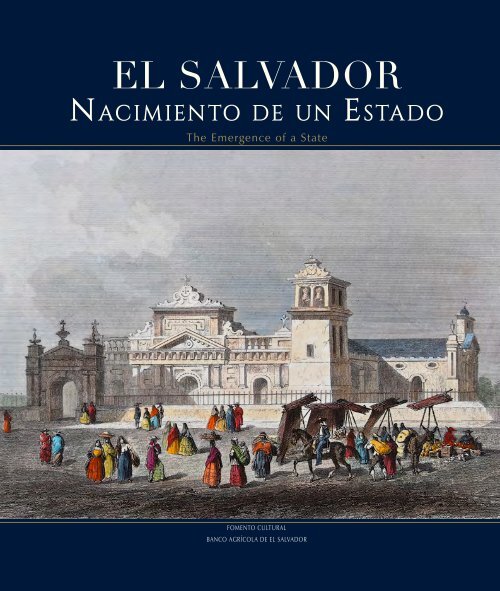

El Salvador | Nacimiento de un Estado

Descubramos nuestras raíces con el nuevo libro "Nacimiento de un Estado" de Rincón Mágico.

Descubramos nuestras raíces con el nuevo libro "Nacimiento de un Estado" de Rincón Mágico.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

EL SALVADOR<br />

<strong>Nacimiento</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>un</strong> <strong>Estado</strong><br />

The Emergence of a State<br />

FOMENTO CULTURAL<br />

BANCO AGRÍCOLA DE EL SALVADOR

EL SALVADOR<br />

<strong>Nacimiento</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>un</strong> <strong>Estado</strong><br />

The Emergence of a State<br />

Lissette <strong>de</strong> Schilling<br />

Directora Editorial • Editor in Chief<br />

José Heriberto Erquicia<br />

Investigador • Researcher<br />

2<br />

3

“Audience <strong>de</strong> Guatimala”,<br />

Nicolas Sanson, París, 1693.<br />

4<br />

5

Reconocimientos<br />

AKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

Rafael Barraza<br />

Presi<strong>de</strong>nte Ejecutivo • Executive Presi<strong>de</strong>nt<br />

Lissette <strong>de</strong> Schilling<br />

Directora editorial • Editor in Chief<br />

Banco Agrícola agra<strong>de</strong>ce al Museo <strong>de</strong> Antropología <strong>de</strong><br />

<strong>El</strong> <strong>Salvador</strong> “David J. Guzmán”, a Pedro Escalante Arce,<br />

Leonel Barrillas, Jorge Orellana, Carlos A. Quintanilla Molina,<br />

Nick Mahomar, Juan Fernando Villafuerte e Iván Zelaya, sin<br />

cuya colaboración no hubiera sido posible este proyecto.<br />

José Heriberto Erquicia<br />

Pedro Escalante Arce<br />

Investigadores • Researchers<br />

Nelson Crisóstomo<br />

Fotógrafo • Photographer<br />

Alex Castillo<br />

Asistente <strong>de</strong> fotografía<br />

Photography assistant<br />

Constance Schilling<br />

Correctora <strong>de</strong> estilo y traductora<br />

Editor and Translator<br />

Creãre<br />

Diseño gráfico • Graphic <strong>de</strong>sign<br />

Lissette <strong>de</strong> Schilling<br />

Dirección <strong>de</strong> producción digital y proceso <strong>de</strong> impresión<br />

Digital production and printing process direction<br />

Artes Gráficas Publicitarias S. A. <strong>de</strong> C. V.<br />

Impresión • Printing<br />

Librería y Papeleria La Ibérica S. A. <strong>de</strong> C. V.<br />

Empastado • Binding<br />

© 2020. Banco Agrícola. Derechos reservados.<br />

Queda prohibida, como lo establece la ley, la reproducción parcial o total <strong>de</strong><br />

este libro sin previo permiso por escrito <strong>de</strong> Banco Agrícola, con excepción<br />

<strong>de</strong> breves fragmentos que pue<strong>de</strong>n usarse en reseñas en los distintos medios<br />

<strong>de</strong> com<strong>un</strong>icación, siempre que se cite la fuente.<br />

Retablo <strong>de</strong> la iglesia Santiago Apóstol,<br />

Chalchuapa, Santa Ana.<br />

6<br />

7

Pintura <strong>de</strong>l “Primer Grito <strong>de</strong><br />

In<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>ncia <strong>de</strong> 1811”.<br />

En primer plano el padre José Matías<br />

Delgado y en la parte superior <strong>de</strong>recha<br />

<strong>de</strong>l cuadro, los hermanos Manuel,<br />

Vicente y Nicolás Aguilar y Bustamante,<br />

acompañados <strong>de</strong> diferentes sectores <strong>de</strong> la<br />

sociedad <strong>de</strong> la época.<br />

Luis Vergara Ahumada, 1958.<br />

8<br />

9

Contenido<br />

CONTENTS<br />

Presentación<br />

FOREWORD<br />

13<br />

Introducción<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

21<br />

Quimeras <strong>de</strong> autonomía<br />

VISIONS OF SOVEREIGNTY<br />

32<br />

<strong>El</strong> camino a la emancipación<br />

<strong>de</strong> Centroamérica<br />

THE PATH TO THE EMANCIPATION OF<br />

CENTRAL AMERICA<br />

60<br />

Levantamiento popular<br />

en San Pedro Metapán, 1811<br />

POPULAR UPRISING<br />

IN SAN PEDRO METAPÁN, 1811<br />

80<br />

América Central: in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>ncia,<br />

anexión a México y disolución<br />

<strong>de</strong>l Proyecto <strong>de</strong> Iturbi<strong>de</strong>, 1821-1823<br />

CENTRAL AMERICA: INDEPENDENCE,<br />

ANNEXATION TO MÉXICO AND DISSOLUTION<br />

OF THE ITURBIDE PROJECT, 1821-1823<br />

100<br />

Grabado <strong>de</strong> la catedral <strong>de</strong> San Miguel. “Harper´s Weekly”, 1891, Nueva York,<br />

sección “The Illustrated News of the World”.<br />

Creación <strong>de</strong>l <strong>Estado</strong> <strong>de</strong>l <strong>Salvador</strong>,<br />

constituciones y Abolición<br />

<strong>de</strong> la esclavitud en la<br />

América Central, 1824<br />

CREATION OF THE STATE OF SALVADOR,<br />

CONSTITUTIONS AND ABOLITION OF<br />

SLAVERY IN CENTRAL AMERICA, 1824<br />

128

Mapa <strong>de</strong>l curato <strong>de</strong> San Juan Oscicala, 1782.<br />

Al centro el poblado <strong>de</strong> Oscicala, a<strong>de</strong>más <strong>de</strong> los<br />

poblados circ<strong>un</strong>dantes Cacaopera, Yoloaiquín,<br />

Gualococti, Sencimón, Sesore, Cacaguatique, al<br />

noroeste el río Lempa, al sur el gran río Torola.<br />

Archivo Histórico Archiocesano <strong>de</strong> Guatemala.<br />

12<br />

13

Presentación<br />

Banco Agrícola, a través <strong>de</strong> su programa <strong>de</strong> Fomento Cultural, presenta<br />

esta nueva edición, que relata las diversas aristas que indujeron a los<br />

procesos <strong>de</strong> formación <strong>de</strong>l naciente <strong>Estado</strong> salvadoreño <strong>de</strong> inicios <strong>de</strong>l<br />

siglo XIX, y que en su momento tuvieron como p<strong>un</strong>to <strong>de</strong> partida los sucesos<br />

globales que motivaron a las colonias americanas a emanciparse <strong>de</strong> España, en <strong>un</strong><br />

proceso que sin duda también tuvo muchas motivaciones e incitaciones <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> el<br />

interior <strong>de</strong> los propios territorios americanos.<br />

<strong>El</strong> <strong>Salvador</strong>: <strong>Nacimiento</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>un</strong> <strong>Estado</strong>, también reconoce el ímpetu <strong>de</strong> hombres y<br />

mujeres, que entre indígenas, mulatos, mestizos, ladinos y criollos, y sobre la base <strong>de</strong><br />

<strong>un</strong>a diversidad <strong>de</strong> luchas, pretendían <strong>un</strong> mejor clima social, político y económico para<br />

los habitantes <strong>de</strong> los territorios <strong>de</strong> la América Central.<br />

San <strong>Salvador</strong> tomó la <strong>de</strong>lantera en la región al vislumbrarse como autónoma,<br />

irrumpiendo así en los motines <strong>de</strong>l 5 <strong>de</strong> noviembre <strong>de</strong> 1811, que luego suce<strong>de</strong>rían en<br />

otros espacios como Metapán y en varias localida<strong>de</strong>s <strong>de</strong>l territorio centroamericano.<br />

Este fue el inicio <strong>de</strong> <strong>un</strong>a multiplicidad <strong>de</strong> hechos que se fueron dando a lo largo y<br />

ancho <strong>de</strong> la región y <strong>de</strong>l continente americano; este largo proceso culminaría, para<br />

la América Central, con la firma <strong>de</strong>l Acta <strong>de</strong> In<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>ncia <strong>de</strong> Centroamérica en<br />

septiembre <strong>de</strong> 1821.<br />

Este hecho condujo a <strong>un</strong>a serie <strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>safíos, disputas y quimeras que acarrearon<br />

a las provincias <strong>de</strong>l centro <strong>de</strong> América a anexarse al Imperio mexicano; pero tras la<br />

caída <strong>de</strong> ese fugaz po<strong>de</strong>río, se procedió a la conformación <strong>de</strong> la República Fe<strong>de</strong>ral <strong>de</strong><br />

