ZEKE Magazine: Fall 2021, Interview with Joseph Rodriguez

Joseph Rodriguez is a New York-based photographer whose career spans over 25 years. His work has been published in National Geographic, The New York Times Magazine, Mother Jones, Newsweek, New York Magazine and others. He teaches at NYU and the International Center for Photography (ICP), among others, and has published several books including, more recently: Taxi: A Journey Through My Window 1977-1987 and LAPD 1994. Below is an excerpt from our conversation, edited for clarity.

Joseph Rodriguez is a New York-based photographer whose career spans over 25 years. His work has been published in National Geographic, The New York Times Magazine, Mother Jones, Newsweek, New York Magazine and others. He teaches at NYU and the International Center for Photography (ICP), among others, and has published several books including, more recently: Taxi: A Journey Through My Window 1977-1987 and LAPD 1994. Below is an excerpt from our conversation, edited for clarity.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

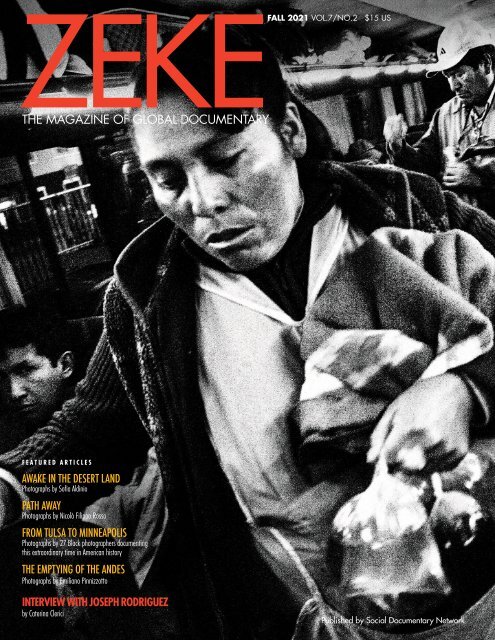

<strong>ZEKE</strong>FALL <strong>2021</strong> VOL.7/NO.2 $15 US<br />

THE MAGAZINE OF GLOBAL DOCUMENTARY<br />

FEATURED ARTICLES<br />

AWAKE IN THE DESERT LAND<br />

Photographs by Sofia Aldinio<br />

PATH AWAY<br />

Photographs by Nicolò Filippo Rosso<br />

FROM TULSA TO MINNEAPOLIS<br />

Photographs by 27 Black photographers documenting<br />

this extraordinary time in American history<br />

THE EMPTYING OF THE ANDES<br />

Photographs by Emiliano Pinnizzotto<br />

INTERVIEW WITH JOSEPH RODRIGUEZ<br />

by Caterina Clerici<br />

Published by Social Documentary <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL Network <strong>2021</strong>/ 1

<strong>Interview</strong><br />

JOSEPH RODRIGUEZ<br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Rodriguez</strong> is a New York-based photographer<br />

