NCC Magazine - Summer 2022

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

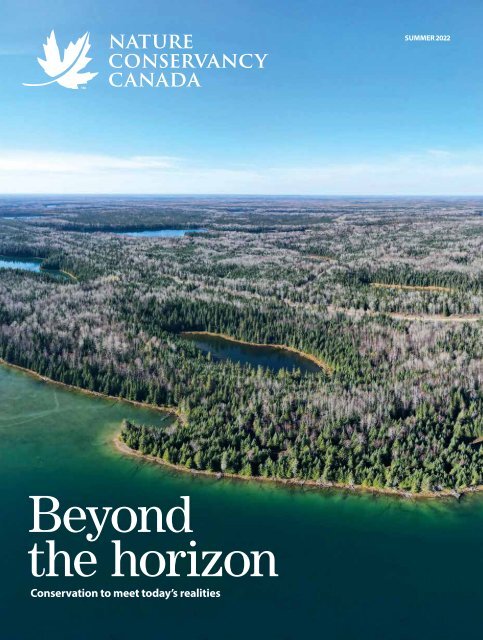

SUMMER <strong>2022</strong><br />

Beyond<br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

the horizon<br />

Conservation to meet today’s realities<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

WINTER 2021 1

SUMMER <strong>2022</strong><br />

CONTENTS<br />

Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

4 Accelerating conservation at new scales<br />

Doubling the pace of our conservation impact.<br />

6 Dr. Bill Freedman Nature Reserve<br />

This nature reserve outside Halifax commemorates a long-term <strong>NCC</strong> volunteer.<br />

7 Share your nature pics<br />

The Big Backyard BioBlitz is back!<br />

7 Connect and recharge<br />

Minister of Environment and Climate Change, Steven Guilbeault,<br />

describes how nature revives him.<br />

8 Big, bold and impactful<br />

Expanding the pace, scale and scope of conservation.<br />

12 North American river otter<br />

Nature’s water clowns are making a comeback.<br />

14 Force for nature<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> board member Rob Prosper sees the potential to accelerate conservation<br />

through Indigenous-led protected areas.<br />

16 Project updates<br />

Investing in our future, MB; Keep The Rock Rugged, NL; a legacy of care, AB.<br />

18 A love letter to the mountains<br />

How the mountains changed one woman’s life.<br />

Digital extras<br />

Check out our online magazine page with<br />

additional content to supplement this issue,<br />

at nccmagazine.ca.<br />

Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

245 Eglinton Ave. East, Suite 410 | Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 3J1<br />

magazine@natureconservancy.ca | Phone: 416.932.3202 | Toll-free: 877.231.3552<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) is the country’s unifying force for nature. We seek solutions to the<br />

twin crises of rapid biodiversity loss and climate change through large-scale, permanent land conservation.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> is a registered charity. With nature, we build a thriving world.<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada <strong>Magazine</strong> is distributed to donors and supporters of <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

TM<br />

Trademarks owned by the Nature Conservancy of Canada.<br />

FSC is not responsible for any calculations on<br />

saving resources by choosing this paper.<br />

Printed on Enviro100 paper, which contains 100% post-consumer fibre, is EcoLogo, Processed Chlorine Free<br />

certified and manufactured in Canada by Rolland using biogas energy. Printed in Canada with vegetablebased<br />

inks by Warrens Waterless Printing. This publication saved 156 trees and 51,445 litres of water*.<br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

GENERATED BY: CALCULATEUR.ROLLANDINC.COM. PHOTO: JON FELDGAJER. COVER: ANDREW WARREN.<br />

*<br />

natureconservancy.ca

Keep The Rock Rugged<br />

Big, bold and boreal<br />

Featured<br />

Contributors<br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

TOP TO BOTTOM: GENEVIÈVE LESIEUR; ANDREW WARREN; NIV SHIMSHON.<br />

It has been a busy time here at the Nature Conservancy<br />

of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>), with so much great work underway to<br />

accelerate conservation across the country. There are many<br />

exciting successes to celebrate, but one that stands out to me<br />

from recent months is a project we’ve nicknamed “big, bold and<br />

boreal.” This Earth Day, I was delighted to join colleagues and<br />

partners to launch our Boreal Wildlands project.<br />

It’s certainly big, and bold: it’s the largest project the Nature<br />

Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) has undertaken, and the biggest<br />

private land conservation project ever in this country. And it’s<br />

boreal, spanning nearly 1,500 square kilometres in Ontario’s<br />

boreal forest — part of the largest forest system on the planet.<br />

In this issue, you’ll read about why landscape-scale protected<br />

areas are crucial if we are to tackle the global challenges of<br />

climate change and biodiversity loss. Working from coast to<br />

coast to coast, <strong>NCC</strong> aims to double the pace of conservation<br />

in the next few years. In the face of these challenges, nature<br />

offers us real solutions. That is why we are working at an<br />

unprecedented pace now to conserve the natural areas that<br />

are our life support systems.<br />

Just as nature offers us solutions to the world’s most pressing<br />

issues, collaboration is the key to getting more nature into our<br />

lives. The Boreal Wildlands is a $46-million project. With the<br />

support of our partners, as well as individual donors and foundations,<br />

we have raised more than two-thirds of the funds. This<br />

spring, we launched a fundraising campaign to close the project.<br />

We need you! To learn more about how you can support the<br />

Boreal Wildlands, or other projects, visit borealwildlands.ca.<br />

Thank you as always for your support,<br />

Catherine Grenier<br />

Catherine Grenier<br />

President and CEO, Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

Brian Banks is a writer,<br />

editor, geographer and<br />

perpetually aspiring<br />

naturalist devoted to<br />

experiencing and<br />

advocating for the<br />

animals and plants with<br />

whom we co-exist and<br />

the environment on<br />

which we depend.<br />

Jacqui Oakley has<br />

illustrated for The New<br />

York Times, Reebok,<br />

Rolling Stone and<br />

National Geographic<br />

with her art shown in<br />

Toronto, L.A. and<br />

Shanghai. After living in<br />

Zambia, Bahrain and<br />

England, she now lives<br />

in Hamilton, Ontario.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SUMMER <strong>2022</strong> 3

