Download - London Chess Centre

Download - London Chess Centre

Download - London Chess Centre

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

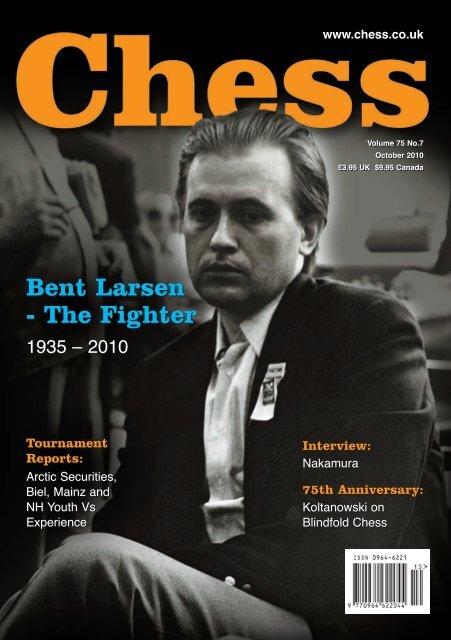

Bent Larsen<br />

- The Fighter<br />

1935 – 2010<br />

Tournament<br />

Reports:<br />

Arctic Securities,<br />

Biel, Mainz and<br />

NH Youth Vs<br />

Experience<br />

www.chess.co.uk<br />

Volume 75 No.7<br />

October 2010<br />

£3.95 UK $9.95 Canada<br />

Interview:<br />

Nakamura<br />

75th Anniversary:<br />

Koltanowski on<br />

Blindfold <strong>Chess</strong>

<strong>Chess</strong><br />

<strong>Chess</strong> Magazine is published monthly.<br />

Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc †<br />

Editor: Jimmy Adams<br />

Acting Editor: John Saunders<br />

Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein<br />

Subscription Rates:<br />

United Kingdom<br />

1 year (12 issues) £44.95<br />

2 year (24 issues) £79.95<br />

3 year (36 issues) £109.95<br />

Europe<br />

1 year (12 issues) £54.95<br />

2 year (24 issues) £99.95<br />

3 year (36 issues) £149.95<br />

USA & Canada<br />

1 year (12 issues) $90<br />

2 year (24 issues) $170<br />

3 year (36 issues) $250<br />

Rest of World (Airmail)<br />

1 year (12 issues) £64.95<br />

2 year (24 issues) £119.95<br />

3 year (36 issues) £170<br />

Distributed by:<br />

Post Scriptum (UK only)<br />

Unit G, OYO Business Park, Hindmans Way,<br />

Dagenham, RM9 6LN<br />

Tel: 020 8526 7779<br />

LMPI (North America)<br />

8155 Larrey Street, Montreal (Quebec),<br />

H1J 2L5, Canada<br />

Tel: 514 355-5610<br />

Printed by:<br />

The Magazine Printing Company (Enfield)<br />

Te: 020 8805 5000<br />

Views expressed in this publication are not<br />

necessarily those of the Editor.<br />

Contributions to the magazine will be published at<br />

the Editor’s discretion and may be shortened if<br />

space is limited.<br />

No parts of this publication may be reproduced<br />

without the prior express permission of the<br />

publishers.<br />

All rights reserved. © 2010<br />

<strong>Chess</strong> Magazine (ISSN 0964-6221) is published by:<br />

<strong>Chess</strong> & Bridge Ltd, 44 Baker Street, <strong>London</strong>,<br />

W1U 7RT<br />

Tel: 020 7388 2404 Fax: 020 7388 2407<br />

info@chess.co.uk – www.chess.co.uk<br />

FRONT COVER:<br />

Bent Larsen (1935-2010), shown around the time he<br />

had his fateful meeting with Bobby Fischer in their<br />

1971 match. Photo: CHESS Magazine Archive<br />

US & Canadian Readers – You can contact us<br />

via our American branch – <strong>Chess</strong>4Less based<br />

in West Palm Beach, FL. Call us toll-free on<br />

1-877 89CHESS (24377). You can even order<br />

Subscriber Special Offers online via<br />

www.chess4less.com<br />

Contents<br />

Editorial<br />

Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in chess<br />

Obituary: Bent Larsen (1935-2010)<br />

John Saunders pays tribute to the popular, inventive and<br />

brilliant Danish grandmaster, who has just died<br />

Arctic Securities <strong>Chess</strong> Stars<br />

Vishy Anand and Magnus Carlsen clash in Norwegian rapid<br />

Tournament Report: Biel Young GMs<br />

David Howell featured in the prestigious event in Switzerland<br />

Tournament Report: NH Rising Stars v Experience<br />

Boris Gelfand in top form but the youngsters triumphed<br />

Mainz <strong>Chess</strong> Classic<br />

Malcolm Pein was in Germany to sample the monster rapidplay<br />

Arctic <strong>Chess</strong> Challenge, Tromso<br />

Another visit to the Arctic! Chris Briscoe was one of an<br />

intrepid party of Brits who ventured to this splendid event<br />

How Good is Your <strong>Chess</strong><br />

Daniel King features a game from the French Championship<br />

A Question of Authorship by Amatzia Avni<br />

Should we credit a computer for its compositional creativity?<br />

Anatoly Karpov Fund-Raiser in <strong>London</strong><br />

Karpov, Kasparov and Short campaigning in <strong>London</strong><br />

Readers’ Letters<br />

It’s a mad, mad, mad, mad chess world! Readers have their say<br />

Interview: Hikaru Nakamura<br />

The volatile American star talks candidly to Janis Nisii<br />

Retrograde Analysis by Jesús García Pacheco<br />

Look back in puzzlement! How did we get to this position?<br />

CHESS Magazine: 75 Years Young...<br />

A leaf through the archives: George Koltanowski on blindfold chess<br />

Find the Winning Moves<br />

Three pages of tactical teasers, including Larsen’s best finishes<br />

Half A League Onward!<br />

Where have all the players gone? Mike Hughes takes stock<br />

Positional Exercises<br />

GM Jacob Aagaard tests your positional IQ - tricky but rewarding<br />

Problem Album<br />

Colin Russ pays tribute to Robin Matthews who died recently<br />

Tournament Listings<br />

A Calendar of Congresses<br />

New Books in Brief<br />

The low-down on the latest releases<br />

Solutions<br />

The answers to Find the Winning Moves and Problem Album<br />

News Round-Up<br />

All the latest tournament news, and a selection of recent games<br />

www.chess.co.uk 3<br />

4<br />

7<br />

10<br />

12<br />

16<br />

21<br />

24<br />

27<br />

30<br />

33<br />

36<br />

37<br />

40<br />

43<br />

46<br />

49<br />

52<br />

52<br />

53<br />

54<br />

56<br />

57

Magnus Carlsen<br />

Conquers<br />

the World<br />

Magnus Carlsen’s career as a fashion model has really taken off. I can’t<br />

describe how disconcerting it was to see him staring at me from a huge wall<br />

poster at King’s Cross Station on my way in to work. The campaign for<br />

G-Star clothing, is also very prominent in New York with posters on buses.<br />

New York City was the venue for Magnus to take on the world in the ‘RAW<br />

<strong>Chess</strong> Challenge’, an online contest which, like every such event before it,<br />

put the internet servers it was being powered by under enormous strain.<br />

This did not prevent it being a great success.<br />

It was quite a nice game and I recommend watching the video at TWIC<br />

(www.chess.co.uk/twic). The World were assisted by Maxime Vachier-Lagrave<br />

of France, a former World Junior champion, Hikaru Nakamura, the US number<br />

one, and Judit Polgar, the greatest ever female player. Judit summed up the<br />

world’s dilemma: “There were too many cooks in the kitchen,” she said.<br />

Photos: G-Star RAW<br />

The World’s Team (from left to right) Hikaru Nakamura, Judit Polgar and Maxime Vachier-Lagrave<br />

Photo: G-Star RAW<br />

The three cooks in the kitchen: The World team work in isolation to offer their suggestions to the public<br />

