OUSEION - Memorial University of Newfoundland DAI

OUSEION - Memorial University of Newfoundland DAI

OUSEION - Memorial University of Newfoundland DAI

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

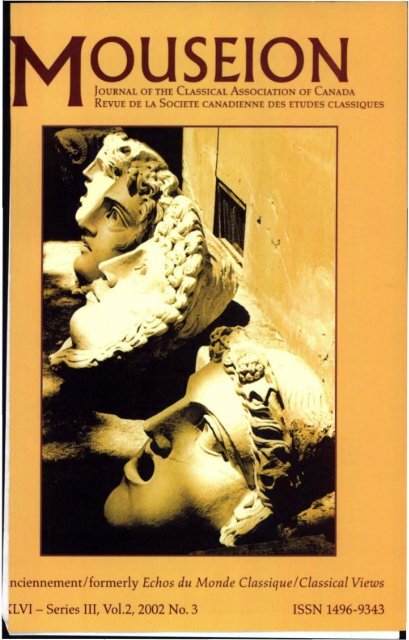

MOUSE/ON<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> the Classical Association <strong>of</strong> Canada<br />

Revue de la Societe canadienne des etudes classiques<br />

XLVI - Series III, Vol. 2,2002 NO·3<br />

ARTICLES<br />

David Shive. "OJ.lT7POC aaaToc 299<br />

Craig Cooper, Aristoxenos, TTEpi (3fcvv and Peripatetic Biography 307<br />

H. Roisman. Alice and Penelope: Female Indignation in Eyes Wide<br />

Shut and the Odyssey 34 I<br />

BOOK REVIEWS/COMPTES RENDUS<br />

Sergio Ribichini. Maria Rocchi. Paolo Xella. eds., La questione<br />

delle influenze vicino-orientali sulla religione greca<br />

(Noel Robertson) 365<br />

Stanley Lombardo. trans., Sappho. Poems and Fragments<br />

(Bonnie Maclachlan) 373<br />

Nino Luraghi. ed.. The Historian's Craft in the Age <strong>of</strong>Herodotus<br />

(James Allan Evans) 377<br />

fohn Barsby. ed. and trans.. Terence (Benjamin Victor) 383<br />

foan Booth and Guy Lee. Catullus to Ovid: Reading Latin<br />

Love Elegy (Barbara Weiden Boyd) 388<br />

David R. Slavitt. trans.. Propertius in Love: The Elegies<br />

(Steven J. Willett) 392<br />

Patricia A. Rosenmeyer, Ancient Epistolary Fictions: The Letter in<br />

Greek Literature (Kathryn Chew) 40I<br />

::;raham Anderson, Fairytale in the Ancient World<br />

(Steve Nimis) 404<br />

H.A. Drake, Constantine and the Bishops: The Politics <strong>of</strong><br />

Intolerance (Eric Fournier) 407<br />

\1anfred Clauss. The Roman Cult <strong>of</strong>Mithras. The God and his<br />

Mysteries (John Beck) 410<br />

t\ndrew Calimach. Lovers' Legends: The Greek Gay Myths<br />

(B. Verstraete) 413<br />

:-I.H. Huxley. An Earlier Four-Word Elegaic Couplet 415<br />

:ndex to Volume XLVI/Series III. Volume 2 417

Editorial Correspondents/Conseil consultatif: Janick Auberger.<br />

Universite du Quebec a Montreal: Patrick Baker. Universite Laval:<br />

Barbara Weiden Boyd. Bowdoin College: Robert Fowler. <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

Bristol: John Geyssen. <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> New Brunwsick: Mark Golden.<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Winnipeg: Paola Pinotti. Universita di Bologna: James<br />

Rives. York <strong>University</strong>: c.J. Simpson. Wilfrid Laurier <strong>University</strong>: Lea<br />

Stirling. <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Manitoba<br />

REMERCIEMENTS/ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

Pour l'aide financiere qu'ils ont accordee a la revue nous tenons a<br />

remercier / For their financial assistance we wish to thank:<br />

Conseil de recherches en sciences humaines du Canada / Social Sciences<br />

and Humanities Research Council <strong>of</strong> Canada<br />

Societe des etudes classiques de l'ouest canadien / Classical Association<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Canadian West<br />

Dean <strong>of</strong> Arts. <strong>Memorial</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Newfoundland</strong>.<br />

Brock <strong>University</strong><br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Calgary<br />

Concordia <strong>University</strong><br />

McGill <strong>University</strong><br />

Universite de Montreal<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> New Brunswick<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Prince Edward Island<br />

Trent <strong>University</strong><br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Victoria<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Waterloo<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Western Ontario<br />

Wilfrid Laurier <strong>University</strong><br />

We acknowledge the financial support <strong>of</strong> the Government <strong>of</strong> Canada.<br />

through the Publication Assistance Program (PAP). toward our mailing<br />

costs.<br />

No part <strong>of</strong> this publication may be reproduced. stored in a retrieval system or<br />

transmitted. in any form or by any means. without the prior written consent <strong>of</strong><br />

the editors or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access<br />

Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence. visit www.accesscopyright.ca or<br />

call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

AVIS AUX AUTEURS<br />

I. Les references aux reuvres modernes doivent etre formulees<br />

comme Ie montrent les exemples suivants:<br />

A.T. Tuilier. Etude comparee du texte et des scholies d·Euripide. Paris. 1972.<br />

pp. 101-123 [non pas IOlff.]<br />

P. Grimal. « Properce et Ia Iegende de Tarpeia ». REL. 30 (1952). pp. 32-33 [non<br />

pas 32f.]<br />

Dans les cas exceptionnels formuler selon les regles de l'edition la<br />

plus recente de The Chicago Manual <strong>of</strong> Style.<br />

Pour les titres de periodiques. utiliser les abreviations employees<br />

dans L'Annee Philologique.<br />

Citer comme suit ces reuvres de base:<br />

V. Ehrenberg. REIIIA.2. 1373-1453<br />

IG213 2<br />

10826<br />

aL4.789<br />

TLL2. 44.193<br />

2. Les references aux auteurs antiques doivent etre formulees comme<br />

Ie montrent les exemples suivants:<br />

Platon. Banquet. 17Sd. non pas PI. Smp. 17Sd3-4<br />

Tacite. AnnaJes. 11.6. non pas Tac. Ann. 2.6.4<br />

Plutarque. De sera numinis vindicta (ou De sera) 7-8. non pas Plu. Mor. SS3c-e<br />

3. Priere de traduire toutes les citations du latin ou du grec. sauf les<br />

mots simples et les locutions courtes.<br />

4. Les manuscrits soumis a l'evaluation doivent etre en double interligne<br />

avec d'amples marges. Une fois une communication acceptee.<br />

l'auteur doit en fournir un resume de 100 mots environ. et Ie<br />

materiel d'illustration-tableaux. diae;rammes. cartes-doit etre<br />

soumis sous forme prete a Ia reproduction.<br />

5. La revue s'occupe des frais d'edition jusqu'a six planches/illustrations<br />

par communication: l'auteur doit porter les frais au-dela de ce<br />

chiffre. Le cout de chaque planche/illustration en demi-page est de<br />

12$. et Ie cout de chacune en page est de 20$.<br />

6. L'auteur d'une communication rec;oit gratis 20 tires a part: l'auteur<br />

d'une revue critique en rec;oit 10 gratis. On peut commander des<br />

tires a part supplementaires a un cout modeste.

ALICE AND PENELOPE:<br />

FEMALE INDIGNAnON IN EYES WIDE SHUT AND THE ODYSSEY<br />

H.ROISMAN<br />

Les femmes n'ont jamais aime qu'on les prenne pour acquises. pas plus dans<br />

l'Antiquite que nos jours. Deux reuvres presentent. malgre leurs differences<br />

d'epoque. de culture et de genre. un point de vue commun sur Ie couple. oil les<br />

maris. quelque soient leurs motifs. considerent leurs epouses comme acquises :<br />

L'Odyssee d'Homere et Ie film de Stanley Kubrick. Eyes Wide Shut (1999). Dans<br />

les deux cas. les epouses. pr<strong>of</strong>ondement <strong>of</strong>fensees. se vengent en semant dans<br />

l'esprit de leur conjoint Ie doute sur leurs exploits sexuels.

