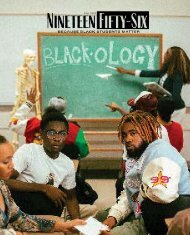

Nineteen Fifty-Six Vol. 2 No. 4, Hidden Figures

The March issue of Nineteen Fifty-Six magazine is themed "Hidden Figures" in honor of National Women's History Month, celebrating the beauty and resilience of trailblazing Black women.

The March issue of Nineteen Fifty-Six magazine is themed "Hidden Figures" in honor of National Women's History Month, celebrating the beauty and resilience of trailblazing Black women.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

HIDDEN FIGURES<br />

MARCH 2022

DEAR<br />

BLACK<br />

STUDENTS,<br />

You do matter. The numerous achievements and talents<br />

of Black students deserve to be recognized. As of Fall<br />

2021, 11.16% of students on campus identified as Black or<br />

African American. Black students are disproportionately<br />

underrepresented in various areas on campus. <strong>Nineteen</strong><br />

<strong>Fifty</strong>-<strong>Six</strong> is a Black student-led magazine that amplifies<br />

the voices within the University of Alabama’s Black<br />

community. It also seeks to educate students from all<br />

backgrounds on culturally important issues and topics<br />

in an effort to produce socially-conscious, ethical and<br />

well-rounded citizens.

EDITORIAL STAFF<br />

EDITOR IN CHIEF<br />

MANAGING EDITOR<br />

VISUALS & DESIGN EDITOR<br />

PHOTO EDITOR<br />

ENGAGEMENT EDITOR<br />

ASST. ENGAGEMENT EDITOR<br />

FEATURES & EXPERIENCES EDITOR<br />

CULTURE & LIFESTYLE DIRECTOR<br />

Tionna Taite<br />

Nickell Grant<br />

Ashton Jah<br />

Tyler Hogan<br />

Madison Davis<br />

Jolencia Jones<br />

Ashlee Woods<br />

Farrah Sanders<br />

ISSUE CONTRIBUTORS<br />

WRITERS<br />

DESIGNERS<br />

SOCIAL MEDIA & MARKETING<br />

PR SPECIALISTS<br />

Christine Thompson,<br />

Jolencia Jones<br />

Tonya Williams, Lyric<br />

Wisdom<br />

Karris Harmon, Asia<br />

Smith, Christian Thomas,<br />

Jordan Strawter<br />

Danielle S. McAllister,<br />

Farrah Sanders<br />

COPYRIGHT<br />

<strong>Nineteen</strong> <strong>Fifty</strong>-<strong>Six</strong> is published by the Office of Student Media at The University of Alabama. All content and<br />

design are produced by students in consultation with professional staff advisers. All material contained herein,<br />

except advertising or where indicated otherwise, is copyrighted © 2022 by <strong>Nineteen</strong> <strong>Fifty</strong>-<strong>Six</strong> magazine. Material<br />

herein may not be reprinted without the expressed, written permission of <strong>Nineteen</strong> <strong>Fifty</strong>-<strong>Six</strong> magazine. Editorial<br />

and Advertising offices for <strong>Nineteen</strong> <strong>Fifty</strong>-<strong>Six</strong> Magazine are located at 414 Campus Drive East, Tuscaloosa, AL<br />

35487. The mailing address is P.O. Box 870170, Tuscaloosa, AL 35487. Phone: (205) 348-7257.<br />

Cover illustration by Ashton Jah.

