Where the Leaves Fall - Resetting Global Food Systems (from issue #4)

As global food systems and supply chains have been disrupted by Covid-19, Francis Mwanza, researcher and writer on African and local foods, and former head of office of the United Nations World Food Programme’s London office, UK, introduces a series of interviews looking at how communities around the world are adapting and finding local food security solutions to a pandemic-struck planet.

As global food systems and supply chains have been disrupted by Covid-19, Francis Mwanza, researcher and writer on African and local foods, and former head of office of the United Nations World Food Programme’s London office, UK, introduces a series of interviews looking at how communities around the world are adapting and finding local food security solutions to a pandemic-struck planet.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Exploring humankind's connection with nature<br />

WHERE THE LEAVES FALL<br />

WHERE<br />

THE<br />

LEAVES<br />

FALL<br />

Mutualism / Interconnectedness / Pandemic<br />

01<br />

SAMPLE

EDITORIAL<br />

We edit and publish a quarterly magazine, <strong>Where</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Leaves</strong><br />

<strong>Fall</strong>, exploring humankind’s connection with nature, created<br />

in conversation with OmVed Gardens. Our aim is to amplify<br />

under-represented voices, knowledge, and perspectives <strong>from</strong><br />

around <strong>the</strong> world, to inspire positive personal and social<br />

change. Each <strong>issue</strong> of <strong>the</strong> magazine is divided into three<br />

<strong>the</strong>med sections alongside a series of dialogues.<br />

For <strong>the</strong> fourth <strong>issue</strong> of <strong>the</strong> magazine we came to reflect on<br />

<strong>the</strong> pandemic, and how it has highlighted <strong>the</strong> fragility of<br />

our food systems. Francis Mwanza introduces <strong>the</strong> section<br />

<strong>Resetting</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Food</strong> <strong>Systems</strong> in which we meet a number of<br />

extraordinary people <strong>from</strong> around <strong>the</strong> world who discuss <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

initiatives to offer healthy sustenance to <strong>the</strong>ir communities.<br />

_<br />

Luciane and David / The editors / @wtlfmag<br />

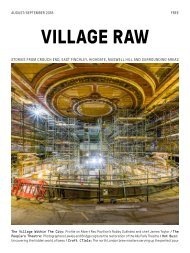

PHOTOGRAPH BY ANGELES RODENAS.<br />

Subscribe for <strong>the</strong> magazine:<br />

www.where<strong>the</strong>leavesfall.com<br />

Sign up for <strong>the</strong> newsletter:<br />

www.where<strong>the</strong>leavesfall.com/newsletter<br />

03

WHERE THE LEAVES FALL<br />

Introduction by Francis Mwanza<br />

<strong>Global</strong> <strong>Food</strong> <strong>Systems</strong><br />

Interviews by David Reeve, Patrick Steel and Angeles Rodenas<br />

PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF COLECTIVO AHUEJOTE.<br />

04<br />

05

WHERE THE LEAVES FALL<br />

RESETTING GLOBAL FOOD SYSTEMS<br />

As global food systems and<br />

supply chains have been<br />

disrupted by Covid-19, Francis<br />

Mwanza, researcher and writer<br />

on African and local foods,<br />

and former head of office of<br />

<strong>the</strong> United Nations World<br />

<strong>Food</strong> Programme’s London<br />

office, UK, introduces a series<br />

of interviews looking at how<br />

communities around <strong>the</strong> world<br />

are adapting and finding local<br />

food security solutions to<br />

a pandemic-struck planet.<br />

Many years ago I interviewed a Zambian village<br />

elder who warned me against eating processed<br />

foods, which are unhealthy and unreliable, and<br />

recommended eating local foods. Any talk about<br />

local foods, <strong>the</strong>n and now, tends to focus on<br />

vegetables, fruits and, sometimes, edible insects<br />

like mopane worms or locusts, and very small<br />

amounts of meat. This has helped my family during<br />

this pandemic as we have been dependent<br />

on our garden for cultivated and spontaneous<br />

vegetables, just as <strong>the</strong> elder advised.<br />

Covid-19 has brought renewed global focus on<br />

local producers, local foods and food supply systems.<br />

It has come at a time when global food needs<br />

are at unprecedented levels, with one out of nine<br />

people facing hunger every day and a record 168<br />

million already requiring humanitarian assistance.<br />

As <strong>the</strong> World <strong>Food</strong> Programme points out,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Covid-19 pandemic is complicating existing<br />

crises and threatening to worsen o<strong>the</strong>rs, with<br />

<strong>the</strong> potential for multiple famines in <strong>the</strong> coming<br />

months. And <strong>the</strong> UN is reporting that <strong>the</strong>re is<br />

now a high risk that <strong>the</strong> broader disruptive effect<br />

of Covid-19 will drive up levels of global food insecurity.<br />

Yet one third of <strong>the</strong> food produced - that<br />

could feed all of <strong>the</strong> world’s vulnerable people -<br />

goes to waste.<br />

This pandemic is but one example of likely crises<br />

<strong>the</strong> world faces and should prepare for. Fixing<br />

our broken food system is more urgent than ever<br />

before. Everyone eats, <strong>from</strong> Afghanistan to Zimbabwe.<br />

And everyone is involved in <strong>the</strong> food system,<br />

whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> system is local, regional or global.<br />

