Revista Veterinaria Zacatecas 2007 - Universidad Autónoma de ...

Revista Veterinaria Zacatecas 2007 - Universidad Autónoma de ...

Revista Veterinaria Zacatecas 2007 - Universidad Autónoma de ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Lic Alfredo Femat Bañuelos<br />

Rector <strong>de</strong> la <strong>Universidad</strong> Autónoma <strong>de</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong><br />

M C Francisco Javier Domínguez Garay<br />

Secretario General<br />

Ph D Héctor René Vega Carrillo<br />

Secretario Académico<br />

C P Emilio Morales Vera<br />

Secretario Administrativo<br />

M en C Jesús Octavio Enríquez Rivera<br />

Director <strong>de</strong> la Unidad Académica <strong>de</strong> Medicina <strong>Veterinaria</strong> y Zootecnia<br />

M V Z Juan Manuel Ramos Bugarin<br />

Responsable <strong>de</strong>l Programa <strong>de</strong> Licenciatura<br />

Ph D José Manuel Silva Ramos<br />

Responsable <strong>de</strong>l Programa <strong>de</strong> Doctorado<br />

Dr en C Francisco Javier Escobar Medina<br />

Responsable <strong>de</strong>l Programa <strong>de</strong> Maestría y Editor <strong>de</strong> la <strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Veterinaria</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong><br />

Dr en C Rómulo Bañuelos Valenzuela<br />

Coordinador <strong>de</strong> Investigación<br />

M en C J Jesús Gabriel Ortiz López<br />

Secretario Administrativo<br />

M en C Francisco Flores Sandoval<br />

Director <strong>de</strong> la <strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Veterinaria</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong>

Comité Editorial<br />

Aréchiga Flores, Carlos Fernando PhD<br />

Bañuelos Valenzuela, Rómulo Dr en C<br />

De la Colina Flores, Fe<strong>de</strong>rico M en C<br />

Echavarria Chairez, Francisco Guadalupe Ph D<br />

Gallegos Sánchez, Jaime Dr<br />

Grajales Lombana, Henry Dr en C<br />

Góngora Orjuela, Agustín Dr en C<br />

Meza Herrera, César PhD<br />

Ocampo Barragán, Ana María M en C<br />

Pescador Salas, Nazario Ph D<br />

Rodríguez Frausto, Heriberto M en C<br />

Rodríguez Tenorio, Daniel M en C<br />

Silva Ramos, José Manuel Ph D<br />

Urrutia Morales, Jorge Dr en C<br />

Viramontes Martínez, Francisco<br />

Unidad Académica <strong>de</strong> Medicina<br />

<strong>Veterinaria</strong> y Zootecnia, <strong>Universidad</strong><br />

Autónoma <strong>de</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong> (UAMVZ-<br />

UAZ)<br />

UAMVZ-UAZ<br />

UAMVZ-UAZ<br />

INIFAP - <strong>Zacatecas</strong><br />

Colegio <strong>de</strong> Postgraduados<br />

Facultad <strong>de</strong> Medicina <strong>Veterinaria</strong> y<br />

Zootecnia, <strong>Universidad</strong> Nacional <strong>de</strong><br />

Colombia<br />

Facultad <strong>de</strong> Medicina <strong>Veterinaria</strong> y<br />

Zootecnia, <strong>Universidad</strong> <strong>de</strong> los Llanos,<br />

Colombia<br />

Unidad Regional Universitaria <strong>de</strong> Zonas<br />

Áridas, <strong>Universidad</strong> Autónoma <strong>de</strong><br />

Chapingo<br />

UAMVZ-UAZ<br />

Facultad <strong>de</strong> Medicina <strong>Veterinaria</strong> y<br />

Zootecnia, <strong>Universidad</strong> Autónoma <strong>de</strong>l<br />

Estado <strong>de</strong> México<br />

UAMVZ-UAZ<br />

UAMVZ-UAZ<br />

UAMVZ-UAZ<br />

Campo Experimental San Luis. INIFAP<br />

UAMVZ-UAZ

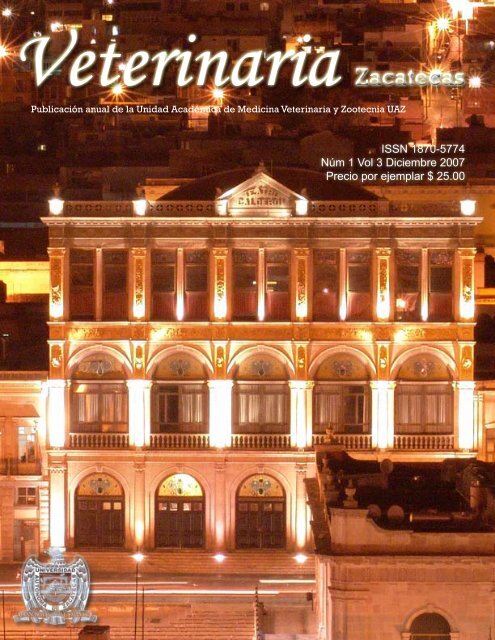

Nuestra Portada<br />

Teatro Fernando Cal<strong>de</strong>rón, Patrimonio <strong>de</strong> la <strong>Universidad</strong> Autónoma <strong>de</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong>.<br />

<strong>Zacatecas</strong>, Zac.<br />

Fotografía: Salvador Romo Gallardo, tel 8 99 24 29, e-mail jerg14@hotmail.com<br />

<strong>Veterinaria</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong> es una publicación anual <strong>de</strong> la Unidad Académica <strong>de</strong> Medicina<br />

<strong>Veterinaria</strong> y Zootecnia <strong>de</strong> la <strong>Universidad</strong> Autónoma <strong>de</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong>. ISSN: 1870-5774. Sólo<br />

se autoriza la reproducción <strong>de</strong> artículos en los casos que se cite la fuente.<br />

Correspon<strong>de</strong>ncia dirigirla a: <strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Veterinaria</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong>. <strong>Revista</strong> <strong>de</strong> la Unidad<br />

Académica <strong>de</strong> Medicina <strong>Veterinaria</strong> y Zootecnia <strong>de</strong> la <strong>Universidad</strong> Autónoma <strong>de</strong><br />

<strong>Zacatecas</strong>. Carretera Panamericana, tramo <strong>Zacatecas</strong>-Fresnillo Km 31.5. Apartados Postales<br />

9 y 11, Calera <strong>de</strong> Víctor Rosales, Zac. CP 98 500. Teléfono 01 (478) 9 85 12 55. Fax: 01<br />

(478) 9 85 02 02. E-mail: vetuaz@cantera.reduaz.mx. URL www.reduaz.mx/uaz.mvz<br />

Precio por cada ejemplar $25.00<br />

Distribución: Unidad Académica <strong>de</strong> Medicina <strong>Veterinaria</strong> y Zootecnia <strong>de</strong> la <strong>Universidad</strong><br />

Autónoma <strong>de</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong>.

CONTENIDO<br />

Artículos <strong>de</strong> revisión<br />

Review articles<br />

Primer parto en el ganado bovino productor <strong>de</strong> carne<br />

First calving in beef cows<br />

Alejandra Larios-Jiménez, Francisco Flores-Sandoval, Francisco Javier<br />

Escobar-Medina, Fe<strong>de</strong>rico <strong>de</strong> la Colina-Flores………………………………….<br />

1-12<br />

El comportamiento higiénico <strong>de</strong> la abeja Apis mellifera y su aplicación en el<br />

control <strong>de</strong> la varroosis<br />

Hygienic behavior in Apis mellifera bee on varroosis control<br />

Carlos Aurelio Medina-Flores…………………………………………………..<br />

13-20<br />

Artículos científicos<br />

Original research articles<br />

Eficiencia reproductiva en el ganado bovino productor <strong>de</strong> carne<br />

Reproductive efficiency in beef cow<br />

Alejandra Larios-Jiménez, Francisco Javier Escobar-Medina, Francisco Flores-<br />

Sandoval, Fe<strong>de</strong>rico <strong>de</strong> la Colina-Flores…………………………………………<br />

21-31<br />

Comportamiento reproductivo en ovejas <strong>de</strong> pelo a 22º 58’ N<br />

Reproductive behavior of hair ewes at 22º 58’ N<br />

Ángel Hernán<strong>de</strong>z-Santillán, Francisco Javier Escobar-Medina, Carlos<br />

Fernando Aréchiga-Flores, Fe<strong>de</strong>rico <strong>de</strong> la Colina-Flores.………………………<br />

33-38<br />

Efecto <strong>de</strong>l uso <strong>de</strong> almohadillas impregnadas con ácido fórmico sobre la<br />

infestación <strong>de</strong> Varroa <strong>de</strong>structor y la producción <strong>de</strong> miel<br />

José Luís Rodríguez Castillo, Yonatan Sandoval Olmos, Francisco Javier<br />

Escobar Medina, Carlos Fernando Aréchiga Flores, Francisco Javier Gutiérrez<br />

Piña, Jairo Iván Aguilera Soto, Carlos Aurelio Medina Flores............................<br />

39-44

PRIMER PARTO EN EL GANADO BOVINO PRODUCTOR DE CARNE<br />

Alejandra Larios-Jiménez, Francisco Flores-Sandoval, Francisco Javier Escobar-Medina, Fe<strong>de</strong>rico <strong>de</strong> la<br />

Colina-Flores<br />

Unidad Académica <strong>de</strong> Medicina <strong>Veterinaria</strong> y Zootecnia <strong>de</strong> la <strong>Universidad</strong> Autónoma <strong>de</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong><br />

E-mail: fescobar@uaz.edu.mx<br />

RESUMEN<br />

Las vaquillas tienen la capacidad <strong>de</strong> parir a los dos años <strong>de</strong> edad; esto <strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong> la edad a la pubertad y la<br />

concepción. La nutrición, raza <strong>de</strong>l animal, época <strong>de</strong>l año y presencia <strong>de</strong>l macho, entre otros factores, pue<strong>de</strong>n<br />

influir sobre la edad a la pubertad. En la presente revisión se discute esta parte <strong>de</strong> la fisiología reproductiva<br />

<strong>de</strong>l animal.<br />

Palabras clave: pubertad, primera concepción, primer parto, ganado bovino productor <strong>de</strong> carne<br />

<strong>Veterinaria</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong> <strong>2007</strong>; 3: 1-12<br />

