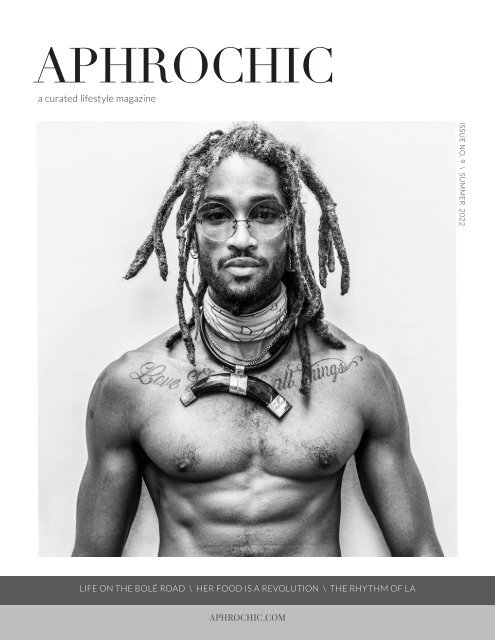

AphroChic Magazine: Issue No. 9

In issue 9, we're featuring some amazing creatives starting with musician, singer, and star of this issue’s cover, Greg Banks. We sit down to talk with him about his start in New Orleans following Katrina, his career, and his upcoming album. Then we’re on to London to tour the chic Chelsea duplex that inspiring textile designer Hana Getachew made all her own while spending a year in England. The new generation of multi-hyphenate storytellers are making their voices heard in this issue, starting with Tiffany-Anne Parkes, better known as the “Pienanny,” whose mouthwatering treats are works of visual art. Meanwhile South African architecture-student-turned-fashion- designer Sindiso Khumalo dedicates her latest collection to the memory of one of Africa’s most important libraries.

In issue 9, we're featuring some amazing creatives starting with musician, singer, and star of this issue’s cover, Greg Banks. We sit down to talk with him about his start in New Orleans following Katrina, his career, and his upcoming album. Then we’re on to London to tour the chic Chelsea duplex that inspiring textile designer Hana Getachew made all her own while spending a year in England. The new generation of multi-hyphenate storytellers are making their voices heard in this issue, starting with Tiffany-Anne Parkes, better known as the “Pienanny,” whose mouthwatering treats are works of visual art. Meanwhile South African architecture-student-turned-fashion- designer Sindiso Khumalo dedicates her latest collection to the memory of one of Africa’s most important libraries.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

APHROCHIC<br />

a curated lifestyle magazine<br />

ISSUE NO. 9 \ SUMMER 2022<br />

LIFE ON THE BOLÉ ROAD \ HER FOOD IS A REVOLUTION \ THE RHYTHM OF LA<br />

APHROCHIC.COM

<strong>AphroChic</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong> is back and ready to take you on another trip around the<br />

world to sample some of the beauty, talent, intellect and creativity that the African<br />

Diaspora has to offer. We’ve been busy while we’ve been gone: putting the finishing<br />

touches on our new book, recording new podcasts, designing new collections, new<br />

products, and more. There’s so much that we can’t wait to share in the coming<br />

weeks. And to top it all off, we celebrated a birthday.<br />

In 2022, <strong>AphroChic</strong> turned 15. For more than a decade we have been living our dream, breaking new ground<br />

along the way. We designed the first African American showhouse on the West Coast at Helms Bakery. Launched<br />

the first Black paint line with Colorhouse. Wrote the first book on African American design in the 2010s and are now<br />

working on our second — the first book to look at the legacy of the Black family home. We had the honor of producing<br />

the first home decor series blending design and social media for HGTV. And we’ve designed and showcased collections<br />

with a Black lens on design in Paris, New York City, and other cities around the globe, leading up to luxury<br />

home decor lines at Perigold and 1st Dibs. All while having fun designing boutiques, interiors, and concept spaces<br />

for African American business owners and creatives along the way.<br />

We don’t often take time to sit back and look at what we’ve done, mostly we only think about what we’re doing<br />

and what we need to do next. But for a Black-owned brand to have lasted 15 years is an accomplishment that warrants<br />

bit of reflection — especially when we consider how hard it for Black businesses to survive in America.<br />

Only 13% of small businesses in the US make it 15 years and very few of those are Black owned. Some 80% of Black<br />

businesses fail in just 18 months due to lack of capital, resources, and other issues often stemming from systemic<br />

racism. We know how rare it is for us to be here, how unlikely it was that we would have made it, and the responsibility<br />

we have to shine a light on others who are doing the same.<br />

In issue 9, that light is shining on some amazing creatives starting with musician, singer, and star of this issue’s<br />

cover, Greg Banks. We sit down to talk with him about his start in New Orleans following Katrina, his career, and<br />

his upcoming album. Then we’re off to London to tour the chic Chelsea duplex that inspiring textile designer Hana<br />

Getachew made all her own while spending a year in England. The new generation of multi-hyphenate storytellers<br />

are making their voices heard in this issue, starting with Tiffany-Anne Parkes, better known as the “Pienanny,”<br />

whose mouthwatering treats are works of visual art. Meanwhile South African architecture-student-turned-fashiondesigner<br />

Sindiso Khumalo dedicates her latest collection to the memory of one of Africa’s most important libraries.<br />

It’s been 15 years since <strong>AphroChic</strong> went live for the first time and we want you to know that we are just getting<br />

started. The work we do continues, in this magazine, our book, our podcast, our products, and so much more. We’re<br />

honored to have you on this journey with us and thankful for every step we take together.<br />

Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Founders, <strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

Instagram: @aphrochic<br />

editors’ letter

in memoriam<br />

A Tribute to Patrick Cline<br />

In the spring, <strong>AphroChic</strong> lost a friend and brother, a creative partner, and one of the earliest<br />

members of the <strong>AphroChic</strong> family. Patrick Cline was one of the first people to believe in <strong>AphroChic</strong>.<br />

When we first met him, it was to make a ridiculous request: we asked him to photograph our first product<br />

line in a two-day, guerrilla-style shoot traversing two states with one model and practically no budget.<br />

He had every reason to say no, but he said yes.<br />

For the next 13 years, we collaborated on everything from magazine articles to pop-up dinners and<br />

our HGTV series, Sneak Peek. He shot our first book, Remix: Decorating with Culture, Objects and Soul, and<br />

our second, <strong>AphroChic</strong>: Celebrating the Legacy of the Black Family Home.<br />

Over those years of collaborating, Patrick did the important work of capturing Black interiors. In<br />

fact, it’s likely that no other interiors photographer has captured as many African American spaces. His<br />

work helped give important exposure to Black interiors. And he was instrumental in taking portfolio<br />

images for many African American designers, helping them get their work seen online and in editorials.<br />

More importantly, he was our friend. When we lived in Philly and he was traveling for work, he let us<br />

spend a summer at his midtown apartment. When we relocated to Brooklyn, he helped us move in. As we<br />

traveled the country together, he introduced us to teas from around the world and we initiated him into<br />

the mysteries of the Philly cheesesteak. We shared a love of Hip-Hop, argued over James Bond movies,<br />

ate more than we should have, and had a lot of fun.<br />

When we knew that we would write a second book, Patrick was our only choice for a photographer.<br />

We knew it would be our biggest project together. We didn’t know it would be our last.<br />

We’ll always miss you, Patrick. We'll always be grateful for the time we had, the things we learned<br />

from you, and everything we created together. Until we see you again — thank you.<br />

Above: Patrick, Jeanine, and Bryan at the AphroFarmhouse in 2021, shooting the home for APHROCHIC.<br />

Left: Bryan, Jeanine, and Patrick taking a lunch break on their trip to Los Angeles in 2012 to shoot for Remix.<br />

6 aphrochic issue nine 7

SUMMER 2022<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

Read This 12<br />

Watch List 14<br />

Coming Up 16<br />

The Black Family Home 18<br />

Mood 26<br />

FEATURES<br />

Fashion // Out of the Ashes 30<br />

Interior Design // Life on the Bolé Road 40<br />

Culture // Gee’s Bend Quilts 60<br />

Food // Her Food Is a Revolution 64<br />

Entertaining // Bringing the Indoors Out 70<br />

City Stories // The Rhythm of LA 76<br />

Reference // Finding Home in Diaspora 84<br />

Sounds // Soul Man 90<br />

PINPOINT<br />

Artists & Artisans 98<br />

Civics 104<br />

Who Are You? 110

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

Cover Photo: Greg Banks<br />

Photographer: Clarence Klingebeil<br />

Publishers/Editors: Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Creative Director: Cheminne Taylor-Smith<br />

