You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Digitized by <strong>the</strong> Internet Archive<br />

in 2019 with funding from<br />

Kahle/Austin Foundation<br />

https://archive.org/details/wewerenotsavages0000paul_t1q7

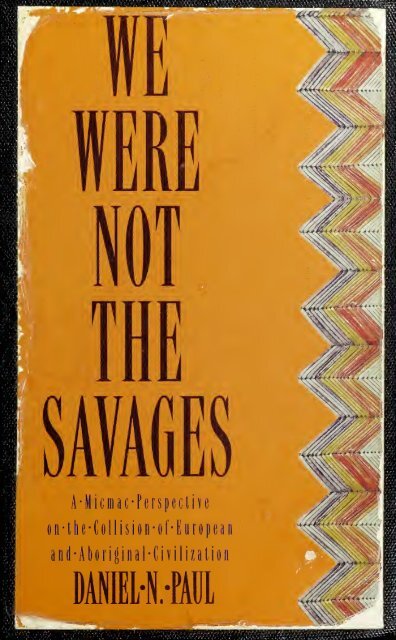

<strong>We</strong> <strong>We</strong>re <strong>Not</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Savages</strong><br />

A Micinac Perspective<br />

on <strong>the</strong> Collision of European and<br />

Aboriginal Civilizations<br />

Daniel N. Paul<br />

Research assistants:<br />

Donald M. Julien and Timothy J. Bernard<br />

Illustrations: Vernon Gloade<br />

Nimbus m<br />

PUBLISHING LTD

Copyright © Daniel N. Paul, 1993<br />

94 95 96 97 98 6 5 4 3 2<br />

/\11 rights reserved. No part of this book covered by <strong>the</strong> copyrights hereon may be<br />

reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical—<br />

without <strong>the</strong> prior written permission of <strong>the</strong> publisher. Any request for photocopying,<br />

recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems of any part of this book<br />

shall be directed in writing to <strong>the</strong> Canadian Reprography Collective, 379 Adelaide Street<br />

<strong>We</strong>st, Suite Ml, Toronto, M5V 1S5.<br />

Nimbus Publishing Limited<br />

P.O. Box 9301, Station A<br />

Halifax, NS B3K 5N5<br />

(902)455-4286<br />

Design: Kathy Kaulbach, Halifax<br />

Copy Editor: Douglas Beall<br />

Cover: Close-up of aMicmac Quillwork box, from Micmac Qitillwork, published by <strong>the</strong><br />

NS Museum. Photo by Bob Brooks, courtesy of <strong>the</strong> Nova Scotia Museum, Halifax.<br />

Nimbus acknowledges <strong>the</strong> support of <strong>the</strong> Department of Communications, Canada<br />

Council, and <strong>the</strong> Nova Scotia Department of Education.<br />

Printed & bound by Best Gagne Book Manufacturers Ltd.<br />

Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data<br />

Paul, Daniel N.<br />

<strong>We</strong> were not <strong>the</strong> savages<br />

Includes bibliographical references and index.<br />

ISBN 1-55109-056-2<br />

1. Micmac Indians—Government relations. 2. Indians of North America—Maritime<br />

Provinces—Government relations. 3. Micmac Indians—First contact with Europeans.<br />

I. Title.<br />

E99.M6P38 1993 971.5'004973 C93-098666-0

Contents<br />

List of Illustrations<br />

Foreword<br />

Chapter I Civilization, Democracy, and Government CD<br />

Chapter II Micmac Social Values and Economy 13<br />

Chapter III European Settlement and Micmac Decline - 38<br />

Chapter IV Persecution, War, and Alliance 53<br />

Chapter V Treaties, Proclamations, and Terrorism 68<br />

Chapter VI The Treaty of 1725 76<br />

Chapter VII Flawed Peace and <strong>the</strong> Treaty of 1749 86<br />

Chapter VIII More Bounties for Human Scalps and <strong>the</strong> Treaty of 1752 107<br />

Chapter IX The Vain Search for a Just Peace, 1752-1761 120<br />

Chapter X Oppression and Despair 148<br />

Chapter XI The Royal Proclamation of 1763 159<br />

Chapter XII The Imposition of Poverty 163<br />

[JChapter XIII Dispossessed and Landless 173<br />

^Chaptei/XIV The Edge of Extinction 182<br />

Chaptef XV Confederation and <strong>the</strong> Indian Act 206<br />

Chapter XVI The Twentieth Century and <strong>the</strong> Failure of Centralization 264<br />

Chapter XVII The Struggle for Freedom 299<br />

<strong>Not</strong>es 341<br />

Select Bibliography 348<br />

Index 354

List of Illustrations<br />

To welcome a stranger 3<br />

The land of <strong>the</strong> Micmac 6<br />

Mo<strong>the</strong>r Earth provides 15<br />

Preparing tomorrow’s provider 17<br />

The storyteller 29<br />

An ocean unsafe 40<br />

The boy and <strong>the</strong> beast 52<br />

The salmon harvest 57<br />

The death of an innocent 74<br />

A journey for hope 84<br />

The slaughter of innocents 103<br />

The bounty hunters 110<br />

The treaty signing (1752) 118<br />

The boarding 125<br />

The transport of Casteel 127<br />

Micmac land offer for peace 140<br />

Starvation and death 164<br />

Begging for alms 174<br />

A nation dying 188<br />

No wood for <strong>the</strong> Micmac 193<br />

Four stories up and terrified 270<br />

Forced feeding of waste 271<br />

Eking out a living 301

Dedication<br />

To <strong>the</strong> memory of my ancestors, who managed to ensure <strong>the</strong> survival of <strong>the</strong><br />

Micmac people by <strong>the</strong>ir awe-inspiring valour in <strong>the</strong> face of insurmountable<br />

odds! The Micmac of today are <strong>the</strong> children of a truly dignified, noble,<br />

courageous, and heroic people. For more than four centuries <strong>the</strong>se people<br />

displayed a determination to survive <strong>the</strong> various hells on Earth created for <strong>the</strong>m<br />

by Europeans with a tenacity that is unrivalled in <strong>the</strong> history of mankind. I, and<br />

all Micmac, take immense pride in <strong>the</strong>ir virtues! May <strong>the</strong>ir bravery inspire us to<br />

meet <strong>the</strong> challenges we face today.

Acknowledgements<br />

I want to thank my wife Patricia, and my daughters Cerena and Lenore, who put<br />

up with me during <strong>the</strong> sixteen months it took to write this book. During that<br />

period all my spare time every day went into writing this history. If our dog<br />

Barney could talk, he would complain about all <strong>the</strong> walks he had to forgo!<br />

I also want to thank Donald M. Julien. Without his support and assistance,<br />

this book would have taken twice as long to complete. Don’s knowledge and <strong>the</strong><br />

research material he has collected over <strong>the</strong> years were invaluable to me in<br />

crafting this history.<br />

Tim Bernard, although not yet as seasoned as Don in <strong>the</strong> field of Micmac<br />

studies, provided much help in locating research material when I needed it.<br />

I want to thank Vernon Gloade for providing <strong>the</strong> drawings for this book,<br />

which aptly describe situations <strong>the</strong> Micmac have faced in <strong>the</strong>ir struggle for<br />

survival.<br />

Douglas Beall went <strong>the</strong> extra mile in helping me to prepare this manuscript<br />

for publication. His expertise and dedication helped me to put <strong>the</strong> finishing<br />

touches on this tribute to <strong>the</strong> Micmac.<br />

Finally, I would like to thank all those who provided <strong>the</strong>ir support and<br />

encouragement!

