ENGINEERING - Board of Engineers Malaysia

ENGINEERING - Board of Engineers Malaysia

ENGINEERING - Board of Engineers Malaysia

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

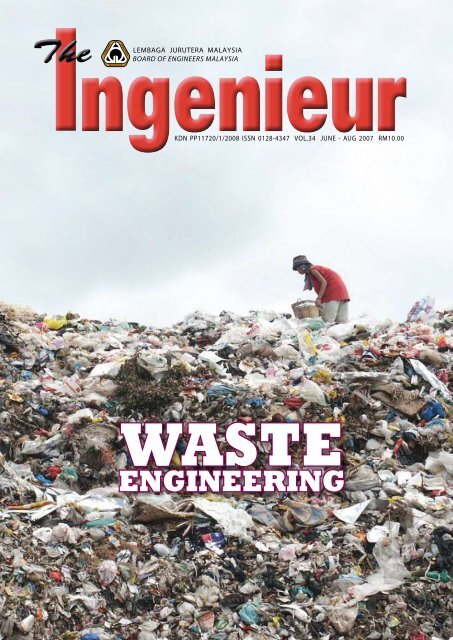

LEMBAGA JURUTERA MALAYSIA<br />

BOARD OF ENGINEERS MALAYSIA<br />

KDN PP11720/1/2008 ISSN 0128-4347 VOL.34 JUNE - AUG 2007 RM10.00<br />

WASTE<br />

<strong>ENGINEERING</strong>

2 THE INGENIEUR<br />

Volume 34 June - August 2007<br />

18<br />

39<br />

48<br />

56<br />

c o n t e n t s<br />

4 President’s Message<br />

Editor’s Note<br />

5 Announcement<br />

Heartiest Congratulations<br />

Publication Calendar<br />

Events Calendar<br />

APEC And EMF International Registers<br />

Cover Feature<br />

6 Scheduled Waste Management: Issues And Challenges<br />

12 Life Cycle Inventorization Between Open Dumps And<br />

Sanitary Landfills<br />

18 Modelling Energy Recovery From Gasification Of<br />

Solid Waste<br />

22 Special Notice<br />

Registration Of <strong>Engineers</strong> (Amendment) Act 2007<br />

27 Guidelines<br />

Certificate Of Completion And Compliance (CCC)<br />

29 Engineering And Law<br />

Demystifying Direct Loss And Expense Claims:<br />

The Continuing Saga<br />

Feature<br />

38 Wet Market Waste To Value Added Products<br />

42 Sustainable Solid Waste Management: Incorporating<br />

Life Cycle Assessment As A Decision Support Tool<br />

46 Waste Management In The Plastics Industry<br />

52 Sanitation – The New Paradigm<br />

56 Engineering Nostalgia<br />

The Lumberjack Team Of The 60s

4 THE INGENIEUR<br />

KDN PP11720/1/2008<br />

ISSN 0128-4347<br />

Vol. 34 June - August 2007<br />

MEMBERS OF THE BOARD OF ENGINEERS MALAYSIA<br />

(BEM) 2006/2007<br />

President<br />

YBhg. Dato’ Ir. Dr. Judin Abdul Karim<br />

Registrar<br />

Ir. Dr. Mohd Johari Md. Arif<br />

Members<br />

YBhg. Tan Sri Dato’ Ir. Md Radzi Mansor<br />

YBhg. Datuk Ir. Hj. Keizrul Abdullah<br />

YBhg. Mej. Jen. Dato’ Ir. Ismail Samion<br />

YBhg. Dato’ Ir. Shanthakumar Sivasubramaniam<br />

YBhg. Datu Ir. Hubert Thian Chong Hui<br />

YBhg. Dato’ Ir. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Chuah Hean Teik<br />

Ar. Dr. Amer Hamzah Mohd Yunus<br />

Ir. Henry E Chelvanayagam<br />

Ir. Dr. Shamsuddin Ab Latif<br />

Ir. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Dr. Ruslan Hassan<br />

Ir. Mohd. Rousdin Hassan<br />

Ir. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Dr. Hassan Basri<br />

Tn Hj. Basar bin Juraimi<br />

Ir. Ishak Abdul Rahman<br />

Ir. Anjin Hj. Ajik<br />

Ir. P E Chong<br />

EDITORIAL BOARD<br />

Advisor<br />

YBhg. Dato’ Ir. Dr. Judin Abdul Karim<br />

Chairman<br />

YBhg Datuk Ir. Shanthakumar Sivasubramaniam<br />

Editor<br />

Ir. Fong Tian Yong<br />

Members<br />

Ir. Prem Kumar<br />

Ir. Mustaza Salim<br />

Ir. Chan Boon Teik<br />

Ir. Ishak Abdul Rahman<br />

Ir. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Dr. K. S. Kannan<br />

Ir. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Dr. Ruslan Hassan<br />

Ir. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Madya Dr. Eric K H Goh<br />

Ir. Nitchiananthan Balasubramaniam<br />

Executive Director<br />

Ir. Ashari Mohd Yakub<br />

Publication Officer<br />

Pn. Nik Kamaliah Nik Abdul Rahman<br />

Assistant Publication Officer<br />

Pn. Che Asiah Mohamad Ali<br />

Design and Production<br />

Inforeach Communications Sdn Bhd<br />

Printer<br />

Art Printing Works Sdn Bhd<br />

29 Jalan Riong, 59100 Kuala Lumpur<br />

The Ingenieur is published by the <strong>Board</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Engineers</strong><br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong> (Lembaga Jurutera <strong>Malaysia</strong>) and is distributed<br />

free <strong>of</strong> charge to registered Pr<strong>of</strong>essional <strong>Engineers</strong>.<br />

The statements and opinions expressed in this<br />

publication are those <strong>of</strong> the writers.<br />

BEM invites all registered engineers to contribute articles<br />

or send their views and comments to<br />

the following address:<br />

Publication Committee<br />

Lembaga Jurutera <strong>Malaysia</strong>,<br />

Tingkat 17, Ibu Pejabat JKR,<br />

Jalan Sultan Salahuddin,<br />

50580 Kuala Lumpur.<br />

Tel: 03-2698 0590 Fax: 03-2692 5017<br />

E-mail: bem1@streamyx.com; publication@bem.org.my<br />

Website: http://www.bem.org.my<br />

Advertising/Subscriptions<br />

Subscription Form is on page 51<br />

Advertisement Form is on page 55<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong>’s vision <strong>of</strong> becoming a fully<br />

developed nation by 2020 and its associated rapid<br />

economic growth have necessitated the practice<br />

<strong>of</strong> proper waste management in accordance to<br />

acceptable international standards. Although<br />

there is extensive work to be carried out in the<br />

area <strong>of</strong> toxic and scheduled waste management<br />

in the country, there is still room for improvement in overall<br />

waste management, particularly in connection with solid waste<br />

management due to the large quantity produced daily.<br />

The Government is planning a new strategy towards solid<br />

waste management which includes the creation <strong>of</strong> a new bill<br />

and the formation <strong>of</strong> a regulatory body. In this regard, we should<br />

see more strategies and action plans being formulated. This<br />

should auger well for engineers as there will be opportunities<br />

to introduce state-<strong>of</strong>-the-art technologies and implement projects<br />

to treat the increasing solid waste generated, particularly from<br />

the domestic sector.<br />

While the opportunities are vast and varied, it is up to<br />

practising engineers to venture into this area, and in the process,<br />

make <strong>Malaysia</strong> a technology exporter.<br />

Dato’ Ir. Dr. Judin Abdul Karim<br />

President<br />

BOARD OF ENGINEERS MALAYSIA<br />

As the subject <strong>of</strong> waste management is causing<br />

concern from all stakeholders (particularly the<br />

industry players), we dedicate this edition to waste<br />

once again. The last edition on waste management<br />

has attracted significant interest from readers with all<br />

the copies snapped up within days <strong>of</strong> publication.<br />

In this edition, the article on ‘Modelling Energy Recovery<br />

from Gasification <strong>of</strong> Solid Waste’ provides a comparison between<br />

various thermal treatment <strong>of</strong> waste. The article on ‘Scheduled<br />

Waste Management’ categorizes the 107 scheduled wastes and<br />

examines the issues and challenges involved. On a global<br />

perspective, the World Toilet Organisation takes a new approach<br />

to sustainable sanitation and the three goals <strong>of</strong> sustainability.<br />

We hope this edition <strong>of</strong> The Ingenieur <strong>of</strong>fers readers a<br />

general perspective on policies, technology, pollution effects<br />

and recycling effort related to waste management.<br />

Ir. Fong Tian Yong<br />

Editor<br />

President’s Message<br />

Editor’s Note

THE INGENIEUR ANNOUNCEMENT<br />

To<br />

YBhg Dato’ Ir. Dr Judin Abdul Karim<br />

for his appointment as<br />

Director General,<br />

Public Works Department <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

from <strong>Board</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Engineers</strong> <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

