NCC Magazine Spring 2023

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

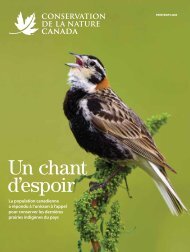

SPRING <strong>2023</strong><br />

Songs<br />

of<br />

hope<br />

A chorus of<br />

Canadians has<br />

joined the call<br />

to conserve<br />

our remaining<br />

native prairie<br />

grasslands

SPRING <strong>2023</strong><br />

CONTENTS<br />

Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

4 Our aim is true<br />

The power of partnership is essential to<br />

hitting Canada’s conservation targets.<br />

6 Dutch Creek Hoodoos<br />

These hoodoos in BC’s Columbia<br />

Valley offer a stunning view over<br />

an important wildlife corridor.<br />

7 Build a bee garden<br />

Four tips to help bees.<br />

7 Ripple effects<br />

For Catherine Stewart, Canada’s<br />

Ambassador for Climate Change,<br />

water nourishes mind and body.<br />

8 A gift for the Prairies<br />

The Weston Family Prairie Grasslands<br />

Initiative is empowering ranchers to<br />

conserve native prairie habitat.<br />

12 All smiles<br />

Keep your eyes open for the<br />

“smiling” Blanding’s turtle.<br />

14 Telling it like it is<br />

Aerin Jacob, <strong>NCC</strong>’s director of<br />

conservation science and research,<br />

on big thinking and genuine<br />

communication in conservation.<br />

16 Project updates<br />

Expanding protection on The<br />

Rock; ensuring a tall grass legacy;<br />

conservation, education and<br />

science unite; receiving high honours.<br />

18 A dance to remember<br />

Brian Keating on the spellbinding<br />

dance of the sharp-tailed grouse.<br />

Digital extras<br />

Check out our online magazine page with<br />

additional content to supplement this issue,<br />

at nccmagazine.ca.<br />

Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

245 Eglinton Ave. East, Suite 410 | Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 3J1<br />

magazine@natureconservancy.ca | Phone: 416.932.3202 | Toll-free: 877.231.3552<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) is the country’s unifying force for nature. We seek<br />

solutions to the twin crises of rapid biodiversity loss and climate change through large-scale,<br />

permanent land conservation. <strong>NCC</strong> is a registered charity. With nature, we build a thriving world.<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada <strong>Magazine</strong> is distributed to donors and supporters of <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

TM<br />

Trademarks owned by the Nature Conservancy of Canada.<br />

FSC is not responsible for any calculations on<br />

saving resources by choosing this paper.<br />

Printed on Enviro100 paper, which contains 100% post-consumer fibre, is EcoLogo, Processed Chlorine Free<br />

certified and manufactured in Canada by Rolland using biogas energy. Printed in Canada with vegetable-based<br />

inks by Warrens Waterless Printing. This publication saved 183 trees and 60,762 litres of water*.<br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

GENERATED BY: CALCULATEUR.ROLLANDINC.COM. PHOTO: LETA PEZDERIC. COVER: DAVID SEIBEL.<br />

*<br />

2 FALL 2022 natureconservancy.ca

McIntyre Ranch, Alberta.<br />

Featured<br />

Contributors<br />

Dear friends,<br />

KEVIN TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

TENEYCKE: BRIAN YUNGBLUT PHOTOGRAPHY. ALBERT LAW: SACHIN KHONA. JULIE BARNES: MATT RAMAGE/STUDIO D.<br />

Ihave been privileged to experience our country’s vast and<br />

open grasslands — seas of gold and green, where blades of<br />

grass sway in the gentle breeze. Prairie wildflowers add pops<br />

of colour to the rolling plains. The wafts of fragrant prairie sage<br />

make you feel that this is the world’s biggest herb garden. These<br />

are my favourite things about the Canadian prairies, which both<br />

captivate and sustain. I have experienced this amazing landscape<br />

and my children have, too, but I worry that their children may<br />

never experience these same opportunities.<br />

In my 20 years of delivering conservation programming, I’ve<br />

seen a wave of change — even in just the last decade — that has<br />

enabled us to work toward innovative solutions that are compatible<br />

with conservation and livestock producers.<br />

When conservation groups collaborate with donors and supporters,<br />

we can provide ranchers with the financial resources to do<br />

things that increase the quality of grasslands, like rotational grazing.<br />

Meaningful changes like these take a whole-of-society approach<br />

to conservation.<br />

In this issue’s feature story, you’ll read about the Stewardship<br />

Investment Program, funded through the Weston Family Prairie<br />

Grasslands Initiative — the largest ever private investment in<br />

conserving Canada’s grasslands. This program is a great example<br />

of society’s collective effort to protect habitat and the species<br />

that depend on them.<br />

At the Nature Conservancy of Canada, we take to heart the<br />

belief that when nature thrives, people thrive. With the arrival<br />

of warmer weather, I invite you to reconnect with a part of nature<br />

that you love, learn about Canada’s grasslands and how you can<br />

lend a helping hand.<br />

Yours in conservation,<br />

Kevin Teneycke<br />

Kevin Teneycke<br />

Regional Vice President – Manitoba<br />

Julie Barnes is a<br />

freelance writer based<br />

in Saskatoon. She has<br />

written about travel,<br />

gardening, architecture,<br />

residential construction,<br />

food and agriculture,<br />

urban planning, cottage<br />

communities and<br />

education for a variety<br />

of publications and<br />

industry clients. She<br />

wrote “A gift for the<br />

grasslands,” page 8.<br />

Albert Law is a<br />

Vancouver-based<br />

editorial and commercial<br />

photographer.<br />

His work spans<br />

a broad range, from<br />

soft editorial portraits<br />

to photojournalism<br />

in austere conditions<br />

with the Canadian<br />

Armed Forces. He<br />

photographed Aerin<br />

Jacob for “Telling it<br />

like it is,” on page 14.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2023</strong> 3

