You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

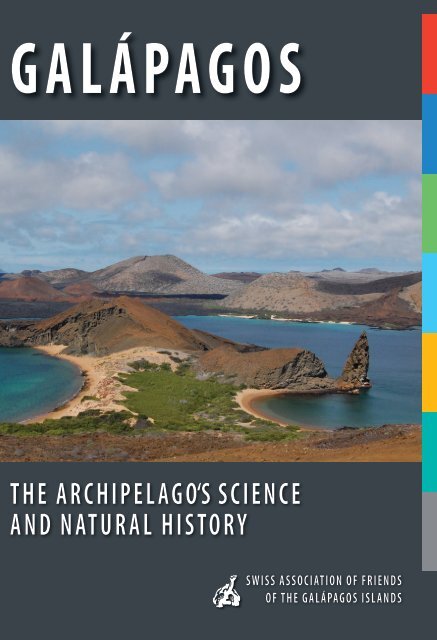

GALÁ PAGOS<br />

Islands of Fire<br />

THE ARCHIPELAGO‘S SCI<strong>EN</strong>CE<br />

AND NATURAL HISTORY<br />

SWISS ASSOCIATION OF FRI<strong>EN</strong>DS<br />

OF THE GALÁ PAGOS ISLANDS<br />

i

Islands of Fire<br />

SWISS ASSOCIATION<br />

OF FRI<strong>EN</strong>DS OF THE<br />

GALÁ PAGOS ISLANDS<br />

This travel guide was produced by<br />

the Swiss Association of Friends of<br />

the Galápagos Islands, a non-profit<br />

organization that supports projects<br />

for the preservation of Galápagos<br />

(www.galapagos-ch.org). The profits<br />

from sales of this book will help<br />

conservation and research projects<br />

throughout the Galápagos Islands.<br />

ii

Islands of Fire<br />

Islands of Fire<br />

BARR<strong>EN</strong> YET DIVERSE<br />

on Page 1<br />

Colonisation<br />

LUCK AND EXCEPTIONAL ABILITIES<br />

on Page 13<br />

Evolution<br />

A LITTLE WORLD WITHIN ITSELF<br />

on Page 35<br />

Fearless?<br />

TAME YET STRESSED<br />

on Page 57<br />

Test Tube Islands<br />

A SCI<strong>EN</strong>TIST‘S PARADISE<br />

on Page 71<br />

Conservation<br />

STUDY AND PROTECT<br />

on Page 95<br />

Species Guide<br />

ID<strong>EN</strong>TIFYING THE LOCALS<br />

on Page 113<br />

iii

Darwin<br />

Islands of Fire<br />

Wolf<br />

Pinta<br />

Marchena<br />

Ecuador Volcano<br />

Wolf Volcano<br />

Santiago<br />

Darwin Volcano<br />

Daphne Major<br />

Fernandina<br />

Alcedo Volcano<br />

Rábida<br />

Santa Cruz<br />

Baltra<br />

Isabela<br />

Cerro Azul Volcano<br />

Pinzón<br />

Sierra Negra Volcano<br />

Santo Tomás<br />

Puerto Villamil<br />

Bellavista<br />

Puerto Ayora<br />

Santa Fé<br />

N<br />

iv<br />

Human settlement<br />

100 km<br />

Puerto Velasco Ibarra<br />

Floreana<br />

Champion<br />

Gardner-por-<br />

Floreana

Panama<br />

Pacific Ocean<br />

Colombia<br />

Ecuador<br />

Peru<br />

Genovesa<br />

Seymour Norte<br />

San Cristóbal<br />

Puerto Baquerizo<br />

Moreno<br />

El Progreso<br />

Española<br />

Gardner-por-Española

GALÁPAGOS<br />

The Archipelago's Science<br />

and Natural History<br />

Swiss Association of<br />

Friends of the Galápagos Islands<br />

Lukas Keller, Ph.D.<br />

Marianne Haffner, Ph.D.<br />

Paquita Hoeck, Ph.D.<br />

Ursina Koller, M.Sc.<br />

Hendrik Hoeck, Ph.D.<br />

Zurich, Switzerland<br />

2018

SWISS ASSOCIATION OF<br />

FRI<strong>EN</strong>DS OF THE GALÁPAGOS ISLANDS<br />

Zurich<br />

Copyright 2018<br />

Lukas Keller, Marianne Haffner, Paquita Hoeck,<br />

Ursina Koller, Hendrik Hoeck<br />

English Translation: Lilian Dutoit, Anna-Sophie Wendel,<br />

Yves-Manuel Méan, Sabine Sonderegger, Aline Jenni,<br />

Anja Rosebrock, Mitchell Bornstein<br />

Layout and Design: Brian Maiorano<br />

ISBN 978-3-9525238-3-4<br />

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced<br />

or transmitted in any form without the prior written permission of<br />

