Topos 127

heat

heat

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

no <strong>127</strong><br />

2024<br />

to po s.<br />

heat

COVER<br />

IMAGE: Alexander Weiß<br />

The compound responsible for the heat in chillies<br />

is called capsaicin. It binds to receptors in the<br />

mouth and skin, causing the sensation of heat or<br />

burning. To reduce the burning sensation from<br />

eating hot chillies, dairy products like milk,<br />

yogurt, and cheese are effective because casein<br />

in dairy can bind to capsaicin and help wash it<br />

away. In this issue of topos we want to know what<br />

is our cheese to our hot cities? What helps to<br />

reduce the Urban Heat Island Effect? Oh and<br />

BTW: This picture was AI generated. It doesn't<br />

leave you feeling good, does it?<br />

Heat can kill in three major ways: organ failure,<br />

heart attack or kidney failure. Heat is hard work<br />

for the human body. It has to ensure that the<br />

body temperature does not rise too much, otherwise<br />

the structure of the body's own proteins will<br />

be altered, resulting in organ and tissue damage.<br />

Humans produce sweat to counteract the damage<br />

and cool the body. What is more, the blood<br />

vessels also dilate, which in turn lowers the blood<br />

pressure, and the heart increases its pumping capacity<br />

to regulate it. This can lead to a heat<br />

stroke. If left untreated, this will lead to death.<br />

In 2017, researchers at the University of Hawaii<br />

defined that outdoor temperatures of 37 degrees<br />

and above can be dangerous for us. In principle,<br />

however, an increased risk of death can be assumed<br />

from an outdoor temperature of 30 degrees.<br />

The tricky thing is that researchers from<br />

the Insituto de Salud Carlos III in Madrid discovered<br />

in 2017 that people die so quickly during<br />

a heatwave that they do not make it to hospital.<br />

This is why a heat warning of 72 to 48<br />

hours in advance is so important.<br />

In 2021, the number of heat-related deaths<br />

worldwide was 100,000. According to the<br />

WHO, the consequences of climate change are<br />

expected to claim 250,000 victims a year between<br />

2030 and 2050. Malnutrition, malaria, diarrhoea<br />

and – heat – are cited as the cause of<br />

death. Vulnerable groups are particularly at risk<br />

from the heat – including elderly people, pregnant<br />

women and children. According to UNI-<br />

CEF, more than 559 million children were frequently<br />

exposed to heatwaves in 2022. By 2050,<br />

this figure is expected to rise to two billion children.<br />

Two billion, ladies and gentlemen.<br />

The increase in extreme heatwaves is a huge<br />

problem. In May 2024, it made headlines around<br />

the world. In Tabasco, Mexico, several black<br />

howler monkeys dropped dead from the trees<br />

during a heatwave of 45 degrees. Animal welfare<br />

organizations counted 78 dead specimens of the<br />

endangered species at the end of May. In Pakistan,<br />

temperatures of up to 50 degrees were expected<br />

at the same time. Schools closed and<br />

clinics went on alert. It was the third year in a<br />

row that Pakistan experienced an unusual heatwave.<br />

And for several weeks, the officially longest<br />

heatwave in decades swept across Southeast<br />

Asia. In Thailand, at least 61 people died - more<br />

than twice as many as in the whole of 2023. In<br />

Vietnam, hundreds of thousands of dead fish<br />

floated on the surface of the Song May reservoir<br />