Photo: G-Star RAW<br />

Top of the class: Magnus with his mentor , Garry Kasparov,<br />

and his fellow G-Star model, actress Liv Tyler<br />

Magnus Carlsen - The World<br />

RAW World <strong>Chess</strong> Challenge, New York<br />

Kings Indian Def. Uhlmann Variation<br />

1 d4 ¤f6 2 c4 g6 Narrowly beating<br />

2...e6 in the vote. 3 ¤f3 ¥g7 4 g3 0–0<br />

5 ¥g2 d6 6 ¤c3 ¤c6 7 0–0 e5 The<br />

Uhlmann Variation; 7...a6 is the Panno<br />

Variation. 8 d5 ¤e7 9 e4 c6 Opening the<br />

queenside favours White; I would play<br />

¤d7 or ¤e8. 10 a4 ¥g4 11 a5<br />

11...cxd5? Do not open the queenside!<br />

This gives White the c4 square. After the<br />

game, both Carlsen and Nakamura felt<br />

this was a big mistake preferring, £d7.<br />

12 cxd5 £d7 13 ¥e3 ¦fc8 Commentary<br />

on the official site crashed and Maurice<br />

Ashley was talking to himself, but not for<br />

long. This has happened at every big<br />

chess internet match since Deep Blue<br />

1997. I remember that one well - I was in<br />

the web room. 14 £a4 ¤e8 15 ¤d2 £d8<br />

16 £b4 ¤c7 17 ¤c4 I suspect Magnus<br />

www.chess.co.uk 5

6<br />

chose not to play the crushing 17 f3! ¥d7<br />

18 £xd6. The queen cannot be trapped:<br />

18...¤f5 19 exf5 ¥f8 20 £xe5. 17...¤a6<br />

18 £xb7 ¦xc4 19 £xa6 ¦b4 20 f3 ¥c8<br />

21 £e2 f5 22 £d2 ¥a6 23 ¦fc1 £b8 24<br />

¤a4 ¦b3 25 ¦c3 ¦b4<br />

26 ¦ca3! With the idea of ¤b6! winning<br />

the exchange. 26...f4 27 ¥f2 27 gxf4 exf4<br />

28 ¥xf4 might give Black some<br />

counterplay. 27...¥h6 28 ¤b6!?<br />

An interesting moment and the only<br />

occasion when Kasparov disagreed with<br />

Magnus. Garry wanted to keep total<br />

control with 28 g4 "and the game is over".<br />

Photo: G-Star RAW<br />

28...fxg3 29 £xb4 gxf2+ 30 ¢xf2 ¥c8?<br />

30...¥f4 was Magnus' suggestion here<br />

with some chances against White's king;<br />

30...axb6 31 axb6 ¥b7 32 ¦xa8 ¥xa8 33<br />

¥h3 wins. 31 ¦b3 axb6 32 £xb6 £a7 33<br />

a6 ¢f7 34 £xa7 ¦xa7 35 ¦b6 White's<br />

passed pawns are decisive in the<br />

endgame. 35...¢e8 36 ¦xd6 ¥f8 37 ¦b6<br />

¤xd5 38 ¦b8! ¥c5+ 39 ¢g3 ¤e7 40<br />

¥h3 ¢d8 41 ¥xc8 ¤xc8 42 ¦c1<br />

"Resign!" said Kasparov but that was<br />

because he had a bet on with Maurice<br />

Ashley on how long the game would last!<br />

42...¦c7 43 ¦xc5! ¦xc5 44 a7 1-0<br />

The Commentary Team: GM Maurice Ashley and actress / model Liv Tyler<br />

Photo: G-Star RAW<br />

To the victor go the spoils: Triumphant Magnus holds aloft the RAW World Challenge Trophy (pictured top-left)<br />

Bent Larsen<br />

(1935-2010)<br />

This month’s cover is of course devoted<br />

to Bent Larsen who died in Buenos Aires<br />

last month. Larsen’s uncompromising<br />

style, creativity and charm endeared him<br />

to the entire chess world. He defeated<br />

seven post-war world champions: Mikhail<br />

Botvinnik, Vassily Smyslov, Mikhail Tal,<br />

Tigran Petrosian, Boris Spassky, Bobby<br />

Fischer and Anatoly Karpov, and nearly<br />

always refused draws. He reached the<br />

Candidates’ semi-finals three times, only<br />

to be eliminated by Tal, Spassky and<br />

Fischer. Just recently Yasser Seirawan,<br />

in a lecture at our shop on Baker Street,<br />

was reflecting on how his recent book<br />

<strong>Chess</strong> Duels with the Champions was<br />

incomplete because he had so many<br />

more stories to tell about players who did<br />

not become world champion like… Bent<br />

Larsen! Larsen’s fearless will to win is<br />

matched by few nowadays. Perhaps<br />

only Veselin Topalov plays with such<br />

determination.<br />

Tickets are now on sale for the 2nd<br />

<strong>London</strong> <strong>Chess</strong> Classic and I look forward<br />

to meeting many readers there. Last year<br />

we were sold out at the weekends, so<br />

please book early. There are many side<br />

events to play in. Last year the weekend<br />

events were also full, so please register<br />

as early as you can.<br />

Please go to our online webshop or<br />

www.londonchessclassic.com for tickets<br />

and tournament entries. At time of writing<br />

the Viktor Korchnoi simuls were nearly<br />

full, so please do not delay if you want to<br />

play a chess legend.

The UK’s Strongest<br />

<strong>Chess</strong> Tournament EVER<br />

GM Michael<br />

Adams (ENG)<br />

2706 elo<br />

The UK’s<br />

Number 1<br />

GM Nigel<br />

Short (ENG)<br />

2690 elo<br />

The UK’s<br />

Number 2<br />

GM Luke<br />

McShane (ENG)<br />

2624 elo<br />

The UK’s<br />

Number 3<br />

GM David<br />

Howell (ENG)<br />

2616 elo<br />

The UK’s<br />

Number 4<br />

The <strong>London</strong> <strong>Chess</strong> Classic Schedule<br />

Wednesday 8th December Round 1 2.00pm<br />

Thursday 9th December Round 2 4.00pm<br />

Friday 10th December Round 3 2.00pm<br />

Saturday 11th December Round 4 2.00pm<br />

Sunday 12th December Round 5 2.00pm<br />

Monday 13th December REST DAY<br />

Tuesday 14th December Round 6 2.00pm<br />

Wednesday 15th December Round 7 12.00pm<br />

* Juniors must be under 16 on 08/12/2010 and accompanied by a paying adult. Proof of age may be required<br />

Purchasing an adult ticket gives you the following benefits:<br />

GM Magnus<br />

Carlsen (NOR)<br />

2826 elo<br />

The World<br />

Number 1<br />

GM Vishy<br />

Anand (IND)<br />

2800 elo<br />

The World<br />

Champion<br />

TICKETS ON SALE NOW<br />

Auditorium and GM Commentary<br />

(per day)<br />

Auditorium and GM Commentary<br />

Season Ticket (All 7 days)<br />

GM Vladimir<br />

Kramnik (RUS)<br />

2790 elo<br />

Former World<br />

Champion<br />

ADULT<br />

£10 weekday / £15 weekend<br />

JUNIOR *<br />

FREE for all days<br />

ADULT<br />

£50<br />

JUNIOR *<br />

- Admission to the <strong>London</strong> <strong>Chess</strong> Classic 2010 - Full access to the auditorium throughout the day’s play. Moves will be displayed on a<br />

giant screen - Access to the Grandmaster commentary room. Commentators will include: Former British champion GM Julian Hodgson,<br />

plus GM Stephen Gordon, IM Lawrence Trent and IM Malcolm Pein. Commentary line-up subject to change.<br />

FURTHER INFORMATION AT WWW.LONDONCHESSCLASSIC.COM<br />

GM Hikaru<br />

Nakamura (USA)<br />

2729 elo<br />

The American<br />

Number 1<br />

ORDER ONLINE: WWW.CHESS.CO.UK/SHOP OR CALL 020 7486 8222<br />

Olympia Conference <strong>Centre</strong>, Kensington, <strong>London</strong>, W14 8UX<br />

N/A

Just as we were preparing to go to<br />

press, the desperately sad news<br />

reached us that Bent Larsen had died.<br />

He is an important and muchcherished<br />

figure in chess and we will<br />

be devoting further pages to him in<br />

the November issue of the magazine.<br />

But we could scarcely let a month<br />

pass without publishing a shorter<br />

tribute to this remarkable chessplayer.<br />

Jørgen Bent Larsen (4 March 1935 - 9<br />

September 2010) was born in north-west<br />

Jutland in a country scarcely known for<br />

its chessplayers, except as the adopted<br />

home of the Latvian player and writer<br />

Aron Nimzowitsch, who died in<br />

Copenhagen just eight days after Larsen<br />

came into the world. Denmark can thus<br />

proudly claim to have been home to two<br />

of the finest players and most original<br />

thinkers ever to have graced chess.<br />

Naturally, Larsen’s earliest inspiration<br />

was fellow Dane Nimzowitsch and his<br />

great work My System.<br />

BEGINNINGS<br />

Larsen learnt chess aged six but, as he<br />

cheerfully admitted himself, he was not a<br />

prodigy. He was still very raw when, aged<br />

16, he made his first adventure into<br />

international chess at the inaugural World<br />

Junior Championship in Birmingham in<br />

1951. He lost in the first round and later<br />

to the English representative, Malcolm<br />

Barker, and the eventual runaway winner,<br />

Borislav Ivkov, to finish in a tie for fourth<br />

place, but this was actually a pretty good<br />

result considering his lack of experience.<br />

He finished eighth in the 1953 World<br />

Junior Championship but then made a<br />

big decision: to put his civil engineering<br />

studies on hold. A breakthrough followed<br />

in 1954 when he was chosen to play on<br />

board one for Denmark at the<br />

Amsterdam Olympiad and scored +11,<br />

=5, -3, which was the third best score on<br />

top board and enough to secure the IM<br />

title. He won the Danish title for the first<br />

time in the same year and repeated the<br />

performance every time he played in his<br />

national championship (six in all).<br />

The 1956 Moscow Olympiad took him<br />

from IM to GM and this time he secured<br />

the best score on top board ahead of<br />

world champion Botvinnik - +11, =6, -1.<br />

The loss, perhaps surprisingly, was to<br />

Scottish board one Fairhurst but he<br />

made up for it with wins against the likes<br />

of Gligoric, Padevsky, Porath, Prins,<br />

Czerniak, Blau and Golombek, and<br />

draws against Botvinnik, Szabo and<br />

Najdorf. Larsen’s comment on his<br />

Olympiad result is typical of his eternal<br />

optimism as a player but witty selfdeprecation<br />

as a writer and<br />

commentator: “This is the only<br />

tournament in which I have played better<br />

than I expected to do or thought possible<br />

beforehand!”. That winter he was able to<br />

return to England, five years after his<br />

mediocre Birmingham result, and share<br />

first place with Gligoric in the Hastings<br />

Premier. Larsen himself ascribed his<br />

success to a very good result at the<br />

Danish Championship which preceded it,<br />

where he won his first seven games in a<br />

row and romped home.<br />

Larsen himself regarded 1956 as his<br />

breakthrough year but his career was to<br />

have its ups and downs - a self-aware<br />

man, he made ‘ups and downs’ the title<br />

of the next chapter in his chess<br />

autobiography. He qualified for the 1958<br />

Portoroz Interzonal and travelled there<br />

expecting to qualify as a candidate but<br />

Photo: CHESS Magazine Archive<br />

Bent Larsen in <strong>London</strong> in 1973, giving move-by-move commentaries with Leonard Barden (left) during the<br />

