Angelus News | July 12, 2024 | Vol. 9 No. 14

On the cover: A PBS series recently suggested purgatory was the “invention” of 14th-century Italian poet Dante Alighieri. Could it be true? Does such a place — somewhere between heaven and hell — really exist? On Page 10, contributing editor Mike Aquilina details purgatory’s biblical roots in the Old and New Testaments, all of which point to the hope and forgiveness God promises “in the age to come” to believers.

On the cover: A PBS series recently suggested purgatory was the “invention” of 14th-century Italian poet Dante Alighieri. Could it be true? Does such a place — somewhere between heaven and hell — really exist? On Page 10, contributing editor Mike Aquilina details purgatory’s biblical roots in the Old and New Testaments, all of which point to the hope and forgiveness God promises “in the age to come” to believers.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

apply in a recollected moment.<br />

• • •<br />

Purgatory has always been part of<br />

biblical religion. Even before the rise<br />

of Christianity, it was implicit in the<br />

sacred texts and practices of the Jews.<br />

Scholars identify purgatory with<br />

Sheol, the abode of the dead, which is<br />

mentioned more than 60 times in the<br />

Old Testament. Sheol is clearly not<br />

hell. It is populated by Israel’s heroes<br />

as well as its questionable characters.<br />

Job asks to be sent there for “a set<br />

time” until God’s “wrath be past” (Job<br />

<strong>14</strong>:13). It is possible to be sent to Sheol<br />

“in sorrow” (Genesis 44:29). It is also<br />

possible to “go down to Sheol in peace”<br />

(1 Kings 2:6).<br />

In Scripture, Sheol is imagined<br />

vaguely as a place underground, where<br />

disembodied souls persist as “shades”<br />

(Isaiah <strong>14</strong>:9).<br />

The condition of the dead in Sheol<br />

can be improved by the sacrificial<br />

prayers of the living. In the Second<br />

Book of Maccabees, written around<br />

a hundred years before the time of<br />

Christ, the general Judas Maccabeus<br />

learns after battle that some of the<br />

Jewish casualties had been found with<br />

superstitious amulets.<br />

Intending to remedy the sin, he “took<br />

up a collection” from his living soldiers<br />

and “sent it to Jerusalem to provide for<br />

a sin offering.”<br />

The chronicler of the battle then adds<br />

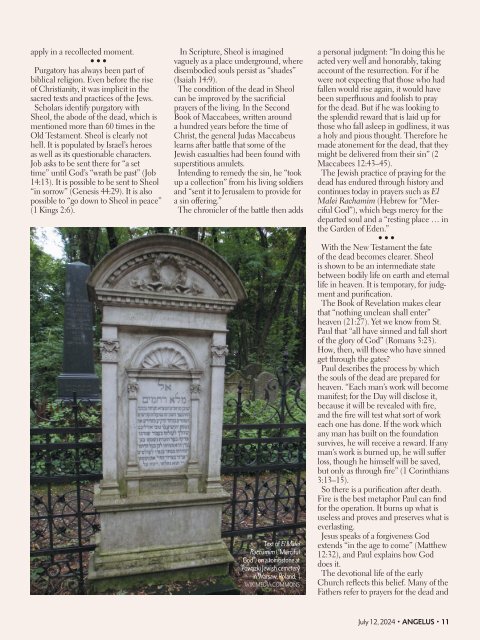

Text of El Malei<br />

Rachamim (“Merciful<br />

God”) on a tombstone at<br />

Powązki Jewish cemetery<br />

in Warsaw, Poland. |<br />

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS<br />

a personal judgment: “In doing this he<br />

acted very well and honorably, taking<br />

account of the resurrection. For if he<br />

were not expecting that those who had<br />

fallen would rise again, it would have<br />

been superfluous and foolish to pray<br />

for the dead. But if he was looking to<br />

the splendid reward that is laid up for<br />

those who fall asleep in godliness, it was<br />

a holy and pious thought. Therefore he<br />

made atonement for the dead, that they<br />

might be delivered from their sin” (2<br />

Maccabees <strong>12</strong>:43–45).<br />

The Jewish practice of praying for the<br />

dead has endured through history and<br />

continues today in prayers such as El<br />

Malei Rachamim (Hebrew for “Merciful<br />

God”), which begs mercy for the<br />

departed soul and a “resting place … in<br />

the Garden of Eden.”<br />

• • •<br />

With the New Testament the fate<br />

of the dead becomes clearer. Sheol<br />

is shown to be an intermediate state<br />

between bodily life on earth and eternal<br />

life in heaven. It is temporary, for judgment<br />

and purification.<br />

The Book of Revelation makes clear<br />

that “nothing unclean shall enter”<br />

heaven (21:27). Yet we know from St.<br />

Paul that “all have sinned and fall short<br />

of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23).<br />

How, then, will those who have sinned<br />

get through the gates?<br />

Paul describes the process by which<br />

the souls of the dead are prepared for<br />

heaven. “Each man’s work will become<br />

manifest; for the Day will disclose it,<br />

because it will be revealed with fire,<br />

and the fire will test what sort of work<br />

each one has done. If the work which<br />

any man has built on the foundation<br />

survives, he will receive a reward. If any<br />

man’s work is burned up, he will suffer<br />

loss, though he himself will be saved,<br />

but only as through fire” (1 Corinthians<br />

3:13–15).<br />

So there is a purification after death.<br />

Fire is the best metaphor Paul can find<br />

for the operation. It burns up what is<br />

useless and proves and preserves what is<br />

everlasting.<br />

Jesus speaks of a forgiveness God<br />

extends “in the age to come” (Matthew<br />

<strong>12</strong>:32), and Paul explains how God<br />

does it.<br />

The devotional life of the early<br />

Church reflects this belief. Many of the<br />

Fathers refer to prayers for the dead and<br />

<strong>July</strong> <strong>12</strong>, <strong>2024</strong> • ANGELUS • 11