COAST TO<br />

COAST<br />

Vidal Bay, ON<br />

Accelerating<br />

conservation<br />

at new scales<br />

In the face of climate change and biodiversity loss, the<br />

Nature Conservancy of Canada is conserving more, faster<br />

T<br />

he Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) is working at an<br />

unprecedented scale to deliver conservation impact. As the<br />

largest private land conservation organization in the country,<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> is unlocking solutions to support Canada’s targets to conserve<br />

30 per cent of our lands and waters by 2030.<br />

Accelerating conservation means <strong>NCC</strong> is delivering conservation<br />

impact faster and more extensively than ever before. We’re not only<br />

putting our energy and ambition into privately protected and conserved<br />

areas, we’re helping others contribute toward Canada’s 30 by 30 goal<br />

and lending our expertise in conserving lands of high natural value.<br />

We can’t do this alone, and we are committed to collaboration,<br />

consultation and bringing people together for change.<br />

HELPING NATURE CONTINUE TO SUPPORT LIFE<br />

When habitats are integrated and connected, and entire natural systems<br />

are conserved, nature can better deliver essential services that support<br />

life. By connecting landscapes that provide nature-based solutions, we’re<br />

taking care of places that clean our water, purify our air, absorb and<br />

store carbon, and support food security. Protecting connected habitat<br />

also supports the species that live there, including close to one-third<br />

of Canada’s species at risk.<br />

Learn more about the projects<br />

that are helping accelerate<br />

conservation in Canada and<br />

how you can help<br />

natureconservancy.ca/<br />

accelerate.<br />

ANDREW WARREN.<br />

4 SUMMER <strong>2022</strong> natureconservancy.ca

PROJECTS THAT ARE MAKING A DIFFERENCE<br />

How do we do it? Through projects large and small, and through partnerships such as the Government of Canada’s Natural Heritage Conservation Program,<br />

across the country. Here are some of the projects undertaken over the past two years that have added to our conservation impact.<br />

Qat'muk, BC<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> was invited to help deliver the complete and<br />

permanent extinguishment of all tenures and development<br />

rights in the Jumbo Valley, and to support the Ktunaxa<br />

Nation Council (KNC) in their ongoing conservation planning<br />

for the establishment of an Indigenous Protected and<br />

Conserved Area. <strong>NCC</strong> is honoured to work with the KNC to<br />

help them achieve their vision of fully protecting Qat'muk.<br />

Thaidene Nëné, NWT<br />

Sometimes, the smallest projects<br />

carry the biggest impact. Within a vast<br />

area of cultural and ecological significance,<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> purchased a private holding<br />

of about one hectare, transferring it to<br />

Parks Canada. This removed an obstacle<br />

to completing Thaidene Nëné National<br />

Park Reserve, influencing the conservation<br />

of over 14,000 square kilometres in<br />

keeping with the wishes of local<br />

Indigenous communities.<br />

Buffalo Pound, SK<br />

You helped us conserve the seven<br />

kilometres of shoreline around<br />

Buffalo Pound Lake for the sake of<br />

threatened grasslands and species<br />

at risk. This natural area provides<br />

drinking water for 25 per cent of the<br />

province’s population.<br />

TOP TO BOTTOM: PAT MORROW; PARKS CANADA; <strong>NCC</strong>; JASON BANTLE; MIKE DEMBECK; MIKE DEMBECK.<br />

Vidal Bay, ON<br />

The project comprises more than 7,600 hectares of shoreline and forest, redefining<br />

landscape-scale conservation in southern Ontario. The forests, wetlands and alvars found<br />

here capture and store nearly 23,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide a year; the equivalent of<br />

taking nearly 5,000 cars off the road annually.<br />

Chignecto<br />

Isthmus, NS/NB<br />

The Chignecto Isthmus is the<br />

narrow strip of land connecting<br />

mainland Nova Scotia to New<br />

Brunswick and the rest of North<br />

America. Since 2010, you have<br />

helped us conserve just over<br />

2,200 hectares on both sides<br />

of the border, continuing to<br />

steward and expand upon our<br />

existing conservation efforts<br />

along this critical wildlife corridor.<br />

Krieg Property, QC<br />

The Krieg property in the Green Mountains Nature Reserve<br />

is an idyllic natural area full of life. Its mature forests are home<br />

to eastern wood-pewee, a small, threatened songbird. Several<br />

species of spring salamanders also live in the area’s streams.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> hopes to connect the property to the Green Mountains<br />

Nature Reserve, a place of high biodiversity and a well-used<br />

outdoor recreation area in Quebec.<br />

Upper Ohio, NS<br />

The conservation of rare Acadian<br />

forest, over 25 kilometres of lake<br />

shoreline and 130 hectares of freshwater<br />

wetlands in Upper Ohio make this<br />

project the third-largest acquisition in<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>’s 50-year history in the province.1<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SUMMER <strong>2022</strong> 5

BOOTS ON<br />

THE TRAIL<br />

Murphy Cove Rd<br />

<br />

N<br />

★<br />

Prospect<br />

Bay<br />

The<br />

Alley<br />

Dr. Bill Freedman<br />

Nature Reserve<br />

Prospect Bay Rd<br />

Phantom<br />

Cove<br />

Mullins<br />

Cove<br />

Hardiman<br />

Cove<br />

Dr. Bill Freedman<br />

Nature Reserve<br />

A majestic coastal landscape that includes eight types of habitat<br />

Dr. Bill Freedman was an ecologist and former Chair of the<br />

Department of Biology at Dalhousie University, where he also<br />

served as professor emeritus. He was also a major figure with the<br />

Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) as a board member and<br />

volunteer for more than 25 years. Dr. Bill, as he was affectionately<br />

known, passed away in 2015. The Dr. Bill Freedman Nature<br />

Reserve is dedicated to his memory and his contributions to <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

