BEM Dec07-Feb08 (Pro.. - Board of Engineers Malaysia

BEM Dec07-Feb08 (Pro.. - Board of Engineers Malaysia

BEM Dec07-Feb08 (Pro.. - Board of Engineers Malaysia

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

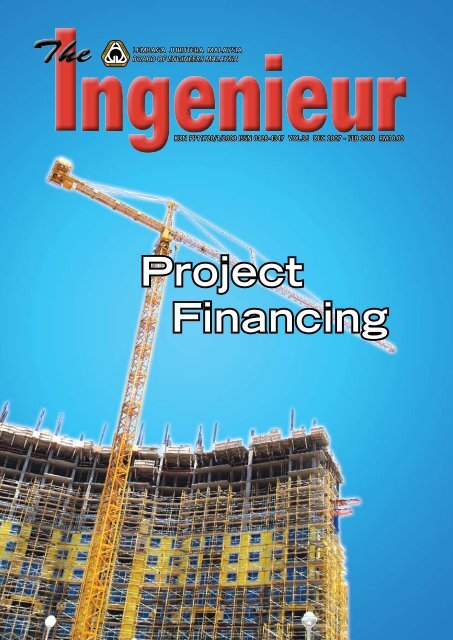

LEMBAGA JURUTERA MALAYSIA<br />

BOARD OF ENGINEERS MALAYSIA<br />

KDN PP11720/1/2008 ISSN 0128-4347 VOL.36 DEC 2007 - FEB 2008 RM10.00<br />

<strong>Pro</strong>ject<br />

Financing

2 THE INGENIEUR<br />

Volume 36 Dec 2007 - Feb 2008<br />

8<br />

42<br />

56<br />

64<br />

c o n t e n t s<br />

4 President’s Message<br />

Editor’s Note<br />

Announcement<br />

5 Publication Calender<br />

Cover Feature<br />

6 Private Finance Initiatives – Infrastructure And<br />

Utilities Development<br />

12 Incorporating Facilities Management In PFI <strong>Pro</strong>posals<br />

22 <strong>Pro</strong>fessional Services Export Fund<br />

Update<br />

24 Situations Under Which Internal Plumbing Plan<br />

Approval Can Be Given Though External Plan Not<br />

Approved Yet<br />

Engineering & Law<br />

25 The SCL Delay And Disruption <strong>Pro</strong>tocol: An Overview<br />

Feature<br />

33 Building And Common <strong>Pro</strong>perty Act 2007<br />

41 <strong>Pro</strong>file - The <strong>Malaysia</strong>n Institute <strong>of</strong> Arbitrators<br />

42 Dispute On Arbitrators, Advertising And Ethics<br />

44 Structural Inspection Of Existing Bridges<br />

48 Strata Titles (Amendment) Act 2007<br />

54 An Overview Of The Use Of Explosives For<br />

The Demolition Of Building Structures<br />

60 Disabled People As Stakeholders In A Barrier-Free<br />

Built Environment<br />

Engineering Nostalgia<br />

64 Kuala Lumpur – Major Flood In January 1971<br />

2008 Registration Renewal Notice<br />

Every registered <strong>Pro</strong>fessional Engineer and Engineering<br />

Consultancy practice shall renew their Registration for year 2008.<br />

Please visit www.bem.org.my to download the Renewal Forms.

4 THE INGENIEUR<br />

KDN PP11720/1/2008<br />

ISSN 0128-4347<br />

Vol. 36 Dec 2007- Feb 2008<br />

MEMBERS OF THE BOARD OF ENGINEERS MALAYSIA<br />

(<strong>BEM</strong>) 2007/2008<br />

President<br />

YBhg. Dato’ Sri <strong>Pro</strong>f. Ir. Dr. Judin Abdul Karim<br />

Registrar<br />

Ir. Dr. Mohd Johari Md. Arif<br />

Secretary<br />

Ir. Ruslan Abdul Aziz<br />

Members<br />

YBhg. Tan Sri <strong>Pro</strong>f. Ir. Dr. Mohd Zulkifli Tan Sri Mohd Ghazali<br />

YBhg. Datuk Ir. Hj. Keizrul Abdullah<br />

YBhg. Lt. Gen. Dato’ Ir. Ismail Samion<br />

YBhg. Dato’ Ir. Ashok Kumar Sharma<br />

YBhg. Datuk (Dr.) Ir. Abdul Rahim Hj. Hashim<br />

YBhg. Datu Ir. Hubert Thian Chong Hui<br />

YBhg. Dato’ Ir. <strong>Pro</strong>f. Chuah Hean Teik<br />

Ar. Dr. Amer Hamzah Mohd Yunus<br />

Ir. Henry E Chelvanayagam<br />

Ir. Dr. Shamsuddin Ab Latif<br />

Ir. <strong>Pro</strong>f. Dr. Ruslan Hassan<br />

Ir. Mohd. Rousdin Hassan<br />

Ir. Tan Yean Chin<br />

Jaafar Bin Shahidan<br />

Ir. Ishak Abdul Rahman<br />

Ir. Anjin Hj. Ajik<br />

Ir. P E Chong<br />

EDITORIAL BOARD<br />

Advisor<br />

YBhg. Dato’ Sri <strong>Pro</strong>f. Ir. Dr. Judin Abdul Karim<br />

Chairman<br />

Ir. Tan Yean Chin<br />

Editor<br />

Ir. Fong Tian Yong<br />

Members<br />

Ir. Prem Kumar<br />

Ir. Mustaza Salim<br />

Ir. Chan Boon Teik<br />

Ir. Ishak Abdul Rahman<br />

Ir. <strong>Pro</strong>f. Dr. K. S. Kannan<br />

Ir. <strong>Pro</strong>f. Madya Dr. Eric K H Goh<br />

Ir. Rocky Wong Hon Thang<br />

Executive Director<br />

Ir. Ashari Mohd Yakub<br />

Publication Officer<br />

Pn. Nik Kamaliah Nik Abdul Rahman<br />

Assistant Publication Officer<br />

Pn. Che Asiah Mohamad Ali<br />

Design and <strong>Pro</strong>duction<br />

Inforeach Communications Sdn Bhd<br />

Printer<br />

Art Printing Works Sdn Bhd<br />

29 Jalan Riong, 59100 Kuala Lumpur<br />

The Ingenieur is published by the <strong>Board</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Engineers</strong> <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

(Lembaga Jurutera <strong>Malaysia</strong>) and is distributed free <strong>of</strong> charge to<br />

registered <strong>Pro</strong>fessional <strong>Engineers</strong>.<br />

The statements and opinions expressed in this<br />

publication are those <strong>of</strong> the writers.<br />

<strong>BEM</strong> invites all registered engineers to contribute articles or<br />

send their views and comments to<br />

the following address:<br />

Publication Committee<br />

Lembaga Jurutera <strong>Malaysia</strong>,<br />

Tingkat 17, Ibu Pejabat JKR,<br />

Jalan Sultan Salahuddin,<br />

50580 Kuala Lumpur.<br />

Tel: 03-2698 0590 Fax: 03-2692 5017<br />

E-mail: bem1@streamyx.com; publication@bem.org.my<br />

Website: http://www.bem.org.my<br />

Advertising/Subscriptions<br />

Subscription Form is on page 58<br />

Advertisement Form is on page 59<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong> enjoys an early start on Private<br />

Finance Initiatives (PFIs) since the introduction<br />

<strong>of</strong> privatisation projects back in 1983. Most <strong>of</strong><br />

the early PFIs were in economic infrastructure<br />

projects such as highways, independent power<br />

supply and water supply, together with a<br />

few social infrastructure projects. With the<br />

global trend <strong>of</strong> using PFIs, <strong>Malaysia</strong>ns should<br />

capitalise on their expertise to venture beyond our shores for<br />

mega projects in the international market.<br />

It is estimated that East Asia alone requires some US$200<br />

billion annually over the next five years for infrastructure projects,<br />

and many <strong>of</strong> them require some form <strong>of</strong> financing. The scope<br />

for engineers in these areas can be wide and bright. Since PFI<br />

ties the concessionaire to the life cycle cost <strong>of</strong> the projects,<br />

unlike conventional contracts, the facility managers who are<br />

mainly M&E engineers will assume an important role to meet<br />

the KPIs and the bankability <strong>of</strong> PFI projects.<br />

With more mega projects in the pipeline that may involve<br />

PFIs, engineers as part <strong>of</strong> the concessionaire support team should<br />

have sound knowledge <strong>of</strong> the mechanisms <strong>of</strong> PFI. As <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

positions herself in the international scene for trade, industry<br />

and tourism, the challenges facing the nation in coping with<br />

expanding infrastructures and facilities <strong>of</strong> world class standard<br />

will be opportunities for our engineers. However, these are only<br />

for those who excel technically and managerially.<br />

Dato’ Sri <strong>Pro</strong>f Ir Dr Judin bin Abdul Karim<br />

President<br />

BOARD OF ENGINEERS MALAYSIA<br />

<strong>BEM</strong>’s Publication Committee welcomes on board<br />

the new Committee chairman, Ir Tan Yean Chin and<br />

his new team members.<br />

The year 2007 witnessed some exciting events<br />

that have impacted practising engineers such as<br />

the introduction <strong>of</strong> CCC, OSC, the announcement<br />

<strong>of</strong> economic corridors, revival <strong>of</strong> double tracking projects and<br />

so on. Along with these new delivery systems and projects<br />

announcement, projects financing has taken another cornerstone<br />

with the introduction <strong>of</strong> Private Finance Initiatives (PFI).<br />

