industrial court malaysia - Malaysian Legal and Tax Information Centre

industrial court malaysia - Malaysian Legal and Tax Information Centre industrial court malaysia - Malaysian Legal and Tax Information Centre

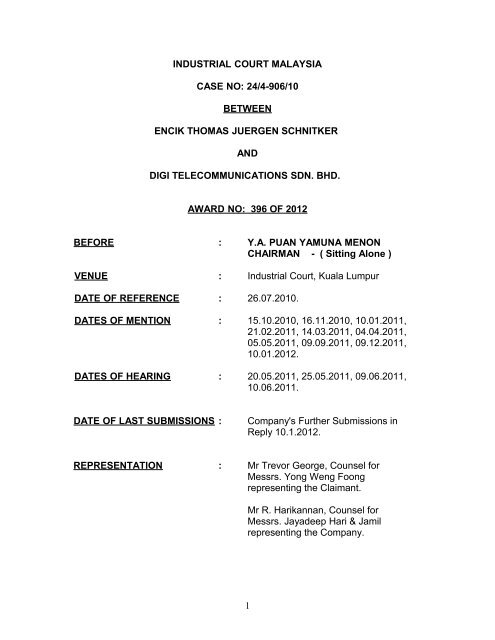

INDUSTRIAL COURT MALAYSIA CASE NO: 24/4-906/10 BETWEEN ENCIK THOMAS JUERGEN SCHNITKER AND DIGI TELECOMMUNICATIONS SDN. BHD. AWARD NO: 396 OF 2012 BEFORE : Y.A. PUAN YAMUNA MENON CHAIRMAN - ( Sitting Alone ) VENUE : Industrial Court, Kuala Lumpur DATE OF REFERENCE : 26.07.2010. DATES OF MENTION : 15.10.2010, 16.11.2010, 10.01.2011, 21.02.2011, 14.03.2011, 04.04.2011, 05.05.2011, 09.09.2011, 09.12.2011, 10.01.2012. DATES OF HEARING : 20.05.2011, 25.05.2011, 09.06.2011, 10.06.2011. DATE OF LAST SUBMISSIONS : Company's Further Submissions in Reply 10.1.2012. REPRESENTATION : Mr Trevor George, Counsel for Messrs. Yong Weng Foong representing the Claimant. Mr R. Harikannan, Counsel for Messrs. Jayadeep Hari & Jamil representing the Company. 1

- Page 2 and 3: REFERENCE: This is a reference made

- Page 4 and 5: 4.4.2008 (page 20-25, Exhibit 3 att

- Page 6 and 7: Our decision to terminate your cont

- Page 8 and 9: (a) That in order to safeguard a wo

- Page 10 and 11: Q : These 4 C's are part of the DMT

- Page 12 and 13: Second Issue: Whether the contract

- Page 14 and 15: It is after all a Reply. The Claima

- Page 16 and 17: years fixed term. It was submitted

- Page 18 and 19: In the case of Dr. A Dutt, the Cour

- Page 20 and 21: employee on the one hand, and inter

- Page 22 and 23: “It is clear therefore that in re

- Page 24 and 25: Fourth Issue: What would be the qua

- Page 26 and 27: views of his Lordship and also the

- Page 28: Remedy Having considered all the re

INDUSTRIAL COURT MALAYSIA<br />

CASE NO: 24/4-906/10<br />

BETWEEN<br />

ENCIK THOMAS JUERGEN SCHNITKER<br />

AND<br />

DIGI TELECOMMUNICATIONS SDN. BHD.<br />

AWARD NO: 396 OF 2012<br />

BEFORE : Y.A. PUAN YAMUNA MENON<br />

CHAIRMAN - ( Sitting Alone )<br />

VENUE : Industrial Court, Kuala Lumpur<br />

DATE OF REFERENCE : 26.07.2010.<br />

DATES OF MENTION : 15.10.2010, 16.11.2010, 10.01.2011,<br />

21.02.2011, 14.03.2011, 04.04.2011,<br />

05.05.2011, 09.09.2011, 09.12.2011,<br />

10.01.2012.<br />

DATES OF HEARING : 20.05.2011, 25.05.2011, 09.06.2011,<br />

10.06.2011.<br />

DATE OF LAST SUBMISSIONS : Company's Further Submissions in<br />

Reply 10.1.2012.<br />

REPRESENTATION : Mr Trevor George, Counsel for<br />

Messrs. Yong Weng Foong<br />

representing the Claimant.<br />

Mr R. Harikannan, Counsel for<br />

Messrs. Jayadeep Hari & Jamil<br />

representing the Company.<br />

1

REFERENCE:<br />

This is a reference made under Section 20(3) of the Industrial Relations Act,<br />

1967 pertaining to the dismissal of Encik Thomas Juergen Schnitker (the<br />

Claimant) by DIGI Telecommunications Sdn. Bhd (the Respondent).<br />

AWARD<br />

This is a reference made under Section 20(3) of the Industrial Relations Act,<br />

1967 pertaining to the dismissal of Mr Thomas Juergen Schnitker (the Claimant)<br />

by DIGI Telecommunications Sdn. Bhd (the Respondent or “the Company”).<br />

The Claimant's Last Drawn Salary was RM102,850.00 (See page 33 of<br />

Company's Bundle of Documents, COB1).<br />

The Issues<br />

The Issues in this case are as follows:<br />

First Issue: Whether the dismissal was with just cause <strong>and</strong> excuse.<br />