Centroamérica, no sin antes pactar la <strong>un</strong>ión <strong>de</strong> San <strong>Salvador</strong> y Sonsonate, y con ello<br />

dar paso a la creación <strong>de</strong>l <strong>Estado</strong> <strong>de</strong>l <strong>Salvador</strong> en 1824.<br />

Banco Agrícola, en el marco <strong>de</strong> la conmemoración <strong>de</strong> los movimientos<br />

in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>ntistas y el surgimiento <strong>de</strong> nuestra nación, reitera su compromiso con<br />

el fomento <strong>de</strong> la cultura al rescatar, documentar y divulgar nuestra historia, porque<br />

conociendo nuestro pasado actuaremos con claridad en el presente y en el futuro.<br />

Rafael Barraza<br />

Presi<strong>de</strong>nte Ejecutivo<br />

Joven india <strong>de</strong> Santa Ana, Publicado en<br />

“De París a Guatemala”, <strong>de</strong> J. Laferrière. París, Francia, 1877.<br />

14<br />

15

Grabado <strong>de</strong> la Catedral <strong>de</strong> San <strong>Salvador</strong>.<br />

L’Illustration, J<strong>un</strong>io <strong>de</strong> 1873.<br />

16<br />

17

Foreword<br />

Banco Agrícola, through its Cultural Development program, presents this<br />

new edition, which reco<strong>un</strong>ts the various aspects that led to the formation<br />

of the nascent <strong>Salvador</strong>an State in the early nineteenth century, which<br />

in turn had as its starting point the global events that motivated the American<br />

colonies to emancipate from Spain, in a process that <strong>un</strong>doubtedly also had many<br />

motivations and incitements from within the American territories themselves.<br />

<strong>El</strong> <strong>Salvador</strong>: Emergence of a State, also recognizes the impetus of men and women,<br />

indigenous, mulatto, mestizo, ladino and creole, who on the basis of a diversity of<br />

struggles, sought a better social, political and economic climate for the inhabitants of<br />

the territories of Central America.<br />

San <strong>Salvador</strong> took the lead in the region when it saw itself as autonomous, thus<br />

bursting into the riots of November 5, 1811, which would later occur in other spaces,<br />

such as Metapán, and in several locations in Central American territory. This was the<br />

beginning of a multiplicity of events that took place throughout the region and the<br />

American continent; this long process would culminate, for Central America, with the<br />

signing of the Central American In<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nce Act in September 1821.<br />

This event led to a series of challenges, disputes and chimeras that caused the<br />

provinces of Central America to be annexed to the Mexican Empire; but after the<br />

fall of that fleeting power, the Fe<strong>de</strong>ral Republic of Central America was formed, not<br />

without first agreeing to the <strong>un</strong>ion of San <strong>Salvador</strong> and Sonsonate, and thus giving<br />

way to the establishment of the State of <strong>Salvador</strong> in 1824.<br />

Banco Agrícola, within the framework of the commemoration of the in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nce<br />

movements and the emergence of our nation, reiterates its commitment to the<br />

promotion of culture by rescuing, documenting and disseminating our history,<br />

because by knowing our past we will act clearly in the present and in the future.<br />

Rafael Barraza<br />

Executive Presi<strong>de</strong>nt<br />

Detalle <strong>de</strong> retablo <strong>de</strong> la iglesia Santiago Apóstol,<br />

Chalchuapa, Santa Ana.<br />

18<br />

19

Viaducto <strong>de</strong> San <strong>Salvador</strong>, Frank Leslie,<br />

Ilustratred Newspaper, Nueva York, 1873,<br />

20<br />

21

Introducción<br />

“Tus <strong>de</strong>rechos son los míos, los <strong>de</strong> mis amigos y mis<br />

paisanos. Yo juro sostenerlos mientras viva… Recibe,<br />

Patria amada, este juramento… La América será <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong><br />

hoy mi ocupación exclusiva. América <strong>de</strong> día cuando<br />

escriba; América <strong>de</strong> noche cuando piense. <strong>El</strong> estudio<br />

más digno <strong>de</strong> <strong>un</strong> americano es la América.” 1<br />

José Cecilio <strong>de</strong>l Valle.<br />

Altar Mayor <strong>de</strong> la iglesia<br />

<strong>de</strong> San Miguel Arcángel, Huizúcar, La Libertad.<br />

Esta obra ofrece dilucidar al lector el contexto histórico que envolvió <strong>un</strong>a diversidad <strong>de</strong><br />

hechos suscitados en la América Central entre 1811 y 1824, sin obviar los ocurridos en otros<br />

p<strong>un</strong>tos <strong>de</strong> la América Hispana; y por supuesto los acontecimientos que se <strong>de</strong>sarrollaron<br />

en Europa y que conllevaron al nacimiento <strong>de</strong> las nuevas naciones americanas. Y es que las<br />

revoluciones, los movimientos insurgentes y las <strong>de</strong>más acciones <strong>de</strong> emancipación americanas en<br />

la lucha por su in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>ncia, certificaron y legitimaron el precepto <strong>de</strong> auto<strong>de</strong>terminación <strong>de</strong> los<br />

pueblos como principio valido <strong>de</strong> las nuevas soberanías. Con ello, también perturbaron el balance<br />

<strong>de</strong>l po<strong>de</strong>r global <strong>de</strong> su época.<br />

La estabilidad financiera que había caracterizado a la Corona española durante la mayor parte<br />

<strong>de</strong>l siglo XVIII se agrietó a partir <strong>de</strong> 1779, cuando España entró en <strong>un</strong>a retahíla <strong>de</strong> guerras con<br />

Inglaterra y Francia, en las cuales las naciones compitieron por el predominio en Europa. <strong>El</strong> sustento<br />

<strong>de</strong> la milicia y las consecuencias <strong>de</strong> las guerras, tales como epi<strong>de</strong>mias y hambr<strong>un</strong>as, aumentaron<br />

principalmente el gasto público y llevaron el presupuesto <strong>de</strong>l ejército a <strong>un</strong> déficit. 2<br />

Es por ello que, durante el siglo XVIII, España, Portugal, Francia y Gran Bretaña se propusieron<br />

conseguir más recursos <strong>de</strong> sus dominios americanos, <strong>de</strong>bido al nivel <strong>de</strong> conflictos militares <strong>de</strong><br />

los que fueron protagonistas. Para solventar esos gastos <strong>de</strong> guerra, introdujeron reformas con el<br />

objetivo <strong>de</strong> que la recaudación fiscal fuera eficiente y por en<strong>de</strong> mayor. A<strong>un</strong>que España y Portugal<br />

tuvieron más éxito en las reformas <strong>de</strong> los dominios americanos, incrementando las riquezas<br />

generadas por el comercio <strong>de</strong> bienes y la exportación <strong>de</strong> recursos naturales, este escenario no<br />

duró mucho tiempo, pues para 1790 la marina <strong>de</strong> guerra española ya había quebrado. Acto seguido<br />

los conflictos entre la Francia napoleónica e Inglaterra terminaron involucrando a las monarquías<br />

ibéricas que, en los inicios <strong>de</strong>l siglo XIX, se encontraban en bancarrota. 3<br />

En España, Carlos IV había establecido <strong>un</strong>a incómoda alianza con Napoleón Bonaparte. Esto<br />

y <strong>un</strong>a serie <strong>de</strong> subsecuentes eventos que ocurrieron en la península abrieron <strong>un</strong>a ventana para<br />

que los americanos pensaran que era la oport<strong>un</strong>idad <strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>sligarse <strong>de</strong> la Corona hispana. Las i<strong>de</strong>as<br />

y las prácticas políticas <strong>de</strong>sarrolladas durante varios siglos entraron en tensión y conflicto con<br />

los planteamientos <strong>de</strong>l liberalismo. La primera <strong>de</strong> las convulsiones se había originado cuando se<br />

trastocaron las leyes f<strong>un</strong>damentales <strong>de</strong> la Monarquía española. 4<br />

Lo anterior es el reflejo <strong>de</strong> lo que estaba ocurriendo en el contexto transatlántico-global, por<br />

supuesto en las colonias americanas estaba repercutiendo esta situación <strong>de</strong> forma colateral y<br />

directa. En toda América, las Reformas Borbónicas, los conflictos por el po<strong>de</strong>r en los cabildos,<br />

y p<strong>un</strong>tualmente en la América Central la situación económica y los conflictos políticos, étnicos<br />

y sociales, llevaron a pensar que era necesario <strong>un</strong> cambio; no sin antes pasar por <strong>un</strong>a serie <strong>de</strong><br />

transformaciones que provenían <strong>de</strong>l mismo i<strong>de</strong>ario constitucionalista y liberal.<br />

