ZEKE Magazine: Fall 2021

Fall 2021 Issue ZEKE Award Winners Awake in the Desert Land by Sofia Aldinio This ongoing project documents how climate change is uprooting small, inland and coastal communities in Baja California, Mexico that depend directly on natural resources to survive and thereby threatening cultural heritage. Path Away by Nicoló Filippo Rosso Two months after Hurricanes Eta and Iota hit Central America, 11 thousand people gathered in San Pedro Sula, starting the first migrants' caravan of the year directed to the U.S. The migrants’ crossing through gang-controlled areas, deserts, and jungles was made even harder by the pandemic. Other Featured Content Article by Daniela Cohen exploring migration from Central America, the factors driving hundreds of thousands of people to leave their homeland seeking a new life in North America, and the traumas along the way. From Tulsa to Minneapolis: Photographing the Long Road to Justice Photographs by 27 Black photographers documenting this extraordinary time in American history. Text by Tara Pixley Photography That Makes a Difference by Emily Schiffer The Emptying of the Andes Photographs by Emiliano Pinnizzotto Interview with Joseph Rodriguez by Caterina Clerici Book Reviews edited by Michelle Bogre

Fall 2021 Issue

ZEKE Award Winners

Awake in the Desert Land by Sofia Aldinio

This ongoing project documents how climate change is uprooting small, inland and coastal communities in Baja California, Mexico that depend directly on natural resources to survive and thereby threatening cultural heritage.

Path Away by Nicoló Filippo Rosso

Two months after Hurricanes Eta and Iota hit Central America, 11 thousand people gathered in San Pedro Sula, starting the first migrants' caravan of the year directed to the U.S. The migrants’ crossing through gang-controlled areas, deserts, and jungles was made even harder by the pandemic.

Other Featured Content

Article by Daniela Cohen exploring migration from Central America, the factors driving hundreds of thousands of people to leave their homeland seeking a new life in North America, and the traumas along the way.

From Tulsa to Minneapolis: Photographing the Long Road to Justice Photographs by 27 Black photographers documenting this extraordinary time in American history. Text by Tara Pixley

Photography That Makes a Difference by Emily Schiffer

The Emptying of the Andes Photographs by Emiliano Pinnizzotto

Interview with Joseph Rodriguez by Caterina Clerici

Book Reviews edited by Michelle Bogre

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

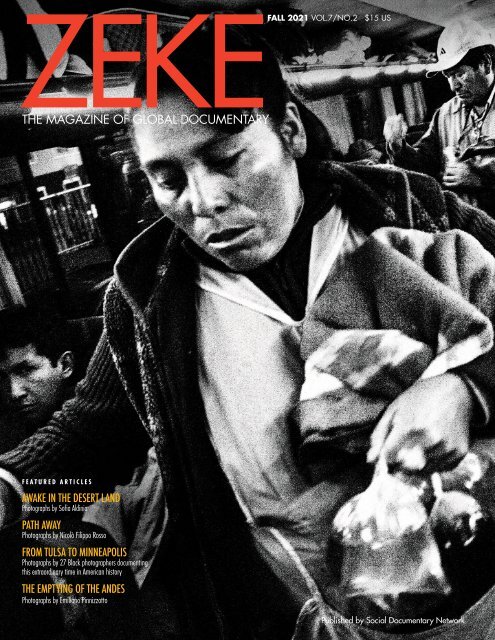

<strong>ZEKE</strong>FALL <strong>2021</strong> VOL.7/NO.2 $15 US<br />

THE MAGAZINE OF GLOBAL DOCUMENTARY<br />

FEATURED ARTICLES<br />

AWAKE IN THE DESERT LAND<br />

Photographs by Sofia Aldinio<br />

PATH AWAY<br />

Photographs by Nicolò Filippo Rosso<br />

FROM TULSA TO MINNEAPOLIS<br />

Photographs by 27 Black photographers documenting<br />

this extraordinary time in American history<br />

THE EMPTYING OF THE ANDES<br />

Photographs by Emiliano Pinnizzotto<br />

Published by Social Documentary <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL Network <strong>2021</strong>/ 1

FALL <strong>2021</strong> VOL.7/NO.2<br />

$15 US<br />

2 | AWAKE IN THE DESERT LAND<br />

Photographs by Sofia Aldinio<br />

CO-WINNER OF <strong>2021</strong> <strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD FOR DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY<br />

Sofia Aldinio from Awake in the Desert Land<br />

Nicolò Filippo Rosso from Path Away<br />

Joshua Rashaad McFadden from From Tulsa to<br />

Minneapolis: Photographing the Long Road to<br />

Justice<br />

Emiliano Pinnizzotto from The Emptying of the<br />

Andes<br />

14 | PATH AWAY<br />

Photographs by Nicolò Filippo Rosso<br />

CO-WINNER OF <strong>2021</strong> <strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD FOR DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY<br />

40 | FROM TULSA TO MINNEAPOLIS:<br />

PHOTOGRAPHING THE LONG ROAD TO JUSTICE<br />

Photographs by 27 Black photographers documenting this<br />

extraordinary time in American history<br />

60 | THE EMPTYING OF THE ANDES<br />

Photographs by Emiliano Pinnizzotto<br />

26 |<br />

30 |<br />

52 |<br />

54 |<br />

70 |<br />

Migration from the Northern Triangle<br />

The Last Resort to Stay Alive<br />

by Daniela Cohen<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> Award Honorable Mention Winners<br />

Interview with Joseph Rodriguez<br />

by Caterina Clerici<br />

Photography & Social Change<br />

by Emily Schiffer<br />

Book Reviews<br />

Edited by Michelle Bogre<br />

78 | Contributors<br />

Deborah Espinosa from Photography & Social<br />

Change<br />

On the Cover<br />

Photo by Emiliano Pinnizzotto from The Emptying<br />

of the Andes. Inside a bus heading in the direction<br />

of Lima. Many of the people inside the bus are<br />

leaving their homes forever, looking for a job and<br />

a better life in the cities. See inside back cover for<br />

a profile of Emiliano Pinnizzotto.

<strong>ZEKE</strong><br />

THE<br />

MAGAZINE OF<br />

GLOBAL DOCUMENTARY<br />

Published by Social Documentary Network<br />

Dear <strong>ZEKE</strong> Readers:<br />

As I write this letter, Hurricane Ida has just completed its deadly flooding and destruction in Louisiana and the<br />

Northeast exactly 16 years after Katrina devastated the Gulf Coast. Floods have killed 20 people in Tennessee.<br />

Wildfires rage in the West and in Europe. And the Delta variant of COVID-19 extends its grip.<br />

It has also been just a few weeks since the fall of Kabul as the Taliban swept into victory following the<br />

American pullout after our 20-year failed effort at nation building. Now a chaotic and deadly evacuation<br />

has ended for U.S. troops, American citizens, our Afghan allies, and nationals of other countries struggling<br />

to flee the imposition of a harsh and despotic rule that we all know too well from the years prior to 9/11<br />

when the Taliban last controlled Afghanistan.<br />

While none of these events are presented in this issue of <strong>ZEKE</strong>, prior issues have featured numerous<br />

articles on climate change and the U.S. "War on Terror." We continue to publish <strong>ZEKE</strong> because we stand<br />

resolutely behind the importance of the documentary image, and the photographers who make them, in<br />

bringing awareness, nuance, and humanity to global issues.<br />

In this issue of <strong>ZEKE</strong>, we are thrilled to present the winners of the <strong>2021</strong> <strong>ZEKE</strong> Award for Documentary<br />

Photography. Sofia Aldinio’s award-winning project, Awake in the Desert Land, explores migration and historical<br />

memory as residents from Baja California, Mexico are uprooted from their land as a result of climate<br />

change. Nicolò Filippo Rosso’s project, Path Away, follows migrants from the Northern Triangle countries<br />

(Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador), as they flee violence and climate change to seek better opportunities<br />

in the U.S. only to find the border sealed as they approach their destination.<br />

We also present the extraordinary images by Italian photographer Emiliano Pinnozzotto and his project,<br />

