Avenches – Roman Museum – Permanent Exhibition

Avenches – Roman Museum – Permanent Exhibition

Avenches – Roman Museum – Permanent Exhibition

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Avenches</strong> <strong>–</strong> <strong>Roman</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>–</strong> <strong>Permanent</strong> <strong>Exhibition</strong><br />

Translation Sandy Hämmerle<br />

© Musée Romain <strong>Avenches</strong>

<strong>Avenches</strong> <strong>–</strong> <strong>Roman</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>–</strong> <strong>Permanent</strong> <strong>Exhibition</strong><br />

Table of contents<br />

Ground Floor <strong>–</strong> Introduction 3<br />

Aventicum, Capital of the Helvetii . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3<br />

The <strong>Roman</strong> Empire . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4<br />

Switzerland in <strong>Roman</strong> Times . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4<br />

Chronology of Events . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5<br />

Ground Floor 7<br />

The Gallo-<strong>Roman</strong> Population of Switzerland and Their View of Death . . . . . . . 7<br />

Funerary Urns 9<br />

Child Burials 10<br />

Cremation Burials 10<br />

Inhumation Burial 11<br />

Christian Burial 11<br />

The Extraordinary Finds from the Necropolis of En Chaplix 12<br />

The Funerary Monuments of En Chaplix 13<br />

The Northern Monument 14<br />

The Southern Monument 15<br />

The Inscriptions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16<br />

Stone Inscriptions of <strong>Avenches</strong> / Aventicum 17<br />

Miscellaneous . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19<br />

First Floor 21<br />

The Early Days of Aventicum . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21<br />

The Indigenous Population . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22<br />

Language and Writing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23<br />

The Division of Time . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25<br />

Weights and Measures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26<br />

The Dodecahedron, a Measuring Instrument? 27<br />

Theatre, Games and Music . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28<br />

Trade and Money . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30<br />

The Monetary System from the 1 st <strong>–</strong> 3 rd Century 30<br />

Prices and Remuneration 31<br />

Genuine Coins and Counterfeits 31<br />

Money Saving and Spending Reflected in Coin Finds 32<br />

Rome and Aventicum . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33<br />

The Imperor, the Imperial Family and the Province 33<br />

Table of Contents<br />

1

Religion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37<br />

Oriental Cults 37<br />

<strong>Roman</strong> Religion 38<br />

Mythology and Heroes 41<br />

The Local Gods 41<br />

Housegods and Their Cult: Lararia and Domestic Chapels 43<br />

The Sanctuaries of Aventicum 43<br />

From Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44<br />

Second Floor 45<br />

A Typical <strong>Roman</strong> Town House . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45<br />

Clothes and Jewellery . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46<br />

Body and Health Care . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47<br />

Games . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49<br />

Games of Chance 49<br />

Strategic Games 49<br />

Games of Skill 49<br />

Textile Production . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50<br />

Lighting . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51<br />

Furniture . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51<br />

Gardens . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52<br />

Life in Town . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53<br />

Town Layout 53<br />

Houses 53<br />

Protective Gods of the Household . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54<br />

Pottery. An Indispensable Tool for Archaeologists as Regards ... . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55<br />

... Quantities 55<br />

... a Means for Dating other Finds 55<br />

... its Various Uses 55<br />

An Important Contribution to the Understanding of Local History 55<br />

Kitchen and Tableware . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56<br />

Food . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57<br />

A Big Market 57<br />

Drinking and Eating 57<br />

The Table of the Poorer People 58<br />

The Table of the Wealthy 59<br />

The Kitchen 59<br />

Eating Habits 59<br />

Types of Tableware 60<br />

Table of Contents<br />

2

Ground Floor <strong>–</strong> Introduction Aventicum, Capital of the Helvetii<br />

<strong>Avenches</strong> <strong>–</strong> <strong>Roman</strong> <strong>Museum</strong><br />

Ground Floor <strong>–</strong> Introduction<br />

Aventicum, Capital of the Helvetii<br />

The founding of Aventicum can probably be linked to the unsuccessful migration of<br />

the Helvetii in 58 BC and the subsequent return to their homeland. The name of the<br />

town is derived from Aventia, a Celtic protective goddess. Aventicum was the capital<br />

of the Helvetii.<br />

No precise indications are available as to when the town was founded. Over the<br />

past number of years, Late Celtic (1st century BC) tombs (1) and ditches southeast<br />

of what would later become <strong>Avenches</strong> have been discovered on several occasions.<br />

During the second half of the 1st century BC, an oppidum was located further south,<br />

on the Bois de Châtel.<br />

There is evidence of a harbour in <strong>Avenches</strong> dating from around AD 5/6 at<br />

the latest (plan, no. 4). The orthogonal grid of streets, which was characteristic of<br />

<strong>Roman</strong> towns, had also been set up. Until the 2nd century AD, more than 60 insulae<br />

(rectangular living areas) were created. The town had a forum (public square),<br />

several thermae (public baths) and at least eight temples. The cemeteries were<br />

located along the roads leading into and out of the town.<br />

Stone from the Jura Mountains was the main building material used. Large parts<br />

of the town were built on rather humid ground. For this reason it was necessary to<br />

stabilise the foundations by driving oak piles into the ground (2). This wood is often<br />

still preserved and can be dated precisely using dendrochronology (method for<br />

dating based on measuring tree rings).<br />

Aventicum experienced a first “golden age” around AD 30 <strong>–</strong> 50 during the reigns<br />

of the emperors Tiberius and Claudius. A group of larger than life-sized sculptures of<br />

the members of the imperial family decorating the forum of the town bear witness<br />

to this.<br />

In AD 71/72 emperor Vespasian whose father and sons spent part of their lives<br />

in Aventicum elevated the town to the rank of a colony named Colonia Pia Flavia<br />

Constans Emerita Helvetiorum Foederata. At that time a town wall measuring 5.5 km<br />

in length was erected around the 563-acre territory. Shortly afterwards the theatre,<br />

the amphitheatre and the Cigognier sanctuary were built; these three buildings are<br />

typical examples of <strong>Roman</strong> public architecture.<br />

Far away from the borders of the Empire and spared of regional political<br />

crises, Aventicum prospered over a long period of time until the beginning of<br />

the 3rd century AD. Although the invasions of the Alamanni seem to have caused<br />

Aventicum around 180 AD<br />

B. Gubler, Zurich<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

Ground Floor<br />

Introduction

Ground Floor <strong>–</strong> Introduction Switzerland in <strong>Roman</strong> Times<br />

considerable damage, building activities were still ongoing in the 4 th century AD, in<br />

particular fortification work around the theatre.<br />

A large part of the population of Aventicum probably belonged to the tribe of<br />

the Helvetii. The members of the local elite undoubtedly preserved their status;<br />

they were the first to obtain <strong>Roman</strong> citizenship. These notables guaranteed both<br />

the survival of <strong>Roman</strong> culture and the maintenance of a certain degree of political<br />

stability.<br />

Until the 6th century AD <strong>Avenches</strong> was a bishop’s see. In the 7th century AD the<br />

town received the new name Wibili, which, later on, became Wiflisburg.<br />

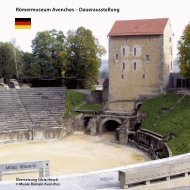

Interest in the archaeological remains of the <strong>Roman</strong> city of <strong>Avenches</strong> began to<br />

arise in the 16th century. A few excavations were carried out from the 18th century<br />

onwards (1), but systematic investigations only started with the foundation of the<br />

Pro Aventico Association in 1885. The <strong>Roman</strong> museum was created in 1824. Since<br />

1838, it has been installed in this medieval tower, which was built at the end of the<br />

