Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

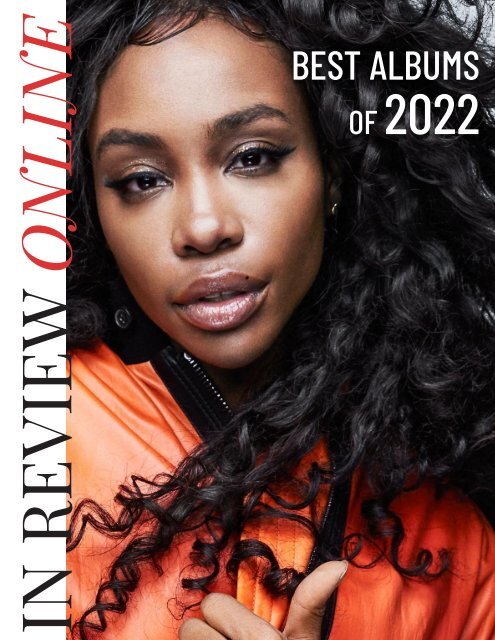

IN REVIEW ONLINE<br />

BEST ALBUMS<br />

OF <strong>2022</strong>

TOP 25 ALBUMS OF <strong>2022</strong><br />

It’s fitting that <strong>2022</strong> — as perhaps the first year that has felt in any way divorced from the Covid era we’ve all been slogging<br />

through, one in which normalcy has reclaimed some purchase in the micro <strong>of</strong> our day-to-day and macro <strong>of</strong> our cultural<br />

institutions — would be the year <strong>of</strong> the return. Queen Bey was back, in dialogue with the Queen <strong>of</strong> Disco herself, Donna Summer.<br />

Kendrick dropped yet another masterful album <strong>of</strong> shape-shifting aesthetics, one that powerfully reflects the introspection that<br />

captured so many minds over the past three years and channeled it into yet another sonic singularity. Drake sowed division<br />

amongst his fanbase with a push into deep house, but still reclaimed his crown as the people’s narcissist <strong>of</strong> choice after king cringe<br />

Elon became somehow cringier and Ye outed himself as a potentially lifelong Nazi apologist. Breakout favorite Black Country, New<br />

Road delivered their sophomore album, only to immediately split with lead singer Isaac Wood; Big Thief resumed duties after a few<br />

solo records made their mark last year; and mid-aughts Millennial favorites like Yeah Yeah Yeahs and Death Cab for Cutie proved<br />

they’re still legitimate players in the world <strong>of</strong> rock. Sure, not all returns were great — Taylor Swift delivered a mixed product with<br />

Midnights (though still an improvement on her irksome and remarkably overrated duo <strong>of</strong> folklore and evermore; note: this is not an<br />

opinion shared by all or even most <strong>of</strong> InRO’s writers, but I’m the one writing this, so everyone else can touch grass); Machine Gun Kelly<br />

obliterated any remaining goodwill he had from the pop pleasures <strong>of</strong> Tickets to My Downfall with the the whiniest album <strong>of</strong> the year;<br />

and The Lumineers returned with… just kidding, we didn’t listen.<br />

But rather than getting lost in a whorl <strong>of</strong> gloom, we at InRO choose positivity at this turnstile <strong>of</strong> <strong>2022</strong> and 2023, readying ourselves<br />

for more welcome returns as we all collectively climb out <strong>of</strong> the basement <strong>of</strong> politicized pandemics and back into the light.<br />

Over the past year, these 25 albums (plus some honorable mentions) have kept our glass half full. For that, we are thankful.<br />

1

#25 — DIFFERENT MAN<br />

Kane Brown<br />

In its very best moments, Different Man recalls nothing less than<br />

Brad Paisley's watershed American Saturday Night -- for how it<br />

traffics pop through a trad country landscape (lots <strong>of</strong> fiddle) and<br />

for how songs like "Riot" and "Bury Me in Georgia" hint at<br />

simmering contemporary sociopolitical tensions this genre<br />

usually won’t touch. But Kane Brown is, in a word, "different": He's<br />

not a genre innovator, not a conscious commentator; he's an<br />

almost inevitable insurgent, very much embedded in modern<br />

country, a practitioner <strong>of</strong> its forms and invested in its formulas,<br />

but possesses a level <strong>of</strong> emotional intelligence that allows him to<br />

elevate himself above country’s worst tendencies, trading<br />

arrogant machismo for a masculinity founded on gratitude and<br />

grace (principles that his wife reciprocates on their shimmering<br />

duet "Thank God," and that he even somehow gets Blake Shelton<br />

to credibly adopt on the album's title track). For this particular<br />

Brown album rollout, the immediate standout was "Grand," which<br />

isn't country at all, but rather a crystalline club-pop song with a<br />

hairline fracture: "The voices in my head used to make me wanna<br />

break down / Had me hella weighed down." As part <strong>of</strong> this<br />

primarily country program, the song is more than just a “pop<br />

experiment”; it’s an act <strong>of</strong> willful liberation from the stigmatism<br />

that a biracial country chart-topper faces when he dares<br />

embrace the full spectrum <strong>of</strong> his musical savvy.<br />

Succeeding on strength and intuitiveness <strong>of</strong> craft across<br />

different sub-genres is the foundational tenet <strong>of</strong> Different Man,<br />

whether it's the funky, R&B-inflected "See You Like I Do," the<br />

Brooks and Dunn-indebted (and featuring) "Like I Love Country<br />

Music," or the way the tipsy bossa nova <strong>of</strong> "Drunk or Dreamin'" or<br />

the interplay <strong>of</strong> EDM, hard rock, and a looped fiddle hook on "Go<br />

Around" provide musical articulation <strong>of</strong> their respective lyrics.<br />

Brown is capable <strong>of</strong> putting together a heartbreaker <strong>of</strong> a lovelorn<br />

ballad with some self-dismantling honesty worthy <strong>of</strong> George<br />

Jones ("I've never been a somber soul / But part <strong>of</strong> me ain't here no<br />

more"), and on this album's best-written song, "Pop's Last Name,"<br />

he can advocate with moving authority for families broken down<br />

by the pitfalls <strong>of</strong> a nation that the thinking country music fan<br />

could forgive him for loving just a little bit less. But as the<br />

bookending "Bury Me in Georgia" and "Dear Georgia" lay bare, he's<br />

full <strong>of</strong> too much gratitude (a worthy and underused word) for all<br />

that he's achieved and all that he's earned to cede any <strong>of</strong> his<br />

energies to bitterness. And that, too, is one <strong>of</strong> the very good and<br />

different things about him. — SAM C. MAC<br />

2

#24 — STARS AT NOON (OST)<br />

Tindersticks<br />

Despite being their ninth collaboration (either as a full band or<br />

individual members) with legendary French director Claire Denis,<br />

Tindersticks refuse lassitude, and seem determined to craft a<br />

distinct soundscape for each film. Whether it’s the lamenting and<br />

haunting baroqueness <strong>of</strong> Trouble Every Day, or the violent and<br />

oppressive synths <strong>of</strong> the score to the inexplicably dark Les<br />

Saluads, Tindersticks have consistently managed to create a<br />

sound that exquisitely matches the distinctive mood and style <strong>of</strong><br />

each successive film. Their latest work, the <strong>of</strong>ficial soundtrack<br />

for Denis’ new film Stars at Noon, is no different, once again<br />

lending the impression <strong>of</strong> reinvention and <strong>of</strong>ten sounding like an<br />

almost entirely different band to the one responsible for the<br />

aforementioned film scores.<br />

The Stars at Noon OST feels split into two styles: the first being a<br />

languid style <strong>of</strong> lounge jazz that lands with remarkable calm,<br />

while the second boasts a far more rhythmic flow that testifies to<br />

the film’s scattered bursts <strong>of</strong> urgency. Centered in the middle is<br />

the title track, the only sung instance <strong>of</strong> music on the record,<br />

which gives the impression <strong>of</strong> a climax that the previous songs<br />

may have been building up to. It’s an aching and melancholic<br />

piece, in function playing over a scene where the film’s two<br />

central lovers dance in a barren and dimly lit bar. It’s a sensuous<br />

experience, vocalist Stuart Staples’ voice and lyrics bearing a<br />

deep intimacy which invokes a flurry <strong>of</strong> emotions, even when<br />

detached from the film’s images. More than that, Tindersticks<br />

had this song — among others — ready for Claire to shoot the<br />

film to; the characters therein are directly dancing to the already<br />

existing music. Of course, the fact that the sonics and visuals<br />

line up so perfectly comes down to pure luck in some ways, but<br />

it’s also the thrilling result <strong>of</strong> a deep-rooted and artistic<br />

collaboration where placing trust in another has become second<br />

nature.<br />

Like the film (also featured in InRO’s <strong>Best</strong> Of declarations), it’s<br />

