ZEKE Magazine: Spring 2022 Preview

Indigenous Fire by Kiliii Yuyan The Indigenous Peoples' Burn Network is training others in an ancient technique of ecological restoration, which is to safely light low-intensity fires in wet seasons that remove the small fuels on the forest floor. Nemo's Garden by Giacomo d'Orlando Nemo’s Garden—the world’s first underwater greenhouses of terrestrial plants—represents an alternative farming system dedicated to those areas where environmental conditions make the growth of plants almost impossible. Permagarden Refugees by Sarah Fretwell The Palabek refugee settlement in Northern Uganda, with the staff of African Women Rising’s (AWR) Permagarden Program, works with refugees to utilize the existing resources—seeds, rainfall, limited land, and “waste”—and together build an agriculture system designed to help the environment regenerate and get stronger as it matures. Sustainable Solutions to the Climate Crisis by Antonia Juhasz Interview with Kiliii Yuyan by Caterina Clerici Dispatches from Ukraine by Maranie Staab Book Reviews Edited by Michelle Bogre

Indigenous Fire by Kiliii Yuyan

The Indigenous Peoples' Burn Network is training others in an ancient technique of ecological restoration, which is to safely light low-intensity fires in wet seasons that remove the small fuels on the forest floor.

Nemo's Garden by Giacomo d'Orlando

Nemo’s Garden—the world’s first underwater greenhouses of terrestrial plants—represents an alternative farming system dedicated to those areas where environmental conditions make the growth of plants almost impossible.

Permagarden Refugees

by Sarah Fretwell

The Palabek refugee settlement in Northern Uganda, with the staff of African Women Rising’s (AWR) Permagarden Program, works with refugees to utilize the existing resources—seeds, rainfall, limited land, and “waste”—and together build an agriculture system designed to help the environment regenerate and get stronger as it matures.

Sustainable Solutions to the Climate Crisis

by Antonia Juhasz

Interview with Kiliii Yuyan by Caterina Clerici

Dispatches from Ukraine by Maranie Staab

Book Reviews Edited by Michelle Bogre

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

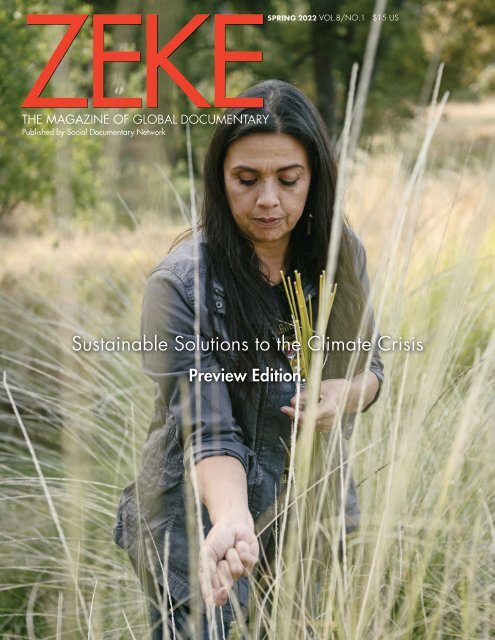

<strong>ZEKE</strong>SPRING <strong>2022</strong> VOL.8/NO.1 $15 US<br />

THE MAGAZINE OF GLOBAL DOCUMENTARY<br />

Published by Social Documentary Network<br />

Sustainable Solutions to the Climate Crisis<br />

<strong>Preview</strong> Edition.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 1

<strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD FOR SYSTEMIC CHANGE<br />