FROM THE EDITOR:<br />

Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson is making<br />

history as the first Black woman to be<br />

nominated to the United States Supreme<br />

Court. If she is confirmed, she will be<br />

the first Black woman to serve on the US<br />

Supreme Court and only the sixth woman in<br />

US history. As someone who aspires to make<br />

lasting change in the legal profession, I am<br />

inspired by her in more ways than one.<br />

I believe it’s important to highlight women<br />

such as Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson.<br />

Trailblazing Black women not only pave the<br />

way for young Black girls and women, but<br />

these women also serve as proof that we are<br />

capable of accomplishing whatever we set<br />

our minds to.<br />

“<br />

There are also women I have<br />

never met but who are recorded<br />

in the pages of history and whose<br />

lives and struggles inspire me<br />

and thousands of other working<br />

women to keep putting one foot<br />

in front of another every day.<br />

”<br />

- Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson<br />

Often, Black women are not properly given<br />

their flowers for the outstanding work<br />

that they have done. Black women have<br />

become used to being overlooked and<br />

underappreciated. However, that should not<br />

be the case. I challenge you to recognize<br />

and educate yourselves on the contributions<br />

of Black women at your university, in your<br />

career field, and other aspects of your life.<br />

Truly, you will realize that many Black<br />

women are ‘hidden figures’ deserving of<br />

recognition.<br />

I am delighted to present the March<br />

2022 issue of <strong>Nineteen</strong> <strong>Fifty</strong>-<strong>Six</strong> in honor<br />

