ZEKE Magazine: Spring 2022 - Climate Issue

Sustainable Solutions to the Climate Crisis Indigenous Fire by Kiliii Yuyan The Indigenous Peoples' Burn Network is training others in an ancient technique of ecological restoration, which is to safely light low-intensity fires in wet seasons that remove the small fuels on the forest floor. Nemo's Garden by Giacomo d'Orlando Nemo’s Garden—the world’s first underwater greenhouses of terrestrial plants—represents an alternative farming system dedicated to those areas where environmental conditions make the growth of plants almost impossible. Permagarden Refugees by Sarah Fretwell The Palabek refugee settlement in Northern Uganda, with the staff of African Women Rising’s (AWR) Permagarden Program, works with refugees to utilize the existing resources—seeds, rainfall, limited land, and “waste”—and together build an agriculture system designed to help the environment regenerate and get stronger as it matures. Sustainable Solutions to the Climate Crisis by Antonia Juhasz Interview with Kiliii Yuyan by Caterina Clerici Dispatches from Ukraine by Maranie Staab Book Reviews Edited by Michelle Bogre

Sustainable Solutions to the Climate Crisis

Indigenous Fire by Kiliii Yuyan

The Indigenous Peoples' Burn Network is training others in an ancient technique of ecological restoration, which is to safely light low-intensity fires in wet seasons that remove the small fuels on the forest floor.

Nemo's Garden by Giacomo d'Orlando

Nemo’s Garden—the world’s first underwater greenhouses of terrestrial plants—represents an alternative farming system dedicated to those areas where environmental conditions make the growth of plants almost impossible.

Permagarden Refugees

by Sarah Fretwell

The Palabek refugee settlement in Northern Uganda, with the staff of African Women Rising’s (AWR) Permagarden Program, works with refugees to utilize the existing resources—seeds, rainfall, limited land, and “waste”—and together build an agriculture system designed to help the environment regenerate and get stronger as it matures.

Sustainable Solutions to the Climate Crisis

by Antonia Juhasz

Interview with Kiliii Yuyan by Caterina Clerici

Dispatches from Ukraine by Maranie Staab

Book Reviews Edited by Michelle Bogre

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>ZEKE</strong>SPRING <strong>2022</strong> VOL.8/NO.1 $15 US<br />

THE MAGAZINE OF GLOBAL DOCUMENTARY<br />

Published by Social Documentary Network<br />

Sustainable Solutions to the <strong>Climate</strong> Crisis<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 1

SPRING <strong>2022</strong> VOL.8/ NO.1<br />

$15 US<br />

Sustainable Solutions to the <strong>Climate</strong> Crisis<br />

Photo by Kiliii Yuyan from Indigenous Fire<br />

Photo by Giacomo d'Orlando from Nemo's<br />

Garden<br />

Photo by Sarah Fretwell from Permagarden<br />

Refugees<br />

2 | INDIGENOUS FIRE<br />

Photographs by Kiliii Yuyan<br />

CO-WINNER OF <strong>2022</strong> <strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD FOR SYSTEMIC CHANGE<br />

16 | NEMO'S GARDEN<br />

Photographs by Giacomo d'Orlando<br />

CO-WINNER OF <strong>2022</strong> <strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD FOR SYSTEMIC CHANGE<br />

26 | PERMAGARDEN REFUGEES<br />

Photographs by Sarah Fretwell<br />

36 | SUSTAINABLE SOLUTIONS TO THE CLIMATE CRISIS<br />

by Antonia Juhasz<br />

42 |<br />

52 |<br />

54 |<br />

56 |<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> Award Honorable Mention Winners<br />

Interview with Kiliii Yuyan<br />

by Caterina Clerici<br />

Dispatches from Ukraine<br />

by Maranie Staab<br />

Book Reviews<br />

Edited by Michelle Bogre<br />

62 | Contributors<br />

Photo by Andi Rice from Sustainable Solutions to<br />

the <strong>Climate</strong> Crisis<br />

Photo by Maranie Staab from Dispatches from<br />

Ukraine.<br />

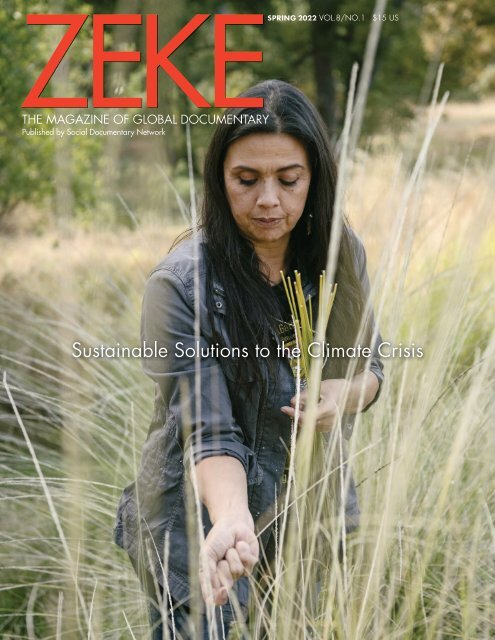

On the Cover<br />

Ali Meders-Knight, Master TEK Practitioner<br />

and Mechoopda tribal member, harvests grass<br />

stems from deergrass (Ósoko sáwi), that have<br />

been selectively-managed through the use of<br />

indigenous prescribed burns at Verbena Fields<br />

in Chico, California. Photo by Kiliii Yuyan.

<strong>ZEKE</strong><br />

THE<br />

Subscribe to <strong>ZEKE</strong> today and<br />

receive print edition. Learn more » »<br />

MAGAZINE OF<br />

GLOBAL DOCUMENTARY<br />

Published by Social Documentary Network<br />

Dear <strong>ZEKE</strong> Readers:<br />

I am incredibly excited to have guest-edited this issue of <strong>ZEKE</strong><br />

magazine dedicated to showcasing sustainable solutions to the<br />

climate crisis. As image makers, we hold a unique power to confront<br />

audiences with uncomfortable truths, advance cultural understandings,<br />

and promote social justice. But the image is only the beginning of the<br />

conversation. The real work of social transformation lies in the removal<br />

of barriers – physical, social, economic, and spiritual – that restrain<br />

us from forging futures that are more equitable, just, and sustainable.<br />

By way of example, the Earthrise photograph of 1968 radically<br />

changed our conceptions of ourselves and this incredibly precious<br />

world that we call home. But it was the legislation that followed – the<br />

Clean Water Act of 1972, the Endangered Species Act of 1973, the<br />

Superfund Act of 1980 – that created the structural change that the<br />

new realization of our planet required.<br />

In the 21 st century, we must move beyond merely documenting the<br />

consequences of global warming—floods, fires, hurricanes, rising<br />

seawater, and other environmental anomalies—since this is all now<br />

known as fact. Rather, we must now shift our focus to stories of hope,<br />

leadership, and sustainable solutions that communities across the<br />

planet are pioneering to reduce global warming and prevent climate<br />

change from causing cataclysmic destruction to the global human<br />

community. Critically, for a solution to be truly sustainable, it has to<br />

tackle not only the climate crisis (which is the fire in our house) but<br />

also the systemic conditions that gave rise to the fire in the first place:<br />

the broader social-economic paradigm of extraction, colonialism,<br />

and unchecked consumption. If we support such systemic solutions,<br />

not only will we put out the fire, but we stand to create a world that is<br />

more equitable, diverse, inclusive, and beautiful.<br />

Right now, all over the planet, these innovations are quietly coming<br />

online, driven by people who I like to call ‘everyday visionaries’:<br />

compassionate, hardworking, often ordinary folks who are fighting<br />

for their families and their homelands by molding the political will,<br />

building the cultural frameworks, and inspiring the imagination that<br />

we need to make the transition towards a more sustainable world.<br />

It may not be happening fast enough, and it may not be getting the<br />

press that it deserves, but a new world is being born. I’ve seen it.<br />

The fact is, we have a choice in the stories we tell, and the choices<br />

we make today will give rise to the world we inherit tomorrow. So, let’s<br />

choose to tell the stories of those who are laboring to bring forth a world<br />

befit of our children. As a parent myself, I can think of no worthier cause.<br />