Editorial/Product Contact:<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong>.com<br />

magazine@aphrochic.com<br />

Sales Contact:<br />

Ruby Brown<br />

ruby@aphrochic.com<br />

Contributors (left to right below):<br />

Patrick Cline<br />

Chinasa Cooper<br />

issue nine 11

READ THIS<br />

Throughout history, Black voices and the impact of Black culture have been denied, suppressed, and<br />

discounted. Each of our book selections in this issue offers a take on that fact, while looking to a more<br />

inclusive future. The most colorful and delicious of the three, Black Food, examines the African Diaspora<br />

through food, including migration, spirituality, and the future, all told through recipes and moving essays.<br />

The Black Experience in Design also tells its story through essays, allowing 70 Black designers and creatives<br />

to reveal their history, experiences, and aspirations. The Black Experience in Design also serves as both<br />

inspiration and a catalyst for the next generation of creative minds. A Visual Diary by Brooklyn-based<br />

artist Anthony Amiewalan uses pattern, line, and texture (along with occasional playful titles) to tell a<br />

story and to convey a message. Emotion is expressed through colors, each of which represents a feeling or<br />

vibe, allowing Amiewalan to find his voice, and to share it.<br />

A N E W<br />

C L A S S I C<br />

The Black Experience in Design<br />

by Anne H. Berry<br />

Publisher: Allworth. $20<br />

H A S<br />

A R R I V E D<br />

P R E O R D E R N O W<br />

Black Food: Stories , Art, and Recipes from<br />

Across the African Diaspora<br />

by Bryant Terry<br />

Publisher: 4 Color Books. $24<br />

A Visual Diary<br />

by Anthony Amiewalan<br />

Publisher: Blurb<br />

Perennial. $90<br />

12 aphrochic

WATCH LIST<br />

A unique exhibit in New York recreates specific places from the life of iconic '80s artist Jean-Michel<br />

Basquiat. One of the youngest artists to exhibit at the Whitney Biennial in New York, Basquiat was part<br />

of the neo-expressionism movement before his death in 1988 at the age of 27. The Jean-Michel Basquiat:<br />

King Pleasure exhibit includes 200 rare paintings, drawings and artifacts, 177 of which have never been<br />

seen before. King Pleasure, the title of a painting created by Basquiat in 1987, was curated by Basquiat's two<br />

sisters, Lisane Basquiat and Jeanine Heriveaux, who are responsible for their brother's estate and who<br />

included family mementos in the rooms and exhibits. The unusual exhibition space in the Starrett-Lehigh<br />

Building was designed by David Adjaye, the architect for the Smithsonian National Museum of African<br />

American History in Washington, D.C., and the Studio Museum in Harlem. The show brings the artist to<br />

life with these intimate rooms, showcasing an astonishing career and incredible amount of work created<br />

in such a short time. For more information, or to purchase tickets, go to kingpleasure.basquiat.com.<br />

The LGM Revolving Wall Bed & Home Office System<br />

A recreation of Jean-Michel Basquiat's studio<br />

that he rented from Andy Warhol, part of the<br />

Jean-Michel Basquiat: King Pleasure exhibit.<br />

Revolving<br />

Library + Bed<br />

The LGM library with built-in desk<br />

revolves 180° to reveal a queen bed.<br />

Your décor stays in place for an<br />

effortless day-to-night transformation.<br />

14 aphrochic<br />

New York City Los Angeles Calgary Washington, D.C. Seattle Vancouver San Francisco Toronto Mexico City<br />

ResourceFurniture.com

COMING UP<br />

After a long pause, live events are back to celebrate and explore the African Diaspora.<br />

Rolling Loud<br />

July 22-24 | Miami<br />

Touted as the largest Hip-Hop<br />

festival in the world, Rolling Loud is<br />

moving to Miami this summer with<br />

over 100+ acts on three stages.<br />

Headlining Rolling Loud Miami are<br />

major acts including Kendrick Lamar,<br />

Future, Saweetie, and more, who<br />

are set to perform at the Hard Rock<br />

Stadium over three days.<br />

For more information or for a full<br />

schedule, go to rollingloud.com/<br />

miami2022.<br />

20th Anniversary Martha’s Vineyard<br />

African American Film Festival<br />

August 5-13 | Martha's Vineyard, MA<br />

The Martha’s Vineyard African American Film Festival<br />

is an Oscar-qualifying event for the Short Film<br />

Category. The nine-day event showcases the works<br />

of independent and established African American<br />

filmmakers, and includes panel discussions, original<br />

feature films, documentaries, and short films. Learn<br />

more at mvaaf.com.<br />

National Black Theatre Festival<br />

August 1-6 | Winston-Salem, NC<br />

In its 17th year, the festival rolls out the purple carpet<br />

in <strong>No</strong>rth Carolina’s city of arts and innovation with over<br />

130 performances in a number of the city’s venues.<br />

Events include workshops, films, seminars, a poetry<br />

slam, and a gala. This year's co-chairs are Lisa Arrindell<br />

(Madea’s Family Reunion and Livin’ Large) and Petri<br />

Hawkins Byrd (Judge Judy). For more information, a full<br />

schedule of events, or for tickets, go to ncblackrep.org.<br />

16 aphrochic

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

Transformative Spaces: <strong>AphroChic</strong> Worked with Resource<br />

Furniture to Transform an Extra Bedroom into a Room That’s<br />

Part Home Office, Guest Bedroom, and Wellness Space<br />

Design is about looks, we know, but that’s not all. Past all of the color palettes and<br />

furniture trends, at the end of the day a well-designed home is one that meets the<br />

needs of the people who live in it. When we bought the AphroFarmhouse, one of<br />

the first parts of our design project was mapping out how each space in the home<br />

would be utilized. It’s a process we’ve been through many times with our clients,<br />

but somehow it’s always different when the client is you. Either way, it requires an<br />

assessment of how you live and how the home will fit your needs. We knew that<br />

our spaces would need to work overtime. As business owners who have worked<br />

from home for over a decade now, we want every part of our home to be a place<br />

where we can sit and work. At the same time, we want every room to be extremely<br />

comfortable, a place to sit back, relax and watch the sun go down. Essentially, we<br />

wanted each space in our home to help us live our lives fully.<br />

The Black Family Home is an<br />

ongoing series focusing on the<br />

history and future of what home<br />

means for Black families.<br />

Stay tuned for the upcoming book<br />

from Penguin Random House.<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Photos by Patrick Cline and Bryan Mason<br />