The following list is the<br />

Publication Calendar for the<br />

year 2007 - 2008. While we<br />

normally seek contributions<br />

from experts for each special<br />

theme, we are also pleased<br />

to accept articles relevant to<br />

themes listed.<br />

Please contact the Editor<br />

or the Publication Officer in<br />

advance if you would like to<br />

make such contributions or to<br />

discuss details and deadlines.<br />

September 2007: CONTRACTS<br />

December 2007: PROJECT<br />

FINANCING<br />

March 2008: POWER<br />

Registration To The APEC And<br />

EMF International Registers<br />

• Entrance fee for new applicants waived<br />

• One subscription for two Registers.<br />

New members who sign up for year 2007<br />

pay only RM 300.<br />

Annual subscription is valid until 2009.<br />

SIGN UP NOW<br />

SPECIAL PACKAGE<br />

For further enquiries, kindly contact:-<br />

Valid For<br />

2007 Only<br />

APEC/ EMF International Engineer Registers Secretariat,<br />

Bangunan Ingenieur, Lots 60 & 62<br />

Jalan 52/4, P.O. Box 223, Jalan Sultan,<br />

46720 Petaling Jaya,<br />

Selangor Darul Ehsan<br />

Event Calendar<br />

Saudi – <strong>Malaysia</strong> Forum on Strategic Engineering Cooperation<br />

July 9 – 10, 2007<br />

Prince Hotel & Residence, Kuala Lumpur<br />

BEM Approved CPD : 16 hours/points<br />

Organiser : <strong>Board</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Engineers</strong> <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

Tel : 03-26967098 / 03-26912090 / 03-26982413<br />

Fax : 03-26925017<br />

Email : bem1@jkr.gov.my; training_exam@bem.org.my;<br />

URL : www.bem.org.my<br />

MBAM Conference 2007- Going Global: Challenges<br />

and Opportunities<br />

July 31, 2007<br />

Sime Darby Convention Hall, Kuala Lumpur<br />

BEM Approved CPD : 8 hours/points<br />

Organiser: Master Builders Association <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

Tel : 03-79848636 Fax : 03-79826811<br />

Email : mbam05@mbam.org.my<br />

URL : www.mbam.org.my<br />

Income Tax Reform Towards Enhancing The Nation’s<br />

Economic Competitiveness<br />

July 10, 2007<br />

The Legend Hotel, Kuala Lumpur<br />

BEM Approved CPD : 2 hours/points<br />

Organiser : The <strong>Malaysia</strong>n Institute <strong>of</strong> Certified Public<br />

Accountants<br />

Tel : 03-26989622<br />

Email : micpa@micpa.com.my<br />

URL : www.micpa.com.my<br />

Facilities Management Conference 2007<br />

July 23 - 24, 2007<br />

J W Marriott Hotel, Kuala Lumpur<br />

BEM Approved CPD : 12 hours /points<br />

Organiser : Asia Business Forum (Singapore) Pte Ltd<br />

Tel : 03-2070 3299 Fax : 02-26925017<br />

Email : puvanes@abf-asia.com<br />

URL : http://www.abf-asia.com/project/9440MC_EM.pdf<br />

Tea Talk on Financing Solutions for Service Exports<br />

July 9, 2007<br />

Level 6, Block B, Kompleks Kerja Raya <strong>Malaysia</strong>, Kuala Lumpur<br />

Organiser : Pr<strong>of</strong>essional Services Development Corporation<br />

Sdn Bhd<br />

Tel : 03-26988415 Fax : 03-26988416<br />

Email : aziz@mypsdc.com<br />

World Housing Congress (WHC2007) on Affordable<br />

Quality Housing: Challenges and Isues in the Provision <strong>of</strong><br />

Shelter for All<br />

July 1 - 5, 2007<br />

Primula Beach Resort, Terengganu<br />

BEM Approved CPD : 28 hours /points<br />

Organiser : Housing Research Centre, UPM; Federation <strong>of</strong><br />

Engineering Institutions <strong>of</strong> Islamic Countries, Saudi Council<br />

<strong>Engineers</strong>, Terengganu State Government & CIDB<br />

Tel : 03-89467849<br />

URL : http://eng.upm.edu.my/~whc2007<br />

View Latest Tender Information On-line<br />

July 3, 9, 12, 17, 24 & 31 and August 7 & 9, 2007<br />

Organiser: CIDB Holdings Sdn Bhd<br />

Tel : 03-40428880<br />

URL : www.cidb.gov.my/tender<br />

5

6 COVER FEATURE<br />

THE INGENIEUR<br />

Scheduled Waste Management:<br />

Issues And Challenges<br />

By Ir. Lee Heng Keng, Deputy Director General (Operation) Department <strong>of</strong> Environment <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

Control <strong>of</strong> toxic and hazardous<br />

wastes in <strong>Malaysia</strong> dates<br />

b a ck t o t h e d ay t h e<br />

Environmental Quality (Sewage<br />

and Industrial Effluents) Regulations<br />

1979 came into force on January<br />

1, 1979. Regulations 9 and 10<br />

provide for the restrictions on the<br />

discharge <strong>of</strong> effluents and disposal<br />

<strong>of</strong> sludge on any soil or surface <strong>of</strong><br />

any land, unless with the written<br />

permission <strong>of</strong> the Director General<br />

<strong>of</strong> Environment. The purpose <strong>of</strong> this<br />

provision is largely to check, in<br />

the interim period, indiscriminate<br />

disposal <strong>of</strong> industrial waste on<br />

land.<br />

Generation <strong>of</strong> hazardous wastes<br />

must be controlled to protect public<br />

health and the environment. We<br />

have learnt from previous experience<br />

that environmental problems <strong>of</strong><br />

developed countries are associated<br />

with illegal and indiscriminate<br />

disposal <strong>of</strong> hazardous waste that was<br />

detrimental to the environment and<br />

required costly clean-up measures.<br />

Realising the potential danger <strong>of</strong><br />

improper management <strong>of</strong> toxic and<br />

hazardous wastes, the Government<br />

has taken initiatives since 1979 to<br />

identify the possible options and<br />

necessary measures for its proper<br />

management. These include the<br />

identification, classification and<br />

quantification <strong>of</strong> the various types<br />

<strong>of</strong> toxic and hazardous wastes being<br />

generated and also its treatment<br />

and disposal. This culminated<br />

in the formulation <strong>of</strong> three sets<br />

<strong>of</strong> regulation in 1989 for the<br />

management <strong>of</strong> toxic and hazardous<br />

wastes, termed as scheduled wastes<br />

in <strong>Malaysia</strong>, to ensure hazardous<br />

waste produced in the country<br />

is managed safely and in an<br />

environmentally sound manner. A<br />

review <strong>of</strong> the Environmental Quality<br />

(Scheduled Wastes) Regulation<br />

1989 was initiated to improve the<br />

management <strong>of</strong> scheduled wastes<br />

and resulted in the coming into<br />

force <strong>of</strong> the Environmental Quality<br />

(Scheduled Wastes) Regulation<br />

2005 on August 15, 2005.<br />

POLICIES AND LEGAL<br />

REQUIREMENTS ON<br />

THE CONTROL OF<br />

SCHEDULED WASTES<br />

Environmental Quality Act 1974<br />

The Environmental Quality Act<br />

1974 (EQA) was enacted on<br />

March 22, 1974 to prevent,<br />

abate and control pollution and<br />

enhance the environment and<br />

for related purpose. Since then,<br />

30 regulations and orders have<br />

been introduced to deal with<br />

specific pollution problems, from<br />

agro-based and manufacturing<br />

industries, air emissions from<br />

stationary and mobile sources,<br />

noise from motor vehicles and<br />

m a n a g e m e n t o f s c h e d u l e d<br />

wastes. The EQA was amended<br />

in 1985 to make it mandatory for<br />

prescribed activities to undertake<br />

Construction waste<br />

environmental impact assessment.<br />

In 1996, the Environmental Quality<br />

Act <strong>of</strong> 1974 was again amended<br />

and an explicit provision on the<br />

control <strong>of</strong> scheduled wastes was<br />

one <strong>of</strong> the inclusions made. It<br />

also addresses our international<br />

commitment more specifically the<br />

Basel Convention on the Control <strong>of</strong><br />

Transboundary Movements <strong>of</strong> Toxic<br />

and Hazardous Wastes and Their<br />

Disposal. This provision prohibits<br />

the following activities without<br />

any prior written approval <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Director General <strong>of</strong> Environment:<br />

(i) Any placement, deposit or<br />

disposal <strong>of</strong> any scheduled<br />

wa s t e s o n l a n d o r i n t o<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong>n waters except at<br />

prescribed premises;<br />

(ii) Receive or send scheduled<br />

wastes in and out <strong>of</strong> <strong>Malaysia</strong>,<br />

and<br />

(iii) Transit <strong>of</strong> scheduled wastes.<br />

T h e E Q A a l s o a l l o w s<br />

e nvironmentally h a z a r d o u s<br />

substances to be prescribed which<br />

may then be required to be reduced,<br />

recycled, recovered or regulated in<br />

the form <strong>of</strong> a substance or product.<br />

The provision further empowers<br />

the authority to specify rules on<br />

the use, design and application <strong>of</strong><br />

labels in connection with the sale<br />

<strong>of</strong> the substance or product.<br />

Environmental Quality (Scheduled<br />

Wastes) Regulations 1989<br />

The Regulations for the control<br />

<strong>of</strong> scheduled wastes were based on<br />

the ‘cradle-to-grave’ concept where<br />

generation, storage, transportation,<br />

treatment and disposal are regulated.