whose career spans over 25 years. His<br />

work has been published in National Geographic,<br />

The New York Times <strong>Magazine</strong>, Mother Jones,<br />

Newsweek, New York <strong>Magazine</strong> and others. He<br />

teaches at NYU and the International Center<br />

for Photography (ICP), among others, and has<br />

published several books including, more recently:<br />

Taxi: A Journey Through My Window 1977-1987<br />

and LAPD 1994. Below is an excerpt from our<br />

conversation, edited for clarity.<br />

By Caterina Clerici<br />

Caterina Clerici: Can you tell us about<br />

your background and how you got<br />

started in photography?<br />

and then dropped out and then got into<br />

the drug scene, started doing heroin,<br />

selling heroin, all that bad boy stuff. I<br />

went to Rikers Island. First time I went in, I<br />

was 17 years old. The second time I was<br />

20, and I was a much tougher guy than<br />

when I first went in. Rikers Island is not<br />

a place that I can even describe to you.<br />

How horrible that place is, that’s a whole<br />

other story.<br />

However, I came out at a very interesting<br />

time because I felt the need to change<br />

and those were the times of affirmative<br />

action, the only way for most young people<br />

to go to college <strong>with</strong>out the ugly bank<br />

loans we have today. Through education<br />

I got myself together: got off methadone<br />

at 26, got my GED and studied graphic<br />

arts technology at the New York City<br />

Technical College in downtown Brooklyn.<br />

In 1980, I came out of school — first one<br />

to go to college in my family — and got<br />

a job in the printing business. You would<br />

send us your chromes, and we would<br />

make negatives, make plates and put<br />

them on a printing press. I learned a lot<br />

about color and printing and that helped<br />

my photography later on.<br />

I was making a lot of money in ‘80,<br />

‘81, doing all those big ads you see<br />

on the front pages of magazines, but I<br />

found myself going back down a rabbit<br />

hole, working 50, 60 hours a week. It<br />

was a great experience, but I was really<br />

unhappy. So I quit my job. My mother<br />

was very upset. I went back to driving<br />

a cab (taking photos that made up Taxi:<br />

Journey Through My Windows 1977-<br />

1987) and worked <strong>with</strong> a friend who had<br />

a truck and an art moving business.<br />

One day we delivered to a gallery in<br />

Soho where Larry Clark was laying his<br />

whole life’s work up on the wall. I went<br />

up to him as if he was Jimi Hendrix, like,<br />

“Oh, man! I really want to do what you<br />

do!” and he said: “Just go make pictures.”<br />

That’s all he said to me.<br />

I went to ICP and started assisting in<br />

the dark room, cleaning up the cibachrome<br />

lab. Then they gave me a scholarship<br />

and my life changed. I was schooled<br />

by some of the greatest Magnum photographers:<br />

Gilles Peress, Susan Meiselas,<br />

Eugene Richards, Alex Webb, Raymond<br />

Depardon, Sebastiao Salgado. The way<br />

I work is the way they work. For weeks,<br />

months and years. Anything personal is<br />

going to take me years. I’m just coming<br />

off following Mexican migrants throughout<br />

the USA for 10 years.<br />

I think about photography in time, and<br />

I always felt great work takes a lot of it.<br />

And, for me, it was always self-initiated.<br />

There were no editors, no one telling me<br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Rodriguez</strong>: I was born and<br />

raised in Brooklyn in 1951. I grew up<br />

where I live right now, Park Slope, but it<br />

was South Brooklyn then. And you know,<br />

the Italian American history in New York<br />

was very strong. It was a very mafioso<br />

neighborhood and I’m not lying — we<br />

had the Gowanus Canal and it was not<br />

unusual for us to see floating bodies… It<br />

was pretty much like the old Sicilian way.<br />

In my Catholic school there were<br />

only about 400 or 500 of us. There was<br />

one Black kid and one Puerto Rican kid:<br />

me. The other kids were all mostly from<br />

Genoa, in Italy. Every single parent who<br />

lived close by used to grow grapes in<br />

the backyard and you would stop by to<br />

try their wine. It was very old school.<br />

But then the drugs came, and that’s what<br />

brought a lot of the same problems you<br />

have in so many other places.<br />

I lost my way… got into high school<br />

A young 18th Street Gang member being arrested. At the time this photo was taken the ATF (Arms Tobacco and<br />

Firearms) were working <strong>with</strong> LAPD to try and take down one of the most notorious gangs in Los Angeles. The aim<br />

was also to get as many guns off the streets as possible. Photo by <strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Rodriguez</strong> from LAPD 1994.<br />

2 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

what to do. We just had that practice,<br />

that discipline, which also brings a lot<br />

of anxiety because you’re swimming<br />

upstream and you’re always alone. The<br />

practice is mapping out a story, which<br />

then turns into something longer — like<br />

when I went to LA in 1992 to photograph<br />

gangs and I’m still revisiting that project<br />

some 20 years later.<br />

CC: Can you tell us how your project<br />

on gang violence in LA started, how it<br />

evolved, and the challenges you faced?<br />

JR: When the Rodney King uprising<br />

happened, immediately I wanted to<br />

go, because I was missing America<br />

(<strong>Rodriguez</strong> was living in Europe at the<br />

time) and I understand the urban narrative,<br />

no matter which city it is — Chicago,<br />

Miami, New York, LA. I couldn’t do much<br />

research while I was living in Europe,<br />

because it wasn’t like now where everything’s<br />

online, but one thing I did was listen<br />

to music: all this gangsta rap, Eazy-E,<br />

Tupac, Dre, N.W.A., Public Enemy. The<br />

rhymes they were spitting out were the<br />

newspapers of the streets. So I was listening<br />

to guys like this Chicano rapper Kid<br />

Frost, who’s totally East LA, and I was like<br />

“Ok, I gotta go there.”<br />

I flew in the middle of the night from<br />

Stockholm to LA and arrived in my hotel<br />

room. I didn’t know where I was going,<br />

I had no connections and LA is huge!<br />

So I grabbed three newspapers, turned<br />

on the news and of course there was a<br />

funeral and a drive-by shooting every<br />

minute.<br />

There was a lot of ground to cover,<br />

so I stayed five weeks and worked<br />

really hard. No sleep, just worked and<br />

drove around, from one neighborhood<br />

to another, also <strong>with</strong> the cops doing the<br />

gang unit. But I knew our history already.<br />

I began interviewing African-American<br />

families in Watts, asking what was the<br />

difference <strong>with</strong> the riots in 1965, in the<br />

era when Malcolm X and Robert Kennedy<br />

were assassinated and there was a lot<br />

of city streets burning. The conversation<br />

began and it opened up doors, and I<br />

realized I wasn’t interested in just the<br />

guns or the people dying. This was a<br />

generational story that went back three or<br />

Waiting for a fare outside 220 West Houston Street, an after-after-hours club. New York 1984. Photo by <strong>Joseph</strong><br />