Foreword<br />

Writing this book was one of <strong>the</strong> hardest things I have ever done. I suffered<br />

excruciating mental anguish while researching <strong>the</strong> continual torment of my<br />

people.<br />

There can be no real peace in Canada until <strong>the</strong> nation assumes responsibility<br />

for its past crimes against humanity and makes amends to <strong>the</strong> Micmac and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

Canadian Tribes for <strong>the</strong> indescribable horrors it subjected <strong>the</strong>m to. The physical<br />

and psychological torment <strong>the</strong> Micmac suffered started shortly after significant<br />

European intrusions began in approximately 1598 and has continued to a certain<br />

degree right up to <strong>the</strong> present time.<br />

Prior to 1492, North American Aboriginals had had innumerable encounters<br />

with Whites who had come mainly from what is today called Scandinavia.<br />

Apparently, <strong>the</strong>se Whites were well received, and early reports indicate that<br />

blue-eyed and light-skinned Aboriginals were not uncommon. In fact, some of<br />

<strong>the</strong> French and English wondered whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> Micmac were not possibly a<br />

White race, because some Micmac were able to dress up in French or English<br />

uniforms and mingle with <strong>the</strong>ir soldiers while ga<strong>the</strong>ring information for tribal<br />

war councils.<br />

The term pre-European contact will not be used in this history. In its place<br />

<strong>the</strong> term pre-colonization will be found, because in my opinion no one can say<br />

with certainty when <strong>the</strong> first contact took place.<br />

Any qualms <strong>the</strong> Europeans may have had regarding <strong>the</strong>ir racist attitudes<br />

toward <strong>the</strong> Micmac were soon obscured by <strong>the</strong>ir drive to satisfy one of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

societies’ worst traits: greed. The plundering of <strong>the</strong> Americas for gold and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

riches soon became <strong>the</strong>ir top priority. To justify <strong>the</strong> horrors that would soon<br />

commence, <strong>the</strong>y conveniently branded <strong>the</strong> Micmac “coloured and hea<strong>the</strong>n<br />

savages,” so no conscience need be disturbed when <strong>the</strong> slaughter of <strong>the</strong> Tribe<br />

and <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ft of its property began.<br />

The atrocities recounted in this book have not been placed here to engender<br />

pity. They have been retold to persuade people of <strong>the</strong> dominant society to use<br />

whatever power <strong>the</strong>y have to see that Canada makes meaningful amends for <strong>the</strong><br />

horrifying wrongs of <strong>the</strong> past.

The Micmac were, arid are, a great people. To be a descendent of this noble<br />

race, who displayed an indomitable will to survive in spite of <strong>the</strong> incredible odds<br />

against <strong>the</strong>m, fills me with pride. I am in awe whenever I think of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

tremendous courage in overcoming <strong>the</strong> daunting obstacles placed in <strong>the</strong>ir path!<br />

Daniel N. Paul<br />

◄ viii<br />

WE WERE NOT THE SAVAGES

I<br />

CIVILIZATION,<br />

DEMOCRACY,<br />

AND<br />

GOVERNMENT<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

Basil H. Johnston’s short story ‘The Prophecy”<br />

begins with <strong>the</strong> fictional storyteller Daebaudjimoot<br />

saying: “Tonight I’m going to tell<br />

you a very different kind of story. It’s not<br />

really a story because it has not yet taken<br />

place; but it will take place just as <strong>the</strong> events<br />

in <strong>the</strong> past have occurred.... And even though<br />

what I’m about to tell you has not yet come to<br />

pass, it is as true as if it has already happened,<br />

because <strong>the</strong> Auttissookaunuk told me in a<br />

dream.”<br />

Daebaudjimoot tells of a strange people<br />

who are white and hairy and wear strange<br />

clo<strong>the</strong>s <strong>the</strong>y practically never take off. He<br />

says <strong>the</strong>y have round eyes that are black,<br />

brown, blue, or green, and fine hair that is<br />

black, brown, blond, and red.<br />

He tells of how <strong>the</strong>y will arrive from <strong>the</strong><br />

East in canoes that are five times <strong>the</strong> length of<br />

regular canoes. These big canoes will have<br />

sailed using blankets to catch <strong>the</strong> wind and<br />

propel <strong>the</strong>m from a land across a great body of<br />

salt water. These ideas are greeted by his<br />

audience with laughter and disbelief. He<br />

continues:<br />

“You laugh because you cannot picture<br />

men and women with white skins or hair<br />

upon <strong>the</strong>ir faces; and you think it funny<br />

that a canoe would be moved by <strong>the</strong> wind<br />

across great open seas. But it won’t be<br />

funny to our grandchildren and <strong>the</strong>ir great¬<br />

grandchildren.”<br />

“In <strong>the</strong> beginning <strong>the</strong> first few to arrive<br />

will appear to be weak by virtue of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

numbers, and <strong>the</strong>y will look as if <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

no more than harmless passers-by on <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

way to visit ano<strong>the</strong>r people in ano<strong>the</strong>r land,<br />

who need a little rest and direction before<br />

resuming <strong>the</strong>ir journey. But in reality <strong>the</strong>y<br />

will be spies for those in quest for lands.<br />

After <strong>the</strong>m will come countless o<strong>the</strong>rs like<br />

flocks of geese in <strong>the</strong>ir migratory flights.

Flock after flock <strong>the</strong>y will arrive. There will be no turning <strong>the</strong>m back.”<br />

“Some of our grandchildren will stand up to <strong>the</strong>se strangers, but when <strong>the</strong>y<br />

do, it will have been too late and <strong>the</strong>ir bows and arrows, war-clubs and<br />

medicines will be as nothing against <strong>the</strong> weapons of <strong>the</strong>se white people,<br />

whose warriors will be armed with sticks that burst like thunderclaps. A<br />

warrior has to do no more than point a fire stick at ano<strong>the</strong>r warrior and that<br />

man will fall dead <strong>the</strong> instant <strong>the</strong> bolt strikes him.”<br />

“It is with weapons such as <strong>the</strong>se that <strong>the</strong> white people will drive our<br />

people from <strong>the</strong>ir homes and hunting grounds to desolate territories where<br />

game can scarce find food for <strong>the</strong>ir own needs and where corn can bare take<br />

root. The white people will take possession of all <strong>the</strong> rest, and <strong>the</strong>y will build<br />

immense villages upon <strong>the</strong>m. Over <strong>the</strong> years <strong>the</strong> white people will prosper,<br />

and though <strong>the</strong> Anishinaubaeg may forsake <strong>the</strong>ir own traditions to adopt <strong>the</strong><br />

ways of <strong>the</strong> white people, it will do <strong>the</strong>m little good. It will not be until our<br />

grandchildren and <strong>the</strong>ir grandchildren return to <strong>the</strong> ways of <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors<br />

that <strong>the</strong>y will regain strength of spirit and heart.”<br />

“There! I have told you my dream in its entirety. I have nothing more to<br />

say.”<br />

“Daebaudjimoot! Are <strong>the</strong>se white people manitous or are <strong>the</strong>y Beings<br />

like us?”<br />

“I don’t know.”1<br />

What <strong>the</strong> future actually held in store for <strong>the</strong> Micmac makes this fictional<br />

prophecy seem mild. Over <strong>the</strong> course of <strong>the</strong> next five hundred years, <strong>the</strong> Micmac<br />

would suffer every kind of indignity humans can inflict upon one ano<strong>the</strong>r. Yet,<br />

in spite of <strong>the</strong> brutal persecution that soon became part of <strong>the</strong>ir daily lives, <strong>the</strong>y<br />

were somehow able to persevere and survive!<br />

4 Micmac and Prior to European settlement, <strong>the</strong> Micmac lived in countries<br />

4 European whose culture was based upon two principles: people power<br />

4 Civilizations and respect for “Mo<strong>the</strong>r Earth.” A harmonious relationship<br />

with nature was considered to be essential for survival.<br />

Micmac societies were well structured, and democratic principles were an<br />

established component. For instance, leaders were appointed by <strong>the</strong> people and<br />

served at <strong>the</strong>ir pleasure. The citizens of <strong>the</strong> Micmac “Nation” enjoyed <strong>the</strong><br />

benefits of living in a relatively peaceful, healthy, and harmonious social<br />

environment.<br />

Disagreements among <strong>the</strong> Micmac were settled in a civilized manner.<br />

Disputing parties were brought toge<strong>the</strong>r for mediation and reconciliation, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> leaders of <strong>the</strong> country or community would encourage and assist <strong>the</strong><br />

antagonists to reach an agreement. Justice and fairness were prime considerations,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> final agreement would address all <strong>the</strong> major concerns of <strong>the</strong> individuals,<br />

groups, or governments involved. When <strong>the</strong> contending parties accepted an<br />

◄ 2 CIVILIZATION, DEMOCRACY, AND GOVERNMENT

agreement, it was with <strong>the</strong> understanding that <strong>the</strong>y were <strong>the</strong>reafter required to<br />

live by its provisions, and this understanding was supported by <strong>the</strong> will of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

fellow citizens.<br />

In contrast, up until recent times, European civilizations, with some notable<br />

exceptions such as <strong>the</strong> Swiss, were governed by a titled elite who declared<br />