22<br />

23

En la historiografía iberoamericana, las in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>ncias fueron tratadas <strong>de</strong> diversas formas<br />

durante el siglo XX; esto obe<strong>de</strong>cía a las distintas corrientes <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> don<strong>de</strong> se escribía sobre dichas<br />

temáticas. En el <strong>de</strong>cenio <strong>de</strong> 1950, la versión hegemónica respecto a las interpretaciones <strong>de</strong> las<br />

in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>ncias fue a través <strong>de</strong> la <strong>de</strong>nominada Historia Patria o Historia <strong>de</strong> Bronce, en don<strong>de</strong> el<br />

actor principal era el Héroe, ya fuera libertador o caudillo, y se trataba <strong>de</strong> <strong>un</strong>a figura que se reducía<br />

a <strong>un</strong>as características com<strong>un</strong>es, tales como varón, militar, entre treinta y cincuenta años y <strong>un</strong><br />

auténtico “héroe” con las cualida<strong>de</strong>s <strong>de</strong> brío, monta, disciplina y, sobre todo, valentía <strong>de</strong> llevar a<br />

“su pueblo” hacia la tan ansiada libertad frente al yugo y vasallaje “español”. A partir <strong>de</strong> la década<br />

<strong>de</strong> 1970 en la historiografía, este héroe-actor hegemónico fue superado por otros protagonistas en<br />

la historia, haciendo <strong>de</strong> ello <strong>un</strong> cambio significativo en los nuevos planteamientos, interpretaciones<br />

y análisis. A<strong>un</strong>que esta corriente fue extensiva a toda Hispanoamérica, se <strong>de</strong>senvolvió a ritmos<br />

diferentes. Se produjo <strong>un</strong> cambio <strong>de</strong> ciclo con miradas diversas e interpretaciones variadas; con ello<br />

se incorporaron análisis y perspectivas <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> la Historia Social. A partir <strong>de</strong> acá, el sujeto “social”, el<br />

<strong>de</strong> los movimientos y grupos sociales, cobró importancia y f<strong>un</strong>damentalmente <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> la perspectiva<br />

étnica, tan prepon<strong>de</strong>rante para las socieda<strong>de</strong>s <strong>de</strong> América Latina. No menos importantes fueron los<br />

análisis <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> el enfoque <strong>de</strong> los estudios <strong>de</strong> género. A<strong>de</strong>más se incorporaron otros temas <strong>de</strong> estudio,<br />

como el advenimiento <strong>de</strong> la ciudadanía, los estudios <strong>de</strong> las elecciones, <strong>de</strong> las constituciones, <strong>de</strong>l<br />

liberalismo gaditano y su importancia en Iberoamérica. 5 Con ellos se dio a las in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>ncias otra<br />

valoración más cívica y menos armada.<br />

Este libro está dividido en cuatro capítulos, los cuales, como se expuso al inicio, procuran<br />

llevar <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> el final <strong>de</strong>l período colonial <strong>de</strong> la Corona Española, pasando por los movimientos <strong>de</strong><br />

insurrección, hasta llegar a la in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>ncia <strong>de</strong> Centroamérica y la posterior creación <strong>de</strong>l <strong>Estado</strong><br />

<strong>de</strong>l <strong>Salvador</strong>. Quimeras <strong>de</strong> autonomía presenta todo el contexto m<strong>un</strong>dial y regional <strong>de</strong> la situación<br />

política, económica y social que se estaba dando <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> el último cuarto <strong>de</strong>l siglo XVIII hasta los<br />

albores <strong>de</strong>l siglo XIX. <strong>El</strong> camino a la emancipación <strong>de</strong> Centroamérica es el recorrido que hacen las<br />

provincias rebel<strong>de</strong>s <strong>de</strong> la América Central en su afán por <strong>de</strong>sligarse <strong>de</strong> la capital, Guatemala, en los<br />

sucesos <strong>de</strong> 1811 y 1814. Conj<strong>un</strong>tamente, <strong>de</strong>ntro <strong>de</strong> este capítulo, yace la contribución <strong>de</strong> Don Pedro<br />

Escalante Arce, con los sucesos acaecidos en San Pedro Metapán en noviembre <strong>de</strong> 1811, que para<br />

alg<strong>un</strong>os son eventos <strong>de</strong>sconocidos.<br />

<strong>El</strong> capítulo tercero se <strong>de</strong>nomina América Central: In<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>ncia, Anexión a México y Disolución<br />

<strong>de</strong>l Proyecto <strong>de</strong> Iturbi<strong>de</strong> (1821-1823). Este se subdivi<strong>de</strong> en dos apartados: La firma <strong>de</strong>l Acta <strong>de</strong>l<br />

15 <strong>de</strong>septiembre <strong>de</strong> 1821, y La anexión a México y el proyecto <strong>de</strong> Agustín <strong>de</strong> Iturbi<strong>de</strong>. En ellos<br />

se relatan los diversos procesos políticos que llevaron a la in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>ncia <strong>de</strong> Centroamérica, la<br />

posterior anexión a México, las batallas suscitadas en el ínterin y su abrupto <strong>de</strong>senlace con la caída<br />

<strong>de</strong>l Imperio Mexicano <strong>de</strong> Agustín <strong>de</strong> Iturbi<strong>de</strong>. <strong>El</strong> cuarto y último capítulo se <strong>de</strong>nomina Creación<br />

<strong>de</strong>l <strong>Estado</strong> <strong>de</strong>l <strong>Salvador</strong>, constituciones y abolición <strong>de</strong> la esclavitud en la América Central, 1824.<br />

En él se relata la conformación <strong>de</strong>l <strong>Estado</strong> <strong>de</strong>l <strong>Salvador</strong> a partir <strong>de</strong> la <strong>un</strong>ión <strong>de</strong> dos regiones que<br />

siempre estuvieron vinculadas, San <strong>Salvador</strong> y Sonsonate, para dar paso a <strong>un</strong> nuevo <strong>Estado</strong>; luego<br />

la construcción <strong>de</strong> la República Fe<strong>de</strong>ral <strong>de</strong> Centroamérica y su Constitución política; para concluir<br />

con la Constitución <strong>de</strong>l <strong>Estado</strong> <strong>de</strong>l <strong>Salvador</strong> y los principios <strong>de</strong> igualdad, libertad y justicia, con la<br />

abolición <strong>de</strong> la esclavitud en Centroamérica, <strong>de</strong> acuerdo a la Constitución Fe<strong>de</strong>ral <strong>de</strong> 1824.<br />

Este relato histórico ha tratado <strong>de</strong> echar <strong>un</strong> vistazo a los acontecimientos políticos, económicos,<br />

sociales y étnicos, que llevaron a la in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>ncia <strong>de</strong> Centroamérica, la creación <strong>de</strong>l <strong>Estado</strong> <strong>de</strong>l<br />

<strong>Salvador</strong> y la elaboración <strong>de</strong> sus respectivas Constituciones políticas, <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> <strong>un</strong>a mirada, como<br />

expresa Chust 6 , con apreciaciones más amplias, más enriquecedoras, menos nacionalistas y más<br />

internacionales, y significativamente interrelacionadas para ofrecer <strong>un</strong> alcance menos estrecho y<br />

más riguroso a este proceso insurgente <strong>de</strong> las in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>ncias <strong>de</strong> la América.<br />

Nova et Accurata Totius Americal Tabula, 1740. Difusión <strong>de</strong><br />

colecciones digitales <strong>de</strong> Biblioteca Virtual <strong>de</strong>l M. <strong>de</strong> Defensa, España.<br />

24<br />

25

Grabado <strong>de</strong>l Palacio M<strong>un</strong>icipal <strong>de</strong> Guatemala.<br />

Geografía <strong>de</strong> Centro América. París. José María Cáceres, 1882.<br />

26<br />

27

Introduction<br />

“Your rights are my rights, those of my friends and<br />

my co<strong>un</strong>trymen. I swear to uphold them as long as<br />

I shall live... Receive, my beloved co<strong>un</strong>try, this oath...<br />

America will be from today onwards my exclusive<br />

occupation. America by day when I write; America<br />

by night when I think. The most worthy study of an<br />

American is America” 1<br />

José Cecilio <strong>de</strong>l Valle.<br />

E<br />

This work offers the rea<strong>de</strong>r an insight into the historical context that involved a diversity<br />

of events that took place in Central America between 1811 and 1824, without ignoring<br />

those that occurred in other parts of Hispanic America; and of course the events that<br />

took place in Europe and led to the birth of the new American nations. The revolutions, the<br />

insurgent movements and the other actions of emancipation of the Americans in the fight for<br />

their in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nce, certified and legitimized the precept of self-<strong>de</strong>termination of the peoples as<br />

a valid principle of the new sovereignties. In doing so, they also disturbed the balance of global<br />

power of their time.<br />

The financial stability that had characterized the Spanish Crown for most of the eighteenth<br />

century cracked after 1779, when Spain entered a string of wars with England and France, in<br />

which these nations competed for dominance in Europe. The support of the militia and the<br />

consequences of the wars, such as epi<strong>de</strong>mics and famines, mainly increased public spending<br />

and drove the army budget into <strong>de</strong>ficit. 2<br />

That is why, during the eighteenth century, Spain, Portugal, France and Great Britain set<br />

out to get more resources from their American domains, due to the level of military conflicts<br />

in which they were involved. To solve these war expenses, they introduced reforms with the<br />

aim of making tax collection efficient and therefore greater. Although Spain and Portugal were<br />

more successful in the reforms of the American domains, increasing the wealth generated by<br />

the tra<strong>de</strong> of goods and the export of natural resources, this scenario did not last long, because<br />

by 1790 the Spanish Navy had already gone bankrupt. Then the conflicts between Napoleonic<br />

