Journal of Film Preservation - FIAF

Journal of Film Preservation - FIAF

Journal of Film Preservation - FIAF

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong><br />

Revue de la Fédération Internationale des Archives du <strong>Film</strong> 63<br />

Revista de la Federación Internacional de Archivos Fílmicos 10/2001<br />

Published by the International Federation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> Archives

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> N° 63<br />

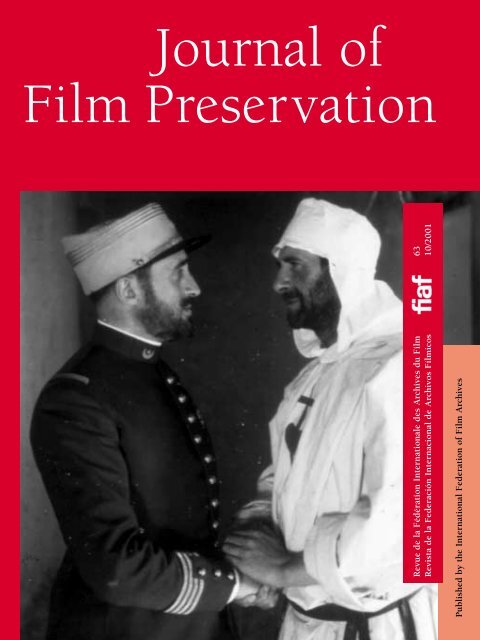

Cover: L’Appel du silence, Léon Poirier.<br />

Courtoisie des Archives du film et du dépôt légal<br />

du CNC, Bois d’Arcy<br />

Cinéma colonial: patrimoine emprunté /<br />

Colonial Cinema: A Borrowed Heritage /<br />

Cine colonial: un patrimonio en préstamo<br />

2 Le cinéma colonial : patrimoine emprunté<br />

Abdelkader Benali<br />

6 L’exotisme et le cinéma ethnographique:<br />

la rupture de La Croisière noire<br />

Marc Henri Piault<br />

17 Hygienic Reform in the French Colonial <strong>Film</strong> Archive<br />

Peter J. Bloom<br />

24 L’Autre dans son propre territoire:<br />

le cinéma australien et les cultures aborigènes<br />

John Emerson<br />

29 Spanish Colonial Cinema: Contours and Singularities<br />

Alberto Elena<br />

36 Francisco Villa: The Use and Abuse <strong>of</strong><br />

Colonialist Cinema<br />

Aurelio de los Reyes<br />

41 Léon Poirier’s L’Appel du silence and the Cult<br />

<strong>of</strong> Imperial France<br />

Steve Ungar<br />

47 Les images de deux guerres, coloniales et impériales.<br />

De l’intimisme à l’apocalypse (de la guerre française<br />

d’Algérie à la guerre américaine du Vietnam)<br />

Benjamin Stora<br />

50 Morocco and Morocco<br />

Charles Silver

October / octobre / octobre 2001<br />

55 Le fonds cinématographique colonial aux Archives du film<br />

et du dépôt légal du CNC (France)<br />

Éric Le Roy’<br />

60 A qui appartiennent les images ?<br />

Marc Ferro<br />

68 Other papers / Autres présentations /<br />

Otras presentaciones<br />

Manuel Madeira, Richard J. Meyer, Emma Sandon,<br />

Mulay Driss Jaïdi, Michel Marie, Gregorio Rocha<br />

71 Bibliographie : cinéma colonial<br />

Bibliography: Colonial Cinema<br />

Bibliografía : cine colonial<br />

74 In Memoriam<br />

Jan de Vaal<br />

Robert Daudelin<br />

José Manuel Costa<br />

Eric Barnouw<br />

Patricia Zimmermann<br />

Hammy Sotto<br />

Clodualdo del Mundo<br />

Publications / Publicaciones<br />

80 Publications Received at the Secretariat<br />

Publications reçues au Secrétariat<br />

Publicaciones recibidas en el Secretariado<br />

84 <strong>FIAF</strong> Bookshop/Librairie/Librería<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong><br />

Half-yearly / Semi-annuel<br />

ISSN 1609-2694<br />

Copyright <strong>FIAF</strong> 2001<br />

Bureau <strong>FIAF</strong> Officers<br />

President / Président<br />

Iván Trujillo Bolio<br />

Secretary General / Secrétaire général<br />

Steven Ricci<br />

Treasurer / Trésorier<br />

Karl Griep<br />

Comité de Rédaction<br />

Editorial Board<br />

Chief Editor / Rédacteur en Chef<br />

Robert Daudelin<br />

Members / Membres<br />

Mary Lea Bandy<br />

Paolo Cherchi Usai<br />

Valeria Ciompi<br />

Christian Dimitriu<br />

Steven Ricci<br />

Hillel Tryster<br />

Eileen Bowser<br />

Corespondents/Correspondants<br />

Claudia Dillmann<br />

Ray Edmondson<br />

Michael Friend<br />

Silvan Furlan<br />

Reynaldo González<br />

Steven Higgins<br />

Eric Le Roy<br />

Juan José Mugni<br />

Donata Pesenti<br />

Graphisme / Design<br />

Meredith Spangenberg<br />

Imprimé / Printed / Impreso<br />

Artoos - Bruxelles / Brussels<br />

Editeur / Publisher<br />

Christian Dimitriu<br />

Editorial Assistant<br />

Olivier Jacqmain<br />

Fédération Internationale des<br />

Archives du <strong>Film</strong> - <strong>FIAF</strong><br />

rue Defacqz 1<br />

1000 Bruxelles / Brussels<br />

Belgique / Belgium<br />

Tel (32-2) 538 3065<br />

Fax (32-2) 534 4774<br />

jfp@fiafnet.org

Le cinéma colonial : patrimoine emprunté<br />

Cinéma colonial: patrimoine emprunté<br />

Colonial Cinema: A Borrowed Heritage<br />

Cine colonial: un patrimonio en préstamo<br />

Abdelkader Benali<br />

Le terme de “cinéma colonial” fait-il encore carillonner les mélodies<br />

folkloriques de l’Atlas, les danses enflammées sous le soleil fiévreux<br />

de l’Afrique, les chants des prières ou les courbes chatoyantes des<br />

mosaïques ? L’imaginaire cinématographique colonial fut, très vite<br />

après les indépendances, pensé soit en terme de condamnation ou de<br />

refus, soit comme un imaginaire de pacotille. Jusqu’au début des<br />

années 80, l’aphorisme de “cinéma exotique” permettait encore de<br />

déjouer toute la charge émotionnelle qu’une telle production est<br />

amenée à dissimuler. Il a fallu attendre les années 90 pour qu’une<br />

nouvelle génération de chercheurs, particulièrement en France, mais<br />

aussi aux Etats-Unis et en Afrique, manifeste ouvertement son intérêt<br />

pour le cinéma colonial. Un intérêt qui relie le regard scientifique et<br />

froid de l’analyse au sentiment de culpabilité et de malaise du<br />

partisan. Par ailleurs, ne répondant pas aux critères esthétiques<br />

édifiés par l’histoire du cinéma, les films coloniaux furent reconnus<br />

comme une production de propagande et, par conséquent, relégués<br />

dans la catégorie des “genres mineurs”.<br />

Malgré l’intérêt scientifique qu’on leur a accordé ces dernières années,<br />

la majorité des films coloniaux constitue encore actuellement ce que<br />

nous pourrions nommer un cinéma d’archives, représentatif d’une<br />

époque révolue et dont les implications formelles et idéologiques ne<br />

sont plus d’actualité. Il est évident que l’héritage conceptuel - d’ordre<br />

historiographique - auquel le cinéma colonial s’est trouvé affilié exige<br />

une vigilance méthodologique et une rigueur analytique sans<br />

lesquelles le film ne jouerait qu’un rôle d’illustration à des idées<br />

préconçues, et ne serait qu’un simple sismographe permettant<br />

d’évaluer visuellement une période historique.<br />

Ce constat étant établi, faudrait-il continuer à considérer l’ensemble<br />

des films coloniaux seulement à partir de leurs implications dans la<br />

pensée coloniale, et dans le processus formel qu’ils établissent en vue<br />

d’intégrer le colonisé dans un système de représentation ? Car,<br />

parallèlement à ce cheminement apparent, le cinéma élabore une<br />

lecture qui échappe à la mécanique pragmatique de l’époque. Les<br />

cinéastes n’ont pas toujours gagné les colonies africaines et asiatiques<br />

dans le seul but de répondre à des attentes <strong>of</strong>ficielles, ils n’ont pas<br />