Unfortunately, <strong>the</strong> most common system is<br />

<strong>the</strong> agro-industrial system, dominated by a few<br />

multinational corporations, flooding markets with<br />

predominantly processed foods, which include<br />

unhealthy levels of sugar, salt, and fat, leading to<br />

health <strong>issue</strong>s like obesity, heart disease, high blood<br />

pressure, and diabetes (all risk factors for Covid-19).<br />

With lockdowns, sparked by <strong>the</strong> spread of<br />

coronavirus, <strong>the</strong> global food system and its global<br />

supply chains have been disrupted and continue<br />

to be under pressure. The pandemic is negatively<br />

and seriously affecting economies and daily life<br />

everywhere.<br />

Now, after years marked by limited access to<br />

food, particularly for <strong>the</strong> poorest, rising or often<br />

fluctuating prices, ecological threats to seed diversity,<br />

and what is generally referred to as “food<br />

sovereignty”, Covid-19 is demanding that we hit<br />

<strong>the</strong> reset button on our broken food system.<br />

Local food systems are becoming stronger<br />

because of <strong>the</strong>ir short supply chain, minimally<br />

processed food <strong>from</strong> local farmers, and food that<br />

fits local consumption habits. The push now is for<br />

resilient and sustainable food systems for urban<br />

centres, peri-urban and rural areas, with increasing<br />

emphasis on sufficient and diverse local production,<br />

affordable prices, good quality, healthy<br />

eating, and a stable food supply.<br />

In major cities, whe<strong>the</strong>r it be New York, Kigali,<br />

Harare, Bogota, Mumbai, or Lahore, an increasing<br />

number of people are responding creatively with<br />

non-traditional farming methods: tunnel, vertical<br />

and micro gardening. We are now seeing more<br />

rooftop gardens in unlikely places in both developed<br />

and developing countries.<br />

These methods are helping shorten supply<br />

chains, ensuring access to fresh foods, with a<br />

smaller carbon footprint compared with <strong>the</strong> international<br />

food supply chain. Restaurants are<br />

also engaging in precision indoor gardening. And<br />

chefs in <strong>the</strong> mainstream restaurants are exploring<br />

local markets for local ingredients and hi<strong>the</strong>rto<br />

little-used food plants.<br />

In Africa and Latin America, for example, it is estimated<br />

that some 360 million residents are already<br />

engaged in urban or peri-urban local food production.<br />

In Fiji, home gardening is being promoted and<br />

funded by <strong>the</strong> government as a direct response to<br />

Covid-19 and <strong>the</strong> challenges of <strong>the</strong> disrupted food<br />

supply chain. And <strong>the</strong>re is ano<strong>the</strong>r push: a push for<br />

“ancestral” foods. There is now a stronger movement<br />

trying to protect rare indigenous seeds and<br />

take seeds back to tribal communities.<br />

Traditional lifestyles and eating locally-grown<br />

or locally-available spontaneous plants are being<br />

seen as an effective arsenal to dampen <strong>the</strong> effects<br />

of <strong>the</strong> broken global food system and improve <strong>the</strong><br />

health of local communities with nutritional, rich,<br />

local foods. While conventional vegetables like<br />

cabbage, lettuce and spinach are often heavily<br />

dependent on inputs such as fertilisers and pesticides,<br />

<strong>the</strong> cost of which continue to rise and<br />

can have negative impacts on <strong>the</strong> environment,<br />

traditional vegetables like amaranth and African<br />

egg plant have an advantage because <strong>the</strong>y produce<br />

well without such inputs. This holds out <strong>the</strong><br />

prospect of a broad, hardy, nutritionally-sound local<br />

food base, which does not require inputs (that<br />

many local farmers cannot afford).<br />

Covid-19 is fuelling <strong>the</strong> fire for addressing <strong>the</strong><br />

failures of an inequitable and broken global food<br />

system and demanding that we address food security<br />

<strong>issue</strong>s differently. As <strong>the</strong> interviews in this<br />

section show, <strong>the</strong> pandemic may be hurting us and<br />

undermining food security for <strong>the</strong> poorest, but it is<br />

also helping to highlight <strong>the</strong> necessity for thriving<br />

local and regional food systems, and focus on Indigenous,<br />

sustainable, and nutritious local foods.<br />

06 07

WHERE THE LEAVES FALL<br />

WHERE THE LEAVES FALL<br />

08 09

WHERE THE LEAVES FALL<br />

RESETTING GLOBAL FOOD SYSTEMS<br />

1.<br />

2.<br />

6.<br />

5.<br />

3.<br />

4.<br />

US<br />

1. Samuel S. T. Pressman, founder,<br />

Samuel’s <strong>Food</strong> Gardens<br />

Samuel founded Samuel’s <strong>Food</strong><br />

Gardens in Brooklyn, New York, to<br />

inspire and teach city dwellers<br />

how to grow food at home. His first<br />

rooftop garden was built during<br />

<strong>the</strong> pandemic, in May 2020, on a<br />

rooftop patio in Brooklyn to provide<br />

food for himself and his flatmates,<br />

and he has partnered with<br />

<strong>the</strong> RETI Center to work on food<br />

security and rapid resilience health<br />

initiatives like Covid-19 testing and<br />

mask handouts.<br />

PHILIPPINES<br />

2. Cherrie Atilano, founder<br />

and CEO, AGREA<br />

Cherrie founded AGREA to focus<br />

on sustainable agriculture in <strong>the</strong><br />

Philippines, a country of more<br />

than 7,000 islands. The country is<br />

reliant on Vietnam and Thailand for<br />

rice, and food imports are flown or<br />

shipped to <strong>the</strong> islands. AGREA is<br />

working to connect local farmers<br />

with local markets, and promote<br />

gardening and farming to ensure<br />

food security for <strong>the</strong> country.<br />

SIERRA LEONE<br />

3. Fatmata Mansaray, Kenema<br />

Kola Nut producer, member<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Slow <strong>Food</strong> Network<br />

Fatmata is a community educator<br />

and an activist in <strong>the</strong> fields of sustainable<br />

agriculture and development.<br />

She is active in <strong>the</strong> 10,000<br />

Gardens in Africa project, which<br />

includes <strong>the</strong> establishment of gardens<br />

in schools to provide healthy<br />

food for schoolchildren. She is<br />

committed to <strong>the</strong> diffusion of slow<br />

food values, consumer education,<br />

training <strong>the</strong> next generation, and<br />

promoting local biodiversity.<br />

TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO<br />

4. Alpha Sennon, founder, WhyFarm<br />

Alpha launched WhyFarm in 2015<br />

to promote sustainable agriculture<br />

to young people through what he<br />

terms agri-edutainment. WhyFarm<br />

also runs <strong>the</strong> Farmers Collective,<br />

through which new farmers come<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r and exchange labour,<br />

goods, and products. One of Why-<br />

Farm’s signature projects is <strong>the</strong><br />

creation of a superhero character<br />

called Agriman, <strong>the</strong> world’s most<br />

powerful food provider, who is<br />

<strong>the</strong>re to ensure that children eat<br />

healthily and don’t waste one grain<br />

of rice.<br />

PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF SAMUEL’S FOOD GARDENS (1), AGREA (2), SLOW FOOD INTERNATIONAL (3), WHYFARM (4),<br />