The reserve is located just 23 kilometres southwest of Halifax, Nova<br />

Scotia. The coastal barrens landscape juts out into the Atlantic<br />

Ocean and is flanked by picturesque Shad Bay and Prospect Bay.<br />

Natural features include eight types of habitat: white spruce coastal<br />

forest, old fields, bogs, granite barrens, boulder/cobble shoreline,<br />

rocky shoreline, cliffs and open ocean.<br />

The popular 7.6-kilometre (round-trip) High Head Trail passes<br />

through four sections of <strong>NCC</strong>’s 133-hectare nature reserve. This<br />

moderately challenging trail winds in and out of forested<br />

pathways onto rocky outcrops, which provide breathtaking<br />

views of the open ocean. Nova Scotia’s jagged southern<br />

coastline and several rocky islands can be seen in the distance.<br />

The granite barrens found here purify massive amounts of ground<br />

water prior to its re-entry into the ocean. With its fresh sea breezes<br />

and panoramic vistas, the High Head Trail is a wonderful hike in the<br />

summertime and an ideal place for birdwatching.<br />

STAY SAFE<br />

On your journey, it is important to leave no trace behind and to<br />

stay on the well-travelled path outlining the coast. It is advised<br />

not to venture inland toward sensitive ecological habitat nor too<br />

close to the rocky cliffs.1<br />

Learn more at natureconservancy.ca/billfreedman.<br />

LEGEND<br />

-- High Head Trail<br />

★ Trailhead<br />

SPECIES TO SPOT<br />

• balsam fir<br />

• crowberry<br />

• harlequin duck<br />

• mountain holly<br />

• red maple<br />

• ruffed grouse<br />

• snowshoe hare<br />

• speckled alder<br />

• white birch<br />

• white-tailed deer<br />

• wild raisin<br />

MAP: JACQUES PERRAULT. PORTRAIT: JOEL KIMMEL. PHOTOS TOP TO BOTTOM: ROBERT MCCAW; MIKE DEMBECK; ANDREW HERYGERS/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF.<br />

6 SUMMER <strong>2022</strong> natureconservancy.ca

ACTIVITY<br />

CORNER<br />

BACKPACK<br />

ESSENTIALS<br />

L TO R: BRENT CALVER; COURTESY ENVIRONMENT AND CLIMATE CHANGE CANADA.<br />

Share your<br />

nature pics<br />

This summer, participate in<br />

the Big Backyard BioBlitz<br />

Did you know that photographing the plants,<br />

animals and fungi around you can be an easy<br />

way to connect with nature and contribute to<br />

science and conservation?<br />

This summer, the Nature Conservancy of<br />

Canada is once again running its annual Big<br />

Backyard BioBlitz. You can join the event and<br />

share your species observations of the nature<br />

around you. Conserving nature requires lots<br />

of information. Your observations may be used<br />

by scientists to help them understand the<br />

distribution of species.<br />

Best of all, you’re volunteering your time to<br />

help increase knowledge about the species<br />

in your area.<br />

How to participate in the Big Backyard BioBlitz:<br />

1. Sign up at natureconservancy.ca/bbb.<br />

2. Receive your step-by-step instructions to<br />

ensure your observations are included in the<br />

group effort.<br />

3. Tag team with family and friends, or make it<br />

your me-time with nature.<br />

Whether you’re new to bioblitzes or a seasoned<br />

regular, join in the effort!<br />

Connect<br />

and recharge<br />

The Honourable Steven Guilbeault, Minister of Environment<br />

and Climate Change Canada, is motivated by nature’s benefits<br />

Since my teenage years, I have always found myself drawn to nature.<br />

When out in nature, there is not one particular item in my backpack,<br />

because I tend to vary where I go and for how long. I love to take<br />

a camera with me to document the beautiful landscapes and breathtaking views<br />

that we are so fortunate to have in our country. Whether hiking in the beautiful<br />

Chic-Choc Mountains in the Gaspé Peninsula, canoeing in Ontario, kayaking in<br />

the middle of a pod of white-sided dolphins in northern BC or kayaking during<br />

my honeymoon in the Mingan Archipelago National Park Reserve, nature has<br />

had a very special place in my heart. For as long as I can remember, I have had<br />

essential “annual appointments” with nature. I get a sense of calmness when<br />

I am outdoors, and I feel the need to protect it as much as possible.<br />

My backpack may not be big enough to fit the next essential item — my family.<br />

But they are an important part of my visits in nature. Whether by myself, with my<br />

wife or my kids, spending time in nature allows me to disconnect from our family’s<br />

busy life and reconnect with them and the amazing nature that our country has to<br />

offer. Simply being in nature allows me to slow down and recharge.<br />

And don’t just take it from me; doctors from the BC Parks Foundation’s PaRx<br />

program prescribe a “nature pass” to our country’s parks and natural areas to<br />

improve people’s mental and physical health by connecting them with nature.<br />

Nature acts as a source of calmness but also a source of motivation. Nature also<br />

has incredible potential to boost resilience, mitigate greenhouse gas emissions,<br />

grow national economies and achieve for nature and for society in general.<br />

When we protect nature, everyone benefits.1<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SUMMER <strong>2022</strong> 7