Second Issue: Whether the Claimant's contract of employment was a fixed term<br />

contract.<br />

Third Issue: If the dismissal was without just cause <strong>and</strong> excuse, whether the<br />

Claimant should be reinstated.<br />

Fourth Issue: What would be the quantum in terms of backwages.<br />

2

The Pleadings<br />

The Pleadings in this case comprised the following:<br />

a) Statement of Case dated 15.11.2010 (“SOC”);<br />

b) Statement in Reply dated 12.2.2011 (“SIR”);<br />

c) Rejoinder dated 14.3.2011 (“Rejoinder”).<br />

The Documents<br />

The Documents pertaining to this case were as follows:<br />

a) Claimant's Bundle of Documents-1 marked as “CLB-1”;<br />

b) Company's Bundle of Documents marked as “COB-1”;<br />

c) Company's Supplementary Bundle of Documents marked as “COB-2”.<br />

The Witnesses<br />

The Witnesses were:<br />

1. The Company's sole witness Mr. Chan Nam Kiong (COW1, Witness<br />

Statement dated 25.5.2011 marked as “COW-S1”);<br />

2. The Claimant was sole witness in his case (CLW1, Witness Statement<br />

dated 25.5.2011 marked as “CLW-S1”).<br />

Claimant's Case<br />

The Contract of Employment<br />

The Claimant was appointed as the Chief Commercial/Marketing Officer<br />

(CCO/CMO) of the Company by virtue of the Letter of Offer of Employment dated<br />

3

4.4.2008 (page 20-25, Exhibit 3 attached to SOC, see also COB1 p1-6). He<br />

commenced employment on 1.5.2008.<br />

The material express terms of employment are as expressed in the Offer of<br />

Employment which the Claimant signed <strong>and</strong> accepted on 7.4.2008. This<br />

document stipulates his basic monthly salary <strong>and</strong> contractual benefits as follows:-<br />

a) Performance bonus;<br />

b) Special Incentive;<br />

c) Housing;<br />

d) Company Car;<br />

e) Children Education Expenses;<br />

f) Home Leave;<br />

g) Club Membership;<br />

h) Relocation Expenses;<br />

i) Australian Medical Benefits for Wife; <strong>and</strong><br />

j) Employee Provident Fund (EPF).<br />

Claimant's Task<br />

It was submitted on behalf of the Claimant that he was given the mission, as<br />

one of the four (4) top Management Officers/Chiefs “to bring change to the<br />

Company owing to the insufficiencies it faced at the material time” (para 7 SOC<br />

<strong>and</strong> para 5 SIR, see also COB p7-8, ”Main objectives <strong>and</strong> responsibilities of the<br />

Claimant”, <strong>and</strong> Q & A 4 - 7, CLWS1).<br />

The mission entrusted to him by the Ex-Chief Executive Officer of the Company<br />

(“the Ex-CEO”) Johan Dennelind, is reflected in the Memo dated 16.4.2008 from<br />

4

Bjorn Magnus Kopperud to him (page 26, documents attached to the SOC) <strong>and</strong><br />

the Ex-CEO's Write-Up of his expectations (pages 27-29, documents attached to<br />

the SOC).<br />

The Claimant pointed out that throughout his tenure with the Company, he had<br />

achieved milestones for the Company (see paragraph 8, SOC <strong>and</strong> also<br />

Claimant's testimony Q&A 13, CLW-S1). In other words the Claimant's position<br />

was that he had contributed much to the Company <strong>and</strong> there certainly were no<br />

performance issues as claimed by the Company in the termination letter.<br />

The Termination<br />

The Claimant was h<strong>and</strong>ed a Letter of Termination of Contract dated 9.7.2009<br />

terminating his contract with immediate effect (pages 18-19, Exhibit 2, SOC, see<br />

also COB1 p31-32).<br />

The letter reads as follows:<br />

“Dear Tom,<br />

Termination of Contract<br />

Reference is made to the above matter. We wish to advise that we hereby<br />

exercise our right under the terms of your contract to terminate your services for<br />

cause. Accordingly we hereby pay you 3 months salary in lieu of 3 months<br />

notice.<br />

We wish to advise that we have made this decision after consulting with you <strong>and</strong><br />

after making reasonable efforts to establish a viable alternative course of action.<br />

However it is evident that these efforts which have been undertaken in good faith<br />

have proven to be abortive.<br />

5

Our decision to terminate your contract is premised on the following:-<br />

1. We have examined your performance in the position of Chief Commercial<br />

Officer <strong>and</strong> measured the same against the job size <strong>and</strong> deliverables. It is<br />

evident to us that either your performance does not meet the expectations<br />

of the Company in terms of the market position we seek or there is a need<br />

for us to review the viability of the said position <strong>and</strong> to approach the<br />

marketing requirements <strong>and</strong> solutions differently. The details of this have<br />

been discussed previously <strong>and</strong>/or are a matter of record.<br />

2. We have taken the above into account during the general review of the<br />

organizational structure. In line with the above we have decided to devolve<br />

the commercial <strong>and</strong> marketing functions. It is our view that these steps are<br />

necessary in order to provide a more effective marketing <strong>and</strong> commercial<br />

solution. It is clear to us that the current arrangements do not adequately<br />

meet the Company's requirements in a market environment that is only<br />

expected to become more <strong>and</strong> more challenging in the foreseeable future.<br />

