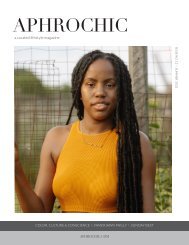

AphroChic Magazine Issue No. 16: Summer 2024

Issue No. 16 of AphroChic Magazine is here with strong summer vibes! Our cover story features country music sensation, Brittney Spencer, and her journey, from navigating discrimination in the country music industry, to singing on Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter album. In Fashion, we explore the life of designer Anne Lowe whose gowns once graced every shop window and grand event, from Madison Avenue salons to Jackie Kennedy’s wedding. Then we invite you to travel with us to Ulster County in upstate New York, where you can literally walk in the footsteps of Sojourner Truth and other notable African Americans. And in Food, experience the Amish-inspired soul food of Chef Chris Scott’s book, "Homage: Recipes + Stories from an Amish Soul Food Kitchen." From the books by Black authors that you need on your summer reading list, to the cultural events and festivals across the African Diaspora that you don’t want to miss, AphroChic Magazine has you covered this summer.

Issue No. 16 of AphroChic Magazine is here with strong summer vibes! Our cover story features country music sensation, Brittney Spencer, and her journey, from navigating discrimination in the country music industry, to singing on Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter album. In Fashion, we explore the life of designer Anne Lowe whose gowns once graced every shop window and grand event, from Madison Avenue salons to Jackie Kennedy’s wedding. Then we invite you to travel with us to Ulster County in upstate New York, where you can literally walk in the footsteps of Sojourner Truth and other notable African Americans. And in Food, experience the Amish-inspired soul food of Chef Chris Scott’s book, "Homage: Recipes + Stories from an Amish Soul Food Kitchen." From the books by Black authors that you need on your summer reading list, to the cultural events and festivals across the African Diaspora that you don’t want to miss, AphroChic Magazine has you covered this summer.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

a curated lifestyle magazine<br />

ISSUE NO. <strong>16</strong> \ SUMMER <strong>2024</strong><br />

HIDDEN STITCHES \ A SOUL FOOD HOMAGE \ NIGERIA REMEMBERED<br />

APHROCHIC.COM

It’s finally that time of year when we feel ourselves moving fully into summer. The weather<br />

is warming, the bright colors of nature are back, and a new issue of <strong>AphroChic</strong> magazine<br />

is here, full of amazing stories and inspiration from across the African Diaspora.<br />

This issue’s cover story, featuring country-music sensation, Brittney Spencer, is a timely intervention into the growing conversation<br />

around Black presence in country music, and the place of African Americans at the very root of American music culture.<br />

Similarly, this issue’s Mood section is a reclamation of the concept, “Black Americana,” replacing the denigrating caricatures and<br />

stereotypes usually associated with the term with pieces made by Black artisans and that reflect our true experience.<br />

Our cover story features Brittney Spencer, the country music sensation who just released her first album, and who can be<br />

heard on Beyoncé's rendition of Black Bird. We follow Brittney's journey to stardom, and the growing conversation around Black<br />

presence in country music, and the place of African Americans at the very root of American music culture.<br />

In Mood, we reclaim the concept of Black Americana, replacing the denigrating caricatures and stereotypes usually associated<br />

with the term with pieces made by Black artisans that truly reflect the Black American experience. And in In Fashion, we<br />

explore the life of designer Anne Lowe, whose gowns once graced every shop window and grand event, from Madison Avenue<br />

salons to Jackie Kennedy’s wedding, yet whose contributions — kept secret then — go largely unknown today.<br />

In City Stories, take a tour with us of scenic Ulster County in upstate New York. Known for its natural splendor, the area is a<br />

deep repository of Black history and culture, from the very beginnings of American slavery to the works of artists, athletes, and<br />

creatives that have changed the world. Staying rural, in Food we experience the Amish-inspired soul food of chef Chris Scott’s<br />

Homage: Recipes and Stories from an Amish Soul Food Kitchen.<br />

We explore the one-of-a-kind watercolor painting of Los Angeles-based artist Kris Keys, whose work presents a truly unique<br />

blend of Japanese influences and Diaspora style. And we take you to Italy for the Venice Biennale where the talents of Nigerian<br />

artists from around the world are on full display.<br />

Finally, we have something to celebrate. <strong>AphroChic</strong>.com is back, brand new, and better than ever. Our newly revamped<br />

website is a virtual home for the African Diaspora, filled with articles to read, brands to explore, videos, books, and hours of music<br />

to nourish your mind and soul. It’s got everything to help you feel safe, welcome, and at home. We welcome you to summer, to our<br />

new home on the web, and to issue <strong>16</strong>. We hope you love it.<br />

Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Founders, <strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

Instagram: @aphrochic<br />

editors’ letter<br />

Jeanine and Bryan at<br />

the historic Hillwood<br />

Museum and<br />

Gardens for a talk on<br />

the Black family home.

SUMMER <strong>2024</strong><br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

Read This 10<br />

Visual Cues 12<br />

Coming Up 14<br />

The Black Family Home <strong>16</strong><br />

Mood 24<br />

FEATURES<br />

Fashion // Hidden Stitches 30<br />

Interior Design // Celebrating Diaspora in Every Room 36<br />

Culture // Nigeria Remembered 58<br />

Food // A Soul Food Homage 70<br />

Entertaining // Glow Up Your Tabletop 76<br />

City Stories // Exploring Two Sides of Black History in Ulster County 86<br />

Sounds // Feels Like Home 100<br />

PINPOINT<br />

Artists & Artisans 106<br />

Lit 112<br />

Who Are You? 114

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

Cover Photo: Brittney Spencer<br />

Photographer: Jimmy Fontaine<br />

Publishers/Editors: Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Creative Director: Cheminne Taylor-Smith<br />

Editorial/Product Contact:<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong>.com<br />

magazine@aphrochic.com<br />

Brand Partnerships and Ad Sales:<br />

Krystle DeSantos<br />

Krystle@aphrochic.com<br />

Contributors:<br />

Ruby Brown<br />

Patrick Cline<br />

Chinasa Cooper<br />

issue sixteen 9

READ THIS<br />

The African Diaspora is a celebration of the global Black community and the cultural diversity within it. This month<br />

in books, we celebrate the unique and complex paths that anyone can take within the Diaspora — there is no "one<br />

size fits all." In Eight Seconds: Black Rodeo Culture, photojournalist Ivan McClellan captures the excitement and<br />

camaraderie of Black cowboy culture. From the country’s longest-running Black rodeo in Oklahoma to bull riding<br />

champion Ouncie Mitchell to the Compton Cowboys, the photos showcase courage, strength, and skill. A Black Girl<br />

in the Middle offers a series of essays by Shenequa Golding that explore what it means to be “kind of in the middle,”<br />

not an overachiever and not the cool girl. It's a funny, wry, heart-twisting look at fitting in and what Black girlhood<br />

and womanhood can be. Darius Rucker has taken a lot of unexpected roads in his life. He was part of a self-described<br />

college party band that exploded into a pop phenomenon known as Hootie & The Blowfish. And then he surprised<br />

his fans by moving into country music, winning a Grammy in 2013 for his solo country album. In Life's Too Short, he<br />

looks back at the left turns — and wrong turns — he's taken to find his own path in the world of music.<br />

A Black Girl in the Middle: Essays on<br />

(Allegedly) Figuring It All Out<br />

by Shenequa Golding<br />

Publisher: Beacon Press. $25<br />

Eight Seconds: Black Rodeo Culture<br />

by Ivan McClellan<br />

Publisher: Damiani. $45<br />

Life's Too Short: A Memoir<br />

by Darius Rucker<br />

Publisher: Dey Street Press. $27<br />

10 aphrochic

Celebrate Black homeownership and the<br />

amazing diversity of the Black experience<br />

with <strong>AphroChic</strong>’s newest book<br />

In this powerful, visually stunning book, Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason explore<br />

the Black family home and its role as haven, heirloom, and cornerstone of Black<br />

culture and life. Through striking interiors, stories of family and community,<br />

and histories of the obstacles Black homeowners have faced for generations,<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong> honors the journey, recognizes the struggle, and embraces the joy.<br />

AVAILABLE WHEREVER BOOKS ARE SOLD

VISUAL CUES<br />

The Thomas House in Eatonville, Fla., one of the endangered historic sites recognized by the National Trust for Historic Preservation.<br />

