ähnliches<br />

Gespür für Phantasie im flimmernden Pres<strong>to</strong> im Kern<br />

des Adagios in Bartóks 2. Klavierkonzert vorausblicken<br />

lässt. Von Anda gespielt wurden solche Passagen<br />

wahrlich zu einem “Scherzo der Glühwürmchen”.<br />

Im enger verwobenen Satz von Brahms’<br />

2. Klavierkonzert, weit entfernt von einer der “größten<br />

Schlachten für Klavier und Orchester”, ist Andas<br />

Kunstfertigkeit wiederum überragend. Viele Hörer halten<br />

Brahms’ Zweite für das größte aller Klavierkonzerte, und

es stellt höchste Ansprüche an das Durchhaltevermögen<br />

des Pianisten. Brahms komponierte das Konzert angeblich<br />

nach einem unzulänglichen Vortrag seines Ersten von<br />

einer Dame; er soll gesagt haben, dass er ein Konzert<br />

schreiben wolle, das keine Frau spielen könnte (eine<br />

Herausforderung, der sich in feministischeren Zeiten viele<br />

große Pianistinnen stellten, unter ihnen Myra Hess, Clara<br />

Haskil, Alicia de Larrocha (wiewohl zögernd) und Annie<br />

Fischer, um nur vier zu nennen). Dieses Konzert nahm in<br />

Andas Reper<strong>to</strong>ire eine zentrale Stelle ein, und kann sich all<br />

seinen beängstigenden Ansprüchen mit Leichtigkeit stellen.<br />

Sein Spiel ist sowohl geschickt als auch majestätisch und<br />

er ergötzt sich an der Herausforderung, besonders in dem<br />

Augenblick im einleitenden Allegro, wo, wie Sir Donald<br />

Tovey es ausdrückt, “die Luft von Geflüster und dem<br />

Schlagen mächtiger Flügel angefüllt scheint”. Sein Ansatz<br />

zum “großen, kindlichen Finale” (wiederum Tovey) ist<br />

brillant: eine “Glorie hüpfenden Frohsinns”, die in einem<br />

blendenden “un poco più mosso” schließt.<br />

Hier, in Partnerschaft mit Solti in Tschaikovskij und<br />

Klemperer in Brahms, finden sich weitere Belege für Andas<br />

Genie. Und wenn dies für einige eine Legende wieder<br />

aufleben lässt, wird es anderen einen Musiker vorstellen,<br />

dessen Schwung und Stil ihn hoch in das pianistische<br />

Pantheon einreihen.<br />

Bryce Morrison<br />

Übersetzung: Renate Wendel<br />

For ICA Classics<br />

Executive Producer/Head of Audio: John Pattrick<br />

Music Rights Executive: Aurélie Baujean<br />

Head of DVD: Louise Waller-Smith<br />

Executive Consultant: Stephen Wright<br />

For WDR<br />

Executive Producer: Karl O. Koch<br />

Recording Producers: Hans Schulze-Ritter (Brahms),<br />

Hans-Georg Daehn (Tchaikovsky)<br />

Remastering: Dirk Franken<br />

With special thanks <strong>to</strong> Florian Streit<br />

Introduc<strong>to</strong>ry note & translations<br />

2013 <strong>International</strong> <strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Artists</strong> Ltd<br />

Booklet editing: WLP Ltd<br />

Art direction: Georgina Curtis for WLP Ltd<br />

1958 (Tchaikovsky), 1954 (Brahms) Westdeutscher Rundfunk Köln<br />

Licensed <strong>to</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Artists</strong> Ltd<br />

by WDR mediagroup licensing GmbH<br />

2013 <strong>International</strong> <strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Artists</strong> Ltd<br />

Technical Information<br />

Studer A816 1/4" analog tape machine<br />

George Massenburg 9500 Mastering EQ<br />

TC M6000<br />

Lexicon 960 Reverb<br />

B&W 803D Moni<strong>to</strong>r<br />

Linn Chakra-Series Amps<br />

Lawo Zirkon VisTool digital Moni<strong>to</strong>r & Switch Matrix<br />

RTW Surrond Sound Moni<strong>to</strong>r 30900<br />

Magix Sequoia v11.03 Non Linear Editing System<br />

Algorithmics Renova<strong>to</strong>r<br />

Mono ADD<br />

WDR The Cologne Broadcasts<br />

Sourced from the original master tapes<br />

Also available on CD and digital <strong>download</strong>:<br />

ICAC 5000<br />

Beethoven: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong>s Nos.1 & 3<br />

