ZEKE Magazine: Fall 2021, Preview edition

Subscribe and read full version.

Subscribe and read full version.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

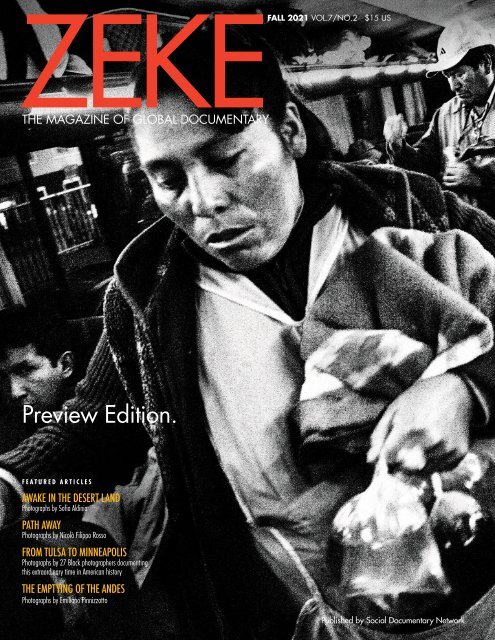

<strong>ZEKE</strong>FALL <strong>2021</strong> VOL.7/NO.2 $15 US<br />

THE MAGAZINE OF GLOBAL DOCUMENTARY<br />

<strong>Preview</strong> Edition.<br />

FEATURED ARTICLES<br />

AWAKE IN THE DESERT LAND<br />

Photographs by Sofia Aldinio<br />

PATH AWAY<br />

Photographs by Nicolò Filippo Rosso<br />

FROM TULSA TO MINNEAPOLIS<br />

Photographs by 27 Black photographers documenting<br />

this extraordinary time in American history<br />

THE EMPTYING OF THE ANDES<br />

Photographs by Emiliano Pinnizzotto<br />

Published by Social Documentary <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL Network <strong>2021</strong>/ 1

FALL <strong>2021</strong> VOL.7/NO.2<br />

$15 US<br />

2 | AWAKE IN THE DESERT LAND<br />

Photographs by Sofia Aldinio<br />

CO-WINNER OF <strong>2021</strong> <strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD FOR DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY<br />

Sofia Aldinio from Awake in the Desert Land<br />

Nicolò Filippo Rosso from Path Away<br />

Joshua Rashaad McFadden from From Tulsa to<br />

Minneapolis: Photographing the Long Road to<br />

Justice<br />

Emiliano Pinnizzotto from The Emptying of the<br />

Andes<br />

14 | PATH AWAY<br />

Photographs by Nicolò Filippo Rosso<br />

CO-WINNER OF <strong>2021</strong> <strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD FOR DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY<br />

40 | FROM TULSA TO MINNEAPOLIS:<br />

PHOTOGRAPHING THE LONG ROAD TO JUSTICE<br />

Photographs by 27 Black photographers documenting this<br />

extraordinary time in American history<br />

60 | THE EMPTYING OF THE ANDES<br />

Photographs by Emiliano Pinnizzotto<br />

26 |<br />

30 |<br />

52 |<br />

54 |<br />

70 |<br />

Migration from the Northern Triangle<br />

The Last Resort to Stay Alive<br />

by Daniela Cohen<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> Award Honorable Mention Winners<br />

Interview with Joseph Rodriguez<br />

by Caterina Clerici<br />

Photography & Social Change<br />

by Emily Schiffer<br />

Book Reviews<br />

Edited by Michelle Bogre<br />

78 | Contributors<br />

Deborah Espinosa from Photography & Social<br />

Change<br />

On the Cover<br />

Photo by Emiliano Pinnizzotto from The Emptying<br />

of the Andes. Inside a bus heading in the direction<br />

of Lima. Many of the people inside the bus are<br />

leaving their homes forever, looking for a job and<br />

a better life in the cities. See inside back cover for<br />

a profile of Emiliano Pinnizzotto.

<strong>ZEKE</strong><br />

THE<br />

MAGAZINE OF<br />

GLOBAL DOCUMENTARY<br />

Published by Social Documentary Network<br />

Dear <strong>ZEKE</strong> Readers:<br />

As I write this letter, Hurricane Ida has just completed its deadly flooding and destruction in Louisiana and the<br />

Northeast exactly 16 years after Katrina devastated the Gulf Coast. Floods have killed 20 people in Tennessee.<br />

Wildfires rage in the West and in Europe. And the Delta variant of COVID-19 extends its grip.<br />

It has also been just a few weeks since the fall of Kabul as the Taliban swept into victory following the<br />

American pullout after our 20-year failed effort at nation building. Now a chaotic and deadly evacuation<br />

has ended for U.S. troops, American citizens, our Afghan allies, and nationals of other countries struggling<br />

to flee the imposition of a harsh and despotic rule that we all know too well from the years prior to 9/11<br />

when the Taliban last controlled Afghanistan.<br />

While none of these events are presented in this issue of <strong>ZEKE</strong>, prior issues have featured numerous<br />

articles on climate change and the U.S. "War on Terror." We continue to publish <strong>ZEKE</strong> because we stand<br />

resolutely behind the importance of the documentary image, and the photographers who make them, in<br />

bringing awareness, nuance, and humanity to global issues.<br />

In this issue of <strong>ZEKE</strong>, we are thrilled to present the winners of the <strong>2021</strong> <strong>ZEKE</strong> Award for Documentary<br />

Photography. Sofia Aldinio’s award-winning project, Awake in the Desert Land, explores migration and historical<br />

memory as residents from Baja California, Mexico are uprooted from their land as a result of climate<br />

change. Nicolò Filippo Rosso’s project, Path Away, follows migrants from the Northern Triangle countries<br />

(Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador), as they flee violence and climate change to seek better opportunities<br />

in the U.S. only to find the border sealed as they approach their destination.<br />

We also present the extraordinary images by Italian photographer Emiliano Pinnozzotto and his project,<br />

The Emptying of the Andes, documenting an important, under-reported, and all too common story, where<br />

young people are fleeing their ancestral mountainous homes only to find a new form of poverty and alienation<br />

in urban centers—in this case in Peru—as climate change makes it increasingly difficult to sustain life<br />

at 13,000 feet.<br />

It is no coincidence that migration is a central theme in these three exhibits as the existential threat of<br />

climate change forces millions of people each year to seek less vulnerable environments.<br />

We are also thrilled to present 27 submissions from a call for entries from Black photographers on the<br />

theme “From Tulsa to Minneapolis: Photographing the Long Road to Justice” including first-place winner<br />

Donald Black Jr. for his story A Day No One Will Remember.<br />

In addition to these portfolios, Emily Schiffer has written a very provocative and inspiring feature article<br />

on Photography and Social Change exploring photographic artists who are making a difference by challenging<br />

the norms of both imagemaking and traditional structures of power.<br />

Lastly, on a personal note, I am very saddened to report that the namesake<br />

for <strong>ZEKE</strong> magazine, our thirteen-year-old beloved feline companion Ezekiel<br />

(aka Zeke), passed away in July following injuries suffered from a valiant fight<br />

with a wild animal. Barbara and I take solace that his exuberance for life, his<br />

unbounding energy, and his persistent demand for dignity often denied our<br />

non-human friends, live on in this magazine.<br />

Matthew Lomanno<br />

Glenn Ruga<br />

Executive Editor<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 1

This ongoing photography project<br />

by Sofia Aldinio documents<br />

how climate change is uprooting<br />

small, inland and coastal<br />

communities in Baja California,<br />

Mexico, that depend directly on<br />

natural resources to survive and thereby<br />

threatening cultural heritage.<br />

The peninsula is facing stronger hurricanes,<br />

changes in precipitation patterns<br />

and streamflow, loss of vegetation<br />

and soils and negative impact on fisheries<br />

and biodiversity. It is estimated that<br />

in Mexico and Central America, 3.9<br />

million people will be forced to leave<br />

their homes due to climate change.<br />

Photographed in four different communities<br />

across the peninsula, the work<br />

presented here documents the tension of<br />

the communities whose cultural heritage<br />

is at risk, adds a new perspective on<br />

the existing reports on climate change<br />

and migration and starts a conversation<br />

about how the loss of collective memory<br />

has a direct impact on the mental health<br />

of the next generation.<br />

The newest cemetery in San Jose de<br />

Gracia, Baja California, Mexico,<br />

January 17, <strong>2021</strong>. The small community<br />

has at least four different cemeteries<br />

generationally identified. The town lost<br />

most of its population after Hurricane<br />

Lester in 1992, the biggest storm the<br />

community has faced in its history.<br />

Since 2006, the community has lost 60<br />

members and has a population of 12<br />

today.<br />

2 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Awake in the Desert Land<br />

