Téléchargez le livret intégral en format PDF ... - Abeille Musique

Téléchargez le livret intégral en format PDF ... - Abeille Musique

Téléchargez le livret intégral en format PDF ... - Abeille Musique

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

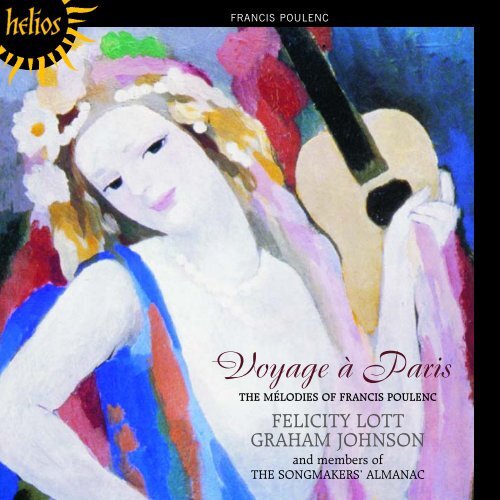

FRANCIS POULENC<br />

Voyage à Paris<br />

THE MÉLODIES OF FRANCIS POULENC<br />

FELICITY LOTT<br />

GRAHAM JOHNSON<br />

and members of<br />

THE SONGMAKERS’ ALMANAC

‘Anything that concerns Paris I approach with tears in my eyes<br />

and my head full of music’ FRANCIS POULENC (1899–1963)<br />

N<br />

O COMPOSER was ever so in love with a metropolis as<br />

Francis Pou<strong>le</strong>nc was with Paris. This ultra-sophisticate,<br />

easily bored and depressed, detested the inevitab<strong>le</strong> exi<strong>le</strong><br />

from his beloved home town during concert tours in the Fr<strong>en</strong>ch<br />

regions. At the <strong>en</strong>d of these provincial recitals, Voyage à Paris<br />

was performed as a rather malicious <strong>en</strong>core: it is an<br />

unashamed paean of joy (and relief) at the prospect of re<strong>en</strong>tering<br />

the urban melting-pot. Pou<strong>le</strong>nc wrote in his Journal de<br />

mes mélodies: ‘To any who know me it will seem quite natural<br />

that I should op<strong>en</strong> my mouth like a carp to snap up the<br />

deliciously stupid lines of Voyage à Paris.’ As a te<strong>en</strong>ager<br />

Pou<strong>le</strong>nc had only slightly known the poet Guillaume Apollinaire<br />

(1880–1918), but ev<strong>en</strong> on hearing Apollinaire read his poems<br />

aloud, the young composer recognized a kindred spirit.<br />

Apollinaire was Polish–Italian by birth (Kostrowitsky was his<br />

real name) but his love for Paris had all the int<strong>en</strong>sity of the<br />

convert. Montparnasse is a beguiling and nostalgic evocation<br />

of south Paris and its magic as felt by the wide-eyed and<br />

inexperi<strong>en</strong>ced appr<strong>en</strong>tice poet. It took Pou<strong>le</strong>nc some four years<br />

to piece together his setting of these words, but the seam<strong>le</strong>ss<br />

unfolding of the music as it follows the affectionate<br />

meanderings of the poem is a triumph: he finds tune and<br />

harmony to suggest not only the longing for vanished times of<br />

the poet’s youth in Montparnasse, but also Apollinaire’s rueful<br />

smi<strong>le</strong> at his gauche, younger self—un peu bête et trop blond.<br />

Hyde Park transfers the sc<strong>en</strong>e to London. It makes these<br />

twinned pieces a type of ‘Ta<strong>le</strong> of Two Cities’ in song, although,<br />

as far as Hyde Park is concerned, Pou<strong>le</strong>nc knew he had done<br />

far, far better things. ‘It is nothing more than a trampoline<br />

song’, he wrote, meaning that he int<strong>en</strong>ded it to be a quick,<br />

effective springboard into a more substantial mélodie. The<br />

vignette marked fol<strong>le</strong>m<strong>en</strong>t vite et furtif depicts the crazy<br />

preachers of Hyde Park Corner, reproving nannies airing their<br />

charges, and the pea souper fog prev<strong>en</strong>ting policem<strong>en</strong> from<br />

seeing <strong>en</strong>ough to press theirs. Red cyclops’ eyes in the mist are<br />

nothing more mythological th<strong>en</strong> the glowing of tobacco pipes.<br />

Racy humour in both Pou<strong>le</strong>nc and Apollinaire is always<br />

capab<strong>le</strong> of sudd<strong>en</strong>ly yielding to the deepest emotion. The word<br />

‘b<strong>le</strong>u’ is slang for a young soldier, and the tit<strong>le</strong> of the song<br />

B<strong>le</strong>uet (which literally means ‘cornflower’) is a t<strong>en</strong>der<br />

diminutive. The boy soldier is about to die; five o’clock is the<br />

time to <strong>le</strong>ave the tr<strong>en</strong>ches and face the <strong>en</strong>emy fire. But there<br />

is no exaggerated heroism or patriotism in this song. Pou<strong>le</strong>nc<br />

wrote: ‘Humility, whether it concerns prayer or the sacrifice of<br />

a life is what touches me most … the soul flies away after a<br />

long, last look at “la douceur d’autrefois”.’ It is Pou<strong>le</strong>nc’s only<br />

mélodie for t<strong>en</strong>or, and the voice needs to be that of a Cu<strong>en</strong>od<br />

rather than a Gigli; in describing the young man of tw<strong>en</strong>ty, the<br />

sad waste of his life, and that long last look, the narrator’s<br />

voice should have a special and ethereal timbre. Apollinaire<br />

wrote the poem in 1917, a year or so before he himself died as<br />

a long-term result of his war wounds.<br />

Voyage is also a moving va<strong>le</strong>diction, and its words too<br />

are set in a wartime context. Who but Pou<strong>le</strong>nc could have<br />

deciphered this Calligramme (Apollinaire’s name for his<br />

experim<strong>en</strong>ts in pictorial typography—and this one is<br />

especially puzzling in lay-out) and produced a song of such<br />

flowing lucidity? There is an atmosphere here of resigned<br />

acceptance—partings in war are oft<strong>en</strong> perman<strong>en</strong>t farewells;<br />

the journey of Dante through the infernal realms knows no<br />

return. As in Montparnasse we are aware of an almost<br />

chemical reaction which takes place wh<strong>en</strong> Pou<strong>le</strong>nc’s music<br />

meets the so-cal<strong>le</strong>d surrealist poetry of Apollinaire and of Paul<br />

Éluard (1895–1952). Pou<strong>le</strong>nc wrote: ‘If on my tomb were<br />

inscribed: here lies Francis Pou<strong>le</strong>nc, the musician of<br />

Apollinaire and Éluard, I would consider this to be my finest<br />

2

tit<strong>le</strong> to fame.’ With his innate understanding of their work, the<br />

composer illuminates the sometimes inscrutab<strong>le</strong> poetry which<br />

in turn, through its force and dignity, <strong>en</strong>sures that his lyricism<br />

never topp<strong>le</strong>s into s<strong>en</strong>tim<strong>en</strong>tality. It is as if a wonderful bargain<br />

has be<strong>en</strong> struck betwe<strong>en</strong> head and heart, betwe<strong>en</strong> modern use<br />

of language and the old-fashioned power of melody.<br />

Hôtel takes us back to Apollinaire’s Montparnasse, and<br />

Pou<strong>le</strong>nc’s. Just after the First World War the area was the home<br />

of Picasso and Derain, of Gris and Modigliani. The composer, a<br />

connoisseur and lover of painting all his life, was excited by the<br />

avant-garde buzz of the Montparnasse of his youth. But Hôtel<br />

is not about creativity. Quite the reverse. It is about laziness.<br />

And here too, according to his fri<strong>en</strong>ds, Pou<strong>le</strong>nc was quite an<br />

authority! The op<strong>en</strong>ing chord suggests the first deliciously long<br />

exhalation of a Gitane’s dangerous delights. The music yawns<br />

and stretches and the smoke spirals to the ceiling in the<br />

rhythm of a very slow waltz.<br />

The Apollinaire section of this recital <strong>en</strong>ds with the earliest<br />

Pou<strong>le</strong>nc mélodies on this disc, the Trois Poèmes de Louise<br />

Lalanne. Apollinaire chose this name in order to masquerade<br />

as a fema<strong>le</strong> poet in the pages of the literary review Marges.<br />

Montparnasse laziness got the better of him however, and he<br />

rif<strong>le</strong>d through the literary jottings of his mistress in order to find<br />

something suitably feminine to meet his publishing deadline.<br />

Apollinaire’s loving collaborator was none other than the<br />

painter Marie Laur<strong>en</strong>cin (1885–1956; a painting by her is<br />

on the cover of this book<strong>le</strong>t) who designed the costumes and<br />

sets for Pou<strong>le</strong>nc’s first great success, the bal<strong>le</strong>t Les Biches,<br />

pres<strong>en</strong>ted by Diaghi<strong>le</strong>v in 1924. Laur<strong>en</strong>cin had be<strong>en</strong> <strong>en</strong>thusiastically<br />

‘discovered’ by Apollinaire in his ro<strong>le</strong> as influ<strong>en</strong>tial art<br />

critic. In this song-set only the whirlwind nons<strong>en</strong>se of Chanson<br />

is by him. Le prés<strong>en</strong>t (where Pou<strong>le</strong>nc is influ<strong>en</strong>ced by the<br />

implacab<strong>le</strong> last movem<strong>en</strong>t of Chopin’s B flat minor Sonata)<br />

and Hier are Laur<strong>en</strong>cin’s words. Hier is the first of Pou<strong>le</strong>nc’s<br />

mélodies to employ the lyrical vein in which so many of his<br />

best songs were to be writt<strong>en</strong>. By 1931 wh<strong>en</strong> it was composed,<br />

Pou<strong>le</strong>nc’s roaring tw<strong>en</strong>ties were behind him. The clown and<br />

ragamuffin shows in this song that he is capab<strong>le</strong> of melancholy<br />

things, and he chooses the sty<strong>le</strong> of a smoke-fil<strong>le</strong>d room of a<br />