<strong>the</strong>mselves to be <strong>the</strong> ruling class and allowed no interference with what <strong>the</strong>y<br />

considered to be <strong>the</strong>ir divine right to rule. Average citizens within <strong>the</strong>se<br />

autocratically governed domains were routinely denied basic rights and freedoms.<br />

They were treated as property and in most cases were held in human bondage<br />

from cradle to grave. When disputes arose within <strong>the</strong>se despotic societies,<br />

settlements were devised and imposed by <strong>the</strong> ruling class, with little consideration<br />

being given to democratic principles.<br />

Reviewing <strong>the</strong> history of this period, it is difficult to conclude which<br />

European nation was <strong>the</strong> most arrogant in insisting upon a blind acceptance of<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir cultural conventions and doctrines, which often showed little regard for<br />

human and civil rights. It seems <strong>the</strong> European powers were, in general,<br />

intolerant and disrespectful of <strong>the</strong> ways of non-European civilizations. Making<br />

an honest attempt to rate <strong>the</strong> major powers of <strong>the</strong> day according to <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

extremely presumptuous picture of <strong>the</strong>mselves as superior human beings, <strong>the</strong><br />

nod goes to <strong>the</strong> British, followed closely by <strong>the</strong> Spanish and Portuguese, with<br />

<strong>the</strong> French a distant fourth.<br />

Freedom, or <strong>the</strong> right of <strong>the</strong> individual to make as many personal choices as<br />

possible, was a fully recognized component of American Aboriginal civilizations.<br />

The wide recognition and acceptance of individual rights by <strong>the</strong>se civilizations<br />

was far in advance of similar developments in Europe. This feature, and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

aspects of Aboriginal society which distinguished <strong>the</strong>m from European societies,<br />

To welcome a stranger.<br />

WE WERE NOT THE SAVAGES 3 ►

were probably <strong>the</strong> reasons why early contacts, well before <strong>the</strong> so-called<br />

discovery of <strong>the</strong> continents by Columbus, promoted stories in Europe about a<br />

strange people inhabiting a far-off land.<br />

These early contacts produced all kinds of imaginative stories about <strong>the</strong><br />

American native people. In <strong>the</strong>m, <strong>the</strong> people who inhabited this land were even<br />

depicted as non-humans, hairy monsters, or subhumans. <strong>Not</strong> much consideration<br />

was given to <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong>se people were intelligent and civilized human<br />

beings.<br />

During this period, <strong>the</strong> European intelligentsia equated civilization with<br />

European conventions; Christianity was its cornerstone. According to this<br />

perception, if a land was not Christian it was not civilized. This attitude led <strong>the</strong><br />

Europeans to attempt to Christianize <strong>the</strong> Middle East and Asia. Their failures in<br />

<strong>the</strong>se regards were monumental, primarily because <strong>the</strong>se regions had <strong>the</strong>ir own<br />

religions, which in some cases predated Christianity by thousands of years. Yet<br />

many of <strong>the</strong>se civilizations also had something in common with <strong>the</strong> Europeans:<br />

<strong>the</strong>y, too, could unleash unspeakable horrors upon friend and foe alike.<br />

The absence of biases among <strong>the</strong> majority of <strong>the</strong> Aboriginal peoples towards<br />

those of a different race, creed, or colour is one of <strong>the</strong> best indicators of how far<br />

advanced <strong>the</strong> human relations of <strong>the</strong>ir civilization were. A stage where people<br />

of every race, creed, and colour are accepted as equals is an ideal that modern<br />

society is still working towards. Most Aboriginal civilizations had already<br />

reached that stage by <strong>the</strong> time of European colonization.<br />

If, in 1492, <strong>the</strong> Aboriginal peoples had possessed <strong>the</strong> same racial, religious,<br />

political, and colour prejudices as <strong>the</strong> Europeans, colonization would never<br />

have occurred. Instead, <strong>the</strong> Europeans, with <strong>the</strong>ir white faces and strange<br />

religions, would not have been permitted to establish a foothold in <strong>the</strong> Americas<br />

as bro<strong>the</strong>rs and sisters but would have been repulsed immediately.<br />

The political and territorial relationships of Micmac civilization were well<br />

developed, defined, and regulated. Probably after much trial and error, <strong>the</strong>y had<br />

developed a society that was functional, colourful, and meaningful, and balanced<br />

its tenets of personal freedom with responsibility to <strong>the</strong> state—a fact totally<br />

ignored by <strong>the</strong> Europeans in <strong>the</strong>ir drive for real estate and o<strong>the</strong>r assets. The<br />

suppression and wanton destruction of <strong>the</strong>se civilizations by European civilizations<br />

was in many ways a case of inferior civilizations overcoming superior ones.<br />

This is especially true in <strong>the</strong> area of human and civil rights.<br />

Many Whites have written articles and books about Micmac history based on<br />

early descriptions of Micmac civilization made by European historians. Many<br />

of <strong>the</strong>se efforts have been undertaken with sincerity and honesty, but most, if not<br />

all, are lacking in one regard: <strong>the</strong>y fail to judge events from a Micmac<br />

perspective. It is essential to understand that <strong>the</strong> values of <strong>the</strong> two cultures were<br />

in most cases completely opposite.<br />

Even more contemporary authors who have written about Aboriginal history,<br />

have to some extent used European standards to evaluate <strong>the</strong> relative merits of<br />

◄ 4 CIVILIZATION, DEMOCRACY, AND GOVERNMENT

◄<br />

◄<br />

<strong>the</strong>se civilizations. But one must understand that <strong>the</strong> ability to read or write a<br />

European language does not necessarily create a superior person; and <strong>the</strong> ability<br />

to point exploding sticks that cause instantaneous death or injury, or <strong>the</strong><br />

capability to blow <strong>the</strong> world apart are hardly <strong>the</strong> basis for declaring one’s culture<br />

civilized.<br />

The question to ask when judging <strong>the</strong> values and merits of a civilization must<br />

always be: “How does <strong>the</strong> civilization respond to <strong>the</strong> human needs of its<br />

population?” By this standard, most Aboriginal civilizations must be given very<br />

high marks, because <strong>the</strong>y endeavoured to create for <strong>the</strong>ir peoples social and<br />

political systems that ensured both personal liberty and social responsibility.<br />

Micniac The Micmac Jiavc lived-in nor<strong>the</strong>astern North America for<br />

Government approximately 10,000 years. Although not as technologically<br />

advanced as Europeans, down through <strong>the</strong> ages <strong>the</strong>y developed<br />

one of <strong>the</strong> most democratic political systems that has ever existed. At this point<br />

in history <strong>the</strong>y had few peers, if any, in <strong>the</strong> field of equitable democratic political<br />

practices.<br />

The Tribe lived within seven distinct “Districts.” Each District had its own<br />

territory and a government made up of a “District Chief’ and a “Council”<br />

comprised of “Elders,” “Band or Village Chiefs,” and o<strong>the</strong>r distinguished<br />

members of <strong>the</strong> community. A District government had all <strong>the</strong> powers that are<br />

vested in our modem governments. It had <strong>the</strong> conditional power to make war or<br />

peace, settle disputes, and apportion hunting and fishing areas to families, and<br />

so on. Thus each District may be likened to what we call a “country” today./<br />

The names of <strong>the</strong> seven Micmac Districts were: Kespukwitk, Sipekne'katik,<br />

Eskikewa’kikx, Unama’kik, Epekwitk Aqq Piktuk, Sikmkt, and Kespek. The<br />

approximate boundaries of th,e vast territory governed by <strong>the</strong> Districts is showiy<br />

on page 6. As one can see[ Micmac territory covered most of what is today '<br />

Canada’s Maritime Provinces and a good part of eastern Quebec; and <strong>the</strong>re is/<br />

evidence that <strong>the</strong> boundary line may have included nor<strong>the</strong>rn Maine. The English S<br />

translations of <strong>the</strong> Micmac names for <strong>the</strong> Districts are shown adjacent to <strong>the</strong><br />

Districts’ names on <strong>the</strong> map. These translations are as close as one can come to<br />

conveying <strong>the</strong>ir true meaning.<br />

The citizens of <strong>the</strong>se Districts lived in small villages that contained fifty to<br />

five hundred people. Although <strong>the</strong>jrumber oDvillages within <strong>the</strong> Districts, is.<br />

subject to conjecture, <strong>the</strong> total population of <strong>the</strong> combined NationsjJtabahjy—<br />

exceeded-TOGTlOOr-1^<br />

In addition to District Councils, <strong>the</strong>re was a “Grand Council” whose membership<br />

was composed of <strong>the</strong> seven District Chiefs. From among <strong>the</strong>ir number <strong>the</strong><br />