FIRST-PLACE WINNER<br />

Indigenous Fire<br />

Photos by<br />

Kiliii Yuyan<br />

United States<br />

Despite the intense focus on apocalyptic<br />

wildfires raging across the<br />

American West, scant attention<br />

is paid to solutions to climate<br />

change-exacerbated wildfire. One<br />

in particular–fire-lighting rather<br />

than fire-fighting–has proven to be an<br />

exceptional weapon against a seemingly<br />

impossible opponent on a landscape-level<br />

scale. It’s known as cultural fire. People<br />

like Margo Robbins and Elizabeth Azzuz<br />

of the Indigenous Peoples’ Burn Network<br />

are training others in an ancient technique<br />

of ecological restoration, which is to safely<br />

light low-intensity fires in wet seasons that<br />

remove the small fuels on the forest floor.<br />

Not only does it effectively prevent wildfires<br />

from spreading, but it also performs a<br />

13,000-year-old function—the restoration of<br />

health of the forests of Northern California,<br />

the most diverse coniferous forests on earth.<br />

Kiliii Yuyan illuminates stories of the Arctic<br />

and human communities connected to the<br />

land and sea. Informed by ancestry that is<br />

both Nanai/Hèzhé (East Asian Indigenous)<br />

and Chinese American, he explores the<br />

human relationship to the natural world from<br />

different cultural perspectives and extreme<br />

environments, on land and underwater. Kiliii<br />

is an award-winning contributor to National<br />

Geographic, TIME, and other major publications.<br />

Kiliii is one of PDN’s 30 Photographers<br />

(2019), a National Geographic<br />

Explorer, and a member of Indigenous<br />

Photograph and Diversify Photo. His work<br />

has been exhibited worldwide and received<br />

some of photography’s top honors.<br />

Margo Robbins, of the Cultural Fire<br />

Management Council, leads firefighters<br />

as they light an Indigenous-prescribed<br />

burn with bundles of wormwood in<br />

ceremony, near Weitchpec, CA.<br />

2 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 3

The open view of a Yurok culturally<br />

burned area in Orleans, CA. The airy,<br />

open nature of the forest here contrasts<br />

the tight and fire-prone unburnt forest<br />

in the background. The continuation<br />

of ancient cultural burning reminds<br />

us what is possible in fire-prone<br />

California. Photo by Kiliii Yuyan.<br />

4 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 5

<strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD FOR SYSTEMIC CHANGE<br />

