International Bulletin of Business Administration - EuroJournals

International Bulletin of Business Administration - EuroJournals

International Bulletin of Business Administration - EuroJournals

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Bulletin</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Business</strong> <strong>Administration</strong><br />

ISSN: 1451-243X<br />

Issue I<br />

June, 2006

INTERNATIONAL BULLETIN OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION<br />

http://www.eurojournals.com/BUSINESS.htm<br />

Editor-In-Chief<br />

Adrian M. Steinberg, Wissenschaftlicher Forscher<br />

Editorial Advisory Board<br />

M. Femi Ayadi, University <strong>of</strong> Houston-Clear Lake<br />

Jwyang Jiawen Yang, The George Washington University<br />

Emanuele Bajo, University <strong>of</strong> Bologna<br />

Constantinos Vorlow, University <strong>of</strong> Durham<br />

Zhihong Shi, State University <strong>of</strong> New York<br />

Jan Dutta, Rutgers University<br />

Maria Elena Garcia-Ruiz, University <strong>of</strong> Cantabria<br />

Christos Giannikos, Columbia University<br />

Emmanuel Anoruo, Coppin State University<br />

H. Young Baek, Nova Southeastern University<br />

Wen-jen Hsieh, National Cheng Kung University<br />

George Skoulas, University <strong>of</strong> Macedonia<br />

Mahdi Hadi, Kuwait University<br />

David Wang, Hsuan Chuang University<br />

Stylianos Karagiannis, Center <strong>of</strong> Planning and Economic Research<br />

John Mylonakis, Tutor - Hellenic Open University<br />

Athanasios Koulakiotis, University <strong>of</strong> the Aegean<br />

Basel M. Al-Eideh, Kuwait University<br />

Gregorio Giménez Esteban, Universidad de Zaragoza<br />

Mukhopadhyay Bappaditya, Management Development Institute<br />

Katerina Lyroudi, University <strong>of</strong> Macedonia<br />

Narender L. Ahuja, Institute for Integrated Learning in Management<br />

Amita Mital, Xavier Labour Relations Institute<br />

Wassim Shahin, Lebanese American University<br />

M. Carmen Guisan, University <strong>of</strong> Santiago de Compostela<br />

Zulkarnain Muhamad Sori, University Putra Malaysia<br />

Syrous Kooros, Nicholls State University<br />

Indexing / Abstracting<br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Bulletin</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Business</strong> <strong>Administration</strong> is indexed in Scopus, Elsevier Bibliographic<br />

Databases, EMBASE, Ulrich, DOAJ, Cabell, Compendex, GEOBASE, and Mosby.

Aims and Scope<br />

The <strong>International</strong> <strong>Bulletin</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Business</strong> <strong>Administration</strong> is a quarterly, peer-reviewed international<br />

research journal that addresses both theoretical and practical issues in the areas <strong>of</strong> accounting, finance,<br />

economics, business technology, business education, marketing, management and business law. The<br />

journal provides a pr<strong>of</strong>essional outlet for scholarly works. Articles selected for publication provide<br />

valuable insight into matters <strong>of</strong> broad intellectual and practical concern to academicians and business<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essionals. The goal <strong>of</strong> the journal is to broaden the knowledge <strong>of</strong> both academicians and<br />

practitioners by promoting access to business-related research and ideas.<br />

Editorial Policies<br />

1) The journal realizes the meaning <strong>of</strong> fast publication to researchers, particularly to those working in<br />

competitive & dynamic fields. Hence, it <strong>of</strong>fers an exceptionally fast publication schedule including<br />

prompt peer-review by the experts in the field and immediate publication upon acceptance. It is the<br />

major editorial policy to review the submitted articles as fast as possible and promptly include them in<br />

the forthcoming issues should they pass the evaluation process.<br />

2) All research and reviews published in the journal have been fully peer-reviewed by two, and in some<br />

cases, three internal or external reviewers. Unless they are out <strong>of</strong> scope for the journal, or are <strong>of</strong> an<br />

unacceptably low standard <strong>of</strong> presentation, submitted articles will be sent to peer reviewers. They will<br />

generally be reviewed by two experts with the aim <strong>of</strong> reaching a first decision within a two-month<br />

period. Suggested reviewers will be considered alongside potential reviewers identified by their<br />

publication record or recommended by Editorial Board members. Reviewers are asked whether the<br />

manuscript is scientifically sound and coherent, how interesting it is and whether the quality <strong>of</strong> the<br />

writing is acceptable. Where possible, the final decision is made on the basis that the peer reviewers are<br />

in accordance with one another, or that at least there is no strong dissenting view.<br />

3) In cases where there is strong disagreement either among peer reviewers or between the authors and<br />

peer reviewers, advice is sought from a member <strong>of</strong> the journal's Editorial Board. The journal allows a<br />

maximum <strong>of</strong> three revisions <strong>of</strong> any manuscripts. The ultimate responsibility for any decision lies with<br />

the Editor-in-Chief. Reviewers are also asked to indicate which articles they consider to be especially<br />

interesting or significant. These articles may be given greater prominence and greater external<br />

publicity.<br />

4) Any manuscript submitted to the journals must not already have been published in another journal or<br />

be under consideration by any other journal. Manuscripts that are derived from papers presented at<br />

conferences can be submitted even if they have been published as part <strong>of</strong> the conference proceedings in<br />

a peer reviewed journal. Authors are required to ensure that no material submitted as part <strong>of</strong> a<br />

manuscript infringes existing copyrights, or the rights <strong>of</strong> a third party. Contributing authors retain<br />

copyright to their work.<br />

5) The journal makes all published original research immediately accessible through<br />

www.<strong>EuroJournals</strong>.com without subscription charges or registration barriers. Through its open access<br />

policy, the journal is committed permanently to maintaining this policy. This process is streamlined<br />

thanks to a user-friendly, web-based system for submission and for referees to view manuscripts and<br />

return their reviews. The journal does not have page charges, color figure charges or submission fees.<br />

However, there is an article-processing and publication fee payable only if the article is accepted for<br />

publication.<br />

Submissions<br />

All papers are subjected to a blind peer review process. Manuscripts are invited from academicians,<br />

research students, and scientists for publication consideration. The journal welcomes submissions in all

areas related to science. Each manuscript must include a 200 word abstract. Authors should list their<br />

contact information on a separate paper. Electronic submissions are acceptable. The journal publishes<br />

both applied and conceptual research.<br />

Articles for consideration are to be directed to the editor through business@eurojournals.com. In the<br />

subject line <strong>of</strong> your e-mail please write "IBBA submission"<br />

� Articles are accepted in MS-Word or pdf formats<br />

� Contributors should adhere to the format <strong>of</strong> the journal.<br />

� All correspondence should be directed to the editor<br />

� There is no submission fee<br />

� Publication fee for each accepted article is $150 USD<br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Bulletin</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Business</strong> <strong>Administration</strong> is published in the United States <strong>of</strong> America at Lulu<br />

Press, Inc (Morrisville, North Carolina) by <strong>EuroJournals</strong>, Inc.