of Women’s History Month. I hope this<br />

magazine issue inspires you and educates<br />

you about the beauty and resilience of<br />

trailblazing Black women.<br />

TIONNA TAITE, EDITOR IN CHIEF<br />

4

TABLE OF<br />

TRAILBLAZING BLACK WOMEN OF UA 7<br />

THE DEVIL’S PUNCHBOWL 9<br />

A Q&A WITH COACH JANESE CONSTANTINE 11<br />

ACTIVISM REDEFINED: A PERSONAL NARRATIVE 15<br />

A LETTER OF ADVICE FROM JASMINE HOLLIE 17<br />

SEE MORE OF NINETEEN FIFTY-SIX MAGAZINE<br />

1956magazine.ua.edu<br />

1956magazine<br />

1956magazine<br />

1956magazine

JOLENCIA JONES<br />

TRAILBLAZING<br />

BLACK<br />

WOMEN<br />

OF UA<br />

7<br />

Throughout history, Black women are often<br />

overlooked and undervalued despite their<br />

education, status or contributions. The following<br />

examples are some trailblazing Black women who have<br />

set the standards and paved the way at the University of<br />

Alabama.<br />

“<strong>No</strong>t enough Black students know about great Black<br />

women who have come and done amazing things in<br />

their lives. They are never talked about, and other young<br />

Black women need to know that greatness can come from<br />

anywhere. We need that spark of inspiration and drive<br />

that says we are more than just our stereotypes,” said<br />

Pearl Hargray, a junior majoring in accounting.<br />

In 1965, Vivian Malone Jones became the first Black<br />

graduate from the university. Her enrollment with<br />

the university resulted in the infamous stand in the<br />

schoolhouse door from George Wallace. After receiving<br />

her degree she moved to Washington D.C. and joined the<br />

civil rights division of the U.S. Department of Justice<br />

where she worked as a research analyst. In 1977, she<br />

became the executive director of the Voter Education<br />

Project. In 2000, she received the honorary Doctor of<br />

Humane Letters from UA.<br />

Dianne Kirksey-Floyd was an actress, playwright, director<br />

and pioneer that enrolled in 1967. During her time oncampus<br />

she created a legacy that follows her today.<br />

She founded the Black Student Union at UA. She was<br />

the first Black Bama Belle and the first Black woman to<br />

appear on the homecoming court. She was also the first<br />

Black woman to be an officer of the Associated Women’s<br />

Students organization.<br />

Lena Prewitt became the first Black professor at the<br />

university in 1970 for the Culverhouse College of Business<br />

before her retirement. She is also responsible for being<br />

the only Black person to work with Wernher von Braun at<br />

NASA for the Saturn V project.<br />

Laci Jordan graduated from the university with two<br />

degrees, one in criminal justice and the other in design.<br />

She has had her art commissioned by various brands such<br />

as Disney, Nike, Ulta Beauty and New York Times to name<br />

a few.<br />

Sonequa Martin-Green is another UA alumna who<br />

received a degree in theatre. Throughout the years she<br />

has appeared in high-profile shows and movies. She has<br />

also been featured in The Walking Dead and Star Trek:<br />

The Discovery. Her appearance in Star Trek made her<br />

the first Black woman to lead the Star Trek cast. She also<br />

voiced a character for the 2021 movie, Space Jam: A New<br />

Legacy.<br />

“I’ve heard of Sonequa Martin-Green from watching<br />

The Walking Dead and the preview for Star Trek: The<br />

Discovery, but I never knew she was an alumna and I find<br />

that very sad because I admire that woman,” said Hargray.<br />

“In a predominantly white institution, it is important to<br />

not just spotlight but also acknowledge Black women’s<br />

contributions since many of us are overlooked or have to<br />

work twice as hard in these spaces. This ensures that the<br />

hard work that has been put in is appreciated,” said Jayla<br />

Carr, a junior majoring in political science.<br />

It’s important that we acknowledge these amazing Black<br />

women so other students will know the lasting impact<br />

they had on the university and in their career fields. The<br />

university uses the phrase “Where Legends are Made”<br />

and these courageous women are proof of that statement.

