Classic Mountain Scrambles by Andrew Dempster sampler

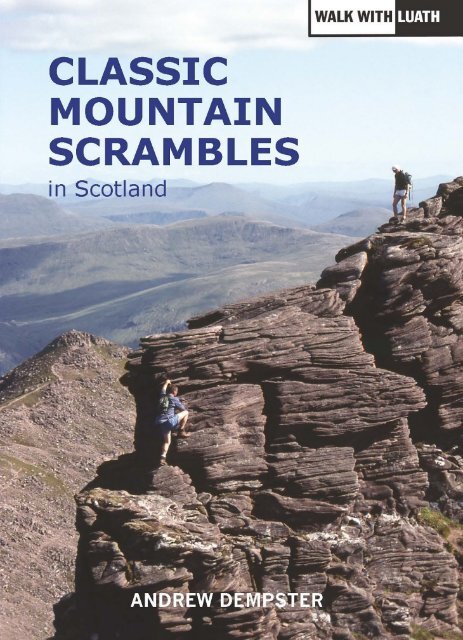

Scrambling is the highly popular pursuit which combines the freedom enjoyed by the hillwalker with the more immediate excitement of the rock climber. An essential guide to the best scrambling in Scotland, this book covers both the mainland and the inner hebrides, and is suitable for scramblers of all skill levels, from complete beginner to seasoned enthusiasts. This comprehensive guide contains: Maps and images for each scramble, as well as instructions for OS maps. An introduction to the art of scrambling, and to all equipment that may be necessary. Routes for all scrambles, and easy to follow grading and quality ratings, enabling the reader to pick a scramble for any ability level. Scrambles include mountain routes such as Aonach Eagach and the Cuillin Ridge, as well as the lesser known Northern Pinnacles of Liathach.

Scrambling is the highly popular pursuit which combines the freedom enjoyed by the hillwalker with the more immediate excitement of the rock climber. An essential guide to the best scrambling in Scotland, this book covers both the mainland and the inner hebrides, and is suitable for scramblers of all skill levels, from complete beginner to seasoned enthusiasts.

This comprehensive guide contains:

Maps and images for each scramble, as well as instructions for OS maps.

An introduction to the art of scrambling, and to all equipment that may be necessary.

Routes for all scrambles, and easy to follow grading and quality ratings, enabling the reader to pick a scramble for any ability level. Scrambles include mountain routes such as Aonach Eagach and the Cuillin Ridge, as well as the lesser known Northern Pinnacles of Liathach.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

andrew dempster has almost 40 years’ experience of scrambling, hillwalking<br />

and backpacking in the Scottish Highlands and Islands. He has climbed all the<br />

Munros twice, and all the Corbetts, and wrote the first guidebook to the Grahams<br />

(mountains between 2,000 and 2,500ft in height). He has also walked, trekked<br />

and climbed extensively in such varied locations as the Alps, the Pyrenees, the<br />

Himalayas, Africa, Iceland and Greenland. The Highlands of Scotland are his first<br />

love, however. He is a retired mathematics teacher, currently living in rural Perthshire<br />

with his wife, Heather, and son, Ruaraidh.<br />

1<br />

The author on Sgurr na Stri (Skye)

2<br />

By the same author:<br />

The Munro Phenomenon (Mainstream, 1995)<br />

The Grahams (Mainstream, 1997)<br />

Skye 360 (Luath, 2003)<br />

100 <strong>Classic</strong> Coastal Walks in Scotland (Mainstream, 2011)<br />

The Hughs: The Best Wee Hills in Scotland. Vol. 1: The Mainland (Luath, 2015)<br />

The Munros: A History. (Luath, 2021)

