Tainos: Arte y Sociedad

por Manuel A. Garcia Arevalo

por Manuel A. Garcia Arevalo

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

1<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD

2<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD

3<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD

08 4<br />

LOS TAÍNOS, TAINOS ARTE Y SOCIEDAD

5<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Texto<br />

MANUEL A. GARCÍA ARÉVALO<br />

Fotografía<br />

VÍCTOR SILADI

Taínos, arte y sociedad<br />

Manuel A. García Arévalo<br />

© Banco Popular Dominicano, 2019<br />

Fotografía<br />

Víctor Siladi<br />

Coordinación y producción editorial<br />

Clarisa Carmona<br />

Corrección<br />

Clara Dobarro<br />

Traducción al inglés<br />

Ana Martínez<br />

6<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Diseño y arte final<br />

Jimmy González y Fractal Studio<br />

Posproducción fotográfica<br />

Damian Siladi<br />

Ilustraciones taínas:<br />

Pedro L. Díaz Alvarado<br />

Tratamiento digital ilustraciones páginas: 47, 58, 60, 100, 128, 139.<br />

StefanDMC<br />

Imágenes páginas: 31, 36, 39, 42, 50, 65, 66, 168.<br />

© Alamy.es<br />

Imágenes páginas: 25, 37, 43.<br />

© Art Resource<br />

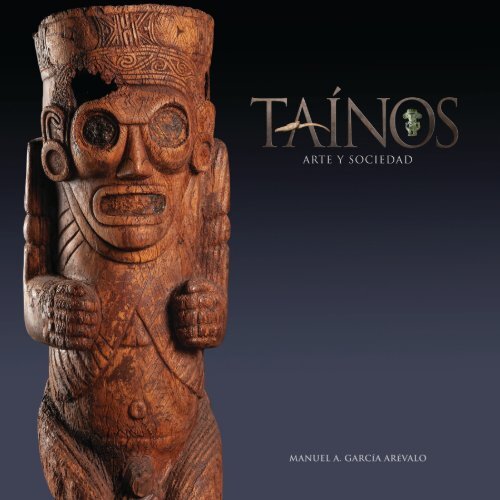

Portada<br />

Ídolo de la cohoba. © FGA<br />

Primera edición, 2019<br />

ISBN 978-9945-8683-7-1<br />

Impresión<br />

Amigos del Hogar<br />

Santo Domingo, D. N.<br />

República Dominicana, 2019

Dedicado a:<br />

José Antonio Caro Álvarez<br />

Primer director del Museo del Hombre Dominicano.<br />

Marcio Veloz Maggiolo<br />

Por su valiosa contribución a la arqueología nacional.<br />

7<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD

8<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD

Estudiando y valorizando el pasado, podremos comprender<br />

y evaluar con mayor conciencia al presente, y tenderemos a<br />

fomentar un futuro mejor para las generaciones del mañana.<br />

Emile Boyrie de Moya<br />

La riqueza arqueológica de la Española o Santo Domingo,<br />

dejada en su suelo por una densa población indígena, hacen de<br />

esta Isla la región más apropiada para estudiar la cultura taína<br />

en su más alto desarrollo y apreciar su variado ajuar tan rico en<br />

manifestaciones artísticas admirables.<br />

9<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

René Herrera Fritot

10<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD

Presentación<br />

Es ampliamente aceptada la idea de la necesidad de conocer<br />

el pasado para tener un mayor entendimiento del presente<br />

y una clara proyección del futuro. De ahí el valor que cobra el<br />

saber interpretar de dónde venimos para comprendernos y<br />

comprender mejor el entorno en el que nos movemos, así como<br />

para identificar las oportunidades con las que contamos.<br />

En ese sentido, este nuevo libro que auspiciamos como<br />

organización financiera bajo el título Taínos, arte y sociedad, de la<br />

autoría del destacado historiador y empresario Manuel A. García<br />

Arévalo, se constituye en una contribución notable que arroja luz<br />

sobre nuestras raíces aborígenes y nos permite proyectarnos en<br />

el conjunto de naciones con una idiosincrasia particular.<br />

Aventurarnos a conocer estos orígenes ancestrales nos ayuda a<br />

concebir y diseñar cómo queremos presentarnos ante el mundo,<br />

de forma diferenciada, aprovechando las singularidades que nos<br />

definen.<br />

Ese es el impulso que está detrás de esta publicación<br />

institucional, en la que García Arévalo traza con profundo<br />

conocimiento las líneas de nuestro pasado aborigen, que forman<br />

una parte inequívocamente significativa de nuestra herencia.<br />

Como institución financiera que posee el mérito de ser la mayor<br />

financiadora del turismo, nos parece oportuno resaltar este tipo<br />

de aportes porque sobre ellos podemos recrear una imagen<br />

propia en el mercado nacional e internacional.<br />

Aquello que hoy conocemos en la República Dominicana como<br />

la cultura taína fue el resultado de la integración de múltiples<br />

grupos indígenas antillanos a través de los siglos, creándose<br />

un primer sustrato que cimentó la base sobre la que se fue<br />

construyendo nuestra identidad nacional: mestiza, diversa y, por<br />

tal razón, exuberante.<br />

Esta obra ofrece una mirada a las costumbres de los aborígenes, a<br />

su expresión artística y ritual; es un viaje al interior de lo que somos.<br />

La dominicanidad actual no se inició con la llegada del mundo<br />

occidental a las Américas, sino que comenzó con esas primeras<br />

culturas que se fusionaron con las provenientes de Europa y África,<br />

conformando un nuevo ser que continuó expandiéndose con<br />

mayor rapidez desde ese entonces. Los hallazgos arqueológicos<br />

y documentales sobre los cuales se ha fundamendado esta obra<br />

cuentan la historia identitaria del dominicano.<br />

El turismo cultural es un nicho que ha permitido a múltiples<br />

naciones del mundo destacarse como destino. En los últimos años<br />

va de la mano con el turismo sostenible, creando lo que ahora se<br />

conoce bajo la denominación de «turismo naranja», una tendencia<br />

mundial que vincula la cultura con la economía.<br />

Esta nueva visión del turismo genera valor a través de una<br />

dinámica que engloba el patrimonio cultural y la industria creativa<br />

para diseñar experiencias que respondan a lo que buscan los<br />

turistas del siglo XXI: actividades genuinas que los conecten con<br />

la cultura y la identidad del país y las poblaciones que visitan.<br />

Vemos, pues, que estos orígenes que surgen de la mezcla de<br />

nuestros pueblos indígenas antillanos son un patrimonio cultural<br />

a partir del cual podemos crear una narrativa única y desarrollar<br />

una gestión de experiencias particulares para el turista.<br />

11<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Potiza o recipiente para líquidos. (MHD)

La publicación, más allá de su lectura, sumerge al lector en un<br />

mundo de realidades virtuales aumentadas, permitiéndole<br />

experimentar con múltiples escenarios y ejemplos de la cultura<br />

taína a través de varios sentidos.<br />

A esta propuesta interactiva, única hasta el momento en el<br />

panorama editorial dominicano, se puede acceder mediante<br />

la aplicación MIRA (Mi Realidad Aumentada), instalada en<br />

dispositivos móviles. Con ella, a través de una pantalla, los<br />

interesados podrán interactuar con ese mundo ancestral mediante<br />

una narrativa tecnológicamente innovadora con tan solo hacer un<br />

clic sobre las imágenes destacadas al efecto.<br />

Nos sentimos, pues, sumamente complacidos con esta nueva<br />

entrega editorial y multimedia, con la cual evidenciamos nuestro<br />

compromiso con la proyección de la identidad dominicana,<br />

más allá de los hermosos recursos naturales de nuestras costas<br />

y paisajes de interior, explorando los valores culturales que<br />

contribuyen a fortalecer nuestro presente y nuestro futuro.<br />

Además, como cada publicación institucional del Popular, esta<br />

obra cuenta con el acompañamiento de un documental que<br />

incluye interesantes entrevistas y visitas a lugares emblemáticos<br />

de la cultura taína en el territorio nacional.<br />

Christopher Paniagua<br />

Presidente ejecutivo<br />

Banco Popular Dominicano<br />

12<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Cemí de tres puntas o trigonolito con aplicaciones de concha en la dentadura. (MHAA, UPR)

13<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Pájaro sobre una tortuga. Presenta una proyección vertical para colocar los polvos alucinógenos de la cohoba.<br />