TIONNA TAITE<br />

THE DEVIL’S<br />

PUNCHBOWL<br />

In the foothills of Mississippi, the trees grow heavy<br />

with uneaten peaches. Tales have haunted the grounds<br />

of the Devil’s Punchbowl for decades, from pirates to<br />

planes crashing.While the lands may not be filled with<br />

treasure, they are haunted by the history of genocide,<br />

terror, and a past filled with hatred for Black Americans<br />

that cannot be ignored.<br />

The African American registry on December 13, 2020<br />

asserts the Devil’s Punchbowl massacre took place in<br />

Natchez, Mississippi in the 1860s. The camp was located<br />

at the bottom of a cavernous pit with trees located on<br />

the bluffs above, in which 20,000 formerly enslaved Black<br />

Americans were placed in a concentration camp, and later<br />

killed. Unfortunately, this story, like so many, has been<br />

drowned beneath a ravine filled with pain and suffering.<br />

The United States has a deep-rooted history of racially<br />

motivated massacres that were frequently denied and<br />

went undocumented by authorities explains USA Today<br />

on June 21, 2021. We must understand America’s history of<br />

hiding Black massacres, starting with Mississippi.<br />

We’ll uncover the Devil’s Punchbowl by examining its<br />

history, current understanding, and implications because<br />

as noted writer and activist James Baldwin said in 1963,<br />

“American history is longer, larger, more various, and<br />

more terrible than anything anyone has ever said about<br />

it.”<br />

As formerly enslaved Black Americans made their way<br />

to freedom, the town of Natchez quickly went from a<br />

small town to an overpopulated metropolis. In order to<br />

deal with the population influx, a concentration camp<br />

was established by soldiers that essentially eradicated<br />

the formerly enslaved people. The Natchez Museum of<br />

African American History and Culture on February 17,<br />

2021 explains bleak conditions of being cramped inside<br />

locked walls and forced to work until exhaustion or death.<br />

After visiting the Devil’s Punchbowl, James E. Yeatman<br />

of the Western Sanitary Commission in <strong>No</strong>vember 1863<br />

wrote an appeal to President Lincoln regarding the<br />

condition of formerly enslaved Black Americans. Yeatman<br />

stated “seventy-five died in a single day… some returned<br />

to their masters on account of their suffering.”<br />

The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History in<br />

July 2019 explains the Devil’s Punchbowl was a camp in<br />

Natchez, Mississippi that held as many as 4,000 Black<br />

refugees in the summer of 1863, this number only<br />

growing as years went on. The aforementioned African<br />

American Registry estimates that over 20,000 freedmen<br />

and freedwomen were killed in one year, inside of this<br />

American concentration camp. According to Natchez City<br />

Archives from 2009, Don Estes is a retired Natchez City<br />

Cemetery Director, who conducted extensive research<br />

into individuals buried at the cemetery. Estes said that<br />

during his studies he learned that women and children<br />

9

were all but left to die in the three “punch bowls.”<br />

“Thousands and thousands died. They were begging to<br />

get out [to go] anywhere but there,” said Estes.<br />

The Devil’s Punchbowl’s lesser-known history as a<br />

mass grave points to the city’s ghosting of certain<br />

demographics. The New York Times on April 5, 2019<br />

asserts the city, Natchez, is even more riddled with history<br />

than it is with Old South manors and manners. Without<br />

the relatively recent recovery of the records of these<br />

bodies, their stories would not have been publicized in<br />

the modern age. Tours and guides by the Garden Club,<br />

the historical representative of the Devil’s Punchbowl<br />

focus on the period immediately preceding the Civil War<br />

and the long clash between <strong>No</strong>rth and South. Natchez,<br />

however, was established in 1716, meaning there are over<br />

100 years of unaccounted history not represented by most<br />

of the Pilgrimage’s tours, erasing the Black lives that lived<br />

and died in the area.<br />

The Mississippi Department of Archives and History in<br />

July 2013 documents Lizzy Brown, who in her diary, speaks<br />

of “flimsy structures built with her father’s lumber, which<br />

she could see from her plantation home.” This Under-the-<br />

Hill area of Natchez was where the camp was located, and<br />

Lizzy saw the horrors of a hastily constructed shack city.<br />

The Heritage Post on December 12, 2020 explains that<br />

today, the bluffs are known for the wild peach grooves,<br />

but the locals will not eat any of the fruit because of the<br />

bodies that fertilized the trees. One researcher noted<br />

that skeletal remains still wash up when the area becomes<br />

flooded by the Mississippi River at the Devil’s Punchbowl.<br />

