Seizures in Young Dogs and Cats: Pathophysiology ... - VetLearn.com

Seizures in Young Dogs and Cats: Pathophysiology ... - VetLearn.com

Seizures in Young Dogs and Cats: Pathophysiology ... - VetLearn.com

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Article #4<br />

CE<br />

Send <strong>com</strong>ments/questions via email<br />

editor@CompendiumVet.<strong>com</strong><br />

or fax 800-556-3288.<br />

Visit CompendiumVet.<strong>com</strong> for<br />

full-text articles, CE test<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> CE<br />

test answers.<br />

<strong>Seizures</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Young</strong> <strong>Dogs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Cats</strong>:<br />

<strong>Pathophysiology</strong> <strong>and</strong> Diagnosis<br />

Joan R. Coates, DVM, MS, DACVIM (Neurology)<br />

University of Missouri, Columbia<br />

Robert L. Bergman, DVM, MS, DACVIM (Neurology)<br />

Carol<strong>in</strong>a Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Specialists<br />

Charlotte, North Carol<strong>in</strong>a<br />

ABSTRACT:<br />

<strong>Seizures</strong> <strong>in</strong> young dogs <strong>and</strong> cats have received little attention because of the ambiguous<br />

cl<strong>in</strong>ical nature of seizures. In human medic<strong>in</strong>e, certa<strong>in</strong> aspects of bra<strong>in</strong> development are<br />

now thought to have a role <strong>in</strong> childhood seizures. Epileptogenesis (i.e., generation of<br />

seizures) <strong>in</strong> an immature bra<strong>in</strong> is <strong>in</strong>fluenced by <strong>in</strong>hibitory <strong>and</strong> excitatory systems, ionic<br />

microenvironment, <strong>and</strong> degree of myel<strong>in</strong>ation. Develop<strong>in</strong>g neurons appear to be less vulnerable<br />

to damage <strong>and</strong> loss after seizure activity. <strong>Dogs</strong> <strong>and</strong> cats younger than 1 year of<br />

age are more likely to have symptomatic epilepsy. Early recognition of potential causes of<br />

seizures <strong>in</strong> young dogs <strong>and</strong> cats is important for appropriate diagnostic considerations<br />

<strong>and</strong> timely therapeutic <strong>in</strong>terventions.<br />

lthough the prevalence of seizures <strong>in</strong><br />

pediatric dogs <strong>and</strong> cats is unknown, the<br />

overall <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>in</strong> the pet population is<br />

reportedly 2% to 3%. 1,2 A<br />

<strong>Seizures</strong> <strong>in</strong> young dogs <strong>and</strong><br />

cats are a diagnostic dilemma for practitioners. In<br />

young animals, seizures usually signal the onset or<br />

coexistence of significant central nervous system<br />

(CNS) disease. A seizure <strong>in</strong> puppies <strong>and</strong> kittens<br />

often requires prompt medical attention with special<br />

considerations for medical management. For<br />

the purpose of this discussion, immature or young<br />

animals are def<strong>in</strong>ed as those younger than 6<br />

months of age. Categorically,<br />

the neonatal period is 0 to 2<br />

weeks of age, the socialization<br />

period is 3 to 12 weeks of age,<br />

<strong>and</strong> the juvenile period is 12<br />

weeks of age to adult (i.e., 3 to 6<br />

months of age). 3<br />

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY<br />

An immature bra<strong>in</strong> is more prone to seizures<br />

than is a mature bra<strong>in</strong> because of multiple<br />

changes that occur dur<strong>in</strong>g development.<br />

Epileptogenesis (i.e., generation of seizures) <strong>in</strong><br />

an immature bra<strong>in</strong> is <strong>in</strong>fluenced by the<br />

<strong>in</strong>hibitory <strong>and</strong> excitatory systems, ionic<br />

microenvironment, <strong>and</strong> degree of myel<strong>in</strong>ation.<br />

Much of the outl<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>formation on this has<br />

been extrapolated from laboratory animal<br />

model studies. 4 In immature animals, w<strong>in</strong>dows<br />

of either decreased or <strong>in</strong>creased susceptibility to<br />

seizures depend on the maturation of several<br />

factors with<strong>in</strong> the CNS. 5,6 Maturity of<br />

<strong>in</strong>hibitory systems is crucial for cessation of<br />

seizure activity <strong>in</strong> an immature bra<strong>in</strong>. γ-Am<strong>in</strong>o<br />

butyric acid (GABA) is the predom<strong>in</strong>ant<br />

<strong>in</strong>hibitory neurotransmitter <strong>in</strong> the bra<strong>in</strong>. The<br />

GABA receptor may select for chloride con-<br />

June 2005 447 COMPENDIUM

448 CE<br />

<strong>Seizures</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Young</strong> <strong>Dogs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Cats</strong>: <strong>Pathophysiology</strong> <strong>and</strong> Diagnosis<br />

ductance (GABA A) or potassium conductance<br />

(GABA B). 7 Ultrastructural studies <strong>com</strong>par<strong>in</strong>g immature<br />

with adult rat bra<strong>in</strong>s show that GABA term<strong>in</strong>als <strong>in</strong><br />

immature bra<strong>in</strong>s are smaller <strong>and</strong> conta<strong>in</strong> fewer synaptic<br />

vesicles. 8 Likewise, there are fewer synapses <strong>and</strong> lower<br />

concentrations of GABA receptors. 9,10 The rate of<br />

GABA formation <strong>and</strong> catabolism changes dur<strong>in</strong>g maturation.<br />

11–13 Differences lie not <strong>in</strong> receptor <strong>com</strong>position<br />

but rather <strong>in</strong> maturational changes to the chloride ion<br />

gradient that govern the equilibrium potential for<br />

GABA A channels. 14 Consequently, <strong>in</strong> the immature<br />

bra<strong>in</strong>, GABA A responses result <strong>in</strong> depolarization with<br />

subsequent activation of sodium ion (Na + ) <strong>and</strong> calcium<br />

ion (Ca +2 ) channels. 6<br />

In contrast to the <strong>in</strong>hibitory system, the excitatory<br />

system is overdeveloped. Glutamate is the major excitatory<br />

neurotransmitter <strong>in</strong> the bra<strong>in</strong>, <strong>and</strong> several subtypes<br />

for the glutamate receptor exist, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g N-methyl-Daspartate<br />

(NMDA), ka<strong>in</strong>ate, <strong>and</strong> α-am<strong>in</strong>o-3-hydroxy-5methyl-4-isoxazoleproprionate<br />

(AMPA). 15,16 The<br />

hippocampus of the prenatal bra<strong>in</strong> has an excess number<br />

of recurrent excitatory synapses <strong>and</strong> an overabundance<br />

of NMDA receptors. 17 As the bra<strong>in</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>ues to<br />

develop, these excitatory synapses are modulated or<br />

“pruned” to adult levels. Expression of glutamate transporters<br />

that play a role <strong>in</strong> glutamate uptake is also developmentally<br />

regulated. Decreased expression of<br />

glutamate transporters <strong>and</strong> variation of subtypes can<br />

lead to <strong>in</strong>creased seizure susceptibility <strong>and</strong> to a lower<br />

seizure threshold. 5,18<br />

Differences <strong>in</strong> the ionic microenvironment that surrounds<br />

neurons <strong>and</strong> glial cells also contribute to epileptogenicity<br />

of the immature bra<strong>in</strong>. The potassium<br />

concentration is <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong> the extracellular fluid of<br />

immature bra<strong>in</strong>s. 5 Glial function immaturity may allow<br />

the extracellular potassium concentration to <strong>in</strong>crease,<br />

caus<strong>in</strong>g excitability. 4 Thus the action potentials <strong>in</strong> immature<br />

neurons last longer because of altered potassium<br />

channel conductance, thereby caus<strong>in</strong>g a lower rest<strong>in</strong>g<br />

membrane potential <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased neuronal excitability. 19<br />

Catecholam<strong>in</strong>es, especially norep<strong>in</strong>ephr<strong>in</strong>e, play a role<br />

<strong>in</strong> the generalization of epileptic activity dur<strong>in</strong>g k<strong>in</strong>dl<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Lower levels of norep<strong>in</strong>ephr<strong>in</strong>e have been associ-<br />

ated with loss of k<strong>in</strong>dl<strong>in</strong>g antagonisms. 4 K<strong>in</strong>dl<strong>in</strong>g is<br />

def<strong>in</strong>ed as local, repeated, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>itially subconvulsive<br />

stimulation of neurons that progresses to alter the<br />

excitability of other nearby neurons <strong>and</strong> to develop <strong>in</strong>to<br />

a seizure focus. The threshold of k<strong>in</strong>dl<strong>in</strong>g varies with<br />

age, <strong>and</strong> spontaneous seizures occur more readily <strong>in</strong><br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g animals than <strong>in</strong> adults. 6 The lower ep<strong>in</strong>ephr<strong>in</strong>e<br />

level <strong>in</strong> the immature bra<strong>in</strong> may be a factor responsible<br />

for facilitat<strong>in</strong>g k<strong>in</strong>dl<strong>in</strong>g. 4<br />

In<strong>com</strong>plete myel<strong>in</strong>ation contributes to seizure expres-<br />

Developmental changes <strong>in</strong> the bra<strong>in</strong> may <strong>in</strong>crease or decrease<br />

the w<strong>in</strong>dow of susceptibility for seizures <strong>in</strong> young dogs <strong>and</strong> cats.<br />

sion <strong>in</strong> young animals. Myel<strong>in</strong>ation of the CNS beg<strong>in</strong>s<br />