11th century on the remains of the <strong>Roman</strong> amphitheatre and using stones from that<br />

monument.<br />

The <strong>Roman</strong> Empire<br />

Over a period of eight centuries, Rome created an empire from a small nucleus<br />

founded in 753 BC. Around 300 BC, the conquest of Italy was achieved and by<br />

around 50 BC large parts of Europe, the Near East and North Africa had been<br />

annexed. In AD 117 the Empire had reached its zenith. Large sections of the Empire<br />

were protected against incursions from neighbouring peoples by a network of<br />

border fortifications (limes).<br />

The <strong>Roman</strong> domination over the conquered territory was based on five pillars: a<br />

strong army, an homogenous legislation, a common administration, one common<br />

currency and one or <strong>–</strong> more precisely <strong>–</strong> two official languages, namely Latin in the<br />

west and Greek in the east.<br />

During the 3rd century AD the deterioration of the climatic conditions as well as<br />

a number of economic and political upheavals marked the beginning of the decline,<br />

which led to the fall of the Western Empire in AD 476.<br />

However, <strong>Roman</strong> civilisation in Europe stayed very much alive for a further<br />

thousand years. Until the 16th century Latin remained the common language of<br />

educated people. <strong>Roman</strong> Law was the basis of quite a number of present-day legal<br />

systems and, with a few slight adjustments, the <strong>Roman</strong> calendar is still in use today.<br />

Switzerland in <strong>Roman</strong> Times<br />

The territory of present-day Switzerland became part of the <strong>Roman</strong> Empire in 15 BC<br />

at the latest and was integrated into five different provinces: The Grisons and a<br />

large section of eastern Switzerland were part of Raetia, the Ticino and the southern<br />

valleys of the Grisons belonged to Italia, the Valais to the Alpae Graiae et Poeninae,<br />

1<br />

Map of <strong>Avenches</strong> (J. C. Hagenbuch, 1727)<br />

4<br />

Ground Floor<br />

Introduction

Ground Floor <strong>–</strong> Introduction<br />

the so-called Alpine Provinces, and Geneva was part of Gallia Narbonensis. The<br />

midlands between the Jura Mountains and the Alps (the territory of the Helvetii) as<br />

well as the region around Basle (the territory of the Rauraci) were initially attached<br />

to Belgica and then to Germania Superior.<br />

An important network of roads criss-crossed what is now Switzerland: a major<br />

route led from south to north via the St. Bernard pass and the passes in the Grisons<br />

while another arterial road connected western and eastern parts. In addition,<br />

there were navigable waterways from the Lakes of Neuchâtel and Morat via the<br />

Rhine towards the North Sea and from the Lake of Geneva via the Rhone to the<br />

Mediterranean. These different transport axes were used for moving troops,<br />

transporting civilians as well as for short and long distance trade exchanges.<br />

During the 1st century AD, a legion, i.e. 6’000 soldiers and auxiliary troops, was<br />

stationed at Vindonissa (Windisch, Canton Argovia).<br />

Urban settlements were a new development. Examples of such urban<br />

settlements were Nyon (Colonia Iulia Equestris), Augst (Augusta Raurica) (1),<br />

Martigny (Octodurus / Forum Claudii Vallensium) and <strong>Avenches</strong> (Aventicum). Smaller<br />

towns were dependent on these cities and a variety of farms and rural settlements,<br />

in turn, depended on these smaller towns.<br />

Masonry was another innovation introduced by the <strong>Roman</strong>s. While initially, this<br />

technique was reserved for public buildings, it gradually became more popular for<br />

private buildings both in urban and rural settings.<br />

The regional economy was mainly based on agriculture, but various specialised<br />

skills and crafts developed simultaneously, sometimes even reaching an industrial<br />

scale. The incorporation into a vast trading network resulted in many products that<br />

had been unknown until then being imported such as foodstuffs like olive oil, fish<br />

sauces, dates and oysters.<br />

Chronology of Events<br />

753 BC Founding of the City of Rome (2)<br />

509 BC Founding of the <strong>Roman</strong> Republic<br />

3 rd <strong>–</strong> 1 st centuries BC Expansion of the <strong>Roman</strong> Empire (Italian Peninsula,<br />

Iberian Peninsula, Greece, parts of Asia Minor and North<br />

Africa).<br />

58 BC Unsuccessful exodus of the Helvetii and battle against<br />

Julius Caesar at Bibracte<br />

58 <strong>–</strong> 51 BC <strong>Roman</strong> conquest of Gaul<br />

27 BC Beginning of the Imperial period<br />

27 BC <strong>–</strong> AD 14 Reign of Augustus (3)<br />

25 BC Opening of the Great St. Bernard route<br />

16 / 15 BC Subjugation of the Alpine regions<br />

1<br />

Augusta Raurica (Augst)<br />

M. Schaub, Römermuseum Augst<br />

2<br />

3<br />

Chronology of Events<br />

5<br />

Ground Floor<br />

Introduction

Ground Floor <strong>–</strong> Introduction Chronology of Events<br />

AD 5 / 6 Oldest constructions found to date at Aventicum<br />

AD 14 <strong>–</strong> 101 Legionary camp at Vindonissa (Windisch, Canton<br />

Argovia)<br />

AD 43 Conquest of Britannia (Great Britain) under the reign of<br />

emperor Claudius<br />

AD 71 / 72 Aventicum obtains the status of a colony under the reign<br />

of emperor Vespasian and is called Colonia Pia Flavia<br />

Constans Emerita Helvetiorum Foederata<br />

AD 117 Largest expansion of the Empire under the reign of<br />

emperor Trajan<br />

2 nd century AD Height of power of Rome and its provinces<br />

AD 275 Incursions by the Alamanni into Helvetian territory;<br />

major destructions<br />

4 th century AD Earliest Christian evidence at Aventicum (1)<br />

AD 395 Split of the <strong>Roman</strong> Empire into western and eastern<br />

sections<br />

AD 476 Fall of the Western <strong>Roman</strong> Empire<br />

6 th century AD Aventicum becomes an Episcopal see<br />

AD 592 Marius (Saint-Maire), the last bishop of Aventicum, moves<br />

to Lausanne<br />

7 th century AD <strong>Avenches</strong> is also called Wibili, later becoming<br />

germanised into Wiflisburg<br />

11 th century AD onwards Development of the medieval town still visible today (2)<br />

2<br />

1<br />

6<br />

Ground Floor<br />

Introduction

Ground Floor The Gallo-<strong>Roman</strong> Population of Switzerland and Their View of Death<br />

Ground Floor<br />

The Gallo-<strong>Roman</strong> Population of Switzerland and Their View of Death<br />

The Helvetii believed in some form of life after death.<br />

Before they died, some drew up a will settling their succession and giving<br />

instructions concerning their funeral, the choice of their grave and its upkeep, the<br />

funerary banquets, etc. The executor made sure that the will of the deceased was<br />

adhered to.<br />

The funerals were paid for either by the deceased or by their families. Less well<br />

off people joined a collegium funeraticium and regularly contributed to a funerary<br />

fund to cover their burial costs (purchase of ground, construction and upkeep of the<br />

tomb, periodical meals and offerings). Important people within a community were<br />

sometimes granted the honour of a public funeral.<br />

As stipulated by <strong>Roman</strong> law, the necropolises were situated along the main<br />

roads leading into and out of the towns. The deceased were taken to the cemetery<br />

on a bier carried by members of their immediate family and friends. Inhumation<br />

and cremation coexisted. However, the latter was predominant during the first<br />

two centuries AD. Infants whose teeth had not yet erupted were never cremated<br />

regardless of the period they lived in (display case 2). From the 3rd century AD<br />

onwards, inhumation became the rule, undoubtedly due to the influence of oriental<br />

cults and the rise of Christianity (display case 5).<br />

Cremations were carried out in the open air (1) where the dead were placed<br />

on a pyre along with their personal belongings (clothes, jewellery) and vessels<br />

containing food (display case 3). During the cremation, small flasks with aromatic<br />

plants and perfumes were thrown into the fire. Afterwards the bones were gathered<br />

and placed in urns, which were put into a grave together with some of the burnt<br />

objects (2). In most cases the urns were ceramic or glass vessels (display case 1),<br />

originally intended for domestic use, and sometimes wooden caskets were used<br />

(display case 3); such containers were rarely produced specifically for funerary<br />

purposes.<br />

In the case of inhumation (3) the deceased was placed in a wooden coffin<br />

(display case 4); sarcophagi made of stone or lead <strong>–</strong>were rare in this region <strong>–</strong>and<br />

only later became popular. The deceased was usually laid on his or her back, less<br />

frequently on the stomach or on the side. Offerings were often deposited in the<br />

coffin or the grave, but our perception remains incomplete since usually only<br />

objects made of non-perishable materials such as ceramics, glass or metal survived;<br />

traces of food are rarely found and basketry or objects made of leather, wood or<br />

cloth do not often survive.<br />

Once the tomb was closed, its location was marked, in order to remind the living<br />

to respect its inviolability and to honour the memory of the deceased (nos. 1 <strong>–</strong> 8).<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