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Bulletin</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Business</strong> <strong>Administration</strong><br />

Issue I<br />

June, 2006<br />

Contents<br />

Social Identity Enhancement Strategies Used in the Workplace 6-14<br />

Craig R. Erwin<br />

Keeping the Wheels <strong>of</strong> the South African Automotive Industry Turning: Challenges<br />

Facing Exporters within the Automotive Component Manufacturing Industry 15-24<br />

Micheline Naude<br />

Size and Book-to-Market Risk Factors in Earnings and Returns for the Greek Stock Market 25-41<br />

Grigoris Michailidis, Stavros Tsopoglou and Demetrios Papanastasiou<br />

<strong>Business</strong> Performance Measurement Frameworks and SMEs 42-47<br />

George Ntalakas, Athanassios Mihiotis and John Mylonakis<br />

The Effects <strong>of</strong> Emotional Intelligence On Leader Impression Management and Group<br />

Satisfaction 48-64<br />

David E. Gundersen and Elizabeth J. Rozell<br />

Managing Mobile Commerce Quality: A Long Way to Run 65-74<br />

Emmanouil Stiakakis<br />

Description <strong>of</strong> Growth Price Model in a Random Environment 75-81<br />

Basel M. Al-Eideh<br />

Multicultural analysis on social influence and purchasing decision: East vs. West 82-91<br />

Kritika Kongsompong<br />

Acquisition Announcements, Firm Value and Volatility: The Case <strong>of</strong> Greek Financial Firms 92-102<br />

Athanasios Koulakiotis, Nicholas Papasyriopoulos and Apostolos Dasilas<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong> EMBA Students in AACSB Accredited Public and Private Institutions in the<br />

United States 103-108<br />

John Coleman, Stan Bazan, and Fred Tesch<br />

The Import Problem and How Companies Operating in the United States Should Address<br />

the Challenge 109-114<br />

Scott D. Goldberg<br />

Applying Benchmarking Practices in Small Companies: An Empirical Approach 115-126<br />

Emmanouil Stiakakis and Ioannis Kechagioglou<br />

An Empirical Analysis <strong>of</strong> The Federal Emergency Management Agency 127-134<br />

G.S. Osho, M.O. Adams, R.N. Jones and I.D. Onwudiwe

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Bulletin</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Business</strong> <strong>Administration</strong><br />

ISSN: 1451-243X Issue 1 (2006)<br />

© <strong>EuroJournals</strong>, Inc. 2006<br />

http://www.eurojournalsn.com<br />

Social Identity Enhancement Strategies<br />

Used in the Workplace<br />

Craig R. Erwin<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>Business</strong> <strong>Administration</strong><br />

Eastern Connecticut State University, 83 Windham Street, Willimantic, CT 06226<br />

E-mail: erwinc@easternct.edu<br />

Abstract<br />

Social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner, 1986) contends that higher-status employees<br />

(e.g., nonminorities) use a status maintenance strategy to enhance their social identities<br />

whereas lower-status employees such as women and minorities use various strategies (e.g.,<br />

social creativity, social mobility and social competition) to enhance their social identities. I<br />

propose to test part <strong>of</strong> a model that Chattopadhyay, Tluchowska, and George (2004)<br />

developed based on social identity theory and a related theory, self-categorization theory<br />

(Turner, 1987). I provide a brief review <strong>of</strong> the literature on social identity and relational<br />

demography and propose testable hypotheses to determine the extent to which social<br />

identity enhancement strategies are used in the workplace and whether women and<br />

minorities tend to identify more with their workgroups, with nonminorities, or with<br />

demographically similar people. The study seeks to determine the extent to which women,<br />

minorities and nonminorities attempt to enhance their social identities in the workplace. I<br />

outline methods that I will use to test the hypotheses and discuss possible implications <strong>of</strong><br />

the study.<br />

Key words: Diversity, workgroup, team, social identity, minority, gender<br />

I. Introduction<br />

Organizations and the groups within them are becoming increasingly diverse as they mirror society and<br />

as organizations strive to provide employment and advancement opportunities for women and<br />

minorities. As a result, organizations and groups must consider how best to draw on the various skills<br />

and capabilities <strong>of</strong> a diverse workforce and minimize friction and miscommunication. Social identity<br />

theory (Tajfel and Turner, 1986) holds that individuals use a strategy called social categorization to<br />

cope with a complex environment. Social categorization is the process by which people categorize<br />

themselves and others based on salient demographic characteristics such as sex and race. Social<br />

categorization enables individuals to identify with others like themselves, satisfying a need for<br />

affiliation. It also allows them to develop and maintain a positive social identity (Tajfel and Turner,<br />

1986). This study tackles the following research question: To what extent do women, minorities and<br />

nonminorities attempt to enhance their social identities in the workplace?<br />

II. Literature Review<br />

Although diverse teams are believed to have some advantages over homogeneous teams, some have<br />

observed that too <strong>of</strong>ten diverse teams tend to underperform (Elsass and Graves, 1997). Social

categorization processes, which consist <strong>of</strong> group members evaluating themselves and other members<br />

based on salient demographic characteristics, may adversely affect group processes, communication,<br />

and outcomes as well as relationships in the group. Tajfel and Turner (1986) developed social identity<br />

theory to describe the mechanism <strong>of</strong> social categorization. Turner (1987) extended the theory to<br />

produce self-categorization theory. With these two theories Tajfel and Turner attempt to describe the<br />

process by which women and minorities label themselves and are labeled by non-minority group<br />

members based on salient demographic characteristics. Social identity theory posits that individuals<br />

possess a social identity based on their membership in socially distinct groups (e.g., gender, ethnicity,<br />

and pr<strong>of</strong>ession). Social- categorization theory suggests that individuals use visible and salient features<br />

(e.g., skin color) associated with socially distinct groups to categorize each other. The labels or<br />

categories affect group communication and group member behavior and interactions. Tajfel and<br />

Turner suggest that self-categorization is used by individuals to help them maintain and improve their<br />

self-images. Chattopadhyay, Tluchchowska, and George (2004) developed a model which describes<br />

how individuals use various strategies to help them achieve their personal goals in the workplace.<br />

Chattopadhyay et al. contend that social categorization is likely to be conducted based on race and sex<br />

because Bargh’s (1999) literature review revealed that race and gender-based stereotypes are<br />

widespread and greatly affect individual thoughts, views and actions toward others.<br />

By and large, in the past, white and male employees have enjoyed higher status, better job.s, higher<br />

pay, and better employment and advancement opportunities than women and minorities (e.g., Amott &<br />

Matthaei, 1991). Although this has begun to change in recent decades, such patterns are unlikely to<br />

reverse themselves quickly and easily. However, the demographic diversity <strong>of</strong> workers in<br />

organizations is increasing (e.g. Williams and O'Reilly, III, 1998). Understandably, women and<br />

minorities are anxious to see systems and norms revoked that have frustrated the achievement <strong>of</strong> their<br />

vocational goals. In contrast, white and male employees are reluctant to give up their preferred status,<br />

let alone to accept a role-reversal in which women and minorities are given preferential treatment.<br />

Although workgroups are likely to become increasingly diverse as workplaces become more<br />

diverse, this trend will not be embraced by all employees. White males will be threatened by increasing<br />

workplace and workgroup diversity as they become outnumbered by women and minorities. White<br />

males will perceive that the status and benefits that they have enjoyed are likely to be taken away and<br />

conferred on others. As a result, white males are likely to develop coping strategies to help them deal<br />

with changes in workplace and workgroup diversity. One strategy likely to be used is to attempt to<br />

maintain the status quo, keeping the prestige and benefits that white and male employees have<br />

traditionally had.<br />

Hypothesis 1. White and male employees are more likely than women and minority employees to prefer<br />

the status quo.<br />

In general, such comparisons favoring the in-group over the outgroup are easier to make for white<br />

and male employees, because they have traditionally been accorded higher status in organizations than<br />

minority and female employees--a practice that continues in organizations today (e.g., Amott &<br />

Matthaei, 1991). The categories "white" and "male" thus may be associated with higher value in<br />

organizations than the categories "minority" and "female."<br />

White and male employees will then tend to identify with their own demographic categories,<br />

because that will facilitate the enhancement <strong>of</strong> their social identity. This is referred to as a status<br />

maintenance strategy, since it is associated with higher-status employees holding on to their status. I<br />

note that this tendency to use a status maintenance strategy may, in turn, further reinforce sex and race<br />

as salient bases <strong>of</strong> categorization in an organizational context.<br />

Given that white and male employees have traditionally received better treatment and greater<br />

resources and rewards than women and minorities, they have an incentive to stick together and to keep<br />

from being lost in the crowd. If white and male employees band together, they may be able to stem the

tide, continuing to maintain the status quo. If, however, white and male employees are divided and<br />

conquered, they will have no more power or prestige than any other category.<br />

It is highly likely that white and male employees will identify with other white and male employees.<br />