306 DAVIDSHNE<br />

Presumably. aTTlC aTEp. "without destruction." glossed Ot/T' aaaTov.<br />

"nor very destructive." and then replaced the aardvarkian adjective.<br />

resulting in the reprobate OUT' aTTlC aTEp. "nor without destruction."<br />

In this way corruption is at least plausibly explained. It should. moreover.<br />

be noted that avaTOV (avaaTov). "non destructive." was Sophocles'<br />

adjective <strong>of</strong> negative prefix (KaKwv avaToc DC 786. "free <strong>of</strong><br />

harm"). so that aaaTOV was left to be the intensive "very destructive"<br />

just as later in Apollonius-and in Horner earlier.<br />

THE CENTER FOR HELLENIC STUDIES<br />

WASHINGTON. DC 20008

Mouseion. Series III. Vol. 2 (2002) 307-339<br />

©2002 Mouseion<br />

ARISTOXENOS. n EPI 13iwv AND PERIPATETIC BIOGRAPHY<br />

CRAIG COOPER<br />

An important work on the history <strong>of</strong> ancient biography. at least in<br />

terms <strong>of</strong> the reaction it generated. was Leo' s Die griechisch-romische<br />

Biographie nach ihrer literarischen Form (Leipzig Ig01); most scholars<br />

working on the subject have had to come to terms with his conclusions.<br />

particularly his attempt to see the origins <strong>of</strong> biography in the Peripatos.<br />

Beginning with an investigation <strong>of</strong> the literary form <strong>of</strong> Suetonius'<br />

biographies. Leo reconstructed an entire history <strong>of</strong> the genre. based<br />

on a distinction between a Plutarchean and Suetonian form <strong>of</strong> biography;<br />

the former had its origin in the Peripatos. the latter in Alexandria.<br />

The Plutarchean form <strong>of</strong> biography entailed a straightforward<br />

chronological narrative <strong>of</strong> events to illustrate an individual's character<br />

and was particularly well-suited to the lives <strong>of</strong> generals or statesmen.<br />

The Suetonian form <strong>of</strong> biography. developed by Alexandrian grammarians.<br />

which Leo labelled"grammatical." was simple. schematic and<br />

as such formally resembled the systematic structure <strong>of</strong> other erudite<br />

works on literary figures. Alexandrians. like Kallimachos. Satyros.<br />

Hermippos. Leo's so-called "Halbperipatetiker" and Herakleides Lembos.<br />

marked a transition from Peripatetic to grammatical biography.'<br />

Ultimately. then. all biography in one form or another. in one way or<br />

another. had its origin in the Peripatos. In this paper. I would like to<br />

return to the problem <strong>of</strong> Peripatetic biography. particularly as it relates<br />

to Aristoxenos. and to the thorny question <strong>of</strong> what constitutes biography.<br />

First. however. I want to address the question <strong>of</strong> genre.<br />

THE QUESTION OF GENRE<br />

Leo envisaged a generic distinction between the two forms <strong>of</strong> biography<br />

and attempted to subsume every form <strong>of</strong> biographical activity<br />

under one or other <strong>of</strong> the generic forms. Hence Theopompos fell under<br />

the Peripatetic rubric' and Suetonius fashioned his political biographies<br />

along the lines <strong>of</strong> the "grammatical" bioi which were more<br />

suited to the lives <strong>of</strong> literary figures. The need first to establish genres<br />

J Herakleides' epitomes <strong>of</strong> Hermippos. Satyros and Sotion transformed these<br />

highly elaborate literary biographies into biographies <strong>of</strong> a grammatical form.<br />

"from books for the general public to a book for scholarly use"; see Leo (1901) 135·<br />

, Or at least was influenced by the Peripatos; see Leo (1901) 110-112.<br />

3°7

308 CRAIG COOPER<br />

<strong>of</strong> ancient historical literature and second to categorize fragmentary<br />

remains <strong>of</strong> that literature under these fixed genres was a concern <strong>of</strong><br />

early twentieth-century scholars. most evident in Jacoby's Die Fragmente<br />

der griechischen Historiker. 3 The conceptional framework for<br />

his collection was his notion that the genre <strong>of</strong> history developed in a<br />

linear sequence from mythography to enthnography. through<br />

chronography to contemporary history and onto horography.4 Each<br />

author was arranged according to his place in this historical development<br />

<strong>of</strong> the genre. Leo was simply part <strong>of</strong> the same phenomenon.<br />

studying the development <strong>of</strong> a genre <strong>of</strong> historiography. namely biography.<br />

according to its two literary forms and classifying the fragmentary<br />

remains <strong>of</strong> all biographical works under these fixed categories.<br />

In fact. Jacoby himself intended to gather the fragments <strong>of</strong> biographical<br />

writers in FGrHist IV: originally biography was to be<br />

treated with the history <strong>of</strong> literature and antiquarian literature with<br />

horography.5 The plan changed and Jacoby eventually envisaged the<br />

volume containing both antiquarian literature and biography. and<br />

many modern scholars have seen a close connection between the two. 6<br />

His outline <strong>of</strong> FGrHist IV <strong>of</strong> some 70 pages contained 24 rubrics under<br />

which were listed various authors and titles <strong>of</strong> works. 7 But as G.<br />

Schepens notes. several comments by Jacoby indicate that he was still<br />

uneasy about the exact place to assign the history <strong>of</strong> literature in relation<br />

to biography (somewhere between "Biographie" and "Sammlungen").8<br />

and in the notes reproduced by Schepens there are indications<br />

that Jacoby was at times uncertain how to classify particular works:<br />

would they be better assigned to the genre <strong>of</strong> biography. or to literary-history.<br />

music or "Sammelwerke"?9 This uncertainty about the<br />

exact relationship between biography. antiquarian literature and literary<br />

history. on the one hand. and where precisely or under what precise<br />

genre to locate given works. on the other. is a problem that stems<br />

not just from the fragmentary evidence which we are left to deal with<br />

but also from the modern fixation with classifying various forms <strong>of</strong><br />

3 See especially Jacoby (1909) 80-122.<br />

4 See Marincola (1999) 284-289.<br />

5 Jacoby (1909) 61-62; d. Schepens (1997) 149.<br />

6 Arrighetti (1977).<br />

7 For a detail summary <strong>of</strong> the "Entwurf" and methodological problems facing<br />

those undertaking the continuation <strong>of</strong> Jacoby's FGrHist. see Schepens (1997)<br />

144-171.<br />

8 Schepens (1997) 149.<br />

9 Schepens (1997) 152-153.

ARISTOXENOS AND PERIPA TETIC BIOGRAPHY 309<br />

historiography under precise genres. a problem that was not necessarily<br />

felt by the ancient writers or their audience. lo<br />

The difficulty with this approach. as recent scholars have pointed<br />

out. is that the ancients may not have had a fixed or static conception <strong>of</strong><br />

genre. As J. Marincola notes. Jacoby's "teleological view" <strong>of</strong> the development<br />

<strong>of</strong> genre prevented him from seeing historiography as a dynamic<br />

and responsive form <strong>of</strong> writing that both looked back to and<br />

innovated on earlier forms <strong>of</strong> literature." Moreover. modern categories<br />

<strong>of</strong> historical literature may not always correspond to ancient categories<br />

and what we may expect <strong>of</strong> a genre was not necessarily what an<br />

ancient audience might have expected or demanded. 12 This meant that<br />

a historian could include all kinds <strong>of</strong> material in his work. whether<br />

ethnography. paradoxa or antiquarian material. l ) As Marincola notes<br />

(307) Jacoby's category <strong>of</strong> "philologic-antiquarian" works is based on a<br />

modern separation <strong>of</strong> philology and history which does not correspond<br />

to ancient notions. Following Conte's approach to Latin poetry.14 with<br />

its "empty slots" into which a subsequent writer <strong>of</strong> a genre can slip<br />

and fill a gap in his genre. Marincola (300-30r) suggests a more flexible<br />

notion <strong>of</strong> genre. which sees various forms <strong>of</strong> historiography in a<br />

"constant state <strong>of</strong> flux <strong>of</strong> reaction and revision." Instead <strong>of</strong> a "generic<br />

taxonomy" Marincola (30r-307) suggests five criteria in analysing historical<br />

works: narrative/non-narrative. focalization. chronological limits.<br />

chronological arrangement and subject matter. This may be a useful<br />

point <strong>of</strong> departure for analysing another important category <strong>of</strong><br />

ancient historiography. bioi.<br />

10 Schepens' observations about Neanthes ([1997] 159) are worth mentioning<br />

here. The earliest know writer <strong>of</strong> nEpi Evo6l;wv Cxvopwv. Neanthes wrote a<br />

number <strong>of</strong> types <strong>of</strong> historiographical works. a fact "which should inspire caution<br />

against a tendency in modern literature to draw rather sharp dividing lines between<br />

political and military historiography on the one hand and biography and<br />

antiquarian literature on the other."<br />

II Marincola (1999) 291, 299.<br />

12 The ancients did recognize certain categories <strong>of</strong> historical writing such as<br />

archaiologia which covered early history. including genealogies and foundations;<br />

war monographs which may have been a sub-genre <strong>of</strong> "history <strong>of</strong> deeds";<br />

local histories which were not necessarily always annalistic. though they could<br />

be. like the Atthidographers; and finally universal histories. In all cases the emphasis<br />

was not form or orientation but subject matter. On these categories and<br />

this point see Marincola (1999) 293-294.<br />

I) As Flower (1997) 153 notes. Theopompos' Philippika "is a composite <strong>of</strong><br />

every type <strong>of</strong> historical research that had come before." including genealogy.<br />

ethnography. mythology. chronography and the war monograph.<br />

14 Conte(1994) 116-1 IT

310<br />

CRAIG COOPER<br />

BIOI AS GENRE<br />

That the bios was a recognizable category <strong>of</strong> historiography. perhaps<br />

with its own conventions. at least in terms <strong>of</strong> subject matter. is suggested<br />

by Plutarch's comment at the beginning <strong>of</strong> his Life <strong>of</strong> Alexander<br />

that he is not writing historiai but bioi. I5 According to Plutarch<br />

great deeds <strong>of</strong> war. as they are narrated by historians. reveal less <strong>of</strong> a<br />

man's virtues or vices than a little event or <strong>of</strong>f-hand remarks. Plutarch's<br />

concern is character. and what he will include in his narrative<br />

are insignificant details not mentioned by historians that reveal such<br />

character. It may seem from these comments that bioi were defined by<br />

the kind <strong>of</strong> content included. In this same passage Plutarch goes on to<br />

compare himself to a painter who shapes his bios by paying attention<br />

to the small details and leaving to others. namely historians. the great<br />

contests. 16<br />

Past scholars have taken Plutarch's remarks here as a programmatic<br />

statement <strong>of</strong> Plutarch's general approach to the writing <strong>of</strong> biography<br />

and have even regarded them as reflecting some broadly accepted<br />

definition <strong>of</strong> the distinction between history and biography. 17<br />