Big,<br />

bold<br />

AND<br />

impactful<br />

Faced with the urgent crises of rapid biodiversity loss and climate<br />

change, we must expand the pace, scale and scope of conservation<br />

BY Brian Banks<br />

ANDREW WARREN.<br />

8 SUMMER <strong>2022</strong> natureconservancy.ca

Boreal Wildlands, the largest single private<br />

conservation project ever undertaken in Canada.<br />

Put a map of Ontario on the<br />

wall, throw a dart at its geographical<br />

centre, and if your aim is true,<br />

that dart will hit smack dab in<br />

the boreal forest, somewhere near<br />

Hornepayne, a forestry town 500 kilometres<br />

northeast of Thunder Bay.<br />

For two years, that part of the map has been<br />

a special focus for Kristyn Ferguson, the Nature<br />

Conservancy of Canada’s (<strong>NCC</strong>’s) program director<br />

for large landscapes in Ontario. Specifically,<br />

a 1,450-square-kilometre (145,000-hectare) area<br />

to the west and south of the community of Hearst,<br />

about 900 kilometres north of Toronto. The lands<br />

here are rich in boreal forest habitat, pristine<br />

lakes and rivers, and carbon-storing peatlands.<br />

In April, on Earth Day, <strong>NCC</strong> unveiled a fundraising<br />

campaign to complete the conservation<br />

of these lands, covering an area more than twice<br />

the size of the city of Toronto. When complete,<br />

the project will be the largest single private conservation<br />

project ever undertaken in Canada,<br />

dubbed the Boreal Wildlands.<br />

“The first time I had a chance to visit the<br />

property was in late September of 2021,” says<br />

Ferguson. “It was peak fall, where all the poplar<br />

and birch leaves turn yellow against the dark<br />

conifers. From any bit of height, looking out at<br />

the forest, it just goes on forever. The lakes look<br />

glacial because of their bright greenish colour.<br />

This place is mesmerizing.”<br />

Boreal Wildlands’ significance is both tangible<br />

and symbolic.<br />

The property, originally held by Domtar, with<br />

whom <strong>NCC</strong> negotiated an option to purchase<br />

the site, has tremendous conservation value. It<br />

is home to threatened woodland caribou, other<br />

large mammals like black bear, lynx, wolf and<br />

moose, and provides nesting, breeding and migratory<br />

stopover habitat for a multitude of birds.<br />

At the same time, the project epitomizes how<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>, as Canada’s leading private conservation<br />

organization, is responding to the crises of rapid<br />

biodiversity loss and climate change by expanding<br />

the pace, scale and scope of its work — adding<br />

a focus on larger conservation projects in all<br />

regions that builds on its long history of protecting<br />

crucial habitat in southern Canada.<br />

natureconservancy.ca SUMMER <strong>2022</strong> 9

Left: Boreal Wildlands, ON. Right: Qat'muk, BC<br />

This focus, a cornerstone of <strong>NCC</strong>’s new<br />

roadmap for the next eight years, will see<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> protect more land, faster, either through<br />

traditional fee simple acquisition, as with<br />

Boreal Wildlands, or by lending its expertise<br />

— in securing private financing or acquiring<br />

resource development rights, say — to help<br />

projects led by governments, Indigenous<br />

communities or other partners.<br />

The goal: to double <strong>NCC</strong>’s impact by 2030,<br />

conserving an additional one million hectares<br />

and delivering $1.5 billion of new conservation<br />

outcomes. In the process, <strong>NCC</strong> will help<br />

Canada achieve its pledge, as a member of<br />

the international High Ambition Coalition for<br />

Nature and People, to protect 30 per cent of<br />

this country’s lands and waters by 2030.<br />

“Our new strategic plan lays out our toolkit<br />

and our values, and a recognition that with<br />

climate change and biodiversity loss, we have a<br />

big part to play,” says Nancy Newhouse, <strong>NCC</strong>’s<br />

regional vice-president in British Columbia.<br />

It’s an approach endorsed by Mike Wong,<br />

North American regional vice-chair of the<br />

International Union for Conservation of Nature’s<br />

World Commission on Protected Areas.<br />

“Protected areas are one of the best conservation<br />

tools in the world,” says Wong, who<br />

is based in Gatineau, Quebec. “When you have<br />

large intact areas that are well-managed, you<br />

conserve both the diversity as well as the carbon<br />

that is stored in that protected ecosystem.”<br />

Supporting partners<br />

One of <strong>NCC</strong>’s longstanding strengths is its<br />

ability to bring together landowners, donors,<br />

fundraising partners, governments, Indigenous<br />

communities and other non-profits to protect<br />

nature. But traditionally, the outcomes include<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> owning the land. Taking a supporting role<br />

on other groups’ projects isn’t entirely new,<br />

but according to Dawn Carr, <strong>NCC</strong>’s director of<br />

strategic conservation, it’s been mainly ad hoc.<br />

When you have large intact areas that<br />

are well-managed, you conserve both the<br />

biodiversity as well as the carbon that is<br />

stored in that protected ecosystem.<br />

Mike Wong, North American regional vice-chair of the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s<br />

World Commission on Protected Areas<br />

“We’ve not done a lot of proactive outreach<br />

with potential partners to ask, ‘What<br />

conservation objectives do you have that<br />

our abilities or capabilities might be able to<br />

support?’” says Carr. “The more we ask, the<br />

more opportunities will surface to support<br />

lasting conservation.”<br />

Increasingly, <strong>NCC</strong> is looking to scale up<br />

its collaboration with partners in a more<br />

proactive manner.<br />

A prime example that demonstrates <strong>NCC</strong>’s<br />

potential in a supporting role are the negotiations<br />

now underway between the Ktunaxa<br />

Nation and the BC government to establish<br />

an Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area<br />

(IPCA) in the Central Purcell Mountains.<br />

The IPCA will encompass an area known as<br />

Qat'muk, a sacred landscape the Ktunaxa<br />

hold as the spiritual home of the grizzly bear.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> was invited to work with the Ktunaxa<br />

Nation Council in 2019 to help them achieve<br />

their vision of fully protecting Qat'muk — an<br />

area rich in biodiversity that includes the<br />

Jumbo Valley and surrounding watersheds.<br />

The core threat to the area was a proposed<br />

ski resort in the Jumbo Valley, which the<br />

Ktunaxa and their supporters had been<br />

fighting against for 30 years. After decades of<br />

legal battles, an opportunity arose to negotiate<br />

a settlement with the developer and open<br />

the door to develop an IPCA.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> first assisted the Ktunaxa in developing<br />

the ecological rationale for protection,<br />

which was necessary to secure funding for the<br />

IPCA creation. It then also acted as the negotiator<br />

on behalf of the Ktunaxa in talks to extinguish<br />

the developer’s tenures and development<br />

rights associated with the resort. Today,<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> is poised to assist the Ktunaxa with conservation<br />

