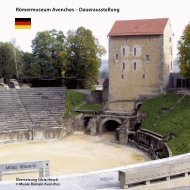

Avenches – Roman Museum – Permanent Exhibition

Avenches – Roman Museum – Permanent Exhibition

Avenches – Roman Museum – Permanent Exhibition

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

First Floor Language and Writing<br />

No inscriptions in Gaulish have been discovered in Aventicum. From time to time,<br />

Celtic names are found, written in a mixture of Greek and Latin alphabets (display<br />

case 6, no.9, display case 23, no. 1). It can be assumed that, from the 1st century<br />

AD onwards, the inhabitants of Aventicum understood Latin. This is confirmed by<br />

funerary, honorific and votive inscriptions dating from this period as well as graffiti<br />

carved on various types of surfaces.<br />

They used a stylus (stilus) for writing (display case 6, nos. 19-21) which had one<br />

sharp end for incising the letters into a wax-covered wooden tablet. The other end<br />

was spatula-shaped so that the text could be erased by smoothing out the wax.<br />

Several tablets could be tied together with a string (display case 6, no. 18).<br />

For writing on papyrus or parchment they used a calamus or quill with a<br />

sharpened point, which was dipped into an inkwell (atramentarium). The latter<br />

could be made of glass (display case 6, no. 10), pottery (display case 6, no. 11) or<br />

bronze. The ink was diluted with water before its use and was either derived from<br />

cuttlefish, from lees of wine or consisted of a mixture of soot and resin.<br />

A book (volumen) consisted of several pages of papyrus or parchment glued<br />

together, which were then rolled onto a wooden stick (display case 6, no. 1).<br />

Capital letters were used for inscriptions on stone and for hallmarks on mortars<br />

(display case 6, no. 8), vases (display case 6, no. 9), amphorae, tiles, and also on various<br />

metal objects.<br />

Engraved (display case 6, nos. 2-3) or painted inscriptions (display case 6, nos. 4-<br />

5) were generally written in italics (small letters); the same applied to everyday<br />

correspondence. Occasionally graffiti were written in capital letters (display case 6,<br />

nos. 6-7).<br />

Seal-boxes (display case 6, nos. 12-16) served as protection for seals used for<br />

closing up writing tablets or parcels. In order to seal something, the intaglioengraved<br />

signet ring was pressed into wax (display case 6, no. 17).<br />

Display case 6<br />

1. Marble statue of a sitting philosopher or poet holding a volumen in his left hand.<br />

2. Fragment of a grey ceramic storage vessel bearing the inscription, in italics, ...icco<br />

immallobrocus, the meaning of which is not clear.<br />

3. Majuscule inscription on painted wall plaster.<br />

4. Neck of amphora (1st century AD) with painted inscription indicating its contents (1):<br />

Excel(lens) / flos... « Excellent flower » ... (referring to the quality of garum, a sauce<br />

containing pieces of fish pickled in salt).<br />

5. Amphora neck bearing a painted inscription indicating its capacity (LXX probably<br />

70 <strong>Roman</strong> pounds or the equivalent of approximately 32.8 litres) as well as the merchant’s<br />

name in genitive case: Felicionis (Felicio). 2nd century AD.<br />

6. Jug fragments (2) with a graffito in capital letters:<br />

LAGO(NA) NICOMIIDIIS QVI ILLA IIMIIRIT<br />

« The (wine)jug of Nicomedes who really deserves it »<br />

1<br />

2<br />

24<br />

First Floor<br />

6