perhaps too easy to brush this OST album aside at first blush as<br />

an inessential minor work. Yes, it’s mostly comprised <strong>of</strong> short,<br />

instrumental jazz cuts that seem to drift by without much lasting<br />

weight. But the album’s power comes from how intoxicating<br />

these songs become, particularly in context with the film’s<br />

considerable heft, turning into something that is incredibly easy<br />

to return to over and over again. That’s especially true <strong>of</strong> the<br />

record’s title track, which is easily one <strong>of</strong> the finest Tindersticks<br />

songs <strong>of</strong> the past decade; it’s as raw and pr<strong>of</strong>ound as anything<br />

that has appeared on one <strong>of</strong> the group’s studio albums, and the<br />

final complete project is enhanced by the text — visual and<br />

narrative — that invigorates the final product.— OLIVER PARKER<br />

3

#23 — I WALKED WITH YOU A WAYS<br />

Plains<br />

The notion <strong>of</strong> “close harmony” is integral to many forms <strong>of</strong><br />

bluegrass and roots music, and it's an idea that seeps into<br />

every aspect <strong>of</strong> Plains’ I Walked With You A Ways. It isn't simply<br />

a matter <strong>of</strong> vocal harmony — though the intricacies <strong>of</strong> the<br />

vocal arrangements on standout tracks “Problem With It” and<br />

“Hurricane” are simply extraordinary — but <strong>of</strong> how narrative and<br />

songwriting voices intertwine. While Plains isn't billed as a proper<br />

supergroup or side project, such as the Allison Krauss & Robert<br />

Plant collaborations, it's noteworthy that Waxahatchee and Jess<br />

Williamson have approached this project as distinct from their<br />

own solo careers. Ultimately, that sense <strong>of</strong> harmony makes I<br />

Walked With You a Ways such a compelling listen that, in many<br />

ways, surpasses the very, very good work these two have done on<br />

their own.<br />

Williamson’s writing is more direct than that <strong>of</strong> Waxahatchee,<br />

who <strong>of</strong>ten deploys an ironic or narrative remove that insulates<br />

her narrators. Here, there is nowhere to hide on “Abilene” (“I<br />

remember the air when I drove out <strong>of</strong> town / Crying on the highway<br />

with my windows down”) or “Last 2 On Earth” (“Can’t tell nobody<br />

nothing, it’s a bright spark to ignite… You can take that sin to<br />

battle, but you can’t make it fight”), because the narrators are so<br />

blunt in their assessments <strong>of</strong> the failures they’ve either<br />

encountered or perpetuated. In contrast, Waxahatchee’s<br />

songwriting boasts a greater depth <strong>of</strong> detail than Williamson’s,<br />

and it’s those details — “a pink carnation, a hand hastily played” on<br />

“Problem With It,” or “a cigarette in a potted plant” on “No Record<br />

<strong>of</strong> Wrongs” — that make the minor and major traumas <strong>of</strong><br />

these stories stick. For both Williamson and Waxahatchee, then,<br />

their individual strengths and weaknesses interlock seamlessly<br />

like the pieces <strong>of</strong> a jigsaw puzzle. They complement each other<br />

in the best possible ways, and the album avoids the trap <strong>of</strong><br />

drawing too much attention to who contributed what because it<br />

all plays like an organic whole.<br />

I Walked With You A Ways is all the richer, then, for how an album<br />

borne <strong>of</strong> collaboration and partnership emerges as a chronicle <strong>of</strong><br />

doomed relationship upon doomed relationship. The cheery<br />

arrangement <strong>of</strong> opener “Summer Sun” belies the narrator’s<br />

intentions to leave her partner (“Honey, we’re up against<br />

something / Our love alone can’t fix”), while “Problem With It” is a<br />

far more direct kiss-<strong>of</strong>f (“If you can’t do better than that, babe / I<br />

got a problem with it,” is the kind <strong>of</strong> line that leaves a welt). The<br />

women given voice by Plains have all come to the realization that<br />

their relationships were never intended to be more than<br />

ephemeral comforts or distractions from deeper hurts and that,<br />

having walked alongside someone for a while, it’s time for them<br />

to move on to something more fulfilling. — JONATHAN KEEFE<br />

#22 — GOD’S COUNTRY<br />

Chat Pile<br />

On full-length debut God's Country, Oklahoma City sludge metal<br />

combo Chat Pile conjures nothing less than the political, social,<br />

and economic demons <strong>of</strong> life in America. "Wicked Puppet Dance"<br />

takes on drug addiction in the age <strong>of</strong> the opioid epidemic, while<br />

"Anywhere" delves into the relentless national nightmare <strong>of</strong> mass<br />

shootings. The quartet's songs are hellish vignettes <strong>of</strong> grief,<br />

despair, and injustice, given release through apocalyptic blasts<br />

<strong>of</strong> noise-laden metal fury. The tone <strong>of</strong> God's Country zigzags<br />

between grim, heightened realism and bleakly funny hysterics,<br />

like when a drug-fueled psychotic episode is interspersed with<br />

visions <strong>of</strong> a McDonald's mascot on punishing album closer<br />

"grimace_smoking_weed.jpeg." The album's reverb-y drums and<br />

comically distorted walls <strong>of</strong> guitar are ablaze with a fiery rage<br />

that seems at risk <strong>of</strong> veering into depressive detachment — not<br />

exactly an unfamiliar trajectory for people living life in a<br />

post-9/11, post-Trump, post-pandemic America. Consequently,<br />

4

lead singer Raygun Busch has no time for pretty metaphor or<br />

smart-ass symbolism: "Why do people have to live outside? / In the<br />

brutal heat or when it's below freezing / there are people that are<br />

made to live outside," he ominously deadpans on the<br />

anti-homeless screed "Why," repeating the titular adverb with<br />

increasingly unhinged desperation as the song goes on.<br />

day-to-day violence <strong>of</strong> the meat industry and the wider, and<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten unseen, institutionalized violence that has marked<br />

American life since its inception ("There's more screaming than<br />

you'd think"). Aside from the vicious slabs <strong>of</strong> sonic aggression, the<br />

band also trades in some quieter, more abstract atmosphere,<br />

like on the eerie "I Don't Care If I Burn," which echoes Shellac's<br />

#22 — GOD’S COUNTRY<br />

Chat Pile<br />

The band also confronts the sordid history <strong>of</strong> their hometown.<br />

"Open the safe in the back before more people die," sings Busch on<br />

"The Mask," chronicling a 1974 mass murder committed by Roger<br />

Dale Stafford with disturbing fidelity. Sung from the killer's POV,<br />

Busch likens the victims to animals, screaming for them to be<br />

lined up like lambs to the slaughter. Speaking <strong>of</strong>, the horrors <strong>of</strong><br />

slaughterhouses themselves are given an especially haunting<br />

treatment on the bluntly titled "Slaughterhouse." Recalling the<br />

twisted, bloody Americana <strong>of</strong> The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, the<br />

song not only gives voice to the animals who can't speak for<br />

themselves, but also draws parallels between the horrific<br />

infamous 2000 post-hardcore ballad "Prayer to God." Chat Pile<br />

concocts from noise rock, sludge, and industrial metal a brutal,<br />

crushing genre amalgam that, like the music that inspired it,<br />

manages to be both repulsive and alluring, the heinousness <strong>of</strong><br />

the subject matter only <strong>of</strong>fset by the group's own disgust at the<br />

stories they tell. "At first your hand was in mine / There, smiling<br />

and walking / Then the world split open / I think there was brain on<br />

my shoes," goes the first verse <strong>of</strong> "Anywhere" — the hope for a<br />

better world hasn't been extinguished yet, but if we’re to take the<br />

word <strong>of</strong> Chat Pile, it seems to drift further out <strong>of</strong> reach with each<br />

passing moment. — FRED BARRETT<br />

5

#21 — WET LEG<br />

Wet Leg<br />

Each <strong>of</strong> the last few years has had an album that is threatened to<br />

be swallowed whole by the discourse over how that album was<br />

written about in the popular press. In 2021, that was the fate <strong>of</strong><br />

Olivia Rodrigo’s SOUR, and in <strong>2022</strong>, it’s the self-titled debut from<br />