3. As a result of this review we have decided to abolish the position of Chief<br />

Commercial Officer in its present form.<br />

4. We had attempted to explore alternative positions with you <strong>and</strong> this had<br />

been communicated previously with. It is evident that these have been<br />

rejected. We deny the suggestion that this was put to you out of the blue<br />

<strong>and</strong> we are unable to agree with your characterization of your performance<br />

which does not represent the true position. It is our position that you have<br />

been duly appraised of the unfolding events that have culminated in the<br />

above decision.<br />

6

We wish you well in your further undertakings. Kindly liaise with the Head of<br />

HRD to facilitate the h<strong>and</strong>over of company belongings <strong>and</strong> outst<strong>and</strong>ing<br />

assignments.<br />

Please be advised accordingly,<br />

Johan Dennelind<br />

CEO”<br />

The said letter stated the reasons for the termination as follows:-<br />

1. the Company's restructuring that led to the Claimant's position being<br />

abolished <strong>and</strong><br />

2. poor performance on the part of the Claimant.<br />

First Issue: whether the dismissal was with just cause <strong>and</strong> excuse<br />

The Law<br />

It is trite law that the Company does not have the right to terminate the services<br />

of the Claimant for no valid reason.<br />

In Tip Top Motorcade Sdn. Bhd. v. Johnny Chong Choong Keong (Award<br />

114 of 1994), the learned Chairman of the Industrial Court stated the basic<br />

principles as follows:-<br />

“The Industrial Court is obliged to act upon the evidence <strong>and</strong> on the basis of<br />

settled principles of <strong>industrial</strong> jurisprudence. In particular, it takes into account<br />

these well-established principles of <strong>industrial</strong> law:<br />

7

(a) That in order to safeguard a workman's security of tenure, a dismissal<br />

must be grounded on just cause or excuse (Dr. A. Dutt v Assunta<br />

Hospital [1981] 1 MLJ 304).<br />

(b) That there is no material difference between a termination <strong>and</strong> a dismissal.<br />

And further:<br />

The term employed in the act of bringing a workman's employment to an<br />

end is inconsequential; it is the Court's duty to determine whether that act,<br />

whatever the label attached to it, was for just cause or excuse.”<br />

“ (d) That the burden of proof of the facts which would constitute just<br />

cause or excuse is on the employer. The employer discharges his<br />

burden by adducing evidence either oral or documentary, to prove<br />

the facts which he alleges as constituting just cause or excuse.<br />

(e) That the Court's duty is to enquire whether the reason or excuse<br />

advanced by the employer has or has not been made out. If the Court<br />

finds as a fact that it has not been proven, then the inevitable conclusion<br />

must be that the termination or dismissal was without just cause or<br />

excuse.”<br />

Claimant's Arguments<br />

The Claimant submitted that the Company had terminated his employment<br />

simpliciter under the guise of poor performance <strong>and</strong> restructuring.<br />

The Claimant pointed out that after the fact of termination on 9.7.2009, the<br />

Company alleged other “grounds” for the Claimant's dismissal, such as,<br />

8

'misbehaviour', 'inappropriate behaviour', 'detrimental to ...reputation' <strong>and</strong>/or<br />

'abuse of trust <strong>and</strong> confidence' (paragraphs 15, 16, 17 <strong>and</strong> 23 of the SIR).<br />

It was submitted on behalf of the Claimant that at no time did these allegations<br />

feature as part of the Company's grounds for termination as stated in its<br />

Letter of Termination dated 9.7.2009 (page 18-19, Exhibit 2, SOC).<br />

Company Witness<br />

The CEO Johan Dennelind, who had issued the letter of termination did not come<br />

as a witness. Instead the Company relied solely on the evidence of the<br />

Claimant's subordinate Mr. Chan Nam Kiong (“COW-1”), the Company's sole<br />

witness who obviously had no personal knowledge pertaining to the Claimant's<br />

termination. As aptly pointed out by Claimant's Counsel, his evidence was purely<br />

based on his opinion <strong>and</strong>/or view.<br />

His evidence under cross examination was as follows:<br />

“Q : Prior to the Claimant's termination, you were not in the Digi<br />

A : Agree.<br />

Management Team?<br />

Q : In terms of the hierarchy, you have the following:<br />

CEO<br />

A : Yes.<br />

CTO (Chief Technology Officer)<br />

CFO (Chief Financial Officer)<br />

CMO/CCO (Chief Marketing Officer / Chief Commercial Officer)<br />

(Claimant)?<br />

9

Q : These 4 C's are part of the DMT?<br />

A : Yes.<br />

Q : But the rest of the DMT is not from the C's?<br />

A : That's right.<br />

Q : Before the Claimant was terminated, <strong>and</strong> you were not part of<br />

A : Yes.<br />

the DMT, Management decisions pertaining to the positions<br />

<strong>and</strong> the running of the Company would have been done by the<br />