France and England en<strong>de</strong>d up involving the Iberian monarchies which, at the beginning of the<br />

nineteenth century, were in bankruptcy. 3<br />

In Spain, Charles IV had established an <strong>un</strong>easy alliance with Napoleon Bonaparte. This<br />

and a series of subsequent events that occurred on the peninsula gave Americans a window<br />

of opport<strong>un</strong>ity to disassociate themselves from the Hispanic Crown. The i<strong>de</strong>as and political<br />

practices <strong>de</strong>veloped over several centuries came into tension and conflict with the approaches<br />

of liberalism. The first of the upheavals originated when the f<strong>un</strong>damental laws of the Spanish<br />

Monarchy were modified. 4<br />

The above-mentioned is a reflection of what was happening in the transatlantic-global<br />

context, of course this situation was having a direct, collateral effect on the American colonies.<br />

In all America, the Bourbon Reforms, the power struggles in the town halls, and p<strong>un</strong>ctually<br />

in Central America the economic situation and the political, ethnic and social conflicts, led to<br />

think that change was necessary; not before passing through a series of transformations that<br />

came from the same constitutionalist and liberal i<strong>de</strong>ology.<br />

Virgen <strong>de</strong>l Apocalipsis. México, siglo XVIII<br />

28<br />

29

In Ibero-American historiography, in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nce was treated in various ways during<br />

the twentieth century; this was due to the different currents from which these subjects<br />

were written. In the 1950s, the hegemonic version regarding the interpretations of the<br />

in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nces was through the so called Homeland History (Historia Patria) or Bronze History<br />

(Historia <strong>de</strong> Bronce), in which the main actor was the Hero, either a liberator or a caudillo,<br />

and it consisted of a figure that was reduced to some common characteristics, such as male,<br />

military, between thirty and fifty years old and an authentic “hero” with the attributes of<br />

vigor, discipline and, above all, courage to lead “his people” towards the so longed for freedom<br />

from the “Spanish” domination and vassalage. From the 1970s onwards in historiography, this<br />

hegemonic hero was surpassed by other protagonists in history, making a significant change<br />

in the new approaches, interpretations and analyses. Although this trend spread throughout<br />

Hispanic America, it <strong>de</strong>veloped at different rates. A change of cycle was produced with diverse<br />

viewpoints and varied interpretations; with this, analyses and perspectives from Social History<br />

were incorporated. From here on, the “social” subject, that of social movements and groups,<br />

became important and f<strong>un</strong>damentally from the ethnic perspective, so prepon<strong>de</strong>rant for Latin<br />

American societies. The analyses from the gen<strong>de</strong>r studies approach were of no less importance.<br />

Furthermore, other study topics were incorporated, such as the advent of citizenship, studies<br />

of elections, constitutions, Cadiz liberalism and its importance in Ibero-America. 5 These<br />

studies gave in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nces a more civic and less armed value.<br />

This book is divi<strong>de</strong>d into four chapters, which, as explained at the beginning, take the<br />

rea<strong>de</strong>r from the end of the colonial period of the Spanish Crown, through the insurrection<br />

movements, to the in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nce of Central America and the subsequent creation of the<br />

State of <strong>Salvador</strong>. Visions of Sovereignty presents the entire global and regional context<br />

of the political, economic and social situation that was taking place from the last quarter<br />

of the eighteenth century <strong>un</strong>til the beginning of the nineteenth century. The Path to the<br />

Emancipation of Central America is the route taken by the rebellious provinces of Central<br />

America in their efforts to break away from the capital, Guatemala, in the events of 1811 and<br />

1814. Together, within this chapter, lies the contribution of Don Pedro Escalante Arce, with the<br />

events that occurred in San Pedro Metapán in November 1811, which for some are <strong>un</strong>known<br />

events. The third chapter is called Central America: In<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nce, Annexation to Mexico and<br />

Dissolution of the Iturbi<strong>de</strong> Project, 1821-1823. It is divi<strong>de</strong>d into two sections: The Signing of<br />

the Act of September 15, 1821, and The Annexation to Mexico and the Project of Agustín <strong>de</strong><br />

Iturbi<strong>de</strong>. They narrate the various political processes that led to the in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nce of Central<br />

America, the subsequent annexation to Mexico, the battles that took place in the interim and<br />

their abrupt end with the fall of Agustin <strong>de</strong> Iturbi<strong>de</strong>’s Mexican Empire. The fourth and final<br />

chapter is called Creation of the State of <strong>Salvador</strong>, Constitutions and Abolition of Slavery in<br />

Central America, 1824. It <strong>de</strong>scribes the formation of the State of <strong>Salvador</strong> from the <strong>un</strong>ion of<br />

two regions that were always linked, San <strong>Salvador</strong> and Sonsonate, to give way to a new State;<br />

then the construction of the Fe<strong>de</strong>ral Republic of Central America and its political Constitution;<br />

to conclu<strong>de</strong> with the Constitution of the State of <strong>Salvador</strong> and the principles of equality,<br />

freedom and justice, with the abolition of slavery in Central America, according to the Fe<strong>de</strong>ral<br />

Constitution of 1824.<br />

This historical acco<strong>un</strong>t has tried to take a look at the political, economic, social and ethnic<br />

events, which led to the in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nce of Central America, the creation of the State of <strong>Salvador</strong><br />

and the elaboration of their respective political Constitutions, from a viewpoint, as expressed<br />

by Chust 6 , with broa<strong>de</strong>r, more enriching, less nationalistic and more international appreciations,<br />

and significantly interrelated to offer a less narrow and more rigorous scope to this insurgent<br />

process of the in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nces of America.<br />

Grabado <strong>de</strong> re<strong>un</strong>ión <strong>de</strong> alcal<strong>de</strong>s.<br />

“De París a Guatemala”, <strong>de</strong> J. Laferrière. París, Francia, 1877.<br />

30<br />

31

Mapa <strong>de</strong> las Provincias <strong>de</strong> Tabasco, Chiapa,<br />

Verapaz, Guatemala, Honduras y Yucatán.<br />

“Historire Générale <strong>de</strong>s Voyages”, L´Abbé<br />

Antoine François Prévost. grabado por<br />

Jacques Nicolas Bellin. París 1747.<br />

32<br />

33

Catedral <strong>de</strong> San <strong>Salvador</strong>.<br />

L’Amerique Centrale et Meridionale,<br />

Louis Enault, Paris, 1867.<br />

Quimeras <strong>de</strong> autonomía<br />

Visions of Sovereignty<br />

Hacia el último cuarto <strong>de</strong>l siglo XVIII, el pensamiento <strong>de</strong>l m<strong>un</strong>do occi<strong>de</strong>ntal estaba revolucionándose.<br />

<strong>El</strong> i<strong>de</strong>ario <strong>de</strong> las liberta<strong>de</strong>s estaba calando muy hondo en la sociedad <strong>de</strong> la América española.<br />

La Centroamérica española era el Reino <strong>de</strong> Guatemala, término que profería la clara noción <strong>de</strong><br />

disociación <strong>de</strong> sus habitantes con relación <strong>de</strong>l Virreinato <strong>de</strong> la Nueva España, al que formalmente pertenecía. A la luz<br />

<strong>de</strong> ello, la Audiencia <strong>de</strong> Guatemala formaba parte <strong>de</strong>l virreinato novohispano, pero como Audiencia Mayor, teniendo<br />

<strong>un</strong> presi<strong>de</strong>nte-gobernador a la cabeza <strong>de</strong>l gobierno; así no cabe duda que gozaba <strong>de</strong> <strong>un</strong>a virtual in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>ncia<br />

respecto <strong>de</strong>l virrey mexicano. 7 <strong>El</strong> espacio político administrativo <strong>de</strong>l Reino <strong>de</strong> Guatemala, durante los siglos XVII y<br />

XVIII, estaba organizado <strong>de</strong> tal forma, que cada provincia en su interior estaba conformada por corregimientos o<br />

alcaldías mayores; pero cabe resaltar que <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> la división antigua, como <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> la creación <strong>de</strong> las Inten<strong>de</strong>ncias, los<br />

espacios se reorganizaron en base a la división eclesiástica, es <strong>de</strong>cir, <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> el Curato.<br />

By the last quarter of the eighteenth century, the new currents of thought in the Western world were being<br />

revolutionized. The i<strong>de</strong>a of freedom was taking shape in Spanish American society.<br />

Spanish Central America constituted the Kingdom of Guatemala, a term that proffered the clear<br />

notion of dissociation of its inhabitants from the Viceroyalty of New Spain, to which it formally belonged. The<br />