Wet Leg, who had the unmitigated gall to record the album in its<br />

entirety before they’d ever played a single live gig, much to the<br />

consternation <strong>of</strong> every remaining rockist who insisted that the<br />

duo was nothing more than a studio creation. To which I say:<br />

Thank God for the witchcraft <strong>of</strong> the modern recording studio and<br />

the Gen Z rejection <strong>of</strong> all <strong>of</strong> the “right” ways to go about creating<br />

music.<br />

What’s remarkable about Wet Leg is that it’s the work <strong>of</strong> an act<br />

who had very clearly put considerable thought and effort into<br />

their artistic identity right from the jump, rather than growing<br />

into that sense <strong>of</strong> self over the course <strong>of</strong> several albums or long<br />

stints on the road. Culling the best parts <strong>of</strong> the indie scenes <strong>of</strong><br />

the ‘90s and aughts for their sonic palette, Rhian Teasdale and<br />

“What’s remarkable about Wet<br />

Leg is that it’s the work <strong>of</strong> an<br />

act who had clearly put<br />

considerable thought and<br />

effort into their artistic<br />

identity.<br />

Hester Chambers demonstrate the kind <strong>of</strong> fluency with genre<br />

that allows them to flaunt convention. There are overt nods to<br />

David Bowie — “I Don’t Wanna Go Out” notably pulls the guitar riff<br />

from Bowie’s “The Man Who Sold The World” to brilliant effect —<br />

and more subtle homages to acts like Dig Me Out-era<br />

Sleater-Kinney (“Chaise Longue”) and The Bottle Rockets and<br />

Rock-A-Teens (“Loving You”).<br />

The shifts in tone and aesthetic are purposeful and playful, and<br />

they’re always fully in service to what works for a particular<br />

song. It’s that playfulness that seemed to make Wet Leg so<br />

confounding to the Boomer set; as with Rodrigo’s extraordinary<br />

debut album, they just couldn’t reconcile their rigid constructs<br />

with music that was so clearly not for them. And the album is,<br />

above all else, fun. The non-sequiturs and Mean Girls quotes <strong>of</strong><br />

“Chaise Longue,” the well-rehearsed scream <strong>of</strong> “Ur Mom,” and the<br />

ribald put-downs <strong>of</strong> “Wet Dream” are all delivered with such a<br />

wry, arch tone — mostly by Teasdale — that it’s easy to<br />

misinterpret the intention as Wet Leg not taking their music<br />

seriously. But what actually makes Wet Leg so indelible is how the<br />

duo clearly recognizes that their irreverence is very serious<br />

business, indeed. — JONATHAN KEEFE<br />

#20 — BAD MODE<br />

Hikaru Utada<br />

Life has done a lot <strong>of</strong> pausing in the last couple years. Most <strong>of</strong><br />

those pauses have been bleak, but Hikaru Utada’s Bad Mode is a<br />

record that finds beauty and opportunity in quietness. Across the<br />

LP’s tracks, Utada reflects on a search for purpose and the<br />

delicacy <strong>of</strong> relationships over gossamer-light electronic<br />

production. On the title track, they vow to stick around for a<br />

partner even in their low moments, mixing <strong>of</strong>fers to indulge in<br />

simple comforts like ordering delivery with moving emotional<br />

declarations (“Even when it’s hard to believe that better days are<br />

coming / I’m here for you”). The music matches these shifts<br />

between worry and everyday intimacy on “Bad Mode”: the gentle<br />

funkiness <strong>of</strong> the first two choruses gives way to a watery, spacey<br />

interlude, then returns to the groove with the addition <strong>of</strong> playful<br />

trumpets. “Hope I don’t fuck it up again,” they shrug in the closing<br />

lines; not pessimistic, just used to uncertainty.<br />

The transition in “Bad Mode” is prompted by the lyric, “How many<br />

times did I question myself? / Is it this scary for everyone else<br />

too?” Single “Pink Blood,” then, considers similar ideas <strong>of</strong><br />

personal growth and learning to trust yourself, as Utada<br />

concludes, “I should stop working hard at something that doesn’t<br />

serve me / I don’t need to show it to anyone for something<br />

beautiful to be beautiful.” “Kimini Muchuu” and the bouncy “Find<br />

Love” also tackle insecurity through this lens <strong>of</strong> romantic<br />

6

entanglement, and the music remains consistently beautiful,<br />

tender, and restrained throughout. It will make sense to longtime<br />

fans, as Utada is the sole songwriter for most <strong>of</strong> the project, with<br />

co-production coming courtesy <strong>of</strong> Nariaki Obukuro, A.G. Cook,<br />

and Floating Points (who is responsible for the record’s longest,<br />

most hypnotic songs). Skrillex also shows up credited on “Face<br />

My Fears,” though the Kingdom Hearts III theme song is<br />

admittedly done a disservice in this context: its future bass<br />

chorus feels out <strong>of</strong> place amid so much twinkly electropop, but<br />

it’s worth noting only to state that the A.G. Cook remix is an<br />

excellent substitute.<br />

The album’s boldest musical statement is closer “Somewhere<br />

Near Marseilles,” which remains remarkably down-to-earth<br />

despite being an almost 12-minute epic. Utada plans a casual<br />

hotel rendezvous — all they want is “a spot with easy access,” “a<br />

room with a view,” and each other — while the music unspools<br />

into a shifting arrangement equally as suited for dancing as it is<br />

for laying around the house on a lazy Sunday morning. It’s a<br />

thoughtful conclusion to a set <strong>of</strong> songs that balance patience<br />

with conviction, as they explore when to work toward love and<br />

self-worth, when to pull back from something beyond one’s<br />

control, and when to commit it all in defense <strong>of</strong> the things that<br />

give life meaning. On “One Last Kiss,” Utada sings, “I love you<br />

more than you’ll ever know”—but even just trying to say it means<br />

everything.— KAYLA BEARDSLEE<br />

#19 — ASPHALT MEADOWS<br />

Death Cab for Cutie<br />

A venerable indie rock institution, Death Cab for Cutie is many<br />

things to many people. For millennials <strong>of</strong> a certain vintage, they<br />

are a conduit <strong>of</strong> CD-era nostalgia. For casual fans who still have<br />

“Soul Meets Body” on their dinner party playlist, they are reliable<br />

purveyors <strong>of</strong> earnestness and emotional acuity. And since the<br />

departure <strong>of</strong> founding member Chris Walla, they have seemed,<br />

increasingly, a platform for singer/songwriter Ben Gibbard,<br />

whose breakup with Zooey Deschanel provided the subtext for a<br />

couple <strong>of</strong> the band’s more languid affairs.<br />

It’s been a while since Death Cab for Cutie actually felt like a<br />

band, an entity whose sound is summoned from the chemistry<br />

and interplay <strong>of</strong> its individual members, whose distinctions lie in<br />

more than just the personality <strong>of</strong> their lead singer. That changes<br />

with Asphalt Meadows, which is less a return-to-form than a<br />

flat-out late-career renaissance. Their most engaging record<br />

since Transatlanticism, Asphalt Meadows is vigorous, tense, and<br />

visceral. When is the last time this band worked up a full head <strong>of</strong><br />

steam the way they do on the driving “I Miss Strangers,” or flirted<br />

with abrasion like they do on the aptly-named “Roman Candles?”<br />

When’s the last time they locked into a head-bobbing beat like<br />

the one that powers the title song, or seemed as adventurous as<br />

they do on the fractured “Foxglove Through the Clearcut?”<br />

Asphalt Meadows is the work <strong>of</strong> a band that has long mastered<br />

tone and texture, but here remembers how much fun it is to stir<br />

up a ruckus together. Perhaps it’s inevitable that their newfound<br />

vim is pent-up pandemic antiness, something that’s also<br />

reflected in Gibbard’s lyrics. The album opens with a song called<br />

“I Don’t Know How I Survive,” its <strong>of</strong>f-handed despair setting the<br />

tone for songs that are by turns nervous, wistful, and resolute.<br />

“Rand McNally” is shameless in its nostalgia, and all the more<br />

affecting because <strong>of</strong> it; meanwhile, “I Miss Strangers” reckons<br />

honestly with the displacing effects <strong>of</strong> quarantine. And then<br />

there’s the final song, which thumps, thuds, and lurches,<br />

sounding wizened and confident. It’s called “I’ll Never Give Up on<br />

You,” which <strong>of</strong>fers a reassurance that the band’s wrestling match<br />

with despair has concluded, at least for now, with some kind <strong>of</strong> a<br />

truce. — JOSH HURST<br />

7

#18 — SHEBANG<br />

Oren Ambarchi<br />

There is a duality at the heart <strong>of</strong> Oren Ambarchi’s music. There’s<br />

Oren Ambarchi the performer, a totally unique guitarist who plays<br />

in free improvised settings with the likes <strong>of</strong> Keiji Haino, Jim<br />

O’Rourke, Keith Rowe, and Stephen O’Malley. And then there is the<br />

Oren Ambarchi <strong>of</strong> the studio, a sort <strong>of</strong> modern Teo Macero,<br />

constructing these towering long-form works out <strong>of</strong> bits and<br />

pieces recorded at different times by disparate ensembles. His<br />

pair <strong>of</strong> releases this past year exemplifies that duality: there’s<br />