THE INGENIEUR COVER FEATURE<br />

A total <strong>of</strong> 107 waste categories are<br />

prescribed as scheduled wastes.<br />

The regulations focused on the<br />

following key provisions:<br />

(i) Control <strong>of</strong> the generation<br />

<strong>of</strong> waste by a notification<br />

system;<br />

(ii) Avoidance or minimization <strong>of</strong><br />

waste generation;<br />

(iii) Safe storage <strong>of</strong> wastes;<br />

(iv) Licensing <strong>of</strong> scheduled waste<br />

facilities;<br />

(v) Treatment and disposal <strong>of</strong><br />

waste at prescribed premises;<br />

and<br />

(vi) Implementation <strong>of</strong> the manifest<br />

system for tracking and<br />

controlling the movement <strong>of</strong><br />

wastes.<br />

Waste generators have to notify<br />

the Department <strong>of</strong> Environment<br />

whilst the treatment and disposal<br />

<strong>of</strong> scheduled wastes can only be<br />

carried out at a licensed facility.<br />

The movement <strong>of</strong> wastes from the<br />

point <strong>of</strong> generation to the treatment<br />

facility is tracked by the use <strong>of</strong><br />

consignment notes.<br />

Environmental Quality (Scheduled<br />

Wastes) Regulations 2005<br />

After more than 15 years <strong>of</strong><br />

enforcing the scheduled waste<br />

regulation, the Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Environment encountered various<br />