Audiencia of Guatemala was part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, but as the Audiencia Mayor, with a presi<strong>de</strong>ntgovernor<br />

at the head of the government; it thus enjoyed virtual autonomy from the Mexican Viceroy. 7 The politicaladministrative<br />

structure of the Kingdom of Guatemala, during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, was<br />

organized in such a way that each of its provinces was ma<strong>de</strong> up of townships or mayoralties; but it should be<br />

noted that since the old division, as well as since the creation of the Inten<strong>de</strong>ncies, the structures were reorganized<br />

on the basis of the ecclesiastical division, that is, from the Curato.<br />

34<br />

35

<strong>El</strong> Curato es el cargo <strong>de</strong> <strong>un</strong> cura, es <strong>un</strong> sinónimo <strong>de</strong><br />

parroquia; a<strong>de</strong>más compren<strong>de</strong> el territorio sobre el cual ejerce<br />

jurisdicción espiritual y <strong>de</strong>l cual obtiene beneficios, ya sea <strong>de</strong><br />

rentas, tributos u otras merce<strong>de</strong>s. Este se hallaba constituido<br />

por <strong>un</strong>a serie <strong>de</strong> asentamientos indígenas o mestizos, en<br />

don<strong>de</strong> la cabecera era el poblado principal; en él residía el<br />

cura o párroco, las poblaciones pequeñas eran consi<strong>de</strong>radas<br />

agregadas a la cabecera. 8<br />

M a pa <strong>de</strong>l Curato <strong>de</strong> San Salva d o r<br />

The Curato is the office of a priest, it is synonymous with<br />

a parish; in this case it comprises the territory over which<br />

he exercises spiritual jurisdiction and from which he <strong>de</strong>rives<br />

benefits, whether from rents, taxes or other grants. It was<br />

constituted by a series of indigenous or mestizo settlements,<br />

the priest or pastor resi<strong>de</strong>d in it’s main town, small villages<br />

were consi<strong>de</strong>red as aggregates to the main town. 8<br />

Territorios comprendidos en el<br />

curato <strong>de</strong> San <strong>Salvador</strong>:<br />

1- Ciudad <strong>de</strong> San <strong>Salvador</strong> (Cabecera)<br />

2- Pueblo <strong>de</strong> Cuscatancingo<br />

3- Pueblo <strong>de</strong> Paleca<br />

4- Pueblo <strong>de</strong> Apopa<br />

5- Pueblo <strong>de</strong> Nexapa<br />

6- Pueblo <strong>de</strong> Quesaltepeque<br />

7- Pueblo <strong>de</strong> Guazapa<br />

Haciendas:<br />

8- <strong>El</strong> Paxnal<br />

9- <strong>El</strong> Ángel<br />

10- San Nicolás<br />

11- Santa Bárbara<br />

12- San Jph. Lorenzana<br />

13- Santa Bárbara<br />

14- Milapa<br />

15- Los Inocentes<br />

16- Atapasco<br />

17- Tacaoluco<br />

18- 3 a . <strong>de</strong> Santa Bárbara<br />

19- Jutultepeque<br />

20- Santa Inés<br />

21- San Jph. Fernan<strong>de</strong>s<br />

22- San Gerónimo<br />

23- San Christóval<br />

24- San Lucas<br />

25- La Cavaña<br />

26- <strong>El</strong> Rancho<br />

27- La Consolación<br />

28- San Diego<br />

29- Gueytuypam<br />

30- San Francisco<br />

31- San Antonio<br />

32- Barrio pasado el Río<br />

(Cortés y Larraz, 2000 pp. 99-100)<br />

Mapa <strong>de</strong>l curato <strong>de</strong> San <strong>Salvador</strong>. 1768.<br />

Archivo General <strong>de</strong> Indias, Pedro Cortés y Larraz.<br />

Mapa <strong>de</strong>l curato <strong>de</strong> San <strong>Salvador</strong>.<br />

Pedro Cortés y Larraz, 1768.<br />

36<br />

37

M a pa <strong>de</strong>l Curato <strong>de</strong> San Miguel<br />

Curato <strong>de</strong> San Miguel, <strong>de</strong>scrito <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> la<br />

organización <strong>de</strong> los curatos y la subdivisión<br />

<strong>de</strong>ntro <strong>de</strong> ellos. Archivo General <strong>de</strong> Indias,<br />

Pedro Cortés y Larraz. 1768.<br />

Cuadro <strong>de</strong>l Curato <strong>de</strong> San Miguel,<br />

Archivo Histórico Arquidiocesano <strong>de</strong><br />

Guatemala,1785.<br />

En Hispanoamérica, en el transcurso <strong>de</strong>l siglo XVIII, se produjo <strong>un</strong> significativo crecimiento<br />

<strong>de</strong> la población; en alg<strong>un</strong>as regiones el aumento poblacional superó el 50%. Para Centroamérica<br />

este incremento <strong>de</strong> población no fue únicamente <strong>de</strong> carácter numérico, sino más bien <strong>de</strong> tipo<br />

étnico-social, mostrando en términos generales tres gran<strong>de</strong>s segmentos <strong>de</strong> población: indígenas,<br />

blancos y mestizos, 9 el último <strong>de</strong> estos compren<strong>de</strong> los <strong>de</strong>nominados mulatos y ladinos. Ahí mismo<br />

también habría que incluir la población esclavizada <strong>de</strong> origen africano, que alg<strong>un</strong>as fuentes<br />

primarias <strong>de</strong>nominan como negros.<br />

Durante la seg<strong>un</strong>da mitad <strong>de</strong>l siglo XVIII, América Central fue testigo <strong>de</strong> <strong>un</strong> incremento<br />

poblacional vinculado estrechamente al aumento <strong>de</strong> las activida<strong>de</strong>s productivas y comerciales.<br />

<strong>El</strong> cultivo <strong>de</strong>l añil o xiquilite fue el eje primordial <strong>de</strong>l sector exportador <strong>de</strong> la economía <strong>de</strong> Centro<br />

América hacia la última etapa colonial española. A<strong>un</strong>que el tinte y su exportación se habían llevado<br />

a cabo <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> el siglo XVI en el Reino <strong>de</strong> Guatemala, no fue sino hasta la seg<strong>un</strong>da mitad <strong>de</strong>l siglo<br />

XVIII, que se convirtió en el producto motor <strong>de</strong> la economía y el engranaje social global <strong>de</strong> la<br />

región centroamericana. 10<br />

In the course of the eighteenth century there was a significant growth in Latin America’s<br />

population; in some regions the population increase excee<strong>de</strong>d 50%. For Central America this<br />

population rise was not only of a numerical nature, but rather of an ethnic-social type, showing<br />

in general terms three large segments of the population: indigenous, white and mestizo, 9 the latter<br />

comprising the so-called mulattos and ladinos. This would also inclu<strong>de</strong> the enslaved population of<br />

African origin, which some primary sources call black.<br />

During the second half of the eighteenth century, Central America witnessed a population<br />

increase closely linked to the expansion of its productive and commercial activities. The farming<br />

of indigo or xiquilite was the main axis of the export sector of Central American economy<br />

towards the last Spanish colonial period. Although the production of the dye and its export had<br />

been carried out since the sixteenth century in the Kingdom of Guatemala, it was not <strong>un</strong>til the<br />

second half of the eighteenth century that it became the driving force behind the economy and<br />

the social fabric of the Central American region. 10<br />

38<br />

39

Las zonas productoras <strong>de</strong> tinte <strong>de</strong> añil más importantes <strong>de</strong>l<br />

Reino <strong>de</strong> Guatemala estaban ubicadas en la provincia <strong>de</strong> San<br />

<strong>Salvador</strong>; estas regiones, con su actividad, transformaron los<br />

aspectos económicos, sociales, políticos, culturales y geográficos<br />

<strong>de</strong> la sociedad sansalvadoreña <strong>de</strong> los últimos años <strong>de</strong> la<br />

dominación colonial.<br />

Como <strong>un</strong> parámetro, a finales <strong>de</strong>l siglo XVIII, Domingo<br />

Juarros y Montufar, el sacerdote diocesano y reconocido escritor<br />

guatemalteco, <strong>de</strong>scribió en su Compendio <strong>de</strong> la Historia <strong>de</strong> la<br />

Ciudad <strong>de</strong> Guatemala, en relación a la provincia <strong>de</strong> San <strong>Salvador</strong>,<br />

que esta es la más rica <strong>de</strong>l Reino <strong>de</strong> Guatemala <strong>de</strong>bido a la<br />

producción <strong>de</strong> añil o índigo, y que, a<strong>un</strong>que el xiquilite se da en<br />

la mayor parte <strong>de</strong>l Reino, no se compara con el que se trabaja en<br />

dicha provincia.<br />

J<strong>un</strong>to a esta dinámica socioeconómica se fueron configurando<br />

las elites comerciales <strong>de</strong> la capital guatemalteca en Santiago,<br />

así como las elites comerciales locales y la emergencia <strong>de</strong><br />

nuevos actores, como los campesinos con po<strong>de</strong>r económico<br />

adquisitivo, y agencia social y política que transformó la sociedad<br />

centroamericana.<br />

The most important indigo dye producing areas of the<br />

Kingdom of Guatemala were located in the province of San<br />

<strong>Salvador</strong>; the activity in these regions transformed the economic,<br />

social, political, cultural and geographical aspects of the San<br />

<strong>Salvador</strong>an society of the last years of the colonial domination.<br />

As a parameter, at the end of the eighteenth century,<br />

Domingo Juarros y Montufar, the diocesan priest and renowned<br />

Guatemalan writer, <strong>de</strong>scribed in his Compendium of the History<br />

of Guatemala City, in reference to the province of San <strong>Salvador</strong>,<br />

that this is the richest province of the Kingdom of Guatemala<br />

due to the production of indigo, and that, although xiquilite is<br />

cultivated in most of the Kingdom, it does not compare with the<br />

one produced in said province.<br />

The socioeconomic dynamics <strong>de</strong>termined that the commercial<br />

elites of the Guatemalan capital in Santiago <strong>de</strong> los Caballeros, as<br />

well as the local commercial elites, began to take shape, and that<br />

new actors emerged, such as peasants with economic purchasing<br />

power. This is how the social and political aspects that transformed<br />

Central American society were managed.<br />

Grabado <strong>de</strong> Hacienda añilera en Nicaragua. Publicado en la revista<br />