réalisé que des films de commande, et n’avaient pas pour seul<br />

objectif de créer chez les peuples européens l’idée d’un impérialisme<br />

déjà largement consacré. C’est la raison pour laquelle les films<br />

coloniaux présentent un double discours qui se situe dans deux<br />

strates différentes de leur contenu, qu’il soit fictionnel ou à caractère<br />

documentaire. Lorsque l’on pousse l’analyse au-delà des effets<br />

immédiats qu’ils comportent, on constate que la vision propagandiste<br />

2 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 63 / 2001

Courier du sud, Pierre Billon.<br />

Source: Les Archives du film et du dépot légal du CNC, Bois d’Arcy<br />

L’Atlantide, Jacques Feyder.<br />

Source: Les Archives du film et du dépot légal du CNC, Bois d’Arcy<br />

est sans cesse contrariée par des signes qui remettent en cause<br />

l’aventure coloniale elle-même. Il s’agit là de l’affirmation du<br />

cinéma comme un objet complexe, cohérent et autonome à la<br />

fois, et qui procède d’un langage spécifique irréductible à la<br />

réalité externe et déjouant sans cesse les contraintes de la<br />

conjoncture. Si le cinéma colonial affiche ouvertement les<br />

présupposés de l’idéologie coloniale, ses structures de<br />

significations ne sont pas pour autant figées. A ce titre, à la<br />

dominante optimiste et univoque de “missions civilisatrices” des<br />

années trente succède dès le début des années quarante une<br />

vision moins sûre, de facture beaucoup moins propagandiste et<br />

beaucoup plus nuancée. S’agissait-il là d’une perte de contrôle<br />

sur les signes ou d’une affirmation du clivage séparant le cinéma<br />

du discours colonial et déjouant par la même occasion le<br />

3 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 63 / 2001<br />

This introduction to the symposium<br />

summarizes the state <strong>of</strong> current ideas about<br />

colonial cinema. Soon after independence,<br />

colonial cinema was thought <strong>of</strong> in terms <strong>of</strong><br />

condemnation or refusal. But it was not until<br />

the nineties that a new generation <strong>of</strong><br />

scholars began to manifest its interests in<br />

colonial cinema, with modern scientific<br />

analysis and sensitivity to human feelings.<br />

Without responding to the esthetic criteria <strong>of</strong><br />

the history <strong>of</strong> cinema, the colonial films<br />

would be recognized only as propaganda,<br />

and relegated to the category <strong>of</strong> minor<br />

genres. It is evident that a rigorous<br />

analytical methodology is necessary, for<br />

without it, the films would only play an<br />

illustrative role <strong>of</strong> preconceived ideas.<br />

Is it still necessary to continue to consider<br />

the group <strong>of</strong> colonial films only for their role<br />

in colonial thought and their integration <strong>of</strong><br />

the colonized in a system <strong>of</strong> representation ?<br />

Because, parallel to this, the cinema allows<br />

for a reading which escapes the pragmatic<br />

operations <strong>of</strong> the time. The filmmakers have<br />

not always gone to the African and Asian<br />

colonies just for <strong>of</strong>ficial purposes, they have<br />

not only produced films on order, and have<br />

not the single object <strong>of</strong> building European<br />

imperialism. That is why the colonial films<br />

present a double discourse situated in two<br />

different layers by their content, be it<br />

fictional or documentary. When one pushes<br />

the analysis beyond the immediate effects<br />

that they carry, one realizes that the<br />

propagandistic vision is constantly<br />

contradicted by the colonial adventure itself.<br />

Thus, the dominant message <strong>of</strong> « civilizing<br />

missions » <strong>of</strong> the thirties are succeeded in<br />

the beginning <strong>of</strong> the forties by a vision less<br />

sure <strong>of</strong> itself, becoming much less<br />

propagandistic and more nuanced. Does this<br />

mean a loss <strong>of</strong> control, or the separating <strong>of</strong><br />