shortcomings and a comprehensive<br />

review was carried out to address<br />

these shortcomings. As a result the<br />

Environmental Quality (Scheduled<br />

Wastes) Regulations 2005 was<br />

e n a c t e d t h u s r e vo k i n g t h e<br />

Environmental Quality (Scheduled<br />

Wastes) Regulation 1989. The major<br />

change in the 2005 Regulation is<br />

that scheduled wastes are now<br />

categorized based on type <strong>of</strong> waste<br />

rather than the source or origin<br />

<strong>of</strong> the wastes. New provisions<br />

instituted included the special<br />

management <strong>of</strong> waste, limiting<br />

the amount and duration <strong>of</strong> waste<br />

storage, recovery <strong>of</strong> scheduled<br />

wastes, conduct <strong>of</strong> training for<br />

persons handling scheduled wastes<br />

and improvement in the labelling<br />

requirements.<br />

Scheduled wastes are now<br />

categorised under five groups, viz.<br />

metal and metal-bearing wastes;<br />

wastes containing principally<br />

inorganic constituents which may<br />

contain metals or organic materials;<br />

wastes containing principally<br />

organic constituents which may<br />

contain metals and inorganic<br />

materials; wastes which may<br />

contain either inorganic or organic<br />

constituents and other wastes.<br />

These wastes were considered<br />

after reviewing hazardous waste<br />

categories from other countries<br />

as well as those prescribed under<br />

the Basel Convention on the<br />

Transboundary Movements <strong>of</strong><br />

Hazardous Wastes and Their<br />

Disposal 1989.<br />

Four types <strong>of</strong> wastes in the 1989<br />

Regulations were deleted and 10<br />

new waste categories were included<br />

in the new Regulations. The<br />

deleted wastes were effluents from<br />

rubber factory; effluents from textile<br />

factory; leachate from landfills and<br />

slag from iron and steel industry<br />

whilst those added were: galvanic<br />

sludges; leaching residue from zinc<br />

processing; electrical and electronic<br />

wastes; wastes gypsum; waste <strong>of</strong><br />

organic phosphorous compound;<br />

wastes containing dioxin or furans;<br />

discarded chemicals; obsolete<br />

laboratory chemicals; wastes<br />

containing peroxides and residues<br />

Old mobile phones<br />

from treatment <strong>of</strong> scheduled wastes.<br />

Also for the first time scheduled<br />

wastes generated are not allowed<br />

to be stored for more than 180<br />

days after its generation provided<br />

that the quantity <strong>of</strong> scheduled<br />

wastes accumulated on site shall<br />

not exceed 20 tonnes. However<br />

any person may store more than<br />

20 tonnes <strong>of</strong> scheduled wastes<br />

provided that the Director General<br />

<strong>of</strong> Environment grants a written<br />

approval subject to conditions or<br />

unconditionally. If the Director<br />

General has reason to believe that<br />

the scheduled wastes stored can<br />

cause environmental or health<br />

impact he may direct the waste<br />

generator to send any scheduled<br />

waste for recovery, treatment or<br />

disposal for such a period or up to<br />

a quantity as he may direct.<br />

Under Regulation 7, a waste<br />

generator may apply in writing to<br />

have the scheduled wastes excluded<br />

from being disposed, treated<br />

or recovered at the prescribed<br />

premises. This is to give waste<br />

generator an opportunity to prove<br />

that the wastes will not cause any<br />

adverse impact on the environment<br />

or public health. Toward this<br />

end, the waste generator must<br />

submit documentary evidence<br />

that the wastes do not exhibit<br />

any hazardous characteristics in<br />

terms <strong>of</strong> corrosiveness, ignitability,<br />

reactivity, toxicity etc. and also<br />

that the wastes do not have any<br />

hazardous effects on human or other<br />

life forms. Application must be in<br />

accordance with the guidelines for<br />

special management <strong>of</strong> scheduled<br />

wastes and accompanied by a<br />

prescribed fee <strong>of</strong> RM300.<br />

E-Wastes<br />

Electrical and electronic wastes<br />

or the so called E-waste has<br />

become a serious environmental<br />

and health challenge because it<br />

is potentially hazardous and also<br />

due to the fact that it is being<br />

generated at an alarming rate. It is<br />

estimated that in the US, by 2007<br />

7

8 COVER FEATURE<br />

THE INGENIEUR<br />

Export <strong>of</strong> waste<br />

there will more than 700 million<br />

obsolete computers. European<br />

studies indicated that E-waste is<br />

increasing by three to five % per<br />

annum. Other than computers,<br />

the used <strong>of</strong> mobile phones are<br />

also growing exponentially. With<br />

only 16 million users in 1991 it<br />

has grown to 1.3 billion in 2003<br />

globally. In <strong>Malaysia</strong> currently,<br />

there are more than 10 million<br />

subscribers. This growth creates<br />

waste as the end <strong>of</strong> life mobile<br />

phones have to be discarded. It is a<br />

challenge to ensure all these wastes<br />

do not end up in the landfills<br />

and releasing toxic substances<br />

to the environment. Computer<br />

scrap contains heavy metal such<br />

as lead, chromium and mercury<br />

that can be hazardous to human<br />

health and the environment if not<br />

managed properly. We should<br />

also be vigilant against dumping <strong>of</strong><br />

used computers or mobile phones<br />

in the guise <strong>of</strong> refurbishment and<br />

recycling.<br />

R e a l i s i n g t h e p o t e n t i a l<br />

environmental impact if E-wastes<br />

are disposed indiscriminately,<br />

the Department <strong>of</strong> Environment<br />

h a s i n c l u d e d t h e s e wa s t e s<br />

as scheduled wastes in the<br />

Environmental Quality (Scheduled<br />

Wastes) Regulation 2005. These<br />

wastes are categorised as ‘waste<br />

from electrical and electronic<br />

assemblies containing components<br />

such as accumulators, mercuryswitches,<br />

glass from cathode-ray<br />

tubes and other activated glass<br />

or polychlorinated biphenylcapacitors,<br />

or contaminated with<br />

cadmium, mercury, lead, nickel,<br />

chromium, copper, lithium, silver,<br />

manganese or polychlorinated<br />

biphenyl’. As this is a new<br />

category <strong>of</strong> wastes, existing<br />

operators are allowed to continue<br />

with their activity <strong>of</strong> recovery<br />

under license. The Department<br />

has licensed 30 facilities for partial<br />

recovery and one for full recovery<br />

<strong>of</strong> E-wastes. Partial recovery refers<br />

to the process where the recovered<br />

materials, in this instance metals,<br />

require further recovery process<br />

to produce the final product.<br />

The partially recovered materials<br />

are still considered as scheduled<br />

wastes and need to be treated at<br />

prescribed premises.<br />

Basel Convention On The<br />

Transboundary Movements Of<br />

Hazardous Wastes And Their<br />

Disposal 1989<br />

Concerned and alarmed at<br />

the uncontrolled and unregulated<br />

movements <strong>of</strong> hazardous wastes,<br />

the United Nation Environment<br />

Programme (UNEP) initiated and<br />

promoted the Basel Convention<br />

on the Transboundary Movements<br />

<strong>of</strong> Hazardous Wastes and Their<br />

Disposal in 1989 that was adopted<br />

at a ministerial conference in Basel,<br />

Switzerland on March 22, 1989<br />

and signed by 116 countries. The<br />

Basel Convention, with its many<br />

apparent weaknesses has been a<br />

good attempt by the international<br />

community to respond to the urgent<br />

question <strong>of</strong> uncontrolled movement<br />

<strong>of</strong> hazardous wastes.<br />

The main objectives <strong>of</strong> the Basel<br />

Convention are:<br />

(i) To protect human health and<br />

the environment from adverse<br />

effects <strong>of</strong> hazardous wastes;<br />

and<br />

(ii) To reduce their generation<br />

and transboundary movement<br />

and to ensure environmentally<br />

s o u n d m a n a g e m e n t o f<br />

hazardous wastes.<br />

The Convention addresses<br />

the need to protect countries<br />

against illegal importation and<br />

to strengthen the capacity <strong>of</strong> all<br />

states to adequately manage their<br />

hazardous wastes.<br />

Old computers

THE INGENIEUR COVER FEATURE<br />

During its first decade, the<br />

Convention was principally devoted<br />

to setting up a framework for<br />

controlling the “transboundary”<br />

movements <strong>of</strong> hazardous wastes,<br />

that is, the movement <strong>of</strong> hazardous<br />

wastes across international frontiers.<br />

During the next decade, the<br />

Convention will build on this<br />

framework by emphasizing full<br />

implementation and enforcement<br />

<strong>of</strong> the treaty’s commitments. The<br />

Basel Convention contains specific<br />

provisions for the monitoring <strong>of</strong><br />

implementation and compliance.<br />

A number <strong>of</strong> articles in the<br />

Convention oblige parties to take<br />

appropriate national measures<br />

to implement and enforce its<br />

provisions, including measures<br />

to prevent and punish acts <strong>of</strong><br />

contravention <strong>of</strong> the Convention.<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong> became a Party to<br />

the Basel Convention on October<br />

8, 1993 and as <strong>of</strong> April 2007<br />

the total number <strong>of</strong> parties to<br />

the Convention stood at 169.<br />

The Department <strong>of</strong> Environment<br />

(DOE) is the competent authority<br />

in the implementation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Basel Convention in <strong>Malaysia</strong>.<br />

National legislation in the form <strong>of</strong><br />

Section 34B <strong>of</strong> the Environmental<br />

Quality Act 1974 on the control<br />

<strong>of</strong> scheduled wastes and the<br />

Environmental Quality (Scheduled<br />

Wastes) Regulations 2005 have been<br />

enacted to regulate, control and<br />

restrict movements <strong>of</strong> hazardous<br />

wastes to be exported, imported<br />

or transit in the country. A control<br />

mechanism based on prior written<br />

notification and consent was also<br />

put into place in line with the<br />

provisions <strong>of</strong> the Convention.<br />

However, the transboundary<br />

movement <strong>of</strong> hazardous wastes is<br />

regulated under the Customs Act<br />

<strong>of</strong> 1967, specifically the Customs<br />

(Prohibition <strong>of</strong> Import) Order<br />

1993 and 1998 and the Customs<br />

(Prohibition <strong>of</strong> Export) Order 1993<br />

and 1998. The export and import<br />

<strong>of</strong> wastes as listed in the Orders<br />

have to be accompanied by a<br />

letter <strong>of</strong> approval issued by the<br />

Director-General <strong>of</strong> Environmental<br />

Quality. Hence the Royal Customs<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>Malaysia</strong> plays a<br />

very important role in preventing<br />

the illegal trafficking <strong>of</strong> hazardous<br />

waste through prohibition <strong>of</strong> imports<br />

and exports <strong>of</strong> waste governed by<br />

the above national legislations.<br />

The movement <strong>of</strong> wastes is<br />

monitored using consignment notes.<br />

Section 34B <strong>of</strong> the Environmental<br />

Quality Act, 1974 provides the<br />

maximum penalty <strong>of</strong> RM500,000 or<br />

imprisonment for a period <strong>of</strong> five<br />

years or both for any violation <strong>of</strong><br />

this section.<br />

SCHEDULED WASTE<br />

MANAGEMENT FACILITIES<br />

In addition to the legal provisions<br />

mentioned above, the Government<br />

was aware <strong>of</strong> the need to set up a<br />

proper hazardous wastes treatment<br />

and disposal facility in the country.<br />

In this manner, the Government<br />

promoted the establishment <strong>of</strong><br />

environmentally sound treatment,<br />

recovery and disposal facilities.<br />

Such facilities were also required<br />

to support the enforcement <strong>of</strong><br />

legal provisions on scheduled<br />

waste. By having such facilities,<br />

industries in <strong>Malaysia</strong> are able<br />

to dispose waste in an orderly,<br />

regulated manner to avoid costly<br />

movements to other countries, and<br />

even more importantly, to avoid<br />

unnecessary risk to public health<br />

Clinical waste<br />

and the environment during its<br />

transport. To date two facilities<br />

have been licensed for treatment<br />

and disposal <strong>of</strong> scheduled wastes,<br />

one in Negeri Sembilan and the<br />

other in Sarawak. Beside these,<br />

there are three operators that are<br />

licensed to treat clinical wastes<br />

and 65 <strong>of</strong>f-site facilities that are<br />

able to accept scheduled wastes<br />

for recovery.<br />

ISSUES AND CHALLENGES<br />

IN HAZARDOUS WASTE<br />

MANAGEMENT<br />

The 15 years experience gained<br />

through the administration <strong>of</strong><br />

the scheduled wastes regulations<br />

indicate that hazardous waste<br />

management in the country has to a<br />

great extent, met the primary goals<br />

<strong>of</strong> the EQA. In 2005, the industries<br />

generated about 5,490,000 tonnes<br />

<strong>of</strong> scheduled wastes. Of these, 27%<br />

were sent for <strong>of</strong>f-site recovery, 20%<br />

disposed 22% treated on-site, 30%<br />

stored on-site and a small quantity<br />

exported for recovery. Most <strong>of</strong> the<br />

industries are managing hazardous<br />

waste in accordance with the<br />

control procedures. However<br />

there are still issues that confront<br />

the authorities in dealing with the<br />

management <strong>of</strong> scheduled wastes.<br />

These include illegal dumping,<br />

increasing request to recover/reuse<br />

wastes and the new and emerging<br />

issue <strong>of</strong> contaminated land.<br />

9

10 COVER FEATURE<br />

THE INGENIEUR<br />

Illegal Dumping Of<br />

Scheduled Wastes<br />

Generally, there seems to be<br />

an increase in the number <strong>of</strong><br />

illegal dumping cases detected<br />

by the Department in the last five<br />

years, from three cases in 2001 to<br />

31 cases in 2005. The types <strong>of</strong><br />

wastes dumped were mainly waste<br />

paint, mineral oil and dross. These<br />

activities were mostly carried out in<br />

secluded areas to avoid detection.<br />

There were also factories that<br />

bury their wastes within their<br />

premises. However the amount<br />

<strong>of</strong> wastes dumped illegally were<br />

small compared to the total amount<br />

wastes generated in the country.<br />

This does not mean that we can<br />

treat this issue lightly because<br />

these wastes can contaminate<br />

groundwater and nearby rivers and<br />

affect public health.<br />

The reason for illegal dumping<br />

cannot be a lack <strong>of</strong> facilities<br />

available because we have state<strong>of</strong>-the-art<br />

facilities for integrated<br />

hazardous wastes treatment and<br />

disposal. I believe it is the lack<br />

<strong>of</strong> awareness, accountability,<br />

responsibility and sheer wanton<br />

disregard for the environment and<br />

public safety, as well as greed for<br />

maximum pr<strong>of</strong>it.<br />

Recovery/Reuse Of Wastes<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong> upholds practices and<br />

promotes resource conservation;<br />

any wastes that could be utilised<br />

should be reprocessed into useful<br />

products. Whilst we encourage<br />

wastes recovery and reuse, we also<br />

received applications that might<br />

be questionable such as recovery<br />

<strong>of</strong> products that might still be<br />

considered as scheduled wastes.<br />

Many applications have also been<br />

received requesting that their waste<br />

be not categorised as scheduled<br />

wastes thus effectively permitting<br />

d i s p o s a l a t n o n - p r e s c r i b e d<br />

facilities. The Department has to<br />

take cognizance <strong>of</strong> the agreement<br />

between the Government <strong>of</strong><br />

Contaminated land<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong> and Kualiti Alam Sdn Bhd<br />

