world cancer report - iarc

world cancer report - iarc

world cancer report - iarc

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

HUMAN PAPILLOMAVIRUS VACCINATION<br />

SUMMARY<br />

>Infection with human papillomaviruses<br />

is common and causes some benign<br />

lesions as well as cervical and other <strong>cancer</strong>s.<br />

> Vaccines based on human papillomaviruses<br />

may be prophylactic, therapeutic<br />

or a combination of both, and are<br />

potentially a safe and effective means of<br />

preventing or controlling disease.<br />

> Technical difficulties associated with the<br />

development of such vaccines are considerable,<br />

but several phase I, II and III<br />

trials are under way.<br />

From a public health perspective, there is<br />

an overwhelming case to justify the development<br />

of human papillomavirus (HPV)<br />

vaccines. At least 50% of sexually active<br />

adults have had a genital HPV infection. Socalled<br />

“low-risk” HPV types cause benign<br />

lesions or genital warts, while others, called<br />

“high-risk” or “oncogenic” types, are the<br />

principal cause of cervical <strong>cancer</strong> and are<br />

also associated with other <strong>cancer</strong>s of the<br />

anogenital region, and possibly with <strong>cancer</strong>s<br />

of the upper aerodigestive tract and of<br />

the skin (Chronic infections, p56; Cancers<br />

of the female reproductive tract, p215).<br />

Since both genital warts and cervical <strong>cancer</strong><br />

rates are rising in young women in<br />

some populations, the burden of HPV-associated<br />

disease is likely to increase in coming<br />

decades.<br />

HPV-associated lesions can regress spontaneously<br />

due to cell-mediated immunity.<br />

This is indicated by an increased risk of<br />

HPV infection and of HPV-associated<br />

lesions in immunosuppressed patients, and<br />

the observation that neutralizing antibodies<br />

can block HPV infection in vivo and in vitro<br />

[1]. On the other hand, the occurrence of<br />

chronic HPV infections and reinfections<br />

suggests that in some individuals natural<br />

immunity is not effective in controlling HPV<br />

148 Prevention and screening<br />

infection. Although the exact mechanisms<br />

of immune evasion are not fully understood,<br />

the development of effective vaccines<br />

for papillomaviruses in various animal<br />

models [2-4] has stimulated the development<br />

of similar vaccines for humans.<br />

Three main types of HPV vaccine are being<br />

developed: prophylactic vaccines, therapeutic<br />

vaccines and combined or chimeric<br />

vaccines which have both effects.<br />

Prophylactic vaccines<br />

Vaccines based on the induction of neutralizing<br />

antibodies against the HPV structural<br />

proteins L1 and L2 are termed “prophylactic”.<br />

The generation of virus-like<br />

particles (VLPs), which are morphologically<br />

indistinguishable from authentic virions,<br />

apart from lacking the viral genome [5],<br />

has greatly accelerated the development<br />

of these vaccines (Table 4.9).<br />

VLPs for HPV 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 39, 45<br />

and 58 have been produced in various laboratories.<br />

At least five HPV VLP-based<br />

vaccines have been developed and have<br />

gone through pre-clinical evaluation.<br />

Phase I-II clinical trials to assess safety,<br />

immunogenicity, dose, schedule, route of<br />

administration and adjuvants for these<br />

vaccines are being planned or have been<br />

initiated. The US National Cancer Institute<br />

(NCI) vaccine has been shown, in a phase<br />

I study of 58 women and 14 men, to be<br />

able to induce serum antibody titres that<br />

are approximately 40-fold higher than that<br />

observed during natural infection [6].<br />

However, certain basic issues need to be<br />

solved before the mass use of these vaccines<br />

can commence [7,8]. Such issues<br />

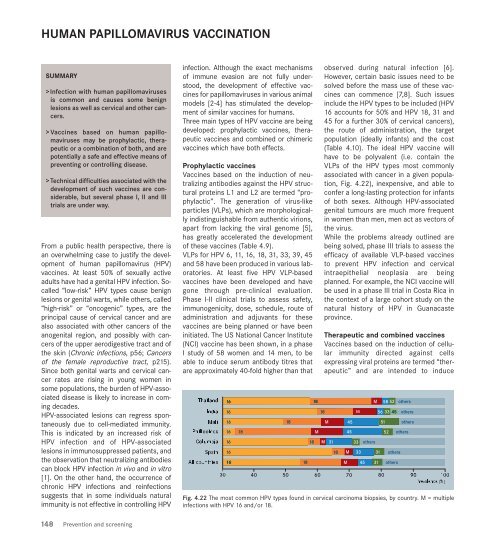

include the HPV types to be included (HPV<br />

16 accounts for 50% and HPV 18, 31 and<br />

45 for a further 30% of cervical <strong>cancer</strong>s),<br />

the route of administration, the target<br />

population (ideally infants) and the cost<br />

(Table 4.10). The ideal HPV vaccine will<br />

have to be polyvalent (i.e. contain the<br />

VLPs of the HPV types most commonly<br />

associated with <strong>cancer</strong> in a given population,<br />

Fig. 4.22), inexpensive, and able to<br />

confer a long-lasting protection for infants<br />

of both sexes. Although HPV-associated<br />

genital tumours are much more frequent<br />

in women than men, men act as vectors of<br />

the virus.<br />

While the problems already outlined are<br />

being solved, phase III trials to assess the<br />

efficacy of available VLP-based vaccines<br />

to prevent HPV infection and cervical<br />

intraepithelial neoplasia are being<br />

planned. For example, the NCI vaccine will<br />

be used in a phase III trial in Costa Rica in<br />

the context of a large cohort study on the<br />

natural history of HPV in Guanacaste<br />

province.<br />

Therapeutic and combined vaccines<br />

Vaccines based on the induction of cellular<br />

immunity directed against cells<br />

expressing viral proteins are termed “therapeutic”<br />

and are intended to induce<br />

Fig. 4.22 The most common HPV types found in cervical carcinoma biopsies, by country. M = multiple<br />

infections with HPV 16 and/or 18.