MIGRATION, CLIMATE CHANGE, AND HISTORICAL MEMORY<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD FIRST-PLACE WINNER<br />

By Sofia Aldinio<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 3

4 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Photo by Sofia Aldinio<br />

Felipe and Olga drive to buy food<br />

for their goats in San Juanico, Baja<br />

California, Mexico, January, 23, <strong>2021</strong>.<br />

The land is parched after no rain for<br />

three years, and the goats have been<br />

having a hard time finding the wild<br />

food that grows in the desert.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 5

PATH<br />

AWAY<br />

TENS OF THOUSANDS FLEE VIOLENCE,<br />

CLIMATE CHANGE, AND ECONOMIC<br />

COLLAPSE FOR NORTH AMERICA<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD FIRST-PLACE WINNER<br />

By Nicolò Filippo Rosso<br />

Two months after Hurricanes Eta and<br />

Iota hit Central America in November<br />

2020, leaving 4.5 million victims of<br />

flooding and mudslides in their wake,<br />

11 thousand people gathered in San<br />

Pedro Sula, Honduras starting the<br />

first migrants’ caravan of the year heading<br />

towards the United States. <strong>2021</strong> began<br />

with one of the most significant migration<br />

waves of the last decade posing a difficult<br />

challenge for the new administration of<br />

President Joe Biden.<br />

The migrants’ crossing through gangcontrolled<br />

areas, deserts, and jungles<br />

is made even harder by the pandemic.<br />

International aid is scant, and many<br />

migrants’ shelters and charity kitchens<br />

closed their doors to avoid contagion.<br />

Thousands of migrants have reached<br />

Mexico while walking along its southern<br />

border with Guatemala, continuing the<br />

migration routes of the Gulf of Mexico, and<br />

the northern border with the United States to<br />

seek asylum. However, hundreds of families<br />

are expelled and returned to Mexico. Their<br />

asylum claims are denied with arguments<br />

based on Title 42, a U.S. statute that allows<br />

the expulsion of migrants from a country<br />

where a virus such as COVID-19 is present.<br />

This is their story.<br />

6 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Left: Lesbia Vanessa Bovadia, 35 years old,<br />

from Honduras, cries as she talks to a psychologist<br />

in a charity shelter in Tijuana, Mexico.<br />

After being separated from her children in the<br />

United States, she was deported to Mexico in<br />

2019. She doesn’t know where her children<br />

are, and she’s desperate to find them. The<br />

last time she saw them was in Chattanooga,<br />

Tennessee in 2018 before being arrested by<br />

the U.S. police.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 7

8 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Photo by Nicolò Filippo<br />

Rosso<br />

Guatemalan police officers take<br />

custody of a Honduran migrant<br />

who attempted to break the police<br />

barricade while driving a truck in<br />

Vado Hondo, Guatemala.<br />

January 18, <strong>2021</strong>.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 9

