Panorámica de la Pintura

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

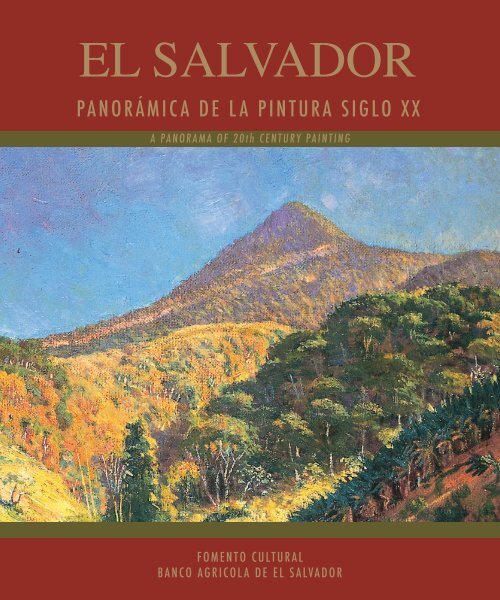

EL SALVADOR<br />

PANORÁMICA DE LA PINTURA SIGLO XX<br />

A PANORAMA OF 20th CENTURY PAINTING<br />

1<br />

FOMENTO CULTURAL<br />

BANCO AGRICOLA DE EL SALVADOR

EL SALVADOR<br />

PANORÁMICA DE LA PINTURA SIGLO XX<br />

A PANORAMA OF 20th CENTURY PAINTING<br />

Muestra Puntos Cardinales • Cardinal Points Exhibition<br />

4 5<br />

Luis Croquer<br />

TEXTOS CURATORIALES • CURATORIAL TEXT<br />

Bélgica Rodríguez<br />

INTRODUCCIÓN • INTRODUCTION<br />

Fe<strong>de</strong>rico Trujillo<br />

FOTOGRAFÍA • PHOTOGRAPHY<br />

C<strong>la</strong>udia Allwood<br />

COORDINACIÓN EDITORIAL •EDITORIAL COORDINATION

2 3

Reconocimientos<br />

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

Coordinación general•General Coordination<br />

Joaquín Rivas Boschma<br />

Por su apoyo y contribución a <strong>la</strong> e<strong>la</strong>boración <strong>de</strong> esta edición, el Banco Agríco<strong>la</strong><br />

agra<strong>de</strong>ce a <strong>la</strong>s siguientes personas e instituciones:<br />

Diseño gráfico y diagramación•Graphic Design and Layout<br />

Florencia Vi<strong>de</strong>s <strong>de</strong> Nosthas<br />

Víctor Manuel Nosthas<br />

Producción digital•Digital Production<br />

Ana Julia Ibarra Magaña<br />

4 Otros textos•Other Texts<br />

• Asociación Museo <strong>de</strong> Arte <strong>de</strong> El Salvador<br />

5<br />

Luis Sa<strong>la</strong>zar Retana<br />

Descripción <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong>s obras: La Cruz, Pajaro muerto y La botel<strong>la</strong>• Description of art works: The Cross, Dead Bird and The Bottle<br />

Revisión histórica y corrección <strong>de</strong> estilo•Historical Text and Spanish Style Editor<br />

Carlos Caños-Dinarte<br />

Traducción•Trans<strong>la</strong>tion<br />

Alexandra Lytton Rega<strong>la</strong>do<br />

Editora <strong>de</strong> estilo idioma inglés•English Style Editor<br />

Emma Trelles<br />

For their support and contribution to this edition, Banco Agríco<strong>la</strong> expresses its<br />

gratitu<strong>de</strong> to the following persons and institutions:<br />

• Museo <strong>de</strong> Arte <strong>de</strong> El Salvador<br />

• Fundación Julia Díaz<br />

• Coleccionistas privados <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> muestra Puntos Cardinales<br />

• Colección Nacional, Consejo Nacional pora <strong>la</strong> Cultura y el Arte, CONCULTURA<br />

• María Marta Papini <strong>de</strong> Rega<strong>la</strong>do<br />

• Elidia Lecha <strong>de</strong> Lindo<br />

• Sandra <strong>de</strong> Escapini<br />

• Ana Magdalena Granadino<br />

• Alexandra Lytton Rega<strong>la</strong>do<br />

• Roberto Galicia<br />

• María Elena González<br />

• Violeta Ávi<strong>la</strong> <strong>de</strong> Lytton<br />

Gerencia <strong>de</strong> Comunicaciones <strong>de</strong>l Banco Agríco<strong>la</strong><br />

Comunications Banco Agríco<strong>la</strong><br />

Asistencia en fotografía•Photographer’s Assistant<br />

Nelson Crisóstomo<br />

Impresión•Printing<br />

Avanti Gráfica S.A, <strong>de</strong> C.V.<br />

ISBN 99923-810-7-8<br />

® 2004. Banco Agríco<strong>la</strong><br />

Derechos reservados<br />

Queda prohibido, como lo establece <strong>la</strong> ley, <strong>la</strong> reproducción parcial o total <strong>de</strong> este libro sin previo permiso por escrito<br />

<strong>de</strong>l editor, con excepción <strong>de</strong> breves fragmentos que pue<strong>de</strong>n usarse en reseñas en los distintos medios <strong>de</strong> comunicación,<br />

siempre que se cite <strong>la</strong> fuente.

Contenido<br />

CONTENTS<br />

Presentación•Presentation<br />

Prólogo•Prologue<br />

Introducción•Introduction<br />

Puntos Cardinales: Propuesta curatorial•Cardinal Points: Curatorial Proposal<br />

6 7<br />

Memoria y Cultura•Memory and Culture<br />

Rostros y Figuras•Portraits and Figures<br />

Realidad y Fantasia•Reality and Fantasy<br />

Entorno y Materia • Environment and Matter<br />

Una aproximación histórica•A Historial Perspective<br />

Construyendo un sueño•Building a Dream<br />

Bibliografía•Bibliography

8 9

Presentación<br />

PRESENTATION<br />

Siguiendo <strong>la</strong> tradición <strong>de</strong> nuestros libros, queremos nuevamente <strong>de</strong>jar un legado a <strong>la</strong><br />

sociedad salvadoreña, esta vez mediante una visión panorámica <strong>de</strong> nuestros pintores<br />

y sus obras a lo <strong>la</strong>rgo <strong>de</strong>l siglo XX, en el cual se <strong>de</strong>jan entrever <strong>la</strong>s dinámicas históricas<br />

que se sucedieron, sin prece<strong>de</strong>ntes, y que permitieron el logro <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> tan anhe<strong>la</strong>da paz<br />

y <strong>de</strong> un enfoque hacia el <strong>de</strong>sarrollo humano con miras a <strong>la</strong> centuria veni<strong>de</strong>ra. De esta<br />

forma queremos que los salvadoreños y quienes se muestran interesados en nuestras<br />

raíces, puedan ver a través <strong>de</strong>l arte pictórico <strong>la</strong> vincu<strong>la</strong>ción con <strong>la</strong>s vivencias, paisajes y<br />

sentimientos expresados por nuestros artistas en sus obras.<br />

In keeping with the tradition of our Rincón Magico El Salvador series of books, we<br />

would like to extend to Salvadoran society the legacy of our national art as presented<br />

through this panoramic vision of our painters and their works throughout the XX century.<br />

This era ushered the country through unprece<strong>de</strong>nted historical and dynamic events that<br />

allowed for peace and a vision towards the new century. Our hope is that Salvadorans<br />

and others interested in our country’s roots will be able to appreciate the connections<br />

this pictorial art establishes with the experiences, emotions, and <strong>la</strong>ndscapes expressed<br />

by national artists.<br />

Bajo el manto <strong>de</strong> nuestro Rincón Mágico El Salvador, hacemos entrega <strong>de</strong> este libro<br />

pictórico que sabemos trascen<strong>de</strong>rá fronteras y estimu<strong>la</strong>rá tanto en su lectura como en<br />

<strong>la</strong> contemp<strong>la</strong>ción <strong>de</strong> sus fotografías, que nos acercarán <strong>la</strong>s pupi<strong>la</strong>s hacia el mundo <strong>de</strong><br />

sentimientos <strong>de</strong> aquellos que han forjado y forjarán por siempre nuestra pintura<br />

nacional, más al<strong>la</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> imaginación y <strong>la</strong>s artes. Las siguientes son imágenes que nos<br />

invitan, mediante <strong>la</strong>s páginas <strong>de</strong> este novedoso volumen, a enriquecernos una vez<br />

más entre los bellos entornos y personas que abriga El Salvador.<br />

As this book circu<strong>la</strong>tes throughout and across our national bor<strong>de</strong>rs, we at Banco Agríco<strong>la</strong><br />

believe that this text and its images will invite rea<strong>de</strong>rs to connect with the artistic<br />

inspiration of the men and women that forged the i<strong>de</strong>ntity of Salvadoran painting and<br />

allowed us to expand our imaginations. We hope that the following images of this new<br />

volume will allow rea<strong>de</strong>rs to once again appreciate the beautiful surroundings and<br />

people that make up El Salvador.<br />

Por muchos años, el Programa <strong>de</strong> Fomento Cultural <strong>de</strong> nuestro Banco Agríco<strong>la</strong> ha For many years, the Banco Agríco<strong>la</strong>´s Programa <strong>de</strong> Fomento Cultural (Cultural<br />

logrado fotografiar el rico patrimonio <strong>de</strong> este bello país, llevándonos <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> mano y Development Program) has been able to present the rich heritage of this beautiful<br />

enfocándonos en aquellos rincones mágicos <strong>de</strong> nuestra tierra, a<strong>de</strong>ntrándonos en el country through photographs. These books have gui<strong>de</strong>d us towards the magical p<strong>la</strong>ces<br />

colorido <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong>s orquí<strong>de</strong>as así como en <strong>la</strong> sutileza con <strong>la</strong> que trabajamos <strong>la</strong>s artesanías of Salvadoran geography. They have invited us to appreciate the colors of our orchids<br />