<strong>Rodriguez</strong> from Taxi: A Journey Through My Window 1977-1987.<br />

four generations. That’s when I really felt<br />

the power of this story.<br />

I went back to Stockholm and we published<br />

what we could. I applied for an artist<br />

grant there, and then I moved to LA in<br />

September of ‘92. It was hard, I had left<br />

the kids behind and just kept flying back,<br />

trying not to be the absentee father that I<br />

was. But that was the path I was on.<br />

The gang project was very hard to<br />

do and I paid the psychological price<br />

for it, in terms of PTSD. At least eleven<br />

kids are dead, in the East Side Stories:<br />

Gang Life in East L.A. book. Children<br />

were dying and parents were telling me<br />

I needed to tell this story. Plus, sometimes<br />

people thought I was an undercover cop.<br />

I showed them my Spanish Harlem book<br />

and my National Geographic stories to<br />

prove that I wasn’t a cop, but paranoia<br />

runs deep in the hood. That hung over my<br />

head for a while — until the book was<br />

published — and I was going to quit the<br />

project, I felt I couldn’t handle it.<br />

I also had guys come say to me: “Yo,<br />

man, I’m about to go do a hit, you can<br />

come and just take pictures.” This is ethics.<br />

I said: “Look, I go <strong>with</strong> you, I photograph<br />

you doing this scene. Detectives<br />

come, they find out who’s who, they<br />

take my film and they use the evidence<br />

against you.” Some of the gang members<br />

were 16 years old; they didn’t know how<br />

the law worked. They didn’t understand<br />

what a camera could do. They were so<br />

enamored by their vanity and Hollywood<br />

influence. With a camera comes a lot of<br />

responsibility.<br />

CC: How did your surroundings while<br />

growing up influence your practice and<br />

your understanding of photography, as<br />

well as your mission as a “humanist”, as<br />

you often define yourself?<br />

JR: I grew up <strong>with</strong> my mother and her<br />

sisters, and there were no men in my family.<br />

My stepfather was a dope fiend who<br />

died on the streets. There were a lot of<br />

not nice things growing up, and that was<br />

very tough for me.<br />

One thing I remember is that my mom<br />

would sit <strong>with</strong> her sisters in a very old<br />

school, Italian way, they would have their<br />

coffee and talk about the men. I would<br />

hear these stories — it was unbelievable<br />

— of abuse and cheating, and those references<br />

helped me develop a feminine eye.<br />

I’m always asking myself: “Why did<br />

this photographer go photograph a gangster<br />

<strong>with</strong> guns, bullets and drugs, but then<br />

didn’t photograph a mother at the same<br />

time, or the struggling parent?” That’s<br />

always been very important in my work. I<br />

didn’t always go for the guns.<br />

“Raised in violence, I enacted my own<br />

violence upon the world and upon myself.<br />

What saved me was the camera, its ability<br />

to gaze upon, to focus, to investigate,<br />

to reclaim, to resist, to re-envision.” That<br />

quote is from my journal. That’s how I<br />

got here, that’s where this goal comes<br />

from. That’s why I went back for East Side<br />

Stories (<strong>Rodriguez</strong>’s long-term project<br />

about gang violence in LA, shot between<br />

1992–2017.)<br />

Continued on page 70.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 3

A COMPELLING AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL<br />

COMMENTARY BY KEITH FLYNN & CHARTER WEEKS<br />

Both the Great Recession that began<br />

in 2008 and the more recent global<br />

pandemic provide the backdrop<br />

for these remarkable portraits and<br />

testimonies of the people who do<br />

their best to survive <strong>with</strong> the odds<br />

stacked against them.<br />

- Glenn Ruga<br />

Social Documentary Network<br />

Featuring Photographs<br />

by Charter Weeks and<br />

Text by Keith Flynn<br />

Pre-Order your Copy Now<br />

https://tinyurl.com/RedhawkProsperityGospel<br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Rodriguez</strong><br />