Ghosted, a semi-improvisational trio performance with bassist<br />

Johan Berthling and drummer Andreas Werliin that was recorded<br />

live, in a single room, with minimal overdubs; and then there’s<br />

Shebang, which features an extensive cast <strong>of</strong> guest performers,<br />

recorded all over the world over the course <strong>of</strong> five years, and<br />

meticulously edited into a 35-minute piece. Remarkably, both<br />

sides <strong>of</strong> Ambarchi’s musical practice share a unified, easily<br />

identifiable sound, but it’s fascinating that the respective<br />

methods <strong>of</strong> arriving at that sound are completely opposed.<br />

Ambarchi’s career arc also has a binary quality: we can divide his<br />

solo discography rather cleanly into pre- and post-“Knots.” That’s<br />

not a quality judgment (records like Grapes From The Estate<br />

[2004] or In The Pendulum’s Embrace [2007] remain classics); it’s<br />

just that all <strong>of</strong> his studio work in the last decade seems part <strong>of</strong> a<br />

distinct lineage that can be traced back to the epic 33-minute<br />

track that dominated his 2012 record Audience Of One. “Knots” is<br />

built around the skittering ride cymbal work <strong>of</strong> Joe Talia, which<br />

acts as an uneven pulse propelling the piece forward. From<br />

there, Ambarchi layers various sounds — strings, horns,<br />

processed voices — and gradually builds them into a massive<br />

droning crescendo, with his own cacophonous guitar soloing over<br />

the top. It’s fairly simple, but in Ambarchi’s hands, the effect is<br />

completely mesmerizing, and it’s provided a basic formula from<br />

which he’s worked out all sorts <strong>of</strong> variations.<br />

If any single emphasis can define Ambarchi’s post-“Knots” work,<br />

it’s a fascination with rhythm. Sagittarian Domain, Quixotism,<br />

Simian Angel: each <strong>of</strong> these records is in one way or another a<br />

sort <strong>of</strong> exploratory rhythmic study, investigating and expanding<br />

8

on ideas culled from Outside The Dream Syndicate to minimal<br />

techno to Brazilian percussion masters like Nana Vasconcelos.<br />

And along with the heavier and more Krautrock-indebted Hubris<br />

from 2016, Shebang is probably his most rhythmically intricate<br />

record. It begins with a lone electric guitar picking a wonky<br />

pattern, though it soon splits into multiple voices, which weave<br />

around each other in a way that recalls Pat Metheny’s<br />

performance <strong>of</strong> Steve Reich’s Electric Counterpoint. As the guitar<br />

layers continue to build gradually, along with some added bass<br />

tones, Talia enters on drums, his colorful cymbal work<br />

reminiscent <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> Ambarchi’s heroes, Jack DeJohnette. As<br />

the piece unfurls, its complex rhythms gradually shifting and<br />

evolving, it becomes something <strong>of</strong> a sequence <strong>of</strong> solo spots. B.J.<br />

Cole on pedal steel, Chris Abrahams on piano, Julia Reidy on<br />

12-string guitar, Jim O’Rourke’s synthesizer drone — they each<br />

get a moment in the spotlight. And then, as the piece reaches its<br />

climax, it sounds as if many (if not all) <strong>of</strong> the featured soloists<br />

make their return, massing together to form a single, shimmering<br />

cloud <strong>of</strong> sound.<br />

Many <strong>of</strong> Ambarchi’s touchpoints — classical minimalism, ’70s and<br />

’80s ECM-style jazz fusion, krautrock, and Berlin school electronic<br />

— are genres and movements that feel firmly rooted in very<br />

specific time periods, but he is able to bring those sounds into<br />

the present in a way very few <strong>of</strong> his contemporaries can. For all<br />

<strong>of</strong> its historical references, Shebang still manages to feel<br />

downright modern. — BRENDAN NAGLE<br />

#17 — AETHIOPES<br />

billy woods<br />

billy woods’ vivid, theatrical approach to rap storytelling reached<br />

its apex this year with Aethiopes, a full-length collaboration with<br />

producer and tour DJ Preservation. The record caps <strong>of</strong>f a decade<br />

<strong>of</strong> writerly exercises beginning with 2012’s History Will Absolve Me,<br />

whose shrapnel-like soundscapes seemed to capture the end <strong>of</strong><br />

history while reckoning with its buried truths. woods’ releases in<br />

the years since — comprising solo albums, a sustained<br />

collaboration with Elucid as Armand Hammer, and an excellent<br />

one-<strong>of</strong>f with Moor Mother in 2020 — have mined similar subjects<br />

with impressive results, though only occasionally crossing over<br />

with non-rap listeners (as on 2019’s Hiding Places and 2021’s<br />

Haram). Aethiopes mints woods as a mainstay among this fickler<br />

indie crowd, while also positioning the rapper as an unexpectedly<br />

persuasive nexus point between the past and present eras <strong>of</strong><br />

NYC rap music. Members <strong>of</strong> early-2000s record label Def Jux and<br />

the Weathermen share space with newer rappers on the abstract<br />

fringes, and boom bap hero Boldy James even makes a welcome<br />

appearance. The record’s larger chorus lends woods the quality<br />

<strong>of</strong> protagonist as well as author, and Preservation’s<br />

sample-heavy smorgasbord weaves woods into Aethiopes’ other<br />

voices and sounds, creating a diasporic tapestry <strong>of</strong> collective<br />

identity.<br />

Aethiopes announces its sweeping aspirations early with opener<br />

“Asylum,” on which discordant piano and woodwinds soundtrack<br />

an imaginative child’s theories about a neighbor in political exile.<br />

woods’ usual attention to detail is especially pronounced, his<br />

narrator (who may or may not be billy woods himself) tracking<br />

daily routines next door and little changes in the crumbling<br />

facade <strong>of</strong> normalcy. Aethiopes is peppered with moments <strong>of</strong> such<br />

exactitude in identifying global dispossession, tracing not just<br />

people but objects like Queen Elizabeth’s Ashanti gold necklace<br />

(“Harlem”) and rooms full <strong>of</strong> Incan treasure (“Remorseless”). With<br />

lyrics that abruptly transverse childhood and adulthood — and<br />

imagine the far future on the grimy “NYNEX” — listening to<br />

Aethiopes can give the impression not just <strong>of</strong> a work greater than<br />

the sum <strong>of</strong> its parts, but one whose sheer number <strong>of</strong> parts<br />

overwhelms. Yet Preservation’s cinematic backdrop ensures that<br />

the clamor is never anything less than artfully unpolished,<br />

enveloping the game <strong>of</strong> rapper hot potato “Heavy Water” with<br />

searing percussion, and pairing woods’ diary scrawls with blaring<br />

horns on “No Hard Feelings,” elevating the album highlight to<br />

apocalypse-level urgency. Closing track “Smith + Cross”<br />

concludes Aethiopes with a moment <strong>of</strong> poetic self-recognition in<br />

a museum diorama, woods in effect identifying himself within<br />

both his lineage and its historicization. Few other <strong>2022</strong> albums,<br />

rap or otherwise, collected worlds within worlds with comparable<br />

heft or grandeur. — MICHAEL DOUB<br />

9

#16 — SOS<br />

SZA<br />

Take a look around at some other year-end music lists and you’ll<br />

quickly realize just how much there’s still an appetite for the type<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>f-kilter, understated R&B that SZA nailed so perfectly on her<br />

critically and commercially celebrated 2017 breakthrough Ctrl. So<br />

give the last real star on Top Dawg’s roster some credit for having<br />

the fortitude to record an hour-plus album this breathlessly<br />

eclectic and inventive, this insistent on flexing its artist’s range<br />

rather than playing in the pocket. The first proper song on SOS<br />

sets the table, and anticipates a smorgasbord: “Kill Bill” is equal<br />

parts sweet and squirmy, with fluttering falsetto and trips to the<br />

farmer’s market sharing space with a chronically shifty drum<br />

machine and multiple murder plots. It may have been Mountain<br />

Goats mastermind John Darnielle who formally declared that his<br />

<strong>2022</strong> album was “inspired” by action movie plotting, but SZA’s<br />

writing on SOS also draws heavily on the heightened emotional<br />

and narrative stakes found in a broad range <strong>of</strong> genre films. On<br />

the surface, the album’s tales <strong>of</strong> romantic misadventure, messy<br />

breakups, and lingering jealousies may not be too far afield from<br />

those <strong>of</strong> Ctrl, but the cinematic breadth <strong>of</strong> the production<br />

punches up the drama, and<br />

proves the perfect backdrop for the various narrator’s<br />

sensationalized antics.<br />

The girl on “Shirt” wears bloodstains from a run-in with a bitch<br />

who got on her nerves like a badge <strong>of</strong> honor, while the one on<br />

“Seek & Destroy” likens her lovelorn pursuit to “the art <strong>of</strong> war” and<br />

is serious enough about it to have “missiles deployed.” Sometimes<br />

we find even an ostensibly happy heroine, like the one <strong>of</strong><br />

“Snooze,” still “mobbin', schemin', lootin’, and hidin’ bodies.” That<br />

the more aggressive songs here sit unassumingly alongside<br />

swooning romantic gestures like Travis Scott duet “Open Arms”<br />

and the gorgeous, countrified Mazzy Star homage “Nobody Gets<br />

Me” speaks less to any incoherence <strong>of</strong> concept than it does to<br />