<strong>in</strong> the last stage of gestation <strong>and</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>ues more rapidly<br />

after birth. It occurs first <strong>in</strong> phylogenetically older<br />

regions of the bra<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> bra<strong>in</strong> stem <strong>and</strong> later <strong>in</strong> the corpus<br />

callosum <strong>and</strong> neocortex. 20 It is speculated that this<br />

may have a role <strong>in</strong> poor <strong>in</strong>terhemispheric synchrony of<br />

seizure discharges. 4<br />

Can seizures cause bra<strong>in</strong> damage to the immature<br />

bra<strong>in</strong>? In humans, the neonatal CNS is particularly susceptible<br />

to seizures. 21 However, the immature nervous<br />

system is no more vulnerable <strong>and</strong> possibly more resistant<br />

to damage aris<strong>in</strong>g from seizures. 22 The immature bra<strong>in</strong><br />

undergo<strong>in</strong>g convulsive activity is capable of tak<strong>in</strong>g care<br />

of <strong>in</strong>creased energy requirements through acceleration<br />

of glycolytic flux, thus avoid<strong>in</strong>g major disruptions <strong>in</strong><br />

oxidative metabolism. 22 Cerebral high-energy phosphates<br />

(i.e., ATP <strong>and</strong> ADP) have been preserved <strong>in</strong><br />

puppies with seizures. 23 Nuclear magnetic resonance<br />

spectroscopy studies of the bra<strong>in</strong>s of puppies with<br />

seizures receiv<strong>in</strong>g supplemental oxygen have also shown<br />

sufficient preservation of energy balance even after prolonged<br />

status epilepticus. 24<br />

Develop<strong>in</strong>g neurons are less vulnerable to neuronal<br />

damage <strong>and</strong> cell loss. 6 Thus the immature bra<strong>in</strong> appears<br />

to be more resistant to the toxic effects of glutamate<br />

than does the mature bra<strong>in</strong>. 25 NMDA receptor expression<br />

<strong>in</strong> neonatal rat pups shows a decreased response to<br />

glutamate associated with differences <strong>in</strong> receptor subtypes,<br />

thus <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g that the degree of calcium entry<br />

<strong>in</strong>to the neurons is directly related to age. 26 This may be<br />

partly due to the lower density of active synapses, lower<br />

use of energy substrates, <strong>and</strong> immaturity of biochemical<br />

cascades that subsequently cause cell death. 26,27 How-<br />

COMPENDIUM June 2005

ever, there is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g evidence that recurrent seizures<br />

affect neuronal development by mechanisms that alter<br />

synaptogenesis <strong>and</strong> neurogenesis. 6,28<br />

The long-term effects of cont<strong>in</strong>ued seizure activity are<br />

unknown. Neonatal seizures can <strong>in</strong>crease the susceptibility<br />

of the develop<strong>in</strong>g bra<strong>in</strong> to subsequent seizure<strong>in</strong>duced<br />

<strong>in</strong>jury. 29,30 Experimental studies of immature<br />

rats showed that various pathologic changes developed<br />

after 50 short seizures. 31 Histopathologic studies of<br />

epileptic beagles have shown evidence of astrocytic<br />

swell<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> ischemic changes <strong>in</strong> cerebral cortical neurons.<br />

32 Magnetic resonance imag<strong>in</strong>g (MRI) of the bra<strong>in</strong><br />

has shown reduced myel<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong> children who have<br />

had neonatal convulsions. 21,33 However, a recent analysis<br />

of humans with recurrent seizures concluded that the<br />

risk to develop<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividuals was low. 34<br />

CLASSIFICATION<br />

Classify<strong>in</strong>g seizures is useful <strong>in</strong> identify<strong>in</strong>g the type<br />

<strong>and</strong> determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g an underly<strong>in</strong>g cause. In humans, controversy<br />

exists over def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g a solitary classification<br />

scheme for cl<strong>in</strong>ically describ<strong>in</strong>g seizures <strong>in</strong> neonates.<br />

The scheme used <strong>in</strong> adults established by the International<br />

League Aga<strong>in</strong>st Epilepsy 35 has been unreliable<br />

<strong>and</strong> difficult to apply to <strong>in</strong>fants. 36 Important differences<br />

exist <strong>in</strong> the cl<strong>in</strong>ical expression of seizures <strong>in</strong> adults <strong>and</strong><br />

neonates. 37 Adults more <strong>com</strong>monly present with partial<br />

seizures, whereas neonates have postural abnormalities.<br />

Neonatal seizures are often described as subtle <strong>and</strong> fragmentary,<br />

<strong>and</strong> some neonatal behaviors can mimic the<br />

phenomenology of true seizures. 38 These seizure-like<br />

behaviors have been referred to as reflex or release phe-<br />

nomena <strong>and</strong> must be dist<strong>in</strong>guished from true seizures.<br />

Neonatal seizures are currently classified us<strong>in</strong>g electroencephalography<br />

<strong>and</strong> simultaneous video monitor<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Neonatal seizures have been described as seizures with a<br />

close correlation to electroencephalogram (EEG)<br />

seizure discharges, seizures with an <strong>in</strong>consistent or no<br />

relationship to EEG ictal discharges, <strong>in</strong>fantile spasms,<br />

<strong>and</strong> EEG seizures without cl<strong>in</strong>ical seizures. 39 This has<br />

led to classification of epileptic <strong>and</strong> nonepileptic neona-<br />

<strong>Seizures</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Young</strong> <strong>Dogs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Cats</strong>: <strong>Pathophysiology</strong> <strong>and</strong> Diagnosis CE 449<br />

tal seizures with further categorization accord<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

cl<strong>in</strong>ical features (i.e., focal clonic, focal tonic, or<br />

myoclonic seizures; spasms). 40,41<br />

A classification scheme for seizures accord<strong>in</strong>g to their<br />

cl<strong>in</strong>ical appearance <strong>in</strong> domestic animals has not been<br />

thoroughly def<strong>in</strong>ed, <strong>and</strong> currently used schemes are<br />

extrapolated from the human literature. 42,43 In veter<strong>in</strong>ary<br />

medic<strong>in</strong>e, seizure types are classified <strong>in</strong>to two major categories:<br />

generalized <strong>and</strong> focal. 44 A generalized seizure<br />

often reflects a widespread seizure focus, produc<strong>in</strong>g loss<br />

of consciousness, autonomic activity, <strong>and</strong> whole body<br />

movements with alternat<strong>in</strong>g tonic <strong>and</strong> clonic phases of<br />

movements. A focal seizure reflects the activity of a local<br />

seizure focus <strong>in</strong> an area produc<strong>in</strong>g motor activity. It has<br />

been believed that generalized motor seizures are the<br />

most <strong>com</strong>mon seizure type <strong>in</strong> dogs. 42,45,46 This has<br />

recently been brought <strong>in</strong>to question by Berendt <strong>and</strong><br />

Gram 47 who applied a human classification scheme for<br />

epilepsies to dogs. Results showed that focal seizures<br />

with <strong>and</strong> without generalization were most <strong>com</strong>mon<br />

<strong>and</strong> further emphasized reevaluation of currently used<br />

term<strong>in</strong>ology for epilepsy <strong>in</strong> veter<strong>in</strong>ary medic<strong>in</strong>e. In puppies,<br />

generalized tonic seizures have been observed as<br />

early as 4 weeks of age. 48 Immaturity of the bra<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

neurotransmission processes may prevent more accurate<br />

recognition of seizures <strong>in</strong> younger animals.<br />

CAUSE<br />

Recurrent seizures are more broadly def<strong>in</strong>ed as epilepsies.<br />

Podell et al 42 adopted a nomenclature scheme from<br />

human epilepsies based on identifiable cause. Primary<br />

epileptic seizure (i.e., idiopathic) is the term used if an<br />

<strong>Seizures</strong> <strong>in</strong> young dogs <strong>and</strong> cats often reflect a symptomatic or an<br />

acquired cause; however, idiopathic epilepsy is be<strong>in</strong>g recognized<br />

more frequently as a diagnostic differential <strong>in</strong> younger animals.<br />

underly<strong>in</strong>g cause cannot be identified. If seizures result<br />

from a structural lesion, they are def<strong>in</strong>ed as secondary<br />

epileptic seizures. The term reactive epileptic seizure is used<br />

when there is a reaction of the normal bra<strong>in</strong> to transient<br />

systemic <strong>in</strong>sult or physiologic stresses; these seizures are<br />

not considered recurrent. Epilepsies are also described as<br />

asymptomatic (i.e., primary, idiopathic) <strong>and</strong> symptomatic<br />

(i.e., secondary). 49 This article uses the term<strong>in</strong>ology<br />

of asymptomatic <strong>and</strong> symptomatic epilepsies.<br />

June 2005 COMPENDIUM

450 CE<br />

<strong>Seizures</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Young</strong> <strong>Dogs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Cats</strong>: <strong>Pathophysiology</strong> <strong>and</strong> Diagnosis<br />

Table 1. Causes of <strong>Seizures</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Young</strong> <strong>Dogs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Cats</strong> a<br />

Disorder/Category Affected Breeds/Specific Diseases<br />

Developmental Anomalies<br />

Hydrocephalus Boston terrier, Chihuahua, English bulldog, Maltese, Lhasa apso,<br />

Pomeranian, toy poodle, Cairn terrier, pug, Pek<strong>in</strong>gese, Siamese cat<br />

Hydranencephaly, porencephaly Secondary to <strong>in</strong>fection<br />

Lissencephaly Lhasa apso, Irish setter, wire fox terrier, domestic shorthaired cat,<br />

Korat cat<br />

Polymicrogyria Poodle<br />

Agenesis of corpus callosum Domestic shorthaired cat, Labrador retriever<br />

D<strong>and</strong>y-Walker syndrome Not breed specific <strong>in</strong> dogs <strong>and</strong> cats<br />

Chiari malformation Cavalier K<strong>in</strong>g Charles spaniel, other small-breed dogs<br />