Paris boîte (the ghost of Piaf’s predecessor, Marie Dubas,<br />

hovers) to make his t<strong>en</strong>der revelation.<br />

If the Apollinaire songs are of earth and water (the feel of<br />

the Paris pavem<strong>en</strong>t, the sound of the Seine), the Paul Éluard<br />

songs are made of fire and air. Indeed it must be admitted that<br />

the greatest Apollinaire settings were writt<strong>en</strong> only after Pou<strong>le</strong>nc<br />

had passed through the refining fire of contact with Éluard’s<br />

poetry. 1936 was a pivotal year: one of Pou<strong>le</strong>nc’s fri<strong>en</strong>ds, the<br />

composer Pierre-Octave Ferroud, was kil<strong>le</strong>d in a macabre<br />

accid<strong>en</strong>t; Pou<strong>le</strong>nc was reconverted to catholicism as a result<br />

of a mystical experi<strong>en</strong>ce at the shrine of the Black Virgin of<br />

Rocamadour; his song duo with the baritone Pierre Bernac was<br />

firmly established; and Éluard became a cherished collaborator<br />

in his vocal music. Out of these experi<strong>en</strong>ces a more<br />

serious and dedicated creator emerged, and in Bernac he had<br />

found a serious and dedicated interpreter to give voice to this<br />

new idealistic lyricism.<br />

From this time, the cyc<strong>le</strong> Tel jour tel<strong>le</strong> nuit is one of<br />

Pou<strong>le</strong>nc’s greatest achievem<strong>en</strong>ts. Undeterred by superficial<br />

difficulties, the composer goes to the heart of Éluard’s texts.<br />

The poet’s own experi<strong>en</strong>ces (journeys, <strong>en</strong>counters, fri<strong>en</strong>dships,<br />

dreams, and above all his love for his wife Nusch) have gone<br />

into the making of the poems. Pou<strong>le</strong>nc’s musical interpretation<br />

helps to unlock a door: behind it Éluard, the seemingly formidab<strong>le</strong><br />

intel<strong>le</strong>ctual, is revea<strong>le</strong>d for what he really was—a poet of<br />

the peop<strong>le</strong> who sang unstintingly of love, the beauties of nature<br />

and the brotherhood of man. The last mélodie in this cyc<strong>le</strong>, Nous<br />

avons fait la nuit, is one of the greatest love songs in Fr<strong>en</strong>ch<br />

music; the poem is but one man’s explication of a relationship,<br />

yet, illuminated by Pou<strong>le</strong>nc’s music, it takes on a universal<br />

significance and shows a deep understanding of the nature of<br />

love itself, and the means of its constant r<strong>en</strong>ewal. It is no<br />

surprise that the song’s postlude, which is the summing up of<br />

the cyc<strong>le</strong>, has a power that recalls the <strong>en</strong>d of a <strong>le</strong>ss optimistic<br />

but similarly heartfelt cyc<strong>le</strong>, Schumann’s Dichterliebe.<br />

3

Tu vois <strong>le</strong> feu du soir, cast in Éluard’s favourite litany<br />

form, is another love song—a hymn of praise musically<br />

translated into a g<strong>en</strong>t<strong>le</strong> rhythm as immutab<strong>le</strong> as the poet’s<br />

devotion. This is music which shows Pou<strong>le</strong>nc’s strongly<br />

idealistic side: there is no room in the Éluard settings for lightweight<br />

caprice. However, at the same time as Tel jour tel<strong>le</strong> nuit<br />

was being writt<strong>en</strong>, Pou<strong>le</strong>nc discovered a writer whose words<br />

allowed and <strong>en</strong>couraged musical settings of charm—with (in<br />

his words) ‘a kind of s<strong>en</strong>sitive audacity, of wantonness, of<br />

avidity which ext<strong>en</strong>ded into song that which I had expressed,<br />

wh<strong>en</strong> very young, in Les Biches with Marie Laur<strong>en</strong>cin’. Not<br />

surprisingly for a composer who loved to write for the fema<strong>le</strong><br />

voice, this discovery was of a woman poet, Louise de Vilmorin<br />

(1902–1969). The poetess’s family was ce<strong>le</strong>brated for the<br />

plants, seeds and flowers produced on their estate of<br />

Verrières-<strong>le</strong>-Buisson. Pou<strong>le</strong>nc wrote: ‘Few peop<strong>le</strong> move me as<br />

much as Louise de Vilmorin: because she is beautiful, because<br />

she is lame, because she writes innately immaculate Fr<strong>en</strong>ch,<br />

because her name evokes flowers and vegetab<strong>le</strong>s, because<br />

she loves her brothers like a lover and her lovers like a sister.<br />

Her beautiful face recalls the sev<strong>en</strong>te<strong>en</strong>th c<strong>en</strong>tury, as does the<br />

sound of her name.’<br />

The three short songs that make up Vilmorin’s<br />

Métamorphoses are quintess<strong>en</strong>tial Pou<strong>le</strong>nc, and indeed make<br />

up a samp<strong>le</strong>r and mini-comp<strong>en</strong>dium of his three basic song<br />

sty<strong>le</strong>s: fast and capriciously lyrical (Reine des mouettes), slow<br />

(never very slow) and touchingly lyrical (C’est ainsi que tu es)<br />

and fast in the café-concert tradition, where moto perpetuo<br />

virtuosity is the thing (Paganini). That these <strong>en</strong>chanting<br />

feather-light songs stand chronologically close to Tel jour tel<strong>le</strong><br />

nuit shows the discerning versatility of Pou<strong>le</strong>nc’s song-writing<br />

in the late 1930s.<br />

Colloque, with a text by Paul Valéry (1871–1945), was<br />

unpublished until after Pou<strong>le</strong>nc’s death. True to its tit<strong>le</strong> it is a<br />

colloquy in which the two voices never sing together. Valéry’s<br />

original tit<strong>le</strong> for the poem (dedicated to Pou<strong>le</strong>nc) was<br />

‘Dialogues pour deux flûtes’. The composer admitted that<br />

although he admired Valéry as much as Verlaine or Rimbaud,<br />

he was not comfortab<strong>le</strong> in setting his words. The vocal line and<br />

harmonies are graceful <strong>en</strong>ough, but there is no real fusion<br />

betwe<strong>en</strong> words and music. The Deux Poèmes de Louis<br />

Aragon by contrast are perfect Pou<strong>le</strong>nc. In C, Louis Aragon<br />

(1897–1982) sees the fall of France into German hands in<br />

1940 as the sorry outcome of c<strong>en</strong>turies of false values and a<br />

patriotism that had be<strong>en</strong> based on class exploitation. On paper<br />

the words can seem bitter and angry, but Pou<strong>le</strong>nc finds<br />

the heartbreak in them: Marxist poet and château-dwelling<br />

composer (Pou<strong>le</strong>nc owned a beautiful country house at Noizay<br />

near Tours) are united in song by a common Fr<strong>en</strong>ch birthright.<br />

Fêtes galantes is an antidote to too much nationalistic selfpity.<br />

The nation that produced the coolly e<strong>le</strong>gant courtiers of<br />

Watteau’s ‘Fêtes galantes’ in the reign of Louis XV, now finds<br />

itself in comp<strong>le</strong>te disarray with the onslaught of the Nazi<br />

invaders. There is not much e<strong>le</strong>gance <strong>le</strong>ft in the Fr<strong>en</strong>ch comedy<br />

of manners, but ev<strong>en</strong> if manners are thrown out of the window,<br />

comedy remains. Life under the occupation changed many<br />

things, but the institution of the cabaret song, sung at full tilt,<br />

vulgar and poetic at the same time, could never be anything<br />

but defiantly, irrepressibly Fr<strong>en</strong>ch.<br />

Priez pour paix was writt<strong>en</strong> in the dark days of the Munich<br />

crisis. The words are by Char<strong>le</strong>s, duc d’Orléans (1394–1465).<br />

Pou<strong>le</strong>nc wrote: ‘I tried to give here a feeling of fervour and<br />

above all of humility (for me the most beautiful quality of<br />

prayer). It is a prayer for a country church.’ This is not only<br />

religious music; in a subt<strong>le</strong> way it strives to achieve a medieval<br />

hieratic atmosphere appropriate to the poet.<br />

In 1935 Pou<strong>le</strong>nc re-worked the music of the sixte<strong>en</strong>thc<strong>en</strong>tury<br />

composer Claude Gervais into his Suite française<br />

(both a chamber work and a piano suite). À sa guitare, also<br />

from this period, shows the hand of the tasteful pasticheur. All<br />

this music was, in fact, writt<strong>en</strong> for Margot, a play by Édouard<br />

Bourdet about Marguerite de Valois, although Pou<strong>le</strong>nc chose<br />

to set lines by Pierre de Ronsard (1524–1585). It was first<br />

sung by the famous singing actress Yvonne Printemps. The<br />

4

orchestration of the song, as heard on Printemps’ famous<br />

recording of it, has since be<strong>en</strong> lost.<br />

The last three songs on this disc show a lighter side of the<br />

composer. Toréador (words by Jean Cocteau, 1889–1963) is<br />

the only song that contemporaries agreed the vocally ungifted<br />

Pou<strong>le</strong>nc sang better (and more nasally) than anyone else. It<br />

is a farrago of Hispanic-V<strong>en</strong>etian nons<strong>en</strong>se which powerfully<br />

evokes the music-hall. It is the kind of uproarious music that<br />

the te<strong>en</strong>age Pou<strong>le</strong>nc (inspired by Maurice Chevalier) could<br />

improvise by the metre; he was to transform such raw material<br />

into more subt<strong>le</strong> evocation in the songs of his maturity. Nous<br />

voulons une petite sœur is a patter song of small musical<br />

substance, but imm<strong>en</strong>se charm. She who can survive the<br />

pronunciation hurd<strong>le</strong>s of Madame Eustache’s Christmas list<br />

deserves a diction prize and a rest from the demands of<br />

The Hyperion catalogue can also be accessed on the Internet at www.hyperion-records.co.uk<br />