the Swiss Association of Friends of the Galápagos Islands.<br />

Printed in Austria: DGS GmbH, A-1220 Vienna

Dedicated to those, past and present,<br />

who have helped conserve these islands<br />

for the generations to come.

Islands of Fire<br />

BARR<strong>EN</strong> YET DIVERSE<br />

on Page 1<br />

Colonisation<br />

LUCK AND EXCEPTIONAL<br />

ABILITIES<br />

on Page 13<br />

Evolution<br />

A LITTLE WORLD<br />

WITHIN ITSELF<br />

on Page 35<br />

Fearless?<br />

TAME YET STRESSED<br />

on Page 57

Test Tube Islands<br />

A SCI<strong>EN</strong>TIST‘S PARADISE<br />

on Page 71<br />

Conservation<br />

STUDY AND PROTECT<br />

on Page 95<br />

Species Guide<br />

ID<strong>EN</strong>TIFYING THE LOCALS<br />

on Page 113<br />

Appendix<br />

BIBLIOGRAPHY<br />

ILLUSTRATION CREDITS<br />

ACKNOWLEDGEM<strong>EN</strong>TS<br />

INDEX<br />

ABOUT THE AUTHORS<br />

on Page 142<br />

on Page 144<br />

on Page 146<br />

on Page 146<br />

on Page 153

xii

Preface<br />

The Galápagos Islands evoke fantasies of paradise and are a dream destination<br />

of many a traveller. The islands’ unique and bizarre creatures such<br />

as marine iguanas, flightless cormorants, giant tortoises, or finches with<br />

bills of all shapes and sizes have made the archipelago world-famous.<br />

Charles Darwin was fascinated with the forms of life he explored there<br />

during his visit in 1835. These observations would later contribute substantially<br />

to the development of his theory of evolution. To this day, these<br />

unique islands are considered a natural laboratory to study the processes<br />

of evolution and are a dream research site for most biologists.<br />

But the islands have witnessed many changes since Darwin’s visit.<br />

Whereas a few decades ago it was mainly naturalists who visited and very<br />

few people actually lived on the islands, tourism and the resident human<br />

population have grown exponentially since the 1990s. The native animals<br />

and plants have struggled with the negative effects of introduced species<br />

and other anthropogenic changes to the formerly isolated ecosystem.<br />

Thanks to elaborate conservation measures some of the negative effects<br />

have been mitigated, but many challenges remain if we are to preserve this<br />

fascinating ecosystem.<br />

While there is no such thing as a zero-impact trip to the Galápagos,<br />

every individual travelling there can contribute to the preservation of this<br />

fantastic site: follow the National Park guidelines, choose your form of<br />

travel wisely, inform yourself about the islands' uniqueness, and support<br />

conservation and education projects that benefit the islands. With joint<br />

efforts and a global recognition of the area's importance, the wonderful<br />

Galápagos creatures may be enjoyed by many future generations.<br />

About this book<br />

Written by scientists with long-standing professional and personal connections<br />