10 <strong>de</strong> barro y fibras, haciéndonos partícipes, a <strong>la</strong> vez, <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> lejanía fundamentada en and the beauty of our c<strong>la</strong>y and textile handicrafts. They have allowed us to become<br />

11<br />

nuestra historia precolombina o recorriendo los campos <strong>de</strong> batal<strong>la</strong> <strong>de</strong>l siglo XIX don<strong>de</strong><br />

se forjó El Salvador que hoy conocemos.<br />

Ahora me honra presentar este nuevo libro, al cual les invito a que se asomen a<br />

conocer parte <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> historia <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> pintura <strong>de</strong> nuestro Rincón Mágico El Salvador, <strong>la</strong><br />

plástica nacional expresada en colores y trazos que se conjugan para pintar un país<br />

hermoso, tomando como esencia <strong>de</strong> contenido <strong>la</strong> muestra <strong>de</strong> pintura exhibida en <strong>la</strong><br />

exposición Puntos Cardinales, presentada como propuesta curatorial en <strong>la</strong> gran sa<strong>la</strong><br />

<strong>de</strong>l Museo <strong>de</strong> Arte <strong>de</strong> El Salvador, mejor conocido como MARTE.<br />

participants of faraway moments in our pre-Colombian history and taken us back in<br />

time to battles of the XIX century, where the El Salvador we know today was forged<br />

and consolidated.<br />

Now I am honored to present this new book, which invites us to learn more about<br />

Salvadoran painting and <strong>de</strong>picts the beauty of our country through colors and brush<br />

strokes. It features the works that comprise Puntos Cardinales (Cardinal Points), a<br />

curatorial proposal presented in the grand hall of the Museo <strong>de</strong> Arte <strong>de</strong> El Salvador<br />

(El Salvador Museum of Art, MARTE).<br />

Rodolfo Schildknecht<br />

PRESIDENTE DEL BANCO AGRÍCOLA

El 22 <strong>de</strong> mayo <strong>de</strong> 2003, con legítimo orgullo y con <strong>la</strong> inmensa satisfacción <strong>de</strong>l<br />

<strong>de</strong>ber cumplido, entregamos a El Salvador, y a todos sus ciudadanos, el Museo<br />

<strong>de</strong> Arte <strong>de</strong> El Salvador, MARTE. Ahora, en el año en curso, estamos presentando<br />

el libro <strong>Panorámica</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> pintura siglo XX: muestra Puntos Cardinales, que<br />

registra los momentos c<strong>la</strong>ve <strong>de</strong>l arte pictórico salvadoreño <strong>de</strong>l siglo XX, que son<br />

parte <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> colección permanente <strong>de</strong>l MARTE. Museo y libro, en cualquier tiempo<br />

y lugar, forman parte esencial <strong>de</strong>l universo <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> cultura humana. Las dos obras,<br />

cado una por sí misma, son un acontecimiento <strong>de</strong>l espíritu, <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> historia y <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong>s<br />

más profundas raíces en <strong>la</strong>s que se sustentan <strong>la</strong> vida y <strong>la</strong> civilización.<br />

MARTE y el libro <strong>Panorámica</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> pintura siglo XX: muestra Puntos Cardinales<br />

serán, para siempre, el testimonio <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> huel<strong>la</strong> que han <strong>de</strong>jado, en <strong>la</strong> historia,<br />

quienes hicieron posible <strong>la</strong> realización <strong>de</strong> estas dos obras, que nos conducen a<br />

metas insospechadas no so<strong>la</strong>mente en el gozo estético y en el hecho artístico,<br />

sino más allá, en lo profundo <strong>de</strong>l espíritu, don<strong>de</strong> el arte nos da respuestas<br />

reve<strong>la</strong>doras sobre nuestra i<strong>de</strong>ntidad y nuestros valores como salvadoreños y<br />

salvadoreñas, <strong>de</strong> nuestro tiempo y <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong>s futuras generaciones.<br />

On May 22, 2003, filled with a sense of immnense pri<strong>de</strong> and satisfaction, we<br />

had the honor of granting El Salvador and all of its citizens the newly inaugurated<br />

Museo <strong>de</strong> Arte <strong>de</strong> El Salvador (El Salvador Museum of Art), MARTE. Now in 2004<br />

we have the pleasure of presenting the book Panorama of 20th Century Painting:<br />

Exhibition Cardinal Points, which celebrates the key moments of XX Century<br />

Salvadoran painting that are disp<strong>la</strong>yed in the museums permanent exhibition.<br />

In any given time and p<strong>la</strong>ce, museums and books are consi<strong>de</strong>red an essential<br />

part of human culture. Both of these works are important spiritual and historical<br />

accompishments that enrich the most profound roots of life and civilization.<br />

MARTE and the book Panorama of 20th Century Painting: Exhibition Cardinal<br />

Points will forever be testimony to those that have impacted history by helping<br />

to create these two invaluable works. These people have inspired the Salvadoran<br />

community to reach for higher goals, not only through an aesthetic appreciation of<br />

artistic accomplishments, but in the <strong>de</strong>epest sense of the Spirit—for art provi<strong>de</strong>s<br />

revealing answers about our i<strong>de</strong>ntity, our Salvadoran values, our present word and<br />

that of future generations.<br />

Prólogo<br />

PROLOGUE<br />

MARTE es el resultado <strong>de</strong>l trabajo conjunto <strong>de</strong> hombres y mujeres que han dado<br />

total soporte a lo que, al principio, fue un sueño y que ahora es una realidad que<br />

nutre <strong>de</strong> arte y cultura esa morada espiritual y emocional, ese inmenso y rico<br />

espacio <strong>de</strong> sentimientos, vivencias y memoria, abierto al intelecto y al sentido<br />

<strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> belleza a que todo ser humano <strong>de</strong>be aspirar para lograr un futuro mejor.<br />

12<br />

El libro <strong>Panorámica</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> pintura siglo XX: muestra Puntos Cardinales es el or<strong>de</strong>r to assure a better future.<br />

resultado <strong>de</strong>l trabajo <strong>de</strong> artistas y críticos, el cual ha sido posible editar e imprimir<br />

13<br />

gracias al generoso patrocinio <strong>de</strong>l Banco Agríco<strong>la</strong>, al haberlo incluido <strong>de</strong>ntro <strong>de</strong><br />

su Programa <strong>de</strong> Fomento Cultural.<br />

Por este medio, <strong>de</strong>jamos constancia <strong>de</strong> nuestros más sinceros agra<strong>de</strong>cimientos<br />

al Banco Agríco<strong>la</strong> y a sus directores, pero en especial a su presi<strong>de</strong>nte, licenciado<br />

Rodolfo Schildknecht, porque gracias a ellos es que ha sido posible realizar este<br />

aporte para documentar <strong>la</strong> obra <strong>de</strong> los artistas que han creado esta parte <strong>de</strong>l<br />

valioso patrimonio cultural <strong>de</strong> El Salvador.<br />

The museum is a result of the unf<strong>la</strong>gging support provi<strong>de</strong>d by the men and<br />

women who gave their time and effort in the hopes of transforming a dream<br />

into reality. Thanks to this <strong>de</strong>dicated team, the art and culture provi<strong>de</strong>d by<br />

MARTE now nurtures the Salvadoran spiritual reservoir— that immense and<br />

rich collection of emotions, experiences, and memories. This intellect and<br />

sense of beauty are qualities that all human beings aspire to cultivate in<br />

Thanks to the generous sponsorship granted by the Banco Agríco<strong>la</strong>’s cultural<br />

<strong>de</strong>velopment program, we were able to publish Panorama of 20th Century<br />

Painting: Exhibition Cardinal Points and unite the work of artists and critics.<br />

We are sincerely grateful to the Banco Agríco<strong>la</strong> and its directors, especially<br />

bank presi<strong>de</strong>nt Rodolfo Schildknecht for this opportunity, which allowed us<br />

to showcase the work of Salvadoran artists who have created an essential<br />

part of our cultural heritage.<br />

María Marta Papini <strong>de</strong> Rega<strong>la</strong>do<br />

PRESIDENTA DE LA ASOCIACIÓN MUSEO DE ARTE DE EL SALVADOR

Introducción<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

La expresión figurativa ha sido y es central en el <strong>de</strong>sarrollo artístico Figurative expression has been the central focus of El Salvador’s artistic<br />