DMT members?<br />

Q : You would not be able to give evidence on the policy decisions<br />

as considerations made by the Company pertaining to the<br />

Claimant's termination?<br />

A : I have no information on the decision.”<br />

It is evident from the above that COW1 had no personal knowledge pertaining to<br />

the decision to terminate the Claimant. COW1 agreed in cross examination that<br />

the Ex-CEO, Mr. Johan Dennelind was the one person who was in a position to<br />

throw some light on the decision to dismiss.<br />

COW1 testified as follows:<br />

“Q : Mr. Johan Dennelind was supposed to come but he is not coming?<br />

A : I was made aware that he can't come.”<br />

10

Decision on the First Issue<br />

The burden of proof is on the Company to prove that the dismissal of the<br />

employee is with just cause or excuse which the Company has failed to do<br />

in this case.<br />

As observed in the Tip Top Motorcade case, “the burden of proof of the facts<br />

which would constitute just cause or excuse is on the employer. The employer<br />

discharges his burden by adducing evidence either oral or documentary, to prove<br />

the facts which he alleges as constituting just cause or excuse”<br />

In our case the reasons given for the dismissal were that the Company's plans<br />

of restructuring had led to the Claimant's position being abolished <strong>and</strong> also poor<br />

performance on the part of the Claimant. The Company's sole witness, COW1,<br />

who acknowledged that the Claimant had been his boss, confirmed under oath<br />

that he had no personal knowledge or information pertaining to the reasons for<br />

the dismissal in question.<br />

The inevitable conclusion is that the dismissal of the Claimant was without just<br />

cause or excuse.<br />

The Court has carefully <strong>and</strong> meticulously considered <strong>and</strong> evaluated the totality of<br />

the evidence before it on a balance of probabilities, bearing in mind s 30(5) of the<br />

IR Act 1967. Having considered all the facts, the totality of the evidence both oral<br />

<strong>and</strong> documentary <strong>and</strong> the submissions, <strong>and</strong> being guided by the principles of<br />

equity <strong>and</strong> good conscience <strong>and</strong> the substantial merits of the case, without<br />

regard to technicalities <strong>and</strong> legal form, this Court finds that the dismissal of the<br />

Claimant in this case was without just cause <strong>and</strong> excuse.<br />

11

Second Issue: Whether the contract of employment is a fixed term contract<br />

The Pleading Issue<br />

Neither the Claimant nor the Company in this case pleaded the issue of fixed<br />

term contract in their respective pleadings.<br />

IN the case R. Rama Ch<strong>and</strong>ran v The Industrial Court Malaysia & Anor<br />

(1997) 1 MLJ 145, it was held that:<br />

“It is trite law that a party is bound by its pleadings. The Industrial Court must<br />

scrutinize the pleadings <strong>and</strong> identify the issues, take evidence, hear the<br />

parties' arguments <strong>and</strong> finally pronounce its judgment having strict regards to<br />

the issues.”<br />

The Company submitted that it was the Claimant's burden to plead (<strong>and</strong><br />

prove) that his contract was permanent <strong>and</strong> not a genuine fixed-term<br />

contract.<br />

It was argued on behalf of the Company that the Claimant had failed to plead<br />

that he was not on a fixed term contract <strong>and</strong> that instead his employment was on<br />

a permanent basis.<br />

The case of Pernas OUE (KL) Sdn Bhd v Choi Wai Ki [1997] 2 ILR 439 was<br />

referred to, where the Court held:-<br />

“Furthermore the Court agrees with the Company that the contention of the<br />

Claimant that he was on a permanent contract was not pleaded.<br />

12

It was argued on behalf of the Claimant as follows:<br />

It was pointed out on behalf of the Claimant that the issue here is as to who is<br />

relying on the fixed term employment contract. It was argued that the Claimant<br />

is not relying on it but the Company is, especially to pre-empt any issue of<br />

reinstatement.<br />

It was submitted further that as the primary remedy under s.20 IRA 1067 is<br />

reinstatement, it must follow that it is for the Company to plead, or lead evidence<br />

on it being a fixed-term.<br />

The Claimant also submitted that it is trite law that he who asserts must prove<br />

(S.101&102 evidence Act 1950).<br />

Hence it was submitted that as it is the Company that is alleging the fixed term, it<br />

is incumbent on them to plead, <strong>and</strong> prove.<br />

The Court's View<br />

The Court is of the view that the failure to plead this issue as a specific item is<br />

not fatal in this case. Although it would have been far better for this fact to have<br />

been addressed specifically by the Claimant in the SOC <strong>and</strong> then responded to<br />

in reply in the SIR by the Company, the failure to plead this is not fatal. It must<br />

not be forgotten that the Claimant's claim seeks for reinstatement as a remedy,<br />

<strong>and</strong> in lieu of it, compensation. The facts (whatever facts are available) are<br />

before this Court to decide.<br />

Furthermore the Company in its Statement in Reply would normally address<br />

issues raised by the Claimant in the Statement of Case (SOC).<br />

13

It is after all a Reply. The Claimant failed to plead in the SOC the issue that his<br />

was not a genuine fixed term contract <strong>and</strong> the Company did not address this<br />

issue in the SIR. Such failure in this case is not fatal to either party.<br />

The Han Chiang Principle<br />

In M Vasagam a/l Muthusamy v Kesatuan Pekerja-Pekerja Resort World,<br />

Pahang & Anor [2003] 5 MLJ 262. the Industrial Court dealt with the issue of<br />

whether the contract of employment was a genuine fixed term contract. The<br />

applicant in that case relied on the case of Han Chiang School, Penang Han<br />

ChiangAssociated Chinese Scholls Association v National Union of<br />

Teachers in independent Schools, W Malaysia [1988] 1 ILR 611 (“the Han<br />

Chiang case”). In the Han Chiang case the Industrial Court held that the system<br />

of fixed term contracts in the school was employed as a means of control of the<br />

teachers concerned. The intention of the school was to rid itself of the union,<br />

