Gastroenterology Today Summer 2023

Gastroenterology Today Summer 2023

Gastroenterology Today Summer 2023

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Volume 33 No. 2<br />

<strong>Summer</strong> <strong>2023</strong><br />

Passionate about Endoscopy?<br />

We are clearing NHS trust waiting lists<br />

one weekend at a time, and<br />

we need your help<br />

18 Week Support <strong>Gastroenterology</strong>:<br />

Building Expert Teams

Better Resource<br />

Management<br />

for Digestive<br />

Disease Pathways<br />

Quantum Blue ® for Point of<br />

Care helps triage patients<br />

in clinic giving results in a<br />

rapid time frame (15 mins)<br />

Calprotectin Testing<br />

Make more informed<br />

clinical decisions without<br />

waiting for lab results.<br />

IBDoc ® Home Tests. Supporting<br />

remote patient monitoring and<br />

virtual clinics<br />

Faecal Immunochemical Testing<br />

Complete bespoke solutions to triage patients<br />

within the colorectal cancer pathway.<br />

New kit ordering portal for<br />

convenient logistics<br />

Customised FIT Kits delivered to patient<br />

‘ready to use’ – everything the patient<br />

requires to take their sample safely at<br />

home for return to a laboratory<br />

19 TH – 22 ND JUNE<br />

COME AND<br />

SEE US ON<br />

STAND B17<br />

Supplied by<br />

For more information, to discuss your requirements or organise an<br />

evaluation please contact: digestivedx@alphalabs.co.uk<br />

T: +44 (0)23 8048 3000<br />

E: sales@alphalabs.co.uk<br />

W: www.alphalabs.co.uk<br />

02380 483000 • sales@alphalabs.co.uk • www.alphalabs.co.uk

CONTENTS<br />

CONTENTS<br />

4 EDITORS COMMENT<br />

6 FEATURE Evaluation of non-gastric upper gastrointestinal<br />

system polyps: an epidemiological assessment<br />

13 FEATURE Evaluation of gut microbiota of Iranian patients<br />

with celiac disease, non-celiac wheat sensitivity,<br />

and irritable bowel syndrome: are there any<br />

similarities?<br />

29 COMPANY NEWS<br />

COVER STORY<br />

18 Week Support is the leading insourcing provider in the UK, partnering with<br />

trusts to address their waiting lists by optimising the utilisation of their theatres<br />

and clinics. Although we cover a wide range of specialties, our emphasis lies in<br />

Endoscopy and <strong>Gastroenterology</strong>, where we strive to ensure the highest quality<br />

of care for our patients.<br />

After Covid 19, the number of patients waiting more than 6 weeks for<br />

endoscopies, gastroscopies and flexible sigmoidoscopies rose dramatically,<br />

from 9.3% in February 2020 to 67.6% in May 2020. Since then, the NHS has<br />

been working tirelessly to address the influx of patients waiting for procedures,<br />

although this has not been easy. In March <strong>2023</strong>, the percentage of patients<br />

waiting more than 6 weeks for this procedure was 37.5%; still far greater than<br />

the 5% aim set out by the NHS <strong>2023</strong>/2024 Operating Plan.<br />

This issue edited by:<br />

Andrew Poullis<br />

c/o Media Publishing Company<br />

Greenoaks<br />

Lockhill<br />

Upper Sapey, Worcester, WR6 6XR<br />

ADVERTISING & CIRCULATION:<br />

Media Publishing Company<br />

Greenoaks, Lockhill<br />

Upper Sapey, Worcester, WR6 6XR<br />

Tel: 01886 853715<br />

E: info@mediapublishingcompany.com<br />

www.MediaPublishingCompany.com<br />

PUBLISHING DATES:<br />

March, June, September and December.<br />

COPYRIGHT:<br />

Media Publishing Company<br />

Greenoaks<br />

Lockhill<br />

Upper Sapey, Worcester, WR6 6XR<br />

PUBLISHERS STATEMENT:<br />

The views and opinions expressed in<br />

this issue are not necessarily those of<br />

the Publisher, the Editors or Media<br />

Publishing Company.<br />

Next Issue Autumn <strong>2023</strong><br />

Designed in the UK by me&you creative<br />

While progress has been made since Covid 19, recent data points to a<br />

potential increase in patients waiting more than 6 weeks for these procedures.<br />

We believe that the solution to this problem lies in maximising the use of<br />

existing capacity in addition to the new capacity created by the government as<br />

it continues to invest in community diagnostics centres.<br />

We need to support the NHS in transforming its model to a seven-day<br />

service to tackle this problem thereby making full use of the existing capacity.<br />

Insourcing can achieve this by providing flexible workforce models and making<br />

better use of the capacity already available within the NHS.<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SUMMER <strong>2023</strong><br />

3

EDITORS COMMENT<br />

EDITORS COMMENT<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SUMMER <strong>2023</strong><br />

“Over the<br />

years a<br />

number<br />

of Nobel<br />

prize<br />

winners<br />

for<br />

medicine<br />

have<br />

originated<br />

in<br />

Liverpool<br />

or carried<br />

out their<br />

early<br />

works in<br />

this city.”<br />

Liverpool <strong>2023</strong><br />

Eurovision and BSG! Liverpool is having a busy <strong>2023</strong>. Although no home grown success<br />

in the Eurovision this year Liverpool is a city with a long history of awards and international<br />

successes. Ignoring the obvious footballing awards, in the field of science and medicine<br />

Liverpool has a long history.<br />

Over the years a number of Nobel prize winners for medicine have originated in Liverpool or<br />

carried out their early works in this city.<br />

Sir Ronald Ross in 1902 was recognised for his work on transmission of malaria.<br />

In 1932 Sir Charles Scott Sherrington was recognised as he defined the spinal reflex and<br />

defined synapses.<br />

More pertinent to gastroenterology was Professor Rodney Porter, who started his studies in<br />

Liverpool, and was awarded Nobel prize in 1972 determining the chemical structure of an<br />

antibody - an important first step in the field of biologic drug therapies which have become<br />

the cornerstone of IBD management.<br />

The BSG conference will showcase national and international work in its annual meeting in<br />

Liverpool.<br />

Andrew Poullis<br />

St George’s Hospital<br />

4

FEATURE<br />

EVALUATION OF NON-GASTRIC UPPER<br />

GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM POLYPS:<br />

AN EPIDEMIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT<br />

Çağdaş Erdoğan*, Derya Arı, Bayram Yeşil, Kenan Koşar, Orhan Coşkun, İlyas Tenlik, Hasan Tankut Köseoğlu & Mahmut Yüksel<br />

Department of <strong>Gastroenterology</strong>, Ankara City Hospital, University of Health Sciences, Bilkent Avenue, Çankaya, 06800 Ankara, Turkey. *email: cagdas.erdogan@saglik.gov.tr;<br />

cagdas_edogan@hotmail.com Scientific Reports | (<strong>2023</strong>) 13:6168 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-33451-1<br />

Abstract<br />

Non-gastric upper gastrointestinal system polyps are detected rarely<br />

and mostly incidentally during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. While<br />

the majority of lesions are asymptomatic and benign, some lesions<br />

have the potential to become malignant, and may be associated with<br />

other malignancies. Between May 2010 and June 2022, a total of<br />

127,493 patients who underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy<br />

were retrospectively screened. Among these patients, those who had<br />

polyps in the esophagus and duodenum and biopsied were included in<br />

the study. A total of 248 patients with non-gastric polyps were included<br />

in this study. The esophageal polyp detection rate was 80.00/100,000,<br />

while the duodenal polyp detection rate was 114.52/100,000. In<br />

102 patients (41.1%) with esophageal polyps, the mean age was<br />

50.6 ± 15.1, and 44.1% (n = 45) were male. The most common type<br />

of polyps was squamous papilloma (n = 61, 59.8%), followed by<br />

inflammatory papilloma (n = 18, 17.6%). In 146 patients (58.9%) with<br />

duodenal polyps, the mean age of patients was 58.3 ± 16.5, and 69.8%<br />

(n = 102) were male. Brunner’s gland hyperplasia, inflammatory polyp,<br />

ectopic gastric mucosa, and adenomatous polyp were reported to be<br />

the most prevalent types of polyps in the duodenum overall (28.1%,<br />

27.4%, 14.4%, and 13.7%, respectively). It is crucial to identify rare nongastric<br />

polyps and create an effective follow-up and treatment plan in<br />

the era of frequently performed upper gastrointestinal endoscopies. The<br />

epidemiological assessment of non-gastric polyps, as well as a followup<br />

and treatment strategy, are presented in this study.<br />

some lesions can be considered as premalignant. Since glycogenic<br />

acanthosis, the most prevalent polypoid lesion in the esophagus, has a<br />

frequency of 3.5–15%, a characteristic structure, and a benign nature,<br />

these lesions are simple to identify and don’t need to be biopsied or<br />

evaluated pathologically 3-5 . With a rate between 0.01% and 0.45%,<br />

esophageal squamous papilloma (Fig. 1) are relatively the most prevalent<br />

polypoid lesions in the esophagus 6,7 . It is mostly seen in patients<br />

around 50 years of age, in the distal esophagus and as a single lesion 8 .<br />

Although most papilloma are asymptomatic, dysphagia due to large<br />

papilloma has been reported rarely 9 . Esophageal papillomas are followed<br />

in incidence by inflammatory polyps 10 , esophageal parakeratosis 11 ,<br />

and esophageal adenomas 12-14 that develop on the basis of Barrett’s<br />

esophagus and carry malignant potential.<br />

Lymphangiomas 15 and neuroendocrine tumors that originate from the<br />

submucosa are other esophageal lesions that can come across. These<br />

lesions can, however, only be found extremely rare. Neuroendocrine<br />

tumors can be seen in the pancreas or tubular organs of the GI<br />

system and show neuroendocrine differentiation. Endoscopically,<br />

neuroendocrine tumors of the digestive tract can present as polypoid<br />

forms, nodules, masses, ulcers, or stenosis, and they can be single or<br />

multiple and range in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters.<br />