COAST TO<br />

COAST<br />

2<br />

Our<br />

aim<br />

is true<br />

Extending support for Canada’s natural areas<br />

1<br />

3<br />

4<br />

Over the next three years, the Nature<br />

Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) will<br />

conserve an additional 130,000 hectares<br />

of priority natural habitat, thanks to the<br />

extension of the Natural Heritage Conservation<br />

Program (NHCP). With this support,<br />

along with matching funds from our partners<br />

and donors, <strong>NCC</strong>’s commitment will result<br />

in the protection of natural areas spanning<br />

roughly three times the size of Montreal. Since<br />

2007, the NHCP has matched more than<br />

$445 million in investment from the Government<br />

of Canada, with more than $875 million<br />

in non-federal funding to delivere more than<br />

$1.3 billion in conservation outcomes.<br />

The NHCP is designed to bring partners<br />

together to unlock conservation solutions.<br />

Working alongside other program partners,<br />

including Ducks Unlimited Canada, Wildlife<br />

Habitat Canada and the country’s land<br />

trusts, <strong>NCC</strong> will build upon the success of<br />

the program.<br />

The extended NHCP will help <strong>NCC</strong> find<br />

new and innovative ways to conserve more<br />

lands faster, including privately protected<br />

areas, publicly protected areas and conservation<br />

on working landscapes. <strong>NCC</strong> will also<br />

continue to support and advance Indigenous-led<br />

conservation, including Indigenous<br />

Protected and Conserved Areas.<br />

Lands protected and cared for by <strong>NCC</strong><br />

under the NHCP will provide benefits<br />

for species at risk and migratory birds, and<br />

ensure the health and connectedness of<br />

natural systems. They will provide opportunities<br />

for climate change mitigation and<br />

VIEW OUR SUCCESSES<br />

SINCE THE START OF THE<br />

NATURAL HERITAGE<br />

CONSERVATION PROGRAM<br />

adaptation, and maintain ecosystem services<br />

for neighbouring communities.<br />

These projects have the potential to<br />

capture at least 250,000 tonnes of carbon<br />

over the three-year term of the program<br />

extension, equivalent to taking 52,000 passenger<br />

vehicles off the road<br />

While much has been accomplished<br />

through this partnership, the urgency of the<br />

biodiversity and climate change crises demand<br />

that we do more to ensure a thriving<br />

world for nature and people.1<br />

LEFT TO RIGHT: CARYS RICHARDS; STEVE OGLE; JASON BANTLE; <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

4 WINTER SPRING <strong>2023</strong> natureconservancy.ca

HITTING THE MARK<br />

Contributions from the NHCP since 2007 have helped accomplish:<br />

90,000<br />

The total number of hectares of grasslands protected under<br />

the program, an area larger than the city of Calgary.<br />

480,000<br />

The total number of hectares of forested habitat conserved,<br />

an area three times larger than Gros Morne National Park.<br />

300,000<br />

The total number of hectares supported by stewardship activities.<br />

96<br />

The percentage of all NHCP properties within 25 kilometres<br />

of provincially or nationally protected areas, contributing to<br />

connectivity in these areas.<br />

10<br />

5<br />

8<br />

7<br />

9<br />

6<br />

LEFT TO RIGHT: ANDREW WARREN; KENAUK NATURE; MIKE DEMBECK;<br />

DENIS DUQUETTE; IRWIN BARRETT; ANDREW HERYGERS/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF.<br />

Key projects since 2007<br />

1. Darkwoods Conservation Area, BC<br />

Valleys, mountains, lake<br />

2. Birch River Wildland Provincial Park, AB<br />

Boreal forest<br />

3. Buffalo Pound, SK<br />

Native grasslands<br />

4. Douglas Marsh, MB<br />

Marsh wetlands, native upland prairie<br />

5. Boreal Wildlands, ON<br />

Boreal forest, rivers, streams<br />

6. Kenauk, QC<br />

Old-growth forests, wetlands, lakes<br />

7. Musquash Estuary Nature Reserve, NB<br />

Acadian forest, marshes<br />

8. Conway and Cascumpec<br />

Sandhills Nature Reserve, PE<br />

Sand dunes, wetlands<br />

9. Shaw Wilderness Park, NS<br />

Temperate forest, marshes<br />

10. Grand Codroy Estuary Nature Reserve, NL<br />

Boreal forest, marshes, wetlands<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2023</strong> 5

BOOTS ON<br />

THE TRAIL<br />

<br />

N<br />

Westside Road<br />

Dutch Creek<br />

Hoodoos<br />

Formed over thousands of years,<br />

these hoodoos offer a stunning view<br />

over an important wildlife corridor<br />

Dutch Creek<br />

Hoodoos<br />

Conservation<br />

Area<br />

The Hoodoos<br />

Dutch Creek<br />

The craggy spires and rugged cliffs of<br />

the Dutch Creek Hoodoos Conservation<br />

Area are a sight to behold. Looking<br />

much like a child’s sandcastle, the hoodoos<br />

formed over thousands of years of glaciation<br />

and erosion. The cliffs sit at the north end<br />

of Columbia Lake, in BC’s Rocky Mountain<br />

Trench in the territory of the Ktunaxa Nation<br />

and the Secwépemc (Shuswap Band). The<br />

trench is immensely important as a wildlife<br />

corridor. The Douglas-fir forest on the<br />

benchlands above the hoodoos provides<br />

prime habitat for many wildlife species,<br />

including mule deer and elk. The hoodoos<br />

themselves harbour precariously placed nests<br />

for white-throated swifts and violet-green<br />

swallows, while raptors circle on the updrafts<br />

looking for prey.<br />

The conservation area is a popular walking<br />

spot for locals and visitors alike. A wellgroomed<br />

trail leads through the forest to the<br />

bench above the hoodoos. From the top of the<br />

cliffs, visitors are treated to a stunning panoramic<br />

view of Columbia Lake and beyond.1<br />

LEGEND<br />

-- Dutch Creek Hoodoos Trail<br />

P Parking<br />

SPECIES TO SPOT<br />

• American badger<br />

• black bear<br />

• elk<br />

• golden eagle<br />

• mule deer<br />

• sharp-shinned hawk<br />

• violet-green swallow<br />

• white-throated swift<br />

LEARN MORE<br />

natureconservancy.ca/dutchcreek<br />

MAP: JACQUES PERRAULT. PHOTOS TOP TO BOTTOM: STEVE OGLE;<br />

STEVE OGLE; ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; STEVE OGLE; <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