cinema from the colonial discourse ?<br />

The colonial cinema is also an affair <strong>of</strong> the<br />

perception <strong>of</strong> the Other ; and this same<br />

perception escapes the pragmatic vision <strong>of</strong><br />

the moment and becomes synonymous <strong>of</strong><br />

affirmation and the construction <strong>of</strong> an image<br />

<strong>of</strong> self. It is written into an anthropological<br />

line that goes back to the nineteenth century.<br />

It is constructed <strong>of</strong> images built by painting,<br />

literature and travel narratives, an exotic<br />

vision for the colonial discourse. In such a<br />

construction, a series <strong>of</strong> oppositions are<br />

formulated between nature/culture,<br />

savage/civilized, group/individual,<br />

religion/science, etc., and in this duality a<br />

polarity is set up between the colonial hero<br />

and his opposite : “the native”.<br />

The Rabat symposium gives us the occasion

to go beyond the mechanical link set up until<br />

now between the colonial cinema and the<br />

ideology that produced it. The scholars<br />

possess sufficient scientific tools, and a body<br />

<strong>of</strong> material, films which have been<br />

discovered and restored in recent years, to<br />

place the colonial film at the center <strong>of</strong><br />

interdisciplinary approaches in order to go<br />

deeper. If the colonial fiction film has been<br />

the object <strong>of</strong> numerous investigations,<br />

several dozens <strong>of</strong> documentaries and<br />

actualities preserved in different European<br />

archives remain still unknown or little<br />

studied.<br />

The remainder <strong>of</strong> the introduction then<br />

describes the several kinds <strong>of</strong> papers that are<br />

delivered at the symposium.<br />

La Croix du sud, André Hugon.<br />

Source: Les Archives du film et du dépot légal<br />

du CNC, Bois d’Arcy<br />

Dans l’ombre du harem, Léon Mathot.<br />

Source: Les Archives du film et du dépot légal<br />

du CNC, Bois d’Arcy<br />

rapport mécanique, couramment évoqué, entre l’imaginaire<br />

cinématographique et le pragmatisme idéologique colonial ?<br />

Le cinéma colonial est aussi une affaire de perception de l’Autre; et<br />

cette même perception échappe à la vision pragmatique et<br />

conjoncturelle du moment et devient synonyme de l’affirmation et de<br />

la construction d’une image de soi. Il s’inscrit dans une lignée<br />

anthropologique dont les origines remontent au XIXème siècle. Il<br />

récupère toute une imagerie édifiée par la peinture, la littérature et les<br />

récits de voyage, assurant ainsi le passage d’une vision exotique à un<br />

discours proprement colonial. A travers une telle construction, une<br />

série d’oppositions se formule alors entre nature/culture,<br />

sauvage/civilisé, groupe/individu, religion/science, etc. et au sein de<br />

cette dualité s’installe une polarité entre le héros colonial et son<br />

contraire: “l’indigène”. Dès lors, l’espace colonial n’est autre que<br />

l’antidote du monde occidental. Cependant, ces constances ne<br />

représentent que des données immédiates et correspondent<br />

seulement à la partie apparente du discours<br />

cinématographique colonial.<br />

Le Congrès de la <strong>FIAF</strong>: un cadre<br />

d’investigation de prédilection<br />

Le symposium de Rabat nous <strong>of</strong>fre l’occasion de<br />

dépasser justement ce lien mécanique installé<br />

jusqu’ici entre le cinéma colonial et l’idéologie<br />

qui l’a produit. Un dépassement pour lequel les<br />

chercheurs possèdent un outillage scientifique<br />

suffisant et une matière audiovisuelle de plus en<br />

plus foisonnante. En plus des quelques films<br />

découverts ces dernières années, beaucoup ont<br />

été restaurés et peuvent être communiqués et<br />

étudiés dans les conditions les plus favorables. La confrontation des<br />

différents fonds européens permet d ‘établir un état des lieux de la<br />

production cinématographique coloniale dans<br />

sa diversité. Aussi, les nouvelles approches<br />

scientifiques du cinéma nous permettent<br />

également de mettre le film colonial au centre<br />

d’une interdisciplinarité afin de mieux le<br />

sonder. Par ailleurs, si le film colonial de fiction<br />

a fait l’objet de nombreuses investigations,<br />

plusieurs dizaines de films documentaires et de<br />

bandes d’actualité conservés dans différents<br />

centres d’archives européens demeurent encore<br />

inconnus ou sous-exploités.<br />

Les différentes communications réunies dans ce<br />

volume tentent de répondre à plusieurs<br />

questions en prenant en compte un maximum de paramètres<br />

historiques, esthétiques et sociologiques qui composent le contexte<br />

général d’appréhension du cinéma colonial. Dans un premier temps,<br />

il s’agit d’examiner la politique générale de la production<br />

4 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 63 / 2001

cinématographique coloniale à travers sa typologie et décrire son<br />

environnement historique (Moulay Driss Jaïdi). Comment s’effectue<br />

la mise en perspective historique du cinéma colonial, situé par<br />

rapport à la tradition visuelle du XIXème siècle ? De quelle façon le<br />

cinéma s’inscrit-il dans cette lignée de l’exotisme tout en modifiant<br />

ses préceptes et ses normes à la fois esthétiques et idéologiques ? A<br />

partir de là, deux interrogations fondamentales surgissent : les<br />

concepts anthropologiques sont-ils les seuls éléments à prendre en<br />

compte dans l’analyse des films coloniaux (Marc- Henri Piault) ?<br />

Qu’en est-il de l’esthétisme cinématographique colonial et quels sont<br />

les référents dans lesquels elle puise sa matière ? Quel serait le poids<br />

des images dans la construction d’une identité nationale en utilisant<br />

l’Autre comme adjuvant du Soi ? Il s’agit, dans la perspective, de créer<br />

un système de référence non plus d’un film à une autre (Benjamin<br />

Stora). Cette re-contextualisation à la fois historique et conceptuelle<br />

est une opération fondamentale dans la problématisation du cinéma<br />

colonial et sa constitution comme objet d’étude.<br />

Ensuite, si le cinéma colonial de fiction n’est pas un genre qui<br />

fonctionne en circuit fermé, dans un univers fictionnel exclusivement<br />

cinématographique, c’est qu’il possède des équivalents voire même<br />

des homologues. Qu’en est-il par exemple de Hollywood et de ses<br />

fictions historiques, orientalistes et exotiques ? Quel serait le<br />

fondement d’un système de parenté et de filiation que l’on peut<br />

établir entre le western américain et le film colonial européen par<br />

exemple ? Et, par conséquent, dans quelle mesure le principe de<br />

genre cinématographique peut-il fonctionner dans la catégorisation<br />

esthétique du film colonial (Michel Marie) ? Quels sont les motifs à<br />

la fois narratifs, esthétiques et structurels pouvant établir des<br />

passerelles entre le film colonial et les autres genres<br />

cinématographiques consacrés ? En ce qui concerne les films<br />

documentaires, il faudrait redéfinir la nature des liens qui relient leur<br />

production dans les colonies avec les différentes étapes de<br />

l’expansion. Il faudrait également s’interroger sur leur contenu et<br />

leurs structures en vue d’établir une véritable pédagogie de l’aventure<br />

coloniale à travers le cinéma (Peter Bloom).<br />

Enfin, et à l’issue de telles investigations, une question capitale<br />

s’impose : à qui appartiennent les films coloniaux ? S’inscrivent-ils<br />

seulement dans la mémoire européenne ou appartiennent-ils aussi<br />

aux pays anciennement colonisés selon le principe élémentaire du<br />

droit à l’image (Marc Ferro) ? Comment ces mêmes pays<br />

s’acheminent-ils vers une revendication de ces images au nom de la<br />

mémoire collective et de l’identité historique qu’ils véhiculent ? Selon<br />

quels principes d’appropriation (ou de rejet) le film colonial se<br />

trouve-t-il au cœur d’une mémoire croisée, et quelles sont les règles<br />

épistémologiques sur lesquelles se fondent ces deux opérations ?<br />

L’ensemble de ces interrogations fait que le symposium de Rabat n’est<br />

pas un simple débat de plus, mais une série d’investigations nourries,<br />

en partie, par la confrontation entre des démarches analytiques<br />

5 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 63 / 2001<br />

Inmediatamente después de la<br />

independencia, el cine colonial fue<br />

considerado sólo en términos de condena y<br />

rechazo. Recién en los años noventa, una<br />

nueva generación de investigadores comenzó<br />

a interesarse por el cine colonial empleando<br />

un esquema de análisis nuevo y<br />

manifestando mayor sensibilidad hacia los<br />

sentimientos humanos.<br />

La ausencia de criterios estéticos en el<br />

estudio de la historia del cine, haría de las<br />

películas coloniales simples documentos de<br />

propaganda, y reduciría el cine colonial a la<br />

categoría de género menor. Resulta pues<br />

evidente la necesidad de aplicar una<br />

metodología analítica rigurosa. De lo<br />

contrario, el análisis de estas películas sólo<br />

serviría para ilustrar ideas preconcebidas.<br />

Ya no resulta suficiente con considerar a las<br />

películas coloniales en su simple papel en el<br />

pensamiento colonialista y la integración del<br />

colonizado en un sistema de representación.<br />

El cine permite ir más lejos en el análisis.<br />

Los directores de cine no sólo viajaron a<br />

colonias africanas y asiáticas por motivos<br />

<strong>of</strong>iciales, no sólo produjeron películas por<br />

encargo de sus gobiernos, y no siempre<br />

tuvieron como objetivo principal la<br />

construcción del imperialismo europeo. Es<br />

por ello que el cine colonial se presenta<br />

como un doble lenguaje, situado a dos<br />

niveles, independientemente de que se trate<br />

de cine de ficción o documental. Un análisis<br />

más preciso muestra que la visión<br />

propagandística de las películas en general<br />

contradice a la propia aventura colonial. Al<br />

mensaje de la “misión civilizadora”<br />

dominante en los años 30 sucede una visión<br />

mucho menos segura de sí misma (menos<br />

propagandística y más matizada) a<br />

comienzos de la década del 40. ¿Qué<br />

significa esto? ¿Acaso una pérdida de<br />

control? ¿O la dicotomía entre el cine y el<br />

discurso colonial?<br />

El cine colonial es también asunto de la<br />

percepción del Otro. Esta percepción escapa<br />

a la realidad concreta del momento, se torna<br />

en sinónimo de la construcción y afirmación<br />

de la imagen de sí mismo y se inscribe en<br />

una visión antropológica propia del siglo<br />

XIX. Esta construcción se basa en imágenes<br />

creadas por la pintura, la literatura, los<br />

relatos de viajes y representa una visión<br />

exótica de la que se nutre el discurso<br />

colonial, y de la que se desprende una serie<br />

de dualidades, tales como<br />

naturaleza/cultura, salvaje/civilizado,<br />

grupo/individuo, religión/ciencia, etc. De<br />

estas dualidades surge finalmente la<br />

polaridad entre el héroe colonial y su<br />

opuesto: “el indígena”.

El simposio de Rabat nos brinda la<br />

oportunidad de ir más allá de la relación<br />

mecánica entre el cine colonial y la ideología<br />

subyacente. Los investigadores disponen de<br />

los instrumentos científicos adecuados y de<br />

un corpus de material fílmico rescatado en<br />

los últimos años que les permiten ubicar al<br />

cine colonial en el centro de un enfoque<br />

interdisciplinario y pr<strong>of</strong>undizar el análisis.<br />

Pese a que el cine colonial haya sido objeto<br />

de numerosas investigaciones, documentales<br />

y noticiarios conservados en los Archivos<br />

europeos, siguen siendo pocas las películas<br />

conocidas o estudiadas.<br />

variées et dans un cadre propice à la réflexion sur le film en tant<br />

qu’objet patrimonial. D’une part, le recul historique aidant, le regard<br />

analytique et froid l’emporte sur la charge émotionnelle à travers le<br />

cinéma colonial a été pendant longtemps appréhendé. D’autre part,<br />

évoquer le film colonial en impliquant les responsables des<br />

différentes institutions d’archives et de conservation<br />

cinématographiques est une gageure qui revitalise le cinéma colonial<br />

en tant que problématique. Il s’agit désormais de concevoir ce dernier<br />

avant tout comme un objet qu’une période historique complexe nous<br />

a légué mais dot les implications sur le présent sont nombreuses.<br />

C’est la raison pour laquelle les différents axes de réflexion et<br />

d’analyse prennent les traits d’un parcours dont l’objectif final est de<br />

penser le film colonial en terme de patrimoine partagé ; un<br />

aboutissement dont l’originalité est liée moins à sa nouveauté qu’au<br />

contexte dans lequel il est postulé.<br />

L'exotisme et le cinéma ethnographique:<br />

la rupture de La Croisière noire<br />

Marc Henri Piault<br />

Je voudrais proposer ici quelques réflexions concernant la nature de<br />

l’exotisme et quelques-unes unes des raisons qui ont pu en<br />

différencier relativement le positivisme ethnographique, notamment<br />

entre les deux guerres mondiales.<br />

En premier lieux, j’essayerai de rappeler le contexte et la nature qui<br />

unissent le cinéma et l’ethnologie, puis j’évoquerai quelques éléments<br />

- parfois contradictoires - d’identification de l’exotisme, enfin<br />

j’indiquerai certaines raisons de penser pourquoi le film de Léon<br />

Poirier, La Croisière noire, introduirait une rupture dans l’ordre des<br />

représentations simplement exotisantes, rupture n’<strong>of</strong>frant à<br />

l’ethnographie qu’un mode d’utilisation didactique et objectivante<br />

d’un cinéma formellement marqué par l’idéologie coloniale.<br />

J’ai d’ailleurs déjà fait l’observation que la naissance simultanée du<br />

cinématographe et de l’ethnologie de terrain n’était pas une simple<br />

coïncidence. L’un et l’autre participaient en effet à un même processus<br />

de développement de l’observation scientifique lié lui-même à<br />

l’expansion industrielle des Etats-Nations dont un des corollaires était<br />

l’invasion coloniale. L’Europe et les Etats Unis d’Amérique se<br />

trouvaient alors dans une situation paradoxale. Il s’agissait en effet<br />

d’imposer au monde la certitude de leur mission “civilisatrice” et<br />

6 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 63 / 2001

cette mission s’appuyait sur et se justifiait par l’efficacité scientifique.<br />