INTRODUCCIÓN<br />

La eficiencia reproductiva óptima <strong>de</strong>l ganado<br />

productor <strong>de</strong> carne se registra cuando las vaquillas<br />

presentan su primer parto a los dos años <strong>de</strong> edad 1<br />

y en la vida adulta mantienen intervalos entre<br />

partos <strong>de</strong> 12 meses <strong>de</strong> duración. 2<br />

Para la edad óptima al primer parto se<br />

requiere la concepción entre 15 y 16 meses <strong>de</strong><br />

edad, y antes <strong>de</strong> ésta la presencia <strong>de</strong> la pubertad. 1<br />

Según los datos <strong>de</strong> la literatura, el avance genético<br />

ha permitido cambios importantes en el período<br />

prepuberal, las vaquillas en la actualidad<br />

presentan la pubertad a menor edad y peso que<br />

anteriormente, 3 también en algunos estudios se ha<br />

encontrado mayor influencia <strong>de</strong> la edad que <strong>de</strong>l<br />

peso en el momento <strong>de</strong> la concepción; 4 lo cual<br />

permite alimentar los animales con raciones <strong>de</strong><br />

menor concentración <strong>de</strong> energía y, por<br />

consiguiente, <strong>de</strong> menor precio; el resultado, se<br />

pue<strong>de</strong> aumentar la rentabilidad <strong>de</strong> las empresas<br />

gana<strong>de</strong>ras. 5<br />

En algunas explotaciones, los animales<br />

durante la mayor parte <strong>de</strong>l tiempo se alimentan<br />

con pastoreo en gramas nativas, únicamente se les<br />

ofrece complemento alimenticio en las<br />

temporadas <strong>de</strong> sequía. 6 Lo anterior invita al<br />

análisis <strong>de</strong> los aspectos más importantes <strong>de</strong>l<br />

período <strong>de</strong>l nacimiento al primer parto. En el<br />

presente estudio se revisó la información<br />

disponible <strong>de</strong> pubertad, primera concepción y<br />

primer parto en las vacas productoras <strong>de</strong> carne.<br />

PUBERTAD<br />

La pubertad en la becerra es el primer<br />

comportamiento <strong>de</strong> celo seguido <strong>de</strong> en un ciclo<br />

<strong>de</strong> 21 días <strong>de</strong> duración. La hembra <strong>de</strong>l<br />

nacimiento a poco antes <strong>de</strong> la pubertad<br />

permanece en un estado anovulatorio no cíclico:<br />

anestro. No se presenta el concierto hormonal<br />

entre hipotálamo, hipófisis y gónada que conduce<br />

a la ovulación. Esto se <strong>de</strong>be a la<br />

retroalimentación negativa <strong>de</strong>l estradiol sobre el<br />

hipotálamo; 7-11 con lo cual se reduce la secreción<br />

pulsátil <strong>de</strong> GnRH, y por consiguiente la<br />

disminución <strong>de</strong> la frecuencia <strong>de</strong> pulsos <strong>de</strong><br />

gonadotropinas <strong>de</strong>l lóbulo anterior <strong>de</strong> la<br />

hipófisis. 7,12 El resultado, los folículos ováricos<br />

no maduran a<strong>de</strong>cuadamente, su secreción <strong>de</strong><br />

estradiol no es suficiente para generar el pulso<br />

cíclico <strong>de</strong> GnRH/LH y la ovulación no se<br />

presenta. 13,14<br />

La concentración sanguínea <strong>de</strong><br />

gonadotropinas se incrementa <strong>de</strong> la semana 4 a<br />

14 <strong>de</strong> edad en las becerras, posteriormente se<br />

reduce y se mantiene a bajo nivel hasta la semana<br />

30, aproximadamente; 10,15-17 este incremento<br />

coinci<strong>de</strong> con el aumento en la población folicular<br />

y <strong>de</strong>l diámetro en el folículo <strong>de</strong> mayor tamaño,<br />

con el subsiguiente incremento en la secreción <strong>de</strong><br />

estradiol; 14,16,18-20 y se <strong>de</strong>be a la insuficiente<br />

sensibilidad <strong>de</strong>l hipotálamo al efecto inhibitorio<br />

<strong>de</strong>l estradiol, durante las primeras semanas <strong>de</strong><br />

vida <strong>de</strong>l animal. 21

FSH (ng/ml)<br />

Población folicular<br />

Diámetro (mm)<br />

16<br />

14<br />

12<br />

10<br />

8<br />

6<br />

4<br />

2<br />

0<br />

2 10 18 26 34 42 50 58<br />

Edad (semanas)<br />

Figura 1. Diámetro <strong>de</strong>l folículo dominante en las oleadas <strong>de</strong> crecimiento folicular<br />

en vaquillas. Primera ovulación a las 56.0 ± 1.2 semanas <strong>de</strong> edad 16,24<br />

1.6<br />

1.4<br />

1.2<br />

1<br />

0.8<br />

0.6<br />

0.4<br />

0.2<br />

0<br />

FSH<br />

Fol<br />

16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31<br />

Edad <strong>de</strong> la becerra (días)<br />

9<br />

8<br />

7<br />

6<br />

5<br />

4<br />

3<br />

2<br />

1<br />

0<br />

Figura 2. Concentración sérica <strong>de</strong> FSH y población <strong>de</strong> folículos ≥4mm <strong>de</strong><br />

diámetro, en becerras <strong>de</strong> 2 semanas <strong>de</strong> edad 16<br />

2

La concentración sérica <strong>de</strong> LH aumenta<br />

paulatinamente <strong>de</strong>spués <strong>de</strong>l la semana 30 <strong>de</strong> edad<br />

<strong>de</strong> las becerras, 14, 21,22 con el subsiguiente<br />

incremento en el diámetro <strong>de</strong>l folículo <strong>de</strong> mayor<br />

tamaño y la producción <strong>de</strong> estrógenos. 23 El<br />

diámetro <strong>de</strong>l folículo dominante (Figura 1) y su<br />

producción <strong>de</strong> estradiol se incrementan <strong>de</strong> oleada<br />

en oleada conforme la vaquilla se aproxima a la<br />

primera ovulación. 16,22-25 Los pulsos <strong>de</strong> secreción<br />

<strong>de</strong> LH aumentan en el período previo a la primera<br />

ovulación; 13,15 la FSH permanece al mismo<br />

nivel. 16,24 El crecimiento folicular en el período<br />

prepuberal se realiza en oleadas, 26,27 <strong>de</strong> la misma<br />

manera como se presenta en las vacas adultas, 28<br />

con aumento en la concentración sérica <strong>de</strong> FSH<br />

16, 27,29<br />

antes <strong>de</strong> cada oleada (Figura 2).<br />

La vaquilla <strong>de</strong>sarrolla su aparato genital<br />

<strong>de</strong> la semana 2 a la 14 y <strong>de</strong> la 34 al período previo<br />

a la pubertad, 20 <strong>de</strong> la misma manera como lleva a<br />

cabo el <strong>de</strong>sarrollo <strong>de</strong> folículos antrales. 19,22<br />

La primera ovulación se presenta <strong>de</strong>bido<br />

a la reducción <strong>de</strong> la retroalimentación negativa <strong>de</strong>l<br />

estradiol; 30-33 se disminuyen los receptores<br />

hipotalámicos para esta hormona, 22 lo cual<br />

permite la reactivación <strong>de</strong>l eje hipotálamohipófisis-gónada<br />

y la ovulación se presenta. El<br />

proceso en forma sucesiva es como sigue: se<br />

incrementa <strong>de</strong> la frecuencia <strong>de</strong> pulsos <strong>de</strong> GnRH en<br />

el hipotálamo, aumenta la secreción <strong>de</strong><br />

gonadotropinas en la hipófisis, 13,16,22,25,34 se<br />

incrementa el crecimiento folicular en el ovario<br />

con la subsiguiente producción <strong>de</strong><br />

estradiol, 16,23,24,25 particularmente algunos días<br />

antes <strong>de</strong> la primera ovulación; 14,23 el aumento <strong>de</strong>l<br />

nivel <strong>de</strong> esta hormona induce la secreción<br />

preovulatoria <strong>de</strong> LH 35,36 y se presenta la ovulación<br />

generalmente sin la manifestación <strong>de</strong> celo. 24,37<br />

Posteriormente se forma un cuerpo lúteo en cada<br />

folículo que ha ovulado, 38,39 don<strong>de</strong> se produce<br />

progesterona. La vida <strong>de</strong>l cuerpo lúteo producto<br />

<strong>de</strong> la primera ovulación generalmente es menor<br />

duración que en los ciclos ováricos normales,<br />

menor a 21 días. 24,37 La presencia <strong>de</strong> progesterona<br />

antes <strong>de</strong> las ovulaciones siguientes establece las<br />

condiciones apropiadas para la manifestación <strong>de</strong>l<br />

celo y se alcanza el equilibrio hormonal necesario<br />

para normalizar la duración <strong>de</strong> los ciclos<br />

estrales. 40 Los factores que influyen sobre la edad a<br />

la pubertad en las vaquillas son: nutrición, 41-45<br />

raza <strong>de</strong>l animal, 46 época <strong>de</strong>l año 47 y presencia <strong>de</strong>l<br />

macho. 48<br />

Nutrición<br />

La nutrición es un factor importante para<br />

<strong>de</strong>senca<strong>de</strong>nar la pubertad en el ganado bovino, las<br />

vaquillas alimentadas con cantida<strong>de</strong>s a<strong>de</strong>cuadas<br />

<strong>de</strong> energía inician su actividad ovárica cíclica más<br />

jóvenes que las mantenidas con restricciones<br />

energéticas en la dieta. 23,49,50 En la actualidad 3,4,41<br />

se pue<strong>de</strong> utilizar menor nivel <strong>de</strong> energía en la<br />

ración que como antiguamente se hacía 45,51 para<br />

obtener porcentajes aceptables <strong>de</strong> vaquillas<br />

púberes antes <strong>de</strong> la temporada <strong>de</strong> montas. Esto se<br />

