YEARBOOK OF THE ALAMIRE FOUNDATION

YEARBOOK OF THE ALAMIRE FOUNDATION YEARBOOK OF THE ALAMIRE FOUNDATION

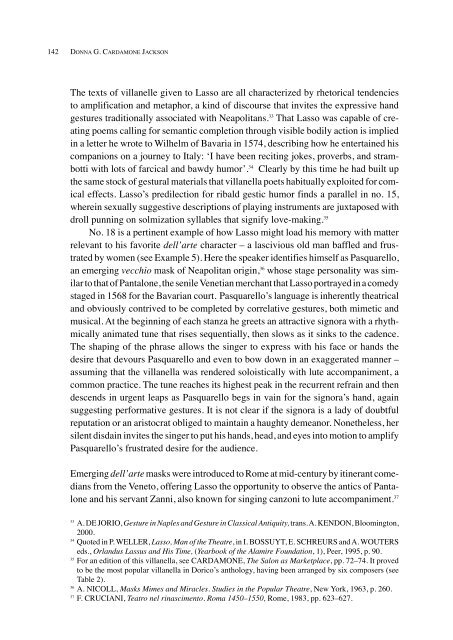

142 DONNA G. CARDAMONE JACKSON The texts of villanelle given to Lasso are all characterized by rhetorical tendencies to amplification and metaphor, a kind of discourse that invites the expressive hand gestures traditionally associated with Neapolitans. 33 That Lasso was capable of creating poems calling for semantic completion through visible bodily action is implied in a letter he wrote to Wilhelm of Bavaria in 1574, describing how he entertained his companions on a journey to Italy: ‘I have been reciting jokes, proverbs, and strambotti with lots of farcical and bawdy humor’. 34 Clearly by this time he had built up the same stock of gestural materials that villanella poets habitually exploited for comical effects. Lasso’s predilection for ribald gestic humor finds a parallel in no. 15, wherein sexually suggestive descriptions of playing instruments are juxtaposed with droll punning on solmization syllables that signify love-making. 35 No. 18 is a pertinent example of how Lasso might load his memory with matter relevant to his favorite dell’arte character – a lascivious old man baffled and frustrated by women (see Example 5). Here the speaker identifies himself as Pasquarello, an emerging vecchio mask of Neapolitan origin, 36 whose stage personality was similar to that of Pantalone, the senile Venetian merchant that Lasso portrayed in a comedy staged in 1568 for the Bavarian court. Pasquarello’s language is inherently theatrical and obviously contrived to be completed by correlative gestures, both mimetic and musical. At the beginning of each stanza he greets an attractive signora with a rhythmically animated tune that rises sequentially, then slows as it sinks to the cadence. The shaping of the phrase allows the singer to express with his face or hands the desire that devours Pasquarello and even to bow down in an exaggerated manner – assuming that the villanella was rendered soloistically with lute accompaniment, a common practice. The tune reaches its highest peak in the recurrent refrain and then descends in urgent leaps as Pasquarello begs in vain for the signora’s hand, again suggesting performative gestures. It is not clear if the signora is a lady of doubtful reputation or an aristocrat obliged to maintain a haughty demeanor. Nonetheless, her silent disdain invites the singer to put his hands, head, and eyes into motion to amplify Pasquarello’s frustrated desire for the audience. Emerging dell’arte masks were introduced to Rome at mid-century by itinerant comedians from the Veneto, offering Lasso the opportunity to observe the antics of Pantalone and his servant Zanni, also known for singing canzoni to lute accompaniment. 37 33 A. DE JORIO, Gesture in Naples and Gesture in Classical Antiquity, trans. A. KENDON, Bloomington, 2000. 34 Quoted in P. WELLER, Lasso, Man of the Theatre, in I. BOSSUYT, E. SCHREURS and A. WOUTERS eds., Orlandus Lassus and His Time, (Yearbook of the Alamire Foundation, 1), Peer, 1995, p. 90. 35 For an edition of this villanella, see CARDAMONE, The Salon as Marketplace, pp. 72–74. It proved to be the most popular villanella in Dorico’s anthology, having been arranged by six composers (see Table 2). 36 A. NICOLL, Masks Mimes and Miracles. Studies in the Popular Theatre, New York, 1963, p. 260. 37 F. CRUCIANI, Teatro nel rinascimento. Roma 1450–1550, Rome, 1983, pp. 623–627.

