einstein

einstein

einstein

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

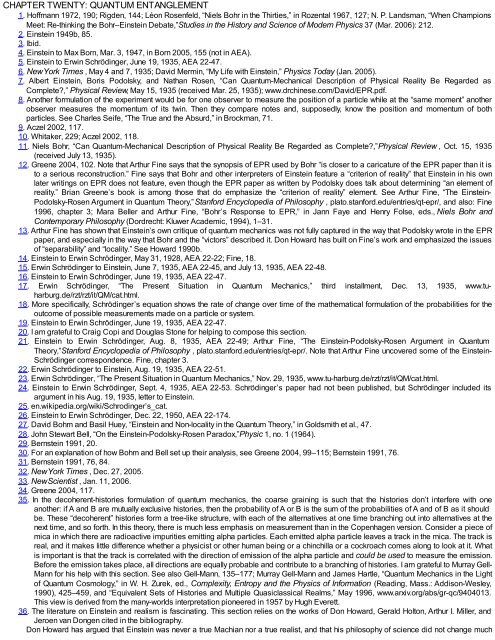

CHAPTER TWENTY: QUANTUM ENTANGLEMENT<br />

1. Hoffmann 1972, 190; Rigden, 144; Léon Rosenfeld, “Niels Bohr in the Thirties,” in Rozental 1967, 127; N. P. Landsman, “When Champions<br />

Meet: Re-thinking the Bohr–Einstein Debate,”Studies in the History and Science of Modern Physics 37 (Mar. 2006): 212.<br />

2. Einstein 1949b, 85.<br />

3. Ibid.<br />

4. Einstein to Max Born, Mar. 3, 1947, in Born 2005, 155 (not in AEA).<br />

5. Einstein to Erwin Schrödinger, June 19, 1935, AEA 22-47.<br />

6. New York Times , May 4 and 7, 1935; David Mermin, “My Life with Einstein,” Physics Today (Jan. 2005).<br />

7. Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky, and Nathan Rosen, “Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Regarded as<br />

Complete?,” Physical Review, May 15, 1935 (received Mar. 25, 1935); www.drchinese.com/David/EPR.pdf.<br />

8. Another formulation of the experiment would be for one observer to measure the position of a particle while at the “same moment” another<br />

observer measures the momentum of its twin. Then they compare notes and, supposedly, know the position and momentum of both<br />

particles. See Charles Seife, “The True and the Absurd,” in Brockman, 71.<br />

9. Aczel 2002, 117.<br />

10. Whitaker, 229; Aczel 2002, 118.<br />

11. Niels Bohr, “Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Regarded as Complete?,”Physical Review , Oct. 15, 1935<br />

(received July 13, 1935).<br />

12. Greene 2004, 102. Note that Arthur Fine says that the synopsis of EPR used by Bohr “is closer to a caricature of the EPR paper than it is<br />

to a serious reconstruction.” Fine says that Bohr and other interpreters of Einstein feature a “criterion of reality” that Einstein in his own<br />

later writings on EPR does not feature, even though the EPR paper as written by Podolsky does talk about determining “an element of<br />

reality.” Brian Greene’s book is among those that do emphasize the “criterion of reality” element. See Arthur Fine, “The Einstein-<br />

Podolsky-Rosen Argument in Quantum Theory,”Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , plato.stanford.edu/entries/qt-epr/, and also: Fine<br />

1996, chapter 3; Mara Beller and Arthur Fine, “Bohr’s Response to EPR,” in Jann Faye and Henry Folse, eds., Niels Bohr and<br />

Contemporary Philosophy (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic, 1994), 1–31.<br />

13. Arthur Fine has shown that Einstein’s own critique of quantum mechanics was not fully captured in the way that Podolsky wrote in the EPR<br />

paper, and especially in the way that Bohr and the “victors” described it. Don Howard has built on Fine’s work and emphasized the issues<br />

of “separability” and “locality.” See Howard 1990b.<br />

14. Einstein to Erwin Schrödinger, May 31, 1928, AEA 22-22; Fine, 18.<br />

15. Erwin Schrödinger to Einstein, June 7, 1935, AEA 22-45, and July 13, 1935, AEA 22-48.<br />

16. Einstein to Erwin Schrödinger, June 19, 1935, AEA 22-47.<br />

17. Erwin Schrödinger, “The Present Situation in Quantum Mechanics,” third installment, Dec. 13, 1935, www.tuharburg.de/rzt/rzt/it/QM/cat.html.<br />