Enfield weekend tournament organised by Edward Penn and which drew 612 players!<br />

he made a minus score, finishing a lowly<br />

16th out of 21. Writing about it ten years<br />

later, he could only say: “it was the<br />

greatest failure of my career. I cannot<br />

explain it.”<br />

This disappointment caused Larsen’s<br />

progress to stall somewhat for a number<br />

of years, as his career was interrupted by<br />

military service, a disagreement with his<br />

federation and a further flirtation with<br />

engineering studies. But he used his time<br />

sensibly, building his repertoire round<br />

more unorthodox openings, and came<br />

roaring back in 1964, sharing first place<br />

at the 1964 Amsterdam Interzonal.<br />

Hitherto he had not had many close<br />

encounters with the major Soviet stars<br />

but here he downed both Bronstein and<br />

Spassky. This took him into his first<br />

Candidates’ competition, now decided by<br />

matchplay. He did perhaps better than<br />

expected, beating Ivkov quite comfortably<br />

and only just losing out to Mikhail Tal in<br />

an exciting match in the semi-final. He<br />

later beat Geller in a play-off match for<br />

third/fourth place. This nine-game match,<br />

played in Copenhagen in 1966, is<br />

practically forgotten today, but it marked<br />

a milestone - it was the first time a Soviet<br />

grandmaster had lost a match to a<br />

‘foreigner’.<br />

www.chess.co.uk 7

8<br />

In 1966 Larsen took part in the<br />

Piatigorsky Cup in Santa Monica,<br />

alongside Spassky and Fischer, whose<br />

rivalry was gradually building as the<br />

finest tournament players of the era (the<br />

then world champion Tigran Petrosian did<br />

better in matches and team<br />

tournaments). After the first cycle, Larsen<br />

shared first place with Spassky on 6/9,<br />

with the American languishing in second<br />

to last place on an appalling 3½/9. But<br />

Fischer showed that chess, like football,<br />

can be a “game of two halves”, roaring<br />

back with 7½/9 in the second cycle, while<br />

Larsen could only muster 4/9. It wasn’t<br />

enough to catch Spassky but he finished<br />

a point clear of Larsen who took third.<br />

1967 AND ALL THAT<br />

At that time most chess fans around the<br />

world saw Bobby Fischer as the man<br />

most likely to loosen the Soviet<br />

stranglehold on the world title, but some<br />

remarkable results in 1967 transformed<br />

Larsen’s fortunes and status, making him<br />

a credible rival to Fischer when it came<br />

to the unofficial of ‘world’s best non-<br />

Soviet chessplayer’.<br />

Actually, it was really not much more than<br />

five months as Larsen’s results in the first<br />

half of 1967 were only so-so. He began<br />

one of the world’s greatest tournament<br />

streaks in Cuba in the middle of August.<br />

By the time he saw his home in Denmark<br />

again, just before Christmas, he had won<br />

four very strong tournaments - the<br />

Capablanca Memorial in Havana (ahead<br />

of Taimanov, Smyslov, Polugaevsky,<br />

Gligoric, etc - a monster 20-player event);<br />

Winnipeg (ahead of Keres and Spassky,<br />

tied with Darga); the Sousse Interzonal<br />

(ahead of Geller, Korchnoi, Gligoric,<br />

Portisch and many other super-GMs in a<br />

gargantuan 24-player field); and finally<br />

Palma de Mallorca (ahead of Smyslov,<br />

Botvinnik, Portisch, Gligoric, etc). As<br />

Larsen summarised it: “a total of 66<br />

tournament games in four months. I must<br />

repeat that this is absolutely crazy, and I<br />

shall probably never do it again. But it<br />

went fantastically well.”<br />

Crazy or not, this unprecedented streak<br />

changed the perception of who were the<br />

likely challengers for the world title held<br />

by Petrosian. Fischer, meanwhile, had<br />

also been playing exceptionally well but<br />

then sensationally absented himself from<br />

the Sousse Interzonal in a dispute over<br />

nothing in particular, thus ruling himself<br />

out of a world championship challenge<br />

for the next three years. Whether he liked<br />

it or not, Larsen was now the unofficial<br />

non-Soviet people’s champion.<br />

Larsen’s hot streak rumbled on into 1968.<br />

He won the Monaco tournament in April<br />

with a round to spare, ahead of Botvinnik<br />

and Smyslov, and went on to defeat<br />

Portisch in his Candidates’ quarter-final.<br />

However, his challenge foundered at the<br />

next fence as he lost to Spassky in the<br />

semi-final. Larsen blamed poor playing<br />

conditions in Malmö but, nothing daunted,<br />

went on to win the US and Canadian<br />

Opens in the summer of that year.<br />

Perhaps this is a good point at which to<br />

break, as Larsen had established himself<br />

as one of the best, if not the best,<br />

tournament players in the world. We’ll<br />

pick up the thread next month, with a<br />

wider look at Larsen’s later career, his<br />

writings, style of play and a wider<br />

selection of games.<br />

Zagreb 1965<br />

B.Larsen - A.Matanovic<br />

Catalan Opening<br />

1 c4 ¤f6 2 g3 e6 3 ¥g2 d5 4 ¤f3 ¥e7<br />

5 0–0 0–0 6 d4 ¤bd7 7 ¤bd2 c6 8 b3 b6<br />

9 ¥b2 ¥b7 10 ¦c1 10 £c2 and 10 ¤e5<br />

are frequently seen here. 10...¦c8 11 e3<br />

dxc4 12 ¤xc4! c5 13 £e2 cxd4 This<br />

seems to give White too much play. When<br />

Matanovic returned to this line a few<br />

years later, he tried 13...b5!? 14 ¤ce5 a6<br />

and went on to draw (against Lengyel in<br />

1970). 14 ¤xd4 ¥xg2 15 ¢xg2 ¤c5 16<br />

¦fd1 £d5+ 17 f3 ¦fd8 18 e4 18 ¤b5?<br />

runs into 18...¤d3! and the position is<br />

about equal. 18...£b7 19 ¤e5 ¥f8 20<br />

¦c2 ¦e8 If 20...¤fd7, White has 21 ¤dc6!<br />

¦e8 22 b4! ¤xe5 23 ¤xe5 and White will<br />

invade on d7. 21 ¦dc1 ¤fd7 22 ¤g4<br />

White does not want to free Black’s game<br />

with exchanges. 22 ¤c4!? is another<br />

option to maintain pressure, but Larsen is<br />

starting to look pointedly at Black’s<br />

kingside. 22...¤a6 Black could of course<br />

kick the knight away with 22...h5 but he<br />

might live to regret the break-up on his<br />

kingside pawn structure. 23 a3 At the time<br />

Larsen thought 23 ¦c4 was better but on<br />

reflection decided that it wasn’t, after<br />

23...¦xc4 24 £xc4 ¤ac5 25 b4 h5!, etc.<br />

23...¤ab8 24 ¦c4 a6 25 £c2 ¦xc4 26<br />

£xc4 b5 27 £c3! Larsen couldn’t find<br />

anything after 27 £c7 £xc7 28 ¦xc7 ¥d6,<br />

so he resumes his gaze at the kingside.<br />

27...b4 28 axb4 ¥xb4 29 £e3 ¥e7<br />

Understandably Black doesn’t want the<br />

white queen arriving on g5. 30 ¦c4<br />

30...¦c8?? Larsen thought 30...¤f6 was<br />

the best defence, and that even; 30...h5!?<br />

was possible. The text move he put down<br />

to Matanovic’s tiredness after four hours’<br />

work and an excessive eagerness to be<br />

rid of the pair of rooks. We must<br />

remember that the standard time control<br />

was 40 moves in 2½ hours in those days.<br />

It was good to have the extra thinking<br />

time but the strain of defending a difficult<br />

position over a long period could take its<br />

toll. 31 ¤xe6!? Computers find an<br />

alternative (and slightly more forceful)<br />

way to win: 31 ¤f5! ¦xc4 (31...exf5 loses<br />

to 32 £c3 as in the next note) 32 ¤xe7+<br />

¢f8 33 ¥xg7+! ¢xe7 34 £g5+ ¢e8 35<br />

bxc4 wins. 31...¦xc4? The text allows a<br />

very pretty finish. 31...f6!? 32 ¦xc8+<br />

£xc8 33 £d2 leaves White a clear pawn<br />

up with a better position; 31...fxe6? 32<br />

£c3 threatens both £xg7 mate and<br />

¦xc8+, so wins immediately. 32 ¤h6+!!<br />

1–0 32...¢h8 33 ¥xg7 mate; 32...gxh6 33<br />

£xh6 leads to mate.<br />

Photo: CHESS Magazine Archive<br />

Bent Larsen playing André Muffang of France at the Moscow Olympiad, 1956

SUBSCRIBING IS AN EASY MOVE TO MAKE...<br />

SUBSCRIBE<br />

SAVE<br />

Edited by Jimmy Adams. Contributors include:<br />

Danny King, Malcolm Pein, Neil McDonald, Jacob Aagaard,<br />

Richard Palliser, Gary Lane, Yochanan Afek, Chris Ward, Andrew Greet,<br />

Amatzia Avni, Gareth Williams, Chris Ravilious and many more.<br />

AND<br />

AS A SUBSCRIBER YOU RECEIVE 10% DISCOUNT ON ANY CHESS ITEM<br />

Subscribe online at www.chess.co.uk/shop<br />

Call us on 020 7388 2404<br />

Fill in this page and fax it to 020 7486 3355<br />

Post this page back to us - address details below<br />

(12 issues per year) 1 year (12 issues) 2 Years (24 issues) 3 Years (36 issues)<br />

United Kingdom £44.95 £79.95 £109.95<br />

Europe £54.95 £99.95 £149.95<br />

USA & Canada $90.00 $170.00 $250<br />

Rest of World (Airmail) £64.95 £119.95 £170<br />

COVER PRICE OF EACH ISSUE - £3.95<br />

Name............................................................................................<br />

Address........................................................................................<br />

........................................................................................................<br />

............................................Postcode.........................................<br />

Telephone (dayime).....................................................................<br />

Total amount payable £/$ ........................... enclosed*<br />

or please charge my credit card number shown.<br />

* cheques made payable to <strong>Chess</strong> & Bridge Ltd<br />

Visit us online:<br />

www.chess.co.uk<br />

Card Number .........................................................................<br />

Card Type (please check as appropriate)<br />

Note: We accept all major credit and debit cards<br />

Visa Mastercard Amex Switch Other<br />

Switch<br />

Issue No.<br />

Expiry<br />

Date<br />

<strong>Chess</strong> & Bridge Ltd - 44 Baker Street - <strong>London</strong> - W1U 7RT<br />

Tel: 020 7486 8222 Fax 020 7486 3355<br />

September 2010 August 2010<br />

July 2010 June 2010<br />

Security<br />

Code *<br />

* The security number is the LAST 3 digits printed in the signature area of<br />

the back of the card - we cannot charge your card without this number!<br />

Email us:<br />

info@chess.co.uk

30<br />

YEARS AGO, in the Pre-Fritz era,<br />

people had to analyse chess<br />

positions by themselves. That is<br />

true, children: preparation before a game<br />

was performed by humans.<br />

Admittedly, already in those distant days,<br />

some chess players did not rely<br />

exclusively on their own brains and opted<br />

for assistance from others. So, when a<br />

player won a game with a strong opening<br />

novelty or through deep adjournment<br />

analysis (another bygone phenomenon),<br />

it wasn't always clear if success was<br />

entirely the result of his own efforts.<br />

In the present computer age, combined<br />

effort in preparation for serious games<br />

has become an established norm. In the<br />

recent world championship match<br />

between Anand and Topalov (2010), the<br />

Bulgarian GM won the first game with 24<br />

¤xf6!, a move he had prepared at home<br />

with both human helpers and the backing<br />

of computer analysis.<br />

In one of his How Good is Your <strong>Chess</strong><br />

columns, GM Daniel King presented the<br />

following game:<br />

Prié - Svetushkin<br />

French Team Championship 2009<br />

1 d4 ¤f6 2 ¥f4 e6 3 e3 c5 4 c3 ¤c6<br />

5 ¤f3 d5 6 ¤bd2 ¥d6 7 ¥g3 0-0 8 ¥d3<br />

£e7 9 ¤e5 ¤d7 10 ¤xd7 ¥xd7?!<br />

11 ¥xd6 £xd6 12 dxc5 £xc5?!<br />

13 ¥xh7+!! (An astounding sacrifice,<br />

which apparently springs from nowhere)<br />

13...¢xh7 14 £h5+ ¢g8 15 ¤e4 £c4<br />

(15...g6 16 ¤xc5 gxh5 17 ¤xd7) 16 ¤g5<br />

¦fd8 (16...£d3 17 e4!) 17 £xf7+ with a<br />

very strong attack (1-0, 35 moves. See<br />

CHESS, September 2009, p. 6-9).<br />

An impressive finding, isn't it? But now,<br />

consider the following:<br />

¢ At www.chesspub.com on 11/11/2008,<br />

a user named AlanG proposed the<br />

same continuation, commenting after<br />

White's 15th move: "Analysing this<br />

with Fritz suggests White has a clear,<br />

maybe winning, advantage";<br />

¢ Three days later, GM Eric Prié<br />

responded on the same site: "Thanks<br />

a lot AlanG! This is an incredible trap";<br />

¢ Later it was found that all this had<br />

already happened In a<br />

correspondence game Kogler-Matheis,<br />

2007.<br />

So, Prié took the idea from another<br />

source, analysed it before the game and<br />

did it surely with the help of software.<br />

Now, in his game versus Svetushkin, Prié<br />

later found some brilliant moves ("The<br />

attack was pressed home with great<br />

vigour" - King), for which he should be<br />

praised. However, regarding only and<br />

specifically his 13 ¥xh7+, based on the<br />

previous information, I am reluctant to be<br />

impressed.<br />

Practical chess today is more a sport<br />

than art. Hence, all this doesn't matter<br />

much to tournament players. My idea,<br />

your idea, a computer move, whatever;<br />

as long as a point is gained, we are<br />

happy. However, things are different<br />

when it comes to the field of chess<br />

composition. Here, the question of the<br />

author's identity, the owner of the original<br />

idea, is very important. And it is here that<br />

computer advancement creates a<br />

difficulty.<br />

Consider the following example:

Amatzia Avni<br />

WHITE TO PLAY AND WIN<br />

This is a scheme that I toyed with a<br />

decade ago, the idea being 1 ¥c8+<br />

(1 ¥xd5?? £a1+) 1...¥e6 2 ¦xe6! Now, if<br />

(a) 2...£xc5+, then 3 ¦e3 when the double<br />

check by White's two undefended pieces is<br />

also a mate. Black improves with (b)<br />

2...¥f2+! (2...£a1+? 3 ¦e1+) when victory<br />

is achieved only by 3 ¢f1! ¥xc5 when<br />

4 ¦e3+ is no longer mate (4...¢h4) but, as<br />

the h-file is cleared, White has 4 ¦h6++!<br />

¢g3 5 ¦h3 mate up his sleeve.<br />

I liked this idea but in order to turn it into<br />

a serious study there had to be an<br />

additional refinement. Besides which, it is<br />

a blemish that the only function of §b4 is<br />

to avoid the alternative win 1 ¦b3+.<br />

As I couldn't find a decent introduction, I<br />

searched for gold in the variation 3...fxe6<br />

(instead of 3...¥xc5). But White soon wins<br />

with the mundane 4 £h5+ ¢g3 5 £g5+<br />

¢f3 (to avoid mate) 6 £g2+ ¢e3 7 £xf2+.<br />

I added a black pawn on h6 (to prevent<br />

£g5+) and strove to add another black<br />

pawn "somewhere". I put the work to<br />

Fritz. I was hoping for a unique winning<br />

line (otherwise the study would be<br />

unsound) and an "interesting" one. What<br />

exactly would make the line interesting, I<br />

had no idea. This is the most primitive<br />

use of computer for study composition -<br />

trial and error. Add a piece, move a file,<br />

change colours, let the machine analyse<br />

and deliver its verdict.<br />

In this particular case I was lucky. After<br />

only a few tries, I presented the following<br />

diagram for the machine's scrutiny:<br />

Now, after 1 ¥c8+ ¥e6 2 ¦xe6! ¥f2+!<br />

3 ¢f1! fxe6 4 £h5+ ¢g3, Fritz found<br />

that White has a unique, long, and<br />

peculiar winning line:<br />

5 £g6+ ¢h4 6 £xh6+ ¢g4 7 ¥xe6+<br />

¢f3 8 £h5+ ¢e4 9 £d5+ ¢e3 10 £e5+!<br />

¢f3 (10...¢d2 11 £b2+! wins on the<br />

spot) 11 ¥d5+ ¢g4<br />

12 ¢g2! (A surprisingly quiet move in the<br />

midst of all these checks. Black is<br />

defenceless) 12...£e3 13 ¥e6+ ¢h4<br />

14 £f6+ ¢h5 15 ¥f7+ ¢g4 16 £g6+<br />

¢h4 17 £h5 mate<br />

This study took 3rd commendation in The<br />

Problemist tourney for 2002-3. Who is<br />

the composer of this study? I published<br />

it under my own name, but in retrospect,<br />

naming the composers "Avni & Fritz"<br />

would probably have been more<br />

appropriate. I envisaged the first part, but<br />

from the fifth move on, I was just<br />

following the computer's analysis. The<br />

long and unique variation, the 12th quiet<br />

move - was entirely Fritz's contribution,<br />

not mine. Copying a line from a<br />

computer's screen can be described in<br />

various ways; one thing I'm sure, though:<br />

composing - it is not. The act of creation,<br />

using one's brain and imagination, is<br />

certainly not involved here.<br />

Some might argue that Fritz only<br />

facilitated my job and that in its absence I<br />

would have analysed this line and found<br />

its worth anyway. Maybe I would; more<br />

likely, I'd have given it up.<br />

Of course, chess software and databases<br />

enable smarter techniques than I have<br />

just described. Nalimov tablebases allow<br />

modern composers to get the verdict to<br />

all sub-seven piece endgames in an<br />

instant, and there are programs which<br />

make it possible to extract further<br />

information. Witness the following case:<br />

WHITE TO PLAY AND WIN<br />

1 ¥h1! (A startling winning move)<br />

1...¢c7 2 ¥f3 and White wins eventually,<br />

the position being a mutual zugzwang.<br />

Endgame expert John Beasley writes: "I<br />

have asked the then new database<br />

mining program "Wilhelm" (in 2003) to go<br />

through the definite database of ¢+¥+¤<br />

vs. ¢+¤ and to give me all the positions<br />

where ¥g2-h1 was the only winning<br />

move..." [the above diagram was one of<br />

those positions]. "I did not enter these<br />

positions for a formal tourney... I obtained<br />

(them) with no effort beyond the giving of<br />

a few commands to a machine." (ESBN<br />

6/2008)<br />

... and what do you think of the next<br />

position?<br />

WHITE TO PLAY AND WIN<br />

In order to win White must perform a<br />

remarkable manoeuvre:<br />

1 ¢b3! ¦b1+ 2 ¢c2 ¦b2+ 3 ¢d1 ¦b1+<br />

4 ¢e2 ¦b2+ 5 ¢f1 ¦b1+ 6 ¢g2 ¦b2+<br />

7 ¢h1 and the white king stays on this<br />

square for the next 105 moves, White<br />

capturing a black piece after a further 92<br />

moves. Great stuff, only it is 100%<br />

computer-generated, with no human<br />

intervention (analysis presented by<br />

www.chess.co.uk 31

32<br />

Bourzutschky & Konoval, 7-man<br />

Endgame Databases, in EG 159-162,<br />

2006). So, computers are capable of<br />

'composing' complete studies.<br />

Some people think that it doesn't matter<br />

how a study is composed. Their motto is<br />

"a good study is a good study is a good<br />

study". Others do not realise what all the<br />

fuss is about. For instance, GM John<br />

Nunn says "I feel that database-assisted<br />

study composition and traditional studies<br />

should be judged side by side in the<br />

same tourneys" (from his book<br />

Grandmaster <strong>Chess</strong> Move By Move,<br />

2005); "My simple and logical solution: all<br />

studies, however composed, should be<br />

considered on an equal footing. End of<br />

problem". (EG 159-162, 2006)<br />

With all due respect, this view is very<br />

hard to accept. Imagine two football<br />

strikers about to shoot a free kick. One<br />

striker does it the traditional way: he<br />

retreats a few metres, sprints to the ball<br />

and directs a powerful and precise kick<br />

into the corner, leaving the goalkeeper<br />

helpless. A great goal. The other striker is<br />

an alien from Mars. He doesn't stare at<br />

the ball, nor does he touch it. He just<br />

rubs his ear and, before you know, the<br />

ball is flying at lightning speed into the<br />

net. Another great goal, but are these<br />

goals comparable? Surely they are not. I<br />

also don't believe one should compare a<br />

painting by Van Gogh with a performance<br />

by software which throws colour onto a<br />

canvas. These are totally different things,<br />

created by different entities using<br />

different methods.<br />

Years ago I witnessed the following<br />

episode:<br />

WHITE TO PLAY (ScHEmE)<br />

This was a friendly game between two<br />

amateurs. White played his queen to g7<br />

and announced "mate!". No misprint<br />

here, you got it right: 1 £b1-g7 mate!<br />

Black protested strongly that his<br />

opponent's move was illegal. The white<br />

player pondered and came back with an<br />

evergreen response: "a mate is a mate,<br />

and it comes before any other<br />

consideration!". In a nutshell, this episode<br />

demonstrates the folly of looking only at<br />

the end result while disregarding the<br />

process.<br />

Readers might suspect that the problem<br />

of authorship is more subtle and complex<br />

than described until now, and they would<br />

be right.<br />

The celebrated John Roycroft began the<br />

argument long ago and it refuses to die<br />

away. There is a constant discussion in<br />

composition circles about artists versus<br />

computer guys, of composers versus<br />

discoverers, of concepts like "integrity"<br />

and "honour". But the fact is that the<br />

majority of study composers who use<br />

software or databases do demonstrate<br />

plenty of imagination and skill. For most<br />