<strong>de</strong>be al avance genético (ver más a<strong>de</strong>lante),<br />

antiguamente se procuraba <strong>de</strong>l 60 al 65% <strong>de</strong>l peso<br />

adulto en el animal al inicio <strong>de</strong> la temporada <strong>de</strong><br />

montas, 52 con el fin <strong>de</strong> asegurar la pubertad y<br />

porcentajes aceptables <strong>de</strong> gestación; actualmente<br />

las vaquillas presentan la pubertad a menor edad y<br />

peso, 53 lo cual permite disminuir la energía en la<br />

ración y como consecuencia reducir los costos <strong>de</strong><br />

alimentación. El incremento <strong>de</strong>l nivel <strong>de</strong> energía<br />

en la ración pue<strong>de</strong> inducir la pubertad precoz:<br />

inicio <strong>de</strong> la función ovárica cíclica en animales<br />

jóvenes, menores a 300 días <strong>de</strong> edad. 11,54,55<br />

La relación entre nutrición y<br />

reproducción probablemente se realice a través <strong>de</strong><br />

productos <strong>de</strong>l eje somatotrópico. En la vaca, la<br />

hormona <strong>de</strong>l crecimiento (GH) promueve la<br />

secreción hepática <strong>de</strong>l factor <strong>de</strong> crecimiento<br />

parecido a la insulina tipo I (IGF-I); 56-59 el cual<br />

pue<strong>de</strong> influir sobre la secreción <strong>de</strong> GnRH en las<br />

células <strong>de</strong>l hipotálamo 60-62 y LH en la hipófisis; 63-<br />

65 también incrementa la síntesis <strong>de</strong> receptores<br />

para gonadotropinas en las células ováricas y<br />

como consecuencia se aumenta la producción <strong>de</strong><br />

esteroi<strong>de</strong>s, 66-72 entre otras activida<strong>de</strong>s.<br />

Las vaquillas mejor alimentadas<br />

presentan mayor incremento <strong>de</strong> peso corporal y<br />

elevada concentración sanguínea <strong>de</strong>l IGF-I. 73 La<br />

presencia <strong>de</strong> este factor se ha relacionado con el<br />

aumento en la secreción <strong>de</strong> LH y la subsiguiente<br />

presentación <strong>de</strong> la pubertad en animales más<br />

jóvenes que en aquellos alimentados con dietas <strong>de</strong><br />

menor calidad. 74-76 El aumento <strong>de</strong> peso se<br />

relaciona con mayor crecimiento folicular y<br />

aumento en la secreción <strong>de</strong> estradiol en los<br />

folículos estrogénicamente activos. 23,55,77 En<br />

trabajos realizados in vitro, el IGF-I aumenta la<br />

función <strong>de</strong> la GnRH sobre las células <strong>de</strong>l lóbulo<br />

anterior <strong>de</strong> la hipófisis y las activida<strong>de</strong>s <strong>de</strong> las<br />

gonadotropinas sobre los ovarios. 65 La función <strong>de</strong><br />

GH en la vaquilla se ha <strong>de</strong>mostrado por medio <strong>de</strong><br />

la inmunización contra la hormona liberadora <strong>de</strong><br />

la hormona <strong>de</strong>l crecimiento; este tratamiento<br />

3

A Larios-Jiménez et al<br />

retarda la pubertad 78,79 y disminuye el crecimiento<br />

folicular. 80<br />

Los productos utilizados para<br />

incrementar la eficiencia alimenticia y por<br />

consiguiente el estrado nutricional <strong>de</strong>l animal,<br />

como los ionóforos, 81 reducen la edad a la<br />

pubertad en vaquillas. 82,83 Los ionóforos<br />

modifican la función metabólica y la proporción<br />

<strong>de</strong> ciertos microorganismos; 84 actúan sobre<br />

bacterias Gram positivas 85 y algunas Gram<br />

negativas; 86 también pue<strong>de</strong>n disminuir el<br />

porcentaje <strong>de</strong> protozoarios 84 y algunos hongos, 87<br />

bajo condiciones experimentales. El cambio en el<br />

ecosistema ruminal conduce al incremento <strong>de</strong>l<br />

ácido propiónico y la reducción <strong>de</strong> los ácidos<br />

ácetico y butírico, entre otras activida<strong>de</strong>s. 88-91 El<br />

incremento <strong>de</strong>l ácido propiónico en el rumen<br />

mejora la gluconeogénesis 84 e incrementa la<br />

capacidad <strong>de</strong> GnRH para secretar LH, 92,93 así<br />

como la influencia <strong>de</strong>l estradiol sobre la secreción<br />

preovulatoria <strong>de</strong> LH. 94 La infusión <strong>de</strong> propionato<br />

en el abomaso <strong>de</strong> vaquillas reduce la edad a la<br />

pubertad. 92<br />

Raza <strong>de</strong>l animal<br />

La edad y peso a la pubertad también<br />

varían <strong>de</strong> acuerdo a la raza <strong>de</strong>l animal. Las<br />

vaquillas <strong>de</strong> razas europeas generalmente alcanzan<br />

la pubertad más jóvenes y con menor peso que las<br />

Cebú, mestizas <strong>de</strong> Cebú o razas provenientes <strong>de</strong><br />

cruzamientos con Cebú; también se registran<br />

diferencias entre las razas europeas; las vaquillas<br />

Angus, por ejemplo, presentan la pubertad más<br />

jóvenes y con menor peso corporal que las<br />

Hereford. 46 En otros estudios también se han<br />

encontrado variaciones en la edad a la pubertad<br />

con relación a la raza <strong>de</strong>l animal. 3,43,95-98<br />

Las vaquillas pertenecientes a razas con<br />

mayor habilidad para la producción <strong>de</strong> leche<br />

presentan la pubertad con anterioridad a las<br />

hembras <strong>de</strong> otras razas. 99-101 Las vaquillas<br />

<strong>de</strong>scendientes <strong>de</strong> toros con mayor circunferencia<br />

escrotal 99,102 también alcanzan más jóvenes la<br />

pubertad. Por lo tanto, en el ganado bovino<br />

productor <strong>de</strong> carne se <strong>de</strong>bería esperar variaciones<br />

en la edad a la pubertad con relación a la<br />

información genética <strong>de</strong>l animal, más precoces las<br />

<strong>de</strong>scendientes <strong>de</strong> toros con mayor circunferencia<br />

escrotal y las portadoras <strong>de</strong> genes <strong>de</strong> razas con<br />

habilidad en la producción <strong>de</strong> leche; así como la<br />

presión <strong>de</strong> selección realizada para esta<br />

característica. Las vaquillas antiguamente<br />

presentaban la pubertad e iniciaban la temporada<br />

<strong>de</strong> montas con el 60 – 65 % <strong>de</strong> su esperado peso<br />

vivo, 103 en la actualidad algunas hembras lo hacen<br />

con el 50%. 104<br />

Época <strong>de</strong>l año<br />

El ganado bovino se reproduce<br />

continuamente, no presenta estacionalidad<br />

reproductiva. Sin embargo, la época <strong>de</strong>l año pue<strong>de</strong><br />

influir sobre el comportamiento reproductivo <strong>de</strong>l<br />

animal, 2,105-108 en este caso se analizará el período<br />

<strong>de</strong>l nacimiento a la pubertad. 108-110<br />

Se han encontrado variaciones en el<br />

comportamiento reproductivo a través <strong>de</strong>l año en<br />

las vaquillas. El ganado Brahman aumenta la<br />

inci<strong>de</strong>ncia <strong>de</strong> hembras púberes en la primavera,<br />

alcanza su máximo valor en el verano y disminuye<br />

durante el otoño; 47 probablemente en este trabajo<br />

se presentó el efecto <strong>de</strong> varios factores <strong>de</strong>l<br />

ambiente como disponibilidad <strong>de</strong> alimento,<br />

temperatura, humedad y fotoperiodo, y no<br />

exclusivamente el fotoperiodo como suce<strong>de</strong> en las<br />

especies con reproducción estacional. Los<br />

equinos, 111 ovinos 112 y caprinos, 113 entre otras<br />

especies <strong>de</strong> comportamiento reproductivo<br />

estacional, atien<strong>de</strong>n al fotoperiodo para presentar<br />

la pubertad.<br />

En el ganado bovino productor <strong>de</strong> carne,<br />

en el caso <strong>de</strong> mantener huella <strong>de</strong> la estacionalidad<br />

reproductiva <strong>de</strong>be presentar la pubertad bajo las<br />

condiciones <strong>de</strong>l fotoperiodo prevalecientes<br />

alre<strong>de</strong>dor <strong>de</strong>l equinoccio <strong>de</strong> otoño para permitir la<br />

concepción en otoño y se presenten los partos en<br />

la primavera <strong>de</strong>l año siguiente; la duración <strong>de</strong> la<br />

gestación en los bovinos es <strong>de</strong> 9 meses. 114 Las<br />

especies con reproducción estacional presentan<br />

sus partos en primavera, lo cual asegura mayor<br />

supervivencia <strong>de</strong> su <strong>de</strong>scen<strong>de</strong>ncia. 115 La<br />

frecuencia <strong>de</strong> pulsos y la concentración <strong>de</strong> LH son<br />

mayores alre<strong>de</strong>dor <strong>de</strong>l equinoccio <strong>de</strong> otoño en<br />

becerras recién nacidas, in<strong>de</strong>pendientemente <strong>de</strong>l<br />

mes <strong>de</strong> su nacimiento. 116 La edad a la pubertad es<br />

menor en las vaquillas nacidas en otoño en<br />

comparación con las nacidas en primavera <strong>de</strong>l<br />

mismo año, bajo condiciones <strong>de</strong> fotoperiodo<br />

natural; 30,110 las primeras reciben más jóvenes<br />

(alre<strong>de</strong>dor <strong>de</strong> 1 año <strong>de</strong> edad) la influencia <strong>de</strong>l<br />

fotoperiodo correspondiente al equinoccio <strong>de</strong><br />

otoño que las nacidas en primavera (alre<strong>de</strong>dor <strong>de</strong><br />

