Gastroenterology Today Spring 2022

Gastroenterology Today Spring 2022

Gastroenterology Today Spring 2022

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Volume 32 No. 1<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2022</strong><br />

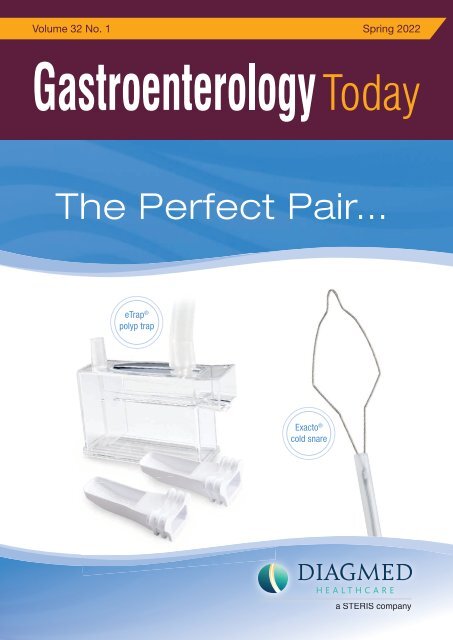

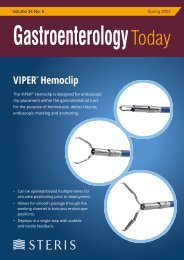

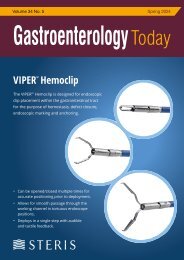

The Perfect Pair...<br />

eTrap ®<br />

polyp trap<br />

Exacto ®<br />

cold snare<br />

a STERIS company

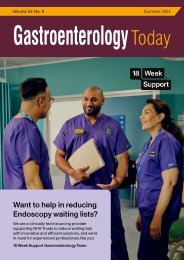

WITH YOUR HELP<br />

We’ve made<br />

<strong>Gastroenterology</strong> a true<br />

7 day NHS service<br />

Join forces with the UK’s largest campaign to see and<br />

treat those NHS patients who need you most. All working<br />

as part of an expert clinical team in outpatient clinics or<br />

undertaking Endoscopy procedures, getting the right care<br />

to those patiently waiting.<br />

Register your support or enquire below.<br />

Together, we can end the wait.<br />

www.ukmedinet.com

CONTENTS<br />

CONTENTS<br />

4 EDITORS COMMENT<br />

6 FEATURE Gastric polyps: a 10-year analysis of 18,496<br />

upper endoscopies<br />

14 FEATURE Endoscopic retrograde appendicitis therapy<br />

versus laparoscopic appendectomy versus open<br />

appendectomy for acute appendicitis: a pilot study<br />

22 FEATURE An extremely dangerous case of acute massive<br />

upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a case report<br />

26 NEWS<br />

31 COMPANY NEWS<br />

This issue edited by:<br />

Hesam Ahmadi Nooredinvand<br />

c/o Media Publishing Company<br />

Greenoaks<br />

Lockhill<br />

Upper Sapey, Worcester, WR6 6XR<br />

ADVERTISING & CIRCULATION:<br />

Media Publishing Company<br />

Greenoaks, Lockhill<br />

Upper Sapey, Worcester, WR6 6XR<br />

Tel: 01886 853715<br />

E: info@mediapublishingcompany.com<br />

www.MediaPublishingCompany.com<br />

PUBLISHING DATES:<br />

March, June, September and December.<br />

COPYRIGHT:<br />

Media Publishing Company<br />

Greenoaks<br />

Lockhill<br />

Upper Sapey, Worcester, WR6 6XR<br />

COVER STORY<br />

At Diagmed Healthcare our mission is to provide our Customers with innovative products<br />

to better diagnose, prevent, and treat disease of the gastrointestinal tract. From advanced<br />

polypectomy and GI emergency devices, to procedural infection prevention solutions we<br />

are continuously developing new innovations and technologies.<br />

The perfect pair…<br />

The Exacto ® Cold Snare and eTrap ® Polyp Trap support resection and retrieval of<br />

diminutive polyps.<br />

Clinically proven to achieve a signifi cantly high rate of complete resection, the Exacto cold<br />

snare offers control and placement for a precise, clean cut 1,2 . The Exacto snare supports<br />

the cold snare polypectomy technique and can be used to resect a variety of different<br />

types of polyps in multiple sizes (including diminutive and large) and features the following:<br />

• Features a shield shape design that maximises its width for control and placement<br />

during cold snare polypectomy<br />

• 33% thinner wire diameter than traditional braided wires allowing for stiffness and<br />

fl exibility due to its thin, seven braided wire confi guration<br />

• Reduces polyp “fl y away” from the resection site making it possible tocollect specimen<br />

for pathology 2<br />

Designed by GI nurses, the eTrap polyp trap supports retrieval of multiple specimens,<br />

while safeguarding clinicians and nurses from unnecessary exposure to biomaterials.<br />

• Two removable polyp specimen collector strainer trays allowing for retrieval of multiple<br />

polyps with uninterrupted suction<br />

• A clear magnifying window allows direct visualization of the collected specimen<br />

• A measurement guide designed to aid in specimen sizing<br />

For more information on our complete offering of polypectomy solutions, visit<br />

diagmed.healthcare today.<br />

1) Horiuchi A, Hosoi K. “Prospective, Randomized Comparison of 2 Methods of Cold Snare Polypectomy for Small<br />

Colorectal Polyps.” Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (2015): 1-7.<br />

2) Din S, Ball A. “Cold Snare Polypectomy: Does Snare Type Infl uence Outcomes?” Digestive Endoscopy (2015): 1-6.<br />

PUBLISHERS STATEMENT:<br />

The views and opinions expressed in<br />

this issue are not necessarily those of<br />

the Publisher, the Editors or Media<br />

Publishing Company.<br />

Next Issue Summer <strong>2022</strong><br />

Subscription Information – <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2022</strong><br />

<strong>Gastroenterology</strong> <strong>Today</strong> is a quarterly<br />

publication currently sent free of charge to<br />

all senior qualifi ed Gastroenterologists in<br />

the United Kingdom. It is also available<br />

by subscription to other interested individuals<br />

and institutions.<br />

UK:<br />

Individuals - £24.00 incl postage<br />

Commercial Organistations - £48.00 incl postage<br />

Overseas:<br />

£72.00 incl Air Mail postage<br />

We are also able to process your<br />

subscriptions via most major credit<br />

cards. Please ask for details.<br />

Cheques should be made<br />

payable to MEDIA PUBLISHING.<br />

Designed in the UK by me&you creative<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SPRING <strong>2022</strong><br />

3

EDITORS COMMENT<br />

EDITORS COMMENT<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SPRING <strong>2022</strong><br />

“COVID-19<br />

pandemic<br />

appears to<br />

be shifting<br />

towards an<br />

endemic<br />

disease<br />

with most<br />

healthcare<br />

services<br />

gradually<br />

returning<br />

to normal,<br />

the positive<br />

impact of<br />

which will<br />

certainly<br />

be felt by<br />

patients.”<br />

Disruption to the health service during the last couple of years as a result of the<br />

pandemic has undoubtedly had a detrimental impact on certain aspects of patient care.<br />

A recent healthcare survey by Crohn’s and Colitis UK highlights how a delay in diagnosis,<br />

difficulty in accessing specialist advice and disruption to surgery and endoscopy services<br />

have had a negative impact on both physical and mental wellbeing of many patients with<br />

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD).<br />

There is however light at the end of the tunnel. COVID-19 pandemic appears to be shifting<br />

towards an endemic disease with most healthcare services gradually returning to normal,<br />

the positive impact of which will certainly be felt by patients.<br />

We have a number of fascinating articles included in this <strong>Spring</strong> edition of <strong>Gastroenterology</strong><br />

<strong>Today</strong> including,<br />

• Role of Endoscopic Retrograde Appendicitis Therapy (ERAT) as an alternative to surgical<br />

appendectomy in acute uncomplicated appendicitis<br />

• Scientists in Munich explore the mechanism that triggers problematic interaction between<br />

intestinal bacteria and cells in intestinal mucus layer in patients with IBD which could offer<br />

targets for development of new drug therapy<br />

• Coeliac UK highlights the role of the Rare Disease Collaborative Network in supporting<br />

with diagnosis and management of patients with refractory coeliac disease<br />

• Retrospective study looking at the frequency of gastric polyps and their association with<br />

certain factors<br />

• An interesting case report of massive gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to a fish bone!<br />

Hesam Ahmadi Nooredinvand,<br />

St George’s Hospital<br />

4

Prescribe Entocort ® CR by brand<br />

instead of prednisolone<br />

• Rapid induction of remission from 2 weeks with<br />

Entocort ® CR* 1<br />

• ~50% fewer corticosteroid-associated side effects<br />

than prednisolone 2,3<br />

• Unlike Entocort ® CR, prednisolone increases<br />

susceptibility to, and severity of, infections †2,4<br />

• Entocort ® CR is the only controlled-release<br />

oral budesonide indicated for Crohn’s disease 2<br />

Help keep your Crohn’s patients out of hospital...<br />

...and where they want to be<br />

*Remission was defined as a score of ≤150 on the Crohn’s disease activity index.<br />

†Entocort ® CR should be used with caution in patients with infections where the use of glucocorticosteroids may have unwanted effects. 2<br />