18 aphrochic

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

At some point we realized that we<br />

needed three rooms when we only had one:<br />

we needed a bedroom for guests, an office<br />

for meeting, podcasting and general work,<br />

and a room for exercise. We also needed<br />

help. So to turn one room into three, we<br />

turned to Resource Furniture, a luxury<br />

brand specializing in multi-functional<br />

furnishings that we'd worked with years<br />

ago in designing a space for a trade show.<br />

Working with Challie Stillman, VP<br />

of Sales & Design at Resource Furniture<br />

we turned an empty guest room with ’80s<br />

style light blue walls into a space that<br />

offers us everything we need: a desk area<br />

for work, space for our wellness routines,<br />

room for guests, and storage for everything.<br />

In a room that’s barely 150 square<br />

feet, we were able to accomplish everything<br />

on our list.<br />

We sat down with Challie to discuss<br />

the project and why modular furniture has<br />

become ever more important in a world<br />

where people are spending more time at<br />

home than ever before.<br />

APHROCHIC: Design is about solving<br />

problems, and everywhere we look today —<br />

from rampant disease to climate change — we’re<br />

seeing problems in need of answers. Expanding<br />

the role of design beyond the aesthetics of a<br />

room, what role do you feel design can play in<br />

helping to address these and other issues?<br />

RESOURCE FURNITURE: Good design<br />

has always gone beyond mere aesthetics;<br />

for a design to be successful, it must<br />

be purpose driven. It must seek to solve<br />

common problems in an intuitive and<br />

elegant way, while also taking into its<br />

account long-term impact. This has always<br />

been the single most important function of<br />

design, but the events of the past two-anda-half<br />

years have finally brought this fact<br />

into stark relief for many people.<br />

People are now acutely aware of just<br />

how impactful design can be on our physical<br />

and mental health. Being confined to a space<br />

with little to no natural light, poor indoor<br />

air quality, poor organization, confusing<br />

configurations, and limited space to work<br />

or play can all take an extreme toll on our<br />

mental health and overall wellness. In fact,<br />

this phenomenon even has a name: the psychology<br />

of space.<br />

Good residential interior design<br />

seeks to address these problems and<br />

create spaces that foster health, wellness,<br />

productivity, and creativity. It addresses<br />

issues like — does this space have ample<br />

access to natural light and ventilation? Are<br />

there designated zones for working and<br />

relaxation? Are furnishings, paints, and<br />

fabrics treated with harmful materials?<br />

The Resource Furniture collection<br />

seeks to offer creative solutions that<br />

address these and other common issues<br />

in the home. When spaces are designed<br />

with the physical and psychological needs<br />

of the occupants in mind, it completely<br />

changes our thoughts and behaviors in<br />

that context.<br />

AC: Modular furniture, in the form<br />

of Murphy beds and extendable tables,<br />

have been around for some time. How did<br />

modular furniture become the focus for<br />

Resource and what unique elements do you<br />

bring to the industry?<br />

RF: During the Great Recession<br />

brought on by the financial crisis of 2008,<br />

many people were unable to upgrade to<br />

larger homes and needed to make more<br />

out of the space they already had. At the<br />

time, wall beds and other transforming<br />

furnishings were somewhat unknown to<br />

American consumers, but Resource introduced<br />

a new solution that allowed<br />

people to not only live comfortably in<br />

The space before<br />

20 aphrochic issue nine 21

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

their existing spaces, but actually thrive<br />

in them. Resource’s first foray into multifunctional<br />

design was a two-bedroom<br />

apartment in the Urban Glass House for a<br />

single mother and her four children, with<br />

comfortable sleeping and study arrangements<br />

for all, plus a living room that transformed<br />

into a guest bedroom.<br />

Resource is the leader in transforming<br />

and multifunctional furniture. We<br />

design flexible spaces that maximize a<br />

home’s functionality and solve common<br />

needs: the ability to work from home, grow<br />

a family, entertain, and host overnight<br />

guests. We collaborate with Italian manufacturers<br />

to craft our curated collection<br />

of innovative, space-saving furniture with<br />

a focus on wall beds, transforming tables,<br />

modular seating, and storage solutions.<br />

AC: Since 2020, with all of its health<br />

and economic upheaval, we started seeing<br />

an uptick in homes where multiple generations<br />

are housed under one roof, sometimes<br />

leaving very little extra space. How can<br />

modular furniture address these issues?<br />

RF: Multigenerational housing had<br />

actually been on the rise since the 1950s, and<br />

in 2020 it was given a huge burst of acceleration<br />

by the pandemic. In 2017, Resource<br />

participated in Making Room: Housing for a<br />

Changing America, an exhibit at the National<br />

Building Museum in Washington, D.C.,<br />

which played a major role in shifting the<br />

public perception of transforming furniture<br />

and multi-functional spaces, with a key<br />

focus on generational housing needs.<br />

With the help of Pierluigi Colombo<br />

of Clei, Resource Furniture designed<br />

a 1,000-square-foot home within<br />

the museum, fitted with a variety of<br />

multi-functional wall beds and transforming<br />

tables. During the exhibition, the<br />

concept home was transformed multiple<br />

times to show how the same floor plan<br />

could support a variety of different households<br />

— a group of single adult roommates,<br />

a multi-generational family, or a couple<br />

of empty nesters with an attached ADU<br />

(Accessory Dwelling Unit) — using just<br />

furniture, not changing the interior architecture.<br />

With each room serving multiple<br />

functions as the furniture expands and<br />

contracts, the home feels twice if not three<br />

times its actual size.<br />

AC: Another outcome of the pandemic<br />

has been the number of people forgoing<br />

gym memberships in favor of working out at<br />

home. The Resource pieces that we have in<br />

our own wellness room allow it to double as<br />

a guest bedroom and triple as a home office.<br />

Are you seeing more of these instances<br />

allowing multiple uses in a single room?<br />

RF: We have certainly seen a rise in<br />

people looking into wall beds to create<br />

home offices and home gyms without sacrificing<br />

any real estate in their homes.<br />

With many people hosting guests only a<br />

few times a year, it simply does not make<br />

sense to have a vacant room the majority<br />

of the time.Transforming your physical<br />

space allows you to make the mental shift<br />

required to be equally productive, active,<br />

or restful in a way that wouldn’t be possible<br />

with furniture to accommodate all those<br />

functions at once. Transforming furniture<br />

allows us to create established “zones” that<br />

cultivate and encourage a healthy work environment.<br />

AC: Why was it important for Resource<br />

Furniture to be a part of the AphroFarmhouse<br />

makeoever project?<br />

RF: We first collaborated with Bryan<br />

and Jeanine back in 2016 on a Micro<br />

Loft they designed for BKLYN Designs<br />

showcasing how one could live, sleep,<br />

and entertain in a small footprint with<br />

maximum style. Their talent for infusing<br />

a home with warmth, culture, and sense<br />

of wellbeing brought life to what could<br />

have otherwise been just another trade<br />

show. When the opportunity arose to<br />

collaborate on the AphroFarmhouse,<br />

we were thrilled to reconnect and participate.<br />

Our furniture offers the<br />

multi-functionality needed to carve out<br />

a wellness room in what would otherwise<br />

be just a guest room or office, making it<br />

the perfect solution in the AphroFarmhouse.<br />

AC: Life since 2020 has pushed us all<br />

to rethink the nature of design, home and<br />

comfort. We’ve seen the importance of<br />

home and now we see it’s importance in how<br />

difficult the housing market has become.<br />

For us, it’s come to the point where we can<br />

no longer see these things as class distinctions,<br />

but as human rights. Have your ideas<br />

on home changed over the last two years?<br />

RF: Homeownership has never<br />

been equitable, and this disparity has<br />

become more apparent than ever. One<br />

of our missions as a company is to push<br />

for more diverse and accessible housing<br />

stock to help bridge the homeownership<br />

gap —whether that means providing<br />

transforming furnishings for supportive<br />

housing of formerly homeless NYC<br />

seniors through our partnership with<br />

Riseboro, furnishing units set aside for<br />

homeless Veterans in Carmel Place (NY’s<br />

first micro-unit building), or supporting<br />

legislation to pave a clear and accessible<br />

path for homeowners to build<br />

ADUs in California. Over the last two<br />

A rendering of<br />

the wall bed and<br />

shelving.<br />

22 aphrochic issue nine 23

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

years, this mission has become more<br />

essential to us than ever. And while by<br />

no means a solution to larger systemic<br />

problems at play, transforming furniture<br />

(and flexible design in general) does<br />

offer viable solutions to common<br />

space problems created by the housing<br />

disparity, making smaller spaces<br />

function optimally. We see our furniture<br />

as a means to enrich people’s experiences<br />

in their homes and think creatively<br />

about their use of space by eschewing the<br />

given floorplan. If we can facilitate one’s<br />

ability to host overnight guests comfortably,<br />

to throw dinner parties for family<br />

and friends without a designated dining<br />

room, to carve out a productive nook in<br />

which to work from home, or exercise<br />

and maintain a healthy lifestyle without<br />

a designated home gym, we’ve made a<br />

difference.<br />

We are proud to support the work and<br />

mission of <strong>AphroChic</strong> and can’t wait for<br />

the next project! AC<br />

To see <strong>AphroChic</strong>’s library featuring<br />

custom shelving by Resource Furniture,<br />

pre-order a copy of <strong>AphroChic</strong>: Celebrating<br />

the Legacy of the Black Family Home.<br />

The multipurpose room at the AphroFarmhouse, showcasing the wall bed from Resource Furniture,<br />

closed on opposite page for the wellness room, and open above to create a guest space.<br />