©The Trustees of the British Museum, BM Am, MI.168

14<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD

Agradecimientos<br />

La publicación de esta obra sobre nuestro formidable acervo<br />

arqueológico prehispánico ha sido posible por el amplio<br />

patrocinio recibido del Banco Popular Dominicano, institución que<br />

en los últimos años ha contribuido notablemente a enriquecer la<br />

bibliografía nacional.<br />

En ese sentido, quiero expresar mi gratitud a Manuel A. Grullón,<br />

presidente del Consejo de Administración del Grupo Popular,<br />

al igual que a Manuel E. Jiménez y Christopher Paniagua,<br />

presidentes ejecutivos del Grupo Popular y del Banco Popular,<br />

respectivamente. Asimismo, a los demás ejecutivos y técnicos del<br />

Banco Popular por su cooperación con este proyecto editorial; en<br />

especial, a José Mármol, vicepresidente ejecutivo de Relaciones<br />

Públicas y Comunicaciones; Esteban Martínez-Murga, gerente<br />

de la División de Comunicaciones Corporativas; José Montás<br />

Frómeta, gerente de la División de Productos Audiovisuales, y<br />

Eleni de Castro, gerente de Publicaciones Institucionales.<br />

Mi profundo agradecimiento va también para las siguientes personas<br />

e instituciones nacionales, cuya generosa colaboración fue<br />

un estímulo para que esta obra saliera adelante:<br />

Al ministro de Cultura, arquitecto Eduardo Selman Hasbún; a<br />

Ana María Conde Vitores, directora general de Museos de la<br />

República Dominicana, y al arquitecto Christian Martínez, director<br />

del Museo del Hombre Dominicano.<br />

Al doctor Marcio Veloz Maggiolo, cuyos aportes al estudio<br />

de la prehistoria me han permitido ampliar el horizonte de<br />

mis conocimientos sobre las culturas aborígenes del Caribe.<br />

Y al historiador y arqueólogo Bernardo Vega Boyrie, por su<br />

constante cooperación. A mis dilectas amigas Dominique<br />

Bluhdorn, presidenta de la Fundación Centro Cultural Altos de<br />

Chavón, y María Amalia León Cabral, presidenta de la Fundación<br />

Eduardo León Jimenes, quienes pusieron a mi disposición<br />

las representativas colecciones que se conservan en el Museo<br />

Arqueológico de Altos de Chavón, en La Romana, y en el Centro<br />

Cultural Eduardo León Jimenes, en Santiago de los Caballeros.<br />

Asimismo, a los coleccionistas Nicole y Pierre Domino, Betty<br />

e Isaac Rudman, al ingeniero Wilton Khoury y al doctor Nonín<br />

Galán.<br />

Por igual, deseo agradecer al excelente equipo de profesionales<br />

del Museo del Hombre Dominicano por la asistencia<br />

continua que nos han brindado. En especial, cabe destacar la<br />

inestimable contribución del doctor Jorge Ulloa Hung, director<br />

del Departamento de Arqueología, quien hizo importantes<br />

observaciones al texto y proporcionó muchas de las referencias<br />

bibliográficas. También, al doctor Renato Rímoli, director del<br />

Departamento de Paleobiología, por sus señalamientos en torno<br />

a la flora y la fauna de la época; al arqueólogo Adolfo López<br />

Belando y al espeleólogo Domingo Abreu por facilitarnos varias<br />

de las fotografías de petroglifos y pictografías que se muestran<br />

en la obra.<br />

Quiero reconocer, a su vez, a las instituciones museográficas<br />

y a los coleccionistas que, desde el exterior, me ofrecieron su<br />

colaboración. A su amabilidad se deben muchas de las imágenes<br />

de las piezas arqueológicas que se incluyen en este libro. A<br />

todos ellos, gracias. Mención especial merece mi buen amigo el<br />

doctor André Delpuech, director del Museo del Hombre de París,<br />

quien con su gran conocimiento de las culturas aborígenes de las<br />

Antillas nos orientó sobre la existencia de los objetos taínos que<br />

se conservan en los museos de Europa y Estados Unidos. Y a Paz<br />

Núñez Regueiro, jefa de la Unidad Patrimonial de las Colecciones<br />

de las Américas del Museo Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac.<br />

Al British Museum, de Londres; Museo de América, de Madrid;<br />

Il Museo di Antropologia e Etnologia, de Florencia; Museo de<br />

Historia Natural, de Argentina; Museum für Völkerkunde, de<br />

15<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Ídolo de madera con figura antropomorfa en relieve. (MHD)

16<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Viena; Museo Nacional de Antropología, de México; Museo di<br />

Antropologia ed Etnografia, Università di Torino; Smithsonian<br />

Institution, Metropololitan Museum of Art y El Museo del Barrio,<br />

de Nueva York. Y a los coleccionistas Antonio y Ana Casanovas,<br />

Guy Ladrière, Vincent y Margaret Fay, y David Bernstein, así como<br />

a la colección Ziff y al fotógrafo Justin Kerr.<br />

En Puerto Rico, debo destacar la contribución de la doctora<br />

Flavia Marichal Lugo y de Chakira T. Santiago Gracia, directora<br />

y registradora en jefe, respectivamente, del Museo de Historia,<br />

Antropología y <strong>Arte</strong> de la Universidad de Puerto Rico. A la<br />

doctora Yvonne Narganes Storde, arqueóloga del Centro de<br />

Investigaciones Arqueológicas de la Universidad de Puerto Rico,<br />

Recinto Río Piedras. Por igual, al doctor Eduardo Rodríguez<br />

Vásquez, presidente de la Junta de Síndicos, y la rectora Amalia<br />

Alcina Orozco, ambos del Centro de Estudios Avanzados de<br />

Puerto Rico y el Caribe, así como a las autoridades del Instituto<br />

de Cultura Puertorriqueña. Asimismo, expreso mi gratitud a los<br />

investigadores Francisco Moscoso, Sebastián Robiou y Daniel<br />

Shelley, y al fotógrafo Héctor Méndez Caratini. Por otra parte,<br />

agradezco la cooperación recibida en Cuba de los arqueólogos<br />

Lourdes Domínguez y Roberto Valcárcel, y del doctor Armando<br />

Rangel, director del Museo Antropológico Montané de la<br />

Universidad de La Habana.<br />

La realización de esta obra debe mucho a la doctoranda Clarisa<br />

Carmona, que con gran desvelo y entusiasmo asumió este proyecto<br />

editorial como si fuera propio, ofreciendo generosamente su<br />

tiempo y su dedicación sin miramiento de horario para que la<br />

publicación saliera adelante. Tenemos, por igual, una deuda de<br />

gratitud con el fotógrafo de la obra, Víctor Siladi, quien con su<br />

destreza profesional se esmeró en realizar y captar con extrema<br />

minuciosidad los rasgos iconográficos de un amplio repertorio<br />

de imágenes precolombinas, así como por el diseño artístico de<br />

la obra. De igual forma resaltamos la labor y el entusiasmo del<br />

diseñador gráfico Jimmy González.<br />

Oleaga y Ana Cristina Contreras por la paciente labor al digitar con<br />

esmero y pulcritud los textos que se incluyen en esta publicación.<br />

Igualmente, valoramos los comentarios y la corrección de estilo<br />

de Clara Dobarro, al igual que la colaboración de Ana Martínez,<br />

Lisette Vega de Purcell por el cuidado y profesional trabajo en la<br />

traducción del texto a inglés. También reconocemos la labor de<br />

Pedro L. Díaz A., por las nítidas ilustraciones de la sociedad taína.<br />

Le agradezco de manera muy especial a mi esposa Francis, quien<br />

siempre ha sido un gran estímulo en mi quehacer intelectual,<br />

acompañándome en mis viajes de prospección arqueológica y en<br />

la búsqueda de las referencias documentales y bibliográficas. Lo<br />

mismo que a nuestros hijos y nietos, a quienes hemos sustraído<br />

parte del tiempo de convivencia familiar para dedicarlo a la<br />

redacción y confección de esta publicación.<br />

Finalmente, es importante señalar que Taínos, arte y sociedad<br />

busca llegar al mayor público posible; de ahí que nos hemos<br />

alejado de excesivos tecnicismos para que sea comprensible<br />

a todos los lectores y cumpla su propósito de constituir un<br />

puente de unión entre las generaciones de hoy y del mañana<br />

con las culturas del ayer. Pese a esto, hemos procurado mantener<br />

estrictos cánones científicos para que, al mismo tiempo, sea del<br />

interés de los especialistas en la cultura y el arte de los taínos.<br />

Manuel A. García Arévalo<br />

Otras personas a quienes debemos reconocer por su valiosa<br />

contribución son Betania Reyes, curadora de la Sala de <strong>Arte</strong><br />

Prehispánico de la Fundación García Arévalo, así como Rosa Elba<br />

Vasija tallada en hueso con asas bicéfalas antropomorfas. (MHD)

17 09<br />

LOS TAÍNOS, TAINOS ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Vaso efigie antropomorfo. (MHD)

18<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Dúho o asiento ceremonial en cuyo espaldar aparecen dos figuras simétricas estilizadas y<br />

motivos geométricos incisos. (MHD)