New Philharmonia Orchestra · Sir Adrian Boult<br />

Emil Gilels<br />

ICAC 5003<br />

Brahms: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.2<br />

Chopin · Falla<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester<br />

Chris<strong>to</strong>ph von Dohnányi · Arthur Rubinstein<br />

Gramophone Edi<strong>to</strong>rs’ Choice<br />

For a free promotional CD sampler including<br />

highlights from the ICA Classics CD catalogue,<br />

please email info@icaclassics.com.<br />

WARNING:<br />

All rights reserved. Unauthorised copying, reproduction, hiring, lending,<br />

public performance and broadcasting prohibited. Licences for public<br />

performance or broadcasting may be obtained from Phonographic<br />

Performance Ltd., 1 Upper James Street, London W1F 9DE. In the<br />

United States of America unauthorised reproduction of this recording<br />

is prohibited by Federal law and subject <strong>to</strong> criminal prosecution.<br />

Made in Austria<br />

ICAC 5004<br />

Haydn: Piano Sonata No.62<br />

Weber: Piano Sonata No.3<br />

Schumann · Chopin · Debussy<br />

Svia<strong>to</strong>slav Richter<br />

Diapason d’or<br />

ICAC 5006<br />

Verdi: La traviata<br />

Maria Callas · Cesare Valletti · Mario Zanasi<br />

The Covent Garden Opera Chorus & Orchestra<br />

Nicola Rescigno · Supersonic Award (Pizzica<strong>to</strong> Magazine)<br />

6<br />

7

ICAC 5007<br />

Tchaikovsky: Symphony No.1 ‘Winter Dreams’<br />

Stravinsky: The Firebird Suite (1945 version)<br />

BBC Symphony Orchestra · Philharmonia Orchestra<br />

Evgeny Svetlanov<br />

ICAC 5008<br />

Liszt: Rhapsodie espagnole<br />

Hungarian Rhapsody No.2<br />

CPE Bach · Couperin · Scarlatti<br />

Georges Cziffra<br />

ICAC 5021<br />

Mahler: Symphony No.3 · Debussy: La Mer<br />

Kölner Rundfunkchor · Kölner Domchor<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester · Dimitri Mitropoulos<br />

Toblacher Komponierhäuschen <strong>International</strong><br />

Record Prize 2011<br />

ICAC 5032<br />

Beethoven: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.4<br />

Tchaikovsky: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.2<br />

Hallé Orchestra · Sir John Barbirolli<br />

London Philharmonic Orchestra · Kirill Kondrashin<br />

Emil Gilels<br />

ICAC 5019<br />

Brahms: Symphony No.1<br />

Elgar: Enigma Variations<br />

BBC Symphony Orchestra<br />

Sir Adrian Boult<br />

ICAC 5020<br />

Rachmaninov: Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini<br />

Prokofiev: Piano Sonata No.7<br />

Stravinsky: Three Scenes from Petrushka<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester · Zdeněk Mácal<br />

Shura Cherkassky<br />

ICAC 5033<br />

Mahler: Symphony No.3<br />

Waltraud Meier · E<strong>to</strong>n College Boys’ Choir<br />

London Philharmonic Choir & Orchestra<br />

Klaus Tennstedt<br />

Choc de Classica · Diapason d’or<br />

8 9<br />

ICAC 5045<br />

Chopin: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.1<br />

Beethoven: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.4<br />

Ot<strong>to</strong> Klemperer · Chris<strong>to</strong>ph von Dohnányi<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester · Claudio Arrau<br />

Supersonic Award (Pizzica<strong>to</strong> Magazine)

ICAC 5046<br />

Rossini: Il barbiere di Siviglia<br />

Rolando Panerai · Teresa Berganza · Luigi Alva<br />

The Covent Garden Opera Chorus & Orchestra<br />

Carlo Maria Giulini<br />

ICAC 5047<br />

Mendelssohn: A Midsummer Night’s Dream<br />

Beethoven: Symphony No.8<br />

Kölner Rundfunkchor · Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester<br />

Ot<strong>to</strong> Klemperer<br />

ICAC 5054<br />

Beethoven: Missa solemnis<br />

Kölner Rundfunkchor<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester<br />