Hence the school relied on the fixed term contracts to get rid of the teachers who<br />

were members of the union. The Court held on the facts that the contracts of<br />

employment were not genuine fixed term contracts. In this case some of the<br />

teachers had taught at the school for more than 20 years <strong>and</strong> “had their<br />

contracts renewed unfailingly during those years without the need to<br />

reapply whenever their fixed term contracts expired. The teachers<br />

therefore claimed that they had the right to automatic renewals of their<br />

contracts upon their expiry because all along that had been the practice of<br />

the school in the past”.<br />

14

The principle in Han Chiang appears to be that there must be clear facts to<br />

establish permanency of employment <strong>and</strong> to rebut the outward appearance of<br />

the fixed term nature of the contract. The Han Chiang situation is the exception<br />

to the rule.<br />

The Han Chiang case was distinguished in M Vasagam case. The Industrial<br />

Court in M Vasagam case upon examining the facts of the case found that<br />

there was a genuine fixed term contract.<br />

Fixed Term -The Arguments<br />

Burden of Proof<br />

The Company submitted that it was the Claimant's burden to prove that his<br />

contract was permanent <strong>and</strong> not a genuine fixed-term contract.<br />

The Claimant submitted that the burden was on the Company to adduce<br />

evidence to show that it was a genuine fixed-term contract.<br />

The Court is of the view that it is the duty of the Court to ascertain from the<br />

facts before it whether the case comes within the exceptional situation as<br />

in Han Chiang case. There must be clear facts to establish permanency of<br />

employment <strong>and</strong> to rebut the outward appearance of the fixed term<br />

nature of the contract.<br />

The Claimant's Arguments<br />

It was submitted on behalf of the Claimant that it was not the intention of the<br />

parties that the Claimant's employment with the Company was to be only for a 2<br />

15

years fixed term. It was submitted that although the Claimant's contract was<br />

stipulated to be for 2 years, it was a permanent contract in disguise. According to<br />

the Claimant he was assured by the Company's HR Head, <strong>and</strong> the Ex-CEO of<br />

this .<br />

The Claimant also pointed out that he was “head-hunted” from his previous<br />

position in Maxis to join the Company (Q&A 4, CLWS-1) to bring change.<br />

According to the Claimant he was even promised the possibility of being CEO<br />

after a stint as CMO. The Memo dated 16.4.2008 from Bjorn Kopperud (p.26,<br />

Exh 4, SOC) was referred to where it was stated “As CMO in Digi Tom will be<br />

part of the yearly processes. If his performance <strong>and</strong> potential proves good<br />

Telenor has the intention to find other challenges/roles for Tom in<br />

accordance with his ambitions <strong>and</strong> preferences <strong>and</strong> Telenor needs”.<br />

The Court noted that there were several contingencies. It was not a sure<br />

thing both ways, meaning for the employer <strong>and</strong> the employee.<br />

The Court finds that the above statements are not sufficient to establish that the<br />

parties had really intended permanency in the employment relationship. These<br />

matters are not sufficient to prove that it was not a genuine fixed term contract.<br />

The Decision on the Second Issue<br />

Whether the Claimant's contract of employment was a fixed term contract:<br />

The Court finds that in this case, based on the facts, it was a genuine fixed term<br />

contract .<br />

16

Third Issue: If the dismissal was without just cause <strong>and</strong> excuse, whether<br />

the Claimant should be reinstated<br />

Reinstatement -The <strong>Legal</strong> Principles<br />

1. Claimant being a foreigner is not a bar to reinstatement. This was made<br />

clear by the Federal Court in Assunta Hospital v Dr. A.Dutt (1981) 1 MLJ<br />

105 [TAB B of Claimant's Additional Bundle of Authorities], where the Court<br />

held that:<br />

“As for the non-citizens status of Dr. Dutt, we share the astonishment of<br />

the judge at the relevance of this point. Our views can be stated shortly,<br />

whether Dr. Dutt can get an extension of his visit-pass so as to be able to<br />

say in this country or the issue of a work-permit in order to be able to take<br />

up the appointment are not matters that can influence the Court in proper<br />

exercise of the jurisdiction conferred on it by the minister's reference of<br />

the representations for reinstatement. If an order is made ordering<br />

reinstatement <strong>and</strong> the workman is unable to obtain either the visit-pass or<br />

the work permit, the employer would not be in contempt of the order. It is<br />

for the workman to make the order effective. All that the hospital had to<br />

do is to make the post available to the workman. As for any suggestion<br />

that the order for reinstatement would influence the ministry of Home<br />

Affairs to issue the visit-pass or the work permit, there cannot be any truth<br />

in it, <strong>and</strong> it cannot possibly be said that the ministry of Home Affairs is<br />

bound to comply with the order for instatement. In any event, it is of no<br />

concern to the hospital.”<br />

17

In the case of Dr. A Dutt, the Court weighed the evidence carefully <strong>and</strong> ordered<br />

for the Claimant to be reinstated.<br />

In Microsoft Malaysia Sdn Bhd v Michael Brian Davis [2002] 2 ILR 453 it was<br />

held:<br />

“The Industrial Court has jurisdiction to order reinstatement to a foreigner if at the<br />

end of the day, the <strong>court</strong> comes to the finding that his dismissal is without just<br />

cause <strong>and</strong> excuse. Section 20 of the Industrial Relations Act 1967 applies to all<br />

workers be they <strong>Malaysian</strong>s or foreigners”.<br />

Reinstatement is intended to restore the status quo prior to dismissal (See<br />