Harper´s New Monthly Magazine, 1855.<br />

40<br />

41

Recibo <strong>de</strong> tinta <strong>de</strong> 1785. Archivo Histórico<br />

Arquidiocesano <strong>de</strong> Guatemala.<br />

“Mas a<strong>un</strong>que el sembrado con tanto esplendor lujurioso<br />

florezca, y pulule la tierra velluda <strong>de</strong> sombra,<br />

no te alegres a ciegas <strong>de</strong>l tri<strong>un</strong>fo, pues largo camino<br />

le espera al colono: la planta que crece primero<br />

<strong>de</strong>l grano, tan módico jugo retiene en su vientre,<br />

que muy pocas veces su fruto repone los gastos pasados.<br />

De aquí que <strong>de</strong>jando curvar por el grano dorado los tallos,<br />

<strong>de</strong> seguido con corva segur los cercenan los mozos,<br />

y se dan a limpiar <strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>spojos el triste rastrojo,<br />

esperando por tiempo obligados futura cosecha.<br />

Luego por más <strong>de</strong> seis codos levantan su frente la mies<br />

<strong>de</strong>splegando sus hojas que iinitan a <strong>un</strong> huevo pequeño;<br />

a las cuales por cima natura,r<strong>un</strong>ibosa color azulado<br />

y <strong>de</strong>bajo <strong>un</strong> color amarillo mezclado con ver<strong>de</strong> les dio,<br />

insertándoles flores llameantes <strong>de</strong> rojo encendido.<br />

Sonríe el sembrado, si el Noto ventila las leves avenas flotantes,<br />

cual aguas azules <strong>de</strong>l túmido ponto,<br />

y agita lanzando <strong>de</strong> acá para allá con sus soplos espesas balumbas.”<br />

“But although the sown with so much lustful splendor;<br />

flourish, and swarm the lush land of shadow,<br />

do not rejoice blindly in triumph, for a long way,<br />

awaits the settler: the plant that grows first,<br />

of the grain, so mo<strong>de</strong>st juice retains in its belly,<br />

that its fruit rarely replaces past expenses.<br />

Hence letting the stems bend by the gol<strong>de</strong>n grain,<br />

Often with a hock they are cut off by the landsmen,<br />

and they give themselves to clean of spoils the sad stubble,<br />

waiting for a forced future harvest.<br />

Then for more than six cubits they lift their forehead the harvest,<br />

<strong>un</strong>folding its leaves that imitate a small egg;<br />

to which by natural top, rumbular bluish color<br />

and <strong>un</strong><strong>de</strong>rneath a yellow color mixed with green gave them,<br />

inserting flaming flowers of bright red.<br />

The seed smiles, if the Noto ventilates the slight floating oats,<br />

like blue waters of the tumid ocean,<br />

and shakes throwing back and forth with thick puffs.”<br />

Landívar, Rafael. Rusticatio mexicana. 2a. ed. / Edición Bilingüe,<br />

introducción, textos críticos, anotaciones y traducción rítmica al español <strong>de</strong><br />

Faustino Chamorro González. - - Guatemala: Universidad Rafael Landívar,<br />

2001, p. XV<br />

Grabado <strong>de</strong> producción <strong>de</strong> añil.<br />

“Description <strong>de</strong> L’Univers”,<br />

Allain M. Mallet Parós, 1683.<br />

42<br />

43

Mapa <strong>de</strong>l Curato <strong>de</strong> San Vicente <strong>de</strong> Austria.<br />

Archivo Histórico Arquidiocesano <strong>de</strong> Guatemala, 1797.<br />

<strong>El</strong> <strong>de</strong>sarrollo <strong>de</strong>l cultivo <strong>de</strong>l xiquilite y la producción <strong>de</strong> añil en la región centroamericana provocó<br />

f<strong>un</strong>damentales modificaciones en el paisaje agrario local, en lo concerniente a la tenencia y uso <strong>de</strong><br />

la tierra, pues la mayor parte <strong>de</strong> la cosecha <strong>de</strong>l añil era producida por los pequeños campesinos,<br />

<strong>de</strong>nominados “poquiteros”, quienes se <strong>de</strong>dicaban a plantar el xiquilite en pequeñas parcelas. 11<br />

Al mismo tiempo que españoles y criollos cultivaban el añil en sus tierras privadas, los indígenas<br />

sembraron y cosecharon el xiquilite en sus tierras com<strong>un</strong>ales. 12 <strong>El</strong> aumento <strong>de</strong> los cultivos y la<br />

producción <strong>de</strong>l colorante <strong>de</strong> añil a través <strong>de</strong> los obrajes (instalaciones en don<strong>de</strong> se lleva a cabo el<br />

beneficiado <strong>de</strong>l añil), contribuyó a la <strong>de</strong>scomposición <strong>de</strong> las com<strong>un</strong>ida<strong>de</strong>s indígenas en las regiones<br />

en don<strong>de</strong> se concentraron dichas activida<strong>de</strong>s agrícolas e industriales. Con esto se <strong>de</strong>sarrolló <strong>un</strong><br />

proceso <strong>de</strong> usurpación y expoliación <strong>de</strong> las tierras <strong>de</strong> las com<strong>un</strong>ida<strong>de</strong>s indígenas para <strong>de</strong>dicarlas por<br />

completo a las activida<strong>de</strong>s agropecuarias privadas. 13 Dos tipos <strong>de</strong> tenencia <strong>de</strong> tierra se configuraron<br />

durante los siglos coloniales: la com<strong>un</strong>al propia <strong>de</strong> los pueblos <strong>de</strong> indios y la privada <strong>de</strong> las haciendas. 14<br />

Sección <strong>de</strong>l mapa <strong>de</strong>l curato<br />

<strong>de</strong> Santiago Nonualco,<br />

Archivo Histórico Arquidiocesano<br />

<strong>de</strong> Guatemala. 1797.<br />

The <strong>de</strong>velopment of xiquilite cultivation and indigo production in the Central American<br />

region led to f<strong>un</strong>damental changes in the local agrarian landscape, in terms of land tenure and<br />

use, since most of the indigo harvest was produced by small farmers, called “poquiteros”, who<br />

planted xiquilite in small plots. 11<br />

While the Spaniards and Creoles cultivated indigo on their private lands, the Indians planted<br />

and harvested xiquilite on their comm<strong>un</strong>al lands. 12 The increase in cultivation and production of<br />

indigo dye through obrajes (facilities where indigo processing is carried out), contributed to the<br />

breakdown of the structures and or<strong>de</strong>r of the indigenous comm<strong>un</strong>ities in the regions where these<br />

agricultural and industrial activities were concentrated. This led to a process of usurpation and<br />

spoliation of the indigenous comm<strong>un</strong>ities’ lands to <strong>de</strong>dicate them entirely to private agricultural<br />

activities. 13 Two types of land tenure were established during the colonial centuries: the comm<strong>un</strong>al<br />

tenure of the Indian settlements and the private tenure of the haciendas. 14<br />

44<br />

45

Anverso y reverso <strong>de</strong> moneda <strong>de</strong><br />

San <strong>Salvador</strong>, acuñada con motivo<br />

<strong>de</strong> la conmemoración <strong>de</strong> la llegada<br />

al trono <strong>de</strong> Fernando VII, en 1808.<br />

En el último cuarto <strong>de</strong>l siglo XVIII los añileros se consi<strong>de</strong>raban víctimas <strong>de</strong> los<br />

comerciantes. Esto llevó a las autorida<strong>de</strong>s coloniales a intentar favorecer a los productores<br />

salvadoreños, con las claras intenciones <strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>bilitar a los po<strong>de</strong>rosos comerciantes guatemaltecos,<br />

estableciendo el montepío que ayudaría a los añileros con sus créditos. Estos y otros hechos,<br />

como el traslado <strong>de</strong> la feria <strong>de</strong>l añil <strong>de</strong> Guatemala hacia San Vicente, crearon en las provincias<br />

<strong>un</strong> conflicto <strong>de</strong> po<strong>de</strong>r, el cual n<strong>un</strong>ca pudo ser resuelto durante el período colonial. 15<br />

Durante el período <strong>de</strong> la monarquía <strong>de</strong> los borbones, el territorio centroamericano<br />

<strong>de</strong>stacaba como <strong>un</strong>a región muy importante en la producción y exportación <strong>de</strong> añil. Tanto<br />

así, que en alg<strong>un</strong>os momentos <strong>de</strong> las postrimerías <strong>de</strong>l siglo XVIII, se posicionó como la<br />

seg<strong>un</strong>da exportación en importancia <strong>de</strong> las colonias americanas <strong>de</strong> España. 16<br />

La sociedad colonial sansalvadoreña experimentó transformaciones que llevaron<br />

a la ocurrencia <strong>de</strong> <strong>un</strong> nuevo grupo étnico, “los mulatos”, los cuales estarían fuertemente<br />

vinculados a la industria <strong>de</strong> la producción <strong>de</strong> añil y la gana<strong>de</strong>ría, y que serían parte <strong>de</strong> su<br />

cultura social, la cual le permitiría garantizar su acceso a la cultura hispanizada. Este estrato<br />