FIRST-PLACE WINNER<br />

Nemo’s Garden<br />

Photos by Giacomo d'Orlando<br />

Italy<br />

According to the Intergovernmental Panel<br />

on Climate Change, the desertification<br />

caused by climate change has extensively<br />

reduced agricultural productivity in many<br />

regions of the world. Current population<br />

projections predict a population of<br />

10 billion by the end of the century, creating an<br />

additional two billion mouths to feed. It is urgent,<br />

then, to find an alternative method of cultivation<br />

to ensure an ecologically sustainable future.<br />

Nemo’s Garden—the world’s first underwater<br />

greenhouses of terrestrial plants—represents an<br />

alternative farming system dedicated to those<br />

areas where environmental conditions make the<br />

growth of plants almost impossible. The microclimate<br />

and thermal conditions within the biospheres<br />

are optimal for plant growth and crop yields. The<br />

encouraging results, where more than 40 different<br />

species of plants have been successfully cultivated,<br />

give us hope that we have found a sustainable<br />

agricultural system that will help us tackle the<br />

new challenges posed by climate change.<br />

Giacomo d’Orlando is an Italian documentary<br />

photographer focused on environmental and<br />

social issues. In 2015, he moved to Nepal and<br />

then Peru to enter the world of photojournalism,<br />

working alongside local NGOs focusing on social<br />

issues. His subsequent time in Australia and New<br />

Zealand inspired him to concentrate on the environment,<br />

particularly the possible future scenarios<br />

caused by climate change. His projects have<br />

appeared in The Washington Post, Der Spiegel,<br />

Paris Match, El Pais, Geo France, De Volkskrant,<br />

D-La Repubblica and Mare Magazin, among others.<br />

Today, his work looks at how the increasing<br />

pressures brought about by climate change are<br />

reshaping the planet and how present-day society<br />

is reacting to the new challenges that will<br />

characterize our future.<br />

The dark silhouette of Gabriele<br />

Cucchia, senior engineer of the Nemo’s<br />

Garden project, seen from the seabed<br />

while carrying the upper part of the<br />

biosphere to the installation site.<br />

6 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 7

8 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

A group of divers admire the Nemo's<br />

Garden during their immersion. Since<br />

the Nemo's Garden has been created,<br />

the fish population of the area<br />

increased. In fact the Nemo's Garden<br />

structure acts as a shelter for many<br />

animals, supporting the repopulation<br />

of the surrounding area. Photo by<br />

Giacomo d'Orlando.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 9

Inside the Palabek refugee settlement in<br />

Northern Uganda, with the staff of African<br />

Women Rising’s (AWR) Permagarden<br />

Program, I witnessed how this innovative<br />

approach is disrupting the broken aid<br />

system by adapting food production to the<br />

realities of climate change, changing lives and<br />

futures in the process.<br />

AWR works with refugees to utilize the<br />

existing resources—seeds, rainfall, limited<br />

land, and “waste”—and together build<br />

an agriculture system designed to help the<br />

environment regenerate and get stronger<br />

as it matures. Within two weeks, farmers<br />

are harvesting microgreens, within a month<br />

they can start eating from their gardens, and<br />

beyond that many people are able to make<br />

money selling their vegetables. Their gardens<br />

ensure needed vitamins and that mothers can<br />

produce milk to breastfeed their babies.<br />

Radical in its simplicity and effectiveness,<br />

the success of AWR’s permagarden program<br />

has tremendous implications for refugees and<br />

humans worldwide.<br />

Journalist, climate activist, and political scientist,<br />

Sarah Fretwell, works as a multimedia<br />

storyteller. Her work focuses on the intersection<br />

of the environment, people, and business with<br />

one question: What if the new bottom line<br />

was love? Her award-winning photojournalism<br />

explores the lives of everyday people with<br />

extraordinary stories and creates the human<br />

connection that engages people on a personal<br />

level, offering individuals a voice for justice,<br />

insight for solutions, and the human connection<br />

needed for international engagement.<br />

Some of her notable work and clients include<br />

the BioCarbon Fund, United Nations, USAID,<br />

The Africa Prize for Engineering Innovation,<br />

World Bank Group, and Tara Oceans<br />

Foundation.<br />

Permagarden<br />

Refugees<br />

Photos by Sarah Fretwell<br />

Uganda<br />

10 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

Yaka Lucia, in the beginnings of her<br />

Permagarden with her baby, Rosa.<br />

Before she planted her garden, they<br />

survived on rations from the World<br />

Food Program—maize, beans, flour,<br />

oil, and salt. Eating only the food<br />

rations, her breast milk dried up, and<br />

she could not feed her baby. Once<br />

she started eating the greens from<br />

her garden, her breast milk returned<br />

within two weeks. Between her<br />

Permagarden and food rations, she<br />

can now feed all of her children for<br />

the entire month.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 11

Nina Morgan grew up in the shadow<br />

of a coal mine. The four-room shotgun<br />

home she shared with her twin brother,<br />

mother, and grandmother is in the<br />

tiny community of Sipsey, about 30<br />

miles North of Birmingham, Alabama.<br />

More precisely, they lived in the “Black<br />

Camp,” the name still used by locals<br />

over one hundred years after the<br />

DeBardeleben Coal Company built<br />

this company town, segregating workers and<br />

their families by race. Generations of Morgan’s<br />

family have worked in the mines. Back behind<br />

the house, past the old graveyard marked with<br />

stones where great grandfather Tommy who died<br />

of Black Lung is buried, she and brother Ishmael<br />

played in “the spot”—a former blasting site filled<br />

with rainwater.<br />

Today, Morgan is the Climate & Environmental<br />

Justice Organizer for<br />

Greater Birmingham<br />

Alliance to Stop<br />

Pollution, better known<br />

by the acronym,<br />

“GASP.” “Coal is killing<br />

us. It’s breaking down<br />

our bodies,” Morgan<br />

told me. She warns of<br />

a coming reckoning<br />

bringing an end to the<br />

“legacy and history of<br />

extraction, exploitation,<br />

and violent racism”<br />

that has devastated<br />

Sipsey and much of the<br />

American South.<br />

Central to her effort is shifting Alabama away<br />

from all fossil fuels, and she has no shortage<br />

of plans to accomplish this goal. “The answers<br />

Sustainable Solutions to<br />

By Antonia Juhasz<br />

12 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

the Climate Crisis<br />

Nina<br />

Morgan, not far<br />

from her grandmother's<br />

home in Sipsey, Alabama.<br />

Photograph by Andi Rice,<br />

2021.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 13

<strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD HONORABLE MENTION WINNER<br />

