Tungíase: doença negligenciada causando patologia grave

Tungíase: doença negligenciada causando patologia grave Tungíase: doença negligenciada causando patologia grave

Tropical Medicine and International Health doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02545.x volume 15 no 7 pp 856–864 july 2010 A simple method for rapid community assessment of tungiasis L. Ariza 1 , T. Wilcke 2 , A. Jackson 2 , M. Gomide 3 , U. S. Ugbomoiko 4 , H. Feldmeier 2 and J. Heukelbach 5,6 1 Post-Graduation Program in Medical Sciences, School of Medicine, Federal University of Ceará, Fortaleza, Brazil 2 Charité University of Medicine, Institute of Microbiology and Hygiene, Berlin, Germany 3 Institute of Collective Health, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 4 Department of Zoology, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria 5 Department of Community Health, School of Medicine, Federal University of Ceará, Fortaleza, Brazil 6 Anton Breinl Centre for Public Health and Tropical Medicine, James Cook University, Townsville, Qld, Australia Summary objective To evaluate a rapid assessment method to estimate the overall prevalence of tungiasis and severity of disease in endemic communities. methods We analysed data from 10 population-based surveys on tungiasis, performed in five endemic communities in Brazil and Nigeria between 2001 and 2008. To assess the association between occurrence of tungiasis on six defined topographic areas of the feet and the true prevalence ⁄ prevalence of severe disease, linear regression analyses were performed. Estimated prevalences were calculated for each of the 10 surveys and compared to true prevalences. We then selected the most useful topographic localization to define a rapid assessment method, based on the strength of association and operational aspects. results In total, 7121 individuals of the five communities were examined. Prevalence of tungiasis varied between 21.1% and 54.4%. The presence of periungual lesions on the toes was identified as the most useful rapid assessment to estimate the prevalence of tungiasis (absolute errors: )4% to +3.6%; R 2 = 96%; P < 0.0001). Prevalence of severe tungiasis (>20 lesions) was also estimated by the method (absolute errors: )3.1% to +2.5%; R 2 = 76%; P = 0.001). conclusion Prevalence of tungiasis and prevalence of severe disease can be reliably estimated in communities with distinct cultural and geographical characteristics, by applying a simple and rapid epidemiological method. This approach will help to detect high-risk communities and to monitor control measures aimed at the reduction of tungiasis. Introduction keywords tungiasis, Tunga penetrans, Rapid Assessment Method, Brazil, Africa Tungiasis is a tropical parasitic skin disease caused by penetration of the jigger flea Tunga penetrans (Linnaeus 1758) into the skin of human or animal hosts (Heukelbach 2005). Hundreds of parasites may accumulate in heavily infested individuals (Feldmeier et al. 2003; Joseph et al. 2006; Ugbomoiko et al. 2007). The disease is a self-limited infestation (Eisele et al. 2003; Feldmeier & Heukelbach 2009), but complications such as bacterial super-infection and debilitating sequels are often seen in endemic areas (Bezerra 1994; Heukelbach et al. 2001; Feldmeier et al. 2002, 2003; Joseph et al. 2006; Ariza et al. 2007; Ugbomoiko et al. 2008). Septicaemia and tetanus are life-threatening complications of tungiasis (Tonge 1989; Litvoc et al. 1991; Greco et al. 2001; Feldmeier et al. 2002; Joseph et al. 2006). Typically, the disease occurs in poor communities in Latin America, the Caribbean and sub–Saharan Africa (Heukelbach et al. 2001; Heukelbach 2005). In recent cross-sectional studies from endemic areas in Brazil, Cameroon, Madagascar, Nigeria and Trinidad & Tobago, point prevalences ranged between 16% and 54% (Chadee 1998; Njeumi et al. 2002; Wilcke et al. 2002; Carvalho et al. 2003; Muehlen et al. 2003; Joseph et al. 2006; Ugbomoiko et al. 2007; Ratovonjato et al. 2008). However, prevalence and distribution of the disease are not documented in most endemic areas. In settings where financial and human resources are scarce, policy makers need cost-effective and simple methods to estimate prevalence and severity of disease in affected populations (Anker 1991; Vlassoff & Tanner 1992; Macintyre 1999; Macintyre et al. 1999). As a consequence, rapid assessment methods have been 856 ª 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