The Emptying of the Andes, documenting an important, under-reported, and all too common story, where<br />

young people are fleeing their ancestral mountainous homes only to find a new form of poverty and alienation<br />

in urban centers—in this case in Peru—as climate change makes it increasingly difficult to sustain life<br />

at 13,000 feet.<br />

It is no coincidence that migration is a central theme in these three exhibits as the existential threat of<br />

climate change forces millions of people each year to seek less vulnerable environments.<br />

We are also thrilled to present 27 submissions from a call for entries from Black photographers on the<br />

theme “From Tulsa to Minneapolis: Photographing the Long Road to Justice” including first-place winner<br />

Donald Black Jr. for his story A Day No One Will Remember.<br />

In addition to these portfolios, Emily Schiffer has written a very provocative and inspiring feature article<br />

on Photography and Social Change exploring photographic artists who are making a difference by challenging<br />

the norms of both imagemaking and traditional structures of power.<br />

Lastly, on a personal note, I am very saddened to report that the namesake<br />

for <strong>ZEKE</strong> magazine, our thirteen-year-old beloved feline companion Ezekiel<br />

(aka Zeke), passed away in July following injuries suffered from a valiant fight<br />

with a wild animal. Barbara and I take solace that his exuberance for life, his<br />

unbounding energy, and his persistent demand for dignity often denied our<br />

non-human friends, live on in this magazine.<br />

Matthew Lomanno<br />

Glenn Ruga<br />

Executive Editor<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 1

This ongoing photography project<br />

by Sofia Aldinio documents<br />

how climate change is uprooting<br />

small, inland and coastal<br />

communities in Baja California,<br />

Mexico, that depend directly on<br />

natural resources to survive and thereby<br />

threatening cultural heritage.<br />

The peninsula is facing stronger hurricanes,<br />

changes in precipitation patterns<br />

and streamflow, loss of vegetation<br />

and soils and negative impact on fisheries<br />

and biodiversity. It is estimated that<br />

in Mexico and Central America, 3.9<br />

million people will be forced to leave<br />

their homes due to climate change.<br />

Photographed in four different communities<br />

across the peninsula, the work<br />

presented here documents the tension of<br />

the communities whose cultural heritage<br />

is at risk, adds a new perspective on<br />

the existing reports on climate change<br />

and migration and starts a conversation<br />

about how the loss of collective memory<br />

has a direct impact on the mental health<br />

of the next generation.<br />

The newest cemetery in San Jose de<br />

Gracia, Baja California, Mexico,<br />

January 17, <strong>2021</strong>. The small community<br />

has at least four different cemeteries<br />

generationally identified. The town lost<br />

most of its population after Hurricane<br />

Lester in 1992, the biggest storm the<br />

community has faced in its history.<br />

Since 2006, the community has lost 60<br />

members and has a population of 12<br />

today.<br />

2 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Awake in the Desert Land<br />

MIGRATION, CLIMATE CHANGE, AND HISTORICAL MEMORY<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD FIRST-PLACE WINNER<br />

By Sofia Aldinio<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 3

4 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Photo by Sofia Aldinio<br />

Felipe and Olga drive to buy food<br />

for their goats in San Juanico, Baja<br />

California, Mexico, January, 23, <strong>2021</strong>.<br />

The land is parched after no rain for<br />

three years, and the goats have been<br />

having a hard time finding the wild<br />

food that grows in the desert.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 5

Photo by Sofia Aldinio<br />

Felipe cooks octopus in Scorpion Bay,<br />

Baja California, January 12, <strong>2021</strong>. The<br />

weather is changing and we don’t get the<br />

same amount of fish anymore. “The lobster<br />

and octopus season used to last for two<br />

or three months, but it only lasted for a<br />

week this year,” he says. This particular<br />

day they pulled only one octopus that<br />

weighed 500gr, worth $2 USD. The local<br />

fishing community is stressing about what<br />

the future will bring them — to put enough<br />

food on their table and money to keep<br />

going. The elders are pushing the younger<br />

generation to stay clear of the industry, urging<br />

them to move to the cities for greater<br />

opportunities.<br />

6 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 7

Photo by Sofia Aldinio<br />

Olga and Felipe in their house in San<br />

Juanico, Baja California, Mexico,<br />

January 25, <strong>2021</strong>. Felipe has been<br />

struggling because the lobster season<br />

is dry. Olga, his wife, cooks tamales to<br />

sell on the weekends for extra money.<br />

8 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 9

Photo by Sofia Aldinio<br />

Chuy Rojas holds a piece of guaco on<br />

a ranch in San Ignacio, Baja California,<br />

Mexico, December 31, <strong>2021</strong>. The<br />

native plant grows in the hills of the<br />

desert. They have been relying on this<br />

herb to protect themselves from the virus<br />

during COVID-19 times.<br />

10 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 11

Photo by Sofia Aldinio<br />

Erick Rojas walks a cow that is about<br />

to get milked in San Ignacio, Baja<br />

California, Mexico, January 1, <strong>2021</strong>.<br />

Erick just returned to the farm after<br />

working in a mine on the east coast of<br />

the peninsula. “The pay was terrible and I<br />

couldn’t afford the living,” he says. He is<br />

currently harvesting local trees, extracting<br />

properties on behalf of an American<br />

pharmaceutical company.<br />

12 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 13

PATH<br />

AWAY<br />

TENS OF THOUSANDS FLEE VIOLENCE,<br />

CLIMATE CHANGE, AND ECONOMIC<br />

COLLAPSE FOR NORTH AMERICA<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD FIRST-PLACE WINNER<br />

By Nicolò Filippo Rosso<br />

Two months after Hurricanes Eta and<br />

Iota hit Central America in November<br />

2020, leaving 4.5 million victims of<br />

flooding and mudslides in their wake,<br />

11 thousand people gathered in San<br />

Pedro Sula, Honduras starting the<br />

first migrants’ caravan of the year heading<br />

towards the United States. <strong>2021</strong> began<br />

with one of the most significant migration<br />

waves of the last decade posing a difficult<br />

challenge for the new administration of<br />

President Joe Biden.<br />

The migrants’ crossing through gangcontrolled<br />

areas, deserts, and jungles<br />

is made even harder by the pandemic.<br />

International aid is scant, and many<br />

migrants’ shelters and charity kitchens<br />

closed their doors to avoid contagion.<br />

Thousands of migrants have reached<br />

Mexico while walking along its southern<br />

border with Guatemala, continuing the<br />

migration routes of the Gulf of Mexico, and<br />

the northern border with the United States to<br />

seek asylum. However, hundreds of families<br />

are expelled and returned to Mexico. Their<br />

asylum claims are denied with arguments<br />

based on Title 42, a U.S. statute that allows<br />

the expulsion of migrants from a country<br />

where a virus such as COVID-19 is present.<br />

This is their story.<br />

14 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Left: Lesbia Vanessa Bovadia, 35 years old,<br />

from Honduras, cries as she talks to a psychologist<br />

in a charity shelter in Tijuana, Mexico.<br />

After being separated from her children in the<br />

United States, she was deported to Mexico in<br />

2019. She doesn’t know where her children<br />

are, and she’s desperate to find them. The<br />

last time she saw them was in Chattanooga,<br />

Tennessee in 2018 before being arrested by<br />

the U.S. police.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 15

16 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Photo by Nicolò Filippo<br />

Rosso<br />

Guatemalan police officers take<br />

custody of a Honduran migrant<br />

who attempted to break the police<br />

barricade while driving a truck in<br />

Vado Hondo, Guatemala.<br />

January 18, <strong>2021</strong>.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 17

18 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Photo by Nicolò Filippo<br />

Rosso<br />

Migrants rest on a bridge<br />

in San Manuel, Tabasco,<br />

Mexico. March 6, <strong>2021</strong>.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 19

Photo by Nicolò Filippo<br />

Rosso<br />

Family members stand on<br />

a riverside in Tapachula,<br />

Mexico. They are looking for<br />

an entrance to the river to<br />

bathe and wash their clothes.<br />

January 29, <strong>2021</strong>.<br />

20 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 21

Photo by Nicolò Filippo<br />

Rosso<br />

A boy sits on the ground<br />

as the migrant caravan is<br />

stopped by a barricade of<br />

the Guatemalan police. Vado<br />

Hondo, Guatemala.<br />

January 16, <strong>2021</strong>.<br />

22 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 23

24 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Photo by Nicolò Filippo<br />

