TWICE THE SIZE - DIT Update - Dublin Institute of Technology

TWICE THE SIZE - DIT Update - Dublin Institute of Technology

TWICE THE SIZE - DIT Update - Dublin Institute of Technology

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

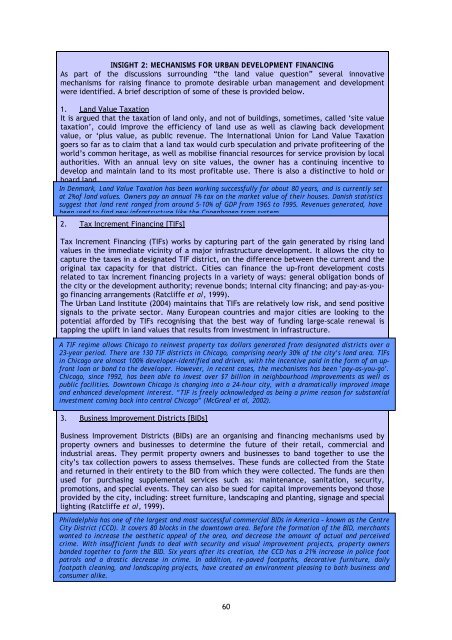

INSIGHT 2: MECHANISMS FOR URBAN DEVELOPMENT FINANCING<br />

As part <strong>of</strong> the discussions surrounding “the land value question” several innovative<br />

mechanisms for raising finance to promote desirable urban management and development<br />

were identified. A brief description <strong>of</strong> some <strong>of</strong> these is provided below.<br />

1. Land Value Taxation<br />

It is argued that the taxation <strong>of</strong> land only, and not <strong>of</strong> buildings, sometimes, called ‘site value<br />

taxation’, could improve the efficiency <strong>of</strong> land use as well as clawing back development<br />

value, or ‘plus value, as public revenue. The International Union for Land Value Taxation<br />

goers so far as to claim that a land tax would curb speculation and private pr<strong>of</strong>iteering <strong>of</strong> the<br />

world’s common heritage, as well as mobilise financial resources for service provision by local<br />

authorities. With an annual levy on site values, the owner has a continuing incentive to<br />

develop and maintain land to its most pr<strong>of</strong>itable use. There is also a distinctive to hold or<br />

hoard land.<br />

In Denmark, Land Value Taxation has been working successfully for about 80 years, and is currently set<br />

at 2%<strong>of</strong> land values. Owners pay an annual 1% tax on the market value <strong>of</strong> their houses. Danish statistics<br />

suggest that land rent ranged from around 5-10% <strong>of</strong> GDP from 1965 to 1995. Revenues generated, have<br />

been used to find new infrastructure like the Copenhagen tram system<br />

2. Tax Increment Financing [TIFs]<br />

Tax Increment Financing (TIFs) works by capturing part <strong>of</strong> the gain generated by rising land<br />

values in the immediate vicinity <strong>of</strong> a major infrastructure development. It allows the city to<br />

capture the taxes in a designated TIF district, on the difference between the current and the<br />

original tax capacity for that district. Cities can finance the up-front development costs<br />

related to tax increment financing projects in a variety <strong>of</strong> ways: general obligation bonds <strong>of</strong><br />

the city or the development authority; revenue bonds; internal city financing; and pay-as-yougo<br />

financing arrangements (Ratcliffe et al, 1999).<br />

The Urban Land <strong>Institute</strong> (2004) maintains that TIFs are relatively low risk, and send positive<br />

signals to the private sector. Many European countries and major cities are looking to the<br />

potential afforded by TIFs recognising that the best way <strong>of</strong> funding large-scale renewal is<br />

tapping the uplift in land values that results from investment in infrastructure.<br />

A TIF regime allows Chicago to reinvest property tax dollars generated from designated districts over a<br />

23-year period. There are 130 TIF districts in Chicago, comprising nearly 30% <strong>of</strong> the city’s land area. TIFs<br />

in Chicago are almost 100% developer-identified and driven, with the incentive paid in the form <strong>of</strong> an upfront<br />

loan or bond to the developer. However, in recent cases, the mechanisms has been ’pay-as-you-go’.<br />

Chicago, since 1992, has been able to invest over $7 billion in neighbourhood improvements as well as<br />

public facilities. Downtown Chicago is changing into a 24-hour city, with a dramatically improved image<br />

and enhanced development interest. “TIF is freely acknowledged as being a prime reason for substantial<br />

investment coming back into central Chicago” (McGreal et al, 2002).<br />

3. Business Improvement Districts [BIDs]<br />

Business Improvement Districts (BIDs) are an organising and financing mechanisms used by<br />

property owners and businesses to determine the future <strong>of</strong> their retail, commercial and<br />

industrial areas. They permit property owners and businesses to band together to use the<br />

city’s tax collection powers to assess themselves. These funds are collected from the State<br />

and returned in their entirety to the BID from which they were collected. The funds are then<br />

used for purchasing supplemental services such as: maintenance, sanitation, security,<br />

promotions, and special events. They can also be sued for capital improvements beyond those<br />

provided by the city, including: street furniture, landscaping and planting, signage and special<br />

lighting (Ratcliffe et al, 1999).<br />

Philadelphia has one <strong>of</strong> the largest and most successful commercial BIDs in America – known as the Centre<br />

City District (CCD). It covers 80 blocks in the downtown area. Before the formation <strong>of</strong> the BID, merchants<br />

wanted to increase the aesthetic appeal <strong>of</strong> the area, and decrease the amount <strong>of</strong> actual and perceived<br />

crime. With insufficient funds to deal with security and visual improvement projects, property owners<br />

banded together to form the BID. Six years after its creation, the CCD has a 21% increase in police foot<br />

patrols and a drastic decrease in crime. In addition, re-paved footpaths, decorative furniture, daily<br />

footpath cleaning, and landscaping projects, have created an environment pleasing to both business and<br />

consumer alike.<br />

60