SZA’s all-encompassing vision. The sprawl <strong>of</strong> SOS plays like a<br />

whole summer season <strong>of</strong> blockbusters, and a few breakout indies<br />

(the low-key character study <strong>of</strong> “Blind” being a major highlight),<br />

stuffed into one uncommonly generous album. And even at its<br />

most marquee-ready, SOS never sacrifices the idiosyncratic<br />

approach to writing that endeared so many to this artist in the<br />

first place. SZA’s feel for young women’s anxieties, insecurities,<br />

but also their sources <strong>of</strong> strength, independence, and<br />

individuality, is as strong as ever, and feels even more assertive<br />

and culturally consequential in this wide-screen format than it<br />

did on her debut. — SAM C. MAC<br />

10

11<br />

#15 — BOAT SONGS<br />

MJ Lenderman<br />

On "TLC Cagematch," the third song on MJ Lenderman's<br />

breakthrough album Boat Songs, the singer-songwriter<br />

sorrowfully reflects on the passage <strong>of</strong> time while watching pro<br />

wrestling in his living room. "I always believed it, every time you<br />

said you're gonna be like our hero someday / Well, baby, all our<br />

heroes now are dead, 'cause all things go," he sings, his lilt<br />

drenched in the same melancholy that made Jason Molina an<br />

alt-country icon. Much like Molina's early material as Songs: Ohia,<br />

Lenderman fuses dusty country fables with sparse indie rock<br />

production, although his rural vignettes also share a lot in<br />

common with the arboraceous solipsism <strong>of</strong> Will Oldham's<br />

numerous musical identities. After two firmly DIY releases —<br />

2019's sprawling, self-titled debut and last year's hazy Ghost <strong>of</strong><br />

Your Guitar Solo — the Asheville musician's latest ascends into<br />

higher fidelity, while still maintaining the homespun<br />

straightforwardness that gave those previous records their<br />

rough-around-the-edges coziness.<br />

Boat Songs represents a sort <strong>of</strong> middle ground between the<br />

ambitious opuses <strong>of</strong> his first LP and the Guided by Voices-esque<br />

minimalism <strong>of</strong> his second, and whether his denim-and-flannel<br />

drawl is tangling with laid-back guitar strums or pushing through<br />

walls <strong>of</strong> distortion, Lenderman's gentle songwriting sensibility<br />

lends itself just as easily to tales <strong>of</strong> NBA legends (allegedly)<br />

playing through a hangover ("Hangover Game") as it does to<br />

folksy aphorisms (the refrain <strong>of</strong> "Don't remind me, what I already<br />

know" on the balladic album highlight "Under Control"). On the<br />

fuzz-laden "SUV," he amplifies snapshots <strong>of</strong> post-breakup<br />

awkwardness with punk rock urgency before ultimately planting<br />

his sad sack in front <strong>of</strong> the TV just like he did two songs earlier.<br />

The funereal slowcore <strong>of</strong> album closer "Six Flags" breaches<br />

similar thematic territory to even more devastating results ("No<br />

one could notice / I have never / felt alone / the way I did / at the<br />

Six Flags over Texas"), Lenderman finishing the record <strong>of</strong>f with a<br />

tar-spitting guitar solo.<br />

There is an immediate, uncomplicated beauty to Boat Songs, one<br />

where the simple pleasures <strong>of</strong> Jackass aren't given more or less<br />

weight than memories <strong>of</strong> happy summers spent getting wasted<br />

and loafing around drained swimming pools. It's about going<br />

through life, failing, falling, getting back up again, and finding<br />

some happiness along the way. Fame, beauty, and youth all fade<br />

eventually, but so does pain, and so does sadness. We're all just<br />

trying our best: "And that's why we do what we gotta do to get<br />

through / And I know life will make us crazy, I do." — FRED<br />

BARRETT

#14 — IT’S ALMOST DRY<br />

Pusha T<br />

Virginia rap legend Pusha T's hotly anticipated fourth LP It's<br />

Almost Dry opens with the ghostly keys <strong>of</strong> "Brambleton," a<br />

Pharrell-produced introduction which sees the 44-year-old<br />

rapper exploring the fractured relationship with his former<br />

manager Anthony "Geezy" Gonzales. It's a deeply personal way to<br />

open an album, especially coming from an MC most famous for<br />

braggadocious bars about slinging cocaine. "It was sad watching<br />

dude in Vlad interviews . . . Had a million answers, didn't have a<br />

clue, why Michael kissed Fredo in Godfather II," spits King Push,<br />

referencing his former confidant's infamous interview with DJ<br />

Vlad. In spite <strong>of</strong> allowing himself some vulnerability, his flow<br />

remains as assured as ever, and when he spins a drug-dealing<br />

tale on the follow-up track "Let the Smokers Shine the Coupes,"<br />

his presence becomes unmistakable. It's not just Pharrell who<br />

gets to leave his fingerprints all over the record, however, as the<br />

other half <strong>of</strong> the 12-song tracklist is produced by none other than<br />

a pre-heel turn Ye, his collaborations with Pusha having proven<br />

fruitful since 2005. Contrasting Pharrell's eerie beats with clipped<br />

and pitched-up soul samples, "Dreamin <strong>of</strong> the Past" and the<br />

engrossing "Rock n Roll" also see the controversial<br />

rapper-producer make time to drop two verses <strong>of</strong> his own.<br />

It's Almost Dry not only boasts an impressive sonic variety but<br />

also a rogue’s gallery <strong>of</strong> guest MCs. Jay-Z, Kid Cudi, and Lil Uzi<br />

Vert all feature on the album, adding some additional star power<br />

to the proceedings. Jay-Z's verse on "Neck & Wrist" stands out in<br />

particular for containing some <strong>of</strong> the New York rapper's best<br />

rhymes in a long time ("I blew bird money, y'all talkin' Twitter<br />

feed/We got different Saab stories, save your soliloquies"). The<br />

LP's best moment might come at the very end, though, in the<br />

form <strong>of</strong> album closer "I Pray for You." Produced by Labrinth and<br />

Ye, the track's soul-tinged plaintiveness and organ-heavy<br />

instrumentation make for a reflective, somber finale. Pusha raps<br />

about his accomplishments with<br />

lines like, "Rarely do you see the<br />

Phoenix rise from the<br />

ashes/Lightnin' struck twice on<br />

four classics," celebrating both his<br />

history and reunion with his<br />

brother and former Clipse partner,<br />

No Malice, who also appears on<br />

the song (and refers to himself as<br />

Malice for the first time since<br />

2012). Even with his prominent<br />

guests, it's clear that few rappers<br />

can match Pusha's lyricism, and<br />

his most boastful<br />

rhymes make it clear that he is keenly aware <strong>of</strong> that fact<br />

("Service with a smile when I hand out halos"). Still, it's the<br />

moments <strong>of</strong> quiet doubt and lingering regrets that resonate long<br />

after the album has faded into silence. — FRED BARRETT<br />

#13 — CREST<br />

Bladee & Ecco2k<br />

Those in need <strong>of</strong> religion in <strong>2022</strong> could do no better than to join<br />

the cult <strong>of</strong> Drain Gang. Despite being an outfit that appeals more<br />

to a hyper-online Zoomer generation, it’s actually tough <strong>of</strong>f the<br />

top to come up with a more sincere project out there, the<br />

collective’s post-irony leanings making for consistently gentle<br />

records from the quintet <strong>of</strong> Bladee, Ecco2K, Thaiboy Digital, Yung<br />

Sherman, and Whitearmor. Despite arriving at a similar cultural<br />

12

and artistic moment and occupying shared aesthetic space as<br />

other SoundCloud hip hop cum hyperpop cum emo rap groups<br />

like Goth Boi Clique or 100 Gecs, Bladee and co. have created<br />

distance from those projects on the strength <strong>of</strong> their easy<br />

ebullience and throwback peace-and-love optimism. Rather than<br />

saturating their efforts in #sadboi hedonism or crafting them for<br />

maximum wink value, Drain Gang consistently (and increasingly)<br />

feels untethered from such trivial terrestrial concerns — they<br />

may be in this world, but they’re not <strong>of</strong> it.<br />

In that sense, then, Crest may be<br />

the spiritual album <strong>of</strong> the year, and<br />

intentionally so. But unlike the<br />

album that angled for and indeed<br />

took on that mantle in 2021, these<br />

young bucks aren’t likely to out<br />

themselves as Hitler apologists in<br />

the coming year. That’s in no small<br />

part because none <strong>of</strong> the toxic<br />

dogma <strong>of</strong> Christianity rears its ugly<br />

head on Crest, despite playing<br />

loose with such iconography and<br />

language on these tracks — “Gloria<br />

in excelsis, Deo, Deo / Excelsior, we<br />

excel everything and anything” on “5 Star Crest (4 Vattenrum)”;<br />

“Everlasting / Flowers bloom / Never-ending / Story <strong>of</strong> my life /<br />