But as T. Duff has argued. I8 this programmatic statement belongs specifically<br />

to the context <strong>of</strong> the Life <strong>of</strong> Alexander. as a means to distinguish<br />

this particular life from other historiographical works on the<br />

same theme. The distinction between history and political biography<br />

and similar historiographical works. as Duff observes. was never<br />

clearly drawn. 19 In fact. Plutarch himself seems to envision some <strong>of</strong> his<br />

own lives as being closely related to history and in fact describes them<br />

as historiai. 2O At the beginning <strong>of</strong> the Life <strong>of</strong> Demosthenes (2.1). Plutarch<br />

remarks as follows:<br />

15 "If I do not record all their most celebrated achievements or describe any <strong>of</strong><br />

them exhaustively, but merely summarize for the most part what they accomplished.<br />

I ask my readers not to regard this as a fault. For we are not writing<br />

historiai but bioi. and the truth is that the most brilliant exploits <strong>of</strong>ten tell us<br />

nothing <strong>of</strong> the virtues or vices <strong>of</strong> the men who performed them while on the other<br />

hand a chance remark or a joke may reveal far more <strong>of</strong> a man's character (ethos)<br />

than the mere feat <strong>of</strong> winning battles in which thousands fall. or <strong>of</strong> marshaling<br />

great armies. or laying siege to cities." (trans. I. Scott-Kilvert)<br />

16 See Duff (1999) 17 for his discussion <strong>of</strong> this image.<br />

17 Wardman (1971) 254.<br />

18 Duff (1999) 15-21.<br />

19 Duff (1999) 17.<br />

20 For examples see Duff (1999) 21. On the close relationship <strong>of</strong> Plutarch's lives<br />

to historiography see Wardman (1971) 257-261. (1974) 2-10, 154-161; d. Scardigli<br />

(1995) 17. 21 -2.3.25.

ARISTOXENOS AND PERIPATETIC BIOGRAPHY 311<br />

When a man has undertaken to compose a historia. the sources for<br />

which are not easily available in his own country. or do not even exist<br />

there. the case is quite different. Because most <strong>of</strong> his material must be<br />

sought abroad or may be scattered among different owners. his first<br />

concern must be to base himself upon a city which is famous. wellpopulated<br />

and favourable to the arts. Here he may not only have access<br />

to all kinds <strong>of</strong> books. but through hearsay and personal enquiry he may<br />

succeed in uncovering the facts which <strong>of</strong>ten escape the chroniclers and<br />

are preserved in more reliable form in human memory. and with these<br />

advantages he can avoid the danger <strong>of</strong> publishing a work which is defective<br />

in many or even the most essential details. (trans. I. Scott<br />

Kilvert)<br />

I suspect that even though Plutarch had chosen to live in a small town.<br />

this was precisely the kind <strong>of</strong> work he sought to compose. a historia<br />

not deficient in details which had eluded other writers. Again the kind<br />

<strong>of</strong> content is important and marks out the distinction between his form<br />

<strong>of</strong> historiography and that <strong>of</strong> others. 21<br />

Plutarch's comments in Life <strong>of</strong> Demosthenes recall his claim for the<br />

Life <strong>of</strong> Nikias. 22 As in the Life <strong>of</strong> Alexander so here Plutarch simply<br />

summarizes the most celebrated <strong>of</strong> Nikias' deeds, as they were narrated<br />

by historians. Plutarch tells his reader that he could not neglect<br />

deeds <strong>of</strong> Nikias which were narrated by Thucydides and Philistos. especially<br />

when they cast light on Nikias' character, but he has only<br />

treated them summarily to avoid the charge <strong>of</strong> negligence. Instead he<br />

has attempted to collect together certain details "which have eluded<br />

most writers altogether and have been mentioned haphazardly by<br />

others. or are recorded in decrees or in ancient votive <strong>of</strong>ferings." His<br />

purpose. he says (Nik. 1.5). is not to "accumulate a useless historia but<br />

to hand down whatever may serve to make my subject's character and<br />

temperament better understood...<br />

21 As Duff (1999) 17 notes. historia in the Alexander is used in the particular<br />

sense <strong>of</strong> a large-scale history but elsewhere "could be used in a general sense to<br />

mean any kind <strong>of</strong> narrative." or as Wardman (1974) 5 notes. in the sense <strong>of</strong> enquiry.<br />

22 "There is a true parallel. I believe. between the lives <strong>of</strong> Nicias and Crassus.<br />

and between the disasters <strong>of</strong> the Sicilian and the Parthian expeditions. However.<br />

the first is a subject which Thucydides has already handled incomparably. surpassing<br />

even his own high standards. not only in the pathos but in the brilliance<br />

and variety <strong>of</strong> his narrative. So I must appeal to the reader not to think me as<br />

vain as Timaeus. who flattered himself that he could outdo Thucydides in skill<br />

and show up Philistus as a throughly uninspired and amateurish write1'.<br />

There can be no question. <strong>of</strong> course. <strong>of</strong> passing over those <strong>of</strong> Nicias' actions<br />

which Thucydides and Philistus have recorded, especially since they throw so<br />

much light upon his character and disposition. which were so <strong>of</strong>ten obscured by<br />

his great misfortunes. but here I have touched briefly on the essentials to avoid<br />

the charge <strong>of</strong> negligence." (trans. I. Scott-Kilvert)

ARISTOXENOS AND PERIPA TETIC BIOGRAPHY 313<br />

which is shaped by and revealed in his actions. 27 The consistency with<br />

which Plutarch uses Peripatetic terms to describe his biographical<br />

method and aims has led some scholars to conclude that Plutarch was<br />

following a formalized Peripatetic theory <strong>of</strong> biography.28 Scholars are<br />

no longer prepared to go that far. nor. in fact. are all bioi that have<br />

come down to us so ethically oriented. This point can be easily illustrated<br />

by comparing Plutarch's Demosthenes with the life <strong>of</strong><br />

Demosthenes in the Moralia (844b-848d). where one finds a complete<br />

absence <strong>of</strong> ethical concerns.<br />

Nor for that matter is the study <strong>of</strong> character the exclusive preserve<br />

<strong>of</strong> bioi. On Plutarch's own admission. Thucydides and Philistos wrote<br />

narratives that revealed character. Theopompos. according to ancient<br />

critics like Dionysios <strong>of</strong> Halicarnassos (Pomp. 6.7). had the ability to<br />

detect the motives <strong>of</strong> actors in history and reveal their apparent virtue<br />

and undetected vice. 29 Motives most commonly attributed to his characters<br />

are akrasia and philotimia. 30 and philotimia is a character trait<br />

that Plutarch attributes to many heroes and illustrates in the narratives<br />

<strong>of</strong> their lives. 31 But as far as we can tell. the ancients never regarded<br />

the Philippika. which was a history centered on an individual and<br />

whose very title might suggest biography. as anything but historyY<br />

Perhaps it can be argued that Theopompos played an important role in<br />

the development <strong>of</strong> biography. but that is a separate issue; what Theapompos<br />

was up to was not biography as far as the ancients were concerned.<br />

So subject matter alone is not enough to distinguish bioi from history.<br />

Where the writer <strong>of</strong> bioi and the writer <strong>of</strong> historia parted company<br />

were in the "larger elements <strong>of</strong> historical composition-speeches.<br />

battles. geographical excursuses."33 Scale or size was the difference:<br />

where historia described large battles. bioi included small events or'<br />

abbreviated the account. where historia included speeches. bioi sayings.<br />

34 where historia provided chronological development. bioi were<br />

27 Leo (1901) 188: Hamilton (1999) xliv: Russell (1966) 144. (1995) 81-82. (1973)<br />

105-106.<br />

28 Dihle (1956) 63: d. Scardigli (1995) 10.<br />

29 For a discussion <strong>of</strong> this famous evaluation see Shrimpton (1991) 21. and<br />

Flower (1997) 170.<br />

30 Flower (1997) 170-174: Shrirnpton (1991) 136-151.<br />

3 1 Wardrnan (1974) 115-12.4: Russell (1973) 106.<br />

3 2 Flower (1997) 149·<br />

33 Russell (1966) 148. (1995) 87.<br />

34 On small events and sayings as the biographer's counterpart to battles and<br />

speeches see Wardrnan (1971) 254-256.