ST RAPHAEL EDIBLE GARDEN (5), COLECTIVO AHUEJOTE (6), HÁBITAT SUR (7), PROJECT MUMBAI (8).<br />

UK<br />

5. Jim Sheeran, manager,<br />

St Raphael Edible Garden<br />

Jim manages <strong>the</strong> St Raphael Edible<br />

Garden, which is based on St<br />

Raphael’s estate, <strong>the</strong> most disadvantaged<br />

neighbourhood in Brent,<br />

London. The garden also hosts <strong>the</strong><br />

Sufra food bank and community<br />

hub, which distributes food and<br />

support to vulnerable people and<br />

families living in extreme poverty,<br />

helping <strong>the</strong>m to survive, improve<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir wellbeing, and find work to<br />

become financially stable.<br />

MEXICO<br />

6. Raúl Mondragón, founder,<br />

Colectivo Ahuejote<br />

Raúl founded Colectivo Ahuejote to<br />

work with farmers in <strong>the</strong> Xochimilco<br />

lake area to <strong>the</strong> south of Mexico<br />

7.<br />

City, first settled by <strong>the</strong> Aztecs,<br />

where floating islands known as<br />

chimpanas are farmed according<br />

to traditional methods. The<br />

organisation’s focus is on building<br />

a sustainable agrifood system, connecting<br />

<strong>the</strong> farmers to consumers<br />

and local markets through sales<br />

networks and eco-tourism.<br />

COLOMBIA<br />

7. Adriana Bueno, founder,<br />

Hábitat Sur<br />

Adriana founded Hábitat Sur to<br />

highlight and preserve <strong>the</strong> social,<br />

cultural and ecological wealth of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Amazon. Her organisation runs<br />

<strong>the</strong> Hábitat Sur Nature Reserve, a<br />

responsible tourism project based<br />

on agroecological principles; <strong>the</strong><br />

NgüeChica Cultural Centre, which<br />

focuses on <strong>the</strong> intergenerational<br />

transmission of knowledge <strong>from</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> elders of <strong>the</strong> Indigenous Tikuna,<br />

Yagua and Kokama tribes to <strong>the</strong><br />

younger generations; and El Rastrojo<br />

Cultural and Environmental<br />

Centre, a local market on <strong>the</strong> outskirts<br />

of Leticia for artists, artisans,<br />

farmers, and entrepreneurs.<br />

INDIA<br />

8. Shishir Joshi, co-founder,<br />

Project Mumbai<br />

Shishir founded Project Mumbai<br />

in 2018 as a not for profit to<br />

promote civic empowerment and<br />

volunteering. During <strong>the</strong> pandemic<br />

Project Mumbai was a partner in<br />

<strong>the</strong> launch of Khaanachahiye, an<br />

initiative to provide food relief to<br />

people affected by <strong>the</strong> lockdown,<br />

feeding over 6 million people<br />

across <strong>the</strong> region.<br />

8.<br />

10 11

WHERE THE LEAVES FALL<br />

RESETTING GLOBAL FOOD SYSTEMS<br />

How has <strong>the</strong> pandemic affected you and your<br />

community?<br />

Cherrie (Philippines): It was harvest time in <strong>the</strong><br />

Philippines when <strong>the</strong> lockdown started in March.<br />

A lot of produce was harvested because usually 8<br />

million tourists come to <strong>the</strong> country for <strong>the</strong> summer;<br />

people are on <strong>the</strong> beach, and <strong>the</strong> restaurants<br />

need to be supplied. Then all of a sudden<br />

this pandemic just collapsed everything. There<br />

was produce rotting on farmers’ fields, no market<br />

any more, and a lot of restrictions were on <strong>the</strong><br />

farmers. There was also a stigma around leaving<br />

<strong>the</strong> house with <strong>the</strong> Covid-19 virus around and a<br />

lot of <strong>the</strong> farming communities were not allowed<br />

to leave <strong>the</strong>ir houses to go to <strong>the</strong> farm.<br />

Adriana (Colombia): The Amazon was one of <strong>the</strong><br />

regions of Colombia most affected by <strong>the</strong> virus,<br />

with a rate of infections per 100,000 inhabitants<br />

that was 42.9 times <strong>the</strong> national average. <strong>Food</strong><br />

supplies (non-perishable food and some fruits<br />

and vegetables that are difficult to grow locally)<br />

come to Leticia ei<strong>the</strong>r by plane <strong>from</strong> Bogota, <strong>from</strong><br />

Tabatinga in Brazil, or <strong>from</strong> Iquitos in Peru. With<br />

<strong>the</strong> lockdown, all borders were closed both for<br />

goods and people, and <strong>the</strong> closure of <strong>the</strong> airport<br />

and ports severely affected <strong>the</strong> food delivery<br />

chain to <strong>the</strong> region.<br />

Fatmata (Sierra Leone): With experience of <strong>the</strong><br />

2014 Ebola outbreak in mind, in which Sierra Leone<br />

saw 14,000 cases and nearly 4,000 deaths,<br />

<strong>the</strong> government developed a Covid-19 preparedness<br />

plan three weeks before its first case was<br />

confirmed. This enabled <strong>the</strong> Ministry of Health to<br />

quickly identify, test and quarantine most of <strong>the</strong><br />

primary contacts of any cases, limiting <strong>the</strong> spread<br />

of <strong>the</strong> disease.<br />

Raúl (Mexico): In Mexico <strong>the</strong> lockdown was not<br />

that strict, but people got scared and didn’t want<br />

to go out to buy things - so in one way <strong>the</strong> food<br />

system, <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> consumer-end, changed. The<br />

central market, Central De Abasto, was a red alert<br />

place - <strong>the</strong>re were a lot of contagious people - so<br />

some producers stopped supplying it and started<br />

to look for o<strong>the</strong>r channels to get <strong>the</strong>ir produce out.<br />

Walmart and <strong>the</strong> supermarkets, like Amazon,<br />

got very strong because of home delivery. And<br />

some social spheres, like <strong>the</strong> middle classes and<br />

upper middle classes, stopped going out to buy<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir groceries but switched to buying online to<br />

get whatever <strong>the</strong>y wanted. For <strong>the</strong> lower social<br />

classes, <strong>the</strong>y have to live, <strong>the</strong>y have to buy dayby-day,<br />

so <strong>the</strong>y still went to <strong>the</strong> market.<br />

Samuel (US): When Covid-19 hit New York City,<br />

<strong>the</strong> grocery stores immediately went into chaos.<br />

They were unable to keep up with <strong>the</strong> demand for<br />

fresh food due to a breakdown in <strong>the</strong> nationwide<br />

macro food distribution system, in which food is<br />

imported <strong>from</strong> around <strong>the</strong> world and also travels<br />

several states to get here.<br />

Not only were stores largely out of produce,<br />

but <strong>the</strong> prices went up. Due to <strong>the</strong> price spikes<br />

and inconsistent availability of fresh produce,<br />

many low-income residents and families have<br />

been forced to buy what <strong>the</strong>y can afford, which<br />

is all highly processed food items. In some areas,<br />

I have also seen <strong>the</strong> price of a couple of large<br />

tomatoes costing more than a loaf of bread and<br />

peanut butter combined.<br />

Adriana (Colombia): During <strong>the</strong> first couple of<br />

weeks of <strong>the</strong> lockdown, food price speculation<br />

started to be an <strong>issue</strong> even when <strong>the</strong>re was still<br />