3<br />

<strong>Classic</strong> <strong>Mountain</strong> <strong>Scrambles</strong><br />

in Scotland<br />

ANDREW DEMPSTER

4<br />

First published <strong>by</strong> Mainstream Publishing in 1992<br />

New edition 2016<br />

Reprinted 2017, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022<br />

isbn: 978-1-910745-12-0<br />

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book<br />

under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.<br />

The paper used in this book is recyclable. It is made<br />

from low chlorine pulps produced in a low energy,<br />

low emissions manner from renewable forests.<br />

Printed and bound <strong>by</strong><br />

iPrint Global Ltd., Ely<br />

Typeset in 8.5 point Sabon <strong>by</strong><br />

Main Point Books<br />

© <strong>Andrew</strong> <strong>Dempster</strong> 2016

Contents<br />

5<br />

Preface to the new edition 9<br />

Introduction 11<br />

part i: skye and other islands 19<br />

Route<br />

Introduction to Skye 21<br />

1 The Traverse of Sgurr nan Gillean 27<br />

2 The Pinnacle Ridge of Sgurr nan Gillean 31<br />

3 The Spur of Sgurr an Fheadain 35<br />

4 The Round of Coire a’ Ghreadaidh 38<br />

5 The Round of Coire Lagan 42<br />

6 The Cioch (Collie’s Route) 48<br />

7 Amphitheatre Arête 52<br />

8 The West Buttress of Sgurr Sgumain 54<br />

9 The South Cuillin Ridge<br />

(Sgurr Dubh an Da Bheinn to Gars-bheinn) 56<br />

10 The Dubhs Ridge 59<br />

11 The North-east Ridge of Sgurr a’ Choire Bhig 64<br />

12 The Main Ridge Traverse 66<br />

13 The Traverse of Blaven and Clach Glas 73<br />

Other Routes on Skye 79<br />

Introduction to Rum 81<br />

14 The Rum Cuillin Traverse 83<br />

Introduction to Arran (and Mull) 89<br />

15 The Round of Glen Sannox 91<br />

16 The Round of Glen Rosa 95<br />

17 The A’ Chioch Ridge of Ben More (Mull) 97<br />

part ii: ben nevis and glencoe 99<br />

Introduction to Ben Nevis 101<br />

18 The Carn Mor Dearg Arête 103<br />

19 Ledge Route of Carn Dearg 106

6<br />

contents<br />

20 Castle Ridge 109<br />

21 Tower Ridge 111<br />

22 The North-east Ridge of Aonach Beag 115<br />

Other Routes in the Ben Nevis Area 118<br />

Introduction to Glencoe 119<br />

23 Curved Ridge and Crowberry Tower 121<br />

24 Lagangarbh Buttress 124<br />

25 North Buttress 126<br />

26 Sron na Creise 129<br />

27 Sron na Lairig and Beinn Fhada 131<br />

28 Barn Wall Route (of Aonach Dubh) 134<br />

29 Number 3 Buttress (of Stob Coire nam Beith) 136<br />

30 A’Chailleach 138<br />

31 Aonach Eagach 140<br />

Other Routes in the Glencoe Area 143<br />

part iii: north of the great glen 145<br />

Ardgour and Kintail<br />

32 The Pinnacle Ridge of Garbh Bheinn 147<br />

33 The North Ridge of Sgurr Ghiubhsachain 150<br />

34 The Forcan Ridge of the Saddle 152<br />

35 Sgurr a’ Choire Ghairbh Ridge of Beinn Fhada 154<br />

Wester Ross<br />

36 A’Chioch of Beinn Bhan 156<br />

37 Beinn Alligin 158<br />

38 Liathach via the South-east Ridge of Mullach an Rathain 162<br />

39 The Northern Pinnacles of Liathach 167<br />

40 The Black Carls of Beinn Eighe 169<br />

41 An Teallach 171<br />

The Far North<br />

42 Stac Pollaidh 176<br />

43 Lurgainn Edge of Cul Beag 179<br />

44 Suilven 181<br />

Other Routes North of the Great Glen 185

contents<br />

7<br />

part iv: south and east of the great glen 189<br />

45 The Fiacaill Ridge 191<br />

46 The North-east ridge of Angel’s Peak 194<br />

47 Lochnagar: Central Buttress 196<br />

48 Lochnagar: the Stuic 199<br />

49 The Cobbler 201<br />

50 The Lancet Edge of Sgor Iutharn 204<br />

Other Routes South of the Great Glen 206<br />

Appendix: Technical Skills and Ropework <strong>by</strong> Martin Moran 209<br />