Rosso<br />

More than a thousand<br />

migrants from Mexico, Central<br />

America, and South America<br />

live in the Jesus’ Ambassador<br />

church in Tijuana, Mexico.<br />

A Honduran man works as a<br />

barber for the community.<br />

April 24, <strong>2021</strong>.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 25

Migration from the<br />

Phoenix<br />

Channel<br />

Islands<br />

Mexicali<br />

Guadalupe<br />

Hermosillo<br />

A<br />

Chihuahua<br />

G o l f o d e C a l i f o r n i a<br />

La Paz<br />

Culiacan<br />

Durango<br />

MEXICO<br />

Saltillo<br />

Ciudad Victoria<br />

Monterrey<br />

Zacatecas<br />

Aguascalientes San Luis Potos<br />

Tepic<br />

Leon<br />

Queretaro<br />

Guadalajara<br />

Morelia Pachu<br />

Colima<br />

Toluca<br />

Mexico<br />

Chilpancingo<br />

P a c i f i c<br />

Olga Marina Rodriguez<br />

Gonzalez holds her two<br />

babies while waiting for<br />

the cargo train known as La<br />

Bestia “The Beast.” People<br />

jump on the moving train to<br />

reach Northern Mexico, on<br />

their way to the United States.<br />

Coatzacoalcos, in Veracruz,<br />

Mexico. February 16, <strong>2021</strong>.<br />

Photo by Nicolò Filippo Rosso.<br />

O c e a n<br />

26 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Northern Triangle<br />

A last resort to stay alive<br />

by Daniela Cohen<br />

Little Rock<br />

ustin<br />

i<br />

ca<br />

City<br />

MEXICO<br />

Guatemala<br />

The significant increase<br />

in migration from<br />

Central America to the<br />

U.S. in recent years<br />

indicates rapidly deteriorating<br />

conditions<br />

in the region that have left people<br />

no choice but to flee in order to<br />

survive. The majority of migrants<br />

come from Honduras, Guatemala<br />

and El Salvador, together referred<br />

to as the Northern Triangle.<br />

Around 311,000 migrants<br />

from this region arrived in the<br />

U.S. between 2014 and 2020<br />

according to the Congressional<br />

Research Service. In June <strong>2021</strong>,<br />

US Customs and Border Protection<br />

(CBP) recorded almost 180,000<br />

Baton Rouge<br />

GUATEMALA<br />

San Salvador<br />

Jackson<br />

EL SALVADOR<br />

BELIZE<br />

HONDURAS<br />

Tegucigalpa<br />

Managua<br />

Havana<br />

San Jose<br />

Atlanta<br />

Montgomery<br />

NICARAGUA<br />

COSTA RICA<br />

Tallahassee<br />

Columbia<br />

migrants – including 15,000 unaccompanied<br />

minors and 50,000<br />

families – the highest monthly total<br />

in over 20 years. But given that<br />

one third of these migrants have<br />

crossed the border previously, the<br />

actual increase in migration may<br />

not be as high.<br />

“It’s one of the hardest decisions<br />

people are often making,” says<br />

Andani Alcantara Diaz, supervising<br />

attorney of removal defense for<br />

the Refugee and Immigrant Center<br />

for Education and Legal Services<br />

(RAICES) in Austin, Texas. “That’s<br />

why you see people go through<br />

really horrible things and still not<br />

leave for a while because they<br />

don’t want to leave their homes,<br />

their families, everything they<br />

know, behind. But at a certain<br />

point, it’s the only thing they can<br />

do to stay alive.”<br />

The main drivers of migration<br />

from the Northern Triangle are violence<br />

and socioeconomic insecurity,<br />

which frequently overlap, and are<br />

exacerbated by climate change.<br />

“Many migrants are fleeing<br />

gangs or other sorts of dangerous<br />

organizations that have harmed<br />

them and their families,” says<br />

Alcantara Diaz, “And they know<br />

they can’t go to the government,<br />

that the government in their countries<br />

is not going to protect them.”<br />

Many of these gangs originated<br />

in Los Angeles in the 1980s and<br />

were later deported back to their<br />

home countries in the region.<br />

Women and children are<br />

particularly vulnerable to violence,<br />

often within the home. Honduras<br />

and El Salvador have some of the<br />

highest rates of femicide worldwide.<br />

Endemic corruption means<br />

that the police are often involved<br />

and those responsible are not held<br />

to account. The threat of violence<br />

by both gangs and family members<br />

has led to a surge in unaccompanied<br />

minors arriving at the U.S.<br />

border since 2014.<br />

Socioeconomic drivers of migration<br />

include widespread inequality<br />

and poverty and pervasive lack<br />

CUBA<br />

JAMAICA<br />

Panama<br />

Bahama<br />

Islands<br />

Nassau<br />

Long Island<br />

G r e a t e r A n t i l l e s<br />

Caribbean Sea<br />

of work opportunities. With 40<br />

percent of the population under the<br />

age of 20, youth can either stay in<br />

precarious working conditions or<br />

try to seek opportunities elsewhere.<br />

Climate change has led to prolonged<br />

droughts and crop losses.<br />

The coffee industry has been hit<br />

hard by both an increase in the<br />

coffee leaf rust fungus and low<br />

international coffee prices, jeopardizing<br />

a critical source of seasonal<br />

income for over a million families.<br />

In addition, in 2020, the region<br />

was devastated by the COVID<br />

pandemic and back-to-back category<br />

4 Hurricanes Eta and Iota,<br />

which displaced over 500,000<br />

people, leaving many homeless<br />

and without access to clean<br />

drinking water. According to the<br />

World Food Programme, approximately<br />

eight million people are<br />

facing hunger, including a quarter<br />

with emergency levels of food<br />

insecurity. Almost 15 percent of<br />

people surveyed in January <strong>2021</strong><br />

reported plans to migrate, up eight<br />

percent from 2018.<br />

A Migrant Family’s<br />

Journey<br />

Angel Antonio Mejia Gonzales,<br />

from Danli, Honduras, felt he<br />

had no choice but to leave. The<br />

33-year-old and his wife, Olga<br />

Marina Rodriguez Montoya, 27,<br />

had both been affected by violence<br />

and wanted to protect their<br />

children. Mejia Gonzales is eager<br />

to work but says there were no<br />

prospects for work in Honduras.<br />

And Hurricanes Eta and Iota took<br />

what little they had.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 27

Migrants from the Northern Triangle (mostly from Honduras) sit on a cargo train in Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz<br />

(Mexico) on the way to Mexico City where they will find another train heading north toward the U.S. border.<br />