These tumors, which are rare in the esophagus (only 50 cases have<br />

been documented), typically form sessile polypoid structures in the<br />

lower third 16 .<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SUMMER <strong>2023</strong><br />

6<br />

Introduction<br />

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (esophagogastroduodenoscopy,<br />

EGD) includes evaluation of the oropharynx, esophagus, stomach, and<br />

proximal duodenum. EGD can be performed with indications such as<br />

dyspeptic complaints unresponsive to medical treatment, presence<br />

of alarm symptoms, upper gastrointestinal symptoms after the age of<br />

50, dysphagia, persistent vomiting, or upper gastrointestinal bleeding.<br />

Polyps are mostly detected incidentally during upper gastrointestinal<br />

endoscopy. However, management and appropriate pathological<br />

evaluation of polyps are very important 1,2 .<br />

Many benign lesions can be encountered during the endoscopic<br />

evaluation of the esophagus. Most lesions are rare and asymptomatic.<br />

Although most of these lesions do not have malignant potential,<br />

Duodenal polyps are generally quite rare and can be classified as nonneoplastic<br />

and neoplastic. Based on the respective incidence, nonneoplastic<br />

lesions include ectopic gastric mucosa, inflammatory polyps,<br />

Brunner’s gland hyperplasia, peutz-jeghers polyps, and hyperplastic<br />

polyps. Whereas, neoplastic lesions include adenomas, gastrointestinal<br />

stromal tumors, Brunner’s gland adenoma, carcinoid tumors,<br />

leiomyoma, lipoma, schwannoma can be counted. Duodenal adenomas<br />

(Figs. 2, 3) have three major types: villous adenomas, tubular adenomas,<br />

and Brunner’s gland adenomas. Villous adenomas carry a significant<br />

risk of malignancy. Since the incidence of colon adenomas increases in<br />

patients with duodenal polyps, colonoscopy should be performed when<br />

these polyps are detected 17 .<br />

Tubular adenomas are more common in the duodenum, are mostly<br />

asymptomatic and have less malignant potential. Brunner’s gland<br />

adenomas are rare small intestinal polyps that are more common,

FEATURE<br />

In this study we aimed to evaluate the epidemiological distribution of<br />

polyps detected during EGD and submitted to pathological assessment<br />

by biopsy, as well as the follow-up and treatment strategy in polyps with<br />

malignant potential or symptomatic.<br />

Patients/material and methods<br />

Figure 1. Esophageal squamous papilloma.<br />

Our study was approved by Ankara City Hospital Scientific Research<br />

Evaluation and Ethics Committee (Approval No: E1-22-2328). The<br />

procedures implemented until February 2019 were carried out at Ankara<br />

Turkey Yüksek İhtisas Training and Research Hospital. Since Ankara<br />

Turkey Yüksek İhtisas Training and Research Hospital joined the Ankara<br />

City Hospital after February 2019, the patients included in the study after<br />

this date were selected among the patients followed up and treated at<br />

Ankara City Hospital.<br />

Between May 2010 and June 2022, a total of 127,493 patients who<br />

underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with indications such as<br />

dyspepsia, dysphagia, and iron deficiency anemia were retrospectively<br />

screened. Among these patients, those who had polyps in the<br />

esophagus and duodenum and biopsied were included in the study.<br />

Figure 2. Duodenal adenomatous polyp.<br />

In patients who underwent EGD, biopsy or excision was performed on<br />

all polyps detected in the esophagus that were solitary or larger than<br />

1 cm. All patients with Barrett’s esophagus discovered to have polyps<br />

underwent biopsies. When dysplasia clusters are observed rather<br />

than a single polyp formation in Barrett’s esophagus, which is where<br />

the majority of esophageal adenomas arise from, the vascular pattern<br />

was assessed with NBI endoscopy, and a biopsy was collected for<br />

esophageal adenoma. In addition, biopsies or excisions were performed<br />

on hyperemic polyps, polyps with aberrant vascular patterns on narrowband<br />

imaging (NBI) endoscopy, and ulcerated polyps. However, no<br />

biopsy was performed when multiple instances of glycogenic acanthosis<br />

were found. In case of detection of polyps in the duodenum, polyps<br />

were biopsied or excised from all patients.<br />

Figure 3. Duodenal adenomatous polyp magnified.<br />

accounting for 10.6% of duodenal tumors 18 . Ectopic gastric mucosa may<br />

present as polypoid lesions which are rare congenital disorders and are<br />

detected incidentally during upper GI endoscopy. It has been reported<br />

in the literature that heterotopic gastric mucosa may be associated with<br />

duodenal ulcers 19 . Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) are mostly<br />

encountered in the stomach, they can also be seen in the esophagus<br />

(< 1%) and duodenum (5%) 20 . Tumors originating from the upper GI may<br />

present with dysphagia, GI bleeding, or obstructive jaundice.<br />

Duodenal or ampullary NETs are extremely rare and account for<br />

approximately 2.6% of all NETs 21 . These tumors are of clinical<br />

importance as most of them are asymptomatic and potentially<br />

malignant. They typically occur in the I and II duodenal sections,<br />

preferring the peripapillary region, and under endoscopic vision, they<br />

show as a single, small lesion (frequently less than 1 cm in size).<br />

Additionally, they may exist in groups or be linked to neuroendocrine<br />

tumors in other organs 16 .<br />

Patients who had polyps but could not be biopsied due to<br />

antiaggregant/anticoagulant use, hemodynamic instability, and patient<br />

intolerance were excluded from the study. In addition, patients with<br />

gastric polyps were also excluded. Additionally, patients with esophageal<br />

polyps who underwent biopsies and who, upon pathologic inspection,<br />

revealed to have glycogenic acanthosis were removed from the study.<br />

Patients’ demographic characteristics such as age, gender, smoking,<br />

history of comorbid diseases and drug use were recorded. Polyp sizes,<br />

polyp types, number of polyps and histopathological findings were<br />

recorded in patients who were found to have esophageal and duodenal<br />

polyps and biopsied. Additionally, antrum biopsies were performed to check<br />

for H. pylori in patients with polyps. The pathologists stained the tissue<br />

samples with Giemsa and tested for the presence of H. pylori. Patients<br />

with helicobacter pylori positivity as a result of pathology were separately<br />

identified. According to the pathology results, whether the patients<br />

had reflux findings in their histories, whether they had a history of head<br />

and neck cancer, and previous endoscopic and colonoscopy findings,<br />

if any, were evaluated. The frequency per 100,000 of esophageal and<br />

duodenal polyps detected in the patients was reported. The pathological<br />

distributions of the polyps were also displayed as a rate per 100,000.<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SUMMER <strong>2023</strong><br />

7

FEATURE<br />

In patients undergoing colonoscopy the cleanliness of the colonoscopy<br />

was evaluated using the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS).<br />

Following colonoscopy cleaning, patients with BBPS 0 or 1 were taken<br />

for another colonoscopy. Colonoscopy cleanliness scores BBPS 2 and 3<br />

were used to assess all study participants who had non-gastric polyps.<br />

Withdrawal from the colonoscopy took at least 10 min.<br />

Endoscopic evaluation was performed with Olympus brand GIF-Q260<br />

model gastroscopes. Before the procedure, patients were given<br />

sedo-analgesia or topical anesthetic containing 10% lidocaine to the<br />

oropharynx, accompanied by an anesthesiologist. The lesions were<br />

removed with forceps or snare. The biopsy material was fixed with 10%<br />

formaldehyde solution and sent for pathological evaluation.<br />

Statistical analysis<br />

All statistical analyzes were performed using SPSS software (SPSS<br />

for Windows, version 25.0, IBM. Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The<br />

Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to determine the normality of the<br />

continuous variables. Normally distributed variables were expressed<br />

as mean ± standard deviation and non-normally distributed variables<br />

as median and interquartile range. Normally distributed variables<br />

were compared using the student t test and non-normally distributed<br />

variables using the Mann–Whitney U test. Chi-square (χ 2 ) test and<br />

Fisher’s Exact test were used for group comparisons (cross tables)<br />

of nominal variables. Two-tailed p values < 0.05 were considered<br />

statistically significant.<br />

Ethics committee approval<br />

This study was complied with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Helsinki<br />

Declaration that was then modified in 2008. The study protocol was<br />

approved by Ankara City Hospital ethics committee (Approval No: E1-<br />

22-2328).<br />

Informed consent<br />

Informed consent was obtained from all patients participating in the<br />

study.<br />

All patients (n = 102)<br />

Age, years 50.6 ± 15.1 –<br />

Gender, male, n (%) 45 (44.1) –<br />

Smoking, n (%) 56 (54.9) –<br />

Polyp size, mm 5.0 (4.0–7.0) –<br />

Number of polyps 1.0 (1.0–1.0) –<br />

Polyp type, n (%)<br />

Pedunculated 65 (63.7) –<br />

Sessile 37 (36.3) –<br />

Pathology, n (%)<br />

Squamous papilloma 65 (63.7) 50.98<br />

Inflammatory polyp 21 (20.7) 16.47<br />

Hyperplastic polyp 3 (2.9) 2.35<br />

Lymphangioma 3 (2.9) 2.35<br />

Esophageal parakeratosis 6 (5.9) 4.70<br />

Esophageal adenoma 4 (3.9) 3.14<br />

Helicobacter pylori, n (%) 26 (25.5) –<br />

Reflux esophagitis, n (%) 17 (16.7) –<br />

Other endoscopic findings, n (%)<br />

Normal 8 (7.8) –<br />

Antral gastritis 31 (30.4) –<br />

Bulbitis 3 (2.9) –<br />

Pangastritis 49 (48.0) –<br />

Antral gastritis + bulbitis 9 (8.9) –<br />

Gastric lymphoma 2 (2.0) –<br />

Colonoscopy, n (%) 76 (74.5) –<br />

Colon polyp localization, n (%)<br />

Transverse + ascending + sigmoid 3 (2.9) –<br />

Transverse + ascending + rectum 3 (2.9) –<br />

Descending + transverse 4 (3.9) –<br />

Rectum 5 (4.9) –<br />

Colon polyp pathology, n (%)<br />

Adenomatous 15 (14.7) –<br />

Rate per 100,000 patients<br />

Table Table 1. 1. Demographic characteristics, endoscopic endoscopic and and colonoscopy colonoscopy findings, and pa<br />

of patients findings, with and esophageal pathological polyps, evaluations pathologic of patients findings with as esophageal rate per 100,000 patients. D<br />

median polyps, ± SD pathologic or median findings (IQR) or as frequency rate per 100,000 (%). SD patients. standard Data deviation. are<br />

expressed as median ± SD or median (IQR) or frequency (%).<br />

SD standard deviation.<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SUMMER <strong>2023</strong><br />