District Chiefs chose a “Grand Chief.” The Grand Council did not have—<br />

beyond friendly persuasion and <strong>the</strong> esteem in which <strong>the</strong> Chiefs were held—any<br />

special powers o<strong>the</strong>r than those assigned to it by <strong>the</strong> Districts. Its main functions<br />

were to act as a dispute mediator of last resort when requested by a District<br />

L-'-<br />

WE WERE NOT THE SAVAGES 5 ►

Kespukwitk<br />

Land Ends<br />

The Land of <strong>the</strong>

Council and as a means to move <strong>the</strong> agendas of several Districts forward in<br />

concert. At sittings of <strong>the</strong>se Councils, all men and women who wanted to speak<br />

were heard. Their opinions were always given respectful consideration in <strong>the</strong><br />

decision-making process.<br />

Grand Chiefs, District Chiefs, and local Chiefs were generally very well<br />

respected members of <strong>the</strong>ir communities. An ambition to become Chief, so we<br />

are told in certain European accounts of Micmac history, was helped by being<br />

a member of a large family. The truth is that <strong>the</strong> entire community considered<br />

tltemselvusTo he«5ombars-of:€me-e*ten4ed-famiiy-and

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

first among a hundred wretched men, or more, or less, according to <strong>the</strong> size<br />

of his domain.2<br />

By comparison, <strong>the</strong> British notion of leadership was one of enforced respect.<br />

Even <strong>the</strong> most minor offense against an official was met with swift retribution.<br />

This practice is illustrated in <strong>the</strong> minutes of a Council meeting held at Annapolis<br />

Royal on September 22nd, 1726, during which a Mr. Robert Nichols was found<br />

guilty of insulting <strong>the</strong> Governor of <strong>the</strong> province.<br />

After a very short trial, Mr. Nichols was found guilty of <strong>the</strong> offense and<br />

sentenced. “In order to terrify <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r Citizens,” <strong>the</strong> following punishment<br />

was prescribed: For three days, he was to sit upon a gallows for a half hour each<br />

day with a rope around his neck and a paper upon his breast with <strong>the</strong> words<br />

“AUDACIOUS VILLAIN.” Afterwards, he was to be whipped with a cat-o’-nine-<br />

tails at <strong>the</strong> rate of five stripes upon his bare back every one hundred paces, from<br />

<strong>the</strong> prison to <strong>the</strong> uppermost house of <strong>the</strong> Cape and back again. Then he was to<br />

be turned over to <strong>the</strong> army to be made a soldier.3<br />

A Grand Chief, being himself also a District Chief, had no authority to<br />

meddle in <strong>the</strong> affairs of any District o<strong>the</strong>r than his own. He would intervene in<br />

<strong>the</strong> affairs of ano<strong>the</strong>r District only after being invited to do so by <strong>the</strong> government<br />

of that District. The Grand Council may thus be compared to <strong>the</strong> modern British<br />

Commonwealth of Nations, which also has no real powers o<strong>the</strong>r than persuasion.<br />

Micmac Districts also belonged to a larger association known as <strong>the</strong> “Wabanaki<br />

Confederacy.” The Confederacy was constituted and organized by <strong>the</strong> Tribes<br />

that inhabited <strong>the</strong> eastern coast of North America, primarily to provide protection<br />

against invasion by Iroquoian Tribes. The Confederacy continued to function<br />

until <strong>the</strong> early 1700s, when <strong>the</strong> decimation of its member Nations caused by<br />

disease, and wars with <strong>the</strong> British brought about its demise. The Confederacy<br />

may be compared to <strong>the</strong> modern North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in<br />

function.<br />

Midliac The Micmac had a well developed religion based upon respect for<br />

Religion nature or “Mo<strong>the</strong>r Earth,” ra<strong>the</strong>r than upon <strong>the</strong> “blind faith” that<br />

and forms <strong>the</strong> foundation of many religious systems. “Mo<strong>the</strong>r Earth”<br />

◄ Culture was <strong>the</strong> giver of all <strong>the</strong> essentials of life. The People recognized that<br />

revered and respected.<br />

without Her providence life would cease to exist, thus she was<br />

Above Mo<strong>the</strong>r Earth, was a supreme Being, <strong>the</strong> “Great Spirit,” who was<br />

responsible for all existence and was personified in all things: <strong>the</strong> rivers, <strong>the</strong><br />

trees, families and friends. His dominion was all-inclusive, and He characterized<br />

all positive attributes such as love, kindness, compassion, knowledge, and<br />

wisdom.<br />

By comparison, European civilizations practised various religions under <strong>the</strong><br />

name of “Christianity.” Christianity also acknowledges a supreme Being but<br />

one who in addition to possessing all good qualities, has several bad qualities<br />

◄ 8 CIVILIZATION, DEMOCRACY, AND GOVERNMENT

as well such as jealousy and vengefulness. Horrendous events such as <strong>the</strong><br />

inquisitions were conducted and condoned under <strong>the</strong> authority of Christianity.<br />

Innocent people who could not defend <strong>the</strong>mselves against charges of heresy<br />

were found guilty and thrown in prison or burned at <strong>the</strong> stake.<br />

The Whites branded <strong>the</strong> Micmac as “hea<strong>the</strong>n savages” because of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

i religious beliefs. One of <strong>the</strong> practices that marked <strong>the</strong> Aboriginals as “savages”<br />

i in <strong>the</strong> European mind was <strong>the</strong> offering of tobacco and o<strong>the</strong>r tokens to <strong>the</strong> Great<br />

Spirit as a mark of respect and humility. Yet <strong>the</strong> Whites’ offerings of bread,<br />

I wine, incense, and o<strong>the</strong>r things to <strong>the</strong>ir God as tokens of humility and respect<br />

was called “Christian” and “civilized.” Some Europeans, especially religious<br />

j leaders, found it very strange that <strong>the</strong> Aboriginals viewed <strong>the</strong> Great Spirit as a<br />

likeness of <strong>the</strong>mselves; however, <strong>the</strong> Europeans did not find it strange that <strong>the</strong>y<br />

saw <strong>the</strong>ir own God as a White man.<br />

The Micmac, like o<strong>the</strong>r Tribes, had a land for <strong>the</strong>ir dead similar to what <strong>the</strong><br />

Christian religions called “Heaven.” It was a place of eternal rest, peace, and<br />

happiness. “Evil spirits” were also part of Micmac belief. They believed that<br />

<strong>the</strong>se spirits were <strong>the</strong> cause of disease, natural catastrophes, famine, and all<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r evils that from time to time afflict humankind, and that even <strong>the</strong> Great<br />

Spirit required assistance to overcome <strong>the</strong> powers of <strong>the</strong>se evil spirits. To this<br />

end <strong>the</strong>y offered tokens of appeasement. There is no evidence that <strong>the</strong> People<br />

used evil spirits to terrorize and intimidate one ano<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

In contrast, Christianity’s “demons,” <strong>the</strong> "Devil” among <strong>the</strong>m, were used by<br />

priests and ministers to strike <strong>the</strong> fear of God into o<strong>the</strong>rs. The Micmac believed<br />

<strong>the</strong> Great Spirit was goodness incarnate and thus <strong>the</strong>re was no need to fear Him.<br />

The European Christians believed <strong>the</strong>ir God was to be feared because, if <strong>the</strong>y<br />

erred, He would commit <strong>the</strong>m to eternal pain and suffering. This kind of<br />

vengeful action by God was incompatible with Micmac beliefs.<br />

I Never<strong>the</strong>less, many people remark on <strong>the</strong> seeming ease with which <strong>the</strong><br />

Micmac and o<strong>the</strong>r Tribes adopted Christianity. The explanation is simply <strong>the</strong><br />

“civility” of <strong>the</strong> People. They believed that a host should make every effort to<br />

please a guest. If this required <strong>the</strong>m to worship <strong>the</strong> Great Spirit in ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

manner, <strong>the</strong>n so be it. After all, <strong>the</strong>y reasoned, if <strong>the</strong> same God is worshipped<br />

by all men, <strong>the</strong> mode of worship is incidental."'<br />

Monogamous marriages were part of Micmac culture, and although polygamy<br />

was permitted it was rarely practised. Marc Lescarbot expressed amazement<br />

that “although one husband may have many wives...yet <strong>the</strong>re is no jealousy<br />

among <strong>the</strong>m.”4 Pierre Biard wrote:<br />

According to <strong>the</strong> custom of <strong>the</strong> country, <strong>the</strong>y can have several wives, but <strong>the</strong><br />

greater number of <strong>the</strong>m that I have seen have only one; some of <strong>the</strong><br />