Roberto Nistri<br />

Burkina Faso: The Power of Resilience<br />

14 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

As part of the "Terre Verte" project to combat<br />

desertification, selected seeds are used to withstand<br />

conditions of water scarcity.<br />

In Burkina Faso, an African<br />

country considered one of<br />

the poorest on the planet,<br />

desertification, amplified<br />

by global climate change, has<br />

made entire districts unusable for<br />

agriculture, forcing those who live<br />

there to migrate to neighboring<br />

states or to Europe.<br />

Some projects implemented<br />

by international and local NGOs<br />

such as Terre Verte encourage and<br />

support traditional farming techniques.<br />

By applying a principle of<br />

“resilience” to these disastrous<br />

changes in the environment,<br />

numerous projects aim to make<br />

the desertified areas fertile, allowing<br />

local communities to cultivate<br />

them again trying to limit the<br />

phenomenon of “environmental<br />

migration.”<br />

In other areas of the country,<br />

climate change has made the<br />

duration and intensity of precipitation<br />

unpredictable, making it often<br />

disastrous for subsistence farming.<br />

The radical change in the landscape,<br />

its flora, and the drought<br />

in some areas now become<br />

chronic, have erased the great<br />

African fauna in most of Burkina<br />

Faso’s territory.<br />

Top: Project “Terre Verte.” Once grown,<br />

the plants continue to be watered individually<br />

until the development of their<br />

root system.<br />

Bottom: Floods,in Burkina Faso due<br />

to the climate change taking place in<br />

the country, occur more and more frequently<br />

even outside the canonical rainy<br />

season. They block the life of cities,<br />

including schools, for days. They can<br />

destroy also an entire crop or, in cities,<br />

tear down homes and small businesses.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 15

<strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD HONORABLE MENTION WINNER<br />

Mark Phillips<br />

Unbroken: Repair is Essential<br />

The anatomy of a mobile phone.<br />

Weighing around 160 grams,<br />

smart phones are made up of<br />

approximately 30 elements,<br />

including copper, gold and<br />

silver for wiring, and lithium and<br />

cobalt in the battery. The touch<br />

screen and display use indium,<br />

boron and rhodium. The circuits<br />

and chip use silicon, bismuth,<br />

gallium and gold. The camera<br />

and microphone use rare earths<br />

including neodymium, dyprosium<br />

and praesodymium. The vibration<br />

motors use tungsten and micro<br />

capacitors use tantalum.<br />

A complex mixture that has to<br />

be extracted from the earth and<br />

processed to make the materials,<br />

before being made into components,<br />

and sub-assemblies that<br />

are assembled into your phone,<br />

packaged, transported across the<br />

globe, and then sold.<br />

16 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

We now create nearly 55<br />

million tons of electronic<br />

waste each year—our<br />

fastest growing waste<br />

stream. When we no longer want our<br />

electronic devices, or if we break them,<br />

the resulting waste creates tremendous<br />

environmental problems. Even bigger is<br />

the impact of the materials extraction to<br />

make all these electronic devices in the<br />

first place. More than 80% of electronics<br />

waste is not recycled properly; we do not<br />

even know where most of it ends up.<br />

Recycling only recovers a fraction of the<br />

resources consumed and can potentially<br />

create even more toxic waste. One solution<br />

is to make our products last longer,<br />

through repair, reuse, and refurbishment.<br />

This requires systemic change—in<br />

policy, capabilities, and culture—and<br />

has the potential to make a substantial<br />

positive impact in the consumption and<br />

waste of resources and the environmental<br />

damage caused by both.<br />

Top: Scavenged washing machine pumps at the<br />

Kierratysekskus (reuse) facility in Helsinki, Norway.<br />

The pumps will be used for future repairs.<br />

Access to economic spares is a major challenge<br />

for repair.<br />

Bottom: Electronics repair department at the Kierratysekskus<br />

(reuse) facility in Helsinki, Norway.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 17