February 16, <strong>2021</strong>. Photo by Nicolò Filippo Rosso.<br />

“I don’t want my children to be in<br />

the street all their life,” says Rodriguez<br />

Montoya.<br />

In January <strong>2021</strong>, the couple joined<br />

the migrant caravan leaving Honduras<br />

with their four children: eight-yearold<br />

Angel Isai, seven-year-old Yosari<br />

Yolanda, five-year-old Heili Maite, and<br />

three-year-old Jeremy Santiago. The<br />

8,000-person caravan would offer<br />

more protection from violence than<br />

going alone.<br />

With only 2,000 lempira ($84 US)<br />

in hand, they started the long journey,<br />

travelling by bus, train, car and on foot<br />

to reach neighboring Guatemala. But<br />

a coordinated military operation by<br />

Guatemalan law enforcement, upholding<br />

an agreement to prevent migrant flows<br />

north, blocked the caravan. Half of the<br />

migrants were sent back to Honduras,<br />

but the Mejia Gonzales family managed<br />

to continue on foot. Traversing the Rio<br />

Montagua day after day, they lost their<br />

shoes in the mud. Hungry, thirsty, and<br />

exhausted, they walked on.<br />

“It was hard to see the kids sleeping<br />

on the ground,” says Mejia Gonzales.<br />

“Nobody wants to see their kids in that<br />

situation.”<br />

Money quickly ran out and they<br />

were forced to beg for help along<br />

the way, help they believe was given<br />

because of their children.<br />

Alcantara Diaz describes the numerous<br />

challenges migrants face when fleeing<br />

– threat of kidnapping by Mexican<br />

cartels to extort ransom from family<br />

members in the U.S.; sexual violence<br />

against women; mistreatment by law<br />

enforcement in countries en route; lack<br />

of food and money; threat of being<br />

captured and trafficked by gangs; and<br />

risk of death by crossing at dangerous<br />

points like the desert or a river.<br />

And even if people make it into the<br />

U.S., their struggles do not end there.<br />

Inhumane Treatment<br />

by Border Control<br />

The Mejia Gonzales family has tried<br />

to cross the U.S. border to seek asylum<br />

three times, all unsuccessful.<br />

The first was in February <strong>2021</strong>, when<br />

they arrived in Piedras Negras, Mexico,<br />

to find everything covered in ice. A man<br />

overseeing the place where migrants<br />

were crossing the river demanded a lot<br />

of money. The family paid all they had –<br />

500 pesos given to them by a Mexican<br />

girl – to be able to cross.<br />

Mejia Gonzales set out first to test<br />

the river’s depth and then returned for<br />

his wife and children. The cold water<br />

was moving fast, and one of the children<br />

– all tied to the parents – almost<br />

got swept away but was rescued by<br />

a fellow migrant. Finally, alongside<br />

many other Honduran, Guatemalan<br />

and El Salvadoran families, they made<br />

it across.<br />

They were soon apprehended by<br />

border officials, who took them to a<br />

facility where they did not even provide<br />

water. Rodriguez Montoya cried, asking<br />

for asylum, but an officer told her<br />

they see hundreds of families and every<br />

situation is the same.<br />

The family was then put in a CBP car<br />

vehicle with other migrants and supervised<br />

to make sure nobody went back.<br />

Late that night, they were dropped off<br />

on the Mexican side of the bridge.<br />

This is Title 42 in action, an order<br />

passed by the Trump administration<br />

allowing the expulsion of migrants<br />

under the auspices of the current public<br />

health emergency.<br />

“It is a very concerning tool that [the<br />

Biden] administration is still using,”<br />

says Alcantara Diaz. “Their claim is<br />

that they’re making sure that people<br />

are not bringing in more virus . . ..”<br />

Yet they are returning people who are<br />

not sick, even though Immigration and<br />

Customs Enforcement has the capacity<br />

to conduct COVID testing.<br />

And while the order states that the<br />

intent is to avoid holding migrants in<br />

congregate settings, it is being used to<br />

expel migrants after they have spent<br />

long periods in these settings.<br />

Title 42 contravenes international<br />

law, which requires specific screening<br />

processes for people seeking asylum so<br />

that they are not sent back to dangerous<br />

situations.<br />

Advocates are also concerned that<br />

the order may be used disproportionately<br />

against people from certain<br />

28 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

countries or skin colors, targeting the<br />

largely Black, Indigenous and Latino<br />

migrants who are crossing into the U.S.<br />

at land borders.<br />

A few days after being expelled,<br />

the Mejia Gonzales family tried to<br />

cross again. Border officials yelled at<br />

them, hit their oldest son, and called<br />

Rodriguez Montoya a liar.<br />

“Just because someone is a migrant,<br />

they treat us however they want,” says<br />

Mejia Gonzales, “but everyone is<br />

human in life. We’re all people.”<br />

Since March 2020, CBP has<br />

executed over 642,700 expulsions<br />

under Title 42.<br />

A Third Attempt<br />

Increasingly desperate, Rodriguez<br />

Montoya borrowed money from her<br />

brother in Waco, Texas to make a<br />

third crossing at Reynosa in April. This<br />

time she went alone with the children,<br />

paying “coyotes” (human smugglers) to<br />

help her. Mejia Gonzalez remained in<br />

Mexico, planning to cross afterward so<br />

they could reunite in the U.S.<br />

This journey, which Rodriguez<br />

Montoya calls “a horror movie,” started<br />

with two weeks in an abandoned<br />

house where she heard that organ and<br />

human trafficking had been committed.<br />

Migrants were told that if the police<br />

arrived, they would be killed.<br />

“We already paid them, so our<br />

lives had no value anymore,” says<br />

Rodriguez Montoya.<br />

The crossing involved traversing<br />

woods inhabited by wild animals<br />

to reach the river, then hours of fast<br />

walking. Carrying two of her children<br />

who could not walk by themselves, she<br />

prayed for strength. They crossed the<br />

river on a raft and were picked up by<br />

border patrol in McAllen, Texas.<br />

Left waiting wet, hungry, and thirsty<br />

for hours, they were finally taken to a<br />

bridge, where officers gave the children<br />

juice and biscuits.<br />

“I was happy because I thought I<br />

would get to rest with my children,”<br />

says Rodriguez Montoya.<br />

Instead, they were taken to “la<br />

hielera” or “refrigerator,” a large<br />

cement space notorious for its low<br />

temperatures. They were given some<br />

food, but after not eating for so long,<br />

Yosari Yolanda started to vomit. The<br />

officers paid no attention until her<br />

mother cried, “My daughter is going to<br />

die here because you won’t take me to<br />

the hospital.”<br />

Finally, Rodriguez Montoya and<br />

her children were taken to the hospital<br />

in Laredo, Texas, and Yosari Yolanda<br />

tested to ensure she didn’t have<br />

COVID. After giving her medicine, a<br />

nurse brought milk and cornflakes, and<br />

she was finally able to eat.<br />

The next day, the migrants were put<br />

on a bus and driven back to Mexico.<br />

Rodriguez Montoya says everyone got<br />

off the bus crying. “I didn’t want to go<br />

back after everything that happened to<br />

me. I told them, ‘It’s better that you kill<br />

me or that you put me in jail and leave<br />

my children here because my brother<br />

lives in the U.S. But do not send me<br />

back to Mexico, the cartels are going<br />

to torture me with my children.’”<br />

A Life in Limbo<br />

Along with thousands of other migrants,<br />

the Mejia Gonzales family is now<br />

stuck in Mexico. They recently applied<br />

for help online through Al Otro Lado,<br />

a binational advocacy and legal aid<br />

organization, but have no idea when<br />

they will hear back. They sleep on<br />

carton boxes in a single room in Piedras<br />

Negras and sell candies to survive. “Los<br />

gates,” the local military police infamous<br />

for committing numerous crimes with<br />

impunity, is a lurking presence.<br />

Despite the trauma the family has<br />

been through and continues to endure,<br />

they cannot consider returning to<br />

Honduras.<br />

“I don’t want to give up, I want<br />

to keep fighting,” says Rodriguez<br />

Montoya, “but I’m very scared.”<br />

Vice President Kamala Harris’s recent<br />

trip to Central America to discourage<br />

migration to the U.S. disregards the fact<br />

that people are fleeing for their lives<br />

says Alcantara Diaz. “These big proclamations<br />

aren’t going to change the reality<br />

and the day-to-day for people who<br />

are trying to make a decision whether to<br />

leave everything they know behind just<br />

to try to stay alive.”<br />

A young girl watches out from a bus window. People use different types of transportation to reach the border<br />

between Honduras and Guatemala. January 15, <strong>2021</strong>. Photo by Nicolò Filippo Rosso.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 29

<strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD HONORABLE MENTION WINNER<br />

Kirsten Rebekah Bethmann<br />

Bear and Fanny, United States<br />

30 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

T<br />

his series explores the<br />

complexities of marriage<br />

when a spouse is afflicted<br />

with dementia and their<br />

partner is required to take on<br />

the role of caretaker. Layers of<br />

emotion surface as the ability to<br />

remain an equal in the partnership<br />

dissolves and the roles begin<br />

to resemble that of a parent and<br />

child.<br />

This body of work is the result<br />

of three months when I moved<br />

back in with my parents at age<br />

43 to help my mother care for<br />

my father who, at 75, was losing<br />

his battle with severe vascular<br />

dementia. Instead of watching<br />

my mother care for my father, I<br />

chose to bear witness to a wife<br />

struggling to manage her internal<br />

conflicts with losing the love of<br />

her life to a disease that stole<br />

him from her. I attempted to<br />

remove myself personally in order<br />

to tell this story from my mother’s<br />

point of view.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 31

<strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD HONORABLE MENTION WINNER<br />