enough food to supply <strong>the</strong> local market. This was<br />

more to do with a move by local supermarkets to<br />

make <strong>the</strong> most out of <strong>the</strong> beginning of <strong>the</strong> crisis<br />

and <strong>the</strong> panic-shopping wave that hit as soon as<br />

<strong>the</strong> lockdown was announced.<br />

Fatmata (Sierra Leone): With <strong>the</strong> closure of restaurants<br />

and hotels in Sierra Leone, demand for<br />

higher end food categories, such as meat and<br />

fresh produce, was already depressed. In <strong>the</strong><br />

medium- to long-term, demand is likely to fall fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

as more people could lose <strong>the</strong>ir jobs, disproportionately<br />

affecting low-income earners and<br />

informal jobs in urban and rural areas.<br />

Given that lower-income households often<br />

spend 60% to 70% of <strong>the</strong>ir incomes on food,<br />

even a moderate reduction could lead to nutritional<br />

problems <strong>from</strong> skipping meals, reducing caloric<br />

intake, or switching to cheaper but less nutritious<br />

Rodney Dawkins, who has lived on<br />

St Raphael’s Estate with his wife<br />

for eight years, had never seriously<br />

contemplated eating <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> plot<br />

to <strong>the</strong> table before <strong>the</strong> pandemic<br />

struck. Furloughed <strong>from</strong> his job<br />

as a warehouse supervisor, and<br />

with his children back home <strong>from</strong><br />

university, gardening his patch<br />

has provided him with space<br />

and a sense of purpose. “It was<br />

just a bushy garden full of weeds<br />

before <strong>the</strong> lockdown”, he says.<br />

Now he is growing tomatoes, peas,<br />

lettuce, green beans, cabbage,<br />

peppers, and lemon and orange<br />

trees. He says it has given him a<br />

greater appreciation for nature,<br />

and by replacing a daily intake of<br />

chocolate with strawberries he<br />

has improved his diet. “Compared<br />

to <strong>the</strong> food <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> supermarkets<br />

this is much fresher and tastes<br />

much sweeter,” he says. Although<br />

far <strong>from</strong> self-sufficient, he adds,<br />

it has also been a money saver.<br />

12 13

WHERE THE LEAVES FALL<br />

RESETTING GLOBAL FOOD SYSTEMS<br />

foods. This is likely to be exacerbated by school<br />

closures, given that school meals and our Slow<br />

<strong>Food</strong> Schools Gardens programme are often a<br />

major source of nutrition for children.<br />

<strong>the</strong>m do not have space to grow <strong>the</strong>ir own food,<br />

and a large proportion of <strong>the</strong> population derive<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir income ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>from</strong> tourism-related activities,<br />

commerce, or <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> informal economy.<br />

Not all new growers have a<br />

garden. Claudette Drummond<br />

lives in a top floor flat in a block<br />

on St Raphael’s Estate but <strong>the</strong><br />

lack of space hasn’t prevented<br />

her <strong>from</strong> growing potted<br />

brussels sprouts, tomatoes,<br />

lavender and rosemary along<br />

<strong>the</strong> walkway. “I’m hoping <strong>the</strong><br />

pumpkin plant will go all <strong>the</strong> way<br />

up <strong>the</strong> drainpipe and around<br />

<strong>the</strong> kitchen window,” she says.<br />

PHOTOGRAPHS BY ANGELES RODENAS (THIS PAGE, PREVIOUS PAGE AND PAGES 108-109).<br />

Shishir (India): The pandemic affected everyone,<br />

but most of all <strong>the</strong> marginalised communities living<br />

in underprivileged pockets across <strong>the</strong> city.<br />

Mumbai is home to around 7.1 million migrants.<br />

These people were mostly employed as daily<br />

wage labourers or engaged in menial jobs, many<br />

in <strong>the</strong> infrastructure and construction business.<br />

The lockdown adversely impacted this informal<br />

sector by completely pausing <strong>the</strong>ir wages.<br />

Jim (UK): Our food bank in north London had a<br />

huge increase in demand for food <strong>from</strong> people<br />

who lost <strong>the</strong>ir jobs. The produce in our garden<br />

wasn’t hugely affected because it was <strong>the</strong> start<br />

of <strong>the</strong> growing season, but our volunteers didn’t<br />

have <strong>the</strong> opportunity to devote <strong>the</strong>ir time to<br />

coming once a week to <strong>the</strong> garden - <strong>the</strong>y were<br />

told to stay away - and it affected <strong>the</strong>m mentally.<br />

It didn’t have an impact on growing produce because<br />

I diverted my attention <strong>from</strong> my management<br />

responsibilities to focus on growing.<br />

Alpha (Trinidad and Tobago): When <strong>the</strong> pandemic<br />

got to Trinidad we were on a full lockdown,<br />

everywhere closed down, and everyone wanted<br />

to plant something because that was like <strong>the</strong><br />

most common activity to do. No one knew what<br />

was going to happen with food. So everyone was<br />

trying to secure <strong>the</strong>ir own plate.<br />

Adriana (Colombia): During <strong>the</strong> crisis Indigenous<br />

communities were able to rely on <strong>the</strong>ir chagras<br />

(smallholdings) to produce a large part of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

food, and most of <strong>the</strong>m ei<strong>the</strong>r fished or hunted<br />

to provide <strong>the</strong>ir families with animal protein.<br />

In many communities we visited, people told us<br />

that before <strong>the</strong> pandemic, <strong>the</strong>y were not working<br />

<strong>the</strong> land because <strong>the</strong>y were getting income <strong>from</strong><br />

tourism, but now most families have gone back to<br />

work <strong>the</strong>ir chagras with <strong>the</strong> realisation that food<br />

sovereignty is critical for <strong>the</strong>ir people.<br />

For most of <strong>the</strong> city dwellers, <strong>the</strong> food and<br />

economic crisis was more severe as most of<br />

Jim (UK): There was a chronic shortfall of topsoil<br />

and compost because everybody was ordering<br />

<strong>the</strong>se. It was very difficult to get hold of seeds<br />

and <strong>the</strong>re were also delays in receiving plot<br />

plants. The whole world ground to a halt due to<br />

shortages of goods and delays in delivery. Placing<br />

orders online was difficult as well.<br />

Fatmata (Sierra Leone): This pandemic imposed<br />

shocks on all <strong>the</strong> parts of <strong>the</strong> food supply chains,<br />

simultaneously affecting farm production, food<br />

processing, transport, logistics, and final demand.<br />

Many farm owners in <strong>the</strong> Kenema District<br />

reported high rates of worker absences. For example,<br />

farm worker availability was reduced by up<br />

to 35% among <strong>the</strong> kola nut producers in <strong>the</strong> regions<br />