7<br />

Ground Floor

Ground Floor The Gallo-<strong>Roman</strong> Population of Switzerland and Their View of Death<br />

The markers for burial places varied considerably: stone or wooden tombstones,<br />

simple stones, small mounds as well as “aedicules” or mausoleums. In most cases<br />

tombstones were engraved with an epitaph and sometimes further decorations<br />

were added. The beginning of the inscription Dis Manibus, often abbreviated to DM,<br />

dedicated a grave to the Manes of the departed or to the spirits of the dead; then<br />

followed the name of the deceased, sometimes his or her filiation, age, profession<br />

or training, honorific titles and, finally, the name of the person who erected the<br />

monument. The deceased was usually represented alone or perhaps accompanied<br />

by his wife or his son; sometimes he was depicted at work. In the <strong>Roman</strong> Empire the<br />

funerary portraits assumed the function of preserving the memory of the deceased.<br />

Some tombstones were decorated with symbols referring to the immortality of<br />

the soul: laurel leaves, birds, celestial bodies. Wealthy people often paid tribute to<br />

their memory by erecting monuments with the statues of the deceased. This can be<br />

seen in the cemetery of En Chaplix. Such monuments were surrounded by gardens,<br />

embellished with statues and sometimes water basins and protected by walls.<br />

The tomb and its surroundings were looked upon as being sacrosanct and holy<br />

and they remained the property of the deceased. The cult of the deceased included<br />

funerary celebrations held at regular intervals on the occasion of the parentalia<br />

(from 13th to 21st February), at which food and drink were given to the dead and<br />

libations (act of pouring out a liquid as a sacrifice) were offered.<br />

Several necropolises are known at Aventicum. The most impressive and richest<br />

of them seems to have been that at the west gate where the remains of several<br />

small funerary chapels, a considerable number of tombstones and the burial place<br />

of a young Christian girl were found. The port necropolis, situated near the lake<br />

and containing approximately forty modest burials, may have been reserved for<br />

the workers in the port. The En Chaplix necropolis, situated beside the road outside<br />

the town at the northeast gate, contained approximately two hundred burials,<br />

which, according to the offerings, must have belonged to people of a higher socioeconomic<br />

standing.<br />

1. Tombstone of Visellia Firma (1)<br />

Erected by her parents. The little girl died aged one year and 50 days.<br />

Limestone. En Chaplix necropolis.<br />

2nd century AD. Catalogue of inscriptions no. 13.<br />

2. Pinecones as tomb decorations<br />

Placed on top of a little mound covering a tomb. Pinecones symbolised immortality.<br />

Limestone. West gate necropolis.<br />

3. Tombstone of Iulia Censorina<br />

Erected by her father.<br />

Limestone. Second quarter of the 1st century AD. Catalogue of inscriptions no. 15.<br />

4. Tombstone of Marcus Alpinius Virilis (2)<br />

Limestone. West gate necropolis.<br />

1st <strong>–</strong> 3rd centuries AD. Catalogue of inscriptions no. 14.<br />

1<br />

2<br />

8<br />

Ground Floor

Ground Floor The Gallo-<strong>Roman</strong> Population of Switzerland and Their View of Death<br />

Funerary Urns<br />

5. Tombstone of Decimus Iulius Iunianus (1)<br />

Erected by his wife.<br />

Limestone. West gate necropolis.<br />

1st <strong>–</strong> 3rd centuries AD. Catalogue of inscriptions no. 11.<br />

6. Tombstone of Flavia Severilla<br />

Erected by her husband. She passed away at the age of 36 (?).<br />

Limestone. West gate necropolis.<br />

Probably 3rd AD. Catalogue of inscriptions no. 12.<br />

7. Tombstone fragment<br />

Bust of a couple with only the head of the man preserved. The names of the deceased<br />

were inscribed on the base, which, however, was lost.<br />

According to the hairstyle and stylistic features of the head, the tombstone dates from<br />

the beginning of the 2nd century AD.<br />

Limestone. West gate necropolis.<br />

8. Funerary monument of a family<br />

Limestone block with sculptures. Originally the funerary monument of a family consisted<br />

of three blocks placed on top of each other in a pilaster-framed niche. Only the badly<br />

preserved top block still remains. The sculpture depicted a couple facing each other. This<br />

type of representation is not rare and, a child was often placed between the man and the<br />

woman. In this instance, only the top of the child’s head is still visible. The mother has put<br />

her right hand on her son’s head while the father, in a similar gesture, is holding a scroll in<br />

his left hand. The pose of the couple is reminiscent of the gesture of uniting right hands<br />

(dextrarum iunctio) symbolising marriage. In a funerary context, this gesture symbolises<br />

the couple being united in life and death.<br />

Second half of the 2nd century AD.<br />

Funerary Urns (2)<br />

(Display case and drawer 1)<br />

1. Urn with ceramic cover<br />

Ceramic cooking pot covered with a mortarium and turned into an urn.<br />

En Chaplix necropolis. AD 100/150 <strong>–</strong> 200.<br />

2. Cover of a marble urn (?)<br />

This probably came from a child burial. In fact, figurines of the child-like God Eros on<br />

tombs for children symbolised their becoming god-like. Sleeping Amor or Somnus (the<br />

god of sleep) on a lion skin are images of Hellenistic origin. Sleep, usually interrupted by<br />

waking up, was set in close context with death and resurrection.<br />

Late 1st century AD.<br />

3. Lead urn<br />

Hammered lead vessels are rather rare finds; most of them were made of several pieces.<br />

West gate necropolis.<br />

4. Glass urn<br />

This bellied pot originally served as a storage vessel.<br />

En Chaplix necropolis. AD 150 <strong>–</strong> 200/250.<br />

5. Glass urn with lid<br />

En Chaplix necropolis. AD 70 <strong>–</strong> 100/120?<br />

1<br />

2<br />

9<br />

Ground Floor<br />

1

Ground Floor The Gallo-<strong>Roman</strong> Population of Switzerland and Their View of Death<br />

Cremation Burials<br />

Child Burials (1)<br />

(Display case and drawer 2)<br />

Inhumation burial of an infant aged four to six months<br />

Port necropolis. Late 1st <strong>–</strong> 2nd centuries AD.<br />

1. Ceramic feeding bottle as grave offering. The infant was buried in a wooden coffin.<br />

Inhumation burial of a few month old infant<br />

En Chaplix necropolis. AD 120 <strong>–</strong> 140.<br />

2. The tableware, consisting of a glass jug and bottle and a small ceramic bowl was<br />

deposited on the coffin.<br />

Inhumation burial of a child aged one to two years<br />

En Chaplix necropolis. Approximately AD 150.<br />

3. The grave goods placed in the lead sarcophagus consisted of two bowls (only one of<br />

which is exhibited) and a glass bead.<br />

Cremation Burials<br />

(Display case and drawer 3)<br />

Cremation burial of a child aged three to four years (2)<br />

En Chaplix necropolis. Approximately AD 125 <strong>–</strong> 130.<br />

The urn, together with a ceramic pot (not burnt), was deposited in a grave as an<br />

offering. Three coins and a silver pendant were found among the burnt and washed<br />

human bone in the urn. Apart from charcoal the grave also contained the remains<br />

of many other offerings, which were burnt on the pyre but only some of which are<br />

exhibited.<br />

1. Glass bottle with two handles, used as urn.<br />

2. Silver pendant and three bronze sestertii (two of Hadrian and one of Domitian),<br />

deposited in the urn with the ashes.<br />

3. Locally produced ceramic pot, not burnt, deposited in the glass urn in the grave.<br />

4. Ceramic tableware, imported from southern Gaul, partly or totally burnt, a bowl, a dish,<br />

a plate and three cups).<br />

5. Locally produced pottery, partially or totally burnt, comprising two jugs, two bowls and<br />

a pot.<br />

6. Several burnt glass vessels including a ribbed cup and a green vessel decorated with<br />

small yellow and brown-red rosettes.<br />

7. Two iron hinges and nails.<br />

8. Penannular fibula, a handle and various other bronze items, all burnt.<br />

9. Two burnt bronze dupondii of Hadrian.<br />

Cremation burial of an adult male, perhaps a shipwright<br />

Port necropolis. Early 2nd century AD.<br />

A wooden box measuring about 35 by 35 cm (not preserved) was used as an urn.<br />