6 SPRING <strong>2023</strong><br />

natureconservancy.ca

ACTIVITY<br />

CORNER<br />

BACKPACK<br />

ESSENTIALS<br />

Tips for a<br />

bee garden<br />

Four tips to help bees<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> has sprung, and the warming weather and<br />

thawing ground may just be the motivation you need<br />

for some yard improvements this year. While you’re<br />

getting your hands dirty, we invite you to take stock<br />

of what you can do to support bees. Native bees are<br />

best adapted to native plants, which often require<br />

less maintenance from us than ornamental varieties,<br />

and provide a higher quality food source for the bees.<br />

You don’t need an overhaul right away; you can make<br />

an impact by adding one or two native species a year.<br />

Here are a few tips for designing a bee garden:<br />

ILLUSTRATION: CORY PROULX. PHOTO: DOMINIC STEINMANN.<br />

1. CHOOSE PLANTS<br />

NATIVE TO YOUR<br />

REGION<br />

Refer to online sources,<br />

a plant guidebook<br />

for your region, or<br />

consult your local plant<br />

nursery for recommendations<br />

on bee-friendly<br />

plants that are native<br />

to your area. Planting<br />

a number of different<br />

species can provide<br />

nectar and pollen as<br />

food from spring to<br />

fall. Help foraging bees<br />

by providing their<br />

favourite plants in<br />

big patches.<br />

2. CREATE HABITAT<br />

FOR BEES<br />

Grow plants with<br />

hollow stems for<br />

cavity-nesting bees,<br />

like mason bees and<br />

carpenter bees. Come<br />

fall, leave any fallen<br />

plant material for bees<br />

and other pollinators<br />

to dwell in over winter.<br />

3. DESIGNATE A<br />

SUNSHINE SPOT<br />

Ground-nesting bees,<br />

such a sweat bees and<br />

mining bees, need loose<br />

and sparsely vegetated<br />

soil in a sunny location.<br />

Provide a patch of bare,<br />

dry and well-drained soil<br />

in a warm spot.<br />

4. ADD A PLACE TO<br />

QUENCH THIRST<br />

Provide a shallow dish of<br />

fresh, clean water, with<br />

partially submerged<br />

rocks as platforms for<br />

bees and other<br />

pollinators.1<br />

LEARN MORE<br />

Ripple effects<br />

For Catherine Stewart, Canada’s Ambassador for Climate<br />

Change, water nourishes mind and body<br />

Water has always been a big part of my life. Growing up on Lake Ontario,<br />

and later Rice Lake near Cobourg, Ontario, my early years spent lakeside<br />

gave me a deep appreciation for time spent in nature.<br />

At 17, I worked as an Ontario Junior Ranger, helping to maintain and clean Ontario<br />

provincial parks. It was a chance to connect with youth from across the province, and<br />

our conversations were deep and meaningful in those expansive landscapes. After<br />

a long day of canoeing, we would dip our standard-issue hard hats into the lake and<br />

enjoy a refreshing drink.<br />

Today, I’m rarely found without my stainless-steel water bottle in my backpack.<br />

Whether in nature or travelling through an airport, it’s an essential. I find sentimental<br />

value in my trusted companion of years, and each time I use it I know it’s one less<br />

plastic water bottle.<br />

To me, summers in Canada are about hearing crickets and loon calls on the water<br />

under the stars. In winter, there’s nothing like being carried by the wind while skating<br />

on a frozen lake. I always appreciate a short walk or a long trip, to connect more<br />

closely with others, and myself, in the outdoors. The magic of nature is that it can be<br />

felt by all.1<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2023</strong> 7