Glossary of Gaelic Names 221<br />

Sgurr nan Gillean (Skye)

8<br />

Scrambling on Clach Glas (Skye)

Preface<br />

9<br />

this new edition of <strong>Classic</strong> <strong>Mountain</strong> <strong>Scrambles</strong> in Scotland contains over<br />

70 new photographs <strong>by</strong> the author. The intervening 24 years since its original<br />

publication <strong>by</strong> Mainstream in 1992 have seen a steady rise in the popularity of<br />

scrambling with several new scrambling guides appearing, such as Skye <strong>Scrambles</strong><br />

and Highland <strong>Scrambles</strong> North, both from the Scottish <strong>Mountain</strong>eering<br />

Club. However, <strong>Classic</strong> <strong>Mountain</strong> <strong>Scrambles</strong> is still the only guide to describe<br />

the best scrambles in Scotland.<br />

Some minor alterations and amendments have been made to the text and<br />

the maps have been redrawn to incorporate colour, as have the diagrammatic<br />

sketches. Martin Moran’s ‘Technical Skills and Ropework’ appears unchanged<br />

and thanks are again due to him for this excellent and valuable contribution.<br />

Liathach from Loch Clair

10<br />

The air was still and a hot sun beat upon the crags. We therefore<br />

went shirtless and enjoyed one of the most invigorating ridgewalks<br />

that have fallen to us in summer. The ‘bad step’ resolved itself<br />

into an easy stride across a cleft in the thinnest part of the ridge.<br />

Throughout we walked in the authentic mountain atmosphere<br />

where a climber feels poised in the middle air between heaven and<br />

earth and knows himself most close to the former. The crest was<br />

narrow and bold, like some of the less riven parts of Cuillin, the<br />

rock clean; deep glens fell away on either side and carried brawling<br />

streams to the sea, which in return sent wheeling round the hills<br />

a sparkling halo of gulls – those birds of inhuman beauty, whose<br />

wild eye and stainless plume seem to me to have been evolved<br />

from the world expressly to embody the true spirit of seaward<br />

mountains and <strong>by</strong> their cry, forlornly echoing among the rocks, to<br />

sound the inner music.—WH Murray<br />

On Druim nan Ramh (Skye)

11<br />

Introduction<br />

The view from Stac Pollaidh

12<br />

The Nature of Scrambling<br />

The Oxford Dictionary definition of ‘scrambling’ is ‘to make way as best one<br />

can over steep or rough ground <strong>by</strong> clambering, crawling, etc.’. It continues with<br />

the unfortunate phrase ‘move hastily and anxiously’. Both of these adverbs are<br />

perfect descriptions of how not to move in mountainous terrain. Even the first<br />

phrase carries undertones of a rather apprehensive nature. I would certainly not<br />

advocate crawling on any scramble! The mountaineer’s definition of scrambling<br />

would probably be ‘movement on a mountain which is too difficult to be reintroduction<br />

Scramblers: A Neglected Breed?<br />

hillwalkers and rock climbers are well defined breeds. They are also well<br />

catered for literature-wise, as is expressly evident <strong>by</strong> the plethora of coffee table<br />

books and guides on these popular pursuits. Many hillwalking guides describe<br />

only a few of the easier scrambles whilst shunting the harder ones aside commenting<br />

that they are ‘beyond the scope of this book’. Rock climbing guides on<br />

the other hand tend to mention only a few of the harder scrambles, often with a<br />

cursory belittlement. It is only relatively recently that guidebooks have appeared<br />

describing scrambles in various localities (for example, Skye, Lochaber and<br />