Apart from the burnt bones it contained fragments of iron objects, some of which<br />

may have belonged to the box, as well as three tools, which had not been burnt<br />

1<br />

2<br />

10<br />

Ground Floor<br />

2<br />

3

Ground Floor The Gallo-<strong>Roman</strong> Population of Switzerland and Their View of Death<br />

Christian Burial<br />

with the deceased (1). The proximity to the port and the presence of two tools used<br />

for woodworking gave the archaeologists reason to speculate that the deceased<br />

may have been a shipwright buried in his ”tool box“. Numerous offerings burnt on<br />

the pyre such as animal bones (mainly from pigs) were placed on top of the box.<br />

10. Wooden box as container for the ashes. Only three iron hinges, four iron fittings with<br />

nails, an iron clip and an iron hook have been preserved.<br />

11. Bronze handle of the box (?).<br />

12. Iron saw, folded so that it would fit into the box.<br />

13. Iron adze.<br />

14. Iron pliers with the spring reinforced by a bronze strip.<br />

15. Iron key.<br />

16. Numerous ceramic vessels, totally or partially burnt. Imported tableware (dish,<br />

plates, cups, bowls), locally produced pottery (pots, goblets, jug, bowl), kitchen crockery<br />

(mortarium).<br />

17. Fragment of handle from glass bottle.<br />

18. Glass paste bead.<br />

19. Bronze coin, probably dating from the second half of the 1st century AD.<br />

20. Iron nails.<br />

Inhumation Burial (2)<br />

(Display case and drawer 4)<br />

Tomb of a man<br />

En Chaplix necropolis. AD 150 <strong>–</strong> 180.<br />

The deceased was buried in a nailed wooden coffin (180 by 60 cm). He wore shoes<br />

with nailed soles. Two jugs, a small bowl and a goblet, all produced locally, as well<br />

as an imported plate and two cups were placed beside his right leg. This tableware<br />

was used for eating and drinking.<br />

1-2. Ceramic jugs.<br />

3. Ceramic goblet.<br />

4. Ceramic bowl.<br />

5-6. Ceramic cups.<br />

7. Ceramic plate.<br />

8-9. Iron nails from two soles.<br />

10. Iron coffin nails.<br />

Christian Burial<br />

(Display case and drawer 5)<br />

Inhumation burial of a young girl<br />

West gate necropolis. Mid 4th century AD.<br />

1<br />

2<br />

11<br />

Ground Floor<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5

Ground Floor The Gallo-<strong>Roman</strong> Population of Switzerland and Their View of Death<br />

The Extraordinary Finds at the Necropolis of En Chaplix<br />

The deceased was buried in an oak trunk. The rich grave goods given to her (1)<br />

consisted of a bronze jug, a glass bottle and two glass goblets, a pot or goblet made<br />

of soapstone, a ceramic cup, a partly silver-plated bronze spoon, a necklace made of<br />

glass and jet beads, a jet bracelet as well as four bone sticks (not exhibited).<br />

The glass goblets bear engravings, which are among the earliest evidence of the<br />

Christian faith found in western Switzerland. On the bigger vessel, the Latin inscription<br />

Vivas in Deo<br />

«May you live in God»<br />

clearly refers to the hope of resurrection. The smaller goblet shows an inscription in<br />

Greek, partly preserved, abbreviated and transcribed with Latin letters,<br />

Pie zezes<br />

«Drink that you may live»<br />

which affirms that eternal life is obtained by holy communion.<br />

1. Bronze jug.<br />

2. Glass bottle.<br />

3. Glass goblet with the inscription Vivas in Deo (“May you live in God”)<br />

4. Glass goblet with the inscription pie zezes (“Drink that you may live”)<br />

5. Bronze spoon.<br />

6. Pot or goblet made of soapstone.<br />

7. Ceramic cup.<br />

8. Glass and jet bead necklace.<br />

9. Jet bracelet<br />

The Extraordinary Finds at the Necropolis of En Chaplix<br />

During the construction of the motorway important archaeological remains were<br />

discovered in En Chaplix (2), situated at a distance of approximately 150 m from the<br />

north-east gate of Aventicum.<br />

The first sanctuary was erected around 15/10 BC, during the reign of the<br />

emperor Augustus (27 BC <strong>–</strong> AD 14). In the middle of an open square, bordered by<br />

a ditch, a wooden aedicule (small wooden temple) sheltered the cremation burial<br />

of a woman and probably her child. The discovery of two fibulae originating from<br />

regions either along the Danube or in the eastern Alps indicate that the deceased<br />

may have come from that area. The numerous coin offerings prove that this tomb<br />

had become a place of veneration.<br />

During the reign of Tiberius (AD 14 <strong>–</strong> 37) the En Chaplix site grew in a rapid<br />

and spectacular way (3). The construction of a road leaving Aventicum in the<br />

northeast was followed by the reconstruction and extension of the first sanctuary.<br />

The aedicule was replaced by a small Gallo-<strong>Roman</strong> temple (fanum) and a chapel.<br />

A similar complex was erected directly beside it. The timber walls were probably<br />

inserted into masonry foundations. These sanctuaries were frequently visited in the<br />

1st century in particular and remained intact well into the 4th century AD.<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

12<br />

Ground Floor<br />

5

Ground Floor The Gallo-<strong>Roman</strong> Population of Switzerland and Their View of Death<br />

The Extraordinary Finds at the Necropolis of En Chaplix<br />

Between AD 23 and 28, a first funerary monument was erected on the other side<br />

of the road.<br />

Around AD 40, a second monument (1) was built on an adjacent fenced-in piece<br />

of land.<br />

From the second half of the 1st century AD onwards, a necropolis was set up and<br />

enclosed by ditches in the immediate surroundings of the funerary monuments.<br />

The graves date mainly from the 2nd century AD, but some were still being added at<br />

the beginning of the 3rd century.<br />

In the second half of the 2nd century AD, two capstones from the wall<br />

surrounding the funerary monuments were used to mark the tombs of the<br />

necropolis, a sign that the site began to fall into disuse and that the veneration of<br />

the deceased may have been abandoned.<br />

Towards the end of the 3rd century (?), the two monuments were dismantled in<br />

order to recover the stones.<br />

The Two Funerary Monuments of En Chaplix<br />

Between AD 23 and 40, two funerary monuments (mausoleums), 23 and 25 m high,<br />

were erected along the main road leaving Aventicum through the northeast gate.<br />

Their architecture and decoration was inspired by Greco-<strong>Roman</strong> examples.<br />

From these Jura limestone constructions, enclosed by brick walls, only the<br />

foundations and a few hundred scattered elements are preserved. Towards the<br />

end of the <strong>Roman</strong> Empire the monuments had probably already been dismantled<br />

by people salvaging construction material. Architectural pieces and sculptures<br />

considered unsuitable for reuse were left behind.<br />

The mausoleums were of similar height and consisted of three tiers. The base<br />

was a massive semicircular podium bearing an inscription, which is lost today. The<br />

inscription contained the names of the deceased and the highpoints of their military,<br />

political and professional careers. The identity of these noblemen will probably<br />

remain a mystery forever. The main tier consisted of an aedicule with columns, which<br />

sheltered three statues of the deceased and their families. The person in the middle<br />

was always slightly taller than the other two. The top tier consisted of a pyramidshaped<br />

spire decorated with scales carved into the stone. The image would have<br />

been imposing to passers-by at the time. The harmonious lines cleverly drew the<br />

attention of the onlookers towards the aedicule and the statues.<br />

The decoration of the two monuments demonstrated strong Hellenistic<br />

influence. Although no traces of colour have been found, it cannot be ruled out that<br />

certain parts were painted, as this was the case with other similar monuments.<br />

The enclosures guaranteed peace for the deceased and were perhaps arranged<br />

as gardens and decorated with statues. They afforded families a place to carry out<br />

commemorative ceremonies and funerary banquets. No grave for either of these<br />

1<br />

B. Gubler Zurich<br />

13<br />

Ground Floor

Ground Floor The Gallo-<strong>Roman</strong> Population of Switzerland and Their View of Death<br />