William Steinberg<br />

ICAC 5055<br />

Schubert: Impromptu in B flat<br />

Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Nos. 6 & 29<br />

Wilhelm Backhaus<br />

ICAC 5048<br />

Brahms: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.1<br />

Chopin · Liszt · Schumann · Albéniz<br />

BBC Symphony Orchestra · Rudolf Kempe<br />

Julius Katchen<br />

ICAC 5053<br />

Holst: The Planets<br />

Britten: Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Purcell<br />

BBC Symphony Orchestra<br />

Gennadi Rozhdestvensky<br />

ICAC 5061<br />

Verdi: Falstaff<br />

Fernando Corena · Anna Maria Rovere · Fernanda Cadoni<br />

Glyndebourne Opera Chorus<br />

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra<br />

Carlo Maria Giulini<br />

ICAC 5062<br />

Schumann: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong><br />

Beethoven: Eroica Variations · Piano Sonata No.30<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester · Joseph Keilberth<br />

Annie Fischer<br />

10<br />

11

ICAC 5063<br />

Brahms: Symphony No.3<br />

Elgar: Symphony No.1<br />

BBC Symphony Orchestra<br />

Sir Adrian Boult<br />

Supersonic Award (Pizzica<strong>to</strong> Magazine)<br />

ICAC 5068<br />

Verdi: Requiem · Rossini: Overtures<br />

Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra<br />

Orchestre National de l’ORTF<br />

Igor Markevitch<br />

ICAC 5076<br />

Wolf: Italienisches Liederbuch<br />

Janet Baker · John Shirley-Quirk<br />

ICAC 5078<br />

Rachmaninov: Symphony No.2<br />

Bernstein: Candide – Overture<br />

Philharmonia Orchestra<br />

London Symphony Orchestra<br />

Evgeny Svetlanov<br />

ICAC 5069<br />

Rachmaninov: The Bells<br />

Prokofiev: Alexander Nevsky<br />

BBC Symphony Chorus and Orchestra<br />

Philharmonia Chorus and Orchestra<br />

Evgeny Svetlanov<br />

ICAC 5075<br />

Berlioz: Requiem<br />

Nicolai Gedda<br />

Kölner Rundfunkchor<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester<br />

Dimitri Mitropoulos<br />

ICAC 5079<br />

Grieg · Liszt: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong>s<br />

Lully · Scarlatti<br />

Orchestre National de l’ORTF<br />

Georges Tzipine · André Cluytens<br />

Georges Cziffra<br />

ICAC 5080<br />

Mahler: Das klagende Lied<br />

Janáček: The Fiddler’s Child<br />

Teresa Cahill · Janet Baker · Robert Tear · Gwynne Howell<br />

BBC Symphony Chorus and Orchestra<br />

Gennadi Rozhdestvensky<br />

12<br />

13

ICAC 5081<br />

Schumann: Symphony No.4<br />

Debussy: Le Martyre de Saint Sébastian – Suite<br />

La Mer<br />

Philharmonia Orchestra<br />

Guido Cantelli<br />

ICAC 5084<br />

Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Nos. 3 & 29<br />

‘Hammerklavier’<br />

Bagatelles op.126 nos. 1, 4 & 6<br />

Svia<strong>to</strong>slav Richter<br />

ICAC 5087<br />

Beethoven: Symphony No.3 ‘Eroica’<br />

Smetana: The Bartered Bride – Overture<br />

Orquesta Nacional de España<br />

Orchestre de la Suisse Romande<br />

Ataúlfo Argenta<br />

ICAC 5090<br />

Brahms: Symphony No.1<br />

Martinů: Symphony No.4<br />

Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart des SWR<br />

Klaus Tennstedt<br />

ICAC 5085<br />

Chopin: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong>s Nos. 1 & 2<br />

BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra · Chris<strong>to</strong>pher Adey<br />

BBC Symphony Orchestra · Richard Hickox<br />

Shura Cherkassky<br />

ICAC 5086<br />

Beethoven: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong>s Nos. 2 & 4<br />

Sinfonia Varsovia · Jacek Kaspszyk<br />

Ingrid Jacoby<br />

ICAC 5091<br />

Mahler: Symphony No.5<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester<br />

Hans Rosbaud<br />

ICAC 5093<br />

Brahms: Symphony No.4<br />

Mendelssohn: Symphony No.4 ‘Italian’<br />

BBC Symphony Orchestra<br />

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra<br />

Sir Adrian Boult<br />

14<br />

15