Role of Intestinal Microbiota in Ulcerative Colitis

Role of Intestinal Microbiota in Ulcerative Colitis

Role of Intestinal Microbiota in Ulcerative Colitis

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Theoretical part<br />

14<br />

2. The colonic environment<br />

However, to avoid unnecessary detection <strong>of</strong> Gram‐positive commensal bacteria, IECs have<br />

developed special mechanisms to tolerate the cont<strong>in</strong>uous presence <strong>of</strong> LTA molecules orig<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g<br />

from commensals by express<strong>in</strong>g TLR2 and co‐receptors at a limited level (Melmed et al.,<br />

2003;Lebeer et al., 2010). The same mechanism has been observed for TL4 on IECs, <strong>in</strong> which<br />

expression <strong>of</strong> TLR4 is down‐regulated to avoid hyper‐responsiveness to lipopolysaccharide (LPS)<br />

(Table 2) from commensal Gram‐negative bacteria (Abreu et al., 2001).<br />

In literature, immune regulatory effects <strong>of</strong> commensal bacteria through TLRs have been observed.<br />

As an example, Hoarau et al. (2006) demonstrated that the supernatant <strong>of</strong> B. breve could cause<br />

maturation <strong>of</strong> DCs through TLR2 pathway. This effect led to high levels <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terleuk<strong>in</strong> (IL)‐10<br />

(<strong>in</strong>ducer <strong>of</strong> regulatory T cells (Treg cells)) and low levels <strong>of</strong> IL‐12, <strong>in</strong> contrast to DCs stimulated with<br />

LPS. Another Bifidobacterium species, B. longum, has shown to attenuate Tumor Necrosis Factor‐<br />

alfa (TNF‐α)‐<strong>in</strong>duced Nuclear factor kappa B (NF‐κB) activation and NF‐κB‐mediated IL‐8<br />

expression through TLR9 (Ghadimi et al., 2010). F<strong>in</strong>ally, a study by Geuk<strong>in</strong>g et al. (2011)<br />

demonstrated that the colonization <strong>of</strong> mice with a completely benign commensal microbiota<br />

(altered Schaedler Flora) resulted <strong>in</strong> activation <strong>of</strong> colonic Treg cells <strong>in</strong> lam<strong>in</strong>a propria through TLR<br />

signal<strong>in</strong>g, which led to <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al T cell homeostasis as reflected by the absence <strong>of</strong> T helper 1 cell or<br />

T helper 17 cell responses.<br />

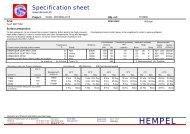

Table 2: TLR recognition <strong>of</strong> Microbial Components<br />

Microbial Components Species TLR Usage References<br />

Triacyl lipopeptides Bacteria and mycobacteria TLR1 (Takeuchi et al., 2002)<br />

Peptidoglycan Gram‐positive bacteria TLR2 (Takeuchi et al.,<br />

1999;Schwandner et al.,<br />

1999)<br />

Fimbrill<strong>in</strong> Porphyromonas g<strong>in</strong>givalis TLR2/TLR4 (Davey et al., 2008)<br />

Polysaccharide A Bacteroides fragilis TLR2 (Round et al., 2011)<br />

Lipoarab<strong>in</strong>omannan Mycobacteria TLR2 (Means et al., 1999)<br />

Por<strong>in</strong>s Neisseria TLR2 (Massari et al., 2002)<br />

Lipoteichoic acid Gram‐positive bacteria TLR2/TLR6 (Schwandner et al., 1999)<br />

Lipopolysaccharide Gram‐negative bacteria TLR4 (Poltorak et al., 1998)<br />

Flagell<strong>in</strong> Flagellated bacteria TLR5 (Hayashi et al., 2001)<br />

Diacyl lipopeptides Mycoplasma TLR6 (Takeuchi et al., 2001)<br />

CpG‐conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g DNA Bacteria and mycobacteria TLR9 (Hemmi et al., 2000)<br />

Not determ<strong>in</strong>ed Not determ<strong>in</strong>ed TLR10 ‐<br />

Not determ<strong>in</strong>ed Uropathogenic bacteria TLR11 (Zhang et al., 2004)