<strong>Pintura</strong> <strong>de</strong> El Salvador, aproximaciones.<br />

Salvadoran painting—a perspective.<br />

<strong>de</strong>l país. En <strong>la</strong> muestra Puntos Cardinales encontramos un excelente <strong>de</strong>velopment. In the exhibition Cardinal Points, one can find excellent examples,<br />

ejemplo, aunque panorámico, representativo <strong>de</strong> lo que ha sido su proceso although panoramic, of strict formal processes and their thematic manifestations.<br />

La fascinación por <strong>la</strong> pintura ha acompañado siempre al hombre. Es <strong>la</strong> Our fascination with painting dates back to the beginning of humankind. An<br />

estrictamente formal y sus manifestaciones temáticas. Estamos <strong>de</strong> acuerdo We are in accordance with some art critics who c<strong>la</strong>im it is difficult to establish a<br />

interpretación antológica y fenomenológica, <strong>de</strong>positada sobre el muro, piedra, etching on a wall, rock, cloth, or paper is an ontological and phenomenological<br />

con algunos analistas cuando p<strong>la</strong>ntean que se hace difícil enumerar<br />

hierarchical or<strong>de</strong>r for artistic ten<strong>de</strong>ncies that are stagnant. Also, it is difficult to<br />

te<strong>la</strong> o papel, que el hombre creador ha <strong>de</strong>jado para <strong>la</strong> historia <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> civilización. interpretation created by man for the history of civilization. Painting focuses<br />

ten<strong>de</strong>ncias estancas para <strong>de</strong>finir y establecer ór<strong>de</strong>nes jerárquicos <strong>de</strong><br />

establish specific artistic movements, but one can refer to subjects and issues,<br />

Otra interpretación concierne a su capacidad <strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>spertar sentimientos basados on man’s capacity to awaken the aesthetic and emotional sensations this art<br />

c<strong>la</strong>sificación. Tampoco podría hab<strong>la</strong>rse <strong>de</strong> movimientos específicos, pero sí<br />

such as violence, that are connected to different periods in Salvadoran history.<br />

en <strong>la</strong> sensación estética y afectiva que produce. La pintura es el otro universo <strong>de</strong>l form produces. Painting becomes the viewer’s other universe, the visible and<br />

<strong>de</strong> temas y problemáticos re<strong>la</strong>cionados con <strong>la</strong>s diferentes épocas históricas<br />

Salvadoran painting is not about the artists liberty per se, rather the historical and<br />

14 <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> sociedad salvadoreña, como lo violencia por ejemplo. No se trata <strong>de</strong><br />

15<br />

cultural circumstances that caused the multiplicity of notable styles recognized<br />

espectador, es el mundo visible, a <strong>la</strong> vez misterioso, que le ro<strong>de</strong>a, palpándose en<br />

el tratamiento <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> intangibilidad <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong>s cosas, el que mira se reconoce en una<br />

realidad inventada que <strong>de</strong>spierta su imaginación y sus emociones. Su re<strong>la</strong>ción<br />

con el<strong>la</strong> es visual, intelectual y afectivo. El universo conocido y no conocido, se<br />

hace verosímil y tangible cuando se acorta <strong>la</strong> distancia <strong>de</strong> lo posible entre <strong>la</strong><br />

pintura como documento y el hombre como protagonista y espectador.<br />

Cada época ha <strong>de</strong>cretado <strong>la</strong> muerte a <strong>la</strong> pintura, para luego compren<strong>de</strong>r que es<br />

tan necesaria, como escribir y leer, al inventar nuevas direcciones a seguir y nuevas<br />

maneras <strong>de</strong> ser inédito. La pintura en El Salvador no ha escapado a esta circunstancia;<br />

como manifestación sensible <strong>de</strong>l espíritu, su amplio campo, ofrece interpretaciones<br />

variadas que podrían ser en cuanto a lugar <strong>de</strong> i<strong>de</strong>ntida<strong>de</strong>s no transitorias, <strong>de</strong>positaria<br />

<strong>de</strong> resistencia a <strong>la</strong>s adversida<strong>de</strong>s, al paso polo a polo y <strong>de</strong> direcciones don<strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong><br />

<strong>la</strong>boriosidad <strong>de</strong>scubre procedimientos y métodos, e indica una <strong>de</strong>dicación auténticao<br />

para producir un cuerpo pictórico que <strong>de</strong>finitivamente no pue<strong>de</strong> ser ignorado.<br />

mysterious world that surrounds him and reminds him of the intangibility of<br />

things. The viewer recognizes this invented reality that stirs his imagination.<br />

His re<strong>la</strong>tionship with art is visual, intellectual, and emotional. When painting<br />

comes as close as possible to documenting humankind as protagonists and<br />

viewers of known and unknown worlds, these realities become interchangeable<br />

and tangible.<br />

Every <strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong> has <strong>de</strong>creed the <strong>de</strong>ath of painting, only to <strong>la</strong>ter invent completely<br />

new directions and perspectives and some to un<strong>de</strong>rstand that this art is as<br />

necessary as writing and reading. Painting in El Salvador has not escaped this<br />

evolution. The broad field of painting, a conscious menifestation of the spirit,<br />

offers varied interpretations. The clearly <strong>de</strong>fined i<strong>de</strong>ntities of Salvadoran painters<br />

<strong>de</strong>monstrate a resistance to adversity and an exploration of all extremes. The<br />

hard work of Salvadoran artists has produced new methods and techniques and<br />

shows an authentic <strong>de</strong>dication to producing art that cannot be ignored.<br />

<strong>la</strong> libertad per se <strong>de</strong>l artista <strong>de</strong> esta parte <strong>de</strong> Centroamérica, han sido sus<br />

circunstancias históricas y culturales los propiciatorias <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> multiplicidad <strong>de</strong><br />

estilos notables <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> los años cuarenta, época que, para sistematizar su<br />

historia, po<strong>de</strong>mos acordar como el comienzo <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> mo<strong>de</strong>rnidad. Aquí hay un<br />

punto a consi<strong>de</strong>rar, en cuanto a <strong>la</strong> re<strong>la</strong>ción diacrónica con América Latina,<br />

don<strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> multiplicidad <strong>de</strong> ten<strong>de</strong>ncias es una característica <strong>de</strong>finida <strong>de</strong> los<br />

años ochenta. Si bien, se ha p<strong>la</strong>nteado que el siglo XX y el mo<strong>de</strong>rnismo<br />

entran tardíamente a América Latina, El Salvador en los años cincuenta<br />

ignora <strong>la</strong>s ten<strong>de</strong>ncias en boga en el continente, por ejemplo <strong>la</strong> abstracción<br />

geométrica, continuando su pintura siendo obstinadamente figurativa, con<br />

marcado acento expresionista, aunque en décadas posteriores algunos<br />

artistas giran hacia una abstracción más bien orgánica o lírica, sin <strong>de</strong>l todo<br />

<strong>de</strong>jar <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong>do <strong>la</strong> referencia figurativa, como Raúl E<strong>la</strong>s Reyes, Carlos Cañas,<br />

Roberto Galicia, César Menén<strong>de</strong>z, Rodolfo Molina, y en algunos momentos<br />

Roberto Huezo, abandonándolo casi inmediatamente para volver al lugar <strong>de</strong><br />

since the 1940s, a period that historically marks the beginning of Mo<strong>de</strong>rnism<br />

in the international world. However, there is one point to consi<strong>de</strong>r regarding<br />

Mo<strong>de</strong>mism’s diachronic re<strong>la</strong>tionship with Latin America where the varied<br />

ten<strong>de</strong>ncies that <strong>de</strong>veloped are a <strong>de</strong>finite characteristic of the 1980s. lt has been<br />

stated that XX century art and Mo<strong>de</strong>rnism entered Latin America <strong>la</strong>te and that<br />

El Salvador in the 1950s ignored the ten<strong>de</strong>ncies that were in vogue in other<br />

parts of the world, such as geometric abstraction. That is why most Salvadoran<br />

painting continues being obstinately figurative with a marked Expressionist<br />

influence. In <strong>la</strong>ter <strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong>s, some artists lean towards an organic or Ipyrical<br />

abstraction without completely abandoning the figurative reference. Examples<br />

inclu<strong>de</strong> Raúl E<strong>la</strong>s Reyes, Carlos Cañas, Roberto Galicia, Céscr Menén<strong>de</strong>z, Rodolfo<br />

Molina, and at times, Roberto Huezo. These artists abandoned abstraction almost<br />

immediately and returned to their figurative starting point. The Salvadoran, and

partido figurativo. Decididamente <strong>la</strong> sensibilidad <strong>de</strong>l artista salvadoreño, y en general <strong>de</strong>l<br />

centroamericano, es hacia <strong>la</strong> figuración. Tal vez un sentimiento <strong>de</strong> culturas ancestrales<br />

está en el sustrato genético <strong>de</strong> cada uno <strong>de</strong> ellos, al <strong>la</strong>do <strong>de</strong> su contexto cultural.<br />

