The Trumpet Newspaper Issue 564 (February 9 - 22 2022)

Burundi's vicious crackdown never ended

Burundi's vicious crackdown never ended

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

News<br />

FEBRUARY 9-<strong>22</strong> 20<strong>22</strong><br />

Burundi’s vicious crackdown<br />

never ended<br />

<strong>The</strong><strong>Trumpet</strong><br />

Page11<br />

Continued from Page 3<<br />

and President Évariste Ndayishimiye’s<br />

pursuit of reforms across multiple<br />

sectors.” In October, the EU indicated<br />

that even as it renewed targeted sanctions<br />

against some senior Burundian officials,<br />

it would also resume direct budgetary<br />

support to Burundi’s government.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se overtures toward a government<br />

that continues to torture and kill its own<br />

people risk emboldening Burundi’s<br />

leaders to crack down even harder on<br />

their opponents. Instead of hoping that<br />

the Burundian government will change<br />

its ways, the United States and the<br />

European Union should publicly push the<br />

country’s leaders to take concrete and<br />

measurable steps to improve their dire<br />

human rights record.<br />

False promises<br />

Burundi descended into chaos and<br />

violence in April 2015, after Nkurunziza<br />

announced a controversial bid for a third<br />

term in office, sparking months of<br />

protests and a failed coup attempt.<br />

Government security forces and members<br />

of the ruling party’s youth league, known<br />

as the Imbonerakure - meaning “those<br />

who see far” in the Kirundi language -<br />

arrested or shot protesters and critics. By<br />

mid-2015, hundreds of people had been<br />

killed, and almost all of Burundi’s<br />

opposition leaders, independent<br />

journalists, and civil society activists had<br />

fled the country. Some 400,000 people<br />

sought refuge in neighboring countries.<br />

In 2018, Nkurunziza unexpectedly<br />

announced that he would not seek<br />

reelection in 2020. Ndayishimiye, a<br />

former army general who was Secretary-<br />

General of the ruling party at the height<br />

of the crisis, became the party’s candidate<br />

for president, winning in an election<br />

marred by violence and allegations of<br />

rigging. In June 2020, two months before<br />

he was set to step down, Nkurunziza died<br />

suddenly under mysterious<br />

circumstances.<br />

Ndayishimiye was sworn in early<br />

during a hastily arranged ceremony.<br />

Although he had overseen the party while<br />

it committed grave human rights abuses,<br />

Ndayishimiye promised to promote<br />

political tolerance, make the justice<br />

system more impartial and fair, and hold<br />

accountable those responsible for past<br />

crimes.<br />

Ndayishimiye did release some<br />

human rights advocates and journalists<br />

from jail and lift some restrictions on the<br />

media and civil society, but his<br />

government continues to use repressive<br />

tactics against its opponents. Tony<br />

Germain Nkina, a lawyer and former<br />

human rights defender, was convicted on<br />

baseless charges of collaborating with<br />

rebels that were confirmed on appeal in<br />

September 2021. <strong>The</strong> government has<br />

also used arrest warrants, convictions in<br />

absentia, and life sentences against<br />

human rights defenders in exile to silence<br />

the country’s once-thriving human rights<br />

movement.<br />

“Our province has become a<br />

graveyard.”<br />

<strong>The</strong>n there are the killings. Carried<br />

out by security forces, Imbonerakure<br />

members, and other unknown<br />

perpetrators, they have sowed terror<br />

among the population. “Our province has<br />

become a graveyard,” one resident of<br />

Cibitoke told my colleagues and me last<br />

August. Another man said he witnessed<br />

four men in military attire beat to death<br />

Emmanuel Baransegeta, a 53-year-old<br />

fisherman, as he returned from work on<br />

the Rusizi River the evening of July 8,<br />

2021. Two days later on the banks of the<br />

river, residents found the body of a man<br />

who looked as if he had been beaten.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y said they believed he was<br />