3 14<br />

CRAIG COOPER<br />

less concerned with chronological progression 35 but could include a<br />

chronological outline. 36 marked by notable dates or synchronismsY<br />

Epitornization thus seemed to be the hallmark <strong>of</strong> bioi and perhaps<br />

helps make sense <strong>of</strong> Plutarch's apology. He simply summarized and<br />

abbreviated. which was precisely what writers <strong>of</strong> bioi did. 38<br />

What this also means is that as a category <strong>of</strong> historiography bioi<br />

could overlap with and resemble various other forms <strong>of</strong> historiography.<br />

whether history. literary-history or antiquarian research. It could<br />

thus include all kinds <strong>of</strong> material but not on the same scale or in the<br />

same detail as these other forms <strong>of</strong> historiography. Whether a biography<br />

had a narrative structure or not was not important. Satyros' bios<br />

<strong>of</strong> Euripides. for instance. was composed as a dialogue. In many respects<br />

it formally resembles literary monographs <strong>of</strong> so-called periliterature<br />

by Peripatetics like Chamaileon, employing the very same<br />

methods <strong>of</strong> biographical inference based on the poets's writing. 39 Focus<br />

on the individual, though an important criterion. was not exclusive<br />

to bioi; histories too could centre on the individual and bioi could. it<br />

seems. also be about nations or cities. as Dikaiarchos' nep\ TOO [3iov<br />

Ti')c 'EAAaboc or as in Klearchos' nep\ [3iwv (more below). Chronological<br />

arrangement was less important than perhaps the chronological<br />

limits for defining bioi. The limit was obviously the life itself from its<br />

beginning to its end: the writer <strong>of</strong> a bios <strong>of</strong> an individual would most<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten begin with the birth <strong>of</strong> that individual and end with his death; in<br />

the case <strong>of</strong> a city or nation. begin when it was founded and end when<br />

it was destroyed. lost it independence or reached some other significant<br />

end. But whether a bios always had to cover an individual's entire<br />

35 On Plutarch's lack <strong>of</strong> concern for chronology or chronological development<br />

see Russell (1966) 148. (1995) 87. (1973) 102-103.<br />

36 Wardman (1971) 256.<br />

37 See for instance FOxy 2438. which preserves a brief biography <strong>of</strong> Pindar,<br />

with chronological statements based on chronographic lists; see Gallo (1g68) 16.<br />

See also life <strong>of</strong> Aristotle in D.L. 5.1(}-1 I. On similar types <strong>of</strong> chronological signposts<br />

in ps.-Plu. Vit. X. see Cooper (1992) 54-55.<br />

38 See Geiger (1988) 249. who argues that Plutarch's innovation beyond Nepos<br />

lay in part in the scale <strong>of</strong> his biographies.<br />

39 On the close affinity between Satyros' biography and the problemataliterature<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Peripatetics see Latte in Dihle (1956) 105 n. I; between it and the<br />

peri-literature <strong>of</strong> Chamaeleon in particular see Momigliano (1993) 73. On the<br />

character <strong>of</strong> peri-literature see Leo (1901) 104-106, 317-318. (1960a) 369. (1960c)<br />

387-394: Pfeiffer (1g68) 217-218: Arrighetti (1964) 12-21. (1977) 31-49: Momigliano<br />

(1993) 70 and n. 6. On the biographical method <strong>of</strong> Chamaeleon see Leo (l960a)<br />

368-369. (l960c) 390: Arrighetti (1964) 22. 26. (1977) 31-49.

ARISTOXENOS AND PERIPATETIC BIOGRAPHY 3 IS<br />

life from birth to death is not absolutely certain. 40 Certainly the shape<br />

the bios took as it moved within the chronological limits <strong>of</strong> birth and<br />

death would depend largely on the focus <strong>of</strong> the writer. Whether he<br />

treated Demosthenes. for instance. as a literary or political figure<br />

would determine what material <strong>of</strong> his life he wished to emphasize. In<br />

the case <strong>of</strong> the former more emphasis could corne on his early education.<br />

rhetorical training and literary production and thus resemble a<br />

literary monograph or work on rhetoric: in the case <strong>of</strong> the latter. the<br />

critical moments <strong>of</strong> his political career. as would be expected <strong>of</strong> a history.<br />

but even these could be included in a literary biography which<br />

sought to highlight-though not in the same way or in the same detail<br />

as a political bios-the whole life from birth to death. There was really<br />

no chronological system as in the case <strong>of</strong> histories. which arranged<br />

their chronologies either along an annalistic pattern. or by magistrates<br />

or by areasY A bios could include chronological signposts or synchronisms<br />

which highlighted an important moment in the life. but the<br />

chronology itself was <strong>of</strong> secondary importance. What was important<br />

was linking that moment with another event <strong>of</strong> equal or greater significance<br />

to emphasize the fame <strong>of</strong> that individualY<br />

What. then. characterized bioi in antiquity as a separate form <strong>of</strong><br />

historiography distinct from other forms <strong>of</strong> historiography? It was a<br />

brief account <strong>of</strong> a life from its beginning to end: in the case <strong>of</strong> a man's<br />

life. from birth to death. Here we have not moved far. if at all. beyond<br />

Momigliano's definition: "An account <strong>of</strong> a man's life from birth<br />

to death. "43 As Momigliano points out, though. this definition "has the<br />

advantage <strong>of</strong> excluding any discussion <strong>of</strong> how biography should be<br />

written." Thus a bios could have a narrative structure. be schematically<br />

arranged or set as a dialogue: so long as it remained an account<br />

<strong>of</strong> a life. it could follow any form. include any kind <strong>of</strong> material. borrow<br />

from various sources and thus resemble other forms <strong>of</strong> historiography.<br />

the degree <strong>of</strong> similarity being dependent on the amount <strong>of</strong> ma-<br />

4 0 Momigliano (1993) I I I-I 12 notes the possibility that Nicolaos <strong>of</strong> Damascus'<br />

life <strong>of</strong> Augustus may have only been a partial biography down to 20 BCE.<br />

covering the formative years <strong>of</strong> Augustus. In this he had good precedent in Xenophon's<br />

Cyropacdia and books by Onesikritos and Marsyas on Alexander's education.<br />

0. Wilamowitz-Moellendorf (1995) 64-65·<br />

4 1 Marincola (1999) 305-306.<br />

4 2 For instance. Lysias arrived in Athens in the archonship <strong>of</strong> Kallias, after<br />

the Four Hundred had taken power and was banished. when the battle <strong>of</strong> Aigospotamoi<br />

had taken place and the Thirty seized power (Mor. 835e). Isokrates died<br />

in the archonship <strong>of</strong> Chairondos after hearing the news <strong>of</strong> Chaironeia (Mar.<br />

837e).<br />

43 Mamigliano (1993) I I.

316 CRAIG COOPER<br />

terial included in the bios from another category <strong>of</strong> historiography.<br />

Thus a work which we or even the author himself might not have regarded<br />

as a real biography could have been regarded as a bios by<br />

ancient readers.<br />

THE QUESTION OF PERIPATETIC BIOGRAPHY<br />

In his preface to De viris illustribus Jerome lists Peripatetics among<br />

Suetonius' forerunners in biography: apud Graecos Hermippus Peripateticus.<br />

Antigonus Carystius. Satyrus dactus vir. et omnium longe<br />

doctissimus Aristoxenus musicus (Wehrli II. fro lOb). All except Antigonos<br />

were in some way connected with the Peripatos. Both Hermippos<br />

and Satyros are called Peripatetics. which may reflect not so much<br />

an association with the Peripatos itself but the style <strong>of</strong> their bioi which<br />

was in some way modelled on earlier Peripatetic writings. 44 Aristoxenos<br />

was himself a student <strong>of</strong> Aristotle and was the first Peripatetic to<br />

write monographs devoted to an individua1. 45 All this suggests. despite<br />

what scholars say. that the Peripatos played an important role in shaping<br />

Hellenistic biography.4 6<br />

For Leo the true beginning <strong>of</strong> biographical activity started with the<br />

Peripatetics. and it was this biographical activity which precisely characterized<br />

the schoolY It is generally agreed that the Peripatetics<br />

showed an interest in biography. but scholars are reluctant to believe<br />

that the Peripatetics wrote genuine biographies. 48 So. for instance. G.<br />

Arrighetti argues that it is difficult to reconcile a taste for partisan biographies<br />

with the scientific research into the history <strong>of</strong> the arts and<br />

sciences which the Peripatos promoted. 49 In the introduction to his edition<br />