Ballad for the sins” on “Girls just want to have fun” — and instead<br />

the prevailing ethos is <strong>of</strong> a far more zenned-out Buddhist variety<br />

(“We think we exist / that’s why we suffer”), celebrating community<br />

and kinship, the pursuit <strong>of</strong> beauty and nirvana. On Crest, the fog<br />

<strong>of</strong> abstraction is its own kind <strong>of</strong> heaven.<br />

All <strong>of</strong> this psychedelic-tinged earnestness, spiritually descended<br />

from the ‘60s folk scene more than anything, swirls within<br />

Whitearmor’s twinkly EDM noodling, layered to the point <strong>of</strong><br />

appealing chaos, foregrounding the early house at its core when<br />

it’s not fulling leaning into the sonics <strong>of</strong> anime soundtracking,<br />

while at other times stripping things back to highlight the<br />

influence <strong>of</strong> something like early-aughts, nu-hippie oddity<br />

Nanook <strong>of</strong> the North’s The Taby Tapes. Of course, the collective<br />

has been perfecting this formula for a decade at this point, their<br />

interpolation <strong>of</strong> a more keenly observed spirituality becoming<br />

increasingly refined with each successive effort (and it’s worth<br />

noting that this likewise applies to Bladee’s solo effort this year,<br />

Spiderr). But what stands out most in <strong>2022</strong> — a year that saw<br />

some <strong>of</strong> the world’s biggest stars and clearest voices detour into<br />

the history-rich world <strong>of</strong> carnal club music — is how truly pure<br />

and redeeming this humble Swedish outfit is to our troubled<br />

world. And all Drain’s people said, amen. — LUKE GORHAM<br />

#12 — ANTS FROM UP THERE<br />

Black Country, New Road<br />

It’s quite exciting and a little surprising to take stock <strong>of</strong> how<br />

young Cambridgeshire septette Black Country, New Road —<br />

whose members are still roughly in their early 20s, though they<br />

are now <strong>of</strong>ficially a sextette after lead singer Isaac Wood’s<br />

departure — so naturally and briskly reinvented their music since<br />

the release <strong>of</strong> their 2021 breakthrough debut record, For the First<br />

Time. Without entirely disavowing the the core characteristics<br />

and distinctive sounds <strong>of</strong> that impressive album, BCNR does<br />

depart somewhat from that post-punk style and those Tool-ish<br />

effects on Ants From Up There, embracing the much more<br />

explicitly the prog rock influences <strong>of</strong> prominent British groups <strong>of</strong><br />

the ‘70s — a luscious hodgepodge <strong>of</strong> Gentle Giant, King Crimson,<br />

13

and Van der Graaf Generator, as well as so-called Canterbury<br />

scene acts like Caravan and S<strong>of</strong>t Machine — and reinterpreting to<br />

edgier and more modern effect: (“She had Billie Eilish style /<br />

Moving to Berlin for a little while”). As much as the title <strong>of</strong> the<br />

album itself suggests a certain surreal, maybe even Dadaist<br />

quality (“So clean your soup maker and breathe in / Your chicken<br />

broccoli and everything”), sometimes even recalling Syd Barrett’s<br />

psychedelic dwams, when it comes to the group’s outlandish<br />

lyricism, it’s as if random recollections <strong>of</strong> memory or scattered<br />

excerpts from a diary have been plucked for us: “This staircase —<br />

it leads only to / Some old pictures <strong>of</strong> you”). On the other hand,<br />

BCNR’s poetic musings can also take more conceptual shape,<br />

twining romantic concerns, fantastical reveries, and even<br />

domesticity — “And every phone died then / And no-one had WiFi<br />

inside your apartment, from “Bread Song”; “Concorde flies in my<br />

room / Tears the house to shreds,” from “Basketball Shoes” —<br />

which feels like a potential instance <strong>of</strong> our post-pandemic era’s<br />

inclination toward blending mundane minutiae with sublime<br />

beauty.<br />

Extending this notion, it also seems that the album’s inflections —<br />

especially when we consider how much Wood’s timbres are owed<br />

to the singular vocal expressions and performances <strong>of</strong> David<br />

Bowie, most notable in “Chaos Space Marine” — intend to create a<br />

specific soundscape for listeners’ perceptions and imaginations<br />

rather than necessarily convey any clear meaning: take “Snow<br />

Globes,” for example: “A small nation <strong>of</strong> souvenirs / Make Henry<br />

whole but porously / Oh, god <strong>of</strong> weather, Henry knows / Snow<br />

globes don’t shake on their own.” As Wood’s vocals, alternately<br />

placid and psyched-out from one song to the next, attempt to<br />

extract the essential musicality <strong>of</strong> the words, the band’s<br />

instrumentation delivers the most expressive and impressive<br />

sounds as a canvas for listeners. It’s particularly remarkable to<br />

hear Georgia Ellery’s strings, Lewis Evans’ flutes & saxophone,<br />

and May Kershaw’s keyboards and percussions entwine the<br />

tracks’ colorful emotions with expectedly more pensive post-rock<br />

structures laid down by Luke Mark, Tyler Hyde, and Charlie<br />

Wayne’s guitar, bass, and drum trio. And so, as kaleidoscopic and<br />

unpredictable as Ants from Up There proves to<br />

14

Be (as only a sophomore record, at that), it’s tough not to already<br />

be looking forward — given how artistically open-minded BCNR<br />

has proven to be — to where exactly these curious rockers<br />

choose to go next. — AYEEN FOROOTAN<br />

#11 — PREACHER’S DAUGHTER<br />

Ethel Cain<br />

Ethel Cain’s debut album, Preacher’s Daughter, soared onto the<br />

scene in <strong>2022</strong> (on the heels <strong>of</strong> her incredibly popular EP in 2021),<br />

firmly entrenching her as a new indie darling du jour. Moving<br />

beyond the world <strong>of</strong> TikTok stardom and late-stage bedroom pop<br />

aesthetics, Cain rips into the heart <strong>of</strong> middle America’s<br />

depressive tendencies. While such thematizing would feel forced<br />

from a lesser artist, there’s a real camaraderie in these sweeping<br />

sounds that primes the record to easily steal the hearts <strong>of</strong><br />

flyover country listeners in particular. There’s a tone <strong>of</strong> deep<br />

knowledge that informs the emotionally resonant content, a dual<br />

force that sustains the lengthy runtime <strong>of</strong> the album. Clocking in<br />

at just under 80 minutes, it’s nearly a miracle how well this<br />

works, succeeding so thoroughly with an approach that might<br />

seem antithetical to the fast pace and limited attention span <strong>of</strong><br />

the artist’s core fanbase.<br />

There’s always something bubbling on the edge <strong>of</strong> Preacher’s<br />

Daughter’s tracks, tense instrumentals fusing with smooth vocals<br />

so that it feels like the songs could explode at any moment. It<br />

shows an immense amount <strong>of</strong> restraint to avoid following<br />

through on that, but taking the long way around on the tracks<br />

pays <strong>of</strong>f immensely. Tracks expand far beyond what Cain’s typical<br />

pop counterparts would choose, instead opting for sprawling<br />

seven-minute takes that dive into the depths <strong>of</strong> what it feels like<br />

to be alive. It’s an ambitious approach for such a new artist, but<br />

refreshing within the sea <strong>of</strong> similarity to which the album was<br />

dropped. Cain’s Southern Baptist upbringing created the<br />

framework for the album’s various pieces: cuts here are sonically<br />

reminiscent <strong>of</strong> hyper-religious ballads and contemporary praise<br />

songs that are so common in Cain’s neck <strong>of</strong> the woods, but she<br />

approaches this template with a vein <strong>of</strong> darkness: the impression<br />

can <strong>of</strong>ten feel like a church service led<br />

by Lana Del Rey. The lyrics are a foil to this facade <strong>of</strong> worship,<br />

instead speaking with contempt about the American Dream that<br />

failed so many around her, notably on the rare uptempo track,<br />

single “American Teenager.” The systems Cain condemns have<br />

failed the people that they were designed to protect, many <strong>of</strong><br />

whom reside in the small towns that the artist uses as<br />

perspective on the album.<br />

“… the impression can <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

feel like a church service led<br />

by Lana Del Rey.<br />

Like the designed languor <strong>of</strong> a litany, Preacher’s Daughter’s<br />

pacing affects the listener, making them feel as if they are being<br />

consumed by the world and word. Cain <strong>of</strong>fers a glimpse inside<br />

the challenging reality <strong>of</strong> a nation torn apart by religious zealotry,<br />

foreign wars, an ongoing opioid crisis, and crippling depression,<br />

and asks listeners to sit inside this space. As the album<br />

progresses, these forces build, and challenge the very notion <strong>of</strong><br />

artistic creation in such a world. Through the ashes, Ethel Cain<br />

rises and razes, diving deeper and deeper into the crushing<br />

nature <strong>of</strong> a late-capitalist society. While such an ambitious and<br />

thrilling debut album will prove difficult to top, Cain consistently<br />

proves across Preacher’s Daughter precisely how deceiving<br />

expectations can be. — ANDREW BOSMA<br />

#10 — MR. MORALE & THE BIG STEPPERS<br />

Kendrick Lamar<br />

Celebrity worship is out in <strong>2022</strong>. At this point, we expect our<br />

superstars to have a downward spiral after reaching the top. It’s<br />

essentially written into the script. This year has seen a few<br />

artists inflict critical damage to their own public image, to say<br />

the least. But unlike the other guy, Kendrick Lamar is clearly<br />

doing the work. Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers feels less like a<br />

ticking time bomb, and more like the product <strong>of</strong> intense<br />

self-reflection over his own sins, trauma, ego, and perfectionism.<br />

Therapy, but make it art — in doing so, Kendrick proves why he’s<br />

still the best lyricist in the game, not in spite <strong>of</strong> his flaws but<br />

because <strong>of</strong> them. The result is the best lyrical rap album <strong>of</strong> <strong>2022</strong>.<br />