BOOK<br />

REVIEWS<br />

EDITOR: MICHELLE BOGRE<br />

AFTER US THE DELUGE: The<br />

Human Consequences of<br />

Rising Sea Levels<br />

Photographs by Kadir van Lohuizen<br />

Lannoo, 2021 | 288 pages | 45 Euros<br />

A newly built sea wall is not very effective. Jakarta, Indonesia.<br />

Kadir van Lohuizen’s massive<br />

new book After Us The Deluge<br />

sits on the coffee table in<br />

front of me, the title a bold, radioactive<br />

salmon tone. The cover image<br />

is a muted image of a girl treading<br />

through water suggesting the book’s<br />

content—the current and future effects<br />

of rising sea levels on seven different<br />

parts of the world. Each chapter is<br />

split into two sections: an essay by a<br />

prominent figure in the field, followed<br />

by van Lohuizen’s stark photographs of<br />

people in flooded lands, aerial images<br />

of islands, and landscapes from around<br />

the globe. Together the images and<br />

words tell the story of the effects of<br />

climate change on coasts, and cities<br />

threatened by an underwater future.<br />

This book is a call to action, but it isn’t<br />

always clear to whom it is calling out.<br />

The title of this book plays on a<br />

monarchic idea of abandon, of living<br />

in decadence and pushing the problem<br />

to another generation. But, who is the<br />

author speaking to, when he says us? The<br />

book doesn’t provide a clear answer, but<br />

it is clear who will be—and are—the first<br />

to face the consequences. In the chapter<br />

on Guna Yala (Panama), there is an<br />

image of a young girl on the beach with<br />

her hands crossed. Her body language is<br />

strong but tense, and her gaze is angry.<br />

She stands not only for her community<br />

facing the effects of climate change and<br />

rising sea levels, but also for her generation<br />

and generations to come.<br />

Perhaps us is anyone implicated in the<br />

future of the girl from Guna Yala, who<br />

benefits from a lifestyle responsible for the<br />

deluge to come. Even so, the book seems<br />

to speak to a more specific audience. The<br />

structure and tone of After Us The Deluge<br />

resemble a commission report. Saturated<br />

in technical terms and figures, the text<br />

and images provide little room to experience—to<br />

feel—the implications of climate<br />

change. Urgency is drowned by formula.<br />

Although the book is framed as an open<br />

invitation to participate in saving the<br />

world, it is evident that the photographer<br />

and essay authors speak in the language<br />

of policy makers and industrialists. A<br />

book can change the world, by imagining<br />

what it could be, but this book lacks<br />

imagination. The images are not spectacular,<br />

though they depict awful truths.<br />

They are sharp, dull, and laid out in in a<br />

utilitarian manner. They are there to play<br />

their role as documents, to relay a dangerous<br />

situation to powerful people who<br />

could potentially do something about it.<br />

The world can be seen differently, and<br />

so can books, and this book has a new<br />

world hidden inside of it. A rogue reader<br />

can read it in an imaginative way: randomly<br />

flipping the pages. A page drops.<br />

It is a picture of a man’s head sticking out<br />

of a flooded street. He seems calm, as if<br />

all of this had been anticipated. Behind<br />

him, a palm tree is suspended in the air,<br />

waiting to collapse. Is this an image from<br />

the past, or an illustration of the future?<br />

Another flip reveals a picture of a boy,<br />

draped in plastic, walking by an eroding<br />

coast, a panorama of flooded lands and<br />

heavy clouds. These random images, out<br />

of time and place, best communicate the<br />

reality of the crisis we collectively face.<br />

Flipping chaotically through the pages,<br />

Greenland becomes The Netherlands and<br />

Fiji and Miami grow interchangeable. A<br />

charge is in the air, a storm which leaves<br />

the book and enters my apartment. A<br />

drop of water falls and immediately soaks<br />

into the page. Is it my drink or is it raining<br />

here too? The water drop leaves behind a<br />

mark, the threat of a storm to come.<br />

—Dana Melaver<br />

18 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

RISING AMONG RUINS,<br />

DANCING AMID BULLETS<br />

Photographs by Maryam Ashrafi<br />

Preface by Gary Knight<br />

Hemeria, 2021 | 252 pages | 65 Euros<br />

In reading Rising Among Ruins,<br />

Dancing Amid Bullets, we need<br />

to ask ourselves what is this book<br />

about. Is it about the struggle for Kurdish<br />

autonomy in the Middle East with a<br />

focus on Kurdish women fighters or<br />

is it a book of photographs about the<br />

struggle for Kurdish autonomy in the<br />

Middle East with a focus on Kurdish<br />

women fighters? The former puts the<br />