Migration from the<br />

Phoenix<br />

Channel<br />

Islands<br />

Mexicali<br />

Guadalupe<br />

Hermosillo<br />

A<br />

Chihuahua<br />

G o l f o d e C a l i f o r n i a<br />

La Paz<br />

Culiacan<br />

Durango<br />

MEXICO<br />

Saltillo<br />

Ciudad Victoria<br />

Monterrey<br />

Zacatecas<br />

Aguascalientes San Luis Potos<br />

Tepic<br />

Leon<br />

Queretaro<br />

Guadalajara<br />

Morelia Pachu<br />

Colima<br />

Toluca<br />

Mexico<br />

Chilpancingo<br />

P a c i f i c<br />

Olga Marina Rodriguez<br />

Gonzalez holds her two<br />

babies while waiting for<br />

the cargo train known as La<br />

Bestia “The Beast.” People<br />

jump on the moving train to<br />

reach Northern Mexico, on<br />

their way to the United States.<br />

Coatzacoalcos, in Veracruz,<br />

Mexico. February 16, <strong>2021</strong>.<br />

Photo by Nicolò Filippo Rosso.<br />

O c e a n<br />

10 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Northern Triangle<br />

A last resort to stay alive<br />

by Daniela Cohen<br />

Little Rock<br />

ustin<br />

i<br />

ca<br />

City<br />

MEXICO<br />

Guatemala<br />

The significant increase<br />

in migration from<br />

Central America to the<br />

U.S. in recent years<br />

indicates rapidly deteriorating<br />

conditions<br />

in the region that have left people<br />

no choice but to flee in order to<br />

survive. The majority of migrants<br />

come from Honduras, Guatemala<br />

and El Salvador, together referred<br />

to as the Northern Triangle.<br />

Around 311,000 migrants<br />

from this region arrived in the<br />

U.S. between 2014 and 2020<br />

according to the Congressional<br />

Research Service. In June <strong>2021</strong>,<br />

US Customs and Border Protection<br />

(CBP) recorded almost 180,000<br />

Baton Rouge<br />

GUATEMALA<br />

San Salvador<br />

Jackson<br />

EL SALVADOR<br />

BELIZE<br />

HONDURAS<br />

Tegucigalpa<br />

Managua<br />

Havana<br />

San Jose<br />

Atlanta<br />

Montgomery<br />

NICARAGUA<br />

COSTA RICA<br />

Tallahassee<br />

Columbia<br />

migrants – including 15,000 unaccompanied<br />

minors and 50,000<br />

families – the highest monthly total<br />

in over 20 years. But given that<br />

one third of these migrants have<br />

crossed the border previously, the<br />

actual increase in migration may<br />

not be as high.<br />

“It’s one of the hardest decisions<br />

people are often making,” says<br />

Andani Alcantara Diaz, supervising<br />

attorney of removal defense for<br />

the Refugee and Immigrant Center<br />

for Education and Legal Services<br />

(RAICES) in Austin, Texas. “That’s<br />

why you see people go through<br />

really horrible things and still not<br />

leave for a while because they<br />

don’t want to leave their homes,<br />

their families, everything they<br />

know, behind. But at a certain<br />

point, it’s the only thing they can<br />

do to stay alive.”<br />

The main drivers of migration<br />

from the Northern Triangle are violence<br />

and socioeconomic insecurity,<br />

which frequently overlap, and are<br />

exacerbated by climate change.<br />

“Many migrants are fleeing<br />

gangs or other sorts of dangerous<br />

organizations that have harmed<br />

them and their families,” says<br />

Alcantara Diaz, “And they know<br />

they can’t go to the government,<br />

that the government in their countries<br />

is not going to protect them.”<br />

Many of these gangs originated<br />

in Los Angeles in the 1980s and<br />

were later deported back to their<br />

home countries in the region.<br />

Women and children are<br />

particularly vulnerable to violence,<br />

often within the home. Honduras<br />

and El Salvador have some of the<br />

highest rates of femicide worldwide.<br />

Endemic corruption means<br />

that the police are often involved<br />

and those responsible are not held<br />

to account. The threat of violence<br />

by both gangs and family members<br />

has led to a surge in unaccompanied<br />

minors arriving at the U.S.<br />

border since 2014.<br />

Socioeconomic drivers of migration<br />

include widespread inequality<br />

and poverty and pervasive lack<br />

CUBA<br />

JAMAICA<br />

Panama<br />

Bahama<br />

Islands<br />

Nassau<br />

Long Island<br />

G r e a t e r A n t i l l e s<br />

Caribbean Sea<br />

of work opportunities. With 40<br />

percent of the population under the<br />

age of 20, youth can either stay in<br />

precarious working conditions or<br />

try to seek opportunities elsewhere.<br />

Climate change has led to prolonged<br />

droughts and crop losses.<br />

The coffee industry has been hit<br />

hard by both an increase in the<br />

coffee leaf rust fungus and low<br />

international coffee prices, jeopardizing<br />

a critical source of seasonal<br />

income for over a million families.<br />

In addition, in 2020, the region<br />

was devastated by the COVID<br />

pandemic and back-to-back category<br />

4 Hurricanes Eta and Iota,<br />

which displaced over 500,000<br />

people, leaving many homeless<br />

and without access to clean<br />

drinking water. According to the<br />

World Food Programme, approximately<br />

eight million people are<br />

facing hunger, including a quarter<br />

with emergency levels of food<br />

insecurity. Almost 15 percent of<br />

people surveyed in January <strong>2021</strong><br />

reported plans to migrate, up eight<br />

percent from 2018.<br />

A Migrant Family’s<br />

Journey<br />

Angel Antonio Mejia Gonzales,<br />

from Danli, Honduras, felt he<br />

had no choice but to leave. The<br />

33-year-old and his wife, Olga<br />

Marina Rodriguez Montoya, 27,<br />

had both been affected by violence<br />

and wanted to protect their<br />

children. Mejia Gonzales is eager<br />

to work but says there were no<br />

prospects for work in Honduras.<br />

And Hurricanes Eta and Iota took<br />

what little they had.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 11

FROM TULSA TO MINNEAPOLIS<br />

Photo by Joshua Rashaad<br />

McFadden<br />

After the last speech at the<br />

Commitment March Rally on<br />

August 28, 2020, thousands<br />

of people flooded the streets of<br />

Washington, D.C., to protest<br />

police brutality in America.<br />

14 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

PHOTOGRAPHING THE LONG ROAD TO JUSTICE<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 15

FROM TULSA TO MINNEAPOLIS: PHOTOGRAPHING THE LONG ROAD TO JUSTICE<br />

Several consistent themes arise across<br />

the thousands of images documenting<br />

the last year of racial justice<br />

protests in the United States— the<br />

raised Black power fist; a surge of<br />

civilian bodies facing off against<br />

a line of stony-faced police forces; eyes<br />

raised to the camera in triumphant challenge<br />

of the powers that be. Each of these<br />

poignant moments draw from long histories<br />

of photography on the American struggle<br />

for justice within a country whose deeply<br />

embedded racism spans centuries built of<br />

settler colonization and the enslavement of<br />

Black people.<br />

An especially horrific part of that long<br />

history of racial terror and subjugation in<br />

America is the 1921 Tulsa, Oklahoma massacre<br />

of Black residents by a white mob.<br />

While many Black Americans have long<br />

held the memory of that deadly night and<br />

the several preceding years of white mob<br />

violence that erupted across the nation,<br />

few photographs exist to bear ongoing<br />

witness to the death and destruction. In the<br />

decades since, however, Black Americans<br />

have utilized the camera’s evidentiary<br />

power as a tool in the twin struggles to<br />

humanize Black lives and depict racial<br />

injustice. The evisceration of Tulsa’s prosperous<br />

Black community and the 2020<br />

racial justice protests that represent the<br />

largest social justice movement in U.S.<br />

history are separated by nearly 100 years,<br />

serving as troubling markers of how little<br />

progress has been made on this long road<br />

to justice. Yet, the influx of visual storytelling<br />

by those whose lives are held in the<br />

balance and social media’s access to a<br />

rapt global audience offers new hope that<br />

justice might yet be realized.<br />

Since Black Lives Matter’s 2013 beginnings<br />

as a hashtag following the 2013<br />

shooting death of Black teenager Trayvon<br />

Martin, the movement gained steam as<br />

both a social media campaign and a<br />

series of national protests in the wake of<br />

each Black person killed by police brutality.<br />

It’s vital to understand how much this<br />

movement (and many other contemporary<br />

social justice efforts) owes to the wide<br />

circulation of visual evidence online. While<br />

such egregious acts of racial violence and<br />

police brutality have been rampant since<br />

the advent of American policing, it is the<br />

increasing presence of digital cameras that<br />

have ushered in an era where racism can<br />

be documented and therefore demand further<br />

reckoning. As BLM builds on the visual<br />

rhetoric of Civil Rights Movement photography,<br />

the relationship between street-level<br />

activism and the power of the camera is<br />

increasingly revealed.<br />

The collection of 23 photographs on<br />

these pages is drawn from over 500<br />

images submitted by photographers who<br />

answered the call to share their visual<br />

interpretations of the Long Road to Justice.<br />

Importantly, the work is primarily made<br />

by Black photographers whose lived<br />

experiences of racial injustice and respect<br />

for Black lives is tangibly felt across the<br />

photo essay. From Brian Branch-Prices’s<br />

intimate look at Black musicians to Kenechi<br />

Unachukwu’s We Still Here, a picture of<br />

Black resilience emerges. Donald Black<br />

Jr.’s loving ode to Black childhood symbolizes<br />

exactly what we fight for: a future<br />

where the threat of police brutality against<br />

our children, our mothers, our fathers and<br />

brothers is a thing of the past.<br />

The work to realize that future, however,<br />

is far from over. Even as these images of<br />

Black life compel the world to recognize<br />

the shared humanity of all people, there<br />

remains a stark disconnect between the<br />

realities visualized by our photography<br />

and the widespread realization of social,<br />

political, and economic reform. The<br />

struggle for racial justice continues and we<br />

lift our cameras as we steady our resolve,<br />

ready to meet the call wielding our choice<br />

of weapons.<br />

—Tara Pixley<br />

Program Credits<br />

Chair:<br />

Lisa DuBois<br />

Jurors:<br />

Laylah Amatullah Barrayn<br />

Lisa DuBois<br />

Anthony Barboza<br />

Eli Reed<br />

Jamel Shabazz<br />

16 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Best-of-Show Award<br />

Donald Black Jr.<br />

A Day No One Will Remember<br />

A collection of images created by Donald<br />

Black Jr. over the past 10 years. After returning<br />

home to Cleveland, Ohio, he started creating<br />

images that only an insider could see<br />

and began making images that represented<br />

his perception of his reality. Seeing himself<br />

and where he came from has influenced<br />

an obsession to photograph children in his<br />

community.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 17

FROM TULSA TO MINNEAPOLIS: PHOTOGRAPHING THE LONG ROAD TO JUSTICE<br />

Above<br />

Photographer: Titus Brooks Heagins<br />

Exhibit Title: Where the Sidewalk Ends<br />

This project represents a visual dialog<br />

that interrogates the lives of those who<br />

live in the margins of society.<br />

Caption: Brittany and Brianna<br />

Right top<br />

Photographer: Brian Branch-Price<br />

Exhibit Title: Rhythm and Praise, an<br />

Epic Journey<br />

This project reflects the expressions,<br />

thoughts and actions of a people, of a<br />

culture and of a folk who love to sing,<br />

dance, shout, give, teach, preach, cut a<br />

step all in the name of gospel music.<br />

Caption: Percy Bady, Newark, New<br />

Jersey<br />

Right below<br />

Photographer: Teanna Woods Okojie<br />

Exhibit Title: Black Boy Joy<br />

Black Boy Joy is a series of multiple<br />

images spanning from 2013 to <strong>2021</strong><br />

depicting young African youth and<br />

young men in various environments<br />

experiencing pure joy.<br />

18 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Above<br />

Photographer: Brian Branch-Price<br />

Exhibit Title: BLM: The Third<br />

Expressing the frustrations of an oppressed<br />

community reacting to social injustices, economic<br />

apartheid, Jim Crow, over-policing,<br />

lynching, inhumanity, during peaceful and<br />

confrontational protest in New York, New<br />

Jersey, Philadelphia, Richmond, and D.C.<br />

Caption: Livia Rose Johnson, 20, march<br />

organizer during a Justice for George Floyd<br />

protest and rally in New York on June 4, 2020<br />

Left<br />

Photographer: Raymond W. Holman, Jr.<br />

Exhibit Title: COVID-19 in Black America<br />

Environmental portraits of Black and brown<br />

skin people with first-hand experience of<br />

COVID-19 – having recovered, lost family<br />

members, been mentally challenged by<br />

social isolation, and figuring out how to<br />

adjust and make a new pathway.<br />

Caption: A Princeton University student<br />

experiencing a year of online classes and<br />

isolation due to COVID-19, but becoming a<br />

stronger human being through this challenge.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 19

