Spring-Summer 23

Restoration Conversations is a digital magazine spotlighting the achievements of women in history and today. We produce two issues a year: Spring/Summer and Fall/Winter

Restoration Conversations is a digital magazine spotlighting the achievements of women in history and today. We produce two issues a year: Spring/Summer and Fall/Winter

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

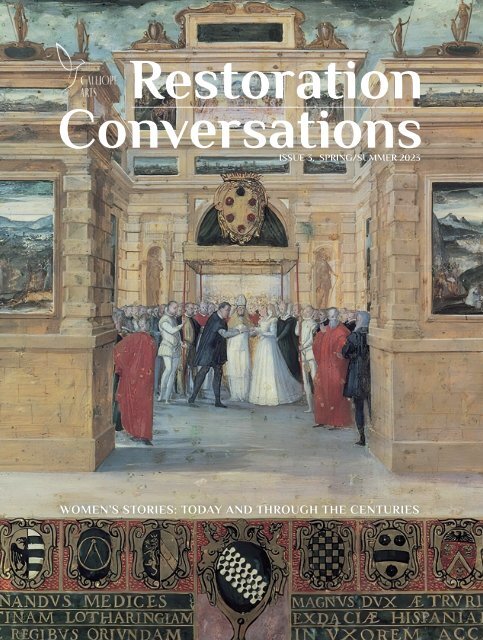

Restoration<br />

Conversations<br />

ISSUE 3, SPRING/SUMMER 20<strong>23</strong><br />

WOMEN’S STORIES: TODAY AND THROUGH THE CENTURIES<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong> • Restoration Conversations 1

Publisher<br />

Calliope Arts Ltd<br />

London, UK<br />

Managing Editor<br />

Linda Falcone<br />

Contributing Editor<br />

Margie MacKinnon<br />

Design<br />

Fiona Richards<br />

FPE Media Ltd<br />

Video maker for RC broadcasts<br />

Francesco Cacchiani<br />

Bunker Film<br />

www.calliopearts.org<br />

@calliopearts_restoration<br />

Calliope Arts<br />

2 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong>

From the Editor<br />

‘ Friends and Strangers’, the title of Margie MacKinnon’s article on the London-based<br />

exhibitions of painters Alice Neel and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye could be used to describe<br />

the whole of Restoration Conversations. Indeed, our <strong>Spring</strong> 20<strong>23</strong> issue comprises a<br />

series of ‘meetings’ with modern-day and historic women – who are, in some measure, both<br />

familiar and largely unknown. Many of their ‘facts’ may be known to us: we recall that Joan<br />

Mitchell painted in France, and that Catherine de’ Medici introduced the fork to that country.<br />

We may acknowledge our indebtedness to Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici who saved Florence’s<br />

art from being sold off bit by bit, once her family dynasty reached its end, or recognize many<br />

of the women included in Jann Haworth and Liberty Blake’s seven-panel monumental Work<br />

in Progress, at London’s soon-to-be reopened National Portrait Gallery. At the same time,<br />

each woman featured in these pages is like a world waiting to be discovered. Nicole-Reine<br />

Lepaute calculated a comet’s arrival more accurately than Halley himself. Lee Miller, best<br />

known by some as merely ‘a Surrealist muse’, had the guts to bathe in Hitler’s bathtub, the<br />

day his death was announced – while working as a ‘combat photographer’, reporting from<br />

his Munich flat.<br />

Then we have the modern-day women – custodians of culture and disseminators of knowledge<br />

– the writers, curators and scholars whose words populate this issue. A special mention is<br />

due to Dr Wendy Grossman, who shares with us her quest to rediscover Adrienne Fedelin.<br />

Her article ‘Hidden in plain sight’ is the magazine’s first-ever unsolicited submission – a<br />

small but significant sign of growth. As we conclude this issue, whose preparation ‘devoured<br />

the hours, as if the Sun were hungry’, I am reminded of Carl Jung and his discussion on how<br />

to identify one’s vocation in life: “What did you do as a child that made the hours pass like<br />

minutes? Herein, lies the key to your earthly pursuits,” the Swiss psychoanalyst wrote. As my<br />

adult-self looking back on the girl who ‘made magazines’ during playtime with cutouts and<br />

glue, I can only say how grateful I feel to see our minutes pass so quickly. Enjoy the issue!<br />

Fondly,<br />

Linda Falcone<br />

Managing Editor, Restoration Conversations<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong> • Restoration Conversations 3

GRAZIE MILLE<br />

As it says on the cover, conversations are at the heart of what we do to fulfil our<br />

mission of creating a greater awareness and appreciation of the achievements<br />

of women in the arts and sciences. Thank you to the curators, authors, art historians<br />

and art conservators who took the time to sit down and explain their work to<br />

us for this issue: Lorenzo Conti, Natacha Fabbri, Flavia Frigeri, Wendy Grossman,<br />

Jennifer Higgie, Paola Lucchesi, Angela Oberer, Barbara Salvadori, Claudia Tobin<br />

and Elizabeth Wicks.<br />

We are also grateful to the institutions that have shared with us images from their<br />

exhibitions and collections: in London, the National Portrait Gallery, Tate Modern,<br />

Tate Britain and the Barbican Art Gallery; in Paris, the Fondation Louis Vuitton;<br />

in Dresden, the Gemaldegalerie Alte Meister; and in Florence, Casa Buonarroti<br />

Museum and Palazzo Strozzi.<br />

Grazie mille for the ongoing support of our partner Christian Levett and our<br />

friends and collaborators at Bloomberg Philanthropies, the British Institute of<br />

Florence, the Casa Buonarroti Museum and Foundation, Il Palmerino Cultural<br />

Association, The Florentine and the Museo Galileo.<br />

To the many visitors of the on-site restoration of Artemisia Gentileschi’s Allegory<br />

of Inclination at Casa Buonarroti, thank you for your enthusiastic (and sometimes<br />

deeply emotional) response to this project.<br />

Finally, we extend a very personal and fond acknowledgment to Monica Martin<br />

who describes Restoration Conversations as “the most beautiful magazine I have<br />

ever seen” and who continues to support our work as she begins her 100th year.<br />

4 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong>

CONTENTS: SPRING/SUMMER 20<strong>23</strong><br />

PORTRAITS AND DIALOGUES<br />

Self-representation and ‘conversations’ on canvas<br />

6 London’s National Portrait Gallery Re-opens<br />

14 Work in Progress: A Monumental Women’s Mural<br />

20 Friends and Strangers: Alice Neel and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye<br />

28 The Paradox of Rosalba Carriera<br />

36 Before the selfie: Women’s self portraits<br />

42 Reflections on the Monet — Mitchell Exhibition<br />

PAGES OF HISTORY<br />

Legacies, letters, archives and books<br />

48 Murders and Marriages: Catherine de‘ Medici<br />

54 A Letter to Madame Christine, from Galileo<br />

60 Hidden in Plain Sight: Adrienne Fidelin<br />

68 A Moveable Feast: Abstractionists, the Women<br />

74 Three Women: Many Moons<br />

80 The Other Side<br />

IN FOCUS TODAY, IN FLORENCE<br />

Follow Calliope Arts at every step<br />

84 ‘Inclination’ Update: Structure Changes<br />

89 Artemisia’s Palette<br />

94 Palace Women: Oltrano and Beyond<br />

98 Calliope Arts News in Brief<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong> • Restoration Conversations 5

Above: Installation shot of Vanessa Bell’s Portrait by Duncan Grant going back into the National Portrait Gallery. Photo: David Parry, National Portrait Gallery<br />

6 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong>

From Courtesans to<br />

Conceptual Artists<br />

Women in the frame at London’s re-vamped<br />

National Portrait Gallery<br />

AAfter a three-year renovation, London’s National Portrait<br />

Gallery will re-open on June 22nd, 20<strong>23</strong>. NPG’s Chanel Curator<br />

for the Collection, Dr Flavia Frigeri, spoke to Margie MacKinnon<br />

about the Reframing Narratives: Women in Portraiture project<br />

(supported by the CHANEL Culture Fund), which aims to<br />

highlight the often overlooked stories of individual women who<br />

have shaped British history and culture.<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong> • Restoration Conversations 7