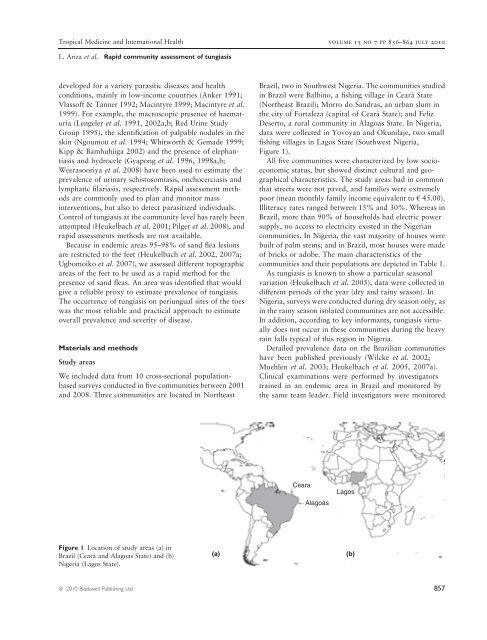

Tropical Medicine and International Health volume 15 no 7 pp 856–864 july 2010 L. Ariza et al. Rapid community assessment of tungiasis developed for a variety parasitic diseases and health conditions, mainly in low-income countries (Anker 1991; Vlassoff & Tanner 1992; Macintyre 1999; Macintyre et al. 1999). For example, the macroscopic presence of haematuria (Lengeler et al. 1991, 2002a,b; Red Urine Study Group 1995), the identification of palpable nodules in the skin (Ngoumou et al. 1994; Whitworth & Gemade 1999; Kipp & Bamhuhiiga 2002) and the presence of elephantiasis and hydrocele (Gyapong et al. 1996, 1998a,b; Weerasooriya et al. 2008) have been used to estimate the prevalence of urinary schistosomiasis, onchocerciasis and lymphatic filariasis, respectively. Rapid assessment methods are commonly used to plan and monitor mass interventions, but also to detect parasitized individuals. Control of tungiasis at the community level has rarely been attempted (Heukelbach et al. 2001; Pilger et al. 2008), and rapid assessments methods are not available. Because in endemic areas 95–98% of sand flea lesions are restricted to the feet (Heukelbach et al. 2002, 2007a; Ugbomoiko et al. 2007), we assessed different topographic areas of the feet to be used as a rapid method for the presence of sand fleas. An area was identified that would give a reliable proxy to estimate prevalence of tungiasis. The occurrence of tungiasis on periungual sites of the toes was the most reliable and practical approach to estimate overall prevalence and severity of disease. Materials and methods Study areas We included data from 10 cross-sectional populationbased surveys conducted in five communities between 2001 and 2008. Three communities are located in Northeast Figure 1 Location of study areas (a) in Brazil (Ceará and Alagoas State) and (b) Nigeria (Lagos State). Brazil, two in Southwest Nigeria. The communities studied in Brazil were Balbino, a fishing village in Ceará State (Northeast Brazil); Morro do Sandras, an urban slum in the city of Fortaleza (capital of Ceará State); and Feliz Deserto, a rural community in Alagoas State. In Nigeria, data were collected in Yovoyan and Okunilaje, two small fishing villages in Lagos State (Southwest Nigeria, Figure 1). All five communities were characterized by low socioeconomic status, but showed distinct cultural and geographical characteristics. The study areas had in common that streets were not paved, and families were extremely poor (mean monthly family income equivalent to € 45.00). Illiteracy rates ranged between 15% and 30%. Whereas in Brazil, more than 90% of households had electric power supply, no access to electricity existed in the Nigerian communities. In Nigeria, the vast majority of houses were built of palm stems; and in Brazil, most houses were made of bricks or adobe. The main characteristics of the communities and their populations are depicted in Table 1. As tungiasis is known to show a particular seasonal variation (Heukelbach et al. 2005), data were collected in different periods of the year (dry and rainy season). In Nigeria, surveys were conducted during dry season only, as in the rainy season isolated communities are not accessible. In addition, according to key informants, tungiasis virtually does not occur in these communities during the heavy rain falls typical of this region in Nigeria. Detailed prevalence data on the Brazilian communities have been published previously (Wilcke et al. 2002; Muehlen et al. 2003; Heukelbach et al. 2005, 2007a). Clinical examinations were performed by investigators trained in an endemic area in Brazil and monitored by the same team leader. Field investigators were monitored Ceara Alagoas Lagos (a) (b) ª 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 857