Misha Maslennikov<br />

The Don Steppe, Russian Federation<br />

Yurka-Shut behind his farm house in the steppe. Senshin<br />

farm, village of Oblivskaya, Rostov-on-Don region,<br />

Russia. February 2012.<br />

32 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Picture yourself in the<br />

midst of the steppe,<br />

somewhere out in the<br />

open, looking at the<br />

horizon. You find your gaze drawn<br />

beyond this meeting of earth<br />

and sky, to the far side of the<br />

visible, so much that you can see<br />

nothing other than this inexorable<br />

boundary. What’s out there? What<br />

kind of life beyond imagining?<br />

Perhaps something utterly different,<br />

utterly unknown: seas and<br />

mountains, the crystalline glint<br />

of office windows in concrete<br />

canyons, elegant shop windows,<br />

the fireplaces of ski lodges?<br />

Perhaps climbing the corporate<br />

ladder with its strict dress code, or<br />

beach volleyball in stylish bikinis?<br />

But you stand there for a while in<br />

silence, just a bit longer, and all<br />

this falls away. There is only the<br />

earth under your feet, near and<br />

far, as far as the eye can see, and<br />

the sky above your head, around<br />

you and about you, and it all runs<br />

together as one, even within you,<br />

and it’s as if there is no longer an<br />

observer.<br />

Top. Repairing the furnace<br />

in an abandoned house<br />

near Senshin farm, village of<br />

Oblivskaya, Rostov-on-Don<br />

region, Russia. January 2011.<br />

Bottom. Mother and son in<br />

the yard of their house. Frolov<br />

farm, village of Oblivskaya,<br />

Rostov-on-Don region, Russia.<br />

July 2010<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 33

<strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD HONORABLE MENTION WINNER<br />

Ashkan Shabani<br />

“Eshgh, Tars, Azadi” (Love, Fear, Freedom)<br />

Rana rests on Negin’s lap in a quiet place in the middle of the jungle.<br />

34 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Top: Muhammad and Amir Ali going shopping in a mall in Tehran, one of their<br />

favorite hobbies. Holding hands in public without fear is a dream for them.<br />

Bottom: Muhammad and Amir Ali are living in a 60-meter rental house in Tehran.<br />

They have to hide the true nature of their relationship, and even told the landlord that<br />

they are cousins in order to rent the house.<br />

Iranians face many obstacles.<br />

Some come from the regime<br />

imposing ideological restrictions<br />

and political pressure,<br />

while others result from the strained<br />

economic situation. Still, more pressure<br />

comes from the public’s closed,<br />

traditional way of thinking.<br />

Homosexuality is a target that<br />

both society and the regime are<br />

against. In post-revolutionary<br />

Iran, any type of sexual activity<br />

outside a heterosexual marriage<br />

is forbidden and homosexual sex<br />

is punishable by death based on<br />

the laws of Sharia. For over 40<br />

years, the Islamic Republic of<br />

Iran has denied that gays exist<br />

in the country. Iran is among the<br />

few countries in the world where<br />

homosexuals still risk execution<br />

for their sexual orientation. As a<br />

result, gay men and women live<br />

with systematic suppression, discrimination,<br />

family rejection, and<br />

judicial problems. They live their<br />

lives in fear every day. Despite<br />

this, under the skin of Tehran and<br />

many other cities, homosexuals<br />

find ways to overcome these<br />

restrictions so they can pursue<br />

love, life, and a future that recognizes<br />

their existence. The idea of<br />

freedom still seems remote.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 35

<strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD HONORABLE MENTION WINNER<br />

Richard Sharum<br />

Campesino Cuba<br />

Two women in the village of Providencia separate the rice from their husks as they<br />

prepare lunch for the house. Because rice is not grown in the immediate area,<br />

it has been traded for coffee with a nearby valley known for its rice production.<br />

Providencia, Cuba. 2019.<br />

36 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Afour-year documentation<br />

of the Campesino<br />

people and culture of<br />

rural Cuba. Campesino<br />

means “farmer” or “rural peasant”<br />

and includes some of the<br />

most poverty-stricken populations<br />

on the island. They number close<br />

to 20 million and occupy close to<br />

85% of the land in Cuba. Whereas<br />

most coverage of Cuba consists<br />

of Havana or other major cities,<br />

this project aims at spending time<br />

with those most often unseen or<br />

unspoken of, those who make up<br />

the agricultural backbone of the<br />

nation, and the families intertwined<br />

within.<br />

Above: A woman stands in a typical<br />

guano hut in the small village of<br />

Peladero, in the Sierra Maestra<br />

mountain range, in eastern Cuba. A<br />

home-made broom leans against the<br />

house, made of palm fronds. Housing<br />

in rural Cuba usually consists of these<br />

same materials, with a dirt floor. The<br />

roofs, also made of palm, are effective<br />

at keeping out rain and oppressive<br />

heat. Peladero, Cuba. 2019.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 37

<strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD HONORABLE MENTION WINNER<br />

David Verberckt<br />

Unending Ethnic Conflict in Burma<br />

A Kachin girl who has been living since 2011 in a camp for internally displaced<br />

persons in Kachin State. Over 100,000 Kachin are displaced within their own country<br />

as a result of a long-lasting armed conflict between the Myanmar Army and the<br />

Kachin Independence Army (KIA). Ziun IDP camp in government-controlled territory,<br />

Myanmar, March 2019<br />

38 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

During the past years, I<br />

have extensively visited<br />

Myanmar’s borderland<br />

states of Rakhine,<br />

Kachin and Karen, in governmentcontrolled<br />

areas and ethnic armed<br />

groups-controlled territory, in<br />

order to try to understand, access<br />

and visualize the country’s neverending<br />

ethnic conflicts.<br />

With 70 years of ethnic<br />

conflicts, most ethnic groups have<br />

established strong armed groups,<br />

parallel administrations, schools<br />

and health centers in areas that<br />

are under their full control along<br />

the Thai border (Karen and Shan)<br />

and Chinese border (Kachin).<br />

Top: Democratic Karen Buddhist Army<br />

parade with wooden guns. Kayin State,<br />

Myanmar, November 2018<br />

Bottom: Internally displaced persons that<br />

fled from Baung Wheit village in April<br />

2019 after the village was attacked by<br />

government forces with heavy artillery.<br />

Villagers sought refuge at a nearby<br />

temple. Ninety people live now on<br />

the compound of the temple. Naressa<br />

Temple, Mrauk-Oo township, Rakhine<br />

State, Myanmar, October 2019<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 39

FROM TULSA TO MINNEAPOLIS<br />

Photo by Joshua Rashaad<br />

McFadden<br />

After the last speech at the<br />

Commitment March Rally on<br />

August 28, 2020, thousands<br />

of people flooded the streets of<br />

Washington, D.C., to protest<br />

police brutality in America.<br />

40 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

PHOTOGRAPHING THE LONG ROAD TO JUSTICE<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 41