<strong>of</strong> Satryros' bios <strong>of</strong> Euripides. Arrighetti reexamines the whole<br />

question <strong>of</strong> Peripatetic biography.5 0 He also attempts to define Satyros'<br />

position in the history <strong>of</strong> ancient biography. Leo had placed Satyros.<br />

whom he had regarded as "Halbperipatetiker." among those Kallimacheans<br />

who had marked out the transition from Peripatetic to Alex-<br />

44 Arrighetti (1964) 3; Leo (1901) 118; Heibges (1912) 845: Pfeiffer (1g68) 150-151;<br />

Brink (1946) 11-12; but contrast West (1974) 279-287. Cf. Bollansee (1999a) 9-14.<br />

45 'APXUTO 13ioc (Wehrli II !I9451. frs. 47-50); CWKpClTOVC 13ioc (frs. 51-60):<br />

nMITwvoc 13ioc (frs. 61-68); TeAECTov 13ioc (fr. 117); nepl nv6oy6pov KOI TWV<br />

yvwpillwv OUTOO (frs. 11-25); d. Arrighetti (1964) 12.<br />

46 Momigliano (1993) 73-74.<br />

47 Leo (1901) 99; d. Arrighetti (1964) 6.<br />

4 8 See Momigliano (1993) 105- I 2I.<br />

49 Arrighetti (1964) 6.<br />

50 Arrighetti (1964) 12-20; d. Gallo (1967) 156-157.

3 I B<br />

CRAIG COOPER<br />

Polykrates and Harpagos. the Mede. It is clear from fro 16. which has<br />

Pythagoras in Samos during the reign <strong>of</strong> Polykrates. that at least the<br />

synchronism between Polykrates. Anakreon and Pythagoras in fro 12<br />

goes back to Aristoxenos. 53 This synchronism first established by Aristoxenos<br />

and elaborated by later biographers was introduced to account<br />

for Pythagoras' travels. Hence the tyranny <strong>of</strong> Polykrates would justify<br />

his travel to Italy. while his flight from tyranny was consistent with his<br />

political activities among the Greek cities <strong>of</strong> Italy where he called for<br />

general freedom (fr. 17).54 The tendentious nature <strong>of</strong> many <strong>of</strong> these<br />

synchronisms can best be seen in the anecdote <strong>of</strong> Simichos. who is said<br />

by Aristoxenos to have laid down his tyranny after hearing Pythagoras<br />

(fr. 17). In a similar vein. the capture <strong>of</strong> Pythagoras by Kambyses<br />

during his Egyptian campaign (fr. 12) helps account for Pythagoras'<br />

journey to Babylon. where he was initiated into Persian rites.<br />

Here he also met up with the Chaldaean Zaratas (fr. 13).<br />

This concern for precise chronology may indicate that Aristoxenos<br />

was equally concerned with relating the events <strong>of</strong> Pythagoras' life<br />

from its beginning (birth) to its end (death). which by our definition<br />

would make the nep\ nv8ay6pov a bios. As we have noted. Aristoxenos<br />

went into Pythagoras' origins (fr. IIa). The precise length <strong>of</strong> each<br />

transmigration is given at 216 years (fr. 12). no doubt to account for<br />

Pythagoras' claim that he had once resided in the body <strong>of</strong> Euphorbos.<br />

55 The length <strong>of</strong> his natural life is given at 82 years (fr. 12). His<br />

departure from Samos is precisely dated to his fortieth year (fr.I6).<br />

while Kylon's insurrection in Kroton against the Pythagoreans there is<br />

explicitly said to have taken place in Pythagoras' old age (fr. 18). The<br />

trouble in Kroton led to Pythagoras' withdrawal to Metapontion.<br />

where Aristoxenos depicts the end <strong>of</strong> his life: we do not know whether<br />

Aristoxenos went on to narrate the details <strong>of</strong> his death. but this seems<br />

likely. since he had already included an account <strong>of</strong> the death <strong>of</strong><br />

Pherekydes and his burial by Pythagoras. his student (fr.I4).<br />

Thus it would seem that Aristoxenos gave an account <strong>of</strong> Pythagoras'<br />

life from birth to death. which we suggest constitutes a bios. The chronology<br />

was arranged around Pythagoras' travels which took him far<br />

and wide to Delphi. Babylon and finally to Italy. The accounts <strong>of</strong> his<br />

travels allowed Aristoxenos to bring Pythagoras into contact with various<br />

teachers. from whom he derived many <strong>of</strong> his own teachings. Thus<br />

we find him in Babylon where he is instructed by Zaratas the Chal-<br />

53 Wehrli II (1945) 50.<br />

54 Wehrli II (1945) 51-52.<br />

55 See Wehrli II (1945) 50 for his discussion on whether Pythagoras had two or<br />

three such transmigrations.

ARISTOXENOS AND PERIPA TETIC BIOGRAPHY 321<br />

warded a long life as a consequence <strong>of</strong> his Pythagorean practices. In<br />

similar fashion. episodes in Pythagoras' life. such as his flight from<br />

the tyrant Polykrates (fr. 16) or Simichos' relinquishing <strong>of</strong> tyranny (fr.<br />

17). are intended to illustrate Pythagorean EAEu8Epla. In particular. fro<br />

17. which describes his political activities promoting freedom among<br />

the Greek cities <strong>of</strong> Italy and Sicily. would aptly suit the kind <strong>of</strong> material<br />

found in nEpl 13iwv. a type <strong>of</strong> work which scholars think does not<br />

present actual biographies but types <strong>of</strong> lives that illustrated particular<br />

virtues and vices. In the case <strong>of</strong> Xenophilos he is compared to Gorgias.<br />

another philosopher famed for his longevity. who later was represented<br />

by Klearchos in his n EPI 13iwv as an example <strong>of</strong> those who were<br />

rewarded for virtue. It is to these works that we now turn for comparison.<br />

nEpl13iwv<br />

According to modern scholars. bios could denote either a biography <strong>of</strong><br />

an individual or a type <strong>of</strong> life ("Lebensform") where a particular lifestyle<br />

("Lebensfiihrung") is represented. o, Arrighetti states that Leo<br />

had observed that the title nEpl 13iwv did not presuppose the biographical<br />

character <strong>of</strong> the work. since the word bios could denote<br />

"vita" or "genre di vita." and that the double meaning <strong>of</strong> the word can<br />

clearly be seen from the different titles nEpl 13iwv and Bioc TaU<br />

oElva. 02 The problem is that Leo ([19oI] 96-99) never makes the distinction<br />

as clearly or as forcefully as Arrighetti wants. nor did the ancients.<br />

Bios, even when it came to mean the biography <strong>of</strong> a person.<br />

continued to connote the "type <strong>of</strong> life" he had lived and as such always<br />

had an ethical colouring. Some biographers, like Hermippos. perhaps<br />

aware <strong>of</strong> the ambiguity. preferred. unlike Satyros and Sotion. the<br />

more neutral flavoured nEpl TaU oElva. O ) What is clear. though. is that<br />

Leo saw the birth <strong>of</strong> biography within the context <strong>of</strong> philosophy; philosophy<br />

became the ars vivendi. ars vitae and what naturally flowed<br />

from this. according to Leo (97). was a concern for the life <strong>of</strong> the individual.<br />

In Leo's mind (99). the study <strong>of</strong> the individual. both in ethical<br />

and biographical terms. gained prominence with the Peripatetics. o4<br />

nEpi nveay6pov Kai TWV yvwPIl-lWV Q\1TOU or to nEpi TOU nveayoplKOv<br />

r=>lov. This only emphasizes how much cross-over <strong>of</strong> material there was between<br />

related types <strong>of</strong> Peripatetic works. The attribution to the former work seems to<br />

be based on Gellius' wording in libra quem de Pythagora rdiquit.<br />

01 Wehrli X (1959) [15.<br />

02 Arrighetti (1964) 13.<br />

03 Bollansee (I999b) 102.<br />

04 "Durch Aristoteles und seine Schuler war die empirische Erforschung des

32 6<br />

CRAIG COOPER<br />

bouring city <strong>of</strong> Karbina: finally, they were punished through divine<br />

intervention (fl'. 48). Each "life," it seems, has become so schematized<br />

to fit an ethical pattern that motifs are readily transferred from one<br />

life to the next. Hence the hybris <strong>of</strong> the Tarentines, the rape <strong>of</strong> the<br />

women and children <strong>of</strong> Karbina, whom they had gathered into the<br />

temple square, is precisely that <strong>of</strong> the Lydians (fl'. 43a) and <strong>of</strong> Dionysios<br />

the younger (fl'. 47).8 4 The Lydians gathered the wives and<br />

daughters <strong>of</strong> others to the place euphemistically called "Chastity,"<br />

while Dionysios gathered the Locrian girls into a large hall.<br />

The ethical pattern <strong>of</strong> Klearchos' nEp\ l3iwv with its accompanying<br />

topoi repeats itself not only in the "lives" <strong>of</strong> cities and nations but also<br />