For the first time in its history, The National Trust for Historic Preservation has highlighted three sites that<br />

are important in the history of African Americans on its list of 11 most endangered historic sites. They include<br />

a West Virginia church, the town of Eatonville, Fla., and Roosevelt High School in Gary, Ind. The idea of the<br />

list is to highlight each site as a cultural destination, to help raise money, and save the structures and places.<br />

Over the last 30 years, the National Trust has saved many endangered places by including them on the annual<br />

list. The New Salem Baptist Church in West Virginia was founded in the 1920s by Black coal miners living in<br />

a segregated camp. The descendants of the church's original parishioners have been pushing to preserve and<br />

restore the church for years. Black residents of Eatonville, Fla., have also been trying to save their town for<br />

decades. One of the first self-governing all-Black towns in the United States, Eatonville was featured in Zora<br />

Neale Hurston’s 1937 novel Their Eyes Were Watching God. She described her hometown as "the city of five lakes,<br />

three croquet courts, 300 brown skins, 300 good swimmers, plenty guavas, two schools, and no jailhouse."<br />

Constructed in 1930, Theodore Roosevelt High School in Gary is one of only three high schools in Indiana<br />

built specifically to serve the educational needs of Black Americans in the Jim Crow era. It was designed by<br />

noted architect William B. Ittner and has many notable alumni including Olympic boxer Charles Adkins, CBS<br />

reporter Emery King, NFL player Gerald Irons, actor Avery Brooks, and members of The Jackson 5. To learn<br />

more about these sites and to help preserve them, go to savingplaces.org.<br />

12 aphrochic

DIVINE<br />

FEMININITY<br />

BY FARES MICUE<br />

P E R I G O L D . C O M

COMING UP<br />

Events, exhibits, and happenings that celebrate and explore the African Diaspora.<br />

AFRAM Baltimore<br />

June 22-23 | Baltimore<br />

AFRAM is one of the largest African American festivals on<br />

the East Coast. Hosted in Baltimore City’s Druid Hill Park on<br />

Juneteenth weekend, this event is attended by over 100,000<br />

each year. Over two days, this free, family-oriented celebration<br />

features music, entertainers, children’s activities, African<br />

drumming, carnival mask-making, food, and more. This year's<br />

lineup of acts includes Busta Rhymes, October London, Alex<br />

Isley, Mya, Big Daddy Kane, Karen Clark-Sheard, and Morris<br />

Day, as well as local bands and performers.<br />

Learn more at aframbaltimore.com.<br />

Essence Festival of Culture<br />

July 4-7 | New Orleans<br />

The iconic Essence Festival celebrates its 30th anniversary<br />

this year with blockbuster acts and events over four days in<br />

July. Entertainment icon Janet Jackson and contemporary<br />

R&B and soul singer Charlie Wilson (formerly of The Gap<br />

Band) are just two of the headliners expected to perform<br />

at Essence Fest. The event also includes the Empowerment<br />

Experience that spotlights dozens of speakers on<br />

thought-provoking topics such as religion, economics, and<br />

education. Vendors will also be set up around New Orleans<br />

with arts and crafts, clothing and jewelry, and collectible<br />

paintings and sculptures that represent the rich culture of<br />

the African Diaspora.<br />

Learn more at essence.com/festival.<br />

CurlFest<br />

July 20 | New York<br />

CurlFest was founded to be the change that was long overdue<br />

in the beauty industry. As its mission statement says, the goal is<br />

"to flip the false narrative around unruly brown beauty, and create<br />

one that accurately showcases the glory of our crowns, the<br />

richness of our skin, and the joy of our culture." <strong>No</strong>w in its 14th<br />

year, it is the largest natural beauty festival in America, and is<br />

100% owned by Black women, with over 75,000 attendees<br />

from around the world. This year's event includes Beauty Row,<br />

with beauty brands that offer activations, deals, giveaways,<br />

games, and more; DJs and musical acts; the Empowerment<br />

stage, with motivational speakers; as well as vendors and food<br />

that highlight the best of the Diaspora.<br />

Learn more at curlfest.com.<br />

14 aphrochic

BALTIMORE<br />

S P E A K S<br />

B L A C K<br />

C O M M U N I T I E S<br />

C O V I D - 1 9<br />

A N D T H E<br />

C O S T O F<br />

N O T D O I N G<br />

E N O U G H<br />

W R I T T E N A N D D I R E C T E D B Y<br />

B R Y A N M A S O N A N D J E A N I N E H A Y S<br />

V I S I T O U R W E B S I T E A T B A L T I M O R E S P E A K S . C O M

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

The House That Built Black History:<br />

The Carter G. Woodson House<br />

It’s something less than a secret, the value we place on Black homes. At <strong>AphroChic</strong>,<br />

we have explored their roles, both in our own families and in general, as bastions of<br />

culture, wellsprings of community, and part of the vital tissue that connects families<br />

from one generation to the next. But sometimes a home is even more than all that.<br />

Sometimes a home is a waypoint in history, the birthplace of a movement.<br />

On July 18, 1922, when Carter G. Woodson purchased his<br />

home on 1538 Ninth Street N.W. in Washington, D.C., he was<br />

in the process of retiring. Though not yet 50, Woodson had<br />

already been teaching for more than 20 years, had founded<br />

a society and was the author of several books. Despite this<br />

list of accomplishments, however, he was retiring from the<br />

profession of education so that he might more fully embrace<br />

educating as his mission — one that would last the rest of his<br />

life, with implications that continue to resonate more than a<br />

century after that day.<br />

Woodson’s name is familiar to many, but often only<br />

in passing. It is mentioned at least once every year during<br />

February, as he is justly remembered as the father of Black<br />

— formerly Negro — History, where once he was hailed as<br />

its “High Priest.” Yet the life that he led and the home that<br />

he built, not only for himself but for a generation of budding<br />

scholars and creatives, and the whole concept of Black historicity,<br />

deserves far more attention.<br />

Carter Godwin Woodson was born on December 19, 1875,<br />

in New Canton, Va., the fourth of nine children born to James<br />

The Black Family Home is an<br />

ongoing series focusing on the<br />

history and future of what home<br />

means for Black families.<br />

This series inspired the new book<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong>: Celebrating the Legacy<br />

of the Black Family Home.<br />

Words by Bryan Mason<br />

Images by Bryan Mason and courtesy of the Library of<br />

Congress and the National Park Service<br />

<strong>16</strong> aphrochic

The Carter G. Woodson<br />

Home National Historic<br />

Site in Washington D.C.,<br />

slated to open in <strong>2024</strong>.

18 aphrochic

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

Henry and Anne Eliza Woodson, both formerly enslaved. He grew<br />

up hungry, working the family’s six-acre farm while his father, a<br />

carpenter and Civil War veteran, earned money laying foundations<br />

for homes. Though he would never learn to read himself,<br />

Woodson credited his father with the best part of his education.<br />

Carter remembered the lessons of James Henry Woodson<br />

in 1932 in an article for the Chicago Defender called And The Negro<br />

Loses His Soul. “This former slave,” he wrote, “an illiterate man,<br />

taught me that you do not have to wait until you die to think of<br />

losing your soul. He insisted that when you learn to accept insult,<br />

to compromise on principle, to mislead your people, you have lost<br />

your soul. ... He often said to me, ‘I had to do these things when I<br />

was a slave. If I continue to do them, I am not a free man. [If] you<br />

cannot look the oppressor in the eye and say, ‘Sir, I am your equal.’<br />

Neither he nor you will believe it,’ ”<br />

Later, when the family relocated to West Virginia, Carter and<br />

his older brother Robert worked together building the railroads<br />

and completed a six-year stint in the coal mines at Nuttallburg.<br />

Woodson held other jobs as well, including time spent as a garbage<br />

collector. It was not until he was 20 that his formal education<br />

began in earnest. Woodson attended Frederick Douglass High<br />

School, an all-Black institution in Huntingdon, W.V.<br />

From Huntingdon, Woodson’s education soared. After<br />

graduating from Douglass within a year, he served at a school in<br />

Winona, W.V., teaching the children of Black miners. In 1900, he<br />

replaced his cousin Carter H. Barnett, founder of West Virginia’s<br />

first Black newspaper, as principal of Douglass High School,<br />

ahead of receiving his teacher’s certificate in 1901. By 1903, he had<br />

a bachelor of laws degree from Brea College, and at the end of that<br />

year departed for the Philippines, where he was employed by the<br />

U.S. War Department until early 1907.<br />

Following his time in the Philippines, Woodson embarked<br />

on journeys around the world, visiting Africa, Asia, and Europe,<br />

where he spent several months, including time spent studying<br />

history at the Sorbonne. Returning to the U.S., he landed in<br />

Chicago, and in the summer of 1908 received a master’s degree<br />

in history, romance languages, and literature from the University<br />

of Chicago. Afterward, he would enroll as a doctoral student at<br />

Harvard University.<br />

In 1909, Woodson arrived in Washington D.C. to take up<br />

teaching positions, first at Armstrong Manual Training School<br />

and later teaching history as well as Spanish, English, and French,<br />

at M Street High School. And in 1912, at the age of 37, he succeeded<br />

W.E.B. Du Bois, becoming the second African American to<br />

graduate from Harvard with a Ph.D.<br />

By September of 1915, Woodson was back in Chicago. He had<br />

written his first book, The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861, and<br />

