From Colonization to Globalization - Kwantlen Polytechnic University

From Colonization to Globalization - Kwantlen Polytechnic University

From Colonization to Globalization - Kwantlen Polytechnic University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Copyright © 2011 by KWAME NKRUMAH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE<br />

EDITORS: Charles Quist-Adade and Frances Chiang<br />

ISBN: 978-1-926652-16-0<br />

All rights reserved.<br />

No part of this material may be translated, reproduced, s<strong>to</strong>red or transmitted in any manner<br />

whatsoever without the written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations in<br />

critical articles and reviews.<br />

For information contact the publisher at info@dayspringspublishing.com<br />

PUBLISHED AND DISTRIBUTED<br />

BY DAYSPRINGS PUBLISHING<br />

IN ASSOCIATION WITH KWAME NKRUMAH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE.<br />

Printed and bound in Canada.<br />

First edition September, 2011

Articles and Speeches Presented at the Kwame Nkrumah International Conference held at<br />

<strong>Kwantlen</strong> <strong>Polytechnic</strong> <strong>University</strong>, Richmond BC Campus, in August 2010.<br />

<strong>From</strong> <strong>Colonization</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Globalization</strong><br />

Edited by Charles Quist-Adade, PhD and Frances Chiang, PhD<br />

<strong>Kwantlen</strong> <strong>Polytechnic</strong> <strong>University</strong>, Surrey, BC, Canada<br />

Correspondence: Address all correspondence <strong>to</strong>: info@dayspringspublishing.com<br />

5 PREFACE<br />

7 WELCOME ADDRESS AT THE OPENING CEREMONY<br />

Charles Quist-Adade, Conference Co-Organizer & Contributing Edi<strong>to</strong>r<br />