Above: Dr. Flavia Frigeri, Chanel Curator for the Collection<br />

Photo: Isabelle Young<br />

At the start of this project, what was<br />

the balance between male and female<br />

representation at the NPG?<br />

“There were approximately 50,000 men in the<br />

collection and about 16,000 women,” Frigeri<br />

points out, “so there was a big disparity. The NPG<br />

is a history museum which means that the sitter<br />

always comes first: who is depicted in the portrait<br />

is always more important than who painted the<br />

portrait. Portraiture is something that is its own<br />

micro-environment within the macro sphere of<br />

art. Historically, the people who would have their<br />

portrait painted were people of means, the upper<br />

class. Even the women who were depicted by<br />

male artists were often from a very specific class<br />

– so it is already creating a tiered system.<br />

The goal of enhancing the visibility of women<br />

as part of the re-organisation of the NPG,” says<br />

Frigeri, “is very much a collective endeavour.<br />

I have been working with a team of curators,<br />

organised by historical period, and they were<br />

already thinking about the place of women<br />

within the re-hang. The way visibility is going<br />

to manifest itself is that, obviously, you’re going<br />

to have some of the ‘greatest hits’ on the walls.<br />

You can expect to see Elizabeth I, you can expect<br />

to see Vanessa Bell and Virginia Woolf. But, then,<br />

what we have tried to do as a team has been to<br />

weave in stories of women that are perhaps more<br />

unexpected. The difficulty is that sometimes we<br />

don’t necessarily have the best portraits for the<br />

best stories.<br />

“We are also thinking about how to educate<br />

people in terms of how to read portraits because,<br />

naturally – and this is something I also fall prey<br />

to – you walk into a room, you see a portrait in<br />

a gilded frame and immediately you think that is<br />

8 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong>

the most important person in the room. Whereas<br />

it is more of a struggle to see a small photograph,<br />

with no gilding, as being in the same league. So<br />

[when the image isn’t enough] we will be using<br />

other kinds of media that will help to tell the<br />

story in a more nuanced way.”<br />

Apart from royalty, who was the first woman<br />

in the collection?<br />

“The first woman in the collection,” Frigeri<br />

notes, “was Elizabeth Hamilton, a courtesan … I<br />

recently gave a talk in Berlin about this and I was<br />

explaining how the first man in the collection<br />

was Shakespeare. Then I had to admit to the fact<br />

that the first woman was, yes … which doesn’t take<br />

away from her as a woman. The founding fathers<br />

of the NPG were very specific when they wrote<br />

their constitution and I should stress fathers –<br />

no woman was involved. A portrait had to depict<br />

someone of worthiness, achievement, recognition<br />

and fame … and for decades women didn’t really<br />

fit any of those categories, unless they were royal<br />

or attached to the royals somehow.”<br />

When did the collection start opening up?<br />

“Until the 1960’s you could only show the portrait<br />

of someone who had been dead for at least ten<br />

years. The idea was that you needed ten years<br />

to be sure that the achievements of that person<br />

were lasting. But this rule was lifted in the 1960’s<br />

as the need to include more contemporary artists<br />

became apparent. So that is when the collection<br />

started becoming a bit more eclectic in range. In<br />

the 1970’s the trend was to collect mostly women<br />

in the arts, so we have dancers, we have writers, a<br />

lot of actors … there weren’t that many women in<br />

science – that’s a big gap.”<br />

Above: Elizabeth Hamilton, Countess de Gramont by John Giles Eccardt,<br />

after Sir Peter Lely (18th century, based on a work of c. 1663)<br />

© National Portrait Gallery, London<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong> • Restoration Conversations 9

Is it possible there were fewer women<br />

scientists because their male colleagues<br />

were taking credit for their work?<br />

“Yes,” Frigeri agrees, “there was some of that and it’s<br />

something we have been looking into. We recently<br />

acquired a portrait of Anne McLaren, one of the<br />

women who was instrumental in developing the<br />

science necessary for IVF. She was working with<br />

her husband at University College London for a<br />

long time and was less known than him. McLaren<br />

is an example of someone that we have recently<br />

been able to bring into the collection. For me, this<br />

is important because it is a way to push against<br />

the grain of the founding fathers and say, look,<br />

these are women worthy of that recognition.”<br />

Did the advent of photography have an<br />

impact on the collection?<br />

“It made a huge difference,” says Frigeri, “because,<br />

in a way, photography is the most emancipatory<br />

medium of them all. Photography allowed<br />

women to establish their own portrait studios.<br />

So, even if they had the ambition to go on and<br />

do more avant-garde photography, they were<br />

able to support themselves financially through<br />

their studio. The affordability of photography<br />

drove up the demand for portraits, so it became a<br />

sustainable business.<br />

We have great examples of women like Rita<br />

Martin and Lallie Charles establishing a portrait<br />

studio called The Look which was around the<br />

corner from Regent’s Park and was incredibly<br />

successful. Alice Hughes had a studio on Gower<br />

Street up in Bloomsbury and, at one point, she<br />

employed 50 women assistants. We have many<br />

of these women photographers in the collection,<br />

so it is a very strong area, dating from the 1900’s.<br />

It all began with Julia Margaret Cameron doing<br />

in photography what the Pre-Raphaelites were<br />

doing in painting.”<br />

Another aspect of the project focusses on the<br />

acquisition of new works by women. What<br />

were your guiding principles in choosing<br />

these works?<br />

“I thought about how I could make acquisitions<br />

that were relevant enough and substantial enough<br />

in the long term without ‘breaking the bank’. What<br />

Above: Dame Anne McLaren, photographer unknown, gelatin silver print, 1958, National Portrait Gallery, London<br />

10 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong>

Above: Ace (retrieved) from ‘The Photomat Portrait Series’ by Susan Hiller, 1972-3<br />

© The Estate of Susan Hiller. Purchased with kind support from the CHANEL Culture Fund for ‘Reframing Narratives: Women in Portraiture’, 2022<br />

were the things that the portrait gallery wouldn’t<br />

usually collect because they wouldn’t necessarily<br />

be seen as priorities? There was a focus on selfportraiture,<br />

created by artists who were working<br />

with a very feminist conceptual slant. These are<br />

self-portraits, but they are doing lots of other<br />

things on the side.<br />

“In Susan Hiller’s work she was taking her selfportrait<br />

using different photobooth machines<br />

around London and then collecting them. The idea<br />

is – she was taking agency away from herself and<br />

lending it to the machine, and each photobooth<br />

produces a very different kind of image. There is<br />

this piecing together of mechanically produced<br />

images, but also the suggestion that no person<br />

is a single image. We are all made up of lots of<br />

different layers. So, there is a conceptual element<br />

to this work. If you were to see it at the Tate<br />

you would probably read it with very conceptual<br />

language, but here you’re just looking at a portrait<br />

that is not a traditional portrait.<br />

“Rose Finn-Kelcey’s self-portrait is similar. You<br />

cannot see it from this image but there is a cut<br />

in the middle of the image because this was the<br />

pre-Adobe days and she had to glue and stitch<br />

together two images. This is her seated at Marble<br />

Arch at Speaker’s Corner. In this case, she is very<br />

much thinking about the fact that women have<br />

traditionally been left out of all the places where<br />

public speaking happens. She is reclaiming this<br />

space for women in terms of public speaking,<br />

but she is also thinking that the absence of that<br />

space has meant that women had a lot more<br />

existential, private speaking happening within<br />

themselves – so it’s a conversation, or internal<br />

dialogue, between the two selves.<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong> • Restoration Conversations 11