Mais cette efficience était fondée sur la certitude d’une certaine unité<br />

rationnelle du monde considéré comme totalité, alors précisément<br />

que se découvrait l’extraordinaire diversité des mondes que<br />

découvrait et explorait leur expansionnisme. Cette multiplicité<br />

troublante entraînait donc à la multiplication des procédures<br />

inventoriales, accumulant les “curiosités” et les “exotismes” de toute<br />

la planète et que l’on allait mesurer à l’aune unique de la normalité<br />

historique occidentale, pour ne pas dire “blanche”. Les différences<br />

repérées vont alors être qualifiées, mesurées et identifiées comme des<br />

manques ou des inachèvements le long de ce qui était généralement<br />

considéré comme une progression historique inéluctable.<br />

Les sociétés que l’exploration découvre, deviennent progressivement<br />

des images photographiques puis cinématographiques qui<br />

permettent de transporter véritablement l’Autre, depuis son étrangeté<br />

absolue, depuis ses antipodes, jusqu’à portée de mesure du regard<br />

blanc. La centralité, le caractère de référentialité absolue de la<br />

position occidentale sont ainsi affirmés et démontrés par l’évidence<br />

même de ce transport qui légitime le cadre de référence du<br />

spectateur considéré comme le mètre-étalon de toute chose.<br />

A l’origine la précipitation dans la découverte va entraîner pour les<br />

cinéastes et les anthropologues la même inquiétude. Les uns comme<br />

les autres sont persuadés d’avoir à saisir dans leur ingénuité, dans<br />

leur authenticité, ces sociétés multiples dont on imagine qu’elles<br />

devraient être en dehors de toute l’histoire et qu’ainsi elles seraient<br />

susceptibles d’<strong>of</strong>frir des formes spéciales protégées sinon “pures” de<br />

toute influence extérieure et surtout à l’abri encore de l’impact<br />

européen.<br />

Cinéma et anthropologie pactisaient donc à leur naissance au sein<br />

d’une entreprise commune: on désirait observer et conserver l’image<br />

de ce que l’on pensait être des sociétés-témoins, des étapes de la<br />

marche de l’humanité vers son achèvement présent ! Et il fallait faire<br />

vite avant que la grande circulation mise en branle par l’expansion<br />

occidentale ne vienne troubler ces formes sociales originales et<br />

supposées originelles, désormais livrées aux inévitables<br />

bouleversements provoqués par les relations avec les mondes<br />

extérieurs… Ces images auraient représenté ce qu’une pensée<br />

largement dominante, marquée par Darwin et l’évolutionnisme,<br />

considérait comme les traces des différentes étapes d’une avancée<br />

vers La civilisation dont bien entendu l’occident était l’achèvement.<br />

L’invention des premiers appareils d’enregistrement d’images animées<br />

et de son, a été immédiatement suivie par la réalisation des premiers<br />

documents filmés sur les amérindiens. En 1894, l’associé d’Edison,<br />

William Dickson enregistre au USA, avec un appareil appelé<br />

kinétographe, deux manifestations amérindiennes reconstituées,<br />

Indian War Council et Sioux Ghost Dance. En 1895, le docteur Felix-<br />

Louis Regnault, aidé par Charles Comte, ancien assistant de<br />

l’inventeur de la chrono-photographie, Jules-Etienne Marey, filme<br />

7 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 63 / 2001<br />

Cinema, photography and anthropology<br />

have been important instruments in the<br />

construction <strong>of</strong> an image <strong>of</strong> the colonised<br />

that today reveals more <strong>of</strong> an image <strong>of</strong> the<br />

coloniser and the reasons for his<br />

observations. The apparent cultural<br />

relativism <strong>of</strong> exoticism is incapable <strong>of</strong> hiding<br />

the privilege given to the centrality <strong>of</strong> the<br />

white culture.

La Croisière noire, Léon Poirier (1924 - 1925).<br />

Source: La Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique<br />

L’Homme du Niger, Baroncelli (1939).<br />

Source: La Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique<br />

une femme ouolove fabricant de la poterie lors de l’exposition<br />

ethnographique sur l’Afrique occidentale organisée au Champs de<br />

Mars à Paris. Il enregistre ensuite, dans le studio de Marey: “…trois<br />

nègres, au moment où ils s’accroupissent. L’Ouol<strong>of</strong> (n°1) et le Pule<br />

(n°2) ont les jambes obliques près de la<br />

verticale, tandis que le Diola du pays des rivières<br />

(n°3) a les jambes plus fléchies et plus près de<br />

l’horizontale…” (F-L.R., “Les attitudes du repos<br />

dans les races humaines”, Revue<br />

Encyclopédique, Paris, 1896, : 9-12). C’est une<br />

entreprise délibérée pour saisir des spécificités<br />

de comportement, comparer des attitudes<br />

physiques et constituer les bases d’une science<br />

expérimentales. En compagnie de son collègue<br />

Azoulay qui enregistre les premiers<br />

phonogrammes anthropologiques sur rouleau<br />

Edison, Regnault propose dès 1900 un véritable<br />

programme positiviste d’anthropologie visuelle.<br />

Ils affirment qu’avec le cinéma: “l’ethnographe<br />

reproduira à volonté la vie des peuples<br />

sauvages… Quand on possédera un nombre suffisant de films, on<br />

pourra par leur comparaison, concevoir des idées générales;<br />

l’ethnologie naîtra de l’ethnographie. (Regnault, 1912). Il faut<br />

cependant reconnaître que le point de vue de<br />

Regnault est plus proche de ce qui serait une<br />

éthologie humaine que de l’anthropologie.<br />

En fait la première réalisation du programme<br />

d’archivation que préconisait cet audacieux<br />

précurseur ne sera pas mise en œuvre par un<br />

spécialiste de nos disciplines mais par le banquier<br />

parisien Albert Kahn. Sensible aux<br />

transformations subies à travers la planète par<br />

l’établissement et la diffusion de la modernité,<br />

Kahn percevait la nécessité de capter avant qu’il<br />

ne soit trop tard les activités et les<br />

comportements humains sur le point de<br />

disparaître. Il fut en quelque sorte l’inventeur de<br />

ce que, après la seconde guerre mondiale, on a<br />

appelé l’ethnologie d’urgence. Kahn souhaitait<br />

mettre à la disposition des spécialistes et des<br />

hommes politiques des documents accessibles, témoignages directs<br />

des différentes formes de la réalité afin d’informer ceux que plus tard<br />

nous appellerons les décideurs et qu’alors soutenait la toute puisante<br />

idéologie du progrès, nous dirions maintenant du développement.<br />

C’est à telle fin que fut lancé un programme systématique<br />

d’enregistrement cinématographique à travers le monde entier. Cent<br />

quarante mille mètres de films ont été tournés et plus de soixante dix<br />

mille photographies autochromes réalisées, à travers trente huit pays<br />

8 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 63 / 2001

de tous les continents pour rendre compte de tous les aspects de la<br />

vie quotidienne. On cherchait à saisir, suivant les instructions du<br />

géographe Jean Bruhnes, ce qu’étaient les villes et les villages,<br />

l’environnement construit et naturel ainsi que les différentes formes<br />

d’expression religieuses et civiques. L’attention était ainsi portée par<br />

les cinématographeurs aux cadres et aux conditions de<br />

transformations généralisées dont l’époque prenait nettement<br />

conscience. L’intention se manifestait clairement de s’approprier de la<br />

diversité du monde.<br />

En Allemagne, en Angleterre des expéditions ethnographiques vont<br />

s’équiper systématiquement de matériels d’enregistrement. En 1898,<br />

entre le pacifique et l’Océan Indien, Alfred Cort Haddon, zoologue à<br />

l’origine, entreprend dans le détroit de Torrès, entre l’Australie et la<br />

Nouvelle-Guinée, un recueil systématique de tous les aspects de la<br />

vie sociale, matérielle et religieuse. Il est notamment accompagné par<br />

deux anthropologues, C.G. Seligman et W.H. Rivers, qui seront les<br />

fondateurs des chaires d’anthropologie à Cambridge et à Oxford.<br />

L’expédition rapportera les premiers films ethnographiques de<br />

terrain, enregistrés avec une caméra Lumière maniée par un<br />

opérateur pr<strong>of</strong>essionnel. En 1901, Baldwin Spencer, conseillé par<br />

Haddon, filme avec Frank Gillen chez les Aranda d’Australie chez qui<br />

ils avaient travaillé entre 1898 et 1899. Encouragé par les résultats de<br />

ces premières réalisations et convaincu par Haddon lors d’une<br />

rencontre en 1903 à Cambridge, le viennois Rudolph Pöch filmera à<br />

son tour en Nouvelle Guinée (1904-1906) et en Afrique du Sud,<br />

dans le Kalahari (1907-1909). Equipé comme ses prédécesseurs de<br />

matériel d’enregistrement sonore, Pöch filmera certains de ses<br />

enregistrements, <strong>of</strong>frant ainsi la possibilité d’une véritable<br />

synchronisation. Les images de ces extraordinaires dispositifs,<br />

permettent lorsque nous les regardons aujourd’hui d’introduire un<br />

débat sur la construction de l’expérience ethnographique et en<br />

particulier sur les dispositions réciproques de l’ethnologue et de<br />

l’ethnologisé ainsi que sur le rôle éventuel de l’instrumentation<br />

technologique.<br />

Le passage “sur le terrain” et donc l’expérimentation, faisaient du<br />

cinéma et de l’ethnographie les enfants jumeaux d’une entreprise<br />

commune de découverte, d’identification, d’appropriation et peutêtre<br />

véritablement de dévoration du monde et de ses histoires.<br />

L’enregistrement absorbe la distance matérielle de l’Autre et le réduit<br />

en images dont s’alimente mon regard. On constate que, dès son<br />

départ, le cinéma tente de saisir ce qui est l’objet même de<br />

l’ethnologie: les pratiques de l’être humain dans les relations qu’il<br />

établit et qu’il énonce avec ses semblables et avec l’environnement<br />

qui le situe et dont il dispose. Cependant, troublée par le<br />

foisonnement des images et leur incontrôlable polysémie, leur<br />

résistance à la réduction du discours savant comme à l’organisation<br />

polémique, l’ethnologie mettra un certain temps à réfléchir la<br />

9 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 63 / 2001<br />

El cine, la fotografía y la antropología han<br />

sido instrumentos importantes para la<br />

construcción de una imagen de los<br />

colonizados. El estudio de esta imagen<br />

revela hoy mucho más que la mera<br />

mentalidad del colonizador y la<br />

intencionalidad de su discurso. El aparente<br />

relativismo cultural aplicado al exotismo no<br />

logra encubrir el privilegio concedido a la<br />

centralidad blanca.