ENTOCORT CR 3mg Capsules (budesonide) - Prescribing<br />

Information<br />

Please consult the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) for full<br />

prescribing Information<br />

Presentation: Hard gelatin capsules for oral administration with an<br />

opaque, light grey body and an opaque, pink cap marked CIR 3mg in black<br />

radial print. Contains 3mg budesonide. Indications: Induction of remission<br />

in patients with mild to moderate Crohn’s disease affecting the ileum and/or<br />

the ascending colon. Induction of remission in patients with active<br />

microscopic colitis. Maintenance of remission in patients with microscopic<br />

colitis. Dosage and administration: Active Crohn’s disease (Adults): 9mg<br />

once daily in the morning for up to eight weeks. Full effect achieved in 2-4<br />

weeks. When treatment is to be discontinued, dose should normally be<br />

reduced in final 2-4 weeks. Active microscopic colitis (Adults): 9mg once<br />

daily in the morning. Maintenance of microscopic colitis (Adults): 6mg once<br />

daily in the morning, or the lowest effective dose. Paediatric population: Not<br />

recommended. Older people: No special dose adjustment recommended.<br />

Swallow whole with water. Do not chew. Contraindications:<br />

Hypersensitivity to the active substance or any of the excipients. Warnings<br />

and Precautions: Side effects typical of corticosteroids may occur. Visual<br />

disturbances may occur. If a patient presents with symptoms such as<br />

blurred vision or other visual disturbances they should be considered for<br />

referral to an ophthalmologist for evaluation of the possible causes.<br />

Systemic effects may include glaucoma and when prescribed at high doses<br />

for prolonged periods, Cushing’s syndrome, adrenal suppression, growth<br />

retardation, decreased bone mineral density and cataract. Caution in<br />

patients with infection, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis,<br />

peptic ulcer, glaucoma or cataracts or with a family history of diabetes or<br />

glaucoma. Particular care in patients with existing or previous history of<br />

severe affective disorders in them or their first degree relatives. Caution<br />

when transferring from glucocorticoid of high systemic effect to Entocort<br />

CR. Chicken pox and measles may have a more serious course in patients<br />

on oral steroids. They may also suppress the HPA axis and reduce the stress<br />

response. Reduced liver function may increase systemic exposure. When<br />

treatment is discontinued, reduce dose over last 2-4 weeks. Concomitant<br />

use of CYP3A inhibitors, such as ketoconazole and cobicistat-containing<br />

products, is expected to increase the risk of systemic side effects and<br />

should be avoided unless the benefits outweigh the risks. Excessive<br />

grapefruit juice may increase systemic exposure and should be avoided.<br />

Patients with fructose intolerance, glucose-galactose malabsorption or<br />

sucrose-isomaltase insufficiency should not take Entocort CR. Monitor<br />

height of children who use prolonged glucocorticoid therapy for risk of<br />

growth suppression. Interactions: Concomitant colestyramine may<br />

reduce Entocort CR uptake. Concomitant oestrogen and contraceptive<br />

steroids may increase effects. CYP3A4 inhibitors may increase systemic<br />

exposure. CYP3A4 inducers may reduce systemic exposure. May cause low<br />

values in ACTH stimulation test. Fertility, pregnancy and lactation: Only<br />

to be used during pregnancy when the potential benefits to the mother<br />

outweigh the risks for the foetus. May be used during breast feeding.<br />

Adverse reactions: Common: Cushingoid features, hypokalaemia,<br />

behavioural changes such as nervousness, insomnia, mood swings and<br />

depression, palpitations, dyspepsia, skin reactions (urticaria, exanthema),<br />

muscle cramps, menstrual disorders. Uncommon: anxiety, tremor,<br />

psychomotor hyperactivity. Rare: aggression, glaucoma, cataract, blurred<br />

vision, ecchymosis. Very rare: Anaphylactic reaction, growth retardation.<br />

Prescribers should consult the summary of product characteristics in<br />

relation to other adverse reactions. Marketing Authorisation Numbers,<br />

Package Quantities and basic NHS price: PL 36633/0006. Packs of 50<br />

capsules: £37.53. Packs of 100 capsules: £75.05. Legal category: POM.<br />

Marketing Authorisation Holder: Tillotts Pharma UK Ltd, The Stables,<br />

Wellingore Hall, Wellingore, Lincoln, LN5 0HX. Date of preparation of PI:<br />

February 2020<br />

Adverse events should be reported.<br />

Reporting forms and information can be<br />

found at https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk.<br />

Adverse events should also be reported to<br />

Tillotts Pharma UK Ltd. Tel: 01522 813500.<br />

References: 1. Campieri M et al. Gut 1997; 41: 209–214. 2. Entocort ®<br />

CR 3 mg capsules – Summary of Product Characteristics. 3. Rutgeerts<br />

P et al. N Engl J Med 1994; 331: 842–845. 4. Prednisolone 5 mg tablets<br />

– Summary of Product Characteristics.<br />

Date of preparation: August 2021. PU-00572.

FEATURE<br />

GASTRIC POLYPS: A 10-YEAR<br />

ANALYSIS OF 18,496 UPPER<br />

ENDOSCOPIES<br />

Haythem Yacoub 1,2* , Norsaf Bibani 1,2 , Mériam Sabbah 1,2 , Nawel Bellil 1,2 , Asma Ouakaa 1,2 , Dorra Trad 1,2 and Dalila Gargouri 1,2<br />

Yacoub et al. BMC <strong>Gastroenterology</strong> (<strong>2022</strong>) 22:70 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-022-02154-8<br />

Abstract<br />

Background/aims<br />

Gastric polyps (GPs) are usually asymptomatic lesions of the upper<br />

gastrointestinal tract observed in 1–3% of esophagogastroduodenoscopies<br />

(EGD). Most GPs are benign. The aim of this study was to precise the<br />

frequency of different types of gastric polyps in our population, and to<br />

analyze their possible association with other factors.<br />

Materials and methods<br />

A total of 18,496 consecutive patients undergoing EGD over a<br />

10-year period (between 2007 and 2018) in a tertiary hospital were<br />

retrospectively reviewed. Eighty-six patients diagnosed with gastric<br />

polyps were analysed. Demographics, medical history of the patients,<br />

and indication for gastroscopy were collected. Morphological,<br />

histological characteristics of polyps, and therapeutic management data<br />

were also collected.<br />

fundic gland are the most common in our country. The high frequency of<br />

Helicobacter pylori infection in our patients and in our area may explain<br />

the high frequency of HP.<br />

Keywords<br />

Stomach, Polyp, Polypectomy, Endoscopic mucosal resection<br />

Introduction<br />

Gastric polyps (GPs) are defined as luminal projections above<br />

the plane of the adjacent mucosa regardless of its histological<br />

type [1]. Gastric polyps are usually discovered incidentally during<br />

esophagogastroduodenoscopies (EGD) and their prevalence is<br />

estimated from 0.5 to 23% of all upper gastrointestinal endoscopies [2].<br />

Some polyps can occasionally present with bleeding, anemia, or gastric<br />

outlet obstruction [3].<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SPRING <strong>2022</strong><br />

Results<br />

GPs were found in 86 out of 18,496 (0.46%) reviewed EGD,<br />

corresponding to a total of 141 polyps. There were 64 female (74.4%)<br />

and 22 male patients (25.6%) with a sex ratio (M/F) of 0.34. The<br />

average age was 58.1 years. One hundred and forty one polyps were<br />

included, and histopathology was obtained on 127 GPs. The most<br />

common location was the fundus (59.6%) and 48.9% were smaller than<br />

5 mm. The polyp was unique in 75.6% of cases. According to Paris<br />

classification, 80% of the polyps were sessile (Is). Hyperplastic polyps<br />

were the most common (55.9%), followed by sporadic fundic gland<br />

polyps observed in 23 patients (18.1%), 7 (5.5%) were adenomas and<br />

4 (3.1%) were neuroendocrine tumors type 1. The following factors<br />

were associated with hyperplastic polyps: anemia (p =0.022), single<br />

polyp (p=0.025) and size≥5 mm (p=0.048). Comparing hyperplastic<br />

polyps’ biopsies to resected polyps, no difference was found in the<br />

evolutionary profile of the 2 groups. A size less than 10 mm (p =0.013)<br />

was associated with fundic gland polyps. Sixty polyps (47.2%) were<br />

treated by cold forceps, 19 (15%) treated by a mucosal resection and<br />

15 (11.8%) with diathermic snare. Five procedural bleeding incidents<br />

were observed (3.9%). Only the use of anticoagulant treatment was<br />

associated with a high bleeding risk (p=0.005). The comparative<br />

histological study between specimens of biopsied GPs and endoscopic<br />

polypectomy led to an overall agreement of 95.3%.<br />

Conclusion<br />

In our study, the GPs frequency was 0.36%. Hyperplastic polyps and<br />

The majority of polyps are benign (> 85% of cases). The risk of<br />

malignancy or malignant transformation of gastric polyps depends on<br />

their histological nature. GPs have been associated with multiple factors,<br />

such as H. pylori infection for hyperplastic polyps and adenomas,<br />

proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) use for fundic gland polyps [4, 5].<br />

The aim of this study was to precise the frequency of different types of<br />

gastric polyps in our population and to analyze their possible association<br />

with other factors to evaluate the results of curative endoscopic<br />

resection of gastric polyps and to study the evolutionary status of<br />

unresected gastric polyps.<br />

Methods<br />

Study design<br />

A retrospective study in which all consecutive patients with GPs were<br />

enrolled was performed at a tertiary-level hospital (Habib Thameur<br />

Hospital of Tunis) from 2008 to 2017. A total of 18,496 consecutive<br />

EGD over a 10-year period were retrospectively reviewed. Eightysix<br />

patients diagnosed with gastric polyps were analysed. Follow-up<br />

gastroscopies performed on the same patient were not excluded. This<br />

study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki, following<br />

the guidelines for good clinical practice. Habib Thameur Hospital ethics<br />

committee approved the study protocol.<br />

6<br />

*Correspondence: yacoubhaythem@hotmail.com<br />

1<br />

<strong>Gastroenterology</strong> and Hepatology Department, Habib Thameur Hospital, Tunis, Tunisia<br />