and in the Philippines, 53 degrees were measured<br />

in the province of Zamblas. Man-made<br />

climate change is to blame for this, exacerbated<br />

in Southeast Asia by a strong El Niño.<br />

Due to the Heat Urban Island effect, our cities<br />

and metropolitan areas are particularly affected<br />

by the increasing heat – with far-reaching consequences:<br />

the health risks already mentioned,<br />

elevated air pollution levels, increased energy<br />

consumption, water quality issues, compromised<br />

infrastructure, reduced livability but also<br />

climate change amplification.<br />

What I find particularly astonishing is that we<br />

as a society have been aware of the dangers of<br />

increasing heat for decades, but we are still doing<br />

far too little in terms of heat management in<br />

our cities. This is despite the fact that numerous<br />

solutions, innovations and strategies are already<br />

available. For this reason, in this issue of topos<br />

magazine, we discuss the topic of heat in the city<br />

from different angles and present current best<br />

practices – in the hope that we will finally make<br />

significant progress in climate adaptation.<br />

TOPOS E-PAPER: AVAIL-<br />

ABLE FOR YOUR DESKTOP<br />

For more information visit:<br />

www.toposmagazine.com/epaper<br />

THERESA RAMISCH<br />

Editor-in-Chief<br />

t.ramisch@georg-media.de<br />

topos <strong>127</strong> 005

CONTENTS<br />

OPINION<br />

Page 8<br />

THE BIG PICTURE<br />

Page 10<br />

CURATED PRODUCTS<br />

Page 100<br />

REFERENCE<br />

Page 106<br />

METROPOLIS EXPLAINED<br />

Page 12<br />

URBAN PIONEERS<br />

Page 14<br />

EXPOSING THE HIDDEN KILLERS<br />

Page 54<br />

MELTING CITIES<br />

How urban heat kills minorities<br />

and what can be done about it<br />

Page 18<br />

FIGHTING THE HEAT WITH<br />

GREENERY AND CLAY<br />

The value of traditional construction<br />

Page 26<br />

KUALA LUMPUR<br />

How to cool a tropical city<br />

Page 32<br />

UNLIVEABLE IN EAST ASIA<br />

A pessimistic outlook<br />

Page 38<br />

EUROPE'S HEAT-PROOF CITIES<br />

An overview<br />

Page 60<br />

MADRID<br />

Turning an urban heat island into<br />

an urban cooling island<br />

Page 66<br />

FRANKFURT<br />

Heat in the city<br />

Page 72<br />

URBAN HEAT<br />

VISUALIZED<br />

a Picture Series<br />

Page 78<br />

CITY GAMECHANGERS<br />

Page 112<br />

EDGE CITY<br />

Page 114<br />

IMPRINT<br />

Page 113<br />

PROJECTS<br />

Green and blue ideas to counter urban heat<br />

Page 42<br />

THE ART OF FIGHTING HEAT<br />

Artful projects to combat heat<br />

Page 86<br />

MERGING CITY AND NATURE<br />

Mitigating urban heat islands<br />

Page 50<br />

EXPOSING THE HIDDEN KILLERS<br />

How heatmapping could help cool our cities<br />

Page 54<br />

LET’S BEAT THE HEAT!<br />

Join in and become part of the initiative<br />

Page 58<br />

BOSTON<br />

How it tackles the heat<br />

Page 90<br />

THINK VERTICALLY<br />

FOR A CHANGE!<br />

A commentary<br />

Page 96<br />

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

Page 98<br />

PICTURE SERIES: NASA<br />

Page 78<br />

Photos: Toby Elliott on Unsplash, NASA/JPL-Caltech<br />

006 topos <strong>127</strong>

OPINION<br />

MIND THE<br />

HEAT GAP<br />

Will the urban heat island effect in future only be a burden for poor people in?<br />

Studies show that poor people in cities already suffer much more from heat<br />

than wealthier sections of the population. Could the fight against heat islands<br />