12 THE CHARACTER OF KWAME NKRUMAH’S UNITED AFRICA VISION<br />

MOLEFI KETE ASANTE<br />

23 ‘AFRICA MUST UNITE:’ VINDICATING KWAME NKRUMAH AND UNITING<br />

AFRICA AGAINST GLOBAL DESTRUCTION<br />

HENRY KAM KAH<br />

34 RECLAIMING OUR AFRICANNESS IN THE DISAPORIZED CONTEXT: THE<br />

CHALLENGE OF ASSERTING A CRITICAL AFRICAN PERSONALITY<br />

GEORGE J. SEFA DEI<br />

45 FROM NKRUMAH TO NEPAD AND BEYOND: HAS ANYTHING CHANGED?<br />

CATHERINE SCHITTECATTE<br />

60 KWAME NKRUMAH’S MISSION AND VISION FOR AFRICA AND THE WORLD<br />

VINCENT DODOO<br />

71 SOVEREIGNTY AND THE AFRICAN UNION<br />

LEILA J. FARMER<br />

80 PAN-AFRICAN CONFERENCES, 1900 – 1953:<br />

WHAT DID ‘PAN-AFRICANISM’ MEAN?<br />

MARIKA SHERWOOD<br />

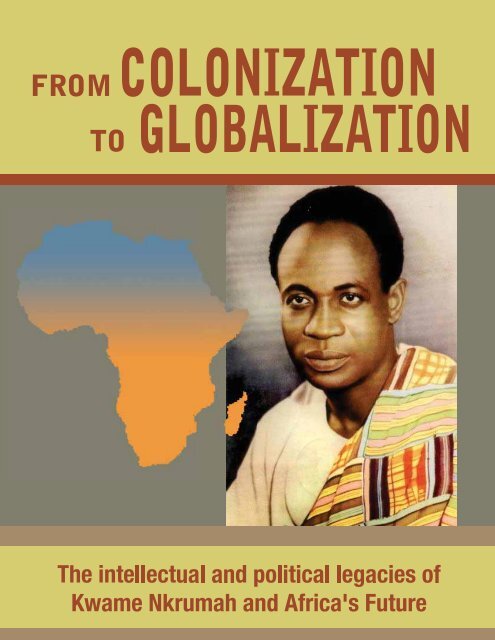

94 THE INTELLECTUAL AND POLITICAL LEGACIES OF KWAME NKRUMAH<br />

AMA BINEY<br />

105 FESTIVAL AS AN EDUCATIONAL EXPERIENCE:<br />

THE AFRICAN CULTURAL MEMORY YOUTH ARTS FESTIVAL (ACMYAF)<br />

PETER MBAGO WAKHOLI<br />

118 EMERGING ENVIRONMENTAL POLITICS: AFRICA’S SAVING GRACE?<br />

JULIA BERRY<br />

125 FROM THE TEMPLES OF EGYPT TO EMPEROR HAILE SELASSIE'S<br />

PAN-AFRICAN UNIVERSITY<br />

JOHN K. MARAH

146 PERSPECTIVES ON AFRICAN DECOLONIZATION AND DEVELOPMENT:<br />

THE CASE OF KENYA<br />

OMOSA MOGAMBI NTABO AND KENNEDY ONKWARE<br />

155 50 YEARS OF KISWAHILI IN REGIONAL<br />

AND INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT<br />

SUSAN CHEBET-CHOGE, M.PHIL<br />

178 FORGING SPACES AND READING ACROSS BOUNDARIES<br />

RASHNA SINGH<br />

184 THE UNITED STATES PEACE CORPS AS A FACET OF<br />

UNITED STATES-GHANA RELATIONS<br />

E. OFORI BEKOE, MA<br />

193 THE EPIPHANY OF UBUNTU IN KNOWLEDGE DEVELOPMENT:<br />

AN AFRICAN WAY<br />

RAMADIMETJA SHIRLEY MOGALE,<br />

199 THE ROLE OF THE DECOLONIZATION COMMITTEE OF THE UNITED<br />

NATIONS ORGANIZATION IN THE STRUGGLE AGAINST PORTUGUESE<br />

COLONIALISM IN AFRICA: 1961-1974<br />

AURORA ALMADA E SANTOS<br />

210 BEYOND THE IDEOLOGY OF ‘CIVIL WAR’:<br />

THE GLOBAL-HISTORICAL CONSTITUTION OF POLITICAL<br />

VIOLENCE IN SUDAN<br />

ALISON J. AYERS<br />

229 WOMEN AND DEMOCRATIZATION IN WEST AFRICA:<br />

THE CASE OF CADD, A COMMUNITY-BASED GROUP FOCUSING ON<br />

CONSUMPTION ISSUES.<br />

CHARLES BELANGER<br />

239 ENEMIES TO ALLIES?<br />

THE DYNAMICS OF RWANDA-CONGO MILITARY, ECONOMIC AND<br />

DIPLOMATIC RELATIONS<br />

GREG QUEYRANNE<br />

244 RACIALIZATION OF ASIA, AFRICA AND AMERICAS AND THE<br />

CONSTRUCTION OF THE IDEAL IRANIAN CITIZEN: LOCAL AND GLOBAL<br />

REPRESENTATIONS OF COLONIALISM, GEOGRAPHY, CULTURE AND<br />

RELIGIOUS DIVERSITY IN IRANIAN SCHOOL TEXTBOOKS<br />

AMIR MIRFAKHRAIE

PREFACE<br />

Once again, Africa is the site of political<br />

ferment and external power interference.<br />

Recent events in the north of Africa, starting<br />

with Tunisia, then Egypt and leading <strong>to</strong> the socalled<br />

‘Arab-Spring’ has reinforced the pivotal<br />

role this continent plays in world affairs. On<br />

one hand, it is a marginalized and virtually<br />

ignored continent in world forums, yet on the<br />

other hand, it carries significant weight in the<br />

plans for global dominance and control by<br />

several western and non-western countries. In<br />

almost the same breath that many non-African<br />

nations speak disparagingly about the<br />

continent, they hatch plans <strong>to</strong> further retain<br />

control of its resources and peoples,<br />

emphasizing its strategic relevance for their<br />

future economic and political survival. Africa, it<br />

seems, is a land of contradictions, so poor and<br />

yet so rich.<br />

THE CONFERENCE<br />

In August 2010, over 120 participants from<br />

four continents, gathered <strong>to</strong> share ideas and<br />

knowledge about the political and intellectual<br />

legacies of Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, especially as it<br />

applies <strong>to</strong> Africa. It is often said that Kwame<br />

Nkrumah is one of the greatest political leaders<br />

the African continent has ever had, standing on<br />

the same plane as other ‘greats’ like Jomo<br />

Kenyatta and Nelson Mandela. On the<br />

centennial anniversary of his birth, it comes as<br />

no surprise that African leaders and<br />

intellectuals would come <strong>to</strong>gether <strong>to</strong> discuss<br />

his impact and legacy on the African continent,<br />

especially so considering recent global turmoils<br />

and sense of a lack of direction worldwide.<br />

Participants at the conference included the<br />

Temple <strong>University</strong> Professor, Molefi Kete<br />

Asante, one of the most distinguished<br />

contemporary scholars, as well as the<br />

author/co-author and edi<strong>to</strong>r of no less than 70<br />

books and scholarly articles—who provided<br />

the keynote address in celebration of the<br />

conference, <strong>to</strong>gether with other scholars of<br />

similar calibre and talent in the context(s) of<br />

Pan-Africanism, post/neo-colonialism and<br />

globalization via a cross-disciplinary, multicentric,<br />

and international perspectives.<br />

The overarching objective of the Kwame<br />

Nkrumah International Conference (KNIC) was<br />

<strong>to</strong> provide an avenue for the creation and<br />

sharing of knowledge on ways <strong>to</strong> break Africa’s<br />

cycle of underdevelopment, and proposals for

Thank you all Seema, Farhad, and John for the<br />

kind words.<br />

While I would reserve my thanks <strong>to</strong> the long list<br />

of helpers and enablers <strong>to</strong> the closing<br />

ceremony, I cannot resist the temptation <strong>to</strong><br />

thank my colleague, Dr. Frances Chiang, who<br />

more than anyone else, helped me in planning<br />

and executing this conference. For the past two<br />

years Dr. Chiang, in a display of extraordinary<br />

patience and dodged determination has stuck<br />

with me through thick and thin, through<br />

moments of despair and disappointments,<br />

frustration and anguish <strong>to</strong> the logical end.<br />

Frances, I am grateful <strong>to</strong> you. You are one of the<br />

most dependable and trustworthy persons I<br />

have ever met.<br />

I also think it is important <strong>to</strong> render special<br />

thanks <strong>to</strong> the Social Science and Humanities<br />

Research Council of Canada, <strong>Kwantlen</strong>’s Office<br />

of Research and Scholarship and the Centre for<br />

Academic Growth whose generous grants made<br />

it possible for us <strong>to</strong> invite our keynote and<br />

plenary speakers. Lastly, I thank my family for<br />

their patience and <strong>to</strong>lerance. For the past two<br />

<strong>From</strong> <strong>Colonization</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Globalization</strong><br />

Welcome Address by Charles Quist-Adade<br />

years they have had more than their fill of my<br />

obsessive pre-occupation and the only string in<br />

my conversational violin—KNIC. Geralda,<br />

Maayaa, Chris<strong>to</strong>pher, and Malaika, thank you<br />

for your <strong>to</strong>lerance and most of all your<br />

encouragement. I am thankful <strong>to</strong> you.<br />

This conference will probably be the last event<br />

in the year-long series of activities around the<br />

world <strong>to</strong> commemorate the centenary<br />

anniversary of the birth of Dr. Kwame Nkrumah,<br />

Africa’s Man of the Millennium and perhaps the<br />

most famous pan-Africanist after Marcus<br />

Garvey and W. E. B. Du Bois. It is noteworthy<br />

that the conference is being held at the<br />

confluence of the anniversaries of several<br />

monumental events in Africa, the most<br />

important of which is the fiftieth anniversary of<br />

what is popularly referred <strong>to</strong> as “The Year of<br />

Africa.”<br />

The year 1960 witnessed a host of events,<br />

including the end of the Mau Mau resistance in<br />

Kenya, mass riots during Charles de Gaulle’s trip<br />

<strong>to</strong> Algeria, the murder of sixty-nine non-violent<br />

protes<strong>to</strong>rs in South Africa’s Sharpeville

Dr. Molefi Kete Asante is<br />

Professor, Department of<br />

African American Studies at<br />

Temple <strong>University</strong>.<br />

Asante has been recognized<br />

as one of the ten most<br />

widely cited African<br />

Americans. In the 1990s,<br />

Black Issues in Higher<br />

Education recognized him<br />

as one of the most<br />

influential leaders in the<br />

decade.<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

I would like <strong>to</strong> give thanks <strong>to</strong> the ances<strong>to</strong>rs, according <strong>to</strong> our tradition,<br />