Above: Självporträtt, Åkersberga by Everlyn Nicodemus, 1982<br />

© the artist, courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery<br />

Purchased with kind support from the CHANEL Culture Fund<br />

for ‘Reframing Narratives: Women in Portraiture’, 2022<br />

“I was able to acquire this beautiful small<br />

portrait of Celia Paul,” Frigeri continues, “and then<br />

this wonderful portrait by Everlyn Nicodemus<br />

called Självporträtt, Åkersberga. This is a selfportrait<br />

she made in 1982 when she was living in<br />

Sweden and had recently given birth to a young<br />

daughter and was struggling with her marriage.<br />

She paints all of these different faces to suggest<br />

the many faces she needs to wear at once –<br />

mother, artist, lover and so forth. This is actually<br />

the first self-portrait by a black artist to enter the<br />

collection.<br />

“And then there is Maeve Gilmore, an exceptional<br />

artist. I love the intensity of her expression and I<br />

love that she is holding with such assertiveness<br />

this piece of charcoal, and just looks at you. And<br />

looking at you really says, this is my place as an<br />

artist. These are some of the works that I have<br />

been bringing into the collection with a focus<br />

on self-portraiture. They are small in number in<br />

terms of acquisitions but they are quite radical in<br />

starting the discourse and taking it in different<br />

directions.”<br />

When the National Portrait Gallery reopens,<br />

more than 200 portraits of women made after<br />

1900 and over 100 portraits created during that<br />

time by women will be exhibited. Adding to that<br />

number will be the newly commissioned Work in<br />

Progress, a group portrait of 133 notable women<br />

created by Jann Haworth and Liberty Blake. (See<br />

feature on p. 14). RC<br />

12 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong>

Above: Preparatory study for Divided Self by Rose Finn-Kelcey, 1974<br />

© The Estate of Rose Finn-Kelcey. Courtesy of Kate MacGarry Gallery<br />

Purchased with kind support from the CHANEL Culture Fund<br />

for ‘Reframing Narratives: Women in Portraiture’, 2022<br />

Left: Portrait, Eyes Lowered by Celia Paul, 2019<br />

© Celia Paul. Courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro<br />

Purchased with kind support from the CHANEL Culture Fund<br />

for ‘Reframing Narratives: Women in Portraiture’, 2022<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong> • Restoration Conversations 13

Work in Progress<br />

The origins of the NPG’s monumental new mural<br />

14 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong>

In 1967, Jann Haworth and her then husband Peter Blake designed the cover for<br />

the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper album, which features the band surrounded by a cast of<br />

characters, from Bob Dylan and Marilyn Monroe to Albert Einstein and Shirley<br />

Temple. Revisiting the cover some years later, Haworth realised it included only<br />

twelve women and, of those, half were fictional. She decided to create a new<br />

women-centred mural featuring women from all different fields who had been<br />

catalysts for change. By the time she found sponsorship for this project it was<br />

2016. In the run-up to the American election, when it seemed, in Haworth’s view,<br />

all but inevitable that Hillary Clinton would win, it was, in the artist’s words, “a<br />

Ipotent moment” to celebrate all that women had achieved.<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong> • Restoration Conversations 15

Liberty Blake. Photograph courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery<br />

Jann Haworth. Photograph courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery<br />

Of course, the election did not play out as she<br />

anticipated, but Haworth and her daughter,<br />

Liberty Blake, started work on the mural, which<br />

has now grown from its initial 28 feet to 60 feet<br />

in width. Made up of over 300 portraits, created<br />

by 250 participants, the mural was designed so<br />

that it can be transported from place to place<br />

and continually expanded – in other words, it is a<br />

Work in Progress.<br />

Meanwhile in London, in a break between Covid<br />

lockdowns, the National Portrait Gallery’s Flavia<br />

Frigeri “snuck out” of her Bayswater flat to visit a<br />

gallery in Mayfair where Jann Haworth was having<br />

a show. “It triggered my memory because I had<br />

seen the original Work in Progress a few years<br />

before and I thought, this could be a great thing<br />

to do in communities around the country. We<br />

commissioned Jann and Liberty to do a new Work<br />

in Progress for the NPG, celebrating 133 women. It<br />

would be a pantheon of women from Elizabeth I all<br />

the way to Vivienne Westwood and Malala.<br />

“We worked with partner institutions across the<br />

country and each institution hosted a workshop.<br />

The idea was that every person who participated<br />

in the workshops would choose an image and<br />

then make a stencilled portrait. Artists would tune<br />

in via Zoom and they would guide the participants<br />

in cutting out their images and stencilling them<br />

with colours. The stencilled portraits were sent to<br />

Jann and Liberty in Utah where they spent three<br />

months mounting them all on seven giant panels.<br />

“When you come into the National Portrait<br />

Gallery, there will be a gallery about historymakers<br />

and one whole wall will be our mural.<br />

This will set the tone for the way we want you<br />

to think about women, the way we want you to<br />

see women and the way we want to put women<br />

at the forefront. And, if you look at the top of the<br />

seventh panel, you will see an empty silhouette.<br />

Because this is a ‘work in progress’, we don’t want<br />

to suggest that this is the complete pantheon. It<br />

is a pantheon that you can keep adding to, and<br />

you can imagine whoever you want in that blank<br />

space. We are also working closely with the artists<br />

on a series of resources that we’re going to make<br />

available to schools and families so that people<br />

can go home and make their own mural. “These<br />

trailblazing women of the past,” says Frigeri, “are<br />

role models for the future.” RC<br />

Work in Progress by Jann Haworth and Liberty<br />

Blake, 2021-2. Acrylic on paper collaged on panels.<br />

Commissioned by Trustees with kind support<br />

from the CHANEL Culture Fund, 2021.<br />

16 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong>

PANEL 1<br />

Organic farmer Eve Balfour, businesswoman Anita Roddick, writer Vera Brittain, pianist Shulamith Shafir, artist and<br />

writer Mary Delany, Hospice Movement founder Cicely Saunders, peace activist Mairead Corrigan Maguire, poet<br />

and writer Sylvia Plath, sculptor Alison Wilding, writer and illustrator Beatrix Potter, surgeon Louisa Aldrich Blake,<br />

photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, classicist Mary Beard, novelists Jane Austin, Virginia Woolf and more…<br />

PANEL 2<br />

Actor and comedian Dawn French, writer and feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, nurse and army medical service reformer<br />

Florence Nightingale, Queen Elizabeth I, political activist Sylvia Pankhurst, activist for women’s rights Ishbel Hamilton-<br />

Gordon, actress Vivien Leigh, chemist and astronaut Helen Sharman, fossil collector Mary Anning, fashion model<br />

Twiggy, educator for race equality Jocelyn Barrow and more…<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong> • Restoration Conversations 17

PANEL 3<br />

Mental illness physician Helen Boyle, printer and writer Eleanor James, aeronautical engineer and aviator Lilian Bland, traveller<br />

and botanical artist Marianne North, pianist Harriet Cohen, aviator Amy Johnson, comedian Gina Yashere, athlete Rachel Atherton,<br />

photographer Yevonde, novelist Olivia Manning, painter Bridget Riley, social reformer Octavia Hill, archaeologist Gertrude Bell and<br />

fashion designer Mary Quant and more…<br />

PANEL 4<br />

Poet laureate Carol Ann Duffy, cartoonist Kate Charlesworth, artist Sonia Boyce, playwright Caryl Churchill, children’s writer Eva<br />

Ibbotson, actress Emma Thompson, Alice Liddell, inspiration for Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, nurse Elizabeth Anionwu, space<br />

scientist Maggie Aderin-Pocock, chemist and crystallographer Rosalind Franklin, film director Gurinder Chadha, writer Agatha<br />

Christie, poet Christina Rossetti and more…<br />

PANEL 5<br />

Sprinter Ethel Scott, historian Joan Thirsk, abolitionist Ellen Craft, Minnie Lansbury, writer Zadie Smith, Paralympic athlete and<br />

broadcaster Tanni Grey-Thompson, designer and painter E.Q. Nicholson, portrait painter Mary Beale, co-founder of Girl Guides<br />

Agnes Baden-Powell, writer J.K Rowling, Boxer and Olympian Nicola Adams, human rights lawyer Shami Chakrabarti, activist and<br />

writer Mala Sen, tennis player Charlotte Cooper and more…<br />

18 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong>

PANEL 6<br />

Sculptor Barbara Hepworth, suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst, artist and curator Lubaina Himid, singer-songwriter Amy<br />

Winehouse, painter Vanessa Bell, suffragette Sophia Duleep Singh, physicist and radio astronomer Jocelyn Bell Burnell, comedian<br />

and disability rights activist Barbara Lisicki, ballet dancer Margot Fonteyn, actor Olivia Colman, children’s poet and writer Grace<br />