planning, providing mapping and<br />

ecological data for the Qat'muk IPCA once its<br />

details have been finalized.<br />

“The Ktunaxa are leading the government-to-government<br />

conversations about<br />

what Qat'muk will look like,” says Newhouse.<br />

“Our role there now is to be a support to the<br />

Nation as requested.”<br />

The Qat'muk example also underscores<br />

that working alongside Indigenous communities<br />

more generally, in different capacities,<br />

will be a growing area of emphasis for <strong>NCC</strong> as<br />

it expands its large landscapes work. The Boreal<br />

Wildlands project is a case in point. While<br />

it won’t be an IPCA, the project area includes<br />

L TO R: ANDREW WARREN; PAT MORROW.<br />

10 SUMMER <strong>2022</strong> natureconservancy.ca

L TO R: CLAUDE CÔTÉ; GLENN BARTLEY.<br />

the traditional territories of many Indigenous<br />

Nations and communities within Treaty 9.<br />

“We’re making sure we’re speaking with all<br />

of the communities, learning how they’ve<br />

used the site historically, how they might like<br />

to use it going forward,” says Ferguson.<br />

“We’re in the very early days of developing<br />

partnerships that <strong>NCC</strong> intends to be longterm,<br />

respectful, meaningful and that bring<br />

benefit to the communities.”<br />

Protect and connect<br />

Protecting any parcel of land, large or small,<br />

that provides essential habitat for species at<br />

risk is critical to help stem the loss of species<br />

and conserve overall biodiversity.<br />

But from an ecological standpoint, largescale<br />

projects play a unique role by ensuring<br />

the existence of large expanses of connected,<br />

protected habitat. These areas are critical<br />

for larger animals that migrate seasonally or<br />

require big territorial ranges for feeding<br />

and reproduction. In the face of a changing<br />

climate, they also provide a measure of resilience,<br />

giving many species of animals and<br />

plants the opportunity to adapt and adjust<br />

their location over time.<br />

The Green Mountains Nature Reserve in<br />

the Appalachian corridor of southeastern<br />

Quebec is a prime example of the value of<br />

large-scale connectivity in <strong>NCC</strong>’s portfolio.<br />

Established in 2008, the reserve continues<br />

to grow thanks to the donation or purchase<br />

of adjoining parcels of land. It now measures<br />

close to 8,000 hectares in size. It also is directly<br />

linked to protected areas south of the<br />

U.S. border.<br />

“If you look at a satellite map, you can see<br />

that every piece of land around [the reserve]<br />

is cities or farms, not much forest. So, it’s<br />

very important to keep that corridor for<br />

the migration of species from the south<br />

to the north with climate change,” says Cynthia<br />

Patry, <strong>NCC</strong>’s project manager for the<br />

Northern Green Mountains. “We still have<br />

wide-ranging mammals that are crossing the<br />

border and using that corridor, like lynx,<br />

moose and bears. Outside of that corridor,<br />

there are no lynx, so we really want to<br />

maintain it for them.”<br />

The Green Mountains Nature Reserve is<br />

one of a handful of <strong>NCC</strong>’s existing large-scale<br />

protected areas located in Canada’s south.<br />

The newest in this category is Hastings Wildlife<br />

Junction, a planned 8,000-hectare acquisition<br />

consisting of significant forests and wetlands<br />

located between the towns of Belleville<br />

and Bancroft in southeastern Ontario. However,<br />

in future, given the density of settlement<br />

in the south, <strong>NCC</strong> expects most of Canada’s<br />

large-scale protected area opportunities<br />

will lie farther north.<br />

This reality, coupled with the fact that<br />

much more of the land in Canada’s North is<br />

Crown land, also explains why <strong>NCC</strong>’s role<br />

in such projects is likely to be that of a supporting<br />

partner. As Newhouse explains, ownership<br />

of such lands will stay with the Crown,<br />

but in many cases, as with Qat'muk as well as<br />

another recent project in BC, the Tenh Dzetle<br />

Conservancy, made possible with the relinquishing<br />

of mineral rights, <strong>NCC</strong>’s role will be to<br />

“create agreements whereby when [such] privately<br />

held tenures are relinquished, there’s a<br />

parallel process that creates a protected area.”<br />

IUCN’s Wong says he is happy to learn that<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> is looking at a different way of doing<br />

things, as it represents the kind of approach<br />

that everyone — individuals, governments,<br />

Green Mountains Nature Reserve, QC<br />

companies, NGOs and other stakeholders —<br />

needs to embrace if Canada and the world are<br />

going to achieve their commitments to protect<br />

30 per cent of their territories by 2030.<br />

Wong highlights the failure of most countries<br />

to reach the IUCN’s previous target of<br />

protecting 17 per cent of their lands by 2020.<br />

In Canada’s case, we’re now at just 13.5 per<br />

cent. “If we didn’t make the 17 per cent target,<br />

how do we get to 30 per cent?” he asks.<br />

“You have to do things differently, right?”<br />

Ferguson agrees: “We’re so proud of everything<br />

that <strong>NCC</strong> has been able to accomplish<br />

over the last 60 years with the help of our<br />

supporters. But we recognize that we are at<br />

a crisis point, when we need to think bigger<br />

and think differently, bring in different<br />

partners and collaborate.”<br />

Recalling her visit to Boreal Wildlands, she<br />

describes standing on the banks of the Shekak<br />

River alongside Councillor Wayne Neegan of<br />

the Constance Lake First Nation, <strong>NCC</strong>’s escort<br />

on the land. As the river rushed past on its<br />

way to Hudson Bay, Neegan pointed out<br />

moose tracks at the water’s edge and demonstrated<br />

how he calls moose when hunting.<br />

About that moment, and others since, Ferguson<br />

reflects: “I think we all recognize we’re<br />

headed in the right direction, working together<br />

on initiatives that are making a conservation<br />

impact at scale. We’re doing it for the land<br />

and the caribou, but also for people. We’re all<br />

realizing we’re not separate from nature; we<br />

are a part of nature. So, every time we’re helping<br />

nature, we’re actually helping ourselves.”1<br />

HELP MAKE<br />

THE BOREAL<br />

WILDLANDS<br />

A REALITY<br />

At more than twice the size<br />

of the city of Toronto, once<br />

complete Boreal Wildlands will be<br />

the largest private land conservation<br />

project in Canada’s history.<br />

The Nature Conservancy of<br />

Canada invites you to join us in<br />

making conservation history.<br />

The Boreal Wildlands will<br />

ensure the future of more than<br />

1,300 kilometres of rivers and<br />

streams, vast carbon-storing<br />

peatlands and seemingly endless<br />

stretches of interior forest. Boreal<br />

Wildlands alone stores more<br />

than 192 million tonnes of CO2,<br />

equivalent to the average lifetime<br />

emissions of three million cars,<br />

demonstrating the direct positive<br />

impact this site’s conservation<br />

could have on stemming the global<br />

climate and biodiversity crises.<br />

Having successfully raised<br />

two-thirds of our fundraising<br />

target, we now need you to<br />

join us in this historic campaign.<br />

Learn more at borealwildlands.ca.<br />

The Boreal Wildlands is home to<br />

birds like Canada warbler.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SUMMER <strong>2022</strong> 11