to Galápagos, this book provides a comprehensive overview of<br />

the natural history and ecology of the Galápagos Islands. We investigate<br />

the peculiar evolution that happened on these islands and how scientific<br />

activities shape our understanding of this place and also help us preserve<br />

it.<br />

Using examples of specific species, this book showcases key evolutionary<br />

processes and encourages the reader to think about ecological or behavioural<br />

contexts when observing animals or plants in Galápagos. The<br />

book uses abundant photographs and illustrations to give the reader a<br />

visual tour through the different topics. It also contains a wildlife guide<br />

showing some of the animal and plant species that the visitor is most likely<br />

to encounter.<br />

This book is a complement to the site-specific information that visitors<br />

on a guided tour will receive from their National Parks guide. It also<br />

makes for either a great pre-trip read, or an entire virtual tour for the<br />

armchair traveller.<br />

xiii

Islands of Fire<br />

xiv

Islands of Fire<br />

BARR<strong>EN</strong> YET DIVERSE<br />

Islands of Fire<br />

V<br />

olcanic eruptions created the Galápagos Islands, and these eruptions<br />

continue to shape the islands even today. Only a relatively <strong>short</strong> time<br />

ago, new habitats for plants and animals emerged—in complete isolation—in<br />

the middle of the ocean. The islands are located at the equator<br />

in the tropics, but the climate is subject to significant seasonal variations,<br />

because warm and cold ocean currents meet here and interact with each<br />

other. Above all, the region is extremely arid. That's why plants adapted to<br />

dry climates predominate. However, the higher an island, the greater the<br />

variety of plant communities.<br />

1

Islands of Fire<br />

Volcanic Islands<br />

The Galápagos Archipelago is completely isolated in the middle of the<br />

Pacific Ocean, about 960 km off the west coast of South America. It<br />

consists of 19 main islands (larger than 1 sq. km) and many smaller islands,<br />

as well as numerous islets and rocks. They are spread over more<br />

than 120,000 sq. km of ocean and consist of a total land surface of about<br />

8,000 sq. km.<br />

The Galápagos Islands are of volcanic origin. On Isabela and Fernandina,<br />

some volcanoes are still active. The westernmost island, Fernandina, is<br />

the centre of volcanic activity. Below it, a magma chamber of molten rock<br />

is located deep down in the earth’s interior. This hotspot is the origin of<br />

the Galápagos Islands.<br />

Young islands in motion<br />

The Galápagos Islands are located on the Nazca Plate, which moves towards<br />

South America at a rate of about 6 cm per year. While the islands<br />

move, the hotspot—the origin of the volcanic islands—stays in the same<br />

place.<br />

The islands are between 35,000 and 4 million years old. It is during this<br />

period that most evolution occurred and new species developed.<br />

There are also sunken islands up to 2,500 m below sea level that are<br />

probably about 5 to 14 million years old. There is evidence suggesting that<br />

some of today’s species have ancestors that go back more than 3 to 4 million<br />

years. Therefore, the most likely scenario is that evolution already<br />

occurred on these islands while they were still above sea level.<br />

Evolution of an Island Chain<br />

Nazca<br />

Plate<br />

Hot magma presses<br />

into the fissures<br />

of the Nazca<br />

Plate and creates<br />

chambers close to<br />

the surface.<br />

2<br />

The heat of the<br />

magma melts the<br />

earth’s surface<br />

crust, causing a<br />

volcanic eruption on<br />

the ocean floor.<br />

With every eruption, new layers of lava<br />

increase the size of the volcano until it breaks<br />

the ocean surface to form a new island.