Départ de l’expédition à Colomb-<br />

Béchard, le 28 octobre 1924. La Croisière<br />

noire, Léon Poirier (1924 - 1925).<br />

Source: Les Archives du film et du dépot<br />

légal du CNC, Bois d’Arcy<br />

procédure filmique et à ne plus confondre le film comme objet<br />

signifiant avec le cinéma comme procédure langagière de découverte.<br />

Voyageurs et explorateurs rapportent de leurs pérégrinations des<br />

récits imagés où les limites entre la fiction et la réalité ne sont pas<br />

toujours évidentes. Elles s’estompent en partie sous l’effet des<br />

enthousiasmes entretenus par cette saisie apparemment sans<br />

contrainte du “sauvage vivant” transporté directement devant les yeux<br />

étonnés de l’homme blanc: celui-ci n’en finit pas de savourer une<br />

rencontre où s’affirme constamment l’efficacité et donc la supériorité<br />

de sa prise au monde, de son emprise sur le monde.<br />

On voit l’ethnologie choisir les chemins du classement et des<br />

typologies, de l’étude systématique des comportements, des rituels et<br />

des artefacts culturels considérés comme des unités objectivables et<br />

dont la combinaison fabriquait des spécificités culturelles.<br />

L’identification cinématographique étiquette en quelque sorte la<br />

différence mais pour l’ordonner dans le grand livre de l’évolution de<br />

l’humanité à travers les chapitres de sociétés qui en manifesteraient<br />

les étapes et les variantes. Les films rapportés par les ethnographes<br />

de terrain des premières décennies se veulent délibérément<br />

positivistes. Leurs effets malgré tout échappent aux intentions: les<br />

images rapportées, construites pour la plupart par des opérateurs<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essionnels, viennent s’ajouter en les renforçant, aux images<br />

d’exploration qui mêlent systématiquement dans un bouquet<br />

d’étrangeté, la flore, la faune et les êtres humains de tous les<br />

antipodes. C’est en effet, la prise de possession scientifique,<br />

apparemment opposée à la position d’une étrangeté radicale, affirme<br />

cependant et tout autant, la centralité sinon même l’unicité du point<br />

de vue des observateurs. Ainsi l’anthropocentrisme blanc ne propose<br />

que deux attitudes: la description distanciée des phases de<br />

l’humanisation ou bien l’émotion mystérieuse d’une différence<br />

irréductible. Dans le premier cas l’Autre n’est qu’une ébauche de<br />

moi-même et dans le second, l’Autre est en dehors de toute raison<br />

raisonnable, erreur dans la série évolutive des sociétés, accident ou<br />

même déchéance mystérieuse. Antagonistes visiblement, ces deux<br />

positions ne modifient en rien le privilège du seul regard dont la<br />

pertinence n’est toujours pas mise en question, celui de l’homme<br />

blanc.<br />

Victor Segalen écrivait en 1908: “L’Exotisme n’est donc pas une<br />

adaptation, n’est donc pas la compréhension parfaite d’un hors soimême<br />

qu’on étreindrait en soi, mais la perception aiguë et immédiate<br />

d’une incompréhensibilité éternelle.” (V.S., Essai sur l’exotisme, Paris,<br />

Le Livre de Poche, 4042, 1986, :38). Il est vrai qu’à cette définition<br />

essentiellement négative d’une altérité irrémédiable, Segalen ajoutait<br />

une mise en question de la centralité européenne: ce décalage dans<br />

l’espace et dans le temps qui introduit à la notion du différent, à la<br />

perception du divers, cette distanciation devrait être ressentie par<br />

quiconque serait susceptible d’éprouver de la curiosité. Segalen était<br />

bien conscient que sa définition “noble” de l’exotisme était en entière<br />

10 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 63 / 2001

opposition avec l’option dominante dont étaient (sont?) porteurs les<br />

touristes, les coloniaux et les écrivains du voyage. Pierre Loti, Claude<br />

Farrère, Paul Claudel, l’agence Cook, le colon et le fonctionnaire<br />

colonial sont ceux qu’il qualifie de “‘proxénètes de la sensation du<br />

divers”. Ce sont en effet les fournisseurs en tous genre de<br />

“chinoiseries”, de singularités, de couleurs et d’odeurs qui vont<br />

rehausser le quotidien de l’environnement français, réveiller les sens<br />

endormis avec des parfums et des sensations nouvelles en marge de<br />

l’ordre fondamental. A l’encontre de cela, Segalen portait l’attention<br />

sur les conditions et les effets d’une “rencontre” à laquelle tous les<br />

partenaires seraient susceptibles de réagir. En ce sens et sans<br />

proposer une discussion critique de sa conception de<br />

l’individualisme, je voulais souligner le caractère précurseur d’une<br />

position qui donnait place à une prise en compte des circonstances,<br />

des modalités et des effets d’une observation partagée. C’est qu’en<br />

effet, une telle proposition <strong>of</strong>frait une issue alternative au positivisme<br />

des ethnographes et des cinéastes qui parfois tenteront malgré tout et<br />

à leur façon, d’entrer en lutte contre les marchands de pacotilles<br />

tropicales.<br />

Il convient donc de s’interroger sur les raisons qui ont entretenu ce<br />

point de vue et de discerner pourquoi et comment l’exotisme des<br />

commerçants d’illusion a été remplacé par le positivisme<br />

ethnographique et non pas par une reconnaissance partagée de la<br />

différence dont le développement ne se fera jour qu’après la seconde<br />

guerre mondiale, à partir notamment des mouvements<br />

indépendantistes.<br />

C’est dans cette perspective qu’un film comme La Croisière noire<br />

prend toute son importance car il est de ceux qui, en France ont fait<br />

charnière en introduisant clairement une coupure entre la découverte<br />

étonnée de l’Autre et la nécessité imposée par la force de l’ordre<br />

métropolitain. Mais revenons un peu sur cette notion d’exotisme<br />

pour rappeler ses acceptions les plus courantes.<br />

De façon apparemment idéale, l’exotisme est une forme de<br />

relativisme culturel qui va situer une civilisation par rapport à une<br />

autre mais dont on s’aperçoit très vite qu’il instaure une position<br />

d’inégalité. C’est que le sens de la valorisation n’est établi que par<br />

rapport à un pôle privilégié de la relation et c’est ce pôle unique qui<br />

généralement a l’initiative de la relation.<br />

Ainsi peut-on sans aucun doute considérer l’exotisme comme une<br />

position de la différence <strong>of</strong>frant à voir le monde extérieur<br />