Kumpulan Jerai Sdn. Bhd., Rengam v. National Union of Plantation<br />

Workers & Anor [1993] 3 MLJ 221, 238 <strong>and</strong> also Harris Solid State (M) Sdn.<br />

Bhd. & Ors. v. Bruno Gentil Pereire & 21 Ors. [1996] 4 CLJ 747).<br />

It is trite law that reinstatement is the primary remedy for unjustified dismissal.<br />

In Kumpulan Peransang Selangor Bhd. v. Zaid bin Haji Mohd Noh [1997] 1<br />

AMR 1008 at (page 1033) the Federal Court referred to Malhotra's “The Law of<br />

Industrial Disputes, Fourth edition, Volume 2 page 942 (to be referred to as<br />

Malhotra) where it was stated:-<br />

“In each case, keeping the objectives of <strong>industrial</strong> adjudication in mind, <strong>and</strong> in a<br />

spirit of fairness <strong>and</strong> justice, the Tribunal has to deal with the question, whether<br />

the circumstances of the case require that an exception should be made <strong>and</strong><br />

compensation would meet the ends of justice. If, on taking these principles <strong>and</strong><br />

18

the relevant factors into consideration, the Tribunal comes to the conclusion that<br />

reinstatement would not be desirable or expedient in the circumstances of the<br />

case, it may Award compensation instead of reinstatement to the workman in<br />

spite of the fact that his discharge or dismissal was invalid owing to some<br />

infirmity in the impugned order”.<br />

In Fung Keong Rubber Manufacturing (M) Sdn. Bhd. v. Lee Eng Kiat & Ors<br />

[1981] 1 MLJ 238, the Federal Court observed:<br />

“Reinstatement, a statutorily recognized form of specific performance, has<br />

become a normal remedy <strong>and</strong> this coupled with a full refund of his wages could<br />

certainly far exceed the meagre damages normally granted at common law. The<br />

speedy <strong>and</strong> effective resolution of disputes or differences is clearly seen to be in<br />

the national interest, but it is also apparent that any attempt to impose a legal<br />

obligation without a prior exploration for a voluntary conciliation could aggravate<br />

rather than solve the problem. To this end the Director General is empowered by<br />

section 20 of the Act to offer assistance to the parties to the dispute to expedite a<br />

settlement by means of conciliatory meetings”.<br />

Reading Malhotra further at page 941, the following passage states the matter<br />

clearly:-<br />

“No hard <strong>and</strong> fast rule can however be laid down for the exercise of the discretion<br />

of the Tribunal, as in each case, it must, in a spirit of fairness <strong>and</strong> justice in<br />

keeping with the objective of <strong>industrial</strong> adjudication, decide whether it should, in<br />

the interest of justice, depart from the general rule. Fair play towards the<br />

19

employee on the one h<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> interest of the employer including the<br />

consideration of discipline in the establishment, on the other, require to be duly<br />

safeguarded. This is necessary in the interest of both security of tenure of the<br />

employee <strong>and</strong> smooth <strong>and</strong> harmonious working of the establishment. Legitimate<br />

interest of both of them have to be kept in view, if the order is expected to<br />

promote the desired objectives of <strong>industrial</strong> peace <strong>and</strong> maximum possible<br />

production. Proper balance has to be maintained between the conflicting claims<br />

of the employer <strong>and</strong> the employee without jeopardising the larger interests of<br />

<strong>industrial</strong> peace <strong>and</strong> progress”.<br />

The Court at this juncture would like to reiterate what it observed in the case of<br />

Teh Cheng Hock v Lilly Industries Sdn Bhd, Award 209 of 2010, that in<br />

making its decision “the Court has to bear in mind the need to maintain this<br />

proper balance between the conflicting claims. The reality of the present day<br />

situation is that whilst it is true that it was intended that the primary remedy for<br />

unjust dismissal is reinstatement, it cannot be denied that the reality is that it is<br />

no longer the usual remedy”.<br />

In the oft quoted case of Nestle Food Storage (Sabah) Sdn. Bhd. v. Terrence<br />

Tan Nyang Yin [2002] 1 ILR page 283 (Nestle case) the Industrial Court (Y.A.<br />

Lim Heng Seng, since retired) made a pertinent observation that reinstatement<br />

though being the primary remedy under the law, was no longer the usual remedy<br />

<strong>and</strong> that there were valid reasons for this. Making reference to the Court of<br />

Appeal decision of Koperasi Serbaguna (quoted above) in which the Court of<br />

20

Appeal had observed that in <strong>industrial</strong> jurisprudence, reinstatement is the usual<br />

or primary remedy, Y.A. Lim Heng Seng (at that time) made the observation that<br />

the principle that reinstatement is the primary remedy must “be seen in the<br />

context of the statutory emphasis on expedition in the conciliation process <strong>and</strong><br />

the stipulation of the statutory aspiration for the conclusion of the adjudication<br />

without delays <strong>and</strong> where practicable within 30 days of the reference to the<br />