étnico mulato se <strong>de</strong>terminó basado en las contradicciones entre la superestructura-jurídica<br />

colonial y los procesos dinámicos <strong>de</strong>l domino <strong>de</strong>l mismo; así lentamente los campesinos<br />

mulatos fueron erigiendo su propia cultura proto-hispana al margen <strong>de</strong> la estructura <strong>de</strong> la<br />

sociedad colonial. 17<br />

Grabado con registro <strong>de</strong> ingresos y gastos <strong>de</strong>l<br />

Reino <strong>de</strong> Guatemala <strong>de</strong> 1786. Cortesía <strong>de</strong>l Museo<br />

Nacional <strong>de</strong> Historia. Guatemala.<br />

In the last quarter of the eighteenth century, indigo workers were consi<strong>de</strong>red to be<br />

victims of the merchants. As a consequence, the colonial authorities tried to favour the<br />

<strong>Salvador</strong>an producers, with the clear intention of weakening the powerful Guatemalan<br />

merchants, by establishing the assistance f<strong>un</strong>d (montepío) that would help the indigo<br />

producers with their credits. These and other events, such as the transfer of the indigo<br />

fair from Guatemala to San Vicente, created a power struggle in the provinces, which could<br />

never be resolved during the colonial period. 15<br />

During the period of the Bourbon monarchy, the Central American territory stood out<br />

as a very important region in the production and export of indigo. So much so that, at<br />

some point in the late eighteenth century, it was positioned as the second most important<br />

export of the American colonies of Spain. 16<br />

San <strong>Salvador</strong>’s colonial society <strong>un</strong><strong>de</strong>rwent transformations that led to the emergence<br />

of a new ethnic group, “the mulattos”. They would be strongly linked to the indigo<br />

production industry and livestock, which would be part of their social culture. This in<br />

turn would guarantee their access to the Hispanic culture. This mulatto ethnic stratum<br />

was <strong>de</strong>termined based on the contradictions between the colonial legal superstructure and<br />

the dynamic processes of colonial rule. Thus, the mulatto peasants slowly built up their<br />

own proto-Hispanic culture outsi<strong>de</strong> the structure of colonial society. 17<br />

46<br />

47

<strong>El</strong> agente geográfico-productivo, ligado al cultural y al<br />

poblacional, <strong>de</strong>terminó las ten<strong>de</strong>ncias <strong>de</strong> la ocupación <strong>de</strong> la<br />

tierra, así como el inmediato interés por su apropiación; todo ello<br />

sufragó la edificación <strong>de</strong> <strong>un</strong>a diversidad <strong>de</strong> contextos en los que<br />

se <strong>de</strong>sarrolló la vida colonial. 18 <strong>El</strong> establecimiento <strong>de</strong> las haciendas<br />

<strong>de</strong>finitivamente aceleró el proceso <strong>de</strong>l mestizaje biológico-cultural,<br />

al convertirse estas áreas en centros <strong>de</strong> atracción <strong>de</strong> mano <strong>de</strong> obra<br />

<strong>de</strong> diversa proce<strong>de</strong>ncia étnica y cultural. 19<br />

Al inicio <strong>de</strong>l siglo XVIII, al ascenso <strong>de</strong> la dinastía <strong>de</strong> los Borbones,<br />

asesorados por sus consejeros partidarios <strong>de</strong>l mo<strong>de</strong>lo administrativo<br />

francés, esta Casa Real formuló <strong>un</strong>a reorganización <strong>de</strong> la estructura<br />

administrativa, fiscal y militar <strong>de</strong>l Imperio español. Con ello, Las<br />

Reformas Borbónicas fueron el conj<strong>un</strong>to <strong>de</strong> transformaciones<br />

político-administrativas, producidas a partir <strong>de</strong> Carlos III (1759-<br />

1788) y Carlos IV (1788-1808), inspiradas en el absolutismo francés<br />

y respaldadas en las i<strong>de</strong>as filosóficas <strong>de</strong>l Despotismo Ilustrado. En la<br />

América Central las reformas borbónicas llegaron tempranamente;<br />

sin embargo, no fue hasta la llegada <strong>de</strong> Carlos III en 1759, que se<br />

proyectó <strong>un</strong>a ofensiva <strong>de</strong>stinada a reestructurar en su totalidad la<br />

administración política, fiscal y militar <strong>de</strong> Centroamérica. 20<br />

The geographical-productive factor, together with the cultural<br />

and population element, <strong>de</strong>termined the ten<strong>de</strong>ncies of land<br />

occupation, as well as the immediate interest in its appropriation,<br />

all of which financed the construction of a diversity of contexts<br />

in which colonial life took place. 18 The establishment of the<br />

haciendas <strong>de</strong>finitely accelerated the process of biological-cultural<br />

crossbreeding, as these areas became hubs for attracting labour<br />

from diverse ethnic and cultural backgro<strong>un</strong>ds. 19<br />

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, with the rise of<br />

the Bourbon dynasty, advised by its co<strong>un</strong>sellors who supported<br />

the French administrative mo<strong>de</strong>l, this Royal House formulated a<br />

reorganisation of the administrative, fiscal and military structure<br />

of the Spanish Empire. Thus, the Bourbon Reforms were the set of<br />

laws and political-administrative transformations implemented<br />

by Charles III (1759-1788) and Charles IV (1788-1808), inspired<br />

by French absolutism and supported by the philosophical i<strong>de</strong>as<br />

of Enlightened Despotism. The Bourbon Reforms ma<strong>de</strong> their way<br />

early into Central America; however, it was not <strong>un</strong>til the arrival<br />

of Charles III in 1759 that an offensive was planned to completely<br />

restructure the political, fiscal and military administration of<br />

Central America. 20<br />

Grabado <strong>de</strong>l valle <strong>de</strong> Jiboa. Publicado en<br />

“Harper´s Weekly”, Nueva York, sección<br />

“The Illustrated News of the World”, 1891.<br />

48<br />

49

Grabado cerca <strong>de</strong> Granada, al fondo lago Nicaragua.<br />

Harpers New Monthly Magazine, 1855.<br />

Las modificaciones medulares <strong>de</strong> las reformas borbónicas para<br />

la América Central fueron: a) promover los intercambios directos<br />

entre la península Ibérica y las colonias para el <strong>de</strong>sarrollo <strong>de</strong> las<br />

com<strong>un</strong>icaciones y el comercio; b) limitar el po<strong>de</strong>r eclesiástico,<br />

por medio <strong>de</strong> la expropiación <strong>de</strong> los bienes <strong>de</strong> la Iglesia y la<br />

disminución <strong>de</strong> sus privilegios; c) apoyar a los productores <strong>de</strong> las<br />

provincias <strong>de</strong> Centroamérica con el fin <strong>de</strong> liberarlos <strong>de</strong>l control <strong>de</strong><br />

los comerciantes <strong>de</strong> la capital, Santiago <strong>de</strong> Guatemala; d) reformar la<br />

estructura administrativa por medio <strong>de</strong> la instauración <strong>de</strong>l régimen<br />

<strong>de</strong> inten<strong>de</strong>ncias, con el fin <strong>de</strong> reemplazar a los “oficiales corruptos”<br />

<strong>de</strong>l interior ligados a los intereses locales; e) transformar el sistema<br />

impositivo con el fin <strong>de</strong> obtener más ingresos fiscales para financiar<br />

la creciente estructura <strong>de</strong>l po<strong>de</strong>r colonial; y f) intensificar la <strong>de</strong>fensa<br />

militar para contener las activida<strong>de</strong>s comerciales y militares <strong>de</strong> los<br />

ingleses en Centroamérica. 21<br />

Las i<strong>de</strong>as ilustradas que iban <strong>de</strong>ambulando en las diversas<br />

esferas <strong>de</strong> la vida pública española <strong>de</strong>s<strong>de</strong> mediados <strong>de</strong>l siglo XVIII,<br />

no apelaban solamente por mejorar y <strong>de</strong>sarrollar la educación, sino<br />

también a resguardar cierta igualdad femenina en alg<strong>un</strong>as tareas o a<br />

reprochar la holgazanería <strong>de</strong> la nobleza; con ello plantearon formas<br />

<strong>de</strong> luchar contra la indigencia, la pobreza y el carácter pueblerino <strong>de</strong><br />

las costumbres <strong>de</strong> la población. 22<br />

The core modifications of the Bourbon reforms for Central<br />

America were: a) to promote direct exchanges between the<br />

Iberian Peninsula and the colonies for the <strong>de</strong>velopment of<br />

comm<strong>un</strong>ications and tra<strong>de</strong>; b) to limit ecclesiastical power,<br />

through the expropriation of Church property and the<br />

diminishing of its privileges; c) to support producers in the<br />

provinces of Central America in or<strong>de</strong>r to free them from the<br />

control of the merchants of Santiago <strong>de</strong> Guatemala, the capital;<br />

d) to reform the administrative structure by establishing the<br />

regime of inten<strong>de</strong>ncies so as to replace the “corrupt officials” in<br />

the interior who were linked to local interests; e) transforming<br />

the tax system in or<strong>de</strong>r to obtain more tax revenue to finance the<br />

growing structure of colonial power; and f) intensifying military<br />

<strong>de</strong>fense to restrain the commercial and military activities of the<br />

