einstein

einstein

einstein

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

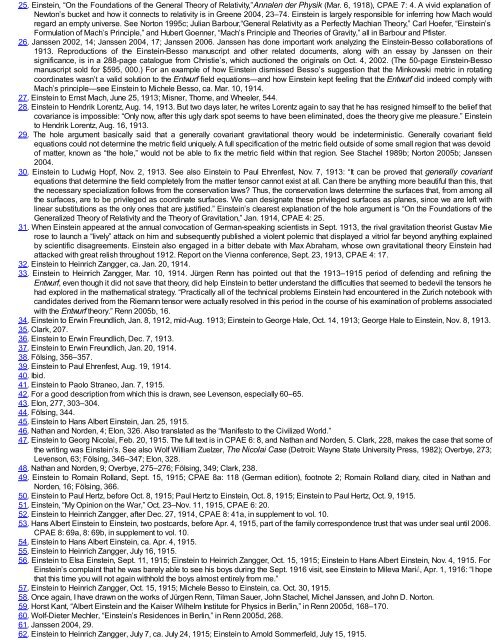

25. Einstein, “On the Foundations of the General Theory of Relativity,”Annalen der Physik (Mar. 6, 1918), CPAE 7: 4. A vivid explanation of<br />

Newton’s bucket and how it connects to relativity is in Greene 2004, 23–74. Einstein is largely responsible for inferring how Mach would<br />

regard an empty universe. See Norton 1995c; Julian Barbour,“General Relativity as a Perfectly Machian Theory,” Carl Hoefer, “Einstein’s<br />

Formulation of Mach’s Principle,” and Hubert Goenner, “Mach’s Principle and Theories of Gravity,” all in Barbour and Pfister.<br />

26. Janssen 2002, 14; Janssen 2004, 17; Janssen 2006. Janssen has done important work analyzing the Einstein-Besso collaborations of<br />

1913. Reproductions of the Einstein-Besso manuscript and other related documents, along with an essay by Janssen on their<br />

significance, is in a 288-page catalogue from Christie’s, which auctioned the originals on Oct. 4, 2002. (The 50-page Einstein-Besso<br />

manuscript sold for $595, 000.) For an example of how Einstein dismissed Besso’s suggestion that the Minkowski metric in rotating<br />

coordinates wasn’t a valid solution to the Entwurf field equations—and how Einstein kept feeling that the Entwurf did indeed comply with<br />

Mach’s principle—see Einstein to Michele Besso, ca. Mar. 10, 1914.<br />

27. Einstein to Ernst Mach, June 25, 1913; Misner, Thorne, and Wheeler, 544.<br />

28. Einstein to Hendrik Lorentz, Aug. 14, 1913. But two days later, he writes Lorentz again to say that he has resigned himself to the belief that<br />

covariance is impossible: “Only now, after this ugly dark spot seems to have been eliminated, does the theory give me pleasure.” Einstein<br />

to Hendrik Lorentz, Aug. 16, 1913.<br />

29. The hole argument basically said that a generally covariant gravitational theory would be indeterministic. Generally covariant field<br />

equations could not determine the metric field uniquely. A full specification of the metric field outside of some small region that was devoid<br />

of matter, known as “the hole,” would not be able to fix the metric field within that region. See Stachel 1989b; Norton 2005b; Janssen<br />

2004.<br />

30. Einstein to Ludwig Hopf, Nov. 2, 1913. See also Einstein to Paul Ehrenfest, Nov. 7, 1913: “It can be proved that generally covariant<br />

equations that determine the field completely from the matter tensor cannot exist at all. Can there be anything more beautiful than this, that<br />

the necessary specialization follows from the conservation laws? Thus, the conservation laws determine the surfaces that, from among all<br />

the surfaces, are to be privileged as coordinate surfaces. We can designate these privileged surfaces as planes, since we are left with<br />

linear substitutions as the only ones that are justified.” Einstein’s clearest explanation of the hole argument is “On the Foundations of the<br />

Generalized Theory of Relativity and the Theory of Gravitation,” Jan. 1914, CPAE 4: 25.<br />

31. When Einstein appeared at the annual convocation of German-speaking scientists in Sept. 1913, the rival gravitation theorist Gustav Mie<br />

rose to launch a “lively” attack on him and subsequently published a violent polemic that displayed a vitriol far beyond anything explained<br />

by scientific disagreements. Einstein also engaged in a bitter debate with Max Abraham, whose own gravitational theory Einstein had<br />

attacked with great relish throughout 1912. Report on the Vienna conference, Sept. 23, 1913, CPAE 4: 17.<br />