La única comparación posible entre el <strong>de</strong>sarrollo <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> pintura en El Salvador<br />

con el <strong>de</strong> América Latina, se sostiene en función <strong>de</strong> su calidad y, <strong>de</strong>spués <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong><br />

década <strong>de</strong>l cuarenta, en ciertas coinci<strong>de</strong>ncias temáticas. En estas dos direcciones<br />

sus re<strong>la</strong>ciones son parale<strong>la</strong>s y directas, no solo en lo que se refiere a <strong>la</strong> imagen<br />

misma figurativa, sino también a algunos conceptos teóricos que fundamentan<br />

su <strong>de</strong>sarrollo a lo <strong>la</strong>rgo <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> mitad siglo XX. La figuración, a veces manifiesta<br />

en metáforas visuales perturbadoras, otras en inquietante expresionismo, o en<br />

poéticas provocadoras, se pone al servicio <strong>de</strong> lo visible como expresión autónoma,<br />

hurgando en el contexto social como posibilidad primera <strong>de</strong> representación.<br />

Ya apuntamos que <strong>la</strong> mo<strong>de</strong>rnidad entra a El Salvador bastante avanzado el siglo<br />

XX. Hasta prácticamente finales <strong>de</strong> los años cuarenta, se produce una pintura ya<br />

agotada en América Latina <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> principio <strong>de</strong>l siglo, cuando el paisaje, escenas<br />

costumbristas, retratos, personajes pintorescos, buscaban mostrar <strong>la</strong> expresión<br />

<strong>de</strong> una i<strong>de</strong>ntidad cultural. Podría consi<strong>de</strong>rarse que es a portir <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> década <strong>de</strong> los<br />

cincuenta, cuando se produce un cambio sustancial en <strong>la</strong> producción pictórica,<br />

protegido por los artistas <strong>de</strong> rebelión <strong>de</strong> una joven generación <strong>de</strong> artistas en<br />

etapa formativa, con el protagonismo <strong>de</strong>l Grupo <strong>de</strong> Pintores In<strong>de</strong>pendientes,<br />

li<strong>de</strong>rizado por Carlos Cañas. La primera mitad <strong>de</strong>l siglo XX, se <strong>de</strong>sliza sin<br />

contratiempo. Los preceptos académicos conforman el menú formal <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong><br />

factura pictórica. Un dato que l<strong>la</strong>ma <strong>la</strong> atención son <strong>la</strong> salida <strong>de</strong> artistas<br />

salvadoreños a estudiar a Europa <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> principio <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> década <strong>de</strong> 1910.<br />

Algunos regresan años <strong>de</strong>spués, como Carlos Alberto Imery, quien en 1972<br />

funda <strong>la</strong> Escue<strong>la</strong> Nacional <strong>de</strong> Artes Gráficas aparece, sobre <strong>la</strong> experiencia <strong>de</strong><br />

su escue<strong>la</strong> privada. Unos cuantos años pasaron. La pintura registra avances<br />

gracias a los aportes <strong>de</strong> artistas viajeros, cuando aparece en el horizonte<br />

generally the Central American, artistic sensibility favors figuration. Perhaps,<br />

in addition to the cultural context, Salvadoran artists curry in their genetic<br />

substratum emotions linked to ancestravol cultures.<br />

The <strong>de</strong>velopment of Salvadoran painting and Latin American painting can be<br />

compared only by the quality of both and by certain coinci<strong>de</strong>nces in theme<br />

present after the 1940s. These two points of comparison are parallel because<br />

they refer to the figurative image and to certain theories that are the foundation<br />

of Salvadoran art in the XX century. Figuration sometimes manifest perturbing<br />

visual metaphors; other times it results in a moving expressionism or evocative<br />

poetry. Salvadoran artists prefer the social context as their first choice of<br />

representation, and this painting becomes an autonomous expression.<br />

Until the end of the 1940s Salvadoran painters produced art tha was already<br />

exhausted in Latin America at the beginning of the XX century. Their <strong>la</strong>ndscapes,<br />

traditional scenes, and picturesque portraits <strong>de</strong>monstrate a search for their<br />

cultural i<strong>de</strong>ntity. It is not until the1950s that a substantial change occrred in<br />

painting thanks to a rebellious young generation of artists still in their formative<br />

years and backed by the In<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nt Group of Painters led by Carlos Cañas.<br />

The first half of the XX century passed without any setbacks. Aca<strong>de</strong>mic precepts<br />

conformed to the formal menu of the pictorial frame. One notable <strong>de</strong>tail is<br />

the fact that Salvadoran artists began to leave the country to study in Europe<br />

in1910, Some returned a few years <strong>la</strong>ter, such as Carlos Alberto Imery, who<br />

foun<strong>de</strong>d the National School of Graphic Arts in 1912 based on his private school<br />

experience. A few years passed and Salvadoran painting advanced thanks to<br />

the contributions ma<strong>de</strong> by the artists who studied abroad. Then, the aca<strong>de</strong>mic<br />

teaching of Spanish painter Valero Lecha, in his private art aca<strong>de</strong>my foun<strong>de</strong>d<br />

in 1939, became the pivotal point of Salvadoran painting in the second half of<br />

the XX century.<br />

otras propuestas teóricas, obviando <strong>la</strong> falsa premisa <strong>de</strong> que El Salvador, por país<br />

pequeño no ha tenido una producción artística <strong>de</strong>stacada; y basándose en el<br />

espacio cultural y social, en el que el artista nacional se ha movido, y también el<br />

internacional que le ha tocado en suerte. No es extraño encontrar que una buena<br />

parte <strong>de</strong> sus artistas han vivido fuera <strong>de</strong> sus fronteras en algún momento <strong>de</strong> su<br />

vida, experiencia que le liga a un espíritu universal que sabiamente entronca con<br />

<strong>la</strong> expresión exaltada, algunas veces trágicas, <strong>de</strong> su país natal. Plásticamente, en<br />

<strong>la</strong> ejecución <strong>de</strong> esta pintura, aun en el más <strong>de</strong>licado paisaje, se nota <strong>la</strong> violencia<br />

representada en su invisibilidad como realidad y en otras, es el hombre agonizante<br />

atacado por los perros <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> guerra, el terror <strong>de</strong>l <strong>de</strong>samparo o <strong>la</strong> in<strong>de</strong>fensión,<br />

arropado por <strong>la</strong> certeza <strong>de</strong> no tener <strong>de</strong>stino, sentimientos que correspon<strong>de</strong>n a <strong>la</strong><br />

visibilidad <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> realidad. No es el caso, entonces, el esperar <strong>de</strong> este artista una posición<br />

comp<strong>la</strong>ciente, son <strong>la</strong>s rasgaduras <strong>de</strong>l corazón que lo llevan a <strong>la</strong> insolencia creadora.<br />

Puntos Cardinales, <strong>la</strong> propuesta <strong>de</strong>l curador Luis Croquer, son puntos <strong>de</strong> partida<br />

para establecer una aproximación conceptual a partir <strong>de</strong> los varios aspectos que ha<br />

tocado <strong>la</strong> pintura salvadoreña a lo <strong>la</strong>rgo <strong>de</strong> su <strong>de</strong>sarrollo en el siglo XX. Partiendo <strong>de</strong><br />

una visión panorámica, propone <strong>de</strong>finiciones contenidas en tres núcleos temáticos:<br />

Memoria y cultura, Rostros y figuras, Realidad y fantasía y Entorno y materia. No<br />

se trata <strong>de</strong> una or<strong>de</strong>nación cronológica. Tanto en lo visual como en lo teórico es un<br />

análisis que abarca, a gran<strong>de</strong>s rasgos, el proceso que ha marcado <strong>la</strong> pintura en el<br />

país. Por muchas razones, solo un grupo <strong>de</strong> artistas ha sido seleccionado, lo que<br />

no implica que muchos otros no pudieran, perfectamente, estar incluidos en estos<br />

núcleos. Nombrar los seleccionados no es preciso en esta corta introducción, ya que<br />

están en el texto central <strong>de</strong> este libro, pero si se hace imprescindible mencionar<br />

algunos <strong>de</strong> aquellos que conforman el amplio espectro pictórico <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> plástica <strong>de</strong><br />

El Salvador. Podría comenzarse con dos artistas mujeres, Titi Esca<strong>la</strong>nte y Negra<br />

Álvarez, quienes también han realizado obra escultórica, y continuar con otras cuya<br />

obra se sitúa en el acontecer <strong>de</strong>l presente artístico <strong>de</strong>l país, Mayra Barraza, Ana<br />

their lives since it is an experience that binds them with a universal spirit and<br />

which wisely connects them with the exalted and sometimes tragic expressions<br />

of their birth country. Even in the most <strong>de</strong>licate <strong>la</strong>ndscapes, violence is<br />

represented, and one can see man attacked by the dogs of war and the terror<br />

of abandonment and vulnerability. Cloaked with the certainty of possessing no<br />