Contenido<br />

11 Presentación<br />

15 Agradecimientos<br />

21 Introducción<br />

23 Los indígenas antillanos primeras reseñas históricas<br />

37 El estudio del pasado<br />

45 El poblamiento de las Antillas<br />

47 Los protoarcaicos. artefactos de pedernal<br />

57 Los arcaicos. Lítica pulida y artefactos de concha<br />

71 El manglar como medio de subsistencia<br />

73 El período agroalfarero<br />

73 Los igneris o saladoides<br />

77 La cultura huecoide<br />

81 Los ostionoides o subtaínos<br />

86 Meillacoides y macoriges<br />

88 Los factores de cambio<br />

90 La evolución de los agroalfareros. Nuevas aproximaciones<br />

95 La cultura taína<br />

97 Quiénes eran los taínos<br />

105 Las actividades productivas<br />

105 La agricultura<br />

109 Las plantas comestibles<br />

117 Árboles maderables y medicinales<br />

118 La caza<br />

120 La pesca<br />

123 Navegación y comercio<br />

125 Organización social y política<br />

127 El cacique<br />

129 Los símbolos de poder<br />

137 Los cacicazgos<br />

140 Nitaínos y naborías<br />

141 Los behiques o buhitihos: éxtasis y curación<br />

142 El «vuelo mágico» y su connotación ornitomorfa<br />

142 Efectos terapéuticos de la dieta<br />

143 El simbolismo del esqueleto<br />

144 Las viviendas<br />

146 Las hamacas<br />

148 El juego de pelota<br />

152 Los bailes o areitos<br />

159 Los instrumentos musicales<br />

161 Las maracas monóxilas<br />

165 La sonoridad de los cascabeles<br />

167 Mitología y religión<br />

167 Creencias mitológicas<br />

171 Prácticas funerarias<br />

173 El mundo de los desaparecidos<br />

174 Los espíritus alados de la muerte<br />

175 El murciélago y las opías<br />

178 Las lechuzas, mensajeras del Coaybay<br />

182 El culto a los antepasados<br />

184 El cemí de algodón<br />

188 El éxtasis de la cohoba<br />

193 Los ídolos de la cohoba<br />

201 Los dúhos o asientos ceremoniales<br />

211 Los instrumentos de la cohoba<br />

211 Inhaladores y espátulas vómicas<br />

221 Los majadores o manos de mortero<br />

227 Íconos de tres puntas<br />

239 Cabezas efigies<br />

241 Cabezas trilobuladas<br />

243 Aros líticos y piedras acodadas<br />

249 La industria lapidaria<br />

254 La sutileza de la concha y el hueso<br />

265 El barro hecho arte<br />

279 La cerámica pintada<br />

282 Los vasos efigies<br />

293 La alfarería criolla<br />

295 El lenguaje de los símbolos y los signos<br />

302 Las voces de las cavernas<br />

311 Trascendencia del arte taíno<br />

317 El legado indígena<br />

325 <strong>Tainos</strong>, Art and Society<br />

382 Siglas utilizadas<br />

384 Notas bibliográficas<br />

19<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD

20<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD

Introducción<br />

Al hablar del pasado indígena de las Grandes Antillas, generalmente<br />

solo se menciona la existencia de la denominada<br />

«cultura taína». Sin embargo, esta cultura no fue la primera ni<br />

la única en poblar el entorno antillano. El Caribe insular, siglos<br />

antes de la aparición de los llamados «taínos», estuvo habitado<br />

por grupos humanos de características sociales, culturales<br />

y económicas muy diferentes; no obstante, sus conocimientos<br />

y experiencias, además de algunas de sus herramientas, se integraron<br />

y perpetuaron a través de las culturas indígenas que<br />

posteriormente habitaron ese espacio geográfico.<br />

Desde ese punto de vista, el desarrollo de la cultura taína no<br />

debe ser vinculado solamente a las migraciones arahuacas desde<br />

Sudamérica. Más bien corresponde al resultado de procesos<br />

milenarios mucho más complejos que tuvieron lugar en el<br />

contexto de las islas del Caribe, en especial en Puerto Rico y<br />

la Española. Este aspecto es quizá la razón por la que algunos<br />

investigadores consideran la sociedad taína como el primer ensayo<br />

de la mezcla cultural que hoy define el perfil caribeño. 1<br />

21<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Esos procesos evolutivos trajeron aparejada la formación de un<br />

mosaico de culturas indígenas en las cuales es posible percibir<br />

un repertorio de rasgos que las representan y caracterizan desde<br />

el punto de vista social, religioso, político y económico. 2 Es<br />

esto lo que puede definirse como «lo taíno», sin excluir una diversidad<br />

de manifestaciones y variaciones locales o regionales<br />

que apenas fueron captadas por los cronistas de Indias. Corresponde<br />

a la arqueología y otras disciplinas científicas auxiliares<br />

la misión de explicar lo acontecido en el pasado prehispánico<br />

con el objeto de conocer y valorar las raíces ancestrales que<br />

contribuyen a formar nuestra identidad nacional.<br />

Respaldo de los ídolos gemelos de la cohoba, mostrando la imagen de una lechuza. Smithsonian Institution.<br />

Espátula vómica tallada en costilla de manatí con figura antropomorfa en posición ceremonial. (FGA)

22<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD

Los indígenas antillanos<br />

Primeras reseñas históricas<br />

A la llegada de los europeos, a finales del siglo XV, las islas<br />

antillanas estaban pobladas por diversas culturas. La novedad<br />

de encontrar gentes de lenguas extrañas y «exóticas costumbres»<br />

en las tierras del que posteriormente fue llamado Nuevo<br />

Mundo sería el hallazgo más sorprendente, y el más reconocido,<br />

del periplo descubridor del almirante Cristóbal Colón.<br />

El primer contacto entre europeos e indígenas se produjo el<br />

12 de octubre de 1492 cuando los descubridores se encontraron<br />

con los llamados «lucayos» al arribar a la isla Guanahaní,<br />

localizada en el archipiélago de las Bahamas y bautizada con<br />

el nombre de San Salvador por los españoles, quienes también<br />

se refieren a estas últimas como Lucayas, denominación<br />

que deriva, precisamente, del nombre de sus primeros habitantes.<br />

Sobre este episodio nos dice el Almirante en el diario<br />

de navegación de su primer viaje:<br />

[…] muy bien hechos, de muy fermosos cuerpos y muy buenas<br />

caras, de los cabellos gruessos cuasi como sedas de cola de cavallos<br />

e cortos. Los cabellos traen por ençima de las çejas, salvo<br />

unos pocos detrás que traen largos, que jamás cortan. D’ellos se<br />

pintan de prieto, y ellos son de la color de canarios, ni negros<br />

ni blancos, y d’ellos se pintan de blanco y d’ellos de colorado y<br />

d’ellos de lo que fallan; y d’ellos se pintan las caras, y d’ellos todo<br />

el cuerpo, y d’ellos solo los ojos, y d’ellos solo la nariz. 3<br />

Al día siguiente agrega:<br />

[…] todos de buena estatura, gente muy fermosa y […] todos de<br />

la frente y cabeça muy ancha, más que otra generación que fasta<br />

aquí aya visto; y los ojos muy fermosos y no pequeños; y ellos<br />

ninguno prieto, salvo de la color de los canarios. 4<br />

Atento a las novedades que halla a su paso por las nuevas tierras,<br />

Colón se convierte en un agudo observador de la fisonomía<br />

y las costumbres de los habitantes de las islas antillanas,<br />

a quienes llamó indios por creer que había llegado a la India.<br />

Sus descripciones sobre los indígenas, hechas con sobriedad<br />

y alto nivel de detalle, constituyen un documento de gran valor<br />

etnográfico, en especial, las relativas a los rasgos físicos y<br />

culturales de estas poblaciones (color de piel, tipo de cabello,<br />

deformación de la frente, decoración corporal, etc.). 5<br />

Al llegar a la isla de Cuba, a la que llamó Juana en honor a la<br />

hija de los Reyes Católicos, Colón refiere: «Esta gente […] es<br />

de la misma calidad y costumbre de los otros hallados. […]<br />

Toda la lengua también es una y todos amigos […] Y así andan<br />

también desnudos como los otros». 6 En referencia a la desnudez<br />

de los aborígenes, agrega:<br />

Son gente […] muy sin mal ni de guerra, desnudos todos, hombres<br />

y mugeres, como sus madres los parió. Verdad es que las<br />

mugeres traen una cosa de algodón solamente, tan grande que<br />

le cobija su natura y no más. Y son ellas de muy buen acatamiento,<br />

ni muy negro[s] salvo menos que Canarias. 7<br />

En cuanto a sus viviendas, observa: «Eran hecha(s) a manera<br />

de alfaneques muy grandes, y pareçían tiendas en real, sin<br />

concierto de calles, sino una acá y otra acullá y de dentro muy<br />

barridas y limpias y sus adereços muy compuestos. Todas son<br />

de ramos de palma muy hermosas». 8<br />

23<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Grabado alusivo al Descubrimiento de América. Histoire de l’Isle Espagnole ou de S. Domingue, de Pierre François Xavier de Charlevoix (1730-31).