and <strong>to</strong> Professor Quist Adade for this invitation. This conference of<br />

outstanding scholars, colleagues, and students will represent a<br />

watershed in the discourse on Nkrumah’s vision and I am pleased <strong>to</strong> be<br />

a small part of this discourse. My paper examines the prospects and<br />

possibilities of world peace inherent in Nkrumah’s vision of a United<br />

States of Africa. In effect, an Africa, freed from the vestiges of<br />

colonialism in all of its dimensions; economic, philosophical, and<br />

cultural, would lead <strong>to</strong> stability on the continent and remove it,<br />

especially in its fragmented reality as nation-states, from being a hotly<br />

contested region for international political maneuvers. Nkrumah’s<br />

vision was political but also more than political; it was also cultural and<br />

philosophical, and in his terms, Afro-centric.<br />

This is the meaning of Nkrumah’s proposals for a new African<br />

personality, one loosed from an attachment <strong>to</strong> European and<br />

American cultural entanglements. Thus, my paper outlines the<br />

practical arguments for the United States of Africa and demonstrates<br />

how the resources of Africa are best preserved by a common external<br />

policy and an integrated continental market. Ultimately, I would like<br />

<strong>to</strong> re-iterate the Nkrumahist’s vision and announce his advanced<br />

thinking for our era.<br />

THE CHARACTER OF KWAME NKRUMAH’S UNITED AFRICA VISION<br />

MOLEFI KETE ASANTE

Henry Kam Kah<br />

<strong>University</strong> of Buea, Cameroon<br />

Email: ndangso@yahoo.com<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

Over fifty years ago the prophetic Kwame Nkrumah called for and<br />

wrote a book titled Africa must Unite. Many self-seeking African<br />

leaders described him as a dreamer of impossibility. A few<br />

decades after his clarion call, some European countries created<br />

the European Union (EU) for their greater unity, collective benefit<br />

and for providing global leadership. Since then, American and<br />

Asian states have also come <strong>to</strong>gether, challenges<br />

notwithstanding. Africa is yet <strong>to</strong> make any meaningful progress<br />

<strong>to</strong>wards a union government in spite of public acknowledgement<br />

of this need by some of its leaders. The foot-dragging approach in<br />

the unification of Africa has given rise <strong>to</strong> rapid westernisation in<br />

the guise of globalisation <strong>to</strong> ‘squeeze the hell’ out of the<br />

continent in virtually all domains of existence. In the midst of<br />

these aggressive efforts, Nkrumah’s visionary appeal is more<br />

pertinent and imperative <strong>to</strong>day in the face of a weak African<br />

socio-economic and political base. The time <strong>to</strong> unite is now and<br />

there is excuse for continuous rhe<strong>to</strong>ric. This paper examines the<br />

salience of Kwame Nkrumah’s clarion call for a United Africa and<br />

why this should be embraced forthwith by the sceptical<br />

leadership and people of Africa both on the continent and in the<br />

diaspora.

George J. Sefa Dei<br />

Sociology and Equity Studies<br />

<strong>University</strong> of Toron<strong>to</strong><br />

george.dei@u<strong>to</strong>ron<strong>to</strong>.ca<br />

ABSTRACT:<br />

In the annals of African and Black peoples his<strong>to</strong>ry, and<br />

particularly anti-colonial nationalist politics, Nkrumah remains<br />

in a unique position as a nationalist and anti-colonialist who<br />

pioneered a struggle for Independence for the first Black nation<br />

on the continent. Given the post-colonial challenges facing<br />

African peoples <strong>to</strong>day, African intellectuals <strong>to</strong>day have a<br />

responsibility <strong>to</strong> revisit some of his pioneering ideas as we seek<br />

<strong>to</strong> design our own futures. To revisit Nkrumah is more than<br />

about a ‘return <strong>to</strong> the source’ i.e., Sankofa’. It is also about <strong>to</strong><br />

return <strong>to</strong> the source <strong>to</strong> listen, learn, and hear that is ‘Sankotie’<br />

and Sankowhe’ (see Aikins 2010). This paper would borrow<br />

from the philosophy and ideas of Nkrumah as we rethink how<br />

African peoples can design their own futures in the area of<br />

schooling and education. I centre the possibilities Pan-African<br />

spirituality as a base/sub structure on which rest the<br />

possibilities of community building. I focus on Pan-African<br />

spirituality as resistance <strong>to</strong> the disembodiment and<br />

dismemberment in Diasporic contexts. In so doing, I will also<br />

seek <strong>to</strong> draw connections of Afrocentricity and Pan-African<br />

struggles <strong>to</strong> highlight the challenge and promise of African<br />

agency.