©The Author(s) <strong>2022</strong>

FEATURE<br />

All cases of gastric polyps were identified from endoscopy reports.<br />

All data regarding patients were obtained from the electronic medical<br />

record. Demographic data (sex, age), relevant pathological history<br />

(colorectal cancer or hereditary polyposis syndrome, colon polyp,<br />

cirrhosis), routine hemograms, as well as data related to the EGD<br />

indication of gastroscopy, number and size of GPs, location, histological<br />

type, and the presence of chronic gastritis or H. pylori infection using<br />

the Hematoxylin eosin staining) were collected. The polyp size was<br />

estimated by comparing it with the opening size of the used biopsy<br />

forceps. In patients with multiple polyps, we collected the endoscopic<br />

characteristics of the four largest polyps. GP recurrence following<br />

resection were also collected (number, location, size, histological type<br />

and, recurrence interval after polypectomy) Patients whose hemoglobin<br />

levels were less than 13 g/dl in males and 12 g/dl in females were<br />

considered with anemia.<br />

was based on endoscopic findings; the most common localization<br />

for gastric polyps was the fundus, followed by the antrum and the<br />

corpus (Table 2).<br />

Histopathologic diagnosis of polyps was obtained for 127 polyps.<br />

The histological study showed hyperplastic polyps in 71 of the polyps<br />

(55.9%), followed by fundic gland polyps (n=23, 18.1%) (Table 3). The<br />

“other” category included pancreatic heterotopias, lipoma and polypoid<br />

foveolar hyperplasia.<br />

H. pylori infection identification was carried out with the hematoxylin<br />

eosin staining in 64 patients (patients with gastric mucosa<br />

abnormalities). H. pylori infection was detected in 45 patients<br />

(62.3%). H. pylori was positive in 30 of the 49 (61.2%) of patients with<br />

hyperplastic polyps.<br />

Ethics approval and consent to participate<br />

This study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki,<br />

following the guidelines for good clinical practice. “Habib Thameur<br />

Hospital ethics committee” approved the study protocol. All methods<br />

were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.<br />

Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from<br />

participants.<br />

Statistical analysis<br />

The data were analyzed on the Statistical Package for the Social<br />

Sciences (SPSS) version 23, IBM SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL, USA). Results<br />

for the continuous variables that followed a normal distribution were<br />

expressed as mean±standard deviation and range while variables that<br />

did not follow a normal distribution were presented in median and the<br />

interquartile range.<br />

For comparisons, Student’s t-test was used for quantitative variables.<br />

A univariate analysis was conducted to identify the possible associated<br />

factors with the different histological types of GPs. A multivariate analysis<br />

was carried out with variables that achieved statistical significance. The<br />

level of statistical significance was established with a p value ≤ 0.05.<br />

The factors independently associated with hyperplastic polyps were<br />

the presence of anemia, being a single polyp, and sized≥5 mm. The<br />

associated variable for fundic gland polyps, was only size 70 years. Age distribution of the patients with<br />

GPs was summarized in Fig. 1.<br />

More than the three-quarters of the patients had single polyps.<br />

The average polyp diameter was 6 mm (range: 2–30 mm). The<br />

diameters of the polyps were < 5 mm in 69 of cases (48.9%), 5–9<br />

mm in 53 (37.6%) patients, 10–19 mm in 15 (10.7%) patients,<br />

and ≥ 20 mm in 4 (2.8%) patients (Table 2). The location of GPs<br />

Age (median years),(range, years) 58.1 ± 15.4, (18–84)<br />

Gender<br />

Male 22 (25.6)<br />

Female 64 (74.4)<br />

Personal history<br />

GERD 26 (30.2)<br />

Anemia 36 (44.2)<br />

Colon polyps 2 (2.3)<br />

Cirrhosis 11 (12.8)<br />

Gastrectomy 3 (3.5)<br />

Hereditary polyposis syndrome 0 (0)<br />

Indication<br />

Epigastric pain 30 (34.9)<br />

Dyspepsia 16 (18.6)<br />

Anemia 21 (24.4)<br />

UGIB 2 (2.3)<br />

Monitoring of PHT 13 (15.1)<br />

Other 4 (4.7)<br />

GP gastric polyps, GERD gastro-esophageal reflux disease, PHT portal<br />

hypertension, UGIB upper gastrointestinal bleeding<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SPRING <strong>2022</strong><br />

7

FEATURE<br />

Anticoagulant or anti-aggregating medication was significantly correlated<br />

with the onset of bleeding (p=0.002).<br />

Twenty-one polyps were biopsied and then resected. A comparison of<br />

the histological results between biopsy specimen and polypectomy was<br />

made.<br />

Adenomas analysis showed a 100% agreement between primary and<br />

final results. The agreement rate was 93% for hyperplastic polyps<br />

(13 polyps out of 14). The comparative histological study between<br />

specimens of biopsied GPs and endoscopic polypectomy led to an<br />

overall agreement of 95.3% (Table 7).<br />

Discussion<br />

One hundred and twenty-seven specimens, corresponding to eightysix<br />

patients, of the total of 18,496 upper gastrointestinal endoscopic<br />

procedures, taken from gastric polypoid lesions (0.46%) were reported.<br />

In the literature, a great variability was observed in the prevalence of<br />

GPs, ranging from 0.5 to 6.35% [2, 6, 7]. In our study, the prevalence<br />

of GPs is lesser than reported in literature. This can be explained by<br />

the fact that follow-up EGD performed on the same patient was not<br />

excluded.<br />

This is the first study that evaluates the GPs frequency in Tunisia. In our<br />

study, we found that the most common symptoms in patients with GPs<br />

were epgastric pain and anemia. We also found that GPs were localized<br />

mostly in the fundus, and mostly Is according to Paris classification and<br />

the hyperplastic type was the most common.<br />

Table 2 Morphological and histological characteristics of the<br />

141 polyps<br />

Parameter n (%)<br />

Table 2 Morphological and histological characteristics of the<br />

Patient with GPs 86 (100)<br />

141 polyps<br />

Single 65 (75.6)<br />

Parameter Multiple n (%) 21 (24.4)<br />

Location<br />

Patient with GPs 86 (100)<br />

Fundus 51 (59.3)<br />

Single 65 (75.6)<br />

Body 5 (5.8)<br />

Multiple 21 (24.4)<br />

Antrum 28 (32.6)<br />

Location<br />

Multiple location 2 (2.3)<br />

Fundus 51 (59.3)<br />

Size in mm<br />

Body 5 (5.8)<br />

1–4 mm 69 (48.9)<br />

Antrum 28 (32.6)<br />

5–9 mm 53 (33.6)<br />

Multiple location 2 (2.3)<br />

10–14 mm 8 (5.7)<br />

Size in mm<br />

15–19 mm 7 (5)<br />

1–4 mm 69 (48.9)<br />

> 20 mm 4 (2.8)<br />

5–9 mm 53 (33.6)<br />

Paris classification<br />

10–14 mm 8 (5.7)<br />

Ip 17 (12)<br />

15–19 mm 7 (5)<br />

Is 112 (80)<br />

> 20 mm 4 (2.8)<br />

IIa 11 (8)<br />

Paris classification<br />

IIb, IIc 0 (0)<br />

Ip 17 (12)<br />

Is GP gastric polyps<br />

112 (80)<br />

IIa 11 (8)<br />

IIb, IIc 0 (0)<br />

Hyperplastic polyps and fundic gland polyps together make up to 90%<br />

GP gastric polyps<br />

[6,7,8] followed by adenomas and other histological type, which are<br />

much less common. These rates are similar to those observed in our<br />

population with a predominance of hypeplastic type.<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SPRING <strong>2022</strong><br />

Fig. 1 The age distribution of patients with gastric polyps<br />

Fig. 1 The age distribution of patients with gastric polyps<br />

8

FEATURE<br />

Table Table 3 3 Histological analysis analysis of the of the 127 127 GP GP<br />

Table Table 5 5 Univariate analysis analysis of of associated factors factors with with fundic fundic<br />

Table 3 Histological analysis of the 127 GP<br />

gland Tablepolyps 5 Univariate analysis of associated factors with fundic<br />

Histological Table 3 type Histological type analysis of the 127 GP<br />

gland<br />

n (%) n (%) Tablepolyps 5 Univariate (n=127) analysis of associated factors with fundic<br />

gland polyps (n=127)<br />

Histological type n (%)<br />

Parameter gland polyps (n=127)<br />

Histological type n (%)<br />

Fundic Fundic gland gland polyps polyps Non-fundic p value p value<br />

Hyperplastic 71 (55.9) 71 (55.9)<br />

Parameter Fundic gland polyps gland Non-fundic gland polyps polyps<br />

Parameter Fundic gland polyps Non-fundic p value p value<br />

Fundic Hyperplastic Fundic Hyperplastic gland gland polyps polyps 23 71 (18.1) (55.9) 23 71 (18.1) (55.9)<br />

n (%) n (%) gland n (%) gland n (%) polyps polyps<br />

Adenoma Fundic Adenoma Fundic gland gland polyps polyps 237 (5.5) (18.1) 237 (5.5) (18.1)<br />

n (%) n (%) n (%) n (%)<br />

Age Age (years) (years) 53.3 53.3 ± 21.3 ± 21.3 58.8±14.1 0.303 0.303<br />

Adenoma Neuroendocrine Adenoma neoplasia neoplasia 47 (3.1) (5.5) 47 (3.1) (5.5)<br />