24<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Al descubridor de América le sorprende la habilidad que tenían<br />

los indios para navegar en sus ágiles embarcaciones:<br />

Ellos vinieron a la nao con almadías [canoas], que son hechas del<br />

pie de un árbol como un barco luengo y todo de un pedaço, y labrado<br />

muy a maravilla según la tierra, y grandes, en que en algunas<br />

venían 40 y 45 hombres, y otras más pequeñas, fasta aver d’ellas<br />

en que venía un solo hombre. Remavan con una pala como de fornero,<br />

y anda a maravilla, y si se le trastorna, luego se echan todos a<br />

nadar y la endereçan y vazían con calabaças que traen ellos. 9<br />

Colón alude a los sencillos adornos de oro usados por los indios,<br />

que refuerzan sus expectativas de encontrar este precioso<br />

metal con el objeto de alcanzar el éxito financiero de su empresa<br />

descubridora. Sobre el intercambio o trueque establecido, el<br />

propio Almirante refiere que los españoles empleaban cuentas<br />

de vidrio, cascabeles, sortijas de latón, fragmentos de cerámica<br />

y otros abalorios que los indígenas aceptaban de buena gana,<br />

«como algo venido del cielo».<br />

En la costa norte de la isla de Bohío, a la que luego bautizó Colón<br />

como Española, naufragó la nave Santa María, que recibió<br />

el auxilio de los indígenas del cacicazgo de Marién, encabezado<br />

por Guacanagarix. El solidario gesto del cacique motivó al<br />

Almirante a escribir en su Diario:<br />

Son gentes de amor y sin cudiçia y convenibles para toda la cosa,<br />

que certifico a Vuestras Altezas que en el mundo creo no ay mejor<br />

gente ni mejor tierra. Ellos aman a sus próximos como sí mismos, y<br />

tienen una habla la más dulçe del mundo, y mansa y siempre con<br />

risa. Ellos andan desnudos, hombres y mugeres, como sus madres<br />

los parieron, mas crean Vuestras Altezas que entre sí tienen costumbres<br />

muy buenas, y el rey muy maravilloso estado, de una cierta<br />

manera tan continente qu’es plazer de verlo todo, y la memoria que<br />

tienen, y todo quieren ver, y preguntan qué es y para qué. 10<br />

Con la madera de la Santa María, Colón construyó el fuerte<br />

de la Navidad, a cuyo cuidado dejó 39 hombres. Allí hizo una<br />

demostración del poderío de las armas españolas tronando<br />

las bombardas, y estableció una alianza con el cacique Guacanagarix,<br />

a quien le ofreció protección frente a los canibas o<br />

caribes, «que debe ser gente arriscada, pues andan por todas<br />

estas islas y comen la gente que puede haver». 11 El acuerdo<br />

establecido entre Colón y Guacanagarix, un pacto de amistad<br />

que en lengua indígena se denominaba guatiao, se realizó<br />

ante la presencia de otros caciques de la zona y de los hermanos<br />

y familiares del cacique de Marién. La ceremonia, que incluía<br />

intercambio de regalos y otros artículos de uso personal,<br />

también conllevaba el intercambio recíproco de los nombres<br />

entre los dos contrayentes, como gesto de alianza y paz. 12<br />

Los apuntes de Colón constituyen textos precursores de la<br />

etnografía en América al describir muchas de las características<br />

de los pueblos que encontró a su paso por las Antillas.<br />

Algunas de esas descripciones han sido objeto de estudio<br />

por parte de las actuales investigaciones arqueológicas, que<br />

han confirmado importantes correlaciones culturales entre los<br />

indígenas que ocupaban gran parte de la Española, Puerto<br />

Rico y el extremo oriental de Cuba, además de extensas interacciones<br />

socioculturales entre los grupos que habitaban las<br />

diferentes islas antillanas. 13

Naufragio de la carabela Santa María frente al cacicazgo de Marién. Pintura de Francesc Vall.<br />

25<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Mapa de la costa noroeste de la Española atribuido a Cristóbal Colón. Aparece en su Diario.

26<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD

Al referirse a la naturaleza tropical de la Española, Colón exalta<br />

con entusiasmo la feracidad del suelo, el verdor y la hermosura<br />

de su flora, la exuberancia de sus sierras y montañas, los<br />

abundantes ríos y la suave brisa, lo que lo lleva a exclamar: «es<br />

la más hermosa cosa del mundo», y a asegurar a sus altezas:<br />

«[…] qu’estas tierras son en tanta cantidad buenas y fértiles, y<br />

en especial estas d’esta isla Española, que no ay persona que<br />

lo sepa dezir y nadie lo puede creer si no lo viese». Igualmente,<br />

destaca el carácter de sus gentes, haciendo hincapié en su<br />

ingenuidad, mansedumbre y desprendimiento:<br />

La gente d’esta isla y de todas las otras que he fallado y havido<br />

ni aya havido noticia, andan todos desnudos, hombres y mugeres,<br />

así como sus madres los paren, haunque algunas mugeres<br />

se cobijan un solo lugar con una foia de yerva o una cosa de<br />

algodón que para ello fazen. Ellos no tienen fierro ni azero ni<br />

armas, ni son para ello; no porque no sea gente bien dispuesta<br />

y de fermosa estatura, salvo que son muy temerosos a maravilla.<br />

No tienen otras armas salvo las armas de las cañas cuando están<br />

con la simiente, a la cual ponen al cabo un palillo agudo, e no<br />

osan usar de aquellas, que muchas vezes me ha acaecido embiar<br />

a tierra dos o tres hombres a alguna villa para haver fabla, i salir a<br />

ellos d’ellos sin número, y después que los veían llegar fuían [...] 14<br />

27<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

El asombro que traslucen las idealizadas anotaciones hechas<br />

por Colón contribuyó a crear entre los humanistas europeos<br />

una visión idílica sobre el estado natural en que vivían los indígenas<br />

antillanos, a quienes el mito del «buen salvaje» les<br />

atribuyó una inocencia propia de la edad de oro o del paraíso<br />

terrenal, idea reiterada a través de los siglos que dio lugar al<br />

pensamiento utópico.<br />

Adorno batraciforme de concha de la cultura taína. (MHD)<br />

Paisaje de Valle Nuevo, Cordillera Central, RD. ©Ricardo Briones

Al arribar a la península de Samaná, el Almirante entra en contacto<br />

con los ciguayos, que, según sus descripciones, diferían de los<br />

indígenas que hasta entonces había conocido por su apariencia<br />

y actitud belicosa:<br />

[...] El cual diz que era muy disforme en el acatadura más que otros<br />

que oviese visto: tenía el rostro todo tiznado de carbón, puesto que<br />

en todas partes acostumbran de se teñir de diversas colores; traía<br />

todos los cabellos muy largos y encogidos y atados atrás, y después<br />

puestos en una redezilla de plumas de papagayos, y él así desnudo<br />

como los otros. 15<br />

28<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Además, tenían arcos que «eran tan grandes como los de Francia<br />

e Inglaterra», 16 diferenciándose en esto de los taínos, que habitaban<br />

otras áreas de la Española. Colón los asocia con los caribes:<br />

«[…] creía que eran los de Carib y que comiesen los hombres, […]<br />

y que si no son de los caribes, al menos deven de ser fronteros y<br />

de las mismas costumbres y gente sin miedo […]». 17 Sin embargo,<br />

refiere que, al preguntarle a uno de estos ciguayos por los<br />

caribes, este indicó que se encontraban más al este, en una isla<br />

de nombre Carib.<br />

Además de la diferencia en el aspecto físico, se considera que<br />

los ciguayos tenían una lengua distinta, ya que, tras interpelar<br />

a uno de ellos sobre el oro, Colón narra: «llamava al oro “tuob”<br />

y no entendía por “canoa”, como le llaman en la primera parte<br />

de la isla, ni por “noçay” como lo nombravan en San Salvador y<br />

en las otras islas». 18 Por su parte, fray Bartolomé de las Casas, al<br />

comentar el Diario de Colón en su Historia de las Indias, añade:<br />

Es aquí de saber que un gran pedazo desta costa […] hasta las sierras<br />

que hacen desta parte del Norte la gran vega inclusive, era poblada<br />

de una gente que se llamaban mazoriges, y otras cyguayos, y tenían<br />

diversas lenguas de la universal de toda la isla. 19<br />

Láminas de oro o guanín.<br />

Rostro de un dúho con aplicaciones de oro. ©The Trustees of the British Museum, BM, Am1949,22.118

29<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Costa de Los Haitises en la bahía de Samaná, RD. ©Ricardo Briones

30<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Al bajar a tierra algunos de los tripulantes de las naves españolas<br />

en la bahía de Samaná con la intención de abastecerse<br />

de agua y alimentos, al tiempo de procurar algunos objetos<br />

indígenas que despertaban su curiosidad, fueron enfrentados<br />

por medio centenar de ciguayos armados con arcos, flechas<br />

y macanas de madera. Los españoles hirieron a dos de ellos,<br />

que infortunadamente conocieron el filo de las espadas de<br />

metal, derramándose allí la primera sangre americana vertida<br />

durante los enfrentamientos entre indígenas y conquistadores<br />

europeos. Debido a este hecho, Colón llamó golfo de las Flechas<br />

a esta bahía.<br />

La identificación y estudio de los ciguayos es un tema que<br />

aún debe plantearse con mayor profundidad sobre la base<br />

de la investigación arqueológica. A pesar de esto, algunos<br />

investigadores e historiadores han esbozado diversas hipótesis<br />

sobre estas comunidades, entre las que resalta la de una<br />

posible ascendencia caribe y un reciente asentamiento en la<br />

península de Samaná, razón esta última por la que sus huellas<br />

arqueológicas han sido imperceptibles en las prospecciones<br />

realizadas en la zona. Otras teorías plantean una interacción<br />

entre taínos y caribes que culminó con la adquisición de algunas<br />

costumbres caribes por parte de los habitantes de esta<br />

área de la Española. 20<br />

Uno de los investigadores que más se ha esforzado por aportar<br />

al llamado «enigma ciguayo», con base en las informaciones<br />

históricas y arqueológicas, ha sido Bernardo Vega. 21 A<br />

partir del análisis de las descripciones de varios cronistas, en<br />

especial de fray Bartolomé de las Casas, Gonzalo Fernández<br />

de Oviedo y Pedro Mártir de Anglería, y del mapa de Andrés<br />

Morales sobre la división política de la isla Española, Vega ha<br />

intentado definir los espacios geográficos que correspondían<br />

a ciguayos y macoriges, y, en líneas generales, ha planteado<br />

que los indígenas que Colón encontró en su primer viaje en<br />

el golfo de las Flechas tenían características propias de los<br />

caribes. En general, hasta el presente no existe un consenso<br />

sobre los asentamientos considerados ciguayos ni una clara<br />

definición de estos, y tampoco ha sido posible establecer con<br />

evidencias arqueológicas sus diferencias culturales respecto a<br />

los demás grupos indígenas que habitaron la isla. 22<br />

El interés de Colón por conocer las islas de los llamados «caribes»<br />

o «caníbales» lo llevó a intentar adentrarse más allá del<br />

extremo noroeste de la Española para comprobar su existencia.<br />

Sin embargo, el mal estado de las carabelas y la impaciencia<br />

de los tripulantes, deseosos de volver a España, le hicieron<br />

desistir de esta idea en su primer viaje y emprender el camino<br />

de retorno a Europa.<br />

Encuentro de los marineros de Cristóbal Colón con los ciguayos en Samaná. Vida y viajes de Cristóbal Colón, de Washington Irving (1854).