emphasis on the primacy of the political<br />

history of the Kurds, while the latter<br />

puts the emphasis on works of art on<br />

paper that can touch us in ways that an<br />

alphabet soup of Kurdish political parties<br />

never will.<br />

Ashrafi meets us somewhere in<br />

between but leans towards the former—<br />

an extraordinarily powerful book that<br />

educates us about the complicated, divisive,<br />

violent, and sometimes inspirational<br />

recent history of the world’s largest ethnic<br />

minority without a nation. And to do so,<br />

she presents us with outstanding and<br />

important photos of her journeys through<br />

Kurdistan during the recent wars in Iraq<br />

and Syria.<br />

The book’s preface by Gary<br />

Knight—co-founder of the VII photo<br />

agency—focuses on the meaning of the<br />

photographic images and particularly<br />

the importance of Ashrafi’s images of<br />

women in conflict. Other essays are more<br />

focused on Kurdish political aspirations.<br />

But no one comments on the artfulness<br />

of Ashrafi’s images and how they can<br />

provide a deeper understanding of the<br />

drama of humanity.<br />

In 352 pages of black and white photographs<br />

and essays, we are intimately<br />

brought into the centuries-old struggle for<br />

Kurdish autonomy in the Middle East.<br />

More interestingly, Ashrafi focuses on<br />

the Women’s Protection Unit (YPJ) and<br />

their adherence to Abdullah Ocalan,<br />

the leader of the Kurdistan Worker’s<br />

Party (PKK), who has been imprisoned<br />

in Turkey since 1999. A former Marxist-<br />

Leninist, Ocalan now embraces the<br />

ideas of an obscure American anarchist,<br />

Murray Bookchin, and his theory of libertarian<br />

communalism to “build an egalitarian<br />

ecological, profoundly democratic,<br />

and tolerant society in which women can<br />

finally live in fulfillment.”<br />

At great personal risk, Ashrafi travels<br />

through the region and makes remarkable<br />

photos and portraits of Kurdish women<br />

fighters from the YPJ, soldiers from Syrian<br />

Democratic Forces (SDF), Yazidi women<br />

and children who escaped genocide on<br />

Mt. Sinjar, fighters from Free Women’s<br />

Units (YJA), Peshmerga fighters, refugees<br />

from across the region, and others.<br />

Ashrafi’s work compares to similar<br />

efforts such as Robert Capa and Gerda<br />

Taro’s documentation of the Spanish<br />

Civil War (often compared to the recent<br />

Kurdish quest for autonomy); or Susan<br />

Meiselas’s, Nicaragua, about the<br />

Sandinista revolt in 1979 against the dictatorial<br />

Somoza dynasty. The significance<br />

of the work by Capa, Taro, and Meiselas<br />

is that they are each an equal balance<br />

between the aesthetic brilliance of the<br />

images and the context of these images.<br />

In the case of Ashrafi, her work leans<br />

more towards the latter—the context.<br />

It is interesting that in an interview with<br />

Ashrafi in the book, she seems dismissive<br />

of one of her seminal photos —an<br />

extraordinary portrait of a member of the<br />

Women’s Projection Units mourning at<br />

the grave of Ageri, a martyred comrade.<br />

While Ashrafi recognizes that this photo<br />

could be iconic, she sidelines it because<br />

she cannot accept that her subject’s<br />

This Arab woman returned to Tabqa with her family<br />

after the liberation of the city. In her 40s, and a mother<br />

of 9 children, she had no choice but to live in an abandoned<br />

building with her family, as their house was<br />

destroyed during the war against ISIS.<br />

beauty may detract from the viewer’s<br />

understanding of the tragic reality of<br />

this funeral. Ashrafi cannot quite accept<br />

the magic of her own images and how<br />

powerful they can be to communicate a<br />

very human moment that transcends the<br />

complex political subtexts described by<br />

the other essayists in the book.<br />

The book presents us with a deep<br />

historical context, but again we are faced<br />

with the question: are Ashrafi’s photos<br />

illustrating these essays or are the essays<br />

providing context that the photographs<br />

just cannot provide on their own? That is<br />

the crux of the problem, but perhaps it<br />

is too much to demand from one book.<br />

In the end, these are extraordinary<br />

photographs not seen elsewhere, supported<br />

by important political history. After<br />

reading this book, you will walk away<br />

appreciating the brave accomplishments<br />

of Ashrafi, the beauty and tragedy of<br />

the Kurdish people as they continue their<br />

struggle for freedom, and the uniquely<br />

misunderstood revolutionary ideology<br />

of Bookchin, Ocalan, and the Women’s<br />

Protection Units that are transforming<br />

gender relations in a part of the world<br />

that is otherwise known for its harsh and<br />

inhumane treatment of women.<br />