therefore increasingly become a kind of devilish marketing tool?<br />

008 topos <strong>127</strong>

Opinion<br />

It seems to be a well-known phenomenon. Poverty<br />

attracts yet more poverty. Or: financially<br />

disadvantaged people struggle more with the effects<br />

of climate change or other climatic challenges<br />

than people who have more money or<br />

live in better neighbourhoods. The same seems<br />

to be true of the urban heat island effect. Poorer<br />

neighbourhoods are affected by this effect more<br />

often and more severely than others. Accordingly,<br />

poorer people are also confronted with<br />

the negative effects of heat islands much more<br />

often and more intensely.<br />

The devil runs in circles<br />

Strictly speaking, it's a vicious cycle. The vast<br />

majority of the world's metropolises prove day<br />

after day that the focus of urban development is<br />

much more on well-known or already better-off<br />

neighbourhoods. As a result, these neighbourhoods<br />

are the first to benefit from the greening<br />

efforts of the administration. As a rule, only<br />

these neighbourhoods become the recipients of<br />

new architecture, which contributes to the general<br />

cooling of the location thanks to green roofs<br />

and façades. Poorer neighbourhoods are generally<br />

not developed. This has a considerable impact<br />

on the sections of the population who, of<br />

course, are unable to obtain any real relief from<br />

the heat due to a lack of money. We are talking of<br />

course about immigrants, older people, the<br />

group of residents formerly known as the working<br />

class and, increasingly, families with children.<br />

Those families who can afford it are moving<br />

to the suburbs or living in high-quality flats<br />

near the city centre. This is certainly not the case<br />

everywhere, but occurs far too often.<br />

As early as 2021, the U.S. Environmental Protection<br />

Agency (EPA) found that people below<br />

the poverty line and immigrants are much more<br />

likely to be affected by the urban heat island effect<br />

than other population groups. Using Baltimore<br />

as an example, joint research by NPR.org<br />

and the University of Maryland's Howard Center<br />

for Investigative Journalism found similar<br />

results. They were able to prove that the hottest<br />

areas of Baltimore are also among the poorest.<br />

This fact is worsened by the fact that heat in metropolises<br />

is a significant health risk. Poorer<br />

population groups are almost defenceless<br />

against this risk. For older people, this can mean<br />

acute danger to life and limb. For children and<br />

young people, this could lead to even greater<br />

difficulties for their start in life than they already<br />

have due to their financial position.<br />

The language of money – climate protection<br />

with $$ in their eyes<br />

Rebuilding our metropolises is expensive.<br />

Health is expensive in many regions of the<br />

world. It seems that climate protection is also<br />

expensive. Of course, there is a lot of truth in all<br />

these statements and especially in the basic idea.<br />

It costs money to transform a large car park into<br />

a green, cooler refuge of tranquillity. It also<br />

costs money to green roofs and build better<br />

public transport infrastructure. Many metropolises<br />

and cities are making these investments in<br />

isolated areas.<br />

However, if you look at our metropolises with<br />

open eyes, you quickly see that heat protection<br />

degenerates into a marketing tool. Cities boast<br />

about heat protection projects that all too often<br />

only benefit the very wealthy city dwellers. An<br />

honest look at the structurally weaker corners<br />

of metropolises shows how much investment is<br />

lacking. One could be forgiven for thinking<br />

that urban development has more to do with<br />

the marketing term ‘return on invest (ROI)’<br />

than with honestly improving the living conditions<br />

of all people.<br />

Thanks to state-of-the-art mapping methods,<br />

however, cities can no longer hide. If we look 15<br />

years into the future, we will increasingly find<br />

metropolises whose wealthier neighbourhoods<br />

are on average up to ten degrees cooler than<br />

traditional working-class or poor neighbourhoods.<br />

It will therefore be impossible to hide<br />

the issue from those wanting to promote heat<br />

protection and climate protection for everyone,<br />

to close the heat gap.<br />

TOBIAS HAGER is a journalist and Chief Content<br />

Officer and member of the management board at<br />

GEORG Media. Responsible for all GEORG brands<br />

such as topos magazine, BAUMEISTER and<br />

Garten + Landschaft, his focus is on the areas of content,<br />

digital, marketing and entrepreneurship.<br />

topos <strong>127</strong> 009

THE BIG PICTURE<br />

Photo: JAM STA ROSA by gettyimages<br />

010 topos <strong>127</strong>

The Big<br />

Picture<br />

Summer Heat Hits Asia<br />

South and Southeast Asia are being hit by an extreme heatwave this year. The hottest season has not yet<br />

begun in countries like India, the Philippines, Cambodia and Thailand, but the temperatures are already<br />

soaring up to 50 degrees Celsius. The perceived temperatures are even higher and worse is feared for the<br />

months of May and June, which are considered particularly hot. Experts warn of massive health issues and<br />

many people report that breathing becomes close to impossible. Authorities are warning people not to stay<br />

outside for long periods and schools are closed in some places. Many countries in the region have already<br />

suffered fatalities and sustained high temperatures will cause further deaths. Experts warn of more dire<br />

consequences, such as extreme drought in some of the world's most densely populated regions. They are<br />

therefore calling on governments to take further measures and preparations against human-caused global<br />

warming. It is the poor in particular who are suffering from the heat and who will continue to do so. Due to<br />

government restrictions that limit outdoor activities, farmers and construction workers are particularly<br />

affected in their daily work. Of course, this also means a loss of income, which in turn may lead to hunger.<br />