Interview<br />

JOSEPH RODRIGUEZ<br />

Joseph Rodriguez is a New York-based photographer<br />

whose career spans over 25 years. His<br />

work has been published in National Geographic,<br />

The New York Times <strong>Magazine</strong>, Mother Jones,<br />

Newsweek, New York <strong>Magazine</strong> and others. He<br />

teaches at NYU and the International Center<br />

for Photography (ICP), among others, and has<br />

published several books including, more recently:<br />

Taxi: A Journey Through My Window 1977-1987<br />

and LAPD 1994. Below is an excerpt from our<br />

conversation, edited for clarity.<br />

By Caterina Clerici<br />

Caterina Clerici: Can you tell us about<br />

your background and how you got<br />

started in photography?<br />

and then dropped out and then got into<br />

the drug scene, started doing heroin,<br />

selling heroin, all that bad boy stuff. I<br />

went to Rikers Island. First time I went in, I<br />

was 17 years old. The second time I was<br />

20, and I was a much tougher guy than<br />

when I first went in. Rikers Island is not<br />

a place that I can even describe to you.<br />

How horrible that place is, that’s a whole<br />

other story.<br />

However, I came out at a very interesting<br />

time because I felt the need to change<br />

and those were the times of affirmative<br />

action, the only way for most young people<br />

to go to college without the ugly bank<br />

loans we have today. Through education<br />

I got myself together: got off methadone<br />

at 26, got my GED and studied graphic<br />

arts technology at the New York City<br />

Technical College in downtown Brooklyn.<br />

In 1980, I came out of school — first one<br />

to go to college in my family — and got<br />

a job in the printing business. You would<br />

send us your chromes, and we would<br />

make negatives, make plates and put<br />

them on a printing press. I learned a lot<br />

about color and printing and that helped<br />

my photography later on.<br />

I was making a lot of money in ‘80,<br />

‘81, doing all those big ads you see<br />

on the front pages of magazines, but I<br />

found myself going back down a rabbit<br />

hole, working 50, 60 hours a week. It<br />

was a great experience, but I was really<br />

unhappy. So I quit my job. My mother<br />

was very upset. I went back to driving<br />

a cab (taking photos that made up Taxi:<br />

Journey Through My Windows 1977-<br />

1987) and worked with a friend who had<br />

a truck and an art moving business.<br />

One day we delivered to a gallery in<br />

Soho where Larry Clark was laying his<br />

whole life’s work up on the wall. I went<br />

up to him as if he was Jimi Hendrix, like,<br />

“Oh, man! I really want to do what you<br />

do!” and he said: “Just go make pictures.”<br />

That’s all he said to me.<br />

I went to ICP and started assisting in<br />

the dark room, cleaning up the cibachrome<br />

lab. Then they gave me a scholarship<br />

and my life changed. I was schooled<br />

by some of the greatest Magnum photographers:<br />

Gilles Peress, Susan Meiselas,<br />

Eugene Richards, Alex Webb, Raymond<br />

Depardon, Sebastiao Salgado. The way<br />

I work is the way they work. For weeks,<br />

months and years. Anything personal is<br />

going to take me years. I’m just coming<br />

off following Mexican migrants throughout<br />

the USA for 10 years.<br />

I think about photography in time, and<br />

I always felt great work takes a lot of it.<br />

And, for me, it was always self-initiated.<br />

There were no editors, no one telling me<br />

Joseph Rodriguez: I was born and<br />

raised in Brooklyn in 1951. I grew up<br />

where I live right now, Park Slope, but it<br />

was South Brooklyn then. And you know,<br />

the Italian American history in New York<br />

was very strong. It was a very mafioso<br />

neighborhood and I’m not lying — we<br />

had the Gowanus Canal and it was not<br />

unusual for us to see floating bodies… It<br />

was pretty much like the old Sicilian way.<br />

In my Catholic school there were<br />

only about 400 or 500 of us. There was<br />

one Black kid and one Puerto Rican kid:<br />

me. The other kids were all mostly from<br />

Genoa, in Italy. Every single parent who<br />

lived close by used to grow grapes in<br />

the backyard and you would stop by to<br />

try their wine. It was very old school.<br />

But then the drugs came, and that’s what<br />

brought a lot of the same problems you<br />

have in so many other places.<br />

I lost my way… got into high school<br />

A young 18th Street Gang member being arrested. At the time this photo was taken the ATF (Arms Tobacco and<br />

Firearms) were working with LAPD to try and take down one of the most notorious gangs in Los Angeles. The aim<br />

was also to get as many guns off the streets as possible. Photo by Joseph Rodriguez from LAPD 1994.<br />

20 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

what to do. We just had that practice,<br />

that discipline, which also brings a lot<br />

of anxiety because you’re swimming<br />

upstream and you’re always alone. The<br />

practice is mapping out a story, which<br />

then turns into something longer — like<br />

when I went to LA in 1992 to photograph<br />

gangs and I’m still revisiting that project<br />

some 20 years later.<br />

CC: Can you tell us how your project<br />

on gang violence in LA started, how it<br />

evolved, and the challenges you faced?<br />

JR: When the Rodney King uprising<br />

happened, immediately I wanted to<br />

go, because I was missing America<br />

(Rodriguez was living in Europe at the<br />

time) and I understand the urban narrative,<br />

no matter which city it is — Chicago,<br />

Miami, New York, LA. I couldn’t do much<br />

research while I was living in Europe,<br />

because it wasn’t like now where everything’s<br />

online, but one thing I did was listen<br />

to music: all this gangsta rap, Eazy-E,<br />

Tupac, Dre, N.W.A., Public Enemy. The<br />

rhymes they were spitting out were the<br />

newspapers of the streets. So I was listening<br />

to guys like this Chicano rapper Kid<br />

Frost, who’s totally East LA, and I was like<br />

“Ok, I gotta go there.”<br />

I flew in the middle of the night from<br />

Stockholm to LA and arrived in my hotel<br />

room. I didn’t know where I was going,<br />

I had no connections and LA is huge!<br />

So I grabbed three newspapers, turned<br />

on the news and of course there was a<br />

funeral and a drive-by shooting every<br />

minute.<br />

There was a lot of ground to cover,<br />

so I stayed five weeks and worked<br />

really hard. No sleep, just worked and<br />

drove around, from one neighborhood<br />

to another, also with the cops doing the<br />

gang unit. But I knew our history already.<br />

I began interviewing African-American<br />

families in Watts, asking what was the<br />

difference with the riots in 1965, in the<br />

era when Malcolm X and Robert Kennedy<br />

were assassinated and there was a lot<br />

of city streets burning. The conversation<br />

began and it opened up doors, and I<br />

realized I wasn’t interested in just the<br />

guns or the people dying. This was a<br />

generational story that went back three or<br />

Waiting for a fare outside 220 West Houston Street, an after-after-hours club. New York 1984. Photo by Joseph<br />