© DR. CATHERINE SCHITTECATTE<br />

VANCOUVER ISLAND UNIVERSITY,<br />

BRITISH COLUMBIA<br />

Chair of both Political Science and<br />

the Global Studies Program<br />

Prepared for the<br />

Kwame Nkrumah International<br />

Conference<br />

<strong>Kwantlen</strong> <strong>University</strong>,<br />

British Columbia<br />

August 19-21, 2010<br />

CATHERINE SCHITTECATTE<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

Kwame Nkrumah’s foresight lay in his understanding that his<strong>to</strong>rical<br />

and global patterns of exploitation would not be easily broken in<br />

post-independence Africa. Given that understanding of Africa’s<br />

situation, many of his policies, from domestic development plans<br />

<strong>to</strong> Pan-Africanism, were intended <strong>to</strong> gain not only political but,<br />

most importantly, economic independence for Ghana and the<br />

continent. These views were related <strong>to</strong> Africa’s position in the<br />

global economy and, in particular, its economic ties <strong>to</strong> the West.<br />

As such, a second aspect of that vision was the ability of the newly<br />

independent continent <strong>to</strong> de-link itself from past colonial masters<br />

and new neo-colonial ones. A third related and most significant<br />

component was the strength and feasibility of a unified continent.<br />

The complexity, wealth and foresight of Nkrumah’s analysis of<br />

Africa’s needs leave us a valuable framework with which <strong>to</strong><br />

understand the challenges and related solutions for Africa.<br />

The paper explores several questions related <strong>to</strong> that framework.<br />

As such, after providing some his<strong>to</strong>rical background in terms of<br />

Nkrumah’s thinking and policies, the paper seeks <strong>to</strong> assess ways in<br />

which the global context, foreign interests and related responses<br />

in Africa have changed since his days in office. Where is the<br />

continent <strong>to</strong>day, relative <strong>to</strong> that analysis and Nkrumah’s related<br />

policy recommendations? Since the New Partnership for Africa’s<br />

Development (NEPAD) was launched in 2001, many have praised<br />

or criticized the extent <strong>to</strong> which this document would represent a<br />

break with the past. More specifically, the focus is on Sub Saharan<br />

Africa, natural resource exploitation and foreign investments. The<br />

paper begins with a brief discussion of some exogenous and<br />

endogenous fac<strong>to</strong>rs of underdevelopment and Nkrumah’s position<br />

relative <strong>to</strong> these. These highlights of Nkrumah’s responses and<br />

visions for the continent are then compared <strong>to</strong> NEPAD’s process,<br />

objectives and aspirations in the context of potential “new<br />

partners” in African development.<br />

FROM NKRUMAH TO NEPAD AND BEYOND: HAS ANYTHING CHANGED?<br />

CATHERINE SCHITTECATTE

Vincent Dodoo<br />

Department of His<strong>to</strong>ry and Political<br />

Studies<br />

Social Sciences Faculty, Kwame Nkrumah<br />

<strong>University</strong> of Science & Technology.<br />

Kumasi, Ghana.<br />

vincentjon2006@yahoo.ca<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

Kwame Nkrumah had a vision not only for Africa but also the<br />

whole world. He foresaw the imminence of a unified world in<br />

which all sec<strong>to</strong>rs of society would have no choice but <strong>to</strong> work<br />

<strong>to</strong>gether. His vision and mission then was <strong>to</strong> prepare Africa for<br />

the task of playing a role in this approaching unified world<br />

society, not as a subordinate continent but as an equal and<br />

dignified member and partner. To achieve this, there was a need<br />

<strong>to</strong> dismantle the structures of colonialism and put in their place<br />

new structures <strong>to</strong> support local aspirations in order <strong>to</strong> promote<br />

development and create a conducive environment, in which the<br />

individual could operate. Nkrumah’s point of departure was the<br />

newly created independent state, Ghana, from where he would<br />

move in<strong>to</strong> Africa and, thereafter, in<strong>to</strong> the world. Nkrumah’s<br />

thinking, therefore, operated at three levels. He began from the<br />

concerns of the individual, moved on <strong>to</strong> address issues of the subsystemic<br />

which was the state and finally settled on the systemic<br />

which is the continent Africa and thereafter the world. He<br />

recognized the need <strong>to</strong> create a conducive atmosphere for all<br />

three <strong>to</strong> function freely in order <strong>to</strong> attain the desired goal of<br />

equal players in a unified world society. Nkrumah had absorbed<br />

from the teaching of Dr. James Eman Kwegyir Aggrey, as can be<br />

seen later in this paper, the metaphor of the piano with its black<br />

and white keys, <strong>to</strong>gether creating harmony and he used that <strong>to</strong><br />

demonstrate the potential of the African in the unified world<br />

society.<br />

Keywords: Colonialism, African development and unity, Unified world<br />

society.

LEILA J. FARMER<br />

FARMERL@UVIC.CA<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

This paper discusses way the principle of sovereignty<br />

influenced the ideological framework of the Organization of<br />

African Unity (OAU) and its successor, the African Union<br />

(AU). While both the OAU and the AU represent the<br />

institutionalization of Pan-Africanism, this paper argues that<br />

by entrenching the notion of popular sovereignty in its<br />

constitution and peace and security institutions, the AU has<br />

a greater capacity <strong>to</strong> achieve the ideals of Pan-Africanism.<br />

SOVEREIGNTY AND THE AFRICAN UNION<br />

LEILA J. FARMER

Marika Sherwood is a founder<br />

member of the Black & Asian<br />

Studies Association & edi<strong>to</strong>r of<br />

the BASA Newsletter.<br />

The author of numerous books<br />

and articles on the his<strong>to</strong>ry of<br />

black peoples in the UK, as<br />

well as on education, she is<br />

honorary senior research<br />

fellow at the Institute of<br />

Commonwealth Studies,<br />

<strong>University</strong> of London<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

The concerns of Pan-Africanists, their philosophies and politics<br />

naturally depended on the times they were living in .<br />

Nevertheless the call for unity, whether overt or implied has<br />

been there for well over a century. This need was perhaps<br />

easier <strong>to</strong> espouse when the proposal was for unity against the<br />

imperialist oppressors. Once this was obtained (though it is<br />

quite reasonable <strong>to</strong> argue that it is still there, in new forms), the<br />

issue became – and is - far more complex and complicated.<br />

Another complication that arose with independence is the<br />

whole issue of ‘nationalism’. After all, the countries of Africa<br />

were created in Berlin by Europeans who ignored existing<br />

empires/kingdoms/polities, languages, traditions, religions,<br />

cultures: how is a new nation <strong>to</strong> be created from the plethora of<br />

many peoples whose his<strong>to</strong>ries vis-à-vis each other were often<br />