31<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Familia caribe de Surinam. Grabado de John G. Stedman.

32<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD

33<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Recipiente cerámico de la cultura taína. (MHD)<br />

Cristóbal Colón ante los reyes de España al regresar de su primer viaje. Óleo sobre<br />

tela, de Ricardo Balaca, 1874. Medida: 1860 X 1245 mm. Donación de Mónica<br />

Torromé de Mansilla, 25-X-1916 (f 35), Museo Histórico Nacional, Argentina.

A su regreso, el Almirante proclamó la noticia de la existencia<br />

de nuevas tierras allende los mares y mostró a los reyes algunos<br />

indígenas, así como otras pruebas de sus hallazgos. Recibió los<br />

honores y títulos que le correspondían, pactados previamente<br />

con la corona española en las llamadas Capitulaciones de Santa<br />

Fe, entre ellos, los de «Almirante de la Mar Océana y Visorrey y<br />

Gobernador de las islas descubiertas en las Indias». Por su parte,<br />

los indios que lo acompañaban fueron bautizados en una ceremonia<br />

religiosa ante la presencia de los reyes y el príncipe Juan.<br />

34<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

A raíz de la llegada de Colón a Europa, también aparecieron las<br />

primeras noticias impresas sobre los habitantes del Nuevo Mundo.<br />

Estas noticias fueron difundidas a través de la carta que el<br />

Almirante dirigió a Luis de Santángel, escribano de los monarcas<br />

españoles, y al tesorero aragonés Gabriel Sánchez, donde daba a<br />

conocer las novedades de las Indias. La misiva originalmente fue<br />

escrita en castellano y en ese idioma se realizó su primera impresión<br />

en Barcelona en 1493. Su difusión fue tan rápida que antes<br />

de culminar el siglo XV había alcanzado dieciséis ediciones en<br />

cinco idiomas: dos en castellano, una en catalán, nueve en latín,<br />

tres en italiano y una en alemán, además de algunas versiones<br />

en francés e inglés. En la traducción al latín aparece el nombre<br />

Hispaniola, vocablo que aún se utiliza para referirse a la isla Española,<br />

23 a la que los indígenas llamaban Bohío, Haití o Quisqueya.<br />

En esa carta en la que anunciaba el hallazgo de un Nuevo Mundo,<br />

Colón también se refiere a algunos de los primeros vocablos<br />

aborígenes recogidos durante su trayecto por las Antillas, palabras<br />

que pasaron a enriquecer la lengua española. Entre ellos<br />

sobresale el término canoa, incorporado por Antonio de Nebrija<br />

en su Gramática castellana en 1494, que representa uno de los<br />

primeros aportes lexicales de América a Europa.<br />

En general, las descripciones de los indígenas no se desligan del<br />

aura de asombro, expectativa y encantamiento que intensificó de<br />

forma cuantitativa la mayor parte de los textos colombinos. 24 Estas<br />

contribuyeron a la identificación de América como una tierra<br />

de abundancia y promisión, a lo que también aportó el obsesivo<br />

interés por el oro que se evidencia en buena parte de la narrativa<br />

de Colón y motivación omnipresente en casi todos sus enunciados.<br />

Desde esa perspectiva los relatos colombinos, a la vez que<br />

ofrecían las primeras impresiones sobre la realidad geográfica de<br />

las islas del Caribe, legaban, entre la descripción puntual y el rasgo<br />

imaginativo, la visión inicial del indio americano.<br />

Retrato de Cristóbal Colón, de Ridolfo del Ghirlandio (1483-1561). Navy Museum, Plegi, Génova, Italia.

35<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD

36<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Encuentro de Cristóbal Colón con los indígenas de la Española. Ilustración imaginaria de Theodor de Bry (1594).

El estudio del pasado<br />

Lo reducido de la fase asociada al empleo de la escritura en<br />

comparación con toda la existencia humana permite ilustrar la<br />

importancia de la arqueología como ciencia que investiga la<br />

cultura y la historia a partir de evidencias materiales. Los restos<br />

materiales fruto de la acción humana pueden convertirse,<br />

bajo la óptica científica de la arqueología, en importantes generadores<br />

de conocimiento histórico. Para ello, esta disciplina<br />

utiliza métodos capaces de arrojar informaciones para explicar<br />

el desarrollo de las sociedades del pasado. En ese sentido,<br />

puede proporcionar datos que por diversos motivos no fueron<br />

recogidos por las fuentes históricas, y en el caso de las<br />

sociedades ágrafas, es decir, de aquellas que no conocieron<br />

la escritura, constituye una de las principales disciplinas para<br />

acceder a su estudio.<br />

Al caracterizar las diferentes etapas por las que han atravesado<br />

las antiguas sociedades humanas en diferentes regiones del<br />

planeta, la arqueología ha desempeñado un rol importante en<br />

la creación de los modelos y clasificaciones de la prehistoria<br />

universal. Por tanto, un análisis de la arqueología antillana no<br />

puede desligarse del devenir general de esta disciplina arqueológica<br />

a nivel mundial ni de sus repercusiones en América.<br />

37<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

La arqueología puede considerarse como una actitud frente al<br />

pasado que inicialmente se manifestó a través de un interés<br />

especial por los objetos y las obras de arte de la Antigüedad<br />

clásica. 25 El coleccionismo alentado por los humanistas del<br />

Renacimiento se prolongó a largo de los siglos XVII y XVIII,<br />

extendiéndose a las cortes europeas y a personajes ilustrados<br />

de la época hasta convertirse en una afición respetable y muy<br />

de moda. 26<br />

Charles Towneley en su galería de esculturas de la época clásica. Óleo de Johann Zoffany.

38<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

La búsqueda del pasado durante ese período se transformó<br />

en la persecución de una utopía que debía ser reconstruida,<br />

y las antiguas obras reunidas en colecciones ejercieron una<br />

influencia extraordinaria en este sentido. Al calor de la búsqueda<br />

de la belleza dentro de los cánones clásicos, nació el<br />

interés por lo antiguo, en tanto los modos de vida de la Antigüedad<br />

se revelaban de manera más concreta a través de su<br />

iconografía. Esta primera arqueología esteticista, interesada<br />

en el arte y la arquitectura del mundo clásico, en el caso de<br />

América tuvo expresiones concretas que pueden rastrearse en<br />

la atracción ejercida por las culturas maya, azteca o inca, y<br />

fundamentalmente por los monumentos y creaciones artísticas<br />

dejados por estas grandes civilizaciones.<br />

Las diferencias esenciales entre esa arqueología esteticista<br />

y una más científica se concretaron, o al menos se hicieron<br />

más evidentes, en el siglo XIX. Los avances de las ciencias<br />

naturales, en especial de la biología, constituyeron los fundamentos<br />

del evolucionismo, teoría social y antropológica<br />

que se desarrolló durante ese siglo. A partir del siglo XIX el<br />

trabajo arqueológico comenzó a considerarse una disciplina<br />

académica para resolver problemas históricos. Un ejemplo de<br />

ello fue la primera clasificación del historiador danés Christian<br />

Jürgensen Thomsen, que incluía tres edades (Piedra, Bronce<br />

y Hierro) e intentaba explicar el desarrollo de la tecnología en<br />

Europa desde la perspectiva arqueológica, basándose en el<br />

análisis de los objetos prehistóricos. Además, la arqueología<br />

aportó nuevas bases para ampliar las concepciones evolucionistas<br />

imperantes en la época, según las cuales la sociedad<br />

había avanzado por medio de estadios progresivos, que, según<br />

Adam Smith, iban desde la caza hasta el desarrollo del<br />

comercio, pasando por el pastoreo y la agricultura. 27<br />

En sus inicios, la prehistoria como campo científico estuvo vinculada<br />

al empleo del criterio estratigráfico, un principio de la<br />

geología que se aplicaba en arqueología. Este, junto con los<br />

avances de la biología, fue trasladado al estudio y comprensión<br />

de los instrumentos y restos materiales del pasado. Con<br />

el empleo del método estratigráfico y el hecho de que comenzaran<br />

a vislumbrarse niveles de antigüedad para el ser humano,<br />

la arqueología prehistórica se convirtió en la principal<br />

línea de investigación de los pueblos anteriores a la escritura.<br />

El evolucionismo cultural se desarrolló sobre una base tecnológica,<br />

que tomaba como guía el material de los instrumentos<br />

(piedra, bronce o hierro). Esto, a su vez, conllevó la introducción<br />

del término «edad» en la interpretación del proceso por<br />

el que había atravesado la humanidad, especialmente a partir<br />

de sus manifestaciones en el occidente europeo.<br />

Instrumentos de la época paleolítica.