24 aphrochic issue nine 25

MOOD<br />

BLACK & WHITE<br />

Black and white is timeless. This classic color<br />

palette will never go out of style. And today, classic<br />

black-and-white designs for the home feel fresh<br />

and renewed in stunning silhouettes. Our favorite<br />

pieces in black and white embrace bold curves and<br />

new lines that showcase each piece as a work of art.<br />

Raffia Wall<br />

Hangings<br />

from $425<br />

elanbyrd.com<br />

Goddess Candle<br />

from $10<br />

shadesofblackness.com<br />

Bootyful Black Bum Vase<br />

$85<br />

latzio.com<br />

Cities speckled<br />

clay bowl $80<br />

studiobppco.com<br />

Nasara Chair $251.68<br />

theurbanative.com<br />

Keshia Black<br />

Currant +<br />

Rose Candle<br />

$44<br />

gavinluxe.com<br />

Yoomelingah-yure<br />

Art Basket<br />

$749<br />

babatree.com<br />

Acacia Vessel 2<br />

from $550<br />

nurceramics.com<br />

Cococozy<br />

Square Link<br />

Serving Board<br />

$195<br />

etuhome.com<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong> Ndop<br />

Black and Yellow<br />

Pillow $156<br />

perigold.com<br />

26 aphrochic issue nine 27

FEATURES<br />

Out of the Ashes | Life on the Bolé Road | Gee’s Bend Quilts | Her Food<br />

Is a Revolution | Bringing the Indoors Out | The Rhythm of LA | Finding<br />

Home in Diaspora | Soul Man

Fashion<br />

Out of the Ashes<br />

Sindiso Khumalo’s Collection Found Its<br />

Inspiration in a Devastating Fire<br />

Storytelling is an important part of African culture. All<br />

throughout the continent, there are griots — repositories<br />

of oral traditions who keep history and culture alive<br />

through poems, music, songs, tales, and clothes. For<br />

fashion designer Sindiso Khumalo, her newest collection is<br />

a moment of storytelling worthy of the tradition. The South<br />

African designer’s SS22 collection, JAGGER, was created<br />

to preserve the history and legacy of one of Africa’s most<br />

important libraries — the University of Cape Town Jagger<br />

African Studies Library, which was lost to a mountain<br />

fire in April 2021. The blaze consumed great archives of<br />

African literature, maps, political posters, and countless<br />

historical treasures, but the story of the library lives on.<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays<br />

Photos by JD Barnes<br />

30 aphrochic

Fashion<br />

In her collection, Sindiso honors<br />

those treasures lost to the fire and those<br />

who worked in the library to preserve<br />

African scholarship. Two-piece suits in the<br />

collection are dedicated to the librarians<br />

who built the institution’s archives. Political<br />

illustrations by Sinalo Ngcaba are a reference<br />

to the political posters, novels, maps, and<br />

book covers that the fire took. Hand-embroidered<br />

elements and handmade ceramic<br />

buttons evoke the wildflowers that sprung<br />

up on the mountain in the place where the<br />

building once stood.<br />

A London-based architecture-studentturned-fashion-designer,<br />

Sindiso draws<br />

heavily on her Zulu and Ndebele heritage<br />

in her designs, playing out what she terms<br />

a “love affair” with her heritage in physical<br />

form. Far from being an homage only to what<br />

was lost, the collection is also a lesson on how<br />

to preserve and sustain. JAGGER features<br />

sustainable materials, including recycled<br />

cotton and organic cotton blends across the<br />

collection.<br />

The job of a griot is not simply to recount<br />

the past, but to keep alive the lessons and<br />

legacies of history for present generations to<br />

build on. Born out of ashes, JAGGER tells a<br />

story of the past. But Sindiso’s narrative is for<br />

us to hear right now. Bright colors, modern<br />

silhouettes, and sustainable materials,<br />

all tell the story with the aim of inspiring<br />

us towards a bright new future. In this<br />

collection, past and present come together,<br />

reminding us that all is not lost as long as we<br />

follow in those old griot traditions, working<br />

through design with artistry to keep our<br />

history alive. AC<br />

32 aphrochic

Fashion<br />

34 aphrochic

Fashion<br />

36 aphrochic

Fashion<br />

38 aphrochic issue nine 39

Interior Design<br />

Life on<br />

the Bolé<br />

Road

Interior Design<br />

At Home with Hana Getachew<br />

For Hana Getachew, the Bolé Road is a lot of things. It’s the<br />

name of her celebrated textile line, a gorgeous collection of<br />

traditionally-inspired Ethiopian pillows and accessories,<br />

currently enjoying a collaboration with West Elm. It’s a popular<br />

thoroughfare in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, where the designer was<br />

born. Most of all it’s a metaphor for all of the important journeys<br />

she’s been on in life, starting with the first one.<br />

“I took two very important journeys on Bolé Road,” Hana reflects.<br />

“The first is where I left Ethiopia as a child, because the road<br />

leads to Bolé International Airport. And then the second was<br />

when I returned for the first time, 18 years later.” <strong>No</strong>w she’s<br />