‘problematic’? Or, in the name of African unity, should the<br />

boundaries be withdrawn? But then how would you administer<br />

– and whom?<br />

This paper will examine the meaning of ‘pan-Africanism’ as<br />

espoused at the at the 1900 and 1945 Pan-African Conference,<br />

and by the West African National Secretariat, Kwame Nkrumah<br />

and George Padmore, until and including pan-African<br />

conference in Kumasi in 1953.<br />

PAN-AFRICAN CONFERENCES, 1900 – 1953: WHAT DID ‘PAN-AFRICANISM’ MEAN?<br />

MARIKA SHERWOOD

Ama Biney<br />

Paper presented at the<br />

Kwame Nkrumah<br />

International Conference at<br />

<strong>Kwantlen</strong> <strong>Polytechnic</strong> from<br />

19 – 21 August 2010<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

AMA BINEY<br />

My paper is entitled: “What are the intellectual and political<br />

legacies of Kwame Nkrumah?” and I wish <strong>to</strong> speak directly <strong>to</strong><br />

this question.<br />

Integral <strong>to</strong> Kwame Nkrumah’s vision of Pan-Africanism was the<br />

concept of Continental Union Government for Africa. Nkrumah<br />

was one of several leading radical Pan-Africanists of the 1960s<br />

such as Julius Nyerere, Modibo Keita, Patrice Lumumba, and<br />

Sékou Touré. Aside from his passionate commitment <strong>to</strong> building<br />

and realising Continental unity, Nkrumah’s prolific written work<br />

and speeches contain other equally important bequests. These<br />

intellectual and political legacies are the focus of this article. For<br />

analytical purposes, whilst the two i.e. the intellectual and the<br />

political are inextricably linked, they will be interrogated<br />

separately. They shall be examined in no order of priority. The<br />

objective of this article is <strong>to</strong> critically examine these legacies and<br />

illustrate their continuing relevance <strong>to</strong> acute developmental<br />

problems and issues confronting Africans <strong>to</strong>day.

Peter Mbago Wakholi<br />

is a<br />

PhD Candidate at<br />

Murdoch <strong>University</strong>,<br />

Western Australia<br />

ABSTRACT :<br />

This paper is based on the author’s PhD project, and is<br />

located amongst youth of African migrant descent in<br />

Western Australia. It was an arts-based project through<br />

which young people of African background were involved in<br />

theatrical events as a means of exploring issues relating <strong>to</strong><br />

their bicultural socialization and identities. The paper<br />

discusses the methodological application of arts-based<br />

approaches and African-centred pedagogy in the<br />

exploration of African Cultural Memory as a relevant<br />

context for developing African cultural literacy as a pathway<br />

<strong>to</strong>wards bicultural socialization and competence.

JULIA BERRY<br />

The <strong>University</strong> of Vic<strong>to</strong>ria,<br />

Undergraduate Studies<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

This paper considers the emerging political interest in<br />

environment and climate change by African nations. Pollution<br />

and the effects of climate change are trans-boundary and the<br />

effects will be harder felt in different regions of Africa. The<br />

changing climate will test the legitimacy and strength of the<br />

African Union for decades <strong>to</strong> come. The continent must<br />

balance economic development and social development in a<br />

way that will not be environmental destructive nor exasperate<br />

the current social inequalities. Africa has a rare opportunity <strong>to</strong><br />

learn from the developed world’s mistake and be at the<br />

forefront of sustainable development. What’s more, many<br />

solutions for Africa’s poverty and underdevelopment are one<br />

in the same as the opportunities <strong>to</strong> ensure a prosperous and<br />

sustained future. These solutions, however, will only be<br />

successful if Pan-African regulations and behaviour<br />

constraints are in place and enforced. The world is on the<br />

cusp of a global social movement <strong>to</strong>wards sustainability and<br />

Africa is in the unique position of shaping the global<br />

perception of sustainable development.<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

EMERGING ENVIRONMENTAL POLITICS: AFRICA’S SAVING GRACE?<br />

JULIA BERRY

By Dr. John K. Marah<br />

AAS Department<br />

SUNY College at Brockport<br />

Brockport, New York 14420<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

A Short His<strong>to</strong>ry of African Education<br />

This article represents an attempt at a general his<strong>to</strong>ry of African<br />

education from ancient times <strong>to</strong> the modem day attempts at<br />

institutionalizing 'Pan-African' education (Marah 1989). As all<br />

general his<strong>to</strong>ry, emphasis is placed on sweeping, Pan-African<br />

experiences of African people in Africa and the United States of<br />

America; such an effort necessarily leaves out parochial or<br />

particularized interests or subsets of African people's education.<br />

This general his<strong>to</strong>rical treatment of African people's education,<br />

as sweeping as it is, has its own merits; it allows us <strong>to</strong> see Africa<br />

from a global perspective and it affirms that African people's<br />

educations have not always been in the hands of Arabs.<br />

Europeans, and Americans; it substantiates further that African<br />

people themselves have always had unabated interests in their<br />

own educations, from. the temples of Egypt <strong>to</strong> modem day<br />

popularized educational systems, Furthermore; this Pan-African<br />

treatment of African people's education could motivate a 'few<br />

scholars and students <strong>to</strong> examine how and where their own<br />

peculiar interests in African people's education fit in<strong>to</strong> the longer<br />

picture. Lastly, as nations begin <strong>to</strong> gather in<strong>to</strong> larger and larger<br />

economic arid political units (U.S.A., Mexico, and Canada; China,<br />

Hong Kong and Macao; United Western Europe, etc.), African<br />

people must also (begin <strong>to</strong>) see themselves from a Pan-African<br />

perspective; this is why this attempt is not without merits.