Age Gender (years) 53.3 ± 21.3 58.8±14.1 0.303 0.289<br />

Xanthelasmaneoplasia 14 (0.8) (3.1) 1 (0.8) Age Gender (years) 53.3 ± 21.3 58.8±14.1 0.289 0.303<br />

Neuroendocrine neoplasia 4 (3.1)<br />

Male Gender Male 1 (11.1) 19 (27.5) 0.289<br />

Xanthelasma Inflammatory fibroid fibroid polyp polyp 91 (7.2) (0.8) 9 (7.2) Gender 1 (11.1) 19 (27.5) 0.289<br />

Xanthelasma 1 (0.8)<br />

Male Female 18 (11.1) (88.9) 19 50 (27.5) (72.5)<br />

No Inflammatory true No true polyp polyp fibroid polyp 79 (5.5) (7.2) 7 (5.5) Male Female 18 (11.1) (88.9) 19 50 (27.5) (72.5)<br />

Inflammatory fibroid polyp 9 (7.2)<br />

Female 8 (88.9) 50 (72.5) 0.170<br />

Other No true Other polyp 57 (3.9) (5.5) 5 (3.9) Female Single/multiple 8 (88.9) 50 (72.5) 0.170<br />

No true polyp 7 (5.5)<br />

Single/multiple 5 (55.6) 53 (76.8)<br />

GP Other gastric polyps<br />

5 (3.9)<br />

Single/multiple 5 (55.6) 53 (76.8) 0.170 0.170<br />

GP Other gastric polyps<br />

5 (3.9)<br />

Single Multiple Single Multiple 54 (55.6) (44.4) 54 (55.6) (44.4) 53 16 (76.8) (23.2) 53 16 (76.8) (23.2)<br />

GP gastric GP gastric polyps polyps<br />

GERDMultiple 4 (44.4) 4 (44.4) 16 (23.2) 16 (23.2) 0.7 0.7<br />

Table Table 4 4 Univariate analysis analysis of of associated factors factors with with<br />

GERDYes GERD 5 (55.6) 5 (55.6) 20 (29) 20 (29) 0.7 0.7<br />

Table hyperplastic Table 4 Univariate 4 polyps Univariate polyps (n analysis = (n 127) analysis = 127) of of associated associated factors factors with with Yes No Yes No 54 (55.6) (44.4) 54 (55.6) (44.4) 20 49 (29) (71) 20 49 (29) (71)<br />

hyperplastic polyps (n = 127)<br />

Parameter hyperplastic polyps Hyperplastic (n = 127) polyps polyps Non-<br />

Nonhyperplastic<br />

p value p value No Anemia No Anemia 4 (44.4) 4 (44.4) 49 (71) 49 (71) 0.115 0.115<br />

p value Yes Anemia 8 (88.9) 43 (62.3) 0.115<br />

Parameter Hyperplastic polyps Nonhyperplastic<br />

polyps<br />

Parameter Hyperplastic polyps Nonhyperplastic<br />

Yes No Yes No 81 (88.9) (11.1) 81 (88.9) (11.1) 43 26 (62.3) (37.7) 43 26 (62.3) (37.7)<br />

p value<br />

Yes Anemia 8 (88.9) 43 (62.3) 0.115<br />

polyps<br />

n (%) n (%) n polyps (%) polyps n (%)<br />

No Location No Location 1 (11.1) 1 (11.1) 26 (37.7) 26 (37.7)<br />

n (%) n (%) n (%) n (%)<br />

Age Age (years) (years) 57.7 57.7 ± 13.4 ± 13.4 58.8 58.8 ± 17.4 ± 17.4 0.7 0.7 Fundus Location Fundus Location 23 (100) 23 (100) 56 (53.9) 56 (53.9)<br />

Age Gender Age Gender (years) (years) 57.7 57.7 ± 13.4 ± 13.4 58.8 58.8 ± 17.4 ± 17.4 0.7<br />

0.7<br />

Fundus Non Fundus Non fundus fundus 23 0 (0) (100) 23 0 (0) (100) 56 48 (53.9) (46.1) 56 48 (53.9) (46.1)<br />

Male Gender Male Gender 12 (24.5) 12 (24.5) 8 (27.6) 8 (27.6) 0.7 0.7<br />

Non Size Non Size in fundus mm in fundus mm 0 (0) 0 (0) 48 (46.1) 48 (46.1) 0.013 0.013<br />

MaleFemale 37 12 (75.5) (24.5) 37 12 (75.5) (24.5) 21 8 (27.6) (72.4) 21 8 (27.6) (72.4)<br />

< Size 5 mm < Size in 5 mm in mm 14 (60.9) 14 (60.9) 55 (53) 55 (53) 0.013 0.013<br />

Female Single/multiple Female 37 (75.5) 37 (75.5) 21 (72.4) 21 (72.4) 0.05 0.05 < ≥5 mm < ≥5 mm 14 9 (39.1) (60.9) 14 9 (39.1) (60.9) 55 49 (53) (47) 55 49 (53) (47)<br />

Single/multiple Single/multiple 40 (81.6) 40 (81.6) 11 (38) 11 (38) 0.05 0.05<br />

≥Paris 5 mm ≥Paris 5 mm classification 9 (39.1) 9 (39.1) 49 (47) 49 (47)<br />

Multiple Single Multiple Single 940 (18.4) (81.6) 940 (18.4) (81.6) 18 11 (62) (38) 18 11 (62) (38)<br />

Ip Paris Ip Paris classification classification 3 (13) 3 (13) 12 (11.5) 12 (11.5) 0.524 0.524<br />

GERD Multiple GERD Multiple 9 (18.4) 9 (18.4) 18 (62) 18 (62) 0.7 0.7 Ip Is Ip Is 316 (13) (69.5) 316 (13) (69.5) 12 85 (11.5) (81.7) 12 85 (11.5) (81.7) 0.524 0.273 0.524 0.273<br />

GERDYes GERD 15 (30.6) 15 (30.6) 10 (34.5) 10 (34.5) 0.7 0.7<br />

Is IIa Is IIa 16 4 (17.5) (69.5) 16 4 (17.5) (69.5) 85 7 (6.8) (81.7) 85 7 (6.8) (81.7) 0.273 0.105 0.273 0.105<br />

No Yes No Yes 34 15 (69.4) (30.6) 34 15 (69.4) (30.6) 19 10 (65.5) (34.5) 19 10 (65.5) (34.5)<br />

IIa IIb, IIc IIa IIb, IIc 40 (17.5) (0) 40 (17.5) (0) 70 (6.8) (0) 70 (6.8) (0) 0.105 – 0.105 –<br />

Anemia No Anemia No 34 (69.4) 34 (69.4) 19 (65.5) 19 (65.5) < 10 < –3 10 –3 GP: IIb, IIc gastric GP: IIb, IIc gastric polyps, polyps, GERD: GERD: 0 (0) 0 gastro-esophageal (0) reflux reflux disease 0 (0) disease 0 (0) – –<br />

Yes Anemia Yes Anemia 28 (57.2) 28 (57.2) 3 (10.3) 3 (10.3) < 10 < –3<br />

10 –3 Significant GP: gastric Significant GP: gastric polyps, p value polyps, p value GERD: < 0.05 GERD: < 0.05 are in gastro-esophageal are bold in bold reflux reflux disease disease<br />

No Yes Yes No 21 28 (42.8) (57.2) 21 28 (42.8) (57.2) 26 3 (10.3) (89.7) 26 3 (10.3) (89.7)<br />

Significant Significant p value p value < 0.05 < 0.05 are in are bold in bold<br />

Location No Location No 21 (42.8) 21 (42.8) 26 (89.7) 26 (89.7) 0.009 0.009<br />

Table Table 6 Risk 6 Risk value value for the for the significant variables variables in the in the multivariate<br />

Antrum Location Antrum Location 34 (47.9) 34 (47.9) 43 (76.8) 43 (76.8) 0.009 0.009<br />

analysis Table analysis Table 6 Risk 6 Risk value value for the for the significant significant variables variables in the in the multivariate multivariate<br />

Non Antrum Non Antrum antrum antrum 37 34 (52.1) (47.9) 37 34 (52.1) (47.9) 13 43 (23.2) (76.8) 13 43 (23.2) (76.8)<br />

analysis<br />

Size Non Size in antrum mm in mm 37 (52.1) 13 (23.2) 0.002 0.002 Variable Variable analysis<br />

Non antrum 37 (52.1) 13 (23.2)<br />

Odds Odds ratio ratio 95% 95% CI CI p value p value<br />

< Size 5 mm < Size in 5 mm in mm 30 (42.3) 30 (42.3) 39 (69.6) 39 (69.6) 0.002 0.002<br />

Variable Variable Hyperplastic polyps polyps<br />

Odds Odds ratio ratio 95% 95% CI CI p value p value<br />

≥< 5 mm ≥< 5 mm 41 30 (47.7) (42.3) 41 30 (47.7) (42.3) 17 39 (30.4) (69.6) 17 39 (30.4) (69.6)<br />

Anemia Hyperplastic Anemia Hyperplastic polyps polyps 4.28 4.28 (1.39–13.17) 0.022 0.022<br />

Paris ≥ 5 mm Paris ≥ 5 mm classification 41 (47.7) 41 (47.7) 17 (30.4) 17 (30.4)<br />