They share a number <strong>of</strong> bonds. It is they that have worked, socialized and made up the in-group for<br />

centuries. They also have highly visible characteristics in common. Hogg and Terry (2000) claim that<br />

employees in the in-group (e.g., white males) may identify with others like themselves if they tend to<br />

have qualities thought to be more desireable. Ellemers, Kortekaas, & Ouwerkerk (1999) claim that<br />

white and male employees who identify with others <strong>of</strong> the same gender and sex are likely to be<br />

committed and emotionally involved with their demographic category. They are also likely to believe<br />

that members <strong>of</strong> their demographic category are all in the same boat and destined to end up in the same<br />

way (Ashforth & Mael, 1989).<br />

Hypothesis 2. The more diverse the workgroup, the less that white and male employees will identify<br />

with their workgroup.<br />

Hypothesis 3. The more diverse a workgroup becomes, the more that male employees with identify with<br />

other male employees.<br />

Hypothesis 4. The more diverse a workgroup becomes, the more non-minorities will identify with other<br />

non-minorities.<br />

Male employees are used to having a variety <strong>of</strong> advantages in the workplace. They have<br />

traditionally been in charge, had better access to resources, had better opportunities for advancement<br />

and been viewed as having higher status than female employees. Male employees have nothing to gain<br />

and much to lose if they lose their place in the sun. Understandably, they tend to stick together and<br />

have similar views and ways <strong>of</strong> doing things. Male employees have difficulty empathizing with female<br />

and minority employees because they have never been in their situation. Male employees embrace<br />

tradition and resist change because they have nothing to gain from change. As such, they prefer<br />

homogeneous groups to diverse groups, prefer to work with others like themselves, and prefer to<br />

maintain the status quo. Male employees tend to be uncomfortable in diverse workgroups, avoiding<br />

them if possible and clinging to other men. As such, male employees are unlikely to feel at home in<br />

diverse workgroups or to embrace such groups and their goals.<br />

It is likely that males will attempt to protect current systems and practices, viewing any efforts to<br />

change the status quo as threatening (e.g., Brown, 1984). Researchers have found that members <strong>of</strong> a<br />

group in power may take extraordinary steps to maintain power and are likely to hold negative views<br />

<strong>of</strong> those attempting to make changes (e.g., Kanter, 1993).<br />

Women and minority employees are likely to be more open-minded than male employees whether<br />

for pragmatic or other reasons. In order to make their way into workplaces dominated by white males,<br />

women and minorities have had to be flexible, creative, persistent and collaborative. As a result,<br />

women and minority employees tend to be better team players, more adaptable and more accepting<br />

than male employees. In order to gain entry to organizations and enjoy rewarding careers, women and<br />

minority employees have had to accept treatment and outcomes that male employees would never have<br />

tolerated. In many cases, female and minority employees had to adopt views, styles and manners <strong>of</strong><br />

those in charge (e.g., white males) if they wanted to get and keep jobs and advance. As a result, female<br />

and minority employees are capable <strong>of</strong> understanding and accepting the views and ways <strong>of</strong> male<br />

employees. They are also better team players, tending to put the team and its goals ahead <strong>of</strong> their own<br />

agendas, goals and egos.<br />

Hypothesis 5. Female employees are more likely to ID with male employees than male employees are<br />

to identify with female employees.

Hypothesis 6. In diverse workgroups female and minority employees are more likely than white and<br />

male employees to identify with their workgroups.<br />

III. Methods<br />

I developed a questionnaire (see Appendix 1) by making slight modifications to existing scales. The<br />

questionnaire combines several measures which have been tested previously for validity and reliability.<br />

I modified a social dominance scale from Sidanius & Pratto (1999), a pro-male bias scale from<br />

Tougas, Brown, Beaton, and St. Pierre (1999), a group identification scale developed by Brown,<br />

Condor, Mathews, Wade and Williams (1986), and Luhtanen’s (1990) collective self-esteem scale. In<br />

addition, I developed a workgroup diversity scale. I also included additional items as necessary to<br />

measure demographic characteristics <strong>of</strong> the respondent.<br />

The published scales measure individuals’ beliefs or tendencies. The social dominance scale<br />

measures whether individuals prefer to maintain or change the existing social order. The pro-male bias<br />

scale measures whether individuals believe that one gender tends to be more competent or qualified<br />

than the other. The group identification scale seeks to determine the extent to which an individual<br />

identifies with his or her workgroup. The collective self-esteem scale was used to measure both the<br />

extent to which a respondent identifies with his or her own ethnic group and with his or her own<br />

gender. Finally, the workgroup diversity scale measures how diverse a respondent’s workgroup is<br />

along the dimensions <strong>of</strong> age, tenure with the workgroup, gender, ethnicity, and education.<br />

I tested the questionnaire on colleagues and students and then revised it to minimize confusion and<br />

address various shortcomings. I used a snowball sample by having my students ask colleagues in their<br />

workplaces or employed friends to complete questionnaires. Ninety-nine questionnaires were<br />

completed and returned. The data from the completed questionnaires is to be entered into a<br />

spreadsheet so that it can be analyzed using SPSS. ANOVA’s are to be conducted to compare means<br />

and linear regressions will be run to test the strength <strong>of</strong> hypothesized relationships.<br />

IV. Results<br />

Scholars, managers, Human Resource pr<strong>of</strong>essionals, and executives in multinational corporations can<br />

best benefit from this study. They can gain a better understanding <strong>of</strong> strategies used by male, female<br />

and minority employees to enhance their social identities. The results <strong>of</strong> this study should help<br />

advance knowledge <strong>of</strong> diversity in organizations and <strong>of</strong> strategies used in the workplace to enhance<br />

social identity.<br />

Although much research has been conducted on diversity in organizations, the focus has been on the<br />

behavior <strong>of</strong> women and minorities. This study also examines the behavior <strong>of</strong> white males. The study<br />

can help determine if there are important differences in strategies used by various individuals in the<br />

workplace. If employees are devoting time and effort to strategies intended to enhance their social<br />

identities, productivity may suffer.<br />

Managers with a need to know what they must consider as they expand, hire employees, and form<br />

teams can benefit from this study. They can learn how to strengthen their teams and organizations and<br />

increase employee morale, and team effectiveness and cohesiveness.<br />

V. Discussion<br />

It is likely to be difficult for a group to reach its potential if some members fail to identify with the<br />

group. If an individual identifies with her workgroup, she is more likely to exhibit positive attitudes<br />

and behaviors toward the group (Tsui, Egan, & O'Reilly, 1992) and to be a productive member. The<br />

extent to which employees perceive that they are different from colleagues may affect organizational<br />

outcomes such as absenteeism and turnover (Tsui, Egan, & O'Reilly, 1992). Identification with a

group influences group outcomes, such as cooperation, altruism, cohesion, and evaluation <strong>of</strong> the group<br />

(Turner, 1982), as well as one’s loyalty to and pride in the group (Ashforth & Mael, 1989). Although<br />

diverse teams are believed to have some advantages over homogeneous teams, they <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

underperform (Elsass and Graves, 1997). At the same time that workplace diversity and diversity in<br />

society at large are increasing, political pressure is increasing to reduce societal diversity through<br />

tougher border controls and immigration law reforms. Decades after passage <strong>of</strong> the Civil Rights Act,<br />

even though workplace diversity has increased sharply, women and minorities are still<br />

underrepresented in areas such as upper management. Although we know that many women and<br />

minorities successfully join organizations and advance, we know little about strategies that they and<br />

nonminorities employ to maintain or change the status quo and if such strategies are successful.<br />

Whether or not women and minorities are treated fairly and given equal opportunities and rewards,<br />

it is their perception that will drive their behaviors. If they perceive that all employees receive equal<br />

treatment and opportunities, their behavior will reflect it. They will feel less need to pursue strategies<br />

to enhance their social identities. This will result in more productive teams and individuals better able<br />

to cooperate and share information and less in need <strong>of</strong> devoting time to personal needs. If employers<br />

better understand their employees and workgroups, including strategies used to change or maintain the<br />

status quo, they can develop better hiring and promotion practices, provide more effective training, and<br />

form and nurture more effective and efficient groups.<br />

It is important to understand the extent to which an employee identifies with various individuals and<br />

groups. Scholars claim that employee attitudes and behaviors are affected by the degree to which<br />

employees identify with their workgroups (e.g., Tsui, Egan, & O'Reilly, 1992). Researchers have found<br />

that identification with a workgroup is related to positive attitudes and behaviors toward the group<br />