Wales). This book attempts to cover the best scrambles in Scotland and hopefully<br />

will at the same time raise the activity from its rather condemned position<br />

between the sacred cows of hillwalking and rock climbing.<br />

Somewhere in between the ‘hands in pockets’ rambling of the gentle hillwalker<br />

and the vertical escapades of the serious rock climber lies the middleman<br />

known as the scrambler. The scrambler revels in exposed situations on sound<br />

rock, with a rope usually nowhere to be seen. Of course, scramblers never allow<br />

themselves to reach irreversible situations and an unroped retreat is always<br />

possible. That is, they never allow ropeless to become hopeless!<br />

Many hillwalkers scramble only out of necessity. For instance, most of the<br />

Munros on Skye require some degree of scrambling ability in order to reach<br />

their summits. These gentle scramblers regard the Cuillin of Skye with varying<br />

levels of trepidation, and many would never venture anywhere near them. Other<br />

more serious ‘Munro-baggers’ are cautiously coaxed up the easiest routes <strong>by</strong> experienced<br />

friends or guides, and finally dragged screaming at the end of a rope<br />

up the notorious Inaccessible Pinnacle – the hardest Munro. Some of this group<br />

discover that scrambling isn’t at all bad and may even admit to enjoying it! This<br />

book is partly written for them. It is also written for that last group of hillwalkers<br />

who find scrambling as natural as walking and are undaunted <strong>by</strong> jagged<br />

skyline ridges and soaring rock faces. Finally, this book is for those hillwalkers<br />

who have yet to take their first tentative steps into this area.

introduction<br />

garded as a hillwalk, but too easy to be regarded as a proper rock climb’. A moment’s<br />

thought should make one realise that this is a very subjective statement.<br />

The factors which determine whether a route is a walk or a scramble or a rock<br />

climb are largely dependent on an individual’s experience and ability. When<br />

does a walk become a scramble? When does a scramble become a rock climb?<br />

Both these questions are inherently unanswerable because of their subjective<br />

nature. It could be said that a walk becomes a scramble when you have to start<br />

using your hands, and a scramble becomes a rock climb when you have to start<br />

using a rope. But who is ‘you’? Again the subjective element rears its head. The<br />

mountaineer’s definition of scrambling mentioned above is fair enough but with<br />

the important reservation that it must be applied individually to each person.<br />

Some of the scrambles described in this book are little more than walks;<br />

many are graded as ‘Easy’, ‘Moderate’ or, in extreme cases, even ‘Difficult’<br />

rock climbs. The crucial point is that in good, dry conditions in summer they<br />

could all be climbed unroped – albeit some only <strong>by</strong> experienced mountaineers.<br />

Personally, I regard the upper limit of scrambling as Moderate rock climbing<br />

with perhaps the odd Difficult move thrown in. Others would disagree and say<br />

that Easy rock climbing is the limit; others not even that, such is the nature of<br />

scrambling. It is worth pointing out that even rock climbing grades are in many<br />

respects highly subjective labels. Taking things to extremes, many Severe and<br />

even Extreme rock climbs have been climbed ropeless <strong>by</strong> nimble rock gymnasts,<br />

but to term these as scrambles would be as absurd as calling the Inaccessible<br />

Pinnacle a walk. I recently heard of someone who traversed the Aonach Eagach<br />

ridge in Glencoe (a classic scramble) without using his hands. Apparently, it was<br />

done for a bet with the condition that he kept his hands in his pockets for the<br />

complete traverse. I can think of safer ways of earning £10! To make the suggestion<br />

that the Aonach Eagach ridge is only a walk would be ludicrous.<br />

Leaving the thorny question of what defines a scramble we turn to the philosophy<br />

behind scrambling. Why scramble at all? Scrambling in its purest form<br />

offers the untrammelled freedom of hillwalking, and the exposure and more<br />

immediate excitement of rock climbing, though without the cumbersome clutter<br />

of ropes, slings and assorted paraphernalia (although a rope would be a serious<br />

consideration on some scrambles). The catch in all this is that the consequences<br />