Results<br />

Vol:.(1234567890)<br />

A total of 248 patients who were evaluated for non-gastric polyps<br />

were included in this study. Total evaluation revealed a detection rate<br />

of 194.52 non-gastric polyps per 100,000 patients. In this context,<br />

the esophageal polyp detection rate was 80.00 per 100,000, while<br />

the duodenal polyp detection rate was 114.52 per 100,000.<br />

One hundred and two (41.1%) of the included patients were those<br />

with esophageal polyps. The mean age of patients with esophageal<br />

polyps was 50.6 ± 15.1, and 44.1% (n = 45) were male. The median<br />

size of esophageal polyps was 5.0 (4.0–7.0) mm. Pedunculated<br />

polyps were seen in 63.7% of cases (n = 65), while sessile polyps<br />

were found in 36.3% of cases (n = 37). The most common type<br />

of polyps was squamous papilloma (n = 65, 63.7%), followed by<br />

inflammatory papilloma (n = 18, 17.6%). Helicobacter pylori was<br />

found in 26 (25.5%) and reflux esophagitis in 21 (20.7%) patients.<br />

The most common endoscopic gastric finding was pangastritis<br />

(n = 49, %48.0) followed by antral gastritis (n = 31, %30.4).<br />

Adenomatous polyps were detected in 15 of 76 patients with<br />

esophageal polyps who underwent colonoscopy. Table 1 includes<br />

demographic information as well as endoscopic and colonoscopic<br />

findings, pathology results, and epidemiological rates of patients<br />

with esophageal polyps.<br />

When patients with duodenal polyps were evaluated (n = 146),<br />

polyps were observed in the duodenal bulb in 91 patients (62.3%)<br />

and in the second part of the duodenum (D2) in 55 patients (37.7%).<br />

The mean age of patients with duodenal polyps was 58.3 ± 16.5,<br />

and 69.8% (n = 102) were male. The median size of duodenal polyps<br />

was 7.0 (3.5–15.0) mm. Brunner’s gland hyperplasia, inflammatory<br />

polyp, ectopic gastric mucosa, and adenomatous polyp were<br />

reported to be the most prevalent types of polyps in the duodenum<br />

overall (28.1%, 27.4%, 14.4%, and 13.7%, respectively). In<br />

subgroup analysis Brunner’s gland hyperplasia was most common<br />

in bulbus (36%), while adenomatous polyp was most common in D2<br />

(bulbus vs. D2; 2 vs. 18; p < 0.001). All polyps with adenomatous<br />

pathology were detected in the second continent of the duodenum,<br />

whereas individuals with ectopic gastric mucosa as a result of<br />

pathology had polyp localization in the first continent (p0.00.1 for<br />

both findings). The presence of antral gastritis, bulbitis, duodenitis,<br />

8

FEATURE<br />

pangastritis, pangastritis + bulbitis, atrophic gastritis, FAP, gastric<br />

cancer and peutz-jeghers syndrome was at similar rates between<br />

both groups. In addition, colonoscopy was performed in 88 (%60.3)<br />

patients with polyps in the duodenum, and polyps were detected in<br />

the colon in 35 (%24) of them. While hyperplastic polyp was found<br />

in the colon in two patients with polyp in the bulbus, adenomatous<br />

polyp was detected in the colon in the 33 patients and in all patients<br />

with polyps in the second part of the duodenum. Table 2 includes<br />

demographic information as well as endoscopic and colonoscopic<br />

findings, pathology results, and epidemiological rates of patients<br />

with duodenal polyps.<br />

All patients (n = 146)<br />

Age, years 58.3 ± 16.5 –<br />

Gender, male, n (%) 102 (69.8) –<br />

Smoking, n (%) 81 (55.5) –<br />

Polyp size, mm 7.0 (3.5–15.0) –<br />

Number of polyps 1.0 (1.0–2.5) –<br />

Polyp localization, n (%)<br />

Duodenal bulb 91 (62.3) 71.38<br />

Second part of the duodenum (D2) 55 (37.7) 43.14<br />

Pathology, n (%)<br />

Brunner gland hyperplasia 41 (28.1) 32.16<br />

Ectopic gastric mucosa 21 (14.4) 16.47<br />

Inflammatory polyp 40 (27.4) 31.37<br />

Villous adenoma 4 (2.7) 3.14<br />

Neuroendocrine tumor 3 (2.1) 2.35<br />

Tubular adenoma 4 (2.7) 3.14<br />

Hyperplastic polyp 7 (4.8) 5.49<br />

Adenomatous polyp 20 (13.7) 15.69<br />

Hamartomatous polyp 6 (4.1) 4.71<br />

Helicobacter pylori, n (%) 14 (9.6) –<br />

Other endoscopic findings, n (%)<br />

Antral gastritis 50 (34.2) –<br />

Duodenal ulcer 13 (8.8) –<br />

Duodenitis 3 (2.1) –<br />

Pangastritis 64 (43.8) –<br />

Pangastritis + bulbitis 5 (3.4) –<br />

Atrophic gastritis 3 (2.1) –<br />

FAP 3 (2.1) –<br />

Gastric CA 3 (2.1) –<br />

Peutz-jeger 2 (1.4) –<br />

Colonoscopy, n (%) 88 (60.3)<br />

Detection of polyps in colonoscopy, n (%) 35 (24.0) –<br />

Colon polyp localization, n (%)<br />

Rectosigmoid 22 (15.1) –<br />

Other colonic parts 13 (8.9) –<br />

Polyp type, n (%)<br />

Rate per 100,000 patients<br />

In our study, esophageal adenocarcinoma was diagnosed in 6<br />

individuals who underwent biopsies following the discovery of an<br />

esophageal polypoid lesion. Two of the individuals who were found<br />

to have duodenal polypoid lesions had a biopsy, which revealed<br />

duodenal adenocarcinoma. All malignant esophageal and duodenal<br />

lesions were ulcero-vegetative and fragile in appearance, and they<br />

were all assessed separately from benign esophageal lesions.<br />

Discussion<br />

As the frequency of performing upper GI endoscopy increases in<br />

the world, the detection of non-gastric polyps has also increased.<br />

Although gastric polyps can be assessed more easily due to their<br />

frequency, non-gastric polyps cannot be recognized adequately<br />

due to their rarity. These polyps may be benign, as well as they<br />

may carry the risk of malignancy, and may be an indicator of an<br />

accompanying malignancy. In this study we sought to assess the<br />

prevalence of non-gastric polyps in the general population, their<br />

distribution by localization, their clinical significance, and follow-up<br />

and treatment approaches. Our research revealed that 194.52 out of<br />

100,000 upper GI endoscopies discovered non-gastric polyps. When<br />

assessed according to polyp localization, the rate of esophageal<br />

polyp identification was 80.00 per 100,000, whereas the rate of<br />

duodenal polyp detection was 114.52 per 100,000. Squamous<br />

papilloma, inflammatory papilloma, and esophageal parakeratosis are<br />

the most frequently detected esophageal polyps (50.98, 16.47, and<br />

4.70 per 100,000, respectively), whereas Brunner gland hyperplasia,<br />

inflammatory polyp, ectopic gastric mucosa, and adenomatous polyp<br />

are the most frequently detected duodenal polyps (32.16, 31.37,<br />

16.47, and 15.69 per 100,000, respectively,).<br />

Bulur et al. 22 evaluated 19,560 patients and found non-gastric polyps<br />

in 38 of them. In our study, 127,493 patients were evaluated, and<br />

248 non-gastric polyps were detected. Total evaluation revealed a<br />

detection rate of 194.52 non-gastric polyps per 100,000 patients.<br />

We were able to report the incidence rate in 100,000 patients as an<br />

epidemiological data for rare non-gastric polyps as a result of our<br />

study because of the large patient group we screened.<br />

Hyperplastic 2 (1.4) –<br />

Adenomatous 33 (22.6) –<br />

In the series of Szanto et al. 7 evaluating 35-year upper gastrointestinal<br />

endoscopies, nearly 60,000 upper GI endoscopy was performed,<br />

Table Table 2. 2. Demographic characteristics, characteristics, endoscopic endoscopic and colonoscopy and colonoscopy findings, and pathological and squamous evaluations papilloma was detected in 155 patients. None of<br />

of patients findings, with and duodenal pathological polyps, evaluations pathologic findings of patients as rate with per duodenal 100,000 patients. Data are expressed as<br />

median polyps, ± SD pathologic or median (IQR) findings or frequency as rate per (%). 100,000 SD standard patients. deviation. Data are<br />

expressed as median ± SD or median (IQR) or frequency (%).<br />

SD standard deviation.<br />

these have turned into malignancies. Mosca et al. 9 examined 7618<br />

upper GI endoscopy procedures and detected squamous papilloma<br />

in 9 patients. In our study, squamous papilloma was detected in 65<br />

of 127,493 patients evaluated over a 12-year period. Looking at the<br />

studies in the literature, the rate of detecting squamous papilloma<br />

in upper GIS endoscopy has been reported between 0.045 and<br />

0.26% 6,7,9 . Consistently with the literature, this rate was found 50.98<br />

per 100,000 patients in our study. None of the patients developed<br />

malignancy during their mean follow-up of 3.2 years. In a case<br />

presented by Kostiainen et al. 23 , the patient had the symptoms<br />

of dysphagia and vomiting due to large squamous papilloma.<br />

In our study, 63 of 65 patients with squamous papillomas were<br />

asymptomatic, while squamous papilloma larger then 20 mm was<br />

detected in two patient who had intermittent nausea and vomiting.<br />

Mandard et al. 24 found accompanying esophageal parakeratosis in<br />

approximately 40% of 400 patients, newly diagnosed with head and<br />

neck squamous cell carcinoma. However, no malignancy was found to<br />

originate from the parakeratotic area in the esophagus. In our study, 4<br />

Vol.:(0123456789)<br />

of 6 patients (66.6%) with esophageal parakeratosis had a history of<br />

squamous cell head and neck cancer (larynx and hypopharynx). In the<br />

light of these findings, it would be appropriate to screen the patients<br />

for possible head and neck malignancies in the case of esophageal<br />

parakeratosis detected incidentally in upper GI endoscopy.<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SUMMER <strong>2023</strong><br />

9

FEATURE<br />

Esophageal adenomas typically present as wide islets of dysplasia rather<br />

than a single polyp and typically develop in the presence of Barrett’s<br />

esophagus. In a case series presented by Wong et al. 13 , polypoid<br />

lesions developing on the ground of Barrett’s esophagus, with dysplastic<br />

adenomas and adenocarcinomas found in the pathology were evaluated.<br />

In our study, esophageal adenoma was detected in four patients and all<br />

four also had Barrett’s esophagus. These patients underwent surgical<br />

esophagectomy afterward. The risk of adenocarcinoma is quite high<br />

in patients with Barrett’s esophagus and accompanying adenoma in<br />

the esophagus, and these patients should be evaluated further, and<br />

the lesion should be removed endoscopically or surgically. Due to the<br />

presence of Barrett’s esophagus in these patients, mucosectomy or<br />

ablation procedures for the disease should be integrated into endoscopic<br />

treatment strategies in addition to polyp excision. An esophagectomy is a<br />

surgical option in which the patient’s polyp and esophagus segment are<br />

removed together, and the small intestine or stomach is anastomosed.<br />

Europe. In addition to being an epidemiological study with a large<br />

patient group to evaluate, our study also offers suggestions for the best<br />

examination and treatment approaches to use when non-gastric polyps<br />

are found. The epidemiological study we conducted is the largest on<br />

non-gastric polyps ever published in the world’s literature.<br />

In conclusion, nowadays, with the widespread utilization upper GI<br />

system endoscopy, it is critical to recognize, monitor, and treat common<br />

lesions as well as less frequent but clinically significant lesions. Our<br />

study is not only the broadest evaluation of non-gastric polyps, but it<br />

also provides clinical approach recommendations for these polyps and<br />

discloses the prevalence of these polyps in the general population.<br />

Data availability<br />

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available<br />

from the corresponding author on reasonable request.<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SUMMER <strong>2023</strong><br />

Levine et al. 25 evaluated 27 patients with Brunner gland hyperplasia<br />

detected in the duodenum, and GIS bleeding was found in 10 of the<br />

patients, obstruction in 10, and incidentally in 7 patients. In our study,<br />

Brunner’s gland hyperplasia was detected in the duodenum in 41<br />

patients with 21 of them having GI bleeding and 9 signs of obstruction.<br />

It was detected incidentally in 11 of them. Although Brunner’s gland<br />

hyperplasia are benign lesions, they should be treated as they may have<br />

clinical symptoms. We treated all patients endoscopically, except for one<br />

patient with obstruction. In the long-term follow-up, the patients were<br />

observed up as stable.<br />

Ectopic gastric mucosa are benign lesions that can be detected incidentally<br />

in the duodenum. Naguchi et al. 19 found ectopic gastric mucosa in 76 (55%)<br />

of 137 patients with duodenal ulcer, and Helicobacter pylori was detected in<br />

59% (45/76) of the biopsies taken from them. In our study, duodenal ulcer<br />

was detected in 12 (57.1%) of 21 patients with ectopic gastric mucosa, and<br />

HP positivity was observed in 13 (61.9%) of them.<br />

Sporadic duodenal adenomas are very rare and have the potential to<br />

transform into adenocarcinoma by showing similar morphological and<br />

molecular features with colorectal adenomas. The majority of sporadic<br />

duodenal adenomas are flat or sessile solitary lesions with pearly villi<br />

surfaces that develop on the descending duodenum’s posterior or lateral<br />

walls 26 . Witterman et al. 17 showed that 42% of patients with duodenal<br />

villous adenoma had malignant cells. In addition, it was shown that the<br />

rate of detecting concomitant colon adenoma is increased in these<br />

patients. In our study, all 20 adenomas detected in the duodenum<br />

originated from the second part of the duodenum, and malignant cells<br />

were detected in 1 of 4 villous adenomas. Again, 17 (85.0%) of these<br />

patients had adenomatous polyps in the colon. When polyps are found<br />

in the duodenum, they should be removed via snare polypectomy,<br />

endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), endoscopic submucosal<br />

dissection (ESD), or argon plasma coagulation (APC) ablation due to<br />

their potential for malignancy. Then again, based on these findings, it<br />

would be a reasonable approach to be careful in terms of malignancy<br />

in patients with adenomatous polyps in the duodenum and to perform<br />

colon screening in these patients.<br />

With a bed capacity of 3600 patients and more than 300 endoscopic<br />

procedures carried out each day, our center has the title of largest<br />

institution in Turkey and one of the three largest institutes in all of<br />

Received: 20 December 2022; Accepted: 13 April <strong>2023</strong><br />

Published online: 15 April <strong>2023</strong><br />

References<br />

1. Hirota, W. K. et al. ASGE guideline: The role of endoscopy in<br />

the surveillance of premalignant conditions of the upper GI tract.<br />

Gastrointest. Endosc. 63, 570 (2006).<br />

2. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee et al. Endoscopic mucosal<br />

tissue sampling. Gastrointest. Endosc. 78, 216 (2013).<br />

3. Vadva, M. D. & Triadafilopoulos, G. Glycogenic acanthosis of the<br />

esophagus and gastroesophageal reflux. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 17,<br />