Islands of Fire<br />

The crust and the upper part of the earth's mantle (lithosphere) consist of plates: seven<br />

major plates and many small ones, which are more or less mobile. The largest plates carry<br />

continents such as South America, Africa or Eurasia. Smaller plates can carry islands, such<br />

as the Galápagos Islands on the Nazca Plate.<br />

The temperatures below the plates are so high that they partially melt the rock. This<br />

subter ranean molten mass is called magma. As soon as it is expelled to the surface of the<br />

earth, it is called lava.<br />

Nazca<br />

Plate<br />

HS<br />

HS<br />

The Nazca Plate<br />

moves above the<br />

fixed hotspot<br />

(HS), the magma<br />

chamber.<br />

On its journey atop the<br />

Nazca Plate, the volcano<br />

gradually loses its connection<br />

to the magma<br />

chamber and becomes<br />

extinct.<br />

The magma chamber<br />

creates a new volcano.<br />

The old island is eroded<br />

mainly by wind and<br />

weather, causing it to<br />

decrease in size until<br />

it disappears from the<br />

ocean surface.<br />

3

Islands of Fire<br />

Ages of Islands and Years of Volcanic Eruptions<br />

Formed<br />

< 0.5 million<br />

years ago<br />

approx.<br />

1150<br />

2018<br />

2015<br />

1813<br />

1993<br />

1928<br />

1991<br />

Formed 1–2.5<br />

million years ago<br />

1906<br />

Santiago<br />

formed<br />

> 2.5 million<br />

years ago<br />

hotspot with magma chamber<br />

active volcano (last eruption)<br />

sunken islands<br />

movement of Nazca plate<br />

Isabela<br />

2018<br />

2008<br />

Santa<br />

Cruz<br />

San Cristóbal<br />

Floreana<br />

Española<br />

N<br />

The Nazca Plate moves southeast over the hotspot, the origin of the volcanic islands. The oldest<br />

islands with the lowest elevations can be found in the southeastern part of the archipelago,<br />

whereas the youngest islands with the largest volcanoes are located in the northwest. On the islands<br />

of Isabela and Fernandina, there are still some active volcanoes. The last volcanic eruptions<br />

took place in 2008 (Cerro Azul Volcano on Isabela), 2009 (on Fernandina), 2015 (Wolf Volcano on<br />

Isabela), and 2018 (Sierra Negra Volcano on Isabela and La Cumbre Volcano on Fernandina).<br />

4

Islands of Fire<br />

In 1968, the crater floor of La Cumbre Volcano on the island of Fernandina sank by 350 m. In<br />

1988, a lake started to form in the northern part of the crater. (dotted line: level of the crater floor<br />

before 1968)<br />

“... as far as the eye could reach we saw nothing but rough fields of lava, that seemed to<br />

have hardened while the force of the wind had been rippling its liquid surface [...] About<br />

half way down the steep south east side of the Island, a volcano burns day and night;<br />

and near the beach a crater was pouring forth streams of lava, which on reaching the sea<br />

caused it to bubble in an extraordinary manner.“ This is how Captain Lord George Anson<br />

Byron described a volcanic eruption in 1825 as he lay at anchor off Fernandina during his<br />

long journey to the Sandwich Islands (Hawaiian Islands).<br />

5

Islands of Fire<br />

Climate<br />

Atypical: tropical islands with a dry climate<br />

The dry climate on the Galápagos Islands is very atypical of the tropics.<br />

Equally atypical is the pronounced seasonability, with a warm season between<br />

January and May with frequent, heavy rains; and a very dry season<br />

between June and December with only little precipitation in the island<br />

lowlands. This anomaly can be explained by the ocean currents that meet<br />

and interact here in the Pacific Ocean. Two currents carry cold water: the<br />

Peru Current (Humboldt Current) from the Antarctic and the Equatorial<br />

Undercurrent (Cromwell Current) from the deep sea. Together they are<br />

responsible for the cool, dry season. The Panama Current brings warm<br />

tropical water from Central America and affects the warm season. The<br />

little precipitation that does occur during the dry season is a light drizzle<br />

called garúa, which often stops around noon.<br />

North Equatorial Countercurrent<br />

Panama<br />

Current<br />

Equatorial<br />

Undercurrent<br />

South Equatorial Current<br />

Ecuador<br />

Humboldt Current<br />

Peru Cu rent<br />

“El Niño”: both a blessing and a curse<br />

At irregular intervals about every 3 to 6 years, significant changes in ocean<br />