17 meses <strong>de</strong> edad). La edad a la pubertad también<br />

se reduce en las vaquillas mantenidas en cámaras<br />

<strong>de</strong> fotoperiodo con horas luz adicionales al<br />

fotoperiodo natural <strong>de</strong> otoño e invierno 109,110 y se<br />

retrasa con la reducción <strong>de</strong> la luminosidad. 110 La<br />

4

Eficiencia reproductiva en el ganado bovino productor <strong>de</strong> carne<br />

disminución <strong>de</strong> las horas luz <strong>de</strong>l día <strong>de</strong>mora la<br />

edad a la pubertad 95 y aumenta la inci<strong>de</strong>ncia <strong>de</strong><br />

anestro en vaquillas púberes. 117 El conjunto <strong>de</strong><br />

resultados anteriores indica variaciones en la edad<br />

a la pubertad con relación al fotoperiodo en las<br />

vaquillas productas <strong>de</strong> carne, con ten<strong>de</strong>ncia a<br />

presentar la pubertad alre<strong>de</strong>dor <strong>de</strong>l equinoccio <strong>de</strong><br />

otoño.<br />

Otra evi<strong>de</strong>ncia <strong>de</strong> la influencia <strong>de</strong>l<br />

fotoperiodo sobre la edad a la pubertad en la<br />

vaquilla productora <strong>de</strong> carne se recoge <strong>de</strong> un<br />

estudio realizado con aplicación <strong>de</strong> implantes <strong>de</strong><br />

melatonina, alre<strong>de</strong>dor <strong>de</strong>l solsticio <strong>de</strong> verano,<br />

durante 5 semanas. 118 La melatonina se produce<br />

en la glándula pineal 119 y es la hormona encargada<br />

<strong>de</strong> traducir el fotoperiodo en una señal<br />

hormonal. 120 El tratamiento aumentó el número <strong>de</strong><br />

vaquillas púberes en el año siguiente al<br />

tratamiento. 118<br />

Presencia <strong>de</strong>l macho<br />

La presencia <strong>de</strong>l macho sexualmente<br />

activo también pue<strong>de</strong> influir sobre la edad a la<br />

pubertad en vaquillas con crecimiento elevado y<br />

mo<strong>de</strong>rado, particularmente en las <strong>de</strong> mayor<br />

crecimiento; la influencia <strong>de</strong>l toro se incrementa<br />

conforme aumenta la tasa <strong>de</strong> crecimiento <strong>de</strong> las<br />

hembras; 48 lo mismo suce<strong>de</strong> con la infusión <strong>de</strong><br />

orina <strong>de</strong>l toro en la cavidad nasal <strong>de</strong> las<br />

vaquillas. 121 Resultados similares han encontrado<br />

otros autores en animales <strong>de</strong> diferente grupo<br />

genético. 122 PRIMERA CONCEPCIÓN<br />

La reducción <strong>de</strong> la edad a la pubertad en las<br />

vaquillas productoras <strong>de</strong> carne podría ser<br />

importante para incrementar su eficiencia<br />

reproductiva, la fertilidad se incrementa conforme<br />

transcurren los ciclos estrales, el 78% conciben al<br />

tercer estro y el 57% lo hacen en el celo<br />

puberal. 123 Lo mismo se ha encontrado en estudios<br />

realizados con transferencia embrionaria, la<br />

concepción es más elevada en transferencias<br />

realizadas en el tercer ciclo que en el puberal. 124<br />

Por lo tanto, edad más joven a la pubertad<br />

incrementa la posibilidad <strong>de</strong> concebir al inicio <strong>de</strong><br />

la temporada <strong>de</strong>stinada para las montas, entre más<br />

jóvenes a la pubertad mayor cantidad <strong>de</strong> ciclos<br />

estrales antes <strong>de</strong>l inicio <strong>de</strong> la temporada <strong>de</strong><br />

montas. El 89.8% y el 77.9% <strong>de</strong> las vaquillas<br />

concibieron en un estudio don<strong>de</strong> iniciaron la<br />

temporada <strong>de</strong> montas con el 58% y 51% <strong>de</strong>l peso<br />

adulto, respectivamente; el incremento en la<br />

duración <strong>de</strong> esta temporada <strong>de</strong> 45 a 60 días<br />

aumentó el porcentaje <strong>de</strong> concepción a 87.2 en las<br />

vaquillas con menor peso corporal; la mayoría <strong>de</strong><br />

las vaquillas menos pesadas que no concibieron<br />

(78.9%) permanecían en el período prepuberal al<br />

inicio <strong>de</strong> la temporada <strong>de</strong> montas, no habían<br />

presentado la pubertad. 104<br />

Cuadro 1. Raza predominante y edad promedio al primer parto en vaquillas mantenidas en pastoreo<br />

pertenecientes a 10 explotaciones <strong>de</strong> ganado bovino productor <strong>de</strong> carne 6<br />

Explotación Raza predominante Edad promedio al primer parto<br />

(días)<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

7<br />

8<br />

9<br />

10<br />

Beefmaster<br />

Angus x Cebú<br />

Simental<br />

Charolais<br />

Gelbvieh<br />

Charolais<br />

Suizo x Charolais<br />

Angus x Suizo<br />

Charolais<br />

Angus<br />

804.26<br />

876.14<br />

802.23<br />

1324.49<br />

1065.06<br />

806.88<br />

716.03<br />

742.48<br />

884.10<br />

5

En otros estudios, sin embargo, no se ha<br />

observado la ten<strong>de</strong>ncia discutida en el párrafo<br />

anterior; las vaquillas <strong>de</strong> mayor aumento <strong>de</strong> peso<br />

durante el período prepuberal han presentado más<br />

jóvenes la pubertad, pero la concepción a la<br />

misma edad que hembras con menor<br />

incremento; 3,4 lo mismo se ha observado en las<br />

vaquillas con elevada y mo<strong>de</strong>rada ganancia <strong>de</strong><br />

peso y la presencia <strong>de</strong>l macho para inducir la<br />

pubertad. 48 Las diferencias entre los estudios<br />

citados probablemente se <strong>de</strong>ba al peso <strong>de</strong> los<br />

animales en el momento <strong>de</strong> iniciar la temporada<br />

<strong>de</strong> montas; en algunos estudios las vaquillas se<br />

han alimentado con raciones para baja ganancia <strong>de</strong><br />

peso durante las dos terceras partes <strong>de</strong>l período<br />

prepuberal y en la última con raciones para mayor<br />

aumento; bajo estas condiciones los animales<br />

pue<strong>de</strong>n presentar crecimiento compensatorio y<br />

llegar en la temporada <strong>de</strong> montas con buen estado<br />

nutricional que facilite la concepción. 4 En otros<br />

estudios, los animales se han alimentado con<br />

raciones <strong>de</strong> mo<strong>de</strong>rada reducción en el contenido<br />

<strong>de</strong> energía, lo cual conduce a ligera disminución<br />

<strong>de</strong>l peso; bajo esta situación las vaquillas pue<strong>de</strong>n<br />

retrasar la pubertad 3 o la presentan a la misma<br />

edad que las compañeras <strong>de</strong> mayor ganancia <strong>de</strong><br />

peso. 41 En todos los casos anteriores, se disminuye<br />

el costo <strong>de</strong> las raciones y se ahorran recursos<br />

<strong>de</strong>stinados para la alimentación.<br />

PRIMER PARTO<br />

Con base en la información <strong>de</strong>splegada, las<br />

vaquillas con el manejo citado <strong>de</strong>ben presentar su<br />

primer parto a los dos años <strong>de</strong> edad. Sin embargo,<br />

los sistemas <strong>de</strong> producción en algunos lugares se<br />

basan en el pastoreo <strong>de</strong> los animales y<br />

complemento alimenticio en la temporada <strong>de</strong><br />

sequía; <strong>de</strong> esta manera se ha mantenido la<br />

rentabilidad <strong>de</strong> las empresas <strong>de</strong>dicadas a la<br />

explotación <strong>de</strong>l ganado bovino productor <strong>de</strong> carne.<br />

En la Unidad Académica <strong>de</strong> Medicina <strong>Veterinaria</strong><br />

y Zootecnia <strong>de</strong> la <strong>Universidad</strong> Autónoma <strong>de</strong><br />

<strong>Zacatecas</strong> se está evaluando el comportamiento<br />

reproductivo <strong>de</strong>l ganado bovino en pastoreo, en<br />

uno <strong>de</strong> estos estudios 6 se encontró el primer parto<br />

a 987.8 días <strong>de</strong> edad, en vaquillas <strong>de</strong>10 hatos y <strong>de</strong><br />

diferente grupo genético; los animales en este<br />

estudio se fecundaron por medio <strong>de</strong> monta natural<br />

y la selección <strong>de</strong> los toros utilizados para este fin<br />

no se realizó con base en su tamaño testicular. Por<br />

lo tanto, el estudio se llevó a cabo en vaquillas sin<br />

aptitu<strong>de</strong>s para edad joven a la pubertad. Los<br />

<strong>de</strong>talles <strong>de</strong> esta información se pue<strong>de</strong>n observar en<br />

el Cuadro 1.<br />

REFERENCIAS<br />

1. Lesmeister JL, Burfening PJ, Blackwell<br />

RL. Date of first calving in beef cows<br />

and subsequent calf production. J Anim<br />

Sci 1973; 36: 1-6.<br />

2. Escobar FJ, Fernán<strong>de</strong>z-Baca S, Galina<br />

CS, Berruecos JM, Saltiel CA. Estudio<br />

<strong>de</strong>l intervalo entre partos en bovinos<br />

productores <strong>de</strong> carne en una explotación<br />

<strong>de</strong>l altiplano y otra en la zona tropical<br />

húmeda. Vet Méx 1982; 13: 53-60.<br />

3. Freetly HC, Cundiff LV. Postweaning<br />

growth and reproduction characteristics<br />

of heifers sired by bulls of seven breeds<br />

and raised on different levels of nutrition.<br />

J Anim Sci 1997; 75: 2841-2851.<br />

4. Lynch JM, Lamb GC, Miller BL, Brandt<br />

RT Jr, Cochran RC, Minton JE. Influence<br />

of timing of gain on growth and<br />

reproductive performance of beef<br />

replacement heifers. J Anim Sci 1997;<br />

75: 1715-1722.<br />

5. Funston RN, Deutscher GH. Comparison<br />

of target breeding weight and breeding<br />

date for replacement beef heifers and<br />

effects on subsequent reproduction and<br />

calf performance. J Anim Sci 2004; 82:<br />

3094-3099.<br />

6. Larios-Jiménez A, Flores-Sandoval F,<br />

Escobar-Medina FJ, <strong>de</strong> la Colina-Flores<br />

F. Eficiencia reproductiva <strong>de</strong>l ganado<br />

bovino productor <strong>de</strong> carne en pastoreo.<br />

Vet Zac <strong>2007</strong>; 3:<br />

7. Mosley WM, Dunn TG, Kaltenbach CC,<br />

Short RE, Staigmiller RB. Negative<br />

feedback control on luteinizing hormone<br />

secretion in prepubertal beef heifers at 60<br />

and 200 days of age. J Anim Sci 1984;<br />

58: 145-150.<br />

8. An<strong>de</strong>rson WJ, Forrest DW, Schulze AL,<br />

Kraemer DC, Bowen MJ, Harms PG.<br />

Ovarian inhibition of pulsatile luteinizing<br />

hormone secretion in prepubertal<br />

Holstein heifers. Domest Anim Endocrol<br />

1985; 2: 85-91.<br />

9. An<strong>de</strong>rson WJ, Forrest DW, Goff BA,<br />

Shaikh AA, Harms PG. Ontogeny of<br />

ovarian inhibition of pulsatile luteinizing<br />

hormone secretion in postnatal Hostein<br />

6

Eficiencia reproductiva en el ganado bovino productor <strong>de</strong> carne<br />