Rodriguez from Taxi: A Journey Through My Window 1977-1987.<br />

four generations. That’s when I really felt<br />

the power of this story.<br />

I went back to Stockholm and we published<br />

what we could. I applied for an artist<br />

grant there, and then I moved to LA in<br />

September of ‘92. It was hard, I had left<br />

the kids behind and just kept flying back,<br />

trying not to be the absentee father that I<br />

was. But that was the path I was on.<br />

The gang project was very hard to<br />

do and I paid the psychological price<br />

for it, in terms of PTSD. At least eleven<br />

kids are dead, in the East Side Stories:<br />

Gang Life in East L.A. book. Children<br />

were dying and parents were telling me<br />

I needed to tell this story. Plus, sometimes<br />

people thought I was an undercover cop.<br />

I showed them my Spanish Harlem book<br />

and my National Geographic stories to<br />

prove that I wasn’t a cop, but paranoia<br />

runs deep in the hood. That hung over my<br />

head for a while — until the book was<br />

published — and I was going to quit the<br />

project, I felt I couldn’t handle it.<br />

I also had guys come say to me: “Yo,<br />

man, I’m about to go do a hit, you can<br />

come and just take pictures.” This is ethics.<br />

I said: “Look, I go with you, I photograph<br />

you doing this scene. Detectives<br />

come, they find out who’s who, they<br />

take my film and they use the evidence<br />

against you.” Some of the gang members<br />

were 16 years old; they didn’t know how<br />

the law worked. They didn’t understand<br />

what a camera could do. They were so<br />

enamored by their vanity and Hollywood<br />

influence. With a camera comes a lot of<br />

responsibility.<br />

CC: How did your surroundings while<br />

growing up influence your practice and<br />

your understanding of photography, as<br />

well as your mission as a “humanist”, as<br />

you often define yourself?<br />

JR: I grew up with my mother and her<br />

sisters, and there were no men in my family.<br />

My stepfather was a dope fiend who<br />

died on the streets. There were a lot of<br />

not nice things growing up, and that was<br />

very tough for me.<br />

One thing I remember is that my mom<br />

would sit with her sisters in a very old<br />

school, Italian way, they would have their<br />

coffee and talk about the men. I would<br />

hear these stories — it was unbelievable<br />

— of abuse and cheating, and those references<br />

helped me develop a feminine eye.<br />

I’m always asking myself: “Why did<br />

this photographer go photograph a gangster<br />

with guns, bullets and drugs, but then<br />

didn’t photograph a mother at the same<br />

time, or the struggling parent?” That’s<br />

always been very important in my work. I<br />

didn’t always go for the guns.<br />

“Raised in violence, I enacted my own<br />

violence upon the world and upon myself.<br />

What saved me was the camera, its ability<br />

to gaze upon, to focus, to investigate,<br />

to reclaim, to resist, to re-envision.” That<br />

quote is from my journal. That’s how I<br />

got here, that’s where this goal comes<br />

from. That’s why I went back for East Side<br />

Stories (Rodriguez’s long-term project<br />

about gang violence in LA, shot between<br />

1992–2017.)<br />

Continued on page 70.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 21

But before delving into how documentary<br />

photography is evolving, it is essential<br />

to first address the fight to change<br />

the internal practices and structure of the<br />

photo industry itself.<br />

One of the biggest problems in<br />

photography is the widespread percep-<br />

Years ago,<br />

tion among audiences that photographs<br />

during an artist talk at a journalism<br />

conference, I stated that I the extent to which a photographer’s<br />

don’t lie. Most people don’t understand<br />

don’t believe documentary photographs<br />

create social change. A consume. This knee-jerk assumption of<br />

personal biases impact the images we<br />

colleague stood up and interrupted my objectivity allows audiences to accept<br />

talk to disagree with me. Our impromptu an image as truth: forming hard-andfast<br />

opinions about events and cultures.<br />

debate--across an audience of photographers<br />

and journalism students--exemplifies Without critical assessment from the viewers,<br />

the photographer has tremendous<br />

an important dialog within our industry<br />

that is pushing the boundaries of how power over the value viewers assign to<br />

photography is created and used. Our the lives of the individuals pictured. Such<br />

power and representation have plagued<br />

the industry since the advent of photography<br />

as a medium. Recent momentum<br />

in acknowledging and changing these<br />

practices prompted the formation of<br />

collectives such as Women Photograph,<br />

MFON, Diversify Photo, Ingenious<br />

Photograph, and the Authority Collective,<br />

to name a few. Meaningful reflection<br />

about representation, connection, and<br />

accountability are imperative starting<br />

points for anyone assigning, publishing,<br />

Photography &<br />

By Emily Schiffer<br />

disagreement hinged on different definitions<br />

of what “social change” looks like<br />

and means. I was asserting that images<br />

create awareness--which unreliably<br />

evokes empathy, shifts mindsets, and<br />

inspires action. He was arguing that<br />

empathy is change. We were both right.<br />

Differentiating between raising awareness,<br />

fostering empathy, inspiring action,<br />

and changing conditions enables photographers<br />

to precisely define their goals<br />

and approaches for individual projects.<br />

A whole world opens up when<br />

we think of images as the start<br />

of a creative process—rather<br />

than the end goal.<br />

unchallenged authority creates a dangerous<br />

paradigm. Historically, photographers<br />

have been overwhelmingly white<br />

and male, which means they produced<br />

images of cultures, communities, and<br />

people that were not familiar to them.<br />

On top of that, editors, curators, critics,<br />

and other industry gatekeepers have<br />

also historically been white and male,<br />

which further normalizes the white male<br />

gaze within the industry writ large, and<br />

silencing other perspectives. This set-up<br />

causes glaring omissions in documentary<br />

narratives. Practically speaking,<br />

omissions amount to erasure, which is a<br />

quintessential tactic of colonialism and<br />

oppression. Despite important changes<br />

in who is able to access the profession,<br />

and in how we think about photography,<br />

statistics show that the demographics of<br />

the industry remain largely unchanged.<br />

In 2020, 80% of A1 images in leading<br />

U.S. and European newspapers were<br />

created by male photographers. Issues of<br />

exhibiting, or creating photographs, let<br />

alone those attempting to create social<br />

change through photography.<br />

Sometimes, viewers need to physically<br />

see the errors in the dominant narrative<br />

in order to shift their mindset. Artists such<br />

as Alexandra Bell, Wendy Red Star,<br />

and Tonika Lewis Johnson visualize the<br />

crisis of biased representation, enabling<br />

viewers to reflect on their perceptions<br />

of self and others. Bell redacts racist<br />

language in New York Times articles and<br />

sometimes changes the imagery to reflect<br />

a more accurate depiction of the facts.<br />

She then wheatpastes the before and<br />

after versions of the articles onto outdoor<br />

public walls: simultaneously holding the<br />

media accountable, and forcing viewers<br />

to confront their complacency when<br />

consuming media. Similarly, Red Star<br />

annotates photographs of Crow chiefs,<br />

originally taken by Charles Milton Bell in<br />

1880. Red Star uses red ink to provide<br />

historical and contextual information,<br />

22 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Photo by Dawnee LeBeau. From Women of the<br />