TEXT: JULIA MARIA KORN<br />

topos <strong>127</strong> 011

Cities<br />

Our increasingly hot cities and metropolises affect everyone, regardless of their origin,<br />

skin color or other characteristics – or so you might think. But far from it, because<br />

as with many other things, marginalized groups that are already weakened<br />

suffer particularly from the increasingly hot cities. How urban heat kills minorities<br />

and what can be done about it.<br />

MORGANE LLANQUE<br />

topos <strong>127</strong> 019

heat<br />

In 2018 and 2019 the streets of Los Angeles were<br />

dyed white, making for bizarre pictures of dancing<br />

palm tree shadows on chalky avenues. Yet it<br />

was not snowflakes covering the streets, but paint.<br />

In an experiment to tackle urban heat islands<br />

(UHI) in cities, the City of Angels decided to coat<br />

some streets in CoolSeal, a bright paint designed<br />

originally for the military to disguise airplanes.<br />

The very costly paint is aimed to reflect back sunrays<br />

and heat to the atmosphere, in contrast to the<br />

dark-colored asphalt of a usual street, which absorbs<br />

between 80 and 95 percent of the sun's rays,<br />

heating up not just the streets themselves but the<br />

entire surrounding area. This heat also leads to a<br />

higher demand of energy, since more air conditioning<br />

is needed, which in turn is bad for the environment.<br />

This so-called urban heat island effect<br />

can add up to 22 degrees Fahrenheit to the average<br />

air temperature in a city, compared to the surrounding<br />

area, according to the U.S. Environmental<br />

Protection Agency EPA.<br />

This heat is deadly.<br />

When young children, old or sickly people are<br />

exposed to extreme heat, they can suffer heat<br />

exhaustion and heat stroke. Hot temperatures<br />

can also contribute to deaths from heart attacks,<br />

strokes, and other forms of disease. These<br />

impacts are made worse by humidity. Normally<br />

the human body can cool down by sweating,<br />

but this mechanism is compromised by increasing<br />

levels of moisture in the atmosphere,<br />

itself a result of global warming. According to<br />

data from NASA's jet propulsion lab, heat stress<br />

has been the leading cause of weather-related<br />

deaths in the United States, the country with<br />

the most extensive research on the subject,<br />

making Urban Heat more deadly than hurricanes<br />

or earthquakes. In the United States the<br />

number of heat related deaths rose to 1700 in<br />

2022. In Europe, where air conditioning is very<br />

rare in residential housing, 60,000 people died<br />

as a consequence of heat related health issues in<br />

2022 according to the WHO.<br />

But what most statistics don’t tell you is that it is<br />

not only age that affects the risk of dying from urban<br />

heat, but also race, gender and wealth.<br />

The gender and race gap of urban heat<br />

As far back as 2013, a US study documented<br />

that not only countries in the global south but<br />

also western neighborhoods with minorities<br />

and underprivileged populations experience<br />

higher temperatures. The study of 108 urban<br />

areas in the United States suggests that predominantly<br />

non-white neighborhoods were<br />

hotter than the neighborhoods with a white<br />

majority, some by nearly 13 degrees Fahrenheit.<br />

This inequality is exacerbated by the fact<br />

that non-white and lower income households<br />

not only contribute less to global carbon<br />

emissions, they also have fewer resources to<br />

020 topos <strong>127</strong>

heat<br />

FIGHTING THE HEAT<br />

WITH GREENERY<br />

AND CLAY<br />

JULIA TREICHEL<br />

026 topos <strong>127</strong>

1<br />

Located in a hot<br />

climate, the bustling,<br />

concrete-built center of<br />

Ouagadougou heats up<br />

quickly when the sun<br />

shines. Traditional<br />

materials are being<br />

tested to cool down the<br />

city in future.<br />

Photo: Helge Fahrnberger via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0 DEED<br />

topos <strong>127</strong> 027

Monsoon and Harmattan – these two powerful winds primarily determine the climate in<br />