on the road again, taking a yearlong hiatus from home in her<br />

beloved Brooklyn to enjoy the sights, sounds, and experiences<br />

of London.<br />

Words by Bryan Mason<br />

Photos by Oliver Gordon<br />

issue nine 43

Interior Design

Interior Design<br />

Interior Design

Interior Design<br />

Traveling with her husband, screenwriter Brian Tucker<br />

and their daughter, Gelila, Hana has stepped out of her comfort<br />

zone and into a whole new world — one she seems to like. “The<br />

second I arrived I was so enchanted with London,” she says. At<br />

the center of her enchantment is her family’s adopted home,<br />

a three-bedroom, two-story, Mews-style house in London’s<br />

famed Chelsea neighborhood.<br />

From the entryway, the home opens up into an intriguing<br />

living area made up of two separate rooms. Located directly<br />

across from each other, each has its own distinct design plan<br />

and color scheme. “One is warm and intense, and the other<br />

is all cool, muted tones,” Hana explains. “It was kind of a<br />

weird design challenge.” It was also indicative of how one of<br />

the home’s major selling points could also be one of its few<br />

drawbacks, especially for a designer.<br />

“This place came fully furnished,” she shrugs, “which<br />

makes sense because who would want to furnish a home for<br />

just a year’s stay?” Still, living in a home built around someone<br />

else’s aesthetic took some getting used to. “I almost vetoed<br />

this apartment because of the oxblood sectional in the family<br />

room,” she laughs. “It's just not my vibe.”<br />

The vibe that Hana left in Brooklyn is a highly curated mix<br />

of modern design, Ethiopian culture and family heirlooms. “Incorporating<br />

my culture and my heritage has always been a part<br />

of the spaces I've lived in.” Coming to London meant leaving<br />

some of her favorite things behind. “One of the most important<br />

pieces to me,” she lists, “is this kind of lopsided, off kilter, hide<br />

skin table from my parents' home. I also have beautiful rugs that<br />

I found in Morocco. And I have a gallery wall of baskets. I incorporate<br />

a basket wall in every apartment that I live in.” Once<br />

Brian convinced her that a disagreeable sofa shouldn’t come<br />

between them and the perfect place, Hana got to work bringing<br />

in just enough design to make London feel like home.<br />

Of course the sofa was her first target. She made the<br />

leather feel more cozy adding cushions from her own collection.<br />

The results were inspiring. “I was wondering if our pillows<br />

could even work in the space since there was already a lot going<br />

on color-wise, but it did! I even used our bed runner as a throw!”<br />

Following her success in the first living room, Hana took a more<br />

restrained approach to the second. “I kept the cool side of the<br />

living room more muted with some of our neutral pillows,” she<br />

remembers. After that, the rest was editing. “We rearranged the<br />

seating a bit so it flowed better, moving the armchairs in near<br />

the green settee which is actually a futon.” Hana’s effortlessly<br />

energetic aesthetic and facility with making the right moves in<br />

a space make it hard to believe that she didn’t always know that<br />

this was the field she was destined for.<br />

“I'm not one of those people that knew what they wanted<br />

to be when they were young,” Hana admits. Then she reconsiders.<br />

“Actually I did, I wanted to be an artist. I wanted to be a fine<br />

artist.” Following that path, she attended Cornell University as<br />

a fine arts major. Like any good student she had questions, and<br />

soon began to suspect that she wasn’t asking them in the right<br />

place. “I found that I really wasn't getting answers to the kinds<br />

of questions that I had.” So when a friend majoring in interior<br />

design invited Hana to take a class, it was an epiphany. “My mind<br />

was blown. They had classes like ‘Making a difference through<br />

design,’ all these things that I was interested in, and wanted to<br />

explore but wasn't quite getting in the fine arts program. So I<br />

made the transition and the rest is history.”<br />

48 aphrochic

Interior Design<br />

Making history meant first getting a job at an interior<br />

design firm before making the transition into textiles and<br />

a brand of her own. “As an interior designer, I love textiles<br />

and picking finishes and furniture,” Hana confesses. “So for<br />

me, developing a textile line felt like a natural transition.”<br />

The other major influence leading to the start of her line was<br />

Hana’s second big trip on the Bolé Road — her first trip back to<br />

Ethiopia. “That first trip back was really a pivotal moment in my<br />

life,” she reminisces. “Being immersed in my culture, and my<br />

country once again. I think that's when I first started thinking<br />

about wanting to be more involved.”<br />

Down the stairs from the living rooms, another open space<br />

is home to the kitchen, dining room and an atrium leading to<br />

a beautiful outdoor seating area. Like the upstairs, Hana recognized<br />

a hot/cool dichotomy in the design plan, this time<br />

spread across the kitchen and dining room. “The kitchen’s<br />

cool cabinets, subtle blue tint and marble backsplash and shelf<br />

completely offsets the intense warmth of the dining area,” she<br />

says. Though in her heart it’s the bright colors of the dining<br />

room she really loves. “These amazing orange chairs just sing to<br />

me.” Together, the two spaces are the most popular part of the<br />

house, where the family spends most of its time. It’s proven to<br />

be ideal for spending time together. “Our New York home really<br />

made it easy to eat in front of the TV,” Hana says. “But here, with<br />

the living room upstairs, we just cook and eat, do work and<br />

homework downstairs. And there’s a playroom just down the<br />

hall.”<br />

While the kitchen and dining room may see the most use,<br />

other rooms vie for position as Hana’s favorite. One of the frontrunners<br />

is her office. Originally designed as a nursery, complete<br />

with whimsical toucan-patterned wallpaper, it soon became<br />

an ideal space for Hana to take time to keep track of the many<br />

sides of her brand; sides that include collaborating with teams<br />

of weavers in Ethiopia who help to bring Hana’s products to<br />

life while giving her the opportunity to connect and give back.<br />

“A big part of why I started this company, is to not only be more<br />

connected to Ethiopia, but also to contribute in supporting<br />

the development of the economy,” she says. “The people of the<br />

South are really known for their weaving skills. They are the<br />

main contributors to weaving production in the country but<br />

each region has a very distinct aesthetic in their clothing and in<br />

their textiles. I love having the opportunity to share that.”<br />

Hana’s textiles make another bold appearance in her<br />

London home in the cozy and chic outdoor space, accessible<br />

through her office. Just as in the rest of the home, pillows,<br />

throw blankets and even a rug add dimensions of color and<br />

culture to this intimate seating area, complementing the lush,<br />

green plants that hang from the walls. Embracing it as one of the<br />

areas where she could do the most design work, Hana played<br />

with furniture layouts as well as color palettes to create three<br />

separate seating areas. “It just makes it so cozy and inviting,” she<br />

smiles.<br />

Even with all of its other amenities, Hana admits that<br />

it was the bedrooms this home had to offer that made it her<br />

choice — especially the one for her daughter Gelila. The pretty,<br />

pink interior features several built-in sleeping spaces as well<br />

as a whimsical hanging light pendant and pompom-styled wall<br />

art. In her own bedroom, Hana’s textiles infuse similar pops<br />

of pink to energize the largely neutral color palette. There, the<br />

main attraction for Hana isn’t the room itself, but the room<br />

it’s attached to. “The master bath is one of my top three rooms<br />

here,” she grins. With an impressive list of features including<br />

a stand-alone tub, heated floors and towel rack and walnut<br />

cabinets along with a cool sounding name — “They call [master<br />

bathrooms] ‘ensuites’ here,” she says — the bathroom is one of<br />

the things Hana says she’ll find hardest to leave behind when<br />

their time in London is through. “I don't know if I'll ever have any<br />

of these again,” she frets.<br />

When she was three years old, the Bolé Road took Hana<br />

Getachew away from Ethiopia. Eighteen years later it took her<br />

back. Since then it’s taken her in and through all aspects of the<br />

interior design industry and into her own brand, to new ways of<br />

connecting with her heritage and sharing it with the world. <strong>No</strong>w,<br />

as her time in London draws to a close, Hana is ready to set out<br />

on the road again to see where it takes her next, knowing that<br />

wherever it leads, the road will always bring her home. AC<br />

To explore Hana’s latest collection of pillows and textiles visit West<br />

Elm.<br />

52 aphrochic

Interior Design<br />

54 aphrochic

Interior Design

Culture<br />

Gee’s<br />

Bend<br />

African American Works<br />

of Early Modern Art<br />

Quilts<br />

One of the potential hazards of loving art is the<br />

tendency to see it as something separate from everyday<br />

life — a thing apart, with no ability to function practically<br />

beyond what it stirs in us emotionally or intellectually.<br />

Sometimes that can be true, but often<br />

our most inspired works are the ones inspired by a<br />

practical need, like the patterned rugs of the Middle<br />

East and Central Asia. Similarly, the African American<br />

quilts of Gee’s Bend, hailed as pivotal works of modern<br />

art in museum exhibitions around the country, were<br />

inspired by the simple need to stay warm.<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Photographs of Quilted by Katie Mae provided by Etsy<br />

60 aphrochic issue nine 61

Culture<br />

The small community of Gee’s Bend, located at an isolated bend<br />

in the Alabama River, about 50 miles south of Selma, began in 1816 as<br />

the cotton plantation of Joseph Gee. The plantation was later sold,<br />

along with its workforce of 47 enslaved laborers to a relative, Mark H.<br />

Pettway. Though the land would change hands repeatedly afterward,<br />

most of the current community’s inhabitants — the descendants of<br />

those enslaved on the original plantation, still bear the Pettway name.<br />

The tradition of quilt making that developed in Gee’s Bend<br />

likely traces back to the earliest days of the plantation itself, drawing<br />

from a combination of African, Native American and original techniques.<br />

The quilts first came to national attention in the 1960s with<br />

the formation of the Freedom Quilting Bee. This collection of Gee’s<br />

Bend women gathered after auctions of the quilts in New York City<br />

attracted the attention of Vogue, Bloomingdales and eventually the<br />

Smithsonian. The collective was a way for women in the community to<br />

earn money and rally support for the voting drives of the Civil Rights<br />

Movement. In retaliation, the local government ceased ferry service to<br />

the community, effectively isolating it, save for a single country road.<br />

Undeterred, the collective continued to gain friends and connections<br />

and is credited with causing a resurgence of popularity for quilts in<br />

American interior design in the 1960s.<br />

By the time the 21st century arrived, the Gee’s Bend quilts were<br />

firmly established as works of art. The first exhibition, The Quilts<br />

of Gee's Bend, was held at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston in 2002<br />

before traveling across the country. In 2006, ferry service to the<br />

community was restored.<br />

Gee’s Bend quilts come in a variety of styles, each of them<br />

a departure from the more structured traditions of Europe and<br />

European Americans. These styles can be generally categorized as<br />

abstract/improvisation; geometric; bricklayer; Sears corduroy; and<br />

workclothes. The abstract or improvised quilts are often considered<br />

the most emblematic of the tradition. Easily the most emotional of the<br />

styles, their aesthetic has often been compared to that of jazz improvisation<br />