SPECIES<br />

PROFILE<br />

North American<br />

river otter<br />

Found throughout North America, river otter populations are stable<br />

after recovering from significant declines in the 19 th and 20 th centuries<br />

JOE BLOSSOM/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO.<br />

12 SUMMER <strong>2022</strong><br />

natureconservancy.ca

APPEARANCE<br />

River otters can measure up to 1.4<br />

metres from nose to tail, and weigh up<br />

to 14 kilograms. They have brown, waterrepellent<br />

fur, webbed feet and long, strong<br />

tails that help propel them through water. Their<br />

underbody is usually lighter in colour. Their tiny<br />

ears close under water, and their thick fur<br />

helps keep them warm in cold water. Long<br />

whiskers help them find prey, such as<br />

fish, clams, insects and other<br />

aquatic animals.<br />

Cherry Meadows, BC<br />

Taking a peek<br />

RANGE<br />

River otters can be found<br />

throughout North America. In<br />

Canada, they are found in every<br />

province and territory, but have<br />

only recently returned to Prince<br />

Edward Island after disappearing<br />

at the beginning of the<br />

20 th century.<br />

HABITAT<br />

River otters can live in a variety of<br />

aquatic habitats, including rivers, lakes and<br />

large creeks. They also thrive outside of water<br />

and can sometimes be seen playing in snow or<br />

sliding down muddy hills. Playing helps strengthen<br />

social bonds and gives younger otters a chance to<br />

practise hunting skills.<br />

Their burrows are typically found near water<br />

and are often built to be accessible<br />

from both land and water.<br />

What <strong>NCC</strong> is doing<br />

to protect habitat<br />

for this species<br />

River otter populations declined<br />

significantly throughout the late<br />

1800s due to over-harvesting and<br />

water pollution. However, through<br />

conservation management and<br />

reintroduction efforts, populations<br />

have recuperated and are now<br />

considered stable or increasing.<br />

ICONS: CORY PROULX. <strong>NCC</strong>; ALAMY STOCK PHOTO.<br />

BIOLOGY<br />

River otters breed between late<br />

winter and early spring. Although they can<br />

reproduce annually, it is more likely for this<br />

species to give birth every two years. Female otters<br />

give birth to between one and six pups. The pups are<br />

born blind and spend the first month of their lives in<br />

their dens with the female. After two months, the<br />

female teaches the now-sighted pups how to swim.<br />

This species does not hibernate and remains<br />

active under frozen water by breathing<br />

through breaks in the ice. River otters can<br />

hold their breath underwater for up to<br />

eight minutes.<br />

River otters need healthy aquatic<br />

habits to survive. The Nature<br />

Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>)<br />

continues to protect habitat across<br />

Canada where river otters live. One<br />

example is <strong>NCC</strong>’s Cherry Meadows<br />

property, near Kimberley, BC.<br />

Located in the Rocky Mountain<br />

Trench, this area features extensive<br />

wetlands — perfect habitat for<br />

nature’s water clowns.1<br />

How you can help<br />

Help protect habitat for species at<br />

giftsofnature.ca.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SUMMER <strong>2022</strong> 13

FORCE FOR<br />

NATURE<br />

Changemaker<br />

Rob Prosper sees the potential to accelerate conservation<br />

through Indigenous-led protected areas<br />

JESSICA DEEKS.<br />

14 SUMMER <strong>2022</strong><br />

natureconservancy.ca

For the first part of his career with Parks<br />

Canada, Rob Prosper lived and worked in<br />

some of Canada’s most iconic natural areas,<br />

such as the Nahanni National Park Reserve. In these<br />

places of stunning landforms and beautiful waterways,<br />

Prosper also saw first-hand the impression made on<br />

visitors by the people who called the land home.<br />

Thaidene Nëné National Park Reserve<br />

THAIDENE NËNÉ NATIONAL PARK RESERVE: PARKS CANADA. JESSICA DEEKS.<br />

“I used to say, ‘we attract people to geography, but people leave with a<br />

cultural experience,’” Prosper explains. “And that’s the one that lasts.”<br />

Prosper recognized that the practices and traditions of Indigenous<br />

communities in natural areas, such as the Dehcho First Nation in<br />

Nahanni, made profound impressions on visitors. He believes that<br />

these types of authentic experiences are important to fostering an<br />

ethic of conservation.<br />

Continuing his career at Parks Canada’s national office, as the director<br />

of Indigenous Affairs and the vice-president of Protected Areas<br />

Establishment and Conservation, Prosper was responsible for building<br />

meaningful relationships with Indigenous people. A member of Acadia<br />

First Nation, Prosper says he has been influenced by these relationships<br />

with Indigenous leaders in conservation.<br />

Prosper recently retired after a 38-year career and now sits on the<br />

board of directors for the Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>).<br />

“It’s an organization that can actually contribute to conservation on<br />

the ground and, as a land manager, it lends itself to building relationships<br />

with Indigenous people,” explains Prosper about his inspiration<br />

to join <strong>NCC</strong>’s board.<br />

[Indigenous Protected and Conserved<br />

Areas] can advance conservation and<br />

also put in the foreground the importance<br />

of Indigenous culture and language.<br />

ADVANCING CONSERVATION AND RECONCILIATION<br />

Prosper was the federal lead on the Pathway to Canada Target 1,<br />

a goal set by the government to conserve 17 per cent of terrestrial<br />

areas and inland water, and 10 per cent of marine and coastal areas<br />

of Canada by 2020. Since then, Canada has set the goal of 30 per<br />

cent of its lands and oceans by 2030.<br />

When considering reaching these new targets, Prosper believes<br />

a wide and inclusive approach is necessary, and sees great potential<br />

in working collaboratively with Indigenous communities.<br />

“The biggest conservation gains available to Canada to meet its<br />

international obligations,” says Prosper, “are in the area of Indigenous<br />

Protected and Conserved Areas, and those can take a whole<br />

variety of forms.”<br />

As defined by the 2018 Indigenous Circle of Experts report,<br />

Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs) “are lands<br />

and waters where Indigenous governments have the primary role in<br />

protecting and conserving ecosystems through Indigenous laws, governance<br />

and knowledge systems. Culture and language are the heart<br />

and soul of an IPCA.”<br />

Prosper believes these areas can advance<br />

conservation and also put in the foreground<br />

the importance of Indigenous culture and<br />

language. “I don’t know that there is a more<br />

profound expression of Reconciliation than<br />

Indigenous communities responsible for their<br />

territories,” says Prosper.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> works in collaboration with<br />