A<br />

gift<br />

for the<br />

grasslands<br />

The Weston Family Prairie<br />

Grasslands Initiative is<br />

empowering ranchers to play<br />

a critical role in conserving<br />

the few native prairie grasslands<br />

we have left<br />

BY Julie Barnes, freelance writer and editor<br />

Tamara Carter takes<br />

stock of the cattle<br />

on her family ranch.<br />

RACHELLE HODGINS.<br />

8 SPRING <strong>2023</strong> natureconservancy.ca

It’s a crisp, early December<br />

afternoon when I approach the<br />

Carter family ranch in southwest<br />

Saskatchewan. At first glance, it’s<br />

a stark winter landscape, capped<br />

in a blanket of fresh snow, disturbed only<br />

by the tracks of a Nuttall’s cottontail rabbit.<br />

But spend a little time here, and it becomes<br />

clear that these lands are brimming<br />

with biodiversity, both above and below the<br />

mineral-rich soil. And the Carters are intent<br />

on keeping it that way.<br />

Three kilometres down the driveway,<br />

some of the Carters’ 250 black Angus cattle<br />

come into view; a dramatic contrast against<br />

the white backdrop. Just up ahead is the<br />

family homestead, perched on the crest of a<br />

hill, shrouded in majestic stands of towering<br />

conifers, green ash and box elder.<br />

Tamara and Russ Carter are the stewards<br />

of these 2,800 hectares of native prairie grasslands.<br />

They purchased the land in 1996 and<br />

raised their children here, but the Carters’<br />

roots run even deeper. Russ’ family has farmed<br />

and ranched on these lands for over 100 years.<br />

Here, an interconnected web of soil microbiota,<br />

insects, plants, wildlife, cattle and humans<br />

work in harmony to maintain healthy<br />

and resilient grassland ecosystems. “It’s a gift,<br />

and it is a privilege,” says Tamara. “There’s<br />

a tremendous responsibility to care for the<br />

land. I don’t take it lightly.”<br />

Grasslands are among the world’s most<br />

endangered — and least protected — ecosystems.<br />

By some estimations, more than<br />

75 per cent of Canada’s prairie grasslands<br />

have been eradicated. Cropland conversion,<br />

urban sprawl and infrastructure, like highways,<br />

all play a role in their decline. Temperate grasslands<br />

are like giant lungs,” Tamara says. “They<br />

clean the air. They filter water.” She adds that<br />

the roots of the native grasses can reach down<br />

many metres, aiding in carbon sequestration.<br />

“People across Canada benefit from the positive<br />

impact of healthy and intact grasslands.”<br />

It’s Tamara’s “boots-on-the-ground” experience<br />

as a rancher that made her ideally<br />

suited to take on the role of director of prairie<br />

grasslands conservation for the Nature<br />

Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) for the last<br />

two years to develop and lead the Weston<br />

Family Prairie Grasslands Initiative (WFPGI),<br />

the largest ever prairie investment in stewardship<br />

on Canada’s grasslands. Although<br />

Tamara will be handing off the project, she<br />

has set it up well for success.<br />

Launched in 2021, the Stewardship Investment<br />

Program (SIP) is a four-year collaboration<br />

funded through the WFPGI. The SIP is<br />

designed to protect and conserve native prairie<br />

grasslands in Alberta, Saskatchewan and<br />

Manitoba. <strong>NCC</strong> has partnered with four land<br />

trusts to expand the program’s reach and<br />

amplify the impact: Ducks Unlimited Canada,<br />

Manitoba Habitat Heritage Corporation,<br />

Southern Alberta Land Trust Society<br />

(SALTS) and Western Sky Land Trust.<br />

Together with these land trusts, <strong>NCC</strong> is<br />

providing up to 830 grants. The funding aims<br />

to support work to maintain and enhance biodiversity<br />

outcomes on as much as 1.4 million<br />

hectares of grasslands in the Prairie provinces.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2023</strong> 9

All this is thanks to the generosity of the Weston<br />

Family Foundation’s healthy landscapes<br />

portfolio, which aims to restore and protect<br />

biodiversity on Canada’s wild, agricultural and<br />

urban landscapes. Landowners who meet the<br />

eligibility requirements can apply for an <strong>NCC</strong><br />

grant of up to $10,000 to fund projects that<br />

protect their grasslands and the species that<br />

depend on them.<br />

The funding comes at an opportune time,<br />

as ranchers are under increased financial<br />

pressure due to rapidly rising costs of fertilizer,<br />

fuel, feed and machinery. “Everything<br />

is going up, except what we’re getting paid<br />

for our cattle. Retail prices are not at all representative<br />

of what the rancher gets paid.”<br />

Landowners can make more money converting<br />

their grasslands into cropland for<br />

growing high-value crops like canola, wheat<br />

or lentils. “It’s really tempting if you’re not<br />

making money with cattle,” explains Tamara.<br />

Much of the country’s remaining grasslands<br />

are managed or owned by cattle producers,<br />

so ranchers like Tamara play a critical role in<br />

their stewardship. As the administrator of<br />

the SIP, she acted as a conduit between the<br />

conservation and ranching communities.<br />

“I learned about conservation myself from<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>, and now I’m taking some of that learning<br />

back into the ranching communities<br />

and saying, ‘Hey — this is what you can do<br />

with a partnership with <strong>NCC</strong>.’”<br />

As of year two, the program has funded<br />

close to 330 projects. The development of<br />

water systems and wildlife-friendly fencing<br />

have been among the most popular projects<br />

initiated by grant recipients, says Tamara.<br />

Ranchers and their herds play a critical role in the stewardship of Canada’s remaining grasslands.<br />