Michael O. Snyder<br />

Guest Editor<br />

It has been such an honor to work with guest editor<br />

Michael O. Snyder and all the photographers and<br />

writers who have contributed to this issue of <strong>ZEKE</strong>. I<br />

also want to thank the Foundation for Systemic Change<br />

for their generous financial support both for the <strong>ZEKE</strong><br />

Award for Systemic Change and for this issue of the<br />

magazine.<br />

When we began planning the theme last<br />

September, it was clear that climate change was the<br />

greatest existential threat facing our planet. Now, in<br />

just the past four weeks as of writing this letter the<br />

world has been turned upside down, yet again. This<br />

time by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the threat<br />

of the first use of nuclear weapons (excluding testing)<br />

since atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and<br />

Nagasaki 77 years ago.<br />

As the war continues unabated, much of the world<br />

is also reeling from the skyrocketing costs of energy<br />

and grain. Putin would not have been able to launch<br />

this war without the wealth afforded to him through<br />

the extraction and sale of oil and our dependence on<br />

fossil fuels. Now that the war is underway, the world<br />

could have been more resilient to the rising price<br />

of fossil fuels and grains if we had relied more on<br />

renewable energy from solar, wind, hydro and other<br />

sources, and had been further along with sustainable<br />

agricultural practices.<br />

The solutions to the climate crisis presented in this<br />

issue of <strong>ZEKE</strong> largely focus on a recognition of the<br />

fragile ecology of our planet and a move away from<br />

extractive mining that ravages the environment. Also<br />

evident is the understanding that Indigenous cultures<br />

have always had about the interdependence of homo<br />

sapiens and other species. While some may quiver at<br />

the thought of the sacrifices we will need to make in<br />

order to live in a sustainable world, just the opposite<br />

may be true. As we learn to embrace a new respect for<br />

the land that supports all life on this planet, humanity<br />

will become richer spiritually and in our health and<br />

well-being.<br />

Glenn Ruga<br />

Executive Editor<br />

Matthew Lomanno<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 1

<strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD FOR SYSTEMIC CHANGE<br />

FIRST-PLACE WINNER<br />

Indigenous Fire<br />

Photos by<br />

Kiliii Yuyan<br />

United States<br />

Despite the intense focus on apocalyptic<br />

wildfires raging across the<br />

American West, scant attention<br />

is paid to solutions to climate<br />

change-exacerbated wildfire. One<br />

in particular–fire-lighting rather<br />

than fire-fighting–has proven to be an<br />

exceptional weapon against a seemingly<br />

impossible opponent on a landscape-level<br />

scale. It’s known as cultural fire. People<br />

like Margo Robbins and Elizabeth Azzuz<br />

of the Indigenous Peoples’ Burn Network<br />

are training others in an ancient technique<br />

of ecological restoration, which is to safely<br />

light low-intensity fires in wet seasons that<br />

remove the small fuels on the forest floor.<br />

Not only does it effectively prevent wildfires<br />

from spreading, but it also performs a<br />

13,000-year-old function—the restoration of<br />

health of the forests of Northern California,<br />

the most diverse coniferous forests on earth.<br />

Kiliii Yuyan illuminates stories of the Arctic<br />

and human communities connected to the<br />

land and sea. Informed by ancestry that is<br />

both Nanai/Hèzhé (East Asian Indigenous)<br />

and Chinese American, he explores the<br />

human relationship to the natural world from<br />

different cultural perspectives and extreme<br />

environments, on land and underwater. Kiliii<br />

is an award-winning contributor to National<br />

Geographic, TIME, and other major publications.<br />

Kiliii is one of PDN’s 30 Photographers<br />

(2019), a National Geographic<br />

Explorer, and a member of Indigenous<br />

Photograph and Diversify Photo. His work<br />

has been exhibited worldwide and received<br />

some of photography’s top honors.<br />

Margo Robbins, of the Cultural Fire<br />

Management Council, leads firefighters<br />

as they light an Indigenous-prescribed<br />

burn with bundles of wormwood in<br />

ceremony, near Weitchpec, CA.<br />

2 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 3

The open view of a Yurok culturally<br />

burned area in Orleans, CA. The airy,<br />

open nature of the forest here contrasts<br />

the tight and fire-prone unburnt forest<br />

in the background. The continuation<br />

of ancient cultural burning reminds<br />

us what is possible in fire-prone<br />

California. Photo by Kiliii Yuyan.<br />

4 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

Subscribe to <strong>ZEKE</strong> today and<br />

receive print edition. Learn more » »<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 5

Firefighters practice controlled burning,<br />

coordination, and fire management<br />

skills while participating in a Yurok-led<br />

cultural fire training exchange (TREX)<br />

near Weitchpec, CA, Although the widely<br />

used practice of burning brush piles is<br />

not traditional, it is a skillset that supports<br />

Indigenous burning. Photo by Kiliii Yuyan.<br />

6 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 7

8 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong><br />

Margo Robbins not only leads Training<br />

Exchanges, but also weaves her culture’s<br />

celebrated baskets. “We use TREX<br />

to ensure the continuance of our culture<br />

and protect cultural resources. Our<br />

culture is fire dependent. Our people<br />

are hunters, gatherers and basket weavers,”<br />

says Robbins. “Restoration of the<br />

land, and preservation of our culture, is<br />

a number one priority for people living<br />

on the Yurok Reservation. We MUST put<br />

fire on the ground if we are to continue<br />

the tradition of basket weaving.” Photo<br />

by Kiliii Yuyan.

Dr. Frank Lake cracks and<br />

extracts a beaked hazelnut from<br />

its shell. The hazelnuts grow<br />

on his property in Orleans, CA<br />

where they are carefully managed<br />

through traditional Yurok<br />

prescribed burning. Photo by<br />

Kiliii Yuyan.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 9

10 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

A Yurok firefighter manages the boundary<br />

of an Indigenous-prescribed burn<br />

near Weitchpec, CA during a fire<br />

training exchange, or TREX in October.<br />

In recent years, Indigenous-prescribed<br />

fire practices have come to attention as<br />

wildfires have raged destructively across<br />

California. Photo by Kiliii Yuyan.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING FALL 2021/ <strong>2022</strong>/ 11

Firefighters refill their drip torches in<br />

the midst of a broadcast-prescribed<br />

burn while participating in a training<br />

exchange put on by the Cultural Fire<br />

Management Council near Weitchpec,<br />

CA. Photo by Kiliii Yuyan.<br />

12 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 13

An experienced Yurok TREX leader<br />

lays down fire with his drip torch,<br />

careful not to get caught behind his<br />

lines. Photo by Kiliii Yuyan.<br />

14 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 15

<strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD FOR SYSTEMIC CHANGE<br />