Nichols, model for Pre-Raphaelite artists Fanny Eaton and more…<br />

PANEL 7<br />

Actress Julie Andrews, illustrator Jessie M. King, journalist and historian Jan Morris, painter Joan Eardley, nurse and business woman<br />

Mary Seacole, artistic director and champion of disability arts Jenny Sealey, singer-songwriter Kate Bush, artist Eileen Agar, social<br />

reformer and theatre manager Emma Cons, artist Gillian Wearing, journalist Kate Adie, artist Paula Rego, electrical engineer and<br />

inventor Hertha Ayrton, cellist Jacqueline du Prè and more…<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong> • Restoration Conversations 19

Friends and Strangers<br />

Portraits by Alice Neel<br />

and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye<br />

Two London exhibitions, one just ended, the<br />

other ongoing, illustrate the continuing<br />

allure of portrait painting in Western art<br />

and its possibilities for radical re-invention.<br />

Tate Britain recently hosted Fly in League with<br />

the Night, a show of some 80 paintings and<br />

works on paper created by London-born artist<br />

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. At the Barbican, works<br />

from the American painter Alice Neel’s 60-year<br />

career are currently on display under the title<br />

Hot off the Griddle.<br />

In their own way, each of these artists brought,<br />

or brings, a revolutionary approach to portrait<br />

painting. Neel explained that one of her reasons<br />

for painting “was to catch life as it goes by, right<br />

hot off the griddle”. She welcomed sitters into<br />

her home, chatted away to them, and invited<br />

them to share their own stories. She painted<br />

figuratively when the prevailing trend favoured<br />

Abstract Expressionism. While the AbEx artists<br />

created works that reflected their reactions to a<br />

period of tumultuous change, Neel hid her own<br />

struggles behind a smile and brought out the<br />

feelings of her subjects. “I paint to try to reveal<br />

the tragedy and joy of life,” she said.<br />

Despite appearances to the contrary, Yiadom-<br />

Boakye’s paintings are not portraiture in the<br />

traditional sense. The subjects are not real<br />

people, but creations of the artist’s imagination,<br />

based on a combination of memory, family<br />

snapshots, images from magazines collected in<br />

scrapbooks and details of paintings. A writer, as<br />

well as an artist, Yiadom-Boakye says, “I write<br />

about the things I can’t paint and paint the things<br />

I can’t write about …”. These fictional, nameless<br />

strangers seem every bit as full of humanity as<br />

Neel’s living, breathing sitters.<br />

ALICE NEEL<br />

Born at the turn of the last century, Alice Neel<br />

grew up in a small town in Pennsylvania. Her<br />

parents were not artists and she had little<br />

exposure to culture, but, somehow, she knew<br />

from a young age that she would become an<br />

artist. In 1921, she began her art studies at the<br />

Philadelphia School of Design for Women (also<br />

known, because of its conservative reputation, as<br />

the ‘Philadelphia School for Designing Women’).<br />

She met Cuban artist Carlos Enriquez Gomez at<br />

a summer art course in 1924, and they married<br />

the following year. Their first child, a daughter<br />

named Santillana, tragically died just before her<br />

first birthday. By then the couple had moved<br />

to New York where Neel soon had a second<br />

daughter, Isabetta. Husband and wife continued<br />

to paint but struggled to support themselves,<br />

moving to ever cheaper accommodation. In<br />

May of 1930, Gomez took Isabetta with him to<br />

Havana, telling Neel he would send money back<br />

to enable her to join them. The money never<br />

materialised, and Neel only saw her daughter a<br />

handful of times after that.<br />

20 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong>

Above, left: Alice Neel. 1977. Mary D. Garrard.<br />

© The Estate of Alice Neel<br />

Courtesy of The Estate of Alice Neel<br />

Above, right: Alice Neel, 1960. Frank O’Hara.<br />

© The Estate of Alice Neel<br />

Courtesy of The Estate of Alice Neel<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong> • Restoration Conversations 21

This trauma seems to have informed much<br />

of Neel’s work and underscores the difficulty<br />

experienced by so many female painters of<br />

combining life as an artist with motherhood.<br />

Following the stock market crash and during<br />

the period of the Great Depression in the 1930’s,<br />

life was punishingly hard. Countless artists,<br />

including Neel, were saved from starvation by<br />

the government-sponsored Federal Art Project<br />

which paid unemployed artists a small salary in<br />

exchange for producing works of art to decorate<br />

public buildings. The deprivation of these times<br />

produced in Neel a “desire to bear witness to<br />

the hardships of life as experienced by most<br />

Americans” in that decade. Neel’s salary from the<br />

Art Project allowed her to secure an apartment<br />

which she also used as studio space. At the same<br />

time, she joined the Communist Party, an event<br />

that would later lead the FBI to open a file on her<br />

and even show up at her door to investigate her,<br />

having identified Neel as a ‘romantic, Bohemian<br />

type Communist’. Characteristically, she was<br />

sanguine about the encounter and asked if<br />

the agents would be interested in sitting for a<br />

painting. (They declined.)<br />

In the 1940’s, when up-and-coming artists such<br />

as Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning and Grace<br />

Hartigan were moving downtown to convert<br />

lofts into studios and creating pioneering works<br />

of Abstract Expressionism, Neel moved north to<br />

Spanish Harlem and persisted with figurative<br />

painting, largely dismissed as an artist out of step<br />

with the times. But it was there that she met the<br />

subjects for her works, however unfashionable<br />

they may have been. She was, she said, “not<br />

against abstraction, but against saying that Man<br />

himself has no importance.”<br />

Neel’s T.B. Harlem (1940) is a comment on<br />

the epidemic of TB that had broken out in<br />

overcrowded areas of New York. It depicts an<br />

unnamed young man who is recovering in a<br />

tuberculosis hospital. Before effective antibiotics<br />

were widely available, TB treatment was brutal.<br />

Left, top: Alice Neel, 1940. T.B. Harlem. © The Estate of Alice Neel<br />

Courtesy of The Estate of Alice Neel<br />

Left: Alice Neel, 1943. The Spanish Family. © The Estate of Alice<br />

Neel. Courtesy of The Estate of Alice Neel<br />

22 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong>

The bandage on the left of the man’s chest is<br />

from a thoracoplasty, a surgical procedure which<br />

involved removing several ribs and collapsing<br />

the affected lung. The painting is simple, with a<br />

muted colour palette, making the blood seeping<br />

out from under the bandage more evident. The<br />

plain background draws the viewer towards the<br />

man’s face, which registers a resigned stoicism.<br />

He is just one man among many suffering a<br />

similar fate.<br />

The loss of her mother, in 1954 at the age of<br />

86, sent Neel into a deep depression that lasted<br />

over the next few years and, in 1958, she began<br />

to see a therapist for the first time. Neel credits<br />

her therapist with encouraging her to be more<br />

ambitious with her work and “getting it into the<br />

world”. She summoned the courage to approach<br />

the poet Frank O’Hara, then a curator at the<br />

Museum of Modern Art, to sit for her. The picture<br />

appeared in ARTnews alongside an enthusiastic<br />

review describing how “her paintings cast a spell’.<br />

This marked a turning point in Neel’s career,<br />

and she began to paint more recognisable figures,<br />

including Andy Warhol. His portrait reveals Neel’s<br />

remarkable ability to get her sitters to trust<br />

her, allowing her to paint them with all their<br />

vulnerabilities. In Warhol’s case, this included<br />

showing the scars that had resulted from a vicious<br />

assault by Valerie Solanas, a former member of<br />

Warhol’s Factory entourage.<br />

Other well-known faces amongst Neel’s sitters<br />

included feminists Kate Millet (whose portrait<br />

Neel was commissioned to paint for the cover<br />

of Time magazine), Mary D. Garrard (known<br />

for her ground-breaking studies of Artemisia<br />

Gentileschi) and Linda Nochlin (author of ‘Why<br />

are there no great women artists?’) Neel’s ability<br />

to disarm seems not to have worked on Garrard,<br />

who looks particularly ill-at-ease in the familiar<br />

blue and white striped chair. Still wearing her<br />

hat, coat and scarf, she looks directly at the artist,<br />

as if daring her to reveal anything beyond her<br />

inscrutable surface. Nochlin is painted with her<br />

young daughter, Daisy. Apparently, Neel was keen<br />

to portray Nochlin as both an intellectual and a<br />

mother. She told the eminent art historian, “you<br />

don’t look anxious, but you are anxious”. Perhaps<br />

she was projecting her own maternal anxiety<br />

onto her sitter.<br />

Neel would have to wait until 1974, when she<br />

was 74 years old, to have the first retrospective<br />

exhibition of her work, which was held at the<br />

Whitney Museum of Art in New York. The<br />

Barbican art director, Will Gompertz, describes<br />

Neel’s portraits as “the very opposite of an<br />

Instagram image … You can’t photograph what<br />

Alice Neel painted. Her ability to simultaneously<br />

show a sitter’s conscious and unconscious state,<br />

and imperceptibly morph the two, was a magic<br />

trick of sorts … She didn’t simply paint faces, she<br />

revealed souls.”<br />

Right: Alice Neel, 1929. Alice Neel at the age of 29.<br />

© The Estate of Alice Neel<br />

Courtesy of The Estate of Alice Neel<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong> • Restoration Conversations <strong>23</strong>