for the free-form and energetic perspective they express.<br />

The geometric quilts are dazzling works of art repeating<br />

simple shapes like triangles or rectangles in creative and unexpected<br />

patterns. This style was very popular among Gee’s Bend quilters in<br />

the early 20th century. Their bright, energetic displays are a striking<br />

contrast to what the community was experiencing through the Great<br />

Depression years.<br />

Bricklayer quilts begin with a single piece of fabric, with strips<br />

of additional cloth woven in from the edges to frame the original<br />

pattern in the center. A longtime favorite within the community, the<br />

technique has been compared to the “Call and Response” tradition of<br />

African American music, as found in gospel and the Blues.<br />

The corduroy and workclothes techniques speak to the very roots<br />

of the tradition. In the '70s, the Freedom Quilting Bee produced pillow<br />

cases for Sears. Scraps of the material provided inevitably found<br />

their way into their quilts. The works produced during this period<br />

are unique both for their color palette and being made of corduroy,<br />

considered an atypical fabric for quilting. Worn workclothes on the<br />

other hand, were the first and most enduring resource for Gee’s Bend<br />

quilters. The fabric, already beaten and worn from hard use in the<br />

fields, lent a hauntingly weathered feel to the quilts when strips of<br />

the material were laid out in abstract patterns — or in some cases, no<br />

pattern at all.<br />

Gee’s Bend quilts can be displayed in the home in any number of<br />

ways. As works of art they can be hung on the walls or even framed to<br />

create a dramatic backdrop. But it’s just as fitting to put them to their<br />

original uses. They were made to keep families together and warm,<br />

and there’s no more practical or artistic reason to bring something<br />

into your home than that. However you choose to incorporate a Gee’s<br />

Bend quilt into your home decor, it’s important to do so in a way that<br />

recognizes the fraught history and long tradition that they emerge<br />

from and continue to represent, respecting them not just as folk art<br />

“from the margins,” but as modern art from the heart. AC<br />

Authentic Gee’s Bend Quilts can now be discovered online. Here are<br />

some of our favorite resources for authentic quilts:<br />

Quilted by Katie Mae on Etsy<br />

Katie Mae specializes in traditional Gee’s Bend quilting.<br />

She is a verified Gee’s Bend Maker on Etsy. Her handstitched<br />

quilts come in a variety of abstract patterns.<br />

Mary Lee Bendolph on Artsy<br />

Mary Lee Bendolph is one of the best known Gee’s Bend<br />

Quilters. Her works include salvaged materials that<br />

have been re-imagined into complex abstract patterns.<br />

Her expressive works for sale or on auction can be discovered<br />

on Artsy.<br />

62 aphrochic issue nine 63

Food<br />

Her Food Is<br />

a Revolution<br />

Tiffany-Anne Parkes of Pienanny Forces Us<br />

To Reckon With History One Pie At A Time<br />

“You have a social responsibility as an artist,” says Tiffany-Anne<br />

Parkes, the founder of Pienanny. It’s a responsibility that<br />

she does not take lightly. Speaking with the culinary artist<br />

over Zoom, it’s clear that Parkes is always thinking deeply<br />

and intentionally about the work she’s doing, even while<br />

on vacation. Enjoying the Jamaican sun while visiting with<br />

family, her hair pulled back in beach-ready blonde cornrows,<br />

she’s equal parts reflective and instructive, talking about<br />

pies as if she was still teaching history in front of a classroom<br />

— a full-time profession that she recently left this year. “Why<br />

aren’t we taking it a step further,” she asks [after a pause],<br />

“and thinking about how we can use culinary artistry to say<br />

something meaningful?”<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Photographs by Theodore Samuels and courtesy of Pienanny<br />