79 (1993).<br />

4. Ghahremani, G. G. & Rushovich, A. M. Glycogenic acanthosis of<br />

the esophagus: Radiographic and pathologic features. Gastrointest.<br />

Radiol. 9, 93 (1984).<br />

5. Stern, Z. et al. Glycogenic acanthosis of the esophagus. A benign<br />

but confusing endoscopic lesion. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 74, 261<br />

(1980).<br />

6. Sablich, R., Benedetti, G., Bignucolo, S. & Serraino, D. Squamous<br />

cell papilloma of the esophagus. Report on 35 endoscopic cases.<br />

Endoscopy 20, 5 (1988).<br />

7. Szántó, I. et al. Squamous papilloma of the esophagus. Clinical and<br />

pathological observations based on 172 papillomas in 155 patients.<br />

Orv. Hetil. 146, 547 (2005).<br />

8. Carr, N. J., Monihan, J. M. & Sobin, L. H. Squamous cell papilloma<br />

of the esophagus: A clinicopathologic and follow-up study of 25<br />

cases. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 89, 245 (1994).<br />

9. Mosca, S. et al. Squamous papilloma of the esophagus: Long-term<br />

follow up. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16, 857 (2001).<br />

10. LiVolsi, V. A. & Perzin, K. H. Inflammatory pseudotumors<br />

(inflammatory fibrous polyps) of the esophagus. A clinicopathologic<br />

study. Am. J. Dig. Dis. 20, 475 (1975).<br />

11. Guelrud, M., Herrera, I. & Eggenfeld, H. Compact parakeratosis of<br />

esophageal mucosa. Gastrointest. Endosc. 51, 329 (2000).<br />

12. Lee, R. G. Adenomas arising in Barrett’s esophagus. Am. J. Clin.<br />

Pathol. 85, 629 (1986).<br />

13. Wong, R. S. et al. Multiple polyposis and adenocarcinoma arising in<br />

Barrett’s esophagus. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 61, 216 (1996).<br />

14. Adoke, K. U. et al. Hyperplastic polyps of the esophagus and<br />

esophagogastric junction with esophageal constriction—a<br />

case report. Pathology 46(Supplement 2), S81. https://doi.<br />

org/10.1097/01.PAT.0000454378.95070.60 (2014).<br />

15. Saers, T., Parusel, M., Brockmann, M. & Krakamp, B.<br />

Lymphangioma of the esophagus. Gastrointest. Endosc. 62, 181<br />

(2005).<br />

10

FEATURE<br />

16. Sivero, L. et al. Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of<br />

neuroendocrine tumors of the digestive system. Open Med. 11(1),<br />

369–373. https://doi.org/10.1515/med-2016-0067 (2016).<br />

17. Witteman, B. J., Janssens, A. R., Griffioen, G. & Lamers, C. B.<br />

Villous tumours of the duodenum. An analysis of the literature with<br />

emphasis on malignant transformation. Neth. J. Med. 42, 5 (1993).<br />

18. Levine, J. A., Burgart, L. J., Batts, K. P. & Wang, K. K. Brunner’s<br />

gland hamartomas: Clinical presentation and pathological features<br />

of 27 cases. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 90, 290–294 (1995).<br />

19. Noguchi, H. et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection rate<br />

in heterotopic gastric mucosa in histological analysis of duodenal<br />

specimens from patients with duodenal ulcer. Histol. Histopathol.<br />

35(2), 169–176. https://doi.org/10.14670/HH-18-142 (2020)<br />

(Epub 2019 Jul 2).<br />

20. Singhal, S. et al. Anorectal gastrointestinal stromal tumor: A case<br />

report and literature review. Case Rep. Gastrointest. Med. 2013,<br />

934875 (2013).<br />

21. Modlin, I. M., Lye, K. D. & Kidd, M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715<br />

carcinoid tumors. Cancer 97, 934–959 (2003).<br />

22. Bulur, A. et al. Polypoid lesions detected in the upper<br />

gastrointestinal endoscopy: A retrospective analysis in 19560<br />

patients, a single-center study of a 5-year experience in Turkey.<br />

N. Clin. Istanb. 8(2), 178–185. https://doi.org/10.14744/<br />

nci.2020.16779 (2020).<br />

23. Kostiainen, S., Teppo, L. & Virkkula, L. Papilloma of the<br />

oesophagus. Report of a case. Scand. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc.<br />

Surg. 7(1), 95–97. https://doi.org/10.3109/14017437309139176<br />

(1973).<br />

24. Mandard, A. M. et al. Cancer of the esophagus and associated<br />

lesions: Detailed pathologic study of 100 esophagectomy<br />

specimens. Hum. Pathol. 15, 660 (1984).<br />

25. Levine, J. A., Burgart, L. J., Batts, K. P. & Wang, K. K. Brunner’s<br />

gland hamartomas: Clinical presentation and pathological features<br />

of 27 cases. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 90(2), 290–294 (1995).<br />

26. Ma, M. X. & Bourke, M. J. Management of duodenal polyps. Best<br />

Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 31(4), 389–399 (2017).<br />

Author contributions<br />

Ç.E., M.Y.: conception, design, supervision, materials, data collection<br />

and processing, analysis and interpretation, literature review, writer<br />

and critical review. D.A., B.Y., K.K. O.C., İ.T., H.T.K.: materials, data<br />

collection and processing, analysis and interpretation, literature review<br />

and manuscript supervision.<br />

Competing interests<br />

The authors declare no competing interests.<br />

Additional information<br />

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Ç.E.<br />

Reprints and permissions information is available at<br />

www.nature.com/reprints.<br />

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to<br />

jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.<br />

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons<br />

Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing,<br />

adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as<br />

long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source,<br />

provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes<br />

were made. The images or other third party material in this article are<br />

included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated<br />

otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the<br />

article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted<br />

by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to<br />

obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this<br />

licence, visit http:// creat iveco mmons. org/ licen ses/ by/4. 0/.<br />

© The Author(s) <strong>2023</strong><br />

WHY NOT WRITE FOR US?<br />

<strong>Gastroenterology</strong> <strong>Today</strong> welcomes the submission of<br />

clinical papers and case reports or news that<br />

you feel will be of interest to your colleagues.<br />

Material submitted will be seen by those working within all<br />

UK gastroenterology departments and endoscopy units.<br />

All submissions should be forwarded to info@mediapublishingcompany.com<br />

If you have any queries please contact the publisher Terry Gardner via:<br />

info@mediapublishingcompany.com<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SUMMER <strong>2023</strong><br />

11

FEATURE<br />

Stronger Together<br />

Cantel, Key Surgical and Diagmed are now part of STERIS.<br />

Our companies share a commitment to provide the very best<br />

solutions for our Customers and we are excited to bring the<br />

power of our teams together, and to provide a more extensive<br />

and innovative suite of offerings to new and existing<br />

Customers around the world.<br />

The unique strength of our collective organisation will continue<br />

to uphold our mission of HELPING OUR CUSTOMERS CREATE<br />

A HEALTHIER AND SAFER WORLD.<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SUMMER <strong>2023</strong><br />

Come join us<br />

at BSG!<br />

Stand A26<br />

The Arena<br />

12<br />

www.steris.com

FEATURE<br />

EVALUATION OF GUT MICROBIOTA OF IRANIAN<br />

PATIENTS WITH CELIAC DISEASE, NON-CELIAC WHEAT<br />

SENSITIVITY, AND IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME:<br />

ARE THERE ANY SIMILARITIES?<br />

Kaveh Naseri 1 , Hossein Dabiri 2 , Meysam Olfatifar 3 , Mohammad Amin Shahrbaf 4 , Abbas Yadegar 5 , Mona Soheilian‐Khorzoghi 4 ,<br />

Amir Sadeghi 4 , Saeede Saadati 4 , Mohammad Rostami‐Nejad 4* , Anil K. Verma 6 and Mohammad Reza Zali 4<br />