Above: Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, 2011. Condor and the Mole, Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London. © Courtesy of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye<br />

Right: Installation shot at the Tate, Madeline Buddo<br />

24 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong>

LYNETTE YIADOM-BOAKYE<br />

British artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, born in<br />

London in 1977 to Ghanaian parents, is one<br />

of a number of artists who have transformed<br />

portraiture over the last decade. Her recent<br />

exhibition at London’s venerable Tate Britain<br />

follows earlier shows in Munich, Basel and New<br />

York, among others. Some of her works are also<br />

featured in the Reaching for the Stars exhibition<br />

at Florence’s Palazzo Strozzi.<br />

Yiadom-Boakye’s works, while recognisably<br />

part of the continuum of European portraiture,<br />

are innovative in their subject-matter, style and<br />

atmosphere. Most notably, rather than working<br />

with live models, Yiadom-Boakye draws from her<br />

experience as a writer to create her own fictional<br />

subjects. In doing so, she turns the aphorism that<br />

‘portraits are the one genre of art in which the<br />

subject is more important than the artist’ on its<br />

head. “Over time,” she says, “I realised I needed<br />

to think less about the subject and more about<br />

the painting. So I began to think seriously about<br />

colour, light and composition.”<br />

The artist also subtly subverts traditional<br />

portraiture in rejecting the genre’s conventional<br />

function of not only creating a likeness, but<br />

conveying the sitter’s class and status, usually by<br />

including symbolic objects denoting education,<br />

wealth and power – or their opposites. Yiadom-<br />

Boakye’s subjects are difficult to place within a<br />

social group or culture or a specific place or time<br />

period. This timeless quality is deliberate, as it<br />

requires the viewer to engage with the subject<br />

and to use their curiosity to project their own<br />

interpretations and imagine the story behind the<br />

painting.<br />

The canvases depict young men and women,<br />

by themselves or in small groups, many larger<br />

than life-sized. The scale adds to the quality of<br />

the work. Very broadly and confidently painted,<br />

the compositions are intriguing, drawing the<br />

viewer in. “Her painting of dark skin in shadow,<br />

circumambient gloaming or night is superb,” says<br />

critic Laura Cumming. “She makes a strong virtue<br />

of contrapposto, chiaroscuro and the sumptuous<br />

sinking of oil into linen.”<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong> • Restoration Conversations 25

Above, left: Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, 2018<br />

To Improvise a Mountain. Private Collection<br />

© Courtesy of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye<br />

Photo: Marcus Leith<br />

Above, right: Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, 2014<br />

Citrine by the Ounce. Private Collection<br />

© Courtesy of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye<br />

A young male dancer stretches at the barre while<br />

his friends engage in conversation nearby, two girls<br />

play in the rockpools along a beach, absorbed in their<br />

activity and each other, a woman with an elaborate<br />

frilly collar stares out unblinkingly from the canvas<br />

– is she willing you to come closer or daring you to<br />

stay away? In Penny for Them (2014), another woman<br />

resting her chin in her hand is lost in thought. In<br />

each case, the audience may be reminded of a<br />

painting they have seen or a memory from their own<br />

life. It is up to us to give these characters their story.<br />

Tate Britain is home to a collection of British<br />

artworks dating back to 1545. Seeing a whole<br />

gallery there filled with her work is a powerful<br />

experience. “That Yiadom-Boakye’s subjects happen<br />

to be Black, reflecting her own identity, reminds us<br />

of the overwhelming whiteness of the tradition of<br />

[European portraiture],” notes the museum’s Director,<br />

Alex Farquharson. Yiadom-Boakye points out that,<br />

“Blackness has never been other to me. Therefore,<br />

I’ve never felt the need to explain its presence in the<br />

26 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong>

work anymore than I’ve felt the need to explain my<br />

presence in the world, however often I’m asked.”<br />

Despite their many differences – in background,<br />

style and subject matter – Neel and Yiadom-Boakye<br />

have both succeeded in ‘bringing out whatever their<br />

subjects have in common with the rest of humanity’,<br />

the goal that art historian Erwin Panofsky identified as<br />

the central desire of Renaissance artists. Neel talked<br />

to her subjects as if they were old friends, allowing<br />

them to relax and drop their guard so that she could<br />

catch something of their inner nature. Yiadom-<br />

Boakye’s fictional sitters are enigmatic ‘strangers’ on<br />

whom we can project our own thoughts and desires.<br />

By thinking about what we see in them, we learn<br />

something about ourselves. RC<br />

Above, left: Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, 2020<br />

Razorbill, Tate<br />

© Courtesy of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye<br />

Above, right: Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, 2017<br />

In Lieu of Keen Virtue<br />

© Courtesy of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Corvi-Mora, London<br />

and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York<br />

Alice Neel: Hot off the Griddle is at London’s Barbican<br />

Art Gallery until 21 May 20<strong>23</strong><br />

Reaching for the Stars is at Palazzo Strozzi, Florence,<br />

until 18 June 20<strong>23</strong><br />

<strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong> • Restoration Conversations 27

Above: Rosalba Carriera, A Black-haired Lady with a Thin Gold Necklace. © Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Photo: Elke Estel/ Hans-Peter Klut<br />

28 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong>

Artemisia’s<br />

‘A Rare Talent’<br />

The paradox of Rosalba Carriera<br />

I<br />

have not come across another artist that<br />

has been so completely neglected after so<br />

much success.” Angela Oberer is talking<br />

about Venetian painter Rosalba Carriera (1673-<br />

1757), a celebrated artist in her day and one<br />

of the most successful women artists of any<br />

era. Known as the ‘first painter of Europe’, her<br />

pastels were highly admired by 18th-century<br />

European collectors, and prominent foreign<br />

visitors to Venice and Grand Tourists were<br />

eager to sit for portraits by her. An astute<br />

entrepreneur, she set new trends in style and<br />

technique, and was admitted to membership<br />

of three art academies.<br />

For one hundred years after her death,<br />

Carriera continued to enjoy recognition and<br />

influence as an accomplished artist. And<br />

then, as dramatically as it had risen, her star<br />

plummeted, and she lapsed into relative<br />

obscurity. Carriera’s story presents us with a<br />

paradox: how did she achieve her remarkable<br />

professional and financial success at a time<br />

when so few women were able to make a living<br />

at their art, and how did she subsequently<br />

come to be all but forgotten?<br />

On the 350th anniversary of Carriera’s birth<br />

and the eve of a major exhibition of her work<br />

in Dresden, Angela Oberer, a professor and<br />

art historian who has authored two books on<br />

“<br />

Carriera, gave a talk at the British Institute of<br />

Florence about her interest in a painter who<br />

was highly sought-after as a miniaturist and<br />

portrait painter, but who subsequently fell out<br />

of fashion.<br />

Oberer has been researching Carriera<br />

for over ten years. “I had a special interest<br />

in sisters,” she explains. “I have an older<br />

sister, and I just wanted to understand this<br />

funny relationship … so I was looking for a<br />

painter with one or more sisters. And then I<br />

stumbled across that self-portrait of Carriera<br />

with her sister Giovanna.” (See feature on<br />

p .36). A fortuitous match between researcher<br />

and subject seemed all but inevitable when<br />

Oberer tracked down two volumes at the<br />

Biblioteca Laurenziana in Florence containing<br />

transcriptions of Carriera’s correspondence<br />

and diaries – a cache of documents comprising<br />

over 800 pages. In other words, a scholar’s<br />

dream come true. Combing through this<br />

archive over several years has enabled Oberer<br />

to understand how Carriera achieved her<br />

renown, despite all the usual impediments to<br />

be overcome as a female artist.<br />

Carriera’s early life and training remain<br />

something of a mystery. Unusually for female<br />

artists of her era, she did not come from an<br />

artistic family. Although various scholars have<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong> • Restoration Conversations 29