FIRST-PLACE WINNER<br />

Nemo’s Garden<br />

Photos by Giacomo d'Orlando<br />

Italy<br />

According to the Intergovernmental Panel<br />

on <strong>Climate</strong> Change, the desertification<br />

caused by climate change has extensively<br />

reduced agricultural productivity in many<br />

regions of the world. Current population<br />

projections predict a population of<br />

10 billion by the end of the century, creating an<br />

additional two billion mouths to feed. It is urgent,<br />

then, to find an alternative method of cultivation<br />

to ensure an ecologically sustainable future.<br />

Nemo’s Garden—the world’s first underwater<br />

greenhouses of terrestrial plants—represents an<br />

alternative farming system dedicated to those<br />

areas where environmental conditions make the<br />

growth of plants almost impossible. The microclimate<br />

and thermal conditions within the biospheres<br />

are optimal for plant growth and crop yields. The<br />

encouraging results, where more than 40 different<br />

species of plants have been successfully cultivated,<br />

give us hope that we have found a sustainable<br />

agricultural system that will help us tackle the<br />

new challenges posed by climate change.<br />

Giacomo d’Orlando is an Italian documentary<br />

photographer focused on environmental and<br />

social issues. In 2015, he moved to Nepal and<br />

then Peru to enter the world of photojournalism,<br />

working alongside local NGOs focusing on social<br />

issues. His subsequent time in Australia and New<br />

Zealand inspired him to concentrate on the environment,<br />

particularly the possible future scenarios<br />

caused by climate change. His projects have<br />

appeared in The Washington Post, Der Spiegel,<br />

Paris Match, El Pais, Geo France, De Volkskrant,<br />

D-La Repubblica and Mare Magazin, among others.<br />

Today, his work looks at how the increasing<br />

pressures brought about by climate change are<br />

reshaping the planet and how present-day society<br />

is reacting to the new challenges that will<br />

characterize our future.<br />

The dark silhouette of Gabriele<br />

Cucchia, senior engineer of the Nemo’s<br />

Garden project, seen from the seabed<br />

while carrying the upper part of the<br />

biosphere to the installation site.<br />

16 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 17

18 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

Subscribe to <strong>ZEKE</strong> today and<br />

receive print edition. Learn more » »<br />

A group of divers admire the Nemo's<br />

Garden during their immersion. Since<br />

the Nemo's Garden has been created,<br />

the fish population of the area<br />

increased. In fact the Nemo's Garden<br />

structure acts as a shelter for many<br />

animals, supporting the repopulation<br />

of the surrounding area. Photo by<br />

Giacomo d'Orlando.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 19

Emilio Mancuso, biologist in charge<br />

of the seeding and growing process<br />

of the plants, is placing the coconut<br />

fiber cones for the hydroponic<br />

cultivation within the biospheres. Each<br />

biosphere can host approximately<br />

120 per cycle, which depending on<br />

the plants type, can last from one<br />

to three months. Photo by Giacomo<br />

d'Orlando.<br />

20 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 21

The tree of life stands out among the<br />

biospheres in the middle of the Nemo's<br />

Garden. Under its platform, the cables<br />

used for connecting the electronic<br />

devices are separated and distributed<br />

to each biosphere. Figuratively it also<br />

represents the core of the experiment:<br />

the possibility to grow terrestrial plants<br />

underwater. Photo by Giacomo<br />

d'Orlando.<br />

22 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 23

Basil was chosen as a model plant<br />

(due to its importance in the Ligurian<br />

cuisine) to study its phytochemical,<br />

physiological, and micro-morphological<br />

characteristics in comparison with<br />

plants of the same variety grown in<br />

a terrestrial environment. The aim of<br />

the study was the evaluation of the<br />

plant responses to this environment<br />

where the terrestrial greenhouse<br />

is substituted by an underwater<br />

biosphere. Photo by Giacomo<br />

d'Orlando.<br />

24 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 25

Inside the Palabek refugee settlement in<br />

Northern Uganda, with the staff of African<br />

Women Rising’s (AWR) Permagarden<br />

Program, I witnessed how this innovative<br />

approach is disrupting the broken aid<br />

system by adapting food production to the<br />

realities of climate change, changing lives and<br />

futures in the process.<br />

AWR works with refugees to utilize the<br />

existing resources—seeds, rainfall, limited<br />

land, and “waste”—and together build<br />

an agriculture system designed to help the<br />

environment regenerate and get stronger<br />

as it matures. Within two weeks, farmers<br />

are harvesting microgreens, within a month<br />

they can start eating from their gardens, and<br />

beyond that many people are able to make<br />

money selling their vegetables. Their gardens<br />

ensure needed vitamins and that mothers can<br />

produce milk to breastfeed their babies.<br />

Radical in its simplicity and effectiveness,<br />

the success of AWR’s permagarden program<br />

has tremendous implications for refugees and<br />

humans worldwide.<br />

Journalist, climate activist, and political scientist,<br />

Sarah Fretwell, works as a multimedia<br />

storyteller. Her work focuses on the intersection<br />

of the environment, people, and business with<br />

one question: What if the new bottom line<br />

was love? Her award-winning photojournalism<br />

explores the lives of everyday people with<br />

extraordinary stories and creates the human<br />

connection that engages people on a personal<br />

level, offering individuals a voice for justice,<br />

insight for solutions, and the human connection<br />

needed for international engagement.<br />

Some of her notable work and clients include<br />

the BioCarbon Fund, United Nations, USAID,<br />

The Africa Prize for Engineering Innovation,<br />

World Bank Group, and Tara Oceans<br />

Foundation.<br />

Permagarden<br />

Refugees<br />

Photos by Sarah Fretwell<br />

Uganda<br />

26 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

Yaka Lucia, in the beginnings of her<br />

Permagarden with her baby, Rosa.<br />

Before she planted her garden, they<br />

survived on rations from the World<br />

Food Program—maize, beans, flour,<br />

oil, and salt. Eating only the food<br />

rations, her breast milk dried up, and<br />

she could not feed her baby. Once<br />

she started eating the greens from<br />

her garden, her breast milk returned<br />

within two weeks. Between her<br />

Permagarden and food rations, she<br />

can now feed all of her children for<br />

the entire month.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 27

28 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

Agusti (33) arrived in Palabek<br />

camp with his family after fleeing<br />

South Sudan. His garden is<br />

thriving, and he is one of the most<br />

successful entrepreneurs in the<br />

program. He purchased a goat<br />

and opened another small business<br />

by selling surplus vegetables,<br />

increasing his income by approximately<br />

150%. Since we visited,<br />

he made enough money to move<br />

his family out of the camp. Photo<br />

by Sarah Fretwell.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 29

30 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

Subscribe to <strong>ZEKE</strong> today and<br />

receive print edition. Learn more » »<br />

Food rations are measured down<br />

to the ounce at the distribution<br />

center. Security is so tight that<br />

some refugees are even retina<br />

scanned. Allotted rations are<br />

supposed to feed one person<br />

for four weeks. However, after<br />

figuring out a way to transport the<br />

149.48 lbs of food (rations for 4<br />

for the month) and selling some<br />

of their rations to pay to grind the<br />

maize, most people only have<br />

enough food to eat one time a<br />

day for three weeks. Those who<br />

do not have Permagardens usually<br />

go without food the last week<br />

of the month. This family is dining<br />

on the staple dish of the camp<br />

maize/soya porridge. Because<br />

residents have no micronutrients<br />

due to lack of variety and green<br />

vegetables in their diet, their<br />

bodies begin shutting down, leading<br />

to issues such as brain fog,<br />

blurred eyesight, and inability<br />

to produce breast milk. Photo by<br />

Sarah Fretwell.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 31

32 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