—Glenn Ruga<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>/ 19

<strong>ZEKE</strong><br />

SPRING<br />

THE MAGAZINE OF GLOBAL DOCUMENTARY<br />

Published by Social Documentary Network<br />

Donors to the 2021 Annual Appeal<br />

SDN would like to thank the following donors to the 2021<br />

Annual Appeal. Support from private individuals is essential<br />

for <strong>ZEKE</strong> to continue publishing.<br />

To support SDN and all our programs, please visit<br />

www.socialdocumentary.net/cms/support<br />

Benefactor<br />

Carol Allen-Storey<br />

Barbara Ayotte<br />

Robert and Judy Ayotte<br />

Rudi Dundas<br />

Jamey Stillings<br />

Sustainer<br />

Julien Ayotte<br />

Michelle Bogre<br />

Liane Brandon<br />

Margo Cooper<br />

Greig Cranna<br />

Ivy Gordon<br />

Edin Insanic<br />

Mary Ellen Keough<br />

Thomas Kovach<br />

France Leclerc<br />

Sandra Matthews<br />

Bruce Rosen<br />

David Spink<br />

Bob & Janet Winston<br />

Supporter<br />

Anonymous (2)<br />

Cathi Baglin<br />

Diane DePaso<br />

Susi Eggenberger<br />

Kent Fairfield<br />

Connie Frisbee Houde<br />

Morrie Gasser<br />

Vivien Goldman<br />

Kamini Grover<br />

John Heymann<br />

Alma Johnson<br />

Michael Kane<br />

James Koenigsaecker<br />

Fredrick Orkin<br />

John Parisi<br />

Susan Ressler<br />

Michael Sheridan<br />

Elin <strong>Spring</strong><br />

Matthew Temple<br />

Donor<br />

Maria Daniel Balcazar<br />

Peter Barry<br />

Sheri Lynn Behr<br />

Andreas Bruehwiler<br />

Frank Coco<br />

Enos Ignacio Cozier<br />

Lisa DuBois<br />

Irene Fertik<br />

Debra Fischer Goldstein<br />

Florence Gallez<br />

Paul Gottlieb<br />

Iain Guest<br />

Robert Hansen<br />

Margaret Kauffmann<br />

Deborah Lannon<br />

William Livingston<br />

Joan Lobis Brown<br />

Jack David Marcus<br />

Coco McCabe<br />

Steven McDonald<br />

Doug Menuez<br />

Jorge Monteagudo<br />

Betty Press<br />

Skip Schiel<br />

Roberta Taman<br />

Mark Tuschman<br />

Robert Wilson<br />

Michele Zousmer<br />

<strong>2022</strong> Vol. 8/No. 1<br />

$15 US<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> is published by Social Documentary Network (SDN),<br />

a nonprofit organization promoting visual storytelling about<br />

global themes. Started as a website in 2008, today SDN<br />

works with thousands of photographers around the world to tell<br />

important stories through the visual medium of photography.<br />

Since 2008, SDN has featured more than 4,000 exhibits on its<br />

website and has had gallery exhibitions in major cities around<br />

the world. All the work featured in <strong>ZEKE</strong> first appeared on the<br />

SDN website, www.socialdocumentary.net.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong><br />

Executive Editor: Glenn Ruga<br />

Editor: Barbara Ayotte<br />

Book Review Editor: Michelle Bogre<br />

Reportage International,<br />

Inc. Board of Directors<br />

Glenn Ruga, President<br />

Eric Luden, Treasurer<br />

Barbara Ayotte, Secretary<br />

Michelle Bogre<br />

Lisa DuBois<br />

SDN and <strong>ZEKE</strong> magazine<br />

are projects of Reportage<br />

International, Inc., a nonprofit<br />

organization founded in 2020.<br />

To Subscribe:<br />

www.zekemagazine.com<br />

Advertising Inquiries:<br />

glenn@socialdocumentary.net<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> does not accept unsolicited<br />

submissions. To be considered for<br />

publication in <strong>ZEKE</strong>, submit your<br />

work to the SDN website either as<br />

a standard exhibit or a submission<br />

to a Call for Entries.<br />

61 Potter Street<br />

Concord, MA 01742 USA<br />

617-417-5981<br />

info@socialdocumentary.net<br />

www.socialdocumentary.net<br />

www.zekemagazine.com<br />

socdoctweets<br />

socialdocumentarynet<br />

SDN Advisory Committee<br />

Lori Grinker, New York, NY<br />

Independent Photographer and<br />

Educator<br />

Catherine Karnow,<br />

San Francisco, CA<br />

Independent Photographer and<br />

Educator<br />

Ed Kashi, Montclair, NJ<br />

Member of VII photo agency<br />

Photographer, Filmmaker,<br />

Educator<br />

Eric Luden, Cambridge, MA<br />

Founder/Owner<br />

Digital Silver Imaging<br />

Lekgetho Makola, Johanesburg,<br />

South Africa<br />

Head, Market Photo Workshop<br />

Molly Roberts, Washington, DC<br />

Independent Visual Storyteller and<br />

Producer<br />

Jamel Shabazz, New York, NY<br />

Independent Fine Art, Fashion and<br />

Documentary Photographer<br />

Jeffrey D. Smith, New York NY<br />

Director, Contact Press Images<br />

Jamey Stillings, Sante Fe, NM<br />

Independent Photographer<br />

Steve Walker, Danbury, CT<br />

Consultant and Educator<br />

Frank Ward, Williamsburg, MA<br />

Photographer and Educator<br />

Amy Yenkin, New York, NY<br />

Independent Producer and Editor<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> is published twice a year by<br />