This issue with the theme PFI attempts to provide a clearer<br />

insight into the mechanism <strong>of</strong> project financing as engineers can<br />

no longer limit themselves to technical matters in this globalised<br />

market.<br />

In view <strong>of</strong> the impending Act on Disabled Persons that<br />

was recently tabled in the Parliament, an article on Barrier-Free<br />

Environment was introduced as a reminder to pr<strong>of</strong>essionals on<br />

design considerations for the disabled.<br />

To all readers, I wish you a Happy New Year.<br />

Ir Fong Tian Yong<br />

Editor<br />

President’s Message<br />

Editor’s Note

THE INGENIEUR ANNOUNCEMENT<br />

The following list is the Publication<br />

Calendar for the year 2007<br />

- 2008. While we normally seek<br />

contributions from experts for<br />

each special theme, we are also<br />

pleased to accept articles relevant<br />

to themes listed.<br />

Please contact the Editor or the<br />

Publication Officer in advance<br />

if you would like to make such<br />

contributions or to discuss details<br />

and deadlines.<br />

March 2008: POWER<br />

June 2008: ASSET MANAGEMENT<br />

September 2008: ENGINEERING<br />

PRACTISE<br />

December 2008: ENvIRoNMENT<br />

The <strong>Board</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Engineers</strong><br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

wishes all readers<br />

Happy<br />

New Year<br />

2008<br />

&<br />

Gong Xi<br />

Fa Cai<br />

5

6 COVER FEATURE<br />

THE INGENIEUR<br />

Private Finance Initiatives –<br />

Infrastructure And<br />

Utilities Development<br />

By Lee Yuien Siang, Associate Director, Corporate Finance Practice,<br />

PricewaterhouseCoopers <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

Pipe laying<br />

Ajoint Asian Development<br />

Bank, Japan Bank for<br />

International Co-operation<br />

and World Bank estimate is that<br />

East Asia alone has infrastructure<br />

needs totalling US$200 billion<br />

a year over the next five years.<br />

A r o u n d t w o - t h i r d s o f t h i s<br />

expenditure needs to be new<br />

investment, with the balance on<br />

upkeep <strong>of</strong> existing assets.<br />

Internationally, including<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong>, various forms <strong>of</strong><br />

public private partnerships have<br />

been applied to attract private<br />

sector capital and expertise in<br />

developing infrastructure assets<br />

and services. Many construction<br />

companies in selected markets<br />

where infrastructure forms a<br />

sizeable part <strong>of</strong> public sector<br />

procurement have specialised<br />

in developing then selling<br />

investment stakes and retaining<br />

long-term maintenance contracts.<br />

Industry players at all levels can<br />

be involved, from the biggest<br />

Bridge under construction<br />

companies heading consortia to<br />

small, local sub-contractors.<br />

In <strong>Malaysia</strong>, following the<br />

Government’s announcement<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Private Finance Initiative<br />