While some of the stories remain told, they’re relegated<br />

to legend, not history due to the lack of research in the<br />

area. The Devil’s Punchbowl in and of itself is a story to<br />

be told and worth the research to uncover what really<br />

happened.<br />

information about heinous acts such as the Devil’s<br />

Punchbowl in Mississippi. However, as was the case with<br />

the Tulsa Race Massacre it often takes years of research<br />

to even bring the stories to light and actually bring some<br />

form of justice to the victims.<br />

The aforementioned Atlantic asserts the inevitable<br />

response of Americans to tragic stories of mass murder,<br />

of extreme destitution, of dangerous injustice, of a raw<br />

attack on democracy within the very borders of the<br />

United States, is ‘this is not who we are.’ But for white<br />

America, the reality of history should not be ignored.<br />

The Devil’s Punchbowl was not the only Black massacre<br />

swept under the rug The 1866 Memphis Massacre left 46<br />

Black Americans killed, 285 injured, and 5 raped yet no<br />

arrests were made. A 2020 report by the aforementioned<br />

Equal Justice Initiative points out the 1866 Memphis<br />

Massacre did not receive a historical marker until May<br />

2016. In a city with multiple Confederate monuments and<br />

a park named for Ku Klux Klan founder Nathan Forrest,<br />

this effort marked the first publicly funded historical<br />

commemoration of the massacre. <strong>No</strong>w, as other Black<br />

massacres like Lake Lanier in Georgia gain traction,<br />

the time for the reckoning of the Black lives lost is long<br />

overdue, and continues without attention.<br />

After uncovering the history of the Devil’s Punchbowl,<br />

with some crucial implications we learned...America’s<br />

history of intentionally not documenting events<br />

highlights its racist history. Prominent journalist Ida B.<br />

Wells puts it plainly: “The way to right wrongs is to turn<br />

the light of truth upon them.” In short, by uncovering<br />

Black massacres and addressing America’s history of<br />

racial violence we can finally begin reconciling with the<br />

past.<br />

It often takes years of extensive research for Black<br />

massacres to properly be brought to light.<br />

The Equal Justice Initiative in 2020 asserts quantitative<br />

documentation of past racial violence remains imprecise<br />

and incomplete. It should not be difficult to find<br />

10

ASHLEE WOODS<br />

Q&A<br />

JANESE<br />

CONSTANTINE<br />

ALABAMA WOMEN’S BASKETBALL ASSISTANT COACH<br />

Alabama athletics has its fair share of unsung<br />

heroes. For the Crimson Tide women’s basketball<br />

team, that’s assistant coach Janese Constantine.<br />

Constantine has been an integral part of the<br />

success of the tem under head coach Kristy Curry.<br />

Features and Experiences Editor Ashlee Woods sat<br />

down with Constantine to talk about her coaching<br />

journey, motherhood and Christianity.<br />

What started your passion for basketball?<br />

Janese Constantine: So I had an older brother, he was<br />

already involved in basketball, baseball, and soccer. Those<br />

were the four things he was involved with. My dad also<br />

plays football. My dad is still coaching right now. So I<br />

grew up in a basketball family. I just was naturally drawn<br />

to playing ball, being rough and being outside. I started<br />

playing around five, so I just had a natural passion for the<br />

game. That’s what got me going.<br />

Did you have any players that you looked up<br />

to when you started playing basketball?<br />

I was a huge, huge Lisa Leslie fan. I was actually really tall<br />

for my age. I was always the tallest kid in class, boy or girl.<br />

I’ll never forget when I was in fifth grade, my nickname<br />

was baby Shaq. I was taller than all the guys out there.<br />

Then, around seventh or eighth grade is when the guys<br />

started shooting on me. I really just stopped growing,<br />

then. But I was the tallest in class for a long time. So, I<br />

11<br />

Photo courtesy of UA Athletics

thought I was going to be a post player. I thought I was<br />

going to be 6’5. But I am not, but growing up I was a huge<br />

Lisa Leslie fan. I still am.<br />

How did you know or when did you know<br />

when you wanted to start to coach?<br />

Probably when I was in high school and college --- more so<br />

college. I went to this thing called Point Guard College. It<br />

was a really cool opportunity for me. It gave me a chance<br />

to see the game in another way, another light. It was more<br />

about talking about the game versus playing the game. It<br />

was in a classroom-like setting, so I really enjoyed that. It<br />

was seeing the doors basketball could open and thinking<br />

about how I can be involved once I got done playing.<br />

That’s when it kind of opened my eyes that I could really<br />

do this. <strong>No</strong>w back then, I didn’t really know if I thought I<br />