5<br />

importunate childr<strong>en</strong>. Les chemins de l’amour is another<br />

Yvonne Printemps song, this time writt<strong>en</strong> for Léocadia by Jean<br />

Anouilh (1910–1987). It gives us a glimpse of how easily<br />

Pou<strong>le</strong>nc could have writt<strong>en</strong> ‘hits’ of the time, or film music like<br />

his col<strong>le</strong>ague Georges Auric. This waltz is much sung in recitals<br />

these days and over-used as an applause-earning <strong>en</strong>core.<br />

After all, España is not the best of Chabrier, nor Boléro the best<br />

of Ravel, though both are masterpieces in their way. Pou<strong>le</strong>nc<br />

would have regarded this charming trif<strong>le</strong> as a petit-four to<br />

be pres<strong>en</strong>ted only after a substantial serving of his great<br />

mélodies. But as all gourmets and song <strong>en</strong>thusiasts know, an<br />

excel<strong>le</strong>nt petit-four is irresistib<strong>le</strong> at the right time.<br />

GRAHAM JOHNSON © 1985<br />

Pou<strong>le</strong>nc’s own words are tak<strong>en</strong> from Diary of my songs<br />

translated by Winifred Radford, published by Gollancz<br />

dedicated to the memory of our beloved teacher and fri<strong>en</strong>d<br />

PIERRE BERNAC (1899–1979)<br />

who in the singing of Pou<strong>le</strong>nc set our g<strong>en</strong>eration an examp<strong>le</strong><br />

difficult to emulate, impossib<strong>le</strong> to better<br />

FL GJ 1985<br />

If you have <strong>en</strong>joyed this recording perhaps you would like a catalogue listing the many others availab<strong>le</strong> on the Hyperion and Helios labels. If so, p<strong>le</strong>ase<br />

write to Hyperion Records Ltd, PO Box 25, London SE9 1AX, England, or email us at info@hyperion-records.co.uk, and we will be p<strong>le</strong>ased to post you<br />

one free of charge.

Voyage à Paris<br />

1 Ah ! la charmante chose Ah! how charming<br />

Quitter un pays morose to <strong>le</strong>ave a dreary place<br />

Pour Paris for Paris<br />

Paris joli delightful Paris<br />

Qu’un jour that once upon a time<br />

Dut créer l’Amour love must have created<br />

GUILLAUME APOLLINAIRE (1880–1918)<br />

Montparnasse<br />

2 Ô porte de l’hôtel avec deux plantes vertes O door of the hotel with two gre<strong>en</strong> plants<br />

Vertes qui jamais gre<strong>en</strong> which will never<br />

Ne porteront de f<strong>le</strong>urs bear any flowers<br />

Où sont mes fruits Où me planté-je where are my fruits where do I plant myself<br />

Ô porte de l’hôtel un ange est devant toi O door of the hotel an angel stands in front of you<br />

Distribuant des prospectus distributing prospectuses<br />

On n’a jamais si bi<strong>en</strong> déf<strong>en</strong>du la vertu virtue has never be<strong>en</strong> so well def<strong>en</strong>ded<br />

Donnez-moi pour toujours une chambre à la semaine give me for ever a room by the week<br />

Ange barbu vous êtes <strong>en</strong> réalité bearded angel you are really<br />

Un poète lyrique d’Al<strong>le</strong>magne a lyric poet from Germany<br />

Qui vou<strong>le</strong>z connaître Paris who wants to know Paris<br />

Vous connaissez de son pavé you know on its pavem<strong>en</strong>t<br />

Ces raies sur <strong>le</strong>squel<strong>le</strong>s il ne faut pas que l’on marche these lines on which one must not step<br />

Et vous rêvez and you dream<br />

D’al<strong>le</strong>r passer votre Dimanche à Garches of going to pass your Sunday at Garches<br />

Il fait un peu lourd et vos cheveux sont longs It is rather sultry and your hair is long<br />

Ô bon petit poète un peu bête et trop blond O good litt<strong>le</strong> poet a bit stupid and too blond<br />

Vos yeux ressemb<strong>le</strong>nt tant à ces deux grands ballons your eyes so much resemb<strong>le</strong> these two big balloons<br />

Qui s’<strong>en</strong> vont dans l’air pur that float away in the pure air<br />

À l’av<strong>en</strong>ture at random<br />

GUILLAUME APOLLINAIRE (1880–1918)<br />

Hyde Park<br />

3 Les Faiseurs de religions The promoters of religions<br />

Prêchai<strong>en</strong>t dans <strong>le</strong> brouillard were preaching in the fog<br />

Les ombres près de qui nous passions the shadowy figures near us as we passed<br />

Jouai<strong>en</strong>t à colin-maillard played blind man’s buff<br />

À soixante-dix ans At sev<strong>en</strong>ty years old<br />

Joues fraîches de petits <strong>en</strong>fants fresh cheeks of small childr<strong>en</strong><br />

V<strong>en</strong>ez v<strong>en</strong>ez Éléonore come along come along Éléonore<br />

Et que sais-je <strong>en</strong>core and what more besides<br />

6

Regardez v<strong>en</strong>ir <strong>le</strong>s cyclopes Look at the Cyclops coming<br />

Les pipes s’<strong>en</strong>volai<strong>en</strong>t the pipes were flying past<br />

Mais <strong>en</strong>vo<strong>le</strong>z-vous-<strong>en</strong> but be off<br />

Regards impénit<strong>en</strong>ts obdurate staring<br />

Et l’Europe l’Europe and Europe Europe<br />

Regards sacrés Worshipping looks<br />

Mains énamourées hands in love<br />

Et <strong>le</strong>s amants s’aimèr<strong>en</strong>t and the lovers made love<br />

Tant que prêcheurs prêchèr<strong>en</strong>t as long as the preachers preached<br />

GUILLAUME APOLLINAIRE (1880–1918)<br />

B<strong>le</strong>uet<br />

4 Jeune homme Young man<br />

De vingt ans tw<strong>en</strong>ty years old<br />

Qui as vu des choses si affreuses you who have se<strong>en</strong> such frightful things<br />

Que p<strong>en</strong>ses-tu des hommes de ton <strong>en</strong>fance what do you think of the m<strong>en</strong> of your childhood<br />

Tu connais la bravoure et la ruse you know gallantry and deceit<br />

Tu as vu la mort <strong>en</strong> face plus de c<strong>en</strong>t fois You have se<strong>en</strong> death face to face more than a hundred times<br />

Tu ne sais pas ce que c’est que la vie you do not know what life is<br />

Transmets ton intrépidité Transmit your lack of fear<br />

À ceux qui vi<strong>en</strong>dront to those who will come<br />

Après toi after you<br />

Jeune homme Young man<br />

Tu es joyeux ta mémoire est <strong>en</strong>sanglantée you are joyous your memory is stained with blood<br />

Ton âme est rouge aussi your soul is also red<br />

De joie with joy<br />

Tu as absorbé la vie de ceux qui sont morts près de toi you have absorbed the life of those who died near you<br />

Tu as de la décision You have determination<br />

Il est 17 heures et tu saurais it is five in the afternoon and you should know how<br />

Mourir to die<br />

Sinon mieux que tes aînés if not better than your elders<br />

Du moins plus pieusem<strong>en</strong>t at <strong>le</strong>ast more piously<br />

Car tu connais mieux la mort que la vie for you know death better than life<br />

Ô douceur d’autrefois O for the sweetness of other times<br />

L<strong>en</strong>teur immémoria<strong>le</strong> the slowness of time immemorial<br />

GUILLAUME APOLLINAIRE (1880–1918) Translation by RICHARD JACKSON<br />

7

Voyage<br />

5 Adieu Amour nuage qui fuit et n’a pas chu pluie féconde Farewell love cloud that flies and has not shed ferti<strong>le</strong> rain<br />

Refais <strong>le</strong> voyage de Dante take again the journey of Dante<br />

Télégraphe Te<strong>le</strong>graph<br />

Oiseau qui laisse tomber ses ai<strong>le</strong>s partout bird who <strong>le</strong>ts its wings fall everywhere<br />

Où va donc ce train qui meurt au loin Where is this train going that dies in the distance<br />

Dans <strong>le</strong>s vals et <strong>le</strong>s beaux bois frais du t<strong>en</strong>dre été si pâ<strong>le</strong> ? in the va<strong>le</strong>s and lovely fresh woods of t<strong>en</strong>der summer so pa<strong>le</strong>?<br />

La douce nuit lunaire et p<strong>le</strong>ine d’étoi<strong>le</strong>s The g<strong>en</strong>t<strong>le</strong> night moonlit and full of stars<br />

C’est ton visage que je ne vois plus it is your face that I no longer see<br />

GUILLAUME APOLLINAIRE (1880–1918)<br />

Hôtel<br />

6 Ma chambre a la forme d’une cage My room is the form of a cage<br />

Le so<strong>le</strong>il passe son bras par la f<strong>en</strong>être the sun puts its arms through the window<br />

Mais moi qui veut fumer pour faire des mirages but I want to smoke to make pictures with smoke<br />

J’allume au feu du jour ma cigarette I light my cigarette in daylight’s flame<br />

Je ne veux pas travail<strong>le</strong>r je veux fumer I don’t want to work I want to smoke<br />

GUILLAUME APOLLINAIRE (1880–1918)<br />

Le prés<strong>en</strong>t<br />

7 Si tu veux je te donnerai If you wish I will give you<br />

Mon matin, mon matin gai my morning, my gay morning<br />

Avec tous mes clairs cheveux with all my bright hair<br />

Que tu aimes ; that you love;<br />

Mes yeux verts my eyes gre<strong>en</strong><br />

Et dorés and gold<br />

Si tu veux. if you wish.<br />

Je te donnerai tout <strong>le</strong> bruit I will give you all the sound<br />

Qui se fait which is heard<br />

Quand <strong>le</strong> matin s’éveil<strong>le</strong> wh<strong>en</strong> morning awak<strong>en</strong>s<br />