39<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Excavación arqueológica en una ruina romana de Italia.

40<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Reconstrucción idealizada de una escena de caza del oso de las cavernas durante el paleolítico en Europa, de Znedèk Burian.<br />

El concepto de las tres edades, unido al principio de superposición<br />

o estratificación, permitió establecer la nomenclatura terial lítico conforman la llamada «edad de piedra», a la que<br />

Estas primeras etapas caracterizadas por los trabajos en ma-<br />

prehistórica europea. Los estadios culturales más antiguos reciben<br />

el nombre de «paleolítico» y se identifican con los gru-<br />

que dieron lugar al desarrollo de las grandes civilizaciones que<br />

sucede la edad de los metales, cuando comienzan los procesos<br />

pos nómadas cazadores de la megafauna del pleistoceno. Un florecieron en Egipto, Mesopotamia, la Grecia antigua, etc.<br />

período intermedio, denominado «mesolítico», se inicia tras la<br />

finalización del período glacial, cuando las alteraciones climáticas<br />

ocasionan la extinción de los grandes mamíferos y, por ma mimética la prehistoria del Viejo Mundo con la del conti-<br />

Aunque no existe una sincronía que permita equiparar de for-<br />

tanto, se experimenta un cambio en los patrones de alimentación,<br />

la cual pasa a obtenerse principalmente de la recolec-<br />

Cruxent 29 emplearon, por analogía, los términos «paleoindio»,<br />

nente americano, arqueólogos como Irving Rouse y José M.<br />

ción, la caza de especies animales más pequeñas y la pesca. «mesoindio» y «neoindio» en el abordaje de las formas básicas<br />

El término «neolítico» ha sido reservado para la aparición de de subsistencia y la tecnología y tipología de las herramientas<br />

la agricultura, la ganadería y la cerámica. Los cambios que utilizadas para transformar el entorno en el ámbito caribeño.<br />

marcan la aparición del neolítico también se conocen como<br />

«revolución neolítica», término propuesto por el arqueólogo<br />

Vere Gordon Childe 28 para significar las transformaciones que<br />

se produjeron en los modos de subsistencia y la consolidación<br />

de la vida sedentaria.

41<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Diorama que recrea la caza de un mamut en la Cuenca de México durante el período lítico.<br />

©Archivo Digital de las Colecciones del Museo Nacional de Antropología, INAH-CANON

Estos esquemas constituyen solo una muestra de los diversos<br />

sistemas de clasificación implementados desde la arqueología<br />

al estudiar las primeras comunidades humanas que poblaron<br />

las Américas y el Caribe. Otros sistemas de clasificación han<br />

enfatizado aspectos económicos, tecnológicos, ecológicos,<br />

sociales o la combinación de algunos de ellos. Un ejemplo de<br />

esto último podemos encontrarlo en la propuesta de investigadores<br />

como Gordon R. Willey y Philip Phillips, 30 quienes<br />

establecieron una periodización de la prehistoria de América<br />

dividiéndola en las siguientes etapas:<br />

42<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Estela de la civilización maya. Litografía de Frederick Catherwood.<br />

• Lítica: etapa de los cazadores nómadas que vivieron en<br />

la última glaciación, a finales del período pleistoceno, y<br />

se dedicaron fundamentalmente a la captura de grandes<br />

mamíferos terrestres como el mastodonte, el megaterio<br />

o perezoso gigante y el armadillo gigante.<br />

• Arcaica: los cambios climáticos posglaciales ocasionaron<br />

la extinción de la fauna pleistocénica, forzando a los<br />

cazadores superiores a buscar otras fuentes alternativas<br />

de alimentos, como la caza menor, la pesca y la recolección<br />

de plantas silvestres y mariscos.<br />

• Formativa: equivalente al neoindio planteado por Cruxent<br />

y Rouse. En esta etapa hacen su aparición las prácticas<br />

agrícolas, lo que permite el abandono del nomadismo,<br />

el establecimiento de aldeas de carácter permanente<br />

y una organización social más compleja. Además, surgen<br />

la cerámica y otras artesanías, que se realizaban en el<br />

tiempo que no se dedicaba a los cultivos.<br />

• Altas culturas o civilizaciones: con centros ceremoniales<br />

y conjuntos urbanos propios de sociedades teocráticas<br />

jerarquizadas que desarrollaron una economía con excedentes.<br />

Localizadas fundamentalmente en Mesoamérica<br />

y en el altiplano andino, entre ellas se incluye a olmecas,<br />

mayas, aztecas e incas. Esta etapa abarca en ocasiones<br />

otros períodos inherentes al desarrollo de civilizaciones,<br />

como el clásico y el posclásico.

43<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Ídolo y altar de Copán, Honduras. De Frederick Catherwood.

44<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD

El poblamiento de las Antillas<br />

Desde los primeros momentos de la conquista surgió la inquietud<br />

por conocer la antigüedad de los habitantes de las<br />

islas del Caribe. Fray Bartolomé de las Casas fue uno de los<br />

primeros en referirse a este tema –incluso con cierto sentido<br />

de curiosidad arqueológica– cuando en su Historia de las Indias,<br />

al relatar las excavaciones hechas para edificar la fortaleza<br />

de Santo Tomás de Jánico, refiere lo siguiente:<br />

Yo he visto en las mismas minas de Cibao, a estado y dos estados<br />

en hondo de tierra virgen, en llanos, al pie de algunos cerros, haber<br />

carbones y ceniza, como si hobiera pocos días que se hobiera<br />

hecho allí fuego, y por la misma razón hemos de concluir que en<br />

otros tiempos iba por allí cerca el río, y en aquel lugar hicieron<br />

fuego, y después, apartándose más el agua del río, amontonóse<br />

la tierra sobre él que con las lluvias descendía del cerro, y porque<br />

esto no pudo ser sino por gran discurso de años y antiquísimo<br />

tiempo, por eso es grande argumento que las gentes destas islas<br />

y tierra firme son antiquísimas. 31<br />

Las investigaciones arqueológicas han demostrado que el poblamiento<br />

de las Antillas ocurrió hace aproximadamente unos<br />

6000 años y que pudo haber estado vinculado a fenómenos<br />

climáticos acaecidos entre el 8000 y el 4000 antes de Cristo.<br />

Esos cambios generaron transformaciones en los ambientes<br />

de las zonas continentales, incidiendo en la desaparición o<br />

reducción de determinadas especies de animales y plantas<br />

propias del pleistoceno.<br />

Los cambios climáticos pudieron funcionar como un importante<br />

catalizador del desplazamiento de las primeras comunidades<br />

desde el continente hasta las islas del Caribe. 32 En<br />

especial, porque esos grupos debieron enfrentar nuevas condiciones<br />

para desarrollar su actividad alimenticia, basada, fundamentalmente,<br />

en la recolección y la pesca, lo que los obligó<br />

a asentarse en las desembocaduras de los grandes ríos, o en<br />

zonas cercanas al litoral, familiarizándose así con el mar y perfeccionando<br />

la habilidad de navegar. 33<br />

Aunque recientes investigaciones demuestran que, además<br />

de la recolección y la pesca, pudieron aprovechar una gran<br />

variedad de plantas silvestres 34 y elaborar cerámica incipiente<br />

en algunos de sus contextos. 35<br />

Sus modos de vida se distanciaron de los pobladores del<br />

período lítico, más vinculados con la cacería de grandes animales<br />

y la recolección en zonas selváticas interiores. Como<br />

huellas de esa intensa actividad recolectora, dejaron grandes<br />

vertederos o acumulaciones de desperdicios de comida marina<br />

y fluvial. En torno a estos residuarios, que los arqueólogos<br />

denominan «concheros», emplazaron sus viviendas, lo que<br />

constituye el patrón de asentamiento característico de los pobladores<br />

arcaicos. 36<br />

Esas comunidades iniciaron un proceso migratorio hacia las<br />

Antillas para el cual se han establecido dos rutas fundamentales.<br />

La primera, desde Centroamérica –en especial desde<br />

zonas de la costa atlántica aledañas al actual Belice– hasta las<br />

Antillas Mayores, sobre todo Cuba y la Española, e incluyendo<br />

parte de Puerto Rico. 37 La segunda, desde la zona noreste de<br />

Venezuela y la isla de Trinidad, a través de las Antillas Menores,<br />

hasta alcanzar el extremo más occidental del Caribe. 38<br />

No se conoce con exactitud el tipo de embarcación utilizado<br />

por los grupos arcaicos, aunque existe cierto consenso sobre<br />

el posible uso de balsas rústicas formadas por troncos de<br />

árboles amarrados con lianas o cuerdas de fibras vegetales.<br />

Aunque tampoco se descarta el uso de la canoa, embarcación<br />

monóxila confeccionada con un tronco ahuecado e impulsada<br />

por remos, la cual emplearon los posteriores contingentes migratorios<br />

que poblaron el Caribe insular.<br />

45<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD

46<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD

Los protoarcaicos<br />

artefactos de pedernal<br />

El uso de la piedra para la fabricación de utensilios es tan remoto<br />

como la misma humanidad; y se desarrollaron a través<br />

de los tiempos múltiples técnicas y habilidades que incluyen la<br />

selección de una materia prima adecuada. A grandes rasgos,<br />

dos técnicas o industrias líticas caracterizan los estadios culturales<br />

más antiguos de la prehistoria universal: la piedra tallada,<br />

obtenida a partir de percusión o golpeo, y la piedra pulida. En<br />

el horizonte cultural arcaico antillano se emplearon ambas técnicas,<br />

y con ellas se elaboró una variada gama de artefactos<br />

que les permitieron a los primeros pobladores aprovechar los<br />

recursos naturales que les ofrecía el medio ambiente.<br />

En arqueología, el término «horizonte cultural» se refiere al<br />

período en el que se desarrolla un estilo o cultura. En ese<br />

sentido, es posible distinguir un horizonte de otro a partir de<br />

rasgos o manifestaciones culturales, entre ellos, los utensilios<br />

utilizados por comunidades que vivieron durante un período<br />

determinado. De modo que el instrumental y las materias<br />

primas empleadas en su confección resultan de gran utilidad<br />

para establecer las características socioeconómicas de estos<br />

grupos humanos.<br />

47<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Los primeros grupos en ocupar las Antillas han sido denominados<br />