Intracranial arachnoid cyst Not breed specific<br />

Degenerative<br />

Leukodystrophy Dalmatian, Labrador retriever, Shetl<strong>and</strong> sheepdog, Samoyed, silky<br />

terrier<br />

Alex<strong>and</strong>er’s disease (Scottish terrier, m<strong>in</strong>iature poodle,<br />

Burmese Mounta<strong>in</strong> dog, Labrador retriever)<br />

Metachromatic leukodystrophy Domestic shorthaired cat<br />

Subacute necrotiz<strong>in</strong>g encephalomyelopathy Australian cattle dog, Alaskan husky, Maltese<br />

(mitochondrial encephalopathy)<br />

Spongiform encephalopathy Saluki, Labrador retriever, silky terrier, Egyptian Mau cat<br />

Glycogen storage disease Type 1 (silky terrier dog, domestic shorthaired cat, toy breeds),<br />

type 2 (domestic shorthaired cat), type 4 (Norwegian forest cat)<br />

Lysosomal storage disease GME1 gangliosidosis (German shorthaired po<strong>in</strong>ter, Portugese water<br />

dog, beagle, Alaskan husky, Siamese cat [type 2], domestic<br />

shorthaired cat [types 1 <strong>and</strong> 2], Korat cat [type 2])<br />

GME2 gangliosidosis (Siamese cat, domestic short-haired cat, Korat cat)<br />

Fucosidosis (English spr<strong>in</strong>ger spaniel)<br />

Glycoprote<strong>in</strong>osis (Lafora’s disease; Basset hound, m<strong>in</strong>iature poodle,<br />

beagle)<br />

Ceroid lipofusc<strong>in</strong>osis (<strong>in</strong>fantile, juvenile) Chihuahua, Dalmatian, English setter, dachshund, saluki, Australian<br />

blue heeler, Australian cattle dog, Border collie, Siamese cat<br />

Multisystemic neuronal degeneration Cocker spaniel, Rhodesian ridgeback<br />

Hereditary quadriplegia <strong>and</strong> amblyopia Irish setter<br />

Metabolic<br />

Portosystemic shunt<strong>in</strong>g Yorkshire terrier, Maltese, schnauzer, Irish wolfhound, Old English<br />

sheepdog<br />

Hepatic microvascular dysplasia Poodle, schnauzer, dachshund, Yorkshire terrier, shih tzu, cocker<br />

spaniel<br />

Hypoglycemia Toy <strong>and</strong> m<strong>in</strong>iature breeds<br />

Hypoxemia Neonatal asphyxia<br />

Hypocalcemia Primary hypoparathyroidism<br />

COMPENDIUM June 2005

Specific seizure types have been associated with specific<br />

disease processes <strong>in</strong> humans; however, this still<br />

needs further evaluation <strong>in</strong> veter<strong>in</strong>ary medic<strong>in</strong>e. Podell<br />

et al 42 found a higher probability of symptomatic<br />

epilepsy <strong>in</strong> dogs with a short <strong>in</strong>terictal <strong>in</strong>terval <strong>and</strong> focal<br />

seizures, support<strong>in</strong>g the belief that focal seizures are an<br />

<strong>in</strong>dication of a structural cerebral lesion. Similar results<br />

were reported <strong>in</strong> later studies by Berendt <strong>and</strong> Gram 47 as<br />

well as Patterson et al. 50 In contrast, these results additionally<br />

documented that dogs considered idiopathic<br />

epileptics also exhibited focal seizures. A more recent<br />

study of vizslas with <strong>in</strong>herited idiopathic epilepsy<br />

showed that focal seizures of variable frequency were the<br />

predom<strong>in</strong>ant seizure type. 50 Age is also a significant predictor<br />

of symptomatic epileptic seizures <strong>in</strong> young dogs<br />

(i.e.,

452 CE<br />

<strong>Seizures</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Young</strong> <strong>Dogs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Cats</strong>: <strong>Pathophysiology</strong> <strong>and</strong> Diagnosis<br />

Figure 1. Gross necropsy image of a lissencephalic bra<strong>in</strong><br />

from a young Lhasa apso with a history of seizures. Note<br />

the lack of gyri <strong>and</strong> sulci <strong>in</strong> the cerebral cortex. (Courtesy of Dr.<br />

Gerald R. Bratton,Texas A & M University)<br />

than 1 year of age. 42 Internal (Figure 2) <strong>and</strong> external<br />

hydrocephalus refer to <strong>in</strong>creased fluid accumulation<br />

with<strong>in</strong> the ventricular <strong>and</strong> subarachnoid spaces, respectively.<br />

Non<strong>com</strong>municat<strong>in</strong>g (i.e., obstructive) hydrocephalus<br />

refers to <strong>in</strong>creased cerebrosp<strong>in</strong>al fluid (CSF) only with<strong>in</strong><br />

the ventricular system, <strong>and</strong> <strong>com</strong>municat<strong>in</strong>g refers to<br />

<strong>in</strong>creased CSF with<strong>in</strong> the ventricular system <strong>and</strong> subarachnoid<br />

space. Congenital hydrocephalus often represents<br />

a secondary manifestation of a developmental (e.g.,<br />

Chiari type 1–like malformation) 55 or an acquired (e.g.,<br />

per<strong>in</strong>atal exposure to tox<strong>in</strong>s or <strong>in</strong>fectious disease) disorder.<br />

56–58 Congenital hydrocephalus is associated with<br />

fusion of the rostral colliculi, caus<strong>in</strong>g secondary mesencephalic<br />

aqueductal stenosis. Head conformation often<br />

<strong>in</strong>volves a dome shape <strong>and</strong> an open bregmatic fontanelle.<br />

Cl<strong>in</strong>ical signs of hydrocephalus vary <strong>in</strong> severity <strong>and</strong> typically<br />

manifest with seizure activity <strong>and</strong> forebra<strong>in</strong> dys-<br />

Figure 2. Gross necropsy image of severe <strong>in</strong>ternal<br />

hydrocephalus from a 4-month-old party (multicolored)<br />

poodle. Note the enlarged lateral ventricles <strong>and</strong> collapsed<br />

cerebrocortical tissue. (Courtesy of Dr. Gayle C. Johnson,<br />

University of Missouri)<br />

function. Forebra<strong>in</strong> signs <strong>in</strong>clude mentation changes<br />

such as disorientation, obtundation, <strong>and</strong> stupor as well as<br />

behavioral abnormalities that can consist of an <strong>in</strong>ability<br />

to learn skills such as housebreak<strong>in</strong>g. 59 Hydrocephalus<br />

can be diagnosed us<strong>in</strong>g MRI or <strong>com</strong>puted tomography<br />

(CT), ultrasonography, <strong>and</strong> electroencephalography. 59–61<br />

Medical therapies can reduce the severity of cl<strong>in</strong>ical<br />

signs, presumably by alter<strong>in</strong>g CSF production. The goal<br />

of surgical management is shunt<strong>in</strong>g CSF from the ventricles<br />

to another space (e.g., atrium, abdom<strong>in</strong>al cavity).<br />

Shunt<strong>in</strong>g procedures are the ma<strong>in</strong>stay of therapy for<br />

hydrocephalus <strong>in</strong> human medic<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> are now advocated<br />

<strong>in</strong> veter<strong>in</strong>ary medic<strong>in</strong>e. 62,63<br />

Only a few <strong>in</strong>born errors of metabolism (e.g.,<br />

organic/mitochondrial encephalopathies) <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

cerebral cortical tissue can cause cl<strong>in</strong>ical signs of seizure<br />

<strong>in</strong> dogs. 64–66 Neuronal metabolism is directly affected<br />

when the enzyme defect is located <strong>in</strong> a major metabolic<br />

pathway. Cl<strong>in</strong>ical descriptions for some of the<br />

organic/mitochondrial encephalopathies <strong>in</strong>clude<br />

episodic extensor rigidity, myoclonus, <strong>and</strong> epileptiformlike<br />

seizures. 64–66 Lysosomal storage diseases cause<br />

seizures by <strong>in</strong>terference of neuronal metabolism or accumulation<br />

of <strong>in</strong>tracellular by-products. Seizure events<br />

that occur with some storage disorders usually manifest<br />

at the end stage of the disease process. Storage disorders<br />

for which seizure activity is a predom<strong>in</strong>ant cl<strong>in</strong>ical fea-<br />

COMPENDIUM June 2005

ture <strong>in</strong>clude ceroid lipofusc<strong>in</strong>osis, glycoprote<strong>in</strong>oses, <strong>and</strong><br />

leukodystrophies. 67<br />

Metabolic<br />

Hypoxemia <strong>in</strong> young animals is often suspected after<br />

severe respiratory <strong>and</strong> cardiovascular <strong>com</strong>promise. In<br />

addition, hypoxemia may <strong>in</strong>crease the anesthetic risk <strong>in</strong><br />

patients undergo<strong>in</strong>g early spay <strong>and</strong> neuter procedures.<br />

Bra<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>jury <strong>in</strong> newborn fetuses may be associated with<br />

hypotensive effects <strong>in</strong>stead of hypoxia or acidosis. 68<br />

Dur<strong>in</strong>g the period of hypoxia–ischemia <strong>and</strong> reperfusion<br />