Sagamores pretend that <strong>the</strong>y cannot do without this plurality, not because of<br />

lust, for this nation is not very unchaste, but for two o<strong>the</strong>r reasons.<br />

One is in order to retain <strong>the</strong>ir authority and power by having a number of<br />

children; for in that lies <strong>the</strong> strength of <strong>the</strong> house; <strong>the</strong> second reason is <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

WE WERE NOT THE SAVAGES 9 ►

entertainment and service, which is great and laborious, since <strong>the</strong>y have large<br />

families and a great number of followers, and <strong>the</strong>refore require a number of<br />

servants and housewives; now <strong>the</strong>y have no o<strong>the</strong>r servants, slaves or mechanics<br />

but <strong>the</strong> women.5<br />

The head wife in a polygamous household was usually <strong>the</strong> one who had borne<br />

<strong>the</strong> first boy. The extent to which polygamy was practised has, no doubt, been<br />

exaggerated by <strong>the</strong> Jesuits and o<strong>the</strong>rs, as <strong>the</strong> result of a misperception of <strong>the</strong><br />

extended family. For example, Grand Chief Membertou had only one wife.<br />

The Micmac did not permit marriages between relations. To marry a member<br />

of one’s immediate family, including second cousins, was strictly forbidden.<br />

However, <strong>the</strong>re were no taboos against marrying in-laws.<br />

The modesty and chastity of Micmac women before and after marriage were<br />

virtues well remarked upon by those writing about <strong>the</strong> Tribe. The fact that <strong>the</strong><br />

Micmac woman took pride in her honour and would not willingly compromise<br />

herself was incredible to some European writers of <strong>the</strong> day. From <strong>the</strong>ir racist<br />

points of view, it was inconceivable that people <strong>the</strong>y considered hea<strong>the</strong>n<br />

savages would act in a more civilized manner than people from <strong>the</strong>ir own<br />

societies. They would never have accepted <strong>the</strong> notion that <strong>the</strong> people <strong>the</strong>y<br />

considered “uncivilized” were actually more civilized than <strong>the</strong>y.<br />

Special marriage rites and ceremonies were practised among <strong>the</strong> Micmac and<br />

were celebrated with great pomp, ceremony, and feasting. On <strong>the</strong>se joyous<br />

occasions many presents were exchanged between <strong>the</strong> families of <strong>the</strong> bride and<br />

groom.<br />

One of <strong>the</strong> best examples of individual freedom in Micmac society is found in<br />

its courtship customs. If a boy wished to marry a girl, he had to ask <strong>the</strong> permission<br />

of her fa<strong>the</strong>r before <strong>the</strong> courtship began. This was more of a courtesy than<br />

anything else. The fa<strong>the</strong>r would <strong>the</strong>n usually give <strong>the</strong> young man his permission<br />

to approach his daughter to ascertain if she was willing to involve herself<br />

romantically with him. This is how Chrestien Le Clercq describes <strong>the</strong> process:<br />

If <strong>the</strong> fa<strong>the</strong>r finds that <strong>the</strong> suitor who presents himself is acceptable for his<br />

daughter...<strong>the</strong>n, after having given his consent to this lover, he tells him to<br />

speak to his swee<strong>the</strong>art in order to learn her wish about an affair which<br />

concerns herself alone. For <strong>the</strong>y do not wish, say <strong>the</strong>se barbarians, to force<br />

<strong>the</strong> inclinations of <strong>the</strong>ir children in <strong>the</strong> matter of marriage, or to induce <strong>the</strong>m,<br />

whe<strong>the</strong>r by use of force, obedience, or affection, to marry men whom <strong>the</strong>y<br />

cannot bring <strong>the</strong>mselves to like.<br />

Hence it is that <strong>the</strong> fa<strong>the</strong>rs and mo<strong>the</strong>rs of our Gaspesians [Micmacs from<br />

Gaspe] leave to <strong>the</strong>ir children <strong>the</strong> entire liberty of choosing <strong>the</strong> persons whom<br />

<strong>the</strong>y think most adaptable to <strong>the</strong>ir dispositions, and most conformable to <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

affectations, although <strong>the</strong> parents, never<strong>the</strong>less, always keep <strong>the</strong> right to<br />

indicate to <strong>the</strong>m <strong>the</strong> one whom <strong>the</strong>y think most likely to be most suitable for<br />

<strong>the</strong>m.6<br />

◄ 10 CIVILIZATION, DEMOCRACY, AND GOVERNMENT

In stark contrast to European practices of <strong>the</strong> day, <strong>the</strong> Micmac did not force<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir children into loveless marriages. Love was <strong>the</strong> prime factor in creating<br />

marital bonds between Micmac couples. In Europe, especially among <strong>the</strong> elite,<br />

marriages were often entered into to enhance personal fortunes and stations in<br />

life ra<strong>the</strong>r than for love. As a result, children were sometimes “promised” at birth<br />

to individuals who <strong>the</strong>ir families considered <strong>the</strong> best prospect for <strong>the</strong> child’s<br />

future. To <strong>the</strong> Micmac this practice would have been considered uncivilized.<br />

Although not much mention of divorce is found in European records of <strong>the</strong><br />

pre-colonization Micmac, that it was practised is ano<strong>the</strong>r example of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

respect for human rights. However, because harmony in relationships and<br />

respect for each o<strong>the</strong>r’s needs were paramount, one can conclude that instances<br />

of divorce were rare.<br />

Funerals also called for ceremony and feasting. The Chief would be <strong>the</strong> first<br />

to speak at “<strong>the</strong> feast of <strong>the</strong> dead” and, as related by Le Clercq, he would talk<br />

about:<br />

The good qualities and <strong>the</strong> most notable deeds of <strong>the</strong> deceased. He even<br />

impresses upon all <strong>the</strong> assembly, by words as touching as <strong>the</strong>y are forceful,<br />

<strong>the</strong> uncertainty of human life, and <strong>the</strong> necessity <strong>the</strong>y are under of dying in<br />

order to join in <strong>the</strong> Land of Souls <strong>the</strong>ir friends and relatives whom <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

now recalling to memory.7<br />

O<strong>the</strong>rs spoke after <strong>the</strong> Chief, as Nicholas Denys relates:<br />

Each one spoke, one after ano<strong>the</strong>r, for <strong>the</strong>y never spoke two at a time, nei<strong>the</strong>r<br />

men or women. In this respect <strong>the</strong>se barbarians give a fine lesson to those<br />

people who consider <strong>the</strong>mselves more polished and wiser than <strong>the</strong>y.<br />

A recital was made of all <strong>the</strong> genealogy of <strong>the</strong> dead man, of that which he<br />

had done fine and good, of <strong>the</strong> stories that he had heard told of his ancestors,<br />

of <strong>the</strong> great feasts and acknowledgements he had made in large number, of<br />

<strong>the</strong> animals he had killed in <strong>the</strong> hunt, and of all <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r matters <strong>the</strong>y<br />

considered it fitting to tell in praise of his predecessors.<br />

After this <strong>the</strong>y came to <strong>the</strong> dead man; <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> loud cries and weeping<br />

redoubled. This made <strong>the</strong> orator strike a pose, to which <strong>the</strong> men and women<br />

responded from time to time by a general groaning, all at one time and in <strong>the</strong><br />

same tone. And often he who was speaking struck postures, and set himself<br />

to cry and weep with <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs.<br />

Having said all he wished to say, ano<strong>the</strong>r began and said yet o<strong>the</strong>r things<br />

than <strong>the</strong> first. Then one after ano<strong>the</strong>r, each after his fashion, made his<br />

panegyric on <strong>the</strong> dead man. This lasted three or four days before <strong>the</strong> funeral<br />

oration was finished.8<br />

Denys, although impressed with many aspects of Micmac culture, was one<br />

of those whose ability to appreciate <strong>the</strong> values of ano<strong>the</strong>r culture were severely<br />

retarded by his blind belief in <strong>the</strong> rightness of <strong>the</strong> European models.<br />

WE WERE NOT THE SAVAGES 11 ►

A European In view of <strong>the</strong> barbaric practices instigated by Columbus and<br />