Carter G. Woodson<br />

joined with James E. Stamps, Alexander L. Jackson, and George<br />

Cleveland Hall to found the Association for the Study of Negro<br />

Life and History (ASNLH) — a group dedicated to collecting,<br />

preserving, and disseminating information and artifacts pertaining<br />

to Black American history. In 19<strong>16</strong>, he would found The<br />

Journal of Negro History. Though his career as an educator would<br />

continue for several more years — and reach new heights — it was<br />

the mission of the ASNLH and the journal that would take him to<br />

Ninth Street.<br />

In the intervening years, Woodson would become principal<br />

of the Armstrong Manual Training School and publish his second<br />

book, A Century of Negro Migration, both in 1918. From 1919 to 1920<br />

he would serve as dean of the School of Liberal Arts at Howard<br />

University, leaving to become dean at West Virginia Collegiate<br />

Institute. He held the position until 1922, releasing his third book,<br />

The History of the Negro Church, in 1921.<br />

Also completed in 1921 but unreleased and forgotten until<br />

it was rediscovered in 2005, The Case of the Negro was a direct<br />

challenge to the Eurocentric and white supremacist underpinnings<br />

of the American academy, the field of historical study, and<br />

American culture as a whole. The collection of essays demanded<br />

an extensive overhaul to the American social order with scathing<br />

commentary aimed at both white America, which collectiveissue<br />

sixteen 19

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

A vintage reproduction of Woodson's office-home, including the Underwood typewriter he would have used in writing his many books and publications.<br />

20 aphrochic

ly enjoyed the Negro’s plight and the<br />

Black middle-class “elites” who facilitated<br />

it. It is thought that the manuscript was<br />

abandoned because its tone would have<br />

endangered the reputation of the ASNLH<br />

and its relationship with white philanthropic<br />

organizations and individuals.<br />

Yet as Woodson severed ties with many<br />

of these philanthropists moving into the<br />

early 1930s, he more openly and frequently<br />

shared his views on a broad number<br />

of topics. The book remains a welcome<br />

reminder that Woodson, a member of the<br />

NAACP, and A. Philip Randolph’s economically-focused<br />

Friends of Negro Freedom<br />

organization, was every bit the activist that<br />

he was the scholar.<br />

There was no fanfare heralding<br />

Woodson’s acquisition of the house on Ninth<br />

Street. <strong>No</strong> formal announcement was made<br />

until the address was quietly listed as the<br />

new headquarters of the ASNLH in the July<br />

issue of The Journal of Negro History, a year<br />

after the purchase was made. A three-story<br />

affair, the divisions of Woodson’s “office<br />

home,” as it was frequently and affectionately<br />

called, neatly portray the outline of<br />

the scholar’s life, as well as his commitment<br />

to the cause of Black history which was<br />

never far from him.<br />

The first floor of the home was<br />

reserved for the operations of the ASNLH,<br />

The Journal of Negro History, and eventually<br />

The Negro History Bulletin, which Woodson<br />

would create in 1937. It was also the headquarters<br />

of Associated Publishers, which<br />

he established in 1921 to ensure publication<br />

for works by Black scholars — including<br />

women — that were rejected by other publishers,<br />

and the name of which was proudly<br />

borne on a sign adorning the front of the<br />

home — a sign 11-and-a-half-feet wide.<br />

The first floor of the house contained<br />

the reception area, where secretaries<br />

worked and greeted the office’s frequent<br />

guests, the book storage room, which is<br />

reputed to have been filled to the ceiling<br />

with books at all times, and the “packing<br />

and shipping” room where the various publications<br />

that Woodson oversaw — as well as<br />

books and other materials — were prepared<br />

and sent. It was also the room where a<br />

young Langston Hughes would learn the<br />

meaning and value of hard work.<br />

“In the mid-1920s when I worked for<br />

Dr. Woodson, he set an example in industry<br />

and stick-to-it-tiveness for his entire staff<br />

since he himself worked very hard,” the<br />

poet remembered. “He did everything<br />

from editing The Journal of Negro History<br />

to banking the furnace, writing books to<br />

wrapping books…His own working day<br />

extended from early morning to late at<br />

night. Those working with him seldom<br />

wished to keep the same pace.”<br />

The second floor of the home housed<br />

Woodson’s office. It was there that he would<br />

have worked as he imagined the beginning<br />

of Negro History Week, which began in<br />

1926, and where he would have written his<br />

most seminal text, The Mis-Education of the<br />

Negro, published in 1933.<br />

The second floor also included the<br />

kitchen, open to those who worked at<br />

the office for lunches, breaks, and occasional<br />

card games. Also on that floor<br />

was Woodson’s library, considered the<br />

foremost in the nation for Black history.<br />

Visiting scholars spent hours researching<br />

and studying its catalog, and Woodson<br />

himself used it as he mentored a generation<br />

of groundbreaking educators, historians<br />

and scholars including Lorenzo Johnston<br />

Greene, Zora Neale Hurston — who worked<br />

as an investigator for Woodson, collecting<br />

folklore and examining records in<br />

Florida and elsewhere — and Mary McLeod<br />

Bethune, the pioneering educator who<br />

served for years as the president of the<br />

ASNLH. Even after his death in 1950, the<br />

issue sixteen 21

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

library remained open and in use, even serving as a research site<br />

for what would eventually become the 1954 Supreme Court case,<br />

Brown v. Board of Education.<br />

The third floor consisted of Woodson’s personal quarters<br />

and were reserved for him alone. They included little more<br />

than a living room and a bedroom, where he was found to have<br />

passed away from a heart attack in his sleep on April 3, 1950.<br />

That he required so little for himself, even going so far as to pay<br />

employees with families double what he himself was making, and<br />

often forgoing any salary at all from his organizations, is perhaps<br />

indicative of his childhood and what he felt he needed to comfortably<br />

survive. But even more likely, it is reflective of his perspective<br />

on his work and its purpose, and on what it is that truly gives value<br />

to a person’s life. As he once wrote:<br />

A poor man can write a more beautiful poem than one<br />

who is surfeited. The man in the hovel composes a more<br />

charming song than the one in the palace. The painter in the<br />

ghetto gets an inspiration for a more striking painting than<br />

his landlord can appreciate. The ill fed sculptor lives more<br />

abundantly than the millionaire who purchases the expression<br />

of thought in marble and bronze.<br />

The impact of Carter G. Woodson’s life continues to be felt<br />

today in more than the week of historical reflection he envisioned<br />

and the month he helped to found — though that alone would<br />

be sufficient. The organization he created and his first publication<br />

still exist today, modernized as the Association for the Study<br />

of African American Life and History and The Journal of African<br />

American History.<br />

The house at 1538 Ninth Street N.W. in Washington D.C.<br />

remained the headquarters of the ASNLH until 1971. In 1976, it was<br />

declared a National Historic Landmark. In 2003, Congress authorized<br />

the purchase of the home from the ASNLH. And in 2005, the<br />

National Park Service completed the sale, enshrining the home<br />

as its 389th unit. Since then, the home has been under continual<br />

renovation, with efforts hindered in 2011 by both a 5.8 magnitude<br />

earthquake and Hurricane Irene. Nevertheless, extensive repairs<br />

continue to be undertaken, with a completion date projected<br />

for some time this year and including the creation of a museum<br />

exhibit dedicated to the story of this remarkable home of Black<br />

history. Until it reopens, a visit to the home can still be an invaluable<br />

experience, looking at the exterior where so much Black<br />

history took place, and taking steps down the street to the Carter<br />

G. Woodson Memorial Park where a statue of this iconic Black<br />

figure waits. AC<br />

22 aphrochic

Opposite page: <strong>Issue</strong>s of Woodson's The Negro History Bulletin.<br />