(‘PFI’) in the Ninth <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

Plan, a lot <strong>of</strong> discussions have<br />

centred around the investment<br />

and financing aspects <strong>of</strong> PFI. For<br />

the engineering fraternity, what<br />

will PFI mean to them?<br />

The PFI Concept<br />

Similar to many existing<br />

privatisation projects, PFI involves<br />

the public sector contracting with<br />

the private sector to undertake<br />

the designing, building, financing<br />

and maintenance <strong>of</strong> certain<br />

infrastructure over the concession<br />

period which typically lasts<br />

between 25 and 30 years. The<br />

key differentiating feature <strong>of</strong> PFI is<br />

the public sector typically retains<br />

responsibility over public services<br />

delivery – customer interface<br />

function with the public. The<br />

public sector also makes service<br />

payments for the infrastructure<br />

a n d p r e d e f i n e d a s s o c i a t e d<br />

services to the private sector<br />

over the life <strong>of</strong> the concession.<br />

PricewaterhouseCoopers’s report<br />

on ‘Delivering the PPP <strong>Pro</strong>mise’<br />

describes the other feature <strong>of</strong> PFI<br />

being that “the private sector<br />

returns are linked to service<br />

outcomes and performance<br />

<strong>of</strong> the asset over the contract<br />

life. The private sector service<br />

provider is responsible not<br />

just for asset delivery, but for<br />

overall project management and<br />

implementation, and successful<br />

operation for several years<br />

thereafter.”<br />

M a ny c o u n t r i e s i n i t i a l l y<br />

develop PFI in the transport<br />

sector and later extend their<br />

use to other sectors, such as<br />

education, health, energy, water<br />

and waste treatment, once the<br />

value for money benefits are

THE INGENIEUR COVER FEATURE<br />

proven and public sector expertise<br />

is established. Sectors where PFI<br />

may be applicable include:<br />

• Central Accommodation<br />

• Airports<br />

• Defence<br />

• Housing<br />

• Health & Hospitals<br />

• IT<br />

• Ports<br />

• Prisons<br />

• Heavy Railway<br />

• Light Railway<br />

• Roads<br />

• Schools<br />

• Sports & Leisure<br />

• Water, Wastewater & Solid<br />

Waste<br />

So far, known PFI projects<br />

in <strong>Malaysia</strong> have been limited<br />

to those undertaken by PFI<br />

Sdn Bhd, a Ministry <strong>of</strong> Finance<br />

company. The arrangement is<br />

different from the international<br />

PFI framework with limited real<br />

risk transfer to the private sector<br />

since both counter parties to the<br />

contract are Government entities.<br />

Here, the private sector only acts<br />

as construction and maintenance<br />

contractors.<br />

Under PFI, the public sector<br />

transfers the design, construction<br />

and operating risks to the<br />

private sector. In contrast<br />

with traditional Government<br />

procurement, the public sector<br />

does not bear the cost <strong>of</strong> cost<br />

overruns. The public sector<br />

also entrusts the concession<br />

company with the operation and<br />

maintenance <strong>of</strong> the infrastructure<br />

such as schools and hospitals.<br />

The public sector can then<br />

focus on delivering their core<br />

services <strong>of</strong> education and<br />

healthcare. PFI is also not a<br />

deferred payment arrangement<br />

which in the conventional sense<br />

means staggered payments for<br />

assets. Under PFI, payments<br />

are made only when facilities<br />

are available and services are<br />

delivered satisfactorily.<br />

Delivering Better Value<br />

for Money<br />

Value for money is increasingly<br />

at the centre <strong>of</strong> the PFI proposition,<br />

a shift from the earlier days when<br />

it was used mainly to source<br />

private sector financing and to<br />

reduce public sector spending.<br />

Better value for money is driven<br />

mainly by the design <strong>of</strong> the<br />

concession and the payment<br />

mechanisms.<br />

To undertake the concession,<br />

the concession company – a<br />

special purpose vehicle, is<br />

established to create a single point<br />

<strong>of</strong> accountability from the private<br />

sector. This effectively erases<br />

any dispute which commonly<br />

arises in a project - whether it<br />

is the designer, the construction<br />

contractor or the maintenance<br />

contractor who will be responsible<br />

for the defect. The single entity will<br />

be solely accountable, allowing<br />

the Government to quickly seek<br />

rectification and remedy without<br />

having to first determine the<br />

cause <strong>of</strong> the defect.<br />

The concession company<br />

will receive performance-linked<br />

payments for services rendered.<br />

Payments may be withheld or<br />

deducted if the assets were not<br />

available or service performances<br />

7

8 COVER FEATURE<br />

THE INGENIEUR<br />

Dam infrastructure<br />

are not up to pre-agreed service<br />

levels. The purpose <strong>of</strong> this<br />

mechanism is to incentivised<br />

the private sector to take full<br />

responsibility over the assets<br />

and services from the design,<br />

construction, maintenance through<br />

to the provision <strong>of</strong> services.<br />

Under PFI, the public sector<br />

will define the specifications<br />

<strong>of</strong> the infrastructure based on<br />

outcome (output specifications)<br />

rather than input specifications.<br />

Designers will therefore have to<br />

ensure that the facilities are fit<br />

for purpose in terms <strong>of</strong> space<br />

planning, configuration, aesthetic,<br />

ambiance, comfort, etc. This<br />

allows flexibility and room for the<br />

private sector to provide innovative<br />

solutions.<br />

As the concession company<br />

is solely responsible for the<br />

assets and services over the<br />

concession period – typically 25<br />

to 30 years, it will incorporate<br />

a design and construction that<br />

will be cost effective to operate<br />

and maintain (and refurbish or<br />

upgrade as necessary). In other<br />

words, this concept <strong>of</strong> whole-life<br />

costing optimisation will have to<br />

take into account the needs <strong>of</strong><br />

operators including the cost and<br />

ease <strong>of</strong> maintenance during the<br />

design and construction phase.<br />

For conventionally procurement<br />

facilities, the design <strong>of</strong> the facilities<br />

may not have provided for cost<br />

effective facility management.<br />

This is a critical concern since the<br />

lifetime operating and maintenance<br />

costs can be three to four times<br />

the capital costs <strong>of</strong> the assets.<br />

The Argument for PFI<br />

Is there a burning platform<br />

for PFI in <strong>Malaysia</strong>? Various<br />

economic and social sectors<br />

compete for funds to create,<br />

expand and enhance infrastructure<br />

and services vital to the public’s<br />

wellbeing and the country’s<br />

competitiveness, particularly in

THE INGENIEUR COVER FEATURE<br />

education, healthcare and the<br />

environment. PFI provides an<br />

option to expedite development<br />

projects and set a framework for<br />

quality asset lifecycle management<br />

as we do have a distance to<br />

go to attain developed nation<br />

status<br />

PFI provides for an effective<br />

transfer <strong>of</strong> design, construction<br />

and operational risks which<br />

could help avoid defects and<br />

accountability issues similar to<br />

those highlighted concerning the<br />

MRR2 flyover, the Kuala Lumpur<br />

Court Complex and certain<br />

Federal Government buildings in<br />

Putrajaya.<br />

Challenges for Designers<br />

and Builders<br />

While the roles <strong>of</strong> designers<br />

and builders are not different<br />

compared to the traditional<br />

design and build contract,<br />

those involved in PFI projects<br />

faces more challenges as the<br />

concession company’s pr<strong>of</strong>its<br />

are “at risk” throughout the<br />

concession period.<br />

The winning bid will have<br />

to be both innovative and cost<br />

effective. Designers and builders<br />

should adopt proven technology<br />

and construction methods and<br />

ensure that construction is well<br />

executed as the costs <strong>of</strong> delays<br />

and cost overruns will be borne<br />

by them. Materials used should<br />

be durable and easy to maintain.<br />

Energy and utilities management<br />

is fundamental to control the<br />

running costs while ensuring<br />

the assets can function properly.<br />

Space and configuration planning<br />

needs to be well thought through<br />

to ensure operations can be<br />

efficiently carried out in addition<br />

to contributing to the comfort and<br />

safety <strong>of</strong> occupants. Asset and<br />

lifecycle management is critical<br />

to ensure that physical assets<br />

are continuously monitored,<br />

maintained and replaced to<br />

m a x i m i s e t h e i r u t i l i s a t i o n<br />

and minimise disruption to<br />

operations.<br />

While PFI projects can be<br />

a very important source <strong>of</strong><br />

construction and investment<br />

income for many constructors,<br />

they can also be risky. Managing<br />

the risks requires pooling <strong>of</strong><br />

resources and expertise which<br />

commonly requires consortia<br />

a r r a n g e m e n t s m a d e u p o f<br />

c o m p a n i e s s p e c i a l i s i n g i n<br />

construction and construction<br />

management, hard and s<strong>of</strong>t<br />

facilities management and strong<br />

financial investors. Such an<br />

approach could be very relevant<br />

in developing the <strong>Malaysia</strong>n<br />

market.<br />

PFI is not and should not<br />

be the solution to all the issues<br />

we face in procuring public<br />

facilities. It is only as good as<br />

the value for money assessment,<br />

the capabilities <strong>of</strong> the concession<br />

company, and the structuring,<br />

management and enforcement <strong>of</strong><br />

the PFI contract. <strong>BEM</strong><br />

9

12 COVER FEATURE<br />

THE INGENIEUR<br />

Incorporating Facilities<br />

Management In PFI <strong>Pro</strong>posals<br />

Ir. Dr. Zuhairi Abd. Hamid, Construction Research Institute <strong>of</strong> <strong>Malaysia</strong> (CREAM),<br />

Construction Industry Development <strong>Board</strong> <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

Facilities Management (FM) is an important component in any Private Finance Initiatives<br />

(PFI). FM in <strong>Malaysia</strong> is relatively new and gradually gaining recognition. This paper<br />

highlights the roles <strong>of</strong> FM in PFI context, whole life cycle costing and its relevancy in<br />

the entire construction value chain. Incorporating FM in PFI proposals in the <strong>Malaysia</strong>n<br />

environment should consider models and lessons learned from other country such as<br />

the UK and American perspectives and modified to suit local needs. It is also the<br />

intention <strong>of</strong> this paper to assist client, developer, contractor and financier to better<br />

understand the concept <strong>of</strong> PFI as well as FM when planning both strategies.<br />

A<br />

s t a t e m e n t b y t h e<br />

Deputy Prime Minister<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Malaysia</strong> (now Prime<br />

Minister) who said : “Unless<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong>ns change their mentality<br />

to become more aware <strong>of</strong> the<br />

need to provide good services<br />

and improve the upkeep <strong>of</strong><br />

buildings, we will forever be a<br />

Third World country with First<br />

World infrastructure” (Badawi,<br />

2001) has stressed the importance<br />

<strong>of</strong> FM in the <strong>Malaysia</strong> context.<br />

Many researchers emphasis<br />

FM as a support function (UCL,<br />

1993; Alexander 1996) to the<br />

organisation, but its role in the<br />

maintenance <strong>of</strong> building facilities<br />

and in property management<br />

are also critical and demanding<br />

(Sarshar, 2000; Underwood and<br />

Alshawi, 2000; Barrett, 1995).<br />

FM represents a field <strong>of</strong> activity<br />

beyond the design, procurement<br />

and furnishing <strong>of</strong> buildings,<br />

that continues into the realm<br />

<strong>of</strong> management skills associated<br />

with the use <strong>of</strong> a facility,<br />

and how that facility evolves<br />

and develops in response to<br />

the changing demands <strong>of</strong> the<br />

occupier (Park, 1998). Others<br />

(Nutt, 2002; Tay and Ooi, 2001)<br />

have taken the definition further<br />

by expanding the scope <strong>of</strong> FM<br />

to cover the entire property<br />

life-cycle <strong>of</strong> designing, building,<br />

financing and operating (Connors,<br />

2003).<br />

Concept behind PFI<br />

PFI projects differ from<br />

traditionally procured public<br />

Feature PFI Conventional<br />

<strong>Pro</strong>curement<br />

Design Public sector client specifies<br />

output required and private<br />

sector consortium provides<br />

design to satisfy requirement<br />

Finance Capital provided by private<br />

sector consortium in return<br />

for a unitary payment from<br />

the public sector client<br />

Construction Construction undertaken by<br />

private sector consortium<br />

Operation and<br />

maintenance<br />

Infrastructure operated and<br />

maintained by private sector<br />

consortium<br />

Services Services provided by public<br />

sector client and/or private<br />

sector consortium<br />

Ownership Ownership reverts to public<br />

sector client or is retained by<br />

private sector consortium<br />

sector projects in a number <strong>of</strong><br />

ways (See Table 1). In a PFI<br />

project the public sector client<br />

specifies the outcomes required<br />

Table 1 Comparison <strong>of</strong> PFI with conventional public sector procurement<br />