that amongst others prohibits the<br />

issuance <strong>of</strong> any license for another<br />

treatment and disposal facility in<br />

Peninsular <strong>Malaysia</strong>. This includes<br />

<strong>of</strong>f-site incineration <strong>of</strong> scheduled<br />

wastes.<br />

Contaminated Land<br />

Although the EQA provided<br />

powers to prohibit pollution <strong>of</strong><br />

any soil or surface <strong>of</strong> any land, it<br />

has not gone further to specify the<br />

acceptable conditions for deposition<br />

<strong>of</strong> wastes into this segment or<br />

element <strong>of</strong> the environment.<br />

However, Environmental Quality<br />

(Scheduled Wastes) Regulations<br />

2005 categorised contaminated<br />

soil, debris or matter resulting from<br />

Motor workshop waste<br />

clean-up <strong>of</strong> a spill <strong>of</strong> chemical,<br />

mineral oil or scheduled waste<br />

as a scheduled waste and is<br />

subjected to the provisions <strong>of</strong><br />

the scheduled waste regulations<br />

requiring treatment or disposal at<br />

prescribed premises.<br />

Potential contaminated land can<br />

be found in places such as motor<br />

workshops, petrol stations, fuel oil<br />

depots, railway yards, bus depots,<br />

landfills, industrial sites and sites<br />

with underground storage tanks.<br />

These places generate spent diesel,<br />

lube oil, other hydrocarbons,<br />

solvents and grease which if not<br />

properly managed could end-up<br />

polluting the soil and groundwater<br />

through leakage and seepage.<br />

There are also contaminated sites<br />

that remain hidden or unknown<br />

such as municipal landfill and<br />

refuse dumping sites that have been<br />

abandoned in the past.<br />

Assessment on soil contamination<br />

at industrial premises is still adhoc<br />

and has yet to provide any<br />

significant pr<strong>of</strong>ile on the status <strong>of</strong><br />

soil quality. These were carried<br />

out on some <strong>of</strong> the sites where<br />

illegal dumping <strong>of</strong> hazardous<br />

waste occurred. In most <strong>of</strong> these<br />

cases, the factory owners were<br />

required to carry out clean-up<br />

and post-monitoring <strong>of</strong> the sites.

THE INGENIEUR COVER FEATURE<br />

11<br />

Besides illegal dumping cases, the<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Environment was<br />

also alerted on the assessment and<br />

clean-up <strong>of</strong> decommissioned petrol<br />

stations.<br />

Realising the importance <strong>of</strong><br />

dealing with contaminated land,<br />

the Department <strong>of</strong> Environment<br />

has created a section in the<br />

Hazardous Substances Division<br />

to look into this issue. There is<br />

a need to develop criteria and<br />

standards for contaminated soil in<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong>. Prior to any formulation<br />

<strong>of</strong> clearer policies and legal limits<br />

for soil, it is imperative that a<br />

compilation <strong>of</strong> contaminated soil<br />

status be initiated and a set <strong>of</strong> soil<br />

pollution guidelines be drawn up<br />

to assist both public and private<br />

sectors in managing this problem.<br />

Of course there is also a need<br />

to build capacity and capability<br />

on the assessment and clean-up<br />

methodologies and techniques.<br />

CONTROL MEASURES<br />

Illegal dumping <strong>of</strong> scheduled<br />

wastes remains a challenge. From<br />

2001-2005 there were 90 cases<br />

<strong>of</strong> illegal dumping detected but<br />

Illegal dump site<br />

only 39 were prosecutable in the<br />

court <strong>of</strong> law. This is due to the<br />

lack <strong>of</strong> evidence and the nature<br />

<strong>of</strong> the crime. Various actions<br />

have been instituted to tackle this<br />

environmental crime. These include<br />

the setting up <strong>of</strong> an intelligence<br />

unit to gather information from<br />

individuals and groups to detect and<br />

prevent environmental crimes. The<br />

assistance <strong>of</strong> RELA <strong>of</strong>ficers to detect<br />

illegal dumping activities and other<br />

environmental violations. Audits<br />

on waste generators, recyclers and<br />

disposal facilities were carried<br />

out in a systematic and regular<br />

manner. Special training modules<br />

have been prepared and training<br />

provided to <strong>of</strong>ficers to enable<br />

them to conduct their tasks more<br />

effectively. The Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Environment is also reviewing the<br />

Environmental Quality Act 1974<br />

amongst others to introduce new<br />

provisions to facilitate effective and<br />

efficient enforcement <strong>of</strong> the laws.<br />

Stiffer penalties such as mandatory<br />

jail sentence especially for illegal<br />

dumping <strong>of</strong> scheduled wastes have<br />

been proposed.<br />

However contaminated land<br />

is an emerging issue that, if not<br />

addressed, may give rise to problems<br />

relating to health and safety <strong>of</strong> users,<br />

pollution <strong>of</strong> surface and ground<br />

water and financial implications.<br />

Programmes to develop national<br />

criteria and standards prior to<br />

formulation <strong>of</strong> dedicated legislation<br />

would be undertaken. Experience in<br />

other countries will provide useful<br />

guidance and reference to <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

in the implementation <strong>of</strong> these<br />

programmes.<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

The Environmental Quality<br />

(Scheduled Wastes) Regulations<br />

1989, have served its purpose in<br />

providing the essential regulatory<br />

framework on scheduled waste<br />

management in <strong>Malaysia</strong> despite<br />

constraints faced in administering<br />

it’s various provisions. Based<br />

on the experience gained in<br />

the 15 years <strong>of</strong> enforcing the<br />

scheduled wastes regulations,<br />

the Department <strong>of</strong> Environment<br />

enacted the Environmental Quality<br />

(Scheduled Wastes) Regulations<br />

2005, amongst others to redefine<br />

waste categories; to exclude wastes<br />

that are not characterised as<br />

hazardous; to provide avenue for<br />

special management <strong>of</strong> wastes and<br />

to improve tracking <strong>of</strong> wastes.<br />

Waste disposal will not become<br />

cheaper hence it is prudent for<br />

industries to engage in waste<br />

minimisation. This could be done<br />

through process or raw material<br />

changes. If this is not possible<br />

then wastes should be reused<br />

or recovered. Industries should<br />

embark on cleaner technology<br />

to eliminate or reduce waste<br />

generation. An industry that<br />

engages in cleaner technology can<br />

be cleaner by reducing hazardous<br />

emissions, cheaper by saving<br />

money and smarter by conserving<br />

resources. BEM<br />

Note: Views expressed are<br />

not necessarily those <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Environment.

12 COVER FEATURE<br />

THE INGENIEUR<br />

Life Cycle Inventorisation<br />

Between Open Dumps And<br />

Sanitary Landfills<br />

By Abdul Nasir Abdul Aziz, Local Government Department,<br />

Ministry <strong>of</strong> Housing and Local Government, <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

Mohd. Nasir Hassan and Muhamad Awang, Faculty <strong>of</strong> Environmental Sciences,<br />

Universiti Putra <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

In <strong>Malaysia</strong>, disposal <strong>of</strong> solid waste onto lands or landfill is still the<br />

most common method. Despite the country’s rapid economic growth<br />

and significant improvement in the standards <strong>of</strong> living, most <strong>of</strong><br />

these landfill sites are still open dumps and only a few sites can be<br />

categorised as sanitary landfills (Local Govt. Dept., 2005). Sanitary<br />

landfills are solid waste disposal sites that are properly planned<br />

before construction and have gone through the Environmental<br />

Impacts Assessment (EIA) process, developed and operated with<br />

proper environmental protection and pollution control facilities<br />

and finally have proper plans for closure and post-closure.<br />

The environmental impacts <strong>of</strong> open dumps can be significant,<br />

mainly from uncontrolled and unregulated leachate generation and<br />

gas emissions. Hence, the Government <strong>of</strong> <strong>Malaysia</strong> is striving to<br />

improve the disposal systems for solid wastes as part <strong>of</strong> its solid<br />

waste strategic and action plan. The first step is to phase out open<br />

dumps and secondly in the future, to introduce sanitary landfill<br />

systems. This strategic move however, requires objective information<br />

about the relative environmental impacts between open dumps and<br />

sanitary landfills. To date, not much information has been published<br />

about the two systems.<br />

This paper discusses the environmental burdens released by<br />

open dumps and they are compared to those released by sanitary<br />

landfills. The comparison is made using the Life Cycle Assessment<br />

(LCA) technique that assesses potential environmental impacts <strong>of</strong><br />

products, processes and activities comprehensively from its cradle<br />

to grave.<br />

Sanitary landfill, Air Hitam Selangor<br />

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)<br />

is a process to analyse the<br />

materials, energy, emissions,<br />

and wastes <strong>of</strong> a product or service<br />

system, over the whole Life Cycle<br />

‘from cradle to grave’ (McDougall<br />

et al., 2001). LCA is being used to<br />

examine every stage <strong>of</strong> the life cycle<br />

<strong>of</strong> a product, process or activity,<br />

from raw materials acquisition,<br />

through manufacture, distribution,<br />

use, possible reuse or recycling<br />

and then final disposal (Vigon et<br />

al, 1992). In LCA, all ‘upstream’<br />

and ‘downstream’ effects <strong>of</strong> the<br />

activities are considered.<br />

LCA process is divided into<br />

four stages as shown in Figure 1:<br />

Goal Definition and Scope, Life<br />

Cycle Inventory Analysis (LCI), Life<br />

Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)<br />

and Life Cycle Interpretation.<br />

These four stages are intended to<br />

assist resource and environmental<br />

managers to encourage better<br />

product design, more effective<br />

process with respect to raw<br />

material inputs or waste outputs,<br />

improve transportation methods,<br />

more careful consumer use and<br />

better waste disposal practices.<br />

In the context <strong>of</strong> resource and<br />

environmental management, LCA<br />

is intended to lead to decisions<br />

which result in greater conservation<br />

<strong>of</strong> resources and the environment,<br />

increased energy conservation<br />

and decreased waste generation,<br />

improved industrial processes<br />

related to providing resource-based<br />

products, and fewer problems in<br />

final disposal.