Tetonwan, a portrait project celebrating the matriarchs<br />

of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe in South Dakota. <br />

Winona Kasto is one of our Lakota Lolihan' (cooks).<br />

It's a great honor to be able to offer food as nourishment<br />

and healing, especially at ceremonies and<br />

community events.<br />

with individuals directly impacted by the<br />

issues their work addresses. Still, for others<br />

who photograph solo, like Dawnee<br />

LeBeau, an ongoing and deep community<br />

dialog dictates what is created and<br />

shared. It is worth noting that all of the<br />

aforementioned photographers identify<br />

as part of the communities they document.<br />

Even people depicting their own<br />

cultures need accountability, and ceding<br />

power enriches photographic work.<br />

Listening, critical discourse, and reflection<br />

Social Change<br />

on one’s own biases are even more vital<br />

for outsiders.<br />

thereby informing the viewer and commenting<br />

on non-Indigenous people’s lack<br />

of knowledge about Indigenous culture<br />

and history. Aware of how profoundly the<br />

media impacts our sense of self, Johnson<br />

created Englewood Rising, a communityled<br />

billboard campaign created and<br />

paid for with funds raised by Englewood<br />

residents and activists to, “showcase<br />

Englewood’s everyday beauty and<br />

counter its damage-centered narrative.”<br />

Created by the community, for the community,<br />

and in the community, this wildly<br />

popular project demonstrates how well<br />

someone from the community can portray<br />

other members within it.<br />

Discussions about representation<br />

and whether or not a solo perspective is<br />

always desirable have prompted photographers<br />

to share authorship and power<br />

in the image-making process. More<br />

horizontal approaches sometimes take<br />

the form of a collective voice, composed<br />

of many professional photographers, as<br />

is the case with Kamoinge (founded in<br />

1963), a collective working to “HONOR,<br />

document and preserve the history and<br />

culture of the African Diaspora with<br />

integrity and insight for humanity through<br />

the lens of Black photographers.” Other<br />

artists, like Brenda Anne Kenneally, facilitate<br />

decade-long photography workshops<br />

With the politics of representation<br />

fresh on our minds, and<br />

the raising of awareness as a<br />

baseline, we will look at examples<br />

of photographers leading<br />

our industry in a more responsible,<br />

and impactful direction.<br />

Whether making images collaboratively,<br />

using them to create conversations,<br />

creatively installing them in communities,<br />

or amplifying existing grassroots<br />

organizing, these projects engender<br />

active engagement from both the people<br />

impacted by these issues and the viewers<br />

seeing these projects--even when there is<br />

not an easy or clear solution.<br />

More →<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 23

Photography & Social Change<br />

Projects<br />

That Inspire<br />

Introspection<br />

and<br />

Challenge<br />

Oppressive<br />

Narratives<br />

Ariana Faye Allensworth<br />

Staying Power<br />

Ariana Faye Allensworth’s<br />

background in social work,<br />

urban studies, African<br />

American studies,<br />

and education enables her to<br />

deconstruct power imbalances<br />

in the photo industry.<br />

Her latest project Staying<br />

Power, implements her critique<br />

of how photography is<br />

taught, and how narratives are<br />

constructed and consumed.<br />

Staying Power is “a collaborative,<br />

multidisciplinary art and research project<br />

celebrating the people’s history of New<br />

York City public housing. The project<br />

offers counter-narratives to the stereotypes<br />

surrounding the New York City<br />

Housing Authority (NYCHA) through<br />

the lens of residents raised and living in<br />

NYCHA.”<br />

The project emerged out of<br />

Allensworth’s collaborative work at the<br />

Anti-Eviction Mapping Project (AEMP):<br />

visualizing injustice by mapping open<br />

data, collecting oral histories, producing<br />

storytelling projects in collaboration<br />

with tenants, facilitating mutual aid, and<br />

researching real estate speculation and<br />

corporate landlordism.<br />

At AEMP, Allensworth worked closely<br />

with residents displaced by the demolition<br />

and downsizing of public housing.<br />

New York City, home to the largest public<br />

housing stock in the United States, is<br />

privatizing and defunding many public<br />

housing programs, a radical shift in<br />

how these programs are managed and<br />

operated. “It’s an important moment to<br />

document public housing reform, and<br />

to create room for people’s narratives,”<br />

explains Allensworth. The dominant<br />

‘failed public housing’ narrative stood<br />

in stark contrast to the breadth of lived<br />

experiences residents described.<br />

Housed online, Staying Power is a<br />

platform for publishing, discussing, and<br />

presenting the NYCHA community’s<br />

histories. The content is also available<br />

through an open-ended series of booklets<br />

and postcards, distributed to subscribers<br />

through the postal service.<br />

The project explores how this community<br />

creates, cares for, and<br />

builds their own archives.<br />

“Memory is a valuable historical<br />

resource,” explains<br />

Allensworth. “Staying<br />

Power explores how<br />

photography, ephemeral<br />

and personal collections<br />

of objects, and interviews<br />

with residents can offer<br />

alternative modes of knowledge<br />

that retell the public housing story. The<br />

project positions residents as archivists<br />

and storytellers.” Allensworth’s goal is to<br />

refute stereotypes that eclipse people’s<br />

lived experiences, and assert that all residents<br />

are worthy of inclusion in NYCHA<br />

history.<br />

To gather material, Allensworth<br />

facilitated photography workshops,<br />

conducted long-form oral histories, and<br />

photographed ephemera. Teaching<br />

photography as a way of collaboratively<br />

building narratives poses a challenge: on<br />

the one hand, taking someone’s creativity<br />

seriously by helping them develop<br />

their craft is the ultimate form of respect.<br />

On the other hand, traditional photoeducation<br />

practices—which literally teach<br />

how to see—undermine the message that<br />

Image by Ariana Faye Allensworth. A poster created<br />

for Staying Power featuring an image of Michael Casiano,<br />

a resident of LaGuardia Houses on the Lower<br />

East Side of Manhattan.<br />

everyone’s perspective and story is valid.<br />

Allensworth didn’t want her aesthetic<br />

preferences to influence the work residents<br />

created. She structured her workshops<br />

using the “Photo Voice” model,<br />

inviting participants to create visual<br />

answers to questions about their public<br />

housing experience. Instead of focusing<br />

on aesthetics, the group discussed the<br />

messages the images delivered, and critiqued<br />

the artists’ visual communication.<br />

Similarly, Allensworth’s method of<br />

collecting oral histories positioned the<br />

narrator to author their own story: “I<br />

don’t show up with a predetermined set<br />

of questions, so they’re not reduced to<br />

whatever container I create for them.<br />

They decide what it is that they want to<br />

put on record.”<br />

Though created primarily for NYCHA<br />

residents, Staying Power is also an important<br />

resource for educators, activists, and<br />

policy makers looking to counter erasure,<br />

claim space, and amplify residents’<br />

experiences without filtering them through<br />

a third party lens.<br />

24 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Subscribe to <strong>ZEKE</strong> and receive the full<br />

84-page version in print and digital<br />

$25.00* for two issues/year<br />

Includes print and digital<br />

*Additional costs for shipping outside the US.<br />

Subscribe to <strong>ZEKE</strong> magazine and get the best of<br />

global documentary photography delivered to your<br />

door, and to your digital device, twice a year. Each<br />

issue presents outstanding photography from the<br />

Social Documentary Network on topics as diverse<br />

as the war in Syria, the European migration crisis,<br />

Black Lives Matter, the Bangladesh garment industry,<br />

and other issues of global concern.<br />

But <strong>ZEKE</strong> is more than a photography magazine.<br />

We collaborate with journalists who explore<br />

these issues in depth —not only because it is important<br />

to see the details, but also to know the political<br />

and cultural background of global issues that require<br />

our attention and action.<br />

Click here to find out how »<br />

www.zekemagazine.com/subscribe<br />

Contents of <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2021</strong> Issue<br />

Awake in the Desert Land<br />

Photographs by Sofia Aldinio<br />

Path Away<br />

Photographs by Nicolò Filippo Rosso<br />

From Tulsa to Minneapolis: Photographing the<br />

Long Road to Justice<br />

Photographs by 27 Black photographers documenting this<br />

extraordinary time in American history<br />

The Emptying of the Andes<br />

Photographs by Emiliano Pinnizzotto<br />

Migration from the Northern Triangle<br />

by Daniela Cohen<br />

Interview with Joseph Rodriguez<br />

by Caterina Clerici<br />

Photography & Social Change<br />

by Emily Schiffer<br />

Book Reviews<br />

Edited by Michelle Bogre<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 25

26 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

‘Tia’ (aunt) Sibilla in her hut<br />

in the village of St Martin de<br />

Porres, 15,000 feet above the<br />

sea level, in Peru.<br />

The Emptying of the Andes<br />

By Emiliano Pinnizzotto<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 27

There is a very quiet and subtle<br />

migration taking place in Peru. It is a<br />

phenomenon of “rural-urban migration”<br />

that has continued incessantly<br />

for years, and is emptying the Andes<br />

of people who are leaving their<br />

lands under the illusion of a better future in<br />

the big cities—Lima, Arequipa, Chimbote.<br />

Many young people have escaped from<br />

peasant life, only to end up in the favelas<br />

of these cities, with no light, no gas,<br />

nor running water. This migratory movement,<br />

which is emptying the Andes of a<br />

population that will end up in the slums, is<br />

referred to as “invasions,” because of the<br />

unstoppable number of arrivals.<br />

This photographic project by Italian<br />

photographer Emiliano Pinnizzotto follows<br />

the stories both of those who remain in<br />

their ancestral homes in the mountains, and<br />

those who left for the big city and found<br />

themselves passing from an imagined<br />

dream into a real nightmare. The Emptying<br />

of the Andes in an attempt to give voice<br />

to a little-known story that in the next few<br />

years will empty the mountains of native<br />

people and culture and fill the cities with<br />

those seeking a better life but often find<br />

disappointment instead.<br />

28 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Photo by Emiliano Pinnizzotto<br />