Before planting, project mentors<br />

conduct a landscape resource walk on<br />

each family’s plot of land. On these<br />

walks, everyone discovers the variety<br />

of valuable and free waste resources<br />

around them – charcoal dust, dried<br />

manure, fallen leaves, and nutrition for<br />

the soil in the rubbish pits. Participants<br />

“walk the water,” coming to understand<br />

the flow of rainwater across their<br />

land as they learn key principles of<br />

how to manage it to their benefit. This<br />

thriving garden is several months old.<br />

Now Lakot Linda’s grandchildren can<br />

eat for the entire month and get much<br />

needed micronutrients. She is growing<br />

kale, kowpiss (spinach), pumpkins,<br />

okra, and more. Photo by Sarah<br />

Fretwell.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 33

34 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

The most happening part of<br />

town inside Palabek is called<br />

“Jerusalem.” There is a pharmacy,<br />

restaurants, hotels, a<br />

tailor, a bicycle-powered lathe<br />

for sharpening blades, shops,<br />

and a dance hall. Some of the<br />

business owners are Ugandans<br />

who have come to make money.<br />

Some are Ugandans who have<br />

come to help, and some, like the<br />

Sudanese barber, are people<br />

who arrived here with a trade.<br />

This barber was fortunate he had<br />

the foresight to bring his shears<br />

and shaver with him on the long<br />

journey from Sudan. He now<br />

runs the most popular, and only,<br />

barbershop in town. Photo by<br />

Sarah Fretwell.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 35

Nina Morgan grew up in the shadow<br />

of a coal mine. The four-room shotgun<br />

home she shared with her twin brother,<br />

mother, and grandmother is in the<br />

tiny community of Sipsey, about 30<br />

miles North of Birmingham, Alabama.<br />

More precisely, they lived in the “Black<br />

Camp,” the name still used by locals<br />

over one hundred years after the<br />

DeBardeleben Coal Company built<br />

this company town, segregating workers and<br />

their families by race. Generations of Morgan’s<br />

family have worked in the mines. Back behind<br />

the house, past the old graveyard marked with<br />

stones where great grandfather Tommy who died<br />

of Black Lung is buried, she and brother Ishmael<br />

played in “the spot”—a former blasting site filled<br />

with rainwater.<br />

Today, Morgan is the <strong>Climate</strong> & Environmental<br />

Justice Organizer for<br />

Greater Birmingham<br />

Alliance to Stop<br />

Pollution, better known<br />

by the acronym,<br />

“GASP.” “Coal is killing<br />

us. It’s breaking down<br />

our bodies,” Morgan<br />

told me. She warns of<br />

a coming reckoning<br />

bringing an end to the<br />

“legacy and history of<br />

extraction, exploitation,<br />

and violent racism”<br />

that has devastated<br />

Sipsey and much of the<br />

American South.<br />

Central to her effort is shifting Alabama away<br />

from all fossil fuels, and she has no shortage<br />

of plans to accomplish this goal. “The answers<br />

Sustainable Solutions to<br />

By Antonia Juhasz<br />

36 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

the <strong>Climate</strong> Crisis<br />

Nina<br />

Morgan, not far<br />

from her grandmother's<br />

home in Sipsey, Alabama.<br />

Photograph by Andi Rice,<br />

2021.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 37

38 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

are already there,” Morgan explains.<br />

“People in Birmingham have been<br />

thinking about this for years.”<br />

The plans start with shutting down<br />

coal operations in Sipsey and coke<br />

plants (an industrial byproduct of coal)<br />

in Birmingham, employing locals to<br />

clean up the sites and surrounding<br />

neighborhoods using bioremediation,<br />

establishing local community-owned<br />

and operated solar and agricultural<br />

farms, and passing a local Green<br />

New Deal. The sustainable solutions<br />

are clear, the problem is “the political<br />

will and the money to really scale it,”<br />

Morgan says.<br />

Morgan’s experience and analysis is<br />

repeated in interviews and investigations<br />

I’ve conducted across decades and continents.<br />

There is little mystery about how<br />

to achieve sustainable solutions to the<br />

climate crisis; to the contrary, people are<br />

now and have been implementing them<br />

for millennia. Our planet is increasingly<br />

inhospitable to us not because we lack<br />

the resources to provide for our people,<br />

but rather because a small percentage<br />

of them have adopted devastatingly<br />

harmful fossil fuel-led consumption patterns<br />

which are, in fact, relatively simple<br />

to adjust. The problem is not one of<br />

technology. Instead, it mostly boils down<br />

to power and politics: primarily a few<br />

governments and companies, and of<br />

course some consumers, who just refuse<br />

to let go.<br />

In many ways, this is a profoundly<br />

hopeful message. We know the problem,<br />

have had the means to solve it,<br />

and we’re even having a great deal of<br />

success—albeit not nearly enough.<br />

Fossil Fuels are Obsolete<br />

Fossil fuels are the leading cause of<br />

the climate crisis. The fossil fuel industry<br />

and its products account for 91%<br />

of global industrial greenhouse gas<br />

(GHG) emissions and about 70% of all<br />

human-induced climate emissions. In<br />

Chief Shirell Parfait-Dardar of the Grand Caillou/<br />

Dulac Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw at her home<br />

and garden in Chauvin, Louisiana. Photo by Virginia<br />

Hanusik, June 2021.<br />

A dead cypress tree off Tide Water Road, Venice, Louisiana. Photo by Virginia Hanusik, June 2021.<br />

the U.S., fossil fuels account for 94%<br />

of total carbon dioxide emissions and<br />

80% of all GHG emissions from human<br />

activity. As a result, the International<br />

Energy Agency recently concluded<br />

that if we are to meet the Paris <strong>Climate</strong><br />

Agreement goal of limiting global<br />

warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, there<br />

can be no new investments in fossil fuel<br />

production anywhere.<br />

We not only know the “what” of<br />

the climate crisis, but also the “who.”<br />

Since 1988, more than half of all global<br />

industrial GHG emissions can be traced<br />

to just 25 fossil fuel companies, including<br />

ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell, BP, and<br />

the national oil companies of Russia,<br />

China, and Saudi Arabia. The lack of<br />

progress on international policies to curb<br />

climate emissions are due in small part<br />

to the actions of these companies and<br />

countries (including the corporate host<br />

nations of the U.S. and Britain).<br />

Azeb Girmai is the climate policy<br />

lead for LDC Watch International, a<br />

network of civil society organizations<br />

advocating on behalf of the 48 Least<br />

Developed Countries (LDCs) in the<br />

world. On December 10, 2015, I sat<br />

across from Girmai on the outskirts<br />

of Paris at the Le Bourget conference<br />

center. Girmai made the trek from<br />

Ethiopia, then-gripped by a deadly and<br />

crippling drought, its worst in 30 years.<br />

Around us swirled a polite cacophony<br />

of activity -- regularly punctuated by the<br />

shouts of protestors chanting “1.5 to<br />

stay alive!” or “Keep It In The Ground!”<br />

-- as thousands gathered to influence<br />

the outcome of what would emerge two<br />

days later as the Paris <strong>Climate</strong> Accord.<br />

Girmai conveyed both hope and<br />

urgency as she shared her message to<br />

negotiators. Africans, who have done<br />

the least to cause the climate crisis but<br />

are suffering the worst of its impacts,<br />

have solutions, but they need support.<br />

She described local initiatives to allow<br />

Africans to leapfrog the fossil fuel stage<br />

of development and overcome the<br />

increasing hardships of global warming,<br />

including providing individual<br />

homes across rural areas with simple<br />

easy-to-use wind and solar energy kits.<br />

Localization and democratization of<br />

energy are key, particularly for women.<br />

Energy access “is the game changer for<br />

women in Africa,” Girmai said.<br />

Funding for climate change efforts is<br />

not only woefully inadequate, but also<br />

less than 10% of the $17.4 billion in<br />

climate finance from leading international<br />

institutions between 2003 and<br />

2016 targeted local initiatives such as<br />

Girmai's. <strong>Climate</strong> finance, particularly<br />

the significantly larger sums spent by<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 39