Court. It cannot be gainsaid that Parliament did not contemplate that the whole<br />

process will take too much time, <strong>and</strong> that hence the expediency of the remedy of<br />

reinstatement would not be negated by long delays in the dispute resolution<br />

processes provided by the Act”.<br />

He went on to observe that “in practice, reinstatement in <strong>industrial</strong> adjudication is<br />

no longer the normal, or the usual <strong>and</strong> the general remedy regularly granted by<br />

the Court”.<br />

Hence in making its decision the Court has to bear in mind the need to maintain<br />

this proper balance between the conflicting claims.<br />

The reality of the present day situation is that whilst the primary remedy for<br />

unjust dismissal is reinstatement, it cannot be denied that it is no longer<br />

the usual remedy.<br />

As observed by this Court in the case of Teh Cheng Hock v Lilly Industries<br />

Sdn Bhd, Award 209 of 2010:<br />

21

“It is clear therefore that in reality reinstatement is not readily granted for various<br />

reasons. It is granted only in fit <strong>and</strong> proper cases. In deciding this issue, there is<br />

no hard <strong>and</strong> fast rule of universal application. In each case, keeping the<br />

objectives of <strong>industrial</strong> adjudication in mind, <strong>and</strong> in a spirit of fairness <strong>and</strong> justice,<br />

bearing in mind that a proper balance between the conflicting claims of employee<br />

<strong>and</strong> employer needs to be maintained, the Industrial Court should decide as to<br />

the appropriate remedy to be granted in each case”.<br />

The Company in its Submissions in Reply dated 10 January 2012 stated<br />

that reinstatement was not appropriate for several reasons including the<br />

fact that the Claimant's position prior to his termination was a very senior<br />

position as the Chief Commercial/Marketing Officer (CCO/CMO) of the<br />

Company.<br />

In cases where reinstatement was not granted, among the factors taken<br />

into account was the fact that the Claimant was in a high ranking or<br />

managerial position:-<br />

In Jutajaya Holding Bhd v. Lim Poh Sim Award 397 of 2007 for instance, the<br />

Chairman of the Industrial Court at that time, Y.A. Puan Amelia Tee (presently in<br />

the High Court), stated the following:-<br />

“The Court has carefully considered the question of whether reinstatement would<br />

be the correct remedy in this case. It must be borne in mind that at the time of<br />

her dismissal, the Claimant was the CEO of the Company. It need not be<br />

22

gainsaid that this is a very senior position”. The above statement underlines the<br />

fact that the position of the Claimant in a management position or senior position<br />

is an important <strong>and</strong> relevant consideration.<br />

In Gold Coin Specialities Sdn. Bhd. v. Matheswaran a/l Paspanathan [2004]<br />

3 MLJ, the High Court (on judicial review), observed that the Claimant's position<br />

was a high ranking one. It also noted that the post he had earlier held in the<br />

Company had been filled up as the Company could not be expected to keep the<br />

position vacant for a long period as it would be detrimental to the Company's<br />

operation. The High Court also observed that the Claimant was relatively young<br />

<strong>and</strong> able. These were all relevant factors to be taken into account in considering<br />

whether to grant reinstatement in any particular case.<br />

Decision On The Issue of Reinstatement<br />

This Court finds that in our case reinstatement is clearly not the appropriate<br />

remedy. The Court has considered all the relevant factors, including the<br />

Claimant's length of service in the Company, his position being a top position,<br />

the intervening period after the dismissal etc. Bearing in mind the objectives of<br />

<strong>industrial</strong> adjudication <strong>and</strong> the competing claims of employer <strong>and</strong> employee, <strong>and</strong><br />

the need to maintain the proper balance, in the spirit of fairness <strong>and</strong> justice,<br />

bearing in mind s.30(5) of the IRA, this Court is of the considered view that<br />

reinstatement is not the appropriate remedy in this case.<br />

23

Fourth Issue: What would be the quantum in terms of backwages.<br />

Remedy: The Practice<br />

In the Industrial Court case of Coca-cola Far East Limited (<strong>Malaysian</strong> Branch)<br />

v. Warren J Carey [2006] 4 ILR p 2399, the Industrial Court Chairman, Y.A.<br />

Tuan Franklin Goonting (since retired), observed:-<br />

“...it has been the normal practice of the <strong>court</strong>, where reinstatement is not<br />

ordered, to award backwages limited to twenty-four months <strong>and</strong> compensation in<br />

lieu of reinstatement at the rate of one month's salary for each completed year of<br />

service.”<br />

In that case the Claimant who was an expatriate, had sought compensation<br />

based on various contractual terms. The learned Chairman made the following<br />

pertinent observations:<br />

“In seeking the other items of relief the Claimant is in fact asking the <strong>court</strong><br />

to enforce contractual terms <strong>and</strong> conditions <strong>and</strong> to assess loss of income<br />

or damages, something within the province of the civil <strong>court</strong>s.<br />

The learned Chairman went on to say:<br />

“If all these other remedies sought by the Claimant were granted by this Court<br />

the effect would be to convert the Industrial Court into a civil <strong>court</strong> <strong>and</strong> the word<br />

“reinstatement” inserted into the statement of case would be reduced to a mere<br />

password to gain entry to the IRA system <strong>and</strong> thereafter seek civil remedies.”<br />