«paleoarcaicos» por algunos arqueólogos, 39 mientras<br />

otra nomenclatura los califica como «protoarcaicos», 40 haciendo<br />

referencia a su antigüedad, así como a las características<br />

esenciales de su economía y su ajuar. Estos primitivos pobladores<br />

utilizaron roca silícea o pedernal para confeccionar filosas<br />

lascas y láminas que desprendían de un nódulo por medio<br />

de golpes certeros o percusión directa. De hecho, los sitios<br />

relacionados con estos grupos en la Española y Cuba están<br />

ubicados en zonas donde abunda este tipo de materia prima.<br />

Punta de sílex o pedernal localizada en la Cordillera Central de la isla Española.<br />

Confección de instrumentos de sílex por cazadores del paleolítico en Europa. Ilustración de Znedèk Burian.

Igualmente, se han registrado evidencias de las primeras ocupaciones<br />

protoarcaicas en el sitio de Levisa, en Cuba. 43 La<br />

fecha de radiocarbono más antigua para este asentamiento<br />

corresponde al año 3190 a. C., por lo que se considera uno<br />

de los poblamientos más tempranos de las Antillas Mayores.<br />

La reevaluación reciente del contexto de Levisa, así como de<br />

otros sitios protoarcaicos de Cuba, 44 también ha revelado su<br />

posible carácter multicomponente. Es decir, estos espacios no<br />

solo incluyen el componente cultural protoarcaico, sino el de<br />

otros grupos que habitaron allí en momentos posteriores.<br />

48<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Lascas de sílex de la sierra de Barrera, Azua, RD.<br />

Una de las evidencias más tempranas de habitación humana en<br />

la isla Española, relacionada con los protoarcaicos, fue dada a<br />

conocer por los investigadores J. M. Cruxent e Irving Rouse. Se<br />

trata del sitio arqueológico de Mordán, en la sierra de Barrera,<br />

provincia Azua, con fechado de unos 2600 a. C. obtenido por<br />

el método de radiocarbono (C-14). Aunque estos arqueólogos<br />

estimaron que algunos complejos líticos de la zona, como el<br />

sitio de Casimira, pudieran alcanzar mayor antigüedad. 41<br />

La ausencia de datos etnohistóricos sobre estas antiguas comunidades<br />

ha conllevado la necesidad de emplear ciertos términos<br />

para denominar sus expresiones locales o regionales<br />

más sobresalientes. En el caso de la arqueología del Caribe,<br />

ha predominado durante décadas el uso del nombre de los<br />

lugares donde aparecen los vestigios. A la ubicación geográfica<br />

de algunos asentamientos importantes clasificados como<br />

protoarcaicos, se ha agregado el sufijo oide para nombrar las<br />

culturas que identifican. Así, a las manifestaciones presentes<br />

en Mordán se les llama «mordanoides», y a las de Barrera,<br />

«barreroides», al igual que se denomina «casimiroide» al contexto<br />

cultural vinculado con Casimira, por lo que esos lugares<br />

se han convertido en epónimos de los rasgos distintivos de los<br />

primeros habitantes de las Grandes Antillas. 42<br />

El fenómeno presente en Levisa fue reconocido inicialmente<br />

por investigadores como José Manuel Guasch, Januz<br />

Kozlowski y Marcio Veloz Maggiolo; 45 y ha ganado importancia<br />

en la actualidad al evaluarse las posibles interacciones de<br />

los primeros grupos que utilizaron grandes herramientas de<br />

sílex con otras comunidades arcaicas que también habitaron<br />

el archipiélago antillano. Se trata de una cuestión que amerita<br />

investigaciones más profundas, aunque sí parece claro que<br />

algunos de los lugares ocupados inicialmente por los protoarcaicos<br />

fueron de interés para otros grupos que posteriormente<br />

habitaron las Antillas.<br />

En definitiva, el carácter multicomponente que se observa en<br />

algunos de los sitios conocidos como «protoarcaicos» ilustra<br />

coincidencias de naturaleza compleja en cuanto a preferencias<br />

ambientales y espaciales por parte de los diversos grupos<br />

arcaicos, aunque no tuvieran necesariamente existencias paralelas.<br />

En Puerto Rico existen evidencias de estos antiguos complejos<br />

culturales en lugares como Angostura (cercano a Barceloneta),<br />

Maruca (en Ponce) y Cabo Rojo (en el occidente de la<br />

isla), cuya antigüedad alcanza en algunos casos alrededor del<br />

3000 a. C. Esto sugiere que esos primeros pobladores posiblemente<br />

se desplazaron de oeste a este, extendiéndose desde<br />

Cuba a las demás Antillas Mayores.

En el occidente de la isla Española, en la actual República de<br />

Haití, el ajuar de sílex relacionado con los protoarcaicos está<br />

presente en la región de Cabaret en sitios que han sido asociados<br />

con grandes talleres líticos. Según las investigaciones y<br />

descripciones de campo del estudioso de la arqueología haitiana<br />

Clark Moore, 46 se han descubierto en esa región unos<br />

37 sitios líticos. Los más grandes llegan a alcanzar entre 5,000<br />

y 10,000 m 2 y los más pequeños 100 m 2 . Por lo general, se<br />

encuentran a altitudes entre 40 y 120 metros, en pendientes<br />

graduales y no en la cima de las colinas. Todos están asociados<br />

a depósitos de sílex, que constituía la materia prima por<br />

excelencia para la fabricación de sus artefactos.<br />

Los talleres líticos fueron ocupados probablemente de manera<br />

temporal. De ahí, la ausencia de una estratigrafía consistente<br />

que revele la evolución cultural en estos sitios. Sin embargo,<br />

ese no parece ser el caso de los asentamientos de mayores dimensiones.<br />

Las fechas de radiocarbono obtenidas en algunos<br />

yacimientos de Haití señalan su posible contemporaneidad<br />

con el sitio de Levisa, en Cuba, como es el caso de Vignier III,<br />

con datación de 3630 ± 80 años a. C. Por otro lado, la fecha<br />

de 2420 a. C. del sitio de Source Matelas, también en Haití,<br />

lo aproxima cronológicamente a las fechas de 2617 y 2583<br />

a. C. obtenidas, conforme a pruebas de radiocarbono (C-14),<br />

para Mordán en la República Dominicana. 47 De este modo se<br />

ha observado que los instrumentos de sílex recuperados en<br />

la zona haitiana de Cabaret son comparables a los vestigios<br />

líticos de Cuba y la República Dominicana, lo que sugiere que<br />

los pobladores protoarcaicos ocuparon simultáneamente varios<br />

espacios de las Antillas Mayores. 48<br />

En la parte oriental de la Española, hoy República Dominicana,<br />

los protoarcaicos se asentaron preferentemente en el<br />

suroeste, donde abundan las rocas silíceas de color gris claro<br />

o blancuzco, como en la sierra de Barrera (Azua), en Puerto<br />

Alejandro (provincia Barahona) y en la ribera y desembocadura<br />

del río Pedernales. 49 Sus residuarios corresponden a emplazamientos<br />

temporales donde posiblemente se ubicaron<br />

talleres que elaboraban instrumentos cortantes. Con la técnica<br />

del retoque confeccionaron puntas y cuchillos, algunos de<br />

apreciable tamaño, con rebordes laterales dentados que hacían<br />

las veces de sierra. Algunos de estos artefactos punzantes<br />

estaban provistos de un mango o pedúnculo que facilitaba su<br />

manipulación, o bien su inserción en el extremo de una vara<br />

de madera a modo de lanza.<br />

Debido al carácter filoso del sílex o pedernal, muchas de las<br />

herramientas fabricadas con lascas de este material pudieron<br />

utilizarse para despellejar, trozar y descamar las presas obtenidas<br />

de la caza y la pesca. También resultaban apropiadas<br />

para trabajar la madera y las fibras vegetales, que constituían<br />

un componente importante en el menaje de estas comunidades,<br />

como lo evidencian los análisis de herramientas líticas<br />

obtenidas en el área de Barrera y realizados por el investigador<br />

A. Gus Pantel. 50<br />

49<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Puntas de sílex de forma lanceolada con pedúnculos.