18. More specifically, Schrödinger’s equation shows the rate of change over time of the mathematical formulation of the probabilities for the<br />

outcome of possible measurements made on a particle or system.<br />

19. Einstein to Erwin Schrödinger, June 19, 1935, AEA 22-47.<br />

20. I am grateful to Craig Copi and Douglas Stone for helping to compose this section.<br />

21. Einstein to Erwin Schrödinger, Aug. 8, 1935, AEA 22-49; Arthur Fine, “The Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen Argument in Quantum<br />

Theory,”Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , plato.stanford.edu/entries/qt-epr/. Note that Arthur Fine uncovered some of the Einstein-<br />

Schrödinger correspondence. Fine, chapter 3.<br />

22. Erwin Schrödinger to Einstein, Aug. 19, 1935, AEA 22-51.<br />

23. Erwin Schrödinger, “The Present Situation in Quantum Mechanics,” Nov. 29, 1935, www.tu-harburg.de/rzt/rzt/it/QM/cat.html.<br />

24. Einstein to Erwin Schrödinger, Sept. 4, 1935, AEA 22-53. Schrödinger’s paper had not been published, but Schrödinger included its<br />

argument in his Aug. 19, 1935, letter to Einstein.<br />

25. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schrodinger’s_cat.<br />

26. Einstein to Erwin Schrödinger, Dec. 22, 1950, AEA 22-174.<br />

27. David Bohm and Basil Huey, “Einstein and Non-locality in the Quantum Theory,” in Goldsmith et al., 47.<br />

28. John Stewart Bell, “On the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen Paradox,”Physic 1, no. 1 (1964).<br />

29. Bernstein 1991, 20.<br />

30. For an explanation of how Bohm and Bell set up their analysis, see Greene 2004, 99–115; Bernstein 1991, 76.<br />

31. Bernstein 1991, 76, 84.<br />

32. New York Times , Dec. 27, 2005.<br />

33. New Scientist , Jan. 11, 2006.<br />

34. Greene 2004, 117.<br />

35. In the decoherent-histories formulation of quantum mechanics, the coarse graining is such that the histories don’t interfere with one<br />

another: if A and B are mutually exclusive histories, then the probability of A or B is the sum of the probabilities of A and of B as it should<br />

be. These “decoherent” histories form a tree-like structure, with each of the alternatives at one time branching out into alternatives at the<br />

next time, and so forth. In this theory, there is much less emphasis on measurement than in the Copenhagen version. Consider a piece of<br />

mica in which there are radioactive impurities emitting alpha particles. Each emitted alpha particle leaves a track in the mica. The track is<br />

real, and it makes little difference whether a physicist or other human being or a chinchilla or a cockroach comes along to look at it. What<br />

is important is that the track is correlated with the direction of emission of the alpha particle and could be used to measure the emission.<br />

Before the emission takes place, all directions are equally probable and contribute to a branching of histories. I am grateful to Murray Gell-<br />

Mann for his help with this section. See also Gell-Mann, 135–177; Murray Gell-Mann and James Hartle, “Quantum Mechanics in the Light<br />

of Quantum Cosmology,” in W. H. Zurek, ed., Complexity, Entropy and the Physics of Information (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley,<br />

1990), 425–459, and “Equivalent Sets of Histories and Multiple Quasiclassical Realms,” May 1996, www.arxiv.org/abs/gr-qc/9404013.<br />

This view is derived from the many-worlds interpretation pioneered in 1957 by Hugh Everett.<br />

36. The literature on Einstein and realism is fascinating. This section relies on the works of Don Howard, Gerald Holton, Arthur I. Miller, and<br />

Jeroen van Dongen cited in the bibliography.<br />

Don Howard has argued that Einstein was never a true Machian nor a true realist, and that his philosophy of science did not change much