Public sector client<br />

specifies design in<br />

conjunction with<br />

external pr<strong>of</strong>essional<br />

advisors<br />

Capital provided by<br />

Exchequer<br />

Construction put out<br />

to competitive tender<br />

to private sector<br />

contractor<br />

Operation and<br />

maintenance by public<br />

sector client or put<br />

out to competitive<br />

tender to private sector<br />

contractor<br />

Services provided by<br />

public sector client or<br />

put out to competitive<br />

tender to private sector<br />

contractor<br />

Infra structure owned<br />

by public sector client<br />

(Dixon et. al,. 2003)

THE INGENIEUR COVER FEATURE 13<br />

Financiers<br />

and a private sector consortium<br />

designs, constructs, finances<br />

and operates the infrastructure<br />

necessary to deliver the outcomes.<br />

It may also deliver services direct<br />

to the public as part <strong>of</strong> the<br />

project (Allen, 2001).<br />

The public sector does not<br />

own the infrastructure but pays<br />

the private sector consortium<br />

a stream <strong>of</strong> unitary payments<br />

to use the infrastructure and<br />

services over the contract period,<br />

normally in the region <strong>of</strong> 25-30<br />

years. At the end <strong>of</strong> this period<br />

ownership <strong>of</strong> the infrastructure<br />

either remains with the private<br />

sector consortium or reverts<br />

to the public sector client,<br />

depending on the terms <strong>of</strong> the<br />

contract (Allen, 2001)<br />

PFI projects typically comprise<br />

three main parties (See Figure<br />

1). The public sector client,<br />

referred to as the awarding<br />

authority, is usually a Government<br />

department, local authority or<br />

other Government agency. The<br />

project company is a special<br />

purpose vehicle (SPV) set up<br />

Awarding Authority<br />

<strong>Pro</strong>ject company<br />

Construction company Consortium<br />

FM provider<br />

Sub-contractor(s)<br />

Investors<br />

Figure 1 Typical PFI project structure (Dixon et. al,. 2003)<br />

by a consortium <strong>of</strong> companies<br />

prepared to assume responsibility<br />

for providing infrastructure and<br />

services to the awarding authority.<br />

Consortia typically consist <strong>of</strong><br />

construction companies, facility<br />

management (FM) providers and<br />

investors. The primary objective<br />

<strong>of</strong> the project company is to<br />

make pr<strong>of</strong>it by minimizing costs<br />

and managing risk throughout<br />

the duration <strong>of</strong> the contract. The<br />

project company may subcontract<br />

responsibility for aspects <strong>of</strong> the<br />

project to third parties (Dixon<br />

et. al, 2003). There are three<br />

main sources <strong>of</strong> finance for PFI<br />

projects:<br />

● Equity funding from institutional<br />

investors,<br />

● Bank loans; and<br />

● Bond issues (Fox and Tott,<br />

1999)<br />

The overriding objective <strong>of</strong> the<br />

financiers is to maximize returns<br />

from their investment by limiting<br />

the project company’s exposure to<br />

risk throughout the project.<br />

Sub-contractor(s)<br />

Private Finance Initiative<br />

(PFI) and Private-Public<br />

Partnerships (PPPs)<br />

In 1992, the UK Conservative<br />

Government introduced the PFI as<br />

a means <strong>of</strong> attracting private sector<br />

investment into public assets<br />

and services (The International<br />

Finance Association, 2002). The<br />

advantages <strong>of</strong> PFI/PPPs have been<br />

the introduction <strong>of</strong> private sector<br />

capital and disciplines into the<br />

provision <strong>of</strong> Government services<br />

which have made it possible<br />

for a larger number <strong>of</strong> projects<br />

to be built, than would have<br />

otherwise been possible without<br />

private sector involvement (The<br />

International Finance Association,<br />

2002). There are no countries<br />

in the world that can undertake<br />

infrastructure projects <strong>of</strong> large<br />

size with their current budgets,<br />

so PFI and PPP are the only real<br />

ways forward (Lenard, 2004).<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the assumed benefits<br />

<strong>of</strong> PFI is that it results in lower<br />

design, construction and operating<br />

costs than conventional public

14 COVER FEATURE<br />

THE INGENIEUR<br />

sector procurement (Stewart and<br />

Butler, 1996). Research suggests<br />

that projects under PFI tend to be<br />

delivered on time and to budget<br />

(Dixon et. al, 2003). A survey<br />

<strong>of</strong> 67 PFI projects by (Ive et al.<br />

2000) found average total cost<br />

savings (comprising design, other<br />

fees, construction, FM and other<br />

operating costs) <strong>of</strong> between 5%<br />

and 10% over conventional public<br />

sector procurement (estimated cost<br />

savings in relation to public sector<br />

comparators or benchmarks used in<br />

the procurement <strong>of</strong> the project).<br />

The public sector is now placing<br />

an increasing reliance on PFI to<br />

deliver better public services (Harris,<br />

2003). The business relationship<br />

between clients and contractors<br />

is changing with the contractor’s<br />

role extending from delivering<br />

facilities to delivering complete<br />

business to clients (Hassan et. al.,<br />

2002). Examining the UK practice<br />

in respect <strong>of</strong> the PFI, it can be seen<br />

that there has been an extension<br />

<strong>of</strong> design and build to include<br />

the maintenance and operation<br />

<strong>of</strong> services, and later transfer <strong>of</strong><br />

the project back to the client<br />

after 25 to 35 years depending<br />

on the concessionaire’s agreement<br />

(Lafford et.al, 2000).<br />

Key Players:<br />

• Owner/Developer<br />

• Architect<br />

• Engineer<br />

• Quantity Surveyor<br />

• <strong>Pro</strong>ject Manager<br />

• Regulatory Body<br />

• Contractor<br />

Research shows that FM is<br />

rarely involved as an integral part<br />

<strong>of</strong> the design process, with the<br />

possible exception <strong>of</strong> PFI (Brown,<br />

2002). The UK Government’s<br />

introduction <strong>of</strong> PFI has brought<br />

together all the key players<br />

in construction, including FM,<br />

under one management team,<br />

which means that fragmentation<br />

issues and lack <strong>of</strong> communication<br />

b e t w e e n t h e c o n s t r u c t i o n<br />

stakeholders should be improved.<br />

In PFI, all the key players are<br />

managed by one consortium with<br />

the directive coming straight from<br />

the owner.<br />

The FM input is therefore seen<br />

as ‘adding value’ to the overall<br />

PFI design <strong>of</strong> both the built and<br />

service products. This situation<br />

has allowed for a much-needed<br />

change in comparison with the<br />

traditional construction approach.<br />

By introducing engineering best<br />

value and longevity into the final<br />

design solution, the PFI consortia<br />

which comprises designer, builder<br />

and operator will ensure that<br />

operational performance is<br />

delivered (Baldwin, 2003).<br />

C o n f l i c t s b e t w e e n k e y<br />

construction players could be<br />

resolved more efficiently internally.<br />

• Owner/Developer<br />

• Architect<br />

• Engineer<br />

• Quantity Surveyor<br />

• <strong>Pro</strong>ject Manager<br />

• Main Contractor<br />

• Architect<br />

• Engineer<br />

• Quantity Surveyor<br />

• <strong>Pro</strong>ject Manager<br />

• Main Contractor<br />

• Sub-contractor<br />

• Construction site<br />

staff<br />

• Construction worker<br />

• Government<br />

Agencies and<br />

Regulatory Bodies<br />

This is not the case in traditional<br />

procurement where many parties<br />

and key players are involved,<br />

as shown in Figure 2. In this<br />

situation, when any disputes and<br />

conflicts arise, the solution has<br />

to be considered as an individual<br />

case at different stages <strong>of</strong> the<br />

construction process where it<br />

actually occurs, and this practice<br />

results in project delays and late<br />

occupancy by the owner.<br />

Lesson Learned from PFI<br />

Practice in the UK<br />

It is crucial to learn from<br />

UK’s or any other country’s<br />

experienced before <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

embarks to implement PFI. The<br />

author has highlighted some <strong>of</strong><br />

the points gathered by Dixon et.<br />

al (2003) to be considered and<br />

studied.<br />

● <strong>Pro</strong>curement and transaction<br />

costs<br />

High performance costs are<br />

a feature <strong>of</strong> PFI, but should fall<br />

as market mature and greater<br />

standardization is achieved in<br />

processes and documentation.<br />

However, the perception <strong>of</strong> high<br />

initial costs also results from<br />

• Owner/Developer<br />

• Architect<br />

• Engineer<br />

• Quantity Surveyor<br />

• <strong>Pro</strong>ject Manager<br />

• Main Contractor<br />

• Management<br />

corporation<br />

• Government<br />

Agencies and<br />

Regulatory Bodies<br />

• Consumer<br />

Design Tender Construction Facilities<br />

Management<br />

Figure 2 Key Players in the Construction Value Chain

THE INGENIEUR COVER FEATURE 15<br />

failures to evaluate costs against<br />

benefits for the whole life <strong>of</strong><br />

these very long contracts, <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