Left: Rosalba Carriera, 1730/31<br />

Self-portrait as Winter<br />

Photo: Katrin Jacob<br />

& Wolfgang Kreische<br />

Right, clockwise from top left:<br />

Rosalba Carriera, A Young<br />

Gentleman in a Puffy Blue<br />

Coat<br />

Photo: Elke Estel<br />

& Hans-Peter Klut<br />

Rosalba Carriera, c. 1725/30<br />

A Lady with a Parrot on her<br />

Right Hand (Allegory of<br />

Eloquence)<br />

Photo: Marina Langner<br />

& Wolfgang Kreische<br />

Rosalba Carriera, c. 1735/40<br />

A Venetian from the House of<br />

Barbarigo (Caterina Sagredo<br />

Barbarigo)<br />

Photo: Marina Langner<br />

& Wolfgang Kreische<br />

Rosalba Carriera, 1730<br />

Archduchess Maria Theresia<br />

of Habsburg<br />

Photo: Elke Estel<br />

& Hans-Peter Klut<br />

All images © Gemäldegalerie<br />

Alte Meister, Staatliche<br />

Kunstsammlungen Dresden<br />

tried to identify who her first teachers might<br />

have been, Oberer notes that, “So far, we don’t<br />

have any documents to state definitively who<br />

she studied with, if anyone. Maybe she was<br />

mainly self-taught?”<br />

Carriera began her career helping her<br />

mother with her embroidery and lace-making<br />

business. When snuff-taking became popular<br />

during the second half of the 17th century,<br />

Carriera took advantage of the opportunity<br />

to begin painting miniatures for the lids of<br />

snuffboxes. She not only had a particular talent<br />

for working at this scale, but she benefitted<br />

from a dearth of miniaturists in her home city<br />

of Venice, where her male contemporaries were<br />

busy competing for lucrative commissions for<br />

altarpieces, city views and fresco painting.<br />

Showing further initiative, Carriera became<br />

one of the first painters to use ivory instead<br />

of vellum as a support for miniatures. “She<br />

got a name for her miniatures very quickly<br />

and, one curious and fun fact is that some of<br />

30 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong>

<strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong> • Restoration Conversations 31

Rosalba Carriera, Female Study Head in Grey-purple Coat<br />

© Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden<br />

Photo: Elke Estel & Hans-Peter Klut<br />

the letters mention that forgeries of her work<br />

were already being offered for sale in Venice,”<br />

Oberer observes.<br />

Carriera was also quick to spot an<br />

opportunity in Venice’s growing tourist trade.<br />

The city was an obligatory stop on the Grand<br />

Tour undertaken by young sons and daughters<br />

of the nobility, as well a favourite destination<br />

for other prominent visitors and diplomats.<br />

Carriera used her networking skills to develop<br />

a market for portraits. Once again, her genius<br />

for innovation came to the fore as she began<br />

producing these portraits in pastel, a medium<br />

that had, until then, been used mainly for<br />

preparatory drawings.<br />

Carriera’s popularity helped to encourage<br />

the production of high-quality pastel sticks<br />

in varied textures and in a greater range of<br />

colours than had previously been available.<br />

Pastel portraits came to be seen as equivalent<br />

in quality to oil portraits; they offered other<br />

advantages as well: the materials were<br />

cheaper and easier to transport, portraits could<br />

be executed quickly as there was no drying<br />

time, and fewer sittings were required, a boon<br />

to both artist and subject. On the other hand,<br />

pastel is a notoriously fragile medium, subject<br />

to fading when exposed to light. Unlike oils,<br />

pastels’ vulnerability to fading is increased<br />

because they are not protected by a varnish,<br />

nor are the powdery components surrounded<br />

by a resin. The works had to be covered with<br />

glass, but this was not available in a large<br />

format. “Carriera’s portraits have a kind of<br />

standard size”, notes Oberer. “They didn’t get<br />

much higher than around 60 centimetres.”<br />

Great care was required when shipping them<br />

to their owners. “Carriera had a beautiful way<br />

of sending off her portraits with a little token,<br />

tucked between the painting’s wooden support<br />

and the canvas liner, placed there to protect it<br />

on its journey.” One such token was a tiny print<br />

of the three Magi, thought to be appropriate<br />

guardians because of their association with<br />

long, difficult journeys.<br />

32 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong>

Her visit to Paris in 1720-21, as the guest of the<br />

influential collector and connoisseur Pierre<br />

Crozat, sparked a widespread interest in<br />

portraits in pastel that continued throughout<br />

eighteenth-century Europe. While in Paris,<br />

Carriera painted the French artist Antoine<br />

Watteau, as well as numerous portraits of the<br />

French nobility including the young Louis<br />

XV. She was elected a member of the Paris<br />

Academy by acclamation, the first foreigner<br />

and only the fifth woman to receive that<br />

honour. While this event is recorded in her<br />

diary, Carriera seems not to have been overly<br />

excited by it. “This was objectively one of the<br />

most incredible events in her life,” remarks<br />

Oberer, “and she just basically writes ‘I was<br />

accepted in the Academy by a great majority’”.<br />

This tendency towards self-effacement was<br />

also evidenced by her inclination to downplay<br />

her impressive financial success. She seems to<br />

have taken the view that her prospects would<br />

benefit from remaining modest about her<br />

accomplishments (and wealth) and presenting<br />

herself to the art world as a quiet, unassuming<br />

spinster.<br />

While preferring, as much as possible, to live<br />

and work in Venice, which helped to reduce her<br />

expenses, Carriera made a long journey to the<br />

royal court in Vienna, Austria, in 1730. There,<br />

she enjoyed the patronage of Emperor Charles<br />

VI, who amassed a large collection of more<br />

than 150 of her pastels. These would later form<br />

the basis of the collection of the Alte Meister<br />

Gallery in Dresden, still the owner of the largest<br />

number of works by the artist. Pastel was<br />

prized for the lifelike quality it conferred on<br />

its subjects and for its ability to reflect, rather<br />

than absorb, light. Carriera’s pastels were<br />

noted in particular for their radiant palettes<br />

and velvety finish. She also brought her skills<br />

as a miniaturist to the finer details. Part of<br />

the appeal of owning a portrait by Carriera<br />

was the identifiable style of the paintings. As<br />

Carriera’s renown grew, her sitters clamoured<br />

to be painted with what Oberer has called the<br />

Rosalba Carriera, 1720/21. King Louis XV of France<br />

© Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden<br />

Photo: Marina Langner & Wolfgang Kreische<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong> • Restoration Conversations 33