<strong>of</strong> individuals. Hence Dionysios is represented committing the same<br />

hybris as the Lydians and Tarentines, and despite a problem in the<br />

text the admonishment which concludes fl'. 47 clearly connects truphe<br />

with the hybris<strong>of</strong> the tyrant: "And so, we should beware <strong>of</strong> so-called<br />

luxury which is an overthrower <strong>of</strong> all lives and regard insolence as<br />

destructive."85 His punishment-to serve as mendicant priest <strong>of</strong> Kybele-reminds<br />

us <strong>of</strong> the punishment <strong>of</strong> the Lydians who were forced<br />

to serve under a woman to reflect their effeminate behaviour,86 or<br />

that <strong>of</strong> the Medes (fl'. 49) who after making eunuchs <strong>of</strong> their neighbours<br />

were forced to bear the humiliation <strong>of</strong> watching the Persians<br />

adopt their own practice <strong>of</strong> "Apple-bearing," as a punishment<br />

(Tl\.lwp[a) but also as "a reminder into what depths <strong>of</strong> effeminacy the<br />

luxury <strong>of</strong> the body-guards went" (Ti'je TWV 8opvq>OpOVVTWV Tpvq>i'je<br />

de oeov TjA80v Cxvav8piae tJ'lTo\.lvTj\.la). Klearchos, or at least<br />

Athenaios, concludes with an admonition similar to the one we find in<br />

the case <strong>of</strong> Dionysios: "For so it seems, their immoderate and frivolous<br />

luxury in their life can even turn men armed with spears into beggars.<br />

,,87 That is to say the Medes through their excessive luxury had<br />

become like the emasculated priests <strong>of</strong> Kybele, the mendicant CxyVp<br />

Tal. 88<br />

Polykrates for his part imitated the effeminate practices <strong>of</strong> the<br />

84 a. Wehrli III (1948)63.<br />

85 Fr. 47: EUAa13TjTEOV ovv nlV KaAoullEVTjV Tpuq>rjV oveav TWV (3iwv<br />

avaTponr,v alTllvTwv TE tOAE8plOV liyEie8alt nlV iJ13PIV.<br />

86 After saying that Omphale was the first to begin the punishment.<br />

Athenaios continues TO yap uno yvvalKoc apXEc801 u(3pli;;oIlEvoue CTlIlEiov ECTl<br />

13iae, where (3ioe is substituted for 13iae by Capps.<br />

87 Fr. 49: ovvaTOI yap, we EOIKEV, Ii napaKOIpoe Cilla Ka! llaTOIOe aUTwv<br />

mp! TOV 13iov TpUq>r, Ka! TOlle Taie AOYXOIe Ka8wnAIellEvoue ayvpTae<br />

anoq>aiVEIV.<br />

88 Gulick 5 (1963)314n.a.

336 CRAIG COOPER<br />

stability that comes to Italy and Sicily during the ascendancy <strong>of</strong> the Pythagoreans<br />

are not due to political factors but to the reception <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Pythagorean message which teaches that stasis and discord must by<br />

every means be removed from city and home as a disease from the<br />

body (fr. 17). The widespread insurrection that later arose against Pythagoras<br />

and the other Pythagoreans is reduced by Aristoxenos to a<br />

personal act <strong>of</strong> revenge carried out by Kylon. which the other states<br />

look on with indifference. 114 According to Aristoxenos' account, Kylon<br />

was rejected from Pythagorean society because <strong>of</strong> his violent and tyrannical<br />

nature (fr. 18). and as such he forms the antithesis <strong>of</strong> Simichos<br />

who freely embraced the Pythagorean ideal and laid aside tyranny. In<br />

keeping with his philosophical ideals. as he did at Samos. Pythagoras<br />

voluntarily withdrew to Metapontion long before the actual attack<br />

upon Milon's house and not as a consequence <strong>of</strong> it. This characterization<br />

<strong>of</strong> Pythagoras forces Aristoxenos to play down the tradition which<br />

told <strong>of</strong> widespread insurrection against the Pythagoreans in several<br />

cities <strong>of</strong> Italy (Plb. 2.39. Dik. fro 34). But on the whole Aristoxenos. like<br />

Dikaiarchos. works within the framework <strong>of</strong> the tradition: as Wehrli<br />

points out, it is historically possible. apart from the personal motivations<br />

which Aristoxenos gives. that the insurrection <strong>of</strong> Kylon was preceded<br />

by a long period <strong>of</strong> ineffectual opposition on the part <strong>of</strong> the Kylonians.<br />

115 Aristoxenos has only reworked the tradition to emphasize a<br />

particular aspect <strong>of</strong> Pythagoras' philosophical character. but that is<br />

something that all biographers did and still do.<br />

To deny. as Arrighetti has. that Aristoxenos wrote biography is. I<br />

think. to ignore and prejudice what the ancients themselves regarded<br />

as biography and. worse yet. to impose on them our own perceptions<br />

<strong>of</strong> what makes biography. Biography. or at least certain kinds <strong>of</strong> biography.<br />

were about types and about ethics. To say a writer had partisan<br />

and ethical concerns should not mean that he did not and could not<br />

write biography: even Plutarch had these concerns and chose. as Aristoxenos<br />

before him. to rework or at least selectively retell history to<br />

emphasize his perception <strong>of</strong> an individual's type and character. We<br />

may. as Gomme,'16 regard Plutarch more as a moral essayist than a<br />

biographer. but Plutarch certainly knew what he was up to in writing<br />

bioi. and we can assume the same <strong>of</strong> Aristoxenos. His aim. as that <strong>of</strong><br />

Dikaiarchos or Klearchos. may have been philosophical instruction.<br />

but what he produced. in the minds <strong>of</strong> ancient readers. were bioi, ac-<br />

114 Wehrli II (r948) 52.<br />

115 Wehrli II (1948) 52-53.<br />

116 Gomme (1956) 54.

ARISTOXENOS AND PERIPA TETIC BIOGRAPHY 337<br />

counts <strong>of</strong> lives from their beginning to their end. In this context J. 801lansee's<br />

comments about Hermippos. an important Hellenistic biographer.<br />

are salutary: "the concept <strong>of</strong> the faithful portrayal <strong>of</strong> a man's<br />

life and times was entirely foreign to Hermippos. "117 There is much in<br />

Hermippos' biography that would reflect more the work <strong>of</strong> an antiquarian<br />

than a biographer. But as Bollansee rightly notes (186), the<br />

problem is with us scholars who "have high expectations for. and<br />

make great demands on, a genre which on the surface bears some obvious<br />

similarity to its present-day counterpart ... but which in antiquity<br />

unquestionably served entirely different purposes."<br />

DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS<br />

UNIVERSITY OF WINNIPEG<br />

WINNIPEG. MB R,JB 2Eg<br />

REFERENCES<br />

Arrighetti. G. 1964: "Satiro. vita di Euripide," seo 13.<br />

__. 197T "Fra erudizione e biografia." se026: 13---{)7.<br />

Bollansee. J. I 999a. Hermippos <strong>of</strong> Symrna and his Biographcial Writings: A Reappraisal.<br />

Leuven.<br />

__. I 999b. Hermmippos<strong>of</strong>Symrna.FGrHist. IV A3. Leiden.<br />

Brink. K.O. 1946. "Callimachus and Aristotle: An inquiry into Callimachus'<br />

npOI nPAzlANHN." CQ40: 11-12.<br />

Burkert. W. 1972. Lore andScience in Ancient Pythagoreanism. Trans. E.L. Minai'<br />

Jr. German Original 1962. Weisheit und Wissenschaft Studien zu Pythagoras.<br />

Philolaos und Platon. Cambridge. MA.<br />

Conte. G.B. 1994. Genres and Readers: Lucretius. Love Elegy. Pliny's Encyclopedia.<br />

Trans. G. Most. Italian Original 1991. Generi e lettori: Lucrezio, J'eJegia<br />

d'amore. J'enciclopedia di PJinio. Baltimore.<br />

Cooper. C. 1992. The Development <strong>of</strong> the Biographical Tradition on the Athenian<br />

Orators in the HeJJenistic Period. Diss. British Columbia.<br />

Dihle. A. 1956. Studien zurgriechischen Biographie. AbhandJungen der Akademie<br />

der Wissenschaften Gdttingen. Philologisch-historische Klasse 37.<br />

Dover. K.J. 1988. "Anecdotes, gossip and scandal." in The Greeks and their Legacy:<br />

Collected Papers, Volume JI: Prose Literature, History, Society. Transmission.<br />

Influence. Oxford.<br />

Duff. T. 1999. Plutarch's Lives: Exploring Virtue and Vice. Oxford.<br />

Flower. M.A. 1994. Theopompus <strong>of</strong>Chios: History and Rhetoric in the Fourth Century<br />

B.C Oxford.<br />

Fortenbaugh, W.W. and Schiitmmpf. E.. eds. 2001. Dicaearchus <strong>of</strong> Messana: Text,<br />

Translation and Discussion. Rutgers <strong>University</strong> Studies in Classical Humani-<br />