- Page 69 and 70: Tabela 13: Verdadeiras prevalência

- Page 71 and 72: Figura 31: Gráfico de dispersão e

- Page 73 and 74: Tabela 14: Coeficiente de determina

- Page 75 and 76: Tabela 15: Prevalências da área p

- Page 77 and 78: Tabela 16: Prevalências gerais e g

- Page 79 and 80: Tais características identificadas

- Page 81 and 82: cujo comportamento do uso de chinel

- Page 83 and 84: As cargas parasitárias por indiví

- Page 85 and 86: tungíase, a desproporcional da car

- Page 87 and 88: pulgas em estágios iniciais, e sua

- Page 89 and 90: comunidades. A presença destas, si

- Page 91 and 92: Com esta área definida, basta insp

- Page 93 and 94: comunitários prévias à coleta de

- Page 95 and 96: 6 - CONCLUSÕES Epidemiologia da tu

- Page 97 and 98: CALLEGARI-JACQUES, S. M. Bioestatis

- Page 99 and 100: GIBBS, S. Skin disease and socioeco

- Page 101 and 102: HEUKELBACH, J.; SAHEBALI, S.; VAN M

- Page 103 and 104: MACINTYRE, K. Rapid assessment and

- Page 105 and 106: REMME, J. H. The African Programme

- Page 107 and 108: WEERASOORIYA, M. V.; ISOGAI, Y.; IT

- Page 109 and 110: APENDICE 1 108

- Page 111 and 112: APENDICE 2 110

- Page 113 and 114: 112

- Page 115 and 116: APÊNDICE 4 114

- Page 117 and 118: 9.1 AUTORIZACAO DO BAALES DAS COMUN

- Page 122 and 123: Tropical Medicine and International

- Page 124 and 125: Tropical Medicine and International

- Page 126 and 127: Tropical Medicine and International

- Page 128 and 129: Tropical Medicine and International

- Page 130 and 131: Table 1 Animals examined for tungia

- Page 132 and 133: Ariza, L cols pacientes com doença

- Page 134 and 135: Ariza, L cols de patologias clínic

- Page 136 and 137: Risk Factors for Tungiasis in Niger

- Page 138 and 139: Figure 1. Prevalence of tungiasis s

- Page 140 and 141: Table 1. Bivariate analysis of fact

- Page 142 and 143: Table 3. Population attributable fr

- Page 144 and 145: Heukelbach et al - Tungiasis in Ala

- Page 146 and 147: Heukelbach et al - Tungiasis in Ala

- Page 148 and 149: Heukelbach et al - Tungiasis in Ala

- Page 150 and 151: Heukelbach et al - Tungiasis in Ala

- Page 152 and 153: 456 Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de J

- Page 154 and 155: 458 Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de J

- Page 156 and 157: 460 Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de J

- Page 158 and 159: BMC Infectious Diseases BioMed Cent

- Page 160 and 161: 345&6'.%/-0,(1&701%#1%1%*))+,%!-&&.

- Page 162 and 163: 345&6'.%/-0,(1&701%#1%1%*))+,%!-&&.

- Page 164 and 165: 345&6'.%/-0,(1&701%#1%1%*))+,%!-&&.

- Page 166 and 167: 345&6'.%/-0,(1&701%#1%1%*))+,%!-&&.