<strong>in</strong>jury, various cytotoxic processes <strong>in</strong>clude cellular energy<br />

failure, excitoxicity, free radical damage, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>tracellular<br />

calcium accumulation. 69 Hypercapnia may also be an<br />

important <strong>com</strong>ponent of neonatal asphyxia. Fourteenday-old<br />

neonatal dogs had <strong>in</strong>creased seizure susceptibility<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g the recovery phase of experimentally <strong>in</strong>duced<br />

hypercapnia (i.e., partial pressure of carbon dioxide values:<br />

50 to 100 mm Hg). 70<br />

Hypoglycemia at glucose concentrations less than 40<br />

mg/dl can precipitate neuroglycopenia. Neuroglycopenia<br />

is manifested by depression, hypothermia, weakness,<br />

seizures, <strong>and</strong> <strong>com</strong>a. Factors responsible for cl<strong>in</strong>ical signs<br />

of neuroglycopenia <strong>in</strong>clude rate of decrease, level of<br />

hypoglycemia, <strong>and</strong> duration of hypoglycemia. 71 Glucose<br />

is the predom<strong>in</strong>ant energy substrate for the adult <strong>and</strong><br />

neonatal bra<strong>in</strong>. Although the receptor numbers for glucose<br />

transport prote<strong>in</strong> are low <strong>in</strong> the immature bra<strong>in</strong>,<br />

the transport prote<strong>in</strong> for ketone bodies as well as lactate<br />

<strong>and</strong> pyruvate is high. Studies of newborn dogs have<br />

shown that dur<strong>in</strong>g hypoglycemia, lactic acid is not only<br />

<strong>in</strong>corporated <strong>in</strong>to the per<strong>in</strong>atal bra<strong>in</strong> but also consumed<br />

to the extent that the metabolite can support up to 60%<br />

or more of total cerebral energy metabolism. 72 Although<br />

the neonatal bra<strong>in</strong> can readily metabolize ketone bodies,<br />

lack of body fat <strong>and</strong> prolonged time necessary to produce<br />

ketones prevent this mechanism from protect<strong>in</strong>g<br />

neonates from acute hypoglycemia. 73 Juvenile-onset<br />

hypoglycemia occurs because of immature hepatic<br />

enzyme systems, deficiency of glucagon, <strong>and</strong> deficiency<br />

<strong>Seizures</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Young</strong> <strong>Dogs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Cats</strong>: <strong>Pathophysiology</strong> <strong>and</strong> Diagnosis CE 453<br />

of gluconeogenic substrates. Fatty liver syndrome causes<br />

hypoglycemia <strong>in</strong> toy breed puppies at 4 to 16 weeks of<br />

age. 74 Persistent juvenile hypoglycemia is often related<br />

to a glycogen storage disorder. 75 Extr<strong>in</strong>sic factors that<br />

cause hypoglycemia <strong>in</strong>clude stress, hypothermia, parasitism,<br />

<strong>and</strong> low birth weight. In addition, hypoglycemia<br />

<strong>com</strong>b<strong>in</strong>ed with hypoxia–ischemia is more deleterious to<br />

the immature bra<strong>in</strong> than either condition alone. 76<br />

Portosystemic shunts (PSSs) are <strong>com</strong>mon congenital<br />

defects caus<strong>in</strong>g hepatoencephalopathy <strong>in</strong> dogs <strong>and</strong><br />

cats. 77,78 Common cl<strong>in</strong>ical signs of hepatoencephalopathy<br />

<strong>in</strong>clude ataxia, circl<strong>in</strong>g, depression, behavior changes, <strong>and</strong><br />

seizures. A variety of <strong>com</strong>pounds have been implicated<br />

<strong>in</strong> the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy, although<br />

this process is poorly understood. Postulated causes<br />

<strong>in</strong>clude elevated ammonia, altered ratios of neurotransmitters,<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased bra<strong>in</strong> concentrations of benzodiazep<strong>in</strong>e-like<br />

neurotransmitters. 79 Recent studies found<br />

higher concentrations of glutam<strong>in</strong>e, tryptophan, <strong>and</strong><br />

An immature bra<strong>in</strong> is more prone to seizures<br />

than is a mature bra<strong>in</strong> because of multiple<br />

changes that occur dur<strong>in</strong>g development.<br />

qu<strong>in</strong>ol<strong>in</strong>ate, a metabolite of tryptophan, <strong>in</strong> the CSF of<br />

dogs with PSS. 80 Qu<strong>in</strong>ol<strong>in</strong>ate is an agonist of the<br />

NMDA receptor, <strong>and</strong> the develop<strong>in</strong>g bra<strong>in</strong> is more sensitive<br />

to NMDA activation. 81 This may play a role <strong>in</strong><br />

development of seizure activity <strong>in</strong> young dogs with PSSs.<br />

Pathologic lesions are characterized by protoplasmic<br />

astrocytic proliferation (as <strong>in</strong> Alzheimer type 2 reactions)<br />

<strong>and</strong> spongiform changes <strong>in</strong> the bra<strong>in</strong>s of dogs with<br />

PSSs. 82 Treatment <strong>in</strong>volves manag<strong>in</strong>g the hepatic dysfunction<br />

<strong>and</strong> encephalopathy. <strong>Seizures</strong> <strong>and</strong> neurologic<br />

sequelae follow<strong>in</strong>g PSS attenuation have been well documented.<br />

83–85 Neurologic <strong>com</strong>plications have been associated<br />

with all of the occlusion methods. 86 Potential risk<br />

factors for neurologic <strong>com</strong>plications <strong>in</strong>clude older dogs<br />

<strong>and</strong> dogs with s<strong>in</strong>gle extrahepatic <strong>and</strong> portoazygous<br />

shunts. 86 The pathophysiologic mechanisms of postligational<br />

seizures are poorly understood. 87<br />

Inflammatory<br />

<strong>Seizures</strong> occur <strong>in</strong> about 13% of dogs with CNS <strong>in</strong>flammatory<br />

diseases. 88 <strong>Cats</strong> with seizures were frequently<br />

June 2005 COMPENDIUM

454 CE<br />

<strong>Seizures</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Young</strong> <strong>Dogs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Cats</strong>: <strong>Pathophysiology</strong> <strong>and</strong> Diagnosis<br />

diagnosed with <strong>in</strong>flammatory disease (47% [14 of 30] of<br />

cats) of suspected viral or immune-mediated orig<strong>in</strong>. 89<br />

Can<strong>in</strong>e distemper virus (CDV) encephalitis is the most<br />

<strong>com</strong>mon <strong>in</strong>fectious <strong>in</strong>flammatory cause of seizures <strong>in</strong><br />

dogs younger than 1 year of age. 42 Specifically, CDV<br />

causes acute polioencephalitis <strong>in</strong> young dogs. 90 <strong>Seizures</strong><br />

often are focal, which is characterized by “chew<strong>in</strong>g gum”<br />

seizures, or consist of generalized motor activity. 88,90 Similarly,<br />

seizures have been reported with postvacc<strong>in</strong>al CDV<br />

encephalitis <strong>in</strong> puppies. 91 These seizures are often pro-<br />

gressive <strong>and</strong> refractory to antiepileptic drug therapy.<br />

Identify<strong>in</strong>g the underly<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>flammatory disease process<br />

is important because the disease cont<strong>in</strong>ues to progress<br />

without appropriate treatment.<br />

<strong>Dogs</strong> with non<strong>in</strong>fectious <strong>in</strong>flammatory disorders with<br />

cerebral cortical <strong>in</strong>volvement cl<strong>in</strong>ically manifest seizure<br />

activity. Granulomatous men<strong>in</strong>goencephalomyelitis<br />

(GME) rarely affects young dogs 92 <strong>and</strong> is an <strong>in</strong>flammatory<br />

disease of the white matter of the bra<strong>in</strong>. 93–95 The<br />

dissem<strong>in</strong>ated form is usually acute <strong>and</strong> rapidly progressive,<br />

whereas the focal form progresses more slowly.<br />

About 20% of affected dogs have seizures along with<br />

other neurologic deficits. 96 Breed-specific men<strong>in</strong>goencephalitis<br />

occurs <strong>in</strong> pugs, 97 Yorkshire terriers, 98 <strong>and</strong> Malteses.<br />

99 Pathologic features consist of nonsuppurative<br />

necrotiz<strong>in</strong>g men<strong>in</strong>goencephalitis, with a predilection for<br />

the cerebrum <strong>in</strong> pugs <strong>and</strong> Malteses. <strong>Seizures</strong> have also<br />

been reported <strong>in</strong> Yorkshire terriers, but bra<strong>in</strong>-stem signs<br />

are more <strong>com</strong>monly manifested. <strong>Young</strong> dogs are predisposed<br />

<strong>and</strong> are usually 6 months of age or older. <strong>Dogs</strong><br />

with the chronic form more often have cl<strong>in</strong>ical signs of<br />

generalized or focal seizures. Def<strong>in</strong>itive diagnosis of the<br />

non<strong>in</strong>fectious <strong>in</strong>flammatory men<strong>in</strong>goencephalitides is<br />

based on a histopathologic diagnosis. 95 A diagnosis can<br />

be suspected based on patient signalment as well as<br />

f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs from advanced imag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> CSF analysis. 100<br />

Serology can assist <strong>in</strong> rul<strong>in</strong>g out <strong>in</strong>fectious causes.<br />

Eos<strong>in</strong>ophilic men<strong>in</strong>goencephalitis is characterized by<br />

eos<strong>in</strong>ophilic pleocytosis of the CSF <strong>in</strong> dogs <strong>and</strong> a<br />

cat. 101–103 Neurotoxic substances are released from the<br />

granules of eos<strong>in</strong>ophils, caus<strong>in</strong>g secondary neurologic<br />

signs. This disease has been reported <strong>in</strong> young dogs.<br />

Neurologic signs are variable, but seizures can be a pre-<br />

sent<strong>in</strong>g sign. The diagnosis is based on CSF analysis. 101<br />

Recovery or remission of cl<strong>in</strong>ical signs can occur with<br />

glucocorticoid therapy.<br />

Trauma<br />

<strong>Seizures</strong> that occur after traumatic head <strong>in</strong>jury can have<br />

an early or delayed onset. Early onset of seizures occurs<br />

with<strong>in</strong> days of the <strong>in</strong>jury <strong>and</strong> may pose an <strong>in</strong>creased risk<br />

of seizure activity later. Controversy exists <strong>in</strong> human <strong>and</strong><br />

veter<strong>in</strong>ary medic<strong>in</strong>e regard<strong>in</strong>g the role of prophylactic<br />