Single Anemia Anemia Single 2.85 4.282.85 (1.39–13.17) (0.95–8.59) (1.39–13.17) 0.025 0.022 0.025 0.022<br />

Ip Paris Ip Paris classification classification 10 (14) 10 (14) 5 (8.9) 5 (8.9) 0.371 0.371<br />

Size≥5 Single Size≥5 Single mm mm 2.851.85 (0.95–8.59) (1.29–2.67) (0.95–8.59) 0.048 0.025 0.048 0.025<br />

Is Ip Is Ip 58 10 (81.7) (14) 58 10 (81.7) (14) 43 5 (8.9) (76.8) 43 5 (8.9) (76.8) 0.496 0.371 0.496 0.371 Fundic Size≥5 Fundic Size≥5 mmgland polyps polyps 1.85 1.85 (1.29–2.67) (1.29–2.67) 0.048 0.048<br />

IIa Is IIa Is 358 (4.3) (81.7) 358 (4.3) (81.7) 843 (14.3) (76.8) 843 (14.3) (76.8) 0.055 0.496 0.055 0.496 Size Fundic Size Fundic < 5gland mm < 5gland mm polyps polyps 2.31 2.31 (1.37–4.11) < 0.001 < 0.001<br />

IIb, IIa IIc IIb, IIa IIc 03 (0) (4.3) 03 (0) (4.3) 08 (0) (14.3) 08 (0) (14.3) – 0.055 – 0.055 Size GP gastric GP Size < 5gastric mm < polyps, 5 mm polyps, GERD GERD gastro-esophageal 2.31 2.31 (1.37–4.11) reflux (1.37–4.11) reflux disease disease < 0.001 < 0.001<br />

GP IIb, gastric IIc GP IIb, gastric IIcpolyps, polyps, GERD GERD 0 (0) 0 gastro-esophageal (0) reflux reflux disease 0 disease (0) 0 (0) – –<br />

GP gastric GP gastric polyps, polyps, GERD GERD gastro-esophageal reflux reflux disease disease<br />

Significant GP gastric Significant GP gastric polyps, p value polyps, p value GERD < 0.05 GERD < 0.05 are gastro-esophageal in are bold in bold reflux reflux disease disease<br />

Significant Significant p value p value < 0.05 < 0.05 are in are bold in bold<br />

are the most common [9,10,11,12,13]. It has been suggested that<br />

the prevalence of hyperplastic polyps could be related to the high<br />

Argüello et al. reported the frequency of GP as 42.8% for<br />

hyperplastic polyps, and 37.7% for fundic gland polyps. The<br />

mean age of the patients was 65.6 years and 38% were males<br />

[9]. Carmack et al. found the incidence of GP as 6.3% in 121.564<br />

EGD. Fundic gland polyps were the most frequent polyp type,<br />

which accounted for 77% of all polyps of all polyps [6]. Fundic<br />

gland polyps were the second most common type (18.1%) of GPs<br />

lesions in our study. In the majority of series, hyperplastic polyps<br />

prevalence of H. pylori infection in our population (62.3%). Freeman<br />

et al. reported tendency of fundic gland polyps to arise in H. pylori<br />

-free stomachs [14] (OR 0.007, 95% CI 0.003–0.015). The same<br />

findings were also reported in Carmack et al. study (OR 0.007,<br />

95% CI 0.003–0.016) [6]. Fundic gland polyps tend also to arise<br />

in patients who receive long-course PPI treatment [14, 15]. The<br />

widespread of PPIs use and the low H. Pylori infection rate may be<br />

the most important reasons behind the large frequency of fundic<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SPRING <strong>2022</strong><br />

9

FEATURE<br />

gland polyps reported in American studies [6, 14]. Although in three<br />

Spanish series, hyperplastic polyps were the most common which<br />

is comparable to our study [8, 9, 16].<br />

Hyperplastic polyps are associated with chronic gastritis such<br />

as H. pylori gastritis, and particularly autoimmune gastritis.<br />

Patients with hyperplastic polyp have an increased risk of gastric<br />

adenocarcinoma [1, 17, 18].<br />

In our study, adenomas were detected in seven patients (5.5%).<br />

The majority of cases we reported were low-grade intestinal-type.<br />

These polyps constitute less than 10% and have a malignant<br />

potential. They are more common in communities where gastric<br />

cancer is frequent [19]. Malignant potential of adenomas is variable<br />

(6.8% − 55.3%) [20]. Risk factors for malignancy transformation are:<br />

high-grade dysplasia, and size of the lesion [19].<br />

It has been reported that between 16 and 37.5% of cases, and<br />

despite the endoscopic appearance of a polyp, the final histological<br />

study shows normal mucosa [6, 16]. In our study the percentage of<br />

biopsies with normal mucosa was 5.5%.<br />

Although the majority of GP do not cause symptoms, they can be<br />

the cause of bleeding and gastric obstruction. Frequently, GP are<br />

detected during EGD performed to study gastrointestinal symptoms<br />

not attributable to polyps or asymptomatic patients examined for<br />

other reasons [6, 21].<br />

In our study, an association between hyperplastic polyps and<br />

anemia, single polyps and size > 5 mm. It has been described in<br />

the literature between anaemia and hyperplastic polyps, while the<br />

gastrointestinal reflux was associated with fundic gland polyps [22].<br />

A total of 94 polyps were resected with snare. Five patients had<br />

hemorrhage requiring endoscopic treatment and bleeding was<br />

60<br />

53<br />

Table 7 Agreement between polypectomy and biopsy<br />

specimen in different histological types<br />

Histological type<br />

Biopsy<br />

Polypectomy<br />

Table 7 Agreement between<br />

specimen (n)<br />

polypectomy<br />

(n)<br />

and biopsy<br />

specimen Adenomas in different histological types<br />

Histological With low grade typedysplasia Biopsy 4 Polypectomy<br />

4<br />

With high grade dysplasia specimen 1 (n) (n) 1<br />

Fundic gland polyps<br />

Adenomas<br />

1 1<br />

Hyperplastic polyps<br />

With low grade dysplasia<br />

13<br />

4<br />

14<br />

4<br />

Type I neuroendoscrine tumor<br />

With high grade dysplasia<br />

1<br />

1<br />

1<br />

1<br />

Inflammatory mucosa<br />

Fundic gland polyps<br />

1<br />

1<br />

0<br />

1<br />

Hyperplastic polyps 13 14<br />

Type I neuroendoscrine tumor 1 1<br />

controlled Inflammatory by mucosa endoscopic procedures. 1 Perforation did 0not occur in<br />

any of our patients. In the literature, bleeding as a complication of<br />

gastric polypectomy was reported in 3.5% [23].<br />

Relationship between long-term PPIs use and fundic gland polyps’<br />

occurring has not yet been fully established. Jalving et al. [4] found<br />

in their study a significant association only in the subgroup of<br />

patients treated with PPI for over 1 year. Our data do not support a<br />

relationship between PPI and fundic gland polyps.<br />

In patients with GP, evaluating H. pylori infection state by obtaining<br />

biopsies of the surrounding gastric mucosa is recommended and<br />

treatment is required if present [24, 25].<br />

Hyperplastic polyps should be biopsied according to the British<br />

society of gastroenterology and an examination of the whole<br />

stomach should be made. H pylori infection should be detected and<br />

eradicated when present [24]. GP of the non-adenomatous type<br />

are at a low risk of malignant transformation, therefore endoscopic<br />

resection is not necessary.<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SPRING <strong>2022</strong><br />

50<br />

60<br />

53<br />

40<br />

50<br />

30<br />

40<br />

14 14<br />

20<br />

7<br />

30<br />

10<br />

14<br />

1<br />

14<br />

20<br />

7<br />

0<br />

10<br />

Cold snare Hot snare<br />

1<br />

EMR<br />

Monoblock Piece-meal<br />

0<br />

Fig. 2 The distribution of polypectomy. EMR endoscopic mucosal resection<br />

Cold snare Hot snare EMR<br />

Monoblock Piece-meal<br />

Fig. 2 The distribution of polypectomy. EMR endoscopic mucosal resection<br />

5<br />

5<br />

10

FEATURE<br />

Guidelines on management of hyperplastic polyps, recommend<br />

resection of polyps greater than 5 mm [26, 27].<br />

Complete removal of the adenoma should be performed when safe to<br />

do according to the British recommendations [24].<br />

Polypectomy is not required for sporadic fundic gland polyps. Biopsy of<br />

probable fundic gland polyps is recommended to exclude dysplasia. In<br />

patients with multiple fundic gland polyps who are under 40 years-old,<br />

or where biopsies specimens show dysplasia, colonoscopy should be<br />

performed to exclude familial adenomatous polyposis [24].<br />

Szaloki et al. reported that there were important disagreements in 12<br />

cases of examined forceps biopsy specimens. In 14 neoplastic, and<br />

1 hyperplastic polyps, the degree of dysplasia seen on histological<br />

examination of the forceps biopsy specimens differed from that<br />

observed for the resected specimens. Complete agreement between<br />

the histological results on ectomized polyp, and the forceps biopsy<br />

was observed in only 55.3% of the cases [28]. In our study, Adenomas<br />

analysis showed a 100% agreement between primary and final results.<br />

The agreement rate was 93% for hyperplastic polyps (13 polyps out of<br />

14). The overall agreement was of 95.3%.<br />

Ethics approval and consent to participate<br />

This study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki,<br />

following the guidelines for good clinical practice. “Habib Thameur<br />

Hospital ethics committee” approved the study protocol. All methods<br />

were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.<br />

Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from<br />

participants.<br />

Consent for publication<br />

Not applicable.<br />

Competing interests<br />

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.<br />

Author details<br />

1<br />

<strong>Gastroenterology</strong> and Hepatology Department, Habib Thameur<br />

Hospital, Tunis, Tunisia. 2 Faculty of Medicine of Tunis, El Manar<br />

University, Tunis, Tunisia.<br />

Received: 8 July 2021 Accepted: 7 February <strong>2022</strong><br />

Published online: 19 February <strong>2022</strong><br />

Our study included the greatest number of EGD with patients diagnosed<br />

with GP in our country.<br />

Conclusion<br />

Gastric polyps’ frequency in our study was low (0.46%). Hyperplastic<br />

polyps are the most common gastric polyps in our country. In case of<br />

single polyps, biopsies are recommended to rule out a diagnosis of<br />

adenoma or hyperplastic polyps with dysplasia. Good knowledge of<br />

practical guidelines is important for the management of GP.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Not applicable.<br />