Two women come back home with<br />

their sheep after a day of pasture.<br />

Grazing sheep is one of the main<br />

activities in the mountains. Sheep<br />

are raised principally for milk and<br />

wool and for their meat.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 29

BOOK<br />

REVIEWS<br />

EDITOR: MICHELLE BOGRE<br />

I CAN MAKE YOU FEEL<br />

GOOD<br />

By Tyler Mitchell<br />

Prestel, 2020<br />

208 pages | $60<br />

I<br />

Can Make You Feel Good, Tyler<br />

Mitchell’s second monograph,<br />

evidences and envisions contemporary<br />

Black joy. His work, which reframes<br />

Blackness through portraits that challenge<br />

prevailing racial stereotypes,<br />

investigates the question: What does the<br />

pursuit of happiness look like for Black<br />

Americans?<br />

Mitchell chronicles unguarded<br />

moments of tenderness, tranquility, and<br />

bliss among individual and intimate<br />

clusters of young Black adults. Dramatic<br />

silhouettes of sumptuously textured clothing<br />

are interspersed with soft-focused<br />

sensual gestures of gentle affection.<br />

With his cinematic eye and deft use of<br />

scale, composition, and perspective, he<br />

animates a fluid compilation of full bleed,<br />

mostly double-page spreads.<br />

Mitchell, who was included in the<br />

Aperture publication and exhibition, The<br />

New Black Vanguard, pushes the conventions<br />

of race, beauty, gender and power.<br />

Aware of, and indebted to, predecessors<br />

including Roy DeCarava, Gordon<br />

Parks, Jamel Shabazz and 19th century<br />

scholar, abolitionist and orator, Frederick<br />

Douglass, he and his contemporaries<br />

embrace the role of the Black body and<br />

Black lives as subject matter. They expand<br />

the visual culture conversation by documenting<br />

and challenging their realities of<br />

presence, absence, invisibility, appropriation,<br />

desire, and objectification.<br />

Mitchell’s images are subversive in<br />

their disruption of what writer Junot Diaz<br />

coins as the ‘default whiteness’ of our<br />

American society. They are transgressive<br />

in their assertion of a reality beyond<br />

conventional representation. The wraparound<br />

cover image is an apt example of<br />

Mitchell’s intentional tableaux: It shows<br />

five young shirtless men, three of which<br />

face away from the camera with heads<br />

bent, another is partially seen, his face<br />

in profile, gazing somewhat pensively<br />

across a flowering meadow to the edge<br />

of a tree-lined woods. The fifth person,<br />

and the only one facing the camera, has<br />

his face in shadow as he seemingly tightens<br />

the black belt at his waist. A thick,<br />

intertwined chain of silver metal catches<br />

the available light and grabs the attention<br />

of the viewer. A white string of cotton is<br />

tied as a single, loose bracelet on the<br />

wrist of his active hand. The choice of<br />

adornment and fashion accessory could<br />

be codifiers of modes of bondage and<br />

tools of slavery, and intersect with the<br />

understated but obvious designer labels<br />

of Valentino jeans (which retail for close<br />

to $1000) and Ben Sherman underwear<br />

(a fashion brand noted for attracting<br />

youth culture).<br />

Images of leisurely<br />

picnics are sequenced with<br />

people at play, frolicking<br />

and actively engaging with<br />

hula hoops, skateboards,<br />

jump ropes, and a kite.<br />

Mitchell acknowledges his<br />

reference to Tamir Rice, the<br />

12-year-old Black boy shot<br />

in a Cleveland park in 2014<br />

while carrying a toy gun.<br />

Mitchell also reframes the<br />

connotation of the hoodie,<br />

following its presence in<br />

the 2012 killing of 17-yearold<br />

Trayvon Martin. Two<br />

images purportedly use the<br />

same man wearing a plush<br />

cotton, powder-blue hooded<br />

sweatshirt while lying on<br />

a wooden floor. The first<br />

features him face down<br />

framed in a horizontal position with his<br />

open-palmed hands interlaced behind his<br />

back. In the second, he is face-up, with<br />

his head, shoulders and arms filling the<br />

bottom of the frame, his hands tentatively<br />

holding the soft hood, a wide-eyed listful<br />

expression, looking just above the gaze<br />

of the viewer. Both images imply the<br />

notion of an arrest and a mug shot.<br />

A final example of Mitchell’s purposeful<br />

challenge to codified visual language<br />

is a vertical image of a man standing<br />

in front of a peeling red-painted cement<br />

wall. He wears flowing white pants<br />

spilling over sleek brown leather loafers.<br />

A green fabric sac, is held in hand, a billowing<br />

bright yellow piece of silk is hung<br />

with clothespins from black electrical<br />

cording suspended above, obscuring his<br />

head and torso.<br />

This bold abstraction of Pan African<br />

colors is perhaps a nod to poet, playwright,<br />

and activist, Amiri Baraka, who<br />

saw Black beauty as an act of justice.<br />

His poem, Why Is We Americans?<br />

proclaims, “What is the use of being<br />

ethereal and being escapist and romantic?<br />

Take the words and make them into<br />

bullets. Take the words and make them<br />

do something.” Tyler Mitchell’s images<br />

create visual text to explode imagination<br />

and claim sovereignty.<br />

—J. Sybylla Smith<br />

©Tyler Mitchell.<br />

30 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

OUR TOWN<br />

by Michael von Graffenried<br />

Steidl, <strong>2021</strong><br />

121 pages | $50<br />

“<br />

The only way to achieve realistic<br />

pictures is to steal them,” says<br />

Swiss photographer Michael<br />

von Graffenried (MvG as he calls<br />

himself), whose most recent book, Our<br />

Town, illustrates both the art of the steal<br />

and MvG’s chosen path bringing people<br />

together, or not. In Our Town, MvG catalogs<br />

the divisions of racism in a small<br />

town in America by photographing who<br />

he observes—whites with whites and<br />

Blacks with Blacks. There are common<br />

moments that chronicle people together:<br />

high school events, sports, political gatherings,<br />

a wedding, a barbershop and<br />

a strip bar. In the latter photograph, a<br />

white male in erotic contact with a Black<br />

dancer sadly illustrates the disparity that<br />

is less blatantly represented throughout<br />

Our Town.<br />

MvG prefers using an old rotating lens<br />

35mm Widelux film camera which has a<br />

140 degree wide angle view because,<br />

he says, he can hold the camera next to<br />

his chest, and take photos without looking<br />

through the viewfinder. “Today, photography<br />

is no longer real...People know you<br />

are coming and are putting on a show.<br />

They are never themselves. That’s why<br />

I use this camera. You can take photos<br />

without looking through the viewfinder<br />

and nobody notices when you are actually<br />

pressing the shutter button. It’s the<br />

only way to achieve realistic pictures,” he<br />

said in a 2010 interview with Hans Ulrich<br />

Obrist, held in the Serpentine Gallery,<br />

Kensington Court, London.<br />

Holding a large Widelux camera at<br />

chest level does not make a photographer<br />

invisible. It does increase MvG’s opportunity<br />

to steal a picture by circumventing the<br />

scene-altering effect of asking permission<br />

to make a picture. MvG’s mandate to<br />

bring people together seems to be related<br />

to his camera’s ability to register everything<br />

within its field of view. With the use<br />

of this slow-tech camera technique, he<br />

slices a story from his chosen environment<br />

with an impressive mastery.<br />

In 2006, MvG began his Our Town<br />

project for the 300th anniversary of the<br />

founding of New Bern, North Carolina.<br />

The town was founded in 1710 by<br />

MvG’s own Swiss ancestor Christoph<br />

von Graffenried, who had traveled to<br />

the Americas in 1710 and established<br />

what became the sister city to Bern,<br />

Switzerland.<br />

After MvG’s first exhibition, New<br />

Bern’s local newspaper, the Sun<br />

Journal, ran the front page headline,<br />

“Swiss Photos of City Nixed.” The<br />

article by Sue Book reported “Many<br />

of those on the 300th Anniversary<br />

Celebration Committee and the Swiss<br />

Bear Development Corporation board<br />

thought Michael von Graffenried’s images<br />

showed New Bern in an unflattering,<br />

even racist, light.” The newspaper also<br />

reported that neither sponsoring agency<br />

would help to publish the photographs.<br />

That response did not deter MvG from<br />