The Extraordinary Finds at the Necropolis of En Chaplix<br />

deceased has been discovered, but it is possible that the urns containing their ashes<br />

stood on top of the monuments or that these were cenotaphs (empty tombs) and<br />

that the remains were buried elsewhere.<br />

The connection between these two monuments built at an interval of twelve<br />

years is not known. However, it seems plausible that the deceased were related and<br />

perhaps owned the suburban villa situated on the nearby site called Le Russalet.<br />

The villa and the monuments may have belonged to a large native Helvetian family,<br />

thus confirming the rapid integration of the local aristocracy into the new <strong>Roman</strong><br />

order. These two monuments reflected the prosperity of <strong>Avenches</strong> during the<br />

Tiberian period.<br />

The Northern Monument<br />

During the construction of the first monument the unstable ground forced the<br />

builders to set the foundations on a number of oak piles driven deep into the<br />

ground. Thanks to the humidity of the ground the wood was preserved and it was<br />

possible through dendrochronological analyses to establish that the felling dates of<br />

the trees lay between AD 23 and 28.<br />

The sculptures (1) decorating the upper part of the podium on both sides of<br />

the exedra represented two symmetrical groups each consisting of a Triton seizing<br />

a Nereid. The concave part was most probably decorated with friezes as proven by<br />

three rather badly preserved male portraits, one of which was probably part of a<br />

retinue.<br />

Judging by the shape of the roof, the ground plan of the aedicule must have<br />

been octagonal. Only a few fragments of the three statues are preserved. The<br />

central figure was a woman <strong>–</strong> probably the owner and donator of the monument <strong>–</strong><br />

flanked by two men wearing togas.<br />

The crown of the roof was decorated with a group consisting of a Satyr carrying<br />

the Child Bacchus, thus symbolising the elevation of the deceased to higher spheres.<br />

9. Satyr Carrying the Child Bacchus (2)<br />

Satyrs, recognisable by their long horses’ ears and their scruffy hairstyles, belong to the<br />

retinue of the wine god Bacchus. In this instance, Bacchus is depicted as a child and has<br />

wings. This particular feature indicates that he is assimilated with Amor-Somnus who<br />

personifies sleep.<br />

In funerary symbolism groups comprising Satyrs and Bacchus represent the<br />

exhilarating and carefree life in the hereafter. Placing such a group on the roof of the<br />

monument implies that the deceased had achieved a divine existence and was enjoying<br />

life after death. This is very important because it is one of the earliest examples of this<br />

Hellenistic theme having been taken over by the <strong>Roman</strong>s (3rd <strong>–</strong> 2nd centuries BC).<br />

Group, in limestone, crowning the northern monument of En Chaplix. Around 30 AD.<br />

10. Head of a Drunken Silenus (3)<br />

Like the Satyrs, the Sileni belong to the retinue accompanying Bacchus. Their particular<br />

features are horses’ ears, bald heads and bulbous noses. Comparisons with other known<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

14<br />

Ground Floor

Ground Floor The Gallo-<strong>Roman</strong> Population of Switzerland and Their View of Death<br />

The Extraordinary Finds at the Necropolis of En Chaplix<br />

statues indicate that this Silenus was depicted in a resting pose with legs crossed and<br />

his head turned to the right. He wears a crown of ivy leaves and flowers. Like in the case<br />

of the Satyr carrying the Child Bacchus, the movement of the Silenus’ head and the<br />

rapturous expression in his face point to an Hellenistic model (3rd <strong>–</strong> 2nd centuries BC). The<br />

Silenus statue, which stood in the funerary garden of a necropolis, symbolises carefree<br />

life after death.<br />

Fragment of limestone statue, belonging to the northern En Chaplix monument. Around<br />

AD 30.<br />

11. Nereid Bust<br />

The Nereids are sea deities, daughters of Nereus, the Old Man of the Sea. Of this group<br />

only the bust of the Nereid from the upper block and a fragment of Triton’s fish tail<br />

belonging to the lower part are preserved. Regarding the model and the symbolic<br />

meaning, please refer to the group on the right (no. 12), which is better preserved.<br />

Limestone. Group situated in the upper left-hand corner of the façade of the northern En<br />

Chaplix monument. Around AD 30.<br />

12. Triton Seizing a Nereid (1)<br />

Tritons are sea deities. Their upper bodies have human form while they are fish-shaped<br />

from the stomach down. They belong to the retinue of Neptune, the God of the Sea. In<br />

this case, a Triton is using both his hands to pin down a terrified Nereid on his fish tail. Her<br />

coat is billowing in the wind.<br />

Models for the Triton and Nereid group can be found in the Hellenistic period<br />

(3rd <strong>–</strong> 2nd centuries BC). The motif is often used for funerary decorations, in particular on<br />

sarcophagi. The sea creature theme symbolises blissful and carefree life after death.<br />

Made of limestone, this group was placed in the upper right-hand corner of the façade of<br />

the northern En Chaplix monument. Around AD 30.<br />

The Southern Monument<br />

The second monument was modelled on the same pattern as the first. Built on more<br />

stable ground it did not require the use of piles, so this monument cannot be dated<br />

as precisely as the first one.<br />

The very similar decoration is better preserved. In the upper part of the base,<br />

the Nereids are carried by griffins instead of Tritons. On the pedestal, two so-called<br />

”dancing“ Attis statues, followed by a clipeus (circular decorative motif), may have<br />

once framed the lost inscription.<br />

A man wearing a toga, flanked by a second man and a woman was depicted in<br />

the middle of the square column-framed aedicule. The pointed, square shaped roof<br />

ended in a pinecone symbolising immortality.<br />

13. Male Portrait (2)<br />

The preserved fragments allow for the restitution of the statue as depicting one of<br />

the deceased, represented as a <strong>Roman</strong> citizen wearing a toga and holding a scroll<br />

(volumen); at his feet lies a box (scrinium) containing other scrolls. Holes in his forehead<br />

indicate that he wore a metal crown, which, however, was lost. The hairstyle with curls is<br />

inspired by representations of emperor Tiberius (AD 14 <strong>–</strong> 37). The realistic features of his<br />

face correspond to the concept of expressive art prevailing at the end of the Republic<br />

(1st century BC). This very carefully executed effigy is one of only a small number of<br />

1<br />

2<br />

15<br />

Ground Floor

Ground Floor The Inscriptions<br />

portraits of a private person found to date in Switzerland.<br />

Limestone. Funerary statue situated left of the middle statue in the aedicule of the<br />

southern En Chaplix monument. Around AD 40.<br />

14. Head of Attis<br />

Attis, the Phrygian god of vegetation and lover of Cybele, a goddess from Asia Minor, is<br />

represented here in a pensive and sad mood. His usual attributes are the Phrygian cap<br />

and Barbarian dress. In a funerary context he symbolises mourning caused by death<br />

and the anticipation of resurrection. This statue and its counterpart, of which only a few<br />

fragments were found, stood in the funerary garden.<br />

Limestone. Statue belonging to the southern En Chaplix monument. Around AD 40.<br />

15. Dancing Attis and Edge of a Clipeus (1)<br />

The limestone block shows a relief depicting Attis as a dancer with his left arm in the air<br />

and his right arm posed on his hip. He is wearing a Phrygian cap and Barbarian dress<br />

consisting of a long-sleeved tunic held together by a double belt and trousers plus a coat.<br />

The inside of the clipeus (round decorative motif) on the adjacent block (not preserved)<br />

was decorated either with a floral motif or with a mask.<br />

The presence of such a motif and the image of the dancing Attis, which appeared<br />

from the 3rd century BC onwards, clearly show the influence from southern Gaul.<br />

The clipeus motifs are widespread along the River Rhone. While, on the other hand,<br />

representations of a dancing Attis are frequently found in Provence, they are not known<br />

in the provinces along the Rivers Rhine and Danube.<br />

In the Cybele cult Attis dies every winter to be reborn in spring and in the funerary<br />

context he is a symbol for death followed by resurrection.<br />

The reliefs with Attis and the clipeus were situated in the corners near the base,<br />

probably framing the lost inscription.<br />

Limestone. Relief from the lower corner of the podium of the southern En Chaplix<br />

monument. Around AD 40.<br />

16. Nereid Riding on a Sea Griffin (2)<br />

A Nereid with her coat blowing in the wind is sitting on a bearded sea griffin and holding<br />

a shell in her hand. Nereids often ride on sea griffins with eagle or lion heads. The latter<br />

belong to the thiasus (retinue) of sea deities. Like in the case of the group of Triton and<br />