Au so<strong>le</strong>il to the sun<br />

Et l’eau qui cou<strong>le</strong> and the water that flows<br />

Dans la fontaine in the fountain<br />

Tout auprès ; nearby;<br />

Et puis <strong>en</strong>cor <strong>le</strong> soir qui vi<strong>en</strong>dra vite and th<strong>en</strong> again the ev<strong>en</strong>ing that will come quickly<br />

Le soir de mon âme triste the ev<strong>en</strong>ing of my soul sad <strong>en</strong>ough<br />

À p<strong>le</strong>urer to weep<br />

Et mes mains toutes petites and my hands so small<br />

Avec mon cœur qu’il faudra près du ti<strong>en</strong> with my heart that will need to be close to your own<br />

Garder. to keep.<br />

MARIE LAURENCIN (1885–1956)<br />

8

Chanson<br />

8 Les myrtil<strong>le</strong>s sont pour la dame Myrt<strong>le</strong> is for the lady<br />

Qui n’est pas là who is abs<strong>en</strong>t<br />

La marjolaine est pour mon âme marjoram is for my soul<br />

Tralala ! tra-la-la!<br />

Le chèvrefeuil<strong>le</strong> est pour la bel<strong>le</strong> Honeysuck<strong>le</strong> is for the fair<br />

Irrésolue. irresolute.<br />

Quand cueil<strong>le</strong>rons-nous <strong>le</strong>s airel<strong>le</strong>s Wh<strong>en</strong> do we gather the bilberries<br />

Lanturlu. lan-tur-lu.<br />

Mais laissons pousser sur la tombe, But <strong>le</strong>t us plant on the tomb,<br />

Ô fol<strong>le</strong> ! Ô fou ! O crazed! O mazed!<br />

Le romarin <strong>en</strong> touffes sombres Rosemary in dark tufts<br />

Laïtou ! la-i-tou!<br />

GUILLAUME APOLLINAIRE (1880–1918)<br />

Hier<br />

9 Hier, c’est ce chapeau fané Yesterday is this faded hat<br />

Que j’ai longtemps traîné that I have trai<strong>le</strong>d about so long<br />

Hier, c’est une pauvre robe yesterday is a shabby dress<br />

Qui n’est plus à la mode. no longer in fashion.<br />

Hier, c’était <strong>le</strong> beau couv<strong>en</strong>t Yesterday was the beautiful conv<strong>en</strong>t<br />

Si vide maint<strong>en</strong>ant so empty now<br />

Et la rose mélancolie and the rose-tinged melancholy<br />

Des cours de jeunes fil<strong>le</strong>s of the young girls’ classes<br />

Hier, c’est mon cœur mal donné yesterday, is my heart ill-bestowed<br />

Une autre, une autre année ! in a past, a past year!<br />

Hier n’est plus, ce soir, Yesterday is no more, this ev<strong>en</strong>ing,<br />

Qu’une ombre than a shadow<br />

Près de moi dans ma chambre. close to me in my room.<br />

MARIE LAURENCIN (1885–1956)<br />

9

Tel jour tel<strong>le</strong> nuit<br />

bl Bonne journée j’ai revu qui je n’oublie pas A good day I have again se<strong>en</strong> which I do not forget<br />

Qui je n’oublierai jamais which I shall never forget<br />

Et des femmes fugaces dont <strong>le</strong>s yeux And wom<strong>en</strong> f<strong>le</strong>eting by whose eyes<br />

Me faisai<strong>en</strong>t une haie d’honneur formed for me a hedge of honour<br />

El<strong>le</strong>s s’<strong>en</strong>veloppèr<strong>en</strong>t dans <strong>le</strong>urs sourires they wrapped themselves in their smi<strong>le</strong>s<br />

Bonne journée j’ai vu mes amis sans soucis A good day I have se<strong>en</strong> my fri<strong>en</strong>ds carefree<br />

Les hommes ne pesai<strong>en</strong>t pas lourd the m<strong>en</strong> who were light in weight<br />

Un qui passait one who passed by<br />

Son ombre changée <strong>en</strong> souris his shadow changed into a mouse<br />

Fuyait dans <strong>le</strong> ruisseau f<strong>le</strong>d into the gutter<br />

J’ai vu <strong>le</strong> ciel très grand I have se<strong>en</strong> the great wide sky<br />

Le beau regard des g<strong>en</strong>s privés de tout the beautiful aspect of those deprived of everything<br />

Plage distante où personne n’aborde distant shore where no one lands<br />

Bonne journée qui comm<strong>en</strong>ça mélancolique A good day which began mournfully<br />

Noire sous <strong>le</strong>s arbres verts dark under the gre<strong>en</strong> trees<br />

Mais qui soudain trempée d’aurore but which sudd<strong>en</strong>ly dr<strong>en</strong>ched with dawn<br />

M’<strong>en</strong>tra dans <strong>le</strong> cœur par surprise. invaded my heart unawares.<br />

bm Une ruine coquil<strong>le</strong> vide A ruin an empty shell<br />

P<strong>le</strong>ure dans son tablier weeps into its apron<br />

Les <strong>en</strong>fants qui jou<strong>en</strong>t autour d’el<strong>le</strong> the childr<strong>en</strong> who play around it<br />

Font moins de bruit que des mouches make <strong>le</strong>ss sound than flies<br />

La ruine s’<strong>en</strong> va à tâtons The ruin goes groping<br />

Chercher ses vaches dans un pré to seek its cows in the meadow<br />

J’ai vu <strong>le</strong> jour je vois cela I have se<strong>en</strong> the day I see that<br />

Sans <strong>en</strong> avoir honte without shame<br />

Il est minuit comme une flèche It is midnight like an arrow<br />

Dans un cœur à la portée in a heart within reach<br />

Des folâtres lueurs nocturnes of the sprightly nocturnal glimmerings<br />

Qui contredis<strong>en</strong>t <strong>le</strong> sommeil. which gainsay s<strong>le</strong>ep.<br />

bn Le front comme un drapeau perdu The brow like a lost flag<br />

Je te traîne quand je suis seul I draw you wh<strong>en</strong> I am alone<br />

Dans des rues froides through the cold streets<br />

Des chambres noires the dark rooms<br />

En criant misère crying in misery<br />

10

Je ne veux pas <strong>le</strong>s lâcher I do not want to <strong>le</strong>t them go<br />

Tes mains claires et compliquées your c<strong>le</strong>ar and comp<strong>le</strong>x hands<br />

Nées dans <strong>le</strong> miroir clos des mi<strong>en</strong>nes born in the <strong>en</strong>closed mirror of my own<br />

Tout <strong>le</strong> reste est parfait All the rest is perfect<br />

Tout <strong>le</strong> reste est <strong>en</strong>core plus inuti<strong>le</strong> all the rest is ev<strong>en</strong> more use<strong>le</strong>ss<br />

Que la vie than life<br />

Creuse la terre sous ton ombre Hollow the earth b<strong>en</strong>eath your shadow<br />

Une nappe d’eau près des seins A sheet of water reaching the breasts<br />

Où se noyer wherein to drown oneself<br />

Comme une pierre. like a stone.<br />

bo Une roulotte couverte <strong>en</strong> tui<strong>le</strong>s A gypsy wagon roofed with ti<strong>le</strong>s<br />

Le cheval mort un <strong>en</strong>fant maître the horse dead a child master<br />

P<strong>en</strong>sant <strong>le</strong> front b<strong>le</strong>u de haine thinking his brow blue with hatred<br />

À deux seins s’abbattant sur lui of two breasts beating down upon him<br />

Comme deux poings like two fists<br />

Ce mélodrame nous arrache This melodrama tears away from us<br />

La raison du cœur. the sanity of the heart.<br />

bp À toutes brides toi dont <strong>le</strong> fantôme Riding full tilt you whose phantom<br />

Piaffe la nuit sur un violon prances at night on a violin<br />

Vi<strong>en</strong>s régner dans <strong>le</strong>s bois come to reign in the woods<br />

Les verges de l’ouragan The lashings of the tempest<br />

Cherch<strong>en</strong>t <strong>le</strong>ur chemin par chez toi seek their path by way of you<br />

Tu n’es pas de cel<strong>le</strong>s you are not of those<br />

Dont on inv<strong>en</strong>te <strong>le</strong>s désirs whose desires one imagines<br />

Vi<strong>en</strong>s boire un baiser par ici Come drink a kiss here<br />

Cède au feu qui te désespère. surr<strong>en</strong>der to the fire which drives you to despair.<br />

bq Une herbe pauvre Scanty grass<br />

Sauvage wild<br />

Apparut dans la neige appeared in the snow<br />

C’était la santé it was health<br />

Ma bouche fut émerveillée my mouth marvel<strong>le</strong>d<br />

Du goût d’air pur qu’el<strong>le</strong> avait at the savour of pure air it had<br />

El<strong>le</strong> était fanée. it was withered.<br />

11

Je n’ai <strong>en</strong>vie que de t’aimer I long only to love you<br />

Un orage emplit la vallée a storm fills the val<strong>le</strong>y<br />

Un poisson la rivière a fish the river<br />

Je t’ai faite à la tail<strong>le</strong> de ma solitude I have formed you to the pattern of my solitude<br />

Le monde <strong>en</strong>tier pour se cacher the who<strong>le</strong> world to hide in<br />

Des jours des nuits pour se compr<strong>en</strong>dre days and nights to understand one another<br />

Pour ne plus ri<strong>en</strong> voir dans tes yeux To see nothing more in your eyes<br />

Que ce que je p<strong>en</strong>se de toi but what I think of you<br />

Et d’un monde à ton image and of a world in your lik<strong>en</strong>ess<br />

Et des jours et des nuits réglés par tes paupières. And of days and nights ordered by your eyelids.<br />

bs Figure de force brûlante et farouche Image of fiery wild forcefulness<br />

Cheveux noirs où l’or cou<strong>le</strong> vers <strong>le</strong> sud black hair wherein the gold flows towards the south<br />

Aux nuits corrompues on corrupt nights<br />

Or <strong>en</strong>glouti étoi<strong>le</strong> impure <strong>en</strong>gulfed gold-tainted star<br />

Dans un lit jamais partagé in a bed never shared<br />

Aux veines des temp<strong>le</strong>s To the veins of the temp<strong>le</strong>s<br />