<strong>de</strong>stiny, Salvadoran artists express feelings that correspond to their realities. It<br />

is not expected, then, for the Salvadoran artist to be in a comp<strong>la</strong>cent position; it<br />

is the wounds of his heart that lead him to his creativity.<br />

Luis Croquer’s proposal, Cardinal Points, refers to certain starting points in or<strong>de</strong>r<br />

to establish a conceptual perspective of the <strong>de</strong>velopment of Salvadoran painting<br />

throughout the XX century. Beginning with a panoramic vision, he proposes<br />

four thematic categories: Memory and Culture, Portraits and Figures, Reality<br />

and Fantasy, and Environment and Matter. The exhibition is not arranged<br />

chronologically. Croquer’s visual and theoretical analyses inclu<strong>de</strong>, on a <strong>la</strong>rge<br />

scale, the <strong>de</strong>velopment of Salvadoran painting. For many reasons, only certain<br />

artists have been chosen — but that does not mean that several other artists<br />

could not fit perfectly into these categories. It is unnecessary to name all of the<br />

selected artists in this brief introduction since they are inclu<strong>de</strong>d in the central text<br />

of this book, but it is imperative to mention some of the other important artists<br />

who constitute the wi<strong>de</strong> spectrum of Salvadoran painting.<br />

We could begin mentioning two female artists, Titi Esca<strong>la</strong>nte and Negra Álvarez,<br />

who also are sculptors, and other contemporary Salvadoran artists that inclu<strong>de</strong><br />

Mayra Barraza, Ana María Martínez, Licry Bicard, María Khan, Elisa Archer,<br />

Conchita Kuny Mena, and Sonia Me<strong>la</strong>ra. In addition I should add the following<br />

artists (listed in no particu<strong>la</strong>r or<strong>de</strong>r): Mauricio Linares, Ricardo Carbonell, Mauricio<br />

Mejía, Armando Solis, Luis Lazo, Walter Iraheta, Rafael Vare<strong>la</strong>, Rodríguez Preza,<br />

Bernardo Crespín, Héctor Hernán<strong>de</strong>z, El Aleph, Hernán<strong>de</strong>z Alemán, Fernando<br />

Llort, Augusto Crespín, Ro<strong>la</strong>ndo Reyes, Antonio Lara,Catolo, Chilín, and Miguel<br />

Ángel Orel<strong>la</strong>na. Still, this list appears to be incomplete, and accepting the risk<br />

16 <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> plástica y <strong>la</strong> enseñanza artística local el español Valero Lecha, cuya A new and important generation of artists, hea<strong>de</strong>d by painters such as Julia Díaz,<br />

María Martinez, Licry Bicard, María Khan, Elisa Archer, Conchita Kuny Mena y Sonia of leaving many others unmentioned, I have provi<strong>de</strong>d only the names of those<br />

whose work I am most familiar with.<br />

17<br />

aca<strong>de</strong>mia privada <strong>de</strong> arte, que comienza en 1939, se convertirá en centro<br />

pivotal <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> historia <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> pintura solvadoreña en <strong>la</strong> segundo mitad <strong>de</strong>l<br />

siglo. Se hab<strong>la</strong> <strong>de</strong> una nueva e importante generación, con Julia Díaz, Noé<br />

Canjura y Raul E<strong>la</strong>s Reyes a <strong>la</strong> cabeza, que contribuirá a dar continuidad a <strong>la</strong><br />

<strong>la</strong>bor iniciada por los fundadores <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> pintura salvadoreña. Siguiendo esta<br />

dirección, Julia Díaz, en 1958, funda <strong>la</strong> Galería Forma, que rápidamente se<br />

convierte en un espacio cultural generador <strong>de</strong> conocimiento y cultura.<br />

También al amparo <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> artista y su galería, prácticamente otra generación emergerá<br />

como relevo a <strong>la</strong> <strong>de</strong>l taller <strong>de</strong> Valero Lecha, con i<strong>de</strong>as novedosas logicamente acor<strong>de</strong>s<br />

con uno realidad diferente, y con <strong>de</strong>seos <strong>de</strong> renovar el medio artístico <strong>de</strong>l país.<br />

Reunir obras para una exposición, seleccionando entre una producción importante <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> el<br />

punto <strong>de</strong> vista histórico y artístico, y a ser consi<strong>de</strong>rado una suerte <strong>de</strong> antología <strong>de</strong> un siglo,<br />

<strong>de</strong>be consi<strong>de</strong>rarse una proeza curatorial. La consecuencia inmediata resulta en lo necesidad<br />

<strong>de</strong> continuar el estudio <strong>de</strong>l arte salvadoreño en p<strong>la</strong>nteamientos posteriores que abarquen<br />

Noé Canjura, and Raul E<strong>la</strong>s Reyes continued to contribute to the advancement<br />

of Salvadoran painting. ln 1958, Julia Díaz inaugurated the Forma Gallery,<br />

which quickly became a venue that promoted knowledge and culture. Un<strong>de</strong>r her<br />

tute<strong>la</strong>ge and through her gallery, a new generation emerged with new i<strong>de</strong>as in<br />

tune with a <strong>de</strong>sire to renew the artistic sector of the country.<br />

Selecting works for an exhibition with historic and artistic priorities in mind and<br />

that conserve as an anthology of painting for an entire century is a significant<br />

curatorial feat. The inmediate consequence is the recognized need to continue<br />

investigating Salvadoran art in the future. This in turn, will provi<strong>de</strong> other<br />

perspectives hat will inclu<strong>de</strong> other theoretical proposals that ignore the false<br />

c<strong>la</strong>im that El Salvador has not produced renowned artists because its a small<br />

country. National artists have been just as involved as international artists<br />

in the social and cultural world that surounds them. lt is not surprising to<br />

discover that many Salvadoran artists have lived abroad at some point in<br />

Me<strong>la</strong>ra. Junto a el<strong>la</strong>s, sin un or<strong>de</strong>n preciso, pero si consciente <strong>de</strong> que su obra es<br />

importante para lo historia <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> pintura local, recordamos a artistas como Mauricio<br />

Linares, Ricardo Carbonell, Mauricio Mejía, Armando Solis, Luis <strong>la</strong>zo, Walter Iraheta,<br />

Rafael Vare<strong>la</strong>, Rodríguez Preza, Bernardo Crespín, Héctor Hernán<strong>de</strong>z, El Aleph,<br />

Hernán<strong>de</strong>z Alemán, Fernando Llort, Augusto Crespín, Ro<strong>la</strong>ndo Reyes, Antonio Lara,<br />

Catolo, Chilín y Miguel Ángel Orel<strong>la</strong>na. Esta lista sigue pareciendo incompleta, y<br />

asumiendo el riesgo <strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>jar muchos afuera, nos remitimos a aquellos cuya obra<br />

conocemos más <strong>de</strong> cerca.<br />

Un análisis <strong>de</strong>l conjunto <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> obra <strong>de</strong> estos artistas y <strong>de</strong> los que componen <strong>la</strong> propuesta<br />

Puntos Cordinales, muestra <strong>la</strong> diversidad temática que abordan, junto a una i<strong>de</strong>ntidad<br />

personal y simultáneamente otra ligada al contexto en el que <strong>la</strong> ha producido. También<br />

<strong>de</strong>bemos <strong>de</strong>finir <strong>la</strong>s angustias existenciales, y terrenales, que <strong>de</strong>finitivamente permean<br />

su circunstancia en el medio social que les ha tocado. Pue<strong>de</strong> resaltarse un absoluto<br />

original, enraizado en <strong>la</strong> carga i<strong>de</strong>ológica. (no partidista, como diría el maestro<br />

An analysis of these artists´ works and those that are inclu<strong>de</strong>d in Cardinal Points<br />

<strong>de</strong>monstrates the diverse themes they address. These artists simultaneously<br />

<strong>de</strong>al with personal i<strong>de</strong>ntity and with an i<strong>de</strong>ntity rooted in their cultural and<br />

social context. Within the existential and human anguish that permeates their<br />

circumstances in the social world, these artists inhabit a primal absolute, one<br />

that is rooted with an i<strong>de</strong>ological and non-political charge, as master painter<br />

Carlos Cañas would exp<strong>la</strong>in. When referring to the alienation of the artist who<br />

is locked within the four walls of his country, yet at the same time longs to live<br />

in the <strong>la</strong>rger universe, one can evaluate both situations as perfectly valid and<br />

justifiable because they are rooted to an interior creativity that is cyclically lost<br />

and found. Following this arbitrary equation, the figurative image becomes sign<br />

and symbol of this social i<strong>de</strong>ology that becomes an artistic i<strong>de</strong>ology: the environment<br />

influences the artist to become the creator of his own inescapable reality. The<br />

artists´ ghosts are summerized into what the artist is and wants to be.