Above: The memorial to the "Father of Black History" at the Carter G. Woodson Memorial Park.<br />

issue sixteen 23

MOOD<br />

Black Americana Reclaimed<br />

The term “Black Americana” typically refers to a host of racist memorabilia created<br />

by white Americans, with roots in the days surrounding the death of Reconstruction.<br />

In 1877, Rutherford B. Hayes made a backroom deal where, in exchange<br />

for the presidency of the United States, he would abandon Reconstruction laws<br />

and allow segregation, ushering in the Jim Crow era. While African Americans<br />

had made significant progress during Reconstruction, establishing our own communities,<br />

owning land, building homes, starting businesses, attaining degrees,<br />

and finding professions, Jim Crow was a devastating, a de facto return to slavery<br />

enforced by the state. To help justify the nation’s new policy of segregation, products<br />

of every type flooded the U.S. market with the goal of reenforcing the myths<br />

of “white supremacy.” The products depicted African Americans as sub-human,<br />

bestial creatures not fit to be citizens of the nation built upon our backs. Hundreds<br />

of thousands of pieces featuring constructed tropes of Black identity —<br />

sambo, pickaninny, topsy — born from the minds of white segregationists were<br />

released into the consumer market. Historian Henry Louis Gates reports that,<br />

“everyday, ordinary consumer objects...including post cards and trading cards,<br />

teapots and tea cozies, children’s banks and children’s games, napkin holders<br />

and pot holders, clocks and ash trays, sheet music and greeting cards, consumer<br />

products such as Aunt Jemima pancake mix and Gold Dust washing powder...<br />

tobacco...banks...songs...puzzles, dolls, Valentine’s Day cards, and virtually every<br />

form of advertisement for a consumer product” were created for this task. Today,<br />

these products can still found on an episode of Antiques Roadshow; at a a stand<br />

at Brimfield; or among the antique offerings on 1stDibs. And while you may find<br />

them in interiors, including African American homes, it’s important to note that<br />

these pieces are not Black Americana. In fact, they have very little to do with Black<br />

culture at all. They are one piece in a larger game focused on our oppression.<br />

They do not tell our story, but instead rob us of our dignity, legacy, and culture.<br />

Moreover, they continue to serve as the basis for reductionist tropes that continue<br />

to be force fed to our communities in various guises today and across every form<br />

of media. There may have been a time when these were the only or most readily<br />

available depictions of Black life for the home — but not anymore. So in this issue’s<br />

Mood, we’re redefining Black Americana. <strong>No</strong> longer a celebration of delusions<br />

on Black identity, we present ourselves as we are — creative, beautiful, genius, a<br />

melange of cultures, a people dedicated to freedom and liberty. These are pieces<br />

that can help you tell the real story of the Black culture of America, and that can<br />

be beautifully displayed in your home as a reclamation of the collective story we<br />

are building together.<br />

Otto Studio Jamboree<br />

Wallpaper starting at<br />

$56<br />

thisisottostudio.com<br />

Red Black and Blue<br />

Plaid Maasai Blanket<br />

$40<br />

nubianradiance.com<br />

24 aphrochic

Flipper’s Quadz by<br />

Usher Handmade<br />

Skates $1,450<br />

flippers.world<br />

The Fire Next Time by<br />

James Baldwin and<br />

Steve Schapiro $50<br />

amazon.com<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong> Silhouette<br />

Red Pillow $149<br />

perigold.com<br />

I Am Human Painting by Idris Habib<br />

$10,000<br />

saatchiart.com<br />

Mami Wata Surf<br />

Sebenza Midlength<br />

Surfboard $1,800<br />

mamiwatasurf.com<br />

issue sixteen 25

MOOD<br />

The Sister’s Keeper<br />

Handbag $188.10<br />

trublulegacy.com<br />

Faith Ringgold Woman<br />

Freedom <strong>No</strong>w Diptych<br />

$380 moma.org<br />

BLACK [AF]: America’s<br />

Sweetheart Graphic<br />

<strong>No</strong>vel $9.99<br />

amazon.com<br />

Rebecca Maria One-of-<br />

One Sculpture<br />

rebeccamaria.studio<br />

contact for price<br />

Brownie by Kerry<br />

James Marshall $750<br />

1stdibs.com<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong> Ndop White<br />

and Blue Pillow $149<br />

perigold.com<br />

26 aphrochic

Derrick Adams<br />

“Floater 108” Plate<br />

$1,350<br />

artsy.net<br />

Outkast Stankonia<br />

Vinyl Record $29.98<br />

amazon.com<br />

Black Fives x PUMA<br />

Cable Knit Pennant<br />

Cardigan $70 ebay.com<br />

House of Aama<br />

Retro Swim Two-<br />

Piece Navy $350<br />

houseofaama.com<br />

Sam Wilson: Captain America #1<br />

Asrar Hip-Hop Variant $26.95<br />

ebay.com<br />

That Flag Picture Book<br />

$18.99<br />

amazon.com<br />

issue sixteen 27

FEATURES<br />

Hidden Stitches | Celebrating Diaspora in Every Room | Nigeria<br />

Remembered | A Soul Food Homage | Glow Up Your Tabletop |<br />

Exploring Two Sides of Black History in Ulster County | Feels Like Home

Fashion<br />

Hidden<br />

Stitches<br />

The Legacy of Ann Lowe<br />

Leafing through the opening pages of Ann Lowe: American Couturier, an<br />

extension of the namesake Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library exhibition,<br />

readers encounter an image of a petite Black woman with an air of poise and<br />

elegance. Dressed in medium-height black heels and a knee-length black skirt<br />

suit, her ensemble is completed by a brooch-like ornament pinned to her chest<br />

and a hint of a red peeking through near her neckline. Her face, framed by<br />

glasses and a black narrow-brimmed hat, exudes joy and pride as she works on<br />

a wedding dress fitted to a dress form that towers over her. This remarkable<br />

woman is Ann Lowe.<br />

Words by Krystle DeSantos<br />

Photos provided by Rizzoli<br />

30 aphrochic

Fashion<br />

Born in Clayton, Ala., in 1898 to Jane Sapp Lowe<br />

and Jack Lowe, Ann Lowe was introduced to fashion<br />

and dressmaking in her childhood by her mother and<br />

grandmother, both of whom ran a successful dressmaking<br />

shop in the early 1900s and worked for prominent<br />

families in the South. By age five, Lowe had already begun<br />

learning how to sew and developed a keen eye for design<br />

and passion for couture. She often transformed scraps<br />

of leftover fabric scraps into flowers, foreshadowing her<br />

signature floral embellishments as a designer. Tragically,<br />

when Lowe was <strong>16</strong> her mother passed away, leaving her<br />

to complete a dressmaking commission for the governor<br />

of Alabama’s wife — a turning point that marked the start<br />

of her career.<br />

Despite her undeniable talent, Lowe faced racial<br />

discrimination that limited her opportunities to pursue<br />

formal training. <strong>No</strong>netheless, in 1917 she moved to New<br />

York City and studied at the S.T. Taylor Design School.<br />

Though her time there was not without challenges —<br />

she was segregated from her peers and required to work<br />

separately from white students — Lowe's meticulous<br />

attention to detail and passion for her craft allowed her to<br />

excel and pushed her to new heights.<br />

After graduating in 1919, Lowe moved to Tampa, Fla.,<br />

and opened her first dress salon. She skillfully merged<br />

contemporary fashion trends with traditional southern<br />

sophistication, earning acclaim for her exquisite masterpieces<br />

featuring delicate embroidery and intricate<br />

beadwork. By 1928, Lowe had saved $20,000 from her<br />

salon's earnings and she relocated back to New York<br />

City with her son, settling in Harlem. Her work quickly<br />

gained recognition among elite social circles, making her<br />

the designer of choice for many wealthy white families,<br />

including the Rockefellers, Roosevelts, and du Ponts.<br />

Lowe also designed for prominent Black clients, such as<br />

Idella Kohke, a member of the Negro Actors Guild, and<br />

pianist Elizabeth Mance.<br />

One of her most notable achievements was<br />

designing the wedding dress and bridesmaids' dresses<br />

for Jacqueline Lee Bouvier, who would later become<br />

Jackie Kennedy, wife of the 35th President of the United<br />

States, John F. Kennedy. However, just one week before<br />

the wedding, Lowe's workroom flooded, destroying<br />

several dresses, including Jackie's wedding gown.<br />

Lowe and her team worked tirelessly around the clock<br />

to recreate the dresses, never informing the family<br />

of the incident or charging them for added materials.<br />

GET THE BOOK<br />

Anne Lowe: American Couturier. Copyright © 2023 by Winterthur<br />

Museum, Garden & Library. Published by Rizzoli Electa.<br />

32 aphrochic

issue sixteen 33

34 aphrochic

Fashion<br />

Despite her remarkable achievement, Lowe suffered significant financial loss as a result of the<br />