Wells of conservation<br />

The Prairies have experienced five years of<br />

significant drought, and Tamara has met with<br />

ranchers who were considering downsizing<br />

their herd and have even exited the industry<br />

due to lack of water access. The program has<br />

helped grant recipients finance the installation<br />

of new wells and troughs, allowing ranchers to<br />

keep their herd intact. “Those projects have<br />

instant, measurable results,” Tamara says.<br />

Cecily and Brian Knodel have witnessed<br />

the immediate impact a new water source can<br />

provide. Their family has been ranching on<br />

the northern slopes of Cypress Hills, Alberta,<br />

for over 120 years. During their lifetime, the<br />

couple has seen much of the grassland surrounding<br />

their property converted to cropland.<br />

“We are trying very hard to rotationally<br />

graze,” says Cecily. This involves moving cattle<br />

through the pasture to improve soil, rejuvenating<br />

the grass and giving the land time<br />

to recover. Getting the balance right spurs<br />

the plants to send out more roots, with<br />

deeper root systems.<br />

The Knodels already had a conservation<br />

agreement with the SALTS, a rancher-based<br />

land trust with over 16,000 hectares conserved<br />

in Alberta’s foothills and grasslands.<br />

“We talked to SALTS about bringing<br />

water further south to an area of the property<br />

in the north where we had cattle, but<br />

the animals tended to want to stay on the<br />

native grass as opposed to grazing on the<br />

tame grass,” says Cecily. “We thought if<br />

we could get a new water source on the<br />

tame grass and then fence it off, we could<br />

better utilize that quarter and protect<br />

the native grass.”<br />

Their contact at SALTS introduced them<br />

to the SIP program. The funding allowed<br />

them to create a new water source (a spring<br />

and water trough) and install a fence to facilitate<br />

improved rotational grazing.<br />

“Once the fence was put up, the cattle<br />

were allowed to stay on the tame grass for the<br />

spring and early summer,” says Brian. “That<br />

gave the birds time to nest without further<br />

disturbance from the cattle.” Grassland<br />

bird populations have fallen by 57 per<br />

cent since 1970, and it’s not just birds;<br />

more than 60 species at risk depend upon<br />

grasslands. These species at risk have<br />

fallen by almost 90 per cent in the same<br />

time frame.<br />

“When you’re in the cattle business,<br />

there’s not a lot of extra money around,”<br />

adds Brian. “It would have been extremely<br />

expensive for us to do this by ourselves. This<br />

grant from the Weston Family Foundation<br />

helped us enormously.” Once these projects<br />

are implemented, “you’ve created a better<br />

environment for wildlife, you’ve created<br />

a better environment for the cattle — it’s<br />

huge,” says Brian.<br />

Cecily echoes a sentiment Tamara has previously<br />

shared during our walk at the Carter<br />

ranch: “I don’t think people really appreciate<br />

that, as well as operating a business, we have<br />

to be good stewards of the land. If we wreck<br />

the land, we’ve wrecked our business.”<br />

Brian chimes in to add, “The land looks<br />

after us, so we have to look after it.”<br />

RACHELLE HODGINS.<br />

10 SPRING <strong>2023</strong><br />

natureconservancy.ca

ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; JASON BANTLE.<br />

Good stewardship is<br />

good for business<br />

As executive director of SALTS, Justin<br />

Thompson says one of the misconceptions he<br />

sees in grassland stewardship is that those<br />

who aren’t involved in ranching don’t recognize<br />

the positive role cattle can play.<br />

“Cattle are a tool in managing healthy<br />

grasslands. Grazing is the most compatible<br />

land use if your goal is to retain habitat<br />

for species at risk, watershed values and<br />

carbon,” he adds.<br />

Thompson says that funding from the<br />

Weston Family Foundation is having a multiplier<br />

effect, thanks to the strong partnerships<br />

fostered among environmental NGOs.<br />

“In recent years, land conservation has become<br />

a lot more collaborative,” he says. “The<br />

grants have allowed us to partner and collaborate<br />

with other NGOs that are not part of<br />

the program to leverage other funding…It<br />

means we are not just doing one project with<br />

these properties; we are doing one project<br />

and we’re bringing in another partner to do<br />

another project.”<br />

The program is having a similarly successful<br />

snowball effect in southwest Saskatchewan.<br />

Clint Christianson is the Chair of Val<br />

Marie Community Pasture (40,400 hectares),<br />

the manager of the adjacent Beaver Valley<br />

Community Pasture (24,300 hectares) and<br />

a board member with Lone Tree Community<br />

Pasture (13,300 hectares).<br />

With funding from the program, he’s<br />

worked with <strong>NCC</strong> to kick-start four conservation<br />

projects on the three pastures. The projects<br />

have provided water development and<br />

a wildlife-friendly electric fence to manage<br />

grazing rotations, like the Knodels have done.<br />

The impact is enormous. “We have a special<br />

thing here,” says Christianson. He notes that<br />

the funds help producers bear the costs of implementing<br />

actions that benefit everyone. “[The<br />

impact is] spread between 100 producers and<br />

benefits almost 81,000 hectares.”<br />

Christianson works closely with <strong>NCC</strong> and<br />

the ministries of Agriculture and Environment.<br />

When they gather on the community<br />

pastures, they all look at the landscape<br />

through a different lens.<br />

“I see something different as a rancher and<br />

producer than what they see, but now we can<br />

all get on the same page,” says Christianson.<br />

“Deep down, we all want the same thing: for<br />

this land to be the same a hundred years from<br />

now as it is today.”<br />

As the chair of the Weston Family Foundation’s<br />

conservation committee, and a<br />

rancher herself, Eliza Mitchell says the goal<br />

of the WFPGI is to support conservation<br />

agreements on approximately 1.6 million<br />

hectares of private grasslands to improve<br />

habitat for species at risk, improve wildlife<br />

movement, manage invasive species and<br />

restore native prairie grasslands. Ultimately,<br />

the goal is to ensure that the health of the<br />

grasslands is not only restored, but even improved<br />

to the way it was 100 years ago.<br />

With only an estimated 20 to 25 per cent<br />

of Canada’s grasslands remaining, “it’s imperative<br />

that we value and protect what is<br />

left,” Mitchell says. She explains that grasslands<br />

have the power to resist climate change<br />

through carbon sequestration: “These landscapes<br />

store billions of tonnes of carbon in<br />

their root system and soil, making up some of<br />

the highest carbon stocks in the world.”<br />

These landscapes evolved with the bison,<br />

says Mitchell. It’s an ecosystem “that needs<br />

a similar disturbance, like cows, to maintain<br />

its ecological integrity. It’s grazing, but it’s<br />

also hoof action. Those all have an effect on<br />

the grassland species. Without proper and<br />

targeted stewardship to mimic those disturbances,<br />

grasslands would quickly lose<br />

their unique and valuable biodiversity.”<br />

Back at the Carter family’s ranch, Tamara<br />

vividly renders a snapshot of the past.<br />

Standing out on the prairie, “I get goosebumps,”<br />

she says. “If you had been here 200<br />

to 500 years ago, you would have seen massive,<br />

black herds of bison, moving across the<br />

grasslands and grazing. If you close your eyes,<br />

you can almost feel it — the thundering of<br />

their hooves, like you were there in spirit.”<br />

She adds, “For thousands of years, this land<br />

has supported bison, deer, moose and pronghorn<br />

and our ancestors. Today, cattle graze<br />

here too. These few remaining grasslands<br />

have never been ploughed, cultivated or developed.<br />

When I’m out here with my cows,<br />

it’s like being tethered to all things that are<br />

still good, still natural. How many other<br />

places on the planet can you stand in and<br />

say, ‘This is still natural’?”1<br />

Bison.<br />

Ferruginous hawk.<br />

THE DECLINE OF<br />

GRASSLAND BIRDS<br />

Birds are some of the best indicators<br />

of the health of our planet and<br />

are beneficial for our mental health<br />

and communities.<br />

But birds that depend on grasslands,<br />

such as ferruginous hawk and<br />

chestnut-collared longspur, are at<br />

great risk of disappearing. Forever.<br />

Nearly 60 per cent of Canada’s<br />

grassland birds have disappeared<br />

since 1970 — that’s 300 million birds!<br />

The reasons for this rapid decline<br />

include crop agriculture, pesticide<br />

use and erosion, and severe drought<br />

and flooding due to climate change.<br />

But all is not lost.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> is working to protect grassland<br />

habitat. <strong>NCC</strong> is also helping determine<br />

the health of local bird populations<br />

at its Big Valley property in<br />

Saskatchewan by contributing to<br />

the Monitoring Avian Productivity<br />

and Survivorship (MAPS) program.<br />

The MAPS program monitors bird<br />

demographics and contributes to<br />

bird conservation across North<br />

America. A standardized system of<br />

fine mesh nets is used to capture<br />

birds during the summer nesting<br />

season. MAPS operators band the<br />

birds, collecting data on their age,<br />

sex, body condition and reproductive<br />

status. The captured birds are<br />

given a lightweight, uniquely<br />

numbered aluminum leg band and<br />

released unharmed. Since MAPS is<br />

a continent-wide program, data<br />

collected at Big Valley will also<br />

contribute to the conservation of<br />

birds across North America.<br />

SUPPORT CANADA’S GRASSLANDS<br />

natureconservancy.ca/grasslands<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2023</strong> 11