Burkina Faso. And thus also the changing scenery of the landscape. While the monsoon<br />

blowing from the southwest brings warm, humid air and precipitation in summer, the<br />

trade wind Harmattan from the Sahara causes the long dry season in winter. How a<br />

country where the sun shines frequently and rain is a rare resource tackles the challenges<br />

of global warming with clay and green.<br />

Burkina Fasos’ climate zones reflect these influences. In the far north, in<br />

the Sahelian zone, there is a warm desert climate in which rainfall can be<br />

less than 600 mm per year. The rainy season here sometimes lasts less<br />

than two months and temperatures often rise to over 40 degrees during<br />

the dry season. The Sudanese zone in the south, on the other hand, is<br />

characterized by a tropical savannah climate. Here, the rainy season lasts<br />

six months and the monsoon brings rainfall of up to 1100 mm per year to<br />

the southern regions. Between the two extremes, the Sudano-Sahelian<br />

zone - about half of the country - is subject to a warm, semi-arid climate.<br />

Monsoon and harmattan and the balancing act of subarid and subhumid<br />

zones from north to south determine the country's biodiversity and ecological<br />

systems. But in the age of the Anthropocene, these powerful factors<br />

are not the only ones: "Beside these factors, undoubted in their effect,<br />

man is nowadays the main determinant affecting biodiversity with regard<br />

to: demographic growth, pressure on natural resources, socio-cultural<br />

practice, ect.", is how Adjima Thiombiano and Dorothea Kampmann, editors<br />

of the Biodiversity Atlas of West Africa, describe the relevance of human<br />

influence.<br />

The human impact<br />

According to UN Habitat, the African continent has the fastest urbanization<br />

rate in the world. In 2010, the report 'State of African Cities 2010,<br />

Governance, Inequalities and Urban Land Markets' stated that the urbanization<br />

process in the regions south of the Sahara was particularly rapid. At<br />

that time, UN Habitat predicted an 81 percent increase in the population<br />

of Burkina Faso's capital Ouagadougou by 2020 - from 1.9 million in 2010<br />

to 3.4 million in 2020. A rapidly growing population within a short period<br />

of time inevitably has an impact on the shape of the city. In Ouagadougou,<br />

for example, there is an increasing fragmentation of rural areas and the development<br />

of informal housing estates on the outskirts of the capital. This<br />

urbanization process has unavoidable consequences for the ecosystem.<br />

In their paper 'Intensity Analysis for Urban Land Use/Land Cover Dynamics<br />

Characterization of Ouagadougou and Bobo-Dioulasso in Burkina<br />

Faso' from 2023, Valentin Ouedraogo, Kwame Oppong Hackman, Michael<br />

Thiel and Jaiye Dukiya criticize, among other things, an increase in<br />

impermeable surfaces at the expense of natural vegetation and water bodies<br />

with serious consequences: "The urbanization process causes the<br />

transformation of permeable surfaces into impermeable surfaces, including<br />

concrete and asphalt, which reduce the infiltration capacity of the soil<br />

and increase runoff and the amount of flooding.“<br />

To understand the changes in Burkina Faso, the four scientists examined<br />

the change in land use in the country's two largest cities between 2003 and<br />

2021. They found that rapid urbanization over this period had led to a<br />

78.12% increase in built-up areas in the capital; at the expense of agricultural<br />

land, 42.24% of which was lost over the same period. As the human<br />

footprint in cities increases, so does the risk of environmental hazards.<br />

These include flooding, for example, but also the urban heat island effect.<br />