Naseri et al. BMC <strong>Gastroenterology</strong> (<strong>2023</strong>) 23:15 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-023-02649-y<br />

Abstract<br />

Introduction<br />

Background and aims<br />

Individuals with celiac disease (CD), non-celiac wheat sensitivity<br />

(NCWS), and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), show overlapping clinical<br />

symptoms and experience gut dysbiosis. A limited number of studies so<br />

far compared the gut microbiota among these intestinal conditions. This<br />

study aimed to investigate the similarities in the gut microbiota among<br />

patients with CD, NCWS, and IBS in comparison to healthy controls<br />

(HC).<br />

Materials and methods<br />

In this prospective study, in total 72 adult subjects, including CD (n = 15),<br />

NCWS (n = 12), IBS (n = 30), and HC (n = 15) were recruited. Fecal<br />

samples were collected from each individual. A quantitative real-time<br />

PCR (qPCR) test using 16S ribosomal RNA was conducted on stool<br />

samples to assess the relative abundance of Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes,<br />

Bifidobacterium spp., and Lactobacillus spp.<br />

Results<br />

In all groups, Firmicutes and Lactobacillus spp. had the highest and<br />

lowest relative abundance respectively. The phylum Firmicutes had<br />

a higher relative abundance in CD patients than other groups. On<br />

the other hand, the phylum Bacteroidetes had the highest relative<br />

abundance among healthy subjects but the lowest in patients with<br />

NCWS. The relative abundance of Bifidobacterium spp. was lower in<br />

subjects with CD (P = 0.035) and IBS (P = 0.001) compared to the HCs.<br />

Also, the alteration of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio (F/B ratio) was<br />

statistically significant in NCWS and CD patients compared to the HCs<br />

(P = 0.05).<br />

Conclusion<br />

The principal coordinate analysis (PCoA), as a powerful multivariate<br />

analysis, suggested that the investigated gut microbial profile of patients<br />

with IBS and NCWS share more similarities to the HCs. In contrast,<br />

patients with CD had the most dissimilarity compared to the other<br />

groups in the context of the studied gut microbiota.<br />

Keywords<br />

Celiac disease, Irritable bowel syndrome, Non-celiac wheat sensitivity,<br />

Gut microbiota, Dysbiosis<br />

The human gastrointestinal (GI) tract harbors an incredibly complex<br />

and abundant ensemble of microbes referred to as gut microbiota<br />

[1]. Gut microbiota plays a pivotal role in human health and<br />

diseases [2–4] and its composition depends on various factors,<br />

including age [5], diet [6], geography [7], malnourishment [8], race,<br />

ethnicity [9], and socioeconomic status [10]. Balance in the gut<br />

microbiota composition and the presence or absence of critical<br />

species capable of causing specific responses contribute to<br />

ensuring homeostasis in the intestinal mucosa and other organs<br />

[11–14]. An imbalanced or disturbed composition and quantity<br />

of the gut microbiota, known as dysbiosis [15], can affect the<br />

bacterial function and is associated with a variety of GI disorders<br />

[16–20]. Celiac disease (CD), non-celiac wheat sensitivity (NCWS),<br />

and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), have intestinal dysbiosis as<br />

a causative factor in the initiation of their symptoms [21–24].<br />

CD is a chronic small intestinal inflammation, triggered by the<br />

consumption of gluten, resulting in villous atrophy in genetically<br />

susceptible individuals [25]. IBS is a functional gastrointestinal<br />

disorder that afflicts nearly 15% of the population worldwide,<br />

characterized by recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort, and<br />

changes in bowel habits, in the absence of any other disease to<br />

cause these symptoms [26, 27]. NCWS is still an unclear diagnosis,<br />

characterized by a combination of CD-like or IBS-like symptoms<br />

(e.g., diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating), behavior disturbances,<br />

and systemic manifestations, related to the ingestion of gluten in<br />

subjects who are not affected by either CD or wheat allergy [28,<br />

29]. Therefore, since these three disorders are related to dysbiosis<br />

in gut microbiota and share similarities in their symptoms, these<br />

data form a hypothesis regarding the possible similarities in the<br />

alterations of the gut microbiota in subjects with the aforementioned<br />

disorders. Although the findings are inconsistent, previous<br />

studies mainly reported decreased levels of fecal Lactobacilli and<br />

Bifidobacteria, and increased ratios of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes<br />

in patients with IBS when compared to healthy individuals [21, 30–<br />

32]. According to most studies conducted on the gut microbiota of<br />

CD patients, Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli levels are decreased in<br />

comparison to healthy controls [22, 33, 34]. Due to NCWS being a<br />

relatively new diagnosis, few studies have examined gut microbiota<br />

in this group.<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SUMMER <strong>2023</strong><br />

* Correspondence: Mohammad Rostami‐Nejad<br />

m.rostamii@gmail.com<br />

© The Author(s) <strong>2023</strong>.<br />

13

FEATURE<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SUMMER <strong>2023</strong><br />

14<br />

To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have investigated<br />

the possible similarities in the gut microbiota profile of patients with CD,<br />

NCWS, and IBS compared to healthy control. Hence, we designed this<br />

monocentric prospective observational study to compare the relative<br />

abundance of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, as the two most dominant<br />

phyla [35–38], and Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, as two highly<br />

controversial genera of fecal microbial communities, among Iranian<br />

subjects with CD, NCWS, and IBS compared to HCs.<br />

Materials and methods<br />

Study population<br />

From March 2020 to November 2020, consecutive newly diagnosed<br />

CD, NCWS, and IBS patients were recruited from an outpatient<br />

gastroenterology clinic in Taleghani Hospital, Tehran, Iran. Convenience<br />

sampling was used for participants’ selection. Subjects who had<br />

recently been diagnosed with CD, NCWS, and IBS, and were not<br />

on therapeutic diets such as gluten-free or low-FODMAP diets or<br />

taking supplements such as probiotics, prebiotics, or synbiotics were<br />

considered as patients groups. CD diagnosis was established according<br />

to the “4 out of 5” rule and four of the following criteria were considered<br />

sufficient for disease diagnosis: typical CD related symptoms, positivity<br />

of CD-specific antibodies, HLA-DQ2 or 8 genotypes, intestinal damages<br />

at duodenal biopsy and clinical response to GFD [39]. Twelve patients<br />

with NCWS that fulfilled the Salerno consensus criteria [40] were<br />

included. All NCWS subjects demonstrated negative serology results for<br />

tissue-transglutaminase IgA antibodies, and the duodenal biopsy results<br />

were normal [41].<br />

IBS diagnosis was based on fulfilling the ROME-IV criteria [27], including<br />

recurrent abdominal pain at least one day per week over the previous<br />

3 months, along with two or more of the following criteria: (a) changes<br />

in defecation, (b) changes in frequency, and (c) changes in the form of<br />

stool, with no medication to alleviate symptoms in the last 3 months.<br />

Anti-Tissue Trans-glutaminase (Anti-tTG) and/or endomysial antibodies<br />

(EMA), histological findings compatible with atrophy (according to the<br />

Marsh classification), and wheat-specific Immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels<br />

were negative in all thirty patients with IBS. Apart from these, fifteen<br />

healthy volunteers, with no history of digestive pathologies lacking<br />

CD-specific antibodies, were enrolled in the healthy control (HC)<br />

group. These HCs had normal bowel movements without abdominal<br />

symptoms, coronary artery disease, inflammatory conditions, IBS,<br />

NCWS, and diabetes mellitus.<br />

Pregnant and lactating women, individuals with any systemic<br />

inflammatory diseases like autoimmune conditions, gastrointestinal<br />

diseases (i.e. inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)) or any other acute<br />

or chronic diseases, gastrointestinal surgery, cancer, and those who<br />

were not willing to participate in the study were excluded from all<br />

study groups. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) usage,<br />

excessive alcohol consumption, systemic use of immunosuppressive<br />

agents, poorly controlled psychiatric diseases and the history of broadspectrum<br />

antibiotics and probiotics consumption were also considered<br />

as exclusion criteria. Participants were also asked not to take any<br />

antibiotics, eat spicy food, and smoke four weeks prior to sample<br />

collection.<br />

Fecal samples collection and homogenization<br />

Fresh early-morning fecal samples, representative of whole gut<br />

microbiome, were collected from each participant in sterile fecal<br />

specimen containers at the study’s baseline. A water ban was also<br />

required after midnight and before collecting the samples in the morning.<br />

Stool specimens were collected and handled by experienced clinicians<br />

and trained technicians. Homogenization of the stool samples was<br />

conducted through agitation by using a vortex. Afterward, stool samples<br />

were divided into three aliquots within 3 h of defecation. Using screwcapped<br />

cryovial containers, the aliquots were immediately frozen and<br />

stored at − 80 °C until used for DNA extraction [42].<br />

DNA extraction from fecal samples<br />

QIAamp ® DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen Retsch GmbH, Hannover,<br />