FROM TULSA TO MINNEAPOLIS: PHOTOGRAPHING THE LONG ROAD TO JUSTICE<br />

Several consistent themes arise across<br />

the thousands of images documenting<br />

the last year of racial justice<br />

protests in the United States— the<br />

raised Black power fist; a surge of<br />

civilian bodies facing off against<br />

a line of stony-faced police forces; eyes<br />

raised to the camera in triumphant challenge<br />

of the powers that be. Each of these<br />

poignant moments draw from long histories<br />

of photography on the American struggle<br />

for justice within a country whose deeply<br />

embedded racism spans centuries built of<br />

settler colonization and the enslavement of<br />

Black people.<br />

An especially horrific part of that long<br />

history of racial terror and subjugation in<br />

America is the 1921 Tulsa, Oklahoma massacre<br />

of Black residents by a white mob.<br />

While many Black Americans have long<br />

held the memory of that deadly night and<br />

the several preceding years of white mob<br />

violence that erupted across the nation,<br />

few photographs exist to bear ongoing<br />

witness to the death and destruction. In the<br />

decades since, however, Black Americans<br />

have utilized the camera’s evidentiary<br />

power as a tool in the twin struggles to<br />

humanize Black lives and depict racial<br />

injustice. The evisceration of Tulsa’s prosperous<br />

Black community and the 2020<br />

racial justice protests that represent the<br />

largest social justice movement in U.S.<br />

history are separated by nearly 100 years,<br />

serving as troubling markers of how little<br />

progress has been made on this long road<br />

to justice. Yet, the influx of visual storytelling<br />

by those whose lives are held in the<br />

balance and social media’s access to a<br />

rapt global audience offers new hope that<br />

justice might yet be realized.<br />

Since Black Lives Matter’s 2013 beginnings<br />

as a hashtag following the 2013<br />

shooting death of Black teenager Trayvon<br />

Martin, the movement gained steam as<br />

both a social media campaign and a<br />

series of national protests in the wake of<br />

each Black person killed by police brutality.<br />

It’s vital to understand how much this<br />

movement (and many other contemporary<br />

social justice efforts) owes to the wide<br />

circulation of visual evidence online. While<br />

such egregious acts of racial violence and<br />

police brutality have been rampant since<br />

the advent of American policing, it is the<br />

increasing presence of digital cameras that<br />

have ushered in an era where racism can<br />

be documented and therefore demand further<br />

reckoning. As BLM builds on the visual<br />

rhetoric of Civil Rights Movement photography,<br />

the relationship between street-level<br />

activism and the power of the camera is<br />

increasingly revealed.<br />

The collection of 23 photographs on<br />

these pages is drawn from over 500<br />

images submitted by photographers who<br />

answered the call to share their visual<br />

interpretations of the Long Road to Justice.<br />

Importantly, the work is primarily made<br />

by Black photographers whose lived<br />

experiences of racial injustice and respect<br />

for Black lives is tangibly felt across the<br />

photo essay. From Brian Branch-Prices’s<br />

intimate look at Black musicians to Kenechi<br />

Unachukwu’s We Still Here, a picture of<br />

Black resilience emerges. Donald Black<br />

Jr.’s loving ode to Black childhood symbolizes<br />

exactly what we fight for: a future<br />

where the threat of police brutality against<br />

our children, our mothers, our fathers and<br />

brothers is a thing of the past.<br />

The work to realize that future, however,<br />

is far from over. Even as these images of<br />

Black life compel the world to recognize<br />

the shared humanity of all people, there<br />

remains a stark disconnect between the<br />

realities visualized by our photography<br />

and the widespread realization of social,<br />

political, and economic reform. The<br />

struggle for racial justice continues and we<br />

lift our cameras as we steady our resolve,<br />

ready to meet the call wielding our choice<br />

of weapons.<br />

—Tara Pixley<br />

Program Credits<br />

Chair:<br />

Lisa DuBois<br />

Jurors:<br />

Laylah Amatullah Barrayn<br />

Lisa DuBois<br />

Anthony Barboza<br />

Eli Reed<br />

Jamel Shabazz<br />

42 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Best-of-Show Award<br />

Donald Black Jr.<br />

A Day No One Will Remember<br />

A collection of images created by Donald<br />

Black Jr. over the past 10 years. After returning<br />

home to Cleveland, Ohio, he started creating<br />

images that only an insider could see<br />

and began making images that represented<br />

his perception of his reality. Seeing himself<br />

and where he came from has influenced<br />

an obsession to photograph children in his<br />

community.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 43

FROM TULSA TO MINNEAPOLIS: PHOTOGRAPHING THE LONG ROAD TO JUSTICE<br />

Above<br />

Photographer: Titus Brooks Heagins<br />

Exhibit Title: Where the Sidewalk Ends<br />

This project represents a visual dialog<br />

that interrogates the lives of those who<br />

live in the margins of society.<br />

Caption: Brittany and Brianna<br />

Right top<br />

Photographer: Brian Branch-Price<br />

Exhibit Title: Rhythm and Praise, an<br />

Epic Journey<br />

This project reflects the expressions,<br />

thoughts and actions of a people, of a<br />

culture and of a folk who love to sing,<br />

dance, shout, give, teach, preach, cut a<br />

step all in the name of gospel music.<br />

Caption: Percy Bady, Newark, New<br />

Jersey<br />

Right below<br />

Photographer: Teanna Woods Okojie<br />

Exhibit Title: Black Boy Joy<br />

Black Boy Joy is a series of multiple<br />

images spanning from 2013 to <strong>2021</strong><br />

depicting young African youth and<br />

young men in various environments<br />

experiencing pure joy.<br />

44 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Above<br />

Photographer: Brian Branch-Price<br />

Exhibit Title: BLM: The Third<br />

Expressing the frustrations of an oppressed<br />

community reacting to social injustices, economic<br />

apartheid, Jim Crow, over-policing,<br />

lynching, inhumanity, during peaceful and<br />

confrontational protest in New York, New<br />

Jersey, Philadelphia, Richmond, and D.C.<br />

Caption: Livia Rose Johnson, 20, march<br />

organizer during a Justice for George Floyd<br />

protest and rally in New York on June 4, 2020<br />

Left<br />

Photographer: Raymond W. Holman, Jr.<br />

Exhibit Title: COVID-19 in Black America<br />

Environmental portraits of Black and brown<br />

skin people with first-hand experience of<br />

COVID-19 – having recovered, lost family<br />

members, been mentally challenged by<br />

social isolation, and figuring out how to<br />

adjust and make a new pathway.<br />

Caption: A Princeton University student<br />

experiencing a year of online classes and<br />

isolation due to COVID-19, but becoming a<br />

stronger human being through this challenge.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 45

FROM TULSA TO MINNEAPOLIS: PHOTOGRAPHING THE LONG ROAD TO JUSTICE<br />

Above<br />

Photographer: Lisa DuBois<br />

Exhibit Title: MAAFA: The Great African<br />

Tragedy<br />

A term meaning “Great Disaster” in Swahili,<br />

MAAFA ceremonies honoring ancestors<br />

became part of African-American culture<br />

at the onset of slavery — the African<br />

Holocaust — and continue today, honoring<br />

the generations that lived and died as slaves<br />

and bringing catharsis.<br />

Caption: A woman prepares for a ritual<br />

using a bell. It is believed ancestors can hear<br />

this sound.<br />

Right<br />

Photographer: Imari DuSauzay<br />

Exhibit Title: We the People<br />

Started by Joe of Saint James Joy, these<br />

Block Party sessions in the heart of Brooklyn’s<br />

Clinton Hill celebrated the community<br />

without separations, embracing all who came<br />

to share their joy in collective dance free<br />

from imposed constructs of social stress and<br />

all “isms,” healing through a collective of We<br />

The People.<br />

Caption: FLIGHT<br />

46 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Left<br />

Photographer: Cheryle Galloway<br />

Exhibit Title: Out of Many?<br />

Photographing as an archaeologist<br />

discovering things left behind by a lost<br />

civilization, removing social constructs<br />

used as tools to divide us in the hope to<br />

breakdown all walls to mutuality, Out of<br />

Many? asks, how does America heal to<br />

become one nation?<br />

Caption: “How much time do you want<br />

for your ‘progress’”? James Baldwin. The<br />

White House, Washington, D.C.<br />

Lower Left<br />

Photographer: LeRoy W. Henderson<br />

Exhibit Title: Expressions Against Racism<br />

and Oppression in America<br />

These photographs represent growing<br />

public expression against racial injustice<br />

and oppression in America. People of all<br />

ages are beginning to become more vocal.<br />

Significantly, young people in growing<br />

numbers are taking the leadership in this<br />

movement for change.<br />

Above<br />

Photographer: Collette Fournier<br />

Exhibit Title: Taking the Struggle to the<br />

Streets—Black Lives Always Mattered<br />

After learning my people were once slaves<br />

as a youngster, I have been on a visual<br />

journey to document my people in the<br />

Diaspora. Working on a series enables me<br />

to revisit and expand upon my ideas, knowing<br />

that the story rarely ends.<br />

Caption: Suffern, NY; Die-In for Kimani<br />

Gray, 2013. Willie Trotman, President of<br />

NAACP Spring Valley, Community activist<br />

Ken Mercer and the student community at<br />

a Die-In protest in Rockland County, NY.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 47