Ouagadougou, in the center of the country, has a tropical climate with<br />

average monthly temperatures between 20 and 30 degrees Celsius. The<br />

results of climate simulations for the period 2010-2050 predict an increase<br />

in the average annual temperature of at least 1 degree. This was<br />

the conclusion of the international EU project CLUVA (Climate Change<br />

and Urban Vulnerability in Africa), which ran from 2011-2013. The scientists<br />

also described an increase in both the frequency and the duration<br />

of droughts. Heatwave episodes could increase from the current average<br />

of 6 days to 17 days.<br />

The situation is particularly precarious in the informal outdoor areas<br />

without formal infrastructure. These areas have the hottest temperatures<br />

028 topos <strong>127</strong>

heat<br />

both during the day and at night. In the northeast of the city center, on the<br />

other hand, is the Bangr'weogo City Park, a large area of community forest<br />

that borders the central reservoirs. This area in turn connects to the<br />

river vegetation zones that lead out of the city. The linear canals allow<br />

fresh air to reach the northern part of the city center.<br />

Measurement results for the Urban Heat Island effect<br />

A 2013 study by Jenny Lindén, the University of Gothenburg and the Direction<br />

de la Météorologie Nationale in Ouagadougou took a closer look at<br />

the temperature development in the city. Measurements in areas with different<br />

vegetation, buildings, road surfaces, open terrain and bodies of water<br />

were used to determine which areas of the city heated up the most.<br />

They were able to register the most significant temperature differences at<br />

night. Areas with vegetation were five to nine degrees Celsius cooler than<br />

those without vegetation. The strong effect in the evening hours is attributed<br />

to evaporative cooling. The researchers also found that the heat island<br />

in the city center was less than two degrees Celsius warmer than the rural<br />

surroundings. The most striking finding of the study was that areas with<br />

vegetation within the city were cooler than the open cultivated landscape<br />

outside the city center. The analysis of the results shows that vegetation is<br />

therefore the most important factor for the night-time urban climate in<br />

Ouagadougou, while the impact of built-up and paved areas is limited.<br />

During the day, the temperature differences recorded at the individual<br />

measurement locations were generally smaller. Overall, the researchers<br />

were unable to detect any effect of shading in the city center. In principle,<br />

taller buildings absorb and reflect more heat, which increases the temperature<br />

of a street, but from around 3 storeys upwards they begin to cool the<br />

street by shading it. Today, Ouagadougou is a melting pot of different architectural<br />

styles. You will find elegant glass office buildings next to colorful<br />

markets covered with corrugated iron. International influences are<br />

unmistakable, but are combined with traditional building styles. In general,<br />

Ouagadougou has a rather open building structure. This may therefore<br />

have neither a particularly positive nor negative effect on the urban<br />

heat island effect of the capital, the researchers assume in their paper.<br />

The added value of traditional construction methods<br />

This is astonishing in comparison to other metropolitan areas around the<br />

world. Last year, for example, the New York City Council published a report<br />

according to which inner-city temperatures in places away from<br />

large green and water areas are 4 to 8 degrees Celsius higher than the average<br />

value. Although temperatures in Ouagadougou are higher than in<br />

New York, the urban heat island effect is lower in Burkina Faso's capital.<br />

This may in fact be related to the traditional building materials used.<br />

Like mirrors, fully glazed façades deflect most of the solar radiation<br />

downwards, towards other buildings or the road surface. Depending on<br />

the material, this absorbs the radiation and emits it again as heat. Depending<br />

on factors such as the facades of other buildings and the width of<br />

the street, the heat is literally trapped at street level. In a study by the École<br />

de Technologie Supérieure, researchers investigated the extent to which<br />

the composition of asphalt has an influence on surface reflection and thus<br />

on the heat island effect. They found that the use of yellow clay brick as a<br />

chip seal aggregate increases reflectivity by 250 percent and can therefore<br />

reduce the surface temperature by 23 percent. In Burkina Faso, the main<br />

building material is clay – this may have a negative impact on the urban<br />

heat island effect.<br />

"Earthen construction is our heritage," the National Geographic quotes<br />

Sanu, head of the village of Koumi in the southwest of the country, in an<br />

article from 2023. "For thousands of years, these houses have enabled us<br />

to live a good life. Why should we change that, especially now when we<br />

urgently need them?" He rightly speaks out against supposed modernization<br />

processes that are detrimental to local conditions. In their paper 'Development<br />