Omosa Mogambi Ntabo 1 and Kennedy<br />

Onkware 2<br />

1. Dept. of Criminology and Social Work<br />

2. Dept. of Peace and Conflict Studies<br />

Masinde Muliro <strong>University</strong> of Science and<br />

Technology, Kenya<br />

KEY WORDS:<br />

Development, decolonization, modernization,<br />

dependency, independence

Susan Chebet-Choge, M.Phil<br />

susanchoge@gmail.com<br />

Lecturer, Dept of Language and<br />

Literature Education<br />

Masinde Muliro <strong>University</strong> of Science<br />

& Technology, Kenya<br />

P.O Box, 190, 50100<br />

Kakamega, Kenya<br />

Paper presented at<br />

Kwame Nkrumah International<br />

Conference @ <strong>Kwantlen</strong> <strong>Polytechnic</strong><br />

<strong>University</strong>, Richmond Campus, Canada.<br />

19-21 August 2010<br />

oge, M.Phil<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

Kiswahili is undoubtedly one of the most developed and<br />

expansively used indigenous African languages nationally and<br />

internationally. At the dawn of African states political<br />

independence, the founding fathers of the nations led by<br />

Kwame Nkrumah considered Kiswahili as an appropriate<br />

language for African states unity. Adoption of Kiswahili as the<br />

universal language of African continent could have gone<br />

along way in realising the dream of the founding fathers of<br />

one people, one nation, one language. However, as his<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

bears witness, their dream remained just a wish. On the<br />

contrary, Kiswahili, though not accorded Africa continent<br />

political recognition, has continued with its linguistic<br />

conquest and expansion further from its indigenous base in<br />

the East Africa’s coast <strong>to</strong> various countries in Africa and<br />

beyond. The status and usage of Kiswahili has shifted and<br />

grown with the political, social and economic growth of<br />

nations which use it for various purposes. Currently, it is a<br />

regional language in East African countries where it wears<br />

several hats as a vernacular, national & official language,<br />

lingua franca and a vehicular in various spheres of life.<br />

Internationally, Kiswahili has curved for itself a linguistic<br />

sphere in the field of academia and international<br />

communication. This paper therefore seeks <strong>to</strong> document and<br />

asses Kiswahili’s participation in the last fifty years in<br />

national, regional and international developments.

ABSTRACT<br />

This paper presents a pedagogical as well as a critical<br />

conundrum. How do we read across cultures without<br />

assuming our own cultural centricity or presuming our own<br />

exceptionalism? How do we read novels from countries or<br />

cultures very different from our own without rendering the<br />

protagonist an ‘Other’ or exiling these works <strong>to</strong> an<br />

oppositional, ‘outsider’ space which we find impossible <strong>to</strong><br />

traverse? In an interview in Diacritics with Leonard Green in<br />

1982, Fredric Jameson points out that undergraduates<br />

never confront a text in all its material freshness but bring<br />

<strong>to</strong> it a set of "previously acquired and culturally sanctioned<br />

interpretive schemes, of which they are unaware, and<br />

through which they read the texts that are proposed <strong>to</strong><br />

them” (73). While the reading of novels is a specialized and<br />

even an elite activity Jameson argues, the ideologies in<br />

which people are trained when they read and interpret<br />

novels are not specialized at all, but rather the working<br />

attitude and forms of the conceptual legitimization of this<br />

society” (73). How might we resist colonizing readings of<br />

literary texts, particularly those of the ‘Third World?’<br />

Nigerian feminist and literary critic Molara Ogundipe-Leslie<br />

writes in the dedication <strong>to</strong> Moving Beyond Boundaries:<br />

For all the women of the world<br />

through the women of the African diasporas<br />

wherever we are<br />

that we may hold hands in action<br />

across some necessary boundaries.<br />

FORGING SPACES AND READING ACROSS BOUNDARIES<br />

RASHNA SINGH

E. Ofori Bekoe, MA<br />

The College of New Rochelle<br />

Rosa Parks Campus-New York<br />

ebekoe@cnr.edu<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

The Peace Corps, established by the Kennedy Administration,<br />

became an important foreign policy instrument for US-Ghana<br />

relations during the nascent stages of Ghana’s post-independence<br />

democracy. As the first country <strong>to</strong> be a beneficiary <strong>to</strong> the program,<br />

President Kwame Nkrumah was initially skeptical of this U.S.<br />

foreign policy, but eventually warmed up <strong>to</strong> the concept. In this<br />

paper, I will explore some underlying fac<strong>to</strong>rs that contributed <strong>to</strong><br />

the eventual transformation of the Peace Corps in<strong>to</strong> an important<br />

element of bilateral collaboration and partnership for both the<br />

United States and Ghana during the Nkrumah administration. I will<br />

also discuss important formative flashpoints that led <strong>to</strong> the<br />

inauguration of the program starting from the speech given by John<br />

F. Kennedy at the <strong>University</strong> of Michigan at Ann Arbor through the<br />

Cow Palace official proclamation in San Francisco and the ensuing<br />

diversity of trainings that the earlier volunteers participated in. All<br />

these chronological analyses are constructed within a broader<br />

geopolitical purview which emphasizes the realist power<br />

contentions that characterized the Cold War East-West political<br />

dicho<strong>to</strong>my. The question undergirding this paper, then, is: Was the<br />