Authors’ contributions<br />

H.Y.: concept, design, definition of intellectual content, literature<br />

search, manuscript preparation, manuscript editing, manuscript review.<br />

N.B.: concept, design, definition of intellectual content, manuscript<br />

preparation, manuscript review. M.S.: definition of intellectual content,<br />

manuscript preparation. N.B.: design. A.O.: design, manuscript<br />

review. D.T.: manuscript review. D.G.: definition of intellectual content,<br />

manuscript review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.<br />

Funding<br />

Not applicable.<br />

Availability of data and materials<br />

The data that support the findings of this study are available on<br />

request from the corresponding author, [HY]. The data are not publicly<br />

available due to [restrictions e.g. their containing information that could<br />

compromise the privacy of research participants].<br />

Declarations<br />

References<br />

1. Lesur G. Gastric polyps: how to recognize? Which to resect?<br />

Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2009;33(4):233–9.<br />

2. Voutilainen M, Mantynen T, Kunnamo I, Juhola M, Mecklin JP,<br />

Farkkila M. Impact of clinical symptoms and referral volume on<br />

endoscopy for detecting peptic ulcer and gastric neoplasms. Scand<br />

J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(1):109–13.<br />

3. Barbosa SHB, Lazaro GCF, Franco LM, Valenca JTJ, Nobre<br />

SMA, Souza M. Agreement between different pathologists in<br />

histopathologic diagnosis of 128 gastric polyps. Arq Gastroenterol.<br />

2017;54(3):263–6.<br />

4. Jalving M, Koornstra JJ, Wesseling J, Boezen HM, Jong DE,<br />

Kleibeuker SJH. Increased risk of fundic gland polyps during<br />

long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther.<br />

2006;24:1341–8.<br />

5. Elhanafi S, Saadi M, Lou W, Mallawaarachchi I, Zuckerman AM,<br />

Othman MO. Gastric polyps: a association with Heli-cobacter<br />

pylori status and the pathology of the surrounding mucosa, a cross<br />

sectional study. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:995–1002.<br />

6. Carmack SW, Genta RM, Schuler CM, Saboorian MH. The current<br />

spectrum of gastric polyps: a 1-year national study of over 120,000<br />

patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(6):1524–32.<br />

7. Morais DJ, Yamanaka A, Zeitune JM, Andreollo NA. Gastric polyps:<br />

a retrospective analysis of 26,000 digestive endoscopies. Arq<br />

Gastroenterol. 2007;44(1):14–7.<br />

8. Garcia Alonso FJ, Marti Mateos RM, Gonzalez Martin JA, Foruny<br />

JR, Vazquez Sequeiros E, Boixeda de Miquel D. Gastric polyps:<br />

analysis of endoscopic and histological features in our center. Rev<br />

Esp Enferm Dig. 2011;103(8):416–20.<br />

9. Argüello Viúdez L, Córdova H, Uchima H, Sánchez Montes C, Ginès<br />

À, Araujo I, et al. Gastric polyps: retrospective analysis of 41,253<br />

upper endoscopies. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40(8):507–14.<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SPRING <strong>2022</strong><br />

11

FEATURE<br />

10. Bassene ML, Diallo S, Thioubou MA, Diallo A, Gueye MN, Diouf ML.<br />

Gastric polyps in a digestive endoscopy center in Dakar. Open J<br />

Gastroenterol. 2017;7(10):279–86.<br />

11. Olmez S, Sayar S, Saritas B, Savas AY, Avcioglu U, Tenlik I, et<br />

al. Evaluation of patients with gastric polyps. North Clin Istanb.<br />

2018;5(1):41–6.<br />

12. Ljubicic N, Kujundzic M, Roic G, Banic M, Cupic H, Doko M, et al.<br />

Benign epithelial gastric polyps-frequency, location, and age and sex<br />

distribution. Coll Antropol. 2002;26(1):55–60.<br />

13. Sivelli R, Del Rio P, Bonati L, Sianesi M. Gastric polyps: a clinical<br />

contribution. Chir Ital. 2002;54(1):37–40.<br />

14. Freeman HJ. Proton pump inhibitors and an emerging epidemic<br />

of gastric fundic gland polyposis. World J Gastroenterol.<br />

2008;14:1318–20.<br />

15. Raghunath AS, O’Morain C, McLoughlin RC. Review article: the<br />

long-term use of proton-pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther.<br />

2005;22(11):55–63.<br />

16. Macenlle García R, Bassante Flores LA, Fernández Seara J. Pólipos<br />

gástricos epiteliales. Estudio retrospectivo 1995–2000. Rev Clin<br />

Esp. 2003;203(8):368–72.<br />

17. Abraham SC, Singh VK, Yardley JH, Wu TT. Hyperplastic polyps of<br />

the stomach: associations with histologic patterns of gastritis and<br />

gastric atrophy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(4):500–7.<br />

18. Scoazec JY. Les polypes gastriques: pathologie et génétique. Ann<br />

Pathol. 2006;26(3):173–99.<br />

19. Hattori T. Morphological range of hyperplastic polyps and<br />

carcinomas arising in hyperplastic polyps of the stomach. J Clin<br />

Pathol. 1985;38(6):622–30.<br />

20. Stolte M. Clinical consequences of the endoscopic diagnosis of<br />

gastric polyps. Endoscopy. 1995;27:32–7.<br />

21. Gencosmanoglu R, Sen Oran E, Kurtkaya Yapicier O, Avsar E, Sav<br />

A, Tozun N. Gastric polypoid lesions: analysis of 150 endoscopic<br />

polypectomy specimens from 91 patients. World J Gastroenterol.<br />

2003;9(10):2236–9.<br />

22. Sonnenberg A, Genta RM. Prevalence of benign gastric polyps in a<br />

large pathology database. Digest Liver Dis. 2015;47:164–9.<br />

23. Russo A, Sanfi lippo G, Magnano A, La Malfa M, Belluardo N.<br />

Complications de la polypectomie endoscopique gastrique et<br />

duodénale expérience italienne. Acta Endosc. 1986;16(5):251.<br />

24. Goddard AF, Badreldin R, Pritchsard DM, Walker MM, War-ren B. on<br />

behalf of the British Society of <strong>Gastroenterology</strong>. The management<br />

of gastric polyps. Gut. 2010;59:1270–6.<br />

25. Sharaf RN, Shergill AK, Odze RD, Krinsky ML, Fukami N, Jain R, et<br />

al. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee. Endoscopic mucosal<br />

tissue sampling. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:216–24.<br />

26. Evans JA, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi KV, Decker GA, Early DS,<br />

Fisher DA, et al. ASGE guideline: the role of endoscopy in the<br />

management of premalignant and malignant conditions of the<br />

stomach. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:1–8.<br />

27. Han AR, Sung CO, Kim KM, Park C, Min B, Lee JH, et al.<br />

Theclinicopathological features of gastric hyperplastic polyps with<br />

neoplastic transformations: a suggestion of indication for endoscopic<br />

polypectomy. Gut Liver. 2009;3:271–5.<br />

28. Szaloki T, Toth V, Tiszlavicz L, Czako L. Flat gastric polyps: results<br />

of forceps biopsy, endoscopic mucosal resection, and long-term<br />

follow-up. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41(9):1105–9.<br />

Publisher’s Note<br />

<strong>Spring</strong>er Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in<br />

published maps and institutional affi liations.<br />

WHY NOT WRITE FOR US?<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SPRING <strong>2022</strong><br />

<strong>Gastroenterology</strong> <strong>Today</strong> welcomes the submission of<br />

clinical papers and case reports or news that<br />

you feel will be of interest to your colleagues.<br />

Material submitted will be seen by those working within all<br />

UK gastroenterology departments and endoscopy units.<br />

All submissions should be forwarded to info@mediapublishingcompany.com<br />

If you have any queries please contact the publisher Terry Gardner via:<br />

info@mediapublishingcompany.com<br />

12

FASTER DIAGNOSIS OF GASTRIC CANCER<br />

FEATURE<br />

Gastric cancer is typically diagnosed at a very late stage,<br />

leading to a poor prognosis for the patient, and the strain<br />

on healthcare services through the COVID-19 pandemic<br />

has only made things worse. However, detection of precancerous<br />

conditions – such as atrophic gastritis (AG) and<br />

gastric intestinal metaplasia (GIM) – before endoscopy could<br />

potentially support diagnostic pathways, allowing doctors<br />

in primary care to identify and prioritise patients for whom<br />

endoscopy would be useful, streamlining NHS resources and<br />

improving patient outcomes.<br />

What are AG and GIM?<br />

AG is a chronic inflammatory condition of the gastric mucosa.<br />

It can be an autoimmune disorder, but most commonly arises<br />

following prolonged inflammation caused by Helicobacter<br />

pylori<br />

infection. This disrupts the mucus barrier that helps<br />

to protect the cells of the stomach lining from digestive<br />

juices, causing them to be slowly destroyed. AG significantly<br />

increases the risk of stomach cancer, with 18 % of cases<br />

progressing to cancer within 10 years. However, studies<br />

suggest that in some cases the progression of AG can be<br />

halted, and even improved, reinforcing the importance of early<br />

diagnosis and monitoring. 1<br />

GIM is common in cases of AG and occurs when the cells<br />

of the stomach lining are replaced with cells similar to the<br />

lining of the intestines. Again, H. pylori is often implicated in<br />

this process, which predisposes individuals to intestinal-type<br />

gastric adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine tumours (NETs).<br />