Social Documentary Network<br />

Copyright © <strong>2022</strong><br />

Social Documentary Network<br />

ISSN 2381-1390<br />

socialdocumentary<br />

20 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

PROFILE<br />

Antonia Juhasz<br />

Author of "Sustainable Solutions to<br />

the Climate Crisis<br />

By Daniela Cohen<br />

New Orleans-based author and investigative<br />

journalist Antonia Juhasz aims<br />

to “move readers to see themselves as<br />

active participants in the events that<br />

shape their own and other people’s lives,”<br />

hold bad actors to account, and present<br />

solutions to pressing problems.<br />

With a focus on energy and climate, for<br />

her, reporting has been a tangible way to<br />

immediately be of service.<br />

Juhasz’s passion for this work is obvious,<br />

with early roots including time in<br />

her 20’s as a legislative assistant in the U.S.<br />

Congress, where she experienced firsthand<br />

the harmful and undue influence of certain<br />

corporations over the country’s policy<br />

process. Her determination to confront<br />

this evolved into a focus on oil companies,<br />

particularly during the Bush administration<br />

and the Iraq war. Later, she noticed how<br />

most of the reporting on the oil industry<br />

was done by finance journalists, many of<br />

whose coverage was limited by interdependent<br />

relationships with the companies they<br />

reported on and did not include investigating<br />

broader impacts on human health,<br />

environment, politics, human rights, war<br />

and peace, and climate.<br />

“I wanted to apply a holistic approach<br />

to look at fossil fuels through all of these<br />

lenses,” says Juhasz. “And in particular, the<br />

impacts on people on the ground and what<br />

their experiences were, what their stories<br />

were, what their struggles were, and to<br />

report from this full 360-degree lens.”<br />

As the climate crisis worsened, the scope<br />

of Juhasz’s reporting widened to focus on<br />

climate and energy more broadly to address<br />

the scope of both the problem and the<br />

various environmental justice movements<br />

working towards solutions.<br />

Writing “Sustainable Solutions to the<br />

Climate Crisis” provided her with a refreshing<br />

opportunity to focus fully on solutions.<br />

Although Juhasz includes the perspectives<br />

of people on the frontlines who are pushing<br />

back, in her writing there is often limited<br />

opportunity to include their solutions.<br />

“I so often feel it is important to<br />

explain and hold to account things that<br />

have gone wrong and bad actors and<br />

bad outcomes,” says Juhasz. “But it really<br />

behooves us to spend the same amount of<br />

time and attention, if not more, on all of<br />

the incredible work that people are doing,<br />

Antonia Juhasz reporting for Newsweek on local<br />

Indigenous resistance to Shell's offshore oil plans.<br />

On the tip of the Alaskan Arctic in Wainwright.<br />

Photo© 2015 Gary Braasch<br />

to put forward the solutions and actively<br />

living the solutions.”<br />

The interviewees in “Sustainable<br />

Solutions to the Climate Crisis,” women of<br />

color on the frontlines of the energy and<br />

climate crisis, were keen to focus on that.<br />

Each reiterated that they have solutions<br />

to the climate crisis, but far too often their<br />

voices are not heard, or when they are, they<br />

are not supported with funding or policy to<br />

make these changes or to keep bad actors from<br />

interfering with what they are already doing.<br />

Juhasz hopes to leave readers knowing that<br />

we have the solutions to confront the climate<br />

crisis, as well as the inspiration and resources to<br />

get involved in implementing them.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong><br />

SUBSCRIBE<br />

WWW.<strong>ZEKE</strong>MAGAZINE.COM

documentary<br />

SDNsocial<br />

network<br />

PUBLISHER OF <strong>ZEKE</strong> MAGAZINE<br />

61 Potter Street<br />

Concord, MA 01742<br />

USA<br />

The Fine Art of Printing in a Digital World<br />

Trees lie fallen into the Chesapeake Bay on Hoopers Island, Maryland. They are the victims of a warming climate and eroding coastlines<br />

that may rise by as much as 6 feet by the year 2100, swallowing nearly all of Dorchester County, Maryland’s third largest.<br />

Photo: Michael O. Snyder, michaelosnyder.com, @michaelosnyder<br />

Real Silver Gelatin Prints DIRECTLY from your Digital File<br />

DSI Digital Silver Print ® Fiber • DSI Digital Silver Print ® RC<br />

Color Pigment Prints • Complete Mounting & Matting Services • Custom Framing<br />

Digitization Services • Shipping World Wide<br />

digitalsilverimaging.com • 617 489-0035