(e.g., Tsui et al., 1992). It seems reasonable that individuals who are emotionally attached to their<br />

workgroup, feel that they belong in the group, are concerned about the group’s goals and outcomes are<br />

more likely to exhibit positive behaviors and attitudes toward the group (Tsui et al., 1992).<br />

This study is important because, decades after passage <strong>of</strong> the Civil Rights Act, women and<br />

minorities are still underrepresented in upper management. This study will investigate strategies that<br />

women and minorities employ to deal with workplace barriers to entry and advancement and the<br />

strategies that nonminorities use to maintain the status quo. As the 21 st century marches on, it is<br />

important for employers to understand how their employees see themselves, adopt values and attempt<br />

to fit in and advance. Scholars believe that the extent to which employees perceive that they are<br />

different from colleagues may affect organizational outcomes such as absenteeism and turnover<br />

intentions (Tsui, Egan, & O'Reilly, 1992). This study will shed light on methods used by minorities<br />

and nonminorities to deal with workplace diversity and disparities.<br />

VI. References<br />

[1] Amott, T., & Matthaei, J. 1991. Race, gender and work. Boston: South End.<br />

[2] Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. 1989. Social identity theory and the organization. Academy <strong>of</strong><br />

Management Review, 14: 20-39.<br />

[3] Bargh, J. A. 1999. The cognitive monster: The case against the controllability <strong>of</strong> automatic<br />

stereotype effects. In S. Chaiken & Y. Trope (Eds.), Dual-process theories in social<br />

psychology: 361-382. New York: Guilford Press.<br />

[4] Brown, R. 1984. The effects <strong>of</strong> intergroup similarity and cooperative vs. competitive<br />

orientation on intergroup discrimination. British Journal <strong>of</strong> Social Psychology, 23: 21-33.<br />

[5] Chattopadhyay, P., Tluchowska, M. & George, E. 2004. Identifying the ingroup: A closer look<br />

at the influence <strong>of</strong> demographic dissimilarity on employee social identity. Academy <strong>of</strong><br />

Management Review, 29(2): 180-202.<br />

[6] Ellemers, N., Kortekaas, P., & Ouwerkerk, J. W. 1999. Self-categorisation, commitment to the<br />

group and group self-esteem as related but distinct aspects <strong>of</strong> social identity. European Journal<br />

<strong>of</strong> Social Psychology, 29: 371-389.

[7] Elsass, P.M., & Graves, L.M. (1997). Demographic diversity in decision-making groups: The<br />

experiences <strong>of</strong> women and people <strong>of</strong> color. Academy <strong>of</strong> Management Review, 22: 946-973.<br />

[8] Hogg, M. A., & Terry, D. J. 2000. Social identity and self-categorization processes in<br />

organizational contexts. Academy <strong>of</strong> Management Review, 25: 121-140.<br />

[9] Kanter, R. M. 1993. Men and women <strong>of</strong> the corporation. New York: Basic Books.<br />

[10] Tajfel, H., & Turner, J.C. (1986). The social identity theory <strong>of</strong> intergroup behavior. In S.<br />

Worchel and W.G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology <strong>of</strong> Intergroup Relations. Chicago, IL: Nelson-<br />

Hall.<br />

[11] Tsui, A., Egan, T., & O'Reilly, C. A., III. 1992. Being different: Relational demography and<br />

organizational attachment. Administrative Science Quarterly, 37: 549-579.<br />

[12] Turner, J. C. 1987. A self-categorization theory. In M. Hogg, P. Oakes, S. Reicher, & M. S.<br />

Wetherell (Eds.), Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory: 42 67. Oxford:<br />

Blackwell.<br />

[13] Williams, K., & O'Reilly, III, C. (1998). Demography and diversity in organizations: A review<br />

<strong>of</strong> 40 years <strong>of</strong> research. Research in Organizational Behavior, 20, 77-140.<br />

Appendix 1 - Questionnaire<br />

Strongly Mostly Unsure Mostly Strongly<br />

Disagree Disagree Agree Agree<br />

1. This country would be better <strong>of</strong>f if we cared 1 2 3 4 5<br />

less about how equal all people were.<br />

2. If people were treated more equally we would 1 2 3 4 5<br />

have fewer problems in the country.<br />

3. It really is not a problem if some people have 1 2 3 4 5<br />

more <strong>of</strong> a chance in life.<br />

4. This country would be better <strong>of</strong>f if inferior 1 2 3 4 5<br />

groups stayed in their place.<br />

5. We have gone too far in pushing equal rights 1 2 3 4 5<br />

in this country.<br />

6. We should strive for increased social equality 1 2 3 4 5<br />

between groups.<br />

______________________________________________________________________________<br />

B. The following statements deal with how you view people in your workplace. Please circle the<br />

appropriate number from 1 to 5.<br />

Strongly Mostly Unsure Mostly Strongly<br />

Disagree Disagree Agree Agree<br />

7. In my organization, women in management 1 2 3 4 5<br />

have the necessary qualifications to do their work.<br />

8. In my organization, men in management have 1 2 3 4 5<br />

the necessary qualifications to do their work.<br />

9. In my organization, women are competent in 1 2 3 4 5<br />

general.<br />

10. In my organization, men are competent in general. 1 2 3 4 5<br />

______________________________________________________________________________

C. The following statements deal with how you feel about your workgroup. Your workgroup is<br />

the group at your workplace which you most feel a part <strong>of</strong>. Your workgroup might be your shift,<br />

department, assembly line, crew, or project team. Or it might be a supervisory, management, or<br />

executive team if you are a supervisor, manager, or executive. Typically you would interact with<br />

members <strong>of</strong> your workgroup frequently and share common resources and goals. In a very small<br />

organization, your workgroup might consist <strong>of</strong> everyone in the organization. If you are a<br />

member <strong>of</strong> more than one workgroup, focus only on the group you feel you belong to most.<br />

Please circle the appropriate number from 1 to 5.<br />

Strongly Mostly Unsure Mostly Strongly<br />

Disagree Disagree Agree Agree<br />

11. I am a person who considers my workgroup 1 2 3 4 5<br />

important.<br />

12. I am a person who identifies with my workgroup. 1 2 3 4 5<br />

13. I am a person who feels strong ties with my 1 2 3 4 5<br />

workgroup.<br />

14. I am a person who is glad to belong to my 1 2 3 4 5<br />

workgroup.<br />

15. I am a person who sees myself as belonging to 1 2 3 4 5<br />

my workgroup.<br />

16. I am a person who makes excuses for belonging 1 2 3 4 5<br />

to my workgroup.<br />

17. I am a person who tr ies to hide belonging to my 1 2 3 4 5<br />

workgroup.<br />

18. I am a person who feels held back by my 1 2 3 4 5<br />

workgroup.<br />

19. I am a person who is annoyed to say I’m a 1 2 3 4 5<br />

member <strong>of</strong> my workgroup.<br />

20. I am a person who criticizes my workgroup. 1 2 3 4 5<br />

21. All <strong>of</strong> the people in my workgroup are close to 1 2 3 4 5<br />

the same age.<br />

22. The ages <strong>of</strong> the people in my workgroup vary 1 2 3 4 5<br />

greatly.<br />

23. Everyone in my workgroup has been in the 1 2 3 4 5<br />

group for about the same number <strong>of</strong> years.<br />

24. Some <strong>of</strong> the people in my workgroup have been in 1 2 3 4 5<br />

the group for many more years than others.<br />

25. All <strong>of</strong> the people in my workgroup have the 1 2 3 4 5<br />

same gender.<br />

26. My workgroup is about 50% men and 50% women. 1 2 3 4 5<br />

27. All <strong>of</strong> the people in my workgroup have the 1 2 3 4 5<br />

same ethnic background.<br />

28. My workgroup has people with many different 1 2 3 4 5<br />

ethnic backgrounds.<br />

29. All <strong>of</strong> the people in my workgroup have about 1 2 3 4 5<br />

the same educational background.<br />

30. The educational backgrounds <strong>of</strong> the people in my 1 2 3 4 5<br />

workgroup vary a great deal.