of a slip whilst scrambling unroped in an exposed situation can be fatal. Free<br />

scrambling on exposed rock is potentially one of the most dangerous mountain<br />

activities. The safety limits in scrambling are inherently much narrower than in<br />

hillwalking or roped rock climbing, and the need for the scrambler to know his<br />

or her own limitations is essential before setting out. If in doubt, return another<br />

time with a friend who has some rock climbing experience, a rope, and the<br />

13

14<br />

knowledge to use it safely. Nevertheless, those fortunate individuals who have<br />

felt the exhilaration of unfettered movement over sound, dry rock on a glorious<br />

summer’s day high above the glens will know there is nothing quite like it.<br />

Scrambling Technique (see also Appendix)<br />

introduction<br />

Much of rock climbing technique is obviously applicable to scrambling. This<br />

can be summed up in four ‘rules’:<br />

1 Use your eyes and head to assess the route ahead mentally.<br />

2 Lean out from the rock to preserve balance and a fairly upright posture,<br />

and so that you can see hand and footholds.<br />

3 Keep hands fairly low and climb mainly with your feet. High handholds<br />

should be avoided, if possible.<br />

4 Keep three points of contact, ie never move more than one limb at a<br />

time.<br />

Having said this, note that good mountaineers (and indeed many other people)<br />

will apply these guides intuitively and almost without conscious thought.<br />

Scrambling to most people should be as natural as walking. One only has to<br />

look at children clambering on rocks at the seashore to realise that it is a deeply<br />

ingrained and enjoyable activity dating back far into our evolutionary past. Unfortunately,<br />

as many people grow up they partly lose that childish sense of wonder<br />

and adventure, which is the stimulus of any mountain expedition. If you<br />

have to ask what makes a fully grown adult want to wander along the rocky<br />

crest of a mountain ridge then you will never receive a satisfactory answer.<br />

Those who don’t ask are either mountaineers already or at least understand the<br />

philosophy behind their thinking.<br />

The Grading System<br />

It should firstly be well and truly noted that all the scrambles described in this<br />

book are for dry rock which is ice and snow-free only. That is, in the majority<br />

of cases they would normally be attempted only in summer, and even then only<br />

when the rock is dry. Unfortunately in Scotland this does narrow things down<br />

quite a bit. In the depths of winter a summer scramble is transformed into a major<br />

mountaineering endeavour, with all the associated equipment and techniques<br />

that this encompasses.<br />

Despite the subjective issues previously raised determining the difficulty of<br />

scrambles, the following five-point grading system can be used as a reasonable

introduction<br />

guide. After each grade description, two route examples are given.<br />

Grade 1: Mainly walking, with hands being used for steadying purposes, or<br />

possibly some mild scrambling on certain sections: eg Carn Mor Dearg Arête<br />

(Ben Nevis); Lancet Edge (Ben Alder).<br />

Grade 2: More sustained scrambling with possibly some exposure, but nowhere<br />

serious and most difficulties are avoidable: eg Forcan Ridge (Glen Shiel); Fiacaill<br />

Ridge (Cairngorms).<br />

Grade 3: More serious and exposed scrambling, with some parts possibly involving<br />

Easy rock climbing: eg Aonach Eagach (Glencoe); An Teallach (Northern<br />

Highlands).<br />

Grade 4: Particularly serious and in many places exposed scrambling with<br />

some pitches of Moderate rock climbing: eg Clach Glas-Blaven Traverse (Skye);<br />

Round of Coire Lagan (Skye).<br />

Grade 5: Extremely serious, highly committing and demanding scrambles consisting<br />

mainly of Moderate rock climbing, but with some pitches of a Difficult<br />

standard. For highly experienced scramblers only, and preferably those who<br />

have some rock climbing experience. A rope is highly recommended – even if<br />

not used: eg Tower Ridge (Ben Nevis); Main Cuillin Ridge Traverse (Skye).<br />

The character and quality of a route are to some extent imponderable notions<br />

and have a highly personal basis and bias. A star system is used to describe how<br />