FROM TULSA TO MINNEAPOLIS: PHOTOGRAPHING THE LONG ROAD TO JUSTICE<br />

Above<br />

Photographer: Shoun Hill<br />

Exhibit Title: Protests 2020<br />

These are photographs from 2020 of the protests<br />

surrounding the murders of unarmed African-<br />

Americans by police officers in the USA.<br />

Caption: A participant holds a sign during a vigil and<br />

coming together for George Floyd, Sunday, May 31,<br />

2020, in Inwood Park in Manhattan.<br />

Right<br />

Photographer: Kevin Bernard Jones<br />

Exhibit Title: March on Washington 2020—A<br />

People’s Perspective<br />

The 2020 March on Washington for racial justice and<br />

police reform organized by Reverend Al Sharpton and<br />

the National Action Network after the public murder<br />

of George Floyd just months before by a Minneapolis<br />

police officer. Held fifty-seven years after Martin<br />

Luther King Jr.’s 1963 “I Have a Dream.”<br />

Bottom<br />

Photographer: Khary Mason<br />

Exhibit Title: It is a Difficult Time to Convict a Hero<br />

In this series, Mason explores media’s influence upon<br />

society’s perceptions of law enforcement, and the<br />

silence vs. duty of Black officers in America.<br />

Caption: Chasing freedom...<br />

48 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Left<br />

Photographer: Deja Nycole<br />

Exhibit Title: Black & Dangerous<br />

A collaborative project utilizing poetry,<br />

portraiture, and reportage to redefine the<br />

way Black people are perceived because of<br />

stereotypes.<br />

Caption: Ed Ross, 21, Accokeek, Maryland<br />

Above<br />

Photographer: Thaddeus Miles<br />

Exhibit Title: It Took Me to My Knees!<br />

Caption: Tired & Ready<br />

Top:<br />

Photographer: Burroughs Lamar<br />

Exhibit Title: National Action Network<br />

(NAN) March on Washington<br />

Rev. Al Sharpton’s NAN organization<br />

brought together masses of people of<br />

varying ethnicities in a peaceful march that<br />

included a speech by Martin Luther King<br />

Jr.’s son MLK,III, leaving a spirit of hopefulness<br />

that the tragic deaths and injustices<br />

afflicting Africans Americans for centuries<br />

will cease the need for future marches.<br />

Caption: Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial.<br />

Washington, D.C.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 49

FROM TULSA TO MINNEAPOLIS: PHOTOGRAPHING THE LONG ROAD TO JUSTICE<br />

50 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong><br />

Top<br />

Photographer: Tara Pixley<br />

Exhibit Title: Our Streets<br />

Taken across multiple 2020 protests<br />

in Los Angeles, these photos speak to<br />

the true spirit of the Black Lives Matter<br />

movement: peaceful showings of solidarity,<br />

community action, and expressions of<br />

democratic public assembly in the face of<br />

COVID-19 and racism’s twin pandemics.<br />

Caption: People stared with open admiration<br />

at a Black man on horseback who<br />

rode in circles carrying the Pan-African<br />

flag.<br />

Above<br />

Photographer: Kenechi Unachukwu<br />

Exhibit Title: We Still Here<br />

People from all ages and ethnicities led by<br />

young Black men and women congregated<br />

at the capitol to voice their frustrations<br />

about a system that has led to the wrongful<br />

death of many Black citizens at the<br />

hands of the police.<br />

Right<br />

Photographer: Michael Young<br />

Exhibit Title: When Will it be Enough.<br />

2020—A Year of Resistance<br />

Caption: Black Issues 1619 -2019. Image<br />

taken at the Black Lives Matter Harlem<br />

Street Mural which had been vandalized<br />

and is under repair.

Top<br />

Photographer: Sheila Pree<br />

Bright<br />

Exhibit Title: #1960Now: Jim<br />

Crow 2.0<br />

Growing up in the Jim Crow<br />

era, my parents never spoke of<br />

their experiences until Trayvon<br />

Martin’s death by police brutality.<br />

My mother said, “I didn’t<br />

want you to hate white people. I<br />

can’t believe I would see the day<br />

that Black people’s oppression<br />

still exists.”<br />

Caption: Statue of Dr. Martin<br />

Luther King Jr. by Jamaican-born<br />

Basil Watson installed in <strong>2021</strong>,<br />

Atlanta, GA.<br />

Lower Left<br />

Photographer: Eva Woolridge<br />

Exhibit Title: We are Not Free<br />

Until We are All Free<br />

An exhibition that discusses<br />

the relationship between all<br />

marginalized groups who are in<br />

the fight to live freely as they<br />

are, with images from marches<br />

for Black Lives, Palestine, and<br />

Black Trans Lives. Because we<br />

all matter.<br />

Caption: True Patriot.<br />

Above<br />

Photographer: Reece T.<br />

Williams<br />

Exhibit Title: On the<br />

Anniversary of My Profound<br />

Confusion<br />

My earnest attempt to not only<br />

chronicle the 2020 marches<br />

for Black lives and living, but<br />

to understand how and why<br />

this moment, out of all the<br />

moments, was chosen as “a<br />

reckoning,” and how only now?<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 51

Interview<br />

JOSEPH RODRIGUEZ<br />

Joseph Rodriguez is a New York-based photographer<br />

whose career spans over 25 years. His<br />

work has been published in National Geographic,<br />

The New York Times <strong>Magazine</strong>, Mother Jones,<br />

Newsweek, New York <strong>Magazine</strong> and others. He<br />

teaches at NYU and the International Center<br />

for Photography (ICP), among others, and has<br />

published several books including, more recently:<br />

Taxi: A Journey Through My Window 1977-1987<br />

and LAPD 1994. Below is an excerpt from our<br />

conversation, edited for clarity.<br />

By Caterina Clerici<br />

Caterina Clerici: Can you tell us about<br />

your background and how you got<br />

started in photography?<br />

and then dropped out and then got into<br />

the drug scene, started doing heroin,<br />

selling heroin, all that bad boy stuff. I<br />

went to Rikers Island. First time I went in, I<br />

was 17 years old. The second time I was<br />

20, and I was a much tougher guy than<br />

when I first went in. Rikers Island is not<br />

a place that I can even describe to you.<br />

How horrible that place is, that’s a whole<br />

other story.<br />

However, I came out at a very interesting<br />

time because I felt the need to change<br />

and those were the times of affirmative<br />

action, the only way for most young people<br />

to go to college without the ugly bank<br />

loans we have today. Through education<br />

I got myself together: got off methadone<br />

at 26, got my GED and studied graphic<br />

arts technology at the New York City<br />

Technical College in downtown Brooklyn.<br />

In 1980, I came out of school — first one<br />

to go to college in my family — and got<br />

a job in the printing business. You would<br />

send us your chromes, and we would<br />

make negatives, make plates and put<br />

them on a printing press. I learned a lot<br />

about color and printing and that helped<br />

my photography later on.<br />

I was making a lot of money in ‘80,<br />

‘81, doing all those big ads you see<br />

on the front pages of magazines, but I<br />

found myself going back down a rabbit<br />

hole, working 50, 60 hours a week. It<br />

was a great experience, but I was really<br />

unhappy. So I quit my job. My mother<br />

was very upset. I went back to driving<br />

a cab (taking photos that made up Taxi:<br />

Journey Through My Windows 1977-<br />

1987) and worked with a friend who had<br />

a truck and an art moving business.<br />

One day we delivered to a gallery in<br />

Soho where Larry Clark was laying his<br />

whole life’s work up on the wall. I went<br />

up to him as if he was Jimi Hendrix, like,<br />

“Oh, man! I really want to do what you<br />

do!” and he said: “Just go make pictures.”<br />

That’s all he said to me.<br />

I went to ICP and started assisting in<br />

the dark room, cleaning up the cibachrome<br />

lab. Then they gave me a scholarship<br />

and my life changed. I was schooled<br />

by some of the greatest Magnum photographers:<br />

Gilles Peress, Susan Meiselas,<br />

Eugene Richards, Alex Webb, Raymond<br />

Depardon, Sebastiao Salgado. The way<br />

I work is the way they work. For weeks,<br />

months and years. Anything personal is<br />

going to take me years. I’m just coming<br />

off following Mexican migrants throughout<br />

the USA for 10 years.<br />

I think about photography in time, and<br />

I always felt great work takes a lot of it.<br />

And, for me, it was always self-initiated.<br />

There were no editors, no one telling me<br />

Joseph Rodriguez: I was born and<br />

raised in Brooklyn in 1951. I grew up<br />

where I live right now, Park Slope, but it<br />

was South Brooklyn then. And you know,<br />

the Italian American history in New York<br />

was very strong. It was a very mafioso<br />

neighborhood and I’m not lying — we<br />

had the Gowanus Canal and it was not<br />

unusual for us to see floating bodies… It<br />

was pretty much like the old Sicilian way.<br />

In my Catholic school there were<br />

only about 400 or 500 of us. There was<br />

one Black kid and one Puerto Rican kid:<br />

me. The other kids were all mostly from<br />

Genoa, in Italy. Every single parent who<br />

lived close by used to grow grapes in<br />

the backyard and you would stop by to<br />

try their wine. It was very old school.<br />

But then the drugs came, and that’s what<br />

brought a lot of the same problems you<br />

have in so many other places.<br />

I lost my way… got into high school<br />

A young 18th Street Gang member being arrested. At the time this photo was taken the ATF (Arms Tobacco and<br />