current conditions lead to a much warmer and rainier season called “El<br />

Niño”. The name is Spanish for the Infant Jesus, and is used because the<br />

phenomenon is strongest at Christmas time. El Niño is both a blessing and<br />

a curse: in the interior of the island, it leads to times of plenty, but it has<br />

severe consequences for the sea and the coastal areas. Sea birds suffer<br />

from lack of food (fish) and the high surf may flood their breeding sites as<br />

well as the nesting grounds of sea turtles and marine iguanas. In 1982 and<br />

1983, the water temperature became so warm that it caused the death of<br />

most of the green algae on which marine iguanas mainly feed. As a result,<br />

the populations of this species declined dramatically.<br />

There are also cold and dry seasons, which are called “La Niña”.<br />

6

Islands of Fire<br />

The difference between a wet (El Niño) and dry year on Daphne Major.<br />

Greater plant diversity on high islands<br />

Most of the islands are not high and have a very dry climate. Only plants<br />

that are highly adapted to drought can be found on such islands. However,<br />

on high islands, there are up to five different zones, each with unique<br />

plant communities that differ in the amount of water they need.<br />

In higher zones, more rain falls, supporting plants that need more<br />

moisture. The reason for the higher rainfall is that the air is cooler, causing<br />

the moisture in the clouds to condense and fall as rain. However, on<br />

very high islands another dry zone exists above the clouds.<br />

The various zones do not run parallel to each other around the islands<br />

and they are not the same in all areas. For example, the dry zones in<br />

7

About the Authors<br />

Lukas Keller is a professor in evolutionary<br />

biology and director of the Zoological Museum<br />

at the University of Zürich in Switzerland. He<br />

studied evolution and inbreeding in Darwin’s<br />

finches and mockingbirds for many years, during<br />

which he spent many months on remote<br />

islands in the Galápagos. In 2014 he became<br />

president of the Swiss Association of Friends of<br />

the Galápagos Islands (SAFGI)<br />

Appendix<br />

Marianne Haffner taught biology and performed<br />

research at the University of Zürich for<br />

many years before she became manager of the<br />

university’s Zoological Museum. In 2012 Marianne<br />

was heavily involved in the development<br />

of a Galápagos exhibit designed at the museum.<br />

Paquita Hoeck spent the first years of her<br />

life on the Galápagos when her father was director<br />

at the Charles Darwin Research Station.<br />

As a PhD student in biology, she returned to<br />

Galápagos to investigate the genetic composition<br />

of mockingbirds on different islands.<br />

Paquita runs the office of the SAFGI.<br />

Ursina Koller is a teacher and biologist by<br />

training, and works as head of education at the<br />

Zoological Museum of the University of Zürich.<br />

Her involvement in an exhibit about Galápagos<br />

and a trip to the islands aroused her passion for<br />

this unique place and resulted in her becoming<br />

a board member of the SAFGI.<br />

Hendrik Hoeck is a biologist and former director<br />

of the Charles Darwin Research Station<br />

on Santa Cruz Island. He is the founder of the<br />

SAFGI and has been involved in conservation<br />

efforts in Galápagos for over 30 years. As a tour<br />

guide, he led countless groups to the islands.<br />

153

Pinta (Abingdon)<br />

59 km 2 , origin of Lonesome<br />

George, no visitor site<br />

Isabela (Albermarle)<br />

ca. 4700 km 2 , six volcanoes, inhabited<br />

Mangroves, scalesia, candelabra cactus<br />