flood and remained relatively unknown to the public, as her name was not mentioned as the<br />

designer for Kennedy's dress.<br />

Lowe's story is a parallel to a hidden stitch — a sewing technique that makes the thread<br />

invisible on the right side of the fabric. Similarly, Lowe's race rendered her invisible to many<br />

despite her extraordinary talent. She candidly described her experiences, stating, "I was not<br />

acknowledged because of my race. People often didn't want others to know I was behind the<br />

designs."<br />

Throughout her career, Lowe faced systemic racism that overshadowed her many accomplishments<br />

and limited her opportunities. Despite being underpaid and encountering economic<br />

inequity, she persevered, demonstrating unwavering dedication to her craft. Lowe's journey<br />

through racial discrimination and adversity is a testament to her resilience and exceptional<br />

talent. Though she passed away in 1981, her legacy remains a vital part of fashion history.<br />

Ann Lowe: American Couturier enshrines Lowe's legacy and her extraordinary achievements<br />

born out of perseverance and passion, proving that one can carve out a space, even in<br />

challenging industries. Her story is a powerful example of how racial inequity can overshadow<br />

even the most talented individuals and her journey highlights the importance of recognizing<br />

and celebrating the contributions of Black people across all fields. The book stands as a perfect<br />

testament to Lowe's tenacity and artistry, inspiring future generations of designers to pursue<br />

their dreams against all odds. AC<br />

“All the pleasure I<br />

have had, I owe to<br />

my sewing.”<br />

- Ann Lowe<br />

issue sixteen 35

Interior Design<br />

Celebrating<br />

Diaspora In<br />

Every Room<br />

Inside a Brooklyn Brownstone Designed by <strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

How do you represent the African Diaspora in a physical<br />

space? The feeling? The idea? To imbue a home with a<br />

collective sense of a global community, of people connected<br />

by the same things we are separated by — time, space and<br />

culture? That’s the question posed in one of our latest<br />

interior design projects, the design of a two-story prewar<br />

brownstone in Brooklyn.<br />

Words by Bryan Mason<br />

Photos by Chinasa Cooper<br />

36 aphrochic

Interior Design

Interior Design<br />

A story of home isn’t written overnight. It<br />

takes time, developing and growing as we move<br />

and live in one place after another, captured in<br />

the things that we gather and keep along the way.<br />

Often we’ve found that creating the feeling of<br />

home in a newly designed space is largely about<br />

maintaining the feeling it had before, albeit<br />

with a new look and aesthetic. And often this<br />

is done by incorporating those things, already<br />

possessed, that have defined home for someone<br />

in the past, either by giving them new life or<br />

showing them in a new light. For this project,<br />

we were inspired by the homeowner’s collection<br />

of art, and in particular Dictatorship, a poignant<br />

photograph by Ayana V. Jackson. A major piece<br />

in the homeowner’s collection, this work — a<br />

call to examine oppression and objectification<br />

— became the inspiration for an interior design<br />

project where forms of resistance are highlighted,<br />

Diaspora culture is celebrated, and female<br />

protective energy is venerated.<br />

In the living room, dark blue was brought<br />

in as a stunning backdrop to the Jackson piece.<br />

The deep hue carries throughout the entire<br />

first floor, color-blocking the space from the<br />

ceiling down to the baseboards. Inspired by the<br />

shades of claret red, gray, and black present in<br />

Dictatorship, a sophisticated, red tufted sofa<br />

was brought in to complement the palette. For<br />

visual contrast, a tailored gray sofa was added<br />

and placed across from it. Above the industrial<br />

coffee table, an oversized brass chandelier<br />

provides a modern sculptural touch to<br />

a room filled with the homeowner’s collection<br />

of masks and carved statues. Masks from<br />

the Chokwe people adorn the wall next to the<br />

fireplace. And on the mantle, a Massai ironwood<br />

sculpture meets a Zimbabwean soapstone bust.<br />

The bookshelf is home to Ghanaian carved art as<br />

well.<br />

The homeowner’s love of wax print fabrics<br />

and antique furniture inspired a showcase of<br />

unique furnishings in the space. Seated between<br />

the fireplace and bookshelf, a small antique<br />

European stool has been reupholstered and<br />

covered in a Dutch African wax print. The result<br />

of historical interactions including African,<br />

European, and Asian participants, the mesmerizing<br />

look and broad diversity of wax prints is a<br />

testimony to the sometimes tumultuous nature<br />

of cultural actions, and the beauty that can be<br />

the result. Part of an extensive collection by<br />

the homeowner, these eye-catching pieces are<br />

featured extensively throughout the home.<br />

The dining room makes use of the deep<br />

blue wall color as well, perfectly highlighting<br />

the clients' own furniture. We chose 10 antique<br />

chairs from the homeowner’s collection, and<br />

had them upholstered in wax prints to surround<br />

a large farmhouse table. The harmoniously<br />

dissonant mix and match of patterns, styles,<br />

and shapes represents a reflection on the nature<br />

of Diaspora — observing the group as a whole,<br />

there is nothing entirely alike between them and<br />

nothing wholly different. Instead, there is similarity<br />

even in their differences and distinction<br />

in their commonalities, yet they all attend the<br />

table equally. Across the expansive dining room<br />

table, a series of artisan chessboards has been<br />

displayed. And on the walls hangs a series of<br />

zen-inspired breathwork paintings in black ink<br />

with gold leaf, that we commissioned from New<br />

York artist Filiz Soyak.<br />

A prewar brownstone of Dutch design, the<br />

interior architecture of the home includes a long<br />

hallway that extends from the entry. A narrow<br />

passageway, there’s little room for furnishings,<br />

so we decided to go in another direction, commissioning<br />

a mural to be painted. Working in<br />

partnership with the Jenn Singer Gallery out<br />

of the UK, a collaboration with Ugandan-born<br />

artist, Moosh, was born. Research on Yoruban<br />

and Ugandan iconography was translated into<br />

female figures who act as protectors of the<br />

home — a tribute to the strength and beauty of<br />

Black women in all corners of the globe. Two of<br />

the guardians wait with raised hands covered<br />

in red boxing gloves along the left side of the<br />

hallway, while another, seated sentry guards the<br />

stairway with a raised sword. Should a visitor be<br />

permitted entry by the seated guardian, a trip up<br />

the stairs reveals the homeowner’s sanctuary.<br />

Where the first floor is a public space, the<br />

second floor is a sacred one in this home.<br />

The first floor is characterized by<br />

energetic hues, but the second floor has been<br />

designed with rest and tranquility in mind.<br />

The sitting room has been painted a light,<br />

silvery gray to highlight the original wood in<br />

this historic, prewar home. At the center of the<br />

space, a vintage coffee table surrounds a pair<br />

of white, vegan leather chairs. Beyond them,<br />

an antique armoire — home to a vintage radio<br />

and record player — offers to fill the space with<br />

relaxing music. By the window, an ornate settee<br />

adorned in a startling fuchsia wax print fabric<br />

offers a major burst of color in an otherwise<br />

quiet, retreat space. Situated above it, a classic<br />

issue sixteen 41

Interior Design

Interior Design

Interior Design<br />

photograph of Muhammad Ali adds another touch of Diaspora, echoing the themes of strength, beauty, and resistance<br />

that are common to the many experiences of the African Diaspora, and which can be seen throughout the house.<br />