between 20 and 30 years, and<br />

from failure to compare costs with<br />

traditional procurement or leasing<br />

(Dixon et. al, 2003).<br />

● Risk transfer evaluation<br />

In PFI difficulties valuing risk<br />

transfer have resulted in delayed<br />

take-up and criticisms that the<br />

true costs <strong>of</strong> PFI is disguised by<br />

over-generous assumptions about<br />

risk transfer together with discount<br />

rates that are too high. Improved<br />

techniques are therefore needed<br />

for valuing risk transfer over the<br />

whole life <strong>of</strong> PFI contracts. Whole<br />

life costing techniques are not<br />

well developed and it remains to<br />

be seen if PFI can provide the<br />

spur to improvement (Dixon et.<br />

al, 2003).<br />

● Innovation<br />

PFI is an innovative approach<br />

to outsourcing, but, despite<br />

delivering benefits, it is being<br />

criticized as lack <strong>of</strong> innovation<br />

in specific key areas. PFI has<br />

failed to meet public sector<br />

expectations for innovation in<br />

building design and sustainability.<br />

It is worth to examine the<br />

potential for innovation to meet<br />

these expectations (Dixon et. al,<br />

2003).<br />

● Size <strong>of</strong> contracts<br />

In PFI the large scale and<br />

complexity <strong>of</strong> contracts act<br />

as barriers to market entry by<br />

private sector providers and<br />

reduce market competitiveness.<br />

The market should therefore<br />

benefit from measures to adapt<br />

PFI structure to smaller contracts<br />

suited to SMEs and possibly local<br />

authorities (Dixon et. al, 2003).<br />

● Skills<br />

Difficulties with retaining and<br />

recycling project management<br />

skills in the public sector are<br />

posing a threat to the future<br />

success <strong>of</strong> PFI. Developing and<br />

retaining skills are important to<br />

enable organisations to act as<br />

informed clients for PFI (Dixon<br />

et. al, 2003).<br />

The <strong>Pro</strong>ject Life-cycle<br />

Approach<br />

The project life-cycle approach<br />

has shown FM activities to be<br />

critical. It is common to hear<br />

that building information has<br />

not been passed efficiently from<br />

consultant and contractor back<br />

to the client during the handing<br />

over <strong>of</strong> a construction project.<br />

The organisation is seen to have<br />

two separate sets <strong>of</strong> information<br />

- one before and the other after<br />

the completion <strong>of</strong> construction.<br />

O n e t e a m i s r e s p o n s i b l e<br />

during planning, design and<br />

construction and another team<br />

will be introduced to take over<br />

the operation <strong>of</strong> the building<br />

once construction is completed.<br />

Unfortunately, the document to<br />

be submitted with the as-built<br />

drawing during the handing<br />

over <strong>of</strong> a completed project is<br />

not always defined clearly in<br />

the bill <strong>of</strong> quantities, and it is<br />

frequently reported by the client<br />

that information received about<br />

building components needs to<br />

be redone and updated. This has<br />

resulted in user requirements not<br />

being met and has caused delays<br />

Actual whole life cost percentage<br />

40%<br />

35%<br />

30%<br />

25%<br />

20%<br />

15%<br />

10%<br />

5%<br />

0%<br />

run/maintain 38%<br />

repair 20%<br />

period replacement 10%<br />

and rework to reproduce the<br />

information which was available<br />

earlier and could have been<br />

done in advance if the clear<br />

requirement to do so had been<br />

in the contract specification and<br />

the bill <strong>of</strong> quantities.<br />

Major functions in FM like<br />

maintenance and operation have<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten been ignored in the project<br />

life-cycle costing resulting in<br />

buildings that are too expensive<br />

to maintain. Horvath (1999),<br />

Sarshar (2000), and Underwood<br />

and Alshawi (2000) have proposed<br />

that a project infrastructure<br />

should be properly viewed from<br />

a life-cycle perspective. In this<br />

respect, lack <strong>of</strong> information<br />

and co-operation among the<br />

parties, especially between the<br />

contractor and the designer at<br />

the design stage, are the major<br />

contributors to the problem<br />

<strong>of</strong> maintenance (Underwood<br />

and Alshawi, 2000). This has<br />

resulted in cost over-run and<br />

poor organisational performance<br />

(Teicholz, 2004). In many cases,<br />

operation, maintenance and<br />

end-<strong>of</strong>-life environmental costs<br />

<strong>of</strong> facilities have contributed<br />

to 85% <strong>of</strong> costs occurring after<br />

construction, by outweighing all<br />

initial costs (Scarponcini, 1996).<br />

A study by Teicholz (2004) also<br />

suggested that the design and<br />

risk reserve 8%<br />

disposal 2%<br />

design 4%<br />

Benchmarking cost <strong>of</strong> total ownership<br />

Figure 3 Benchmarking Cost <strong>of</strong> Total Ownership<br />

(Boussabaine et al., 2004)<br />

construction 18%

16 COVER FEATURE<br />

THE INGENIEUR<br />

construction <strong>of</strong> buildings <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