The above observation is clearly a pertinent one. This Court is in full<br />

agreement.<br />

24

In Robert John Reeves v Southern Bank Bank Berhad [2010 2 LNS 1608]<br />

the Industrial Court held that “the <strong>court</strong> states that it does not think that it is<br />

proper that the Claimant should be allowed his prayer for all other contractual<br />

benefits that was accorded to him in the form of housing allowances,<br />

performance based rewards <strong>and</strong> other benefits as claimed pursuant to Clause<br />

28 of his statement of case'.<br />

Issue Of Bonus<br />

a) In the case of UMW Toyota (M) Sdn. Bhd. v. Chow Weng Thiem [1996]<br />

5 MLJ 678, the High Court held as follows:<br />

“A bonus is a gift or gratuity as a gesture of goodwill, <strong>and</strong> not<br />

enforceable, or it may be something which an employee is entitled to on<br />

the happening of a condition precedent <strong>and</strong> is enforceable when the<br />

condition is fulfilled. But in both cases it is something in addition to or in<br />

excess of that which is ordinarily received. Since bonus was a form of<br />

gratuitous payment of a discretionary nature, the respondent was not<br />

entitled to it as of right.”<br />

b) In the Industrial Court's case of Felda Palm Industries Sdn. Bhd. v.<br />

Mansor Pratiman [2006] 2 LNS 0948, the <strong>court</strong> followed <strong>and</strong> affirmed the<br />

above case of UMW Toyota (M) Sdn. Bhd.:<br />

'In the case of UMW Toyota (M) Sdn. Bhd. v. Chow Weng Thiem<br />

(1996) 5 MLJ 678. His Lordship Abdul Malik J. said, “In my judgment<br />

bonus was a form of gratuitous payment of a discretionary nature, the<br />

respondent was not entitled to it as of right”. This Court agrees with the<br />

25

views of his Lordship <strong>and</strong> also the contention of the Company's Counsel in<br />

that it is the prerogative of the Company to declare bonus for its workers<br />

or employees.'<br />

It was submitted that bonus was not a benefit which the Claimant was entitled to<br />

claim as of right. Bonus was discretionary <strong>and</strong> based upon the performance of<br />

the Company <strong>and</strong> the Claimant, <strong>and</strong> the Claimant was not entitled to bonus as of<br />

right.<br />

The Court agrees with Company's submissions that indeed bonus was<br />

discretionary <strong>and</strong> that the Claimant was not entitled to it as of right.<br />

Fixed Term<br />

The unexpired period of his fixed term contract.<br />

On the issue of backwages, the Company submitted a number of cases, all of<br />

which were fixed term contract cases. The Company submitted that any<br />

exposure would be the balance of the unexpired portion or balance of the<br />

contract period .<br />

a) In the case of Ranhill Worley Sdn Bjd. (formerly known as Jacobs<br />

Construction Management (M) Sdn Bhd.) v. Franz Jozef Marie<br />

Schefman & Anor [2008] 6 MLJ 823, the Court noted the following:<br />

“There is a consistent trend of cases which decided that an<br />

expatriate who had been unfairly dismissed was awarded backwages for<br />

the unexpired period of his fixed term contract. In the present case it<br />

26

was only reasonable that the first respondent be awarded backwages for<br />

the remainder of the unexpired term of his fixed term contract, which was<br />

what the chairman of the Industrial Court did.”<br />

b) In the case of Shapadu Energy & Engineering SB b. Stuart Ashley<br />

Eban [1999] MLJ 250, the High Court affirmed the decision of the<br />

Industrial Court as follows:<br />

“The Court holds that it is a breach of the Company to disallow the<br />

Claimant to work out of the unexpired duration of the twelve months fixed<br />

term contract.<br />

Therefore, the Claimant's remedy in this dispute is the<br />

unexpired period of his fixed term contract. There is no question of<br />

reinstatement. This Court will only make an order of compensation of loss<br />

of employment from the date of termination to the expiry date of the twelve<br />

months' contract.”<br />

The Company has submitted (paragraphs 48 to 57, Company's Submission) that<br />

the Claimant should only be awarded 10 months back-wages (i.e the balance of<br />

his unexpired contract period). Their reasoning is that it's fixed-term contract<br />

(Exh 3, SOC), which contract, on the face of it, stipulates “Your employment<br />

shall start on 1 May 2008 <strong>and</strong> shall be for a period of two (2) years from the<br />

start date”.<br />

Payment of 3 months salary<br />

When the Claimant's employment was terminated he was paid a payment of 3<br />

month's salary in lieu of 3 months notice, which will be deducted.<br />

27

Remedy<br />

Having considered all the relevant factors, this Court awards the following:-<br />

1. Backwages:<br />

RM 102,850.00 x 7 months - RM 719,950.00<br />

Deduction<br />

1% deduction for post dismissal earnings:<br />

1 x RM 719,950.00 - RM 7,199.50<br />

100<br />

The total sum to be paid is RM 719,950.00 – RM 7,199.50 = RM 712,750.50<br />

The total sum of RM 712,750.50 less any statutory deductions shall be paid to<br />

the Claimant through his solicitors within 30 days from the date of service of this<br />

Award.<br />

HANDED DOWN AND DATED THIS DAY 22 TH OF MARCH 2012<br />

sgd<br />

( YAMUNA MENON )<br />

CHAIRMAN<br />

INDUSTRIAL COURT, MALAYSIA<br />

KUALA LUMPUR<br />

28