Finally, in the bedroom we began with shades of lilac on the walls to create a calm, meditative feel to suffuse and<br />

anchor the space. The light purple is a perfect complement to the colors in the room, ranging from dark walnut to<br />

deep red. The bedroom is filled with unexpected pairings: a turned leg bed, a cowhide rug, a Buddhist-inspired lamp.<br />

The mix of styles reflects the homeowner’s experience and draws largely on stores of previously amassed objects. As<br />

elsewhere in the home, wax print elements are present here, draped across the bed, adding a touch of color, history,<br />

culture and depth. Meanwhile the carved Punu Mukudj, an artistic and sought-after mask originating in southern<br />

Gabon, brings home another moment of feminine energy, representing peace.<br />

The African Diaspora is multifaceted and in this home’s design it is individually accounted for, collectively recognized,<br />

celebrated and welcomed through the range of art and furnishings on display. In this space, the African<br />

Diaspora is home. AC

Interior Design

Interior Design<br />

52 aphrochic

issue sixteen 53

Interior Design

Interior Design<br />

56 aphrochic

issue sixteen 57

Culture<br />

Nigeria<br />

Remembered<br />

Inside the Nigeria Pavilion at the Venice Biennale<br />

At the end of April, the art world descended upon Venice, Italy,<br />

for the opening of the 60th annual La Biennale di Venezia. The<br />

global exhibition presents 331 artists and collectives from 80<br />

countries, presenting work around this year’s theme — Foreigners<br />

Everywhere. The phrase had been a rallying cry in the early 2000s<br />

for Italians fighting racism and xenophobia at home. And today, as<br />

our world is changing and being reshaped through global human<br />

rights efforts, genocide, war, climate change, pandemics, and<br />

migration, the Biennale Arte <strong>2024</strong> is specifically highlighting the<br />

experiences of foreigners, immigrants, expatriates, diasporans,<br />

exiles, and refugees.<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays<br />

Photos courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia, Museum of<br />

West African Art, and the Jack Shainman Gallery<br />

58 aphrochic

issue sixteen 59

Culture<br />

With several newly participating nations<br />

from the African continent, including the<br />

Republic of Benin, Ethiopia, the United<br />

Republic of Tanzania, and Senegal, Nigeria<br />

is back at the Biennale for the second time in<br />

the nation’s history. The country’s expansive<br />

pavilion includes sculpture, photography, illustration,<br />

audio, AI, and AR. It is curated by<br />

Aindrea Emelife, the curator of modern and<br />

contemporary art at the Museum of West<br />

African Art (MOWAA) in Benin City, Nigeria.<br />

Emelife has included works from several<br />

notable artists with different connections to<br />

the country, including artists who are Nigerian-born<br />

and those of Nigerian descent.<br />

As you walk through the installation,<br />

you’ll see Yinka Shonibare’s Monument to the<br />

Restitution of the Mind and Soul, 2023. The<br />

monument highlights the beauty of artistry<br />

and spiritualism present in the Kingdom of<br />

Benin, what is now southern Nigeria, prior<br />

to the arrival of European colonizers in the<br />

late 19th century. Shonibare, who was born in<br />

Britain, raised in Nigeria, returning to London<br />

in his late teens, developed a monumental clay<br />

pyramid, filled to the brim with iconographic<br />

pieces, including a mask of Idia, the first Queen<br />

Mother of the <strong>16</strong>th century Benin kingdom; the<br />

cockerel okukur, a ceremonial object utilized<br />

in religious traditions; and Oba sculptures<br />

depicting the heads of the kings of Benin.<br />

Encased behind glass, you’ll see a bust<br />

of Sir Harry Rawson, one of the military commanders<br />

of the United Kingdom’s Benin expedition<br />

of 1897, in which the British attempted<br />

to assassinate the king in a power grab, and<br />

after a failed attempt, returned with over 1,000<br />

soldiers, machine-gunning, bombarding,<br />

torching villages and towns, and indiscriminately<br />

massacring countless inhabitants of<br />

the kingdom over a three-week period. British<br />

soldiers looted the kingdom, stealing an incalculable<br />

number of artifacts, many that exist in<br />

museum collections around the world today. In<br />

the monument, Shonibare has objectified the<br />

commander, just as pieces from the Kingdom<br />

of Benin are objectified today, housed in glass<br />

in colonial museums. The monument is a<br />

physical representation of a widely discussed<br />

topic in today’s art world — the need to repatriate<br />

stolen Benin cultural artifacts to modern<br />

day Nigeria.<br />

Toyin Ojih Odotula, who was born in<br />

Nigeria and grew up in Alabama, has three<br />

captivating works entitled Congregation, 2023.<br />

The artist’s fluid charcoal and pastel works<br />

on linen are inspired by the Mbari art and<br />

spiritual practice. Mbari were sacred spaces,<br />

constructed with clay, and built over years<br />

through collective community. Works of art in<br />

themselves, the structures featured patterns<br />

painted across the walls and pillars, and were<br />

traditionally filled with figures representing<br />

Igbo beliefs and deities. While the art is<br />

little practiced in Nigeria due to post-colonial<br />

conflicts instigated by the British, Odotula’s<br />

62 aphrochic

Culture<br />

Mbari includes modern Nigerian figures as part<br />

of her sacred home. As she explained to The New<br />

York Times, “I wanted the space to exist very open<br />

and free…safe; it has room to roam; it has the right<br />

to change, to be mercurial.”<br />

Sculptor and activist Ndidi Dike’s Blackhood:<br />

A Living Archive, <strong>2024</strong>, is an installation of<br />

sculpture and photography that speaks to the<br />

Diasporic civil rights movements that have been<br />

taking place in the last four years. A large black<br />

sculpture made up of 700 police-grade batons,<br />

and an installation of photographs references<br />

the END SARS protests that took place in Nigeria<br />

in 2020. Dike, who was born in London, and went<br />

on to attend the University of Nigeria, Nsukka<br />

as young adult, is known for creating work that<br />

touches on the institutions of slavery and colonialism,<br />

and their historical and continued impact<br />

today. Dike brings viewers into the END SARS<br />

movement, where Nigerian youth took to the<br />

streets calling for the disbanding of the abusive<br />

Special Anti-Robbery Squad, and examines<br />

how it aligns with Black Lives Matter and other<br />

movements across the Diaspora that developed<br />

that same year — the largest call for civil rights<br />

that the world has ever seen.<br />

Tunji Adeniyi-Jones, Onyeka Igwe, Abraham<br />

Oghobase, Precious Okoyomon, and Fatimah<br />

Tuggar are exhibiting in the pavilion as well<br />

with works that explore the Nigeria Imaginary<br />

theme. A theme centered on the “potential<br />

of Nigeria,” Emelife reported to Wallpaper. “It<br />

almost becomes a manifesto for a new nation,<br />

a nation that could have been, but a nation that<br />

still can be. I wanted to create an exhibition that<br />

can be inspiring, not just for the world, but for<br />

the country it's about, so that it can inspire new<br />

artists…they can inspire all of us to imagine a new<br />

Nigeria and then try to put that into actuality.”<br />

The Nigeria Pavilion will be on view at the<br />

Venice Biennale until <strong>No</strong>vember 18. AC<br />

64 aphrochic

issue sixteen 65

Culture<br />

66 aphrochic

issue sixteen 67

Culture<br />

68 aphrochic

THE<br />

APHRO<br />

APHRO<br />

CHIC<br />

P O D C A S T

Food<br />

A Soul Food<br />

Homage<br />

Chef Chris Scott Shares The Roots Of His<br />

Culinary Experience in His New Cookbook<br />

For Chef Chris Scott, writing his cookbook Homage was a journey<br />

home as he tells the story of his family over seven generations<br />

via comforting dishes and vivid narratives. We learn the story of<br />

his enslaved ancestors; Scott’s great-grandfather, who migrated<br />

to Pennsylvania after the Emancipation Proclamation; his own<br />

childhood in Amish country; and his successful restaurant career<br />

in Philadelphia and New York City.<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays<br />