A Atrocities carried on by o<strong>the</strong>r like-minded individuals, by which Aboriginal<br />

people were forced into slavery or subjected to slaughter, <strong>the</strong><br />

Catholic Church timidly intervened in 1493, when Pope Alexander VI issued a<br />

Bull that condoned conquest if it was designed to bring <strong>the</strong> Aboriginal peoples<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Americas into Christian subjugation. But nei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> Roman Catholic<br />

Church or any o<strong>the</strong>r Christian Church of <strong>the</strong> day took a hard and fast stand<br />

against those who were beginning to unleash an unholy hell upon American<br />

civilizations.<br />

In 1537, Pope Paul III issued ano<strong>the</strong>r Bull called “Sublimus Deus,” in which<br />

he stated that <strong>the</strong> Aboriginal peoples were “truly men capable of understanding<br />

<strong>the</strong> Catholic faith” and should not be destroyed as opponents of Christianity or<br />

enslaved as supposedly inferior and “dumb brutes created for our service.” This<br />

official stance of <strong>the</strong> Roman Catholic Church was restated by ano<strong>the</strong>r Pope in<br />

1639.<br />

However, in <strong>the</strong> late 1500s, many Europeans held opinions contrary to <strong>the</strong><br />

views of <strong>the</strong> Catholic Church, including members of <strong>the</strong> clergy and <strong>the</strong> blue-<br />

blooded leadership of Europe. Historically, <strong>the</strong> European ruling class had<br />

inflicted harsh forms of government, religion, and punishment upon <strong>the</strong>ir own<br />

people so it is understandable that <strong>the</strong>y would, without conscience, inflict<br />

similar brutalities upon those of a different race, creed, and colour.<br />

Besides racial considerations, one can safely conjecture that <strong>the</strong> social<br />

structures and democratic forms of government found in <strong>the</strong> Americas must<br />

have posed a serious threat to <strong>the</strong> notion of absolute power and control held by<br />

<strong>the</strong> European ruling class. This, and racism are <strong>the</strong> only plausible explanations<br />

for <strong>the</strong> savagery with which <strong>the</strong> rulers of Europe sought to destroy American<br />

civilizations.<br />

It was not until 1988 that <strong>the</strong> democratic systems of government of <strong>the</strong><br />

Micmac and o<strong>the</strong>r tribal groups that inhabited eastern North America were<br />

finally acknowledged. In November of that year, <strong>the</strong> Congress of <strong>the</strong> United<br />

States passed a resolution recognizing that <strong>the</strong> U.S. Constitution and Bills of<br />

Rights were modelled to a large extent upon <strong>the</strong> constitutions and bills of rights<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Iroquoian Nations and o<strong>the</strong>r tribal groups.<br />

◄ 12 CIVILIZATION, DEMOCRACY, AND GOVERNMENT

◄ ◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

◄<br />

The Micmac of old were a nomadic people<br />

who moved from place to place in harmony<br />

with <strong>the</strong> seasonal migrations of fish, game,<br />

and fowl. These provided <strong>the</strong> principal com¬<br />

ponents of <strong>the</strong>ir diets, but <strong>the</strong>y also practised<br />

some farming. Mo<strong>the</strong>r Earth provided <strong>the</strong>m<br />

with a bountiful, dependable, and extremely<br />

healthy food supply as well as all <strong>the</strong> materials<br />

<strong>the</strong>y needed to construct dwellings and to<br />

make clothing suited to <strong>the</strong> changing seasons.<br />

Denys, who wrote after <strong>the</strong> Micmac popu¬<br />

lation had undergone a substantial decline,<br />

describes <strong>the</strong>ir dietary habits as follows:<br />

There was formerly a much larger number<br />

of Indians than at present. They lived without<br />

care, and never ate ei<strong>the</strong>r salt or spice.<br />

They drank only good soup, very fat. It was<br />

this that made <strong>the</strong>m live long and multiply<br />

much.<br />

They often ate fish, especially seals to<br />

obtain <strong>the</strong> oil, as much for greasing <strong>the</strong>mselves<br />

as for drinking; and <strong>the</strong>y ate <strong>the</strong> Whale<br />

which frequently came ashore on <strong>the</strong> coast,<br />

especially <strong>the</strong> blubber on which <strong>the</strong>y made<br />

good cheer. Their greatest liking is for<br />

grease; <strong>the</strong>y ate as one does bread, and<br />

drink it liquid.1<br />

Cacamo was <strong>the</strong>ir greatest delicacy. The<br />

women:<br />

...made <strong>the</strong> rocks red hot, placed <strong>the</strong>m in<br />

and took <strong>the</strong>m out of <strong>the</strong> kettle, collected<br />

all <strong>the</strong> bones of <strong>the</strong> Moose, pounded <strong>the</strong>m<br />

with rocks upon ano<strong>the</strong>r larger, reducing<br />

<strong>the</strong>m to powder; <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong>y placed <strong>the</strong>m in<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir kettle and made <strong>the</strong>m boil well. This<br />

brought out a grease that rose to <strong>the</strong> top of<br />

<strong>the</strong> water, and <strong>the</strong>y collected it with a<br />

wooden spoon.<br />

They kept <strong>the</strong> bones boiling until <strong>the</strong>y<br />

yielded nothing more, and with such success<br />

that from <strong>the</strong> bones of one Moose, without<br />

counting <strong>the</strong> marrow, <strong>the</strong>y obtained five to

six pounds of grease as white as snow, and as firm as wax. It was this which<br />

<strong>the</strong>y used as <strong>the</strong>ir entire provision for living when <strong>the</strong>y went hunting. <strong>We</strong> call<br />

it Moose butter; and <strong>the</strong>y Cacamo.2<br />

No personal poverty was found among members of <strong>the</strong> Tribe because all<br />

citizens had access to <strong>the</strong> same level of support from <strong>the</strong> community. Each<br />

citizen was well aware of <strong>the</strong> laws of <strong>the</strong> culture, which dictated that all would<br />

be provided for equally and that no one in <strong>the</strong> community would be neglected<br />

or left destitute if <strong>the</strong>ir fortune should fail. The social welfare system of Micmac<br />

civilization greatly reduced anxiety and provided a “safety net” for individuals.<br />

As a result, <strong>the</strong> Micmac prior to European colonization had a relatively low<br />

level of stress in <strong>the</strong>ir lives. This, combined with a healthy diet, blessed <strong>the</strong> early<br />

Micmac with unusually long life spans. Comparing <strong>the</strong>ir comfortable and<br />

serene lifestyle with <strong>the</strong> hardships <strong>the</strong>n being endured by much of <strong>the</strong> world’s<br />

population living in o<strong>the</strong>r civilizations, <strong>the</strong> Tribe was extremely well off.<br />

This state of affairs slowly began to change after <strong>the</strong> onset of European<br />

colonization. By <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> seventeenth century <strong>the</strong> Micmac economy and<br />

social environment had been altered so drastically by <strong>the</strong> intrusion of European<br />

values that hardship and <strong>the</strong> threat of starvation had become constant companions.<br />

These changes in its lifestyle, and various forms of genocide, would bring <strong>the</strong><br />

Tribe to <strong>the</strong> brink of extinction by <strong>the</strong> middle of <strong>the</strong> nineteenth century.<br />

The civilization created by <strong>the</strong> Micmac was, like most o<strong>the</strong>rs of <strong>the</strong> day,<br />

male-dominated. The males provided food for <strong>the</strong>ir communities by hunting<br />

and fishing. The chores of farming and of collecting, cleaning, and preserving<br />

<strong>the</strong> produce, game, and fish were done by <strong>the</strong> women and children. Even though<br />

jobs were allotted strictly along gender and age lines, this does not imply a lack<br />

of respect for women and children. They both held extremely important and<br />

respected places in Micmac society.<br />

The children were raised in an atmosphere of benevolent devotion. They<br />

were loved and cherished by <strong>the</strong>ir parents and given loving care and attention<br />

by members of <strong>the</strong> Tribe. As a result of this ingrained attitude, Micmac children<br />

were never abandoned. They were considered extended family by adult members<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Tribe and were treated like one’s own. If a child became homeless for any<br />

reason, he or she would be adopted by o<strong>the</strong>r members of <strong>the</strong> community and<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir life would soon return to normal.<br />

Adoptions were simple. If a child could not be cared for by its natural parent<br />

or parents for one reason or ano<strong>the</strong>r, or if a child had been orphaned, a childless<br />

couple, or a couple with children, would simply take <strong>the</strong> child into <strong>the</strong>ir family.<br />