represents less than 15% <strong>of</strong><br />

the total life-cycle cost <strong>of</strong> the<br />

buildings.<br />

Another study by Boussabaine<br />

et al. (2004) gave a slightly<br />

higher percentage <strong>of</strong> the design<br />

and construction life cycle cost<br />

at 22% as shown in Figure 3,<br />

which allows the whole life cycle<br />

cost (WLC) to be compared and<br />

controlled. This benchmarking<br />

cost is a recent guideline for<br />

projects procured using the<br />

PFI route (Boussabaine et al.,<br />

2004).<br />

For efficiency, the project lifecycle<br />

cost should be seen in totality<br />

from design to maintenance. Lifecycle<br />

operations and maintenance<br />

(O&M) and capital renewal costs,<br />

however, almost always comprise<br />

a far greater percentage <strong>of</strong> the<br />

total lifecycle building costs<br />

(Selman, 2004). For example,<br />

decisions made at the design<br />

stage <strong>of</strong> a project could have<br />

significant long-term effects. A<br />

study by Minami (2004) in Japan<br />

suggested that a reduction became<br />

apparent in facilities investment<br />

costs in terms <strong>of</strong> the relationship<br />

between the rebuilding cycle,<br />

rebuilding and repair, by changing<br />

the present rebuilding from 40 to<br />

building additions at age 40, and<br />

rebuilding at age 60.<br />

The way forward taken by the<br />

industry is more integrated, better<br />

exchange <strong>of</strong> data and seamless<br />

c o m m u n i c a t i o n a m o n g t h e<br />

construction players throughout<br />

the lifecycle <strong>of</strong> the project<br />

(Construction 21, 1999; McKinsey,<br />

1995; Lafford et al., 2000).<br />

FM Within the Construction<br />

Industry<br />

Latham (1994) and Egan<br />

(1998) have produced documents<br />

entitled Constructing the team<br />

and Rethinking Construction<br />

respectively, as guidelines for<br />

improving the UK construction<br />

industry. The essence <strong>of</strong> their<br />

initiatives is to bring improvement<br />

to the industry through partnering,<br />

a n d b e t t e r c o m m u n i c a t i o n<br />

by means <strong>of</strong> integrating the<br />

construction value chain. This<br />

approach encourages the seamless<br />

transfer <strong>of</strong> information and better<br />

communication among players<br />

throughout the life-cycle from<br />

design to FM.<br />

Egan (1998) recognised the<br />

need for construction and facilities<br />

managers to work together as part<br />

<strong>of</strong> an integrated team to improve<br />

results to reduce maintenance<br />

expenditure. Teicholz (2004)<br />

identified the need to bridge<br />

the gap between design and<br />

construction, and FM is becoming<br />

<strong>of</strong> critical importance to clients<br />

and is <strong>of</strong>ten raised by industry<br />

players.<br />

Ineffective communication<br />

practices adopted by project<br />

participants throughout the<br />

construction life-cycle (Emmerson,<br />

1962; Banwell, 1964; Higgins and<br />

Jessop, 1965) have contributed<br />

to the productivity decline in<br />

construction. Important information<br />

relevant to FM activities is<br />

frequently missed and not<br />

captured, resulting in unnecessary<br />

reworking to obtain the needed<br />

details. In order to avoid this<br />

situation FM stakeholders and<br />

construction players are required<br />

to discuss and determine the<br />

mechanism for improvement.<br />

Important information on<br />

building structural elements, for<br />

example on the load carrying<br />

capacity <strong>of</strong> columns, load bearing<br />

walls or suspended slabs, must be<br />

recorded in as-built drawings as<br />

digitised or hardcopy and passed<br />

to the client from the contractor<br />

once the building project is<br />

completed. This building element<br />

information is also important in<br />

asset management for example,<br />

when purchasing equipment<br />

and machinery, since facilities<br />

managers need to be able to<br />

ensure that new purchases <strong>of</strong><br />

this kind will actually fit into<br />

the space available and will<br />

be most appropriately and safely<br />

sited from the start, rather than<br />

having to learn by trial and error.<br />

This information must be readily<br />

accessible by the client during the<br />

operation and maintenance <strong>of</strong> the<br />

building when it is required.<br />

Major relevant information not<br />

captured during the construction<br />

stage result in poor FM performance<br />

later. An example is information<br />

on a wall detail drawing presented<br />

in an as-built drawing with<br />

insufficient information on its<br />

design. If the design property <strong>of</strong><br />

the wall is not indicated and it<br />

is not known whether it is a load<br />

bearing wall or a partition wall, it<br />

is difficult to arrive at the proper<br />

decision when renovation work<br />

is required since demolishing the<br />

wall for renovation purposes may<br />

be risky, but on the other hand,<br />

assuming that a partition wall is<br />

actually a load bearing wall will<br />

affect the structural integrity <strong>of</strong><br />

the building if undue pressure is<br />

exerted on it.<br />

C o n s t r u c t i o n - r e l a t e d<br />

information such as information<br />

on building elements is not<br />

for the sole use <strong>of</strong> building<br />

m a i n t e n a n c e a n d p r o p e r t y<br />

management but is also required<br />

during the support function, for<br />

instance in landscaping, furniture<br />

management and environmental<br />

management.<br />

Design, Build, Operate and<br />

Transfer <strong>Pro</strong>curement<br />

The concept <strong>of</strong> the project<br />

life-cycle has made Government<br />

agencies, facilities managers, key<br />

construction players, employers<br />

and clients, all work closely<br />

together to produce better results<br />

throughout the project life-cycle.<br />

Maintenance and operation <strong>of</strong><br />

facilities is <strong>of</strong>ten taken as an<br />

isolated and frequently neglected<br />

aspect in the life-cycle construction<br />

approach. Design, Build, Operate<br />

and Transfer (DBOT) or the PFI<br />

method <strong>of</strong> procurement has<br />

brought together construction<br />

players and FM stakeholders<br />

enabling better communication<br />

that could produce improved<br />

construction services and products

THE INGENIEUR COVER FEATURE<br />

17<br />

<strong>Pro</strong>curement<br />

type<br />

Design, Build,<br />

Operate &<br />

Transfer (DBOT)<br />

or PFI<br />

Design & Build<br />

<strong>Pro</strong>curement<br />

Traditional<br />

<strong>Pro</strong>curement<br />

(Dixon et. al, 2003). Authorities<br />

and contractors will achieve a<br />

successful partnership where<br />

they each meet their respective<br />

objectives over the life <strong>of</strong> the<br />

project (Comptroller and Auditor<br />

General, 2001).<br />

The global trend indicates<br />

that traditional procurement is<br />

being phased out and replaced<br />

by design and build (D&B)<br />

procurement and is gradually<br />

moving towards Design, Build,<br />

Operate and Transfer (DBOT) or<br />

the PFI procurement type which is<br />

seen to provide better integration<br />

as shown in Figure 4.<br />

The strength and benefit <strong>of</strong><br />

DBOT procurement has influenced<br />

many countries in the world to<br />

put it into practice, and as a result<br />

<strong>of</strong> implementing this method, the<br />

Australian construction industry<br />

is witnessing a greater level <strong>of</strong><br />

integration among players across<br />

the construction value chain<br />

(McKinsey, 1995). Similarly, in<br />

Singapore where the Government<br />

has taken initiatives to allow<br />

the integration <strong>of</strong> AEC players<br />

in construction projects at an<br />

Improve integration, communication<br />

Design Tender Construction<br />

Consultant Owner Contractor<br />

Key<br />

Tasks/Activities<br />

Develop<br />

conceptual<br />

designs<br />

Obtain<br />

planning<br />

approvals<br />

Owner/DBOT/PFI Consortium<br />

Consultant/Contractor Owner<br />

Develop tender<br />

specifications<br />

Ascertain bills <strong>of</strong><br />

quantity<br />

Put up invitation to<br />

tender<br />

Submission <strong>of</strong> tender<br />

Evaluation <strong>of</strong><br />

proposals<br />

Award <strong>of</strong> tender<br />

Drawing up contracts<br />

and liabilities<br />

Figure 4 Improve Communication Through <strong>Pro</strong>curement<br />

Obtain various<br />

permits (e.g.<br />

factory permits,<br />

work permits etc.)<br />

Mobilisation <strong>of</strong><br />

resources<br />

Construction<br />

<strong>Pro</strong>ject<br />

management<br />

early stage (Construct 21, 1999),<br />

collaboration between the owner,<br />

the pr<strong>of</strong>essionals and the builders<br />

has been intensified. The use <strong>of</strong><br />

the design-build project delivery<br />

method in Singapore, while<br />

barely 10 years old, has risen<br />

to a 20% share <strong>of</strong> the public<br />

sector construction market, which<br />

in turn dominates the Singapore<br />

construction industry with a 60%<br />

share (Neo, 2001).<br />

Fragmentation is minimised<br />

through DBOT by bringing all<br />

parties on board right from<br />

the onset <strong>of</strong> the construction<br />

project. This allows the seamless<br />

transfer <strong>of</strong> information by cutting<br />

down red tape and paperwork.<br />

Variation orders are carried out<br />

much faster as instruction is given<br />

directly to the DBOT consortium,<br />

unlike in the traditional method<br />

<strong>of</strong> procurement where work is<br />

carried out after going through<br />

many layers, moving first from the<br />

owner who gives the instruction<br />

order to the consultant who later<br />

passes the instruction to the<br />

contractor to carry out the job.<br />

As a result, the delays in giving<br />

Facilities<br />

Management<br />

Owner<br />

Maintain 1-year<br />

defect liability and<br />

structural defect<br />

liability<br />

Carry out remedial<br />

work<br />

Maintenance<br />

management<br />

<strong>Pro</strong>perty<br />

management<br />

Serv<br />

operation<br />

Improve integration, communication<br />

instructions for DBOT projects<br />

are reduced, and projects can be<br />

completed earlier and be ready<br />

for occupancy.<br />

In the maintenance and<br />

operation <strong>of</strong> a building, the<br />

seamless transfer <strong>of</strong> information<br />

and proper sharing are evident<br />

among all the parties within<br />

the management <strong>of</strong> one DBOT<br />

consortium. It is also possible<br />

to transfer relevant information<br />

for the use <strong>of</strong> the organisation’s<br />

support services without difficulty,<br />

as the controlling authority also<br />

comes from the same DBOT<br />

consortium.<br />

Construction Versus Support<br />

Service Views<br />

The American and the British<br />

approach to FM functions differ.<br />

In her research, Maliene (2005)<br />

identified the development <strong>of</strong><br />

FM as coming from two different<br />

schools <strong>of</strong> thought:<br />

● American - FM is focused<br />

o n wo r k p l a c e e f f i c i e n cy<br />

a n d m a n a g e m e n t o f t h e

18 COVER FEATURE<br />

THE INGENIEUR<br />

facilities; the main target is<br />

the physical workplace (Tay<br />

and Ooi, 2001; Cotts and<br />

Lee 1992),<br />

● B r i t i s h - F M i s f o c u s e d<br />

o n i n t e g r a t e d s e r v i c e s ,<br />

h e a l t h a n d p r o d u c t iv i t y,<br />

improvement <strong>of</strong> the work<br />

environment and employees;<br />

the most attention is paid<br />

Maintenance/Operation<br />

Management<br />

Monitoring/<br />

Tracking<br />

Maintenance/<br />

Alteration/<br />

Repair<br />

Space<br />

Management<br />

Figure 5 Identifiable FM Functions (IFMA, 1997)<br />

to the core business and<br />

employee support (Maliene,<br />

2005).<br />

In order to have a clear view<br />

on FM functions, the author has<br />

categorised group maintenance<br />

and operation management and<br />

also property management as<br />

construction-related activities,<br />

while services and performance<br />

Identifiable Facilities Management (FM) Functions<br />

Group 1 - FM definition Group 2 - FM definition<br />

Asset Accounts<br />

Functional Performance<br />

Track Cost Value<br />

Track Operation Cost<br />

Track Life Cycle Cost<br />

Energy Consumption<br />

Operation Efficiency<br />

Specification/<br />

Configuration<br />

<strong>Pro</strong>curement/Installation<br />

Preventive Maintenance<br />

<strong>Pro</strong>ject Execution<br />

<strong>Pro</strong>blem Identification/<br />

Allocation<br />

Space Use Management<br />

Move Management<br />

<strong>Pro</strong>perty Management<br />

Building Assessment<br />

Site Selection/<br />

Acquisition<br />

Rent Management<br />

Lease Management<br />

Building Purchase<br />

Advertising<br />

Public Relations<br />

Area Measurement/<br />

Calculation<br />

Space Allocation<br />

Space Assignment<br />

Space Suitability<br />

Assessment<br />

Space <strong>Pro</strong>gramming<br />

Space Forecasting/<br />

Planning<br />

Post-occupancy<br />

Evaluation<br />

Placement <strong>of</strong> Signs<br />

have been grouped as a support<br />

to the primary objectives <strong>of</strong> the<br />

organisation. In North America<br />

the FM functions are popularly<br />

c l a s s i f i e d i n t o t h r e e b a s i c<br />

categories: maintenance and<br />

operation management, property<br />

m a n a g e m e n t , a n d s e r v i c e s<br />

(IFMA, 1997). Figure 5 shows<br />

the Identifiable functions <strong>of</strong> FM<br />

by the IFMA (1997).<br />

Services<br />

Warehouse<br />

Management<br />

Custodian<br />

Work Planning<br />

Copy/Printing<br />

Services<br />

Hazardous/<br />

Recycling<br />

Emergency<br />

Planning<br />

Fire <strong>Pro</strong>tection<br />

Security<br />

Services<br />

Occupancy<br />

Planning<br />

Stacking/<br />

Blocking<br />

Floor Layout<br />

Furniture<br />

Design<br />

FM related to design and construction - Group 1 FM as services in the organisation - Group2