32. Einstein to Heinrich Zangger, ca. Jan. 20, 1914.<br />

33. Einstein to Heinrich Zangger, Mar. 10, 1914. Jürgen Renn has pointed out that the 1913–1915 period of defending and refining the<br />

Entwurf, even though it did not save that theory, did help Einstein to better understand the difficulties that seemed to bedevil the tensors he<br />

had explored in the mathematical strategy. “Practically all of the technical problems Einstein had encountered in the Zurich notebook with<br />

candidates derived from the Riemann tensor were actually resolved in this period in the course of his examination of problems associated<br />

with the Entwurf theory.” Renn 2005b, 16.<br />

34. Einstein to Erwin Freundlich, Jan. 8, 1912, mid-Aug. 1913; Einstein to George Hale, Oct. 14, 1913; George Hale to Einstein, Nov. 8, 1913.<br />

35. Clark, 207.<br />

36. Einstein to Erwin Freundlich, Dec. 7, 1913.<br />

37. Einstein to Erwin Freundlich, Jan. 20, 1914.<br />

38. Fölsing, 356–357.<br />

39. Einstein to Paul Ehrenfest, Aug. 19, 1914.<br />

40. Ibid.<br />

41. Einstein to Paolo Straneo, Jan. 7, 1915.<br />

42. For a good description from which this is drawn, see Levenson, especially 60–65.<br />

43. Elon, 277, 303–304.<br />

44. Fölsing, 344.<br />

45. Einstein to Hans Albert Einstein, Jan. 25, 1915.<br />

46. Nathan and Norden, 4; Elon, 326. Also translated as the “Manifesto to the Civilized World.”<br />

47. Einstein to Georg Nicolai, Feb. 20, 1915. The full text is in CPAE 6: 8, and Nathan and Norden, 5. Clark, 228, makes the case that some of<br />

the writing was Einstein’s. See also Wolf William Zuelzer, The Nicolai Case (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1982); Overbye, 273;<br />

Levenson, 63; Fölsing, 346–347; Elon, 328.<br />

48. Nathan and Norden, 9; Overbye, 275–276; Fölsing, 349; Clark, 238.<br />

49. Einstein to Romain Rolland, Sept. 15, 1915; CPAE 8a: 118 (German edition), footnote 2; Romain Rolland diary, cited in Nathan and<br />

Norden, 16; Fölsing, 366.<br />

50. Einstein to Paul Hertz, before Oct. 8, 1915; Paul Hertz to Einstein, Oct. 8, 1915; Einstein to Paul Hertz, Oct. 9, 1915.<br />

51. Einstein, “My Opinion on the War,” Oct. 23–Nov. 11, 1915, CPAE 6: 20.<br />

52. Einstein to Heinrich Zangger, after Dec. 27, 1914, CPAE 8: 41a, in supplement to vol. 10.<br />

53. Hans Albert Einstein to Einstein, two postcards, before Apr. 4, 1915, part of the family correspondence trust that was under seal until 2006.<br />

CPAE 8: 69a, 8: 69b, in supplement to vol. 10.<br />

54. Einstein to Hans Albert Einstein, ca. Apr. 4, 1915.<br />

55. Einstein to Heinrich Zangger, July 16, 1915.<br />

56. Einstein to Elsa Einstein, Sept. 11, 1915; Einstein to Heinrich Zangger, Oct. 15, 1915; Einstein to Hans Albert Einstein, Nov. 4, 1915. For<br />

Einstein’s complaint that he was barely able to see his boys during the Sept. 1916 visit, see Einstein to Mileva Mari , Apr. 1, 1916: “I hope<br />

that this time you will not again withhold the boys almost entirely from me.”<br />

57. Einstein to Heinrich Zangger, Oct. 15, 1915; Michele Besso to Einstein, ca. Oct. 30, 1915.<br />

58. Once again, I have drawn on the works of Jürgen Renn, Tilman Sauer, John Stachel, Michel Janssen, and John D. Norton.<br />

59. Horst Kant, “Albert Einstein and the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics in Berlin,” in Renn 2005d, 168–170.<br />

60. Wolf-Dieter Mechler, “Einstein’s Residences in Berlin,” in Renn 2005d, 268.<br />

61. Janssen 2004, 29.<br />

62. Einstein to Heinrich Zangger, July 7, ca. July 24, 1915; Einstein to Arnold Sommerfeld, July 15, 1915.