‘good’ a route is, ranging from the best at three stars, down to one star. Because<br />

of the personal nature of route quality there are bound to be many disagreements<br />

on this. Stars are allocated for such factors as length of route, quality of<br />

rock, position, and other more emotive factors. Few people would argue that<br />

many of the routes given above are in the three-star category.<br />

The <strong>Scrambles</strong><br />

Mention scrambling to a Scottish mountaineer and he or she will probably<br />

think of the Cuillin of Skye, undoubtedly the British Mecca of scramblers and<br />

rock climbers. Indeed, Skye is one of the few areas in Britain for which local<br />

scrambling guides have been written. No matter how outstanding and prolific<br />

the scrambling routes are on Skye, however, it is the intention of this book to<br />

cover as much of Scotland as possible, and to concentrate to a large extent on<br />

the really ‘classic’ routes. And, while a few of these may not be most people’s<br />

15

16<br />

introduction<br />

Superb scrambling on the upper section of the north ridge of Sgurr Ghiubsachain<br />

idea of classic, they nevertheless provide worthwhile and exhilarating scrambles.<br />

To a large extent, good scrambles tend to be clustered on one particular<br />

mountain or range of mountains. For instance, no less than three scrambles are<br />

described on the mountain of Buachaille Etive Mor near Glencoe, whilst nine<br />

are described in the whole Glencoe area. In fact, over half the scrambles in the<br />

book are on Skye or in the Ben Nevis and Glencoe area. A good scrambling area<br />

is also invariably a good rock climbing area but the reverse is often not the case.<br />

For example, the Cairngorms contain many excellent rock climbs, but scrambling<br />

opportunities are surprisingly limited.<br />

Scrambling routes generally fall into two categories; those which follow<br />

the crest of the summit ridge of a mountain or range of mountains (known as<br />

a traverse); or those which follow the crest of a subsidiary arête or buttress<br />

usually terminating at the summit of a peak. Of course, some may be a mixture<br />

of both of these. Around 20 traverses are described and include such classics<br />

as Aonach Eagach, Liathach and An Teallach. The remaining 30 or so routes<br />

are all mainly of the second category, including routes such as Curved Ridge<br />

(Buachaille Etive Mor), the Dubhs Ridge (Skye), and the Northern Pinnacles<br />

of Liathach. One important limitation has been placed on this second category<br />

of ‘upward’ routes in that the scrambles are almost all at least 150m (approx<br />

500ft) in length. Thus, short, isolated scrambles of 50m or 100m – no matter

introduction<br />

how good – have rarely been included. Literally thousands of small crags are<br />

dotted about the Highlands, many of which must have good quality, short<br />

scrambling routes. Readers are left to discover these for themselves. Note that<br />

this 150m minimum does not (indeed, cannot) apply to the traverses, some of<br />

which consist largely of walking with only small pockets of scrambling, such<br />

as the Beinn Alligin Traverse. Chimney or gully routes have been purposely<br />

omitted due to inherent dangers such as stone-fall, wet or greasy rock and the<br />

presence of large snow pockets which often linger well into the summer season.<br />

These factors tend to make gully scrambling a thoroughly wet, cold and miserable<br />

experience. Gully climbing only really comes into its own in winter under<br />

appropriate freezing conditions when there is less likelihood of falling water<br />

from above. Also, from an aesthetic viewpoint, gully climbing severely restricts<br />

views and can be rather a claustrophobic experience.<br />

For convenience the book has been divided into four parts, each covering a<br />

particular area. These are:<br />

1 Skye and other islands (Routes 1–17)<br />

2 Ben Nevis and Glencoe (Routes 18–31)<br />

3 North of the Great Glen (Routes 32–44)<br />

4 South and east of the Great Glen (Rout 45–50).<br />

Each part is further subdivided as appropriate.<br />

Other Routes<br />

At the end of each part, an additional selection of routes has been outlined, but<br />