Peace Corps a Cold War foreign policy instrument critical <strong>to</strong> the<br />

execution of United States’ proxy wars with the Soviets or was it a<br />

foreign policy crafted solely for the altruistic purpose of carrying<br />

out humanitarian assistance in Third World nations or was it<br />

intended <strong>to</strong> serve both?<br />

THE UNITED STATES PEACE CORPS AS A FACET OF UNITED STATES-GHANA RELATIONS<br />

E. OFORI BEKOE

Ramadimetja Shirley<br />

Mogale, PhD student<br />

<strong>University</strong> of Alberta,<br />

Faculty of Nursing,<br />

Edmon<strong>to</strong>n, Canada<br />

RAMADIMETJA SHIRLEY MOGALE<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

In this presentation, I address my internal conflicts as an<br />

African who left my great continent with the hope of gaining<br />

knowledge at a large North American <strong>University</strong>. I am now<br />

facing the dilemma of acquiring knowledge of Western origins<br />

as part of a doc<strong>to</strong>ral program in nursing even though I already<br />

possess unique knowledge originating from Africa. I am<br />

investigating the on<strong>to</strong>logical and epistemological stances<br />

regarding nursing practice in Africa as my professional identity<br />

vis-à-vis my African heritage. I am also reflecting on the<br />

development of my knowledge which helped me <strong>to</strong> recall my<br />

African ways of knowing and learning despite the fact that they<br />

were deemed unscientific.<br />

THE EPIPHANY OF UBUNTU IN KNOWLEDGE DEVELOPMENT: AN AFRICAN WAY<br />

RAMADIMETJA SHIRLEY MOGALE

Aurora Almada e San<strong>to</strong>s<br />

(auroraalmada@yahoo.com.br) is a<br />

PhD student at the Contemporary<br />

His<strong>to</strong>ry Institute of the New<br />

<strong>University</strong> of Lisbon, Portugal.<br />

She is interested in the diplomatic<br />

activity of the national liberation<br />

movements of Portuguese colonies<br />

in the United Nation Organization.<br />

ABSTRACT:<br />

In 1960, the United Nations Organization adopted the<br />

Declaration on the Granting of Independence <strong>to</strong> Colonial<br />

Countries and Peoples, in which was established the right <strong>to</strong><br />

self-determination and independence of non-self-governing<br />

terri<strong>to</strong>ries. In order <strong>to</strong> implement these principles was created<br />

in 1961 the Special Committee on the Implementation of the<br />

Declaration on the Granting of Independence <strong>to</strong> Colonial<br />

Countries and Peoples, widely known as Decolonization<br />

Committee. Since the beginning of its activities, the<br />

Decolonization Committee elected the Portuguese colonialism<br />

as one of its main concerns. As the Portuguese government,<br />

until 1974, did not recognize its legitimacy, the Committee<br />

turned its attention <strong>to</strong> the national liberation movements. The<br />

relationship between the Decolonization Committee and the<br />

national liberation movements of Portuguese colonies was<br />

<strong>to</strong>uched by several important moments. The Committee<br />

became a stage in which the national liberation movements<br />

developed a diplomatic struggle against the Portuguese<br />

colonial domination.<br />

THE ROLE OF THE DECOLONIZATION COMMITTEE OF THE UNITED NATIONS ORGANIZATION IN<br />

THE STRUGGLE AGAINST PORTUGUESE COLONIALISM IN AFRICA: 1961-1974<br />

AURORA ALMADA E SANTOS

Alison J. Ayers is an<br />

Assistant Professor,<br />

Departments of Political<br />

Science, Sociology and<br />

Anthropology,<br />

Simon Fraser <strong>University</strong>, BC,<br />

Canada;<br />

email: ajayers@sfu.ca<br />

Please do not cite without<br />

written permission from the<br />

author.<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

It is commonplace <strong>to</strong> characterise political violence and war in Africa as<br />

‘internal’, encapsulated in the apparently neutral term ‘civil war’. As such,<br />

accounts of political violence tend <strong>to</strong> focus narrowly on the combatants<br />

or insurrectionary forces, failing <strong>to</strong> recognize or address the extent <strong>to</strong><br />

which political violence is his<strong>to</strong>rically and globally constituted. The paper<br />

addresses this problematic core assumption through examination of the<br />

case of Sudan, seeking <strong>to</strong> contribute <strong>to</strong> a rethinking of protracted political<br />

violence and social crisis in postcolonial Africa. The paper interjects in<br />

such debates through the use and detailed exposition of a distinct<br />

methodological and analytical approach. It interrogates three related<br />

dimensions of explanation which are ignored by orthodox framings of<br />

‘civil war’:<br />

1. the technologies of colonial rule which (re)produced and<br />

politicised multiple fractures in social relations, bequeathing a<br />

fissiparous legacy of racial, religious and ethnic ‘identities’ that<br />

have been mobilised in the context of postcolonial struggles over<br />

power and resources;<br />

2. the major role of geopolitics in fuelling and exacerbating conflicts<br />

within Sudan and the region, particularly through the cold war<br />

and the ‘war on terror’; and<br />

3. Sudan’s terms of incorporation within the capitalist global<br />

economy, which have given rise <strong>to</strong> a specific character and<br />

dynamics of accumulation, based on primitive accumulation and<br />

dependent primary commodity production.<br />

The paper concludes that political violence and crisis are neither new nor<br />

extraordinary nor internal, but rather, crucial and constitutive dimensions<br />

of Sudan’s neo-colonial condition. As such, <strong>to</strong> claim that political violence<br />

in Sudan is ‘civil’ or ‘internal’ is <strong>to</strong> countenance the triumph of ideology<br />

over his<strong>to</strong>ry.<br />

BEYOND THE IDEOLOGY OF ‘CIVIL WAR’:<br />

THE GLOBAL-HISTORICAL CONSTITUTION OF POLITICAL VIOLENCE IN SUDAN<br />

ALISON J. AYERS

Charles Belanger is a<br />

Graduate Student, Political<br />

Economy of Development,<br />

<strong>University</strong> of Toron<strong>to</strong>, Canada<br />

Charles.belanger@u<strong>to</strong>ron<strong>to</strong>.ca<br />

Charles.belanger@finca.org<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

Although microfinance in developing countries is mostly used as<br />

a <strong>to</strong>ol <strong>to</strong> lift poor women out of poverty, it is also increasingly<br />

being used as a medium <strong>to</strong> involve women in<strong>to</strong> democratization<br />

process at the local level. The strength of Microfinance<br />

Institutions (MFI) as a mobilization medium is that they are able<br />

<strong>to</strong> reach large number of poor women because of a widely<br />

spread need for financial services. In this study, the author<br />

assesses the relevance of microfinance as a medium <strong>to</strong> foster<br />