of <strong>the</strong> country worst hit by Covid-19.<br />

The government made encouraging steps to<br />

allow <strong>the</strong> agriculture sector to continue to operate<br />

during lockdowns and movement restrictions,<br />

including recognising agriculture as an essential<br />

service. But <strong>the</strong>re was a lot of uncertainty over<br />

what was allowed and what wasn’t.<br />

Shishir (India): As <strong>the</strong> lockdown began it was<br />

about providing cooked meals for <strong>the</strong> hungry.<br />

Mumbai was in economic shutdown. Kitchens<br />

were shut, which meant no manpower. Borders<br />

were shut, which meant procurement of raw material<br />

for cooking was a challenge. To add to it, <strong>the</strong><br />

virus was spreading fast, which meant <strong>the</strong>re was<br />

no one to transport or deliver anything.<br />

Cherrie (Philippines): Logistics were not available.<br />

So if you got a truck to drive your produce<br />

to <strong>the</strong> city, <strong>the</strong>re was no driver. They were all<br />

afraid to drive <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> mountains to Metro Manila,<br />

which is <strong>the</strong> central business district of <strong>the</strong><br />

Philippines, composed of 16 mega cities, with a<br />

population of around 13 million people. They were<br />

afraid that <strong>the</strong>y would bring <strong>the</strong> virus back to <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

community. So it was a nightmare. If you go to a<br />

supermarket it takes two hours minimum of your<br />

14 15

WHERE THE LEAVES FALL<br />

WHERE THE LEAVES FALL<br />

time; you have to go through <strong>the</strong> line, following<br />

<strong>the</strong> physical social distancing, and <strong>the</strong>re is only a<br />

limited selection.<br />

Adriana (Colombia): We saw a shortage in local<br />

produce like fruits, vegetables and staples such<br />

as plantain and cassava, which are grown by Indigenous<br />

farmers. They were on lockdown in <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

communities as a measure imposed by <strong>the</strong> Indigenous<br />

authorities to protect <strong>the</strong>ir people <strong>from</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> virus. Fish was also scarce since <strong>the</strong> lockdown<br />

started as fishermen <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> communities<br />

were not allowed to enter <strong>the</strong> city, and <strong>the</strong> main<br />

fish and farmers market in Leticia was shut down.<br />

How are you addressing <strong>the</strong> <strong>issue</strong>s raised by<br />

<strong>the</strong> pandemic?<br />

Cherrie (Philippines): We launched <strong>the</strong> Move<br />

<strong>Food</strong> initiative, bringing food <strong>from</strong> rural farms to<br />

Metro Manila. We helped <strong>the</strong> farmers bring <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

produce to <strong>the</strong> market, but ra<strong>the</strong>r than restaurants,<br />

<strong>the</strong> markets were now households or individuals.<br />

So we created an online ordering system<br />

for <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

Alpha (Trinidad and Tobago): We started a<br />

movement called Plant Yuh Plate, literally planting<br />

what you want to consume on your plate. We<br />

started providing seeds and seedlings, and soil<br />

and growboxes. It generated revenue as well as<br />

starting to build a community.<br />

Based on <strong>the</strong> food we have on <strong>the</strong> farm, and in<br />

collaboration with neighbouring farmers, we also<br />

developed a project called Dash-een Yuh Doorstep<br />

market (dasheen is a tropical plant that produces<br />

edible corns), which is essentially a food<br />

box that is delivered to your doorstep, focused<br />

especially on <strong>the</strong> elderly people in <strong>the</strong> community,<br />

because <strong>the</strong>y are <strong>the</strong> most vulnerable ones<br />

and <strong>the</strong>y don’t want to come out to <strong>the</strong> market.<br />

Adriana (Colombia): Before <strong>the</strong> national lockdown<br />

was imposed, foreseeing <strong>the</strong> food-related<br />

<strong>issue</strong>s that it would create in <strong>the</strong> region, Hábitat<br />

Sur and La Confianza (our family’s company) partnered<br />

to start a food security initiative we called<br />

La Cosecha - Trueque Amazónico (<strong>the</strong> harvest -<br />

Amazonian barter). The main aim of this initiative<br />

was to guarantee local food security.<br />

Shishir (India): Project Mumbai has been at <strong>the</strong><br />

forefront of <strong>the</strong> Covid-19 fight in Mumbai and this<br />

region. What started out as a volunteer-driven<br />

support to provide meals, medicines and groceries<br />

to senior citizens living alone, soon also led<br />

to providing cooked meals to doctors and hospital<br />

kitchens of all <strong>the</strong> frontline hospitals - almost<br />

1,500 a day.<br />

Project Mumbai also provided grocery kits to<br />

over 20,000 families, and we co-founded a citizen-driven<br />

mission to provide cooked meals to<br />

<strong>the</strong> increasing numbers of hungry people. The initiative,<br />

which is called Khaanachahiye, has at last<br />

count provided over 4,500,000 meals across <strong>the</strong><br />

Mumbai metropolitan region.<br />

Raúl (Mexico): Our main task, during <strong>the</strong> pandemic,<br />

was how to be an alternative for those people<br />

who were not going out, how can we get to <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

houses. So we targeted <strong>the</strong> middle classes with<br />

food delivery to <strong>the</strong>ir houses and <strong>from</strong> collection<br />

points. And for <strong>the</strong> lower classes, we sold in <strong>the</strong><br />

public market.<br />

Samuel (US): I am currently in talks with Rethink<br />

<strong>Food</strong>, working to take leftover food <strong>from</strong> restaurants<br />

and stores, <strong>from</strong> which <strong>the</strong>ir chefs create a<br />

delicious recipe, and <strong>the</strong>ir cooks prepare those<br />

meals to distribute each week. I am looking to<br />

contribute high nutrient microgreens and herbs<br />

to use for <strong>the</strong> cooking. They distribute hundreds<br />

of meals each week to low-income populations<br />

throughout Brooklyn.<br />

Jim (UK): When Covid-19 came along, I thought:<br />

“There are a lot of empty back yards out <strong>the</strong>re, I<br />

wonder if I could do something useful with raised<br />

beds?” So I made 10 of <strong>the</strong>m and went round<br />

<strong>the</strong> neighbours and asked <strong>the</strong>m if <strong>the</strong>y wanted<br />

a hand to sort out <strong>the</strong>ir patches. It improved <strong>the</strong><br />

profile of our expertise and helped our neighbours<br />

realise <strong>the</strong>ir ability to grow food. It took<br />

on a life of its own and our neighbours are now<br />

growing <strong>the</strong>ir own vegetables to supplement<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir consumption.<br />

PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF COLECTIVO AHUEJOTE.<br />

16 17

WHERE THE LEAVES FALL<br />

RESETTING GLOBAL FOOD SYSTEMS<br />

2.<br />

5.<br />

1.<br />

4.<br />

3.<br />

PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF COLECTIVO AHUEJOTE (1 & 7), PROJECT MUMBAI (2), SAMUEL’S FOOD GARDENS (3 & 6), AGREA (4), HÁBITAT SUR (5), WHYFARM (8).<br />

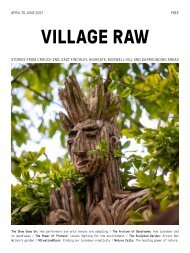

Opening image: Preparing a<br />

mud nursery bed at Colectivo<br />

Ahuejote, Mexico.<br />

Double page spread: St Raphael<br />

Edible Garden in Brent, UK.<br />

Previous page: A chinampa<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Xochimilco lake area<br />

to <strong>the</strong> south of Mexico City.<br />

These pages: 1 & 7 - Colectivo<br />

Ahuejote, Mexico; 2 - Project<br />

Mumbai, India; 3 & 6 - Samuel’s<br />

<strong>Food</strong> Gardens, US; 4 - AGREA,<br />

Philippines; 5 - Hábitat Sur,<br />

Colombia; 8 - WhyFarm, Trinidad<br />

and Tobago.<br />

6.<br />

8.<br />

7.<br />

18 19

WHERE THE LEAVES FALL<br />

RESETTING GLOBAL FOOD SYSTEMS<br />

PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF SLOW FOOD INTERNATIONAL, © PAULO VIESI (THIS PAGE AND NEXT PAGE).<br />

Adriana (Colombia): In <strong>the</strong> first week of <strong>the</strong> lockdown,<br />

my bro<strong>the</strong>r took a group of workers, fully<br />

equipped with protective gear, and a truck full<br />

of non-perishable food and personal and home<br />

cleaning products, and drove to <strong>the</strong> fur<strong>the</strong>st Indigenous<br />

settlement that can be accessed by<br />

land. We had previously coordinated with <strong>the</strong> Indigenous<br />

leaders, so when we arrived, dozens of<br />

families were already waiting with bags full of lemons,<br />

oranges, yuca, plantains, bananas, papayas<br />

and many o<strong>the</strong>r fruits to be exchanged for what<br />

we had brought. No money was involved. We mutually<br />

agreed on <strong>the</strong> value of each product to be<br />

bartered and we used our own currency, which<br />

we call semillas (seeds), to facilitate <strong>the</strong> exchange.<br />

Then in Bogota, we set up a door-to-door delivery<br />

system to bring baskets of fresh produce to<br />

families in <strong>the</strong> city, encouraging <strong>the</strong>m to eat local<br />

and to support Amazon farmers. By leveraging<br />

donations <strong>from</strong> different sources we were able to<br />

give <strong>the</strong> baskets to <strong>the</strong> most vulnerable families<br />

in <strong>the</strong> city, a side of <strong>the</strong> initiative we called La Cosecha<br />

Solidaria (<strong>the</strong> solidarity harvest). Through<br />

this system we delivered more than 4,000 food<br />

baskets to families during <strong>the</strong> quarantine.<br />

Raúl (Mexico): We cannot compete with a Walmart,<br />

but we tried to be an alternative in terms<br />

of logistics, because people wanted grocery<br />

delivery, and an alternative in sales. Through<br />

WhatsApp groups we have built a business sales<br />

programme. When <strong>the</strong> restrictions got really<br />

tough in April, May, and June, <strong>the</strong> sales went up<br />

420% for three months.<br />

Cherrie (Philippines): We used Viber, a mobile<br />

messaging service, to work with people who had<br />

access to <strong>the</strong>ir community Viber group. And most<br />

of <strong>the</strong> time <strong>the</strong>se Viber groups, for example <strong>the</strong><br />

one in our village, were around 800 household<br />

members, and we sold <strong>the</strong>re. So during <strong>the</strong> pandemic,<br />

each village or each subdivision of apartments<br />

developed a Viber group, or a Whatsapp<br />

group, or a Facebook group.<br />

And <strong>the</strong>se groups were like an online marketplace:<br />

someone was selling meat, someone was<br />

selling cakes, everyone was in <strong>the</strong>ir house, everyone<br />

was sharing recipes, everyone was cooking.<br />

Someone was even selling alcohol and masks. It<br />

was like a marketplace put toge<strong>the</strong>r by different<br />

households. Instead of going down <strong>the</strong> department<br />

store or supermarket, you just needed to<br />

message your Viber group and <strong>the</strong>y delivered to<br />

you. It was more of a village, or community-based<br />

ecosystem, that’s happening: a village industry.<br />

Alpha (Trinidad and Tobago): We created a<br />

WhatsApp group to reach people. Plant Yuh<br />

Plate became a big community in our WhatsApp<br />

group. It was created for beginners, people with<br />

an interest in planting but no clue how to do it.<br />

We have one or two experts in <strong>the</strong> group, actual<br />

agronomists, so <strong>the</strong>y provide really good sound<br />

information. We exchange knowledge, exchange<br />

information, exchange produce - we barter.<br />

Cherrie (Philippines): Ordering online was easy,<br />

but bringing <strong>the</strong> food was difficult. We were hustling<br />

to bring <strong>the</strong> produce in 12 hours to Metro Manila<br />

to <strong>the</strong> customers who needed it, but with this<br />

initiative we saved around 173,000 kilos of fruit<br />

and vegetables, helping around 11,000 farmers,<br />

and feeding around 68,000 households. If you<br />

think <strong>the</strong> average household in <strong>the</strong> Philippines<br />

is around seven people, <strong>the</strong>n that’s almost half a<br />

million people that we fed with fresh produce. We<br />

also donated to community kitchens that cooked<br />

for front liners, so we fed around 4,000 doctors,<br />

nurses, guards, and hospital staffers.<br />

Adriana (Colombia): As we continued visiting<br />

communities every week, more families <strong>from</strong><br />

more communities joined, getting to <strong>the</strong> point<br />

where around 1,000 families <strong>from</strong> around ten different<br />

Indigenous communities were participating<br />

in <strong>the</strong> barter every month. These interactions<br />

created a beautiful bond of trust between us and<br />

community members, as our only commitment<br />

was to be <strong>the</strong>re every week for each o<strong>the</strong>r, and<br />