heifers. Domest Anim Endocrinol 1986;<br />

3: 107-116.<br />

10. Dodson SE, McLeord BJ, Haresing W,<br />

Peters AR, Lamming GE, Das D.<br />

Ovarian control of gonadotrophin<br />

secretion in the prepubertal heifer. Anim<br />

Reprod Sci 1989; 21: 1-10.<br />

11. Gasser CL, Bridges GA, Mussard ML,<br />

Grum DE, Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE, Day ML. Induction<br />

of precocious puberty in heifers III.:<br />

hastened reduction of estradiol negative<br />

feedback on secretion of luteinizing<br />

hormone. J Anim Sci 2006; 84: 2050-<br />

2056.<br />

12. Kiser TE, Kraeling RR, Rampacek GB,<br />

Landmeier BJ, Caudle AB, Champman<br />

JD. Luteinizing hormone secretion before<br />

and after ovariectomy in prepubertal and<br />

pubertal beef heifers. J Anim Sci 1981;<br />

53: 1545-1550.<br />

13. Day ML, Imakawa K, Garcia-Win<strong>de</strong>r M,<br />

Zalesky DD, Schanabacher BD, Kittok<br />

RJ, Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE. Endocrine mechanism of<br />

puberty in heifers: estradiol negative<br />

feedback regulation on luteinizing<br />

hormone secretion. Biol Reprod 1984;<br />

31: 332-341.<br />

14. Evans AC, Currie WD, Rawlings NC.<br />

Effects of naloxone on circulating<br />

gonadotropin concentrations in<br />

prepuberal heifers. J Reprod Fertil 1992;<br />

96: 847-855.<br />

15. Dodson SE, McLeod BJ, Haresing W,<br />

Peters AR, Lamming GE. Endocrine<br />

changes from birth to puberty in the<br />

heifer. J Reprod Fertil 1988; 82: 527-538.<br />

16. Evans AC, Adams GP, Rawlings NC.<br />

Follicular and hormonal <strong>de</strong>velopment in<br />

prepubertal heifers from 2 to 36 weeks of<br />

age. J Reprod Fertil 1994; 102: 463-470.<br />

17. Nakada K, Moriyoshi M, Nakao T,<br />

Watanabe G, Taya K. Changes in<br />

concentration of plasma immunoreactive<br />

follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing<br />

hormone, estradiol-17 , testosterone,<br />

progesterone, and inhibin in heifers from<br />

birth to puberty. Domest Anim<br />

Endocrinol 2000; 18: 57-69.<br />

18. Erickson BH. Development and<br />

senescence of the postnatal bovine ovary.<br />

J Anim Sci 1966; 25: 800-805.<br />

19. Desjardins C, Hafs HD. Levels of<br />

pituitary FSH and LH in heifers from<br />

birth through puberty. J Anim Sci 1968;<br />

27: 472-477.<br />

20. Honaramooz A, Aravindakshan J,<br />

Chandolia RK, Beard AP, Bartlewski<br />

PM, Pierson RA, Rawlings NC.<br />

Ultrasonographic evaluation of the prepubertal<br />

<strong>de</strong>velopment of the reproductive<br />

tract in beef heifers. Anim Reprod Sci<br />

2004; 80: 15-29.<br />

21. Schams D, Schallenberger E, Gombe S,<br />

Karg H. Endocrine patterns associated<br />

with puberty in male and female cattle. J<br />

Reprod Fertil 1981; 30 (Suppl): 103-110.<br />

22. Day ML, Imakura K, Wolfe PL, Kittok<br />

RJ, Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE. Endocrine mechanisms of<br />

puberty in heifers: role of hypothalamopituitary<br />

estradiol receptors in the<br />

negative feedback of estradiol on<br />

luteinizing hormone secretion. Biol<br />

Reprod 1987; 37: 1054-1065.<br />

23. Bergfeld EGM, Kojima FN, Cupp AS,<br />

Wehrman ME, Peters KE, Garcia-Win<strong>de</strong>r<br />

M, Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE. Ovarian follicular<br />

<strong>de</strong>velopment in prepubertal heifers is<br />

influenced by level of dietary energy<br />

intake. Biol Reprod 1994; 51: 1051-<br />

1057.<br />

24. Evans AC, Adams GP, Rawlings NC.<br />

Endocrine and follicular changes leading<br />

up to the first ovulation in prepubertal<br />

heifers. J Reprod Fertil 1994; 100: 187-<br />

194.<br />

25. Melvin EJ, Lindsey BR, Quintal-Franco<br />

J, Zanella E, Fike KE, Van Tassell CP,<br />

Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE. Estradiol, luteinizing<br />

hormone, and follicular stimulating<br />

hormone during waves of ovarian<br />

follicular <strong>de</strong>velopment in prepubertal<br />

cattle. Biol Reprod 1999; 60: 405-412.<br />

26. Hopper HW, Silcox RW, Byerley DJ,<br />

Kiser TE. Follicular <strong>de</strong>velopment in<br />

prepubertal heifers. Anim Reprod Sci<br />

1993; 31: 7-12.<br />

27. Adams GP, Evans AC, Rawling NC.<br />

Follicular waves and circulating<br />

gonadotropins in 8-old-month<br />

prepubertal heifers. J Reprod Fertil 1994;<br />

100: 27-33.<br />

28. Pierson RA, Ginther OJ. Ultrasonic<br />

imaging of the ovaries and uterus in<br />

cattle. Theriogenology 1988; 29: 21-38.<br />

29. Adams GP, Matteri RL, Kastelic JP, Ko<br />

JCH, Ginther OJ. Association between<br />

surges of follicle-stimulating hormone<br />

7

A Larios-Jiménez et al<br />

and the emergence of follicular waves in<br />

heifers. J Reprod Fertil 1992; 94: 177-<br />

188.<br />

30. Schillo KK, Dierschke DJ, Hauser ER.<br />

Regulation of luteinizing hormone<br />

secretion in prepubertal heifers:<br />

Increased threshold to negative feedback<br />

action of estradiol. J Anim Sci 1982; 54:<br />

325-336.<br />

31. Wolfe MW, Stumpf TT, Roberson MS,<br />

Wolfe PL, Kittok RJ. Estradiol<br />

influences on pattern of gonadotropin<br />

secretion in bovine males during the<br />

period of changes feedback in agematched<br />

females. Biol Reprod 1989; 41:<br />

626-634.<br />

32. Kurz SG, Dyer RM, Hu Y, Wright MD,<br />

Day ML. Regulation of luteinizing<br />

hormone secretion in prepubertal heifers<br />

fed an energy-<strong>de</strong>ficiency diet. Biol<br />

Reprod 1990; 43: 450-456.<br />

33. Day ML, An<strong>de</strong>rson LH. Current concepts<br />

on the control of puberty in cattle. J<br />

Anim Sci 1998; 76 (Suppl 3): 1-15.<br />

34. Day ML, Imakawa K, Zalesky DD,<br />

Kittok RJ, Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE. Effects of<br />

restriction of dietary energy intake during<br />

the prepubertal period on secretion of<br />

luteinizing hormone and responsiveness<br />

of the pituitary to luteinizing hormonereleasing<br />

hormone in heifers. J Anim Sci<br />

1986; 62: 1641-1648.<br />

35. Day ML, Imakawa K, Garcia-Win<strong>de</strong>r M,<br />

Kittok RJ, Schanbacher BD, Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE.<br />

Influence of prepubertal ovariectomy and<br />

estradiol replacement therapy on<br />

secretion of luteinizing hormone before<br />

and after pubertal age in heifers. Dom<br />

Anim Endocr 1986; 3: 17-25.<br />

36. Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE, Garcia-Win<strong>de</strong>r M, Imakawa<br />

K, Day ML, Zalesky DD, D’Occhio ML,<br />

Kittok RJ, Schanbacher BD. Influence of<br />

different estrogen doses on concentration<br />

of serum LH acute and chronic<br />

ovariectomized cow. J Anim Sci 1983;<br />

57 (Suppl 1): 350.<br />

37. Berardinelli JG, Dailey RA, Butcher RL,<br />

Inskeep EK. Source of progesterone prior<br />

to puberty in beef heifers. J Anim Sci<br />

1979; 1276-1280.<br />

38. Kesner JS, Padmanaghan V, Convey EM.<br />

Estradiol induces and progesterone<br />

inhibits the preovulatory surge of<br />

luteinizing hormone and follicle<br />

stimulating hormone in heifers. Biol<br />

Reprod 1982; 26: 571-578.<br />

39. Swason LV, McCarthy SK. Estradiol<br />

treatment and luteinizing hormone (LH)<br />

response of prepubertal Hostein heifers.<br />

Biol Reprod 1978; 18: 475-480.<br />

40. Rasby RJ, Day ML, Johnson SK, Kin<strong>de</strong>r<br />

JE, Lynch JM, Short RE, Wettemann RP,<br />

Hafs HS. Luteal function and estrus in<br />

peripubertal beef heifers treated with an<br />

intravaginal progesterone releasing<br />

<strong>de</strong>vice with or without of subsequent<br />

injection of estradiol. Theriogenology<br />

1998; 50: 55-63.<br />

41. Buskirk DD, Faulkner DB, Ireland FA.<br />

Increased postweaning gain of beef<br />

heifers enhances fertility and milk<br />

production. J Anim Sci 1995; 73: 937-<br />

946.<br />

42. Imakawa K, Day ML, Zalesky DD,<br />

Clutter A, Kittok RJ, Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE. Effects<br />