exclusivement à partir d’une centralité blanche et, pendant<br />

longtemps, essentiellement européenne. Cette position convient<br />

clairement aux expansionnismes coloniaux qui pourront l’utiliser<br />

mais il faut bien convenir qu’elle ne les implique pas nécessairement:<br />

elle peut même s’y trouver opposée dans son besoin de maintenir la<br />

distance, de jouer sur l’irréductible différence, de constituer une<br />

esthétique de l’incommunicable.<br />

11 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 63 / 2001

La mystique du désert dans La llamada de África,<br />

César Fernández Ardavín (1952).<br />

Source: <strong>Film</strong>oteca Española, Madrid<br />

Le voyageur, livré à ses impressions, à ses sentiments, ajoute le<br />

piment de l’exotisme, franchissant les cadres de l’esthétisme mais<br />

aussi de la morale, pour réanimer les habitudes d’une européanité<br />

fatiguée ou trop industrielle, mercantile et déjà productiviste. Segalen<br />

réclamait de l’Exote, du voyageur averti, qu’il se laisse assaillir et<br />

donc “troubler” par le milieu qu’il découvre (“L’attitude… ne pourra<br />

donc pas être le je qui ressent… C’est le tu qui dominera.” V.S., Essai<br />

sur l’exotisme, Paris, Le Livre de Poche, 4042, 1986, :35).<br />

Pierre Loti par contre libère le principe d’un bon plaisir<br />

que la mort de dieu, largement proclamée à la fin du<br />

XIXème siècle, rend possible et <strong>of</strong>fre à la jouissance.<br />

L’impression du sujet devient alors prépondérante et c’est<br />

à travers son expérience la plus subjective qu’il va<br />

éprouver la nature de l’Autre, ressentir l’Autre. Malgré et<br />

peut-être même à cause de l’investissement personnel de<br />

l’observateur qui sera un observateur-participant<br />

exemplaire, véritable modèle pour une certaine ethnologie<br />

à venir, Loti, au-delà des séductions ressenties et des<br />

travestissements acceptés, retrouvera toujours l’ultime,<br />

l’insurmontable différence: “Je sens mes pensés aussi loin<br />

des leurs que des conceptions changeantes d’un oiseau ou des<br />

rêveries d’un singe.” (Madame Chrysanthème, 1887, Paris, 1914,<br />

:266). Il n’est pas sans intérêt qu’au moment ou Loti retrouve la<br />

différence à la frontière ultime des séductions, il la compare à celle<br />

qui le distancie des oiseaux et des singes, identifiant ainsi l’Autre aux<br />

espèces animales. On voit bien là ce qui distingue l’Exote de Segalen,<br />

avide de se trouver en l’Autre, du voyageurs avide de sensations et<br />

d’expériences nouvelles mais qui ne le rapprocheront jamais, bien au<br />

contraire, des êtres singuliers et pr<strong>of</strong>ondément barbares qui peuplent<br />

les décors de ses aventures lointaines.<br />

L’exotisme reconnaît bien qu’il y a de la différence en ce monde mais<br />

elle risquerait de nous absorber si nous y trouvions trop de raisons<br />

de ne pas nous aimer nous-mêmes: que ferions-nous alors en nous<br />

identifiant à l’Autre sinon paradoxalement nier la différence qui<br />

renvoie nécessairement à notre irrémédiable nature d’être civilisé.<br />

L’exotisme est une tentation impossible, un désir sans cesse inassouvi<br />

puisque au-delà des appels les plus séducteurs de l’étrangeté, et à<br />

moins de ne pas nous considérer nous-mêmes comme des êtres<br />

humains achevés, nous y retrouverions les traces dangereuses de la<br />

nature dans ce qu’elle a de plus irraisonnable, de plus sauvage.<br />

Et finalement Loti accomplira le passage de la différence exotique à la<br />

mise en demeure coloniale où l’Autre n’est plus reconnu dans son<br />

autonomie et devient pour le Blanc, seul vrai sujet de l’histoire, un<br />

simple instrument dans la détermination de soi. Les femmes à cet<br />

égard seront l’expression privilégiée de cette objectivation de l’autre<br />

et de cette véritable appropriation dont l’invasion coloniale<br />

accomplira en grand la réalisation et que le développement de la<br />

photographie puis du cinéma concrétiseront également.<br />

12 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 63 / 2001

L’Autre, réduit en image, sera transporté et consommé sur place par<br />

le métropolitain. En tout état de cause les limites et les périls de<br />

l’attrait exotique apparaissent très clairement, comme le remarque<br />

justement Tzetan Todorov (Nous et les Autres. La réflexion française sur<br />

la diversité humaine, Paris, Seuil, 1989, :347-355) lorsque la sexualité<br />

met en présence l’homme blanc avec la véritable nature sauvage de<br />

l’Autre. Ce sera bien entendu la femme noire qui jouera ce rôle de la<br />

tentatrice démoniaque mais, heureusement, l’imprudent aventurier<br />

du Roman d’un Spahi arrivera à se détacher d’un entraînement fatal:<br />

alors il aura “retrouvé sa dignité d’homme blanc, souillé par le<br />

contact avec cette chair noire” (P. Loti, Le Roman d’un Spahi, [199—<br />

881], Presses Pocket, 1987, :142).<br />

Je crois qu’il n’est pas déraisonnable à ce point de rappeler qu’à la<br />

même époque Freud développait ses thèses sur la sexualité,<br />

l’interprétation du rêve et les formulations de l’inconscient. Il<br />

s’agissait là également d’une exploration aux antipodes de la raison<br />

contrôlée, il s’agissait également de fantasmes et d’appréciation de<br />

stades dans le développement de la personne sinon des sociétés. La<br />

nature en l’homme, l’Autre en soi, sont des thématiques<br />

fondamentales de la psychanalyse qui cherchera à mettre bon ordre,<br />

en les incluant et donc en les assimilant, aux pulsions contraires à un<br />

certain équilibre. Les reconnaître, dépister leurs parcours et leurs<br />

raisons ne signifie pas, pour nos explorateurs des pr<strong>of</strong>ondeurs de<br />

l’âme, en accepter les effets mais au contraire en réduire les<br />

désordres, en soumettre les rebellions à l’identification sociale<br />

dominante. Pour cela, il faudra imposer la réduction du réel à son<br />

expression, de l’expérience à son évocation par le discours. La parole<br />

va se confondre avec ce dont elle parle.<br />

La psychiatrie, la psychanalyse et les roues des magnifiques<br />

autochenilles Citroën vont servir à mettre de l’ordre dans l’abandon<br />

et l’éclatement des personnes aliénées comme des populations<br />

sauvages ou déchues. Le sable mortifère du Sahara, les forêts<br />

inconnues du Cameroun seront “pénétrés”, “dévoilés” et vaincus par<br />

le chemin de fer et l’automobile. Alors l’infantilisme ou la sauvagerie<br />

des nègres seront contrôlés et utilisés: ils accéderont enfin au statut<br />

d’indigènes, intégrés au processus général de la production,<br />

instrumentalisés, provisoirement ou non, au niveau de base de cette<br />

production. Alors le cinéma ne pourra plus se contenter de montrer<br />

des curiosités mais devra surtout les confronter à un projet de<br />

cohérence.<br />

Le cinéma envahit tous les secteurs de la création: l’art, l’archéologie,<br />

la littérature s’abandonnent à tous les voyages imaginables. Les<br />

caméras dévoilent Bornéo, la Nouvelle-Guinée, l’Afrique, les<br />

Philippines. Citroën finance l’Expédition Citroën Centre-Afrique dont<br />

l’odyssée sera racontée dans un film fameux réalisé par un cinéaste<br />

déjà bien connu, Léon Poirier.<br />

L’expédition, dirigée par Georges-Marie Haardt et Louis Audoin-<br />

Dubreuil, devait relier pour la première fois “l’Algérie à Madagascar<br />

13 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 63 / 2001

en autochenilles”. Partie de 28 octobre 1924 de Colomb-Béchard, elle<br />

arrivait le 26 juin 1925 à Tananarive. Poirier, <strong>of</strong>ficiellement “chargé<br />