64 aphrochic

Food<br />

Part of the answer may be<br />

that, for most of us, “culinary<br />

artistry” isn’t something we’ve<br />

ever conceived of — at least not<br />

the way that Parkes does. While<br />

there are a number of worldclass<br />

chefs leading conversations<br />

on how food connects to<br />

deeper questions of class, equity,<br />

and social justice, there are few<br />

visual artists using food as their<br />

medium. For Parkes, the connection<br />

is clear, resulting in a<br />

unique blend of food and art that<br />

blurs the line between fine artist<br />

and chef to the point of near irrelevance.<br />

The artist/chef uses<br />

her hands to mold dough into<br />

enticing pies that hold urgent<br />

historic narratives, presenting<br />

her audience with social commentary<br />

we can eat. A combination<br />

made even more remarkable<br />

by the fact that as an artist and a<br />

chef, she’s entirely self-taught.<br />

“I don't have any ‘chefs’<br />

in my family,” Parkes explains.<br />

“Most of what I learned about<br />

cooking I learned in the kitchen,<br />

just watching my mother or<br />

watching my aunts, and cousins.<br />

I would say it was a really organic<br />

process.” Her path as a visual<br />

artist has been equally organic,<br />

and like cooking, she’s been at it<br />

for as long as she can remember.<br />

“I started drawing at the age of<br />

five. And so visual art has always<br />

been an outlet for me,” she<br />

recalls. Proud of her Jamaican<br />

heritage, Parkes prefers flavors<br />

and fillings traditional to the<br />

island. But for those of us not<br />

fortunate enough to have tasted<br />

her work, there’s joy to be found<br />

in what we see.<br />

On her Instagram, which<br />

is as much a gallery space as a<br />

menu and visual diary, there’s<br />

the deeply hued pie in dark<br />

raspberry that was inspired<br />

by Elizabeth Catlett’s There<br />

Is a Woman In Every Color, a<br />

feminine face etched beautifully<br />

into the dark purple crust. Other<br />

works depict an image of Queen<br />

Nanny, leader of an 18th century<br />

community of Jamaican Maroons<br />

on a tart drizzled with caramel<br />

sauce and a gingersnap crust<br />

that’s home to a hibiscus custard<br />

shaped into the silhouette of<br />

Saartjie Baartman, the Khoikhoi<br />

South African woman who was<br />

illegally enslaved and displayed<br />

across Europe and whose body<br />

was later deconstructed for<br />

study. Looking much like a piece<br />

at a Kara Walker exhibit, and<br />

with similar impact, serving up<br />

important histories and uncomfortable<br />

truths, the Baartman<br />

piece puts viewers in exactly the<br />

type of double-bind that characterizes<br />

so much of Pienanny’s<br />

work: While some of us may<br />

look away from the history, no<br />

one’s going to turn away from the<br />

pie. And like any good teacher,<br />

Parkes uses that allure to get our<br />

attention and keep it until the<br />

lesson is done.<br />

“I was really going to be an<br />

English teacher,” says Parkes,<br />

who eventually went on to develop<br />

curricula for the District of Columbia’s<br />

Public Schools before<br />

teaching history at a grade<br />

school in Harlem. <strong>No</strong>w her love of<br />

teaching, literature, and history<br />

has been brought together in<br />

her pies, a process that Parkes<br />

professes, started due to the<br />

pandemic and the growing civil<br />

rights movement that spread<br />

around the globe in 2020.<br />

“Once the George Floyd murder<br />

happened,” she remembers,<br />

“maybe like three months into<br />

lockdown, and Black Lives Matter<br />

started happening, it provided<br />

an outlet for me.” With her new<br />

project and pen name, Pienanny,<br />

Parkes began building a following<br />

on Instagram, baking, creating,<br />

sharing her process, all while<br />

sharing historical narratives that<br />

invite her followers to go a little<br />

deeper and learn a bit more. And<br />

whether her work is ultimately<br />

seen as food or art, for Parkes,<br />

what’s really important is the<br />

narrative, not just for learning,<br />

but for healing. “I like to call it art<br />

therapy because when I was a kid,<br />

I would always withdraw when<br />

I would do anything artistic. I<br />

would do these things because<br />

they've always made me feel<br />

better. It was my outlet. So now<br />

I find myself going back to the<br />

practices that I was really into as<br />

a child.”<br />

Parkes is now working on<br />

launching her new project, A<br />

Seat Above The Table. Her new<br />

non-profit will host what she<br />

describes as a highly curated<br />

multimedia, multidisciplinary<br />

dining experience. “As Black<br />

women, Black people, we're<br />

always talking to each other<br />

about issues, we're always<br />

talking to each other about all<br />

kinds of things. But we're never<br />

having these conversations<br />

with the people that we need to<br />

have these conversations with<br />

because they're too uncomfortable.<br />

But we have to start. That<br />

has to happen if you really want<br />

there to be some sort of progress<br />

or change.” Whether through<br />

art or outreach, the Pienanny is<br />

a woman with a story to tell —<br />

a story that’s for us, by us, and<br />

that we all need to hear if we’re<br />

to reach the happy ending at it’s<br />

conclusion. “It's meant to be culturally<br />

inclusive and exclusive,”<br />

she smiles. “It's like a joke. If you<br />

get it, you get it. If you don't, then<br />

that's telling too.” AC<br />

issue nine 67

Food<br />

This tart design was initially inspired<br />

by the title of Nicole A. Taylor’s recently<br />

released cookbook Watermelon and Red<br />

Birds: A Cookbook for Juneteenth and<br />

Black Celebrations. The imagery is not<br />

meant to evoke nostalgia or fondness;<br />

rather it is a call to acknowledge history<br />

as always working in our present social<br />

construct. The black bird is representative<br />

of loss and death as well as our everlasting<br />

connection to and guidance from<br />

ancestral planes. I also play with the ideas<br />

of reclamation, ownership, and hope.<br />

My personal belief is that art at its best<br />

is a discourse that involves provocation<br />

and inquiry. With this piece, my aim<br />

is to provoke the viewer to read about<br />

the economic and political positioning<br />

of watermelon during America’s<br />

Reconstruction period. And should any<br />

viewer find themselves enamored by the<br />

imagery, my hope is that they say it out<br />

loud with their chest and someone asks<br />

them, “Why?” — Tiffany-Anne Parkes<br />

Reconstructed Watermelon Lemon Tart<br />

INGREDIENTS<br />

Crust<br />

16 oz Saltine Crackers<br />

2 tsp Sea Salt<br />

¾ cup (1 ½ stick) softened Unsalted Butter<br />

Watermelon Lemon Curd<br />

1 cup Fresh Meyer Lemon Juice<br />

½ cup Fresh Watermelon Juice<br />

21 oz (1 ½ can) Condensed Milk<br />

1 tbsp activated charcoal powder<br />

6 Jumbo Eggs<br />

Garnish<br />

Basil Leaf<br />

Blackberries<br />

Dehydrated Watermelon Pulp<br />

Preheat the oven to 365 degrees.<br />

Throw the crackers, butter, and salt into a food processor and blend well. ***If you do not have<br />

a food processor this can be done using a blender or manually with a mortar and pestle. In this<br />

case, be sure to combine the ground crackers and salt before adding the butter.<br />

Scoop three cups of the mixture into a 10-inch pie or tart pan. Using the bottom of a measuring<br />

cup, press the mixture into the pan until you have a full ¼- inch thick crust. Place the shell in the<br />

oven and bake it for 12-15 mins. or until the crust is a very light golden brown.<br />

While the crust is par baking, whisk the lemon juice, watermelon juice, condensed milk, charcoal<br />

powder, and eggs in a bowl until just fully blended. Do not over beat.<br />

Remove the crust from the oven, fill with the custard mixture, and place back in the oven for<br />

15-20 minutes or until the filling is set. Once baked, allow the tart to cool to room temperature,<br />

and then place it in the fridge overnight. ***For a velvety smooth filling, use a hot water bath and<br />

bake at 355 degrees for 45 minutes.<br />

68 aphrochic issue nine 69

Entertaining<br />

Bringing The<br />

Indoors Out<br />

An Outdoor Oasis Perfect for Entertaining<br />

It’s that time of year. Time for summer barbecues, family reunions, fish<br />

fries, and getting together with family and friends to enjoy the great<br />

outdoors. During this season of entertaining, it’s also a great time to<br />

bring the indoors outside, creating comfortable spaces to sit, relax, and<br />

entertain for the next few months.<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Interior Design by <strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

Photographers: Seth Caplan and Chinasa Cooper<br />

issue nine 71

Entertaining

Entertaining<br />

But outdoor spaces aren’t just about the grill and a patio table.<br />

They can be living spaces specially crafted to provide the ultimate in<br />

comfort with a look that reflects your personal style. In this project<br />

we thought of every detail to create the perfect outdoor dining space<br />

where our client can entertain all year long (even in the winter months<br />

with a tent overhead).<br />

This plain backyard in the Bronx was transformed by our team<br />

into a stunning oasis. The design started with creating a graphic base<br />

for the outdoor space. Just like shopping for flooring and rugs for your<br />

interior, we were in need of a striking floor to replace what used to<br />

be a dirt surface. A statement-setting concrete floor made of hexagon<br />

tiles immediately adds a modern touch.<br />

To define the space and make those tiles pop, walls were built to<br />

create a restful and relaxing retreat away from the noise of the city.<br />

Hand painted black, the walls are the start of a cool and classic blackand-white<br />

color palette. Black outdoor pillows and cushions are highlighted<br />

by black-and-white bolsters on custom seating.<br />

In addition to modular seating and stools, a dining area was also<br />

carved out in this cozy outdoor space. Woven seating brings a modern<br />

feel to the high-bar dining table and chairs. And outdoor art on the brick<br />

wall defines the dining area and adds some indoor style to the space.<br />

While the main color palette is in black and white, color is added with<br />

lots and lots of plants. The lush plants bring in a wash of green and pink,<br />

adding life and color to this space. Just like the concrete floor and furnishings,<br />

the pots are weather-resistant giving them longevity year-round.<br />

The result is an outdoor oasis that looks and feels like an<br />

extended living room and it’s the perfect place to host outdoor dinner<br />

parties with friends and family. AC

City Stories<br />

The Rhythm of LA<br />

Interior Designer Ron Woodson Takes Us on a Tour<br />

of His Family’s History in the City of Angels<br />

Ron Woodson’s family has had a creative impact in Los Angeles<br />

for three generations, contributing to the sights and sounds that<br />

made the City of Angels what it is today. Music was the driving<br />

force that set the tone for his family’s LA experience, starting<br />

with his grandfather, Frank Woodson Sr. In a childhood that could<br />

be a movie script, Ron Woodson grew up around jazz greats and<br />

Hollywood legends, and can even claim the iconic Bobby Short as<br />

his godfather.<br />

Words by Cheminne Taylor-Smith<br />

Images Provided by Ron Woodson<br />

issue nine 77

City Stories<br />

“Growing up in LA for me was fantastic,” he says. “I didn’t have<br />

a typical childhood. I went to a lot of gigs and rehearsals with my dad<br />

and got to experience a grand lifestyle that most kids, let alone a young<br />

black kid, never got to experience. I was always mature beyond my<br />

years, and I was a very well-mannered and extremely exposed child,<br />

wearing blue blazers, slacks, and black-and-white saddle shoes.”<br />

His family’s Los Angeles life started with his grandfather, who<br />

owned a large part of the property in South LA that later became the<br />

King/Drew Medical Center. The land included a small farm with<br />

chickens, cows, goats, homing pigeons, dogs, and geese. But Frank<br />

Woodson was also a musician who played bass, and later went on to<br />

be the founder of the Watts Symphony Orchestra. “He was very civic<br />

minded,” Ron Woodson says. “He exposed young inner-city kids to<br />

music. In his later years he was honored by then-Mayor Tom Bradley,<br />

who was a family friend.”<br />

Ron’s father Buddy Woodson was almost predestined to have<br />

a musical career and he followed in his father’s footsteps by playing<br />

upright bass. But Buddy’s musical focus was the growing jazz scene of<br />

his time, and he performed in the most famous jazz clubs of the ’40s,<br />

’50s, and ’60s in LA. In fact, Ron’s father met his mother in one of those<br />

clubs. “They met in South LA at the Club Alabam,” Ron says. “They met<br />

while my dad was performing there.”<br />

Club Alabam was on Central Avenue in a predominantly Black<br />

area of Los Angeles, and was one of the premier destinations — along<br />

with the Dunbar Hotel — for jazz in the city. Both venues drew huge<br />

crowds, including white jazz fans from the west side of the city. “Both<br />

clubs had a rich history of jazz and bebop,” according to Ron. “The<br />

clubs were the mecca of ‘cool’ on Central Avenue.”<br />

Buddy Woodson’s career took off as a bass player, and he also<br />

worked as a studio musician, performing on albums with Sammy Davis<br />

Frank Woodson Sr., Buddy Woodson, and Ron Woodson.<br />

Frank Woodson Sr.<br />

Buddy Woodson with his 1956 Cadillac in Los Angeles.<br />

Buddy Woodson playing upright bass with Sammy Davis Jr.<br />

Buddy Woodson<br />

78 aphrochic issue nine 79

City Stories<br />

Jr., Ella Fitzgerald, Nancy Wilson, Sarah Vaughn, Dinah Washington,<br />

Bobby Short, Gerald Wilson, Sonny Criss, Buddy Colette, and Barney<br />

Kessel. He worked in theater orchestras, movies, and television, and<br />

he played across the U.S. and in Europe. He also performed in west LA<br />

clubs like the one at the Beverly Hills Hotel, at a time when it wasn’t<br />

common for Black patrons to be allowed into those venues.<br />

“My father never talked about issues he had being a Black man in a<br />

white world of entertainment," Ron says. "I’m sure it wasn’t always easy<br />

for him, but he still made huge strides in the ’40s, ’50s, ’60s and ’70s. I<br />