our only tie was our word.<br />

Alpha (Trinidad and Tobago): With <strong>the</strong> Dash-een<br />

Yuh Doorstep market, a lot of <strong>the</strong> elderly folks,<br />

who are <strong>the</strong> clients, rated our delivery service, so<br />

it was just an interaction, but I believe in giving<br />

people more value. Sometimes you went to drop<br />

20 21

WHERE THE LEAVES FALL<br />

RESETTING GLOBAL FOOD SYSTEMS<br />

Previous page: Farmer<br />

and primary school teacher<br />

Mustapha Moigua harvesting<br />

<strong>the</strong> kola nut <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cola<br />

nitida tree in <strong>the</strong> Kenema<br />

District of Sierra Leone.<br />

This page: Kola nuts being<br />

prepared. After <strong>the</strong> nuts are<br />

removed <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> husks<br />

<strong>the</strong>y are soaked in water<br />

for about 24 hours to<br />

soften <strong>the</strong> skin, which is<br />

<strong>the</strong>n removed by hand.<br />

Next page: St Raphael’s<br />

Edible Garden.<br />

off a bag of food to an elderly person and <strong>the</strong>y<br />

may just have been <strong>the</strong>re, no one to talk to, and<br />

while you might have been busy <strong>the</strong>y may have<br />

started conversations and you just put a smile on<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir face. So we provided food, we provided a<br />

smile, and I think that added more to <strong>the</strong>ir day.<br />

What does <strong>the</strong> future hold for your community<br />

and <strong>the</strong> world at large?<br />

Fatmata: In Sierra Leone, countless people are<br />

struggling to make it through <strong>the</strong> day. That has<br />

always been true, and it remains true now; this<br />

virus has categorically not affected all people<br />

equally. The most vulnerable are those living in<br />

poverty and those forced to leave <strong>the</strong>ir homes<br />

because of conflict, disaster, or <strong>the</strong> lack of decent<br />

work locally.<br />

At <strong>the</strong> same time, <strong>the</strong> pandemic has shown us<br />

that pathways to a better future do exist - a future<br />

in which we can work toge<strong>the</strong>r to build a different<br />

kind of society and find ways of protecting our<br />

planet instead of harming it.<br />

Cherrie (Philippines): During <strong>the</strong> lockdown a lot<br />

of our movers, who helped us sell fruit and vegetables<br />

in <strong>the</strong>ir complexes, messaged us saying<br />

it’s <strong>the</strong> first time <strong>the</strong>y’ve got to know <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

neighbours, so we are going back to <strong>the</strong> basics<br />

of knowing each o<strong>the</strong>r, and taking care of our<br />

neighbours, sharing with our neighbours what<br />

our grandmo<strong>the</strong>r is cooking or selling.<br />

The urban community is getting stronger, and<br />

<strong>the</strong>re is huge recognition of how valuable agriculture<br />

is, that agriculture is <strong>the</strong> mo<strong>the</strong>r of all industries.<br />

You cannot forget agriculture to grow your<br />

own economy as a country. And to achieve food<br />

security globally I would encourage everyone to<br />

learn how to enjoy growing your own food.<br />

Adriana (Colombia): I think <strong>the</strong> world has been<br />

rapidly changing for decades now. This pandemic<br />

is just ano<strong>the</strong>r ring of <strong>the</strong> bell to make us wake up<br />

and see all <strong>the</strong> damage human activities have cost<br />

<strong>the</strong> environment - making us realise that everything<br />

we do to our planet we do it to ourselves.<br />

<strong>Food</strong> sovereignty is <strong>the</strong> only way to untangle<br />

ourselves and our communities <strong>from</strong> that web.<br />

If you cannot grow your own food <strong>the</strong>n eat what<br />

is locally produced, know where your food comes<br />

<strong>from</strong>, support small famers even when <strong>the</strong>ir tomatoes<br />

might not look as big, red and shiny as<br />

<strong>the</strong> ones produced in laboratories. But, be assured,<br />

<strong>the</strong>y will be more delicious, healthier, and<br />

your purchase will be helping to sustain a family.<br />

Fatmata (Sierra Leone): At <strong>the</strong> heart of food<br />

sovereignty lies radical egalitarianism. The attainment<br />

of such an objective entails building a<br />

society in which <strong>the</strong> equality-distorting effects of<br />

sexism, patriarchy, racism and class power have<br />

been eradicated and in which democracy can<br />

truly operate.<br />

Jim (UK): People in England need to realise that<br />

getting mangetout <strong>from</strong> South Africa, for example,<br />

cannot be taken for granted. It continues <strong>the</strong><br />

poverty cycle because <strong>the</strong> profit goes to whoever<br />

is selling <strong>the</strong> product on <strong>the</strong> shelf, <strong>the</strong> fuel and<br />

transport, and <strong>the</strong> people at source are probably<br />

paid very little.<br />

In that sense it’s criminal because people can<br />

easily grow on a seasonal basis on <strong>the</strong>ir front<br />

door. And people need to realise that to pick<br />

something <strong>from</strong> a vine, give it a wipe and put it<br />

in your mouth does not kill you. But people are<br />

very reticent to get <strong>the</strong>ir hands dirty. We need to<br />

change <strong>the</strong> perspective on that.<br />

Alpha (Trinidad and Tobago): Every location,<br />

every locality, should focus on <strong>the</strong>ir local farmers.<br />

A local production would be way better for gaps<br />

in food security in <strong>the</strong> world and, of course, ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

aspect of food security that people often<br />

forget is nutrition. We need to understand and go<br />

back to making food our medicine, and not medicine<br />

our food. It’s about changing those conversations<br />

into action. Now is <strong>the</strong> time for less talk,<br />

more walk.<br />

Raúl (Mexico): The pandemic showed that farm<br />

to table is pretty easy to do, because all those<br />

factories with all that manufacturing that makes<br />

your food live longer, <strong>the</strong>y are all closed, so<br />

<strong>the</strong>re’s nowhere to go but <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> farm straight<br />

to your table.<br />

22 23

WHERE THE LEAVES FALL<br />

WHERE THE LEAVES FALL<br />

Cherrie (Philippines): Hopefully now we can consolidate<br />

<strong>the</strong> system we developed in lockdown for<br />

<strong>the</strong> farming communities to unite so we can serve<br />

<strong>the</strong> demands of <strong>the</strong>se growing urban communities.<br />