Photos courtesy of Chronicle Books<br />

issue sixteen 71

Food<br />

72 aphrochic

Food<br />

Growing up in Coatesville, Pennsylvania, Scott was surrounded<br />

by the cultural roots of the Pennsylvania Dutch and his African<br />

American heritage. It was the fusion of the two heritages, and wanting<br />

to share those roots with his children, that inspired the chef’s first<br />

cookbook. “I wrote this book for several reasons — the biggest one is<br />

that I see it as a love letter passed down from my mother and grandmother<br />

to my four children. Both women passed away before my kids<br />

were born. It's a way for my children to know where they came from,<br />

and for me to share some insight into these strong Black women,”<br />

remarks Scott.<br />

A touching tribute, Homage presents an exciting blend of<br />

culinary traditions that result in unique dishes like Crispy “City<br />

Mouse” Scrapple with an Okra Chow-Chow relish, Lemonade Buttermilk<br />

Fried Chicken, and Pickled Collard “Ribs” and Beans. The book<br />

also highlights something we don’t see discussed often, the regional<br />

nature of Black Soul Food. “I wrote it to once and for all demonstrate<br />

how Soul Food can be regional. Black folks are everywhere,<br />

and depending on where you are in this country — coastal regions,<br />

mountains, the great plains — and who you share your space with<br />

— the Dutch, the German, the Amish, the Indigenous — there will<br />

certainly be influence,” remarks Scott.<br />

Narrative-driven, and featuring 100 dishes, Homage is a<br />

cookbook you’ll want to read and revisit for the rich story-telling;<br />

and to be inspired by these Amish Soul Food dishes that deliver new<br />

stories about the American experience. Chef Scott shares with us<br />

his nana’s Peach Cobbler recipe. The handwritten recipe, inspired<br />

by Amish desserts and his grandmother’s love of shugga’s, the name<br />

of the chapter, is a coveted family heirloom, like many of the recipes<br />

presented in this book.<br />

GET THE BOOK<br />

Reprinted from Homage: Recipes + Stories from an Amish Soul Food Kitchen<br />

by Chris Scott. Copyright © 2022 Chris Scott. Photos © Brittany Conerly.<br />

Published by Chronicle Books

Peach Cobbler<br />

"In my opinion, this is the queen of Southern desserts. Food writer and historian Sicele Taylor once said, 'If you don't have peach cobbler on<br />

your menu, then you ain’t no southern restaurant.' I agree with that sentiment completely. <strong>No</strong>t only does it use a fruit that's grown in the South<br />

since European settlers brought pits to plant, centuries ago, but it also seems to show up during the most joyful moments for most Southern<br />

children and it played a role in their happiest food memories. It certainly did for me." — Chef Chris Scott<br />

Serves 8<br />

8 cups [1.5 kg] sliced fresh peaches<br />

2 cups [400 g] sugar<br />

2 Tbsp fresh lemon juice<br />

2 Tbsp cornstarch<br />

1 Tbsp vanilla extract<br />

1 tsp ground cinnamon<br />

1/4 tsp ground nutmeg<br />

1 cup [240 ml] milk<br />

1/2 cup [113 g] butter<br />

1 1/2 cups [210 g] all-purpose flour<br />

1 Tbsp baking powder<br />

1 tsp kosher salt<br />

Vanilla ice cream, for serving<br />

Preheat the oven to 350°F [180°C). Butter a 3 qt (2.8 L] baking<br />

dish.<br />

In a mixing bowl, toss together the sliced peaches, 1 cup<br />

[200 g] of the sugar, the lemon juice, cornstarch, vanilla,<br />

cinnamon, and nutmeg. Toss until the peaches are thoroughlyand<br />

evenly coated. Set aside.<br />

In a saucepan over medium heat, heat the milk and butter,<br />

stirring, until the butter is melted.<br />

Sift the flour, remaining 1 cup [200 g] of sugar, the baking<br />

powder, and salt into a mixing bowl. While whisking, slowly<br />

stream in the milk and butter mixture, and whisk until<br />

smooth.<br />

Pour the peaches and their juice into the prepared dish.<br />

Pour the batter over the peaches.<br />

Bake for 1 hour, or until the crust is golden brown. Serve<br />

warm, with a scoop of vanilla ice cream.<br />

issue sixteen 75

Entertaining<br />

Glow Up<br />

Your Tabletop<br />

Floral Designers Kathleen Hyppolite and Emily<br />

Howard Share Bright and Bold Centerpieces<br />

Perfect for Your Next Soirée<br />

When setting the table for a party, every element counts — the<br />

textiles, the china, the flatware and, most importantly, lots and<br />

lots of beautiful flowers. Natural blooms give life to a tabletop<br />

display, adding color, shape and texture. With their distinctive,<br />

contemporary and colorful styles, Kathleen Hyppolite and Emily<br />

Howard show us how to create stunning floral displays that will<br />

help every element on your table shine.<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays<br />

Photos by Patrick Cline<br />

Styling by Angela Belt<br />

76 aphrochic

Floral designers Kathleen Hyppolite<br />

and Emily Howard

Entertaining<br />

“My style is textural and personal<br />

with notes of romance and whimsy,” says<br />

Hyppolite. The owner of Kat Flower in<br />

Brooklyn, Hyppolite’s centerpiece of French<br />

anemones, garden roses, and sculptural<br />

greenery made up of rainbow eucalyptus,<br />

is filled with romantic touches. The soft<br />

pink hue in a garden-to-table composition<br />

mixed with vibrant greenery takes on a fresh<br />

and modern approach. “I love exploring<br />

color and all of its natural iterations,” says<br />

Hyppolite. A mix of mid-century dinnerware<br />

in a classic black-and-white color palette<br />

completes the look, with gold flatware and<br />

graphic Korean bowls bringing energy to<br />

this dinner party setting.<br />

“The work I do with flowers tends to be<br />

gestural but not too wild, complex but not<br />

busy, pulled together but a little irreverent<br />

and feminine,” remarks Howard. Expertly<br />

drawing together a range of disparate hues,<br />

Howard showcases tree peonies, ranunculus,<br />

and carnations in contrasting shades<br />

of yellow and purple, setting the mood for a<br />

dramatic tabletop that has some throwback<br />

energy. Antique yellow and bright purple<br />

flowers take on a modern feel within a<br />

mixture of vintage black and metallic dinnerware,<br />

while the traditional blooms that<br />

make up this arrangement are given a fresh<br />

new look with the unexpected contrast of<br />

colors that defines this display. “My arrangements<br />

imbue their settings with a sophisticated,<br />

grown-up whimsy.”<br />

Inspired by the tropics, shades of<br />

pink, coral, and orange meet in a vivid arrangement<br />

by Hyppolite made up of rose<br />

lilies, poppies, daffodils, and kumquats. The<br />

bold colors look perfect among the natural<br />

elements spread around the table, from<br />

glasses in wicker sleeves to handwoven<br />

Mexican textiles, coiled grass baskets and<br />

a single leaf set in porcelain rice bowls. The<br />

relaxed arrangement feels like an organic<br />

and artisan celebration of natural beauty. “I<br />

try to use the same approach with flowers<br />

as I would food,” remarks Hyppolite. “Using<br />

fresh, seasonal elements to create a thoughtful<br />

and natural design that captures each<br />

bloom’s charm, grace, uniqueness, and<br />

beauty.”<br />

A bold and textured centerpiece by<br />

Howard shows off a mix of conventional<br />

blooms in bold colors that set off this<br />

tabletop display. Featuring red carnations,<br />

cosmos, seeded eucalyptus, and feathers,<br />

the centerpiece has layers of unique texture.<br />

And it stuns, paired with traditional wood<br />

elements and ceramic pieces, including<br />

the Japanese blue-and-white Willow Ware.<br />

Completing the look is the unexpected<br />

addition of gold metallics. Together, the<br />

various blues and golds on the table create<br />

a layered backdrop of color that propels the<br />

vibrant floral array to center stage.<br />

<strong>No</strong> matter what the occasion, Emily and<br />

Kathleen show that your tabletop can be a<br />

spectacular showcase of fresh blooms among<br />

beautiful pieces that are sure to make your<br />

next event a visually stunning affair. AC<br />

Previous page: Hyppolite creates<br />

a bright and bold tropical floral<br />

arrangement.<br />

Right: Howard uses contrasting<br />

shades of yellow and purple to create<br />

this whimsical arrangement<br />

80 aphrochic

Entertaining<br />

Hyppolite creates a romantic centerpiece<br />

with French anemones, garden<br />

roses, and sculptural greenery.<br />

82 aphrochic

issue sixteen 83

Entertaining<br />

84 aphrochic

Howard's textured centerpiece features red carnations, cosmos, seeded eucalyptus, and feathers.<br />