democratization through the case study of CADD (Cercle<br />

d’Au<strong>to</strong>promotion pour le Développement Durable), a MFI with<br />

which the author had first hand experience. Based in Benin,<br />

CADD regroups 3500 women that are directly involved in<strong>to</strong> the<br />

democratization process. While CADD’s mobilization of women<br />

is unique in that it regroups an unprecedented number of<br />

women in political struggle, this study finds that women’s<br />

involvement in<strong>to</strong> the democratization is not fruitful because of<br />

the very financial and business oriented nature of the MFI.<br />

Acknowledgements:<br />

The author wishes <strong>to</strong> thank Judith Teichman (<strong>University</strong> of Toron<strong>to</strong>),<br />

who’s comments helped <strong>to</strong> improve the work.<br />

WOMEN AND DEMOCRATIZATION IN WEST AFRICA:<br />

THE CASE OF CADD, A COMMUNITY-BASED GROUP FOCUSING ON CONSUMPTION ISSUES.<br />

CHARLES BELANGER

Since 1994, the eastern regions of the<br />

Democratic Republic of the Congo have been<br />

beset by prolonged instability and violence.<br />

Triggered by the events in neighbouring<br />

Rwanda – specifically, the war that was<br />

launched in 1990 in the north which ended with<br />

the genocide in 1994 – eastern Congo’s<br />

provinces of North Kivu and South Kivu have<br />

suffered greatly at the hands of armed forces,<br />

be they regional armies, rebel surrogates, or<br />

ethnic militias. <strong>From</strong> 1996 onwards, the<br />

bilateral relationship between the Rwandese<br />

and Congolese governments has played a<br />

critical role in shaping the situation in eastern<br />

Congo. After facilitating the installation of a<br />

friendly regime in Congo, Rwanda and Congo<br />

soon broke ties, creating a bitter and bloody<br />

enmity between the two countries that would<br />

endure for the next 10 years, marked by<br />

military confrontations, the pillaging of the<br />

Congo’s natural resources, and the deaths of<br />

over 6 million people. In an unexpected twist in<br />

regional dynamics, in January 2009, Rwanda<br />

and Congo suddenly normalized their relations,<br />

becoming ostensible allies and jointly<br />

participating in military operations on<br />

Congolese soil, only weeks after being indirectly<br />

at war through the use of proxy rebels. This<br />

development was particularly puzzling,<br />

considering that in international relations<br />

friendly countries can often abruptly become<br />

enemies and go <strong>to</strong> war. The inverse – unfriendly<br />

countries suddenly becoming allies – typically<br />

takes several years. This paper analyzes the<br />

events that very quickly turned these enemies<br />

in<strong>to</strong> partners and the implications for the Great<br />

Lakes region of Africa, as well as an overview of<br />

Rwanda-Congo bilateral relations since 1996.<br />

Following the cataclysm of the Rwandese<br />

genocide, an estimated 2 million Rwandese<br />

Hutu fled westward in<strong>to</strong> neighbouring Congo<br />

(then named Zaire) as the Tutsi Rwandan<br />

Patriotic Force (RPF) rebels swept in<strong>to</strong> the<br />

capital, Kigali. Among the fleeing refugees were<br />

perpetra<strong>to</strong>rs of the genocide, including much of<br />

the Rwandese army and its militias, which were<br />

given safe haven and support by Zaire’s head of<br />

state, Mobutu Sese Seko, souring relations<br />

between the new RPF government in Rwanda<br />

and the old regime in Zaire. In 1996, Rwanda<br />

launched its first of many subsequent invasions<br />

of eastern Zaire/Congo, under the guise of a<br />

local rebellion, using the pretext that the<br />

presence of the Hutu forces directly across the<br />

border was an existential threat <strong>to</strong> Kigali’s post-

Paper presented at Kwame<br />

Nkrumah International<br />

Conference:<br />

<strong>Kwantlen</strong> <strong>Polytechnic</strong> <strong>University</strong>,<br />

Richmond, British Columbia,<br />

August 19-21, 2010.<br />

© Amir Hossein Mirfakhraie,<br />

2010<br />

Sociology Department, <strong>Kwantlen</strong><br />

<strong>Polytechnic</strong> <strong>University</strong>, 12666-<br />

72nd Avenue, Surrey, British<br />

Columbia V3W 2M8, Canada.<br />

Email:<br />

amir.mirfakhraie@kwantlen.ca<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

In this paper, I analyze and deconstruct the 2004 and earlier editions<br />

of Iranian school textbooks for how official knowledge about the ideal<br />

Iranian citizen, Africa, Asia and the Americas is constructed and<br />

presented <strong>to</strong> students. I examine “how [the images and<br />

representations of the ideal Iranian citizen, Africans, Asians and the<br />

inhabitants of the Americas are] composed of different textual<br />

elements and fragments” that, in their discursive formation, present a<br />

coherent and universal view and language about the world <strong>to</strong><br />

students (See Thompson, 1996, p. 570). I focus on four main recurring<br />

educational themes of identity politics, diversity, “citizenship” and<br />

development in analyzing how national identity and the ideal citizen<br />

find racialized local and global representations. I provide data on how<br />

school knowledge differentiates between human beings, groups and<br />

nations through the invocation of racialized, nation-centric and<br />

xenophobic discourses. I utilize the <strong>to</strong>ols and insights of antiracism,<br />

transnationalism and poststructuralism <strong>to</strong> highlight the various forms<br />

of absent and present discourses and categories of otherness that are<br />

employed in simultaneously constructing an image of the ideal citizen<br />

and national identity that ends up dominating and erasing these<br />

various forms of global otherness. In deconstructing the meanings of<br />

texts, I draw upon deconstruction, discourse analysis and qualitative<br />

content analysis.<br />

Keywords:<br />

Iranian School Textbooks; Racialization; Otherness; Colonialism; Discourse;<br />

Religious Diversity; the Ideal Iranian Citizen; Orientalism; Racism