Firearms) were working with LAPD to try and take down one of the most notorious gangs in Los Angeles. The aim<br />

was also to get as many guns off the streets as possible. Photo by Joseph Rodriguez from LAPD 1994.<br />

52 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

what to do. We just had that practice,<br />

that discipline, which also brings a lot<br />

of anxiety because you’re swimming<br />

upstream and you’re always alone. The<br />

practice is mapping out a story, which<br />

then turns into something longer — like<br />

when I went to LA in 1992 to photograph<br />

gangs and I’m still revisiting that project<br />

some 20 years later.<br />

CC: Can you tell us how your project<br />

on gang violence in LA started, how it<br />

evolved, and the challenges you faced?<br />

JR: When the Rodney King uprising<br />

happened, immediately I wanted to<br />

go, because I was missing America<br />

(Rodriguez was living in Europe at the<br />

time) and I understand the urban narrative,<br />

no matter which city it is — Chicago,<br />

Miami, New York, LA. I couldn’t do much<br />

research while I was living in Europe,<br />

because it wasn’t like now where everything’s<br />

online, but one thing I did was listen<br />

to music: all this gangsta rap, Eazy-E,<br />

Tupac, Dre, N.W.A., Public Enemy. The<br />

rhymes they were spitting out were the<br />

newspapers of the streets. So I was listening<br />

to guys like this Chicano rapper Kid<br />

Frost, who’s totally East LA, and I was like<br />

“Ok, I gotta go there.”<br />

I flew in the middle of the night from<br />

Stockholm to LA and arrived in my hotel<br />

room. I didn’t know where I was going,<br />

I had no connections and LA is huge!<br />

So I grabbed three newspapers, turned<br />

on the news and of course there was a<br />

funeral and a drive-by shooting every<br />

minute.<br />

There was a lot of ground to cover,<br />

so I stayed five weeks and worked<br />

really hard. No sleep, just worked and<br />

drove around, from one neighborhood<br />

to another, also with the cops doing the<br />

gang unit. But I knew our history already.<br />

I began interviewing African-American<br />

families in Watts, asking what was the<br />

difference with the riots in 1965, in the<br />

era when Malcolm X and Robert Kennedy<br />

were assassinated and there was a lot<br />

of city streets burning. The conversation<br />

began and it opened up doors, and I<br />

realized I wasn’t interested in just the<br />

guns or the people dying. This was a<br />

generational story that went back three or<br />

Waiting for a fare outside 220 West Houston Street, an after-after-hours club. New York 1984. Photo by Joseph<br />

Rodriguez from Taxi: A Journey Through My Window 1977-1987.<br />

four generations. That’s when I really felt<br />

the power of this story.<br />

I went back to Stockholm and we published<br />

what we could. I applied for an artist<br />

grant there, and then I moved to LA in<br />

September of ‘92. It was hard, I had left<br />

the kids behind and just kept flying back,<br />

trying not to be the absentee father that I<br />

was. But that was the path I was on.<br />

The gang project was very hard to<br />

do and I paid the psychological price<br />

for it, in terms of PTSD. At least eleven<br />

kids are dead, in the East Side Stories:<br />

Gang Life in East L.A. book. Children<br />

were dying and parents were telling me<br />

I needed to tell this story. Plus, sometimes<br />

people thought I was an undercover cop.<br />

I showed them my Spanish Harlem book<br />

and my National Geographic stories to<br />

prove that I wasn’t a cop, but paranoia<br />

runs deep in the hood. That hung over my<br />

head for a while — until the book was<br />

published — and I was going to quit the<br />

project, I felt I couldn’t handle it.<br />

I also had guys come say to me: “Yo,<br />

man, I’m about to go do a hit, you can<br />

come and just take pictures.” This is ethics.<br />

I said: “Look, I go with you, I photograph<br />

you doing this scene. Detectives<br />

come, they find out who’s who, they<br />

take my film and they use the evidence<br />

against you.” Some of the gang members<br />

were 16 years old; they didn’t know how<br />

the law worked. They didn’t understand<br />

what a camera could do. They were so<br />

enamored by their vanity and Hollywood<br />

influence. With a camera comes a lot of<br />

responsibility.<br />

CC: How did your surroundings while<br />

growing up influence your practice and<br />

your understanding of photography, as<br />

well as your mission as a “humanist”, as<br />

you often define yourself?<br />

JR: I grew up with my mother and her<br />

sisters, and there were no men in my family.<br />

My stepfather was a dope fiend who<br />

died on the streets. There were a lot of<br />

not nice things growing up, and that was<br />

very tough for me.<br />

One thing I remember is that my mom<br />

would sit with her sisters in a very old<br />

school, Italian way, they would have their<br />

coffee and talk about the men. I would<br />

hear these stories — it was unbelievable<br />

— of abuse and cheating, and those references<br />

helped me develop a feminine eye.<br />

I’m always asking myself: “Why did<br />

this photographer go photograph a gangster<br />

with guns, bullets and drugs, but then<br />

didn’t photograph a mother at the same<br />

time, or the struggling parent?” That’s<br />

always been very important in my work. I<br />

didn’t always go for the guns.<br />

“Raised in violence, I enacted my own<br />

violence upon the world and upon myself.<br />

What saved me was the camera, its ability<br />

to gaze upon, to focus, to investigate,<br />

to reclaim, to resist, to re-envision.” That<br />

quote is from my journal. That’s how I<br />

got here, that’s where this goal comes<br />

from. That’s why I went back for East Side<br />

Stories (Rodriguez’s long-term project<br />

about gang violence in LA, shot between<br />

1992–2017.)<br />

Continued on page 70.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 53

But before delving into how documentary<br />

photography is evolving, it is essential<br />

to first address the fight to change<br />

the internal practices and structure of the<br />

photo industry itself.<br />

One of the biggest problems in<br />

photography is the widespread percep-<br />

Years ago,<br />

tion among audiences that photographs<br />

during an artist talk at a journalism<br />

conference, I stated that I the extent to which a photographer’s<br />

don’t lie. Most people don’t understand<br />

don’t believe documentary photographs<br />

create social change. A consume. This knee-jerk assumption of<br />

personal biases impact the images we<br />

colleague stood up and interrupted my objectivity allows audiences to accept<br />

talk to disagree with me. Our impromptu an image as truth: forming hard-andfast<br />

opinions about events and cultures.<br />

debate--across an audience of photographers<br />

and journalism students--exemplifies Without critical assessment from the viewers,<br />

the photographer has tremendous<br />

an important dialog within our industry<br />

that is pushing the boundaries of how power over the value viewers assign to<br />

photography is created and used. Our the lives of the individuals pictured. Such<br />

power and representation have plagued<br />

the industry since the advent of photography<br />

as a medium. Recent momentum<br />

in acknowledging and changing these<br />

practices prompted the formation of<br />

collectives such as Women Photograph,<br />

MFON, Diversify Photo, Ingenious<br />

Photograph, and the Authority Collective,<br />

to name a few. Meaningful reflection<br />

about representation, connection, and<br />

accountability are imperative starting<br />

points for anyone assigning, publishing,<br />

Photography &<br />

By Emily Schiffer<br />

disagreement hinged on different definitions<br />

of what “social change” looks like<br />

and means. I was asserting that images<br />

create awareness--which unreliably<br />

evokes empathy, shifts mindsets, and<br />