of them, the computer's role is only<br />

minor. Such composers get offended by<br />

the implicit assumption that they cheat or<br />

behave in an unethical manner, and they<br />

justly feel insulted. This is a major reason<br />

why the discussion among study<br />

composers about the proper use of<br />

computers is generally heated and<br />

emotional, in an unhelpful manner.<br />

The PCCC (FIDE’s Permanent<br />

Commission for <strong>Chess</strong> Compositions, the<br />

governing body of chess problemists) has<br />

directed judges to treat studies as if they<br />

were composed in a computer-less world.<br />

This decision has been described by<br />

Beasley as "absurdly unrealistic". Someone<br />

other than a well-mannered Englishman, in<br />

my view, might have used other words,<br />

probably of the unprintable variety.<br />

Computers are here to stay. Their use,<br />

without doubt, benefits composition<br />

hugely. Looking at distinguished studies<br />

from the last decade, one feels that they<br />

are deeper, more sophisticated and on a<br />

higher level than ever before.<br />

Nevertheless, there is a crisis in the<br />

studies world regarding the evaluation of<br />

computer-assisted studies. The solution<br />

is yet unclear, but that doesn't mean that<br />

the problem will resolve itself. When<br />

emotions calm down, perhaps a rational<br />

way forward will be found.<br />

Before we part - let us look at a beautiful<br />

study. Although it leaves only six pieces<br />

on the board after White's second move<br />

(which means that theoretically it can be<br />

mined from a database), it reflects the<br />

human mind, with its emphasis on<br />

subtlety and 'point'.<br />

Eduardo Iriarte, Argentina<br />

Variantim 2009<br />

WHITE TO PLAY AND WIN<br />

To achieve victory, White must win a<br />

piece and still keep his pawn. 1 ¤c3!<br />

¤d3!! (1...¤c6 2 ¥xf8 ¢d2 3 ¥g7)<br />

2 ¥xf8! (avoiding a vicious trap: 2 exd3?<br />

¤e6! 3 ¥c1 - against 3...¢d2 or 3...¤f4+<br />

- 3...¤f4+! 4 ¥xf4 stalemate!) 2...¤f4+<br />

3 ¢f3 ¤e6 (now the bishop is<br />

embarrassed: 4 ¥e7/d6/h6 ¤d4+ 5 ¢e3<br />

¤f5+, or 4 ¥b4 ¤d4+ 5 ¢e3 ¤c2+. That<br />

leaves the next wonderful switch-back<br />

text move) 4 ¥a3!! ¤d4+ 5 ¢e3 ¤c2+<br />

6 ¢d3 ¤xa3 7 e4 1-0 (the black knight<br />

is dominated and the e-pawn promotes<br />

unhindered)<br />

__________________<br />

Amatzia Avni is a FIDE Master<br />

in both OTB chess and composition

40<br />

Is there anyone among us who hasn’t<br />

tried their hand at solving a chess<br />

problem? Or enjoyed working through a<br />

marvellous endgame study? I imagine<br />

we’ve all indulged in this pleasure.<br />

However, as well as puzzles which invite<br />

you to work out how a game ends,<br />

exploiting particular tactical motifs and<br />

the wonderful imagination of the<br />

composer, there are other types of<br />

problem which are perhaps less well<br />

known but every bit as ingenious as<br />

conventional ones. Among these is the<br />

problem category known as retrograde<br />

analysis.<br />

The difference between a retrograde<br />

analysis problem and a typical chess<br />

problem lies in the fact that the solver is<br />

not just looking for how the game should<br />

end. The various ‘unknowns’ to be<br />

worked out in such problems include the<br />

following:<br />

What were the previous x moves?<br />

All the moves of the game leading up to<br />

the current position.<br />

Work out the colour of the pieces.<br />

Mate in x moves.<br />

Where is piece x?<br />

One important aspect of such problems:<br />

you have to take into account that the<br />

legality of the position is a key element.<br />

Here we would have to define a legal<br />

position as: “any position which could<br />

have come about in a normal game of<br />

chess with legal moves, but without<br />

reference to how good or bad the moves<br />

were”. This means that you can’t<br />

compose a problem in which all the<br />

pawns were on their original squares but<br />

the king was somewhere in the middle of<br />

the board. However, it is possible to have<br />

positions where some of the moves could<br />

only have been played if the players had<br />

had a few drinks too many.<br />

To solve such problems, you don’t<br />

necessarily have to be a high-grade<br />

chessplayer or make a detailed analysis<br />

of the position. You have to apply logical<br />

reasoning to find how the position came<br />

about. That said, you need to know the<br />

basic rules of chess and how the pieces<br />

move. The rest is a question of<br />

deduction.<br />

Although this type of problem is not well<br />

known to the general public, there are<br />

some books which deal with them, such<br />

as Raymond Smullyan’s <strong>Chess</strong> Mysteries<br />

of Sherlock Holmes and <strong>Chess</strong> Mysteries<br />

of the Arabian Knights. We should also<br />

mention Arturo Pérez-Reverte who uses<br />

a retrograde analysis position in his novel<br />

The Flanders Panel in order to resolve<br />

the plot of his narrative.<br />

After this brief introduction, let’s have a<br />

look at some examples:<br />

WF von Holzhausen, 1901<br />

Mate in 1<br />

We are asked to find ‘mate in one’ but if<br />

we analysis the position as we would a<br />

normal problem we soon conclude that<br />

mate in one is impossible. But this is a<br />

retrograde analysis problem so it is a<br />

case of discovering the logic behind the<br />

problem.<br />

We soon notice that Black has no legal<br />

last move so it must have been White<br />

who moved last. As we saw in the<br />

introduction, the position must have<br />

arisen via legal moves. Once we’ve<br />

established that, we can see that White<br />

will have mate in one against all three of<br />

Black’s legal moves...<br />

1...¢xc7+ 2 bxa8¤#, 1...¢xa7+ 2 b8¤#<br />

or 1...¦xa7 2 ¦c8#<br />

In the second position (top of next<br />

column), there is no solution to the<br />

position as a conventional problem until<br />

one thinks about Black’s last move. It can<br />

only have been g7-g5. Once that is<br />

established, there is a solution:<br />

F Amelung, 1897<br />

Mate in 2<br />

1 hxg6 ¢h5 2 ¦xh7 mate<br />

Gianni Donati, 2000<br />

Position after White’s 4th move - how<br />

was this position reached?<br />

In this problem, which provides a simple<br />

initiation into this type of puzzle, we have<br />

to find the sequence of moves that led to<br />

the position shown.<br />

At first sight we observe that Black has<br />

only moved his knight and reached b3 in<br />

three moves. White has only moved dpawn<br />

and bishop. We soon arrive at the<br />

conclusion that there are two ways to get<br />

to the position shown:<br />

1 d4 ¤a6 2 ¥d2 ¤c5 3 ¥a5 ¤b3 4 ¥b6<br />

1 d3 ¤c6 2 ¥e3 ¤a5 3 ¥b6 ¤b3 4 d4

Gideon Husserl, 1986<br />

Determine the colour of the pieces<br />

Gideon Husserl, 1966<br />

1. Determine the colour of the pieces<br />

and work out what the last move was.<br />

TR Dawson, 1914<br />

2. Mate in 2<br />

Richard Mueller, 1985<br />

3. Position after White’s 7th move. Find<br />

the moves leading to this position.<br />

The first thing that can be inferred from<br />

this position is that one of the kings is in<br />

double check from the queen and rook,<br />

otherwise the position could not be legal.<br />

The next deduction is that this could not<br />

have come about by a move of the<br />

pieces, but only via the promotion of a<br />

pawn with a capture on h8. In that way<br />