Baransegeta, but the local authorities<br />

buried him without investigating the<br />

circumstances of his death or even trying<br />

to confirm his identity.<br />

For many, these killings evoke<br />

memories of Burundi’s violent past. <strong>The</strong><br />

banks of the Rusizi have historically been<br />

dumping grounds for bodies of people<br />

killed in political or ethnic strife. During<br />

Burundi’s brutal civil war, which raged<br />

from 1993 to 2009, an estimated 300,000<br />

people were killed in fighting that broke<br />

down largely along ethnic lines. Both the<br />

Tutsi-dominated military and the armed<br />

Hutu opposition forces committed<br />

serious war crimes, including killings and<br />

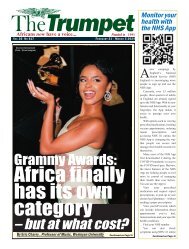

President Évariste Ndayishimiy<br />

rapes of civilians.<br />

Nkurunziza’s first term, from 2005 to<br />

2010, offered hope for a break with that<br />

history. A Hutu rebel leader during the<br />

war, he took office under a new<br />

constitution that guaranteed powersharing<br />

between Hutus and Tutsis and<br />

among political parties. Despite<br />

continued bouts of violence, the country<br />

achieved a degree of stability and made<br />

some progress toward peace,<br />

reconciliation, and economic<br />

development. It developed a burgeoning<br />

civil society and independent media<br />

landscape. But this fragile progress<br />

suffered serious setbacks during and after<br />

the 2010 elections as political tensions<br />

rose and security forces and armed<br />

opposition groups committed scores of<br />

killings. In Cibitoke, residents once again<br />

found mutilated bodies of opposition<br />

supporters near the river. Now, they are<br />

encountering them with appalling<br />

frequency.<br />

Dangerous gamble<br />

In September 2021, the UN<br />

Commission of Inquiry on Burundi,<br />

which has documented grave human<br />

rights violations in the country every year<br />

since its creation in 2016, presented its<br />

last report to the UN Human Rights<br />

Council. <strong>The</strong> Commission concluded that<br />

under Burundi’s new government, “no<br />

structural reform has been undertaken to<br />

durably improve the situation.” It<br />

expressed alarm about continuing human<br />

rights violations and the progressive<br />

erosion of the rule of law. Yet the Human<br />

Rights Council, in a resolution led by the<br />

EU and supported by the United States,<br />

ended the Commission’s mandate in<br />

favor of a Special Rapporteur with fewer<br />

resources to investigate human rights<br />

violations. <strong>The</strong> resolution claimed that<br />

progress “has been made in the field of<br />

human rights, good governance and the<br />

rule of law,” citing the limited, largely<br />

symbolic gestures by the Burundian<br />

government. Unsurprisingly, in<br />

December, Burundi’s Foreign Minister<br />

said it would “never” work with the<br />

Special Rapporteur.<br />

Ending the Commission’s mandate<br />

and lifting international sanctions and<br />

other punitive measures in the absence of<br />

real progress on human rights or<br />

democratic reforms is a dangerous<br />

gamble. <strong>The</strong> United States and the EU<br />

may hope that doing so will encourage<br />

reform, but it will more likely embolden<br />

human rights abusers who already<br />

operate with near-total impunity. To<br />

many victims of abuses, the willingness<br />

of Washington and Brussels to trust the<br />

same officials who have overseen the<br />

killing, disappearance, and brutal torture<br />

of thousands of people since 2015 is<br />

inexplicable - as is their silence in the<br />

face of persistent human rights violations<br />

under Ndayishimiye.<br />

<strong>The</strong> United States and the EU should<br />

publicly press the Burundian government<br />

to release all political prisoners, including<br />

Nkina, and overturn unfair convictions<br />

and drop arrest warrants against human<br />

rights activists and journalists in exile.<br />

<strong>The</strong> government can prove it is serious<br />

about reform by allowing the UN Special<br />

Rapporteur to access the country and by<br />

conducting credible investigations into<br />

killings, disappearances, and instances of<br />

torture. Any members of the security<br />

forces or Imbonerakure who are found to<br />

be responsible for these abuses should be<br />

immediately arrested and prosecuted.<br />

“Please, I am asking you to tell as<br />

many people as you can about what is<br />

going on here. <strong>The</strong> international<br />

community must know about these<br />

killings,” an official in Burundi’s<br />

National Defense Force told us. He spoke<br />

on the condition of anonymity, defying<br />

his superiors in order to call attention to<br />

the dead bodies he was regularly finding<br />

along the Rusizi. But the problem is not<br />

that the United States and the EU don’t<br />

know what is going in Burundi. <strong>The</strong><br />

problem is they are choosing to ignore it.<br />

Mausi Segun is the Executive<br />

Director (Africa) for Human Rights<br />

Watch.<br />

https://www.hrw.org/news/20<strong>22</strong>/02/0<br />

8/burundis-vicious-crackdown-neverended