Patients with GIM are often over 50 years of age, and the risk<br />

is further increased by factors such as smoking or having a<br />

first-degree relative with gastric cancer.<br />

Challenges of diagnosis<br />

The current gold standard for diagnosing AG and GIM is<br />

gastroscopy with targeted biopsies, which relies on referral<br />

of patients from primary care. However, AG and GIM are often<br />

asymptomatic – or present with very general symptoms such as<br />

stomach pain, loss of appetite, nausea or vomiting, anaemia and<br />

stomach ulcers – making them hard to detect. Tests for<br />

H. pylori infection, along with blood tests for levels of<br />

pepsinogens and gastrin-17, may help to identify some patients<br />

for whom a referral would be beneficial. However, current<br />

practice is not to actively look for AG and GIM cases before<br />

endoscopy, and so patients may remain undiagnosed in primary<br />

care for prolonged periods if they do not qualify for referral.<br />

Rapid detection of AG and GIM<br />

GastroPanel from BIOHIT is a simple, non-invasive blood test<br />

that can be used in primary care settings for effective diagnosis<br />

of AG and GIM. It gives detailed information on the structure<br />

and function of the stomach mucosa, by quantifying pepsinogen<br />

I, pepsinogen II and gastrin-17, and can also differentiate the<br />

cause of AG by identifying IgG antibodies to H. pylori. Using<br />

GastroPanel in targeted groups of at-risk patients could help to<br />

direct referrals more effectively. As well as detecting cancers<br />

at an earlier and more curable stage, reducing the number of<br />

gastroscopies in lower risk patients would reduce both the cost<br />

and volume burden on healthcare resources, without adversely<br />

affecting patient care.<br />

For more information about GastroPanel<br />

contact: info@biohithealthcare.co.uk<br />

1 . Kong YJ, Yi HG, Dai JC, Wei MX. Histological changes of gastric mucosa after Helicobacter pylori eradication: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(19): 5903-5911<br />

For the early diagnosis<br />

of gastric cancer risk<br />

Reduce endoscopy waiting lists and<br />

improve the diagnostic pathway for<br />

patients, through an earlier, faster<br />

and more cost-effective approach.<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SPRING <strong>2022</strong><br />

www.biohithealthcare.co.uk<br />

13

FEATURE<br />

ENDOSCOPIC RETROGRADE APPENDICITIS<br />

THERAPY VERSUS LAPAROSCOPIC<br />

APPENDECTOMY VERSUS OPEN APPENDECTOMY<br />

FOR ACUTE APPENDICITIS: A PILOT STUDY<br />

Zhemin Shen 1 , Peilong Sun 1*† , Miao Jiang 2† , Zili Zhen 1 , Jingtian Liu 1 , Mu Ye 1 and Weida Huang 1<br />

Shen et al. BMC <strong>Gastroenterology</strong> (<strong>2022</strong>) 22:63 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-022-02139-7<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SPRING <strong>2022</strong><br />

14<br />

Abstract<br />

Background<br />

An increasing number of studies have shown the merits of endoscopic<br />

retrograde appendicitis therapy (ERAT) in diagnosing and treating acute<br />

uncomplicated appendicitis. However, no related prospective controlled<br />

studies have been reported yet. Our aim is to assess the feasibility and<br />

safety of ERAT in the treatment of acute uncomplicated appendicitis.<br />

Methods<br />

In this open-label, randomized trial, participants were randomly allocated<br />

to the ERAT group, laparoscopic appendectomy (LA) group and open<br />

appendectomy (OA) group. The primary outcome was the clinical success<br />

rate of the treatment. Intention-to-treat analysis was used in the study.<br />

Results<br />

The study comprised of 99 patients, with 33 participants in each<br />

group. The clinical success rate was 87.88% (29/33), 96.97% (32/33)<br />

and 100% (33/33) in the ERAT, LA and OA group, respectively. In the<br />

ERAT group, 4 patients failed ERAT due to difficult cannulation. In LA<br />

group, 1 patient failed because of abdominal adhesion. There were no<br />

significant differences among the three treatment groups regarding the<br />

clinical success rate (P=0.123). The median duration of follow-up was<br />

22 months. There were no significant differences (P =0.693) among the<br />

three groups in terms of adverse events and the final crossover rate of<br />

ERAT to surgery was 21.21% (7/33).<br />

Conclusion<br />

ERAT can serve as an alternative and efficient method to treat acute<br />

uncomplicated appendicitis.<br />

Trial registration The study is registered with the WHO Primary Registry-<br />

Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR1900025812).<br />

Keywords<br />

Acute appendicitis, Endoscopic retrograde appendicitis therapy,<br />

Appendectomy, Randomized controlled trial<br />

Introduction<br />

Acute appendicitis is one of the most common causes of acute<br />

abdominal pain clinically [1]. Appendectomy has long been standard<br />

treatment for acute appendicitis. However, there are a series of potential<br />

*Correspondence: sunpeilong@fudan.edu.cn<br />

†<br />

Peilong Sun and Miao Jiang contributed equally in the trial<br />

1<br />

Department of General Surgery, Jinshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China<br />

©The Author(s) <strong>2022</strong><br />

postoperative complications, such as postoperative bleeding, wound<br />

infection and intestinal obstruction [2, 3], and the overall complication<br />

rate has been reported to be 8.2–31.4% [1]. Moreover, negative<br />

appendectomy is also a nonnegligible problem [4]. As previous studies<br />

suggested that perforation may not be an inevitable consequence of<br />

acute appendicitis, there is a division of opinions on performing surgery<br />

on patients with acute uncomplicated appendicitis [5]. Thus, developing<br />

a safe and efficient nonoperative method has been an agenda for<br />

treating acute uncomplicated appendicitis.<br />

Endoscopic retrograde appendicitis therapy (ERAT) was firstly<br />

reported by Liu et al. as being inspired by endoscopic retrograde<br />

cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) [6]. ERAT is a novel, nonoperative and<br />

minimally invasive method of treating acute uncomplicated appendicitis.<br />

Recently, there has been additional studies of the use of ERAT for<br />

treating acute uncomplicated appendicitis [7,8,9]. The results of these<br />

3 trials indicated the clinical value of ERAT, including both diagnostic<br />

and therapeutic aspects. Thus, ERAT has the potential to become an<br />

alternative treatment method for acute appendicitis, especially in patients<br />

who are deemed as high-risk candidates for surgery. However, these<br />

previous studies were all retrospective, and no prospective study has<br />

been reported yet. To address this issue, we conducted a prospective<br />

randomized controlled trial to compare ERAT with laparoscopic<br />

appendectomy (LA) and open appendectomy (OA), and evaluated the<br />

feasibility and safety of ERAT in treating acute uncomplicated appendicitis.<br />

Method<br />

Patients<br />

The period of patient enrollment was between January 2018 and August<br />

2019. A prospective, open-label, randomized controlled study was<br />

conducted at Jinshan Hospital, Fudan University. Patients diagnosed<br />

with acute uncomplicated appendicitis were enrolled in the study.<br />

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patient age over 18 years and<br />

under 80 years; (2) Alvarado score >5 [1]; (3) suspicious (or could not<br />

be excluded) acute appendicitis diagnosed by an abdominal CT scan,<br />

which was indicated by a dilated appendix with a diameter greater than<br />

6 mm, a thickened cecal wall, and periappendiceal fat inflammation, with<br />

or without an appendicolith [10].<br />

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) suspected acute complicated<br />

appendicitis with perforation or gangrene; (2) appendiceal diameter

FEATURE<br />

Fig. 1 Procedures of endoscopic retrograde appendicitis therapy (ERAT). a Congestion and edema around the mucosa of appendix orifice. b The<br />

endoscopic retrograde appendicography (ERA) fluoroscopy showed filling defect in the appendix lumen (arrows), which indicated the presence<br />

of appendicoliths. c Cannulation of catheter along the guidewire with sand-like appendicoliths excretion and pus drainage inside the appendix<br />

lumen, confirming acute appendicitis. d Retracting the appendicoliths by the extraction basket. e After appendicolith being retracted, the appendix<br />

lumen was fully filled with contrast media under ERA. f Stenting for keeping pus drainage<br />

greater than 15 mm, which usually indicates malignancy [11]; (3)<br />

patients under the age of 18 years or over 80 years; (4) patients<br />

with the following contradictions for receiving colonoscopy, surgery<br />

or anesthesia: (a) severe cardiopulmonary insufficiency, psychiatric<br />

dysfunction or coma; (b) acute diffuse peritonitis, which is defined<br />

as diffuse abdominal tenderness, rebound tenderness and muscular<br />

tension; (c) acute gastroenteritis (dysentery, explosive ulcerative colitis);<br />