Germany) was used for DNA extraction [43]. DNA concentration was<br />

quantified by NanoDrop ND-2000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop<br />

products, Wilmington, DE, USA). In addition, Nanodrop (DeNovix<br />

Inc., USA) was used for assessing the concentration and purity of the<br />

extracted DNA. Extracted DNA samples were stored at − 20 °C until<br />

further analysis.<br />

Microbiota analysis by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)<br />

We performed qPCR assay to evaluate the relative abundance of two<br />

bacterial phyla, including Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, and two genera,<br />

including Bifidobacterium spp. and Lactobacillus spp. The qPCR was<br />

conducted by SYBR Green chemistry using universal and group-specific<br />

primers based on the bacterial 16S rRNA sequences presented in<br />

Additional file 1: Table S1. All PCRs were performed in a volume of 25<br />

μL, comprising 12.5 μL of SYBR green PCR master mix (Ampliqon,<br />

Odense, Denmark), 1 μL of 10 pmol of forward, and reverse primers,<br />

and 100 ng of the DNA template.<br />

Rotor-Gene ® Q (Qiagen, Germany) real-time PCR system was used<br />

for the PCR amplification. The amplification reaction parameters were<br />

assumed as 95 °C for 10 min and 40 cycles at 95 °C for 20 and 30 s for<br />

each primer (Additional file 1: Table S1) and 72 °C for the 20 s. Melting<br />

curve analysis was conducted to assess the amplification accuracy by<br />

increasing temperature from 60 to 95 °C (0.5 °C increase in every 5 s).<br />

The relative abundance of studied taxa was evaluated based on the ratio<br />

of the 16S rRNA copy number of the specific bacteria to the total 16S<br />

rRNA copy number of all bacteria using the previously described method<br />

[32]. Accordingly, the average Ct value for primers was reported as the<br />

percentage values using the following formula:<br />

univ<br />

(Eff. Univ)Ct<br />

Χ =<br />

(Eff. Spec)<br />

Ct spec<br />

×100<br />

The percentage of 16S taxon-specific copy numbers was indicated by<br />

“X”. Furthermore, “Eff. Univ” and “Eff. Spec” represents the efficiency<br />

of the universal primers (2 = 100% and 1 = 0%) and the efficiency of the<br />

taxon-specific primers respectively. The threshold cycles registered by<br />

the thermocycler were indicated by “Ct univ” and “Ct spec”.<br />

Statistical analysis<br />

Analysis of collected data was performed using Statistical Package<br />

for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL,<br />

USA. Figures were drawn using GRAPHPAD Prism 8.4.0 (GraphPad<br />

Software, Inc, San Diego, CA). Quantitative variables were reported as

FEATURE<br />

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of study participants at enrollment<br />

Variables HC (n = 15) IBS (n = 30) NCWS (n = 12) CD (n = 15) Total (n = 72) P‐value*<br />

Table Age (years) 1 Baseline characteristics 32.8 ± 12.2 of study 37.8 participants ± 10.7 at enrollment 31.8 ± 6.4 40.1 ± 8.2 35.5 ± 6.4 0.76<br />

Variables<br />

Males (n%)<br />

HC<br />

7 (46.7%)<br />

(n = 15) IBS<br />

15 (50%)<br />

(n = 30) NCWS<br />

5 (41.7%)<br />

(n = 12) CD<br />

6 (50%)<br />

(n = 15) Total<br />

33 (45.8%)<br />

(n = 72) P‐value*<br />

0.83<br />

Females (n%) 8 (53.3%) 15 (50%) 7 (58.3%) 6 (50%) 39 (54.2%) 0.45<br />

Age Smoking (years) (n%) 32.8 4 (26.6%) ± 12.2 37.8 9 (30%) ± 10.7 31.8 4 (33.3%) ± 6.4 40.1 2 (13.3%) ± 8.2 35.5 19 (26.4%) ± 0.76 0.65<br />

Males (n%) 7 (46.7%) 15 (50%) 5 (41.7%) 6 (50%) 33 (45.8%) 0.83<br />

HC, healthy control; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; NCWS, non-celiac wheat sensitivity; CD, celiac disease<br />

Females (n%) 8 (53.3%) 15 (50%) 7 (58.3%) 6 (50%) 39 (54.2%) 0.45<br />

*P-values obtained by Kruskal–Wallis test<br />

Smoking (n%) 4 (26.6%) 9 (30%) 4 (33.3%) 2 (13.3%) 19 (26.4%) 0.65<br />

HC, healthy control; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; NCWS, non-celiac wheat sensitivity; CD, celiac disease<br />

*P-values obtained by Kruskal–Wallis test<br />

mean ± standard deviation (SD) and qualitative variables were reported statistically significant (p = 0.002). Whereas the phylum Bacteroidetes<br />

as numerical (%) data. ANOVA test was used for the assessment of the was significantly lower in patients with IBS (P = 0.049) and NCWS<br />

relative abundance differences between the two phyla. In addition, we (P = 0.006). This phylum had the lowest relative abundance in the<br />

used R software and Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) method to NCWS group (7.3 ± 4.0%). In addition, the relative abundance of<br />

assess dissimilarities in this study. The PCoA was calculated based on Bifidobacterium spp. was statistically lower in subjects with CD<br />

the Bray Curtis dissimilarity method [44].<br />

(P = 0.022) and IBS (P = 0.001); with the lowest percentage in the IBS<br />

group (0.5 ± 0.5). Moreover, Lactobacillus spp. was significantly lower<br />

Results<br />

in subjects with CD (P = 0.022) and IBS (P = 0.007) compared to the<br />

HCs. The relative abundance of this genus was also lower in subjects<br />

with NCWS, though not statistically significant (P = 0.12). The results<br />

Demographics<br />

Seventy-two samples from adult participants were enrolled in this<br />

study. Due to age-related changes in the gut microbiota, the study<br />

groups were adjusted according to their age so as not to have<br />

for the relative abundance are presented in Table 2 and Fig. 1. As<br />

shown in Table 2 the results obtained from the Kruskal–Wallis test also<br />

revealed significant inter-groups differences for all the studied bacteria<br />

(p

FEATURE<br />

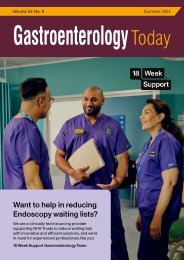

Fig. 1 Box plot for the distribution of the selected bacterial taxa by the median abundance that constitutes the fecal microbiota in each group of<br />

the study population. Differences in each group of the patients were compared to the healthy control (HC) and were considered to be statistically<br />

significant when *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SUMMER <strong>2023</strong><br />

16<br />

Discussion<br />

The current study examined fecal samples from adult participants<br />

with three GI disorders, including CD, NCWS, and IBS. Comparing<br />

gut dysbiosis to healthy controls, the microbiota analysis interestingly<br />

showed a significant difference in the relative abundance of Firmicutes,<br />

Bacteroidetes, Bifidobacterium spp., and Lactobacillus spp. in<br />

CD patients. In addition, the analysis of the relative abundance of<br />

Bifidobacterium spp. and Lactobacillus spp. in IBS patients and<br />

Bacteroidetes in NCWS revealed a statistically significant decrease<br />

compared to the HC group. Furthermore, Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes<br />

ratio (F/B ratio) assessment, as a valuable index for detecting the<br />

alterations in gut microbiota, was another aim of the current study.<br />

Changes in the F/B ratio could be particularly important. Firmicutes and<br />

Bacteroidetes are two predominant phyla accounting for up to 90%<br />

of the total gut microbiota composition [45]. The F/B ratio has been<br />

suggested as an important index of gut microbiota health. [46]. This<br />

ratio is associated with different pathological states [47]. For instance,<br />

the association of a high F/B ratio with several conditions including<br />

GI disorders has been observed repeatedly [48–50]. Particularly, it<br />

is associated with the production of short-chain fatty acids such as<br />

butyrate and propionate [51]. Short-chain fatty acids generated by<br />

microbiota can have a significant influence on human health. The antiinflammatory<br />

molecule butyrate, in particular, acts both on enterocytes<br />

and circulating immune cells, regulating gut barrier integrity. Additionally,<br />

propionate production plays a crucial role in human health since it<br />

promotes satiety and prevents hepatic lipogenesis, which in turn lowers<br />

cholesterol production [52, 53]. Moreover, the increased F/B ratio is<br />

associated with an increased energy harvest from colonic fermentation<br />

[54]. According to our analysis, the F/B ratio was significantly higher in<br />

the subjects with CD and NCWS than in the HCs. In contrast, it was<br />

not statistically significant in subjects with IBS, suggesting a higher level<br />