Carlos Cañas). Pue<strong>de</strong> también hab<strong>la</strong>rse <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> alienación <strong>de</strong>l artista a <strong>la</strong>s cuatro pare<strong>de</strong>s<br />

<strong>de</strong> su país, a <strong>la</strong> vez que <strong>de</strong>sea ser y estar en el universo, Ambas situaciones son<br />

perfectamente válidas y justificables <strong>de</strong> acuerdo a una intimidad creadora perdida y<br />

recobrada, o recobrada y luego perdida. Siguiendo esta ecuación arbitraria, <strong>la</strong> imagen<br />

figurativa se hace signo y símbolo <strong>de</strong> esa i<strong>de</strong>ología social convertida en artística, el<br />

entorno empuja al artista a convertirse en <strong>de</strong>miurgo <strong>de</strong> su propia, e ineludible, realidad.<br />

Son sus fantasmas, resumidos en lo todo que es y que quiere ser.<br />

Cada uno ellos ha seleccionado el tema que se acerca a su sensibilidad, permitiéndole<br />

esta <strong>de</strong>cisión, establecer un or<strong>de</strong>n en <strong>la</strong> representación figurativa. El cuerpo <strong>de</strong> esta repre<br />

sentación es estable y cargado <strong>de</strong> significaciones semánticas, no con carácter semiótico,<br />

Se trata <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> aprehensión <strong>de</strong>l espacio, <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> liberación <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> energía cromática en su<br />

más altos grados <strong>de</strong> contrastes entre luz y sombra y <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> coherencia <strong>de</strong>l discurso visual.<br />

Si bien son caracteristicas generales aplicables a <strong>la</strong> producción pictórica <strong>de</strong> El Salvador, es<br />

necesario enfatizar en <strong>la</strong> particu<strong>la</strong>ridad <strong>de</strong> cada artista, en <strong>la</strong> individualidad que persigue<br />

<strong>la</strong> vocación <strong>de</strong> no parecerse al <strong>de</strong> al <strong>la</strong>do, De allí <strong>la</strong> dificultad <strong>de</strong> analizarlo en términos<br />

<strong>de</strong> evolución historicista, más no como proceso artístico, algo diferente a <strong>la</strong> historia <strong>de</strong><br />

otras partes <strong>de</strong> América Latina. Algunos ejemplos rasantes, a pesar <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> influencia, <strong>de</strong><br />

Valera Lecha en su históricamente famosa aca<strong>de</strong>mia <strong>de</strong> pintura, no <strong>de</strong>ja escue<strong>la</strong>, ni<br />

tampoco Julia Díaz; para llegar un poco más lejos en el tiempo, ni siquiera los paisajistas<br />

<strong>de</strong> principio <strong>de</strong> siglo, o el grupo <strong>de</strong> artistas in<strong>de</strong>pendientes, quienes entendieran <strong>la</strong><br />

in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>ncia artística como el cuestionamiento <strong>de</strong>l aca<strong>de</strong>micismo <strong>de</strong>cimonónico.<br />

Each one of these Salvadoran artists has chosen the subject that most reflects<br />

his sensibilities and allows him to establish an or<strong>de</strong>r through figurative<br />

representation. The exhibition Cardinal Points is charged with semantic<br />

meanings, not with semiotics. lt <strong>de</strong>als with an un<strong>de</strong>rstanding of space and a<br />

the freedom of chromatic energy that shows the greatest possible contrasts<br />

between light and shadow and the coherence of a visual discourse. These are<br />

general characteristics applicable to the production of Salvadoran painting, but it<br />

is necessary to emphasize the uniqueness of the artists: each reflects a particu<strong>la</strong>r<br />

individuality. Different from other Latin American art, Salvadoran painting is<br />

difficult to analyze in terms of historical evolution but is easier to un<strong>de</strong>rstand<br />

according to the artistic process. Some clear examples are as follows: in spite<br />

of the influence of Valero Lecha’s historically famous painting aca<strong>de</strong>my, he did<br />

not leave any disciples of his artistic ten<strong>de</strong>ncies. Neither did Julia Díaz, the early<br />

<strong>la</strong>ndscape artists, nor the in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nt artists that interpreted artistic freedom as<br />

the questioning of the XIX century aca<strong>de</strong>mic mo<strong>de</strong>l.<br />

El Salvador, as other Central American countries, has suffered the hardships<br />

of political and social conflict and the ultimate tragedy — war. And <strong>de</strong>spite<br />

of this, art, in its different dimensions, has soared over the bleak horizon of<br />

terror and anguish. lt has left a legacy in its manifestations of violence, in<br />

songs a love and peace, and in a culture that is conscious of the magnificence<br />

of nature. Salvadoran artists <strong>de</strong>al with these themes in their expressions of<br />

passion and pain rather than through contemp<strong>la</strong>tive or submissive attitu<strong>de</strong>s.<br />

Para finalizar, recor<strong>de</strong>mos que como otros países centroamericanos, El Salvador ha On the contrary— These artists are confrontational and they question the<br />

sufrido <strong>la</strong> tragedia <strong>de</strong>l conflicto político, social y lo peor: <strong>la</strong> guerra. Y por encima <strong>de</strong> todo present, anachronistic aesthetics, and aca<strong>de</strong>mic comventions. lt appears that<br />

esto, el arte, en diferentes dimensiones se ha elevado sobre el horizonte <strong>de</strong>l terror y <strong>la</strong> all Salvadoran artists enthusiastically emphasize creativity and f<strong>la</strong>tly negate<br />

angustia, para <strong>de</strong>jar su testimonio, muchas <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong>s veces manifiestos <strong>de</strong> violencias, otras pessimism and indifference. They assume that art is a way of staying alive and<br />

cantos <strong>de</strong> amor y paz, y otras <strong>la</strong> poética <strong>de</strong> una cultura asentada en <strong>la</strong> magnificencia <strong>de</strong> preserving the culture of their country. Just as Gustave Courbet proposed in the<br />

<strong>la</strong> naturaleza. La temática asumida, con pasión y dolor, por el artista salvadoreño, no mid XIX century, Salvadorans — masters of their creative freedoms — have<br />

trata una actitud contemp<strong>la</strong>tiva, ni sumisa. Todo lo contrario, se presenta combativa y become witnesses of the present and artists of their time.<br />

18 cuestionadora <strong>de</strong>l presente, <strong>de</strong> estéticas anacrónicas y <strong>de</strong> convencionalismo académicos;<br />

19<br />

pareciera que todos enfatizan el sí a <strong>la</strong> creatividad y al negar rotundamente el pesimismo<br />

y <strong>la</strong> indiferencia, asumen que el arte es una manera <strong>de</strong> estar vivo y <strong>de</strong> preservar <strong>la</strong> cultura<br />

<strong>de</strong>l país. Dueño <strong>de</strong> una plena libertad creadora, se insta<strong>la</strong> como testigo <strong>de</strong> su presente,<br />

como artista <strong>de</strong> su tiempo, como lo pedía Gustave Courbet a mediados <strong>de</strong>l siglo XIX.<br />

Bélgica Rodríguez<br />

CRÍTICA DE ARTE

20 21

Puntos Cardinales<br />

Propuesta curatorial<br />

Cardinal Points: Curatorial Proposal<br />

Introducción<br />

Introduction<br />

Puntos Cardinales busca dar un giro al conocimiento que tenemos <strong>de</strong> nuestro arte, agrupando Cardinal Points seeks to re-envision the general knowledge of Salvadoran art by<br />

<strong>la</strong> obra <strong>de</strong> manera temática y ayudándonos, asi, a <strong>de</strong>tectar <strong>la</strong>s conexiones con los géneros grouping the works thematically in or<strong>de</strong>r to <strong>de</strong>fine connections to c<strong>la</strong>ssic genres<br />

Puntos Cardinales es una recontextualización <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong>s dos colecciones públicas más Cardinal Points is a re-contextualization of El Salvador’s two most important<br />

clásicos <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> pintura, e i<strong>de</strong>ntificar los temas recurrentes en nuestro arte, a evi<strong>de</strong>nciar <strong>la</strong>s of paintings and i<strong>de</strong>ntify the recurring subjects in our art. These groupings also<br />

22 23<br />

importantes <strong>de</strong>l país, <strong>la</strong> Colección Nacional y <strong>la</strong> Colección Forma, que por primera<br />

vez se unen, complementadas por un pequeño número <strong>de</strong> obras provenientes <strong>de</strong><br />

colecciones privadas, para contar una so<strong>la</strong> historia que refleja algunos momentos<br />

c<strong>la</strong>ve en el <strong>de</strong>sarrollo <strong>de</strong>l arte salvadoreño y que yuxtapone <strong>la</strong>s propuestas <strong>de</strong><br />

nuestros artistas a nivel temático para mostrar <strong>la</strong>s constantes, <strong>la</strong>s contradicciones<br />

y también <strong>la</strong> introducción <strong>de</strong> lenguajes artísticos que abren posibilida<strong>de</strong>s para los<br />

artistas activos hoy en día.<br />

Crear una propuesta curatorial que abarcara gran parte <strong>de</strong>l siglo XX y que, al<br />

mismo tiempo, incorporara piezas importantes <strong>de</strong> nuestro patrimonio artístico y<br />

cultural —un universo diverso y finito— fue un reto y un <strong>de</strong>safío importante.<br />

Como en toda exposición <strong>de</strong> colecciones, estudiar, comparar y contrastar los<br />

fondos ha sido una tarea básica para, a partir <strong>de</strong> sus contenidos, formu<strong>la</strong>r una<br />

propuesta que contribuya a dar una aproximación crítica a <strong>la</strong> complejidad y<br />

riqueza <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> producción artística salvadoreña en el periodo 1900-1992.<br />

public collections: the Colección Nacional (National Collection) and the Colección<br />