(d) concurrent menses; (e) intestinal obstruction; (f) acute gastrointestinal<br />

hemorrhage; (g) recent gastrointestinal or pelvic operation or<br />

radiotherapy; (h) allergy to contrast medium; (i) hemorrhagic tendency<br />

because of long-term use of corticosteroids or anticoagulant treatment;<br />

(5) patients undergoing any other clinical trial.<br />

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study<br />

was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and approved<br />

by the Ethics Committee of Jinshan Hospital, Fudan University (No.<br />

2017–24) on May 17th, 2017. The study is registered with the WHO<br />

Primary Registry-Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR1900025812)<br />

(09/09/2019).<br />

Randomization was conducted by a computer-generated randomization<br />

number (1:1:1) by statisticians. The final allocation was concealed in<br />

an opaque envelope. The allocation was reported to the doctors and<br />

patients immediately prior to the intervention.<br />

Preintervention preparation<br />

All patients intravenously received antibiotic treatment (1.5 g cefuroxime<br />

with 100 ml normal saline, 0.5% metronidazole 100 ml) immediately<br />

after being clinically diagnosed. In the ERAT group, the patients orally<br />

took 328.8 g polyethylene glycol (PEG) electrolyte solution with 2000 ml<br />

water before ERAT for bowel preparation. When the excrement became<br />

a clear liquid, the patients were well prepared to undergo ERAT.<br />

ERAT procedure<br />

Similar to that in previous studies [7,8,9], the ERAT procedure was<br />

performed as follows (Fig. 1):<br />

First, a full and careful examination of the large intestine was performed<br />

by a colonoscope (CF-H260AI, Olympus, Japan) with a transparent cap.<br />

Then, the colonoscope was located to the appendiceal orifice to check<br />

the appendiceal mucosa to determine whether there was inflammation<br />

or any other abnormalities. With the help of a transparent cap, the tip<br />

of the catheter (BDC-12/55–7/1810/55–7/18, Micro-Tech Co. Ltd.,<br />

Nanjing, China) was placed in the appendiceal orifice, and a 0.035-inch<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SPRING <strong>2022</strong><br />

15

FEATURE<br />

guidewire (MTN-BM-89/45-A, Micro-Tech Co. Ltd., Nanjing, China) was<br />

gently and deeply inserted into the appendiceal lumen over the catheter.<br />

Finally, the catheter moved forward into the appendiceal lumen along<br />

the guidewire. To make a definite diagnosis, the appendiceal lumen<br />

was filled with contrast medium (ioversol) for endoscopic retrograde<br />

appendicography (ERA) fluoroscopy. Next, the appendiceal lumen was<br />

flushed repeatedly with gentamicin (240,000 units with 100 ml normal<br />

saline) and 0.5% metronidazole 100 ml to clear pus and other infectious<br />

contents, such as sand-like appendicoliths. Then, an extraction basket<br />

(SEB-A- 30/55–7/200, Micro-Tech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) was used<br />

to extract the remaining appendicoliths if necessary. Finally, a plastic<br />

stent (SPSOF7-7, Cook, USA) was placed routinely in the appendiceal<br />

orifice to maintain pus drainage.<br />

Surgical treatment<br />

All operations were performed by surgeons from a same team. In the<br />

LA group, the three-port technique (umbilical, 10 mm; suprapubic, 5<br />

mm; right lower abdomen, 10 mm) was chosen. In the OA group, a<br />

McBurney muscle-splitting incision technique was used.<br />

and CRP level; the duration of diet resumption; the length of hospital<br />

stay (LOS); the total cost of the primary hospital stay; adverse events<br />

during follow-up period and final crossover rate of ERAT to surgery.<br />

Definition<br />

The clinical success of ERAT is defined as successful appendix<br />

cannulation with complete resolution of symptoms and normalization<br />

of inflammatory markers, including WBC count, neutrophil percentages<br />

and CRP. Difficult appendix cannulation is defined as failure to achieve<br />

successful appendix cannulation within 15 min. The assessment of<br />

abdominal pain degree is based on visual analog scales (VAS). In the<br />

VAS, scores of 0 and 10 represent no pain and most severe pain,<br />

respectively. Complete relief of abdominal pain refers to a VAS score of<br />

0.<br />

The diagnostic criteria of acute appendicitis by ERAT mainly consist<br />

of ERA fluoroscopy images, inflammation of the appendiceal mucosa<br />

observed under endoscopy and the presence of pus or appendicoliths<br />

inside the appendiceal lumen [8].<br />

GASTROENTEROLOGY TODAY - SPRING <strong>2022</strong><br />

16<br />

Postintervention management<br />

After ERAT or surgery was performed, patients were sent back to the<br />

ward and monitored carefully. Patients continued to receive antiinflammatory<br />

therapy when necessary. In the ERAT group, patients<br />

were given a soft diet later on the same day and resumed a normal diet<br />

when the soft diet was tolerated. In the LA and OA groups, a soft diet<br />

was started 24 h after surgery, and a normal diet was given when the<br />

soft diet was completely tolerated. All patients were asked about their<br />

clinical presentation every day. Routine blood tests, including the white<br />

blood cell (WBC) count, neutrophil percentages and C-reactive protein<br />

(CRP) level, were performed on day 1, 3, and 5 in a similar fashion after<br />

ERAT or surgery. Patients were discharged when all symptoms were<br />

completely relieved and inflammatory markers (including the WBC count,<br />

neutrophil percentages, and CRP level) returned to normal. If ERAT<br />

failed or abdominal pain persisted after ERAT, LA or OA was performed<br />

immediately.<br />

Follow-up<br />

Fourteen days after ERAT, all patients in the ERAT group were scheduled<br />

for outpatient services to inform doctors of their symptoms after<br />

discharge. Patients then received an abdominal X-ray to check the<br />

status of the stent. If the stent was not discharged spontaneously with<br />

defecation, colonoscopy was recommended to retrieve the stent.<br />

Follow-up was performed by telephone interview every 3 months for<br />

the first half year, and then every 6 months till November 2020. In<br />

the ERAT group, recurrence of abdominal pain or appendicitis after<br />

ERAT, including the relevant treatment, was mainly investigated. In the<br />

LA group and OA group, the survey mainly included postoperative<br />

complications such as wound infection, persistent incision pain and<br />

intestinal obstruction. Follow-up was performed until the end of the<br />

study period.<br />

Outcomes<br />

The primary outcome was the clinical success of the treatment. The<br />

secondary outcomes were as follows: the duration of complete relief of<br />

abdominal pain and body temperature; the duration of normalization of<br />

inflammatory markers including the WBC count; neutrophil percentages<br />

In the ERAT group, adverse events mainly indicated the recurrence of<br />

acute appendicitis. In the LA and OA groups, adverse events suggested<br />

postoperative complications.<br />

Statistical analysis<br />

As this was a pilot trial, we did not perform a power calculation. On the<br />

basis of our yearly caseload of approximately 240 cases and estimated<br />

recruitment of one fifth of eligible cases, we aimed to enroll at least<br />

96 patients within a 2-year period. Qualitative data are expressed as<br />

numbers (n) and percentages (%) and were compared by using the χ 2<br />

test or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate.<br />

Quantitative data are expressed as the mean ±standard deviation<br />

(SD) or median with 25th and 75th percentiles, as appropriate. For<br />

normally distributed quantitative data (such as age, temperature, WBC<br />

count), one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare<br />

the differences among the three groups. For nonnormally distributed<br />

quantitative data (neutrophil percentages, CRP, Alvarado scores, VAS<br />

scores, the duration of normalization of inflammatory markers, the<br />

duration of normal diet and body temperature, total cost and length of<br />

hospitalization), the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by all pairwise multiple<br />

comparisons was used to detect statistical significance. Bonferroni’s<br />

correction was used for multiple hypothesis testing. The data were<br />

analyzed by IBM SPSS software version 22 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois,<br />

USA). A P value

FEATURE<br />

Fig. 2 Trial profile<br />

Appendicoliths were present in 12 patients (36.36%) in the ERAT group,<br />

16 patients (48.48%) in the LA group and 11 patients (33.33%) in the<br />

OA group. There were no significant differences in appendicoliths among<br />

the three groups (p =0.516).<br />

Treatment success rate and efficacy of ERAT<br />

Table 2 shows the clinical outcomes of the three groups. Successful<br />

treatment was achieved in 29 patients (87.88%) in the ERAT group,<br />

32 patients (96.97%) in the LA group and 33 patients (100%) in the<br />

OA group. No significant differences were observed among the three<br />

groups (P=0.123). Among the three groups, ERAT failed in four patients<br />

(12.12%) due to difficult cannulation, and LA was performed in these<br />

patients later on the same day, with uneventful recoveries. All these<br />

four patients were found appendicoliths before ERAT. Appendicoliths<br />

of the other 8 patients who were found to have appendicoliths by CT<br />

scan were removed by ERAT. Stents were placed in 29 patients with<br />

successful ERAT. In the LA group, a 63-year-old patient failed LA due<br />

to extensive abdominal adhesion caused by surgical reduction for<br />

intussusception 3 years ago. The patient was later converted to OA<br />

successfully.<br />

Among 29 patients who underwent successful ERAT, most achieved<br />

complete abdominal pain relief immediately after the procedure. The<br />

duration of normalization of inflammatory markers, including the WBC<br />

count, neutrophil percentages and CRP level, did not significantly differ<br />

among the ERAT, LA and OA groups (P =0.351, P=0.607, P=0.147,<br />

respectively). The overall cost in the LA group was significantly<br />

higher (P

FEATURE<br />

Table 1 Basic characteristics<br />

ERAT group (n=33) LA group (n=33) OA group<br />

(n=33)<br />