Carriera ‘mask’. Oberer argues that the fashion<br />

to be painted ‘by Carriera’ developed into a<br />

desire to ‘be a Carriera’. The ‘sameness’ of her<br />

portraits, noted by some critics, was not due to<br />

a lack of skill or imagination on Carriera’s part,<br />

but simply a consequence of compliance with<br />

the desires of her clients.<br />

Key to Carriera’s success was her acumen as<br />

a businesswoman. “She knew very well how<br />

to organise her business, with the help of her<br />

sister and her mother,” says Oberer. “There<br />

were so many people involved, so many<br />

letters to write and answer, so many packages<br />

to prepare. And there were copies to be made,<br />

because her sister made a lot of copies of the<br />

portraits.” The nerve centre of this operation<br />

was Carriera’s palazzo on the Grand Canal.<br />

Recognised professionally by prestigious<br />

art academies, she was an innovator in her<br />

use of ivory, her popularising of pastels<br />

and her ‘branding’ of the Carriera style.<br />

She had numerous followers, and her<br />

impact continued to be felt for decades<br />

after her death.<br />

Among the documents that Oberer studied<br />

was a room-by-room inventory of the contents<br />

of this property which provided clues as<br />

to how Carriera carried on her business.<br />

The main room, facing out onto the canal,<br />

contained over 30 paintings (mainly pastels),<br />

five mirrors, 14 chairs (but no table), and an<br />

array of porcelain cups and Chinese trays for<br />

serving the then-exotic beverages tea, coffee<br />

and chocolate. This was not just a living room,<br />

Oberer concluded. “It was her studio, it was<br />

her museum and sales room. It was the room<br />

where she received guests and held concerts.”<br />

(In addition to her artistic talent, Carriera was<br />

an accomplished musician.) One can imagine<br />

aristocratic visitors sipping hot chocolate from<br />

delicate chinoiserie cups and inspecting the<br />

rosy-cheeked portraits displayed on the walls,<br />

all the while pondering how they might look<br />

as ‘a Carriera’.<br />

Rosalba Carriera achieved everything<br />

that is thought necessary to be considered<br />

a ‘great artist’. Recognised professionally<br />

by prestigious art academies, she was an<br />

innovator in her use of ivory, her popularising<br />

of pastels and her ‘branding’ of the Carriera<br />

style. She had numerous followers, and her<br />

impact continued to be felt for decades after<br />

her death. But when the Rococo style gave<br />

way to Neoclassicism, Carriera’s name and<br />

her influence were dismissed. What accounts<br />

for this? The light and playful style of the<br />

Rococo period became associated with the<br />

superficiality of France’s ancien regime and all<br />

the frivolity and excesses that encompassed.<br />

It was, perhaps, easy to overlook works that<br />

lacked a seriousness of purpose and ignored<br />

the economic and social realities of life. There<br />

is also the fact that the paintings themselves,<br />

because of their fragility, were difficult to<br />

transport without risk of damage and, as a<br />

result, were not exhibited widely. Until now, the<br />

only monographic exhibition of her work was<br />

held in 1975, in Karlsruhe.<br />

And then there is the question of gender.<br />

Carriera was treated as a rarity as a woman<br />

artist. She endured offensive descriptions<br />

of her appearance by critics who seemed<br />

to suggest that her artistic talent had a<br />

direct inverse relationship to her perceived<br />

unattractiveness. “Just as nature was miserly in<br />

her external gifts all the more did she endow<br />

her with very rare internal talents which<br />

she cultivated with every care,” Anton Maria<br />

Zanetti the Younger wrote of Carriera in 1771.<br />

Unmarried, childless, as sublimely talented<br />

as she was (apparently) lacking in beauty, it<br />

was easy to think of Carriera as something<br />

of an aberration and perhaps, for this reason,<br />

easier to forget. The upcoming exhibition in<br />

Dresden of Carriera’s works and the soon-tobe-published<br />

book by Angela Oberer on the<br />

artist will go some way to redress the balance.<br />

By coincidence, in 1948, another trendsetting<br />

woman art entrepreneur, Peggy Guggenheim<br />

(who also had to put up with disparaging<br />

comments on her appearance), would<br />

purchase the palazzo next door to what had<br />

been Carriera’s residence on the Grand Canal.<br />

That palazzo became the home of the Peggy<br />

Guggenheim Collection, one of the most<br />

visited museums in Venice. Two remarkable<br />

women who became next-door neighbours<br />

across the centuries, successful despite the<br />

odds against them. RC<br />

34 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong>

Rosalba Carriera, Mary with her Left Hand on her Breast. © Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche<br />

Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Photo: Wolfgang Kreische<br />

You can watch the video recording of Angela Oberer’s lecture Rosalba Carriera:<br />

The First Painter of Europe on the Calliope Arts YouTube channel This is one of a<br />

series of lectures on women artists at the British Institute of Florence sponsored<br />

by Calliope Arts.<br />

Rosalba Carriera by Angela Oberer, part of the Lund, Humphries series ‘Illuminating<br />

Women Artists’ will be published on June 15, 20<strong>23</strong>.<br />

Celebrating the 350th anniversary of her birth, the exhibition Rosalba Carriera –<br />

Perfection in Pastel is on at the Alte Meister Gallery in Dresden from 9 June to 24<br />

September 20<strong>23</strong>.<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong> • Restoration Conversations 35

Above: Anna Waser, 1691, Self-portrait at the Age of 12. Kunsthaus, Zürich, Wikimedia Commons<br />

36 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong>

Before the Selfie<br />

A few words on women’s self-portraits<br />

I“I have been paying a lot of attention to how women artists<br />

chose to depict themselves. Every decision is very deliberate in<br />

self-portraits. In the age of the ‘selfie’, where any one of us can<br />

just pick up a phone and take a ‘self-portrait’, I think it becomes<br />

even more pivotal to understand the meaning of those portraits<br />

and those choices,” says Flavia Frigeri, who has spent the past<br />

two and a half years thinking about how women are represented<br />

at Britain’s National Portrait Gallery.<br />

A self-portrait is never just a likeness of the artist, but a female<br />

self-portrait is particularly loaded. The artist often displays the<br />

tools of her trade – a palette, a paintbrush and easel – or includes<br />

objects, such as flowers or elaborate fabrics, to show off her<br />

particular skills as a painter. She may even include her children,<br />

identifying as a mother. She might present an ‘air-brushed’<br />

version of herself, either out of vanity or for marketing purposes.<br />

But, most importantly, she creates a calling card that says, ‘I am a<br />

woman and I am an artist’.<br />

The self-portraits of women artists sometimes depict their family<br />

members – usually fathers or uncles, also in the painting trade,<br />

as a symbol of standing. More rarely, they paint their children or<br />

mothers beside them. Rolinda Sharples’ 1820 self-portrait with<br />

mother Ellen, at the Bristol City Art Museum and Gallery, is one<br />

delightful example. Painting one’s master was equally common<br />

in early self-portraiture, as a way of claiming one’s spot as ‘true<br />

heir’ to the craft. Such is the case of Anna Waser’s 1691 painting<br />

at the Kunsthaus in Zürich once known by its original title: Selfportrait<br />

in the artist’s twelfth year, painting the portrait of her<br />

teacher Johannes Sulzer. At Stockholm’s Nationalmuseum, Mimmi<br />

Zetterström’s self-portrait from 1876 is equally worthy of note.<br />

She paints herself working alone, yet, in this colourful scene, her<br />

atelier or workroom, is a character-of-sorts – and the walls speak<br />

volumes about her prolific nature as a painter.<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong> • Restoration Conversations 37

Left: Alice Neel, 1980. Self-Portrait<br />

© The Estate of Alice Neel<br />

Courtesy of The Estate of Alice Neel<br />

Above: Rolinda Sharples, 1820<br />

Self-portrait with the Artist’s Mother Ellen Sharples<br />

Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery, Wikimedia Commons<br />