THE INGENIEUR COVER FEATURE<br />

13<br />

Life cycle assessment framework<br />

Goal and<br />

scope<br />

definition<br />

Inventory<br />

analysis<br />

Impact<br />

assessment<br />

I<br />

n<br />

t<br />

e<br />

r<br />

p<br />

r<br />

e<br />

t<br />

a<br />

t<br />

i<br />

o<br />

n<br />

Figure 1: Phases <strong>of</strong> an LCA (ISO 14040, 1997)<br />

C u r r e n t w o r l d w i d e<br />

environmental concerns have<br />

made Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) a<br />

useful tool for prioritising efforts,<br />

goal setting, and measuring<br />

environmental quality improvement<br />

<strong>of</strong> almost any plan <strong>of</strong> action<br />

and in this paper, LCI is used<br />

to evaluate all the inputs and<br />

outputs <strong>of</strong> an open dump and a<br />

sanitary landfill. The LCI model<br />

takes an overall approach <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Energy<br />

Figure 2: MSW management system boundary<br />

Direct applications:<br />

• Product development<br />

and improvement<br />

• Strategic planning<br />

• Public policy making<br />

• Marketing<br />

• Other<br />

investigation the different types <strong>of</strong><br />

MSW management system and the<br />

general LCI system boundaries <strong>of</strong><br />

the MSW management system as<br />

shown in Figure 2.<br />

LCI OF LANDFILLS<br />

The total life cycle inventory<br />

model for landfill consists <strong>of</strong> the<br />

inventory <strong>of</strong> energy consumption,<br />

air emissions and water emissions<br />

Residential/Commercial/Institutional<br />

during the phase <strong>of</strong> landfill<br />

construction, operation, closure<br />

and post-closure care. However, in<br />

this study only landfill operation,<br />

leachate gas emission and leachate<br />

generation were modelled.<br />

● Energy Consumption<br />

for Landfills<br />

For energy consumption, fuel<br />

(diesel) and electricity consumption<br />

during landfill operation was<br />

modelled to estimate the energy<br />

consumed in term <strong>of</strong> kWh <strong>of</strong><br />

electricity and the amount <strong>of</strong><br />

fuel (diesel) for managing one<br />

ton <strong>of</strong> solid waste in landfill.<br />

The electricity consumption<br />

during landfill operation was the<br />

electricity consumed for lighting<br />

<strong>of</strong> administration building, garage,<br />

site, and operation <strong>of</strong> weighbridge<br />

and leachate treatment plant.<br />

Diesel consumption is the amounts<br />

consumed by landfill machineries<br />

to place, spread and compact<br />

the waste, and transport, spread<br />

<strong>of</strong> daily, intermediate and final<br />

cover.<br />

● Gas Generation from Landfills<br />

The estimation <strong>of</strong> the quantity<br />

<strong>of</strong> landfill gas generated from<br />

Raw materials<br />

Waste separation facility Composting facility Incineration Landfill<br />

Recycling processes<br />

Recyclable materials<br />

Collection<br />

Transfer station<br />

Compost<br />

Energy<br />

MSW system<br />

boundary<br />

Air<br />

Emissions<br />

Water<br />

Emissions<br />

Waste<br />

Residue

14 COVER FEATURE<br />

THE INGENIEUR<br />

Table 1: Modelling <strong>of</strong> BOD and COD concentration in landfill leachate<br />

Age <strong>of</strong> waste (year) BOD conc. (mg/l) BOD/COD ratio COD conc. (mg/l)<br />

0 – 5 17500 – 2500<br />

Linear decrease<br />

5 – 10 2500 – 500<br />

Linear decrease<br />

10 - 20 500 – 50<br />

Linear decrease<br />

Source: Haniba, et. al., 1999<br />

landfill was modelled using the<br />

triangle gas production model<br />

(Tchobanoglous, 1993) that divides<br />

waste into two categories, i.e.,<br />

rapidly biodegradable waste (RBW)<br />

and slowly biodegradable waste<br />

(SBW). The RBW gas generation<br />

rate was assumed to peak at the<br />

end <strong>of</strong> year one after waste was<br />

land filled and totally decomposed<br />

after five years, while for SBW<br />

was assumed to peak at year five<br />

and totally decomposed after 15<br />

years land filled. The composition<br />

<strong>of</strong> landfill gas was in the range <strong>of</strong><br />

45% to 60% for CH 4 and 40%<br />

to 60% for CO 2 (Tchobanoglous,<br />

1993) and for the purpose <strong>of</strong> the<br />

generation estimation <strong>of</strong> CH 4 and<br />

CO 2 from landfills in <strong>Malaysia</strong>, the<br />

percentage <strong>of</strong> CH 4 emission was<br />

55% and 45% for CO 2 emission.<br />

The estimation <strong>of</strong> the amount<br />

<strong>of</strong> traces gases such as NH 4 ,<br />

Total HC and Total NMVOC was<br />

estimated using USEPA AP 42<br />

model (USEPA, 1997).<br />

● Leachate Generation<br />

The leachate quantity generated<br />

from landfills was estimated<br />

using water balance method<br />

(Tchobanoglous, 1993). The BOD<br />

concentration in the leachate was<br />

modelled by assuming that BOD<br />

concentration started at high<br />

concentration and diminished over<br />

time as the waste aged. The COD<br />

concentrations were calculated<br />

using BOD/COD ratio <strong>of</strong> landfill<br />

leachate and other pollutants<br />

in landfill leachate are assumed<br />

constant through landfill design<br />

0.64 - 0.17 27500 – 15000<br />

Linear decrease<br />

0.17 15000 – 3000<br />

Linear decrease<br />

0.17- 0.05 3000 – 1000<br />

Linear decrease<br />

life. The modelling <strong>of</strong> BOD and<br />

COD concentration is shown in<br />

Table 1. The leachate quality used<br />

for estimating water emissions was<br />

the raw leachate from Air Hitam,<br />

Puchong landfill (MOHLG, 2005)<br />

as tabulated in Table 2.<br />

Table 2: Raw leachate from Air Hitam, Puchong Landfill<br />

● Functional Unit used in<br />

the Study<br />

The functional unit <strong>of</strong> this study<br />

was the average total tonnage <strong>of</strong><br />

MSW generated per year for the<br />

duration <strong>of</strong> 20 years design life <strong>of</strong><br />

landfill based on 2,257 ton per<br />

Parameters Unit Average Std. Dev<br />

BOD5 mg/l 1964.00 455.44<br />

COD mg/l 6392.00 743.99<br />

SS mg/l 420.00 158.03<br />

Hg mg/l 0.001 0.00<br />

Cd mg/l 0.02 0.01<br />

Cr (Hexavalent) mg/l 0.28 0.11<br />

Cu mg/l 0.02 0.00<br />

As mg/l 0.53 0.21<br />

Cy mg/l 0.12 0.06<br />

Pb mg/l 0.05 0.00<br />

Cr (Trivalent) mg/l 0.21 0.15<br />

Mn mg/l 0.08 0.02<br />

Ni mg/l 0.13 0.04<br />

Sn mg/l 0.46 0.31<br />

Zn mg/l 0.44 0.15<br />

Boron mg/l 43.38 90.35<br />

Fe mg/l 3.09 0.82<br />

Phenol mg/l 0.60 0.19<br />

Free chlorine mg/l 0.1 0.00<br />

Sulphide mg/l 3.90 5.32<br />

Oil & grease mg/l ND ND<br />

Ammoniacal Nitrogen mg/l 2934.00 505.40<br />

P mg/l 19.40 5.48<br />

Total Nitrogen mg/l 3452.00 62.21<br />

Dissolved solid mg/l 19220.00 258.84<br />

Source: MOHLG (2002), The Design, Construction, Completion and<br />

commisioning <strong>of</strong> Rawang Sanitary Landfill Project in Selangor, <strong>Malaysia</strong>. Design<br />