of 17-estradiol in diets varying in<br />

energy on secretion of luteinizing<br />

hormone in beef heifers. J Anim Sci<br />

1987; 64: 805-815.<br />

43. Ferrell CL. Effects of postweaning rate<br />

of gain on onset of puberty and<br />

productive performance of heifers of<br />

different breeds. J Anim Sci 1982; 55:<br />

1272-1283.<br />

44. Wiltbank JN, Kasson CW, Ingalls JE.<br />

Puberty in crossbred and straightbred<br />

beef heifers on two levels of feed. J<br />

Anim Sci 1969; 29: 602-605.<br />

45. Wiltbank JN, Roberts S, Nix J, Row<strong>de</strong>n<br />

L. Reproductive performance and<br />

profitability of heifers fed to weigh 272<br />

or 318 Kg at the start of the first breeding<br />

season. J Anim Sci 1985; 60: 25-34.<br />

46. Wiltbank JN, Sptizer JC. Investigaciones<br />

recientes sobre la reproducción regulada<br />

en el ganado bovino. Rev Mundial Zoot<br />

1978; 27: 30-35.<br />

47. Please D, Warnick AC, Koger M.<br />

Reproductive behavior of Bos indicus<br />

females in a subtropical environment. I.<br />

Puberty and ovulation frequency of<br />

Brahman and Brahman x British heifers.<br />

J Anim Sci 1968; 27: 94-100.<br />

48. Robertson MS, Wolfe MW, Stumpf TT,<br />

Werth LA, Cupp AS, Kojima N, Wokfe<br />

PL, Kittok RJ, Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE. Influence of<br />

growth rate and expose to bulls on age at<br />

8

Eficiencia reproductiva en el ganado bovino productor <strong>de</strong> carne<br />

puberty in beef heifers. J Anim Sci 1991;<br />

69: 2092-2098.<br />

49. Day ML, Imakawa K, Zalesky DD,<br />

Kittok RJ, Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE. Effects of<br />