wanted to be a college coach. But I knew, at some point, I<br />

wanted to be coaching in my future.<br />

You’ve talked pretty frequently about being<br />

a tough coach when you started out in your<br />

coaching career. Was there a particular<br />

player, experience or even a season<br />

where you realized that maybe this style of<br />

coaching wasn’t the way to mentor these<br />

players?<br />

After my third year in coaching. I was at IUPUI at the time,<br />

and we got to the end of the year. I always feel like coaches<br />

get to do evaluations on players, tell them their strengths<br />

and weaknesses. I feel like as coaches, we don’t always take<br />

the time to then do that, ourselves. So what I did was I<br />

asked my players, ‘Tell me one thing that you think I’m<br />

good at and one thing I can do better.’ All of them told<br />

me you bring good energy, but they consistently all said,<br />

‘You’re too negative.’ I was like ‘Wow,’ and it kind of hurt.<br />

I was really kind of hurt. I had to take a step back and say,<br />

‘What do you mean? I’m coaching.’ They [the players] said<br />

‘Yeah, but it’s always with a negative connotation. You<br />

don’t pump us up enough.’ That was the turning point.<br />

I have to say, I’m not perfect at it. I’m sure I’ve still been<br />

deemed as negative at times. But, I am conscious of it. I<br />

try to make sure that I am filling their cups. I try to make<br />

sure I’m not nitpicking. I do try to make sure that I look<br />

at their effort, their intent. If they’re trying and they’re<br />

not getting it, then maybe I need to coach it better. Again,<br />

I’m not perfect. I’m sure I fail at times. I just try to have an<br />

awareness of just being positive.<br />

You’ve been very open about your faith.<br />

Have you always practiced Christianity? If<br />

not, when did you decide to delve into the<br />

faith a little bit more?<br />

I was fortunate enough that my parents introduced me<br />

to Christ at a young age and He’s always been a part of<br />

my life. I grew up going to church and Sunday School. I<br />

was a Sunday School teacher for a while. It’s always been a<br />

part of my life and I’m not perfect. There have been times<br />

where I’m like, ‘Whoa, I’m kind of triggered right now.<br />

I’ve got to get back to where my foundation is.’ I don’t try<br />

to force [my faith] on anyone. I don’t try to make you talk<br />

about it. I’m not trying to make my players talk about it.<br />

But if they want you, I’m hoping they aren’t afraid. I’m<br />

here for them if they want to have a conversation. I’ve had<br />

players that want to be saved, but don’t know how to do<br />

that. So, I think I’ve tried in that manner to just be there<br />

for them.<br />

We’ve seen different players, coaches and<br />

athletes become more open about their<br />

faith. Has that been inspiring to you at all,<br />

seeing that become more mainstream in<br />

sports culture?<br />

I think it’s all good. I think it’s about whatever you want<br />

to do personally. I love the boldness and the courage. But<br />

I think there are so many other people who may not be<br />

as outwardly and openly about it. It still doesn’t mean<br />

you’re not as strong and as passionate about it. For me,<br />

I’m one of those nights. I don’t wake up every morning<br />

and shout out or I make sure I tweet something spiritual.<br />

But if there is something on my heart, if I’m led to say<br />

something, I’ll do it. I’ll post it and I’ll talk about it. But I<br />

don’t feel like I have to always be over the top. But when<br />

I’m led to [share something spiritual], then I’ll definitely<br />

12

try and put it out there for people because I never know<br />

who I may be encouraging.<br />

Transitioning over to your journey to<br />

Alabama, when did you know that you<br />

possibly wanted to branch out and leave<br />

Indiana?<br />

Well, I actually got here by way of my husband. He got<br />

a football job here before I got the basketball job here.<br />

So when he got the football job here, we decided to leave<br />

Indiana to help to pursue his career. It’s hard to say no to<br />

anything Alabama football-related. So, I got down here and<br />

after three weeks, that’s when they [women’s basketball]<br />

had the opening. That’s how I got involved with Alabama<br />

women’s basketball so my journey down here was a little<br />

different. I was actually content in Indiana, where I was,<br />

and I was 45 minutes from home, from my parents. All<br />

that was a big plus when I had my first child.<br />

How has being a mother impacted your<br />

coaching style?<br />

It’s made me a better coach. I think I’m looking at things<br />

differently. I see things differently. I think it’s helped<br />

me relate to kids differently. I think it helps me relate to<br />

their space differently. It helps me be more gracious. It<br />

helps me to be way more forgiving and try to be kinder.<br />

There was a situation where a young lady on a team got<br />

into some trouble on our team. My heart was broken.<br />

Someone said, ‘Well, why does that hurt you?’ I said,<br />

‘Because that’s somebody’s baby.’ They made a mistake<br />

and now their business is kind of out there. I don’t think<br />

they did that on purpose. She didn’t wake up to try to<br />

make a mistake, but she made it. So I’m saddened that I<br />

know that’s somebody’s baby, and I know they still raised<br />

them right. I would want someone to have the same grace<br />

and compassion towards my girls. I just think everything<br />

has made me more in touch with the reality of what these<br />

young ladies go through day-to-day and the decisions<br />

that they have to make --- whether right or wrong --- but<br />

the decisions they have to make and how they learn from<br />

them.<br />

athletics at the collegiate level. What does<br />

it feel like to be a part of this new wave of<br />

women’s sports mentoring these players<br />

that are being broadcast on ESPN and<br />

ABC?<br />