D. Please answer the following questions about your workgroup by circling the appropriate<br />

response.<br />

31. How long have you been a member <strong>of</strong> your workgroup (circle one)?<br />

Under 1 year 1-2 years 3-5 years 6-10 years Over 10 years<br />

32. How many people are in your workgroup (circle one)?<br />

1-2 people 3-5 people 6-10 people 11-20 people Over 20 people<br />

______________________________________________________________________________<br />

E. The following statements deal with your ethnicity. Please circle the appropriate number from<br />

1 to 5.<br />

Strongly Mostly Unsure Mostly Strongly<br />

Disagree Disagree Agree Agree<br />

33. Overall, my ethnicity has very little to do with 1 2 3 4 5<br />

how I feel about myself.<br />

34. My ethnicity is an important reflection <strong>of</strong> who 1 2 3 4 5<br />

I am.<br />

35. My ethnicity is unimportant to my sense <strong>of</strong> 1 2 3 4 5<br />

what kind <strong>of</strong> a person I am.<br />

36. In general, my ethnicity is an important part 1 2 3 4 5<br />

<strong>of</strong> my self image.<br />

______________________________________________________________________________<br />

F. The following statements deal with your gender. Please circle the appropriate number from 1<br />

to 5.<br />

Strongly Mostly Unsure Mostly Strongly<br />

Disagree Disagree Agree Agree<br />

37. Overall, my gender has very little to do with 1 2 3 4 5<br />

how I feel about myself.<br />

38. My gender is an important reflection <strong>of</strong> who 1 2 3 4 5<br />

I am.<br />

39. My gender is unimportant to my sense <strong>of</strong> 1 2 3 4 5<br />

what kind <strong>of</strong> a person I am.<br />

40. In general, my gender is an important part 1 2 3 4 5<br />

<strong>of</strong> my self image.<br />

______________________________________________________________________________

G. Almost finished. This section asks you to provide some information about yourself. This<br />

questionnaire never asks your name. Please provide the information requested below.<br />

41. Your age: under 18_____ 18-25 _____ 26-40_____<br />

41-55 _____ Over 55 _____<br />

42. Your gender: Male_________ Female________<br />

43. Your ethnicity: Hispanic________ African American ________ `<br />

Asian/Pacific Island ________ Native American ________<br />

Caucasian_________ Other (Specify)____________________<br />

44. Marital Status: Never married _____ Married ______ Widowed_______<br />

Divorced ______ Separated ______<br />

45. Highest Educational Level Completed:<br />

Didn’t finish high school__________ Finished high school _______<br />

Associates_________<br />

Bachelors __________ Masters _________ Doctoral_________<br />

46. Where were you born? In the U.S._______ Outside the U.S.________<br />

47. Was one or more <strong>of</strong> your parents born outside the U.S.? Yes____ No____<br />

Unsure____<br />

48. Do you consider yourself to be: Religious?____ Spiritual?____ Unsure?_____<br />

49. Your position with your primary employer (check all that apply):<br />

Employee_______ Supervisor_______ Manager________<br />

Owner_______ Executive_______ Other (specify)___________________________

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Bulletin</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Business</strong> <strong>Administration</strong><br />

ISSN: 1451-243X Issue 1 (2006)<br />

© <strong>EuroJournals</strong>, Inc. 2006<br />

http://www.eurojournalsn.com<br />

Keeping the Wheels <strong>of</strong> the South African Automotive Industry<br />

Turning: Challenges Facing Exporters within the Automotive<br />

Component Manufacturing Industry<br />

Micheline Naude<br />

School <strong>of</strong> Management<br />

University <strong>of</strong> KwaZulu-Natal<br />

Private Bag X01<br />

Scottsville 3207, Pietermaritzburg<br />

e-mail: naudem@ukzn.ac.za<br />

naudem@ukzn.ac.za<br />

Abstract<br />

The South African automotive component industry faces huge challenges in a very<br />

competitive global market. There are, however, also significant opportunities, which for<br />

the purpose <strong>of</strong> this research paper are briefly highlighted. However, the primary focus is<br />

the challenges facing South African exporters with special reference to selected subsectors.<br />

The challenges have been approached from a supply chain perspective only.<br />

This research paper includes a combination <strong>of</strong> literature review, interviews with<br />

managers in the selected sub-groups and questionnaires that have been sent out to<br />

determine the challenges facing automotive component exporters. The outcome <strong>of</strong> the<br />

empirical research to establish these challenges will then be dealt with, together with the<br />

findings with regard to the identified challenges. Recommendations on how to address<br />

these in order to establish a competitive advantage as well as the limitations <strong>of</strong> the research<br />

and suggestions for further research will be discussed.<br />

Key words: OEMs, automotive component industry, competitive advantage, globilisation,<br />

South African motor industry, MIDP, IRCCs, exports, challenges, continuous<br />

improvement.<br />

I. Introduction<br />

A major transformation in the global economy has been taking place. Globalisation has increased the<br />

scope <strong>of</strong> opportunities for well-established industries such as among others; the textile,<br />

communications, automotive, computers and semi-conductors industry. In the past, national economies<br />

were comparatively isolated from each other. Distance, time zones, language, national differences in<br />

government regulations, culture and business systems also isolated national economies. Today, there is<br />

a movement towards a world in which national economies are merging into a mutually dependent<br />

global economic system, commonly referred to as globalisation (Hill, 2001:4).<br />

Because <strong>of</strong> globalisation, international competition has increased performance standards in many<br />

facets, for example cost, quality, service, dependability, flexibility, productivity and time compression.<br />

Consequently, companies are finding that they must develop global management expertise in order to<br />

compete successfully in global markets. In the 21 st century, competitiveness will be achieved only by<br />

those capable <strong>of</strong> not just meeting but exceeding global standards. Furthermore, it must be noted that

global standards are not fixed but require continuous improvement from a company and its employees<br />

(Hitt, Ireland & Hoskisson, 2001:16). This also applies to the automotive industry as it has undergone<br />

considerable turmoil in recent times - not just globally but also in South Africa. Indeed, during the past<br />

decade, the industry has experienced some <strong>of</strong> the greatest changes in history.<br />

For example, during the 20 th Century, the automotive industry was dominated by three original<br />

equipment manufacturers (OEMs), namely, Ford Motor Company, General Motors and Chrysler which<br />

became known as the “the Big 3”. In 1998, Chrysler merged with Daimler Benz to become Daimler-<br />

Chrysler. Traditionally, in the automotive industry, the chain <strong>of</strong> command has been one whereby the<br />

OEMs purchased components and supplies from large Tier 1 suppliers such as, for example Johnson<br />

Controls and Delphi, who in turn procured components and supplies from smaller Tier 2 suppliers,<br />

who in turn procured from yet smaller Tier 3 suppliers. This hierarchical structure resulted in<br />

ineffectual processes, inefficiencies and a strong culture <strong>of</strong> distrust among industry participants<br />

(Applegate & Collins, 2005:1).<br />

During the 1970s, the American OEMs gradually began losing market share to foreign competitors,<br />

particularly to the Japanese competitors, who followed lean and flexible manufacturing principles, as<br />

well as using Keiretsu-style supply chains, and were thus able to build and deliver cars faster, and at a<br />

lower cost than their American counterparts (Applegate & Collins, 2005:1). Far-reaching changes in<br />

the competitive business world, including the presence <strong>of</strong> foreign competitors in domestic markets, are<br />

forcing businesses to rethink their strategies in order to retain current customers and maintain a<br />

competitive advantage (Hodgetts et al 2000:5). This can be achieved by way <strong>of</strong> competing on a global<br />

basis, working harder to protect local market shares, and by suppliers <strong>of</strong>fering higher quality products<br />

at competitive prices.<br />

Literature Review<br />

South Africa has a number <strong>of</strong> OEMs namely, BMW, Ford, Volkswagen, Daimler-Chrysler and<br />