Continued from page 53.<br />

CC: With regard to the ongoing conversation<br />

about minorities and underrepresented<br />

communities reclaiming ownership<br />

of the narrative in the media, what do<br />

you think is the value of having someone<br />

from inside a community documenting<br />

it, as opposed to someone from outside?<br />

How do you see social media affecting<br />

the process?<br />

JR: I remember people used to tell me:<br />

“You’re not gonna make any money<br />

shooting Black and brown people.” That<br />

was racist. I had to let it roll off my back<br />

and say, “Okay, we’ll get there.”<br />

When National Geographic published<br />

“Growing up in East Harlem” in May<br />

1990, it was a cover story, World Press<br />

Photo-winning, all these awards, 26<br />

pages. It was the proudest day of my life<br />

when it was published: I was in Spanish<br />

Harlem at the library <strong>with</strong> my magazine,<br />

and these little chavelitos (young kids)<br />

were reading it being like “Wow! This is<br />

my neighborhood!”<br />

Some time later, several of the editors<br />

at the magazine told me they felt they<br />

should not be doing stories about poverty<br />

in America. And I said to myself: “Wait<br />

a minute, you mean to tell me I can go to<br />

Ethiopia and show bare breasted, starving<br />

women and that’s okay?” After doing<br />

another story in Africa I chose not to<br />

work for them. All of a sudden, 10 years<br />

ago they’re going back and looking at<br />

many of their stories through a colonialist<br />

lens, 'cause now it’s the 21st century<br />

and everybody calls you up on social<br />

networks.<br />

Social media has given many people<br />

a voice. I put a lot of my work there<br />

because the younger generations don’t<br />

read, they don’t go to libraries or look at<br />

books. Social media is giving a platform<br />

for many of us to see and read.<br />

There’s one thing I want to make clear<br />

though: just because I’m Latino, I’m a<br />

photographer who happens to be Latino,<br />

I’m not a Latino photographer. That’s not<br />

how I label myself.<br />

Ethnicity should not have to do <strong>with</strong><br />

what you represent — although that’s<br />

shifted, and there’s a lot of Black folks out<br />

there that are pushing the Black narrative,<br />

a lot of Latinos pushing the Latino narrative,<br />

a lot of women pushing the women<br />

narrative, a lot of trans folks pushing the<br />

trans narrative. Everybody’s out there trying<br />

to do something, and that’s okay. But<br />

it’s very easy to get pigeonholed like in my<br />

case: “Hire Joe, he’ll shoot AIDS. He’ll do<br />

drug addicts, dope fiends and gangsters.”<br />

I don’t look at what color or gender<br />

you are. I don’t care where you come<br />

from, what your class status is. If you’re<br />

putting the time in, if you’re willing to<br />

listen, you can do good work. I don’t like<br />

the way the conversations are going right<br />

now where, “Oh, you’re white, you’re<br />

not allowed to do this project,” or “You’re<br />

Black, you’re not allowed to do that<br />

project.” Photography has always been<br />

universal, as far as I’m concerned.<br />

4 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Subscribe to <strong>ZEKE</strong><br />

$25.00* for two issues/year<br />

Includes print and digital<br />

*Additional costs for shipping outside the US.<br />

Subscribe to <strong>ZEKE</strong> magazine and get the best of<br />

global documentary photography delivered to your<br />

door, and to your digital device, twice a year. Each<br />

issue presents outstanding photography from the<br />

Social Documentary Network on topics as diverse<br />

as the war in Syria, the European migration crisis,<br />

Black Lives Matter, the Bangladesh garment industry,<br />

and other issues of global concern.<br />

But <strong>ZEKE</strong> is more than a photography magazine.<br />

We collaborate <strong>with</strong> journalists who explore<br />

these issues in depth —not only because it is important<br />

to see the details, but also to know the political<br />

and cultural background of global issues that require<br />

our attention and action.<br />

Click here to find out how »<br />

www.zekemagazine.com/subscribe<br />

Contents of <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2021</strong> Issue<br />

Awake in the Desert Land<br />

Photographs by Sofia Aldinio<br />

Path Away<br />

Photographs by Nicolò Filippo Rosso<br />

From Tulsa to Minneapolis: Photographing the<br />

Long Road to Justice<br />

Photographs by 27 Black photographers documenting this<br />

extraordinary time in American history<br />

The Emptying of the Andes<br />

Photographs by Emiliano Pinnizzotto<br />

Migration from the Northern Triangle<br />

by Daniela Cohen<br />

<strong>Interview</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Rodriguez</strong><br />

by Caterina Clerici<br />

Photography & Social Change<br />

by Emily Schiffer<br />

Book Reviews<br />

Edited by Michelle Bogre<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 5