restriction of dietary energy intake during<br />

the prepubertal period on secretion of<br />

luteinizing hormone and responsiveness<br />

of the pituitary to luteinizing hormonereleasing<br />

hormone in heifers. J Anim Sci<br />

1986; 62: 1641-1648.<br />

50. Romano MA, Barnabe VH, Kastelic JP,<br />

<strong>de</strong> Oliveira CA, Romano RM. Follicular<br />

dynamics in heifers during prepubertal<br />

and pubertal period kept un<strong>de</strong>r two levels<br />

of dietary energy intake. Reprod Domest<br />

Anim <strong>2007</strong>; 42: 616-622.<br />

51. Short RE, Bellows RA. Relationships<br />

among weight gains, age at puberty and<br />

reproductive performance in heifers. J<br />

Anim Sci 1971; 32: 127-131.<br />

52. Patterson DJ, Corah LR, Berthour JR,<br />

Higgins JJ, Kiracofe GH, Stevenson JS.<br />

Evaluation of reproductive traits in Bos<br />

taurus and Bos indicus crossbred heifers:<br />

Relationship of age at puberty to length<br />

of the postpartum interval to estrus. J<br />

Anim Sci 1992; 70: 1994-1999.<br />

53. Roberts AJ, Grings EE, MacNeil MD,<br />

Waterman RC, Alexan<strong>de</strong>r LJ, Geary TW.<br />

Reproductive performance of heifers<br />

offered ad libitum or restricted access to<br />

feed for a 140-d period after weaning.<br />

Western Section of Animal Science<br />

Proceedings <strong>2007</strong>; 58: 255-258.<br />

54. Gasser CL, Grum DE, Mussard ML,<br />

Fluhart FL, Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE, Day ML.<br />

Induction of precocious puberty in<br />

heifers I: enhanced secretion of<br />

luteinizing hormone. J Anim Sci 2006;<br />

84: 2035-2041.<br />

55. Gasser CL, Burke CR, Mussard ML,<br />

Behlke EJ, Grum DE, Kin<strong>de</strong>r JE, Day<br />

ML. Induction of precocious puberty in<br />

heifers II: advanced ovarian follicular<br />

<strong>de</strong>velopment. J Anim Sci 2006; 84:<br />

2042-2049.<br />

56. McGrath MF, Collier RJ, Clemmons DR,<br />

Busby WH, Sweeny CA, Krivi GG. The<br />

direct in vitro effect of insulin like<br />

growth factors (IGFs) on normal bovine<br />

mammary cell proliferation and<br />

production of IGF binding proteins.<br />

Endocrinology 1991; 129: 671-678.<br />

57. Cohick WS, Turner JD. Regulation of<br />

IGF binding proteins synthesis by bovine<br />

mammary epithelial cell line. J<br />

Endocrinol 1998; 157: 327-336.<br />

58. Liu JL, LeRoith D. Insulin-like growth<br />

factor I is essential for postnatal growth<br />

in response to growth hormone.<br />

Endocrinology 1999; 140: 5178-5184.<br />

59. Weber MS, Purup S, Vestergaard M,<br />

Ellis SE, Scn<strong>de</strong>rgard-An<strong>de</strong>rsen J, Akers<br />

RM, Sejrsen K. Contribution of insulinlike<br />

growth factor (IGF)-I and IGFbinding<br />

protein-3 to mitogenic activity in<br />

bovine mammary extracts and serum. J<br />

Endocrinol 1999; 161: 365-373.<br />

60. Zhen S, Zakaira M, Wolfe A, Radovick<br />

S. Regulation of gonadotropin-releasing<br />

hormone (GnRH) gene expression by<br />

insulin-like growth factor I in a cultured<br />

GnRH-expression neuronal cell line. Mol<br />

Endocrinol 1997; 11: 1145-1155.<br />

61. Longo KM, Sun Y, Gore AC. Insulinlike<br />

growth factor-I effects on<br />

gonadotropin-releasing hormone<br />

biosynthesis in GT1-7 cells.<br />

Endocrinology 1998; 139: 1125-1132.<br />

62. An<strong>de</strong>rson RA, Zwain IH, Arroyo A,<br />

Mellon PL, Yen SCS. The insulin-like<br />

growth factor system in the GT1-7 GnRH<br />

neuronal cell line. Neuroendocrinol<br />

1999; 70: 353-359.<br />

63. Adam CL, Findlay PA, Moore HA.<br />

Effects of insulin-like growth factors-I on<br />

luteinizing hormone secretion in sheep.<br />

Anim Reprod Sci 1997; 50: 45-56.<br />

64. Adam CL, Gadd TS, Findlay PA, Wathes<br />

DC. IGF-I stimulation of luteinizing<br />

hormone secretion, IGF-binding proteins<br />

(IGFBPs) and expression of mRNAs for<br />

IGFs, IGF receptors and IGFBPs in ovine<br />

pituitary gland. Endocrinology 2000;<br />

166: 247-254.<br />

65. Hashizime T, Kumahara A, Fujino M,<br />

Okada K. Insulin-like growth factor I<br />

enhances gonadotropin-releasing<br />

hormone-stimulated luteinizing hormone<br />

release from bovine anterior pituitary<br />

cells. Anim Reprod Sci 2002; 70: 13-21.<br />

66. Spicer LJ, Alpizar E, Echternkamp SE.<br />

Effects of insulin, IGF-I, and<br />

gonadotropins on bovine granulosa cell<br />

proliferation, progesterone production,<br />

estradiol production, and (or) IGF-I<br />

9

A Larios-Jiménez et al<br />

production in vitro. J Anim Sci 1993; 71:<br />

1232-1241.<br />

67. Spicer. LJ, Echternkamp SE. The ovarian<br />

insulin and insulin like growth factor<br />

system with an emphasis on domestic<br />

animals. Domest Anim Endocrinol 1995;<br />

12: 223-245.<br />

68. Adashi EY. Growth factors and ovarian<br />

function: the IGF-I paradigm. Horm Res<br />

1994; 42: 44-48.<br />

69. Adashi EY. The IGF family and<br />

folliculogenesis. J Reprod Immunol<br />

1998; 39: 13-19.<br />

70. Gong JG, McBri<strong>de</strong> D, Bramley TA,<br />

Webb R. Effects of recombinant bovine<br />

somatotrophin, insulin-like growth<br />

factor-I and insulin on the proliferation of<br />

bovine granulose cells in vitro. J<br />

Endocrinol 1993; 139: 67-75.<br />

71. Guidice LC. Insulin-like growth factor<br />

and ovarian follicular <strong>de</strong>velopment.<br />

Endocrine Rev 1992; 13: 641-669.<br />

72. Lucy MC. Regulation of ovarian<br />

follicular growth by somatotropin and<br />

insulin-like growth factors in cattle. J<br />

Dairy Sci 2000; 83: 1635-1647.<br />

73. Radcliff RP, Van<strong>de</strong>Haar MJ, Kobayashi<br />

Y, Sharma BK, Tucker HA, Lucy MC.<br />

Effect of dietary energy and<br />

somatotropin on components of the<br />

somatotropic axis in Holstein herifers. J<br />

Dairy Sci 2004; 87: 1229-1235.<br />

74. Granger AL, Wyatt WE, Craig WM,<br />

Thompson DL Jr, Hembry FG. Effects of<br />

breed and wintering diet on growth,<br />

puberty and plasma concentration of<br />

growth hormone and insulin-like growth<br />

factor 1 in heifers. Domest Anim<br />

Endocrinol 1989; 6: 253-262.<br />

75. Yelich JV, Wetteman RP, Dolezal HG,<br />

Lusby KS, Bishop DK, Spicer LJ. Effects<br />

of growth rate on carcass composition<br />

and lipid partitioning at puberty and<br />

growth hormone, insulin-like growth<br />

factor I, insulin, and metabolites before<br />

puberty in beef heifers. J Anim Sci 1995;<br />

73: 2390-2405.<br />

76. Yelich JV, Wetteman RP, Marston TT,<br />

Spicer LJ. Luteinizing hormone, growth<br />

hormone, insulin like growth factor-I,<br />

insulin and metabolites before puberty in<br />

heifers fed to gain at two rates. Domest<br />

Anim Endocrinol 1996; 13: 325-338.<br />

77. Spicer LJ, Enright WJ, Murphy MG,<br />

Roche JF. Effect of dietary intake on<br />

concentration of insulin-like growth<br />

factor-I in plasma and follicular fluid,<br />

and ovarian function in heifers. Domest<br />

Anim Endocrinol 1991; 8: 431-437.<br />

78. Cohick WS, Armstrong JD, Whitacre<br />

MD, Lucy MC, Harvey RW, Campbell<br />

RM. Ovarian expression of insulin-like<br />

growth factor-I (IGF-I), IGF binding<br />

proteins, and growth hormone (GH)<br />

receptor in heifers actively immunized<br />

against GH-releasing factors. Endocrinol<br />

1996; 137: 1670-1677.<br />

79. Schoppee PD, Armstrong JD, Harvey<br />

MA, Whitacre MD, Felix A, Campbell<br />

RM. Immunization against growth<br />

hormone releasing factor or chronic feed<br />

restriction initiated at 3.5 months of age<br />

reduces ovarian response at 6 months of<br />

age and <strong>de</strong>lays onset of puberty in<br />

heifers. Biol Reprod 1996; 55: 87-98.<br />

80. Simpson RB, Armstrong JD, Harvey<br />

RW, Miller DC, Heimer EP, Campbell<br />

RM. Effect of active immunization<br />

against growth hormone-releasing factor<br />

on growth and onset of puberty in beef<br />

heifers. J Anim Sci 1991; 69: 4914-4924.<br />

81. Goodrich RD, Garrett JE, Gast DR,<br />

Kirick MA, Larson DA, Meiske JC.<br />

Influence of monensin on the<br />

performance of cattle. J Anim Sci 1984;<br />

58: 1484-1498.<br />

82. Mosley WM, McCartor MM, Ran<strong>de</strong>l RD.<br />

Effects of monensin on growth and<br />

reproductive performance of beef heifers.<br />

J Anim Sci 1977; 45: 961-968.<br />

83. Mosley WM, Dunn TG, Kaltenbach CC,<br />

Short RE, Staigmiller RB. Relationship<br />

of growth and puberty of beef heifers fed<br />

monensin. J Anim Sci 1982; 55: 357-362.<br />

84. Schelling GT. Monensin mo<strong>de</strong> of action<br />

in the rumen. J Anim Sci 1984; 58: 1518-<br />

1527.<br />

85. Russell JB, Strobel HJ. Effects of<br />

additives on in vitro ruminal<br />

fermentation: a comparasion of monensin<br />

and bacitracin, another gram-positive<br />

antibiotic. J Anim Sci 1988; 66: 552-558.<br />

86. Morehead MC, Dawson KA. Some<br />

growth and metabolic characteristics of<br />

monensin-resistant strains of Prevotella<br />

(Bacteroi<strong>de</strong>s) ruminicola. Appl Environ<br />

Microbol 1992; 58: 1617-1623.<br />

10

Eficiencia reproductiva en el ganado bovino productor <strong>de</strong> carne<br />