we can work out that the queen, rook and<br />

king on h6 are white, and the king on g8<br />

black.<br />

Below are a few retrograde analysis<br />

puzzles for readers to test their<br />

powers of deductive reasoning.<br />

Bengt Giobel, 1946<br />

4. Place the white queen on a square to<br />

give a mate in 1<br />

Dr. Niels Hoeg, 1924<br />

5. What were the last two moves?<br />

N Petrovic, 1954<br />

6. What were the last six moves?<br />

Michael Grushko, 2005<br />

7. Position after Black’s 7th move. Find<br />

the moves leading to this position.<br />

Itamar Faybish, 2005<br />

8. Position after White’s 10th move. Find<br />

the moves leading to this position.<br />

Frolkin and Liubashevski, 1988<br />

9. Position after Black’s 20th move.<br />

Assign the correct colour to pieces and<br />

find the moves leading to the position.<br />

www.chess.co.uk 41

42<br />

SOLUTIONS TO THE RETROGRADE<br />

ANALYSIS PROBLEMS (previous page)<br />

1. Husserl, 1966<br />

The queen on c6 and rook on d8 are<br />

located such that they ‘attack’ both kings.<br />

This is only possible if the rook is a pawn<br />

which has promoted via the move c7xd8¦.<br />

So the king on c8 is black and the one on<br />

d6 is white. For the same reason, the rook<br />

on d8 is white, as is the queen. Since the<br />

d6 king is white, neither the knight on e8<br />

nor the rook on f6 can be black or the<br />

position would be illegal. The pawn on b7<br />

has to be black for the reason inferred<br />

previously. As regards the bishop on a8,<br />

since the pawn on b7 is black, it can only<br />

be white via the promotion of a pawn. For<br />

the same reason, the pawn on a7 must be<br />

white. As regards the last move played, we<br />

already know that the pawn that had<br />

resided on c7 has captured and been<br />

promoted on d8.<br />

But can go further and work out what piece<br />

it must have taken. It couldn’t have been a<br />

queen or a rook as there is no way of<br />

explaining how it could have delivered<br />

check to the king on the previous move. If it<br />

had been a bishop, Black wouldn’t have<br />

had a legal move on the previous move.<br />

Therefore we arrive at the conclusion that<br />

the piece on d8 had been a knight, and so<br />

the last move was actually 1 cxd8¦+<br />

capturing a knight.<br />

2. Dawson, 1914<br />

The black king cannot have made any<br />

move on the previous turn. The only<br />

possibility is that Black played d7-d5 or f7f5.<br />

In both cases capturing en passant<br />

would produce mate in two. But analysing<br />

further, it is possible to reach the conclusion<br />

that the d-pawn must have moved at some<br />

point in order to let the light-squared bishop<br />

out. Although the first impression might be<br />

that the bishop need not have moved (it<br />

could have fallen victim to a knight), this<br />

supposition is flawed. If you study the<br />

position a little more, the pawn structure is<br />

a little peculiar. The pawns on e3, f4 and g5<br />

came from f2, g3 and h4 respectively, each<br />

capturing a black piece. The pawns on e6<br />

and e7 came from b3 and a3. The e6 pawn<br />

has captured three pieces, and the e7<br />

pawn, four. The total number of pieces<br />

captured by the pawns comes to ten. Six<br />

black pieces remain on the board, which<br />

tells us that all the other pieces were<br />

captured by pawns. So we know that the<br />

bishop must have emerged from its initial<br />

square in order to be captured by a pawn.<br />

So, finally, we can conclude that Black’s<br />

last move was f7-f5, giving us the correct<br />

move 1 gxf6 and mate next move.<br />

3. Mueller, 1985<br />

They say that ‘appearances are deceptive’<br />

and that is definitely true here. The big<br />

surprise about this problem is that the<br />

queen on d1 is not the one that was there<br />

at the start of the game - it’s a promoted<br />

pawn! The reader can try to find another<br />

solution but I don’t think it can be found. 1<br />

a4 d6 2 a5 ¥g4 3 a6 ¥xe2 4 axb7 ¥xd1 5<br />

bxa8£ ¥g4 6 £f3 ¥c8 7 £d1<br />

4. Giobel, 1946<br />

The first thing that stands out about this<br />

position is that the white pawns haven’t<br />

moved. So the queen cannot have left the<br />

first rank and has only three legal squares:<br />

a1, b1 and c1. Having worked this out, we<br />

only have to find which one allows us to<br />

strike a blow. The queen sits on a1 and<br />

gives mate with 1 b3.<br />

5. Hoeg, 1924<br />

Black cannot have made the last move and<br />

White can only have moved his bishop. This<br />

tells us that the bishop was on a2. With the<br />

bishop on that square, Black still didn’t have<br />

a legal move with the pieces available to<br />

him. So we know that the bishop on a2 must<br />

have captured something on b1. The only<br />

piece which could have been on b1 and had<br />

a legal move on the previous turn is a knight,<br />

which could have moved from c3 to b1. It<br />

couldn’t have been a rook on b2 or the<br />

previous moves couldn’t have led to this<br />

position. So the solution is 1...¤c3-b1 2<br />

¥a2x¤b1<br />

6. Petrovic, 1954<br />

The position below shows the solution. The<br />

first thing that had to be worked out is how<br />

the bishop on a1 can be giving check. The<br />

pawn cannot have advanced because it<br />

would have been giving check on e5. The<br />

only possibility is that the pawn has<br />

captured en passant. So, giving the moves<br />

in reverse, we have 1 d5xe6 e7-e5 2 d5-d4.<br />

In this new position, the king is surrounded<br />

by squares which it cannot have come from<br />

as they are under double, or even triple<br />

attack, so the only possibility is another en<br />

passant capture. The complete solution is<br />

1...f5 2 exf6+ ¢xf6 3 d5+ e5 4 dxe6+ from<br />

this initial position...<br />

7. Grushko, 2005<br />

1 c4 ¤f6 2 £b3 ¤d5 3 £b6 axb6 4 h4<br />

¦a3 5 ¦h3 ¦xh3 6 cxd5 ¦c3 7 d6 ¦xc1#<br />

8. Faybish, 2005<br />

1 ¤f3 e6 2 ¤e5 £g5 3 ¤xd7 f6 4 ¤xb8<br />

¥d7 5 ¤c6 ¦d8 6 ¤e5 ¢e7 7 ¤f7 ¥e8<br />

8 ¤xh8 ¦d5 9 ¤g6+ ¢d6 10 ¤e5<br />

9. Frolkin and Liubashevski, 1988<br />

1 h4 h5 2 ¦h3 ¦h6 3 ¦b3 ¦a6 4 g3 g6 5<br />

¥h3 ¥h6 6 ¥e6 ¥e3 7 dxe3 dxe6 8 ¥d2<br />

¢d7 9 ¥b4+ ¢c6 10 ¤c3 £e8 11 £d8<br />

¤d7 12 0–0–0 ¤df6 13 ¢b1 £d7 14 ¢a1<br />

¤e8 15 ¦b1 £d1 16 ¤d5 ¢b5 17 ¥d6+<br />

¢a4 18 ¦b6 ¥d7 19 ¤b4 ¥b5 20 b3+<br />

Solutions to<br />

Problem Album<br />

RCO Matthews Probleemblad 1983<br />

1.¦f7 (threats 2 Rg8 and 3 Rg5++)<br />

1...¦xd3<br />

or 1...¥f8 2.£xf4+ ¦xf4 (2...£xf4 3.¥xe6#) 3.¦xf6#<br />

or 1...£d8 2.¦xf6+ ¥xf6 (2...¢xf6 3.£xf4#) 3.¥xe6#<br />

2.¥xe6+ £xe6 3.£xf4#<br />

or 2...¢xe6 3.¦xf6#<br />

RCO Matthews & B Burger Diagrammes 1993<br />

1.¤f5 (threat 2 Ng3++)<br />

1...d1£<br />

or 1...d1¤ 2.¤e4 and 3 Nfg3++<br />

or 1...¦ any 2.¤g3+ ¢e1 3.¦e4#<br />

2.£xb4 and 3 Ng3++<br />

White's responses to the promotions have traded<br />

places with one another ("reciprocal change").<br />

RCO Matthews L'Italia Scacchistica 1953<br />

1.£xf6 (threat 2 Qa6++)<br />

1...¤d3 2.¤e3#<br />

or 1...¦c5 2.¤b6#<br />

or 1...¦xb7 2.£c6#<br />

or 1...¦xe7 2.£c6#<br />

or 1...¦c6 2.£xc6#<br />

or 1...¤c3 2.£d4#<br />

or 1...¤d4 2.£xd4#<br />

The white queen's change of place at the<br />

start nullifies the diagram's promises of<br />

1...Nc3 2 Ne3++/1...Nd4 2 Nb6++, though<br />

these two mates will appear in other<br />

contexts ("changed defences" or mate<br />

transference"). Now it is other black pieces<br />

which move to occupy squares wanted by<br />

their king (first two variations).