Cormorants, giant tortoises, land iguanas<br />

Santiago (James)<br />

577 km 2 , salt-lake crater<br />

Pahoehoe lava structures<br />

Mangroves, muyuyu, palo santo<br />

Fur seals, hawks, Sally Lightfoot crab<br />

Fernandina (Narborough)<br />

638 km 2 , youngest island, most active volcano<br />

Lava cactus, mangroves, saltbush<br />

Cormorants, penguins, marine iguanas<br />

N<br />

Human settlement<br />

Rábida (Jervis)<br />

5 km 2 red sand beach<br />

Palo santo, opuntia cactus, croton, black mangroves<br />

Sea lions, Darwin’s finches, flamingos, white-cheeked pintails<br />

Pinzón (Duncan)<br />

18 km 2 , no visitor site<br />

50 km

Appendix<br />

Marchena (Bindloe)<br />

130 km 2 , no visitor site<br />

Genovesa (Tower)<br />

14 km 2 , old shield volcano<br />

Palo santo, croton, muyuyu<br />

Swallow-tailed gulls, red-footed boobies, <strong>short</strong>-eared owl<br />

Bartolomé (Bartholomew)<br />

1.2 km 2 , dramatic volcanic formations, Pinnacle Rock<br />

Mangroves, grey matplant, lava cactus<br />

Penguins, reef sharks, rays<br />

Seymour Norte (North Seymour)<br />

1.9 km 2 , lava plateau<br />

Palo santo trees, parkinsonia, opuntia cactus, croton<br />

Boobies, frigate birds, land and marine iguanas<br />

Baltra (South Seymour)<br />

26 km 2 , airport<br />

Reintroduced land iguanas, Darwin’s finches<br />

Daphne Mayor (Daphne Major)<br />

0.3 km 2 , no visitor site<br />

Well-known for Darwin‘s finch studies<br />

Plaza Sur (-)<br />

0.13 km2, lava plateau<br />

Sesuvium, Galápagos carpetweed, opuntia cactus<br />

Land iguanas, red-billed tropicbirds, swallow-tailed gulls<br />

Santa Cruz (Indefatigable)<br />

986 km 2 , lava tunnels<br />

Mangroves, scalesia, opuntia cactus<br />

Giant tortoises, flycatchers, Darwin’s finches<br />

Floreana (Charles, Santa María)<br />

173 km 2 , first island colonized by humans,<br />

Post Office Bay<br />

Scalesia, palo santo, croton<br />

Marine iguanas, Darwin’s finches, flamingos<br />

Santa Fé (Barrington)<br />

24 km 2, Tree opuntia, palo santo, saltbush<br />

Land iguanas, sea lions, rice rats<br />

San Cristóbal (Chatham)<br />

557 km 2 , capital of Galápagos, inhabited<br />

Mangroves, candelabra cacti, muyuyo<br />

Giant tortoises, frigatebirds, sea lions<br />

Española (Hood)<br />

60 km 2 , old, flat island, blowhole<br />

Parkinsonia, mesquite, saltbush<br />

Sea lions, Galápagos albatross, boobies, mockingb<br />

155

Appendix<br />

SWISS ASSOCIATION<br />

OF FRI<strong>EN</strong>DS OF THE<br />

GALÁ PAGOS ISLANDS<br />

Support science and conservation<br />

in Galápagos.<br />

Become a member:<br />

www.galapagos-ch.org<br />

156

Appendix<br />

UNIQUE AND BIZARRE PARADISE<br />

The Galápagos Islands are a dream destination unlike any other<br />

spot on earth. This book showcases the evolution and peculiarities<br />

of this unique place, from the formation of the volcanic islands to its<br />

colonization by plants, animals, and—more recently—humans.<br />

Why are reptiles the largest animals on land and why are there so<br />

few mammals? Why are so many Galápagos species found nowhere<br />

else? And why don’t blue-footed boobies or land iguanas flee when we<br />

approach them? The book answers these and many more questions.<br />

Written by scientists who have lived and worked in the Galápagos,<br />

this book shows how the islands have shaped our understanding<br />

of evolution. With more than 330 full-color photographs and<br />

illustrations, the reader is taken on a visual tour while learning<br />

about the latest science and research activities that contribute to the<br />

conservation of the islands. Plus, an illustrated guide identifies more<br />

than 125 commonly seen species of animals and plants.<br />

157