It definitely feels good because I think you’re part of an<br />

evolution of a way that is allowing just more and more<br />

access to them. More access to their personal lives, more<br />

access to how they handle things and do things and the<br />

publicity that they get. I think it’s amazing. But, I think<br />

it challenges them of why making good decisions is such<br />

a huge thing now because of the access and now you have<br />

put on and plastered on the front of TVs and posters.<br />

Everything is in the light, everything that they do and<br />

so being a good role model, things of that nature [is<br />

important]. It’s fun to be a part of this and it’s fun to have<br />

all your games on TV. It’s fun to tell your family. ‘Hey, we’ll<br />

be on this channel!” All that’s fun. I think it’s a fun, fun<br />

time to be involved with athletics.<br />

What has been the most inspiring part of<br />

your coaching journey?<br />

When I see the ladies that I’ve coached post-college.<br />

When I see them now with babies, husbands, jobs and<br />

careers and different moves. That is what to me becomes<br />

the most inspiring. For them to tell me, ‘Hey, I appreciate<br />

you. You just mean so much to me,’ I think that’s probably<br />

what brings me the greatest joy knowing that. I tell them<br />

all the time, I pray that one day we can be friends. I pray<br />

that when you get done, we had a strong enough bond<br />

that you didn’t mind me pushing you. One of my former<br />

players --- her name is Brenna --- she’s done playing now.<br />

One of the things she tells me all the time, ‘I appreciate<br />

you every day for never letting me settle. Never letting<br />

me settle for anything less than my best. That, for me, lets<br />

me know to keep going. Keep pushing these young ladies<br />

because they’ll be thankful, they’ll be grateful. You won’t<br />

win them all, you won’t. I’ve had players I’ve coached that<br />

when they’re done, we may never speak again. It’s nothing<br />

bad. It’s just that maybe we just didn’t click. But I still<br />

have way more that still stay in touch, still reach out.<br />

We’ve seen over the past couple of years<br />

rapid growth and coverage of women’s<br />

13

SUMMER AND FALL<br />

REGISTRATION OPENS<br />

April 8!<br />

Visit sheltonstate.edu to apply and register!<br />

It is the policy of the Alabama Community College System Board of Trustees and Shelton State Community College, a<br />

postsecondary institution under its control, that no person shall, on the grounds of race, color, national origin, religion,<br />

marital status, disability, gender, age, or any other protected class as defined by federal and state law, be excluded<br />

from participation, denied benefits, or subjected to discrimination under any program, activity, or employment.

CHRISTINE THOMPSON<br />

ACTIVISM<br />

A PERSONAL REFLECTION<br />

REDEFINED<br />

15<br />

Introduction<br />

Sorting through the countless files in the Google drive,<br />

I began logging and transcribing each of the audio<br />

files in the folder. It was the first week of my fellowship<br />

with United Women of Color – a nonprofit dedicated to<br />

community-based solutions for racialized violence in my<br />

hometown of Huntsville, Alabama.<br />

UWOC was my latest attempt at identifying the needs in<br />

my community and actively working to supplement the<br />

gaps. Law school was the end goal, and meaningful civic<br />

engagement would allow me to identify the areas of law<br />

I wanted to practice, and prepare for long-term advocacy<br />

in the legal field.<br />

The audio files contained various interviews of Black and<br />

white families sharing their perspective on race-relations<br />

in 2021. My supervisor had given me little information<br />

on the content of the interviews – only that the<br />

transcriptions and summaries would be presented to the<br />

Huntsville City Council in a case against the Huntsville<br />

Police Department. I clicked on the file labeled “Ava 1” and<br />

began typing short descriptions as the audio played:<br />

“Woman says that in everyday life she felt safe when seeing<br />

police officers in the community: she had no reason to be<br />

nervous, never felt like they had any ill will or malice.<br />

Woman describes seeing police officers at a protest heavily<br />

armed like they were about to ‘invade.’ ‘impending doom.’<br />

‘It felt scary and it felt like I couldn’t trust them-’<br />

Before the minute-long interview could end, a realization<br />

washed over me: The protest “Ava” was recounting, was<br />

the same demonstration I attended a year and a half ago.<br />

Brief Background<br />

The morning of the protest, I told my cousin, a former<br />

parole officer, that I didn’t plan on attending. It wasn’t<br />

because I didn’t believe in the cause – but, rather, I<br />

felt better suited to engage in alternative forms of<br />

activism. That summer, I had edited 12 poignant articles<br />

highlighting the racial justice movement for the limitededition<br />

summer issue of Alice, interned for a New York<br />

politician with projects focused on COVID-19 healthcare<br />

equity, and participated in a Pre-Law Program. Surely,<br />

most of this involvement allowed me a “rain-check”<br />

from this potentially dangerous protest. Yet, there was<br />

a lingering sentiment of guilt that accompanied my<br />

declaration that I was staying home.<br />

My father, born and raised in Monroeville Alabama, to a<br />

farmer and housewife, was 62 years old when I was born.<br />

Throughout his life, he advocated for Black families of<br />

fallen WW2 veterans, served as a magistrate, marched for<br />

civil rights on Bloody Sunday, and eventually, became an<br />

Organic Chemistry professor at Alabama A&M University.<br />

Only a year after his untimely death, the more exciting<br />

stories of his activism contributed to an overwhelming<br />

pressure to advocate for racial justice like he did: loudly<br />

and on the front lines.