of Bioclimatic Passive Designs for Office Building in Burkina<br />

Faso', Abraham Nathan Zoure from Tianjin University and Paolo Vincenzo<br />

Genovese from Zhejiang University also criticize the general application<br />

of "inappropriate standards that were originally developed for the<br />

needs of other (Western) environments". These include, for example, the<br />

increasing use of concrete and steel, but also the intensive use of air conditioning<br />

systems. Around 45 percent of the energy consumed in buildings<br />

is used to maintain thermal comfort inside. Instead, they recommend<br />

relying on natural ventilation through shading devices and using<br />

building materials with high thermal capacity - such as clay - to maintain<br />

generally moderate temperatures during the day. These are all aspects that<br />

can have a lasting impact on the city's indoor spaces, but also on its outdoor<br />

spaces in the long term.<br />

As Jenny Lindén's study makes clear, however, the greatest potential in<br />

the fight against urban overheating lies not in the building construction<br />

sector, but in the consistent expansion of blue-green infrastructure. In<br />

topos <strong>127</strong> 029

BATLLEIROIG<br />

MERGING CITY<br />

AND NATURE<br />

Designing open spaces as pleasant and comfortable areas that enhance<br />

environmental quality and are free from pollution is essential. Leveraging<br />

seasonal climate variations in the design of these spaces is key to<br />

moderating temperatures during the hottest and coldest periods, allowing<br />

for the enjoyment of public spaces throughout the year.<br />

050 topos <strong>127</strong>

commentary<br />

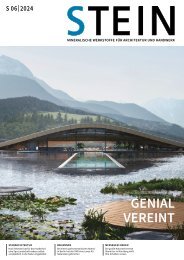

1<br />

Image: Batlleiroig<br />

1. Three projects were<br />

carried out in Esplugues<br />

de Llobregat: The<br />

urbanization of the<br />

Finestrelles sector (1),<br />

the transformation of<br />

the Avinguda dels Paisos<br />

Catalans (2) and the<br />

remodelling of the<br />

Elisabeth Eidenbenz<br />

roundabout (3).<br />

The primary objective of these designs is to mitigate<br />

urban heat islands, thereby addressing the<br />

climate emergency and enhancing health and<br />

well-being in urban areas. This is achieved<br />

through the use of various tools, including primordial<br />

geography, water, vegetation, permeability,<br />

and materiality. By integrating these elements,<br />

the designs create sustainable urban environments<br />

that not only reduce rising temperatures<br />

but also improve the overall quality of urban life.<br />

Prioritizing the creation of large green areas improves<br />

air quality, ventilation, and reduces noise<br />

pollution. Incorporating trees and landscaped<br />

areas into urban design helps regulate environmental<br />

hygrometric conditions, relative humidity,<br />

and the feeling of air freshness. Planting deciduous<br />

trees in public spaces is advisable to<br />

maximize sunlight in winter and provide ample<br />

shade during summer.<br />

The distribution of large tree masses should enhance<br />

ventilation corridors in public spaces. Additionally,<br />

it is important to manage the topography<br />

to optimize rainwater capture and retention<br />

in green areas. Hard paved surfaces should be<br />

minimized, and synergies with nearby natural<br />

spaces should be established through green corridors,<br />

thereby promoting biodiversity in the city.<br />

Green infrastructure plays a crucial role in the<br />

resilience of cities against the urban heat island<br />

effect. Open spaces, as major structural elements<br />

of the city, have the potential to become bioclimatic<br />

areas capable of regulating temperature<br />

and humidity. Connecting these green infrastructures<br />

with the original geography, grouping<br />

them into areas with sufficient critical mass, and<br />

managing their vegetation are key aspects that<br />

can reduce temperatures by up to 3°C.<br />

For over 40 years, Batlleiroig has implemented<br />

various strategies and solutions in our projects<br />

aimed at enhancing the resilience of our urban<br />

fabric. One example is the planning and urbanization<br />

project of the Finestrelles sector in Esplugues<br />

de Llobregat (Fig. 1). This proposal<br />

aims to extend the natural park of Collserola.<br />

topos <strong>127</strong> 051