87. Cann IKO, Kobayashi Y, Onada A,<br />

Wakita M, Hoshino S. Effects of some<br />

ionophore antibiotics and polyoxins on<br />

the growth of anaerobic rumen fungi. J<br />

Appl Bacteriol 1993; 74: 127-133.<br />

88. Richardson LF, Raun AP, Potter EL,<br />

Cooley CO, Rathmacher RP. Effect of<br />

monensin in rumen fermentation in vivo<br />

and in vitro. J Anim Sci 1976; 43: 657-<br />

664.<br />

89. Davis GV. Effects of lasalocid sodium on<br />

the performance of finishing steers. J<br />

Anim Sci 1978; 47 (Suppl 1): 414.<br />

90. Bartley EE, Herod EL, Bechtle RM,<br />

Sapienza DA, Brent BE, Davidovich A.<br />

Effect of monensin or lasalocid, with and<br />

without niacin or amicloral, on rumen<br />

fermentation and feed efficiency. J Anim<br />

Sci 1979; 49: 1066-1075.<br />

91. Thonney ML, Hei<strong>de</strong> EK, Duhaime DJ,<br />

Hand RJ, Perosio DJ. Growth, feed<br />

efficiency and metabolite concentration<br />

of cattle fed high forage diets with<br />

lasalocid or monensin supplements. J<br />

Anim Sci 1981; 52: 427-433.<br />

92. Rutter LM, Ran<strong>de</strong>l RD, Schelling GT,<br />

Forrest DW. Effect of abomasal infusion<br />

of propionate on the GnRH-induced<br />

luteinizng hormone release in prepuberal<br />

heifers. J Anim Sci 1983; 56: 1167-1173.<br />

93. Ran<strong>de</strong>l RD. Rho<strong>de</strong>s RC III. The effect of<br />

dietary monensin on the luteinizing<br />

hormone response of prepubertal heifers<br />

given a multiple gonadotropin-releasing<br />

hormone challenge. J Anim Sci 1980; 51:<br />

925-931.<br />

94. Ran<strong>de</strong>l RD, Rutter LM, Rho<strong>de</strong>s RC III.<br />

Effect of monensin on the estrogeninduced<br />

LH surge in prepubetal heifers. J<br />

Anim Sci 1982; 54: 806-810.<br />

95. Grass JA, Hansen PJ, Rutledge JJ,<br />

Hauser ER. Genotype-environmental<br />

interactions on reproductive traits of<br />

bovine felames: I. Age at puberty as<br />

influenced by breed, breed of sire, dietary<br />

regimen and season. J Anim Sci 1982;<br />

55: 1441-1457.<br />

96. Gregory KE, Laster DB, Cundiff LV,<br />

Koch RM, Smith GM. Heterosis and<br />

breed maternal and transmitted effects in<br />

beef cattle. II. Growth and rate puberty in<br />

females. J Anim Sci 1978; 47: 1042-<br />

1053.<br />

97. Gregory KE, Laster DB, Cundiff LV,<br />

Smith GM, Koch RM. Characterization<br />

of biological types of cattle-cycle III: II.<br />

Growth rate and puberty in females. J<br />

Anim Sci 1979; 49: 461-471.<br />

98. Chenoweth PJ. Aspects of reproduction<br />

in female Bos indicus cattle: a review.<br />

Aust Vet J 1994; 71: 422-426.<br />

99. Martin LC, Brinks JS, Bourdin RM,<br />

Cundiff LV. Genetic effects on beef<br />

heifer puberty and subsequent<br />

reproduction. J Anim Sci 1992; 70: 4006-<br />

4017.<br />

100. Laster DB, Smith GM, Gregory KE.<br />

Characterization of biological type of<br />

cattle. IV. Postweaning growth and<br />

puberty of heifers. J Anim Sci 1976; 43:<br />

63-70.<br />

101. Laster DB, Smith GM, Cundiff LV,<br />

Gregory KE. Characterization of<br />

biological type of cattle (cycle II). II.<br />

Postweaning growth and puberty of<br />

heifers. J Anim Sci 1979; 48: 500-508.<br />

102. Morris CA, Baker RL, Cullen NG.<br />

Genetic correlations between pubertal<br />

traits in bulls and heifers. Livest Prod Sci<br />

1992; 31: 221-234.<br />

103. Patterson DJ, Perry RC, Kiracofe GH,<br />

Bellows RA, Staigmiller RB, Corah LR.<br />

Management consi<strong>de</strong>rations in heifer<br />

<strong>de</strong>velopment and puberty. J Anim Sci<br />

1992; 70: 4018-4035.<br />

104. Martin JL, Creighton KW, Musgrave JA,<br />

Klopfenstein TJ, Clark RT, Adams DC,<br />

Funston RN. Effect of prebreeding body<br />

weight or progestin exposure before<br />

breeding on beef heifer performance<br />

through the second breeding season. J<br />

Anim Sci 2008; 86: 451-459.<br />

105. King GJ, Macleod GK. Reproductive<br />

function in beef cows calving in the<br />

spring or fall. Anim Reprod Sci 1984; 6:<br />

255-266.<br />

106. Critser JK, Miller KF, Gunstt FC,<br />

Ginther OJ. Seasonal LH profile in<br />

ovariectomized cattle. Theriogenology<br />

1983; 19: 181-191.<br />

107. Critser JK, Lindstorm MJ, Hineshelwood<br />

MM, Hauser ER. Effect of photoperiod<br />

on LH, FSH and prolactin patterns in<br />

ovariectomized estradiol-treated heifers.<br />

J Reprod Fertil 1987; 79: 599-608.<br />

108. Schillo KK, Hall JB, Hileman SM.<br />

Effects of nutrition and season on the<br />

11

A Larios-Jiménez et al<br />

onset of puberty in the beef heifer. J<br />

Anim Sci 1992; 70: 3994-4005.<br />

109. Hansen PJ, Kamwanja LA, Hauser ER.<br />

Photoperiod infuences age at puberty of<br />

heifers. J Anim Sci 1983; 57: 985-992.<br />

110. Schillo KK, Hansen PJ, Kamwanja LA,<br />

Dierschke DJ, Hauser ER. Influence of<br />

season on sexual <strong>de</strong>velopment in heifers:<br />

age at puberty as related to growth and<br />

serum concentration of gonadotropins,<br />

prolactin, thyroxine and progesterone.<br />

Biol Reprod 1983; 28: 329-341.<br />

111. Brown-Douglas CG, Firth EC, Parkinson<br />

TJ, Fennessy PF. Onset of puberty in<br />

pasture-raised Throughbreeds born in<br />

southern hemisphere spring and autumn.<br />

Equine Vet J 2004; 36: 499-504.<br />

112. Foster DL. Puberty in sheep. In: Knobil<br />

E, Neil JD, editors. The Physiology or<br />

Reproduction. New York: Raven Press,<br />

1994: 411-451.<br />

113. Erario A, Escobar FJ, Rincón RM, <strong>de</strong> la<br />

Colina F, Meza C. Efecto <strong>de</strong>l fotoperiodo<br />

sobre la edad a la pubertad en la cabra.<br />

<strong>Revista</strong> Chapingo Serie Zonas Áridas<br />

2004; 155-158.<br />

114. An<strong>de</strong>rsen H, Plum M. Gestation length<br />

and birth weight in cattle and buffaloes: a<br />

review. J Dairy Sci 1965; 48: 1224-1235.<br />

115. Bronson FH, Hei<strong>de</strong>man PD. Seasonal<br />

regulation of reproduction in mammals.<br />

In: Knobil E, Neil JD, editors. The<br />

Physiology of Reproduction. New York:<br />

Raven Press, 1994: 541-584.<br />

116. Schillo KK, Dierschke DJ, Hauser ER.<br />

Influences of month of birth and age on<br />

patterns of luteinizing hormone secretion<br />

in prepubertal heifers. Theriogenology<br />

1982; 18: 593-598.<br />

117. Stahringer RB, Neuendorff DA, Ran<strong>de</strong>l<br />

RD. Seasonal variations in characteristics<br />

of estrus cycles in pubertal Brahman<br />

heifers. Theriogenology 1990; 34: 407-<br />

415.<br />

118. Tortonese DJ, Inskeep EK. Effects of<br />

melatonin treatment on the attainment of<br />

puberty in heifers. J Anim Sci 1992; 70:<br />

2822-2827.<br />

119. Moore RY. Neural control of the pienal<br />

gland. Behav Brain Res 1996; 73: 125-<br />

130.<br />

120. Arendt J. Melatonin and the pineal gland:<br />

influence on mammalian seasonal and<br />

circadian physiology. Rev Reprod 1998;<br />

3: 13-22.<br />

121. Izard MK, Van<strong>de</strong>nbergh JG. The effects<br />

of bull urine on puberty and calving date<br />

in crossbred beef heifers. J Anim Sci<br />

1982; 55: 1160-1168.<br />

122. Rekwot P, Ogwu D, Oyedipe E, Sekoni<br />

V. Effect of bull exposure and body<br />

growth on onset of puberty in Bunaji and<br />

Friesian x Bunaji heifers. Reprod Nutr<br />

Dev 2000; 40: 359-367.<br />

123. Byerley DJ, Staigmiller RB, Berardinelli<br />

JG, Short RE. Pregnancy rates of beef<br />

heifers bred either on puberal or third<br />

estrus. J Anim Sci 1987; 65: 645-650.<br />

124. Staigmiller RB, Bellows RA, Short RE,<br />

MacNeil MD, Hall JB, Phelps DA,<br />

Bartlett SE. Concepción rates in beef<br />

heifers following embryo transfer at the<br />

pubertal or third estrus. Theriogenology<br />

1993; 39: 315.<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

Larios-Jiménez A, Flores-Sandoval F, Escobar-Medina FJ, <strong>de</strong> la Colina-Flores F. First calving in beef<br />

cows. Heifers may have their first calf at 24 months of age; <strong>de</strong>pending on their age at puberty and first<br />

conception. Nutrition, breed, season and exposure to the bull may as well influence the age at puberty. This<br />

topic of reproductive physiology is focus of the present review. <strong>Veterinaria</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong> <strong>2007</strong>; 3: 1-12<br />

Key words: puberty, first conception, first calving, beef cow<br />

12

EL COMPORTAMIENTO HIGIÉNICO DE LA ABEJA APIS MELLIFERA Y SU APLICACIÓN EN<br />

EL CONTROL DE LA VARROOSIS<br />

Carlos Aurelio Medina-Flores<br />

Unidad Académica <strong>de</strong> Medicina <strong>Veterinaria</strong> y Zootecnia <strong>de</strong> la <strong>Universidad</strong> Autónoma <strong>de</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong>.<br />

E-mail: carlosmedina@uaz.edu.mx<br />

RESUMEN<br />

El comportamiento higiénico se consi<strong>de</strong>ra como uno <strong>de</strong> los principales mecanismos <strong>de</strong> tolerancia <strong>de</strong> la abeja<br />

Apis mellifera contra el ácaro Varroa <strong>de</strong>structor. En el presente trabajo se discuten los factores que influyen<br />

en la expresión <strong>de</strong> este comportamiento <strong>de</strong> la abeja Apis mellifera y su relación con el control <strong>de</strong> Varroa<br />

<strong>de</strong>structor.<br />

Palabras clave: Apis mellifera, Comportamiento higiénico, Varroa <strong>de</strong>structor<br />

<strong>Veterinaria</strong> <strong>Zacatecas</strong> <strong>2007</strong>; 3: 13-20<br />

INTRODUCCIÓN<br />

Las abejas melíferas (Apis mellifera), reutilizan<br />

las celdas <strong>de</strong> sus panales para alojar varias<br />

generaciones <strong>de</strong> crías, lo cual no suce<strong>de</strong> con otros<br />

insectos sociales como las abejas sin aguijón y<br />

abejorros. 1,2<br />

La limpieza <strong>de</strong> estas celdas <strong>de</strong>spués <strong>de</strong><br />

cada ciclo <strong>de</strong> cría es una actividad importante<br />

realizada por las abejas adultas, sin embargo,<br />

cuando una larva o pupa muere en el interior <strong>de</strong> la<br />

celda durante su <strong>de</strong>sarrollo se presenta un<br />

problema <strong>de</strong> limpieza <strong>de</strong>ntro <strong>de</strong> la colonia. 3<br />

Otra actividad <strong>de</strong> limpieza <strong>de</strong>ntro <strong>de</strong>l<br />

nido <strong>de</strong> Apis mellifera es el comportamiento<br />

higiénico, esta actividad la <strong>de</strong>sarrollan<br />

principalmente abejas <strong>de</strong> 15 y 17 días <strong>de</strong> edad 2 , y<br />

consiste en <strong>de</strong>tectar, <strong>de</strong>sopercular y remover <strong>de</strong><br />

sus celdas a la cría enferma o muerta. 3,4 Este<br />

comportamiento, es un mecanismo utilizado para<br />

la <strong>de</strong>fensa en contra <strong>de</strong> enfermeda<strong>de</strong>s <strong>de</strong> la cría<br />

como loque americana (Paenibacillus larvae<br />

larvae), cría calcárea (Ascosphaera apis) 1,5 y<br />

contra el ácaro Varroa <strong>de</strong>structor. 6<br />

Los métodos más efectivos para el<br />

control <strong>de</strong> Varroa <strong>de</strong>structor consisten en el uso<br />

<strong>de</strong> productos químicos los cuales son costosos,<br />

provocan que el ácaro <strong>de</strong>sarrolle resistencia y<br />

contaminan los productos <strong>de</strong> la colmena,<br />

afectando su aceptación en el mercado. Lo más<br />

a<strong>de</strong>cuado es promover el <strong>de</strong>sarrollo <strong>de</strong>l<br />

comportamiento higiénico, para lo cual se requiere<br />

estudiarlo y establecer las condiciones apropiadas<br />

para su ejecución por las abejas. En el presente<br />

trabajo se discuten los aspectos relacionados con<br />

el estudio <strong>de</strong>l comportamiento higiénico en<br />

colonias <strong>de</strong> abejas melíferas así como su<br />

aplicación en el control <strong>de</strong> la varroosis.<br />

INFLUENCIA GENÉTICA Y AMBIENTAL<br />

DEL COMPORTAMIENTO HIGIÉNICO<br />

Uno <strong>de</strong> los trabajos más importantes sobre<br />

comportamiento higiénico lo realizó<br />

Rothenbuhler, 8 el cual <strong>de</strong>terminó que su <strong>de</strong>sarrollo<br />

<strong>de</strong>pendía <strong>de</strong> la presencia <strong>de</strong> dos loci recesivos en<br />

homocigocis. Posteriormente fue reportado que la<br />

herencia <strong>de</strong> esta conducta pue<strong>de</strong> ser controlada<br />

por más <strong>de</strong> dos loci recesivos. 9,10<br />

Recientemente Lapidge et al. 11 por medio<br />

<strong>de</strong> técnicas moleculares <strong>de</strong>tectaron siete loci, <strong>de</strong><br />

los cuales tres <strong>de</strong> ellos fueron asociados solamente<br />

con la <strong>de</strong>soperculación <strong>de</strong> las celdas, y cuatro con<br />

influencia en el proceso <strong>de</strong> remoción.<br />

Por otro lado, los valores <strong>de</strong><br />

heredabilidad <strong>de</strong>l comportamiento higiénico han<br />

sido variables. 12 basados en la regresión madre–<br />

hija reportan un valor <strong>de</strong> 0.18 <strong>de</strong> heredabilidad <strong>de</strong><br />

la cría infestada con un ácaro Varroa <strong>de</strong>structor,<br />

mientras que para la remoción <strong>de</strong> la cría muerta<br />

usando el método <strong>de</strong> punción <strong>de</strong> la celda es <strong>de</strong><br />

0.36. 12 Contrariamente, Harbo y Harris 13 basados<br />

en la remoción <strong>de</strong> la cría muerta por el método <strong>de</strong><br />

enfriamiento reportan 0.65, mientras que la<br />

heredabilidad calculada bajo condiciones <strong>de</strong><br />

laboratorio para el <strong>de</strong>soperculado <strong>de</strong> las celdas fue

C A Medina-Flores<br />

<strong>de</strong> 0.14, y para la remoción <strong>de</strong> la cría muerta fue<br />

<strong>de</strong> 0.02. 14 La expresión <strong>de</strong>l comportamiento<br />

higiénico <strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong> la edad <strong>de</strong> la cría, <strong>de</strong> la<br />

proporción <strong>de</strong> abejas higiénicas <strong>de</strong>ntro <strong>de</strong> la<br />

colonia, 1,15,16 <strong>de</strong> la cantidad <strong>de</strong> néctar 17-19 y <strong>de</strong>l<br />

polen disponible. 20 Contrario a lo registrado por<br />

Spivak y Gilliam, 1 el comportamiento higiénico,<br />

no está influenciado por la “fortaleza” <strong>de</strong> las<br />

colonias, medida con base a cantidad <strong>de</strong> panales<br />

con abejas adultas y cría. 5,21<br />

La remoción aumenta con el incremento<br />

<strong>de</strong>l número <strong>de</strong> ácaros (Varroa <strong>de</strong>structor) por<br />

celda, por la presencia <strong>de</strong> virus en el parásito 14 y<br />

por el tipo <strong>de</strong> panal; pupas infestadas y alojadas en<br />

panales <strong>de</strong> plástico son removidas más<br />

rápidamente que las pupas infestadas que se<br />

encuentran en panales <strong>de</strong> cera. 6,22,23<br />

DETERMINACIÓN Y FRECUENCIA DEL<br />

NIVEL DE COMPORTAMIENTO<br />

HIGIÉNICO EN POBLACIONES DE<br />

COLONIAS DE A. MELLIFERA<br />

La i<strong>de</strong>ntificación <strong>de</strong> colonias con el<br />

comportamiento higiénico se ha realizado<br />

infectando a la cría con esporas <strong>de</strong> P. larvae, 8<br />