SPECIES<br />

PROFILE<br />

Blanding’s turtle<br />

Keep your eyes open for this “smiling” turtle and its bright yellow stripe<br />

ROBERT MCCAW.<br />

12 SPRING <strong>2023</strong><br />

natureconservancy.ca

APPEARANCE<br />

Blanding’s turtles are easily<br />

identified by their bright yellow chin and<br />

throat. And thanks to their curved mouth,<br />

these turtles appear to be always smiling.<br />

The species’ large domed, brown- to black-coloured<br />

upper shells (carapaces) can measure up<br />

to 28 centimetres long. They often have tan or<br />

yellow markings, but these may be faded or<br />

absent in some turtles. Their lower shell<br />

(plastron) is yellow with large dark<br />

blotches on the outside.<br />

RANGE<br />

There is a separate<br />

population of Blanding’s<br />

turtles in Nova Scotia, but<br />

most of the species’ Canadian<br />

range is in southern<br />

Ontario and western<br />

Quebec.<br />

ROBERT MCCAW.<br />

HABITAT<br />

Their preferred habitat is<br />

restricted to wetlands, beaver ponds,<br />

and lakes with shallow water and mucky<br />

bottoms. They spend the winter buried<br />

under the mucky bottoms in a hibernation-like<br />

state called brumation and enjoy<br />

basking in the sun in the spring. Blanding’s<br />

turtles travel several kilometres<br />

between their summer and<br />

winter habitats.<br />

THREATS<br />

The Great Lakes/St. Lawrence<br />

and Nova Scotia populations of<br />

Blanding’s turtles are both assessed by<br />

the Committee on the Status on Endangered<br />

Wildlife in Canada as endangered.<br />

Threats to this species include wetland<br />

habitat loss, motor vehicle collisions<br />

and illegal collection for the pet<br />

trade. Raccoons and foxes<br />

are nest predators.<br />

HELP OUT<br />

Help protect habitat for<br />

species at risk at<br />

natureconservancy.ca/<br />

donate.<br />

What <strong>NCC</strong> is<br />

doing to protect<br />

habitat for<br />

this species<br />

In Quebec, <strong>NCC</strong> has conservation<br />

projects where Blanding’s<br />

turtles occur in the Outaouais<br />

region, specifically in the<br />

Pontiac, Bristol, Clarendon and<br />

Sheenboro municipalities.<br />

Beaver ponds account for<br />

approximately 90 per cent of<br />

the species’ habitat. In building<br />

their dams, beavers create<br />

bodies of water where there<br />

used to be only streams,<br />

creating an ideal environment<br />

for Blanding’s turtles. By settling<br />

on top of the beaver lodge,<br />

these turtles can even sunbathe,<br />

which is necessary for<br />

their survival. To avoid dismantling<br />

beaver dams that can<br />

cause flooding, <strong>NCC</strong> is involved<br />

in installing sustainable and<br />

practical solutions, such as<br />

a pipe system that naturally<br />

regulates river levels without<br />

destroying these habitats.1<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2023</strong> 13

FORCE FOR<br />

NATURE<br />

Telling it<br />

like it is<br />

Aerin Jacob on big thinking and genuine communication in conservation<br />

ALBERT LAW.<br />

14 SPRING <strong>2023</strong><br />

natureconservancy.ca

Growing up, Aerin Jacob spent part of<br />

her summers at a family camp, north of<br />

Ontario’s Lake Superior. Her family would<br />

catch an overnight train from Toronto and sleepily<br />

meet her grandparents beside the railroad tracks<br />

after the long trip.<br />

ALBERT LAW.<br />

Jacob vividly remembers the call of the loon and the crunch of leaves<br />

under her feet, as she walked through the forest that surrounded<br />

the small lake.<br />

Her family lived in different parts of Canada and internationally,<br />

and she enjoyed lots of time spent in nature and exploring new<br />

places. “A common theme was our responsibility to other creatures,”<br />

says Jacob. “And trying to leave things better than you found them.”<br />

Jacob joined the Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) in September<br />

2022 as its director of conservation science and research, after<br />

six years with the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative. She<br />

has a deep well of experience to draw from, including designing and<br />

leading research across Canada and internationally, and authoring<br />

more than 50 scientific papers, technical reports and book chapters.<br />

Jacob is an adjunct professor, has served on panels and committees,<br />

and has received fellowships and awards for her conservation work.<br />

Jacob is a leader in encouraging conservation rooted in science,<br />

conducts research and supports projects with more than 150 research<br />

partners across Canada. She oversees <strong>NCC</strong>’s Weston Family Conservation<br />

Science Fellowship Program for masters’ and PhD students<br />

who conduct research about <strong>NCC</strong>-identified priorities, such as species<br />

at risk, ecological connectivity and invasive species.<br />

We need to be careful to be doing the right<br />

things in the right places and measuring<br />

our successes or failures over time to<br />

ensure we’re always striving to be better.<br />

“The fellowship program is really fun and meaningful,” says Jacob.<br />

“There’s so much energy about working with young people who have<br />

new ideas and are the next generation of conservation leaders.”<br />

Together, the priorities identified by <strong>NCC</strong> help to ensure the quality<br />

of conservation work, not just the quantity. “We need to be careful<br />

to be doing the right things in the right places and measuring our<br />

successes or failures over time,” she adds. “To ensure we’re always<br />

striving to be better.”<br />

The big picture is a theme throughout her work. She stresses the<br />

importance of looking at multiple threats to nature, with individual<br />

and cumulative impacts, and how different solutions can work together.<br />

“It’s about working on the biggest threats and courageous solutions so<br />

that we’re not just tinkering around the edges,” says Jacob.<br />

Communicating scientific knowledge is an important piece of the<br />

puzzle for her. She wasn’t always a comfortable public speaker, but<br />

has embraced it as an important way to mobilize scientific knowledge<br />

and conservation action more widely and effectively. Throughout the<br />

2022 UN Biodiversity Conference (COP15) in Montreal, she was busy<br />

with media interviews and public speaking. As a conference attendee,<br />

she says she felt inspired. “It was important<br />

to see Canada walking the talk about ambitious<br />

conservation and Reconciliation, which<br />

includes more funding and actively supporting<br />

Indigenous-led work.”<br />

Jacob believes there is an increased<br />

emphasis on the importance of Indigenous<br />

Knowledge in conservation. “It’s a significant,<br />

much-needed, shift,” she says. “Science and<br />

Indigenous Knowledge are both valid types<br />

of evidence, and we need to learn from both.<br />

Humility is important for scientists in this regard.<br />

It’s about being open to expertise from<br />

people who were trained in different ways.”<br />

Growing up, Jacob imagined her future<br />

self in different roles, including as a veterinarian<br />

or journalist. She sees a theme of service<br />

to community and environment in her<br />

aspirations. She also admits, with a laugh,<br />

that she was a nerdy kid.<br />

“My younger self would probably be<br />

really happy to know that you can make<br />

a career out of loving animals, the outdoors<br />

and always wanting to learn more,” she<br />

says. “Don’t hide that enthusiasm; use your<br />

voice to help others”1<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2023</strong> 15