(1) Bona sera como stai core mio bello? Dal’autro giorno non t’aggio veduta. Io t’aggio conosciuto da lontano, Adio signora toccami la mano. (2) Bona sera non conosci Pasquarello? Fami carisse et non star come muta. Io t’aggio conosciuto da lontano, Adio signora toccami la mano. (3) Bona sera io conosco ch’ai martiello, Tu non ci vedi et stai come storduta. Io t’aggio conosciuto da lontano, Adio signora toccami la mano. (4) Bona sera che lo mare è in fortuna, Haggio spigliat’a mal punto la luna. Io t’aggio conosciuto da lontano, Adio signora toccami la mano. ORLANDO DI LASSO ET AL.: A NEW READING OF THE ROMAN VILLANELLA BOOK (1555) Good evening, how are you my gentle heart? I haven’t seen you since the other day. I’ve known you from afar, farewell lady, take my hand. Good evening, don’t you know Pasquarello? Caress me and don’t be silent, I’ve known you from afar, farewell lady, take my hand. Good evening, I know that you’re tormented, you can’t see and you’re in a daze. I’ve known you from afar, farewell lady, take my hand. Good evening, since the sea is stormy, I’ve thrown the moon into an adverse phase. I’ve known you from afar, farewell lady, take my hand. Example 5. Bona sera como stai core mio bello, Cantus, 1555 30 ; Tenor, 1558 16 . 143