Toyota and they all have production facilities in various locations in the country. Vehicles are<br />

produced for the local and international market. This motor industry has been well supported via a<br />

vibrant automotive component industry which supplies the OEMs, the South African aftermarket and a<br />

spread <strong>of</strong> 249 export markets, mostly in the European Union (EU).<br />

During the apartheid years the South African motor industry was aided by the government and<br />

protected via high import duties. Since the advent <strong>of</strong> democracy in 1994, and the subsequent<br />

liberalisation <strong>of</strong> the economy, the government has had to reduce its import tariffs on an ongoing basis,<br />

in line with World Trade Organisation requirements. At the same time, to assist the industry to be<br />

economically viable in the global arena, the South African government devised the Motor Industry<br />

Development Programme (MIDP). MIDP is a programme that was launched in September 1995 to readjust<br />

the structure <strong>of</strong> the automotive industry so that global competitiveness could be achieved (TISA<br />

2003:8). The aim <strong>of</strong> MIDP was to slowly reintegrate South Africa into the global automotive industry.<br />

Import tariffs were slowly reduced to give the local industry an opportunity to adapt (Williams,<br />

2004:1). This well designed and well managed programme has given the industry much needed time to<br />

improve its efficiencies and to become more cost effective.<br />

II. Brief History <strong>of</strong> MIDP<br />

TISA (2003:8) specified that government support to the Motor industry in South Africa began in the<br />

1920’s. The preliminary phase – classical import substitution which supported simple assembly for the<br />

domestic market - lasted until 1961. During this time, heavy import duties on imported motor cars<br />

promoted the development <strong>of</strong> an industry <strong>of</strong> small assembly plants producing a relatively wide range <strong>of</strong><br />

models in small volumes at high cost. Barnes (2000:2) pointed out that during the 1920’s, as a direct<br />

result <strong>of</strong> tariff protection being afforded to automotive assemblers, some basic components such as<br />

batteries, glass and tyres were being procured locally.

During 1961 and 1995 five new distinct phases <strong>of</strong> government support for the industry were identified.<br />

These phases included ongoing market protection and an array <strong>of</strong> incentives and requirements for<br />

increased local content. Local content requirements were supported by punitive tariffs on imported<br />

components. These phases involved a combination <strong>of</strong> tariffs and import permits, with each phase<br />

intending to increase the amount <strong>of</strong> local content and further promote OEM-component relationships in<br />

South Africa (TISA 2003:8).<br />

MIDP was launched in September 1995, and aimed to develop an internationally competitive and<br />

growing automotive industry. MIDP has five main objectives: (1) improve the global competitiveness<br />

<strong>of</strong> OEMs and automotive component firms; (2) provide superior quality; (3) produce affordable<br />

vehicles and components to the domestic and international markets; (4) enhance growth <strong>of</strong> the<br />

assembly and automotive components firms; and (5) stabilise employment levels, thereby improving<br />

the economic growth <strong>of</strong> the country by increasing production and thus improve the industry’s trade<br />

balance.<br />

The major policy instruments to achieve these objectives have been a gradual and ongoing<br />

reduction in tariff protection in order to expose the industry to greater global competition; and the<br />

support <strong>of</strong> greater volumes and specialisation by allowing exporting automotive component firms to<br />

earn rebates on import duties (TISA 2003:8). For example (Haynes 2004:1) under the MIDP export<br />

scheme, when a firm exports automotive components they qualify for Import Rebate Credit Certificates<br />

(IRCCs). These IRCCs can be used to <strong>of</strong>fset customs duty on automotive imports. Exporters unable to<br />

use the IRCCs can use the option to sell these negotiable instruments to an importer.<br />

Despite various incentives the automotive component industry receives only insignificant<br />

government protections and is currently faced with increased competition. This competition is a<br />

challenge from two points, (a) foreign imports into the domestic market, hence the firm needs to<br />

improve competitiveness; and (b) firms need to reposition themselves in new value chains in order to<br />

combine relationships with OEMs and thus facilitate exports (Barnes 2000:5).<br />

MIDP has now been in operation for ten years and has successfully helped guide the automotive<br />

industry’s integrated emergence from isolation to becoming a global supplier that exports high<br />

technology and quality automotive components to demanding world markets. MIDP has been extended<br />

until 2012 in order to maintain and boost the South African industry’s attractiveness as a foreign<br />

investment destination and production base for exporting completely built-up vehicles and<br />

components; to maintain the impetus <strong>of</strong> exports; and to secure the continued feasibility <strong>of</strong> domestic<br />

vehicle and component manufacture (TISA 2003:9).<br />

III. The Automotive Component Industry<br />

South Africa has an abundance <strong>of</strong> raw materials and produces in excess <strong>of</strong> 60% <strong>of</strong> the world’s<br />

platinum, rhodium and palladium, which are essential catalysts in catalytic converters (TISA 2003:41).<br />

Hence, where a single production facility is concerned, the South African automotive component<br />

industry is able to manufacture a range <strong>of</strong> quality products at competitive prices because <strong>of</strong> access to<br />

these raw materials and therefore lower input costs. South African automotive component<br />

manufacturers have also had a competitive advantage from a flexibility point <strong>of</strong> view, as local<br />

automotive manufacturers are able to produce lower volumes on relatively short notice compared to<br />

other countries where production is set up for long high-production runs (TISA 2003:41).<br />

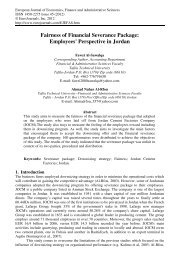

Graph 1 provides a picture <strong>of</strong> how South African component exports have increased since 1994 and<br />

peaked in 2002. In 2003 automotive component exports declined from R22.9 billion to R21.2 billion,<br />

but increased in 2004 to R21.7 billion. This decline can be attributed to the strengthening and<br />

stabilisation <strong>of</strong> the value <strong>of</strong> the Rand versus the US Dollar and the Euro.<br />

Graph 1: SA Component Exports: 1995 to 2004

Rands (Millions)<br />

26,000<br />

24,000<br />

22,000<br />

20,000<br />

18,000<br />

16,000<br />

14,000<br />

12,000<br />

10,000<br />

8,000<br />

6,000<br />

4,000<br />

2,000<br />

0<br />

3,318<br />

4,051<br />

SA component exports: 1995 to 2004<br />

5,115<br />

7,895<br />

9,674<br />

12,640<br />

Source: Trade and Investment South Africa (TISA): Department <strong>of</strong> Trade and Industry (DTI)<br />

Catalytic converters, leather seat covers and aluminium based products make up the bulk <strong>of</strong> automotive<br />

component exports. The main destinations continue to be first-world markets with Germany<br />

comprising 35.9%, in rand terms, <strong>of</strong> the total component exports. The EU was South Africa’s main<br />

export destination in 2003 with 69,9% <strong>of</strong> the automotive component industry compared to 71,3% in<br />

2004 (Lamprecht, 2006:1).<br />

IV. Trends in the Global Automotive Market<br />

During the 1990s most industries globally were changed from closed to open industries resulting in an<br />

increase in global trade and the integration <strong>of</strong> business. Through this integration progression, national<br />

economic borders and trade barriers have almost totally disappeared. People, materials, products and<br />

information now move more freely between countries than before the integration process. As firms<br />

become more global, supply chains will become more global. Global supply chains face different<br />

challenges to those <strong>of</strong> domestic chains (Hugo, Badenhorst-Weiss & Van Biljon, 2004:325). For<br />

example, global markets will not accept poor customer service, inconsistent quality, higher pricing and<br />

stock-out situations to the same degree as local markets.<br />

There is a movement towards the globalisation <strong>of</strong> production, as goods and services are purchased<br />

from different parts <strong>of</strong> the word in order to take advantage <strong>of</strong> national differences in the cost and<br />

quality <strong>of</strong> factors <strong>of</strong> production (Hill, 2001:7). By doing this, businesses hope to reduce their overall<br />

cost structure and improve the quality <strong>of</strong> their products, thus enabling them to sell their products at a<br />

lower price and ultimately sustain a competitive advantage.<br />

The strengths in the South African market could be used as a source for competitive advantage.<br />