An abnormal neurologic exam<strong>in</strong>ation between<br />

seizures lends support for a symptomatic cause.<br />

antiepileptic drug therapy for patients with head <strong>in</strong>juries.<br />

Current management <strong>in</strong>volves wait<strong>in</strong>g to beg<strong>in</strong> antiepileptic<br />

drug therapy until seizures actually occur.<br />

Electrical shock result<strong>in</strong>g from curious behaviors <strong>in</strong><br />

young animals may <strong>in</strong>duce seizures <strong>and</strong> potentially lifethreaten<strong>in</strong>g<br />

noncardiogenic pulmonary edema. 104<br />

Toxicosis<br />

The CNS is primarily or secondarily <strong>in</strong>volved with a<br />

variety of toxic substances. Dorman 105 reported that<br />

seizures occurred <strong>in</strong> 8.2% of all cases of suspected toxicosis.<br />

Inquisitive behaviors, lack of discretionary eat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

habits, <strong>and</strong> physiologic alterations <strong>in</strong> drug disposition<br />

render pediatric patients more susceptible to toxicant<br />

exposure. 106 Neonates have a more permeable blood–<br />

bra<strong>in</strong> barrier than do adults, thus <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g the potential<br />

for CNS exposure to tox<strong>in</strong>s. 107 Sk<strong>in</strong> hydration is<br />

highest <strong>in</strong> neonates, <strong>and</strong> topical exposure to lipid-soluble<br />

<strong>com</strong>pounds (e.g., hexachlorophene, organophosphates)<br />

places pediatric patients at higher risk of<br />

significant absorption. 106 Tox<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong>duce seizures through<br />

a number of different mechanisms: <strong>in</strong>creased excitation,<br />

decreased <strong>in</strong>hibition, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terference with energy<br />

metabolism. 108<br />

Asymptomatic Epilepsy<br />

Idiopathic Epilepsy<br />

Epilepsy is characterized by recurrent seizures. 49 The<br />

term idiopathic epilepsy, also known as primary or asymptomatic<br />

epilepsy, is used when there is no identifiable<br />

cause of seizures. The term <strong>in</strong>herited epilepsy is used when<br />

there is a genetic cause of seizures. Epilepsy suspected of<br />

hav<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>herited basis frequently occurs <strong>in</strong> dogs<br />

COMPENDIUM June 2005

younger than 1 year of age. Although most dogs with<br />

idiopathic epilepsy have their first seizure at 1 to 5 years<br />

of age, seizures have been reported <strong>in</strong> Labrador retrievers<br />

as young as 2 months of age. 42,109 An <strong>in</strong>herited basis,<br />

familial transmission, or a higher <strong>in</strong>cidence has been recognized<br />

<strong>in</strong> many breeds. Based on pedigree analysis, a<br />

genetic basis is strongly suspected <strong>in</strong> keeshonds, 110 Belgian<br />

Tervurens, 111 Alsatian shepherds, 112 Labrador <strong>and</strong><br />

golden retrievers, 113,114 vizslas, 50 <strong>and</strong> a colony of laboratory-raised<br />

beagles. 115 The mode of <strong>in</strong>heritance has been<br />

suggested <strong>in</strong> some breeds. Hall <strong>and</strong> Wallace 116 found evidence<br />

of a s<strong>in</strong>gle recessive gene contribut<strong>in</strong>g to a predisposition<br />

of epilepsy <strong>in</strong> keeshonds. Statistics suggest that<br />

seizures <strong>in</strong> Belgian Tervurens result from a <strong>com</strong>plex pattern<br />

of <strong>in</strong>heritance. 117,118 A polygenic multifactorial mode<br />

of <strong>in</strong>heritance is suggested <strong>in</strong> golden <strong>and</strong> Labrador<br />

retrievers. 113,114 An autosomal recessive pattern of <strong>in</strong>heritance<br />

is suspected <strong>in</strong> vizslas with idiopathic epilepsy. 50 In<br />

humans, genes have been identified for ion channel<br />

defects <strong>in</strong> some epilepsies. 119<br />

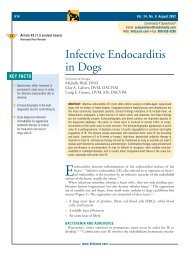

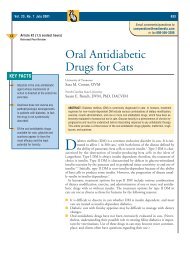

DIAGNOSTIC CONSIDERATIONS<br />

The appropriate diagnostic procedures for seizures <strong>in</strong><br />

young animals are variable <strong>and</strong> depend on the most<br />

likely differentials. 44,53 Tests may be subdivided <strong>in</strong>to procedures<br />

that do <strong>and</strong> do not require anesthesia (Figure 3).<br />

The m<strong>in</strong>imum database should <strong>in</strong>clude patient signalment,<br />

history, physical <strong>and</strong> neurologic exam<strong>in</strong>ations, <strong>and</strong><br />

cl<strong>in</strong>ical pathology. The patient’s history plays an important<br />

role, especially if tox<strong>in</strong> exposure is a consideration.<br />

The history can also help identify vacc<strong>in</strong>ation status,<br />

pedigree <strong>in</strong>formation, environmental factors, <strong>and</strong> seizure<br />

patterns. Abnormal f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs on physical <strong>and</strong> neurologic<br />

exam<strong>in</strong>ations lend support for symptomatic causes of<br />

seizures <strong>and</strong> more extensive diagnostic test<strong>in</strong>g. Neuroanatomic<br />

localization for seizure activity is <strong>in</strong> the forebra<strong>in</strong>.<br />

Neurologic exam<strong>in</strong>ation f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs may reveal<br />

forebra<strong>in</strong> dysfunction or evidence of a multifocal or diffuse<br />

disease process. A funduscopic exam<strong>in</strong>ation may<br />

show active or previous signs of chorioret<strong>in</strong>itis. Cl<strong>in</strong>ical<br />

pathology test<strong>in</strong>g should <strong>in</strong>clude a <strong>com</strong>plete blood count<br />

<strong>Seizures</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Young</strong> <strong>Dogs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Cats</strong>: <strong>Pathophysiology</strong> <strong>and</strong> Diagnosis CE 455<br />

(CBC), serum chemistry profile, <strong>and</strong> ur<strong>in</strong>alysis. Abnormal<br />

f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs may further support a metabolic or toxic<br />

cause of seizures. Screen<strong>in</strong>g tests <strong>in</strong> a serum biochemical<br />

profile should <strong>in</strong>clude blood urea nitrogen, alkal<strong>in</strong>e<br />

phosphatase, alan<strong>in</strong>e transam<strong>in</strong>ase, calcium, <strong>and</strong> blood<br />

glucose levels. Interpretation of results should also take<br />

<strong>in</strong>to account an animal’s age because adult <strong>and</strong> immature<br />

animals have different serum values. Based on cl<strong>in</strong>icopathologic<br />

abnormalities, additional diagnostic test<strong>in</strong>g is<br />

<strong>in</strong>dicated when specific organ pathology is suspected.<br />

Liver function tests, such as pre- <strong>and</strong> postpr<strong>and</strong>ial bile<br />

acid concentrations <strong>and</strong> blood ammonia levels, can provide<br />

evidence of hepatic dysfunction. Sc<strong>in</strong>tigraphy <strong>and</strong><br />

ultrasonographic studies can further aid <strong>in</strong> identify<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

PSS. 120 Profiles for metabolic screen<strong>in</strong>g of blood, ur<strong>in</strong>e,<br />

<strong>and</strong> CSF are useful when storage disorders or <strong>in</strong>born<br />

errors of metabolism are suspected. 121,122<br />

Serology <strong>and</strong> immunologic test<strong>in</strong>g may <strong>in</strong>directly lend<br />

further support to <strong>in</strong>fectious causes. 123 Overall, viral<br />

causes are difficult to def<strong>in</strong>itively diagnose with less <strong>in</strong>vasive<br />

diagnostic test<strong>in</strong>g. Results of serologic test<strong>in</strong>g are also<br />

difficult to <strong>in</strong>terpret because of the presence of circulat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

antibodies from maternal immunity, vacc<strong>in</strong>ation, or environmental<br />

exposure. Immunofluorescent antibody sta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

of epithelial cells from the conjunctiva has reportedly<br />

identified about 54% of dogs with CDV <strong>in</strong>fection. 90,124<br />

Additional neurodiagnostic test<strong>in</strong>g can further determ<strong>in</strong>e<br />

the type <strong>and</strong> extent of <strong>in</strong>tracranial pathology.<br />

Ultrasonography is useful <strong>in</strong> animals with an open bregmatic<br />

fontanelle or <strong>in</strong>tracranial arachnoid cysts. 125,126<br />

F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs of only mild hydrocephalus should be carefully<br />

<strong>in</strong>terpreted because this may not be the <strong>in</strong>cit<strong>in</strong>g cause.<br />

It is important to identify the underly<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>flammatory<br />

or metabolic disease because cl<strong>in</strong>ical signs cont<strong>in</strong>ue to<br />

progress without appropriate treatment.<br />

Advanced imag<strong>in</strong>g such as CT or MRI can aid <strong>in</strong> diagnos<strong>in</strong>g<br />

structural abnormalities related to cranial <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>tracranial malformations, <strong>in</strong>flammatory disorders, <strong>and</strong><br />

neoplasms. MRI is more ideal for identify<strong>in</strong>g soft tissue<br />

abnormalities. In human medic<strong>in</strong>e, the efficacy of us<strong>in</strong>g<br />

CT <strong>in</strong> children after the first nonfebrile seizure has been<br />

questioned based on lack of abnormal f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs. 127<br />