Comme au bouts des seins as to the tips of the breasts<br />

La vie se refuse life d<strong>en</strong>ies itself<br />

Les yeux nul ne peut <strong>le</strong>s crever no one can blind the eyes<br />

Boire <strong>le</strong>ur éclat ni <strong>le</strong>urs larmes drink their brilliance or their tears<br />

Le sang au-dessus d’eux triomphe pour lui seul the blood above them triumphs for itself alone<br />

Intraitab<strong>le</strong> démesurée Intractab<strong>le</strong> unbounded<br />

Inuti<strong>le</strong> use<strong>le</strong>ss<br />

Cette santé bâtit une prison. this health builds a prison.<br />

bt Nous avons fait la nuit je ti<strong>en</strong>s ta main je veil<strong>le</strong> We have made night I hold your hand I watch over you<br />

Je te souti<strong>en</strong>s de toutes mes forces I sustain you with all my str<strong>en</strong>gth<br />

Je grave sur un roc l’étoi<strong>le</strong> de tes forces I <strong>en</strong>grave on a rock the star of your str<strong>en</strong>gth<br />

Sillons profonds où la bonté de ton corps germera deep furrows where the goodness of your body will germinate<br />

Je me répète ta voix cachée ta voix publique I repeat to myself your secret voice your public voice<br />

Je ris <strong>en</strong>core de l’orgueil<strong>le</strong>use I laugh still at the haughty wom<strong>en</strong><br />

Que tu traites comme une m<strong>en</strong>diante whom you treat like a beggar at the fools<br />

Des fous que tu respectes des simp<strong>le</strong>s où tu te baignes whom you respect the simp<strong>le</strong> folk in whom you immerse yourself<br />

Et dans ma tête qui se met doucem<strong>en</strong>t d’accord avec and in my head which g<strong>en</strong>tly begins to harmonize with<br />

la ti<strong>en</strong>ne avec la nuit yours with the night<br />

Je m’émerveil<strong>le</strong> de l’inconnue que tu devi<strong>en</strong>s I marvel at the stranger that you become<br />

Une inconnue semblab<strong>le</strong> à toi semblab<strong>le</strong> à tout ce que j’aime a stranger resembling you resembling all that I love<br />

Qui est toujours nouveau. which is ever new.<br />

PAUL ÉLUARD (1895–1952) pseudonym for Eugène Grind<strong>le</strong><br />

12

u Tu vois <strong>le</strong> feu du soir qui sort de sa coquil<strong>le</strong> You see the fire of ev<strong>en</strong>ing emerging from its shell<br />

Et tu vois la forêt <strong>en</strong>fouie dans sa fraîcheur and you see the forest buried in its coolness<br />

Tu vois la plaine nue aux flancs du ciel traînard You see the bare plain at the edges of the straggling sky<br />

La neige haute comme la mer the snow high as the sea<br />

Et la mer haute dans l’azur and the sea high in the azure<br />

Pierres parfaites et bois doux secours voilés Perfect stones and sweet woods vei<strong>le</strong>d succours<br />

Tu vois des vil<strong>le</strong>s teintes de mélancolie you see cities tinged with gilded melancholy<br />

Dorée des trottoirs p<strong>le</strong>ins d’excuses pavem<strong>en</strong>ts full of excuses<br />

Une place où la solitude a sa statue a square where solitude has its statue<br />

Souriante et l’amour une seu<strong>le</strong> maison smiling and love a sing<strong>le</strong> house<br />

Tu vois <strong>le</strong>s animaux You see animals<br />

Sosies malins sacrifiés l’un à l’autre malign doub<strong>le</strong>s sacrificed one to another<br />

Frères immaculés aux ombres confondues immaculate brothers with interming<strong>le</strong>d shadows<br />

Dans un désert de sang in a wilderness of blood<br />

Tu vois un bel <strong>en</strong>fant quand il joue quand il rit You see a beautiful child wh<strong>en</strong> he plays wh<strong>en</strong> he laughs<br />

Il est bi<strong>en</strong> plus petit he is smal<strong>le</strong>r<br />

Que <strong>le</strong> petit oiseau du bout des branches than the litt<strong>le</strong> bird on the tip of the branches<br />

Tu vois un paysage aux saveurs d’hui<strong>le</strong> et d’eau You see a countryside with its savour of oil and of water<br />

D’où la roche est exclue où la terre abandonne where the rock is excluded where the earth abandons<br />

Sa verdure à l’été qui la couvre de fruits her gre<strong>en</strong>ess to the summer which covers her with fruit<br />

Des femmes desc<strong>en</strong>dant de <strong>le</strong>ur miroir anci<strong>en</strong> Wom<strong>en</strong> desc<strong>en</strong>ding from their anci<strong>en</strong>t mirror<br />

T’apport<strong>en</strong>t <strong>le</strong>ur jeunesse et <strong>le</strong>ur foi <strong>en</strong> la ti<strong>en</strong>ne bring you their youth and their faith in yours<br />

Et l’une sa clarté la voi<strong>le</strong> qui t’<strong>en</strong>traîne and one of them vei<strong>le</strong>d by her clarity who allures you<br />

Te fait secrètem<strong>en</strong>t voir <strong>le</strong> monde sans toi. secretly makes you see the world without yourself.<br />

PAUL ÉLUARD (1895–1952) pseudonym for Eugène Grind<strong>le</strong><br />

13

Métamorphoses<br />

cl Reine des mouettes, mon orpheline, Que<strong>en</strong> of the seagulls, my orphan,<br />

Je t’ai vue rose, je m’<strong>en</strong> souvi<strong>en</strong>s, I have se<strong>en</strong> you pink, I remember it,<br />

Sous <strong>le</strong>s brumes mousselines under the misty muslins<br />

De ton deuil anci<strong>en</strong>. of your bygone mourning.<br />

Rose d’aimer <strong>le</strong> baiser qui chagrine Pink that you liked the kiss which vexes you<br />

Tu te laissais accorder à mes mains you surr<strong>en</strong>dered to my hands<br />

Sous <strong>le</strong>s brumes mousselines under the misty muslins<br />

Voi<strong>le</strong>s de nos li<strong>en</strong>s. veils of our bond.<br />

Rougis, rougis, mon baiser te devine Blush, blush, my kiss divines you<br />

Mouette prise aux nœuds des grands chemins. seagull captured at the meeting of the great highways.<br />

Reine des mouettes, mon orpheline, Que<strong>en</strong> of the seagulls, my orphan,<br />

Tu étais rose accordée à mes mains you were pink surr<strong>en</strong>dered to my hands<br />

Rose sous <strong>le</strong>s mousselines pink under the muslins<br />

Et je m’<strong>en</strong> souvi<strong>en</strong>s. and I remember it.<br />

C’est ainsi que tu es<br />

cm Ta chair, d’âme mêlée, Your body imbued with soul,<br />

Chevelure emmêlée, your tang<strong>le</strong>d hair,<br />

Ton pied courant <strong>le</strong> temps, your foot pursuing time,<br />

Ton ombre qui s’ét<strong>en</strong>d your shadow which stretches<br />

Et murmure à ma tempe. and whispers close to my temp<strong>le</strong>s.<br />

Voilà, c’est ton portrait, There, that is your portrait,<br />

C’est ainsi que tu es, it is thus that you are,<br />

Et je veux te l’écrire and I want to write it to you<br />

Pour que la nuit v<strong>en</strong>ue, so that wh<strong>en</strong> night comes,<br />

Tu puisses croire et dire, you may believe and say,<br />

Que je t’ai bi<strong>en</strong> connue. that I knew you well.<br />

Paganini<br />

cn Violon hippocampe et sirène Violin sea-horse and sir<strong>en</strong><br />

Berceau des cœurs cœur et berceau crad<strong>le</strong> of hearts heart and crad<strong>le</strong><br />

Larmes de Marie Made<strong>le</strong>ine tears of Mary Magda<strong>le</strong>n<br />

Soupir d’une Reine sigh of a Que<strong>en</strong><br />

Écho echo<br />

Violon orgueil des mains légères Violin pride of agi<strong>le</strong> hands<br />

Départ à cheval sur <strong>le</strong>s eaux departure on horseback on the water<br />

Amour chevauchant <strong>le</strong> mystère love astride mystery<br />

Vo<strong>le</strong>ur <strong>en</strong> prière thief at prayer<br />

Oiseau bird<br />

14

Violon femme morganatique Violin morganatic woman<br />

Chat botté courant la forêt puss-in-boots ranging the forest<br />

Puits des vérités lunatiques well of insane truths<br />

Confession publique public confession<br />

Corset corset<br />

Violon alcool de l’âme <strong>en</strong> peine Violin alcohol of the troub<strong>le</strong>d soul<br />

Préfér<strong>en</strong>ce musc<strong>le</strong> du soir prefer<strong>en</strong>ce musc<strong>le</strong> of the ev<strong>en</strong>ing<br />

Epau<strong>le</strong>s des saisons soudaines shoulder of sudd<strong>en</strong> seasons<br />

Feuil<strong>le</strong> de chêne <strong>le</strong>af of the oak<br />

Miroir mirror<br />

Violon chevalier du si<strong>le</strong>nce Violin knight of si<strong>le</strong>nce<br />

Jouet évadé du bonheur plaything escaped from happiness<br />

Poitrine des mil<strong>le</strong> prés<strong>en</strong>ces bosom of a thousand pres<strong>en</strong>ces<br />

Bateau de plaisance boat of p<strong>le</strong>asure<br />

Chasseur. hunter.<br />

LOUISE LEVEQUE DE VILMORIN (1902–1969)<br />

Colloque<br />

co BARYTON: D’une rose mourante Like to a dying rose<br />

L’<strong>en</strong>nui p<strong>en</strong>che vers nous ; weariness weighs upon us;<br />

Tu n’es pas différ<strong>en</strong>te you are not differ<strong>en</strong>t<br />

Dans ton si<strong>le</strong>nce doux in your sweet si<strong>le</strong>nce<br />