- Page 90 and 91: 92 LUMINITA FLOREA The pictor of Ca

- Page 92 and 93: 94 LUMINITA FLOREA open buds comfor

- Page 95 and 96: UT HEC TE FIGURA DOCET: THE TRANSFO

- Page 97 and 98: THE TRANSFORMATION OF MUSIC THEORY

- Page 99 and 100: THE TRANSFORMATION OF MUSIC THEORY

- Page 101 and 102: THE TRANSFORMATION OF MUSIC THEORY

- Page 103 and 104: THE TRANSFORMATION OF MUSIC THEORY

- Page 105 and 106: THE TRANSFORMATION OF MUSIC THEORY

- Page 107 and 108: THE TRANSFORMATION OF MUSIC THEORY

- Page 109 and 110: CHANGE AND CONTINUITY IN TWENTIETH-

- Page 111 and 112: CHANGE AND CONTINUITY IN TWENTIETH-

- Page 113 and 114: CHANGE AND CONTINUITY IN TWENTIETH-

- Page 115 and 116: CHANGE AND CONTINUITY IN TWENTIETH-

- Page 117 and 118: CHANGE AND CONTINUITY IN TWENTIETH-

- Page 119 and 120: CHANGE AND CONTINUITY IN TWENTIETH-

- Page 121 and 122: CHANGE AND CONTINUITY IN TWENTIETH-

- Page 123 and 124: ORLANDO DI LASSO ET AL.: ANEW READI

- Page 125 and 126: ORLANDO DI LASSO ET AL.: A NEW READ

- Page 127 and 128: ORLANDO DI LASSO ET AL.: A NEW READ

- Page 129 and 130: ORLANDO DI LASSO ET AL.: A NEW READ

- Page 131 and 132: (1) Son morto e moro e pur cerco mo

- Page 133 and 134: ORLANDO DI LASSO ET AL.: A NEW READ

- Page 135 and 136: ORLANDO DI LASSO ET AL.: A NEW READ

- Page 137 and 138: ORLANDO DI LASSO ET AL.: A NEW READ

- Page 139: (1) Latra traitora tu mi fai morire

- Page 143 and 144: ORLANDO DI LASSO ET AL.: A NEW READ

- Page 145 and 146: THE TWO EDITIONS OF LASSO’S SELEC

- Page 147 and 148: THE TWO EDITIONS OF LASSO’S SELEC

- Page 149 and 150: THE TWO EDITIONS OF LASSO’S SELEC

- Page 151 and 152: THE TWO EDITIONS OF LASSO’S SELEC

- Page 153 and 154: THE TWO EDITIONS OF LASSO’S SELEC

- Page 155: THE TWO EDITIONS OF LASSO’S SELEC

- Page 158 and 159: 160 RICHARD FREEDMAN Lasso’s chan

- Page 160 and 161: 162 RICHARD FREEDMAN prints, but by

- Page 162 and 163: 164 RICHARD FREEDMAN It seems likel

- Page 164 and 165: 166 RICHARD FREEDMAN II, who ruled

- Page 166 and 167: 168 RICHARD FREEDMAN Authorial cont

- Page 168 and 169: 170 RICHARD FREEDMAN APPENDIX Docum

- Page 170 and 171: 172 RICHARD FREEDMAN Royaume que bo

- Page 172 and 173: 174 RICHARD FREEDMAN machen unnd ei

- Page 174 and 175: 176 RICHARD FREEDMAN prejudice both

- Page 176 and 177: 178 BERNHOLD SCHMID Lassos vierundz

- Page 178 and 179: 180 BERNHOLD SCHMID cepta (quae nec

- Page 180 and 181: 182 BERNHOLD SCHMID sei senza parol

- Page 182 and 183: 184 BERNHOLD SCHMID Beispiel 1a: Ko

- Page 184 and 185: 186 BERNHOLD SCHMID Beispiel 3a: Nu

- Page 186 and 187: 188 BERNHOLD SCHMID Beispiel 5: Num

- Page 188 and 189: 190 BERNHOLD SCHMID Beispiel 6: Num

142 DONNA G. CARDAMONE JACKSON<br />

The texts of villanelle given to Lasso are all characterized by rhetorical tendencies<br />

to amplification and metaphor, a kind of discourse that invites the expressive hand<br />

gestures traditionally associated with Neapolitans. 33 That Lasso was capable of creating<br />

poems calling for semantic completion through visible bodily action is implied<br />

in a letter he wrote to Wilhelm of Bavaria in 1574, describing how he entertained his<br />

companions on a journey to Italy: ‘I have been reciting jokes, proverbs, and strambotti<br />

with lots of farcical and bawdy humor’. 34 Clearly by this time he had built up<br />

the same stock of gestural materials that villanella poets habitually exploited for comical<br />

effects. Lasso’s predilection for ribald gestic humor finds a parallel in no. 15,<br />

wherein sexually suggestive descriptions of playing instruments are juxtaposed with<br />

droll punning on solmization syllables that signify love-making. 35<br />

No. 18 is a pertinent example of how Lasso might load his memory with matter<br />

relevant to his favorite dell’arte character – a lascivious old man baffled and frustrated<br />

by women (see Example 5). Here the speaker identifies himself as Pasquarello,<br />

an emerging vecchio mask of Neapolitan origin, 36 whose stage personality was similar<br />

to that of Pantalone, the senile Venetian merchant that Lasso portrayed in a comedy<br />

staged in 1568 for the Bavarian court. Pasquarello’s language is inherently theatrical<br />

and obviously contrived to be completed by correlative gestures, both mimetic and<br />

musical. At the beginning of each stanza he greets an attractive signora with a rhythmically<br />

animated tune that rises sequentially, then slows as it sinks to the cadence.<br />

The shaping of the phrase allows the singer to express with his face or hands the<br />

desire that devours Pasquarello and even to bow down in an exaggerated manner –<br />

assuming that the villanella was rendered soloistically with lute accompaniment, a<br />

common practice. The tune reaches its highest peak in the recurrent refrain and then<br />

descends in urgent leaps as Pasquarello begs in vain for the signora’s hand, again<br />

suggesting performative gestures. It is not clear if the signora is a lady of doubtful<br />

reputation or an aristocrat obliged to maintain a haughty demeanor. Nonetheless, her<br />

silent disdain invites the singer to put his hands, head, and eyes into motion to amplify<br />

Pasquarello’s frustrated desire for the audience.<br />

Emerging dell’arte masks were introduced to Rome at mid-century by itinerant comedians<br />

from the Veneto, offering Lasso the opportunity to observe the antics of Pantalone<br />

and his servant Zanni, also known for singing canzoni to lute accompaniment. 37<br />

33 A. DE JORIO, Gesture in Naples and Gesture in Classical Antiquity, trans. A. KENDON, Bloomington,<br />

2000.<br />

34 Quoted in P. WELLER, Lasso, Man of the Theatre, in I. BOSSUYT, E. SCHREURS and A. WOUTERS<br />

eds., Orlandus Lassus and His Time, (Yearbook of the Alamire Foundation, 1), Peer, 1995, p. 90.<br />

35 For an edition of this villanella, see CARDAMONE, The Salon as Marketplace, pp. 72–74. It proved<br />

to be the most popular villanella in Dorico’s anthology, having been arranged by six composers (see<br />

Table 2).<br />

36 A. NICOLL, Masks Mimes and Miracles. Studies in the Popular Theatre, New York, 1963, p. 260.<br />

37 F. CRUCIANI, Teatro nel rinascimento. Roma 1450–1550, Rome, 1983, pp. 623–627.