Forma (Forma Collection). These two collections have been united for the first<br />

time, complemented with a small number of privately owned works, to present<br />

a common history that reflects key moments in the <strong>de</strong>velopment of Salvadoran<br />

art. Cardinal Points juxtaposes Salvadoran paintings through thematic segments<br />

in or<strong>de</strong>r to disp<strong>la</strong>y consistencies and contradictions and also presents artistic<br />

forms of expression that established creative possibilities for artists who are<br />

still active today.<br />

Creating a curatorial proposal that encompasses a <strong>la</strong>rge part of the XX century<br />

and at the same time incorporates important pieces of our artistic and cultural<br />

patrimony—a diverse and finite universe —was a significant challenge. As in<br />

all collection exhibitions, the basic task was to study, compare, and contrast<br />

the artworks in or<strong>de</strong>r to formu<strong>la</strong>te a proposal that would provi<strong>de</strong> a critical<br />

perspective of the complexity and richness of El Salvador’s artistic production<br />

during 1900-1992.<br />

contradicciones que surgen en <strong>la</strong> plástica salvadoreña, a conocer los momentos c<strong>la</strong>ves en <strong>la</strong><br />

historia <strong>de</strong>l arte <strong>de</strong>l país y a p<strong>la</strong>ntear <strong>la</strong>s conexiones que podrían existir con el arte que se<br />

produce en diferentes periodos en otras partes <strong>de</strong>l mundo.<br />

El arte en El Salvador, a pesar <strong>de</strong> ser rico en produccion, en su mayor parte no es<br />

consecuencia <strong>de</strong> procesos <strong>de</strong> formación artística superior, aunque un número<br />

importante <strong>de</strong> artistas, sobre todo el inicio <strong>de</strong>l sigio XX, fueron educados<br />

rigurosamente en aca<strong>de</strong>mias <strong>de</strong> Europa, Estados Unidos y México. La formación<br />

artística en el país, al margen <strong>de</strong> algunos fallidos intentos, ha permanecido<br />

fuera a <strong>la</strong>s políticas ecucativas estatales, lo que ha generado <strong>la</strong> proliferación <strong>de</strong><br />

aca<strong>de</strong>mias privados a lo <strong>la</strong>rgo <strong>de</strong> nuestra historia reciente, que han propuesto<br />

sus propios mo<strong>de</strong>los <strong>de</strong> enseñanza, a menudo como refuerzos <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> <strong>de</strong>streza<br />

individual y <strong>la</strong> i<strong>de</strong>a <strong>de</strong> oficio, así como con una marcada predilección por <strong>la</strong><br />

figuración, lo que no ha favorecido <strong>la</strong> exploración <strong>de</strong> otros lenguajes.<br />

serve as further evi<strong>de</strong>nce of implicit contradictions, helping us to recognize<br />

some key moments in the country´s art history and the possible connections<br />

that could exist between art produced in diferent periods throughout the world.<br />

Although Salvadoran art is rich in terms of production, the majority is not a<br />

result of formal artistic training, although a number of important artists at the<br />

begining of the XX century were rigorously trained in European aca<strong>de</strong>mies, the<br />

United States, and Mexico. Artistic training in El Salvador, with the exception<br />

of some failed attempts, has been mostly exclu<strong>de</strong>d in governmental education<br />

policies. This has resulted in a proliferation of private aca<strong>de</strong>mies throughout our<br />

recent history that have proposed their own teaching mo<strong>de</strong>ls and have often<br />

promoted and focused on individual skill and the i<strong>de</strong>a of a vocation, with a<br />

marked bias towards figuration, that has not favored the exploration of other<br />

artistic forms of expression.

Tan variada profusión <strong>de</strong> mo<strong>de</strong>los <strong>de</strong> enseñanza ha dado paso también a propuestas<br />

que, a primera vista, parecen aleatorias, pero que en realidad se alimentan <strong>de</strong> fuentes<br />

comunes que estén sustentadas en <strong>la</strong> historia <strong>de</strong>l arte, <strong>la</strong> historia <strong>de</strong>l país y <strong>la</strong> evolución<br />

misma <strong>de</strong>l sector artístico y cultural salvadoreño. La exposición busca enfatizar esas<br />

conexiones, puntos <strong>de</strong> coinci<strong>de</strong>ncia y/o <strong>de</strong> divergencia que existen: entre algunos <strong>de</strong><br />

estos artistas, creando un espacio para hacer lecturas que permitan reevaluar y poner<br />

en perspectiva sus contribuciones.<br />

Al <strong>de</strong>sarrol<strong>la</strong>r esta propuesta, se ha tomado muy en cuenta el hecho <strong>de</strong> que, en El<br />

Salvador, el arte se ha visto esencialmente <strong>de</strong> manera cronológica, sin un nivel <strong>de</strong><br />

análisis e investigación apropiado, y quizás más académico, sobre <strong>la</strong> producción y<br />

obra <strong>de</strong> los artistas, lo que o menudo ha generado <strong>la</strong> i<strong>de</strong>a <strong>de</strong> que todas <strong>la</strong>s propuestas<br />

surgen ais<strong>la</strong>damente y sin prece<strong>de</strong>ntes. Asimismo, hay que aceptar que no ha habido<br />

un proceso <strong>de</strong> estudio y análisis sistemático <strong>de</strong> aquel<strong>la</strong>s obras a artistas que han<br />

realizado transformaciones radicales a los lenguajes artísticos a través <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong>s décadas,<br />

permitiendo que exista un sector artístico que “dice” ser incluyente (lo cual es falso)<br />

y que se resiste a reconocer el valor <strong>de</strong> algunas contribuciones, que han llevado<br />

<strong>la</strong> práctica <strong>de</strong>l arte mucho más a<strong>de</strong><strong>la</strong>nte o que simplemente han reflexionado y<br />

cuestionado sus posibilida<strong>de</strong>s.<br />

historia <strong>de</strong>l país. La propuesta también resalta <strong>la</strong>s contribuciones <strong>de</strong> algunos<br />

artistas que, a lo <strong>la</strong>rgo <strong>de</strong>l siglo, hicieron aportes <strong>de</strong> peso al <strong>de</strong>sarrollo <strong>de</strong>l<br />

arte salvadoreño, ajenos a <strong>la</strong>s ten<strong>de</strong>ncias <strong>de</strong>l mercado y cuya obra ha sido<br />

poco visible en nuestro sector artístico, con el objetivo <strong>de</strong> reposicionarlos y <strong>de</strong><br />

revalorizar sus legados.<br />

Creo importante ac<strong>la</strong>rar que durante el proceso curatorial se investiga, se recoge<br />

información y se analiza, procesándo<strong>la</strong> para <strong>de</strong>sarrol<strong>la</strong>r una tesis sobre un<br />

tema específico. Esto quiere <strong>de</strong>cir que <strong>la</strong> obra incluida en esta exposición ha<br />

sido seleccionada para apoyar <strong>la</strong>s i<strong>de</strong>as que <strong>la</strong> sustentan y propiciar un mejor<br />

entendimiento <strong>de</strong> algunas <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong>s ten<strong>de</strong>ncias que, a mi juicio, han sido dominantes<br />

en nuestro arte y <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong>s cuales han surgido muchas otras propuestas que no<br />

están incluidas en <strong>la</strong> exposición y en esta publicación.<br />

La intención es que Puntos Cardinales ofrezca al público <strong>la</strong> oportunidad <strong>de</strong><br />

apreciar obras importantes <strong>de</strong> nuestro patrimonio nacional, propiciando así un<br />

acercamiento al arte <strong>de</strong>l país, por medio <strong>de</strong> este registro (parcial aún) <strong>de</strong> nuestra<br />

historia, ten<strong>de</strong>ncias intelectuales, espirituales y estéticas.<br />

The exhibition presents four key moments in the <strong>de</strong>velopment of Salvadoran<br />

art which are reflected in the four tematically organized halls and the<br />

To c<strong>la</strong>im that all proposals have equal validity is a good way to avoid conflict,<br />

A partir <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> propuesta <strong>de</strong> esta exposición, hay cuatro momentos c<strong>la</strong>ve en el four sections of this publication. The first moment records the initial<br />

Decir que todas <strong>la</strong>s propuestas tienen igual vali<strong>de</strong>z es una buena opción para evadir however, it is not a good <strong>de</strong>cision in practice. Troughout history many forms of<br />

<strong>de</strong>sorrollo <strong>de</strong>l arte en El Salvador, los cuales están reflejados en <strong>la</strong>s cuatro sa<strong>la</strong>s <strong>de</strong>velopment of El Solvador’s artistic sector with the founding of Carlos<br />

el conflicto, pero no es una buena <strong>de</strong>cisión en <strong>la</strong> práctica. A través <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> historia se ha represantation have been established and the processes of artistic production<br />

temáticas y secciones <strong>de</strong> esta publicación. El primero marca el inicio <strong>de</strong>l <strong>de</strong>sarrollo Alberto Imery’s (1879-1949) aca<strong>de</strong>my and chronicles the first years of<br />

comprobado que <strong>la</strong>s formas <strong>de</strong> representación y los procesos <strong>de</strong> producción artística are constantly changing. Those changes occur because something new has<br />

<strong>de</strong> un sector artístico en El Salvador con <strong>la</strong> creación <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> aca<strong>de</strong>mia <strong>de</strong> Carlos Salvadoran painting. The second moment <strong>de</strong>monstrates the introduction<br />

cambian, pero que estos cambios ocurren porque se explora “algo” que no se ha been explored or presented in a different manner, which in turn modifies the<br />