Electroencephalography <strong>in</strong> animals may show characteristic<br />

patterns <strong>in</strong> disease, such as hydrocephalus <strong>and</strong><br />

June 2005 COMPENDIUM

456 CE<br />

<strong>Seizures</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Young</strong> <strong>Dogs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Cats</strong>: <strong>Pathophysiology</strong> <strong>and</strong> Diagnosis<br />

Figure 3. Algorithm of diagnostic considerations regard<strong>in</strong>g seizures <strong>in</strong> young dogs <strong>and</strong> cats.<br />

Electrolyte<br />

monitor<strong>in</strong>g<br />

EEG<br />

Ultrasonography<br />

of the cranium<br />

Glucose<br />

evaluation<br />

encephalitis. 61,128 However, an animal’s age should be<br />

carefully considered because EEG patterns <strong>in</strong> young<br />

animals can mimic patterns associated with disease. An<br />

electroencephalograph can develop the pattern of an<br />

adult dog by approximately 5 months of age. 129 In our<br />

experience, cont<strong>in</strong>ual electroencephalography is also<br />

useful <strong>in</strong> monitor<strong>in</strong>g persistent seizure activity <strong>and</strong> adequate<br />

response to therapy.<br />

CSF analysis is particularly useful <strong>in</strong> identify<strong>in</strong>g the presence<br />

of <strong>in</strong>flammatory disease. 88 Because <strong>in</strong>flammatory dis-<br />

SEIZURE ACTIVITY<br />

Signalment <strong>and</strong> history<br />

Physical <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terictal neurologic exam<strong>in</strong>ation<br />

Cl<strong>in</strong>ical pathology<br />

(CBC, serum chemistry, ur<strong>in</strong>alysis;<br />

blood urea nitrogen, alkal<strong>in</strong>e phosphatase, alan<strong>in</strong>e<br />

transam<strong>in</strong>ase, calcium, <strong>and</strong> glucose levels)<br />

Advanced imag<strong>in</strong>g<br />

(CT, MRI)<br />

CSF analysis<br />

Liver function<br />

test<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Ultrasonography/<br />

sc<strong>in</strong>tigraphy<br />

Fundic exam<strong>in</strong>ation<br />

Serology<br />

Metabolic screen<strong>in</strong>g for<br />

<strong>in</strong>born errors of metabolism<br />

Diagnostic procedures above the dashed l<strong>in</strong>e do not require anesthesia; those below the dashed l<strong>in</strong>e do.<br />

ease is a more likely differential than neoplasia <strong>in</strong> younger<br />

animals, CSF analysis may more often provide a greater<br />

diagnostic yield than imag<strong>in</strong>g procedures alone. CSF can be<br />

collected by punctur<strong>in</strong>g the cerebellomedullary cistern.<br />

Analysis should <strong>in</strong>clude a nucleated cell count, prote<strong>in</strong> concentration,<br />

<strong>and</strong> cytologic evaluation with<strong>in</strong> 30 m<strong>in</strong>utes of<br />

sample collection. Unfortunately, results of CSF analysis<br />

tend to be nonspecific for some disease processes. Intrathecal<br />

antibody production can be determ<strong>in</strong>ed to further assist<br />

<strong>in</strong> diagnos<strong>in</strong>g some <strong>in</strong>fectious diseases. 123<br />

COMPENDIUM June 2005

CONCLUSION<br />

Early recognition of the cause of seizures <strong>in</strong> young<br />

dogs <strong>and</strong> cats is important for appropriate therapeutic<br />

<strong>in</strong>tervention. Inappropriate therapy can delay cessation<br />

of seizures <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>crease patient morbidity <strong>and</strong> mortality.<br />

Watch for an up<strong>com</strong><strong>in</strong>g article on manag<strong>in</strong>g<br />

seizures <strong>in</strong> young dogs <strong>and</strong> cats.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

1. Bunch SE: Anticonvulsant drug therapy <strong>in</strong> <strong>com</strong>panion animals, <strong>in</strong> Kirk RW<br />

(ed): Current Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Therapy IX. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1986, pp<br />

836–844.<br />

2. Cunn<strong>in</strong>gham JG, Farnbach GC: Inheritance <strong>and</strong> idiopathic can<strong>in</strong>e epilepsy.<br />

JAAHA 24:421–424, 1988.<br />

3. O’Brien D: Neurological exam<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> development of the neonatal dog.<br />

Sem<strong>in</strong> Vet Med Surg Small Anim 9:62–67, 1994.<br />

4. Kubova H, Moshe SL: Experimental models of epilepsy <strong>in</strong> young animals. J<br />

Child Neurol 9(suppl 1):S3–S11, 1994.<br />

5. Sanchez RM, Jensen FE: Maturational aspects of epilepsy mechanisms <strong>and</strong><br />

consequences for the immature bra<strong>in</strong>. Epilepsia 42:577–585, 2001.<br />

6. Holmes GL, Khazipov R, Ben Ari Y: New concepts <strong>in</strong> neonatal seizures.<br />

Neuroreport 13:A3–A8, 2002.<br />

7. Hevers W, Luddens H: The diversity of GABAA receptors: Pharmacological<br />

<strong>and</strong> electrophysiological properties of GABAA channel subtypes. Mol Neurobiol<br />

18:35–86, 1998.<br />

8. Seress L, Frotscher M, Ribak CE: Local circuit neurons <strong>in</strong> both the dentate<br />

gyrus <strong>and</strong> Ammon’s horn establish synaptic connections with pr<strong>in</strong>cipal neurons<br />

<strong>in</strong> five-day-old rats: A morphological basis for <strong>in</strong>hibition <strong>in</strong> early development.<br />

Exp Bra<strong>in</strong> Res 78:1–9, 1989.<br />

9. Seress L, Ribak CE: The development of GABAergic neurons <strong>in</strong> the rat<br />

hippocampal formation: An immunocytochemical study. Bra<strong>in</strong> Res Dev<br />

Bra<strong>in</strong> Res 44:197–209, 1988.<br />

10. Kunkel DD, Hendrickson AE, Wu JY, Schwartzkro<strong>in</strong> PA: Glutamic acid<br />

decarboxylase (GAD) immunocytochemistry of develop<strong>in</strong>g rabbit hippocampus.<br />

J Neurosci 6:541–552, 1986.<br />

11. Roberts E, Kuriyama K: Biochemical-physiological correlations <strong>in</strong> studies of<br />

the gamma-am<strong>in</strong>obutyric acid system. Bra<strong>in</strong> Res 8:1–35, 1968.<br />

12. Fritschy JM, Paysan J, Enna A, Mohler H: Switch <strong>in</strong> the expression of rat<br />

GABAA-receptor subtypes dur<strong>in</strong>g postnatal development: An immunohistochemical<br />

study. J Neurosci 14:5302–5324, 1994.<br />

13. Gaiarsa JL, McLean H, Congar P, et al: Postnatal maturation of gammaam<strong>in</strong>obutyric<br />

acid A <strong>and</strong> B-mediated <strong>in</strong>hibition <strong>in</strong> the CA3 hippocampal<br />

region of the rat. J Neurobiol 26:339–349, 1995.<br />

14. Staley KJ, Soldo BL, Proctor WR: Ionic mechanisms of neuronal excitation<br />

by <strong>in</strong>hibitory GABAA receptors. Science 269:977–981, 1995.<br />

15. Platt SR, McDonnell JJ: Status epilepticus: Patient management <strong>and</strong> pharmacologic<br />

therapy. Compend Cont<strong>in</strong> Educ Pract Vet 22:722–729, 2000.<br />

16. <strong>Young</strong> AB, Fagg GE: Excitatory am<strong>in</strong>o acid receptors <strong>in</strong> the bra<strong>in</strong>: Membrane<br />

b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> receptor autoradiographic approaches. Trends Pharmacol<br />

Sci 11:126–133, 1990.<br />

17. Insel TR, Miller LP, Gelhard RE: The ontogeny of excitatory am<strong>in</strong>o acid<br />

receptors <strong>in</strong> rat forebra<strong>in</strong>—I. N-methyl-D-aspartate <strong>and</strong> quisqualate receptors.<br />

Neuroscience 35:31–43, 1990.<br />

18. Furuta A, Rothste<strong>in</strong> JD, Mart<strong>in</strong> LJ: Glutamate transporter prote<strong>in</strong> subtypes<br />

are expressed differentially dur<strong>in</strong>g rat CNS development. J Neurosci<br />

17:8363–8375, 1997.<br />

<strong>Seizures</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Young</strong> <strong>Dogs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Cats</strong>: <strong>Pathophysiology</strong> <strong>and</strong> Diagnosis CE<br />

457<br />

19. Hablitz JJ, He<strong>in</strong>emann U: Extracellular K + <strong>and</strong> Ca2+ changes dur<strong>in</strong>g epileptiform<br />

discharges <strong>in</strong> the immature rat neocortex. Bra<strong>in</strong> Res 433:299–303, 1987.<br />

20. Eayrs JT, Goodhead B: Postnatal development of the cerebral cortex <strong>in</strong> the<br />

rat. J Anat 93:385–402, 1959.<br />

21. Rennie JM: Neonatal seizures. Eur J Pediatr 156:83–87, 1997.<br />

22. Vannucci RC, Fujikawa DG: Energy balance of the immature bra<strong>in</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

status epilepticus, <strong>in</strong> Wasterla<strong>in</strong> CG, Vert P (eds): Neonatal <strong>Seizures</strong>. New<br />

York, Raven Press, 1990, pp 99–112.<br />

23. Sacktor B, Wilson JE, Tiekert CG: Regulation of glycolysis <strong>in</strong> bra<strong>in</strong>, <strong>in</strong> situ,<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g convulsions. J Biol Chem 241:5071–5075, 1966.<br />