corporations, venture capital, and private<br />

equity, instead flows to large-scale<br />

centralized mega-projects frequently<br />

focused on the “next big technological<br />

fix” to the climate change problem.<br />

A few days before I spoke with<br />

Girmai, Leonardo DiCaprio, then serving<br />

as the United Nations Messenger<br />

of Peace, addressed a gathering of<br />

world leaders at the Paris City Hall. He<br />

shared a similar message to Girmai’s.<br />

“Our future will hold greater prosperity<br />

and justice when we are free from the<br />

grip of fossil fuels,” he said.<br />

He cited the work of Stanford<br />

Professor Mark Jacobson who demonstrated<br />

in 2009 that fossil fuels are obsolete.<br />

“We can meet the world’s energy<br />

demand with 100% clean renewable<br />

energy using existing technologies by<br />

2050,” DiCaprio explained, referring<br />

to all forms of energy consumption<br />

replaced with wind, water, and solar.<br />

He urged the gathered elected officials<br />

to do their part by quickly enacting<br />

policies to support a transition to low<br />

carbon transportation, energy efficient<br />

buildings, better waste management,<br />

and renewable energy.<br />

Six years later, COP26 in Scotland<br />

resulted in disappointment, but also<br />

some important achievements, including<br />

the launch of a “Beyond Oil and<br />

Gas Alliance” by 12 governments to<br />

“end all oil and gas production and<br />

exploration” on their territories.<br />

Professor Jacobson points to 10<br />

countries (with four on their way)<br />

with 97.5–100% electricity powered<br />

exclusively by renewables and laws<br />

on the books in 61 countries to meet<br />

that target. Around the world, 180<br />

cities, including in eight U.S. states,<br />

have formalized plans to reach 100%<br />

renewable energy for electricity and<br />

over 100 already get at least 70%<br />

exclusively from renewables.<br />

A recent Oxford University study<br />

finds that a rapid shift to wind, solar,<br />

and other zero-carbon technologies<br />

would save the world $26 trillion in<br />

energy costs alone (including the cost<br />

to adapt the electricity grid) while at<br />

the same time meeting the Paris <strong>Climate</strong><br />

Accord targets. Solar, wind, and other<br />

zero-carbon technologies have been<br />

decreasing in cost overtime—with solar<br />

2,000 times cheaper today than at its<br />

first commercial use in 1958—while<br />

fossil fuels are as expensive to produce<br />

and consume today as they were 150<br />

years ago.<br />

Moving energy through renewables<br />

is also more efficient than fossil fuels.<br />

Merely electrifying the energy sector<br />

reduces overall energy demand by<br />

nearly 60%, Jacobson finds. And the<br />

closer you place the user to the source<br />

of energy — i.e. localized wind and<br />

solar — the less energy is needed.<br />

Investments in public transportation<br />

should trump individual cars. To further<br />

reduce overall resource extraction of<br />

feedstocks such as lithium for batteries,<br />

Jacobson stresses the ability and<br />

necessity to increase both their recycling<br />

and reuse.<br />

There are innumerable human health<br />

and climate benefits to be won when particularly<br />

the heaviest users shed the shackles<br />

of unsustainable energy demand.<br />

Indigenous Communities<br />

are Living the Alternative<br />

“Indigenous communities are living the<br />

alternatives to the climate crisis,” said<br />

Andrea Isabel Ixchíu Hernández of<br />

Journalist Andrea Isabel Ixchíu Hernández at work in<br />

Guatemala. Photo: Federico Zuvire 2021.<br />

the K’iche de Totonicapán Indigenous<br />

community of Guatemala in October.<br />

Hernández is a fierce human rights<br />

activist, journalist, and community<br />

leader. Forests, particularly old ones<br />

such as the Amazon rainforest, provide<br />

rich carbon sinks and the biodiversity<br />

humans require to survive. Studies have<br />

repeatedly confirmed what Indigenous<br />

peoples have regularly repeated: they<br />

are the best protectors of both forests<br />

and the planet’s biodiversity — a task<br />

they’ve perfected over millennia.<br />

To survive the climate crisis requires<br />

that we “stop consuming Indigenous territories<br />

and defend the people defending<br />

the land and water,” Hernández<br />

explains. This means not only an end to<br />

the racism which has habitually favored<br />

resource extraction on the lands and<br />

Mayan Q'eqchi' Indigenous leader, Maria Choc, speaks with women in El Estor, Izabal, Guatemala. From the<br />

CuraDaTerra Documentary series by Andrea Isabel Ixchíu Hernández and Federico Zuvire, 2021.<br />

40 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

Subscribe to <strong>ZEKE</strong> today and<br />

receive print edition. Learn more » »<br />

waters of people of color, and the<br />

protection of Indigenous peoples’<br />

knowledge, rights to their land, waters,<br />

and cultures, but also addressing the<br />

inequities, injustice, and unsustainability<br />

of the world’s most abusive energy<br />

users. Without justice and equity, the<br />

transition from fossil fuels will fail to<br />

achieve sustainability.<br />

The vast majority of the world, including<br />

its Indigenous peoples, already<br />

consume energy quite sustainably.<br />

Following the energy models set out<br />

by Morgan, Girmai, and Hernández,<br />

energy justice can be achieved by their<br />

using even more. It is the over- and abusive<br />

consumption of the biggest users—<br />

primarily industrial users and the wealthiest<br />

people in North America and the<br />

EU—that are the core of the problem.<br />

Hernandez cites Oxfam’s findings that if<br />

the richest 10% of the global population<br />

continues its current energy consumption<br />

and the entire rest of the world’s emissions<br />

dropped to zero tomorrow, we’d<br />

still deplete our carbon budget within<br />

just a few years.<br />

“The alternative to climate crisis are<br />

already here,” Hernández stresses.<br />

“It’s found at the intersection of global<br />

movements of organized women<br />

dismantling oppressive structures with<br />

Indigenous cultures in defense of life.”<br />

It’s Not Rocket Science<br />

For Chief Shirell Parfait-Dardar of the<br />

Grand Caillou/Dulac Band of Biloxi-<br />

Chitimacha-Choctaw, the discussion of<br />

sustainable solutions to the climate crisis<br />

is one of survival.<br />

Last year, we stood at her father’s<br />

grave in Dulac, Louisiana. Parfait-<br />

Dardar was making plans for when the<br />

waters come and wash away his body,<br />

that of the grandmother who raised her<br />

and the great grandfather who served<br />

as Chief before her. Pain gripped at<br />

Parfait-Dardar’s face as she explained<br />

that if the encroaching waters of the<br />

Gulf of Mexico cannot be slowed, in a<br />

decade not only will her loved-ones and<br />

their cemetery be long-gone, but her<br />

<strong>Climate</strong> Resources<br />

350.org<br />

www.350.org<br />

Advocates 4 Earth Zimbabwe<br />

www.advocates4earth.org<br />

Acción Ecológica<br />

www.accionecologica.org<br />

Amazon Watch<br />

www.amazonwatch.org<br />

Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance<br />

www.beyondoilandgasalliance.com<br />

<strong>Climate</strong> Action Network<br />

www.climatenetwork.org<br />

Deep South Center for Environmental<br />

Justice<br />

www.dscej.org<br />

Earth Justice<br />

www.earthjustice.org<br />

EarthRights International<br />

www.earthrights.org<br />

Extinction Rebellion<br />

www.rebellion.global<br />

Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty<br />

www.fossilfueltreaty.org<br />

Futuros Indígenas<br />

www.futurosindigenas.org<br />

Indigenous <strong>Climate</strong> Action<br />

www.indigenousclimateaction.com<br />

Indigenous Environmental Network<br />

www.ienearth.org<br />

Initiative for Energy Justice<br />

www.iejusa.org<br />

Friends of the Earth International<br />

www.foei.org<br />

Fridays for the Future<br />

www.fridaysforfuture.org<br />

entire tribe may be forced to abandon<br />

its ancestral lands.<br />

Her resolve intensifies, however, as<br />

she discusses both culprits and solutions.<br />

“Look around you,” she says<br />

eyeing the skeletal remains of dead<br />

cypress and oak trees marking the<br />

landscape, a result of saltwater intrusion<br />

brought about by the dredging of<br />

canals for the fossil fuel industry, she<br />

explains. “Extraction means death.”<br />

Greater Birmingham Alliance to Stop<br />

Pollution (GASP)<br />

www.gaspgroup.org<br />

Greenpeace<br />

www.greenpeace.orginternational<br />

Hip Hop Caucus<br />

www.hiphopcaucus.org<br />

LDC Watch International<br />

www.ldcwatch.org<br />

Movement Generation<br />

www.movementgeneration.org<br />

Movement Rights<br />

www.movementrights.org<br />

Oil Change International<br />

www.priceofoil.org<br />

Pachamama Alliance<br />

www.pachamama.org<br />

PanAfrican <strong>Climate</strong> Justice Alliance<br />

www.pacja.org<br />

Red, Black, and Green New Deal<br />

www.redblackgreennewdeal.org<br />

Southeast <strong>Climate</strong> and Action<br />

Network<br />

www.scen-us.org<br />

StandEarth<br />

www.stand.earth<br />

Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI)<br />

www.sei.org<br />

Sunrise Movement<br />

www.sunrisemovement.org<br />

Uproot Project<br />

www.uprootproject.org<br />

Women’s Earth and <strong>Climate</strong> Action<br />

Network (WECAN)<br />

www.wecaninternational.org<br />

Chief Parfait-Dardar knows the solution.<br />

She wants to see an end to the fossil<br />

fuel industry, and she’s got a plan to do<br />

it: replace fossil fuels with green energy<br />

and clean jobs. She wants job training,<br />

transition assistance, and programs to get<br />

information to her tribe about how and<br />

where to find jobs. She wants the federal<br />

governments assistance to do it.<br />

“It’s not rocket science,” she says.<br />

“It’s just the will to do it.”<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 41

<strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD HONORABLE MENTION WINNER<br />

Carolyn Monastra<br />

Collecting and cleaning plastic<br />

bags by the Nairobi River,<br />

Kenya. This woman regularly<br />

collects discarded plastic bags<br />

around her community near<br />

the Nairobi River. After cleaning<br />

them, she sells the bags to<br />

brokers who then sell them to<br />

artisans who upcycle the bags<br />

by crocheting products such as<br />

handbags and hats. Since plastic<br />

bags are made from petroleum,<br />

this woman is not only reducing<br />

her community’s carbon footprint<br />

by reusing existing bags, but she<br />

is also cleaning up her neighborhood<br />

and creating income for<br />

herself and a chain of others.<br />

42 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

Witness Tree: <strong>Climate</strong> Solutions from Around the World<br />

Kenya, Tonga, Thailand, Argentina, United Kingdom, United States<br />

The Witness Tree documents<br />

the impacts of climate<br />

change around the world.<br />

From the melting ice of<br />

Antarctica to the wildfires of<br />

Australia, I am drawn to precious<br />

and precarious places that mark<br />

the shifting boundaries between<br />

nature and the effects of our<br />

not-so-natural disasters. I have<br />

photographed the climate crisis on<br />

every continent. These photographs<br />

are from the “Solutions”<br />

chapter which features seemingly<br />

small measures taken by individuals<br />

bettering their communities<br />

to larger mitigating solutions like<br />

London’s Thames Barrier.<br />

Although significant carbon<br />

reduction is primarily the<br />

responsibility of governments<br />

and industry, I believe, as these<br />

images attest, that the actions of<br />

individuals can give us hope.<br />

Top: Watering crops, Eco Yoga Park,<br />

General Rodriguez, Argentina. The<br />

Eco Yoga Park, an hour outside Buenos<br />

Aires, doubles as an organic farm.<br />

Volunteers like Larissa from Stuttgart,<br />

Germany, not only get to stretch their<br />

bodies with daily yoga classes, but also<br />

learn about permaculture as they help<br />

grow 80-90 percent of the food that is<br />

consumed there.<br />

Bottom: Village Chief Samorn<br />

Khengsamut, Khun Samut Chin, Thailand.<br />

Chief Khengsamut gives presentations<br />

to tourists who visit their village<br />

to educate them about the impacts of<br />

sea level rise and the resulting erosion<br />

of their land. Rising seas have forced<br />

villagers to move their homes further<br />

inland four or five times in the last few<br />

decades, but now they are running out<br />

of space to move.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 43

<strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD HONORABLE MENTION WINNER<br />

Roberto Nistri<br />

Burkina Faso: The Power of Resilience<br />

44 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

As part of the "Terre Verte" project to combat<br />

desertification, selected seeds are used to withstand<br />

conditions of water scarcity.<br />

In Burkina Faso, an African<br />

country considered one of<br />

the poorest on the planet,<br />

desertification, amplified<br />

by global climate change, has<br />

made entire districts unusable for<br />

agriculture, forcing those who live<br />

there to migrate to neighboring<br />

states or to Europe.<br />

Some projects implemented<br />

by international and local NGOs<br />

such as Terre Verte encourage and<br />

support traditional farming techniques.<br />

By applying a principle of<br />

“resilience” to these disastrous<br />

changes in the environment,<br />

numerous projects aim to make<br />

the desertified areas fertile, allowing<br />

local communities to cultivate<br />

them again trying to limit the<br />

phenomenon of “environmental<br />

migration.”<br />

In other areas of the country,<br />

climate change has made the<br />

duration and intensity of precipitation<br />

unpredictable, making it often<br />

disastrous for subsistence farming.<br />

The radical change in the landscape,<br />

its flora, and the drought<br />

in some areas now become<br />

chronic, have erased the great<br />

African fauna in most of Burkina<br />

Faso’s territory.<br />

Top: Project “Terre Verte.” Once grown,<br />

the plants continue to be watered individually<br />

until the development of their<br />

root system.<br />

Bottom: Floods,in Burkina Faso due<br />

to the climate change taking place in<br />

the country, occur more and more frequently<br />

even outside the canonical rainy<br />

season. They block the life of cities,<br />

including schools, for days. They can<br />

destroy also an entire crop or, in cities,<br />

tear down homes and small businesses.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 45

<strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD HONORABLE MENTION WINNER<br />

Lauren Owens Lambert<br />

Saving the Stranded<br />

46 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

Subscribe to <strong>ZEKE</strong> today and<br />

receive print edition. Learn more » »<br />

At Padre Island National Seashore in Corpus Christi, Texas, a volunteer<br />

carries an endangered Kemp’s ridley to the warm waters of the<br />

Gulf of Mexico for release after months of rehabilitation from almost<br />

freezing to death on the shores of Cape Cod, Massachusetts.<br />

Five vans, one plane, two<br />

states, one thousand<br />

miles, four organizations,<br />

two hundred people and<br />

one… banana box. On average<br />

this is what it takes to save one<br />

little life—a Kemp’s ridley sea turtle.<br />

As the most endangered and<br />

smallest sea turtle in the world,<br />

it’s worth every effort. Without<br />

this monumental conservation<br />

collaboration across the eastern<br />

seaboard of North America, this<br />

turtle might have gone extinct.<br />

In summer, the waters off Cape<br />

Cod are warm, calm, and full of<br />

food, serving as a natural nursery<br />

for young Kemp’s ridleys. But as<br />

water temperatures plummet in<br />

winter, the turtles must migrate<br />

or perish. Many lose their way<br />

and wash up, cold-stunned, on<br />

the beaches. The phenomenon<br />

is the largest recurring sea turtle<br />

stranding event in the world.<br />

Volunteers and biologists from the<br />

Massachusetts Audubon Society<br />

and the New England Aquarium<br />

are rescuing, rehabilitating, and<br />

flying the turtles to be released in<br />

warmer waters.<br />

Top: Boxes of cold-stunned sea turtles<br />

sit in a cool room at Mass Audubon<br />

in Wellfleet, Cape Cod after being<br />

processed.<br />

Bottom: Hannah Crawford (left) and<br />

Jessica Cramp (right), both interns with<br />

the New England Aquarium, hold a<br />

cold-stunned Kemp’s ridley sea turtle<br />

up to photograph the condition of their<br />

underside for record keeping and care<br />

monitoring.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 47

<strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD HONORABLE MENTION WINNER<br />

Mark Phillips<br />

Unbroken: Repair is Essential<br />

The anatomy of a mobile phone.<br />

Weighing around 160 grams,<br />

smart phones are made up of<br />

approximately 30 elements,<br />

including copper, gold and<br />

silver for wiring, and lithium and<br />

cobalt in the battery. The touch<br />

screen and display use indium,<br />

boron and rhodium. The circuits<br />

and chip use silicon, bismuth,<br />

gallium and gold. The camera<br />

and microphone use rare earths<br />

including neodymium, dyprosium<br />

and praesodymium. The vibration<br />

motors use tungsten and micro<br />

capacitors use tantalum.<br />

A complex mixture that has to<br />

be extracted from the earth and<br />

processed to make the materials,<br />

before being made into components,<br />

and sub-assemblies that<br />

are assembled into your phone,<br />

packaged, transported across the<br />

globe, and then sold.<br />

48 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

We now create nearly 55<br />

million tons of electronic<br />

waste each year—our<br />

fastest growing waste<br />

stream. When we no longer want our<br />

electronic devices, or if we break them,<br />

the resulting waste creates tremendous<br />

environmental problems. Even bigger is<br />

the impact of the materials extraction to<br />

make all these electronic devices in the<br />

first place. More than 80% of electronics<br />

waste is not recycled properly; we do not<br />

even know where most of it ends up.<br />

Recycling only recovers a fraction of the<br />

resources consumed and can potentially<br />

create even more toxic waste. One solution<br />

is to make our products last longer,<br />

through repair, reuse, and refurbishment.<br />

This requires systemic change—in<br />

policy, capabilities, and culture—and<br />

has the potential to make a substantial<br />

positive impact in the consumption and<br />

waste of resources and the environmental<br />

damage caused by both.<br />

Top: Scavenged washing machine pumps at the<br />

Kierratysekskus (reuse) facility in Helsinki, Norway.<br />

The pumps will be used for future repairs.<br />

Access to economic spares is a major challenge<br />

for repair.<br />

Bottom: Electronics repair department at the Kierratysekskus<br />

(reuse) facility in Helsinki, Norway.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 49

<strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD HONORABLE MENTION WINNER<br />

Chris Trinh<br />

Black Snake Killers<br />

Kiley Knowles rides her horse through the Shell River in northern Minnesota<br />

during a "Women Water Protectors" demonstration against Line 3. According<br />

to a 2021 report from Indigenous Environmental Network and Oil Change<br />

International, Indigenous resistance against fossil fuel infrastructure projects<br />

over the last decade has stopped or delayed greenhouse gas pollution<br />

equivalent to at least one-quarter of annual U.S. and Canadian emissions<br />

(1.8 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide). July 15, 2021.<br />

50 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

Black Snake Killers documents<br />

the Anishinaabeled<br />

struggle against<br />

the Line 3 tar sands oil<br />

pipeline—referred to by activists<br />

as the Black Snake—during the<br />

final three months of Line 3’s<br />

construction. Line 3 was built by<br />

Enbridge, a Canadian pipeline<br />

giant, to carry over 800,000<br />

barrels of crude oil daily from<br />

Alberta, Canada, to a port in<br />

Superior, Wisconsin, USA. Along<br />

the way it crosses wide swaths<br />

of Anishinaabe territory, where<br />

treaty rights grant Indigenous residents<br />

the ability to live, hunt, fish<br />

and gather. For almost a decade,<br />

Anishinaabe land defenders have<br />

fought Line 3, which has a carbon<br />

footprint equivalent to 50 coalfired<br />

power plants, in addition to<br />

the greenhouse gas emissions of<br />

the tar sands transported by the<br />

pipeline. The Anishinaabe and<br />

many Indigenous environmental<br />

activists worldwide argue that<br />

restoring land to Indigenous<br />

stewardship—and keeping it out of<br />

the hands of fossil fuel companies—is<br />

a key means of preserving<br />

biodiversity and protecting our<br />

planet.<br />

Top: Alex Golden Wolf (center), a twospirit<br />

water protector from White Earth,<br />

is violently arrested while in ceremony,<br />

as part of a peaceful blockade of an<br />

Enbridge drilling site. During the arrest,<br />

law enforcement ripped open Alex's<br />

shirt, threw them to the ground, stepped<br />

on religious artifacts and held arrestees<br />

in a closed vehicle in almost 90°F<br />

temperatures. July 23, 2021.<br />

Bottom: Tasha Martineau (Fond du Lac)<br />

stands in the Shell River, at a site where<br />

Enbridge has drilled under the water in<br />

order to lay pipe. Taysha is the founder<br />

of Camp Migizi, one of the protest<br />

camps along the Line 3 pipeline route.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 51

Interview<br />

KILIII YUYAN<br />

Kiliii Yuyan is a photographer whose practice<br />

illuminates the stories of the Arctic and human<br />

communities connected to the land. Informed<br />

by ancestry that is both Nanai/Hèzhé (East<br />

Asian Indigenous) and Chinese American, he has<br />

traveled across the polar regions working with<br />

Indigenous cultures and wildlife. On assignment,<br />

he has fled collapsing sea ice, chased fin whales in<br />

Greenland, and found kinship at the edges of the<br />

world. For National Geographic, Kiliii has produced<br />

seven stories with a focus on the Arctic. He is currently<br />

at work on a project covering Indigenous-led<br />

conservation in Ecuador, Australia and Greenland.<br />

Kiliii is also an award-winning contributor to<br />

Vogue, Bloomberg Businessweek, The Guardian,<br />

and the Nature Conservancy.<br />

By Caterina Clerici<br />

Caterina Clerici: Can you tell us about<br />

your background and how you got<br />

started in photography?<br />

Kiliii Yuyan: Well, I’m a late bloomer in<br />

photography. I didn’t really pick up the<br />

camera seriously until I was in my early<br />

or mid-thirties, and I’m 43 now. I was<br />

a traditional kayak builder. I built my<br />

culture’s kayaks and also the modernized<br />

version of them, and that was my<br />

living for about 20 years. But I did go to<br />

school for industrial design, so I think that<br />

informed both the kayak building and the<br />

photography.<br />

I was leading a lot of kayak expeditions<br />

in the North, off of Vancouver island,<br />

and there were some beaches we would<br />

go to where we’d be the only people<br />

who’d have set foot on them in the past<br />

year — really beautiful, remote places<br />

Seven-year old Steven Reich examines his father's umiaq, or skinboat, used for whaling. His father Qallu, captain<br />

of Yugu crew, expresses nervous excitement to bring Steven out whaling on the ice for the first time: "I am proud<br />

of my son; he's here to learn to be a hunter." Despite the enthusiasm, Qallu is anxious about safely reading the<br />