Nereids, models for <strong>Roman</strong> representations can be found in the Hellenistic period (3rd <strong>–</strong><br />

2nd centuries BC). These groups symbolise blissful life after death.<br />

Limestone. Group placed in the upper right-hand corner of the façade of the southern En<br />

Chaplix monument. Around AD 40.<br />

The Inscriptions<br />

Among other sources, written messages have always been the most important<br />

evidence on which to base our interpretation of the past.<br />

Today, several hundred thousand inscriptions from all provinces of the <strong>Roman</strong><br />

Empire are known; they are preserved on various types of materials. The texts were<br />

carved in stone or put together as mosaics, engraved on metal objects, stamped<br />

or scratched onto pottery or tiles, written in ink on papyrus sheets or simply<br />

1<br />

2<br />

16<br />

Ground Floor

Ground Floor The Inscriptions<br />

The Stone Inscriptions of <strong>Avenches</strong> / Aventicum<br />

painted onto walls. Inscriptions offer various kinds of information; they may serve<br />

as self-portraits or propaganda, but they also reflect the wealth or reputation of<br />

corporations and individuals.<br />

In the western part of the <strong>Roman</strong> Empire representative stone inscriptions were<br />

mainly written in Latin and more rarely in Greek. They offer an excellent insight<br />

into the different areas of social life in antiquity. According to their contents <strong>Roman</strong><br />

inscriptions can be grouped into building, honorific, funerary and dedicatory<br />

inscriptions. The contents of a text may also refer to the original location of the<br />

inscription. Dedicatory inscriptions were linked with the various districts of worship,<br />

honorific inscriptions were located on the forum and could belong to statues in<br />

public areas, building inscriptions adorned public buildings such as baths, theatres<br />

or bridges and funerary inscriptions were found in the official cemeteries outside<br />

the living quarters.<br />

The 21 letters of the Latin alphabet, some of which were also used to express<br />

numbers, were generally written in capitals. Decorative elements such as framing,<br />

the use of colour or the addition of pictures were used to enhance the impact of the<br />

text. The messages were often encoded and abbreviations were common. Although<br />

a good knowledge of the many <strong>Roman</strong> abbreviations is useful for decoding certain<br />

parts of the texts, there are still phrases, which cannot be deciphered precisely.<br />

Considering that in those days many people were illiterate <strong>–</strong> hence the visual<br />

presentation of a text being more important than its contents <strong>–</strong> it can be assumed<br />

that the majority enjoyed looking at a lavishly presented public inscription without<br />

understanding exactly the message it conveyed.<br />

Carving inscriptions in stone was rather expensive. Apart from the costs incurred<br />

by the choice of material and the size of the epigraph, the salaries of various<br />

specialists usually had to be added as well. First a scribe (auctor) composed the<br />

text, then, taking into account the dimensions of the stone, a designer (ordinator)<br />

prepared the layout, which afterwards was transferred by a painter (pictor) onto the<br />

future monument so that the stonemason (lapidarius) could do the sculpting. While<br />

it is impossible today to identify exactly the various cost components, one can<br />

assume that the donator or donators must have belonged to the wealthier section<br />

of the population.<br />

The Stone Inscriptions of <strong>Avenches</strong> / Aventicum<br />

Approximately 150 stone inscriptions are known to date from the <strong>Roman</strong> town of<br />

Aventicum. Some of them have such monumental dimensions that they cannot be<br />

exhibited within the museum space presently available.<br />

Honorific inscriptions for individual citizens referring to their professional careers<br />

and their services to the Helvetian community or the <strong>Roman</strong> colony are frequent.<br />

It becomes apparent that, at least at certain times, family clans played a dominant<br />

1<br />

17<br />

Ground Floor

Ground Floor The Inscriptions<br />

The Stone Inscriptions of <strong>Avenches</strong> / Aventicum<br />

role in administrative and political positions. The influence and personal interests<br />

of some families, therefore, determined the destiny of the town to a considerable<br />

extent.<br />

The numerous dedications show that, while the population took on the <strong>Roman</strong><br />

pantheon, they also maintained the Gallo-Celtic belief system. It is interesting that a<br />

relatively large number of people held an office as priests within the imperial cult.<br />

At least three roads leading into the town of Aventicum can be identified as socalled<br />

funerary roads lined with tombstones.<br />

Besides the fact that the design of the preserved tombstones was very varied,<br />

it is also striking that the inscriptions were relatively brief and some of them were<br />

engraved in a rather careless way. Some texts refer to the considerable financial<br />

commitment of individual people regarding the maintenance or extension of public<br />

buildings. It also stands out that the so-called scholae are mentioned rather often.<br />

They may have been honorary halls or gathering places. It seems that outstanding<br />

citizens of Aventicum were publicly honoured not only by erecting statues on<br />

pedestals with inscriptions but also by granting them permission to erect a schola.<br />

17. Architrave with dedication (1)<br />

Donated by the navigators on the Aar and the Aramus in honour of the imperial family<br />

Limestone. Discovered east of insula 33 at the edge of the forum.<br />

Late 2nd century AD. Catalogue of inscriptions no. 9.<br />

18. Base of a statue with dedication in honour of Quintus Cluvius Macer<br />

Limestone. Discovered in the eastern section of insula 28, the eastern portico of the<br />

forum.<br />

Second quarter or mid 2nd century AD. Catalogue of inscriptions no. 7.<br />

19. Capital of pilaster with dedication to the Lugoves (2)<br />

Limestone. Lugoves are Celtic gods who can be equated with Mars and Mercury.<br />

The capital served as a pedestal for several statues<br />

Discovered between the enclosures of the Grange des Dîmes and the Cigognier temples.<br />

Late 2nd or early 3rd century AD. Catalogue of inscriptions no. 2.<br />

20. Architrave with inscription commemorating the construction of a hall for ball games<br />

Limestone. Discovered between insula 19 and the enclosure of the Grange des Dîmes<br />

temple.<br />

First half of the 2nd century AD. Catalogue of inscriptions no. 10.<br />

21. Altar with dedication to the goddess Aventia and to the genius of the townspeople<br />

(incolae) of <strong>Avenches</strong> (3)<br />

Limestone. Original location unknown.<br />

2nd <strong>–</strong> 3rd centuries AD. Catalogue of inscriptions no. 18<br />

22. Marble dedication to the goddess Aventia<br />

Original location unknown.<br />

2nd <strong>–</strong> 3rd centuries AD. Catalogue of inscriptions no. 17.<br />

23. Altar with dedication offered to doctors and teachers<br />

Limestone. Original location unknown.<br />

Second half of the 2nd or early 3rd century AD. Catalogue of inscriptions no. 4.<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

18<br />

Ground Floor

Ground Floor Miscellaneous<br />

24. Marble inscription in honour of [---] dius Flavus<br />

Discovered in insula 40, at the edge of the forum.<br />

Last quarter of the 1st century AD. Catalogue of inscriptions no. 1.<br />

25. Dedication in honour of Septimius Severus<br />

Discovered in insula 40, at the edge of the forum.<br />

AD 193-211. Catalogue of inscriptions no. 8.<br />

27. Inscription on mosaic adorning a semi-public building (1)<br />

Discovered in insula 29, next to the forum.<br />

Early 3rd century AD. Catalogue of inscriptions no. 19. Catalogue of mosaics no. 2.<br />

Miscellaneous<br />

28. Mosaic depicting Hercules and Antaeus (2)<br />

The tessellated floor consists of a series of pictures with the central laurel-framed image<br />

representing the fight between Hercules and Antaeus. Hunting and animal fight scenes<br />

are depicted in the centre, at each side of the main medallion.<br />

Antaeus was an African king, who drew his enormous strength from the earth and had<br />

to touch soil in order to be able to defeat his enemies. When Hercules was threatened by<br />

Antaeus, they began to wrestle; Hercules grabbed his opponent by the shoulders and lifted<br />

him up so that he could not renew his strength, and then he squashed and destroyed him.<br />

Here, Hercules is wearing a wreath and is thus depicted as a triumphant athlete.<br />