15

Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers is largely a story about grace. The<br />

pressure to be perfect has never been stronger than it is in<br />

America today. In a nation where fifteen minutes <strong>of</strong> fame is just<br />

one viral post away, anyone has the potential to be the hero or<br />

villain <strong>of</strong> the day. The consequences for the villain are clear:<br />

public outcry, humiliation, and pariahship. We can’t always cancel<br />

the villains in our own lives, so we burn our celebrities in effigy.<br />

The consequences for the hero are more complicated. We uplift<br />

our heroes to godlike levels. We look to them as role models and<br />

project our own personal politics and expectations onto them.<br />

And when they fail to meet these expectations, or fit neatly into<br />

our little boxes, the Internet is quick to admonish them.<br />

“Kendrick’s deconstruction <strong>of</strong><br />

his air-tight public image<br />

largely makes the project<br />

such a challenging and<br />

uncomfortable listen.<br />

Kendrick has been lionized as the savior <strong>of</strong> rap his whole career.<br />

College courses have been taught about him since good kid,<br />

m.A.A.d city dropped. “But I am not your savior,” he says on Mr.<br />

Morale. While artists have long made music in response to<br />

negative criticism, this album feels like a reaction to the critical<br />

adoration Kendrick has received for each project he’s released.<br />

Kendrick’s deconstruction <strong>of</strong> his air-tight public image largely<br />

makes the project such a challenging and uncomfortable listen.<br />

We didn’t expect an album like this from the man who made To<br />

Pimp A Butterfly and won a Pulitzer for DAMN. Kendrick makes<br />

clear on Mr. Morale that the crown he wears is heavy.<br />

“I’m the biggest hypocrite <strong>of</strong> 2015,” Kendrick warned way back on<br />

Butterfly’s “The Blacker the Berry.” It felt almost sacrilegious<br />

coming from rap’s messiah. But every human being is a hypocrite<br />

at one point or another. Grace isn’t about giving villains a pass,<br />

but recognizing that no one fits neatly into a box <strong>of</strong> “good” or<br />

“bad.” To live in a state <strong>of</strong> grace, you have to believe that “good”<br />

people make mistakes and that “bad” people can change.<br />

The past decade has seen a rejection <strong>of</strong> the manufactured<br />

popstar image that was so prevalent in the late ‘’90s and ‘00s era<br />

<strong>of</strong> sugar-coated teen pop. While we still place our artists on<br />

pedestals, we don’t want them to feel like they’re all the way at<br />

the top looking down. We want them to feel relatable. We want to<br />

feel like we really know them. From Beyoncé to Billie Eilish, our<br />

favorite artists have let us into their lives through documentaries<br />

and social media confessionals in an attempt to make us feel like<br />

they’re just like us — only richer, hotter, and better in every way.<br />

In reality, the parts <strong>of</strong> themselves our stars allow us to see are<br />

only based on a true story. What Kendrick does on Mr. Morale<br />

feels far from fake. More than any other genre, realness is central<br />

to the hip hop tradition. And this is the most real rap’s reigning<br />

king has ever been. — NICK SEIP<br />

#9 — THE LONELIEST TIME<br />

Carly Rae Jepsen<br />

Sometimes, a collection <strong>of</strong> great, loosely-related pop songs is all<br />

an album needs to succeed, and few artists can be trusted to<br />

express the joy and emotional clarity <strong>of</strong> pop music better than<br />

Carly Rae Jepsen. Even as poptimism has become a more<br />

conflicted concept in recent years, her music has remained a<br />

vibrant escape from disillusionment. The Loneliest Time sparkles<br />

with glossy pop production: the pulsing bass <strong>of</strong> “Bad Thing Twice”<br />

and “Anxious,” the froth and fizz <strong>of</strong> “Shooting Star” and “So Nice,”<br />

the explosive glitz <strong>of</strong> “Talking to Yourself,” the delicate ballad<br />

arrangement <strong>of</strong> “Go Find Yourself or Whatever,” and more all add<br />

up to some <strong>of</strong> the best-sounding tracks <strong>of</strong> Jepsen’s career.<br />

Frequent collaborators like Tavish Crowe, Kyle Shearer, and John<br />

Hill return, as well as Rostam Batmanglij for his first credits with<br />

Jepsen since 2015’s “Warm Blood.”<br />

16

The Loneliest Time opens in familiar territory as Jepsen serves<br />

up the type <strong>of</strong> bombastic synthpop she’s best known for.<br />

“Surrender My Heart” begins the album with a passionate,<br />

synth-soaked declaration that she wants to get closer; “I wanna<br />

be honest with you.” Immediately after, “Joshua Tree” goes for<br />

more minimal dance-pop, and there’s something classic about<br />

the playful “Boys around the world” hook in “Beach House” that<br />

brings to mind pop tracks from decades ago.<br />

The first six songs are all 3 minutes or less — “Sideways” doesn’t<br />

even clear 2:20 — which is one <strong>of</strong> the only concessions Jepsen<br />

makes to the changing pop landscape around her. But it doesn’t<br />

hinder the album: even when tracks like “Talking to Yourself”<br />

move through verses at lightning speed, the music still feels<br />

satisfying and well-resolved. Plus, as the tracklist progresses, the<br />

songs relax and lengthen anyway. Some <strong>of</strong> the record’s best<br />

moments come when Jepsen gives herself more space to unwind<br />

in acoustic-leaning arrangements such as lead single “Western<br />

Wind.” Maybe one day Jepsen will finally put out that<br />

Transcendentalist album, but for now, “Western Wind” joins<br />

Dedicated Side B’s “Now I Don’t Hate California After All” to tide us<br />

over during the wait.<br />

The most interesting recent evolution in Jepsen’s discography<br />

has been the growth <strong>of</strong> her ballads. The slow songs on Dedicated<br />

Side B were some <strong>of</strong> its best, but the ballads on The Loneliest<br />

Time are even more gorgeous. “Go Find Yourself or Whatever,” in<br />

particular, is a contender for best song on the album. Despite its<br />

silly-sounding title, it’s a pensive track with a beautiful vocal<br />

performance and perfect slow burn <strong>of</strong> an arrangement that<br />

builds from a single acoustic guitar to delicate layers <strong>of</strong> strings,<br />

piano, and backing vocals that swirl around Jepsen’s vulnerable<br />

goodbyes: “You feel safe in sorrow, and you feel safe on an open<br />

road / Go find yourself or whatever.” Bonus tracks “No Thinking<br />

Over the Weekend” and “Keep Away” are a sultry, spiraling slow<br />

jam and ’90s R&B-esque romantic slow dance, respectively.<br />

For an album titled after solitude, The Loneliest Time <strong>of</strong>ten fixates<br />

on companionship. The first track begins with Jepsen<br />

giving her heart away; the singles reach towards a lover<br />

(sincerely on “Wind,” exasperated with modern dating on “Beach<br />

House,” post-breakup on “Talking to Yourself”); the deep cuts find<br />

her memorializing a recently passed family member (“Bends”),<br />

choosing her heart over her head and going back to a partner<br />

(“Bad Thing Twice”), and asking for romantic reciprocation (“Far<br />

Away”). Solitude becomes loneliness when you admit that you<br />

wish someone else was there to fill the empty space: the songs<br />

<strong>of</strong> The Loneliest Time may outline this space, but they do so while<br />

looking at the silhouette <strong>of</strong> someone who used to occupy it, or<br />

else searching for someone new to step inside. It’s a project<br />

about Jepsen understanding herself that still makes room for<br />

listeners to come in close and feel a little less alone, thanks to<br />

her universal pop constructions. The last track <strong>of</strong> the standard<br />

edition concludes, “I’m coming over tonight / Knock on your door,<br />

just like before / I need that look in your eyes / Cause we’ve had<br />

the loneliest time.” Having struggled through insecurity and<br />

incompatibility but also having come out on the other side<br />

knowing what she needs, Jepsen finally chooses connection. —<br />

KAYLA BEARDSLEE<br />

#8 — HYPOCHONDRIAC<br />

Brakence<br />

“I’ve made a couple <strong>of</strong> beats / Then the whole net started capturing<br />

me / This shit’s so overwhelming / Mix self-expression with<br />

self-obsession”: so vividly declares Randy Findell, the Ohio-based<br />

singer and musician pr<strong>of</strong>essionally known by his stage-name<br />