South Africa’s automotive component manufacturing industry is internationally renowned for its<br />

technological sophistication, expertise and flexibility. This enables local automotive component<br />

manufacturers to manufacture a wide variety <strong>of</strong> products quickly and economically in small volumes<br />

whilst at the same time meeting high international quality and supply reliability standards (TISA,<br />

2003:41).<br />

18,586<br />

22,883<br />

21,269<br />

21732.6<br />

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004<br />

Year

V. Data and Methodology<br />

Research Problem<br />

South African automotive component manufacturers face unique challenges in a very competitive<br />

market that could be approached from various angles. The research problem <strong>of</strong> this study was to<br />

identify these unique challenges and ascertain whether the implementation <strong>of</strong> a `philosophy <strong>of</strong><br />

continuous improvement` can be used as a strategic tool to address the challenges they face in the<br />

market.<br />

Research Objectives<br />

The objectives <strong>of</strong> this research were to:<br />

1. Identify the challenges facing South African automotive component manufacturers.<br />

2. Determine whether a ‘philosophy <strong>of</strong> continuous improvement’ can be used as a strategic tool to<br />

help the South African automotive manufacturers address the challenges they face.<br />

Sampling<br />

As the automotive component industry consists <strong>of</strong> numerous sub-sectors, many <strong>of</strong> whom contribute<br />

only minute portions to the total exports, initial research and practical considerations suggested that it<br />

would make more sense to concentrate the empirical research on the larger sub-sectors that represent<br />

more than 60% <strong>of</strong> the total value <strong>of</strong> exports. The non-probability quota sample technique was used to<br />

select the sample. The sample consisted <strong>of</strong> selected sub-sectors: catalytic converters, stitched leather<br />

components, tyres and road wheels/parts – which contribute 64,1% <strong>of</strong> the total value <strong>of</strong> automotive<br />

component exports in South Africa.<br />

Questionnaire Design<br />

The questionnaire was based on the literature survey and was divided into three sections, namely<br />

section A, B and C. Section A primarily dealt with the company pr<strong>of</strong>ile. The aim <strong>of</strong> Section B was to<br />

investigate challenges faced in global markets from a supply chain management perspective. These<br />

challenges were identified in the literature review and used as a basis for the questionnaire. Section C<br />

included a series <strong>of</strong> questions designed to determine opinions on various issues which are relevant in<br />

the South African business environment.<br />

Pilot Study<br />

To test the content validity and the reliability <strong>of</strong> the questionnaire, the initial questionnaire was used to<br />

conduct a pilot study at two companies who are the main suppliers <strong>of</strong> automotive filters for passenger<br />

vehicles. The results <strong>of</strong> this questionnaire were used in the main research.<br />

Data Collection<br />

A list <strong>of</strong> all automotive component manufacturers, together with contact details was obtained from The<br />

National Association <strong>of</strong> Automotive Component and Allied Manufacturers, The Department <strong>of</strong> Trade<br />

and Industry and the Chamber <strong>of</strong> Commerce. Because <strong>of</strong> the small number <strong>of</strong> manufacturers within the<br />

selected sub-sectors, it was feasible to contact all respondents via telephone prior to sending out the<br />

questionnaire. This was found to be most useful as in each instance, the questionnaire was sent to a<br />

senior manager who was dealing with exports. The majority <strong>of</strong> completed questionnaires were returned<br />

within one week.<br />

Empirical Findings<br />

Response<br />

The number <strong>of</strong> manufacturers within the four selected sub-sectors and the filter industry amounted to<br />

thirty-one. Of these companies, two declined to partake in this research study owing to time constraints<br />

and two others were no longer exporting. Twenty-seven questionnaires were sent out and a total <strong>of</strong><br />

twenty (74% response rate) were duly completed by the respondents and returned to the researcher.

Findings<br />

South Africa faces unique challenges and these are listed and ranked according to priority from most to<br />

least important. During analysis, the non-standardised and complex nature <strong>of</strong> the data was classified<br />

into categories before they were discussed. Rating or scale questions were used to collect opinion data,<br />

and the Likert-style rating scale approach was used. The objective <strong>of</strong> this study was to provide policy<br />

makers with some insight into real problems with regard to supply chain management in the<br />

automotive component industry, although the stance has in no way been taken that all the problems in<br />

the automotive component industry are supply chain related.<br />

Questionnaires were analysed using both Micros<strong>of</strong>t Excel and Word. Eleven major challenges facing<br />

exporters within this industry were identified. These are as follows:-<br />

1. The reduction <strong>of</strong> production costs<br />

2. R/US$ exchange rate effect on respondent’s export sales and pr<strong>of</strong>it margins<br />

3. Exchange rate fluctuations<br />

4. China – a threat to the local automotive component market<br />

5. Increased competition by way <strong>of</strong> manufactured imports being sold in the South African Market<br />

6. Emergence <strong>of</strong> the Chinese automotive component industry from a global perspective<br />

7. Supplier relationships<br />

8. HIV/Aids pandemic<br />

9. A common approach to environmental management<br />

10. The industry is not improving its competitiveness quickly enough to keep up with continuously<br />

improving international competitors<br />

11. The incorporation <strong>of</strong> ten additional countries in the EU is a threat to the local component<br />

market<br />

Recommendations on how to deal with these challenges are dealt with in the next section<br />

Major challenges categorised together with some proposed recommendations:-<br />

As shown in table 1, all challenges relating to increased competition are grouped together and ranked<br />

according to priority from most to least important, together with some proposed recommendations on<br />

how these challenges may be addressed in order to enhance competitive advantage.<br />

Table 1: Increased Competition<br />

Challenges<br />

1. The reduction <strong>of</strong><br />

production costs.<br />

2. Increased competition by<br />

way <strong>of</strong> manufactured<br />

imports being sold in the<br />

South African market.<br />

Recommendations<br />

1. Become more globally competitive<br />

through lean production or Just-in-time<br />

production programmes.<br />

2. Reduce supplier database and develop<br />

partnership relationships with suppliers.<br />

3. Automate production processes, thereby<br />

reducing costs <strong>of</strong> labour.<br />

1. Focus on the poor quality aspect <strong>of</strong><br />

imported components in that they do not<br />

meet OEM specifications.<br />

2. Initiate distributor loyalty incentives.<br />

3. Reduce costs, thereby leaving selling<br />

prices unchanged.<br />

4. Increase production efficiency.

3. The industry is not<br />

improving its<br />

competitiveness fast<br />

enough to keep up with<br />

continuously improving<br />

international competitors.<br />

1. Competitive benchmarking - eliminating<br />

gaps.<br />

2. Identify the gap between industry<br />

standards and an organisation’s standards.<br />

3. Instill a philosophy <strong>of</strong> continuous<br />

improvement.<br />

Table 2 lists and ranks all challenges relating to shared or reduced risk according to priority from most<br />

to least important, together with some proposed recommendations on how these challenges may be<br />

addressed from a supply chain perspective.<br />

Table 2: Shared or Reduced Risk<br />

Challenges Recommendations<br />

1. R/US$ exchange<br />

rate effect on<br />

respondent’s export<br />

sales and pr<strong>of</strong>it<br />

margins.<br />

2. Exchange<br />

rate<br />

fluctuations.<br />

1. Adjust trade balances by increasing imports<br />

(inputs)<br />

2. Purchase forward cover.<br />

3. Improve negotiation strategies in order to reduce<br />

the cost <strong>of</strong> raw materials.<br />

4. Internal restructuring – eliminate non-value<br />

adding processes.<br />

1. Purchase forward cover when<br />

importing and when exporting, change sell rate to<br />

SA Rands.<br />

2. Where the firm is involved in a longterm<br />

supply relationship, maintain a stable price<br />

in US$ and absorb the shocks caused by<br />

temporary fluctuations.<br />

3. Reduce current pr<strong>of</strong>it margins rather<br />

than permanently lose market share.<br />

4. Export to Sub-Saharan African<br />

countries that have currencies that are weaker than<br />

the Rand to <strong>of</strong>fset losses incurred on overseas<br />

exports (USD based).<br />

Table 3 lists and ranks all challenges relating to global competitors ranked from most to least<br />

important, together with proposed recommendations on how these challenges may be managed from a<br />

supply chain perspective.