- Page 168 and 169: The epidemiology of scabies in an i

Tropical Medicine and International Health volume 15 no 7 pp 856–864 july 2010<br />

L. Ariza et al. Rapid community assessment of tungiasis<br />

developed for a variety parasitic diseases and health<br />

conditions, mainly in low-income countries (Anker 1991;<br />

Vlassoff & Tanner 1992; Macintyre 1999; Macintyre et al.<br />

1999). For example, the macroscopic presence of haematuria<br />

(Lengeler et al. 1991, 2002a,b; Red Urine Study<br />

Group 1995), the identification of palpable nodules in the<br />

skin (Ngoumou et al. 1994; Whitworth & Gemade 1999;<br />

Kipp & Bamhuhiiga 2002) and the presence of elephantiasis<br />

and hydrocele (Gyapong et al. 1996, 1998a,b;<br />

Weerasooriya et al. 2008) have been used to estimate the<br />

prevalence of urinary schistosomiasis, onchocerciasis and<br />

lymphatic filariasis, respectively. Rapid assessment methods<br />

are commonly used to plan and monitor mass<br />

interventions, but also to detect parasitized individuals.<br />

Control of tungiasis at the community level has rarely been<br />

attempted (Heukelbach et al. 2001; Pilger et al. 2008), and<br />

rapid assessments methods are not available.<br />

Because in endemic areas 95–98% of sand flea lesions<br />

are restricted to the feet (Heukelbach et al. 2002, 2007a;<br />

Ugbomoiko et al. 2007), we assessed different topographic<br />

areas of the feet to be used as a rapid method for the<br />

presence of sand fleas. An area was identified that would<br />

give a reliable proxy to estimate prevalence of tungiasis.<br />

The occurrence of tungiasis on periungual sites of the toes<br />

was the most reliable and practical approach to estimate<br />

overall prevalence and severity of disease.<br />

Materials and methods<br />

Study areas<br />

We included data from 10 cross-sectional populationbased<br />

surveys conducted in five communities between 2001<br />

and 2008. Three communities are located in Northeast<br />

Figure 1 Location of study areas (a) in<br />

Brazil (Ceará and Alagoas State) and (b)<br />

Nigeria (Lagos State).<br />

Brazil, two in Southwest Nigeria. The communities studied<br />

in Brazil were Balbino, a fishing village in Ceará State<br />

(Northeast Brazil); Morro do Sandras, an urban slum in<br />

the city of Fortaleza (capital of Ceará State); and Feliz<br />

Deserto, a rural community in Alagoas State. In Nigeria,<br />

data were collected in Yovoyan and Okunilaje, two small<br />

fishing villages in Lagos State (Southwest Nigeria,<br />

Figure 1).<br />

All five communities were characterized by low socioeconomic<br />

status, but showed distinct cultural and geographical<br />

characteristics. The study areas had in common<br />

that streets were not paved, and families were extremely<br />

poor (mean monthly family income equivalent to € 45.00).<br />

Illiteracy rates ranged between 15% and 30%. Whereas in<br />

Brazil, more than 90% of households had electric power<br />

supply, no access to electricity existed in the Nigerian<br />

communities. In Nigeria, the vast majority of houses were<br />

built of palm stems; and in Brazil, most houses were made<br />

of bricks or adobe. The main characteristics of the<br />

communities and their populations are depicted in Table 1.<br />

As tungiasis is known to show a particular seasonal<br />

variation (Heukelbach et al. 2005), data were collected in<br />

different periods of the year (dry and rainy season). In<br />

Nigeria, surveys were conducted during dry season only, as<br />

in the rainy season isolated communities are not accessible.<br />

In addition, according to key informants, tungiasis virtually<br />

does not occur in these communities during the heavy<br />

rain falls typical of this region in Nigeria.<br />

Detailed prevalence data on the Brazilian communities<br />

have been published previously (Wilcke et al. 2002;<br />

Muehlen et al. 2003; Heukelbach et al. 2005, 2007a).<br />

Clinical examinations were performed by investigators<br />

trained in an endemic area in Brazil and monitored by<br />

the same team leader. Field investigators were monitored<br />

Ceara<br />

Alagoas<br />

Lagos<br />

(a) (b)<br />

ª 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 857