117 Bollansee (1999a) 185.

ARiSTOXENOS AND PERIPATETIC BIOGRAPHY 339<br />

Schiitrurnpf (20or) 237-254.<br />

Scardigli. B, ed. 1995. Essays on Plutarch's Lives. OxfOl'd.<br />

Schepens. G. 1997. "Jacoby's FGrHist: Problems, methods. prospects," in Most<br />

(1997) 144-172.<br />

Schiitrurnpf. E. 2001. "Dikaiarchs "ioc 'EAAaboc und die Philosophie des viel'ten<br />

Jahrhunderts," in Fortenbaugh and Schiitrurnpf (2001) 255-277.<br />

Shrimpton, G. 1991. Theopompus the Historian. Montreal/Kingston.<br />

Ussher, RG. 1960. The Characters <strong>of</strong> Theophrastus. London; second edition with<br />

addenda, London 1993.<br />

Wardman, A. 1971. "Plutarch's methods in the Lives," CQ21: 254-261.<br />

__. 1974. Plutarch's Lives. London.<br />

Wehrli, F. 1944-1959. Die Schule des Aristotles, I-X. Basel.<br />

West, S. 1974. "Satyrus: Peripatetic or Alexandrian?," GRBS 15: 279-287.<br />

Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, U. von. 1995. "Plutarch as biographel'," in Scardigli<br />

(1995) 47-74·

Mouseion, Series III. Vol. 2 (2002) 341-364<br />

©2002 Mouseion<br />

ALICE AND PENELOPE:<br />

FEMALE INDIGNATION IN EYES WIDE SHUT<br />

AND THE ODYSSEY<br />

H. ROISMAN<br />

Wives do not like to be taken for granted. no more in ancient times<br />

than today. As different as Homer's Odyssey and Stanley Kubrick's<br />

Eyes Wide Shut (1999) are in medium. time. and culture. they share<br />

certain similarities in their depiction <strong>of</strong> the marital relationship. Both<br />

show husbands who. albeit for different reasons. take their wives for<br />

granted and indignant wives who strike back by verbally challenging<br />

their husband's sexuality. This essay starts with an analysis <strong>of</strong> the<br />

modern movie Eyes Wide Shut and proceeds to analyze the pertinent<br />

passages in the epic poem. the Odyssey.<br />

The theme <strong>of</strong> feminine indignation that is pivotal in Eyes Wide Shut<br />

is not present in Arthur Schnitzler's Dream Story. the late nineteenthcentury<br />

novella on which the film is based. Along with other changes.<br />

which have been amply noted by other scholars, Stanley Kubrick and<br />

Frederic Raphael added this theme to Schnitzler's story. Schnitzler's<br />

story can be read as a tribute to his close friend Sigmund Freud,<br />

whose dream theory the story both illustrates and qualifies. The story<br />

conveys in fictional form the then novel idea that women, like men.<br />

had forbidden and sometimes cruel and destructive sexual fantasies<br />

and desires. but then. departing from Freud. suggests that these desires.<br />

however strong and sweeping they might be. are not the core or<br />

fulcrum <strong>of</strong> the marital relationship. Kubrick and Raphael adopt these<br />

points in their entirety. At the distance <strong>of</strong> a century. however. neither<br />

Freud's notion <strong>of</strong> the importance <strong>of</strong> sex to human psychology nor<br />

Schnitzler's qualifications are quite as novel or interesting as they<br />

were when Schnitzler first gave them literary expression. Kubrick<br />

and Raphael thus had to find a somewhat different angle from which<br />

to treat the story so as to make it more relevant to audiences at the end<br />

<strong>of</strong> the twentieth century. Hence the theme <strong>of</strong> indignation.<br />

Eyes Wide Shut also reduces the importance <strong>of</strong> the dream motif.<br />

which is central to Schnitzler's story. The dream remains a vehicle for<br />

the heroine. Alice. to express herself. but the long. elaborate, and<br />

highly pictorial dream <strong>of</strong> her predecessor. Albertine. is substantially<br />

shortened and simplified. and its sadistic content and murderous urges<br />

considerably pared down in the film version. In place <strong>of</strong> the dream.<br />

34 1

342 H. ROISMAN<br />

the film emphasizes the indignation that the modern woman feels<br />

when her husband takes her for granted and fails to credit her with a<br />

vigorous and vital sexuality. and selfhood. <strong>of</strong> her own.<br />

The characters <strong>of</strong> the main protagonists and the grounds for their<br />

confrontation are set in the opening scenes <strong>of</strong> the film. as Bill and Alice<br />

Harford (Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman) prepare to go to a ball at the<br />

home <strong>of</strong> their friend Victor Ziegler (Sydney Pollack). Alice. in the en<br />

suite bathroom and dressed in her evening gown. asks Bill how she<br />

looks. Bill goes to the mirror to check his appearance and without looking<br />

at Alice says: "Perfect."<br />

Alice: Is my hair OK?<br />

Bill: It's great.<br />

Alice: You're not even looking at it.<br />

Bill: (turns and looks at her adoringly)<br />

It's beautiful.<br />

(He kisses her affectionately on the cheek and leaves the bathroom).<br />

You always look beautiful. (5)'<br />

With this opening. Kubrick and Raphael introduce us to two beautiful.<br />

self-absorbed individuals. both concerned with their own appearance.<br />

who relate to one another with an easy if superficial familiarity.<br />

which is not devoid <strong>of</strong> affection but patently lacking in the sexual<br />

charge that might be expected from their obvious youth. wealth. s0phistication.<br />

success. and good looks. Alice is shown as seeking reassurance<br />

with a somewhat childish and needy persistence. Bill is shown<br />

treating her as a prize trophy. as an unchangeable object that one need<br />

not look at too closely. since it is always the same. Yet their exchange.<br />

as laden with undercurrents as it is. is low-key and seemingly innocuous.<br />

as such exchanges tend to be between husbands and wives who<br />

essentially love one another and have learned to bear with each<br />

other's shortcomings.<br />

The flaws in their domestic orderliness are quickly developed in<br />

the next few scenes. First the babysitter and then several people at the<br />

Zieglers' party compliment Alice on her stunning appearance. The<br />

spontaneity and enthusiasm <strong>of</strong> their comments (e.g.. the babysitter<br />

exclaims. "Wow! You look amazing. Mrs. Harford.") underscore the<br />

perfunctoriness <strong>of</strong> Bill's unseeing compliments and underline the degree<br />

to which he takes his wife's beauty for granted. We are also<br />

given a glimpse <strong>of</strong> Alice's hurt and annoyance. and <strong>of</strong> her difficulty in<br />

expressing these feelings openly and directly. Rather than confront<br />

Bill. she ignores. or pretends to ignore. both his inattention and his<br />

, Stanley Kubrick and Frederic Raphael. Eyes Wide Shut (screenplay. Warner<br />

Books. 1999).

FEMALE INDIGNA nON 343<br />

compliments. and escapes into the safety <strong>of</strong> her role as mother. Rather<br />

than make a fuss as they are about to leave for the evening. she simply<br />

asks her husband whether he has given the babysitter their phone<br />

and pager numbers. and her young daughter whether she is ready<br />

for bed. Nicole Kidman plays this scene with a frozen expression on<br />

her face.<br />

The tensions burst to the surface in the argument in the bedroom<br />

scene the day after the ball. This scene is set against the background <strong>of</strong><br />

the Zieglers' ball and <strong>of</strong> the two scenes that follow it. showing the couple's<br />

lovemaking and Bill's treatment <strong>of</strong> a woman patient in his clinic.<br />

In the ball scenes. the audience is shown both husband and wife flirting<br />

mildly with individuals who approach them. Alice with the suave<br />

Sandor Szavost (Sky Dumont) and Bill with two young models. while<br />

being intensely aware <strong>of</strong> one another's movements and remaining<br />

faithful to each other. Yet while taking pains to show the couple's fidelity.<br />

Kubrick and Raphael play on the potential for infidelity inherent<br />

in the encounters with desirous and admiring strangers. They show<br />

Bill and especially Alice interested in their partners <strong>of</strong> the evening;<br />

show Ziegler. the host. with the call-girl Mandy in an upper room<br />

while his guests. and wife. are downstairs; and have Alice's partner <strong>of</strong><br />

the evening. Sandor Szavost. cynically declare that marriage necessitates<br />

deception and that women marry so as to be free to enjoy sex<br />

with the men they really want. The lovemaking after the party has a<br />

similarly double-edged quality. It assures the audience that Bill and<br />

Alice have channeled whatever arousal they had felt at the party to<br />

one another and that they still enjoy each other sexually. At the same<br />

time. though. set in the couple's bedroom. it is presented as domestic<br />

and relatively tame in comparison to the heightened. unconsummated.<br />

and fantasy-charged eroticism <strong>of</strong> their encounters at the party. Then.<br />

the antiseptic scenes with Bill and his patients the next day once again<br />

show his behavior to be above reproach. without even a tinge <strong>of</strong> impropriety.<br />