Table 3: <strong>International</strong> Competitors: China and EU<br />

Challenges Recommendations<br />

1. China, a threat to<br />

the local automotive<br />

component market.<br />

2. Emergence <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Chinese automotive<br />

component industry<br />

from a global<br />

viewpoint.<br />

3. Absorption<br />

<strong>of</strong> ten new countries<br />

into the EU – a threat<br />

to the local component<br />

market.<br />

1. Benchmark against Chinese automotive<br />

component manufacturers and eliminate any gaps.<br />

1. Provide a superior service.<br />

2. Become more flexible in terms <strong>of</strong> management<br />

and production processes.<br />

3. Offer branding warranties<br />

1. Instill a company culture <strong>of</strong> continuous<br />

improvement.<br />

2. Monitor the competitive environment and<br />

research the market<br />

4. Search for new investment areas in this region,<br />

as competitors have done.<br />

5. Offer better quality and lower prices than<br />

competitors<br />

Table 4 records and ranks all challenges relating to supplier relationships according to priority from<br />

most to least important, together with some proposed recommendations on how these challenges may<br />

be dealt with from a supply chain perspective.<br />

Table 4: Supplier Relationships<br />

1. Supplier relationships. 1. Suppliers to ensure that they<br />

continuously meet contractual<br />

quality requirements and delivery<br />

deadlines<br />

2. Remain cost competitive.<br />

3. Offer exceptional customer<br />

service.<br />

Lastly, table 5 records and ranks all challenges relating to general challenges facing exporters<br />

according to priority from most to least important, together with some proposed recommendations on<br />

how these challenges may be dealt with from a supply chain perspective

Table 5: General Challenges<br />

1. HIV/Aids pandemic. 1. Implement an HIV/Aids policy.<br />

2. Run training programmes for HIV<br />

counsellors.<br />

3. Offer voluntary HIV testing and antiretrovirals<br />

2. Approach to<br />

environmental<br />

management.<br />

3. Shorter product life<br />

cycles<br />

1. Reduce the amount <strong>of</strong> waste.<br />

2. Reuse materials wherever possible.<br />

3. Recycle / remanufacture products.<br />

4. Substitute raw materials with synthetic<br />

materials wherever possible.<br />

5. Adhere to ISO14001 accreditation<br />

requirements.<br />

1. Reduce production time.<br />

2. Continuous research combined with the<br />

utilisation <strong>of</strong> better and improved components.<br />

South African suppliers are facing enormous challenges from competitors in China, Eastern Europe<br />

and South America, with perhaps the emergence <strong>of</strong> the Chinese market providing the largest challenge.<br />

In order to survive, it is vital that exporters within this industry improve production costs and<br />

efficiencies in order to remain competitive in this global environment.<br />

Most respondents were confident that South African automotive component manufacturers achieved<br />

and sustained world-class performance standards.<br />

Lastly, respondents noted that the strengthening and stabilisation <strong>of</strong> the value <strong>of</strong> the Rand versus the<br />

US Dollar and the Euro, and the increase in producer price index costs above the level <strong>of</strong> their<br />

international competitors, are eroding the improvements achieved by the South African manufacturers.<br />

This issue, together with the demise <strong>of</strong> MIDP in 2012 might see the collapse <strong>of</strong> the export industry.<br />

The viability <strong>of</strong> automotive component exports from SA is highly dependent on the MIDP export<br />

benefits and will recede once these support measures are removed, unless manufacturers are able to<br />

further reduce production costs and increase productivity.<br />

Limitations to the study<br />

This research study has focused on four selected sub-sectors <strong>of</strong> the automotive component industry,<br />

including the filter industry which formed part <strong>of</strong> the pilot study. These sub-sectors make up 64.1% <strong>of</strong><br />

the total component exporters in South Africa. The limitation <strong>of</strong> the research was that as the nonprobability<br />

quota sample technique was used not all sub-sectors within the automotive component<br />

industry were included in this study.<br />

Areas for further research<br />

This study would have been more accurate and meaningful if all South African exporters <strong>of</strong> all<br />

component categories in the automotive component industry had been included in this study. Further<br />

research involving all exporters within this industry could be undertaken at a later stage, based on<br />

random sampling while the possibility <strong>of</strong> a comparative study with another country could be explored.

Conclusion<br />

In order to survive, South African automotive component manufacturers/exporters need to remain<br />

globally competitive. The industry is facing enormous challenges, particularly from China and other<br />

foreign imports entering the domestic market. This competition is impacting not only on selling prices<br />

but also on pr<strong>of</strong>it margins, and ultimately will affect South Africa’s employment market via job losses.<br />

The fact that South African automotive component manufacturers succeeded in identifying and<br />

supplying pr<strong>of</strong>itable market niches in a very competitive global market is pro<strong>of</strong> that these companies<br />

possess the required entrepreneurial acumen to survive the anticipated onslaught from the Chinese and<br />

East European markets. In this regard, it is important that component manufacturers benchmark against<br />

all major competitors, and aggressively work at eliminating any gaps. A vital aspect <strong>of</strong> this will be the<br />

reduction <strong>of</strong> production costs and the improvement in efficiencies in order to maintain and improve<br />

their competitiveness. This goal can only be achieved through the striving for a culture <strong>of</strong> continuous<br />

improvement in all aspects <strong>of</strong> their businesses.<br />

Tools that can be used to achieve this end will be the implementation <strong>of</strong> world class manufacturing<br />

programmes and adhering to lean production practices.<br />

VI. References<br />

[1] Applegate, L.M. & Collins, E.L. (2005). “Covisint (A): The Evolution <strong>of</strong> a B2B Marketplace”.<br />

Harvard <strong>Business</strong> School, June 29 2005. (9-805-110).<br />

[2] Barnes, J.R. (2000). “Changing Lanes: The Political Economy <strong>of</strong> the South African Automotive<br />

Value Chain”. Development <strong>of</strong> Southern Africa, 0376835X, September 2000, Vol. 17, Issue 3,<br />

pp1-12.<br />

[3] Haynes, C. (2004). “Overview <strong>of</strong> the South African Motor Industry”. May 2004 [Online]<br />

Available: http://www.autocluster.co.za/ id316_m.htm.<br />

[4] Hill, C.W. (2001). <strong>International</strong> <strong>Business</strong>. “Competing in the Global Marketplace”. 3 rd Edition.<br />

New York: McGraw-Hill.<br />

[5] Hill, C.W.L & Jones, G.R. (2004). Strategic Management. An Integrated Approach. Sixth<br />

Edition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.<br />

[6] Hitt M.A., Ireland, R.D & Hoskisson, R.E. (2001) Strategic Management. Competitiveness and<br />

Globalisation. Concepts and Cases. Fourth Edition. Australia: South Western College<br />

Publishing. Thomson Learning.<br />

[7] Hodgetts, R.M. & Luthans F. (2000). “<strong>International</strong> Management: Culture, Strategy and<br />

Behaviour”. <strong>International</strong> Edition. Boston: McGraw-Hill.<br />

[8] Hugo, W.M.J., Badenhorst-Weiss, J.A. & van Biljoen, E.H.B. (2004). “Supply Chain<br />

Management. Logistics in Perspective”. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers<br />

[9] Lamprecht, N. (2006) “Main Export Destinations for all Components”. South African<br />