Brakence, who gained a solid and dedicated cult fanbase upon<br />

rising to fame from the SoundCloud scene in the mid-2010s.<br />

What’s clear on Brakence’s Hypochondriac (even more so than on<br />

previous efforts) is that the record possesses a very rawly<br />

confessional and boldly confrontational artistic approach. It’s a<br />

complete oddity that, through an eccentric mix <strong>of</strong> Midwest<br />

hyperpop, emo rap, lo-fi indie rock, and glitchy electronica<br />

(occasionally infusing powerful drum beats or airy guitarwork,<br />

for example, in “Intellectual Greed”), crafts a prismatic sonic<br />

experience that delivers one <strong>of</strong> the year’s surprising “love at first<br />

listen” albums. In fact, what’s truly astonishing here about<br />

Brakence’s work is the unique way he alternates and subverts,<br />

17

say, the molecular structure <strong>of</strong> a single song to melodically<br />

constitute fresh chemical (or, perhaps more appropriately,<br />

digital) compounds for each and all <strong>of</strong> the compositions. The<br />

artist’s vocals, simultaneously familiar in their amiability and<br />

singular, and embracing various modes and moods — from s<strong>of</strong>tly<br />

autotuned croons and passionate whispers to vocals fierce with<br />

energy and falsettos that can even feel mildly aggressive — find a<br />

very delicate balance in order to arrange his quotidian and<br />

melancholy lyricism within the protean sonic experience <strong>of</strong><br />

Hypochondriac. And all <strong>of</strong> this is capped <strong>of</strong>f by the frequent<br />

connective narrations which lend a certain storytelling depth to<br />

the whole record.<br />

Brakence’s most personal battles are here realized through<br />

explicit symbolism revolving around God and the devil, angels<br />

and demons; sobriety and drug use are accorded various<br />

dualities — materialistic and spiritual, holy and hedonistic. It<br />

makes sense, then, that Hypochondriac manifests as an always<br />

morphing shape <strong>of</strong> sounds, constructed from crisp underlying<br />

beats, sharp sounds effects, noise-fueled distortions, and<br />

sudden tempo changes, all <strong>of</strong> which build to a<br />

dopamine-inducing mixture <strong>of</strong> the copacetic and chaotic. And<br />

there are the recurring lyrics motifs <strong>of</strong> sacrificial love (“I'm letting<br />

go <strong>of</strong> all <strong>of</strong> my vices / I'll make the sacrifice / It's all I can do To<br />

make me get over you,” from “Bugging”), various forms <strong>of</strong> pain<br />

(“Screening my own headache for pro<strong>of</strong> / The MRI was a misprint”,<br />

from “Preparation Exercise No. 7 (Trembling)”), trippy<br />

experimentation (“Then we vaporized ‘til our fates aligned / I think<br />

we frayed the twine / Tethering space and time,” from “Venus Fly<br />

Trap”), and constant existential musing (“Too excited about dying<br />

and blooming,” from “Deep Fake”). Indeed, “head” and “brain”<br />

might be the two most repeated words in Hypochondriac’s<br />

lexicon, revealing the extent to which the record uses abstraction<br />

and heady introspection to balance its clear emotionalism.<br />

This parity extends beyond the conceptual, though: as much as<br />

Brakence’s songs at once lyrically and compositionally in<br />

conversation with one another (in the sense that they shape a<br />

sort <strong>of</strong> loose concept album), they also succeed in entwining a<br />

meditative serenity with expressive, <strong>of</strong>ten dreamy wildness on<br />

the sonic front, rhythmically incorporating the chill <strong>of</strong> the<br />

downtempo and thrill <strong>of</strong> the bouncy and frenetic. Similarly, it’s<br />

interesting to see how Hypochondriac places an<br />

ultra-contemporary milieu <strong>of</strong> interpersonal entanglement (most<br />

evidently in a song like “5g”: “scrollin’ all night”; “he put me on a<br />

pedestal and liked my tweets”) in contrast with its more mystical<br />

fascinations for pre-industrial living (“And when I die, I hope I’m<br />

buried in a forest”). Even after a first listen, it’s hard not to agree<br />

with Brakence’s self-assessment in “Caffein”: he truly is “dope as<br />

fuck” and undeniably “glowing up.” — AYEEN FOROOTAN<br />

#7 — AND IN THE DARKNESS, HEARTS<br />

AGLOW<br />

Weyes Blood<br />

Though the release <strong>of</strong> Weyes Blood’s 2019 opus Titanic Rising<br />

already announced the singer-songwriter (born Natalie Mering)<br />

as poet laureate <strong>of</strong> the downer vibe, the years since have further<br />

reaffirmed the album’s prophetic qualities. Oriented around<br />

modern-day-specific subjects like climate change, Weyes Blood’s<br />

canny topical focus marked Titanic Rising not just as a resonant<br />

18

document <strong>of</strong> imperial decline, but one whose already ample<br />

poignancy was set up to deepen as things generally get worse.<br />

The first album in a planned trilogy about human species-level<br />

concerns, Weyes Blood returned this year with second<br />

installment, And In the Darkness, Hearts Aglow, a magisterial<br />

record whose breadth and beauty exceeds even its prodigious<br />

predecessor. Altogether more layered and lush, Hearts Aglow’s<br />

renewed commitment to unhurried tempos and slow builds<br />

testify to the confidence which results from having been<br />

validated and awarded for it. Compared to Titanic Rising, Weyes<br />

Blood’s latest release is less focused on disaster than the<br />

fractious personhood which emerges in its wake, adopting the<br />

individual and first-person plural perspectives <strong>of</strong> a despairing<br />

populace yearning for contact. A “pandemic record,” the<br />

observational acuity <strong>of</strong> Hearts Aglow provides a corrective to<br />

typically vapid Covid-era commentary, and to a musical<br />

landscape which can <strong>of</strong>ten lack for the album’s level <strong>of</strong> ambition<br />

and sophistication.<br />

productions keeps its reveries from sounding too sunny, with<br />

shadowy edges providing a reminder <strong>of</strong> overwhelming change’s<br />

encroachment. While grappling with such subjects can prompt<br />

no small amount <strong>of</strong> despair in those who consider them, Weyes<br />

Blood’s unflinching resolve, empathy, and wit largely keep Hearts<br />

Aglow swaying in the light. — MICHAEL DOUB<br />

#6 — RENAISSANCE<br />

Beyonce<br />

“I’m bout to explode!” Big Freedia first called for a “release” back<br />

in 2014 on her incendiary track “Explode.” “Release your anger,<br />

release your mind, release your job, release the time.” In <strong>2022</strong>,<br />

Beyoncé promised a “release” <strong>of</strong> her own with “Break My Soul,”<br />

the debut single <strong>of</strong>f her 7th studio album Renaissance. On it,<br />

Beyoncé amplifies Big Freedia’s call for catharsis and reinvents<br />

Robin S.’s house standard “Show Me Love” into an ebullient<br />

call-to-the-dancefloor fit for <strong>2022</strong>. In doing so, she established<br />

the theme for her upcoming album: it’s time to let it all out.<br />

The storytelling on Hearts Aglow occupies the internal realms <strong>of</strong><br />

its beset-upon narrators, describing psychologies shaped and<br />

challenged by external circumstance. Opening song “It’s Not Just<br />

You It’s Everybody” details the semi-universal experience <strong>of</strong><br />

feeling unseen at a party, before expanding outward to<br />

acknowledge loneliness’ grip on our culture at large. Similar<br />

attempts to situate oneself within a broader social fabric take<br />

creative forms throughout the album; people in “Children <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Empire” reject fear whilst scrambling to find a solid purchase for<br />

themselves, while album centerpiece “God Turn Me Into a Flower”<br />

frames transformation as another means <strong>of</strong> escaping oppression<br />

and narcissism. Like the pop music songbook writ large, love<br />

factors heavily in Weyes Blood’s transcendence, urging her past<br />

her breaking point on the booming “Grapevine,” and providing<br />

harbor from the storm on the album’s swooning title track.<br />

Gorgeous arrangements elevate these diaristic musings from<br />

inner monologue to full-blown sing-alongs, comprising a Laurel<br />