The child would <strong>the</strong>n be treated by <strong>the</strong> community as though it was <strong>the</strong> couple’s<br />

own natural-born.<br />

The education of children began at a young age and continued into early<br />

adulthood. They were taught <strong>the</strong> legends and <strong>the</strong> basic skills and knowledge<br />

deemed necessary to ensure <strong>the</strong> Nation’s survival. However, as in all civilizations,<br />

◄ 14 MICMAC SOCIAL VALUES AND ECONOMY

Mo<strong>the</strong>r Earth provides.<br />

<strong>the</strong> maturation of <strong>the</strong>ir capabilities and understanding came in adulthood<br />

through experience and experimentation.<br />

Living in close proximity to <strong>the</strong> sea not only provided <strong>the</strong> Micmac with a<br />

bountiful supply of nourishing foods, it allowed <strong>the</strong>m to develop exceptional<br />

skills in seamanship. Their abilities later earned <strong>the</strong>m <strong>the</strong> reputation among<br />

some of <strong>the</strong>ir British and French peers of being among <strong>the</strong> greatest sailors on<br />

earth. During <strong>the</strong>ir wars with <strong>the</strong> British, <strong>the</strong> Micmac routinely commandeered<br />

European war and merchant ships and sailed <strong>the</strong>m up and down <strong>the</strong> eastern coast<br />

of North America with such great skill that it seemed <strong>the</strong>y were born to it.<br />

Fa<strong>the</strong>r Lallement wrote a letter in 1659 that described Micmac seamanship<br />

thus: “It is wonderful how <strong>the</strong>se savage mariners navigate so far in little<br />

shallops, crossing vast seas without compass, and often without sight of <strong>the</strong> sun,<br />

trusting to instinct for <strong>the</strong>ir guidance.”3<br />

The “shallops” (actually canoes) referred to by Fa<strong>the</strong>r Lallement were<br />

routinely used by members of <strong>the</strong> Tribe to cross <strong>the</strong> Bay of Fundy, <strong>the</strong> Northumberland<br />

Strait, and <strong>the</strong> North Atlantic between Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. This skill<br />

probably had more to do with an ability to read tides, currents, and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

directional information than with instinct. The Micmac were truly a maritime<br />

people who worked <strong>the</strong> sea with great effectiveness for communal benefit.<br />

The recreational and entertainment needs of <strong>the</strong> Tribe were fulfilled by<br />

various social activities and functions. Variations of some of <strong>the</strong>se are still<br />

practised today by <strong>the</strong> world's different cultures. Dancing and feasting to<br />

WE WERE NOT THE SAVAGES 15 ►

commemorate small and great occasions were deep-rooted parts of <strong>the</strong> Nation’s<br />

social life. The People enjoyed recreational games such as waltes, which is still<br />

played to this day. The Micmac also participated in canoe racing, archery, and<br />

physical contact sports among <strong>the</strong>mselves and in competitions with neighbouring<br />

Tribes.<br />

Besides being keen sportsmen, <strong>the</strong> Micmac were skilled and imaginative<br />

storytellers. Tales were told for a dual purpose: education and entertainment.<br />

They told of <strong>the</strong> escapades of many legendary heros. Featured in many stories<br />

was Glooscap, who, according to legend, had been endowed by <strong>the</strong> Great Spirit<br />

with supernatural powers. (One story tells how Glooscap, who was able to take<br />

many forms, turned himself into a beaver, became angry and slapped his tail five<br />

times upon <strong>the</strong> waters of <strong>the</strong> Bay of Fundy with such force that enough earth was<br />

stirred up to create <strong>the</strong> five islands that are today located off <strong>the</strong> Nova Scotia<br />

coast near Economy Mountain.)<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r form of recreation for <strong>the</strong> Micmac was <strong>the</strong> production of beautiful<br />

works of art. The women in particular were, and still are, highly creative and<br />

skilled artisans. Their talents are witnessed today in <strong>the</strong>ir quality carvings,<br />

paintings, and o<strong>the</strong>r masterpieces, and in <strong>the</strong>ir stunningly beautiful quill work<br />

and basket weaving. Micmac artists are today actively involved in <strong>the</strong> full range<br />

of traditional and modern arts and crafts.<br />

Before European colonization and for a considerable time <strong>the</strong>reafter, because<br />

of <strong>the</strong>ir secure and stable lifestyles, <strong>the</strong> Micmac were, as a people, exceptionally<br />

well adjusted mentally. Mental illness was a rarity among <strong>the</strong>m and, when it did<br />

occur, was treated with compassion and without social stigma. By comparison,<br />

European civilizations of <strong>the</strong> period considered mental illness to be a social<br />

aberration that should be concealed. As a result, hellholes called lunatic<br />

asylums housed <strong>the</strong>ir mentally ill in deplorable and pitiful squalor.<br />

The use of psychology, instead of punitive measures, by Aboriginal Americans<br />

to persuade people to behave in an appropriate manner seems to have been a<br />

polished skill, and was used extensively in personal and community relationships.<br />

Because of a complete absence of evidence to <strong>the</strong> contrary, one can conclude<br />

that <strong>the</strong> Micmac, except in rare and exceptional cases, never used methods o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

than friendly persuasion and gentle psychology to compel individuals to comply<br />

with <strong>the</strong> laws of <strong>the</strong> community. Shunning and <strong>the</strong> death penalty were used<br />

rarely and only in extreme cases. In fact, many Europeans wrote unflattering<br />

comments about <strong>the</strong> permissiveness prevalent within Aboriginal civilizations.<br />

From <strong>the</strong> European perspective, force was <strong>the</strong> only truly effective method to<br />

assure compliance.<br />

The social values of <strong>the</strong> pre-colonial Micmac were so different from those of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Europeans that few similarities can be found. The values of <strong>the</strong> Micmac were<br />

those of a people who had great respect for human dignity and freedoms. Greedy<br />

desire for personal material gain and dictatorial power was virtually non¬<br />

existent in <strong>the</strong>ir society. In contrast, <strong>the</strong> values of <strong>the</strong> major European powers<br />

◄ 16 MICMAC SOCIAL VALUES AND ECONOMY

Preparing tomorrow’s provider.<br />

were almost exclusively based upon <strong>the</strong> over-riding desire to acquire material<br />

wealth, and <strong>the</strong> principal reason individuals strove to gain great wealth was to<br />

achieve political power and social dominance over o<strong>the</strong>rs.<br />

According to Micmac social values, <strong>the</strong>re was no need to accumulate<br />

material things for oneself. Ra<strong>the</strong>r, a truly great person was one who accumulated<br />

material things for distribution to o<strong>the</strong>rs. This generosity of <strong>the</strong> Micmac was one<br />

of <strong>the</strong> reasons for <strong>the</strong>ir low esteem in European eyes. From <strong>the</strong> European<br />

perspective, an absence of ambition to accumulate personal wealth could only<br />

be <strong>the</strong> result of laziness and shiftlessness. However, <strong>the</strong> truth is that individual<br />

Micmac worked diligently to accumulate wealth in order to give it all awav. In<br />

this respect <strong>the</strong>ir viewpoints were at opposite ends of <strong>the</strong> pole.<br />

From <strong>the</strong>ir own perspectives, <strong>the</strong> Micmac and o<strong>the</strong>r Tribes considered <strong>the</strong><br />

Europeans to be stingy and selfish, inhospitable, and indifferent to <strong>the</strong> plight of<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir fellow human beings. The main goal in European societies, in <strong>the</strong><br />

estimation of <strong>the</strong> Aboriginals, was for <strong>the</strong> individual to accumulate as much<br />

wealth as possible and to dispose of very little without first being compensated.<br />

Profiteering by governments and private individuals and institutions at <strong>the</strong><br />

expense of o<strong>the</strong>rs is an ingrained trait of European civilizations. The means used<br />

by Europeans to fulfil <strong>the</strong>ir continual desires to acquire profits have been well<br />

documented in history. For <strong>the</strong> sake of profit, most European governments have<br />

at one time or o<strong>the</strong>r inflicted immeasurable misery upon certain human populations<br />