Many of the artists featured in this issue of<br />

Restoration Conversations have created one or<br />

more self-portraits that provide us clues to their<br />

personalities. Alice Neel completed her first selfportrait<br />

at the age of 80. “All my life I’ve wanted to<br />

paint a self-portrait,” Neel declared. “But I waited<br />

until now, when people would accuse me of<br />

insanity rather than vanity.” She painted herself<br />

nude, and presents herself as both artist, holding<br />

a paintbrush, and subject, seated in the striped<br />

blue and white chair that featured in many of<br />

her portraits. Not unlike her subjects, she looks<br />

slightly awkward, with her feet splayed and her<br />

torso leaning forward rather than relaxing into<br />

the chair. But the tilt of her chin seems to say, ‘this<br />

is who I am – an artist who tells it like it is.’<br />

Rosalba Carriera was another artist who did<br />

not shy away from painting herself in old(er)<br />

age. Indeed, as Jennifer Higgie points out in The<br />

Mirror and the Palette, in Carriera’s 1730-31 pastel<br />

Self-Portrait as ‘Winter’, she “depicted herself<br />

not only as someone who has aged, but as the<br />

embodiment of the passing of the seasons, as if<br />

she were not only a woman but a landscape as<br />

well.” She is not troubled with vanity. Her grey<br />

hair matches the fur draped around her neck; no<br />

rouge brightens up her cheeks or enhances her<br />

slightly pursed lips [Editor’s note: this painting is<br />

featured at Carriera’s Dresden: show, p. 30]. We<br />

acquire more insight into her inner life with her<br />

1715 Self-portrait Holding a Portrait of her Sister.<br />

Here, again, she presents an unvarnished ‘warts<br />

38 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong>

Above: Rosalba Carriera, 1709<br />

Self-portrait Holding a Portrait of her Sister<br />

Uffizi Galleries, Florence<br />

Right: Mimmi Zetterström, 1876, Self-portrait<br />

Nationalmuseum, Stockholm<br />

Wikimedia Commons<br />

and all’ version of herself, but the fact that she<br />

includes her sister in the picture demonstrates<br />

the importance of this relationship and the depth<br />

of feeling between them. And this is all the more<br />

so when we consider that this was the painting<br />

Carriera contributed to the Medici collection of<br />

self-portraits at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.<br />

Initiated by Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici in<br />

the seventeenth century, this extensive collection<br />

comprises some 1,800 paintings. Until it was<br />

closed for renovations in 2016, 600 self-portraits<br />

were exhibited in the Vasari Corridor, which<br />

connects the Palazzo Vecchio, via the Uffizi and<br />

the Ponte Vecchio, to the Palazzo Pitti on the other<br />

side of the Arno River. Because the Medici Grand<br />

Dukes were particularly keen to collect female<br />

self-portraits, this prestigious series boasts the<br />

highest concentration of works by women artists<br />

available for public viewing in the world. For<br />

anyone fortunate enough to have taken it, the<br />

‘Vasari Corridor tour’ was revelatory – who knew<br />

there were so many recognised female painters<br />

going back to the 1500’s?<br />

When the Vasari Corridor reopens, at a date yet to<br />

be disclosed, it will no longer house the self-portrait<br />

collection. Perhaps the women’s self-portraits will<br />

be dispersed throughout the collection across<br />

different periods. Or perhaps they will be part of<br />

a rotating group of self-portraits in a designated<br />

gallery. But it seems certain that the impact of<br />

concentrating so many works of and by women in<br />

a unique part of the museum will be lost.<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong> • Restoration Conversations 39

40 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong>

One self-portrait that is missing from<br />

the Medici collection is that of Artemisia<br />

Gentileschi. This is surprising given that she<br />

lived and worked in Florence for seven years<br />

and was patronised by Cosimo II de’ Medici.<br />

It sometimes appears as if every female<br />

protagonist in her paintings, whether saint,<br />

Biblical heroine or allegorical figure, is mooted<br />

as a possible ‘self-portrait’. This applies to her<br />

‘Allegory of Inclination’ currently the subject of<br />

a restoration at Casa Buonarroti. Commissioned<br />

by Michelangelo the Younger, and planned<br />

by him in every detail, the commission was<br />

“particularly audacious,” in the words of art<br />

historian Sheila Barker, “because it called for<br />

female nudity in a canvas meant for semipublic<br />

display … Had it been painted by a man,<br />

the female nudity would have been perceived<br />

as an allegorical attribute; however, because it<br />

was painted by an attractive young woman, the<br />

nude body could be taken as a literal reference<br />

to the artist’s own body.”<br />

Barker goes on to explain that “rather than<br />

trying to forestall that inevitable association,<br />

Artemisia embraced it by giving her own<br />

idealised facial features to the nude figure.<br />

In reality, that nude figure, which is seen<br />

from below and, therefore, required difficult<br />

foreshortening, was necessarily made with the<br />

assistance of a female model …”<br />

Artemisia would have been pleased to be<br />

identified with the allegorical figure in the<br />

Inclination because she aspired to be seen<br />

as possessing the same attributes that were<br />

associated with Michelangelo. But it seems to<br />

beg the question, when is a self-portrait not a<br />

self-portrait …? RC<br />

Above: 15th-century depiction of Roman painter Iaia at work, from<br />

Giovanni Boccaccio’s De Mulieribus Claris<br />

Bibliothèque nationale de France. Wikimedia Commons<br />

Left: Artemisia Gentileschi, 1615. Allegory of Inclination<br />

Casa Buonarroti Museum, Florence,<br />

under restoration by Calliope Arts and Christian Levett<br />

FURTHER READING:<br />

Barker, Sheila, Artemisia Gentileschi,<br />

Lund Humphries, London, 2022<br />

Higgie, Jennifer, The Mirror and the Palette,<br />

Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 2021<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong> • Restoration Conversations 41

All About Joan<br />

Reflections on the Monet-Mitchell exhibition<br />

at Fondation Louis Vuitton<br />

By Margie MacKinnon<br />

When I told an artist friend about my (then)<br />

upcoming weekend in Paris, the highlight<br />

of which was to be a visit to the Monet–<br />

Mitchell exhibition, she briefly deflated my spirits<br />

by saying she had found the show disappointing.<br />

The juxtaposition of the American’s works next<br />

to those of the great French master, she opined,<br />

did not enhance Mitchell’s paintings, but made<br />

them seem ‘derivative’. I am happy to report<br />

that my own impression was quite the opposite.<br />

The exhibition was a wonderful showcase of<br />

Mitchell’s works, and she had no trouble holding<br />

her own when viewed ‘in dialogue’ with one of<br />

Impressionism’s greatest exponents.<br />

FLV’s artistic director, Suzanne Page, a visitor<br />

to Joan Mitchell’s home in Vétheuil in 1982,<br />

claimed that the artist “hated” being compared<br />

to Claude Monet, but such comparisons were all<br />

but inevitable given that, for many years, Mitchell<br />

lived in a house whose terrace overlooked the<br />

residence where Monet spent the final years of<br />

his life. Her view was the landscape that he often<br />

painted. Many Abstract Expressionist painters,<br />

including Mitchell, were inspired by Monet’s<br />

large-scale works, such as his celebrated water<br />

lilies series. Perhaps Mitchell, who was intensely<br />

competitive, thought she could not come out on<br />

top in such a comparison, given Monet’s exalted<br />

stature in the art world.<br />

Born in 1925, Mitchell grew up in a well-to-do<br />

family in Chicago. According to Mary Gabriel in<br />

her authoritative chronicle Ninth Street Women,<br />

Joan’s mother was distant, and her father was so<br />

disappointed she was not a boy that he wrote the<br />

name ‘John’ on her birth certificate. Perhaps in a<br />

bid to win her father’s approval, Mitchell took up<br />

a variety of sports – figure skating, diving and<br />

tennis – at which she excelled. She attacked her<br />

art studies at the School of the Art Institute of<br />

Chicago with equal determination.<br />

Upon graduation she won a travelling fellowship<br />

and a print prize that led to her first mention in<br />

ArtNews. By 1950, Mitchell was in New York where<br />

she soon wangled an introduction to Willem de<br />

Kooning, who would have a major influence on<br />

her early work. She joined the group of artists,<br />

Right: Installation<br />

views of Joan Mitchell<br />

Retrospective. Courtesy of<br />

Fondation Louis Vuitton<br />

42 Restoration Conversations • <strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong>

<strong>Spring</strong> / <strong>Summer</strong> 20<strong>23</strong> • Restoration Conversations 43

Below: Joan Mitchell, 1971. Plowed Field, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris © The Estate of Joan Mitchell<br />

including Grace Hartigan and Elaine de Kooning,<br />

that congregated at the Cedar Bar. In 1951, the<br />

three of them, together with Lee Krasner and<br />

Helen Frankenthaler would be the only women<br />

to be included in what would become known as<br />

the ‘Ninth Street Show’, a seminal moment in the<br />

American Abstract Expressionist movement in art.<br />

I arrived at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, on<br />

the edge of the Bois de Boulogne, some thirty<br />

minutes before the time designated on my<br />

ticket. The clear skies promised by the weather<br />

forecast gave way to a grey drizzle, but even<br />

this didn’t dampen my spirits. The Fondation’s<br />