So what I’m looking for after this, hopefully, is<br />

that <strong>the</strong> rural community will also respond to that.<br />

Samuel (US): New York City’s future is complicated,<br />

as is <strong>the</strong> case for any coastal city or giant city<br />

with little open land still available. The reality is that<br />

cities in general have a drastic imbalance in pervious<br />

to impervious land ratios. The historical act of<br />

paving over large tracts of natural ground and creating<br />

countless forms of barriers against natural<br />

water and resource flow has led to <strong>the</strong> expensive<br />

<strong>issue</strong>s of flooding, urban heat island, pollution of<br />

air, water, and soil, and great loss of biodiversity.<br />

If cities want to achieve goals like New York<br />

City’s zero waste by 2030, urban-heat island solutions<br />

by 2040, or no more fossil fuels by 2050, it<br />

is vital that <strong>the</strong>y look to rezone to allow for more<br />

access to land, go all-in with investing in urban<br />

ecological re-integration in general, and rapidly<br />

scale localised food systems.<br />

Shishir (India): I think <strong>the</strong> way forward is a more<br />

respectable public-private-partnership [between<br />

government and civic society]. The need is for <strong>the</strong><br />

state to respect <strong>the</strong> role of <strong>the</strong> non-profit sector.<br />

During our experiences distributing food through<br />

<strong>the</strong> Covid-19 lockdown, we realised our goal to<br />

im prove <strong>the</strong> crisis management infrastructure in<br />

Mumbai, and that it could be achieved working<br />

alongside <strong>the</strong> Municipal Corporation of Greater<br />

Mumbai and <strong>the</strong> State Government of Maharashtra.<br />

There is a lack of actionable data about <strong>the</strong><br />

severity of hunger in Mumbai. So we will be conducting<br />

data analyses to generate a “hunger map”.<br />

It is <strong>the</strong> first project of its kind in this country, and<br />

we will design interventions based on our analyses,<br />

to ensure an adequate level of nutrition in <strong>the</strong><br />

population and ensure effective implementation<br />

of government policies aimed at reducing poverty<br />

and vulnerability in urban poor households.<br />

Adriana (Colombia): Many small changes are<br />

feasible at a larger scale. For example, if <strong>the</strong> government<br />

is already investing in large housing projects<br />

for <strong>the</strong> most vulnerable families, why not try,<br />

for instance, organising <strong>the</strong> available space so<br />

that each family can have a small garden to plant<br />

some of <strong>the</strong>ir food. This would have a huge impact<br />

on <strong>the</strong> local food system.<br />

Jim (UK): If more people took up gardening that<br />

would be a step in <strong>the</strong> right direction. When you<br />

get your hands dirty and work on a micro scale<br />

you are going to see that it is making a difference.<br />

Everybody needs to be inspired to take that first<br />

step. Individuals making small differences that<br />

impact <strong>the</strong>ir local community will help to bring<br />

change over time.<br />

Adriana (Colombia): I believe first individuals,<br />

<strong>the</strong>n families, neighbourhoods, schools, small<br />

towns and communities can commit to a more<br />

sustainable and harmonious way of inhabiting<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir territories. Introducing changes in <strong>the</strong> way<br />

we build our home, produce our food and energy,<br />

nourish <strong>the</strong> soil, and treat our water and our<br />

waste, to set an example that shows o<strong>the</strong>rs that<br />

<strong>the</strong>se small changes are possible in our context<br />

and with resources that are available locally for<br />

everyone who wants to implement <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

Raúl (Mexico): In Mexico City, <strong>the</strong> three most rural<br />

boroughs are really disconnected <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

centre. We need to bring <strong>the</strong> citizens toge<strong>the</strong>r<br />

so <strong>the</strong>y can enjoy <strong>the</strong>se city dynamics, and not<br />

wait for <strong>the</strong> tomato that comes <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

states, because we have <strong>the</strong> tomato here. It’s a<br />

clichéd statement, but I always think that it’s real:<br />

act local, think global. Doing small changes in your<br />

own place, we can go bigger out <strong>the</strong>re.<br />

Cherrie (Philippines): For me, during this “new<br />

normal”, I want to say that we always focus on<br />

sustainability, but I guess resilience is more powerful.<br />

And to go to our resilience we need to be<br />

resilient as individuals, and that is really going<br />

back to <strong>the</strong> land, utilising our land properly, eating<br />

healthily <strong>from</strong> our own produce. But at <strong>the</strong> same<br />

time building that strong sense of community,<br />

because that’s what makes us survive.<br />

–<br />

Full interviews will be available on our website.<br />

PHOTOGRAPH BY ANGELES RODENAS.<br />

24 25

WHERE THE LEAVES FALL<br />

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE<br />

Also in<br />

this <strong>issue</strong>:<br />

In Favour of Life<br />

Drawing inspiration <strong>from</strong> Brazil’s Landless Workers’<br />

Movement, chef, author and food activist<br />

Bela Gil believes agroecology is key to averting<br />

climate change and ending food poverty.<br />

My Garden My Kingdom<br />

Syrian refugee Khadija Mura offers an account of<br />

life as a refugee and how <strong>the</strong> community garden<br />

became a vital source of nutritious food as <strong>the</strong><br />

Domiz 1 refugee camp in Iraq became isolated by<br />

<strong>the</strong> approach of <strong>the</strong> virus.<br />

Nature’s Agent<br />

We consider <strong>the</strong> agricultural legacy of 19th century<br />

agriculturalist George Washington Carver, a<br />

man who took his daily instructions <strong>from</strong> nature,<br />

and whose life and words remain relevant today.<br />

And <strong>the</strong> rest…<br />

This <strong>issue</strong> explores mutualist art practices, in<br />

which artists form a reciprocal relationship with<br />

non-humans. We also examine how colonial history<br />

has left a broken ecosystem in <strong>the</strong> mountains of<br />

Nilgiris in India, and how <strong>the</strong> same history has led<br />

to ancestral philosophies travelling across <strong>the</strong><br />

continents. We find that connections we share<br />

can reveal more commonality than difference.<br />

Three of <strong>the</strong>se stories have roots in India, and we<br />

invite you to muse on <strong>the</strong> connections and relationships<br />

between <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

Issue #5<br />

The latest <strong>issue</strong> focuses on <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>mes of water,<br />

technology, and cosmos. Features include how<br />

ice, traditionally a symbol of eternity and stasis,<br />

has become a metaphor for change and decay<br />

in contemporary art; John Francis Serwanga, <strong>the</strong><br />

World <strong>Food</strong> Programme’s hydroponics expert,<br />

tells us how hydroponics is transforming school<br />

gardens in Zambia; and science writer Jo Marchant<br />

describes <strong>the</strong> awe felt by astronauts looking<br />

back at earth and how most of us don’t confront<br />

our fear of <strong>the</strong> vast unknown in <strong>the</strong> same way.<br />

It also examines how <strong>the</strong> micro-photography of<br />

early 20th century naturalist and filmmaker F. Percy<br />

Smith revealed new ways of seeing everything<br />

<strong>from</strong> flowers to frogspawn.<br />

26 27