issue sixteen 85

City Stories<br />

Two Sides of<br />

Black History<br />

Exploring New York's Ulster Country<br />

Ulster County, N.Y., is a yearlong destination. Situated comfortably as<br />

either the topmost part of mid-state New York or among the bottommost<br />

counties of upstate (depending on how one chooses to view the state) it is<br />

known for its scenic vistas, quiet towns, sophisticated cuisine, and quaint<br />

shops. Every year the break of spring brings visitors looking to witness<br />

nature’s return to life. In summer, its mountains draw hikers, climbers,<br />

and lovers of waterfalls to wander its verdant green paths. Another group<br />

arrives in fall to watch the turn of the leaves and join in on the fun of the<br />

apple harvest season at any of a number of local orchards. And in winter,<br />

the holidays fill the region with those looking to escape the city for the<br />

season, in hopes of an idyllic and snow-covered end to the year.<br />

Words by Bryan Mason<br />

Photos by Bryan Mason and courtesy of New York State Parks, Recreation<br />

and Historic Preservation, Ulster County, and Town of Esopus<br />

Shawangunk Mountain Range<br />

86 aphrochic

Black Suffragists in Ulster Country

City Stories<br />

Of the many things we tend to think of when considering<br />

upstate New York, Black history is not usually one of<br />

them. And because of that, we run the risk of missing out.<br />

Because, not only does the history of Black presence in the<br />

region stretch back as far as anywhere else in the country,<br />

the story of Ulster County in particular encompasses<br />

both sides of African American history — the joy and the<br />

struggle — the two tales similar in nothing so much as the<br />

extent to which each goes untold.<br />

The Story of Struggle<br />

Shortly after the beginning of slavery in the American<br />

south, the practice came to New York. In <strong>16</strong>26, seven years<br />

after the <strong>16</strong>19 arrival of enslaved people in Jamestown,<br />

Va., 11 men arrived in what was then the Dutch settlement<br />

of New Amsterdam (now Manhattan). In name, these<br />

men were listed as employees of the Dutch West India<br />

Company — indentured servants — but as far as the law<br />

and anyone in the area was concerned, they were property.<br />

In <strong>16</strong>44, after 18 years of servitude, nearly double the time<br />

allotted for indenture, and which likely included military<br />

service, these 11 men would sue to improve their stature,<br />

resulting in their being legally declared “half-free.” They<br />

would also be among those granted land by the Dutch West<br />

India Company, becoming the first non-native settlers<br />

of what is now the Lower East Side, SoHo, Tribeca, and<br />

Greenwich Village. This dubious distinction was far from<br />

a gift of altruism. The half-free Black settlement was envisioned<br />

by the Dutch as a buffer between their own settlement<br />

and the Lenape, with whom they were in constant<br />

conflict.<br />

The earliest Dutch settlements in and around the<br />

Shawangunk Mountains, later part of Ulster County, were<br />

founded in the <strong>16</strong>90s. By the time of the first federal census<br />

in 1790, slavery had spread throughout the state, which<br />

recorded a total enslaved population of 21,193 people, surpassing<br />

the combined totals of all six New England states.<br />

And within New York, one of the state’s largest enslaved<br />

populations — 2,906 people — was found in Ulster County.<br />

Though New York had belonged to the British since<br />

<strong>16</strong>64, the rural plantations that held the majority of those<br />

enslaved in Ulster Country remained largely Dutch. In<br />

1799, nine years after the first census, New York passed a<br />

law for gradual manumission of all those held as slaves<br />

within the state. And though the law did not free a single<br />

living enslaved person, resistance from elected officials in<br />

what were termed the “Dutch counties” was so strenuous<br />

that it earned Ulster the historical moniker, “Where slavery<br />

died hard.”<br />

In 1797, Isabella Baumfree — known to the world as<br />

Sojourner Truth — was born into slavery in Swartekill, N.Y.,<br />

part of what is today the hamlet of Rifton in Ulster County.<br />

Her early years were marked by every trauma a life of enslavement<br />

could provide, from the sale of her siblings and<br />

later herself away from her parents and family, to the loss<br />

of her own children to the same practice. In 1827, when she<br />

fled that life and its cruelties, she traversed Ulster County,<br />

leaving all but one of her children behind, traveling until<br />

she reached the Rowe and Van Wagner households, which<br />

aided her until she was legally manumitted.<br />

Sojourner Truth would emerge as one of the foremost<br />

orators and activists of American history, advocating for<br />

90 aphrochic

Sojourner Truth State Park<br />

Sojourner Truth Statue<br />

issue sixteen 91

City Stories<br />

emancipation and suffrage on virtually every American stage. In 1828, Truth<br />

sued at the Ulster County courthouse to overturn the illegal sale of her fiveyear-old<br />

son, transacted shortly before her escape. In winning the case, she not<br />

only saved her son, but entered history as the first Black woman to win a lawsuit<br />

in the United States.<br />

The Story of Joy<br />

As is true for every aspect of American history as whole, the story of African<br />

Americans in Ulster Country progresses beyond the days of enslavement and<br />

degradation. And though life after emancipation in Ulster, as elsewhere, was<br />

marked by struggle and intolerance, the region’s Black community continued to<br />

grow and thrive. In fact, the list of notable Black Americans to hail from or reside<br />

in the area reads like a who’s who across a variety of industries.<br />

Undoubtedly one of the area’s most colorful and interesting residents was<br />

Clayton Bates, better known as “Peg Leg.” Despite losing a leg to a cotton gin<br />

accident at the age of 12, Bates became sufficiently adept at tap dancing to find<br />

himself in demand on stages across the world, performing on the Ed Sullivan<br />

Show more than 20 times. He performed twice for British royalty in the 1930s<br />

before touring England with Louis Armstrong in the 1950s. He continued performing,<br />

appearing from Paris to Broadway, until his retirement in 1989. In 1951,<br />

Bates and his wife Alice converted a 65-acre turkey farm into the legendary Peg<br />

Leg Bates Country Club, a vacation resort catering to Black patrons — which it<br />

drew from as far away as Baltimore — who came to enjoy the resort’s swimming<br />

pool, rollerskating rink, and endless buffets.<br />

Others who have called the area home over the years have included boxer<br />

"Peg Leg" Bates Country Club brochure<br />

92 aphrochic

"Peg Leg" Bates

City Stories<br />

Floyd Patterson, legendary jazz musician Sonny Rollins,<br />

bassist Gail Ann Dorsey, and musician, composer, and<br />

historian Don Byron along with many other renowned<br />

musical, literary, and artistic talents. Ulster is also the<br />

hometown of Kirkland Leroy Irvis, the 79th Speaker of<br />

the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, and the first<br />

African American to hold that post in any state legislature<br />

since John Roy Lynch held the position in Mississippi during<br />

Reconstruction.<br />

Exploring Black History in Ulster County Today<br />

While comparatively few of Ulster’s annual tourists<br />

likely come in search of Black history, it’s certainly there<br />

to be had for all who want it. In fact, there are numerous<br />

opportunities to visit and learn about the area’s past and<br />

to enjoy the culture of Ulster’s Black community today.<br />

The Mount Gulian Historic Site in Beacon, N.Y., was once<br />

home to the Verplanck family, a prominent and wealthy<br />

clan, once slaveholders and later abolitionists, with<br />

a room at the Met Museum named in their honor and<br />

dedicated to preserving their household effects. James F.<br />

Brown, a formerly enslaved man, worked and lived on the<br />

Verplanck property for 40 years beginning in 1827, the year<br />

New York’s gradual abolition of slavery reached its conclusion.<br />

Brown left extensive journals offering a detailed<br />

look at daily life for an African American in 19th century<br />

Ulster County. Another former slaveholding residence,<br />

the Bevier-Elting House, is more closely associated with<br />

the darker aspects of the time, including a prison-like<br />

cellar used to prevent those enslaved on the property<br />

from escaping.<br />

While slavery has a long history in the region, so too<br />

does resistance, and several sites, markers, and tours exist<br />

to satisfy those who would follow in the footsteps of those<br />