WE WERE NOT THE SAVAGES 17 ►

and prospered from this suffering. Whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> victims were <strong>the</strong>ir own people<br />

or those of a foreign nation was often of little consideration when carrying out<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir insidious agendas. In contrast, <strong>the</strong>re is no evidence to indicate that Micmac<br />

governments ever maliciously organized an assault upon human populations<br />

with cruel plunder in mind. This kind of activity would have been culturally and<br />

morally unacceptable to <strong>the</strong>m—a fur<strong>the</strong>r indication of how humane <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

civilization was.<br />

The Micmac and Europeans also differed in most o<strong>the</strong>r areas of life. For<br />

instance, attitudes towards sex and nudity in <strong>the</strong> two civilizations were vastly<br />

different. Very few, if any, sexual hang-ups were harboured by members of<br />

Micmac society. Sex was accepted for what it is, a natural act performed by<br />

consenting individuals.<br />

Premarital sex was frowned upon by <strong>the</strong> culture. However, no long-term<br />

social stigma was associated with having children out of wedlock. As a matter<br />

of fact, in some cases single women with children were especially courted by<br />

men seeking wives, because of <strong>the</strong>ir proven fertility. Upon marriage, a child<br />

who had been previously born out of wedlock to <strong>the</strong> bride would be adopted by<br />

<strong>the</strong> new husband. From that point onward, <strong>the</strong> child would be fully accepted as<br />

his natural-born son or daughter.<br />

The Micmac attitude towards sex between consenting adults was openminded<br />

and healthy, more akin to modern-day thinking about sexuality. Although<br />

both men and women had chaste attitudes, which required that sex be conducted<br />

in privacy, <strong>the</strong>y were nei<strong>the</strong>r shocked nor dismayed if <strong>the</strong> act was performed<br />

outside <strong>the</strong> legality of marriage. Virginity was not considered a virtue an<br />

unmarried woman had to take to <strong>the</strong> grave with her.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> chaste culture of <strong>the</strong> Micmac, privacy and respect for <strong>the</strong> sensibilities<br />

of o<strong>the</strong>rs was demanded from those involved in a sexual relationship. In plain<br />

language, <strong>the</strong> message was: Do what you want but do it in private.<br />

The men of <strong>the</strong> community, as in most o<strong>the</strong>r civilizations, took great exception<br />

to sexual advances being made upon <strong>the</strong>ir wives and daughters. Biard reports an<br />

incident which occurred at Port-Royal when some Frenchmen made unwelcomed<br />

advances towards some Micmac women: “They came and told our Captain that<br />

he should look out for his men, informing him that anyone who attempted to do<br />

that again would not stand much of a chance, that <strong>the</strong>y would kill him on <strong>the</strong><br />

spot.”4<br />

This reaction, however, did not mean that a Frenchman, or an individual from<br />

any o<strong>the</strong>r ethnic group, could not carry on a normal relationship with a Micmac<br />

woman. What it indicated was that <strong>the</strong> relationship was expected to be carried<br />

on according to civilized customs. The Micmac and <strong>the</strong> Acadians came to an<br />

understanding in this regard, and later on, as social exchanges developed, a<br />

great number of marriages between <strong>the</strong>m took place.<br />

The healthy attitudes <strong>the</strong> Micmac displayed towards sex shocked <strong>the</strong> puritanical<br />

Europeans, who viewed <strong>the</strong>se attitudes as a fur<strong>the</strong>r indication of <strong>the</strong> Aboriginals’<br />

◄ 18 MICMAC SOCIAL VALUES AND ECONOMY

hea<strong>the</strong>n depravity. When one reads <strong>the</strong> historical material left behind by <strong>the</strong><br />

British and by Christian missionaries, it is striking how similarly negative <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

public attitudes were towards <strong>the</strong> sexual act, semi-nudity, and nudity.<br />

Most Aboriginals also had no hang-ups about nudity. From <strong>the</strong>ir sophisticated<br />

outlook, nudity was, like sex, a natural thing. No shame was associated with<br />

one’s body. Clothing was worn for protection against <strong>the</strong> elements and for<br />

fashion display, not for modesty. This naturally healthy attitude, like <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

attitude towards sex, tended to convince <strong>the</strong> narrow-minded Europeans of <strong>the</strong><br />

hea<strong>the</strong>n and animal-like habits of <strong>the</strong> Aboriginal peoples.<br />

From <strong>the</strong> Aboriginal perspective, English attitudes towards sex and nudity<br />

must have been hilarious. The English reacted to sex as if it were <strong>the</strong> cousin of<br />

<strong>the</strong> plague, and towards nudity as if it were <strong>the</strong> work of <strong>the</strong> Devil himself. One<br />

can imagine <strong>the</strong> jokes and comments made in Aboriginal circles about <strong>the</strong>se<br />

English peculiarities.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r tenet of Micmac society that highlights <strong>the</strong> differences between <strong>the</strong><br />

two cultures was that property was held under communal ownership. Individual<br />

ownership of wealth was unheard of, as was <strong>the</strong> private ownership of land. Their<br />

strong belief that Mo<strong>the</strong>r Earth, was a superior Being made it impossible for <strong>the</strong><br />

Micmac to believe that a mere mortal could own any portion of Her. Even today,<br />

when ^Mo<strong>the</strong>r Earth decides to create a tidal wave, earthquake, volcanic<br />

eruption, or some o<strong>the</strong>r violent movement, humankind's infantile efforts to<br />

control Her may be obliterated in <strong>the</strong> blink of an eye.<br />

^ The Micmac used <strong>the</strong> principle of “equals among equals” as a guiding light<br />

in <strong>the</strong> conduct of <strong>the</strong>ir affairs. In contrast, European society was based upon a<br />

rigid class system, which has probably caused more human conflict and misery<br />

than all o<strong>the</strong>r social systems combined. The idea that people actually lived in a<br />

society that separated <strong>the</strong>m into a distinct hierarchy based upon birth, lineage,<br />

religion, profession, wealth, politics, and o<strong>the</strong>r criteria would have been beyond<br />

belief to <strong>the</strong> Micmac.<br />

The Micmac philosophy of accepting all men as equals was one of <strong>the</strong> major<br />

factors that permitted <strong>the</strong> Europeans to eventually take over <strong>the</strong> Atlantic region.<br />

If <strong>the</strong> pre-colonization Micmac had been born into a society that had operated<br />

under <strong>the</strong> class system, <strong>the</strong>y would have been afflicted with <strong>the</strong> racial and social<br />

intolerance that is inherent in such systems. The first European colonizers<br />

•would not have been accepted as peers but would have found <strong>the</strong>mselves<br />

can4^mne4-to slavery o^-death.<br />

To<strong>the</strong> Micmac, hospitality towards a fellow human being was a test of one’s<br />

civility. If pressed to <strong>the</strong> contrary <strong>the</strong>y would respond: “How could one refuse<br />

.to share <strong>the</strong> bounties of Mo<strong>the</strong>r Earth?” The White race was permitted to set up<br />

itsjxirts and settlements without much opposition because of this custom. This<br />

sense of decency towards o<strong>the</strong>rs was a major factor in <strong>the</strong> Micmac’s losing<br />

struggle with <strong>the</strong> British. Too late did <strong>the</strong> Micmac realize that <strong>the</strong>y were dealing<br />

with a people who had little appreciation of what true hospitality meant.<br />

WE WERE NOT THE SAVAGES 19 ►

In being hospitable, <strong>the</strong> Micmac would, to save face for ano<strong>the</strong>r person, agree<br />

for <strong>the</strong> moment to something <strong>the</strong>y knew to be untrue. It was considered very rude<br />

or disrespectful to pronounce someone else a liar. Their philosophy was simple:<br />

accept <strong>the</strong> sincere beliefs of <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r individual and <strong>the</strong>n proceed to win <strong>the</strong><br />

person over to <strong>the</strong> truth by tactful and diplomatic means. If this approach failed<br />

to achieve <strong>the</strong> desired result, unless <strong>the</strong> matter was of life-and-death or national<br />

importance, it was left alone. For <strong>the</strong>y felt that, in <strong>the</strong> overall scheme of things,<br />

<strong>the</strong> right or wrong of an opinion would not make that much difference.<br />

To give an example of how <strong>the</strong> Europeans viewed this behaviour, Calvin<br />

Martin noted, when discussing <strong>the</strong> Aboriginal attitude towards religious conversion,<br />

for example, that:<br />

.. .it was sometimes difficult to distinguish between genuine conversion and<br />

a tolerant assent to strange views. Their generosity even extended to <strong>the</strong><br />

abstract realm of ideas, <strong>the</strong>ories, stories, news and teachings; <strong>the</strong> Native host<br />

prided himself on his ability to entertain and give assent to a variety of views,<br />