THE INGENIEUR COVER FEATURE<br />

19<br />

Maintenance and operation<br />

management is further classified<br />

into the three interrelated<br />

function areas; monitoring and<br />

tracking, maintenance, alteration/<br />

repairing, and space management<br />

(IFMA, 1997). Sub-functions <strong>of</strong><br />

each <strong>of</strong> these areas are also<br />

defined. On the other hand,<br />

the IFMA outlines some <strong>of</strong> the<br />

FM functions under services as<br />

including warehouse management,<br />

work planning, printing services,<br />

recycling, emergency planning,<br />

fire protection and security<br />

services. The functions <strong>of</strong> FM are<br />

further divided accordingly, based<br />

on the two groups identified in<br />

the previous section for ease <strong>of</strong><br />

discussion.<br />

Furthermore, discussion and<br />

research forums between leading<br />

FM organisations and the Centre<br />

<strong>of</strong> Facilities Management (CFM),<br />

as a leading centre in the UK,<br />

have identified seven categories<br />

<strong>of</strong> FM services as follows (CFM,<br />

2004):<br />

Facilities Management (FM) Functions<br />

Group 1 - FM definition Group 2 - FM definition<br />

Design<br />

Construction<br />

Building operations and<br />

maintenance<br />

1. Electrical<br />

2. Fabric<br />

3. Grounds<br />

4. Mechanical<br />

5. Specialist equipment<br />

<strong>Pro</strong>perty Management<br />

1. Space planning<br />

2. Asset management<br />

3. <strong>Pro</strong>ject management<br />

4. Design/Construction<br />

5. Disposals/Acquisition<br />

6. Relocation<br />

management<br />

Infrastructure<br />

1. Utilities (gas, water,<br />

electricity)<br />

2. Road<br />

Environmental<br />

management<br />

1. Energy management<br />

2. Health and safety<br />

3. Hygiene services<br />

4. Pest control<br />

5. Waste management<br />

Information<br />

Technology and<br />

Telecommunications<br />

FM related to design and construction – Group 1<br />

FM as services in the organisation – Group 2<br />

1. IT advisory services<br />

2. IT R&D<br />

3. Information services<br />

4. Management<br />

information systems<br />

5. Technical services<br />

6. Systems administration<br />

and management<br />

7. Computer/server<br />

8. CAFM systems (CAD,<br />

PPM, GIS, DSS, etc<br />

9. Customer<br />

response/support<br />

10.Network services and<br />

Management<br />

11. Cable management<br />

12. Telecommunication<br />

systems and services<br />

13. Network and<br />

telecommunications<br />

Figure 6 FM Function derived from Centre for FM (UK)<br />

1. Building operations and<br />

maintenance<br />

2. Support services which include<br />

catering, porter service,<br />

cleaning and security<br />

3. Information Technology and<br />

telecommunications<br />

4. Transport<br />

5. <strong>Pro</strong>perty management<br />

6. Infrastructure<br />

7. Environment management<br />

The above categories have<br />

been grouped together according<br />

Services and performance<br />

Support Services<br />

1. Catering and<br />

vending services<br />

2. Cleaning<br />

3. Courier services<br />

4. Furniture<br />

management<br />

5. Landscape internal<br />

6. Laundry<br />

7. Mail room<br />

8. Office support<br />

services<br />

9. On-site moves<br />

10. Porterage<br />

11. Reception<br />

12. Security<br />

13.Travel<br />

14. Library<br />

15. Shops/retail<br />

Transport<br />

1. Fleet management<br />

2. Site transportation<br />

3. Vehicle renting and<br />

leasing<br />

Business support<br />

services in client<br />

organisations<br />

1. Administration<br />

2. Finance<br />

3. Human resource<br />

4. <strong>Pro</strong>curement

20 COVER FEATURE<br />

THE INGENIEUR<br />

to design and construction<br />

(Group 1), service/performance<br />

and Information Technology<br />

(Group 2) as in Figure 6. Figures<br />

5 and 6 enable the reader to<br />

appreciate the difference between<br />

the approach commonly used in<br />

America and the CFM in the UK.<br />

The main difference is seen in<br />

the services function <strong>of</strong> FM.<br />

The American interpretation<br />

places more emphasis on the<br />

physical workplace but this<br />

does not mean that there is less<br />

interest in FM services functions<br />

in this approach. On the other<br />

hand, the CFM in the UK, has<br />

a focus which is more towards<br />

the services output for FM rather<br />

than the physical workplace.<br />

Kuala Lumpur International Airport<br />

The inclusion <strong>of</strong> IT and<br />

t e l e c o m m u n i c a t i o n s h a s<br />

stressed its importance as one<br />

<strong>of</strong> the functions <strong>of</strong> FM in<br />

the provision <strong>of</strong> integrated<br />

services for improvement <strong>of</strong> the<br />

work environment, employee<br />

satisfaction, and the sharing<br />

<strong>of</strong> design and construction<br />

information with other FM<br />

stakeholders.<br />

Recommendation<br />

FM must be considered as<br />

part <strong>of</strong> any PFI initiatives. The<br />

concept <strong>of</strong> PFI and the definition<br />

<strong>of</strong> FM must be clearly defined<br />

and understood. There is yet to<br />

be an agreeable definition <strong>of</strong> FM<br />

among the construction industry<br />

players and, property developers<br />

in <strong>Malaysia</strong>.<br />

In <strong>Malaysia</strong> even though the<br />

concept <strong>of</strong> PFI is relative new<br />

but the practice on partnering<br />

has taken placed as early as the<br />

80’s. These included the use <strong>of</strong><br />

design, build and operate contract<br />

on infrastructure and building<br />

projects. These experiences could<br />

be tapped and learned<br />

PFI is about partnering, risk<br />

transfer and trust which emphase<br />

the importance <strong>of</strong> whole life cycle<br />

approach. The strength <strong>of</strong> PFI lies<br />

on the following:<br />

● Benefit <strong>of</strong> project to owner,<br />

concessionaire, public (winwin<br />

approach)<br />

● <strong>Pro</strong>curement strategy<br />

● Strategic partnering<br />

● Risk transfer valuation<br />

● Innovation<br />

● C o n t r a c t a n d p r o j e c t<br />

management experience<br />

● Interaction <strong>of</strong> all parties at<br />

onset <strong>of</strong> the construction<br />

project<br />

PFI must be looked in a<br />

holistic view which incorporate<br />

design, construction related<br />

activities on one side and<br />

operation, maintenance (i.e. FM)<br />

on the other side. It shall be<br />

a win-win situation approach<br />

that fulfills client-concessionairepublic/customer<br />

satisfaction.<br />

As the agreement between<br />

the client and concessionaire<br />

will last between 30 and 35<br />