De cette f<strong>le</strong>ur mourante : from this dying flower:<br />

El<strong>le</strong> se meurt pour nous … it dies for us …<br />

Tu me semb<strong>le</strong>s pareil<strong>le</strong> you seem to resemb<strong>le</strong><br />

À cel<strong>le</strong> dont l’oreil<strong>le</strong> her whose head<br />

Était sur mes g<strong>en</strong>oux, I crad<strong>le</strong>d in my lap,<br />

À cel<strong>le</strong> dont l’oreil<strong>le</strong> but who never<br />

Ne m’écoutait jamais ! list<strong>en</strong>ed to me!<br />

Tu me semb<strong>le</strong>s pareil<strong>le</strong> You seem to resemb<strong>le</strong><br />

À l’autre que j’aimais : the other whom I loved:<br />

Mais de cel<strong>le</strong> anci<strong>en</strong>ne but the lips of this former love<br />

Sa bouche était la mi<strong>en</strong>ne. were one with my own.<br />

SOPRANO: Que me compares-tu Why do you compare me<br />

Quelque rose fanée ? to some faded rose?<br />

L’amour n’a de vertu Love’s one virtue<br />

Que fraîche et spontanée. is fresh and spontaneous.<br />

Mon regard dans <strong>le</strong> ti<strong>en</strong> Gazing into your eyes<br />

Ne trouve que son bi<strong>en</strong>. I find only what is good.<br />

15

Je m’y vois toute nue ! I see myself laid bare!<br />

Mes yeux effaceront My eyes will make you forget<br />

Tes larmes qui seront your tears flowing<br />

D’un souv<strong>en</strong>ir v<strong>en</strong>ues. from a memory.<br />

Si ton désir naquit If your desire is born<br />

Qu’il meure sur ma couche <strong>le</strong>t it die on my couch<br />

Et sur mes lèvres qui and on my lips<br />

T’emporteront la bouche. which will impassion your own.<br />

PAUL VALÉRY (1871–1945)<br />

C<br />

cp J’ai traversé <strong>le</strong>s ponts de Cé I have crossed the bridges of Cé<br />

C’est là que tout a comm<strong>en</strong>cé it is there that it all began<br />

Une chanson des temps passés A song of bygone days<br />

Par<strong>le</strong> d’un chevalier b<strong>le</strong>ssé tells the ta<strong>le</strong> of a wounded knight<br />

D’une rose sur la chaussée Of a rose on the carriageway<br />

Et d’un corsage délacé and an unlaced bodice<br />

Du château d’un duc ins<strong>en</strong>sé Of the cast<strong>le</strong> of a mad duke<br />

Et des cygnes dans <strong>le</strong>s fossés and swans on the moats<br />

De la prairie où vi<strong>en</strong>t danser Of the meadow where comes dancing<br />

Une éternel<strong>le</strong> fiancée an eternal betrothed love<br />

Et j’ai bu comme un lait glacé And I drank like iced milk<br />

Le long lai des gloires faussées the long lay of false glories<br />

La Loire emporte mes p<strong>en</strong>sées The Loire carries my thoughts away<br />

Avec <strong>le</strong>s voitures versées with the overturned cars<br />

Et <strong>le</strong>s armes désamorcées And the unprimed weapons<br />

Et <strong>le</strong>s larmes mal effacées and the ill-dried tears<br />

Ô ma France ô ma délaissée 0 my France O my forsak<strong>en</strong> France<br />

J’ai traversé <strong>le</strong>s ponts de Cé I have crossed the bridges of Cé<br />

LOUIS ARAGON (1897–1982)<br />

16

Fêtes galantes<br />

cq On voit des marquis sur des bicyc<strong>le</strong>ttes You see fops on bicyc<strong>le</strong>s<br />

On voit des marlous <strong>en</strong> cheval-jupon you see pimps in kilts<br />

On voit des morveux avec des voi<strong>le</strong>ttes you see brats with veils<br />

On voit des pompiers brû<strong>le</strong>r <strong>le</strong>s pompons you see firem<strong>en</strong> burning their pompons<br />

On voit des mot jetés à la voirie You see words thrown on the rubbish heap<br />

On voit des mots é<strong>le</strong>vés au pavois you see words praised to the skies<br />

On voit <strong>le</strong>s pieds des <strong>en</strong>fants de Marie you see the feet of Mary’s childr<strong>en</strong><br />

On voit <strong>le</strong> dos des diseuses à voix you see the backs of cabaret singers<br />

On voit des voitures à gazogène You see motor cars run on gasog<strong>en</strong>e<br />

On voit aussi des voitures à bras you see also handcarts<br />

On voit des lascars que <strong>le</strong>s longs nez gên<strong>en</strong>t you see wily fellows whose long noses hinder them<br />

On voit des coïons de dix-huit carats you see fools of the first water<br />

On voit ici ce que l’on voit ail<strong>le</strong>urs You see what you see elsewhere<br />

On voit des demoisel<strong>le</strong>s dévoyées you see girls who are <strong>le</strong>d astray<br />

On voit des voyous On voit des voyeurs you see guttersnipes you see perverts<br />

On voit sous <strong>le</strong>s ponts passer des noyés you see drowned folk floating under the bridges<br />

On voit chômer <strong>le</strong>s marchands de chaussures You see out-of-work shoemakers<br />

On voit mourir d’<strong>en</strong>nui <strong>le</strong>s mireurs d’œufs you see egg cand<strong>le</strong>rs bored to death<br />

On voit péricliter <strong>le</strong>s va<strong>le</strong>urs sûres you see true values in jeopardy<br />

Et fuire la vie à la six-quatre-deux and life whirling by in a slapdash way<br />

LOUIS ARAGON (1897–1982)<br />

cr Priez pour paix, douce Vierge Marie, Pray for peace, g<strong>en</strong>t<strong>le</strong> Virgin Mary,<br />

Reyne des cieulx et du monde maîtresse, que<strong>en</strong> of the skies and mistress of the world,<br />

Faictes prier, par vostre courtoisie, of your courtesy, ask for the prayers<br />

Saints et Saintes et pr<strong>en</strong>ez vostre adresse of all the saints, and make your address<br />

Vers vostre fils, requérant sa haultesse to your son, beseeching his majesty<br />

Qu’il Lui plaise son peup<strong>le</strong> regarder, that he may p<strong>le</strong>ase to look upon his peop<strong>le</strong>,<br />

Que de son sang a voulu racheter, whom he wished to redeem with his blood,<br />

En déboutant guerre qui tout desvoye ; banishing war which disrupts all.<br />

De prières ne vous veuil<strong>le</strong>z lasser : Do not cease your prayers.<br />

Priez pour paix, <strong>le</strong> vrai trésor de joye. Pray for peace, the true treasure of joy.<br />

CHARLES, DUC D’ORLÉANS (1394–1465)<br />

17

À sa guitare<br />

cs Ma guitare, je te chante, My guitar, I sing to you,<br />

Par qui seu<strong>le</strong> je déçois, through whom alone I deceive,<br />

Je déçois, je romps, j’<strong>en</strong>chante I deceive, I break off, I <strong>en</strong>chant<br />

Les amours que je reçois. the loves that I receive.<br />

Au son de ton harmonie At the sound of your harmony<br />

Je rafraîchis ma cha<strong>le</strong>ur, I refresh my ardour,<br />

Ma cha<strong>le</strong>ur flamme infinie the infinite flame of my ardour<br />

Naissante d’un beau malheur. born of a beautiful sorrow.<br />

PIERRE DE RONSARD (1524–1585)<br />

Toréador<br />

ct Pépita reine de V<strong>en</strong>ise Pepita, que<strong>en</strong> of V<strong>en</strong>ice,<br />

Quand tu vas sous ton mirador wh<strong>en</strong> you appear with your mirador<br />

Tour <strong>le</strong>s gondoliers se dis<strong>en</strong>t all the gondoliers say—<br />

Pr<strong>en</strong>ds garde toréador ! look out, toreador!<br />

Sur ton cœur personne ne règne Nobody ru<strong>le</strong>s your heart,<br />

Dans <strong>le</strong> grand palais où tu dors as you s<strong>le</strong>ep in the great palace,<br />

Et près de toi la vieil<strong>le</strong> duègne and nearby the old du<strong>en</strong>na<br />

Guette <strong>le</strong> toréador. watches out for the toreador.<br />

Toréador brave des braves Toreador, the bravest of all,<br />

Lorsque sur la Place Saint-Marc wh<strong>en</strong> in Saint Mark’s Square<br />

Le taureau <strong>en</strong> fureur qui bave the bull foaming with fury<br />

Tombe tué par ton poignard, falls, kil<strong>le</strong>d by your dagger,<br />

Ce n’est pas l’orgueil qui caresse It isn’t pride which caresses<br />

Ton cœur sous la baouta d’or your heart under your gold cape;<br />

Car pour une jeune déesse it’s for a young goddess<br />

Tu brû<strong>le</strong>s toréador. that you burn, toreador.<br />

Bel<strong>le</strong> Espagno-o-<strong>le</strong> Lovely Spanish girl,<br />

Dans ta gondo-o-<strong>le</strong> in your gondola<br />

Tu caraco-o-<strong>le</strong>s you twist and turn—<br />

Carm<strong>en</strong>cita ! Carm<strong>en</strong>cita!<br />

Sous ta manti-i-l<strong>le</strong> Under your mantilla,<br />

Œil qui péti-i-l<strong>le</strong> your eyes sparkling,<br />

Bouche qui bri-i-l<strong>le</strong> your mouth glinting,<br />

C’est Pépita-a-a … it’s Pepita!<br />

18

C’est demin (jour de Saint Éscure) Tomorrow, Saint Escure’s day,<br />

Qu’aura lieu <strong>le</strong> combat à mort a fight to the death will take place;<br />

Le canal est p<strong>le</strong>in de voitures the canal is full of craft<br />

Fêtant <strong>le</strong> toréador. in honour of the toreador.<br />

De V<strong>en</strong>ise plus d’une bel<strong>le</strong> More than one beautiful heart<br />

Palpite pour savoir ton sort flutters to know your fate,<br />

Mais tu méprises <strong>le</strong>urs d<strong>en</strong>tel<strong>le</strong>s but you scorn their beauty,<br />