detailed descriptions of these are not given. The majority of these ‘other routes’<br />

are either in extremely remote country, or of a Grade 4/5 nature (or harder). In<br />

some cases, such as the Beinn Lair cliffs north of Loch Maree, they are a combination<br />

of these. Some detailed route descriptions can be found in local rock<br />

climbing guides but for many, no detailed descriptions are available and some<br />

degree of pioneering spirit is required. These extra routes, therefore, can be seen<br />

as an extension to the 50 routes already described and provide much scope for<br />

experienced scramblers wishing to extend their repertoire.<br />

Route Measurements<br />

Accompanying each route is information relating to distance, height and time.<br />

Unless otherwise stated, the distance given refers to the total distance travelled<br />

in order to complete the route (including a return to base), and the figure is<br />

17

18<br />

given in both miles and kilometres<br />

rounded to the nearest whole unit.<br />

The ‘total ascent’ similarly refers to<br />

the total amount of height climbed in<br />

order to complete the route – ie it is<br />

not just the height of the actual scramble<br />

(which would make little sense<br />

on a traverse anyway). This is given<br />

in metres and feet and in most cases<br />

has been rounded to the nearest 50m.<br />

Finally, the time for the route is again<br />

the total for the whole route including<br />

stops. For this reason, and because<br />

of subjective variation in walking<br />

and climbing speeds, a time range is<br />

given (eg 5–7 hours). This will not,<br />

of course, apply to fell-runners or to<br />

people who spend two hours sunning<br />

themselves on the summit of Sgurr<br />

nan Gillean!<br />

introduction<br />

Sketch-maps<br />

Each route is clearly indicated on a<br />

sketch map but there may be more<br />

than one route indicated on any<br />

particular map. The maps show the<br />

main topographic features in diagrammatic<br />

form but should not be used in<br />

place of a proper Ordnance Survey<br />

map. Munros (not Tops) are indicated<br />

<strong>by</strong> black triangles, while Corbetts<br />

(mountains over 2,500ft ) are shown<br />

<strong>by</strong> heavy white triangles. Other summits<br />

are marked <strong>by</strong> black circles. The<br />

main ridges are shown <strong>by</strong> heavy black<br />

lines and cliffs/steep, rocky ground <strong>by</strong><br />

closely spaced thin black lines.<br />

Steep scrambling on the south peak of<br />

the Cobbler

committed to publishing well written books worth reading<br />

luath press takes its name from Robert Burns, whose little collie Luath<br />

(Gael., swift or nimble) tripped up Jean Armour at a wedding and gave<br />

him the chance to speak to the woman who was to be his wife and the<br />

abiding love of his life. Burns called one of the ‘Twa Dogs’<br />

Luath after Cuchullin’s hunting dog in Ossian’s Fingal.<br />

Luath Press was established in 1981 in the heart of<br />

Burns country, and is now based a few steps up<br />

the road from Burns’ first lodgings on<br />

Edinburgh’s Royal Mile. Luath offers you<br />

distinctive writing with a hint of<br />

unexpected pleasures.<br />

Most bookshops in the uk, the us, Canada,<br />

Australia, New Zealand and parts of Europe,<br />

either carry our books in stock or can order them<br />

for you. To order direct from us, please send a<br />

£sterling cheque, postal order, international money<br />

order or your credit card details (number, address of<br />

cardholder and expiry date) to us at the address below. Please add post<br />

and packing as follows: uk – £1.00 per delivery address; overseas<br />

surface mail – £2.50 per delivery address; overseas airmail – £3.50 for<br />

the first book to each delivery address, plus £1.00 for each additional<br />

book <strong>by</strong> airmail to the same address. If your order is a gift, we will<br />

happily enclose your card or message at no extra charge.<br />

543/2 Castlehill<br />

The Royal Mile<br />

Edinburgh EH1 2ND<br />

Scotland<br />

Telephone: +44 (0)131 225 4326 (24 hours)<br />

email: sales@luath.co.uk<br />

Website: www.luath.co.uk