CHESS is 75 years old!<br />

We published our first edition in 1935.<br />

To celebrate, we are dipping into our<br />

archives to present readers with<br />

material from our early days. One of<br />

our regular collaborators in the 1930s<br />

was the famous columnist and<br />

blindfold player George Koltanowski<br />

(1903-2000). This slightly abridged<br />

article is from CHESS, October 1936,<br />

in which he tells the story of how he<br />

first started to play blindfold chess.<br />

How it started? Well, that's a funny story.<br />

Years ago - I was in my teens at the time,<br />

sweet seventeen! - I went with Sapira<br />

(Emmanuel Sapira 1900-43, a Belgian<br />

chess master - ed) to Ghent to watch the<br />

Serbian player, Tschabritch (unidentified -<br />

have readers any idea who this was? -<br />

ed), play two games blindfold. We thought<br />

it to be impossible.<br />

Thinking ourselves very wise, we asked if<br />

we could take the two boards against<br />

Tschabritch. We did not trust the players<br />

there and thought that the whole thing<br />

might be a put-up job, with the games<br />

rehearsed beforehand. To our surprise, we<br />

were accepted, and to our even greater<br />

surprise we found ourselves in difficulties<br />

almost from the beginning. I can't recall<br />

the result with certainty, but I think both<br />

games ended in draws and I know we had<br />

a very hard job not to lose. We were<br />

convinced and we were stricken!<br />

Later I asked the Serbian how he learned to<br />

play blindfold. "Quite easy," he answered.<br />

"I merely drew a chess board on the ceiling<br />

of my bedroom. Then every morning when<br />

I awoke I played over an opening on the<br />

board in my imagination and soon I found<br />

I could visualise the board with my eyes<br />

shut and go through whole games."<br />

This impressed me enormously. When we<br />

got back to Antwerp, we talked about this<br />

wonderful thing for days on end; in fact,<br />

whenever we were anywhere near<br />

anybody who understood chess. Then<br />

someone challenged me to play them one<br />

game blindfold. I accepted... but after ten<br />

moves I had to confess that I had lost<br />

track of the position.<br />

This disgusted me. I was young and<br />

foolish, and made up my mind I would<br />

not let blindfold play get the better of me.<br />

I started to draw a big black-and-white<br />

chess board on the ceiling of my<br />

bedroom, but my father came and caught<br />

me in the act and succeeded in impressing<br />

on me pretty forcibly that if I could not<br />

work out some system not based on<br />

ruining a ceiling I had better drop the<br />

whole thing altogether.<br />

Whilst I was considering whether to tie up<br />

a board on to the ceiling instead of drawing<br />

it, another possible way of tackling the<br />

problem occurred to me. I was just<br />

beginning to realise how important, as an<br />

aid to visualisation, the colours of the<br />

squares were. Once you know, almost by<br />

second nature, which squares are white and<br />

which black, half the battle is over. You<br />

can then never be just one square out in<br />

your reckoning, for it would be the wrong<br />

colour; and you are seldom two squares<br />

out, so you must be just right. Get me?<br />

Also, you work down diagonals, etc.<br />

I cut a paper chess board into four parts<br />

like this:<br />

Rather strangely, I found it easier to<br />

remember the colours then, and I find it<br />

easier to remember moves and positions<br />

now, on four little boards like this than on<br />

one big one. Try it yourself. Perhaps<br />

psychologists can explain. Anyway, I<br />

spent about half-a-day learning the board<br />

by heart and after that you had only to<br />

give me the name of a square, say, KB2,<br />

or Q6, or Q7, for me to tell you its colour<br />

without a second's hesitation.<br />

At once, after this preparation, I found I<br />

could conduct a single blindfold game with<br />

ease. One day I offered to play three boards<br />

simultaneously blindfold at the club. The<br />

offer was accepted and, to my delight, I got<br />

through the ordeal successfully. After that it<br />

was only a matter of practice, though I<br />

must add that I did not start playing on<br />

more than six boards until after I had won<br />

the Belgian championship.<br />

Naturally, once I found myself on safe<br />

round I accepted every invitation for<br />

blindfold displays on six or eight boards<br />

that came. I soon had given displays in<br />

Holland, Germany and England as well as<br />

Belgium. I was once on my way to give a<br />

display when I arrived at a little junction<br />

town, only to find that the train I should<br />

have caught had departed and that I was<br />

stranded there until the next morning. This<br />

would not have mattered if I had had any<br />

money on me, but I had only a few cents;<br />

I had not bothered particularly about<br />

having any money with me as I knew<br />

there would be adequate hospitality at the<br />

place where I was to give the display.<br />

I walked round the little town about five<br />

times and was just beginning to resign<br />

myself to a hungry and sleepless night,<br />

when I happened to see, through the<br />

window of a café, two men playing chess<br />

and a third watching. In I went, watched<br />

them for a while and when they had<br />

finished I said I would play all three of<br />

them blindfold. They could not quite<br />

understand what I meant at first, but after<br />

a bit of explanation they began to<br />

understand and became very keen to see<br />

me achieve the "impossible." To cut a<br />

long story short, I won all three games<br />

quickly and after that I could have had<br />

anything I wanted. A splendid supper and<br />

a fine bed. That was the only time I have<br />

really “sung for my supper"!<br />

Simultaneous blindfold displays have their<br />

awkward side, and two classes of people<br />

are the bane of my life; good players who<br />

won’t take a board against me, but go<br />

round advising the others, and bad players<br />

who never resign. I would far rather a<br />

good player sat down and played against<br />

me. You see, as soon as I realise a player<br />

www.chess.co.uk 43

44<br />

at a certain board is weak, I go all out for<br />

him, aiming at a quick mate or big<br />

material win. Forcing the game is always<br />

dangerous, and it is just where I have the<br />

weak player wavering between ten losing<br />

lines that the good player seems to take a<br />

fiendish delight in coming up and pointing<br />

out to him the single subtle win.<br />

The worst result I ever had was at Ghent one<br />

night. I was playing eight boards and a<br />

messenger was constantly taking the moves<br />

into the next room where eight positions<br />

were set up identical with those in my room,<br />

with crack players analysing for all they<br />

were worth. Then he would rush back with<br />

moves to be made by my opponents and<br />

take a fresh batch of my moves back with<br />

him, I scored about fifty per cent, and, whilst<br />

bandages were being unwrapped from eyes,<br />

I was beginning to wonder whether I had<br />

better give up blindfold play in future and to<br />

fear that I had permanently overstrained my<br />

brain. Perspiration was streaming down my<br />

face and I expected everybody to start<br />

hissing at any moment. Instead, there were<br />

loud cheers... and it was then that the<br />

horrible practical joke was explained to me,<br />

and I learned that I been playing against the<br />

whole team of contestants in the current<br />

Belgian Championship!<br />

Blindfold play is a great attraction, but<br />

should not be regarded as anything more.<br />

It usually gets onlookers and contestants<br />

excited and is good value for money. But<br />

if a player continues to play on, a queen<br />

or two rooks down in the hope that the<br />

blindfold player will tire and make a slip,<br />

then all enjoyment goes, for the spectators<br />

as much as for the blindfold player. In one<br />