Moreover, as his sole offspring, I had a responsibility to<br />

continue his legacy. With this in mind, I threw together<br />

a makeshift poster, organized a carpool, and headed<br />

downtown.<br />

Despite being entirely nonviolent, the protest ended in<br />

the brutal tear gassing of several hundred protesters.<br />

Even with 20 years of racialized harassment under my<br />

belt, I always said that the country my father described<br />

was an America I didn’t know. The chaos that ensued<br />

on that foggy Wednesday evening served as a terrifying<br />

introduction to that America.<br />

Reflection<br />

My attendance was fueled by a desire to advocate for racial<br />

justice as he did, but criminal justice law was traumatizing<br />

and heavy for me. My undergraduate research featuring<br />

true cases of Black, underage human trafficking survivors<br />

was rewarding, yet horrifyingly memorable.<br />

how academic empowerment can be the biggest blow to<br />

white supremacy.<br />

Conclusion<br />

Like that summer, my fellowship soon came to an end.<br />

However, like parting gifts, I treasured the lessons they<br />

left for me: There are countless ways to advocate for<br />

racial justice - all equally impactful. Racial inequities in<br />

healthcare or family law are equally as important as racial<br />

inequities in policing and incarceration.<br />

Whether it’s representing Black entrepreneurs cheated by<br />

predatory legal agreements in contract law, or protecting<br />

Black creators in intellectual property, the legal field I<br />

choose will advance the values my father championed. In<br />

doing so, reminding others of a reality that myself, “Ava”,<br />

and countless Black Americans know all too well – the law<br />

is a lived experience.<br />

Post-protest, I reflected on my academic journey up to that<br />

point. On my quest to make a difference, I had – albeit<br />

unintentionally - created a self-imposed monolith about<br />

what it meant to combat racial injustice. One composed<br />

solely of dramatically leading protests and sit-ins, but<br />

excluded creative writing, working for nonprofits in my<br />

community, and shamelessly pursuing a field where I am<br />

drastically underrepresented.<br />

Essentially, I didn’t have to protest to join the fight against<br />

anti-blackness. Similarly, I don’t have to practice criminal<br />

justice law, to advocate for racial equity in the legal field.<br />

Further, when analyzing my father’s history, I had<br />

overlooked his most impactful and lengthy form of<br />

activism: his 40 years as an Organic Chemistry professor.<br />

Throughout my childhood, I perceived the highlights<br />

of his activism to have been the ones recorded in the<br />

history books. Yet, the Black graduates he inspired in his<br />

decades of teaching are living, breathing, examples of<br />

16

A LETTER OF ADVICE FROM<br />

JASMINE HOLLIE<br />

Dear Students,<br />

My greatest advice for having a successful and flourishing<br />

undergraduate career is to take advantage of all resources<br />

on campus. Right now, as a student at THE University of<br />

Alabama you are already ahead of the game. There are<br />

countless mentors, programs and organizations available<br />

to help you succeed as a student. Take advantage. You<br />

already have the world at your fingertips, you just have to<br />

grab it. Personally, if I could redo my college experience I<br />

would take advantage of more resources and opportunities<br />

offered at UA.<br />

Another key to success: Internships. Interning has helped<br />

me land my first job in Journalism just one short year<br />

after graduating. Internships will provide you with the<br />

professional experience needed to succeed in your field.<br />

They will also open countless doors for you once you<br />

graduate. I highly recommend researching different<br />

internships that best suit your professional goals. Finally,<br />

but most importantly, prioritize your mental health. Your<br />

mental health is just as important as your education. You<br />

won’t be able to perform your best academically if you<br />

are not okay mentally. Get some sleep, stay organized,<br />

practice self-care and take deep breaths. As long as you<br />

work hard and apply yourself, everything will work itself<br />

out.<br />

So remember: Take advantage, intern, and don’t forget to<br />

breathe.<br />

Jasmine Hollie<br />

Class of 2020<br />

17

#LovetheloftstyleL o v e t h e l o f t s t y l e<br />

c o n t a c t u s t o d a y a b o u t o u r s p e c i a l f o r f a l l 2 0 2 2<br />

1 3 4 5 1 0 t h A v e n u e E . T u s c a l o o s a , A L 3 5 4 0 4 | 2 0 5 . 2 6 7 . 5 9 1 0 | w w w . t h e l o f t s a t c i t y c e n t e r . c o m

HIDDEN<br />

FIGURES<br />

1956MAGAZINE