Brief, Vol. 3-Appendices

THE INGENIEUR COVER FEATURE<br />

15<br />

Table 3: The composition <strong>of</strong> Kuala Lumpur’s MSW<br />

Type <strong>of</strong> waste Composition (% by weight)<br />

Food waste<br />

Yard waste<br />

Mixed paper<br />

Mixed plastic<br />

Textiles<br />

Ferrous<br />

Non-ferrous<br />

Glass<br />

Others<br />

day (Hassan et al, 2000) generated<br />

in the Federal Territory <strong>of</strong> Kuala<br />

Lumpur. The rainfall intensity was<br />

2,495 mm/yr and evaporation rate<br />

was 1,165 mm/yr. The composition<br />

<strong>of</strong> Kuala Lumpur’s MSW that were<br />

used in this study is shown in<br />

Table 3.<br />

The system boundary for lifecycle<br />

inventory <strong>of</strong> landfill is shown<br />

in Figure 3.<br />

● Other Assumptions Used in<br />

the Study<br />

The other assumptions that<br />

were made in facilitating this study<br />

are listed below:<br />

(i) Cover soil ratio to waste<br />

is 1:5<br />

(ii) Fuel economy for tipper is<br />

0.18l/km<br />

(iii) The distance from landfill to<br />

the source <strong>of</strong> cover material<br />

is 5km<br />

56.3<br />

6.9<br />

8.2<br />

13.1<br />

1.3<br />

2.1<br />

0.3<br />

1.5<br />

10.3<br />

Total 100<br />

Moisture content<br />

Source: Nazeri, 2002<br />

56.3<br />

Energy<br />

Raw<br />

materials<br />

Waste collection<br />

Landfill gas<br />

treatment<br />

Figure 3: Landfilling system boundary<br />

Landfill<br />

Leachate<br />

treatment<br />

Air<br />

emissions<br />

Water<br />

emissions<br />

Residual<br />

waste<br />

(iv) The fuel consumption <strong>of</strong><br />

landfill equipment is 1l/ton<br />

(v) The electricity consumption<br />

<strong>of</strong> sanitary landfill is 3.78<br />

kW/h/ton<br />

(vi) The electricity consumption<br />

<strong>of</strong> open dump is 0.23 kWh/<br />

ton<br />

(vii) L a n d f i l l g a s r e c o v e r y<br />

efficiency for sanitary landfill<br />

is 75%<br />

(viii) Landfill gas trapped in<br />

landfill is 15%<br />

(ix) Landfill gas released to<br />

environment is 10%<br />

(x) Landfill gas released to<br />

environment from open<br />

dump is 85%<br />

Energy consumption (GJ)/Tonne <strong>of</strong> Waste<br />

Open dump 4.30E+04<br />

Sanitary landfill 7.31E+04<br />

(xi) CH 4 combustion efficiency<br />

is 100%<br />

(xii) Landfill gas treatment for<br />

sanitary landfill is flaring<br />

(xiii) Leachate treatment for<br />

sanitary landfill is SBR with<br />

GAC filter<br />

RESULTS<br />

The summarized results <strong>of</strong><br />

energy consumption, air emissions<br />

and water emissions <strong>of</strong> the open<br />

dump and sanitary landfill are<br />

shown in Table 4, Table 5 and<br />

Table 6.<br />

● Energy Consumption Between<br />

Open Dumps and Sanitary<br />

Landfills<br />

Between the two, it is obvious<br />

that sanitary landfill consumed<br />

more energy than open dump.<br />

The energy consumed by sanitary<br />

landfill was 7.31E+04 GJ per year,<br />

3.01E+04 GJ more than open<br />

dump. The high consumption <strong>of</strong><br />

energy by sanitary landfill was due<br />

to facilities used by sanitary landfill<br />

such as leachate treatment plant,<br />

site lighting and administration<br />

building that are not available at<br />

open dump.<br />

● Air Emissions Between Open<br />

Dumps and Sanitary Landfills<br />

The highest CH 4 emission was<br />

emitted by open dump with the<br />

amount <strong>of</strong> 5.63E+06 kg per year.<br />

While, sanitary landfill emitted<br />

more CO 2 (fossil) and N 2 O than<br />

open dump with the amount per<br />

year <strong>of</strong> 1.38E+07 kg and 1.84E+02<br />

kg, respectively.<br />

For other air emissions such as<br />

HCl, HF, NH 4 , NO x , SO x and total<br />

metals, sanitary landfill was emitted<br />

more than open dump except for<br />

total HC and total NMVOC. The<br />

Table 4: Energy consumption <strong>of</strong> open dump and sanitary landfill

16 COVER FEATURE<br />

THE INGENIEUR<br />

Table 5: Life Cycle inventory <strong>of</strong> open dump and sanitary landfill (Air emissions)<br />

Parameter Unit/Tonne <strong>of</strong> Waste Open dump Sanitary landfill<br />

CH 4<br />

CO 2 (fossil)<br />

N 2 O<br />

HCl<br />

HF<br />

NH 4<br />

NO x<br />

SO x<br />

Total HC<br />

Total NMVOC<br />

Total Metals<br />

high emissions <strong>of</strong> HCl, HF, NH 4 ,<br />

NO x , SO x were due to the process<br />

<strong>of</strong> electricity generation and the<br />

production and use <strong>of</strong> diesel fuel.<br />

As for the emission <strong>of</strong> total HC<br />

and total NMVOC, the emissions<br />

<strong>of</strong> these compounds were due to<br />

decomposition process <strong>of</strong> organic<br />

matter in landfill.<br />

kg<br />

kg<br />

kg<br />

kg<br />

kg<br />

kg<br />

kg<br />

kg<br />

kg<br />

kg<br />

kg<br />

● Water Emissions<br />

5.63E+06<br />

3.89E+06<br />

8.48E+01<br />

3.27E+01<br />

3.45E+00<br />

7.20E-01<br />

6.10E+04<br />

5.84E+03<br />

7.83E+02<br />

5.12E+03<br />

3.20E+00<br />

Table 6: Life Cycle inventory <strong>of</strong> open dump and sanitary landfill (Water emissions)<br />

Dump site<br />

Open dump had the overall<br />

highest output <strong>of</strong> water emissions<br />

for all parameters studied except<br />

PO 4 as compared to sanitary<br />

landfill.<br />

B O D a n d C O D e m i t t e d<br />

per year by open dump were<br />

6.90E+05<br />

1.38E+07<br />

1.84E+02<br />

4.39E+02<br />

4.60E+01<br />

1.05E+01<br />

1.52E+05<br />

2.07E+04<br />

3.36E+02<br />

2.20E+03<br />

9.20E+01<br />

Parameter Unit/Tonne <strong>of</strong> Waste Open dump Sanitary landfill<br />

BOD<br />

COD<br />

N<br />

NH 3<br />

P<br />

PO 4<br />

Total Metals<br />

kg<br />

kg<br />

kg<br />

kg<br />

kg<br />

kg<br />

kg<br />

4.42E+06<br />

1.19E+07<br />

4.64E+06<br />

3.95E+06<br />

2.61E+04<br />

9.34E+00<br />

6.43E+03<br />

8.84E+04<br />

2.38E+05<br />

4.64E+04<br />

4.96E+04<br />

2.61E+02<br />

1.34E+02<br />

3.46E+03<br />

4.42E+06 kg and 1.19E+07 kg,<br />

respectively, while sanitary landfill<br />

emitted 8.84E+04 kg <strong>of</strong> BOD and<br />

2.38E+05 kg <strong>of</strong> COD.<br />

However, sanitary landfill<br />

emitted higher PO 4 with 1.34E+02<br />

kg per year as compared to<br />

9.34E+00 kg by open dump. The<br />

high emission <strong>of</strong> PO 4 is due to<br />

the high consumption <strong>of</strong> electrical<br />

energy and diesel fuel.<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

Open dumps are obviously<br />

the main culprit for the aquatic<br />

degradation since leachate<br />

discharge from it does not go<br />

through any sort <strong>of</strong> treatment.<br />

However, as for air pollution, open<br />

dumps only play an important<br />

role in discharging high volume<br />

<strong>of</strong> CH to the environment while<br />

4<br />

sanitary landfill discharge the<br />

majority <strong>of</strong> other air pollutants<br />

under studied due to the greater<br />

consumption <strong>of</strong> electricity and<br />

diesel. BEM

THE INGENIEUR COVER FEATURE<br />

17<br />

REFERENCES<br />

Vigon, B. W., D. A. Toller and B. W. Cornary. (1992). Life Cycle Assessment Inventory Guidelines and<br />

Principles. Lewis.<br />

Tamamushi, K. and P. White. (1998). Applying Life Cycle Assessment To Waste management in Asia.<br />

In: Proceedings <strong>of</strong> the Third International Conference on Ecobalance. Japan, 25-27 November 1998.pp.<br />