The corner squares show people that look like wrestlers because of their broad<br />

shoulders, muscular chests and thick necks. They are wearing wreathes made of leaves<br />

similar to that of Hercules. They are quite obviously victorious wrestlers.<br />

All the figurative motifs combined convey an image of triumph of bodily strength.<br />

Original dimensions: 5 m by 4.5 m. Private house situated in insula 59.<br />

Second quarter of the 3rd century AD. Catalogue of mosaics no. 20.<br />

29. Mosaic depicting gladiators<br />

This almost square piece of tessellated floor decorated the centre of a room, perhaps<br />

a dining room with three beds arranged in a U-shape (triclinium) along the walls.<br />

The geometric design is conceived in such a way that ones attention is drawn to the<br />

centrepiece. The badly damaged central scene depicts two fighting gladiators. While only<br />

their legs are preserved, they are easily recognised as gladiators because of the coloured<br />

bands tied around their knees indicating which troupe they were part of.<br />

Original dimensions: 2 m by 2.5 m. Northern suburb, private house situated north of<br />

insula 5.<br />

Second half of the 2nd century AD. Catalogue of mosaics no. 5.<br />

30. Limestone relief with head of the god Sol<br />

The <strong>Roman</strong> representations of this god are inspired by the Hellenistic iconography of Helios.<br />

This relief may have belonged to a large bust placed in the centre of the gable of a building.<br />

Probably from insula 19. Late 1st century AD.<br />

1<br />

2<br />

19<br />

Ground Floor

Ground Floor Miscellaneous<br />

31. Limestone statue of a lion (1)<br />

The lion’s paw is resting on the head of an animal, maybe a bull or a horse. This is a<br />

decoration of a fountain; the front base is hollow so that a water pipe could be inserted.<br />

Discovered in the region of Derrière la Tour, originating probably from the western part<br />

of insula 16.<br />

First half of the 2nd century AD.<br />

32. The so-called «Red Drawing Room» mural<br />

This mural decorated the living room or dining room of a private house, located in the<br />

northeastern part of the town. While the painting is relatively modest for a reception<br />

room, the work was carried out by experienced artisans.<br />

The dark red background colour, which is rarely found north of the Alps, takes up<br />

a large area of the wall. The dividing decorative elements, placed at regular intervals,<br />

consist of ornamental stands entwined by tendrils and ribbons, candelabra with crossed<br />

thyrsi and pilaster-strips. These vertical motifs are surrounded by small pictures or<br />

medallions containing female busts, a comedy mask and a bird. The lower part was<br />

redesigned approximately 15 to 25 years later and is divided into yellow panes with tufts<br />

of plants and narrower panels in flecked wine red marble imitation.<br />

This mural is a good example of the Pompeian Third Style as it developed in Gaul with<br />

certain characteristics of the Fourth Style already appearing. The Pompeian paintings<br />

were classified into four styles in the late 19th century. The classification is still used<br />

today as a basis for the chronology and typology of paintings throughout the <strong>Roman</strong><br />

Empire. The Pompeian Third Style appeared around 20 <strong>–</strong> 15 BC, during the reign of the<br />

emperor Augustus. It is characterised by the rejection of the illusionist architecture of<br />

the preceding Second Style and by large colour panels decorated with various motifs,<br />

often miniatures. The Fourth Style, which began under Claudius (AD 41 <strong>–</strong> 54), preferably<br />

consisted of symmetrically placed motifs and architectural dividing elements.<br />

Insula 18. Around AD 45.<br />

1<br />

20<br />

Ground Floor

First Floor The Early Days of Aventicum<br />

First Floor<br />

The Early Days of Aventicum<br />

(Display cases 1-2)<br />

The name Aventicum derives from a local Celtic water deity, Aventia, tutelary of the<br />

<strong>Roman</strong> city (display case 2, no. 1).<br />

Because of its central position on the Swiss Plateau, the region of Aventicum has<br />

been inhabited for a very long time; its easy access to the river and lake network<br />

favoured the expansion of commerce and trade.<br />

On several occasions, settlement traces dating from periods prior to the <strong>Roman</strong><br />

conquest have been found both inside and outside the city walls (Late Bronze<br />

Age, Hallstatt and La Tène periods). In 58 BC, the Helvetii who had entrenched<br />

themselves in the oppidum of the Mount Vully (1) left their homes and migrated<br />

towards southeastern Gaul. After their defeat by Julius Caesar’s army at Bibracte<br />

(present-day Mount Beuvray in Burgundy), they were forced to return. It is likely that<br />

some of them settled on the heights of the Bois de Châtel hill south of <strong>Avenches</strong>.<br />

The hill of <strong>Avenches</strong> may also have served as a refuge.<br />

Only a small number of remains date from the period immediately preceding<br />

the establishment of the first urban complex, namely from the 1st century BC. They<br />

were discovered in religious contexts such as sanctuaries or tombs (display case 1,<br />

no. 1) situated on the slopes of the <strong>Avenches</strong> hill. These early finds are indigenous<br />

Celtic objects such as fibulae (display case 1, nos. 6-7), painted ware (display case 1,<br />

no. 5) or fine grey ware (display case 1, no. 4) as well as coins (display case 1, nos. 9-12).<br />

Some of them also provide evidence of trade relations with Italy (display case 1,<br />

no. 2) and Gaul (display case 1, no. 3).<br />

The Celtic coin punch (display case 1, no. 8) is of particular interest. A mere 30<br />

such objects are known in the Celtic world including that discovered on Mount<br />

Vully. It is a bronze punch, which was used to strike the obverse of a Celtic denarius.<br />

A cremation burial, which was discovered in the area of the settlement,<br />

dates from the beginnings of Aventicum, i.e. from the late 1st century BC or early<br />

1st century AD (display case 1, no. 14). The urn, a small ceramic bowl, contained the<br />

ashes of a woman and two bronze fibulae were deposited on top. The coin no. 13<br />

(display case 1) dates from the same period.<br />

Thanks to wood preserved in the ground (2) it is possible in several cases to<br />

establish the exact felling dates of the trees used for the construction of the first known<br />

buildings of Aventicum. In this instance, the assistance provided by dendrochronology<br />

(dating of the tree rings of a piece of timber) is particularly efficient. Accordingly, the<br />

construction of the port began in AD 5; the trees used to build the earliest houses<br />

discovered to date were felled in autumn/winter AD 6/7. These houses were already<br />

part of the orthogonal road network typical of <strong>Roman</strong> towns.<br />

1<br />

2<br />

21<br />

First Floor<br />

1<br />

2

First Floor The Indigenous Population<br />

Display case 1<br />

Items 1 - 5 were found in the area of the Derrière La Tour sanctuary.<br />

1. Ceramic urn containing cremated human bone. Early 1 st century BC.<br />

2. Terra sigillata plate from Central Italy. The centre shows the potter’s stamp of L. Tetti<br />

Crito. Late 1 st century BC. (1)<br />

3. Ceramic plate from the region of Lyons. Late 1 st century BC.<br />

4. Ceramic pot with vertical comb decoration. 1 st century BC.<br />

5. Ceramic pot or bottle, decorated with painted bands. 1 st century BC.<br />

6. Bronze fibula. Late 1 st century BC / early 1 st century AD.<br />

7. Bronze fibula. 1 st century AD.<br />

8. Celtic coin punch (2).<br />

9. Celtic coin: Quinarius of Vatico. Second half of the 1 st century BC.<br />

10. Celtic coin: Quinarius of Caletedu. Second half of the 1 st century BC.<br />

11. Celtic coin: Büschel type Quinarius. Second half of the 1 st century BC.<br />

12. Celtic coin: Sequanian potin. 1 st century BC.<br />

13. <strong>Roman</strong> coin: Quadrans of Germanus Indutilli. After 15 BC.<br />

14. Burnt ceramic bowl, signed Atei. It contained two bronze fibulae placed on tiny<br />

fragments of cremated human bone. Late 1 st century BC / early 1 st century AD.<br />