24. <strong>Young</strong> RS, Osbakken MD, Briggs RW, et al: 31P NMR study of cerebral<br />

metabolism dur<strong>in</strong>g prolonged seizures <strong>in</strong> the neonatal dog. Ann Neurol<br />

18:14–20, 1985.<br />

25. Marks JD, B<strong>in</strong>dokas VP, Zhang XM: Maturation of vulnerability to excitotoxicity:<br />

Intracellular mechanisms <strong>in</strong> cultured postnatal hippocampal neurons.<br />

Bra<strong>in</strong> Res Dev Bra<strong>in</strong> Res 124:101–116, 2000.<br />

26. Marks JD, Friedman JE, Haddad GG: Vulnerability of CA1 neurons to glutamate<br />

is developmentally regulated. Bra<strong>in</strong> Res Dev Bra<strong>in</strong> Res 97:194–206,<br />

1996.<br />

27. Liu Z, Stafstrom CE, Sarkisian M, et al: Age-dependent effects of glutamate<br />

toxicity <strong>in</strong> the hippocampus. Bra<strong>in</strong> Res Dev Bra<strong>in</strong> Res 97:178–184, 1996.<br />

28. McCabe BK, Silveira DC, Cilio MR, et al: Reduced neurogenesis after<br />

neonatal seizures. J Neurosci 21:2094–2103, 2001.<br />

29. Moshe SL, Albala BJ: K<strong>in</strong>dl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g rats: Persistence of seizures<br />

<strong>in</strong>to adulthood. Bra<strong>in</strong> Res 256:67–71, 1982.<br />

30. Schmid R, T<strong>and</strong>on P, Stafstrom CE, Holmes GL: Effects of neonatal<br />

seizures on subsequent seizure-<strong>in</strong>duced bra<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>jury. Neurology<br />

53:1754–1761, 1999.<br />

31. Liu Z, Yang Y, Silveira DC, et al: Consequences of recurrent seizures dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

early bra<strong>in</strong> development. Neuroscience 92:1443–1454, 1999.<br />

32. Montgomery DL, Lee AC: Bra<strong>in</strong> damage <strong>in</strong> the epileptic beagle dog. Vet<br />

Pathol 20:160–169, 1983.<br />

33. Mart<strong>in</strong> E, Boesch C, Zuerrer M, et al: MR imag<strong>in</strong>g of bra<strong>in</strong> maturation <strong>in</strong><br />

normal <strong>and</strong> developmentally h<strong>and</strong>icapped children. J Comput Assist Tomogr<br />

14:685–692, 1990.<br />

34. Verity CM: Do seizures damage the bra<strong>in</strong>? The epidemiological evidence.<br />

Arch Dis Child 78:78–84, 1998.<br />

35. Commission on classification <strong>and</strong> term<strong>in</strong>ology of the <strong>in</strong>ternational league<br />

aga<strong>in</strong>st epilepsy: Proposal for classification of epilepsies <strong>and</strong> epileptic syndromes.<br />

Epilepsia 26:268–278, 1985.<br />

36. Jayakar P, Chiappa KH: Cl<strong>in</strong>ical correlations of photoparoxysmal responses.<br />

Electroencephalogr Cl<strong>in</strong> Neurophysiol 75:251–254, 1990.<br />

37. Nordli Jr DR, Kuroda MM, Hirsch LJ: The ontogeny of partial seizures <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>fants <strong>and</strong> young children. Epilepsia 42:986–990, 2001.<br />

38. Volpe JJ: Neonatal seizures: Current concepts <strong>and</strong> revised classification. Pediatrics<br />

84:422–428, 1989.<br />

39. Tharp BR: Neonatal seizures <strong>and</strong> syndromes. Epilepsia 43(suppl 3):2–10,<br />

2002.<br />

40. Mizrahi EM, Kellaway P: Characterization <strong>and</strong> classification of neonatal<br />

seizures. Neurology 37:1837–1844, 1975.<br />

41. Mizrahi EM: Neonatal seizures <strong>and</strong> neonatal epileptic syndromes. Neurologic<br />

Cl<strong>in</strong>ics 19:427–463, 2001.<br />

42. Podell M, Fenner WR, Powers JD: Seizure classification <strong>in</strong> dogs from a nonreferral-based<br />

population. JAVMA 206:1721–1728, 1995.<br />

43. March PA: <strong>Seizures</strong>: Classification, etiologies, <strong>and</strong> pathophysiology. Cl<strong>in</strong><br />

Tech Small Anim Pract 13:119–131, 1998.<br />

44. Lorenz MD, Kornegay JN: <strong>Seizures</strong>, narcolepsy, <strong>and</strong> cataplexy, <strong>in</strong> Lorenz<br />

MD, Kornegay JN (eds): H<strong>and</strong>book of Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Neurology. St. Louis, Elsevier<br />

Science, 2004, pp 323–344.<br />

June 2005 COMPENDIUM

458 CE<br />

<strong>Seizures</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Young</strong> <strong>Dogs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Cats</strong>: <strong>Pathophysiology</strong> <strong>and</strong> Diagnosis<br />

45. Farnbach GC: <strong>Seizures</strong> <strong>in</strong> the dog. Part I: Basis, classification, <strong>and</strong> predilection.<br />

Compend Cont<strong>in</strong> Educ Pract Vet 6:569–576, 1984.<br />

46. Heynold Y, Faissler D, Steffen F, Jaggy A: Cl<strong>in</strong>ical, epidemiological <strong>and</strong><br />

treatment results of idiopathic epilepsy <strong>in</strong> 54 Labrador retrievers: A longterm<br />

study. J Small Anim Pract 38:7–14, 1997.<br />

47. Berendt M, Gram L: Epilepsy <strong>and</strong> seizure classification <strong>in</strong> 63 dogs: A reappraisal<br />

of veter<strong>in</strong>ary epilepsy term<strong>in</strong>ology. J Vet Intern Med 13:14–20, 1999.<br />

48. Knowles K: Seizure disorders <strong>in</strong> the pediatric animal patient. Sem<strong>in</strong> Vet Med<br />

Surg Small Anim 9:108–115, 1994.<br />

49. Thomas WB: Idiopathic epilepsy <strong>in</strong> dogs. Vet Cl<strong>in</strong> North Am Small Anim<br />

Pract 30:183–206, vii, 2000.<br />

50. Patterson EE, Mickelson JR, Da Y, et al: Cl<strong>in</strong>ical characteristics <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>heritance<br />

of idiopathic epilepsy <strong>in</strong> Vizslas. J Vet Intern Med 17:319–325, 2003.<br />

51. Oliver JE, Lorenz MD, Kornegay JN: H<strong>and</strong>book of Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Neurology.<br />

Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1997.<br />

52. Podell M: <strong>Seizures</strong> <strong>in</strong> dogs. Vet Cl<strong>in</strong> North Am Small Anim Pract 26:779–809,<br />

1996.<br />

53. Dewey CW: Encephalopathies: Disorders of the bra<strong>in</strong>, <strong>in</strong> Dewey CW (ed):<br />

A Practical Guide to Can<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> Fel<strong>in</strong>e Neurology. Ames, Iowa State University<br />

Press, 2003, pp 99–178.<br />

54. Becker SV, Selby LA: Can<strong>in</strong>e hydrocephalus. Compend Cont<strong>in</strong> Educ Pract Vet<br />

2:647–652, 1980.<br />

55. Lu D, Lamb CR, Pfeiffer NE, Targett MP: Neurological signs <strong>and</strong> results of<br />

magnetic resonance imag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> 40 cavalier K<strong>in</strong>g Charles spaniels with<br />

Chiari type I-like malformations. Vet Rec 153:260–263, 2003.<br />

56. Csiza CK, Scott FW, de Lahunta A, Gillespie JH: Pathogenesis of fel<strong>in</strong>e<br />

panleukopenia virus <strong>in</strong> susceptible newborn kittens. I: Cl<strong>in</strong>ical signs, hematology,<br />

serology, virology. Infect Immun 3:833–837, 1971.<br />

57. Scott FW, de Lahunta A, Schultz RD, et al: Teratogenesis <strong>in</strong> cats associated<br />

with griseofulv<strong>in</strong> therapy. Teratology 11:79–86, 1975.<br />

58. Summers BA, Cumm<strong>in</strong>gs JF, de Lahunta A: Malformations of the central<br />

nervous system, <strong>in</strong> Summers BA, Cumm<strong>in</strong>gs JF, de Lahunta A (eds): Veter<strong>in</strong>ary<br />

Neuropathology. St. Louis, Mosby, 2000, pp 68–94.<br />

59. Simpson ST: Hydrocephalus, <strong>in</strong> Kirk RW, Bonagura JD (eds): Current Veter<strong>in</strong>ary<br />

Therapy X: Small Animal Practice. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1989,<br />

pp 842–847.<br />

60. Hudson JA, Simpson ST, Buxton DF, et al: Ultrasonographic diagnosis of<br />

can<strong>in</strong>e hydrocephalus. Vet Radiol 31:50–58, 1990.<br />

61. Klemm WR, Hall CL: Electroencephalograms of anesthetized dogs with<br />

hydrocephalus. Am J Vet Res 32:1859–1864, 1971.<br />

62. Levesque DC, Plummer SB: Ventriculoperitoneal shunt<strong>in</strong>g as a treatment<br />

for hydrocephalus. Proc 12th ACVIM Forum:891–893, 1994.<br />

63. Gage ED, Hoerle<strong>in</strong> BF: Surgical treatment of can<strong>in</strong>e hydrocephalus by verticuloatrial<br />

shunt<strong>in</strong>g. JAVMA 153:1418–1431, 1968.<br />

64. Podell M, Shelton GD, Nyhan WL, et al: Methylmalonic <strong>and</strong> malonic<br />

aciduria <strong>in</strong> a dog with progressive encephalomyelopathy. Metab Bra<strong>in</strong> Dis<br />