Alberto Imery (1879-1949), que rubrica los primeros años <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> pintura en El of new artistic expressions that emerged in the 1930s and proposed<br />

hecho o se ha p<strong>la</strong>nteado <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> mismo manera antes, modificando en ese momento a discipline of art itself as well as the time and p<strong>la</strong>ce where it is produced. The<br />

Salvador. El segundo se sitúa en los años 30,con <strong>la</strong> introducción <strong>de</strong> lenguajes alternative forms of representation, as well as the simultaneous return to<br />

<strong>la</strong> disciplina misma (el arte), así como también el tiempo y el lugar en don<strong>de</strong> este se contributions that generate permanent changes do not allow any work of art<br />

innovadores que proponen alternativas <strong>de</strong> representación y el simultáneo retorno the aca<strong>de</strong>mic mo<strong>de</strong>l that favored the i<strong>de</strong>a of a vocation and insisted on<br />

produce. Las contribuciones que generan cambios permanentes hacen que cualquier produced in the future to be un<strong>de</strong>rstood without taking into account the change<br />

al mo<strong>de</strong>lo académico que favorece <strong>la</strong> i<strong>de</strong>a <strong>de</strong> oficio, insistiendo en los lenguajes figuration. The third moment reflects a period in the 1960s when painting<br />

obra producida posteriormente no pue<strong>de</strong> ser entendida sin tomar en cuenta el cambio that occurred earlier. This makes us accept another truth: an original creation<br />

figurativos. El tercero es un periodo <strong>de</strong> cuestionamientos a <strong>la</strong> pintura en los años is questioned and presents explorations with various types of supports and<br />

que se produjo con anterioridad, lo cual nos obliga a aceptar otra verdad que no hay cannot exist without an antece<strong>de</strong>nt.<br />

60, en el cual vemos exploraciones con diversos tipos <strong>de</strong> soportes y materiales, materials, as well as proposals that near abstraction and that move away<br />

creaciones originales sin antece<strong>de</strong>ntes.<br />

así como el surgimiento <strong>de</strong> propuestas que bor<strong>de</strong>an firmemente <strong>la</strong> abstracción from oils and cloth. Finally, the fourth moment disp<strong>la</strong>ys how the period of<br />

24 The concept of innovation and <strong>de</strong>velopment (not progress) is <strong>de</strong>monstrated<br />

y cuestionan <strong>la</strong> especificidad <strong>de</strong>l óleo y <strong>la</strong> te<strong>la</strong>. Finalmente, como cuarto war radically modified Salvadoran artists” favored subjects and caused an 25<br />

El concepto <strong>de</strong> innovación y <strong>de</strong>sarrollo (no progreso) es <strong>de</strong>mostrable e inherente en <strong>la</strong><br />

historia <strong>de</strong>l arte <strong>de</strong>l país, aunque no esté sistematizado <strong>de</strong>bido a que esta disciplina no<br />

es practicada formalmente como en otros países, a <strong>la</strong> ausencia <strong>de</strong> un mayor número<br />

<strong>de</strong> historiadores <strong>de</strong>l arte y críticos, curadores y a <strong>la</strong> carencia <strong>de</strong> expertos <strong>de</strong>dicados<br />

exclusivamente a este campo. Consecuencia <strong>de</strong> ello es nuestra casi inexistente<br />

bibliografía sobre temas artísticos y <strong>la</strong> proliferación <strong>de</strong> una serie <strong>de</strong> mitos urbanos<br />

que se han esparcido a través <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong>s galerías, <strong>la</strong> prensa y <strong>la</strong> vox populi, formando<br />

opiniones que, a menudo, no tienen un verda<strong>de</strong>ro sustento.<br />

Al tomar en cuenta lo antes mencionado, presentamos una opción <strong>de</strong> análisis y lectura <strong>de</strong><br />

<strong>la</strong> producción artística salvadoreña en el periodo establecido (pue<strong>de</strong>n surgir muchas otras<br />

lecturas), con el objetivo <strong>de</strong> intentar mostrar algunas propuestas y cambios importantes<br />

en nuestro arte que están reflejados en los acervos <strong>de</strong> estas dos colecciones públicas,<br />

así como en obras seleccionadas <strong>de</strong> colecciones privados, que <strong>de</strong> manera interesante<br />

se van re<strong>la</strong>cionando e interca<strong>la</strong>ndo con algunos momentos importantes en <strong>la</strong><br />

The profusion of such varied teaching mo<strong>de</strong>ls has also created proposal that,<br />

at first impression, appear random but in reality are based on common sources<br />

that are supported in the history of art, the history of the country, and the<br />

evolution of the artistic and cultural sector of El Salvador. The exhibition seeks to<br />

emphasize the connections, coinci<strong>de</strong>nces, and points of divergence that exist among<br />

the artists in or<strong>de</strong>r to create a dialogues that will allow viewers to re-evaluate artistic<br />

contributions and put them in perspective.<br />

This exhibition takes into account the fact that Salvadoran art has been essentially<br />

viewed chronologically, without proper analysis and investigation, and its analysis has<br />

<strong>la</strong>cked perhaps a more aca<strong>de</strong>mic approach that focuses on the artists productions.<br />

As a result, artistic proposals have often appeared as iso<strong>la</strong>ted accurrences without<br />

prece<strong>de</strong>nt in the same manner, one must accept that there has not been a systematic<br />

process of analyzing the works or artists that have ma<strong>de</strong> radical transformations<br />

to the, practice of art throughout the <strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong>s. This <strong>la</strong>ck of systematic analysis has<br />

created an artistic sector that c<strong>la</strong>ims to be all-inclusive (o c<strong>la</strong>im that is false) and that<br />

fails to acknowledge the value of contributions that have advanced the practice of art<br />

or that simply have questioned its potential.<br />

and inherent in the country’s art history, although it is not systematical due to<br />

the fact that the discipline is not formally practiced as in other countries and<br />

because of the general absence of art historians, critics, curators, and experts<br />

exclusively <strong>de</strong>dicated to this field. Consequently, Salvadoran art has a <strong>de</strong>ficient<br />

bibliography and a proliferation of urban myths that have been propagated by<br />

galleries, the press, and the vox populi, which has created opinions that often<br />

do not have verity or substance.<br />

Taking into consi<strong>de</strong>ration the aforementioned, we present this interpretation<br />

of Salvadoran art in the established period (other interpretations could be<br />

ma<strong>de</strong>) with the objective of highlighting, in these two public collections<br />

and the works on loan by private collectors, the artistic changes reflected<br />

in these paintings and the way that they are re<strong>la</strong>ted to important moments<br />

in Salvadoran history. This proposal also focuses on artists who have<br />

ma<strong>de</strong> important contributions to the <strong>de</strong>velopment of Salvadoran art—<br />

momento, el periodo <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> guerra (1979-1992), que modifica radicalmente<br />

los temas tratados por los artistas salvadoreños y que propicia el surgimiento<br />

<strong>de</strong> propuestas que tienen un alto contenido político o que exploran temas <strong>de</strong><br />

conflicto, convalecencia y muerte <strong>de</strong> manera sistemática, los cuales quisiera<br />

<strong>de</strong>sarrol<strong>la</strong>r en mayor <strong>de</strong>talle a continuación.<br />

although they produced artwork that was not associated with market<br />

ten<strong>de</strong>ncies and had little visibility in the art sector — with the objective<br />

of giving it a newfound status and re-evaluating these artists´ legacies.<br />

It is important to note that in or<strong>de</strong>r to <strong>de</strong>velop a specific thesis, one must<br />

first investigate, gather information, and then analyze and process the<br />

information. Every single painting inclu<strong>de</strong>d in this exhibition has been<br />

chosen because it supports this curatorial proposal and provi<strong>de</strong>s a clearer<br />

un<strong>de</strong>rstanding of the ten<strong>de</strong>ncies that, in my opinion, have been dominant<br />

in Salvadoran art and have resulted in other artistic investigations that are<br />

not inclu<strong>de</strong>d in this exhibition or in this publication.<br />

The intention of Cardinal Points is to present the public with the opportunity<br />

to appreciate important works of our national heritage and to promote the<br />

arts of our country through this collection, which records our history and<br />

our intellectual, spiritual, and aesthetic ten<strong>de</strong>ncies.<br />

increase in arworks that are either politically engaged or explore<br />

themes re<strong>la</strong>ted to conflict, convalescence, and <strong>de</strong>ath.

El primero <strong>de</strong> estos momentos está marcado por <strong>la</strong> partida <strong>de</strong> Imery y Ortiz<br />

Vil<strong>la</strong>corta a Europa. Las obras <strong>de</strong> los primeros años <strong>de</strong>l siglo, mostradas en<br />

<strong>la</strong> exposición, datan justamente <strong>de</strong> ese período (Campiña italiana, 1904<br />

y Campesina italiana, 1905), en que Imery ha iniciado sus estudios en<br />

Roma. En realidad, son contados los cuadros <strong>de</strong> este periodo que existen<br />

en <strong>la</strong>s colecciones públicas, lo cual está reflejado en <strong>la</strong> exposición.<br />

Significativamente, hay un cuadro <strong>de</strong> <strong>la</strong> Colección Nacional, titu<strong>la</strong>do Ruinas<br />

<strong>de</strong> Izalco (1906) <strong>de</strong> un artista poco conocido e investigado en nuestro medio,<br />