PROJECT<br />

UPDATES<br />

1<br />

Expanding protection on The Rock<br />

ST. MARY'S BAY, NEWFOUNDLAND<br />

2<br />

THANK YOU!<br />

Your support has made these<br />

projects possible. Learn more at<br />

natureconservancy.ca/where-we-work.<br />

4<br />

3<br />

1<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) has an opportunity<br />

to more than double the size of its Salmonier Nature Reserve<br />

(177 hectares), located an hour’s drive south of St. John’s.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> is narrowing in on protecting an additional 230 hectares of<br />

forested land along the Salmonier Arm and is seeking the public’s<br />

support in closing the financial gap.<br />

The expansion area, located on the southeastern side of St. Mary’s<br />

Bay, is near the mouth of the Salmonier River and Avalon Wilderness<br />

Reserve, habitat that supports iconic woodland caribou. The reserve’s<br />

undulating, rugged landscape features a healthy forest comprised<br />

of balsam fir, black spruce and the eastern-most population of yellow<br />

birch in North America. A variety of wildlife, such as peregrine falcon,<br />

short-eared owl and red fox, and species at risk, like red crossbill<br />

and olive-sided flycatcher, thrive here.<br />

Learn how you can contribute and help make this opportunity a reality at<br />

natureconservancy.ca/salmonier.<br />

LEFT TO RIGHT: PHOTO COURTESY GAIL PENNINGTON; MIKE DEMBECK; MIKE DEMBECK.<br />

A lasting<br />

legacy<br />

“Ursula Linderkamp, my late<br />

stepmom, left a generous gift to<br />

the Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

(<strong>NCC</strong>) in her Will. I was not at all surprised<br />

because her whole life had been one of loving<br />

the great outdoors in its purest form.<br />

Caribou.<br />

“Ursula moved to Sudbury, Ontario, from Germany<br />

in 1957 and soon found her happy place on the<br />

shores of Wanapitei Lake. A fierce, independent<br />

woman, she built one of the first homes on the<br />

lake and loved the peace and calm that it brought<br />

to her. After meeting and marrying my father,<br />

Kenneth Pennington, in the 1980s, she enjoyed<br />

many years with him. No matter where they lived,<br />

they always stayed connected to the outdoors.<br />

Ursula loved to take cold swims in the Lake of Bays<br />

in Muskoka, and when they moved to Kitchener,<br />

they fell in love with the Grand River Trails and<br />

took their dogs out for daily excursions.<br />

“Nature was a large part of their life story.<br />

“Both Ursula and my late dad had a great appreciation<br />

for the continued preservation of the incredible<br />

landscapes of Canada. They knew that leaving<br />

a gift to <strong>NCC</strong> would be something they could<br />

do to help protect the lands and waters that they<br />

loved dearly. Their legacy will support conservation<br />

well into the future, for generations to come.<br />

It leaves me quite humbled and very proud.”<br />

~ Gail Pennington<br />

16 WINTER <strong>2023</strong> natureconservancy.ca

2<br />

A legacy for future generations<br />

TALL GRASS PRAIRIE, MANITOBA<br />

Manitoba’s tall grass prairie region is home to a community that is<br />

working in partnership to ensure the area’s unique nature is here for<br />

future generations to enjoy. The tall grass prairie is one of the rarest<br />

ecosystems in North America. The region is home to 28 species at<br />

risk, including western prairie white-fringed orchid, which is found<br />

nowhere else in Canada, and Poweshiek skipperling, a butterfly<br />

with a global population of fewer than 1,000.<br />

The Shared Legacy Partnership is a cooperative working group led<br />

by the Rural Municipality of Stuartburn and <strong>NCC</strong>, along with partners<br />

Sunrise Corner Economic Development and the Province of Manitoba.<br />

The primary focus of the partnership is to alleviate threats for species<br />

at risk, through advancing understanding of the wonder of the area,<br />

its relationship with agriculture, and the natural heritage that benefits<br />

all residents. It also aims to build meaningful relationships through<br />

the pillars of nature, culture and economy.<br />

Western prairie<br />

white-fringed orchid.<br />

To learn more, visit sharedlegacymb.ca. The partnership gratefully<br />

acknowledges the support of Environment and Climate Change’s Community<br />

Nominated Priority Places program.<br />

3<br />

Conservation, education and science<br />

KENAUK, QUEBEC<br />

Wood duck.<br />

ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; MARK TOMALTY; MIKE FORD; HELEN JONES.<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada and the Kenauk Institute (KI)<br />

are partnering in a unique campaign to ensure that Kenauk, located<br />

between Montreal and Gatineau, is not only protected for the long<br />

term but that this 25,000-hectare gem is also dedicated to the natural<br />

sciences and educating future generations.<br />

To make this happen, <strong>NCC</strong> and KI are creating a permanent<br />

open-air laboratory devoted to studying the impacts of climate<br />

change on Kenauk. By partnering with universities and public<br />

stakeholders, this expansive laboratory will provide opportunities<br />

for research within a temperate forest.<br />

Kenauk’s old-growth forests, lakes and wetlands house exceptional<br />

biodiversity, including rare and at-risk species, such as black maple<br />

and eastern wood-pewee.<br />

4<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>’s former president named<br />

a Member of the Order of Canada<br />

CANADA<br />

We are pleased to share that John Lounds has been named a Member<br />

of the Order of Canada.The announcement was recently made by<br />

Governor General Mary Simon, recognizing 99 Canadians from a range<br />

of backgrounds for their contributions to the country.<br />

As <strong>NCC</strong>’s previous president and CEO, Lounds led the organization<br />

through an incredible journey of growth and success. During his<br />

24 years of stewardship, he made it his personal and professional mission<br />

to protect Canada’s natural legacy for future generations. Both<br />

within <strong>NCC</strong> and beyond, he has encouraged continuous learning, big<br />