All in all. however. the libidinous ambience that had informed<br />

the party casts its shadow over all <strong>of</strong> Bill's and Alice's subsequent<br />

behavior. It suggests the longings and fantasies that lurk behind<br />

our day-to-day conduct. moral and faithful as that may be. and it is<br />

clearly behind the argument the next evening in the bedroom.<br />

The bedroom scene opens with what could be a prelude to lovemaking-Alice<br />

lying in bed in her underwear. Bill sitting next to her in<br />

his boxer shorts. and the two <strong>of</strong> them sharing a joint-but this quickly<br />

turns into an ugly and seemingly baseless fight. It is Alice who starts<br />

the fight by asking who the girls were that Bill was at the party with.<br />

crudely demanding whether he had sex with them. and accusing him<br />

<strong>of</strong> "blatantly hitting on" them (40). Alice's motives in starting and pur-

344<br />

H.ROISMAN<br />

suing the fight are not made entirely clear. The script does not tell us<br />

how much Alice genuinely suspected her husband's fidelity. how<br />

much she was projecting onto him her own unfulfilled desires <strong>of</strong> the<br />

night before. or how much she simply used the opportunity to get<br />

back at him for his taking her so much for granted. All three motives<br />

are plausible in the film. In any case. it soon becomes evident that her<br />

aim is to attack his manhood in any way possible. whether by accusing<br />

him <strong>of</strong> infidelity. male chauvinism and other lapses. or by making<br />

him jealous.<br />

At every step <strong>of</strong> the way. Bill falls prey to her aggressive and provocative<br />

attacks. To her accusatory question. "And where did you disappear<br />

to with them [the girls] for so long" (40). he responds first with<br />

the half truth that he had gone upstairs to take care <strong>of</strong> a suddenly ailing<br />

Ziegler. and then by asking Alice who her dancing partner had<br />

been and what he had wanted. These responses spur Alice to further<br />

attack. The fib. probably motivated by discretion (Bill had promised<br />

Ziegler to keep the incident with Mandy to himself). is transparent.<br />

since Alice had seen Ziegler looking healthy enough only a bit earlier<br />

in the evening. and probably piqued her anger yet further. His questions<br />

tell her that he is jealous. and incite her to keep chipping away at<br />

the masculine complacency that is behind his taking her for granted.<br />

Thus Alice replies that Szavost wanted sex "upstairs. then and there"<br />

(41). How true this is the audience cannot know. They know that an<br />

upstairs rendezvous was possible and they heard Szavost asking Alice<br />

to accompany him to the Zieglers' art gallery and inviting her to go<br />

out with him some other night. But they did not hear this explicit<br />

proposition. The audience is thus left with the sense that Alice is either<br />

stretching the truth to get back at her husband or. if not. that she has<br />

selected this particular detail in order to hurt and unman him.<br />

When her reply doesn't produce visible pain. she shifts tactics. Bill<br />

downplays the importance <strong>of</strong> the reported proposition: "Is that all?" he<br />

asks. Although these are angry and sarcastic words. Bill tries to make<br />

the proposition seem innocuous. "I guess that's understandable." he<br />

tells Alice. " ... because you are a very beautiful woman" (42). His response<br />

reflects an effort to project self-confidence by making it seem<br />

only natural that other men would desire his beautiful wife and by<br />

avoiding any expression <strong>of</strong> concern that she might have been drawn to<br />

the proposition or that she had acted or might act on it. Neither Alice<br />

nor the audience knows yet whether this nonchalance is real or assumed.<br />

In either case. his refusal to show jealousy apparently makes<br />

Alice even angrier and more determined to get back at him.<br />

Ignoring his praise <strong>of</strong> her beauty. much as she had earlier. and the<br />

expression <strong>of</strong> trust in his statement. she disengages from his embrace.

FEMALE INDIGNA nON 345<br />

gets up. and backs up toward the bathroom door, leaving him sitting<br />

frustrated on the bed, as she twists his words in a feminist expression<br />

<strong>of</strong> outrage. She asks whether because she is beautiful the only reason a<br />

man would like to talk to her is because he would like to have sex with<br />

her. "Is that what you're saying?" she asks defiantly (42). Bill had said<br />

nothing <strong>of</strong> the sort. Nor is it clear whether Alice really believes that he<br />

had. Her distortion serves several ends. It conveys her frustration that<br />

her husband does not credit her as an individual with a mind <strong>of</strong> her<br />

own and with things to say that will interest and attract men apart<br />

from her looks. It strives to shame Bill for his sexual desire for her,<br />

which he had been showing during the scene. by implying that the<br />

only reason he wants her is for her looks. And, even as she draws<br />

away from him. it projects onto him and other men her own suppressed<br />

libidinous urges.<br />

Bill. whether carried away by his desire, wishing to end the argument.<br />

or simply obtuse, does not relate to her distortion or to the anger<br />

and frustration that are behind it. Rather he tries to clarify his<br />

statement, as though her chagrin was based on no more than a verbal<br />

misunderstanding. "Well. I don't think it's quite that black and white,"<br />

he tells her, "but I think we both know what men are like" (43). Not to<br />

be placated by this stereotypic generalization, Alice promptly turns<br />

the tables on him by commenting that on this basis she should conclude<br />

that he wanted to have sex with the two models she saw him with (43).<br />

With this assertion. Alice moves the argument from what Bill (and she)<br />

might have done at the party to what he (and she) might have wanted<br />

to do.<br />

His response to her question evokes the same transition in her reply.<br />

To his assertion that he is an exception to the rule because "I happen<br />

to be in love with you and because we're married and because I<br />

would never lie to you or hurt you," Alice retorts: "Do you realize<br />

that what you're saying is that the only reason you wouldn't ... those<br />

two models is out <strong>of</strong> consideration for me, not because you really<br />

wouldn't want to?" (43). Her retort ignores his declaration <strong>of</strong> love for<br />

her and <strong>of</strong> fidelity to his marital bonds and undervalues the merit <strong>of</strong><br />

reining in one's sexual urges out <strong>of</strong> consideration for a spouse one<br />

loves and does not want to hurt. Rather it focuses on what he might<br />

want to do: on the hidden and suppressed desires that had been highlighted<br />

in the erotic atmosphere <strong>of</strong> the party scenes.<br />

At issue for Alice, and driving her anger, is Bill's inability or unwillingness<br />

to look beneath the surface <strong>of</strong> reality, for which he accounts<br />

well enough by the sort <strong>of</strong> stereotypic and rational observations<br />

to which he is prone. As Kubrick had apparently explained to Nicole<br />

Kidman. when she pressed him to rectify the logical flaws in Alice's

346<br />

H.ROISMAN<br />

argumentation. Alice's thinking is irrational, in keeping with her being<br />

stoned and angry. It is a reflection <strong>of</strong> her inner state. 2 Bill's thinking.<br />

unlike Alice's. does not extend to the hidden and irrational forces<br />

by which people are driven. himself and Alice included. Thus his rational<br />

suggestion that they "just relax" and his rational observation that<br />

the "pot is making you aggressive" only further enrage Alice. "No.<br />

it's not the pot. it's you!" she protests. and goes on to try to explain<br />

herself with enigmatic statements like ''I'm just trying to find out<br />

where you're coming from" (44). Although on the surface these statements<br />

are not very clear and seem to come out <strong>of</strong> nowhere. they suggest<br />

that Alice is put out by her husband's emotional opacity-that she<br />

would like him to be more aware <strong>of</strong> his deeper feelings. whether <strong>of</strong><br />

his jealousy or <strong>of</strong> the hidden desires that she pushes him to confess.<br />

and to reveal more <strong>of</strong> them to her.<br />

The more Bill tries to rectify their misunderstanding. the more Alice<br />

dwells on it. She proceeds now to pry about Bill's feelings towards<br />

his female patients and their feelings toward him. The focus <strong>of</strong> Alice's<br />

questions is not so much on the desires and fantasies <strong>of</strong> her husband's<br />

female patients as on his understanding. or lack <strong>of</strong> understanding. <strong>of</strong><br />

the women. The argument intensifies yet further when Bill confesses<br />

that he doesn't know what his fema,le patients feel toward him and<br />

then proceeds to state that women don't have the same sexual urges as<br />

men: "Look women don't ... they basically don't think like that" (46).<br />

This assertion leads Alice to stand up. provocatively point a finger<br />

at her husband. pace up and down. and finally come close. or as close<br />

as she will get. to stating what bothers her most about him. that as far<br />

as he is concerned women care about one thing only: "... just about<br />

security and commitment ... !" (46). Alice couches her objections to his<br />

assumption that women do not have the kind <strong>of</strong> purely sexual desires<br />

that men possess in generic terms: but her anger is not so much about<br />

her husband's failure to grasp female sexuality as about his failure to<br />

grasp. or even to consider. the depth. intensity. and richness <strong>of</strong> her<br />

own sexual desires and fantasies.<br />

Thus she swiftly brings the discussion from the level <strong>of</strong> generalization<br />

on which it had been conducted till then down to the concrete: herself<br />

and her husband. Bill provides the opportunity with his rational<br />

account <strong>of</strong> their argument. As he puts it. she is stoned. has been trying<br />

to pick a fight with him. and is now trying to make him jealous. This<br />