don’t know if he wanted to shield me from that or not.”<br />

Ron said his mother Elgar Woodson was also a strong woman.<br />

“She wasn’t a pushover with anyone or any uncomfortable issues,”<br />

he reveals. “She spoke her mind and stood up for what she knew<br />

was right and she instilled those values in me. My father and my<br />

mother made sure I had a real understanding of what it meant and<br />

how to navigate being a young Black man in America, lessons I live<br />

by to this day. Those lessons have helped me to become the man<br />

that I am.”<br />

Ron’s childhood settings of iconic clubs, movie sets, and grand LA<br />

homes definitely had an impact on his future … after a detour. “I was<br />

in corporate life before becoming an interior designer,” he laughs. “I<br />

always had a creative side that I didn’t really hone in on until my late<br />

20s. As a kid, my mother and I would redecorate our house often and<br />

my bedroom was never the same for six months. My parents sent me<br />

to art school at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. I honed my art<br />

skills from there, but never thought I would be in the creative world as<br />

a career.”<br />

Fast forward and Ron has a thriving design business with his<br />

partner Jaime Rummerfield. Woodson & Rummerfield’s was named one<br />

of the Top 20 Interior Designers by The Hollywood Reporter and Interior<br />

Designers of the Year by the National ARTS Council. The duo has worked<br />

on incredible LA structures by iconic Black architect Paul R. Williams as<br />

well as Greystone Mansion and others by Richard Neutra, Donald Wexler<br />

and Gordon Gaufman. They also enjoy a full portfolio of celebrity clients.<br />

“Being a native Angeleno really informs my design style from the<br />

grandeur of old Hollywood, movie sets, and the backdrop of LA style,”<br />

Ron says. “Also, being fortunate enough to visit grand homes from a<br />

very early age informed my design sense.”<br />

Committed to preserving LA’s architectural heritage, Ron worked<br />

with Rummerfield to found Save Iconic Architecture in 2016. The goal<br />

of the organization is to help prevent major architectural structures<br />

from being torn down. “To date our proudest rescue is the Standard<br />

Hotel on Sunset Boulevard, a true landmark on the famed Sunset<br />

Strip,” he says.<br />

For Ron, the LA lifestyle is still very much where his heart is. “I<br />

love the indoor and outdoor living, architecture, the beach, and wide<br />

variety of cultures. I miss the days when people dressed up to go<br />

places in Los Angeles, but it’s still a mecca for art, design, fashion, and<br />

culinary cuisine. People are attracted to LA because you can reinvent<br />

yourself into anything and anybody you want to be.”<br />

Although many of the clubs and venues from his father’s day<br />

are no longer there, even Ron’s “meet cute” with his husband Tom<br />

took place in a Silver Lake bar. “We met there 33 years ago,” he says.<br />

“We were friends for several years and we became a couple, and this<br />

year we will have been together 28 years.” Proving that even a native<br />

Angeleno can get the perfect Hollywood happy ending. AC<br />

Follow Ron Woodson on Instagram at @rwwoodson or on the Woodson<br />

& Rummerfield's account at @woodson_rummerfields.<br />

Ron Woodson, age 7, above.<br />

Ron with Lionel Hampton, below, and Ron's sister Julie Boutte.<br />

Ron Woodson's Must-See<br />

Sights in LA<br />

1. Musso & Frank Grill<br />

2. Santa Monica and Venice<br />

beaches<br />

3. Griffith Observatory<br />

4. Museums: The Broad, The<br />

Hammer, MOCA, LACMA (in<br />

the process of being re-modeled),<br />

the Motion Picture<br />

museum, and the <strong>No</strong>rton Simon<br />

in Pasadena<br />

5. A play at the Hollywood<br />

Pantages Theatre, where my<br />

father played in the past<br />

6. A drive up the coast on PCH<br />

(Pacific Coast Hwy)<br />

Ron Woodson's mother Elgar Woodson with<br />

Duke Ellington, above, and the extended<br />

Woodson family, right.<br />

80 aphrochic issue nine 81

City Stories<br />

Afro modern decor that creates a sense of connection.<br />

Jamie Rummerfield and Ron Woodson, principals at Woodson & Rummerfield's interior design firm, and founders<br />

of Save Iconic Architecture.<br />

SIA (Save Iconic Architecture) is<br />

a nonprofit that brings education,<br />

awareness and landmarking to iconic<br />

structures in Los Angeles. The group<br />

welcomes the public’s support to continue<br />

the work to save the city’s architectural<br />

history. For more information, go<br />

to siaprojects.org<br />

82 aphrochic<br />

www.reflektiondesign.com<br />

@reflektiondesign

Reference<br />

Finding Home<br />

in Diaspora<br />

Where is home? Is it where you were born, where you grew<br />

up, where you feel most comfortable, or is it wherever<br />

you are right now? Is it where your ancestors are from or<br />

where they went? Is home something fixed in time, or can<br />

it change, in the span of a single lifetime or over a course<br />

of generations? Though we rarely talk about it from this<br />

perspective, the question of home has always been central<br />

to the concept of diasporas. It takes on special significance,<br />

as so many things do, within the African Diaspora, where<br />

everything is meaningful and nothing is simple.<br />

Words by Bryan Mason<br />

Images by zbruch<br />

84 aphrochic

Reference<br />

Starting from Home<br />

In positing one of the earliest frameworks<br />

for defining and studying the African Diaspora,<br />

scholar Joseph Harris laid out several important<br />

characteristics. Describing the African Diaspora<br />

as a “triadic relationship” involving Africa, its<br />

descendants, and the lands to which they were<br />

dispersed, Harris further stipulates that the<br />

cohesion of our diaspora depends upon, “collective<br />

memories and myths about Africa as<br />

the homeland or place of origin; a tradition of<br />

a physical and psychological return; a common<br />

socioeconomic condition; a transnational<br />

network; and a sustained resistance to Africans’<br />

presence abroad and an affirmation of their<br />

human rights.” Taken together, these characteristics<br />

describe the Diaspora as a “dynamic,<br />

continuous, and complex phenomenon stretching<br />

across time, geography, class, and gender.”<br />

Subsequent to Harris’ early framings,<br />

numerous scholars have taken up the challenge<br />

of describing the characteristics through which<br />

diasporas can be more clearly defined. Historian<br />

Kim Butler’s work on the subject is representative<br />

of a large portion of current diaspora<br />

models. In 2019, her work was cited by scholar<br />

Chukwuemeka Nwosu as a “useful schema for<br />

diaspora study which is divided into five dimensions:<br />

(1) reasons for and conditions [of] the<br />

dispersal; (2) relationship with the homeland; (3)<br />

relationship with hostlands; (4) interrelationships<br />

within diaspora groups.” All of which are<br />

taken an the basis for the fifth concern: “comparative<br />

studies of different diasporas.”<br />

In creating her model, Butler drew on<br />

the work of political scientist William Safran in<br />

which diaspora is defined by five characteristics:<br />

1) dispersal to two or more locations, 2) collective<br />

mythology of the homeland, 3) alienation from<br />

hostland, 4) idealization of return to homeland,<br />

and 5) ongoing relationship to homeland. In<br />

particular, Butler carves three specific features<br />

out of Safran’s list as being those which most<br />

diaspora scholars will mention. First, is that<br />

the dispersal must carry the displaced to two or<br />

more locations. Second, is the shared relationship<br />

to a homeland whether real or imagined.<br />

Third, is the awareness of a shared group<br />

identity. To this, Butler adds the stipulation that<br />

the outcome of the dispersal must last for two<br />

generations or more.<br />

While a single, definitive list of features<br />

that characterize all diasporas has yet to<br />