Indigenous communities across the country<br />

on a broad range of conservation projects.<br />

Prosper believes the science-based expertise<br />

of the organization can be helpful with work,<br />

such as identifying biodiversity-rich areas,<br />

while Indigenous knowledge and applying<br />

concepts such as Two-Eyed Seeing contributes<br />

to a holistic approach to managing<br />

lands and waters.<br />

Considering his own connections to nature,<br />

Prosper thinks about his time working on<br />

the land and the relationships he developed.<br />

“Experiencing the Nahanni through the eyes<br />

of the community of Nahanni Butte and<br />

through the eyes of Dehcho First Nation was<br />

very influential,” he reflects.<br />

In his work at Parks Canada, Prosper<br />

ensured Sable Island, Tallurutiup Imanga and<br />

Thaidene Nëné and many other protected<br />

areas were established. He lives with his<br />

family in southeastern Ontario and has a<br />

nearby farm property, which he says allows<br />

him to be connected to the land. Prosper<br />

plants and tills, while still letting things grow<br />

a bit wild to contribute to the area’s biodiversity.<br />

He jokes, “I’m now managing my own conservation<br />

area.”1<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SUMMER <strong>2022</strong> 15

PROJECT<br />

UPDATES<br />

1<br />

Investing in our future<br />

SOUTHWESTERN MANITOBA<br />

3<br />

1<br />

THANK YOU!<br />

Your support has made these<br />

projects possible. Learn more at<br />

natureconservancy.ca/where-we-work.<br />

2<br />

Investing in nature has never been more important. Manitoba’s<br />

prairies, forests, wetlands and lakes not only provide important<br />

habitat for rare and endangered species, they help lessen the risks<br />

of flooding, filter our drinking water, and capture and store carbon.<br />

They also attract pollinators and protect the land against drought.<br />

These natural landscapes, including the mixed-grass prairie and<br />

wetlands found on Manitoba’s Jackson Pipestone Prairies & Wetlands<br />

project, are nature’s gift and our ally in the face of today's global climate<br />

change and biodiversity loss crises. The project is part of two Important<br />

Bird Areas. This is a key opportunity to support prairie, tributary and<br />

lake conservation in the province.<br />

Located in southwestern Manitoba, near the town of Broomhill, the<br />

project includes some of the last large, connected blocks of mixed-grass<br />

prairie in the province. The securement of these lands ensures the<br />

sustainability of important habitats and the thousands of species that<br />

depend on them.<br />

A number of at-risk species live here, including Baird’s sparrow,<br />

Sprague’s pipit, ferruginous hawk, chestnut-collared longspur, prairie<br />

loggerhead shrike, burrowing owl, great plains toad and barn swallow.<br />

Maple Lake and Plum Lake also provide important stopover habitat<br />

for migrating waterbirds.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> partners with local farmers and producers to improve the longterm<br />

health of grasslands. The project is managed with nearby lands as<br />

part of a larger livestock production operation, providing further benefits<br />

to the local economy.<br />

With your support, we can protect this remarkable place for local<br />

and migratory species.<br />

For more information, visit natureconservancy.ca/jacksonpipestone.<br />

GLYN THOMAS/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO. INSET: <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

Giving back<br />

“It’s important to show younger generations<br />

that you need to keep giving back — to get<br />

them in the mindset of helping protect the<br />

environment and preserve natural habitats<br />

in perpetuity.<br />

Burrowing owl<br />

“We see real value in providing a significant<br />

stream of steady funding that can be used<br />

as a catalyst for accelerating the Nature Conservancy<br />

of Canada’s ambitious conservation<br />

goals. Our intention is that our $1-million<br />

donation encourages other individuals or<br />

families to give flexible funding to protect<br />

the environment. We hope this becomes<br />

a prototype for giving that other donors will<br />

be motivated to replicate.<br />

“Change won’t happen overnight, but if,<br />

as a result of our gift, more people know<br />

about <strong>NCC</strong> and take steps to support your<br />

projects and programs, then in 10, 15 or<br />

even 20 years, we’re likely to see even more<br />

land conserved, more wildlife thriving and<br />

more people enjoying nature.”<br />

~ Al Collings and Hilary Stevens,<br />

Collings Stevens Family Foundation,<br />

donors since 2017

Caribou<br />

2<br />

Keep The Rock Rugged<br />

NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>’s Keep The Rock Rugged campaign is an ambitious three-year appeal to raise $3 million to advance<br />

conservation in Newfoundland and Labrador. Over $1 million is already committed.<br />

The province has the third-smallest percentage of protected land in Canada. Keep The Rock Rugged<br />

aims to expand critical nature reserves and support student internships, volunteer programs and<br />

research projects, and invest in new technology to advance nature conservation in the province.<br />

Learn more at natureconservancy.ca/keeptherockrugged.<br />

Newfoundland and Labrador<br />

Partner Spotlight<br />

RBC Tech for Nature is<br />

a multi-year commitment to<br />

new ideas, technologies and<br />

partnerships focused on<br />

protecting our shared future.<br />

That’s why the organization<br />

partnered with the Nature<br />

Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>)<br />

to invest in the power of<br />

innovative technology.<br />

CARIBOU: MIKE DEMBECK. ROCK: CLAUDIA HANEL. WATERTON: LETA PEZDERIC/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF.<br />