Tu souffres toréador. you are suffering, toreador.<br />

Car ne voyant pas apparaître Because you hav<strong>en</strong>’t se<strong>en</strong><br />

(Caché derrière un oranger) (hidd<strong>en</strong> behind orange-blossom)<br />

Pépita seu<strong>le</strong> à sa f<strong>en</strong>être Pepita, alone at her window,<br />

Tu médites de te v<strong>en</strong>ger. you start thinking of v<strong>en</strong>geance.<br />

Sous ton caftan passe ta dague Under your kaftan is your dagger—<br />

La jalousie au cœur te mord jealousy bites your heart,<br />

Et seul avec <strong>le</strong> bruit des vagues and alone with the sound of the waves<br />

Tu p<strong>le</strong>ures toréador. you weep, toreador.<br />

Que de cavaliers ! Que de monde ! What g<strong>en</strong>try—what a crowd<br />

Remplit l’arène jusqu’au bord fills the ar<strong>en</strong>a to the brim—<br />

On veint de c<strong>en</strong>t lieues à la ronde they’ve come from a hundred <strong>le</strong>agues around<br />

T’acclamer toréador. to cheer you on, toreador.<br />

C’est fait il <strong>en</strong>tre dans l’arène It’s starting, he <strong>en</strong>ters the ar<strong>en</strong>a<br />

Avec plus de f<strong>le</strong>gme qu’un lord coo<strong>le</strong>r than a lord,<br />

Mais il peut avancer à peine but he can scarcely move,<br />

Le pauvre toréador ; the poor toreador;<br />

Il ne reste à son rêve morne All that’s <strong>le</strong>ft of his sad dream<br />

Que de mourir sous tous <strong>le</strong>s yeux is to die in front of everyone,<br />

En s<strong>en</strong>tant pénétrer des cornes feeling the horns p<strong>en</strong>etrate<br />

Dans son triste front soucieux. his sad and grieving brain.<br />

Car Pépita se montre assise For he sees Pepita, seated,<br />

Offrant son regard et son corps offering her glances and her body<br />

Au plus vieux doge de V<strong>en</strong>ise to the oldest doge in V<strong>en</strong>ice,<br />

Et rit du toréador. and laughing at the toreador.<br />

JEAN COCTEAU (1889–1963) translation by RICHARD JACKSON<br />

19

Nous voulons une petite sœur<br />

cu Madame Eustache a dix-sept fil<strong>le</strong>s, Madame Eustache has sev<strong>en</strong>te<strong>en</strong> daughters,<br />

Ce n’est pas trop, which is none too many<br />

Mais c’est assez. but it is quite <strong>en</strong>ough.<br />

La jolie petite famil<strong>le</strong> What a fine family they make,<br />

Vous avez dû la voir passer. you must have se<strong>en</strong> them go by.<br />

Le vingt Décembre on <strong>le</strong>s appel<strong>le</strong> : On December 20th, they are cal<strong>le</strong>d together:<br />

Que vou<strong>le</strong>z-vous mesdemoisel<strong>le</strong>s What would you like girls<br />

Pour votre Noël ? as a Christmas pres<strong>en</strong>t?<br />

Vou<strong>le</strong>z-vous une boîte à poudre ? Would you like a powder box?<br />

Vou<strong>le</strong>z-vous des petits mouchoirs ? Would you like litt<strong>le</strong> handkerchiefs?<br />

Un petit nécessaire à coudre ? Would you like a small sewing-case?<br />

Un perroquet sur son perchoir ? A parrot sitting on its perch?<br />

Vou<strong>le</strong>z-vous un petit ménage ? Would you like a doll’s house?<br />

Un stylo qui tache <strong>le</strong>s doigts ? A p<strong>en</strong> which makes your fingers inky?<br />

Un pompier qui plonge et qui nage ? A fireman which can dive and swim?<br />

Un vase à f<strong>le</strong>urs presque chinois ? An almost-Chinese flowered vase?<br />

Mais <strong>le</strong>s dix-sept <strong>en</strong>fants <strong>en</strong> chœur But the sev<strong>en</strong>te<strong>en</strong> childr<strong>en</strong> chorused<br />

Ont répondu : Non, non, non, non, non. all together: No, no, no, no, no.<br />

Ce n’est pas ca que nous voulons That isn’t what we want.<br />

Nous voulons une petite sœur We want a baby sister<br />

Ronde et joufflue comme un ballon with round, fat cheeks like a balloon,<br />

Avec un petit nez farceur with a comical litt<strong>le</strong> nose,<br />

Avec <strong>le</strong>s cheveux blonds with gold<strong>en</strong> hair<br />

Avec la bouche <strong>en</strong> cœur and a heart-shaped mouth.<br />

Nous voulons une petite sœur. We want a baby sister.<br />

L’hiver suivant ; el<strong>le</strong>s sont dix-huit, The next winter, there are eighte<strong>en</strong> of them,<br />

Ce n’est pas trop, which is none too many,<br />

Mais c’est assez. but quite <strong>en</strong>ough.<br />

Noël approche et <strong>le</strong>s petites Christmas was drawing near and the girls<br />

Sont vraim<strong>en</strong>t bi<strong>en</strong> embarrassées. were in a real quandary.<br />

Madame Eustache <strong>le</strong>s appel<strong>le</strong> : Madame Eustache cal<strong>le</strong>d them together:<br />

Décidez-vous mesdemoisel<strong>le</strong>s Make up your minds, girls,<br />

Pour votre Noël : for your Christmas pres<strong>en</strong>t:<br />

Vou<strong>le</strong>z-vous un mouton qui frise ? would you like a woolly-haired sheep?<br />

Vou<strong>le</strong>z-vous un réveill’ matin ? Would you like an alarm-clock?<br />

Un coffret d’alcool d<strong>en</strong>tifrice ? A bott<strong>le</strong> of alcoholized mouth-wash?<br />

Trois petits coussins de satin ? Three litt<strong>le</strong> satin cushions?<br />

Vou<strong>le</strong>z-vous une panoplie Would you like a costume<br />

De danseuse de l’Opéra ? of prima bal<strong>le</strong>rina?<br />

Un petit fauteuil qui se plie A litt<strong>le</strong> folding-chair<br />

Et que l’on porte sous son bras ? which can be carried under the arm?<br />

20

Mais <strong>le</strong>s dix-huit <strong>en</strong>fants <strong>en</strong> chœur But the eighte<strong>en</strong> childr<strong>en</strong> chorused<br />

Ont répondu : Non, non, non, non, non. all together: No, no, no, no, no.<br />

Ce n’est pas ca que nous voulons That isn’t what we want.<br />

Nous voulons une petite sœur We want a baby sister,<br />

Ronde et joufflue comme un ballon with round, fat cheeks like a balloon,<br />

Avec un petit nez farceur with a comical litt<strong>le</strong> nose,<br />

Avec <strong>le</strong>s cheveux blonds with gold<strong>en</strong> hair<br />

Avec la bouche <strong>en</strong> cœur and a heart-shaped mouth.<br />

Nous voulons une petite sœur. We want a baby sister.<br />

El<strong>le</strong>s sont dix-neuf l’année suivante, There are ninete<strong>en</strong> of them the following year,<br />

Ce n’est pas trop, which is not too many<br />

Mais c’est assez. but is quite <strong>en</strong>ough.<br />

Quand revi<strong>en</strong>t l’époque émouvante Wh<strong>en</strong> the heart-warming season returns,<br />

Noël va de nouveau passer. Christmas is round the corner again.<br />

Madame Eustache <strong>le</strong>s appel<strong>le</strong> : Madame Eustache calls them together:<br />

Décidez-vous mesdemoisel<strong>le</strong>s Make up your minds, girls,<br />

Pour votre Noël : for your Christmas pres<strong>en</strong>t:<br />

Vou<strong>le</strong>z-vous des jeux exc<strong>en</strong>triques would you like ecc<strong>en</strong>tric toys<br />

Avec des pi<strong>le</strong>s et des moteurs ? with batteries and <strong>en</strong>gines?<br />

Vou<strong>le</strong>z-vous un ours é<strong>le</strong>ctrique ? Would you like an e<strong>le</strong>ctric bear?<br />

Un hippopotame à vapeur ? A steam hippopotamus?<br />

Pour col<strong>le</strong>r des cartes posta<strong>le</strong>s Would you like a superb scrap-book<br />

Vou<strong>le</strong>z-vous un superbe album ? in which postcards can be pasted?<br />

Une automobi<strong>le</strong> à péda<strong>le</strong>s ? Would you like a car with pedals?<br />

Une bague <strong>en</strong> aluminium ? Or an aluminium ring?<br />

Mais <strong>le</strong>s dix-neuf <strong>en</strong>fants <strong>en</strong> chœur But the ninete<strong>en</strong> childr<strong>en</strong> chorused<br />

Ont répondu : Non, non, non, non, non. all together: No, no, no, no, no.<br />

Ce n’est pas ca que nous voulons. That isn’t what we want.<br />

Nous voulons deux petites jumel<strong>le</strong>s. We want two litt<strong>le</strong> twin sisters.<br />

Deux sœurs exactem<strong>en</strong>t pareil<strong>le</strong>s Two sisters alike as two peas,<br />

Deux sœurs avec des cheveux blonds ! two sisters with gold<strong>en</strong> hair!<br />

Leur mère a dit : c’est bi<strong>en</strong> Their mother said: very well,<br />

Mais il n’y a pas moy<strong>en</strong> ; but it’s quite out of the question;<br />

Cette année, vous n’aurez ri<strong>en</strong>, ri<strong>en</strong>, ri<strong>en</strong>. this year, you will have nothing, nothing at all!<br />

‘JABOUME’, JEAN NOHAIN (1900–1981)<br />

21

Les chemins de l’amour<br />

dl Les chemins qui vont à la mer The paths that <strong>le</strong>ad to the sea<br />

Ont gardé de notre passage have kept from our passing<br />

Des f<strong>le</strong>urs effeuillées flowers with fal<strong>le</strong>n petals<br />

Et l’écho sous <strong>le</strong>urs arbres and the echo b<strong>en</strong>eath their trees<br />