changing conditions of the ice. Photo by Kiliii Yuyan.<br />

that only kayaks could access. We were<br />

doing a lot of foraging off the land and<br />

fishing, and I found that when I had a<br />

camera with me and took pictures, when<br />

I sent these back to friends and family the<br />

response was a lot greater than it was<br />

without it. I started to really just fall in love<br />

with making pictures, and I remember just<br />

the power of sharing — people loved the<br />

pictures from these places and all the fairly<br />

unusual stuff that we were up to. I think<br />

that’s what got me excited about it.<br />

It was one of the only ways I had to<br />

describe my relationship with the land.<br />

A lot of Indigenous people say that “if<br />

you’re from a fish people — which we<br />

are — you’ve got to have your hands in<br />

the water,” handling the salmon, catching<br />

the fish and just being part of it. It’s really<br />

easy for me to connect with the land, but<br />

for people that weren’t part of the trips<br />

I was on, that was my way to get their<br />

hands in the water, for them to have a<br />

relationship not just with the place, but<br />

also with what we were doing.<br />

CC: How did your surroundings growing<br />

up and your ancestry, which is both<br />

Nanai/Hèzhé (East Asian Indigenous)<br />

and Chinese American, influence your<br />

approach to life as an explorer?<br />

KY: I grew up in Northeastern China,<br />

Southern Siberia, and moved to the U.S.<br />

by the time I was seven. I still attribute my<br />

love of the outdoors partially to that time,<br />

and then also to my grandma, cause she<br />

told me lots of stories about our culture.<br />

All of those stories involved, you know,<br />

ripping around on the back of an orca,<br />

riding sturgeons in the river, avoiding “the<br />

charms of seal women” and things like<br />

that. These are really great folk tales that a<br />

lot of modern Indigenous peoples don’t tell<br />

in the way of mythological tales anymore,<br />

but I come from a part of the world where<br />

that mythology is still really important. We<br />

have a deep storytelling tradition.<br />

I was always really fascinated by all<br />

that stuff. By the time I was a teenager, I<br />

was dying to go out and fish, hunt and<br />

do all those kinds of things. That deepened<br />

my relationship with the land, and<br />

also took me back to my ancestry — even<br />

though I don’t think I understood it yet at<br />

the time. But there are definitely things I<br />

have done in my life that are almost like a<br />

replay of the stories that my grandmother<br />

told me. When I was leading the kayak<br />

trips, anytime we would go out and there<br />

was any sighting of orcas, I would sing<br />

to them. That’s in our culture, that’s in<br />

our stories. We sing to orcas because<br />

they are our relatives. We sing to seals<br />

because we want to lure them up to the<br />

surface so that we can hunt them.<br />

CC: Do you see your photographic practice<br />

as a continuation of your culture’s<br />

storytelling tradition?<br />

52 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

There are absolutely times when there’s<br />

a very deliberate move towards that. A lot<br />

of my favorite images from past projects<br />

that I’ve done and increasingly a lot of<br />

the projects that I’m embarking on are<br />

not pure photojournalism, but a little more<br />

lyrical and abstract in form. I am very<br />

drawn to these kinds of stories that have a<br />

mythological bent to them. There’s a story<br />

coming out soon on what we call “thin<br />

places,” essentially pieces of the land or<br />

landscapes or spaces that exist in nature<br />

where you walk out and you feel the presence<br />

of something other than you, but not<br />

other humans. The place feels really alive.<br />

Different religions call it different<br />

things, but everyone has this experience:<br />

you completely forget you’re you and<br />

become a part of this universe existing<br />

outside, and you don’t know why, but<br />

there’s something that feels really dark<br />

and evil and terrible about it. I photograph<br />

those places because I’m interested<br />

in the cosmology of my people and lots<br />

of other Indigenous peoples, but also in<br />

that universal feeling of “I’m not going<br />

back there because it’s dark and there’s<br />

something wrong with that place.” It’s still<br />

documentary, there’s no manipulation of<br />

anything but, at the same time, the point<br />

that I’m trying to get across is much more<br />

mythical and lyrical.<br />

CC: How do you approach photographing<br />

communities different from your own,<br />

and what do you think is the value of having<br />

an insider’s perspective in a culture<br />

that has often been misrepresented?<br />

and it can be really difficult. The easiest<br />

way to get around some of these issues<br />

is just to not be interested in the same<br />

stories that everyone else is interested<br />

in, which generally I’m not, as a Native<br />

person. For example, when I did my<br />

story on whaling in Alaska among the<br />

Iñupiaq, my thought wasn’t “Oh look at<br />

these people killing whales, how exotic<br />

and strange, why are they allowed to do<br />

it?” but more like “How is it done?” I’m a<br />

kayak builder, they’re skin boat builders.<br />

The original reason I went up there in<br />

the first place was to connect about our<br />

traditional boats.<br />

But as soon as I went there, the first<br />

thing I recognized almost immediately<br />

was that the story, the real story, was not<br />

about the killing of the whale. The real<br />

story is about the relationship between<br />

the people and the community and the<br />

whales, you know, and not the throwing<br />

of the harpoon into the whale. I have a<br />

great shot of the harpoon thrown into a<br />

whale, but I rarely run it, it’s never been<br />

published. That’s not what whaling is.<br />

Whaling is community, it’s the gift of this<br />

massive creature to feed these people.<br />

CC: What is your main audience and<br />

what is your message to them?<br />

KY: For me, the most important audience<br />

is the youth of the culture that I’m<br />

photographing, and the message is just<br />

representation. They get a chance to see<br />

their uncles and aunts inside the pages<br />

of National Geographic, and that makes<br />

them a rock star. It gives them the ability<br />

to see someone who looks like them<br />

accepted with validity and celebration<br />

in the world, and that’s a really fantastic<br />

thing. And it’s also my hope that I’m<br />

able to show their own people and their<br />

culture in a way that feels very familiar<br />

to them. We’ve had the same viewpoint<br />

from the outside looking in for so long<br />

that it’s really nice to be able to go the<br />

other way around.<br />

CC: How much has climate change influenced<br />

your work, both in terms of stories<br />

and in your day-to-day practice?<br />

KY: Well, climate change is an interesting<br />

one because, first of all, in the North,<br />

every story is a climate change story.<br />

Second, it’s inescapable. It’s everywhere.<br />

Flooding ice cellars, polar bears coming<br />

to attack us because they’re starving to<br />

death, stuff like that. Sometimes I wish<br />

I had someone there to document the<br />

behind the scenes of our shoots because,<br />

in some ways, climate change is a lot<br />

more obvious in the kinds of challenges I<br />

face during my shoots than in the stories I<br />

shoot. It’s not that in the stories I shoot the<br />

effects are more subtle, but they require a<br />

lot more knowledge of the way that sea<br />

ice and things normally are. You need<br />

to know what the baseline is, in order to<br />

recognize what’s different.<br />

KY: All documentarians are interpreters<br />

and ambassadors between worlds.<br />

I understand the massive cultural differences<br />

between people, enough to know<br />

that almost every Indigenous culture has<br />

a different sense of freedoms. Whenever<br />

you interact with another culture, there’s a<br />

certain protocol that you have to abide by<br />

— can I photograph this ceremony or that,<br />

is it inappropriate to ask about certain<br />

things, or to portray people in a certain<br />

way? These are all things that are really<br />

important and you can’t assume anything.<br />

Usually the most dangerous mistakes<br />

have to do with stereotypical representations,<br />

or things that people have just<br />

gotten oppressed and repressed for over<br />

a long period of time. So there are things<br />

that our people are really sensitive about,<br />

A bowhead whale harvested by Iñupiat finally rests on a thick section of sea ice after being slowly pulled out of<br />

the water for the past eight hours. Photo by Kiliii Yuyan.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 53

DISPATCHES FROM<br />

UKRAINE<br />

Maranie Staab, a regular contributor to SDN<br />

and <strong>ZEKE</strong>, and last featured for her photos<br />

from the January 6 insurrection at the U.S.<br />

Capitol, is now reporting from Chisinau,<br />

Moldova and nearby towns in Ukraine<br />

documenting the largest refugee migration in<br />

Europe since WWII.<br />

Above: A group of Ukrainians eat a dinner<br />

prepared by World Central Kitchen partner<br />

Cafeneaua din Gratiesti while staying at Biserica<br />

Isus Salvatorul, a church in Chisinau, Moldova<br />

hosting approximately 50 Ukrainian refugees.<br />

Top Right: “Right before this happened I was shopping<br />

for my prom dress; it’s my final year of school<br />

and life was good, life felt normal. Now I’m on<br />

a bus talking to you with only this small bag and<br />

we’re running away—we left everything behind.”<br />

Alioa, 17, fled Mykolaiv, Ukraine with her<br />

three siblings and mother. They are among the<br />

now 2.3 million people who have left Ukraine in<br />

just the past two weeks, a number expected to<br />

grow as Russia continues its indiscriminate and<br />

targeted attacks on cities and civilians.<br />

Middle: Sunshine quickly turned to snow showers<br />

as hundreds of people stood at the Palanca<br />

border crossing with their suitcases and pets.<br />

Moldovans and aid organizations are working<br />

hard to provide for the ongoing flood of people<br />

fleeing Ukraine, but the need is overwhelming<br />

and expected to grow.<br />

Bottom: Leeza, age 10, offers a smile while waiting<br />

in freezing temperatures to board a bus that<br />

will evacuate her and others from the besieged<br />

city of Mykolaiv, Ukraine on March 10, <strong>2022</strong>.<br />

54 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

A Home for Global Documentary<br />

Photo by Robert Nistri from Burkina Faso: The Power of Resilience.<br />

Social Documentary Network<br />

Lori Grinker<br />

SDN Website: A web portal for<br />

documentary photographers to<br />

create online galleries and make<br />

them available to anyone with an<br />

internet connection. Since 2008,<br />

we have presented more than<br />

4,000 documentary stories from<br />

all parts of the world.<br />

www.socialdocumentary.net<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong>: This bi-annual<br />

publication allows us to present<br />

visual stories in print form with indepth<br />

writing about the themes<br />

of the photography projects.<br />

www.zekemagazine.com<br />

SDN Salon: An informal gathering<br />

of SDN photographers to<br />

share and discuss work online.<br />

Documentary Matters:<br />

A place for photographers to<br />

meet with others involved with<br />

or interested in documentary<br />

photography and discuss ongoing<br />

or completed projects.<br />

SDN Education: Leading<br />

documentary photographers and<br />

educators provide online learning<br />

opportunities for photographers<br />

interested in advancing their<br />

knowledge and skills in the field<br />

of documentary photography.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> Award for Documentary<br />

Photography: A award<br />

program juried by a distinguished<br />