de la documentation cinématographique”, avait comme “adjoint”<br />

pour la prise de vue Specht, l’un des opérateurs du film célèbrissime<br />

de Feyder, L’Atlantide (1921). Lui-même d’ailleurs avait été candidat à<br />

la réalisation de cette image de l’œuvre fameuse de Pierre Benoît.<br />

La sortie du film La Croisière noire en 1926 eut un succès retentissant<br />

où, aux fiertés cocardières françaises devant les images d’un immense<br />

Empire colonial, se mêlait le sentiment de découvrir des civilisations<br />

déchues n’attendant que l’aide généreuse de la métropole pour<br />

accéder au monde fraternel du progrès universel ! La première<br />

version, muette, sera sonorisée en 1933, accentuant encore par la<br />

musique et le commentaire de triomphalisme colonial du film et son<br />

anglophonie à peine masquée. Le développement des liens entre les<br />

territoires dispersés de la colonisation, l’établissement d’une unité de<br />

gestion et d’une unité de pensée référées aux trois couleurs du<br />

drapeau national, voilà ce qu’expriment les images de La Croisière<br />

noire. La construction du film enchaîne systématiquement les<br />

séquences de circulation, les danses et les chasses. Les images sont<br />

belles et appliquées, aussi lourdes dans cette esthétique que la<br />

pesanteur efficace des autochenilles sur le sable du désert. Les<br />

cadrages sont déjà ceux de Morocco (J. von Sternberg, avec Marlène<br />

Dietrich et Gary Cooper, 1930), de Pépé le Mocco (Julien Duvivier,<br />

avec Jean Gabin, Mireille Balin, Fréhel, Dalio, 1937) et des<br />

innombrables films de fiction qui feront du désert le décor idéal<br />

traversé par une aventure centrale, décisive, celle de l’homme blanc<br />

tout à ses sentiments, ses découvertes et ses passions.<br />

Il n’y a pas d’autre sujet, direct ou indirect, documentaire ou<br />

fictionnel, que celui qui porte le regard et désigne dans ce<br />

mouvement ce qui peut légitimement atteindre à la dignité du<br />

remarquable. Les opérateurs de ces films vont chercher des détails<br />

incongrus qui viendront au devant de la scène, ordonnant ainsi des<br />

significations spécieuses et incontrôlables dans l’instant d’une<br />

projection. Les distances seront escamotées entre les espèces<br />

animales, végétales et humaines, montrées, montées côte à côte en<br />

raccourcis saisissants. La caméra ne se déplace pas, elle tourne sur<br />

elle-même, épinglant, comme l’entomologiste, son objet sans défense<br />

sous la lumière crue des projecteurs.<br />

La circulation automobile elle-même montre bien l’efficacité de la<br />

technologie, sa rigueur et le caractère inéluctable de son déploiement<br />

qui fabrique de l’unité, fermement administrée par des hommes hors<br />

pairs. En contraste, les danses font voir le flou, l’étrangeté, la<br />

diversité, la discontinuité des populations rencontrées: la danse et le<br />

chant sont d’ailleurs les seules qualités reconnues véritablement à ces<br />

sociétés. L’anarchie, l’archaïsme ou la déchéance des peuples<br />

répondent à la violence générale de la nature. Heureusement la<br />

puissance coloniale apportera les instruments d’une véritable maîtrise<br />

et, comme l’écrivent très clairement les chefs de l’expédition dont les<br />

14 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 63 / 2001

exploits nous sont montrés en image: “Nos voitures surgissant de cet<br />

horizon maudit et toujours plein de menaces, cela veut dire pour eux<br />

que là aussi, la France veille. C’est la fin d’un cauchemar, l’assurance<br />

définitive d’une paix féconde et désormais sans éclipse” (G.M. Haardt<br />

et L. Audouin-Dubreuil, Le Raid Citroën. La première traversée du<br />

Sahara en Automobile, de Touggourt à Tombouctou par l’Atlantide, préf.<br />

A. Citroën, Paris, Plon, 1924, :109). Seuls échappent au dédain<br />

général à l’égard des “peuplades” rencontrées, les Touaregs, mais<br />

chacun sait qu’ils sont blancs et les Mangbetou, descendants, qu’on<br />

trouve un peu dégénérés malgré tout, des anciens Egyptiens et donc<br />

fort éloignés (toujours du point de vue de nos héros en chenilles) des<br />

populations nègres alentour ! Il est en tout cas bien révélateur que<br />

Pierre Leprohon dans un ouvrage sur l’exotisme et le cinéma,<br />

considère que dans ce film: “Des scènes curieuses de moeurs nègres,<br />

des images de bêtes en pleine liberté, des troupeaux fuyant devant<br />

l’incendie, enfin les fameuses “négresses à plateau”, constituaient<br />

autant d’éléments d’intérêt parfaitement mis en valeur.” (L’exotisme et<br />

le Cinéma, Paris, J. Susse, 1945, :69). Cet AUTANT donne bien le<br />

sens général et la proximité affirmée sinon la parenté de ces êtres<br />

tout juste humains avec la nature sinon les animaux !<br />

Le film de Léon Poirier est un véritable poteau indicateur des<br />

relations s’instaurant entre ce que nous appellerions aujourd’hui le<br />

Nord et le Sud. Les images désormais ne pourront être que de deux<br />

ordres: soit la vision de sociétés plus ou moins proches de la<br />

sauvagerie naturelle (l’exemple des pygmées est particulièrement<br />

éclairant dont on dit dans le film qu’ils sont l’état le plus primitif de<br />

la nature humaine mais que néanmoins ces “étranges petits gnomes<br />

sont propres…”), soit la démonstration des transformations<br />

qu’apporte la colonisation; routes, chemins de fer, écoles, hôpitaux,<br />

barrages et ordre paisible sous sa forme militarisée.<br />

Il n’y avait plus de place pour un cinéma ethnologique qui aurait<br />

tenté de rendre compte de la dynamique et de l’autonomie d’une<br />

société autochtone en même temps que des modalités réelles du<br />

changement. La colonisation en état de marche ne pouvait accepter<br />

des images que dans la mesure où elles contribuaient à la<br />

justification de cette éventuelle transition de la sauvagerie ou de la<br />

simplicité primitives à l’instrumentalisation indigène. On était passé<br />

du Continent Mystérieux (Paul Castelnau, 1924) relatant le premier<br />

raid Citroën à travers le Sahara à cette Croisière noire qui devait ouvrir<br />

la voie à la fois au développement économique dont Baroncelli se<br />

fera le chantre (L’homme du Niger, 1939) mais aussi au tourisme dont<br />

se préoccupera, après Citroën, le baron Gourgaud. “Le vrai visage de<br />

l’Afrique” que ce dernier voulait montrer dans son film Chez les<br />

Buveurs de Sang (1930-31) n’est qu’une sorte de patchwork des<br />

splendeurs “naturelles” de l’Afrique centrale où les ressources<br />

cynégétiques et les paysages impressionnants sont des curiosités au<br />

même titre que les Masaï et les Pygmées. On retiendra cependant que<br />

le titre du film joue sur le frisson d’horreur et d’inquiétude qui doit<br />

15 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 63 / 2001

provoquer l’attention et, surtout, marquer la différence, la distance<br />

avec “la” civilisation. En ce sens, alors que l’exposition sur l’Afrique<br />

Occidentale de 1895 à Paris avait provoqué l’intérêt du médecin<br />

anthropologue Félix-Louis Regnault pour un enregistrement à visée<br />

ethnographique, ne fera qu’entraîner des dérives folklorisantes et<br />

exotisantes, attirant l’attention du public par la mise en scène de la<br />

distance, de l’étrangeté et du mystère, largement exploités déjà dans<br />

les films de fiction et utilisés par des réalisateurs comme Yves Allégret<br />

(Ténériffe; 1932) ou René Clément (Au Seuil de l’Islam, 1936 ; L’Arabie<br />

interdite, 1937).<br />

En fait, dans la France d’entre deux guerres, les seuls films réalisés<br />

par des ethnologues seront celui du père O’Reilly en Mélanésie<br />

(Popoko, île sauvage, 1931) et ceux de Marcel Griaule, pour qui le<br />

cinéma est essentiellement “un auxiliaire au même titre, dira-t-il, que<br />

tout autre méthode d’enseignement.” Il devra se soumettre<br />

néanmoins aux conditions de production et de diffusion du cinéma<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficiel. Ses deux films achevés, tournés chez les Dogons, Au pays des<br />

Dogons (1935) et Sous les Masques Noirs (1938) resteront victimes<br />

dans la forme et le ton de la déclamation du commentaire, du<br />

triomphalisme des documentaires coloniaux. Néanmoins le texte du<br />

commentaire lui-même guidera un montage qui tentera d’écarter les<br />

jugements de valeur au pr<strong>of</strong>it d’un essai d’objectivité descriptive.<br />

Malgré tout, l’intonation donnée au texte par le speaker nuancera<br />

l’énoncé d’une sorte de distanciation parfois humoristique et donc<br />

minorisante pour le Dogons. La dépendance à l’égard des modes de<br />

réalisations pr<strong>of</strong>essionnels empêchera longtemps encore la réalisation<br />

de films contribuant au développement même de la discipline, quels<br />

que soient ses errements et ses hésitations. On peut s’interroger sur la<br />

signification de cette dépendance qui sans doute en masque une<br />

autre plus grave et qui serait d’ordre idéologique et politique.<br />

L’allégement des matériels et la décolonisation seront certainement<br />

des facteurs essentiels pour une progressive prise en compte des<br />

modalités de la rencontre et éventuellement de l’échange des regards<br />

et enfin d’un éventuel partage des questions, au-delà d’une seule<br />

description positiviste. On pourrait dire cependant, que par un<br />

étrange retour des choses, la dépendance s’est aujourd’hui renouvelée<br />

en <strong>of</strong>frant à des productions longtemps restées confidentielles,<br />

l’ouverture paradoxale du petit écran. Nous sommes aujourd’hui et à<br />

nouveau, confrontés aux exigences d’un véritable néo-exotisme<br />

destiné à reconduire l’autre de tous les tiers-mondes, de tous les<br />

quarts-mondes, dans une différence irréductible, dans ce que sa<br />

misère révélerait d’une incurable incapacité à l’ordre, à cet ordre dont<br />

le FMI serait le garant et en dehors duquel il n’y aurait que<br />

barbarie… On voit bien là que la réflexion n’est pas achevée et que la<br />

descendance de Pierre Loti est peut-être aujourd’hui plus nombreuse<br />

que celle de Segalen…<br />

16 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 63 / 2001

Hygienic Reform in the French Colonial<br />

<strong>Film</strong> Archive<br />

Peter J. Bloom<br />

A thousand and one nights but only one cure<br />

There was a time when Mohamed ben Chegir was as strong as a lion,<br />

as fast as a greyhound, as agile as a panther. He possessed more<br />

stamina than the best camels and was as handsome as a summer’s<br />

day. But something happened. A cold sore appeared on his lip.<br />

This text serves as the opening narration to Conte de la mille et une<br />

nuits (The Tale <strong>of</strong> a Thousand and One Nights) (1929, illustrated by<br />

Albert Mourlan), a ten-minute animated educational film about<br />

syphilis produced by Jean Bénoît-Lévy. This film was part <strong>of</strong> a vast<br />

archive <strong>of</strong> short subject, French educational films that circulated in<br />