11:239–247, 1996.<br />

65. Brenner O, de Lahunta A, Summers BA, et al: Hereditary polioencephalomyelopathy<br />

of the Australian cattle dog. Acta Neuropathol (Berl)<br />

94:54–66, 1997.<br />

66. Brenner O, Wakshlag JJ, Summers BA, de Lahunta A: Alaskan Husky<br />

encephalopathy: A can<strong>in</strong>e neurodegenerative disorder resembl<strong>in</strong>g subacute<br />

necrotiz<strong>in</strong>g encephalomyelopathy (Leigh syndrome). Acta Neuropathol (Berl)<br />

100:50–62, 2000.<br />

67. Skelly BJ, Frankl<strong>in</strong> RJM: Recognition <strong>and</strong> diagnosis of lysosomal storage<br />

diseases <strong>in</strong> the cat <strong>and</strong> dog. J Vet Intern Med 16:133–141, 2002.<br />

68. Williams CE, Mallard C, Tan W, Gluckman PD: <strong>Pathophysiology</strong> of per<strong>in</strong>atal<br />

asphyxia. Cl<strong>in</strong> Per<strong>in</strong>atol 20:305–325, 1993.<br />

69. Gluckman PD, P<strong>in</strong>al CS, Gunn AJ: Hypoxic-ischemic bra<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>jury <strong>in</strong> the<br />

newborn: <strong>Pathophysiology</strong> <strong>and</strong> potential strategies for <strong>in</strong>tervention. Sem<strong>in</strong><br />

Neonatol 6:109–120, 2001.<br />

70. Yoshioka H, Nioka S, Miyake H, et al: Seizure susceptibility dur<strong>in</strong>g recovery<br />

from hypercapnia <strong>in</strong> neonatal dogs. Pediatr Neurol 15:36–40, 1996.<br />

71. Howerton TL, Shell LG: Neurologic manifestations of altered serum glucose.<br />

Prog Vet Neurol 3:57–64, 1992.<br />

72. Hellmann J, Vannucci RC, Nardis EE: Blood–bra<strong>in</strong> barrier permeability to<br />

lactic acid <strong>in</strong> the newborn dog: Lactate as a cerebral metabolic fuel. Pediatr<br />

Res 16:40–44, 1982.<br />

73. Atk<strong>in</strong>s CE: Disorders of glucose homeostasis <strong>in</strong> neonatal <strong>and</strong> juvenile dogs:<br />

Hypoglycemia (Part I). Compend Cont<strong>in</strong> Educ Pract Vet 6:197–206, 1984.<br />

74. van der L<strong>in</strong>de-Sipman JS, van den Ingh TS, van Toor AJ: Fatty liver syndrome<br />

<strong>in</strong> puppies. JAAHA 26:9–12, 1990.<br />

75. Atk<strong>in</strong>s CE: Disorders of glucose homeostasis <strong>in</strong> neonatal <strong>and</strong> juvenile dogs:<br />

Hypoglycemia (Part II). Compend Cont<strong>in</strong> Educ Pract Vet 6:353–364, 1984.<br />

76. Vannucci RC, Vannucci SJ: Hypoglycemic bra<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>jury. Sem<strong>in</strong> Neonatol<br />

6:147–155, 2001.<br />

77. Center SA, Magne ML: Historical, physical exam<strong>in</strong>ation, <strong>and</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>icopathologic<br />

features of portosystemic vascular anomalies <strong>in</strong> the dog <strong>and</strong> cat. Sem<strong>in</strong><br />

Vet Med Surg Small Anim 5:83–93, 1990.<br />

78. Butler LM, Fossum TW, Boothe HW: Surgical management of extrahepatic<br />

portosystemic shunts <strong>in</strong> the dog <strong>and</strong> cat. Sem<strong>in</strong> Vet Med Surg Small Anim<br />

5:127–133, 1990.<br />

79. Maddison JE: Hepatic encephalopathy: Current concepts of the pathogenesis.<br />

J Vet Intern Med 6:341–353, 1992.<br />

80. Holt DE, Washabau RJ, Djali S, et al: Cerebrosp<strong>in</strong>al fluid glutam<strong>in</strong>e, tryptophan,<br />

<strong>and</strong> tryptophan metabolite concentrations <strong>in</strong> dogs with portosystemic<br />

shunts. Am J Vet Res 63:1167–1171, 2002.<br />

81. McDonald JW, Silverste<strong>in</strong> FS, Johnston MV: Neurotoxicity of N-methyl-Daspartate<br />

is markedly enhanced <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g rat central nervous system.<br />

Bra<strong>in</strong> Res 459:200–203, 1988.<br />

82. Rothuizen J, van den Ingh TS, Voorhout G: Congenital portosystemic<br />

shunts <strong>in</strong> sixteen dogs <strong>and</strong> three cats. J Small Anim Pract 23:67–81, 1982.<br />

83. Mathews K, Gofton N: Congenital extrahepatic portosystemic shunt occlusion<br />

<strong>in</strong> the dog: Gross observations dur<strong>in</strong>g surgical correction. JAAHA<br />

24:387–394, 1988.<br />

84. Matushek KJ, Bjorl<strong>in</strong>g D, Mathews K: Generalized motor seizures after<br />

portosystemic shunt ligation <strong>in</strong> dogs: Five cases (1981–1988). JAVMA<br />

196:2014–2017, 1990.<br />

85. Hardie EM, Kornegay JN, Cullen JM: Status epilepticus after ligation of<br />

portosystemic shunts. Vet Surg 19:412–417, 1990.<br />

86. Tisdall PL, Hunt GB, Youmans KR, Malik R: Neurological dysfunction <strong>in</strong><br />

dogs follow<strong>in</strong>g attenuation of congenital extrahepatic portosystemic shunts. J<br />

Small Anim Pract 41:539–546, 2000.<br />

87. Aronson LR, Gacad RC, Kam<strong>in</strong>sky-Russ K, et al: Endogenous benzodiazep<strong>in</strong>e<br />

activity <strong>in</strong> the peripheral <strong>and</strong> portal blood of dogs with congenital<br />

portosystemic shunts. Vet Surg 26:189–194, 1997.<br />

88. Tipold A: Diagnosis of <strong>in</strong>flammatory <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>fectious diseases of the central<br />

nervous system <strong>in</strong> dogs: A retrospective study. J Vet Intern Med 9:304–314,<br />

1995.<br />

89. Quesnel AD, Parent JM, McDonell W, et al: Diagnostic evaluation of cats<br />

with seizure disorders: 30 cases (1991–1993). JAVMA 210:65–71, 1997.<br />

90. Thomas WB, Sorjonen DC, Steiss JE: A retrospective evaluation of 38 cases<br />

of can<strong>in</strong>e distemper encephalomyelitis. JAAHA 29:129–133, 1993.<br />

91. Cornwell HJ, Thompson H, McC<strong>and</strong>lish IA, et al: Encephalitis <strong>in</strong> dogs<br />

associated with a batch of can<strong>in</strong>e distemper (Rockborn) vacc<strong>in</strong>e. Vet Rec<br />

122:54–59, 1988.<br />

92. Murtaugh RJ, Fenner WR, Johnson GC: Focal granulomatous men<strong>in</strong>goencephalomyelitis<br />

<strong>in</strong> a pup. JAVMA 187:835–836, 1985.<br />

COMPENDIUM June 2005

93. Braund KG: Granulomatous men<strong>in</strong>goencephalomyelitis. JAVMA<br />

186:138–141, 1985.<br />

94. Cordy DR: Can<strong>in</strong>e granulomatous men<strong>in</strong>goencephalomyelitis. Vet Pathol<br />

16:325–333, 1979.<br />

95. Ryan K, Marks SL, Kerw<strong>in</strong> SC: Granulomatous men<strong>in</strong>goencephalomyelitis<br />

<strong>in</strong> dogs. Compend Cont<strong>in</strong> Educ Pract Vet 23:644–650, 2001.<br />

96. Sorjonen DC: Cl<strong>in</strong>ical <strong>and</strong> histopathological features of granulomatous<br />

men<strong>in</strong>goencephalomyelitis <strong>in</strong> dogs. JAAHA 26:141–147, 1990.<br />

97. Cordy DR, Holliday TA: A necrotiz<strong>in</strong>g men<strong>in</strong>goencephalitis of pug dogs.<br />

Vet Pathol 26:191–194, 1989.<br />

98. Tipold A, Fatzer R, Jaggy A, et al: Necrotiz<strong>in</strong>g encephalitis <strong>in</strong> Yorkshire terriers.<br />

J Small Anim Pract 34:623–628, 1993.<br />

99. Stalis IH, Chadwick B, Dayrell-Hart B, et al: Necrotiz<strong>in</strong>g men<strong>in</strong>goencephalitis<br />

of Maltese dogs. Vet Pathol 32:230–235, 1995.<br />

100. Plummer SB, Wheeler SJ, Thrall DE, Kornegay JN: Computed tomography<br />

of primary <strong>in</strong>flammatory bra<strong>in</strong> disorders <strong>in</strong> dogs <strong>and</strong> cats. Vet Radiol Ultrasound<br />

33:307–312, 1992.<br />

101. Smith-Maxie LL, Parent JP, R<strong>and</strong> J, et al: Cerebrosp<strong>in</strong>al fluid analysis <strong>and</strong><br />

cl<strong>in</strong>ical out<strong>com</strong>e of eight dogs with eos<strong>in</strong>ophilic men<strong>in</strong>goencephalomyelitis.<br />

J Vet Intern Med 3:167–174, 1989.<br />

102. Bennett PF, Allan FJ, Guilford WG, et al: Idiopathic eos<strong>in</strong>ophilic men<strong>in</strong>goencephalitis<br />

<strong>in</strong> rottweiler dogs: Three cases (1992–1997). Aust Vet J<br />

75:786–789, 1997.<br />