spending multiple years on his project.<br />

He returned to New Bern after the killing<br />

of George Floyd to photograph the<br />

underserved Black community. In the<br />

book, he combines his original pictures<br />

with his more recent work. He described<br />

his creative process to Swiss Television in<br />

2007, “. . . First, I want to understand if<br />

I’ve understood something. I try to put it<br />

in a frame that explains daily life. I try to<br />

condense a story within one picture. I am<br />

convinced a picture tells more about the<br />

person who is looking at it than about the<br />

one who took it.”<br />

But the most successful pictures are not<br />

about the photographer or the viewer.<br />

Great pictures are about what is inside<br />

the picture frame. MvG admits that he is<br />

not a creator of iconic images. For him,<br />

each photograph must be the story. There<br />

are no photo captions or text, other than<br />

his 124 word introduction. He intends his<br />

panoramic views to chronicle both the<br />

subject and the background details of a<br />

complex reality. The reader is invited to<br />

take cues from the book’s 120 images.<br />

Many of his amazing compositions reveal<br />

uncomfortable situations that are daily life<br />

in New Bern. MvG is a late witness to the<br />

plague of racism in America. There is the<br />

hope that this testament will contribute to<br />

the end of the racism common throughout<br />

the United States.<br />

—Frank Ward<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 31

Contributors<br />

Sofia Aldinio is an Argentine-American<br />

documentary photographer and storyteller<br />

based between Joshua Tree, California and<br />

Baja California, Mexico. As an immigrant<br />

and Latina, Sofia’s work is guided by themes<br />

like climate change, preserving natural and<br />

cultural heritage, and immigration, amplifying<br />

the stories of immigrants and refugees in the<br />

Northeast of the United States.<br />

Barbara Ayotte is the editor of <strong>ZEKE</strong> magazine<br />

and the Communications Director of the<br />

Social Documentary Network. She has served<br />

as a senior strategic communications strategist,<br />

writer and activist for leading global health,<br />

human rights and media nonprofit organizations,<br />

including the Nobel Peace Prize- winning<br />

Physicians for Human Rights and International<br />

Campaign to Ban Landmines.<br />

Kirsten Rebekah Bethmann, aka Kirsten<br />

Lewis, is a Colorado-based international<br />

photographer, educator and public speaker.<br />

She has traveled to over 40 countries to work<br />

with organizations and individuals creating<br />

documentary-based pictures to aid in fundraising,<br />

advertising, awareness and personal family<br />

archive builds, and is the primary force in<br />

the genre of documentary family photography.<br />

Donald Black Jr. is a Cleveland artist who<br />

works with video, installation, and photography.<br />

He is an alumnus of Cleveland School of<br />

the Arts and attended Ohio University, where<br />

he studied commercial photography. Black<br />

received first place in SDN's From Tulsa to<br />

Minneapolis Call for Entries and third place in<br />

Nikon's international photo competition. His<br />

work explores family relationships, racism,<br />

environment, and identity.<br />

Beginning as a freelancer for the Washington<br />

Post, Brian Branch-Price became an intern<br />

and staffer at various publications. As a content<br />

provider, Brian contracts with Zuma Press<br />

and also focuses on portraiture, reportage<br />

and fine art photography. He had several art<br />

exhibits at the Plainfield Public Library on his<br />

legendary Black gospel artists and veterans.<br />

Sheila Pree Bright is an acclaimed international<br />

photographic artist who portrays<br />

large-scale works that combine a wide-ranging<br />

knowledge of contemporary culture. Known<br />

for her series, #1960Now, Young Americans,<br />

Plastic Bodies, and Suburbia, Bright has<br />

received several nominations and awards.<br />

Her work is included in numerous private and<br />

public collections.<br />

Born in Harlem, New York, Sean Josahi<br />

Brown draws inspiration from the common<br />

human experience to capture raw emotion and<br />

share compelling stories that raise awareness<br />

of social issues.<br />

32 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong><br />

Caterina Clerici is an Italian journalist and<br />

producer based in New York. She graduated<br />

from Columbia University’s Journalism School<br />

and is a grantee of the European Journalism<br />

Centre for her work in Haiti, Ghana and<br />

Rwanda. She worked as a photo editor and<br />

VR producer at TIME, and as an executive<br />

producer at Blink.la.<br />

Daniela Cohen is a non-fiction writer of South<br />

African origin currently based in Vancouver,<br />

Canada. Her work has been published in New<br />

Canadian Media, Canadian Immigrant, The<br />

Source Newspaper, and is upcoming in Living<br />

Hyphen. Daniela’s work focuses on themes of<br />

displacement and belonging, justice, equity,<br />

diversity and inclusion.<br />

Lisa DuBois is an ethnographic photojournalist<br />

and curator with insatiable curiosity, who<br />

raises public cultural awareness through work<br />

focusing on subcultures within mainstream<br />

society. She has exhibited her work internationally<br />

and domestically, contributed to major<br />

news publications and stock agencies, and<br />

had her work for X Gallery recognized by the<br />

Guardian and New York Times.<br />

A Brooklyn-born photographer of a Jamaican<br />

mother and Saint Lucian father, Imari<br />

DuSauzay’s images range from portraits of<br />

people on the street to those of interesting and<br />

notable people. With a Masters degree in<br />

Media Arts from Long Island University, Imari<br />

has worked as an art educator and taught in<br />

programs for children in urban communities.<br />

Iyana Esters combines art with her expertise<br />

in public health, using photography as a lens<br />

to document the human impact of environmental<br />

racism, practices, rituals, and sexualities<br />

related to Black life. An emerging photographer,<br />

Iyana works primarily in long-form<br />

photography and documentary.<br />

Marissa Fiorucci is a freelance photographer<br />

in Boston, MA. She is former studio<br />

manager for photographer Mark Ostow and<br />

worked on projects including portraits of the<br />

Obama Cabinet for Politico. She specializes<br />

in corporate portraits and events, but remains<br />

passionate about documentary.<br />

Prof. Collette Fournier has been photographing<br />

for forty years. She is a member of<br />

Kamoinge, an African-American photography<br />

collective. As an award winning photographer,<br />

her specialties are portraiture, documentary<br />

and nature photography. Fournier is<br />

writing a personal narrative on her journey<br />

into photography and lectures on her production<br />

"Retrospective: Spirit of A People."<br />

After taking a college course in photography,<br />

Jonathan French began to teach himself.<br />

While living in Washington, D.C., he captured<br />

many historic events. Afterwards, he did international<br />

travel and events, as well as many<br />

live concerts. He has taught and has exhibited<br />

nationally and internationally. He currently<br />

lives in Panama.<br />

Cheryle Galloway is a Zimbabwean-born<br />

photographer based in Maryland. Pre-Covid,<br />

Cheryle’s work focused on nature, street and<br />

portraiture. Since February 2020, she has<br />

focused primarily on telling more personal stories,<br />

exploring issues of identity, gender and<br />

race. Her project “Out of Many?” asks the<br />

question, how does America heal to become<br />

one nation?<br />

Terrell Halsey is an artist based in<br />

Philadelphia, PA. He seeks to create visual<br />

poems of humanity while diving further into<br />

his understanding of the world. After receiving<br />

his Temple University BFA, he has exhibited<br />

nationally and also been featured in publications.<br />

His current project focuses on the<br />

contemporary Black experience.<br />

Titus Brooks Heagins is a documentary photographer<br />

and educator adept at capturing the<br />

full emotional and cultural spectrum of diverse<br />

communities. Based in Durham, NC, he has traveled<br />

extensively to produce a diverse body of<br />

work exhibited in many private and public collections,<br />

and taught photography and art history<br />

courses at numerous colleges and universities.<br />