501-504.<br />

ENSIC. (1994). A References Handbook for Trainers in Promotion <strong>of</strong> Solid Waste Recycling and Reuse In<br />

the Developing Countries <strong>of</strong> Asia. Kenya.<br />

McDougall, F.R., P.R. White, M. Franke and P. Hindle (2001). Integrated Solid Waste Management:<br />

A Life Cycle Inventory. Blackwell. London.<br />

Hassan, M. N., Y. Kamil, S. Azmin and A.R. Rakmi. (1998). Issue and Problems <strong>of</strong> Solid Waste Management<br />

in <strong>Malaysia</strong>. In: National Review <strong>of</strong> Environmental Quality Management in <strong>Malaysia</strong>: Towards the Next<br />

Two Decades. Nordin, H. Lizuryaty, A. A., Ibrahim, K. (Eds.). Pp.179-225.<br />

Tanaka, M., M. Osaka, T. Fujil, A. Saito, R. Sugiyama and K. Kurihara. (1998). A Study on Comparison<br />

<strong>of</strong> Municipal Solid Waste Management Alternatives Based on Life Cycle Inventory. In: Proceedings <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Third International Conference on Ecobalance. Japan, 25-27 November 1998.pp. 497-500.<br />

White, P. R., M. Frankeand P. Hindle. (1995). Integrated Solid Waste management: A Life Cycle Inventory.<br />

Blackie Academic and Pr<strong>of</strong>essional. Glasgow.<br />

IPCC. (1992). Climate Change. In the IPCC Scientific Assessment. [Eds.] Houghton, J. T.<br />

Coulon, R., V. Camobrece, M. A. Barlar, R. T. Ham, E. Repa and M. Felker. (1998). Life Cycle Inventory<br />

<strong>of</strong> A Modern Municipal Solid Waste Landfill. In: Proceedings <strong>of</strong> the Third International Conference on<br />

Ecobalance. Japan, 25-27 November 1998. pp. 505-508.<br />

Morita, Y. and M. Tokuda. (1998). Life Cycle Assessment <strong>of</strong> Waste Management: A Study <strong>of</strong> City <strong>of</strong><br />

Sendai. In: Proceedings <strong>of</strong> the Third International Conference on Ecobalance. Japan, 25-27 November<br />

1998. pp. 513-516.<br />

Tan, K. K., K. S. Low, S. Pillay and H. Tan. (1986). A computer Simulation Model <strong>of</strong> Solid Waste Management<br />

System. In: Management and Utilization <strong>of</strong> Solid Wastes. Yong, F.F. and Tan, K.K. [Eds.]. pp. 59-83.<br />

Local Government Department, Ministry <strong>of</strong> Housing and Local Government <strong>Malaysia</strong> (2005). National<br />

Strategic Plan for Solid Waste Management.<br />

Ministry <strong>of</strong> Housing and Local Government (MOHLG) (2002), The Design, Construction, Completion<br />

and commisioning <strong>of</strong> Rawang Sanitary Landfill Project in Selangor, <strong>Malaysia</strong>. Design Brief, Vol. 3-<br />

Appendices<br />

Haniba, N. M., Hassan, M. N., Yus<strong>of</strong>f, M. K., Rahman, M., Rajan, S. and Mohamed, H. (1999). Leachate<br />

Quality and Landfill Age: An Overview. In: Proceeding <strong>of</strong> the Workshop on Disposal <strong>of</strong> Solid Waste<br />

through Sanitary Landfill – Mechanisms, Processes, Potential Impacts and Post-closure Management.<br />

Universiti Putra <strong>Malaysia</strong>, 25 – 26 August 1999. pp. 183-193.<br />

USEPA. (1997). Compilation <strong>of</strong> Air Pollutant Emission Factors, Volume 1: Stationary Point and Area Sources,<br />

Fifth Edition, AP-42. Section 2.4, Municipal Solid Waste Landfills. United States Environmental Protection<br />

Agency, Office <strong>of</strong> Air Quality Planning and Standards. Research Triangle Park, NC, USA.<br />

National Pollutant Inventory. (1999). Emission Estimation Technique Manual for Municipal Solid Waste<br />

Landfills Version 1.1. Environment Australia.

18 COVER FEATURE<br />

THE INGENIEUR<br />

Modelling Energy Recovery From<br />

Gasification Of Solid Waste<br />

By Elaine Chan, Environmental Consultant, Perunding Utama Sdn Bhd<br />

Scott Kennedy, Assistant Pr<strong>of</strong>essor, Head <strong>of</strong> Programme, Energy and Environment,<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Science and Technology<br />

Mohd. Nasir Hassan, Faculty <strong>of</strong> Environmental Studies, Universiti Putra <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

Waste is commonly<br />

referred to as unwanted<br />

or discarded by-products<br />

<strong>of</strong> domestic, agricultural and<br />

industrial activities having little or<br />

no economic value. Nonetheless,<br />

waste can also be considered as<br />

a valuable raw material. Today’s<br />

technological advancements and<br />

the pressure to reduce material<br />

wastage foster the emergence <strong>of</strong><br />

markets for waste derived products<br />

such as secondary materials,<br />

fuel, fertilizers, animal feed and<br />

construction materials.<br />

The amount <strong>of</strong> municipal<br />

solid waste (MSW) generated in<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong> is growing with increasing<br />

urbanisation and industrialisation<br />

where an estimated 16,000 tonnes<br />

<strong>of</strong> solid waste is being generated<br />

Wood waste<br />

daily or 5,840 kton/year; an<br />

average <strong>of</strong> 0.8 kg/per capita/day.<br />

Currently, municipal wastes<br />

are disposed at approximately<br />

170 landfills in <strong>Malaysia</strong>, <strong>of</strong><br />

which approximately 10% are<br />

classified as sanitary landfills<br />

and the rest are open dumps<br />

lacking cover materials, leachate<br />

and gas emissions control, and<br />

release uncontrolled emissions to<br />

the air, water and groundwater.<br />

Seven mini-incinerators have been<br />

operating on resort islands but the<br />

amount <strong>of</strong> waste treated and the<br />

current status <strong>of</strong> these incinerators<br />

is not known.<br />

To overcome growing waste<br />

generation and insufficient<br />

waste treatment facilities, the<br />

Government is looking into<br />

Padi husks<br />

introducing thermal treatment<br />

<strong>of</strong> waste. Waste is a renewable<br />

source <strong>of</strong> energy that can be<br />

economically feasible since the<br />

fuel input <strong>of</strong>ten has a negative-cost<br />

and is readily available. Through<br />

thermal treatment, managing the<br />

disposal <strong>of</strong> solid waste can be<br />

coupled with energy recovery and<br />

is referred to as waste-to-energy<br />

(WTE) schemes. The use <strong>of</strong><br />

waste-to-energy (WTE) schemes is<br />

also in line with <strong>Malaysia</strong>’s policy<br />

to diversify fuel types, sources,<br />

technology and to promote the<br />

development <strong>of</strong> renewable energy<br />

and co-generation as much as<br />

possible.<br />

Thermal Treatment Of Waste<br />

Thermal treatment or thermal<br />

processing <strong>of</strong> waste refers to<br />

the conversion <strong>of</strong> solid waste<br />

into gaseous, liquid and solid<br />

conversion products with<br />

concurrent or subsequent release<br />

<strong>of</strong> heat energy (Tchobanoglous et<br />

al., 1993). As shown in Table 1,<br />

thermal treatment can be divided<br />

into combustion or mass burn<br />

incineration, gasification and

THE INGENIEUR COVER FEATURE<br />

19<br />

Table 1: Comparison between thermal treatments<br />

Transformation<br />

means or methods<br />

Auxiliary fuel<br />

during operation<br />

Principal<br />

conversion<br />

products<br />

pyrolysis systems. Essentially,<br />

combustion incinerators operate<br />

in stoichiometric or excess <strong>of</strong> air,<br />

gasification is partial oxidation<br />

<strong>of</strong> carbonaceous fuel under<br />

substochiometric air or starved<br />

air to produce a gaseous product<br />

known as synthesis gas or producer<br />

gas, while pyrolysis processes<br />

waste in the complete absence <strong>of</strong><br />

oxygen.<br />

Gasification is an emerging<br />

technology acknowledged for<br />

its robust performance and is a<br />

potential option to provide for the<br />

lack <strong>of</strong> treatment facilities to treat<br />

growing waste generation as well<br />

as to produce renewable energy.<br />

It comprises a thermochemical<br />

conversion <strong>of</strong> solid or liquid<br />

carbonaceous material to a<br />

combustible gaseous product by<br />

supply <strong>of</strong> a gasification agent (i.e.<br />

air) (Higman & Burth, 2003). In<br />

WTE gasification systems, fuel<br />

is gasified to form producer gas<br />

that is subsequently combusted<br />

to produce high temperatures for<br />

process heat or power generation.<br />

Combustion Gasification Pyrolysis<br />