Display case 2<br />

1. Dedication to the goddess Aventia (3) :<br />

Deae /<br />

Aventiae Cn(aeus)Iul(ius)<br />

Marcellinus<br />

Equester<br />

d(e) s(ua) p(ecunia)<br />

« To the goddess Aventia. (Monument erected and) paid for by Gnaeus Iulius Marcellinus<br />

from the equestrian colony »<br />

Limestone. 1 st <strong>–</strong> 3 rd century AD.<br />

Catalogue of inscriptions : no. 16.<br />

The Indigenous Population<br />

(Display cases 3-5)<br />

Most of the inhabitants of the <strong>Roman</strong> city of Aventicum were native Celtic Helvetii<br />

already living in the region prior to the conquest; a smaller portion of the inhabitants,<br />

however, were <strong>Roman</strong>s sent by the emperor in order to advance the city’s<br />

development (merchants, businessmen, civil servants). The indigenous population,<br />

who outnumbered them by far, were <strong>Roman</strong>ised within a few generations. Rome<br />

granted citizenship to a considerable number of Celtic aristocratic families, perhaps<br />

in exchange for certain services or land (display case 4, no. 1).<br />

The population underwent a process of fast <strong>Roman</strong>isation and rapidly adopted<br />

the customs and habits of the conquerors.<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

22<br />

First Floor<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5

First Floor Language and Writing<br />

Nevertheless, Celtic culture and traditions survived. The Celtic heritage is apparent<br />

in art (display case 3, no. 1; display case 5, nos. 1-2), religion, writing, craftsmanship<br />

(display case 5, nos. 3-6), hairstyles and clothing (display case 3, no. 1).<br />

Display case 3<br />

1. Bust of woman (1) wearing a torque, a typical Celtic piece of jewellery, as well as a tunic<br />

and a cloak fashionable among the native population. Limestone. Early 1st century AD at<br />

the latest.<br />

Display case 4<br />

1. Dedication in honour of Caius Valerius Camillus:<br />

C(aio) Valer(io) C(ai) f(ilio) Fab(ia)Ca<br />

millo quoi publice<br />

funus Haeduorum<br />

civitas et Helvet(i)decre<br />

verunt et civitas<br />

Helvet(iorum)<br />

qua pagatim qua publice<br />

statuas decrevit<br />

I[u]lia C(ai)Iuli Camilli f(ilia) Festilla<br />

ex testamento<br />

« To Caius Valerius Camillus, son of Caius, of the Fabia tribe, for whom the communities<br />

of the Haedui and Helvetii ordered an official funeral; furthermore, the community of the<br />

Helvetii dedicated statues to him, in the name of each pagus as well as in the name of<br />

the entire civitas. Iulia Festilla, daughter of Caius Iulius Camillus, (erected this inscription)<br />

according to the last will of the deceased »<br />

Marble block, discovered near the forum. Second quarter of the 1st century AD.<br />

Catalogue of inscriptions: no. 5.<br />

Display case 5<br />

1. Head of woman, limestone. Cigognier sanctuary. Second half of the 2nd century AD.<br />

2. Gilt bronze head of a dead Helvetian (2). Cigognier sanctuary. 2nd century AD.<br />

3. Ceramic pot, painted according to local tradition.<br />

4-5. Ceramic goblets, with figurative decoration. Second half of the 2nd century AD.<br />

6. Ceramic goblet with erotic scene. Second half of the 2nd century AD.<br />

Language and Writing<br />

(Display case 6)<br />

The Helvetii spoke Gaulish, a Celtic language, which probably varied from one region<br />

of Gaul to the next. It was mainly a spoken language. The rare evidence at our<br />

disposal consists of written documents of lesser importance, which offer only limited<br />

information about Celtic culture. In the beginning, the Celts used Greek letters to<br />

transcribe their language. The arrival of the <strong>Roman</strong>s led to the dissemination of Latin,<br />

a new language, which, depending on the density of the <strong>Roman</strong> immigrants, was<br />

more or less understood and adopted.<br />

1<br />

2<br />

23<br />

First Floor<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6

First Floor Language and Writing<br />

No inscriptions in Gaulish have been discovered in Aventicum. From time to time,<br />

Celtic names are found, written in a mixture of Greek and Latin alphabets (display<br />

case 6, no.9, display case 23, no. 1). It can be assumed that, from the 1st century<br />

AD onwards, the inhabitants of Aventicum understood Latin. This is confirmed by<br />

funerary, honorific and votive inscriptions dating from this period as well as graffiti<br />

carved on various types of surfaces.<br />

They used a stylus (stilus) for writing (display case 6, nos. 19-21) which had one<br />

sharp end for incising the letters into a wax-covered wooden tablet. The other end<br />

was spatula-shaped so that the text could be erased by smoothing out the wax.<br />

Several tablets could be tied together with a string (display case 6, no. 18).<br />

For writing on papyrus or parchment they used a calamus or quill with a<br />

sharpened point, which was dipped into an inkwell (atramentarium). The latter<br />

could be made of glass (display case 6, no. 10), pottery (display case 6, no. 11) or<br />

bronze. The ink was diluted with water before its use and was either derived from<br />

cuttlefish, from lees of wine or consisted of a mixture of soot and resin.<br />

A book (volumen) consisted of several pages of papyrus or parchment glued<br />

together, which were then rolled onto a wooden stick (display case 6, no. 1).<br />

Capital letters were used for inscriptions on stone and for hallmarks on mortars<br />

(display case 6, no. 8), vases (display case 6, no. 9), amphorae, tiles, and also on various<br />

metal objects.<br />

Engraved (display case 6, nos. 2-3) or painted inscriptions (display case 6, nos. 4-<br />

5) were generally written in italics (small letters); the same applied to everyday<br />

correspondence. Occasionally graffiti were written in capital letters (display case 6,<br />

nos. 6-7).<br />

Seal-boxes (display case 6, nos. 12-16) served as protection for seals used for<br />

closing up writing tablets or parcels. In order to seal something, the intaglioengraved<br />

signet ring was pressed into wax (display case 6, no. 17).<br />

Display case 6<br />

1. Marble statue of a sitting philosopher or poet holding a volumen in his left hand.<br />

2. Fragment of a grey ceramic storage vessel bearing the inscription, in italics, ...icco<br />

immallobrocus, the meaning of which is not clear.<br />

3. Majuscule inscription on painted wall plaster.<br />

4. Neck of amphora (1st century AD) with painted inscription indicating its contents (1):<br />

Excel(lens) / flos... « Excellent flower » ... (referring to the quality of garum, a sauce<br />

containing pieces of fish pickled in salt).<br />

5. Amphora neck bearing a painted inscription indicating its capacity (LXX probably<br />

70 <strong>Roman</strong> pounds or the equivalent of approximately 32.8 litres) as well as the merchant’s<br />

name in genitive case: Felicionis (Felicio). 2nd century AD.<br />

6. Jug fragments (2) with a graffito in capital letters:<br />

LAGO(NA) NICOMIIDIIS QVI ILLA IIMIIRIT<br />

« The (wine)jug of Nicomedes who really deserves it »<br />

1<br />

2<br />

24<br />

First Floor<br />

6

First Floor The Division of Time<br />

It is worth noting that two vertical bars were used to transcribe the letter E, which had<br />

been a frequently used sign in the former Celtic region. The name Nicomedes points to<br />

Greek origin and he was probably a slave.<br />

7. Goblet bearing an engraved graffito in capital letters: SIIXTVS. According to Celtic<br />

tradition, the letter E is written with two vertical bars in this rather typical Latin name.<br />

2nd century AD.<br />

8. Mortar (mortarium) manufactured in Aventicum and bearing the stamp of the potter<br />

Ruscus. 2nd century AD.<br />

9. Fragment of plate manufactured in Aventicum and bearing the stamp of the potter<br />

Cinced. It is worth noting that the name is written with a barred D as used in the very rare<br />

Celtic inscriptions. Second half of the 1st century AD.<br />

10. Glass inkwell (1).<br />

11. Ceramic inkwell.<br />

12-16. Bronze seal-boxes (2).<br />

17. Bronze ring with intaglio depicting a dolphin.<br />

18. Facsimile wooden tablets, filled with wax.<br />

19-21. Iron styli (writing implements).<br />

The Division of Time<br />

(Display cases 7-8)<br />

With the exception of a few minor changes, the <strong>Roman</strong> calendar introduced by<br />

Julius Caesar in 46 BC, is still in use today and continues to regulate our lives. The<br />

<strong>Roman</strong> year began on January 1st and was divided into twelve months, the names<br />

and sequence of which have remained unchanged. Determining the day of a<br />

month was complicated because, unlike in present times, this was not achieved by<br />