France and North Africa during the interwar period. In this paper I<br />

examine the interlocking nature <strong>of</strong> French educational cinema and<br />

hygienic reform. I address how French interwar educational<br />

documentary cinema presents hygienic reform as a vision based on<br />

the reterritorialization <strong>of</strong> microbiological and geographic space in<br />

France and the French colonies.<br />

Conte de la mille et une nuits opposes Mohamed’s natural, healthful<br />

state (emphasised with animated drawings <strong>of</strong> a lion, a greyhound,<br />

and a panther) to a present state <strong>of</strong> physical decline. Some years<br />

later, an automobile arrives bearing French doctors, nurses, and a<br />

free movie. In the local cinema hall, the curtain unveils the film’s<br />

opening title: Les Maladies vénériennes [Venereal Diseases]. The first<br />

shot <strong>of</strong> this film-within-a-film reveals a photographic image <strong>of</strong> a<br />

distorted Arab face with the intertitle, “Syphilis can lead to insanity,”<br />

then another photograph <strong>of</strong> a blind Arab man gesturing for alms<br />

with the intertitle, “Syphilis can lead to blindness.” A quick<br />

succession <strong>of</strong> photographs appears: a medium shot <strong>of</strong> a child born<br />

with syphilis, a close-up <strong>of</strong> syphilitic lesions on a man’s back, and an<br />

extreme close-up <strong>of</strong> a cold sore. The last words <strong>of</strong> the film-within-afilm<br />

are an appeal to those in Mohamed’s predicament: “If you<br />

presently have, or ever have had these seemingly inconsequential<br />

lesions, even if they did not hurt, see the doctor right away. The<br />

doctor – and the doctor alone – is the only one who can cure you.”<br />

The doctor who diagnoses and treats the patient is the irreproachable<br />

symbol <strong>of</strong> French colonial humanism. Conte de la mille et une nuits<br />

was widely circulated in France and North Africa during the interwar<br />

period, and was eventually set to French and Arabic narration tracks<br />

some years after it was first released. The Orientalist parable <strong>of</strong> A<br />

thousand and one nights drew on the powerfully charged Contes arabes,<br />

and Conte de la mille et une nuits demonstrates the hygienic revenge <strong>of</strong><br />

17 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 63 / 2001

La réforme hygiénique (mise à l’avant par la<br />

propagande française dans la période de<br />

l’entre-deux guerres), comme métaphore des<br />

bienfaits de la colonisation. À partir de<br />

quelques courts métrages didactiques<br />

mettant en garde contre les maladies<br />

vénériennes et vantant les vertus de la<br />

médecine moderne, l’auteur analyse la mise<br />

en place du discours colonialiste. Le discours<br />

hygiéniste et l’aventure coloniale font bon<br />

ménage. Les microbes invisibles et la<br />

géographie sont étroitement liés.<br />

this well-known Arab fable. French medical agency becomes not<br />

merely the sole cure for syphilis, but it is the only way that the<br />

fantasy <strong>of</strong> “A thousand and one nights” may live on as an imagined<br />

state.<br />

When Mohamed understands that the cold sore is no mere “bobo”<br />

and walks over to the village dispensary, the film becomes the hope<br />

that we may all return to a Rousseauesque state <strong>of</strong> nature,<br />

uninhibited by the paralysing effects <strong>of</strong> contagious diseases produced<br />

by “civilised life.” The arrival <strong>of</strong> French public health campaigns<br />

implies a modernist regenerative mythology. The appearance <strong>of</strong> the<br />

automobile, the screening <strong>of</strong> an educational film, and the<br />

incontrovertible authority <strong>of</strong> French medical expertise all contribute<br />

to the spectacle <strong>of</strong> modernity, which promises a form <strong>of</strong> spiritual and<br />

social renewal as the “restoration” <strong>of</strong> a simpler life.<br />

French interwar documentary cinema also established a vital link<br />

between microbiological agents and geographic landscapes. Popular<br />

demonstrations <strong>of</strong> the all-powerful microbe pioneered by the Pasteur<br />

Institute before the First World War contributed to an emerging<br />

visual culture <strong>of</strong> magnification and spectacle. These demonstrations<br />

became emblems <strong>of</strong> a scientific diagnosis beyond question, justifying<br />

a widening geographic theatre <strong>of</strong> curative action both in France and<br />

the colonies.<br />

Optics-<strong>of</strong>-scale<br />

In an even shorter short-subject film entitled Trypansoma Gambiense:<br />

Agent de la maladie du sommeil [Trypansoma Gambiense: The Agent <strong>of</strong><br />

Sleeping Sickness] (1924), produced by Pathé Consortium Cinéma, an<br />

optics-<strong>of</strong>-scale demonstrates the effects and causes <strong>of</strong> sleeping<br />

sickness. This four-minute film is composed <strong>of</strong> three basic levels <strong>of</strong><br />

magnification: it begins with a medium shot <strong>of</strong> an African “patient,”<br />

followed by an extreme close-up <strong>of</strong> the tsé-tsé fly, and concludes with<br />

a microcinematic illustration <strong>of</strong> sleeping sickness (also known as<br />

trypanosomiases) at the cellular level, where it has infected a sample<br />

<strong>of</strong> rat’s blood.<br />

Within these three levels <strong>of</strong> magnification, sleeping sickness is<br />

diagnosed as a set <strong>of</strong> typological associations. The opening shot<br />

establishes an African context for sleeping sickness. While nothing<br />

seems obviously wrong with an African man breathing heavily<br />

outside <strong>of</strong> a hut, the intertitle informs us that this man is afflicted<br />

with sleeping sickness. His medical condition is invisible, yet can be<br />

diagnosed and even magnified. Dangling on the end <strong>of</strong> a needle, the<br />

tsé-tsé fly is presented as a still image <strong>of</strong> glossina palpalis, a generic<br />

entomological specimen. The film cuts from this still <strong>of</strong> the dangling<br />

fly, to a motionless fly, superimposed on a white backdrop with its<br />

antennae, sensor, proboscis, and stinger labelled as part <strong>of</strong> an<br />

anatomical demonstration.<br />

The camera then moves into the cellular universe <strong>of</strong> the microscopic<br />

sample. At first, normal circular blood cells appear, but a further<br />

18 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 63 / 2001

magnified view detects the telltale worm-like strands <strong>of</strong> the disease,<br />

trypansoma gambiense. Upon contact with the parasites, normal<br />

circular-shaped blood cells mutate into octagonal-shaped cells,<br />

recombining in a quilted pattern.<br />

This startling microcinematographic demonstration in the final<br />

segment <strong>of</strong> this film by Jean Comandon, later used to dramatise the<br />

effects <strong>of</strong> a vampire bite in Jean Panlevé’s short surrealist film Le<br />

Vampire [The Vampire] (1939), was excerpted in a number <strong>of</strong> other<br />

circulating educational hygiene films <strong>of</strong> the period. Trypansoma<br />

Gambiense: Agent de la maladie du sommeil itself was a composite <strong>of</strong><br />

sequences from other educational films <strong>of</strong> the period since, during<br />

the interwar period, film sequences from a stock <strong>of</strong> educational<br />

short-subject films were <strong>of</strong>ten edited together to create new<br />

compilation films. Despite the frequent reappearance <strong>of</strong> the same<br />

sequences in different educational films, they remained convincing<br />

pedagogical demonstrations. The patchwork quality <strong>of</strong> these<br />

educational demonstrations created the effect <strong>of</strong> authenticity in spite<br />

<strong>of</strong> inconsistencies between disjointed visual sequences and the<br />

intertitles.<br />

Trypansoma Gambiense’s composite nature is revealed by such internal<br />

inconsistencies. For example, one wonders why a sample <strong>of</strong><br />

trypansoma gambiense is shown infecting a sample <strong>of</strong> rat’s blood<br />

rather than the African man who appears in the frame. And since<br />

when is heavy breathing considered a symptom <strong>of</strong> sleeping sickness?<br />

These discrepancies form part <strong>of</strong> a deeper web that points to<br />

conditions <strong>of</strong> production and circulation, with each segment <strong>of</strong> the<br />

film referring to a longer cycle <strong>of</strong> film subjects, and suggests some <strong>of</strong><br />

the ways in which these were combined and presented to the French<br />

and African public.<br />

The opening sequence, with the African man sitting outside <strong>of</strong> a hut,<br />

was excerpted from Le Continent mystérieux [The Mysterious Continent]<br />

(1924) that appeared in theatres in twelve brief instalments as a<br />

popularised French colonial geography lesson. <strong>Film</strong>ed by the noted<br />

geographer Paul Castelnau, Le Continent mystérieux was produced<br />

from footage shot during the first film expedition sponsored by the<br />

Citroën automobile company. Its release also served as advance<br />

publicity for the most famous <strong>of</strong> the Citroën-sponsored expeditions:<br />

La Crosière noire [The Black Journey], which premiered as a popular<br />

feature documentary film and was also a centrepiece for an<br />

important Parisian exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in<br />

1925. Le Continent mystérieux presents various locations across the<br />

Sahara desert in Algeria, Mali, and Guinea. The shot that appears in<br />