En realidad, la fabricación de raspadores y lascas simples de<br />

forma rectangular exigía poca sofisticación, y probablemente<br />

se desechaban al perder filo. Lo importante era obtener la materia<br />

prima requerida, como los núcleos de roca silícea de los<br />

que se desprendían las lascas, los cuales constituían parte de<br />

una dinámica de intercambios constatable en asentamientos<br />

arcaicos de la vecina isla de Puerto Rico, donde con frecuencia<br />

se han localizado lascas de cuarzo procedentes de la Española.<br />

51<br />

De forma dispersa, se han encontrado grandes cuchillos y puntas<br />

de pedernal asociados a estas comunidades protoarcaicas<br />

en las estribaciones de las cordilleras Central y Septentrional<br />

de la Española, lo que ha dado origen al llamado «complejo<br />

lítico de la cordillera» o «cordilleroide». 52<br />

50<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Estos artefactos puntiagudos pudieron emplearse en el descuartizamiento<br />

de las presas, lo que facilitaba su traslado<br />

desde el sitio de captura hasta los campamentos o lugares<br />

de habitación, donde se compartía la comida. Una vez trozadas<br />

las piezas de cacería, podían acarrearse utilizando algún<br />

tipo de cestas tejidas con fibras vegetales, lo que permitiría<br />

su transporte a grandes distancias. En algunas pictografías de<br />

períodos posteriores conservadas en el interior de las cavernas<br />

dominicanas –como son los casos del Hoyo de Sanabe y<br />

la Guácara del Comedero, ambas cercanas a Cotuí y descubiertas<br />

por los investigadores Dato Pagán Perdomo y Manuel<br />

García Arévalo, 53 se aprecia que en ocasiones se requería de<br />

dos individuos para acarrear una presa colgada de una vara.<br />

Además de los instrumentos de pedernal que se asocian al<br />

período temprano del poblamiento antillano, los protoarcaicos<br />

utilizaron cantos rodados o guijarros en su forma natural,<br />

con los que improvisaron rústicos martillos como percutores<br />

para trabajar el sílex.<br />

Núcleo de sílex. Museo de Arqueología de Cataluña, Barcelona, España.

También se utilizaban para romper las conchas de los caracoles<br />

y los caparazones de los crustáceos colectados en los<br />

acantilados rocosos y en el lecho arenoso de playas con fondos<br />

bajos, así como para triturar o moler semillas u otros alimentos<br />

obtenidos de especies botánicas silvestres.<br />

Se han encontrado evidencias de algunas especies animales<br />

de gran tamaño con apariencia de osos o de grandes perezosos,<br />

como el Parocnus serus Miller y el Acratocnus comes<br />

Miller, 54 cuyo tamaño alcanzaba la altura de un ser humano.<br />

Sus restos han sido localizados en algunas cuevas del valle<br />

de Constanza, provincia La Vega, y en la cueva del Pomier,<br />

provincia San Cristóbal, lo que sugiere que habitaban preferentemente<br />

en zonas montañosas, donde el clima era más<br />

templado que en las sabanas y las planicies costeras. Estos<br />

mamíferos edentados de considerable tamaño ya estaban extintos<br />

a la llegada de los conquistadores españoles y al parecer<br />

nunca fueron especies abundantes en la isla. 55 Por esa razón,<br />

los pobladores protoarcaicos complementaban su dieta<br />

con recursos obtenidos de la recolección marina o terrestre y<br />

de la pesca, al igual que de la cacería de animales de menor<br />

talla (como iguanas, jutías y lagartos) y de aves, de las que no<br />

solo debieron aprovechar su carne sino también sus plumas<br />

con fines decorativos.<br />

51<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Otras especies de apreciable tamaño también pudieron ser<br />

aprovechadas por estos grupos, sobre todo, la foca tropical<br />

(Manachus tropicalis) y el manatí (Trichechus manatus). 56 Este<br />

último aún incursiona en estuarios y ríos de la Española en busca<br />

de plantas alimenticias. En cuanto a la foca, extinta en la actualidad,<br />

quizás una especie similar existía en tiempos de Cristóbal<br />

Colón, quien afirmó haber visto lobos marinos en la isleta<br />

de Alto Velo, localizada en las inmediaciones de la isla Beata,<br />

durante su segundo viaje de exploración y descubrimiento. 57<br />

Pictografía de dos indígenas acarreando una presa. Guácara del Hoyo de Sanabe, Sánchez Ramírez, RD.<br />

Lasca de sílex raspando un trozo de madera.

52<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD

Los protoarcaicos debieron cazar, además, el cocodrilo (Crocodilus<br />

acutus), hoy casi extinto y relegado a las inmediaciones de los<br />

lagos Enriquillo, provincia Bahoruco, y Saumatre, en Haití. Es probable<br />

que esta especie tuviera una amplia difusión geográfica,<br />

pues incluso en el extremo oriental de la isla se han encontrado<br />

sus osamentas. 58 Igualmente, existió un tipo de mono ardilla autóctono<br />

de la isla (familia Cebidae, género Saimiri, especie bernensis)<br />

cuyos restos fueron descubiertos por Renato Rímoli en la<br />

cueva de Berna, provincia La Altagracia. 59 Este animal tampoco<br />

llegó a ser conocido por los españoles, lo que sugiere que pudo<br />

haber sido objeto de caza durante la época prehistórica o que ya<br />

estaba en proceso de extinción al arribo de los primeros pobladores<br />

indígenas.<br />

Aunque hasta la fecha no existen evidencias arqueológicas sólidas,<br />

es posible que los protoarcaicos emplearan los huesos de<br />

estas especies para la fabricación de utensilios, como puntas de<br />

arpones y anzuelos, e incluso de adornos para realzar su apariencia<br />

personal. Tampoco tenemos suficientes datos acerca de<br />

su ceremonialismo, aunque es factible suponer que tuvieran una<br />

cosmogonía con rituales mágico-religiosos de gran expresividad,<br />

como se puede apreciar en el arte rupestre del período arcaico<br />

en algunas partes de las Antillas. 60<br />

Las actividades de caza debieron ser desempeñadas generalmente<br />

por los hombres, dado el esfuerzo físico que requería rastrear<br />

durante días y enfrentarse a animales de considerable tamaño.<br />

Los restos humanos encontrados por el antropólogo Fernando<br />

Luna Calderón en el sitio de Cueva Roja, provincia Pedernales,<br />

evidencian que en la población adulta existía un alto porcentaje<br />

de fracturas de huesos largos, posiblemente como consecuencia<br />

de accidentes debidos a la gran movilidad vinculada a sus actividades<br />

de subsistencia en zonas inhóspitas. 61<br />

La organización social debió consistir en pequeños grupos que<br />

llevaban una vida trashumante, con campamentos temporales<br />

integrados por pocos individuos o núcleos familiares. Esta baja<br />

densidad poblacional entre las comunidades protoarcaicas quizás<br />

sea una de las razones que explique el escaso número de<br />

yacimientos localizados, que en la mayoría de los casos corresponden<br />

a talleres para trabajar el sílex.<br />

Aunque no existen evidencias sólidas en el contexto antillano sobre<br />

la división del trabajo en estas comunidades, la analogía con<br />

poblaciones de otros lugares sugiere que los hombres cazaban,<br />

desbrozaban el terreno y construían las estructuras necesarias<br />

para los campamentos, mientras que las mujeres desarrollaban<br />

labores de recolección y otras actividades productivas y domésticas.<br />

Esa distribución de roles característica de las sociedades<br />

cazadoras-recolectoras ha hecho pensar a investigadores como<br />

Mircea Eliade que existía una organización de las tareas de acuerdo<br />

al sexo. 62<br />

Finalmente, conviene destacar que, a pesar de su simplicidad,<br />

el uso de artefactos de sílex asociados al horizonte cultural protoarcaico<br />

se mantuvo vigente entre los sucesivos pobladores indígenas<br />

de las Antillas. Prueba de ello son las lascas de pedernal<br />

que aparecen vinculadas a todos los contextos culturales prehispánicos,<br />

incluso entre los grupos agroalfareros. Además de la arqueología,<br />

lo documentan cronistas como fray Bartolomé de las<br />

Casas, que, al resaltar la capacidad artesanal de los taínos, alude<br />

al empleo del pedernal como herramienta para la confección de<br />

los más variados objetos. 63<br />

53<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD<br />

Manatí en el Caño de Estero Hondo, Puerto Plata, RD. ©José Alejandro Álvarez

Punta de sílex de forma lanceolada con pedúnculo.<br />

54<br />

TAÍNOS, ARTE Y SOCIEDAD

La presencia constante de los instrumentos de pedernal entre<br />

las comunidades indígenas se mantuvo incluso durante la conquista<br />

europea. Esta persistencia es avalada por el historiador<br />

Luis Joseph Peguero, quien en su Historia de la conquista de<br />

la isla Española de Santo Domingo, al escribir sobre la sublevación<br />

del cacique Enriquillo, ofrece la siguiente información:<br />

Y se fue [Enriquillo] por encima de la sierra de los Pedernales: que<br />

se decía así, por los indios de la provincia de Azua que se componía<br />

de 17 pueblos, los más de ellos tenían por granjerías hacer hachas<br />

y otros instrumentos de su huso, para bender a las otras provincias<br />