ideas and boundary-breaking approaches to Canada’s biggest conservation<br />

challenges.<br />

Congratulations to John and the other distinguished Canadians<br />

who received one of our country’s highest honours.1<br />

Researchers at Kenauk.<br />

John Lounds.<br />

Partner Spotlight<br />

Since 2020, Northern Keep<br />

Vodka has been supporting the<br />

Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

(<strong>NCC</strong>) in accelerating conservation<br />

and protecting natural<br />

habitats from coast to coast to<br />

coast. Northern Keep Vodka<br />

partners with <strong>NCC</strong> in support of<br />

its Land Preservation Campaign.<br />

Every bottle of Northern Keep<br />

sold during the campaign helps<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> protect .5 square metres<br />

of ecologically significant<br />

land and supports Northern<br />

Keep’s mission to Grow for<br />

Good, protecting the water,<br />

fields and forests that are<br />

integral to their product.<br />

Our partnership with Northern<br />

Keep provides us with the<br />

resources we need to help<br />

protect Canada’s biodiversity,<br />

now and into the future.<br />

natureconservancy.ca

CLOSE<br />

ENCOUNTERS<br />

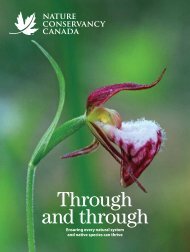

A dance to remember<br />

By Brian Keating, naturalist<br />

The sharp-tailed grouse dance at The Yarrow, in<br />

southern Alberta, is one of many spellbinding<br />

natural displays observable at this special place.<br />

I have explored The Yarrow through and through —<br />

its many wetlands, rolling grasslands and beautiful forests,<br />

all teeming with life and beauty. That’s why I jumped at<br />

the invitation from the Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

to help raise awareness about the effort to conserve this<br />

place in perpetuity.<br />

Simply put, there are not many places like it.<br />

One of my most memorable experiences at The Yarrow<br />

came when I visited it in late April 2022 to view the mesmerizing<br />

spectacle of sharp-tailed grouse performing their<br />

annual courtship display, known as lekking.<br />

Each year, groups of sharp-tailed grouse congregate<br />

in the same location, known as a lek. The males perform<br />

an intricate courtship display while the females keenly<br />

watch on. It’s a Darwinian spectacle that determines<br />

which male gets to mate with several females, and which<br />

must simply wait until next year.<br />

When we arrived [at the lek], there were still several<br />

grouse on the site, so we ate dinner in our camper, parked<br />

some distance away, and waited for them to depart.<br />

At 8:15 p.m., just before sunset, they flew off for the<br />

night. In the pre-dawn the following day, when I awoke<br />

shortly after 5 a.m., I could hear the grouse calling. The<br />

calls got louder as dawn approached. I was feeling very<br />

excited. Soon, it was light enough to film, and the grouse<br />

did not disappoint. There were 15 displaying males in<br />

total, and at least two females that approached them to<br />

inspect their performances.<br />

When the first female appeared, the dance intensity<br />

increased significantly. The males’ neck sacks glowed<br />

purple, brilliant yellow eye combs were puffed up, and<br />

with wings held out to the side, their foot stomping<br />

was a blur.<br />

By 9 a.m., the last grouse flew off, and the show was<br />

over. It was an experience I will never forget, and one<br />

I am keen to share with anyone willing to listen — to just<br />

say how special The Yarrow truly is.<br />

Without pristine landscapes like The Yarrow, these<br />

miraculous birds would simply have no other place to go.<br />

Conserving this place is a no-brainer, and we will all be<br />

richer for it, in experience and in the beings we share<br />

this wondrous planet with. To learn more about how you<br />

can help The Yarrow, visit theyarrow.ca.1<br />

To read the<br />

full version of<br />

this story, visit<br />

natureconservancy.ca/<br />

memorabledance.<br />

CORY PROULX.<br />

18 SPRING <strong>2023</strong> natureconservancy.ca

LET YOUR<br />

PASSION<br />

DEFINE<br />

YOUR<br />

LEGACY<br />

Your passion for Canada’s natural spaces defines your life; now it can define<br />

your legacy. With a gift in your Will to the Nature Conservancy of Canada,<br />

no matter the size, you can help protect our most vulnerable habitats and the<br />

wildlife that live there. For today, for tomorrow and for generations to come.<br />

Order your Free Legacy Information Booklet today!<br />

Call Jackie at 1-877-231-3552 x2275 or visit DefineYourLegacy.ca

YOUR<br />

IMPACT<br />

Conservation<br />

through<br />

collaboration<br />

In late January, the Government of British<br />

Columbia announced the protection of<br />

75,000 hectares of Crown land and fresh<br />

water in the majestic Incomappleux<br />

Valley. The project is the result of meaningful<br />

collaboration between <strong>NCC</strong>,<br />

First Nations, the Government of BC,<br />

Interfor Corporation and funding<br />

partners, including charitable foundations<br />

and the Government of Canada. <strong>NCC</strong><br />

acted as an important project broker and<br />

funder for the project. Learn more at<br />

natureconservancy.ca/incomappleux.<br />

Small addition with huge benefit<br />

At 255 hectares, the latest addition to the Waterton Park Front in southwestern<br />

Alberta may seem like a relatively small area, but this important parcel of<br />

fescue grasslands, forests and wetland habitat builds on over 13,000 hectares<br />

of conservation lands surrounding Waterton Lakes National Park. This area serves<br />

as an important corridor for wildlife movement in this incredible landscape,<br />

connecting natural areas outside this park, known as the Waterton Park Front.<br />

Thank you for all you do for nature in Canada!<br />

AUGUST 3–7, <strong>2023</strong><br />

This upcoming August long<br />

weekend, grab your camera<br />

and spend some time outdoors<br />

observing nature around you.<br />

Each year, the Big Backyard<br />

BioBlitz unites thousands of<br />

people across Canada in a<br />

collective community effort to<br />

celebrate and document the<br />

diverse species across our beautiful<br />

country. Together, we’ll<br />

grow the inventory of species<br />

observations so that scientists<br />

and conservation planners can<br />

use the data for future protection<br />

and conservation.<br />

Check out what we accomplished<br />

in 2022, and sign up<br />

for notifications about the <strong>2023</strong><br />

event: backyardbioblitz.ca<br />

TOP TO BOTTOM: PAUL ZIZKA; BRENT CARVER.