Waterton Park Front, AB<br />

3<br />

A legacy of care<br />

WATERTON PARK FRONT AREA, ALBERTA<br />

Across the country, <strong>NCC</strong> works in and near communities and landscapes that have cared for the lands<br />

and waters around them for generations. In spring 2021, the Bectell family approached <strong>NCC</strong> about ensuring<br />

the future of the lands that had been under their care for years.<br />

Working with <strong>NCC</strong>, the family placed a conservation agreement on their lands, located 10 kilometres<br />

east of Waterton Lakes National Park. The property includes native grasslands and wetlands. The<br />

area is home to several species at risk, such as ferruginous hawk, grizzly bear and western blue iris.<br />

It is also within a sensitive raptor and key sharp-tailed grouse range and next to a Key Wildlife and<br />

Biodiversity Zone.<br />

The 324-hectare Bectell property builds on the existing network of lands under <strong>NCC</strong>’s care in the<br />

Waterton Park Front area. The agreement ensures the property will be maintained in a natural, healthy,<br />

unfragmented state while retaining its use as a working ranch.<br />

RBC Tech for Nature has<br />

helped <strong>NCC</strong> to develop artificial<br />

intelligence (AI)-based tools<br />

to plan effective conservation<br />

action across the country. These<br />

tools take existing information<br />

on species, habitat, climate,<br />

connectivity and threats and<br />

predict where the best places<br />

are to conserve and what<br />

conservation actions to take.<br />

The tools are also among the<br />

first in the country to help<br />

prioritize actions to care for<br />

properties once they are<br />

confirmed for conservation.<br />

This partnership highlights<br />

the importance of conserving<br />

the right habitats and places,<br />

while using the right processes,<br />

globally, in <strong>NCC</strong>'s work to<br />

address the twin crises of<br />

biodiversity loss and climate<br />

change. Ultimately, these<br />

AI-based tools support<br />

decision-making to optimize<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>’s impact from coast to<br />

coast to coast.<br />

natureconservancy.ca

CLOSE<br />

ENCOUNTERS<br />

A love letter<br />

to the<br />

mountains<br />

By Gayle Roodman, <strong>NCC</strong> manager of editorial services<br />

Dear mountains,<br />

You don’t know me personally, but you might recognize me by my<br />

feet. I’ve skied, hiked, snowshoed and biked your contours for the<br />

past several decades.<br />

You see, you changed the course of my life.<br />

When I finished high school in Ontario, I was nowhere near<br />

deciding what to do with my life.<br />

The first thing I did after graduating was take the train to Lake<br />

Louise in Alberta to work there for the summer. I will never forget my<br />

reaction to seeing your Rockies for the first time. I was gobsmacked.<br />

Seeing your grey spires and blue-white glaciers in person left me<br />

speechless. Between shifts, I spent most of my spare time exploring<br />

you. I even took a mountaineering course so I could become<br />

closer to you.<br />

In winter, I’d return to Ottawa to work. I did this for a few years,<br />

until your call was too strong to pass up. You got under my skin,<br />

so I moved myself west.<br />

Being new to the area, I joined outdoors groups filled with<br />

like-minded people. I made lifelong friends on your trails. You<br />

also opened a world of possibilities. I’ve explored your Adirondack,<br />

Himalaya, Tatra and Andes cousins. Each mountain range looks<br />

different, but despite the continental divides, you share something<br />

in common: the power to lift my mood, rejuvenate me, challenge<br />

me and deepen my connection to the natural world.<br />

But you haven’t had it easy. You provide so much — clean air,<br />

water, leisure, refuge for species, spiritual benefits, just as a start —<br />

yet I sometimes forget that despite being massive and strong, you’re<br />

still vulnerable to development and the effects of climate change.<br />

For all that you’ve given me, here’s what I promise to give back to<br />

you: you’ll never become “wallpaper” to my eyes. I’ll always marvel at<br />

the light that plays upon your ridgetops. I’ll fiercely defend my belief<br />

that you look prettier with snow, and more formidable without. I’ll continue<br />

to seek you out when I need to clear my head and raise my heart<br />

rate. I’ll respect your temperaments and your weather. I’ll give space<br />

to the animals that live on you. I will always remember that it is a privilege<br />

to experience the awe of your vistas. And I’ll do my best to ensure<br />

others treat you well and with the care and respect you deserve.<br />

Thank you, and keep up the good work.<br />

Gayle<br />

JACQUI OAKLEY.<br />

18 SUMMER <strong>2022</strong> natureconservancy.ca

LET YOUR<br />

PASSION<br />

DEFINE<br />

YOUR<br />

LEGACY<br />

Your passion for Canada’s natural spaces defines your life; now it can define<br />

your legacy. With a gift in your Will to the Nature Conservancy of Canada,<br />

no matter the size, you can help protect our most vulnerable habitats and the<br />

wildlife that live there. For today, for tomorrow and for generations to come.<br />

Order your free Legacy Information Booklet today.<br />

Call Marcella at 1-877-231-3552 x 2276 or visit DefineYourLegacy.ca

YOUR<br />

IMPACT<br />

Swift fox pups, southern Saskatchewan<br />

Protecting<br />

native grasslands<br />

Today, less than 20 per cent of Saskatchewan’s<br />

native grasslands remain intact. But thanks<br />

to your support, 629 hectares of endangered<br />

grasslands and wetlands at the Lonetree Lake<br />

property have been protected. Many private<br />

donors also contributed to the conservation of<br />

Lonetree Lake, including members of the Field of<br />

Dreams Facebook Group, initiated by University<br />

of Regina professor Marc Spooner. What started<br />

with Spooner’s question, “What should we do<br />

with our Saskatchewan Government Insurance<br />

rebates?” expanded into something incredible.<br />

The group raised $103,500 toward protecting<br />

the vibrant habitat found at Lonetree Lake.<br />

Hastings Wildlife Junction, ON<br />

TOP TO BOTTOM: JOHN E. MARRIOTT; MIKE DEMBECK.<br />

Critical conservation<br />

in southern Ontario<br />

The 8,000-hectare Hastings Wildlife Junction will<br />

play a critical role in lessening the impacts of<br />

climate change and biodiversity loss. Located at<br />

the junctions of the Algonquin to Adirondacks<br />

and The Land Between corridors, a project of<br />

this magnitude and ecological significance is<br />

staggeringly rare in southern Ontario, where so<br />

much of the land is converted for development.<br />

Thank you for all you do for nature in Canada!