of alteration in the gut microbiota of individuals with CD and NCWS<br />

than in the IBS compared to the HCs. Recent studies suggested that<br />

the alteration of gut microbiota composition is associated with CD<br />

pathogenesis [55–57]. In the study of Golfetto et al., the concentration<br />

of Bifidobacterium spp. in CD patients was significantly lower compared<br />

to the HCs [58]. Another study conducted by Bodkhe et al., reported<br />

that Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes were the major phyla in the duodenal<br />

microbiota of subjects with CD [59]. Several other studies have<br />

demonstrated that Bifidobacterium spp. and Lactobacillus spp. protect<br />

the intestinal epithelial cells from gliadin damage [60,61,62]. Accordingly,<br />

it has been suggested that the fecal transplant which can cause an<br />

increment in Bifidobacterium spp. could reverse the inflammatory<br />

pathway in CD patients [63]. Among all the groups we studied,<br />

Firmicutes predominated the gut microbiota. In addition, Bacteroidetes,

FEATURE<br />

Bifidobacterium spp., and Lactobacillus spp. had significantly lower<br />

abundance in subjects with CD compared to the HCs. In terms of the<br />

alteration and relative abundance of the studied bacterial groups, the<br />

current study’s results were largely consistent with the previous reports.<br />

Fig. 2 Box plots showing the Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes (F/B) I each<br />

group of participants. This ratio was significantly (*P = 0.05) increased<br />

in the NCWS and CD patients but non‐significant in the IBS patients<br />

compared with the healthy controls (HC)<br />

Gut microbiota dysbiosis in individuals with IBS has been reported<br />

in several studies [64–66]. In fact, gastrointestinal dysbiosis in these<br />

patients is associated with intestinal hypersensitivity, mucosal immune<br />

activation, and chronic inflammation, which are the three important<br />

pathophysiological factors in this disease [67, 68]. A number of studies<br />

have reported lower amounts of Bacteroidetes and higher amounts of<br />

Firmicutes in subjects with IBS compared to HCs [32, 69, 70]. In the<br />

current study, both of these phyla had lower relative abundances than<br />

those of HCs, although their differences were not statistically significant.<br />

Furthermore, it has been suggested that IBS is associated with the<br />

lower relative abundance of Bifidobacterium spp. and Lactobacillus<br />

spp. [71, 72] which is in accordance with the current study. However, it<br />

is noteworthy that Maccaferri et al. observed an increase in the relative<br />

abundance of Bifidobacterium spp. and Lactobacillus among subjects<br />

with IBS [73]. It seems that further evidence is needed to confirm<br />

these results. As for NCWS, dysbiosis in these individuals is one of<br />

the important issues which can cause constipation, diarrhea, chronic<br />

inflammation, intestinal hypersensitivity, and immune dysfunction [74].<br />

Fig. 3 Shepherd plot showing the correlation between the distance from the dissimilarity matrix and the coordination distance for NMDS analysis<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SUMMER <strong>2023</strong><br />

17

FEATURE<br />

Fig. 4 Bray–Curtis dissimilarity metric plotted in PCoA space comparing the microbial communities from different patient groups (CD, NCWS, IBS,<br />

and HC). Each circle representing a participant colored according to the studied group<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SUMMER <strong>2023</strong><br />

18<br />

Garcia-Mazcorro et al. reported a high relative abundance of Firmicutes<br />

and a low relative abundance of Bacteroidetes in the fecal microbiota<br />

of the individuals with NCWS [75]. According to the current study,<br />

the Phylum Bacteroidetes was significantly lower in NCWS patients<br />

compared to HCs, in agreement with the previous study.<br />

Analysis of the dissimilarity and PCoA in this study suggests that<br />

individuals with CD experience a higher level of dysbiosis compared to<br />

the other subjects with microbiota-related GI disorders. In fact, fewer<br />

similarities were observed in the studied bacterial profile of subjects<br />

with IBS and those with NCWS. Overall, it may explain why this<br />

disorder exhibits more severe symptoms when compared to the other<br />

GI disorders, suggesting that the recovery of gut microbiota should be<br />

emphasized more in the treatment of this disease. According to these<br />

analyses, the composition of the gut microbiota in the subjects with IBS<br />

and NCWS is more similar to that of the HCs’, which may suggest a<br />

more favorable outcome for IBS and NCWS than for CD.<br />

The present study had some limitations. First, the sample size is not<br />

large enough to extrapolate the results. Actually, the present study has<br />

monocentric nature that was conducted in a limited population with<br />

specific features. Even if this matter has been addressed with bigger<br />

sample sizes, the results cannot be generalized from one population<br />

to others. Second, based on the meta-genomic data, the human gut<br />

microbiome may contain more than 1000 bacterial species. Although<br />

the studied bacterial phyla and genera are the most dominant and<br />

critical taxonomical groups, there are other groups that should be taken<br />

into consideration. Third, alimentary habits of the included subjects,<br />

which can consistently modify gut microbiota, were not assessed in the<br />

current study. Considering the fact that, eating habits such as using fiber<br />

sub-types, food additives, ultra-processed foods and etc. can affect the<br />

gut bacteria composition, performing further similar microbiota studies<br />

evaluating patients’ dietary pattern is highly recommended. Moreover,<br />

the lack of a follow-up of patients and comparison of results before and<br />

after receiving treatment is another important limitation.<br />

To our knowledge, no previous publication has compared the gut<br />

microbiota profile of subjects with CD, NCWS, and IBS. In fact,<br />

the potential overlap between NCWS and IBS diagnosis and the<br />

unavailability of gluten challenge tests in many medical centers make it<br />

difficult to explore the gut microbiota among these groups. Thus, this<br />

study represents promising findings for future research. Additionally,<br />

investigating all components of the gut microbiota including bacteria,<br />

viruses, fungi, and archaea in order to identify microbial patterns,

FEATURE<br />

conducting multi-centric studies, and examining the fecal microbiome<br />

and mucosal microbiome simultaneously to have a better perspective on<br />

the differences between the mucosal microbiome and fecal microbiome<br />

would have been of great importance.<br />

Consent for publication<br />

Not applicable.<br />

Competing interests<br />

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.<br />

Conclusion<br />

Results of our study indicate that the human intestinal microbiota<br />

composition differs across the studied groups with different microbiotarelated<br />

GI disorders. Specifically, patients with CD had the highest<br />

level of dissimilarity compared to the other studied groups with GI<br />

disorders and HCs. In contrast, those with IBS had the lowest level of<br />

dissimilarity with HCs. This study found some microbial changes that<br />

were inconsistent with the previous results, possibly due to genetics,<br />

geographical pattern, ethnicity, or diet.<br />

Supplementary Information<br />

The online version contains supplementary material available at<br />

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-023-02649-y.<br />

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 1. The taxon-specific primers<br />

used in this study.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

The authors wish to thank the laboratory staffs of the Foodborne<br />

and Waterborne Diseases Research Center, Research Institute for<br />

<strong>Gastroenterology</strong> and Liver Diseases, Shahid Beheshti University of<br />

Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, specially Ms. Masoumeh Azimirad and<br />

Ms. Nastaran Asri for their sincere assistance.<br />

Author contributions<br />

KN, SS, and MSK collected the samples and KN performed the<br />

real-time PCR analysis; MRN and HD designed and supervised the<br />

study; KN and MO participated in data analysis; KN, and MAS wrote<br />

the manuscript; MRN, AY, AS, HD, AKV, and MRZ critically revised the<br />

manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.<br />

Funding<br />

<strong>Gastroenterology</strong> and Liver Diseases Research Center, Research<br />

Institute for <strong>Gastroenterology</strong> and Liver Diseases, Shahid Beheshti<br />

University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, supported the study.<br />

Availability of data and materials<br />

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available<br />

from the corresponding author on reasonable request.<br />

Declarations<br />

Ethics approval and consent to participate<br />

The study protocol was submitted for evaluation and approval to the Ethical<br />

Review Committee of the Research Institute for <strong>Gastroenterology</strong> and Liver<br />

Diseases, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences to ensure that it<br />

meets ethical standards and guidelines. The present study was approved<br />

by mentioned Ethical Review Committee under the number IR.SBMU.<br />

RIGLD. REC.1396.154. The study was performed according to the revised<br />

Declaration of Helsinki 2013 [39] and informed consent was obtained from<br />

all subjects and/or their legal guardians prior to sample collection.<br />

Author details<br />

1<br />

School of Health and Biomedical Sciences, RMIT University, Melbourne,<br />

VIC, Australia. 2 Department of Microbiology, School of Medicine, Shahid<br />

Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. 3 <strong>Gastroenterology</strong><br />

and Hepatology Diseases Research Center, Qom University of Medical<br />

Sciences, Qom, Iran. 4 Celiac Disease Department, <strong>Gastroenterology</strong> and<br />

Liver Diseases Research Center, Research Institute for <strong>Gastroenterology</strong><br />

and Liver Diseases, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences,<br />