years, a careful and thorough<br />

examination on cost and benefit<br />

analysis must be done prior to<br />

adopting PFI in any construction<br />

project.<br />

In order to successfully practice<br />

PFI in <strong>Malaysia</strong>, it requires a<br />

combination between experts<br />

(i.e. client/owner, concessionaire<br />

and public) in project and<br />

contract management, facilities<br />

management, economist, social<br />

sciences to be on board right at<br />

the onset <strong>of</strong> any potential PFI<br />

project discussion. <strong>BEM</strong>

THE INGENIEUR COVER FEATURE 21<br />

REFERENCES<br />

Alexander, K. Facilities management:<br />

creating the platform for business<br />

value by, Director, Centre for<br />

Facilities Management, University<br />

<strong>of</strong> Salford, 2003 http://fm.atalink.<br />

co.uk/articles/article-81.phtml.<br />

Alexander K. A Strategy for facilities<br />

management Facilities, 1 November<br />

2003a, vol. 21, no. 11-12, pp. 269-<br />

274(6) Emerald Group Publishing<br />

Limited<br />

Allen, S., Lenard, D. (2004)<br />

Private Finance and Public Private<br />

Partnerships – A review, Centre for<br />

Construction Innovation. http://<br />

www.ccinw.com/ . Accessed on<br />

21 st . December, 2004<br />

Alshawi, M., Faraj, I. (2002),<br />

I n t e g r a t e d c o n s t r u c t i o n<br />

environments: technology and<br />

implementation, Construction<br />

Innovation 2002;2: 33-51, Arnold<br />

A m o r . R . , B e t t . M . , 2 0 0 1 ,<br />

I n f o r m a t i o n T e c h n o l o g y f o r<br />

Construction: Recent Work and<br />

Future Directions, CIB World<br />

Building Congress, April, 2001,<br />

Wellington, New Zealand.<br />

Aouad, G. and Alshawi, M. 1996:<br />

Priority Topics for Construction<br />

I n f o r m a t i o n T e c h n o l o g y ,<br />

International Journal <strong>of</strong> Construction<br />

Information Technology 4, 45-66.<br />

Badawi, Abdullah A. Datuk Seri<br />

(2001) The Deputy Prime Minister<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Malaysia</strong>, (February 2001), The<br />

Star (newspaper), <strong>Malaysia</strong>.<br />

Banwell, H. 1964: Report <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Committee on the Placing and<br />

Management <strong>of</strong> Contracts for<br />

Building and Civil Engineering<br />

Work. HMSO, UK.<br />

Barrett, P & Baldry, D (2003)<br />

Facilities Management Towards<br />

Best Practice, Blackwell Publishing,<br />

Oxford, UK, 2003<br />

Betts, M. editor, 1999: Strategic<br />

Management <strong>of</strong> IT in Construction,<br />

Blackwell Science.<br />

Boussabaine, H. A., Kirkham, R.<br />

J. (2004) Whole Life-cycle costing<br />

Risk and Risk Responses, Blackwell<br />

Publishing.<br />

Brandon, P.S. (1999) <strong>Pro</strong>cess/<br />

<strong>Pro</strong>duct Development in 2000<br />

Beyond, Berkeley-Stanford CE&M<br />

Workshop, Stanford 1999.<br />

Brandon, P, Smith, D, Betts, M.<br />

1997: Creating a Framework For<br />

IT in Construction http://www.scpm.<br />

salford.ac.uk/meeting/docs/papers/<br />

paper1/paper1.htm.<br />

Brandon, P. 2000: Construction<br />

IT: Forward to what? - Keynotes<br />

Paper, INCITE 2000 Implementing<br />

IT to obtain a competitive advantage<br />

in the 21 st . Century, Conference<br />

<strong>Pro</strong>ceedings, 17-18 January, Hong<br />

Kong, 1-15.<br />

Construction 21. 1999: Published by<br />

Ministry <strong>of</strong> Power and Ministry <strong>of</strong><br />

Development Singapore.<br />

Civil Engineering Design and<br />

Guide: A guide to integrating design<br />

into construction process, 2000:<br />

CIRIA,DETR UK<br />

Dixon, T, Jordan, A, Marston,<br />

A, Pinder, J, Pottinger, G. (2003)<br />

Lessons from UK PFI and Real Estate<br />

Partnerships - drivers, barriers and<br />

critical success factors, College <strong>of</strong><br />

Estate Management, Reading.<br />

Eden, J. Chen S.E. and McGeorge,<br />

D. 2000: Australian Government<br />

Initiatives in IT Take Up, INCITE<br />

2000 Implementing IT to obtain a<br />

competitive advantage in the 21 st .<br />

Century, Conference <strong>Pro</strong>ceedings,<br />

17-18 January, Hong Kong, 197-<br />

208.<br />

Egan, Sir John. 1998: Rethinking<br />

Construction, Department <strong>of</strong> Trade<br />

and Industry.<br />

Emmerson, H. 1962: Survey <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Pro</strong>blems Before the Construction<br />

Industries. HMSO, UK.<br />

Fischer, M., John Kunz (2004)<br />

TR156: The Scope and Role<br />

<strong>of</strong> Information Technology in<br />

Construction<br />

http://www.stanford.edu/group/CIFE/<br />

Publications/index.html<br />

Hamid, Z, Sarshar, M. (2003),<br />

Specification <strong>of</strong> a Strategy to Facilitate<br />

the Effective Integration <strong>of</strong> ICT in<br />

the <strong>Malaysia</strong>n Construction Industry,<br />

Paper submitted to Construction<br />

Innovation Journal for publication.<br />

(Submitted on 8 th . May, 2003)<br />

Hamid, Z., Alshawi (2004), Strategic<br />

Information Systems Planning<br />

Requirements in Facilities Management<br />

for health Sector – A Plan for<br />

Technology Transfer to <strong>Malaysia</strong>n<br />

Construction Industry INCITE 2004-<br />

World IT for Design and Construction<br />

Langkawi, <strong>Malaysia</strong>: 18-21 February<br />

2004, CIDB <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

Higgins, G. & Jessop, N. (1965).<br />

Communications in the Construction<br />

Industry: the Report <strong>of</strong> a Pilot Study.<br />

Tavistock Institute, London.<br />

Kevin Yu, Thomas Froese and<br />

F r a n c o i s G r o b l e r ( 2 0 0 0 ) , A<br />

development framework for data<br />

models for computer-integrated<br />

facilities management, Automation<br />

in Construction Volume 9, Issue<br />

2, March 2000, Pages 145-167,<br />

Elsevier Science<br />

Kunz, J., Fischer, M., Haymaker,<br />

J., Levitt, R. 2002: Integrated and<br />

Automated <strong>Pro</strong>ject <strong>Pro</strong>cesses in<br />

Civil Engineering: Experiences<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Center for Integrated<br />

Facility Engineering at Stanford<br />

University. CIFE Technical Report<br />

# 132 February, 2002. Stanford<br />

University.<br />

Latham, Sir Michael. 1994:<br />

Constructing the Team. HMSO.<br />

Nayanthara de Silva, M.F.Mohammed<br />

F. Dulaimi , , Florence Y. Y. Ling<br />

and George Ofori, 2004: Building<br />

and Environment, Volume 39,<br />

Issue 10 , October 2004, Pages<br />

1243-1251 Elsevier Ltd.<br />

Ng., ST. Chen. SE, McGeorge<br />

D, Lam K-C and Evans, S.<br />

2001: Current state <strong>of</strong> IT usage<br />

by Australian subcontractors,<br />

Construction Innovation, Volume<br />

1, Number 1, 2001, Arnold.<br />

Sarshar. M, Betts. M, Abbott,<br />

C. Aouad, G.(2000) A vision<br />