De nos deux rires clairs. of our c<strong>le</strong>ar laughter.<br />

Hélas ! <strong>le</strong>s jours de bonheur, Alas! of our days of happiness,<br />

Radieuses joies <strong>en</strong>volées, radiant joys now flown,<br />

Je vais sans retrouver traces no trace can be found again<br />

Dans mon cœur. in my heart.<br />

Chemins de mon amour, Paths of my love,<br />

Je vous cherche toujours, I seek you for ever,<br />

Chemins perdus, vous n’êtes plus Lost paths, you are there no more<br />

Et vos échos sont sourds. and your echoes are mute.<br />

Chemins du désespoir, Paths of despair,<br />

Chemins du souv<strong>en</strong>ir, paths of memory,<br />

Chemins du premier jour, paths of the first day,<br />

Divins chemins d’amour. divine paths of love.<br />

Si je dois l’oublier un jour, If one day I must forget,<br />

La vie effaçant toute chose, life effacing all remembrance,<br />

Je veux dans mon cœur qu’un souv<strong>en</strong>ir I would, in my heart that one memory<br />

Repose plus fort que l’autre amour. remains stronger than the former love.<br />

Le souv<strong>en</strong>ir du chemin, The memory of the path,<br />

Où tremblante et toute éperdue, where trembling and utterly bewildered<br />

Un jour j’ai s<strong>en</strong>ti sur moi brû<strong>le</strong>r tes mains. one day I felt upon me your burning hands.<br />

JEAN ANOUILH (1910–1987) Except where shown otherwise, translations are by WINIFRED RADFORD<br />

from Francis Pou<strong>le</strong>nc—The Man and his Songs by Pierre Bernac (1977),<br />

published by Victor Gollancz with whose kind permission they are reproduced<br />

22

« Lorsqu’il s’agit de Paris j’y vais souv<strong>en</strong>t de ma larme<br />

ou de ma note » FRANCIS POULENC (1899–1963)<br />

J<br />

AMAIS UN COMPOSITEUR n’adora une métropo<strong>le</strong> autant<br />

que Pou<strong>le</strong>nc adora Paris. Cet être ultraraffiné, volontiers<br />

<strong>en</strong>clin à l’<strong>en</strong>nui et à la dépression, détestait l’inévitab<strong>le</strong> exil<br />

que lui imposai<strong>en</strong>t <strong>le</strong>s tournées de concerts <strong>en</strong> province, loin<br />

de sa chère vil<strong>le</strong> nata<strong>le</strong>. Dithyrambe éhonté disant toute sa joie<br />

(et son soulagem<strong>en</strong>t) à l’idée de retrouver <strong>le</strong> melting-pot<br />

urbain, Voyage à Paris v<strong>en</strong>ait clore ces récitals <strong>en</strong> un bis un<br />

brin malicieux. « Quand on me connaît, il paraîtra tout naturel<br />

que j’aie ouvert une bouche de carpe pour happer <strong>le</strong>s vers<br />

délicieusem<strong>en</strong>t stupides du Voyage à Paris », écrivit Pou<strong>le</strong>nc<br />

dans son Journal de mes mélodies. Ado<strong>le</strong>sc<strong>en</strong>t, il avait très<br />

peu connu Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918) mais l’écouter<br />

lire à voix haute ses poèmes lui avait fait reconnaître une âme<br />

sœur. Apollinaire (Kostrowitsky de son vrai nom) était italopolonais<br />

de naissance et son amour de Paris avait toute<br />

l’int<strong>en</strong>sité d’un amour de converti. Montparnasse est une<br />

séduisante évocation nostalgique du sud parisi<strong>en</strong> dont<br />

l’appr<strong>en</strong>ti-poète ress<strong>en</strong>t, <strong>le</strong>s yeux écarquillés, toute la magie.<br />

Pou<strong>le</strong>nc mit quatre ans à assemb<strong>le</strong>r cette pièce, mais <strong>le</strong><br />

déroulé coulant de la musique, épousant <strong>le</strong>s t<strong>en</strong>dres méandres<br />

du poème, est un triomphe : il a trouvé la mélodie et l’harmonie<br />

à même de suggérer et la nostalgie des temps révolus de la<br />

jeunesse du poète à Montparnasse et <strong>le</strong> sourire chagrin de ce<br />

dernier face au jeune homme gauche qu’il était alors—un peu<br />

bête et trop blond.<br />

Hyde Park nous transporte à Londres et forme, avec sa<br />

jumel<strong>le</strong> parisi<strong>en</strong>ne, un g<strong>en</strong>re de « Conte des deux vil<strong>le</strong>s » <strong>en</strong><br />

chanson même si, la concernant, Pou<strong>le</strong>nc savait avoir fait<br />

beaucoup, beaucoup mieux. « C’est une mélodie tremplin, ri<strong>en</strong><br />

de plus », écrivit-il, signifiant par là qu’il la voulait comme<br />

un tremplin rapide et efficace vers une mélodie davantage<br />

substantiel<strong>le</strong>. La vignette marquée fol<strong>le</strong>m<strong>en</strong>t vif et furtif<br />

évoque <strong>le</strong>s drô<strong>le</strong>s de prêcheurs de Hyde Park Corner, <strong>le</strong>s<br />

nurses réprobatrices faisant pr<strong>en</strong>dre l’air à ceux qui <strong>le</strong>ur sont<br />

confiés et la purée de pois qui empêche <strong>le</strong>s policiers d’y voir<br />

assez pour trousser quelqu’un. En fait de mythologiques, <strong>le</strong>s<br />

yeux des cyclopes roux ne sont ri<strong>en</strong> d’autre que la lueur des<br />

pipes.<br />

Chez Pou<strong>le</strong>nc comme chez Apollinaire, la verve peut tojours<br />

<strong>le</strong> céder brusquem<strong>en</strong>t à la plus profonde émotion, B<strong>le</strong>uet, <strong>le</strong><br />

titre de la mélodie suivante, est un t<strong>en</strong>dre diminutif de « b<strong>le</strong>u »,<br />

terme argotique désignant un jeune soldat. Ce soldat va<br />

mourir ; à cinq heures, il faut quitter <strong>le</strong>s tranchées pour<br />

affronter <strong>le</strong> feu <strong>en</strong>nemi. Mais il n’y a ni héroïsme ni patriotisme<br />

exacerbés dans cette mélodie. Et Pou<strong>le</strong>nc d’écrire :<br />

« L’humilité, qu’il s’agisse de la prière ou du sacrifice d’une<br />

vie, c’est ce qui me touche <strong>le</strong> plus … l’âme s’<strong>en</strong>vo<strong>le</strong> après un<br />

long regard jeté sur ‘la douceur d’autrefois’. » C’est l’unique<br />

mélodie de Pou<strong>le</strong>nc pour ténor et el<strong>le</strong> requiert plus la voix d’un<br />

Cu<strong>en</strong>od que d’un Gigli ; pour dire <strong>le</strong> jeune homme de vingt ans,<br />

<strong>le</strong> malheureux gâchis de sa vie et ce dernier long regard, la voix<br />

du narrateur doit avoir un timbre particulier, éthéré. Apollinaire<br />

rédigea ce poème <strong>en</strong> 1917, un an <strong>en</strong>viron avant de mourir des<br />

suites de ses b<strong>le</strong>ssures de guerre.<br />

Autre adieu émouvant, Voyage fut éga<strong>le</strong>m<strong>en</strong>t mis <strong>en</strong><br />

musique dans un contexte de guerre. Qui d’autre que Pou<strong>le</strong>nc<br />

eût pu déchiffrer ce Calligramme (comme Apollinaire appelait<br />

ses expérim<strong>en</strong>tations de typographie pictura<strong>le</strong>—et celui-ci<br />

a une mise <strong>en</strong> page particulièrem<strong>en</strong>t déroutante) et produire<br />

une mélodie d’une tel<strong>le</strong> lucidité fluide ? Le climat est ici à<br />

l’acceptation résignée—<strong>le</strong>s séparations <strong>en</strong> temps de guerre<br />

sont souv<strong>en</strong>t des adieux à jamais ; <strong>le</strong> voyage de Dante<br />

dans <strong>le</strong>s sphères inferna<strong>le</strong>s est sans retour. Comme dans<br />

Montparnasse, nous assistons à une réaction presque<br />

chimique quand la musique de Pou<strong>le</strong>nc r<strong>en</strong>contre la poésie dite<br />

surréaliste d’Apollinaire et de Paul Éluard (1895–1952).<br />

23

Pou<strong>le</strong>nc écrivit : « Si l’on mettait sur ma tombe : Cigît Francis la Sonate <strong>en</strong> si bémol mineur de Chopin) et Hier étant des<br />

Pou<strong>le</strong>nc, <strong>le</strong> musici<strong>en</strong> d’Apollinaire et d’Éluard, il me semb<strong>le</strong> textes de son amie. Hier est la première mélodie pour laquel<strong>le</strong><br />

que ce serait mon plus beau titre de gloire. » Avec son Pou<strong>le</strong>nc recourt à la veine lyrique qui marquera tant de ses<br />

intellig<strong>en</strong>ce innée de <strong>le</strong>ur œuvre, il illumine ces vers parfois meil<strong>le</strong>ures chansons. Quand il la composa <strong>en</strong> 1931, ses fol<strong>le</strong>s<br />

insondab<strong>le</strong>s qui, par <strong>le</strong>ur force et <strong>le</strong>ur dignité, garantiss<strong>en</strong>t, années étai<strong>en</strong>t derrière lui. Dans cette mélodie, <strong>le</strong> pitre et <strong>le</strong><br />

<strong>en</strong> retour, à son lyrisme de ne jamais verser dans la gueux <strong>le</strong> montre capab<strong>le</strong> de mélancolie, et il choisit <strong>le</strong> sty<strong>le</strong><br />

s<strong>en</strong>tim<strong>en</strong>talité. C’est comme si un merveil<strong>le</strong>ux marché avait d’une boîte parisi<strong>en</strong>ne <strong>en</strong>fumée (plane <strong>le</strong> fantôme de Marie<br />