display, at Manzanares (Spain), I started at<br />

11 o’clock at night on eight boards. At 1<br />

a.m. I was a queen up on four boards, yet<br />

nobody was thinking of resigning. At two<br />

o’clock I had won three games and drawn<br />

one, but these four wood-shifters were<br />

plodding on and still they were each a<br />

queen or more to the bad. I had to give a<br />

display in another town the next day, and<br />

as my train left at six a.m.: “You are good<br />

Spaniards!” I addresses them: "You may<br />

be caballeros or picadors, you may have<br />

knives in your belts: but just here and now<br />

I am going to be rude to you. I am going<br />

to sleep.” And I did.<br />

I awoke at 5-15 a.m. and. they were there.<br />

So I resumed, mating one on the second<br />

move and the others a little later. Were<br />

they wild? Was I wild? But I did not know<br />

then what a Spanish revolution was like -<br />

that is a story I shall have to tell you later.<br />

In 1923 I played sixteen games blindfold,<br />

with a good result, thus establishing a<br />

Belgian record. Then I had to become a<br />

soldier. (I can imagine you smiling at that.)<br />

There is, of course, conscription in<br />

Belgium. It was the hospital service into<br />

which I was drafted and the job in which I<br />

specialised was peeling potatoes, definitely<br />

not an inspiration to the blindfold chess<br />

player. For the last three months of my<br />

year's service I was transferred from the<br />

occupied Rhine to Namur, and it was<br />

goodbye to potato-peeling then, for by a<br />

stroke of good fortune my captain was the<br />

president of the local chess club.<br />

The day my army service ended, I set off<br />

for my home town, Antwerp. Thoroughly<br />

tired, resolved to do just nothing for a<br />

fortnight. Luxuriously relax. Laze and<br />

smoke and read.<br />

As soon as I stepped out of the station, I<br />

saw glaring at me a great placard on the<br />

wall of the street:<br />

G. KOLTANOWSKI,<br />

<strong>Chess</strong> Champion of Belgium,<br />

will play next Sunday afternoon, at 3-30,<br />

twenty games simultaneously blindfold.<br />

It almost knocked me over, and I felt too<br />

weak to read any more. Not a scrap of<br />

warning, with me totally out of training.<br />

And on a Sunday of all days, so that a<br />

wonderful "date" had to be sacrificed!<br />

There was nothing to do but face up to it,<br />

so I went into training at once, sleeping<br />

till 11 o'clock each morning, drinking milk<br />

and going off early to bed.<br />

On Wednesday morning, however, my<br />

sergeant comes to me and asks me to do<br />

him a little favour. "Certainly!" I<br />

answered, little dreaming what it was<br />

going to lead me into. "Well, you see, it's<br />

like this!" he explained, "An old aunt of<br />

mine keeps a delicatessen shop in Namur<br />

and they have a visit from their local<br />

preacher every Wednesday evening. This<br />

man thinks he can beat anybody at chess<br />

and is becoming insufferable, and you<br />

would do us all a great favour if you<br />

would come down and beat him a few<br />

times." "By all means!" I said, and went.<br />

We arrived before the vicar and we<br />

arranged that I was to be a distant relative<br />

of the Sergeant from Courtrai. When the<br />

vicar arrived we said nothing about chess<br />

for awhile, so as not to make him<br />

suspicious. Suddenly: "Have you seen the<br />

placards?" he asked: "Somebody is going<br />

to play twenty games simultaneously<br />

blindfold! Just as if it were possible! All a<br />

put-up job in my opinion! I'd like to play<br />

that Johnny - I bet I would beat him."<br />

"Are you talking about chess?" I asked,<br />

simply. "Yes, do you play?" "I have a<br />

game or two now and then in Courtrai." "<br />

"Very well," said the Vicar, delightedly,<br />

“pull out the board and men and I'll have a<br />

game with you!"<br />

It did not take me long to find out that the<br />

Vicar was a very bad player indeed. I did<br />

not rush things, just won quietly in the<br />

first game. "Bah!" he exclaimed, "It was<br />

simply that I did not concentrate. Let us<br />

have a stake on it. I can only play with<br />

some incentive. Everybody then suggested<br />

as they always do, that the loser should<br />

pay for drinks all round. The vicar<br />

consented, and I, though I remembered<br />

rather nervously that I was in training,<br />

dare not do anything but agree. The<br />

glasses were brought out and filled and I<br />

started: 1 e4 e5 2 ¥c4 ¤c6 3 £h5 ¤f6<br />

4 £xf7 mate. "Your health!" I said.<br />

"Eh?" he said "that was a trick, here, we<br />

must have another. Drink up your glass,<br />

man!" he continued testily, replacing the<br />

pieces in their original positions.<br />

He was a man of spirit, I will say that for<br />

him. We played on and on into the night<br />

and no sooner had he lost one game than he<br />

insisted on starting another, paying up the<br />

"stake" and making me drink up. After the<br />

fifth bottle I started to feel bad. I arose<br />

rather clumsily and before saying goodnight<br />

to all I handed my card to the vicar. "Oh !"<br />

he explained, "for heaven's sake don't tell<br />

anybody about this, it will make me the<br />

laughing stock of Namur." "Not at all," I<br />

said, "you have played like a gentleman!"<br />

and I tried to persuade him to let me divide<br />

the "stakes" after all, but he would not.<br />

Next morning, I was on the sick list. I had<br />

a "hang-over" till Saturday, for I hardly<br />

ever drink as a rule, but on Sunday<br />

morning I felt my will-power (which is<br />

really all that carries me through these<br />

blindfold exhibitions) surging back again<br />

and in the morning I won the blindfold<br />

championship of Belgium, and in the<br />

afternoon I played twenty games blindfold<br />

against players from all over Belgium,<br />

with a good result. The vicar was there<br />

and ever since he has been one of my<br />

staunchest supporters!<br />

Years afterwards I was sitting in a café<br />

which is a favourite haunt of the members<br />

of the Flemish chess club at Antwerp with<br />

my friends, Jacobs, Perquin, Van Weerdt.<br />

"Let's have a round on you," said someone<br />

to Perquin. "OK" replied Perquin,<br />

genially, "if..... " and his eyes came round<br />

to me with a nasty twinkle: "Koltanowski

here will play thirty games blindfold,<br />

beating the world's record." "Pay up,<br />

Perquin! " I said, "I'll do it."<br />

In that care-free fashion, it all started. Once<br />

I had made my promise, the Flemish <strong>Chess</strong><br />

Club began to make serious preparations,<br />

and there was nothing for it for me but to<br />

go into hard training. Besides working out<br />

a detailed and absolutely infallible method<br />

of remembering the boards, I had to see to<br />

it that I should be physically fit for such an<br />

effort, in view of the fact that such a largescale<br />

business could not possibly take less<br />

than ten hours. The physical side of my<br />

training was every bit as Important as the<br />

mental.<br />

My system was as follows: Into bed each<br />

day at 7 p.m. Up at 6 a.m. and out for a<br />

long walk. Breakfast at 8 a.m., then out for<br />

another long walk. Lunch at 12, followed<br />

by a rest. Then at 3 p.m. I would practise<br />

out three moves on each of thirty boards.<br />

The thirty opening moves I decided to<br />

arrange in the following manner: Board 1,<br />

e4; Board 2, d4; Board 3, e4; Board 4, d4;<br />

Board 5, f4. Then the variations,<br />

according to my opponents' replies: to the<br />

first French defence I should reply on the<br />

third move exd5; to the second, Nc3; to<br />

the third, e5, and so on. I had similar<br />

replies ready for the Sicilian defence, the<br />

Caro-Kann and the Ruy Lopez.<br />

The great difficulty in big displays like<br />

this is to get the games all following<br />

different trends early on; they then<br />

become easier to remember. After four or<br />

five moves there may be four games, say,<br />

those at boards 2, 7, 22 and 27, at which<br />