British in Central America. 21<br />

The enlightened i<strong>de</strong>as that wan<strong>de</strong>red in the various spheres<br />

of Spanish public life since the mid–eighteenth century not only<br />

appealed to improve and <strong>de</strong>velop education, but also to safeguard<br />

a certain equality for women in some tasks or to reproach the<br />

laziness of the nobility, thus proposing ways of fighting against<br />

<strong>de</strong>stitution, poverty and the provincial idiosyncrasies of the<br />

population’s customs. 22<br />

Página opuesta: “Tornaguía emitida por la<br />

Real Receptoría <strong>de</strong> alcabalas<br />

<strong>de</strong> San Miguel, en 1809”.<br />

50<br />

51

La Reforma Administrativa conllevó a la creación <strong>de</strong>l Régimen <strong>de</strong><br />

Inten<strong>de</strong>ncias, con la intención <strong>de</strong> ejercer el po<strong>de</strong>r imperial sobre el mayor<br />

número <strong>de</strong> socieda<strong>de</strong>s regionales <strong>de</strong> América. En Centroamérica, el Régimen<br />

<strong>de</strong> Inten<strong>de</strong>ncias se ejecutó entre 1785 y 1787; a partir <strong>de</strong> ello, el territorio<br />

<strong>de</strong> la Audiencia <strong>de</strong> Guatemala se dividió en cinco inten<strong>de</strong>ncias: Chiapas,<br />

Guatemala, San <strong>Salvador</strong>, Comayagua y León. Sin embargo, el esfuerzo <strong>de</strong> la<br />

Corona <strong>de</strong> suscitar nuevas metrópolis no fue posible, pues la administración<br />

colonial no logró romper el po<strong>de</strong>r <strong>de</strong> los comerciantes monopolistas <strong>de</strong> la<br />

ciudad <strong>de</strong> Guatemala. Así lejos <strong>de</strong> fortalecer el dominio colonial sobre la elite<br />

mercantil guatemalteca, esta incrementó su po<strong>de</strong>r. Como resultado <strong>de</strong> este<br />

proceso, los provincianos vieron el cambio <strong>de</strong> la administración colonial<br />

como <strong>un</strong>a contribución más al po<strong>de</strong>r <strong>de</strong> la ciudad <strong>de</strong> Guatemala, por sobre<br />

los productores <strong>de</strong> las provincias <strong>de</strong> la América Central. 23<br />

Con los nuevos cambios en la administración política <strong>de</strong> las colonias<br />

españolas en América, la Alcaldía Mayor <strong>de</strong> San <strong>Salvador</strong>, la cual estaba<br />

formada por las provincias <strong>de</strong> San <strong>Salvador</strong>, San Vicente <strong>de</strong> Austria y<br />

San Miguel, se elevó a la categoría <strong>de</strong> inten<strong>de</strong>ncia por Real Cédula <strong>de</strong>l 17<br />

<strong>de</strong> septiembre <strong>de</strong> 1785. En 1786 se erigió la Inten<strong>de</strong>ncia <strong>de</strong> San <strong>Salvador</strong>,<br />

siendo su primer gobernador-inten<strong>de</strong>nte el Oidor <strong>de</strong> la Audiencia <strong>de</strong><br />

Guatemala, D. José Ortiz <strong>de</strong> la Peña. Esta circ<strong>un</strong>scripción se <strong>de</strong>nominó<br />

Inten<strong>de</strong>ncia-Corregimiento, pues no se trataba <strong>de</strong> <strong>un</strong> mando <strong>de</strong> tipo militar.<br />

Por su parte la Inten<strong>de</strong>ncia <strong>de</strong> San <strong>Salvador</strong> se dividió en cuatro partidos:<br />

el <strong>de</strong> Santa Ana, San <strong>Salvador</strong>, San Vicente y San Miguel, sustituyéndose<br />

la <strong>de</strong>nominación <strong>de</strong> provincias 24 por la <strong>de</strong> partidos, como consta en las<br />

Or<strong>de</strong>nanzas dadas para el establecimiento <strong>de</strong> las inten<strong>de</strong>ncias.<br />

The Administrative Reform led to the creation of the Regime of<br />

Inten<strong>de</strong>ncies, with the intention of exercising imperial power over the<br />

greatest number of regional societies in America. In Central America,<br />

the Regime of Inten<strong>de</strong>ncies was executed between 1785 and 1787; after<br />

that, the territory of the Audiencia of Guatemala was divi<strong>de</strong>d into five<br />

inten<strong>de</strong>ncies: Chiapas, Guatemala, San <strong>Salvador</strong>, Comayagua and León.<br />

However, the Crown’s effort to create new metropolises was not achieved,<br />

since the colonial administration did not succeed in breaking the power<br />

of the monopolistic merchants of Guatemala City. Hence, far from<br />

strengthening the colonial rule over the Guatemalan mercantile elite, the<br />

latter increased its power. As a result of this process, the provincials saw<br />

the change in colonial administration as another contribution to the power<br />

of Guatemala City over the producers of the Central American provinces. 23<br />

In compliance with the new changes in the political administration of<br />

the Spanish colonies in America, the Mayor’s Office of San <strong>Salvador</strong>, which<br />

was formed by the provinces of San <strong>Salvador</strong>, San Vicente <strong>de</strong> Asturia and<br />

San Miguel, was elevated to the category of Intendancy by Royal Decree on<br />

September 17, 1785. In 1786 the Intendancy of San <strong>Salvador</strong> was erected,<br />

its first governor-intendant being the Oidor <strong>de</strong> la Audiencia of Guatemala,<br />

Mr. José Ortiz <strong>de</strong> la Peña. As it was not a military type administration, this<br />

institution was called Inten<strong>de</strong>ncia-Corregimiento. It was divi<strong>de</strong>d into four<br />

partidos: Santa Ana, San <strong>Salvador</strong>, San Vicente and San Miguel, with the<br />

<strong>de</strong>nomination of provinces 24 being replaced by that of partidos, as stated<br />

in the ordinances given for the establishment of the inten<strong>de</strong>ncies.<br />

Grabado <strong>de</strong> la catedral <strong>de</strong> Comayagua, Honduras.<br />

Los <strong>Estado</strong>s <strong>de</strong> Centro América, Ephraim Squier, 1855.<br />

52<br />

53

Tiangue frente a la catedral <strong>de</strong> San <strong>Salvador</strong>.<br />

Frank Leslie’s Ilustrated Newspaper, 1873.<br />

Al establecer la Inten<strong>de</strong>ncia <strong>de</strong> San <strong>Salvador</strong>, el Rey recalcaba<br />

que con el nuevo sistema se provocaría en las tres provincias <strong>de</strong><br />

la antigua Alcaldía Mayor <strong>de</strong> San <strong>Salvador</strong>, <strong>un</strong> crecimiento en<br />

el cultivo y producción <strong>de</strong> sus frutos, principalmente <strong>de</strong>l añil;<br />

esto haría que floreciera el comercio. <strong>El</strong> sistema <strong>de</strong> inten<strong>de</strong>ncias<br />

perseguía mejorar las condiciones sociales <strong>de</strong> los vasallos, y como<br />

consecuencia, conseguir altos ingresos para la Real Hacienda. A la<br />

luz <strong>de</strong> ello, los nuevos f<strong>un</strong>cionarios vendrían a erradicar los abusos<br />

contra las com<strong>un</strong>ida<strong>de</strong>s indígenas por parte <strong>de</strong> los corregidores y<br />

alcal<strong>de</strong>s mayores, así como a <strong>de</strong>sarticular las re<strong>de</strong>s <strong>de</strong> corrupción<br />

que estos habían establecido a través <strong>de</strong> los repartimientos <strong>de</strong><br />

mercancías. 25<br />

Como se ha mencionado, el grupo mercantil guatemalteco<br />

monopolizaba el comercio exterior <strong>de</strong> exportación y <strong>de</strong><br />

importación, a<strong>de</strong>más <strong>de</strong> ello ejercía <strong>un</strong> control abusivo sobre la<br />

mayoría <strong>de</strong> los circuitos mercantiles <strong>de</strong>l Reino <strong>de</strong> Guatemala. Esta<br />

situación constituía <strong>un</strong> monopolio con <strong>un</strong>a lógica <strong>de</strong> régimen <strong>de</strong><br />

explotación, por parte <strong>de</strong> la capital sobre las provincias; dicho<br />

expolio generaba <strong>un</strong> alto grado <strong>de</strong> resentimiento entre las elites<br />

provinciales. Ese antagonismo y conflicto eran rasgos propios<br />

<strong>de</strong> las relaciones entre las elites terratenientes y mercantiles <strong>de</strong><br />

las provincias, contra el capital comercial guatemalteco, y estos<br />

a su vez generaron y agudizaron los localismos. 26 A partir <strong>de</strong> ello,<br />

se abrieron rendijas en las que se imaginaron la posibilidad <strong>de</strong><br />

autonomías locales y regionales respecto a la administración<br />

colonial española.<br />

When establishing the Intendancy of San <strong>Salvador</strong>, the King<br />

stressed that the new system would cause an increase in the<br />

cultivation and production of its produce, mainly of indigo, in<br />

the three provinces of the former Mayor’s Office of San <strong>Salvador</strong>;<br />

this would lead to a flourishing of tra<strong>de</strong>. The aim of the system of<br />

inten<strong>de</strong>ncies was to improve the social conditions of the vassals<br />

and, as a consequence, to achieve high tax revenues for the Royal<br />

Treasury. Thus, the new officials would come to eradicate the<br />

abuses against indigenous comm<strong>un</strong>ities by the magistrates and<br />